Rabbit hunt in Vegas

This story originally appeared in the November 22, 1965 issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

Quodlibet, which is Latin for "as you please," was the term used by the schoolmen of the Middle Ages to designate the subtle questions of casuistry on which they flaunted their dialectical skill. "How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?" is a quodlibet. "Whether a chimera ruminating in a vacuum devoureth second intentions" is a quodlibet. And so, perhaps, is "How can Floyd Patterson defeat Cassius Clay on November 22 in the Las Vegas Convention Center without a baseball bat and two rolls of quarters?"

But if, coincidentally, Clay, that marvelous, whimsical, overweening and—when he turns the volume down—charming young man, takes Patterson too lightly, and Patterson, who often seems enfeebled by one obscure punch or another, can again fight at the top of his memorable form, then Floyd could win it. It says here. Indeed. The first possibility is what has Angelo Dundee, who serves as Clay's manager, despairing in the long corridors of the El Morocco Motel, where, appropriately, Mohammad Ali, as Clay publicly insists on being called, and his largely Black Muslim retinue are encamped. "I can't dissect my guy's mind," Angelo says. "He may be taking the other guy cheap. The champ keeps asking me, 'You think I'm the greatest?' I tell him, 'Yes, only one guy can lick you—you.' Great fighters have a tendency to do it—to lick themselves. I've briefed and baptized him and rebaptized him and rebriefed him. Don't low-rate Mr. Patterson."

What's bugging Angelo is Clay's possibly frivolous assertion that the fight is going to go six or seven rounds, so that l) there will be enough time to properly humiliate Patterson, 2) he can show the people how beautifully he can fight and 3) he can enjoy the movie. "I never look at the second Liston fight," Clay says. "It's only half a reel. There's nothing to see. I want something to holler and rejoice over."

These niceties are lost on Angelo. "Look, friend," he says, "if it goes 11 seconds, let it go 11 seconds. Liston's given me the key—a strong left hand. Left jab, hook off it, left uppercut. Right uppercut when Mr. Patterson lunges. My guy's going to surround him. Listen, my guy's got an uppercut, if he hit Mr. Patterson on the chinski with it, it's all cheroot. It's all over, Daddy."

The other morning Clay expounded on these and related subjects dear to him. He was lounging in bed at the El Morocco, braying into a pair of microphones that rested on his bare chest. His personal photographer, Howard Bingham, was asleep in the other bed. The man they call Cap'n Sam, who is the secular head of the Miami mosque and makes like Clay's bodyguard, sat attentively in a chair, as though he might be called upon to recite. "Witness this annihilation in your local theater," Clay was saying. "I'm the fastest in the torritory. In the torritery. In the territory.." He then bum-bummed a few bars of the Dead March from Saul. He was cutting a tape for a radio spot on his stereo recorder. He played it back, and the voice faithfully issuing from the twin speakers must have made him feel warm all over. He smiled broadly and winked.

"I don't want the rabbit to make a quick million dollars," Clay said, commencing his exordium. Clay rarely converses. He communicates with his entourage in kind of click language. The rest of the time he harangues—great, fantastic, inflective, nonstop orations, on the order of Dr. Castro's. "I want to punish him. To cause him pain," Clay said. "You find out what a person don't like, then you give it to him. He don't like to be embarrassed, because he has so much pride, so I'm going to make him ashamed. He is going to suffer serious chastisement. The man picked the wrong time to start talking to the wrong man. When Floyd talks about me he puts himself on a universal spot. We don't consider the Muslims [Clay pronounces it Mooslims] have the title any more than the Baptists thought they had it when Joe Louis was champ. Does he think I'm going to be ignorant enough to attack his religion? I got so many Catholic friends of all races. And who's me to be an authority on the Catholic religion? Why should I act like a fool? He says he's going to bring the title back to America. I act like I belong to America more than he do. I represented it beautiful in Scotland. I never wink at a woman or go out of a hotel after dark. See, I'm no bogeyman, like they say. Why should I let one old Negro make a fool of me? Floyd would be smart to come out and make a national apology. I've got an unseen power going for me. There'll be almost 4 billion Muslims praying for their brother in Islam. We've got sympathizers in his own camp. How is he going to buck all this? This little, old, dumb pork chop eater don't have a chance. From eating pork he's got trillions of maggots and worms settling in his joints. He may even eat slime of the sea.

"Every stone is a boost. Elijah Mohammad, who speaks directly to God, tells a parable from the Bible or someplace about a donkey lying in a ditch, and all the people who pass throw stones at it. Well, pretty soon the ditch is filled with stones, and the donkey walks out. Floyd's making me double strong. I can fight under pressure, too. When I've been knocked down, something makes me get up and fight. I'm not going to rush myself. This is going to be a beautiful fight. The people are going to see more of me. I'm going to show off, look pretty. I'm so elusive they ain't seen nothing yet. The ring's going to look like it got a gate on each corner. I got some new footwork called the chicken scratch."

Clay sprang, naked, out of bed and demonstrated the chicken scratch, which is a nifty, rapid, back-and-forth shuffle performed in place. Clay also claims he has a new weapon called the linger-on punch, the invention of which he attributes to Stepin Fetchit, a perplexing member of his retinue. Step allegedly dreamed up the anchor punch, too, which dropped on Sonny Liston in Lewiston, Me. Says Clay: "The linger-on punch is fired like the anchor punch, but it is a little slower. It don't knock him out. It dazes him. It keeps him numb. It's a push right hand. It's fast, but it's more of a push, and it has more twist. Before the first round is over, people will say, 'Forget it.' It's going to look like a father beating up on his son. I got superior height, weight, balance, reach, speed, strength and youth. I'm going to keep my distance, keep off him. Then bounce in on him. Two jabs. Bip, bip. Circle over here. Jab four times, hit him with a hook, back off. Walk in on him and grab him. Grab his little self and walk with him."

Clay told Cap'n Sam, who goes about 205, to stand up. Clay then clinched with him and manhandled him about the motel room. "You strong," said Cap'n Sam. "It takes a lot out of a man, straining like that," Clay said. "When he lets go, he's winded. You don't get that tired leaning on him. 'Oh, Rabbit, I just hit you seven times. Watch this jab, Rabbit. Bip, bip, bip. Don't get tired, Rabbit. If you fall down, I'm going to pick you up.' I'm going to make him punch, make him wrassle. A lot of times I'm going to let him punch me in the body. I can afford to let him tire himself out beating on my body. I'd be a fool to try to knock him out in one round. I might wear myself out. But Archie Moore told me, 'Don't go out and dance around.' Soon as the bell rings.... "Here, Sam, you be the Rabbit. Turn your back and bob up and down like he does. Bing. I'm in his corner before he's hardly off the stool, like I was in Lewiston, Me." Clay stalked across the carpet and, as Cap'n Sam turned, uncorked a right. "Wouldn't it crack the people up if I did the chicken scratch before I dropped him with a right lead?" Clay said. "Wouldn't that be pretty? Me in my white shoes. I'm going to point before I do it. Point at the spot where he's going to fall. That would be history, wouldn't it? But wouldn't it be hell if he read this and left town before the fight?

"When he's lying there, I'm going to stick a carrot in his mouth, a carrot with some green on it. 'Nibble on it, Rabbit,' I'll tell him. Don't you think that'll make him leave the country? I'm going to hit him so hard it'll jar his kin-' folk in Africa. Before he fights me again, he'd rather run through hell in a gasoline sport coat. He'd rather shave a lion with a dull blade. He will be beat so bad, he will need a shoe horn to put his hat on. How many days did it take God to make the world? Six. He had his pleasures and his work for six days. Since Patterson loves boxing so, I'm going to give him pleasure for six rounds, which symbolizes six days. On the seventh, I'm going to give him his rest."

Clay climbed wearily back into bed and pulled the covers up to his chin. "Personally, I don't know him that good," he said, softly. He was starting his peroration. "I'm not mad at him. After the fight, it's over. As an individual, I have a degree of admiration for him. It's all an act. I've got to live the legend I am." He closed his eyes and fell fast asleep.

Up the Strip, in his pied-à-terre at the Thunderbird Hotel, is Patterson, the antihero. This is a guy with a screwy image. He speaks softly, so they say he's humble. He's got as much self-esteem as the next person, but he is preoccupied with the idea that people will get the wrong impression, so he prefaces his remarks with "I'm not boasting, but..." and "I'm not bragging, but...." He wants to explain what he has found out, what he feels—which he can do with rare honesty and insight, but he is afraid it will sound like he's alibiing. He is, therefore, often reticent or oblique. He is also suspicious, possessed by imaginary slights, opinionated. His anxieties are frequently excessive or motiveless. For instance, he is convinced people do not like him when he loses. He thinks his current popularity is not because of any affection for himself but because he is the only one around with a chance of beating Clay. When he comes off it, he happens to be an extraordinarily worthwhile guy—funny, sharp, gracious and thoughtful. And it's 3 to 1 he will take this paragraph as a rap. As has been written of Saul Bellow's protagonists, he is burdened by a speculative quest. If he were a Jewish intellectual, what would there be to say?

"He's an intricate man," says Angelo Dundee. "He's a drowning man."

Patterson pretends to live at the Thunderbird, but it is obvious he sleeps elsewhere, secretly. Many of his workouts are held in camera, too, but even in the public sessions he cannot avoid things that he considers embarrassing—two weeks before the fight Mel Turnbow, a sparring partner, knocks him down with a right hand and earns $1,000. All Patterson's sparring partners have this offer. If they can floor the boss, they get $1,000. Says Buster Watson, who has succeeded the late Dan Florio as Patterson's trainer: "That'll teach him to hack around. He's got to concentrate. It's expensive, but it has to be." Buster is one of the few realists in Patterson's camp and as such is an asset.

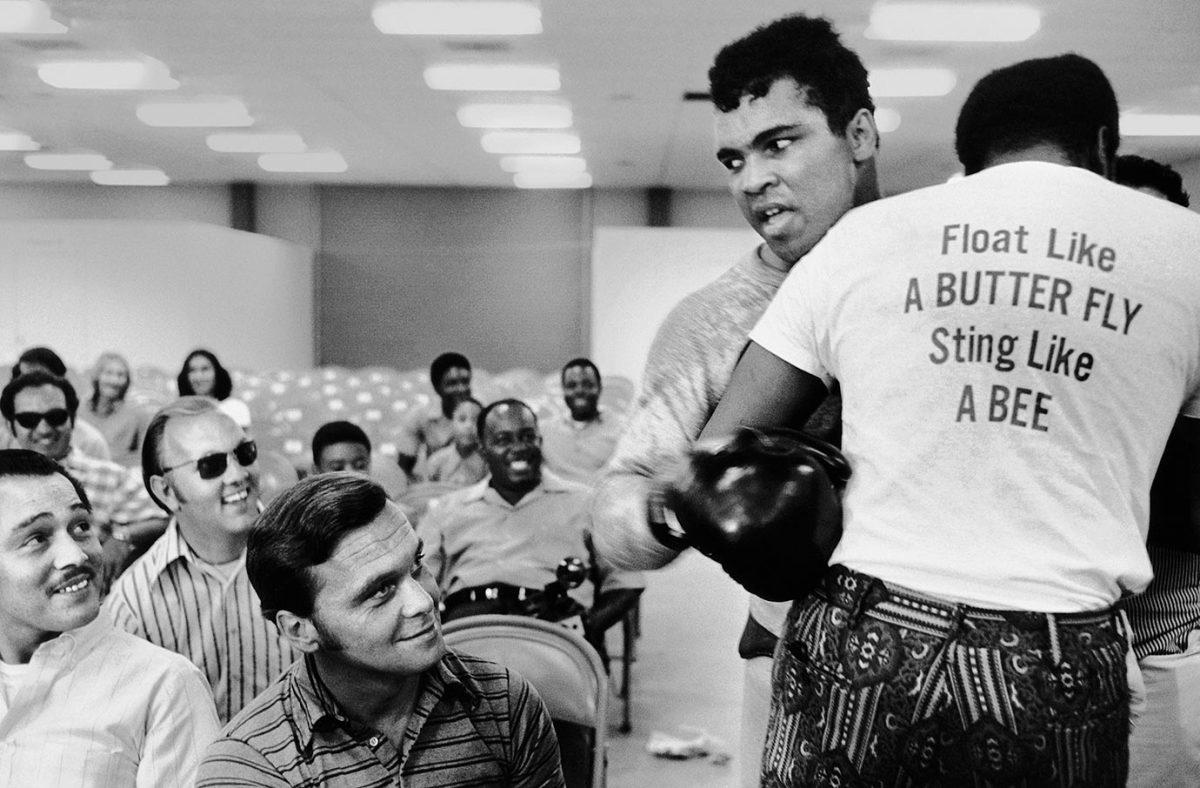

On the other hand, Clay's workouts at the Stardust are always open. At the end of each session he punches the light bag on the stage elevator. In the Stardust's Lido show the elevator supports a great glass flight of stairs upon which are arrayed a ton or so of nudes and a chariot drawn by a real horse galloping on a treadmill. Now, bathed in magenta spots, Clay ascends, punching without gloves, like General Booth going to heaven. Then he leaps off the elevator, clearing a table, crying, "I'm superman. Get a good look at him. I'm the king of the world." He lands, stumbling slightly, out of sight.

"It's better to make friends than build gates," Patterson has said.

In the room with Patterson one morning are Buster Watson; Floyd's pilot and P.R. man, Ted Hansen; Jerome, the second-youngest of the Patterson brothers; Ed Bunyon, who was a sparring partner for the first Johansson fight until he got hit in the eye and became a "walking partner"; Mickey Allan, who sang The Star-Spangled Banner when Patterson was champ; and Ernie Fowler, who has risen from chauffeur to assistant trainer. The last two are sleeping. "Sometimes when we talk," Patterson says, "we talk to hear ourselves. My confidence is within me. I'm sorry to say, but Clay impresses me as being rather young. It is difficult to take someone like that seriously. He's young and spoiled and going in every direction. In fact, he doesn't know what direction he's going in. Nobody knows who is going to win this fight. Clay couldn't convince me in a million years that he knows. There's always a degree of doubt. In all my professional fights and at all the weigh-ins I've never looked one of my opponents in the eye. I always look at their chests. But I've looked at Clay eye-to-eye for a second or two. It was just accidental. I never looked at him long. Such accidents are sometimes inevitable. But each time I looked I detected a weakness, a front. He really doesn't believe what he's saying.

"I'm going to go into the ring with every intention of walking out the winner. I know how I'm going to enter the ring. How I'm going to leave the ring, I don't know. I'm going to win because I'm better, if I'm better. If I am beaten it will be because I am in with a better man than I am. I'm not bragging, I've always been good, but these last five fights [counting from the time he last lost to Liston, Patterson has won five in a row] have restored my confidence. I don't know if I'm the same fighter I was. I know I notice more nowadays. I haven't stopped to find out if I've gotten older, if I can't do the things I once did. If I did I wouldn't accept it. A fighter never admits to age.

"When the bell rings, my No. 1 drive will be to partially repay a debt I owe to boxing. Who is to say what I would actually be if it wasn't for boxing. A laborer? A truck driver? A bum? Surely, I had convict tendencies. My No. 2 drive is to achieve a degree of vindication, although when I look at my record, the ridicule I receive is ridiculous. My No. 3 drive is to win the championship back for America.

"When the bell rang for the first Liston fight, I was, as I have explained in the past, already knocked out. When the bell rang for the second Liston fight, I had to prove to myself that I was just as strong as he was. Why should I back up? He showed me why. I don't know what I'll do against Clay. You can go after a man and get him. You can go after a man and he gets you. I do know that everything I do will be more reflex and instinct than thought out. Sit at ringside. When the bell rings, I'll yell it down to you."

Although the odds on the fight went from 14 to 5 to 3 to 1 following Patterson's untimely knockdown by Turnbow, they are still an underlay. Says Jimmie (The Greek) Snyder, who is, in a way, the oddsmaker emeritus of Las Vegas and who made one of his earlier fortunes tapping out on Joe Louis: "My own personal opinion is that Clay will kick the daylights out of him and the odds should be at least 10 to 1. The fact that Patterson represents the majority of Negroes and that he has done nothing to discredit himself (except he can't fight) is causing a lot of people to make small speculations on him. On the other hand, we have a champion who belongs to a minority group that is not too popular. This normally would mean nothing to an individual who is ready to make a big bet, but sentiment is running away with them and, though they think that Clay will win, they refrain from betting on him in the hope that St. George will slay the dragon with his right-hand spear."

No matter what the proper odds might be, however, it would be imprudent totally to discount Patterson's chances, for there are sound reasons why he could upset Clay or at least make a fight of it. Clay is essentially a long-range fighter. This is a natural consequence of his physique, his inclination and his remarkable quickness. He does not fight inside, and, unlike Liston, he does not care to pound a man in the clinches. This automatically improves Patterson's chances. Of course, Johansson, who was himself disinclined to close with his man, had one notable success against Floyd. Operating from afar, Clay can control a fight. He moves and punches at will as he sets up his victim for the eventual knockout. He does not like to be pressed, however, since then control passes over to his opponent. When this occurs, he is basically on the defensive and cannot exploit his undeniably superior skills and gifts. A good example of this is the Doug Jones fight. One of the smallest and most mobile of Clay's adversaries, Jones kept slipping Clay's jab and punching in close. He did this to special advantage early on but failed to keep it up and lost a fairly close decision. This, too, is Patterson's style, since he, like Jones, is basically too small to fight most heavyweights from outside. Discounting chins, Patterson is a better fighter than Jones. He hits harder. His leap, which is often scorned but has nonetheless proved effective, will enable him to get at Clay. He has greater speed than Jones, particularly with his hands, and he has a naturally aggressive style.

Clay's device of pulling away from punches was a perfect defense against Liston, who could never quite reach Clay's chin with his great, vicious swipes, but Patterson, leaping, can land on the mark, and with impact. It's a risky maneuver, but none of Patterson's opponents have been able to offset it. It should be even safer against Clay, since his lordotic posture makes it difficult for him to counter. Also, because Clay's jabs must be angled down at the shorter Patterson, Floyd will have an opening high on the left side of Clay's neck and head—a situation both camps are well aware of. However, the main thing Patterson must do is press, and press from the bell. As Angelo Dundee says: "In boxing you cannot start in low gear and get to high gear. You've got to start in high." Alas, Patterson has a history of being a "notoriously slow starter, and if this holds for the Clay fight, forget it. Pressing is important for yet another reason. According to Archie Moore, Clay does not breathe properly. He breathes shallowly, like a dog, not from the diaphragm, the way a singer does. If true, this could explain why he has to rest from time to time. Against Liston in Miami Beach, Clay trained and fought in a pattern in which he ran a round and rested a round. Jones never gave him a chance to rest in the early rounds of their fight—which could be why Clay looked so inartistic.

In both the Patterson-Liston fights and the Clay-Liston fights, the importance of comparative styles was overlooked. In reviewing these fights it is now apparent that Patterson's style was exactly the one Liston would do best against, and, in turn, Clay would do best against Liston's. Says Cus D'Amato: "As in a war, it is often the tactical approach that decides the battles. That is why a smaller, inferior force may beat a superior one, as Rommel did in Africa to the British. In this battle Patterson has the style to beat Clay." D'Amato believes the keys are the lead, the assertive two-handed punching, the double hooks, the peekaboo guard, which permits Patterson to fire punches and protect his head almost simultaneously and, perhaps most significantly, the position of Patterson's feet and body.

"Floyd must get inside and rattle off his combinations against Clay's head and body," says D'Amato. "Clay has never fought anyone with Floyd's ability to put punches together—true combinations—and against this kind of pressure he will find it difficult to defend with his hands down." The advantage of the nearly frontal stance, in which the feet are opposed and the hands held high on either side of the head, is that it is an excellent way to cut down the mobility of a fighter like Clay, who tends to move from side to side. This was Liston's major shortcoming against Clay. He was never in position to punch, since his left foot was planted so far in advance of his right. When Clay moved laterally Liston either had to replant his lead foot or, as often happened in his anxiety to reach Clay, he wound up with his legs crossed and totally off balance.

Furthermore, since Clay will be punching down on the crouching Patterson, he will be exposing his jaw to a sneak right hand. This may well be Patterson's biggest punch in the fight. "Patterson likes to lie there in the clinch doing nothing," says Charlie Powell, who has the distinction of losing to both Floyd and Sonny. "That's when you relax, and that's his signal to start ripping off punches, especially that overhand right." Dundee calls this the possum punch, because Patterson plays possum, sagging almost lifelessly in the clinches, before throwing it. "It is the only way he can win," says Angelo. "Patterson must throw straight right hands to the body whenever Clay touches the ropes," says Powell. "Clay invariably leans back and then tries to body slip, but he is, in the first instance, vulnerable to the right hand to the head—he is looking for the left hook."

Just how well Patterson will fare depends on his motivation. Perhaps unfortunately, he no longer seems to fight for some kind of ego satisfaction but rather for dubious, obscure causes. He always fought best when fighting was purely a personal expression. "He was superb," says Tommy Loughran, the old light heavyweight champion, who was once close to Patterson. "He was the nearest thing to Dempsey. So lithe, so supple, and he punched with such power. All of that coupled with ferocity. I thought he could not miss being one of the greatest heavyweights of all time. Then something happened. He became a deliberate puncher, and his body thickened under all that unneeded muscle and weight."

The period when Loughran was impressed with Patterson was near the beginning of Floyd's career. This was when fighting was apparently a release for the frustations of an emotionally disturbed youngster, a way of proving himself, of becoming somebody. In these days he fought with a verve, an irrepressible surge, as though innumerable punches were forcing themselves through his arms. But, according to D'Amato, after he defeated Roy Harris Patterson was told by Dan Florio that he must husband his punches, that a champion should show artistry and reasoned skills. Florio made a mistake. Patterson's indomitable rushes were his essence. He kept his opponents so busy defending themselves that they were rarely able to mount a counteroffensive. In truth, Patterson's overwhelming offense was his defense. When he became a more painstaking fighter he had need of defensive skills that he had never developed.

Since the Harris fight the only occasion on which Patterson returned to his original style was in the second Johansson fight. "I hated him," Floyd said. "It got so when I looked at the meat on my plate, I saw his face gazing up at me. Still, with all my anger I had poise. But it's wrong. A fighter must be a killer? If winning means inflicting a degree of danger, injuring an eye or something, then I don't want to win."

Although Patterson seems to be tolerant of, or bemused by Clay, his camp doesn't buy it. Patterson steams when Clay touches him, as he did the other day in an unscheduled confrontation at The Mint, in downtown Las Vegas. "Come here, sucker," said Clay. "Yes, you, chump. I've got something for you." While the two entourages glared at each other, Clay touched Patterson. Patterson brushed aside his hands and said, in his quiet way, "I've got something for you, too, baby."

But to what avail? Clay is convinced that he is indestructible, because Allah is looking out for him. As a boxer he has a great thing going for him with the Allah routine. Now he has confidence on top of everything else. There is no better example than the second Liston fight. Against all the prefight strategy, Clay ran out at the bell and landed a good right on Liston and then proceeded to do virtually nothing until seconds before the knockout. In the interim he allowed Liston to punch him. It grieved Dundee, but he has learned to put up with it. Clay is truly something else. Besides being a genius in his chosen craft or art, he has a mind of his own, has never readily adapted to instruction and is endlessly tinkering and perfecting. For instance, he conditions his body by letting his sparring partners beat it. This unusual kind of masochism is actually in step with advance thinking on the subject by medical authorities. Dr. Peter Karpovich, the eminent physiologist, has said: "The best way to develop muscle is to do the particular thing you want to use it for."

Clay has been boxing since he was 12, and the things he now does no longer have any roots in intellection. "Isn't nature wonderful," he said once, in a glen in Massachusetts. "What makes moss grow on one side of a tree and not the other? Why do birds fly south and then north in the spring, and why do fish swim upstream to lay eggs? Nature is a mysterious thing. It is just like me. Sometimes I wonder when a big fist comes crashing by and at the last moment I just move my head the smallest bit and the punch comes so close I can feel the wind, but it misses me. How do I know at the last minute to move just enough? How do I know which way to move?"

And the things he does are too numerous to be cataloged. Take the fifth round of the first Liston fight, when, blinded by a caustic solution, Clay kept Liston at bay and broke his concentration just by touching him on the forehead with his left. Or, as Dundee says, marveling, "He'll even miss you on purpose." In addition, he has this absolute preoccupation with boxing, with his body, with himself. Unlike Patterson, he can tune everything else out. Only one topic takes precedence—his absorption with the Muslims. "If Elijah asked me to quit boxing today, I would do so," he has said.

"I got a feeling I was born for a purpose," Clay explained the other night. He was being driven to Larry's Music Bar in the Negro district of Las Vegas, wearing a pink sport coat that glowed spectrally in the dark interior of the car. Clay himself was nearly invisible. (Earlier, Patterson, walking by the parking lot, had seen him. "Actually, all we saw was a pink sport coat," he said later. "We knew who it was.") "I don't know what I'm here for," Clay went on. "I just feel abnormal, a different kind of man. I don't know why I was born. I'm just here. A young man rumbling. I've always had that feeling since I was a little boy. Perhaps I was born to fulfill Biblical prophecies. I just feel I may be part of something—divine things. Everything seems strange to me."

SI's 100 Greatest Photos of Muhammad Ali

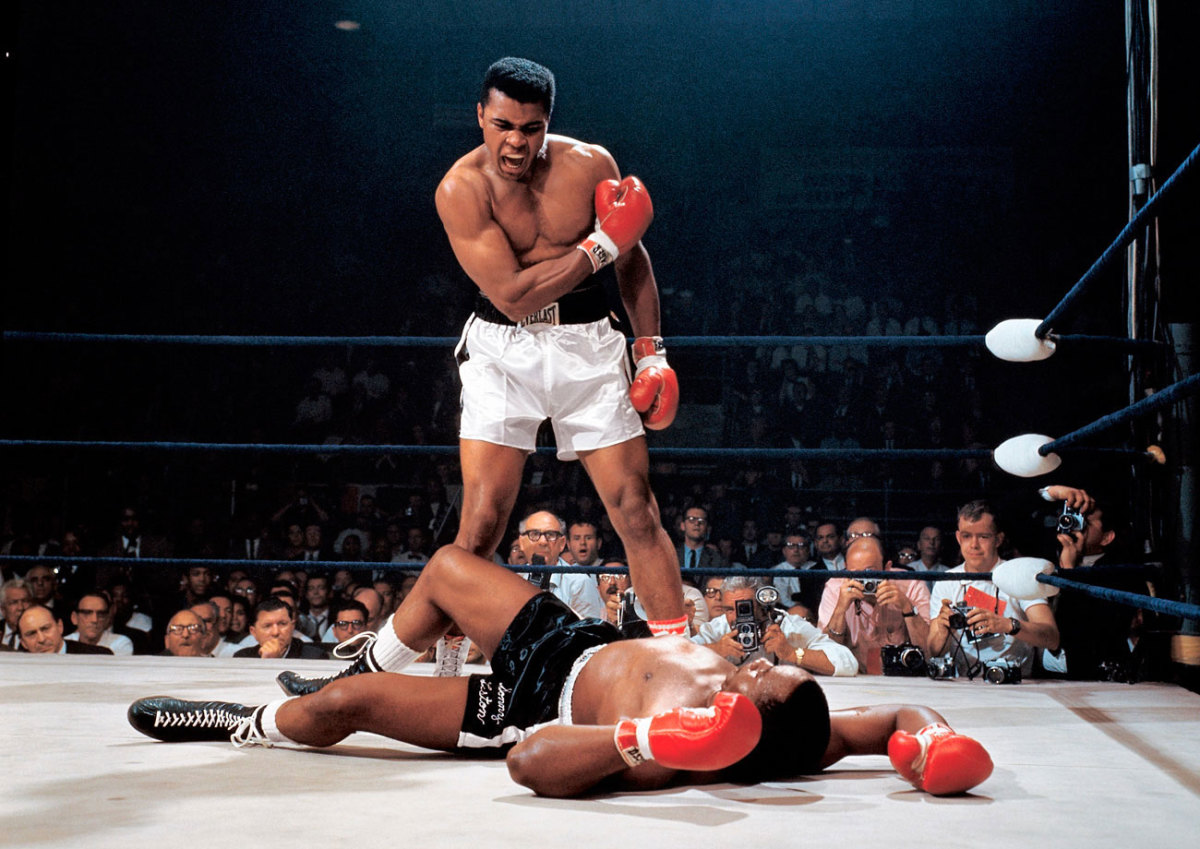

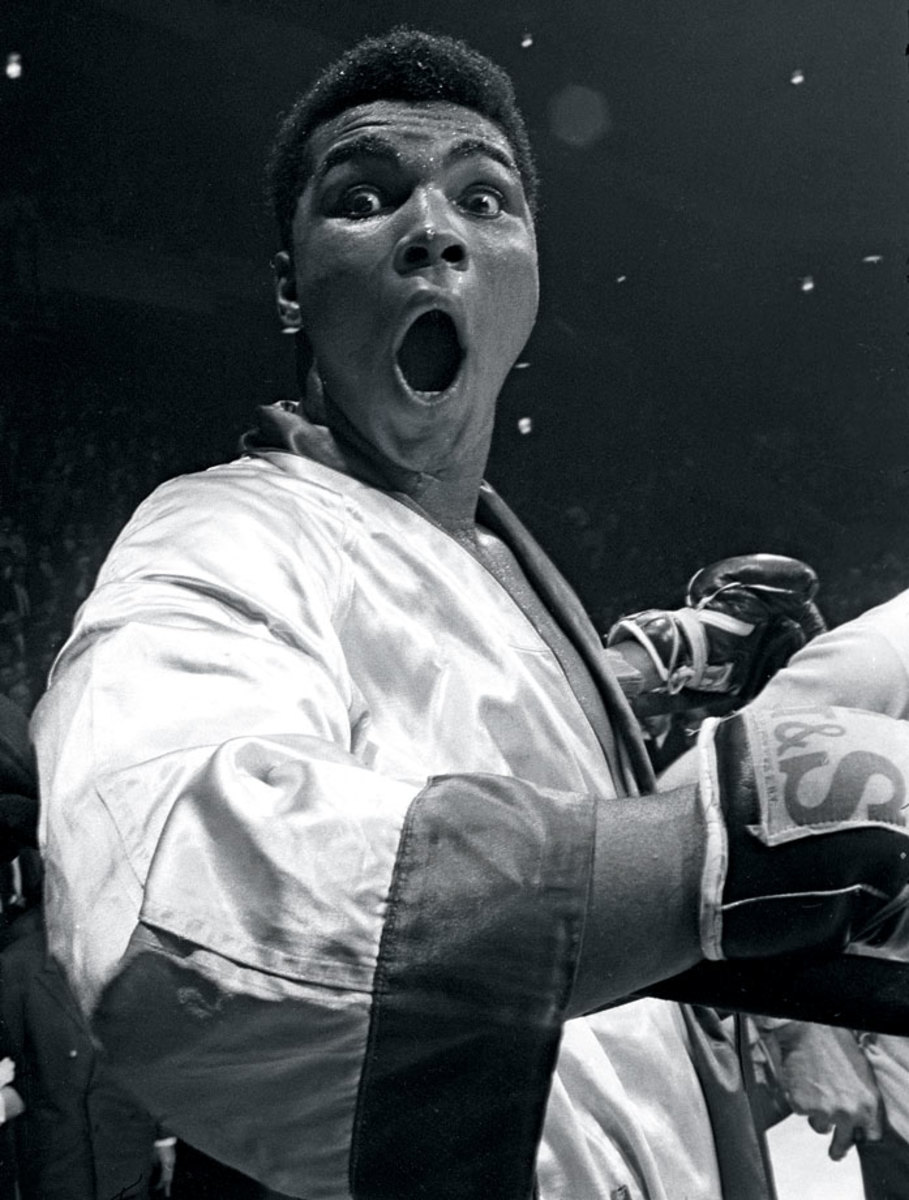

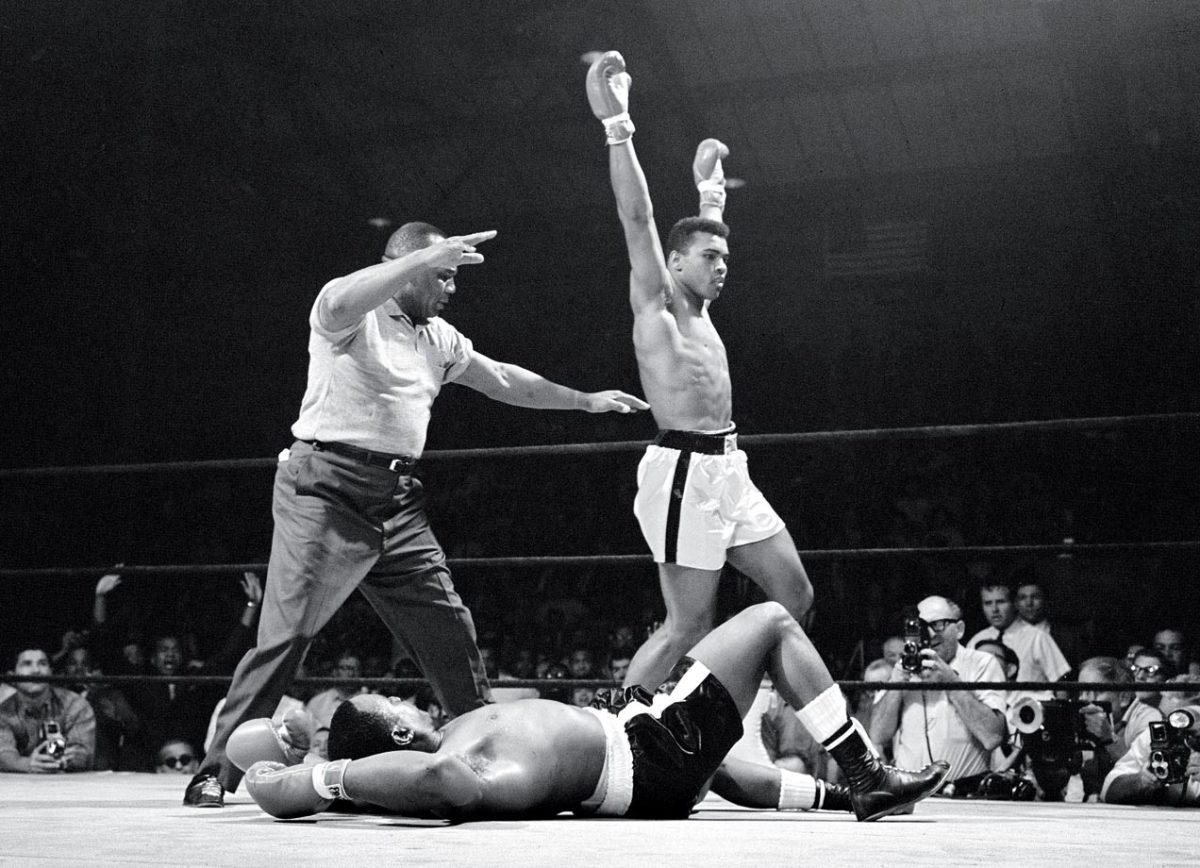

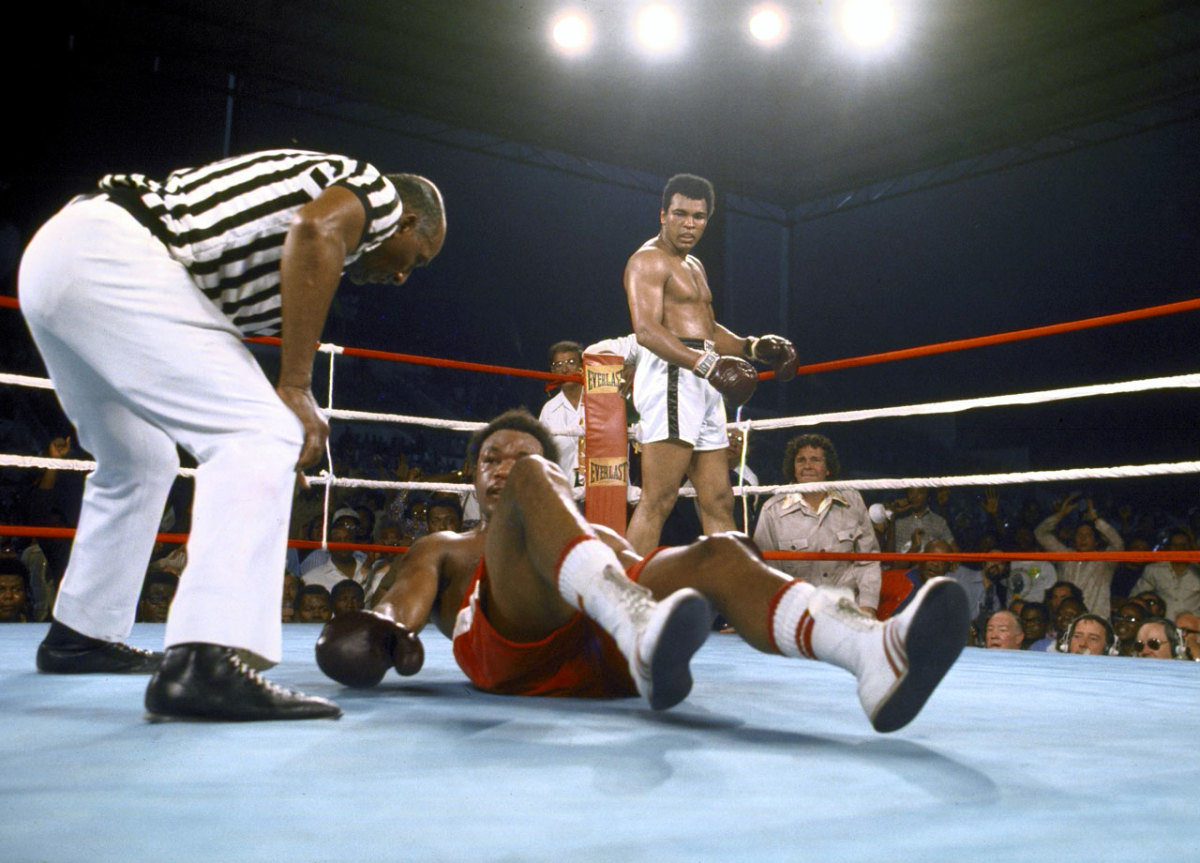

In one of the most iconic and controversial moments of his career, Ali stands over Sonny Liston and yells at him after knocking the former champ down in the first round of their 1965 rematch. Skeptics dubbed it "the Phantom Punch," but films show Ali's flashing right caught Liston flush, knocking him to the canvas. Refusing to go to a neutral corner, Ali stood over Liston and told him to "get up and fight, sucker."

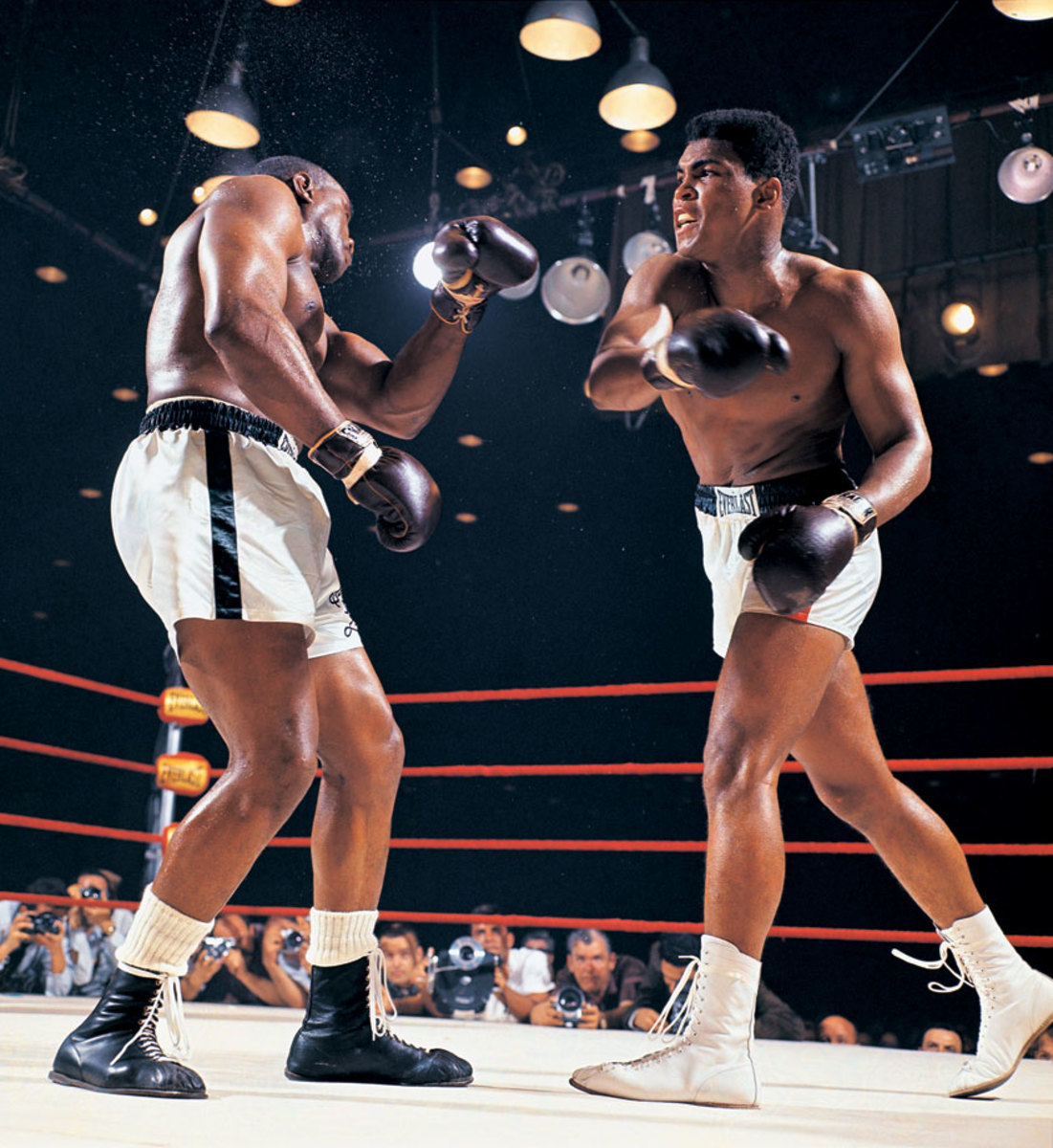

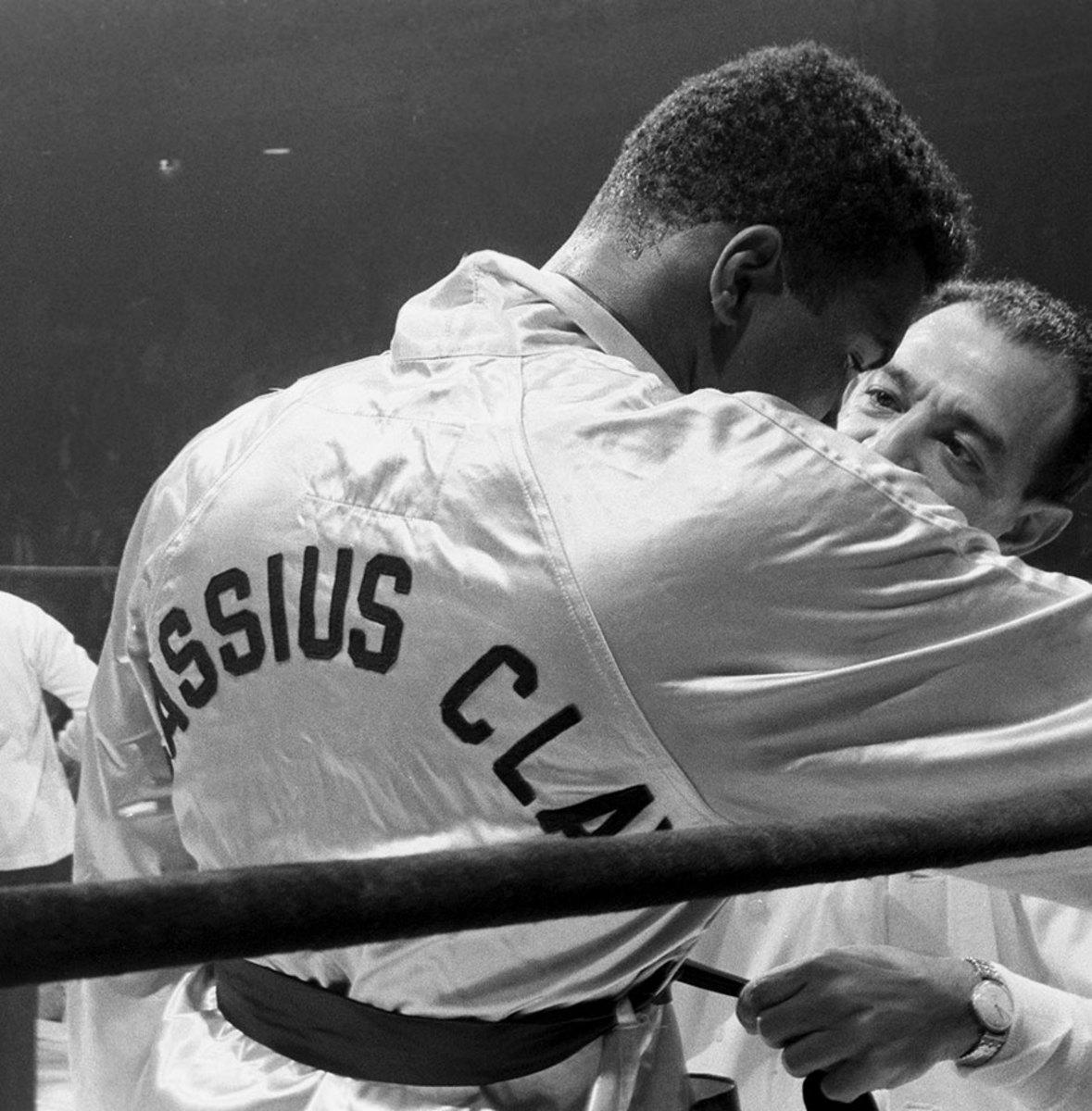

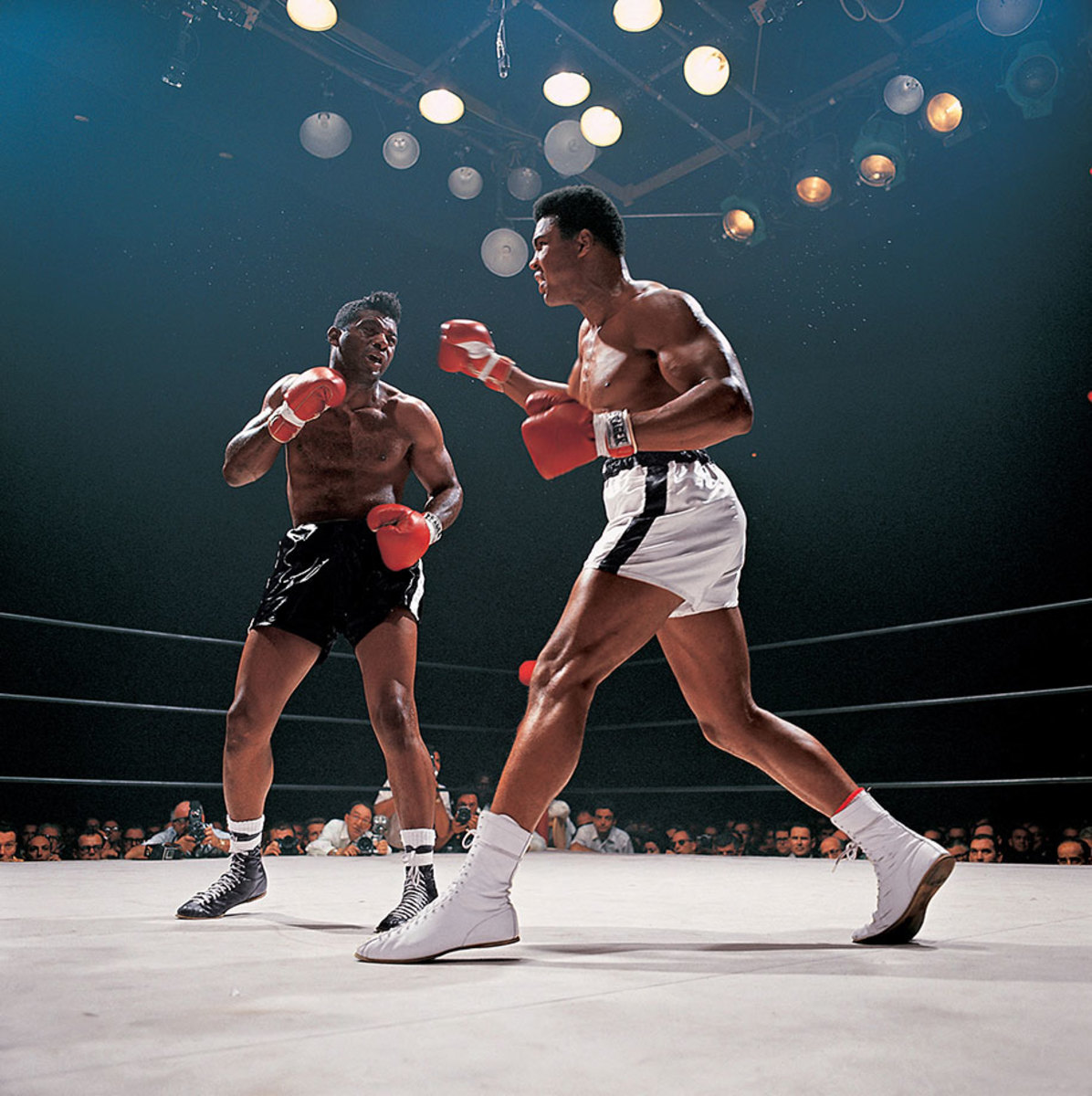

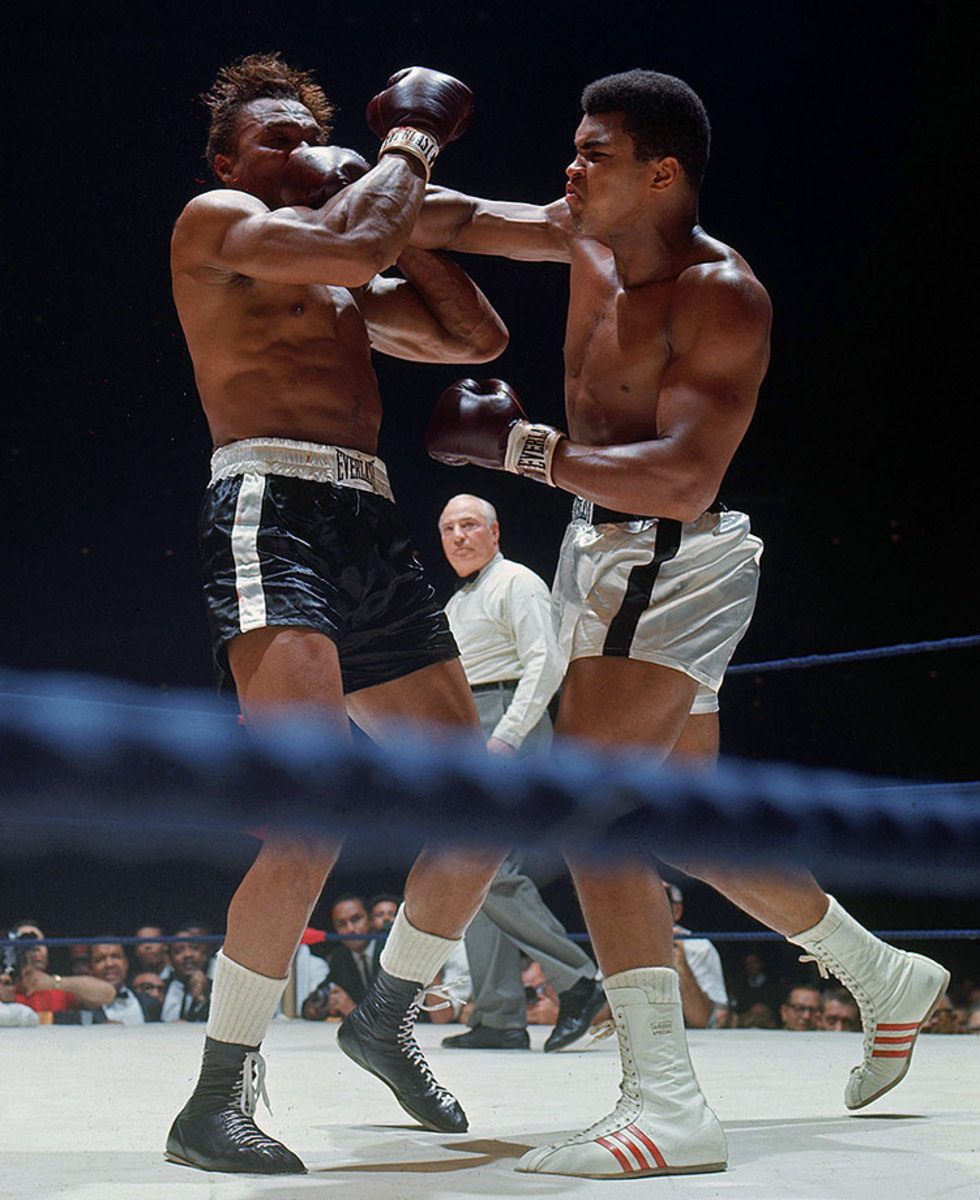

At 22-years-old, Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) battered the heavily favored Sonny Liston in a bout that shook the boxing world. The fight ignited the career of one of sports' most charismatic and controversial figures, whose bouts often became social and political events rather than simply sports contests. At the peak of his fame, Muhammad Ali was the best known athlete in the world. Liston, one of the most feared heavyweight champions in history, was a 1-8 favorite over the young challenger known as the Louisville Lip. But Clay, here stinging the champ with a right, used his dazzling speed and constant movement to dominate the action and pile up points.

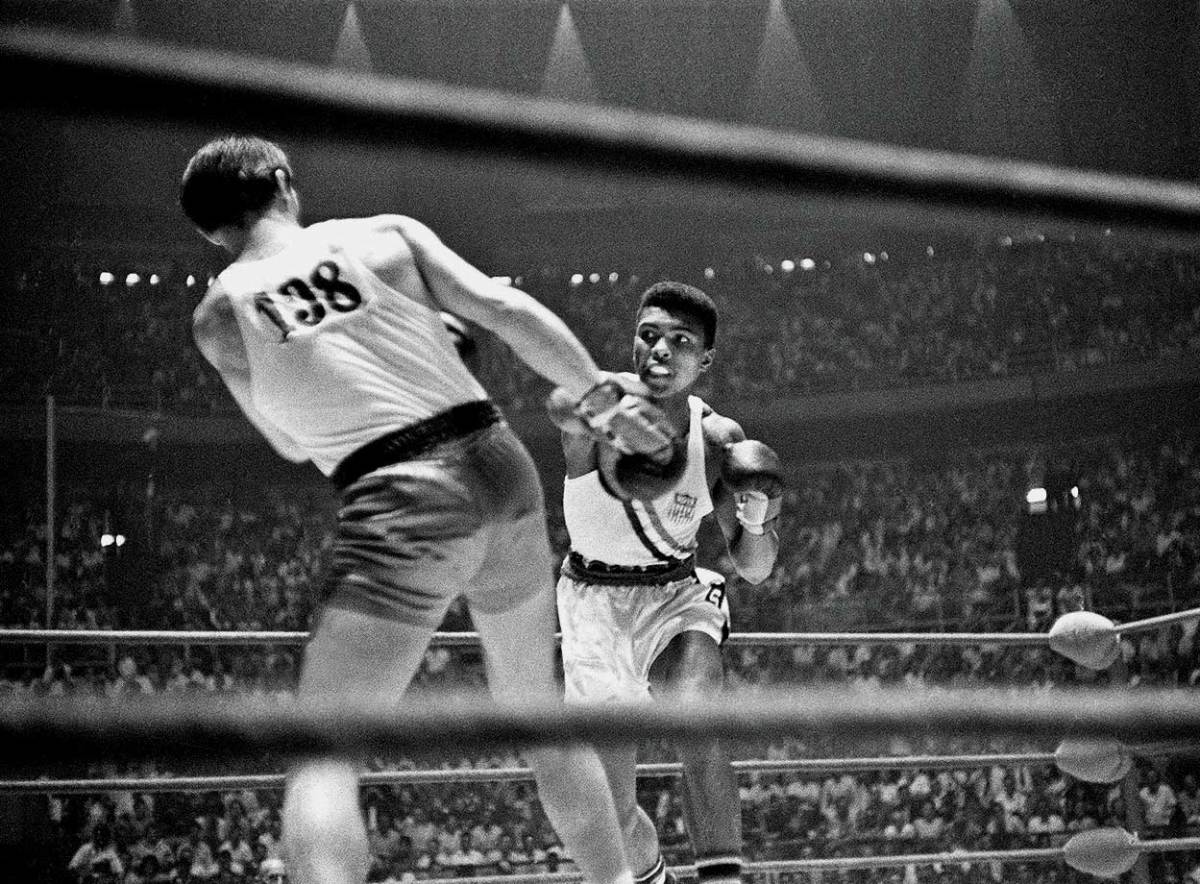

Cassius Clay punches Zbigniew Pietrzykowski of Poland during their gold medal bout at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Clay defeated Pietrzykowski 5-0 for the light heavyweight gold medal.

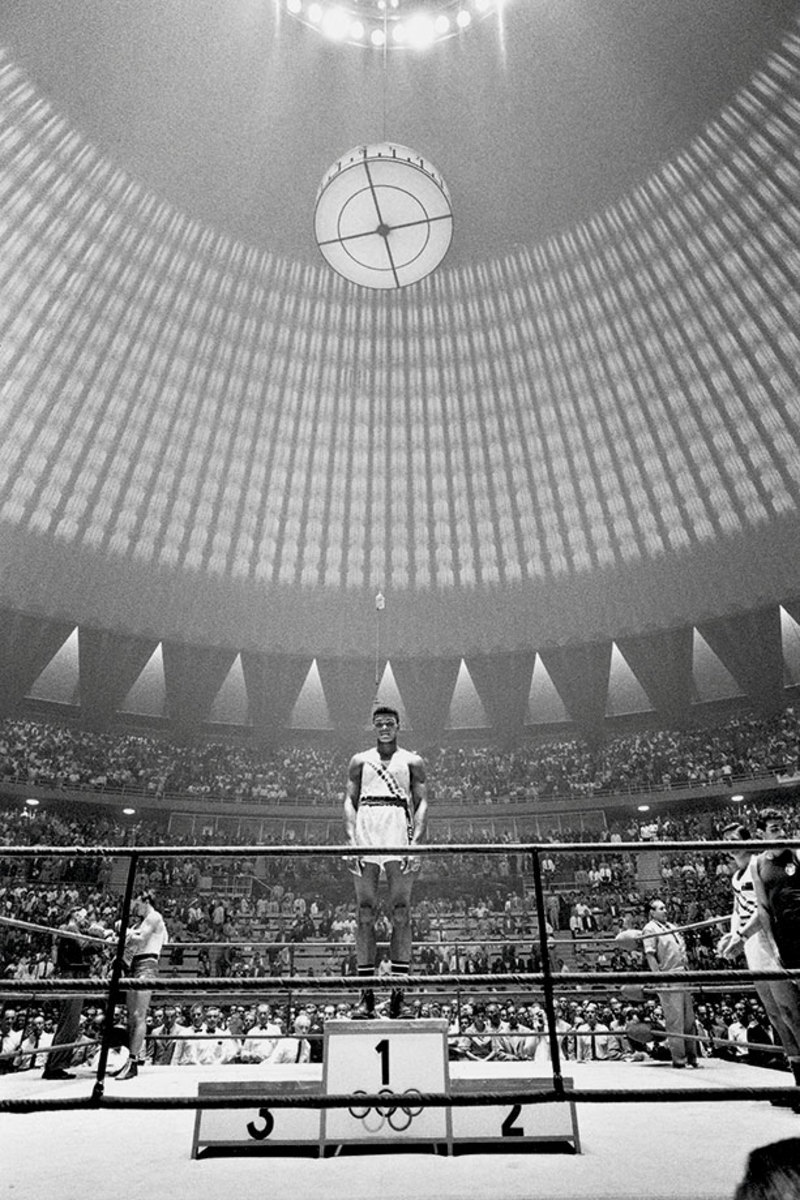

For the 18-year-old from Louisville, here atop the medal stand after his Olympic victory, all roads led from Rome. Clay finished his amateur career with a record of 100-5 and made his professional debut two months after the Games.

Undefeated in his first 17 pro fights, Clay mugged for the camera before the start of his 1963 bout against Doug Jones in Madison Square Garden.

Trainer Angelo Dundee urged his young charge to get serious before the opening bell against Jones. Clay followed instructions and emerged from a tough fight with a unanimous decision victory. Three months later he would stop Henry Cooper and close out 1963 at 19-0.

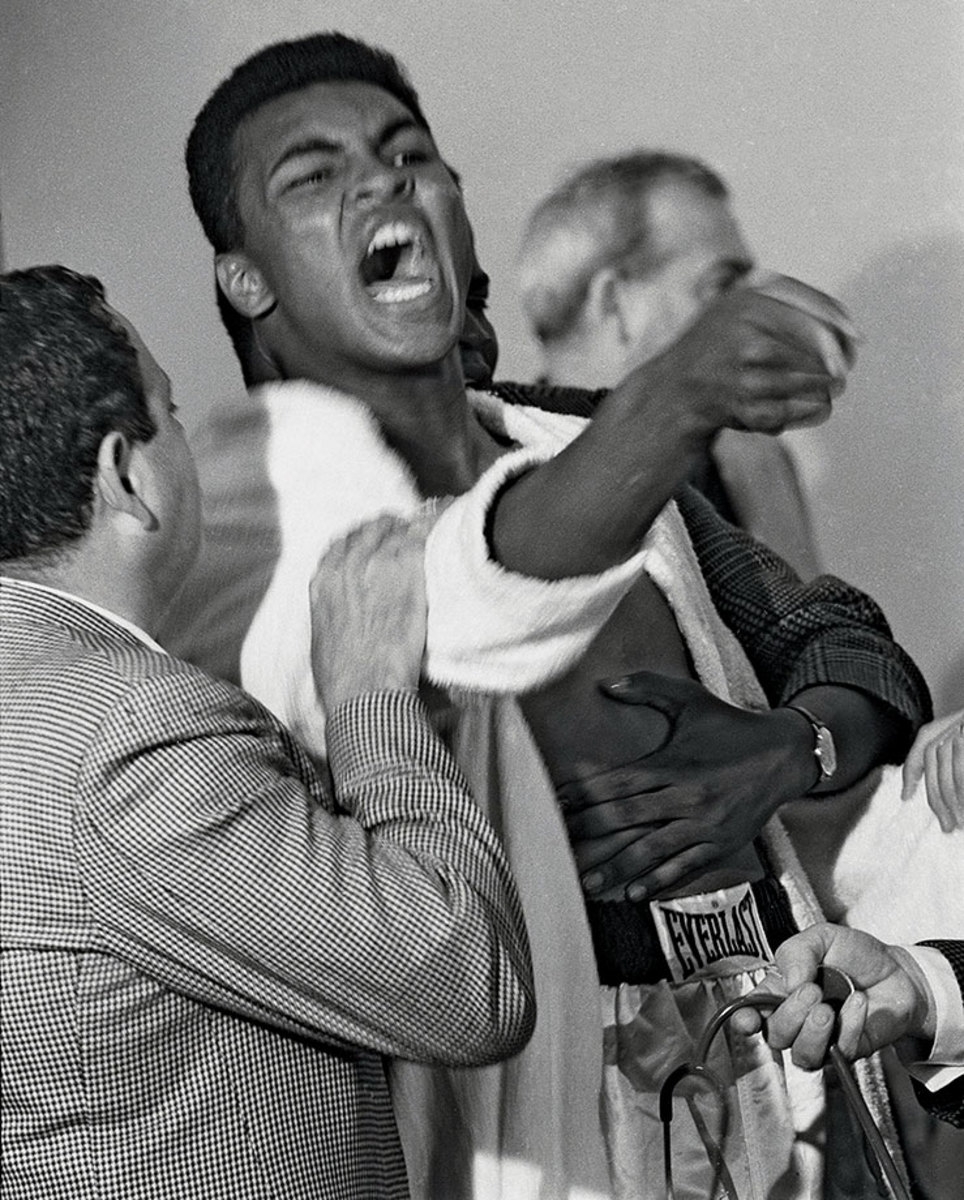

A seemingly hysterical Clay taunted Sonny Liston during the pre-fight physical for their 1964 bout. He had consistently baited the Big Bear during the lead-up to the fight, saying he was going to "use him as a bearskin rug ... after I whup him." The Miami Boxing Commission would fine Clay $2,500 for his outburst at the physical.

"I shook up the world!" an emotional Clay hollered to ringside reporters after his shocking defeat of Liston. And he did just that, claiming the heavyweight title at age 21 after a clearly beaten Liston, complaining of a shoulder injury, failed to answer the bell for the seventh round.

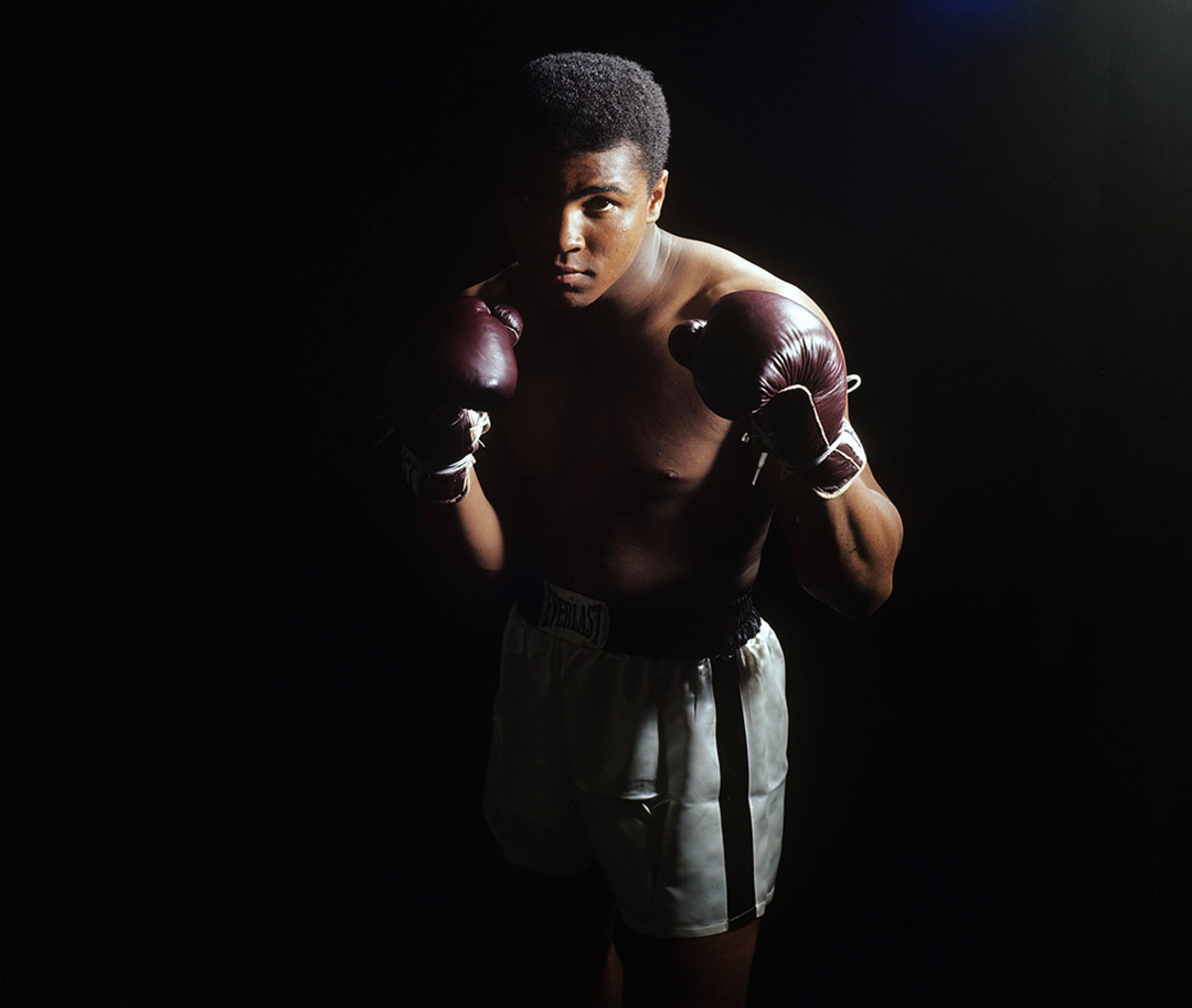

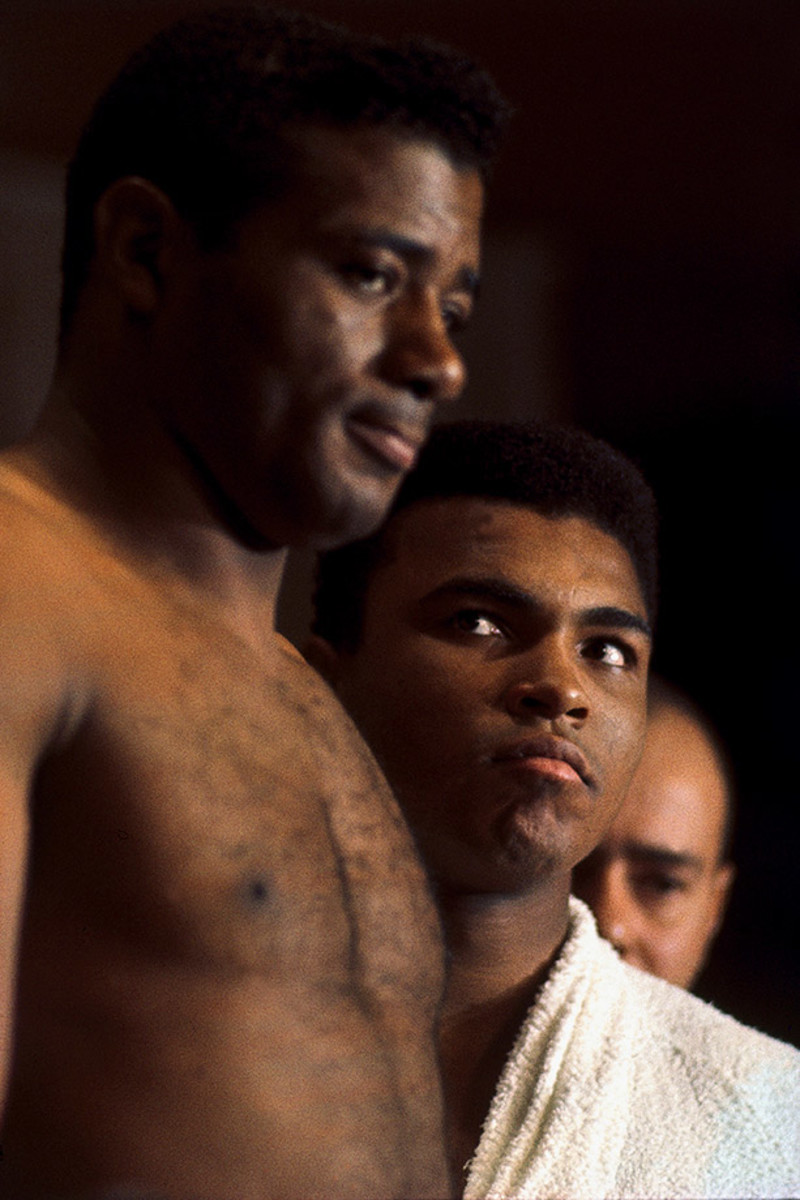

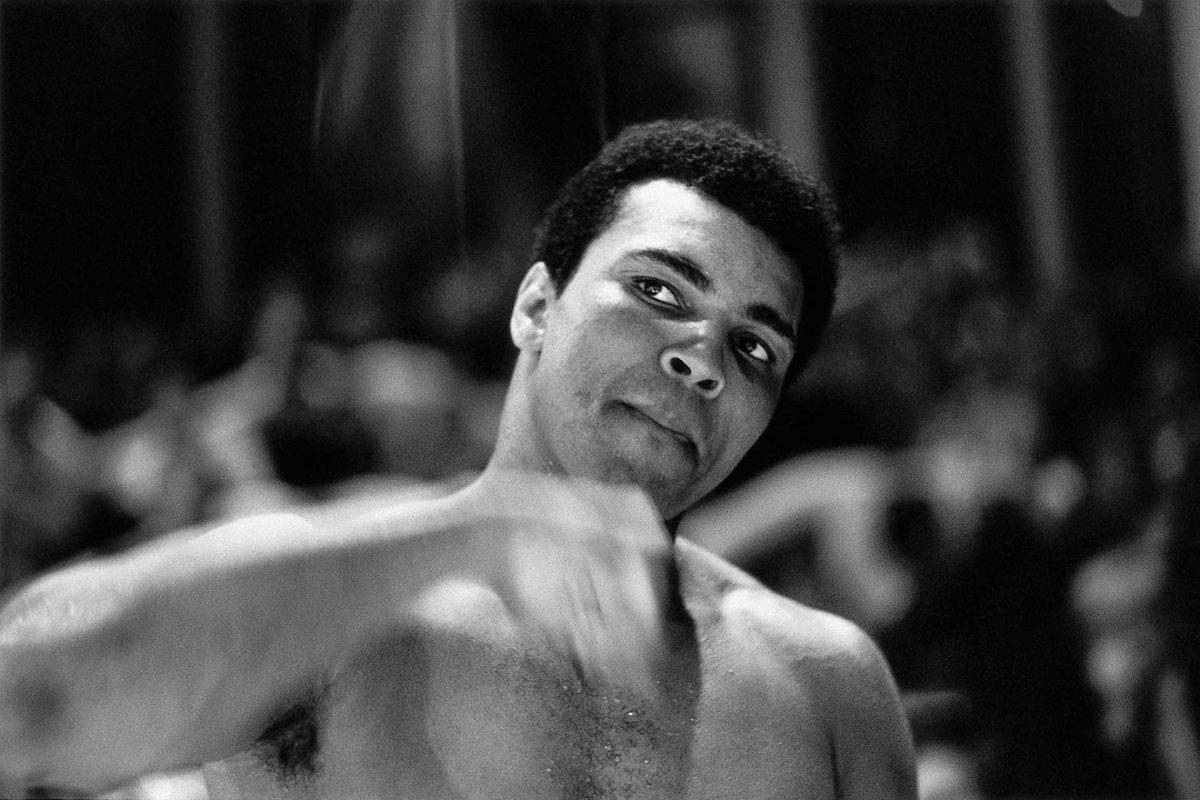

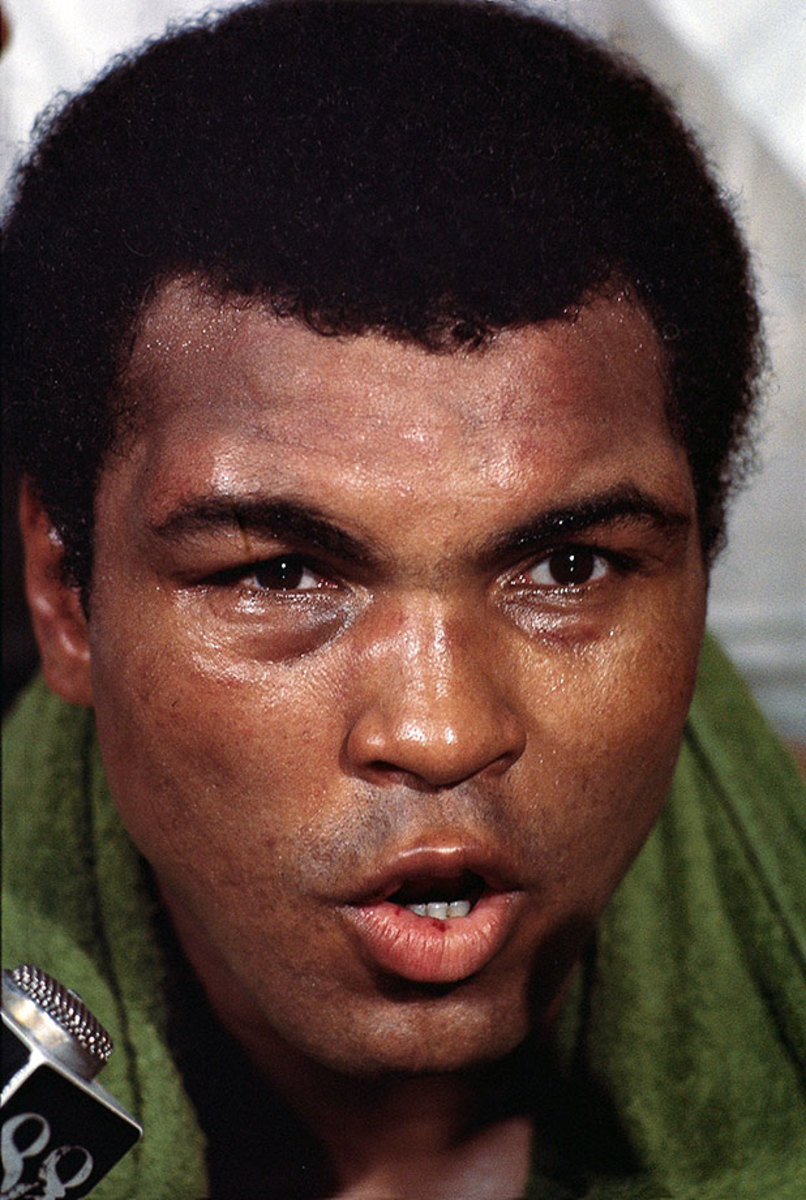

Draped in shadow, the young king — now known as Muhammad Ali — stared down the camera during a photo shoot in April 1965, one month before his rematch against Sonny Liston.

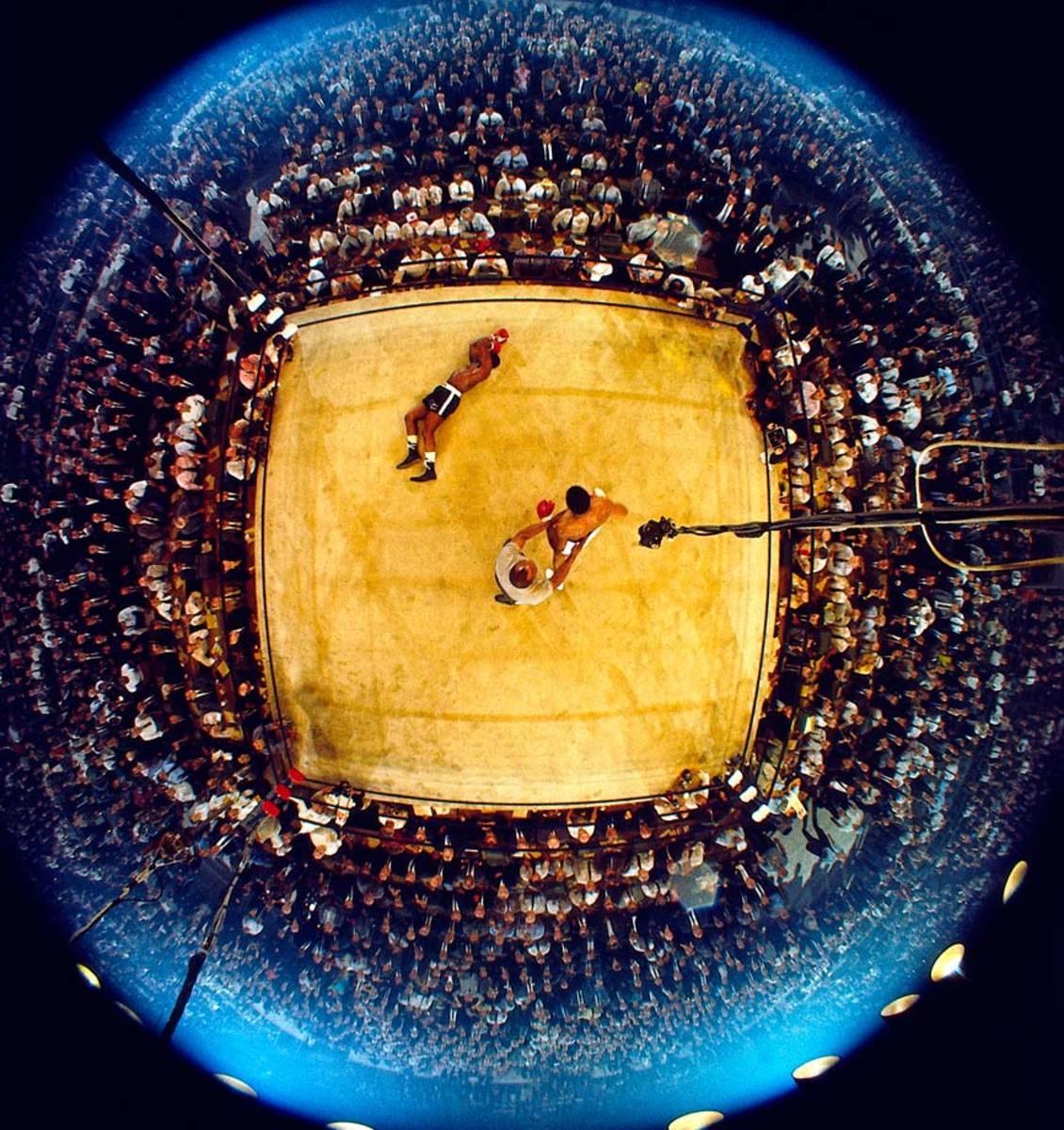

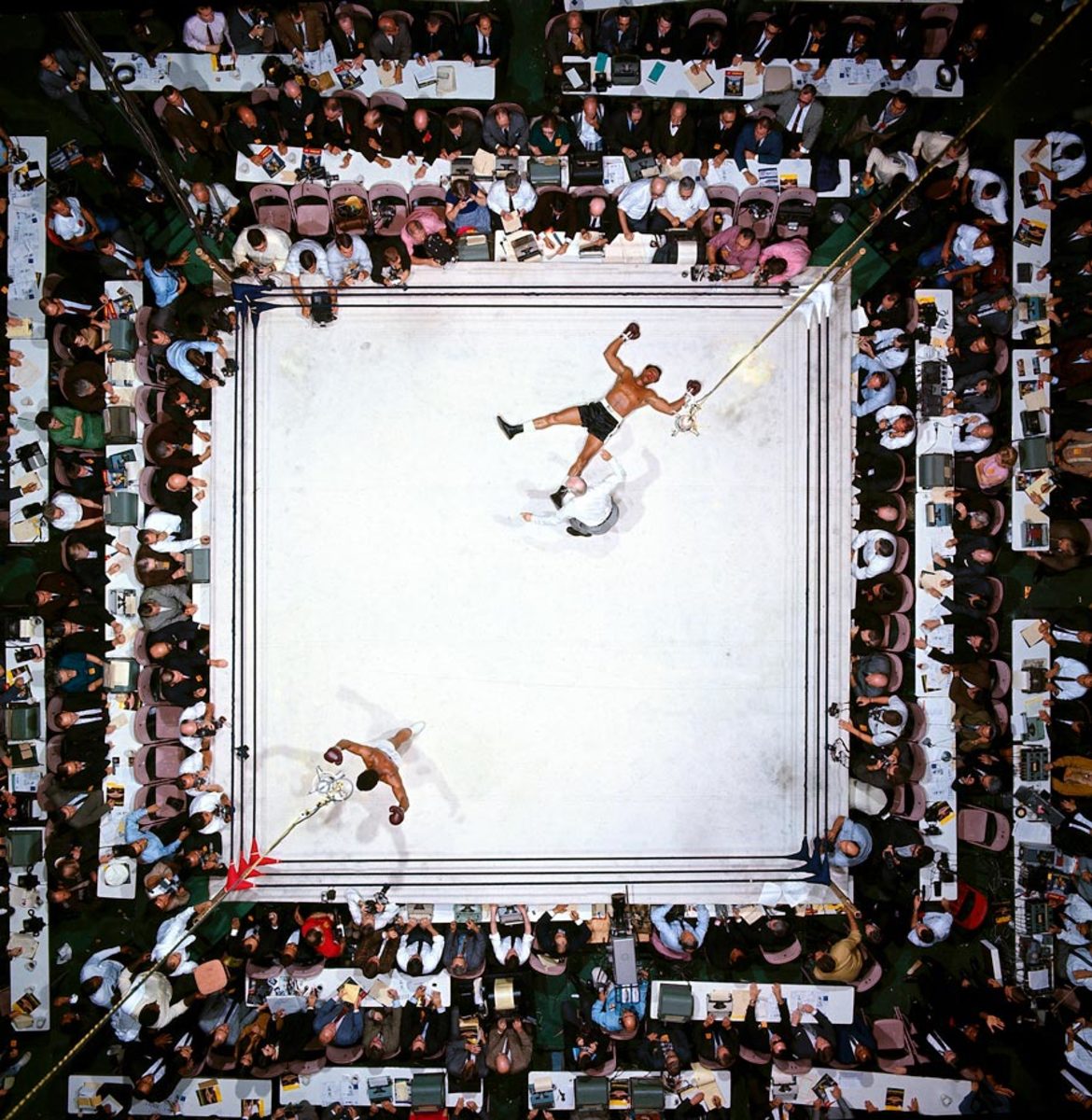

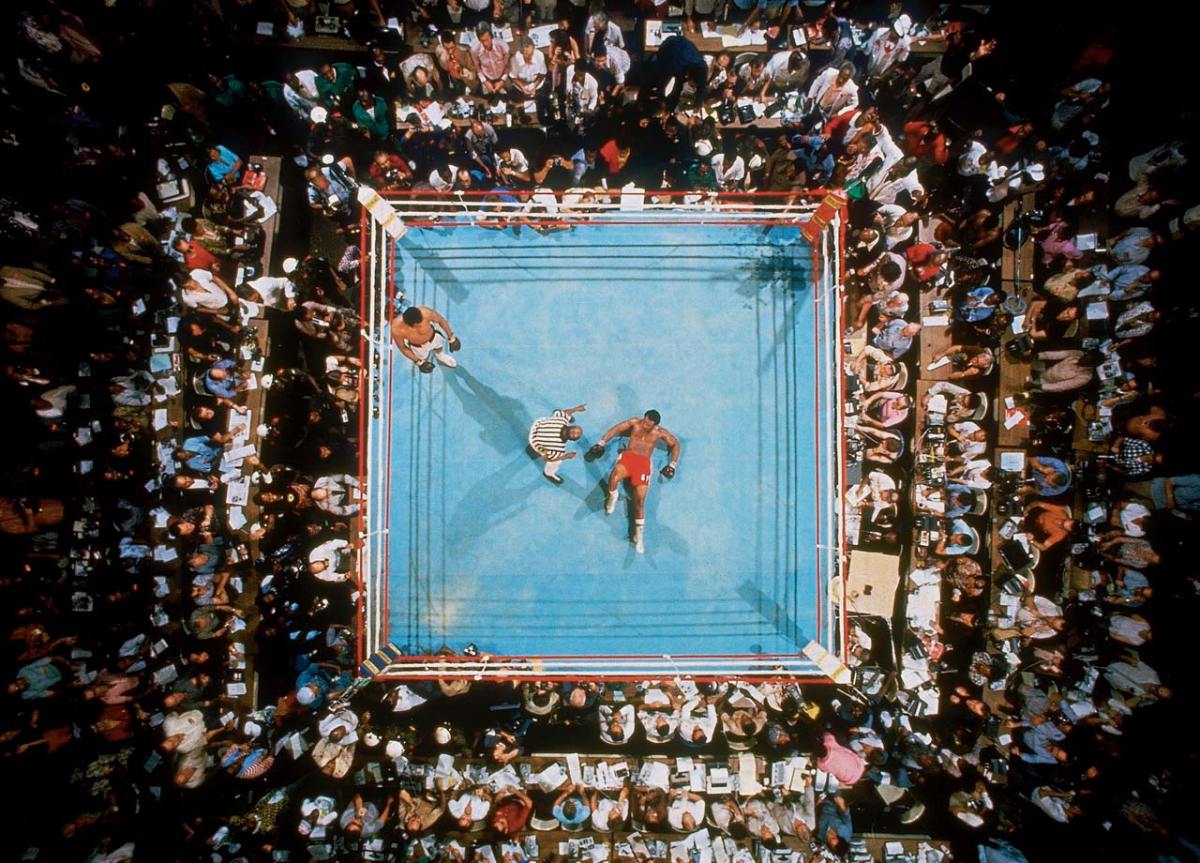

As Liston lingered on the canvas and the referee, former heavyweight champ Jersey Joe Walcott, tried to control Ali, the 2,434 spectators on hand in the Lewiston, Me., hockey arena — a record low for a heavyweight championship fight — tried to make sense of what all that had happened in less than two minutes after the opening bell.

The celebration over Liston continued. In a chaotic ending, Ali was awarded a knockout when Nat Fleischer, publisher of The Ring, informed referee Jersey Joe Walcott from ringside that Liston had been on the canvas for longer than 10 seconds after Ali knocked him down. The bout remains one of the most controversial in boxing history, with many observers insisting that Liston took a dive.

Ali's second title defense came in November 1965, against former two-time heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. During the build-up to the bout, the normally soft-spoken Patterson earned the new champ's wrath by refusing to call Ali by his Muslim name. At the weigh-in, Ali's glare made it clear that he intended Patterson to pay for the disrespect.

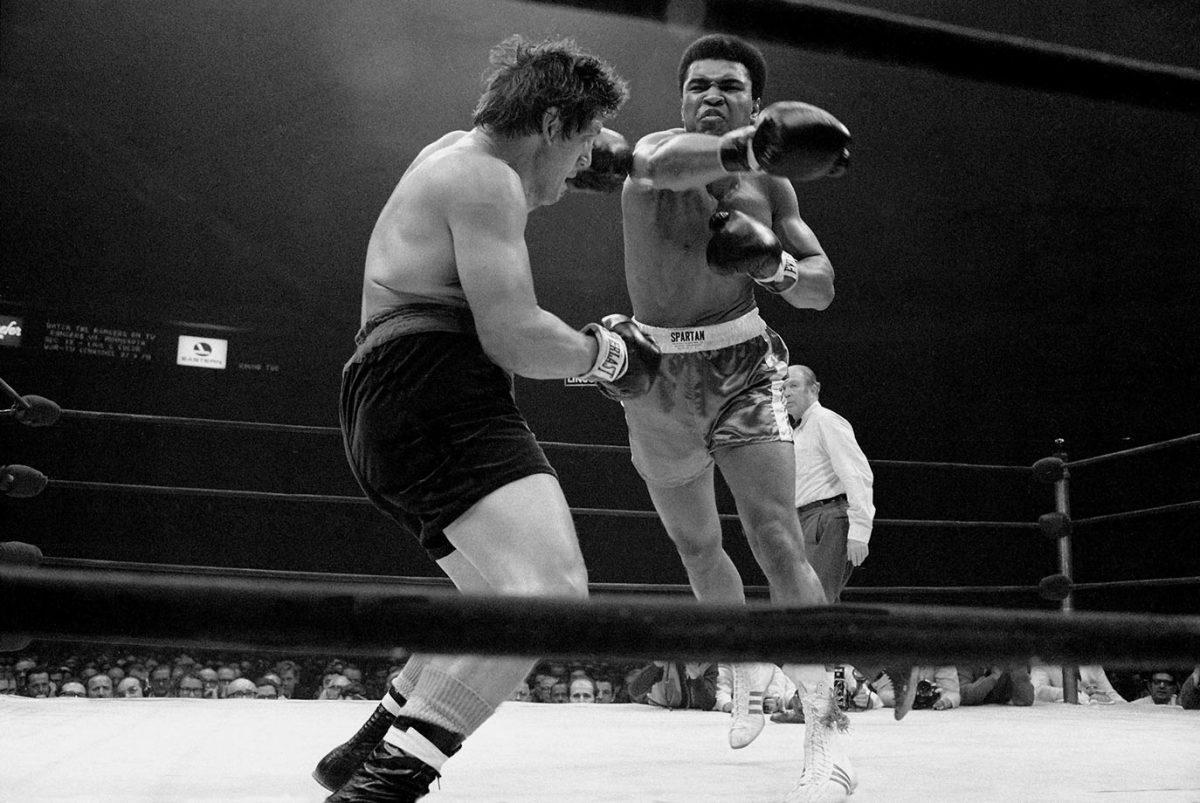

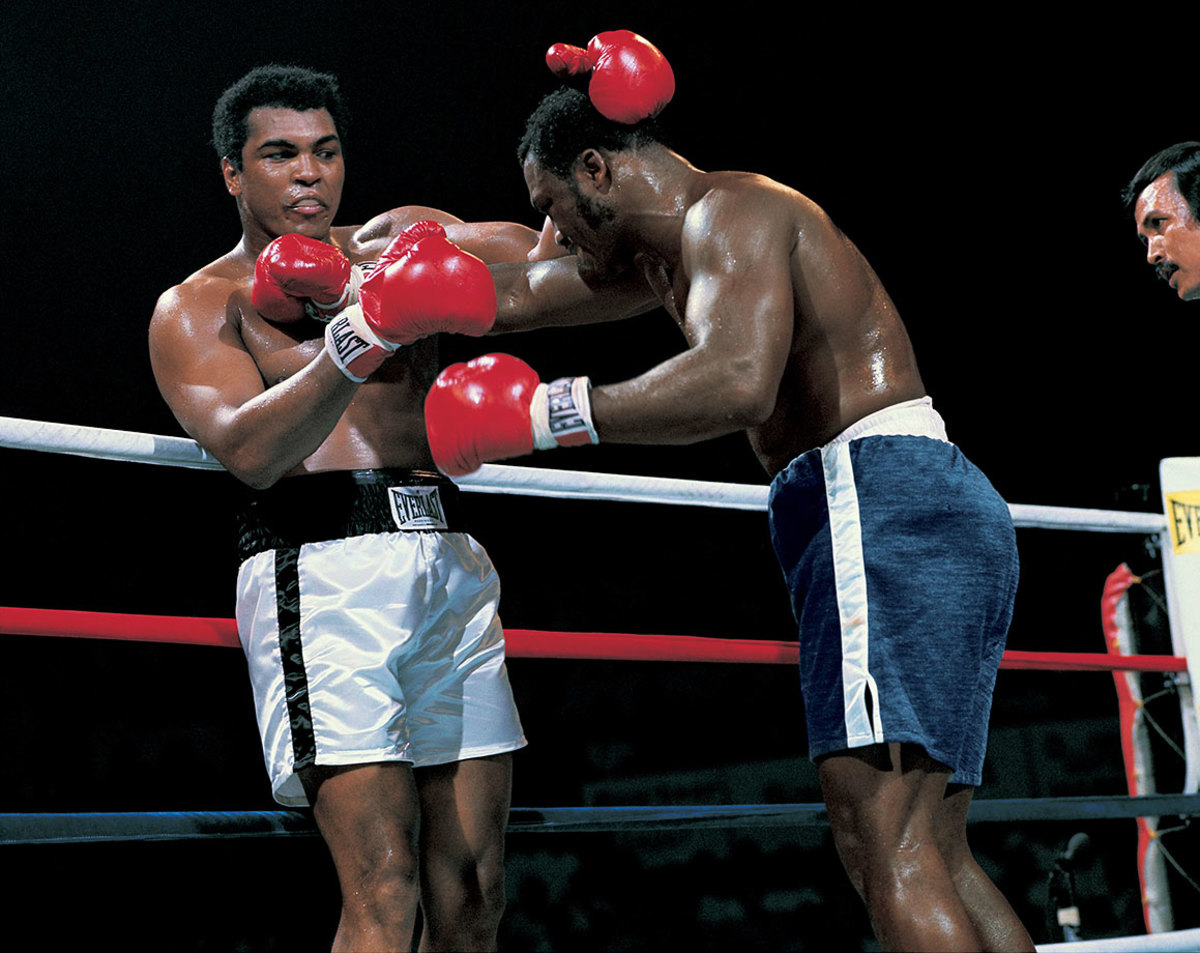

In cruelly efficient performance, Ali punished Patterson — who was hobbled by a painful back injury — seemingly toying with the former champ throughout the bout, hitting him at will and calling, "What's my name?" before finally winning on a 12th-round TKO.

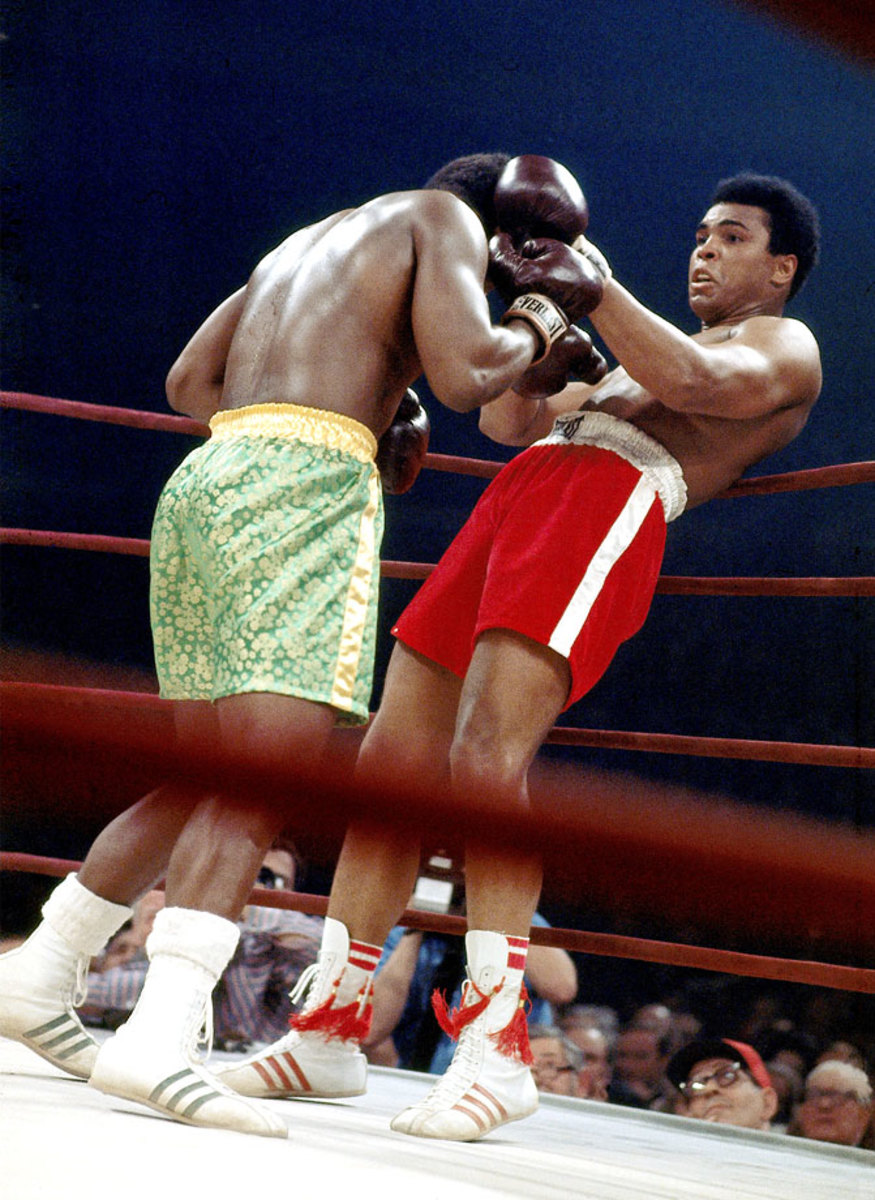

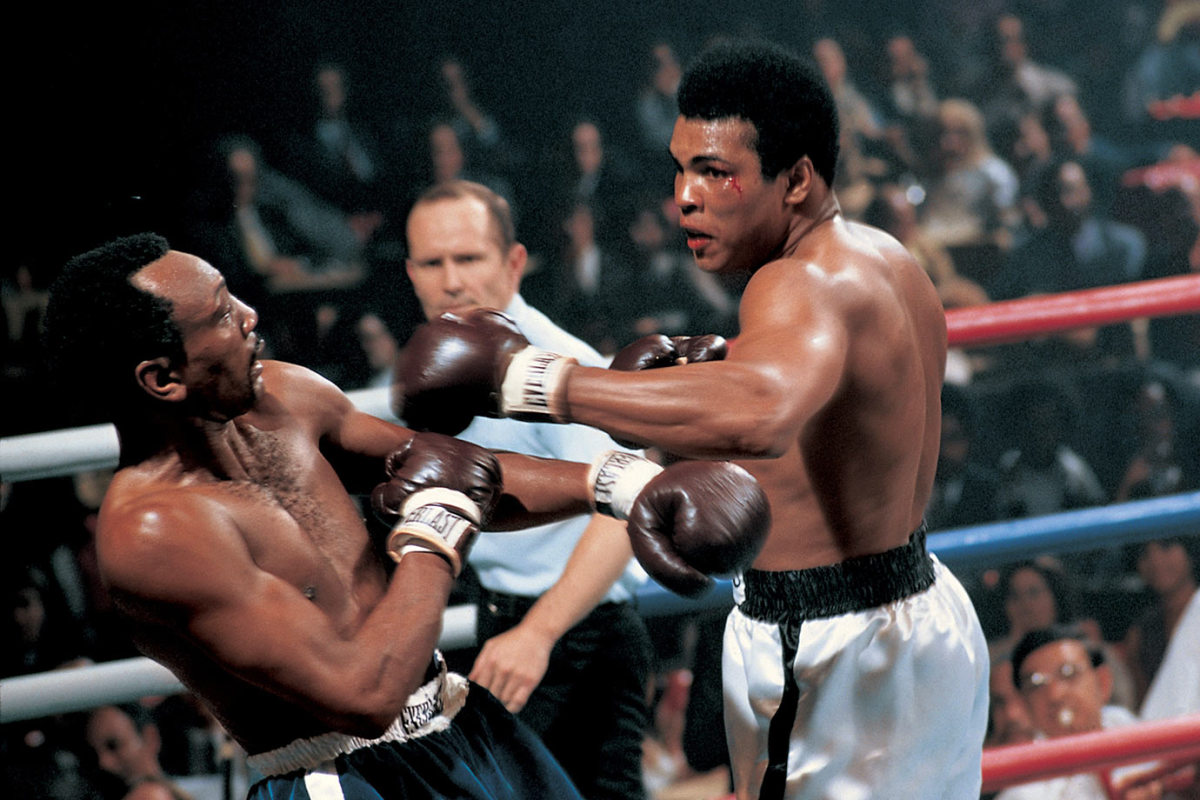

Capping off a five-fight campaign in 1966, Ali faced Cleveland Williams in the Houston Astrodome on Nov. 14. Known as the Big Cat, the heavily-muscled Williams was a power puncher who had racked up 51 knockouts in 71 fights. But he was also 33, barely recovered from a gunshot wound sustained the year before, and up against a young champion very much in his prime. Ali wasted little time in unleashing a withering attack.

Float and sting: In a display of speed and combination punching unmatched in heavyweight history, Ali overwhelmed Williams from the start. The challenger, here down for the third time in round 2, would be saved by the bell before referee Harry Kessler could count him out, but it would only postpone the inevitable.

Ali dropped Williams again early in the third round, and Kessler waved the mismatch over at 1:08 of the third.

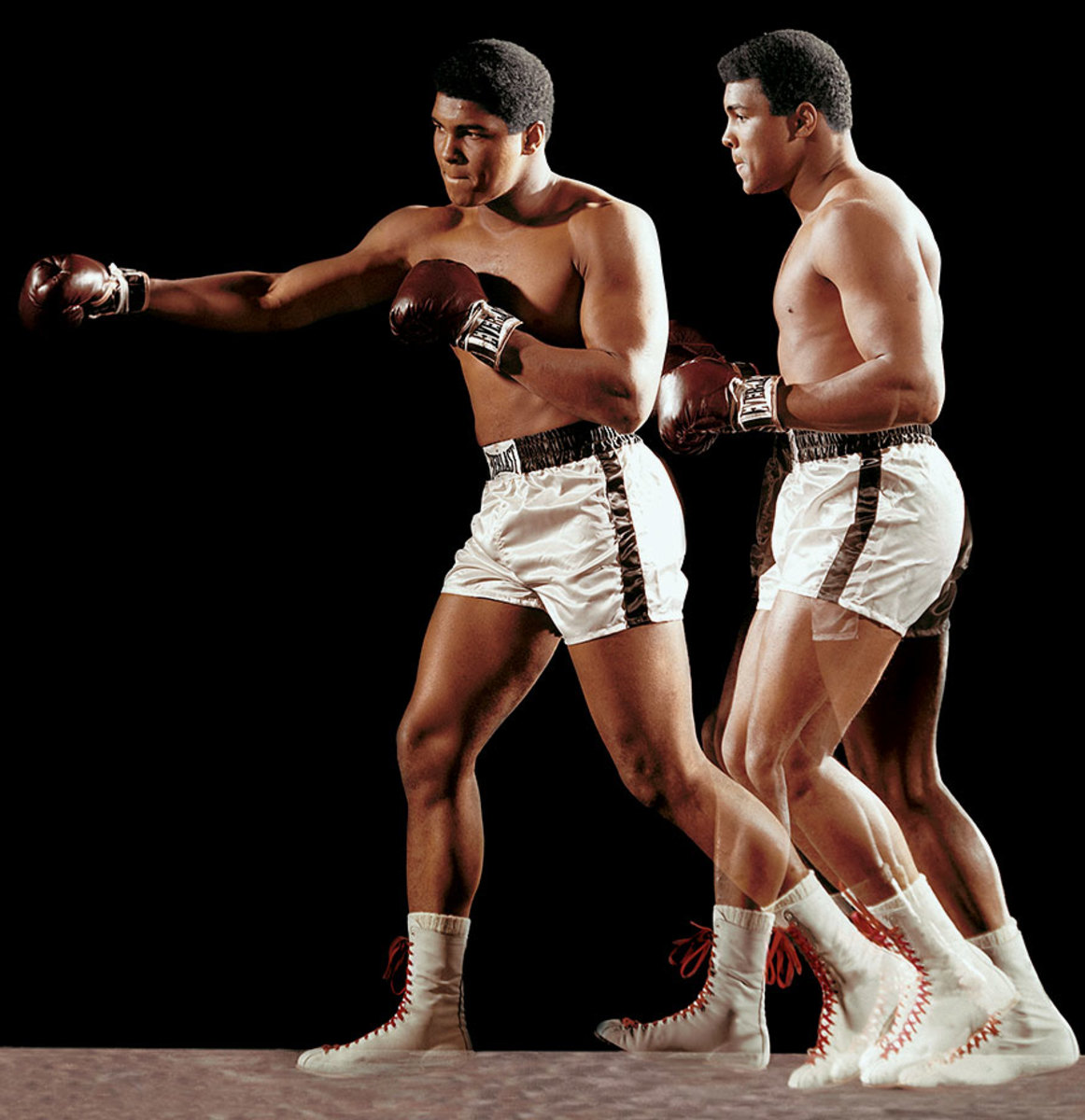

In a multiple-exposure portrait, Ali demonstrates his signature double-clutch shuffle during a photo shoot in December 1966.

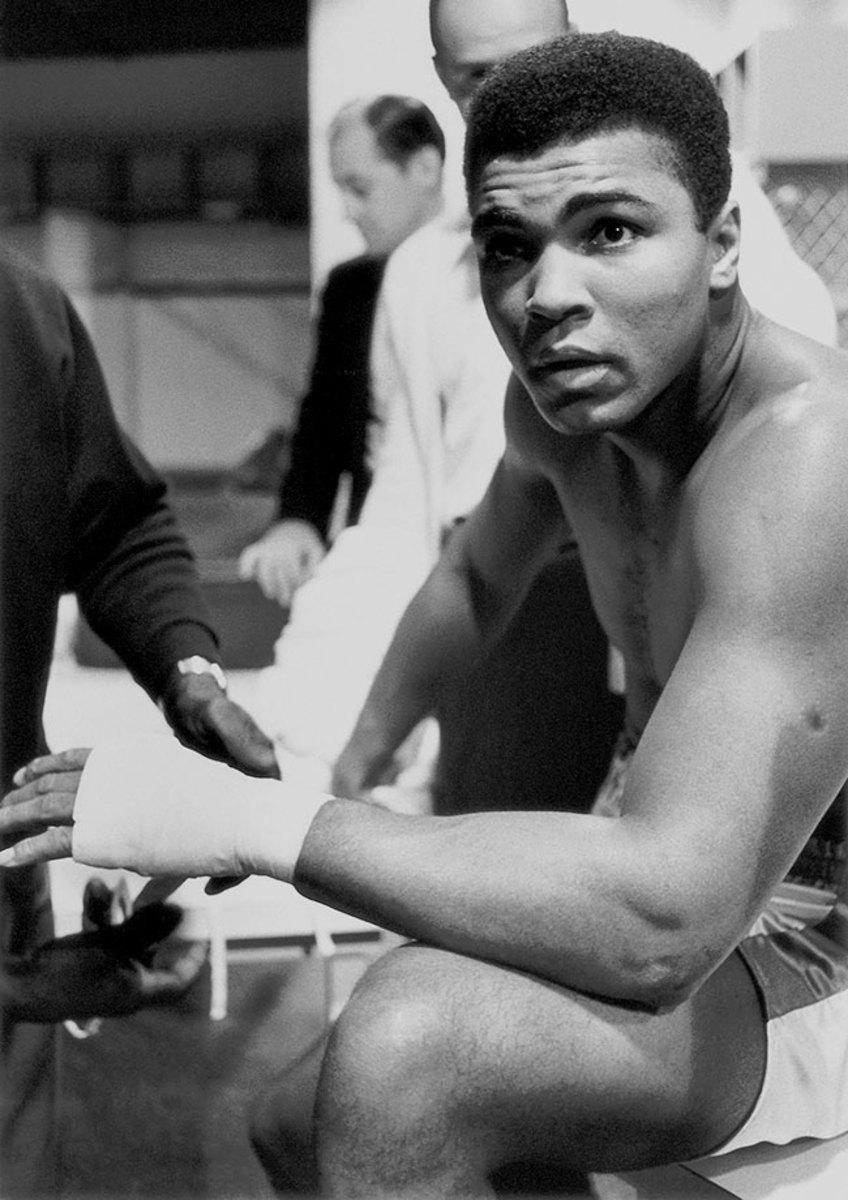

Ali sits in the locker room before his February 1967 fight against Ernie Terrell. Like Patterson before him, Terrell refused to call the champion by his Muslim name. Also like Patterson, he paid a stiff price, as Ali punished Terrell for 15 ugly rounds before winning by unanimous decision.

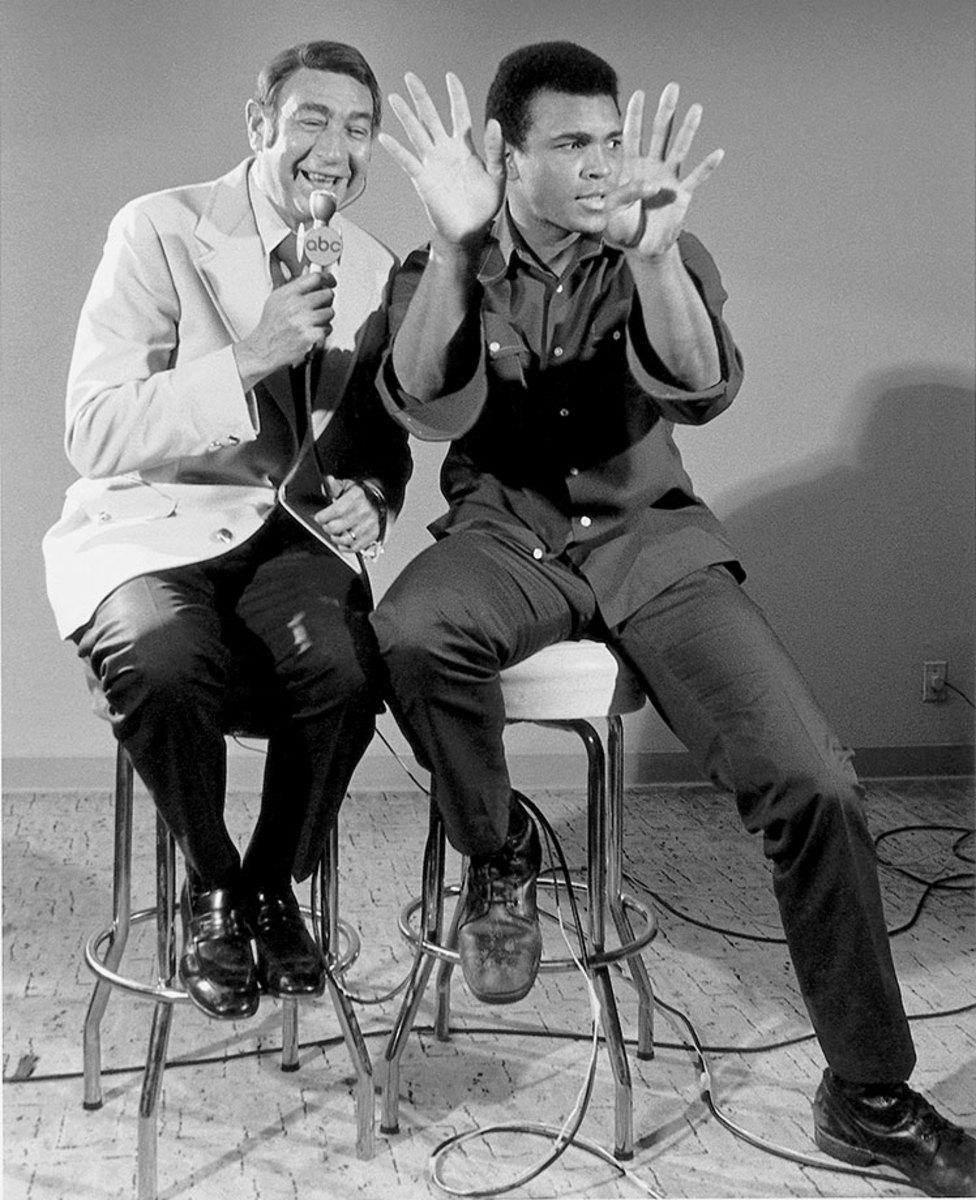

Outside the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in Houston in April 1967, Ali spoke to the press about his refusal to be inducted into military service. Among those on hand was ABC's Howard Cosell, who would be a staunch supporter of the fighter's stance. The decision cost Ali his boxing license and his heavyweight title, and he was sentenced to five years in prison but remained free pending an appeal.

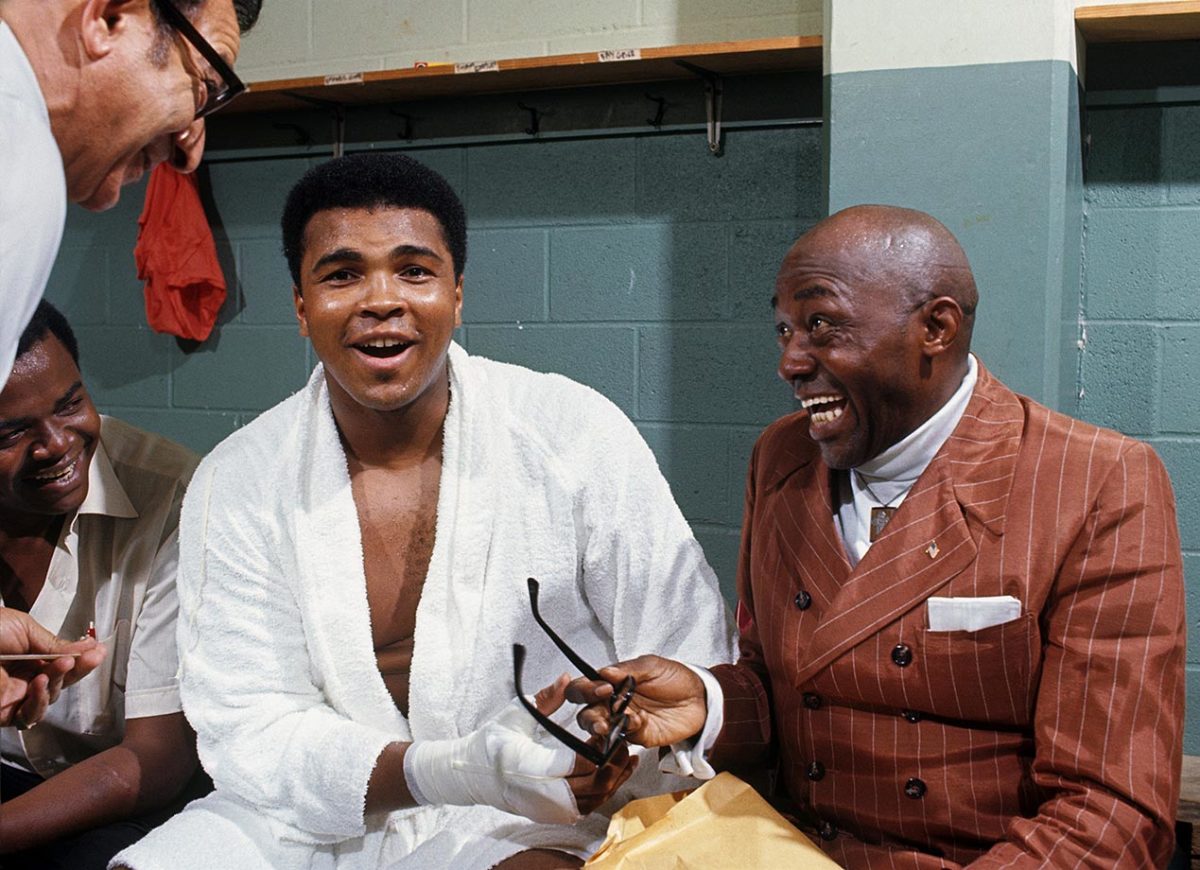

In professional exile for three and a half years because of his draft case, Ali sought to return to boxing in 1970. He began with a night of exhibition bouts at Morehouse College in Atlanta, where before going into the ring, he shared a locker room laugh with actor and comedian Lincoln Perry (right), better known by his stage name of Stepin Fetchit. The friendship between the two black icons would later be examined in an acclaimed play by Will Power, Fetch Clay, Make Man.

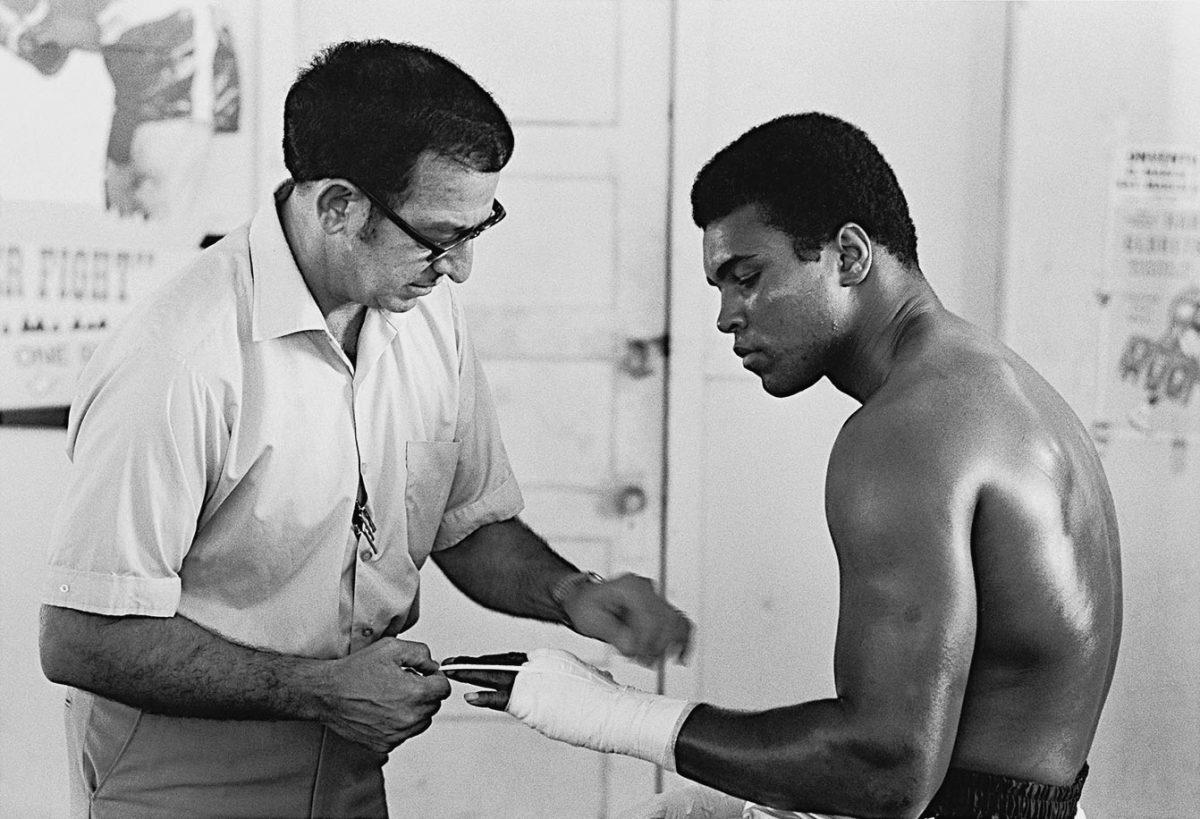

After the Atlanta Athletic Commission at last granted Ali a license, the deposed champion went back into serious training. He was, as ever, in the capable hands of trainer Angelo Dundee, here wrapping boxing's most famous fists at the 5th Street Gym in Miami in October 1970.

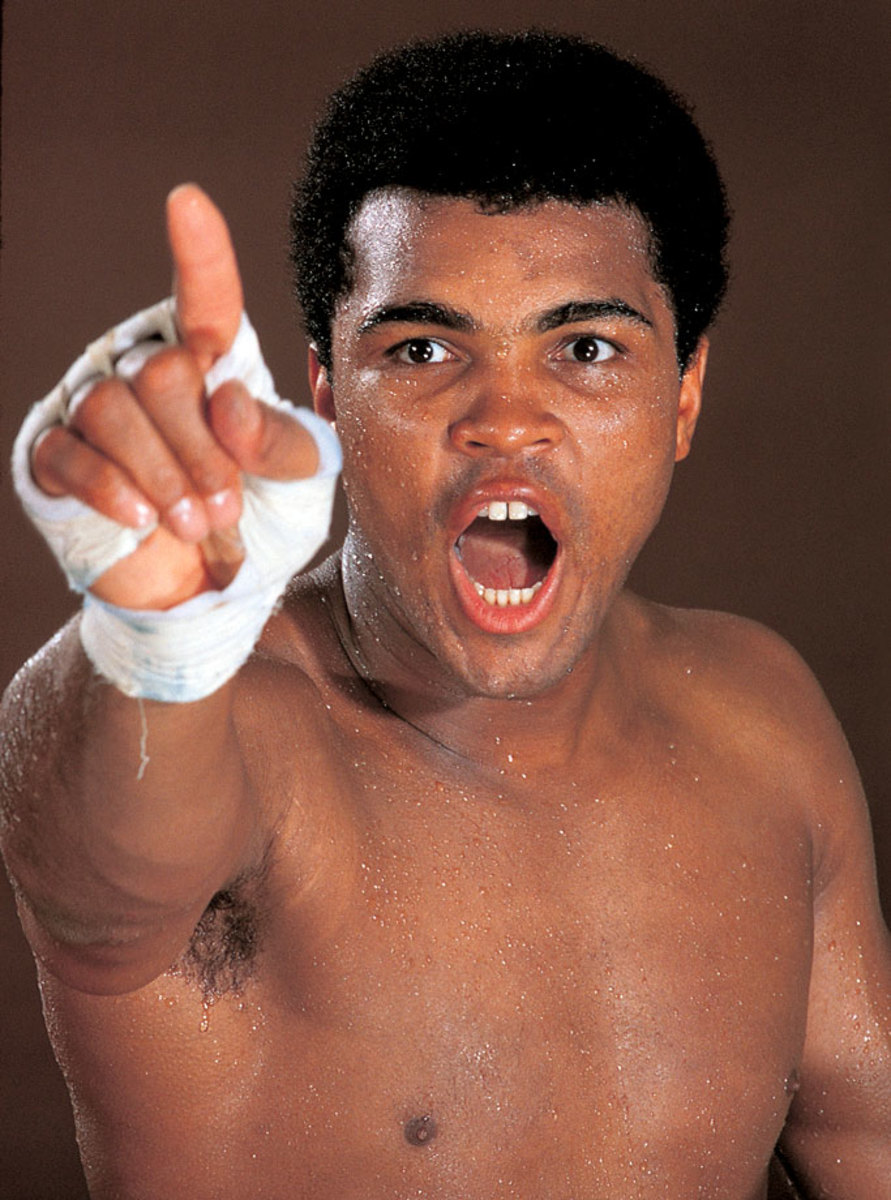

With his return to the ring scheduled for Oct. 26, 1970 in Atlanta, against dangerous contender Jerry Quarry, Ali made it clear to all who would listen that he was on a mission to reclaim the title that had been stripped of him.

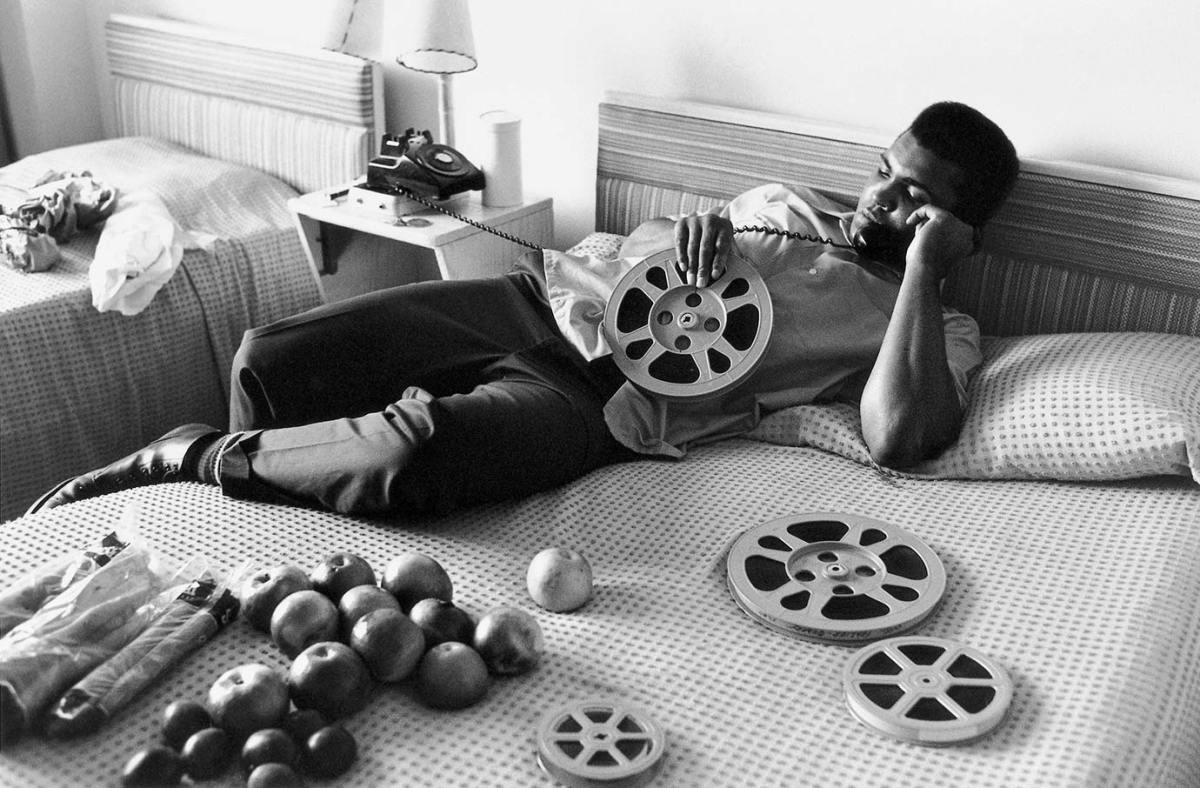

Reel to spiel: For the ever-loquacious Ali, even a rare moment of down time — like this afternoon in 1970 in a Miami hotel room — was a chance to do some talking.

Despite Ali's long layoff, his comeback campaign would include no easy tune-up bouts. He stopped Quarry in three rounds on Oct. 26, 1970, then, just six weeks later — an unthinkably short interlude by today's standards — took on Argentine contender Oscar Bonavena in Madison Square Garden. Here, Ali fires a right at the rugged and awkward Bonavena, who took the fight to the former champion all night.

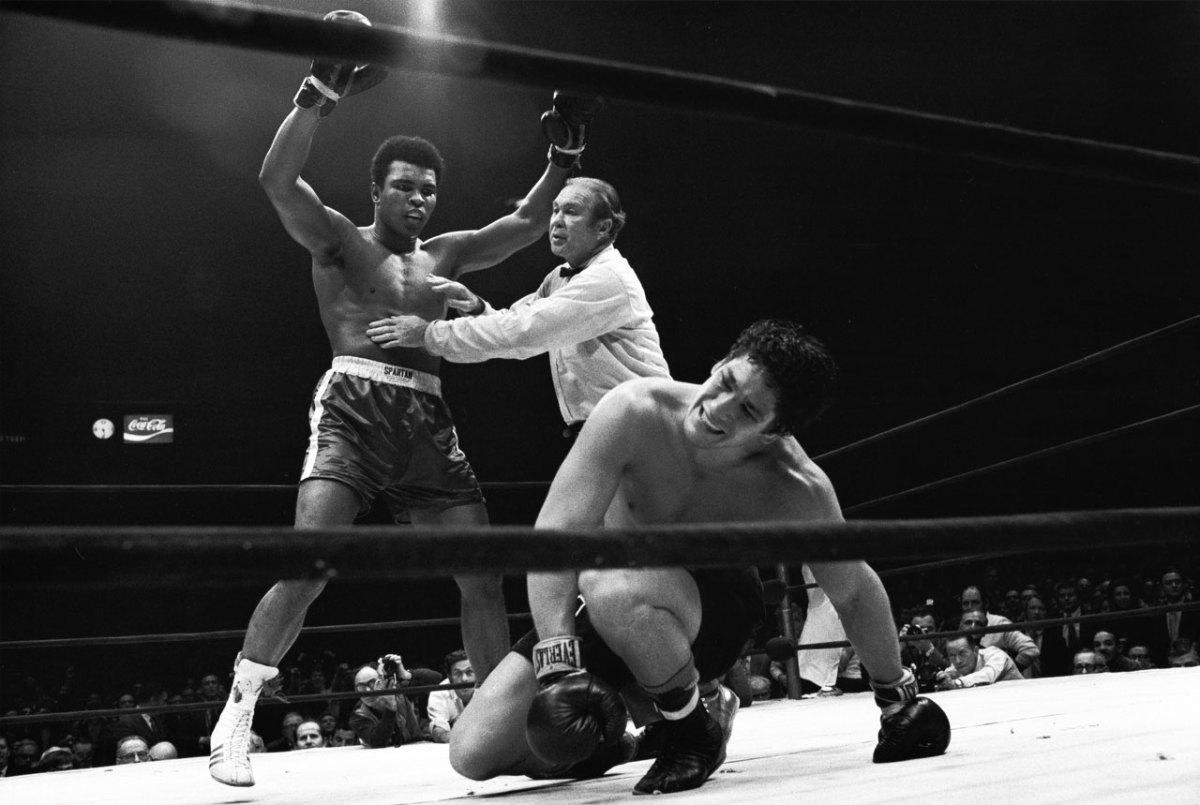

After a long, often sloppy bout, Ali — here being held back by referee Mark Conn — produced one of the most dramatic finishes of his career, dropping Bonavena three times in the 15th and final round to automatically end the fight. The win cleared the way for a showdown with Joe Frazier, the man who had taken the heavyweight title in Ali's absence.

On the night of March 8, 1971, the eyes of the world were on a square patch of white canvas in the center of Madison Square Garden. There, Ali and Joe Frazier met in what was billed at the time simply as The Fight, but has come to be known, justifiably, as the Fight of the Century. For 15 rounds the two undefeated heavyweights battled at a furious pace, with each man sustaining tremendous punishment. In the end Frazier prevailed, dropping Ali in the final round with a tremendous left hook to seal a unanimous decision and hand The Greatest his first loss in 32 professional fights.

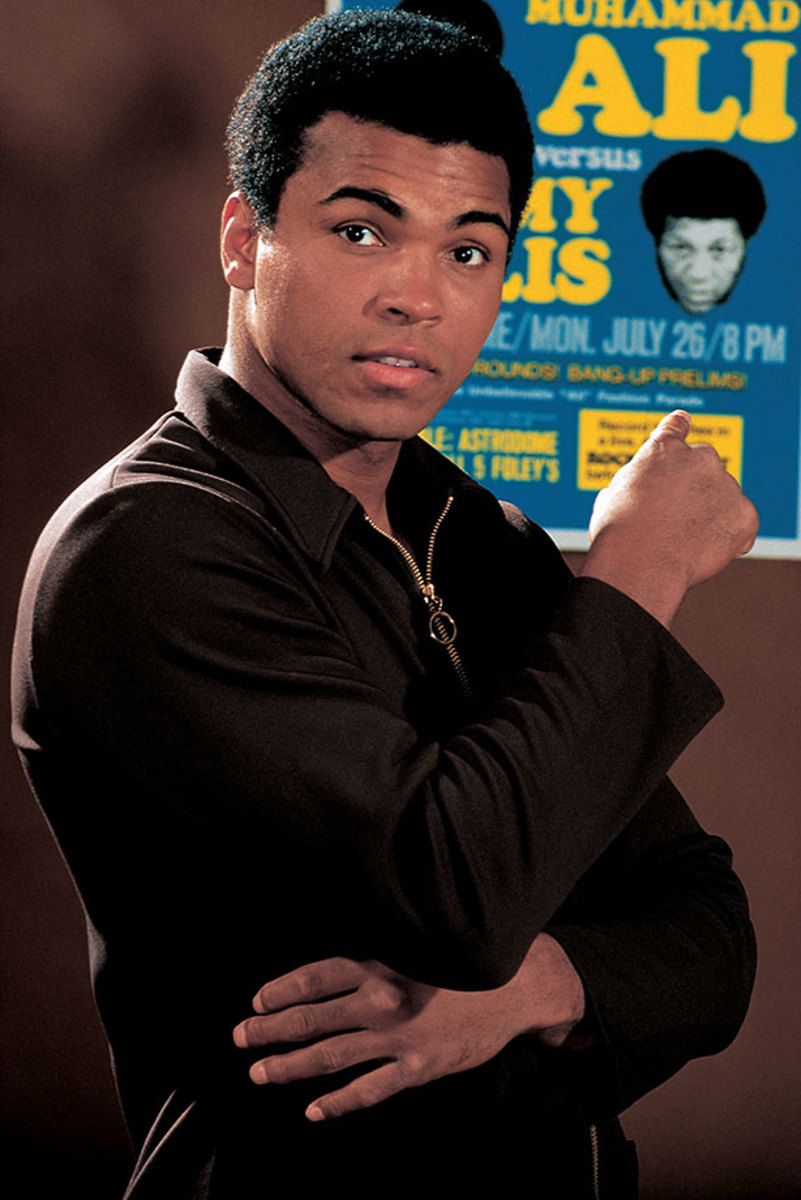

Ali poses with the fight poster for his upcoming fight against Jimmy Ellis during a photo shoot in July 1971. Ellis was an old friend of Ali's — both were trained by Angelo Dundee — and knew his fighting style well from many rounds of sparring.

For those sportswriters lucky enough to cover Ali on a regular basis, each day brought surprises and, more often than not, plenty of laughs. of Trainer Drew Bundini Brown helps Ali train for his fight against Ellis. Ali won the bout by technical knockout in the 12th round to claim the vacant NABF heavyweight title.

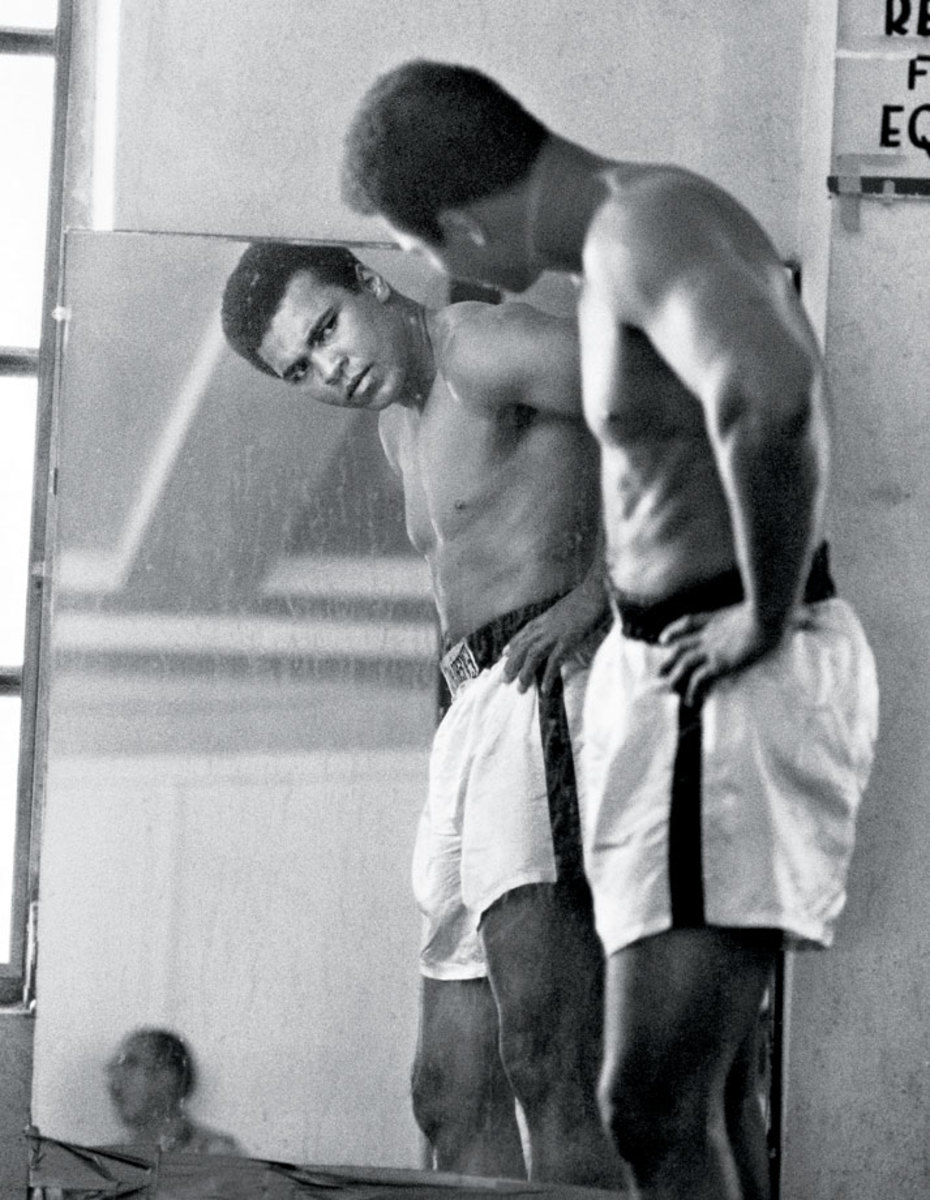

The man in the mirror stares back as Ali examines himself while training for a fight in 1972. He won all six of his fights that year.

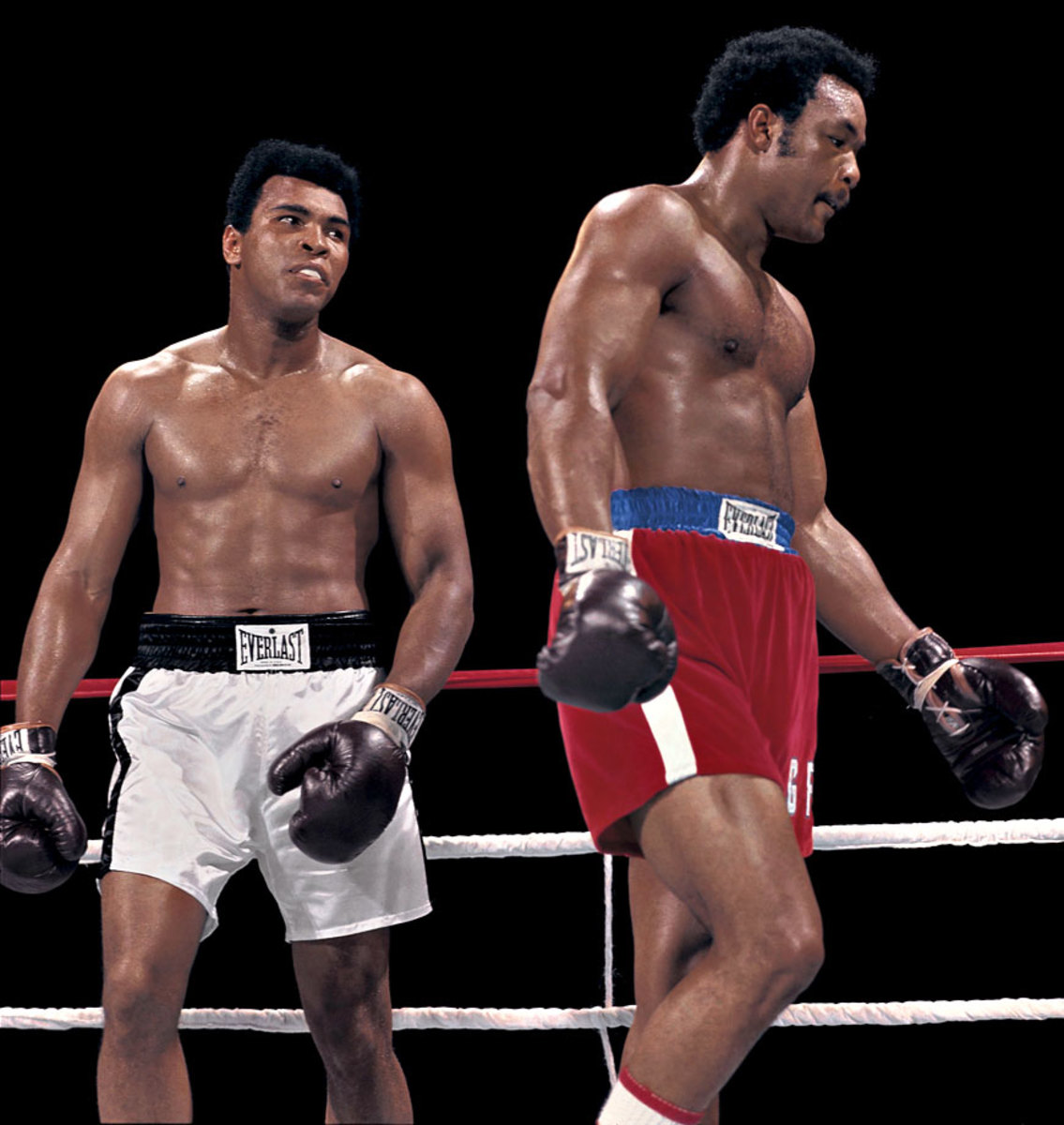

The Louisville Lip stands next to George Foreman before Ali's fight versus Jerry Quarry in June 1972. Ali won by technical knockout in the seventh round. Foreman at the time was 36-0. Ali would not get his shot against Foreman for more than two years.

Ali throws a left hook at Bob Foster in their 1972 fight at Stateline, Nev. Although Ali knocked Foster out, Foster did leave his mark: a cut above Ali's left eye, his first as a professional.

Foster lies on the canvas after getting knocked down by Ali. Ali knocked Foster down four times in the fifth round and twice more in the seventh round before he was finally counted out after Ali knocked him down again in the eighth round.

Ali sits with sportscaster Howard Cosell before his fight with Joe Bugner in February 1973. Although unable to knock Bugner out, Ali won comfortably by unanimous decision.

Ali hits a speed bag while warming up for his bout with Bugner in Las Vegas. Ali prepared ferociously for the fight, training 67 rounds the week leading up to the fight, including six rounds the day before the fight.

In a lighter pre-fight moment, Ali poses for a portrait wearing a hat in his dressing room before the match with Bugner.

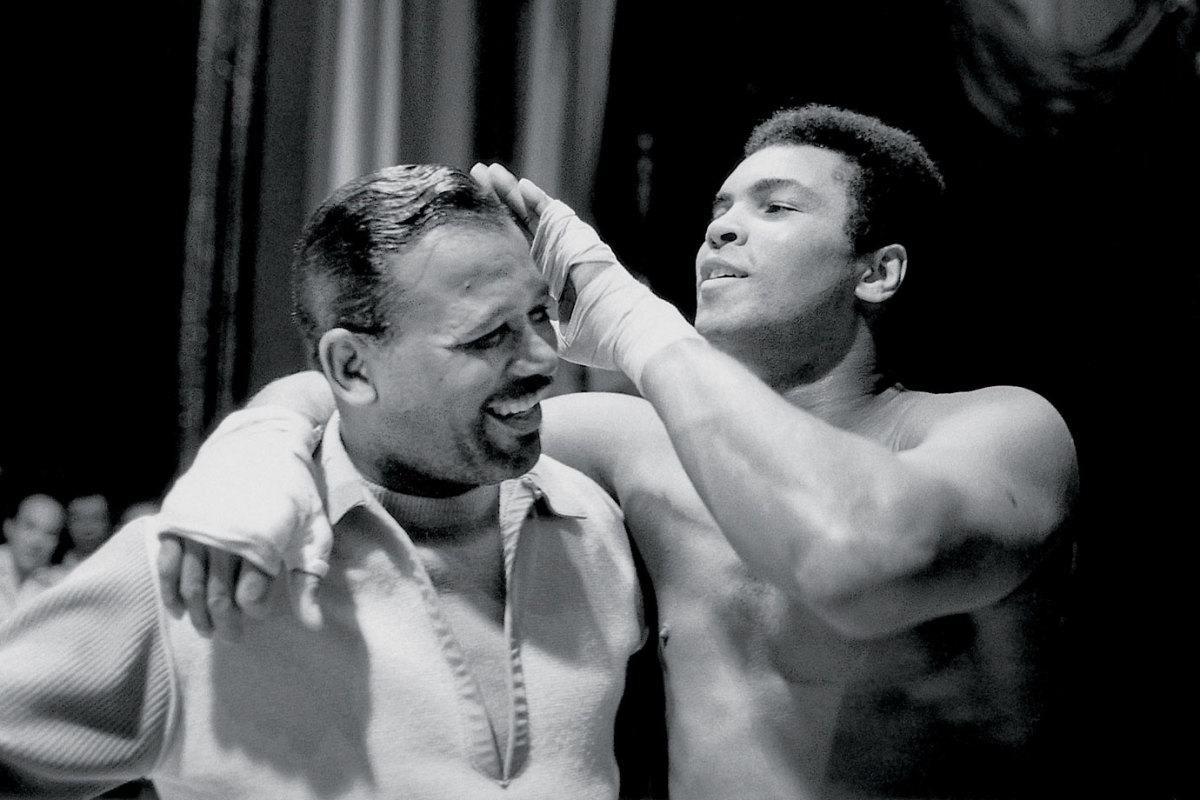

Ali plays with Sugar Ray Robinson's hair in the locker room before his bout with Bugner. The former welterweight and middleweight champion was Ali's childhood idol.

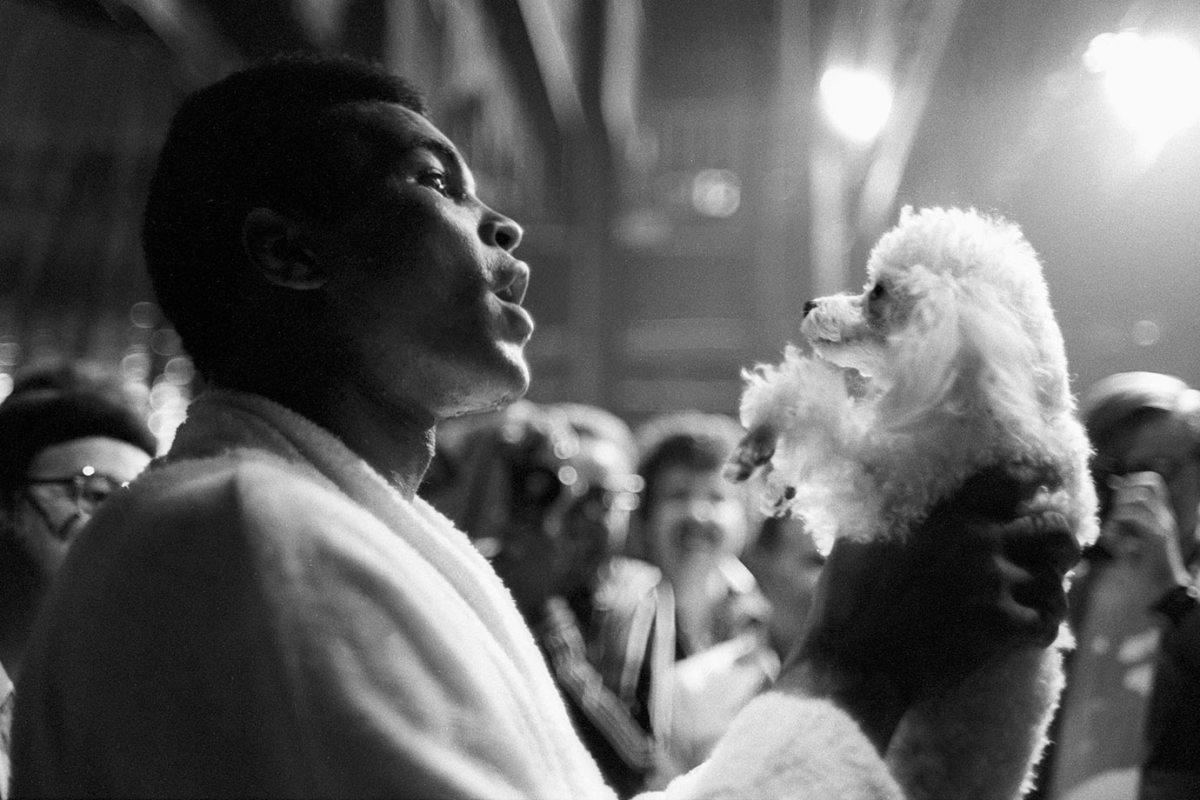

Before the fight with Bugner, Muhammad Ali enjoys a relaxed moment with a poodle at Caesars Palace Hotel. He won the fight with Bugner by unanimous decision.

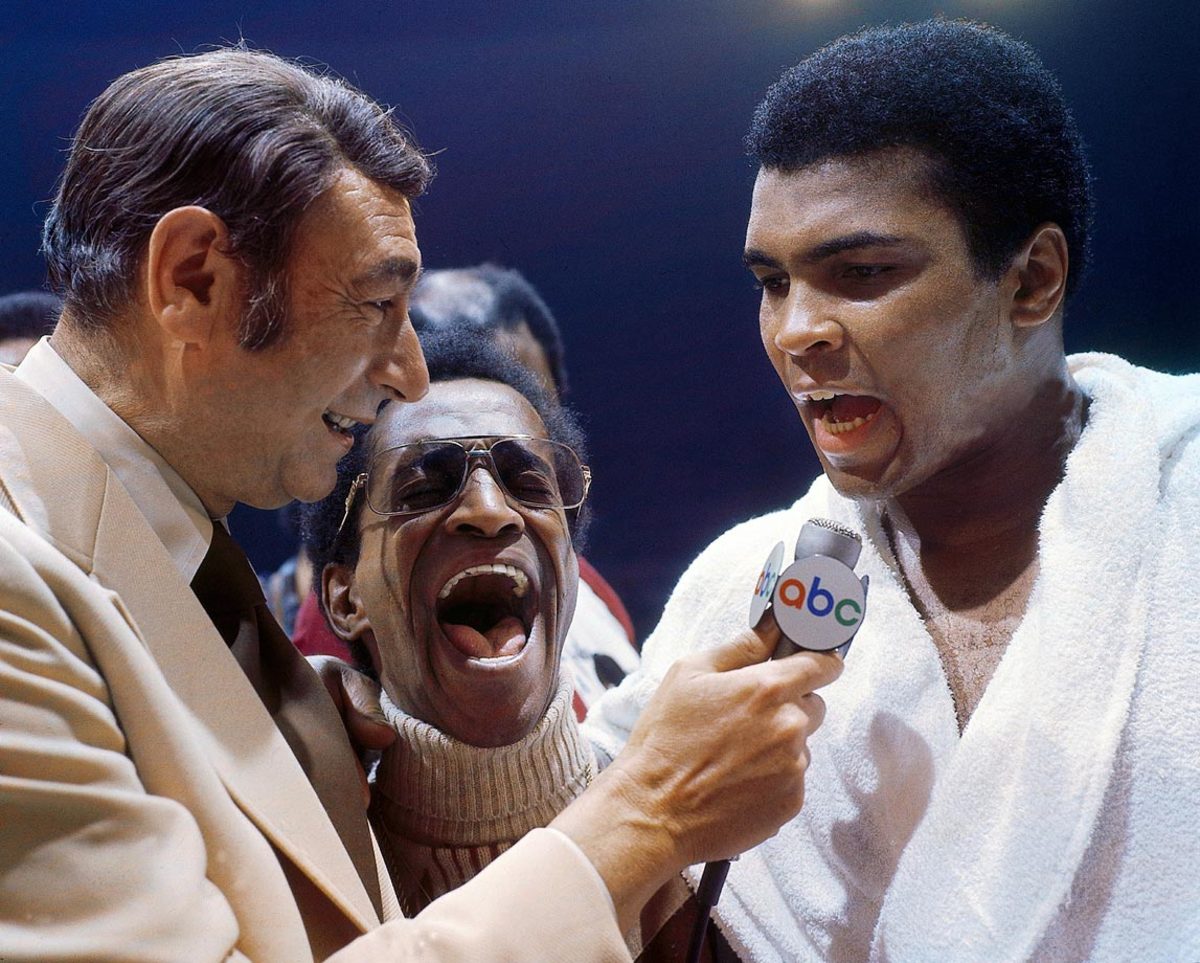

Howard Cosell interviews Ali, with entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. in the middle, after his victory over Joe Bugner by unanimous decision in. Although the fight was never in jeopardy of getting away from him, Ali praised Bugner's legs and said he could be a champion in a few years.

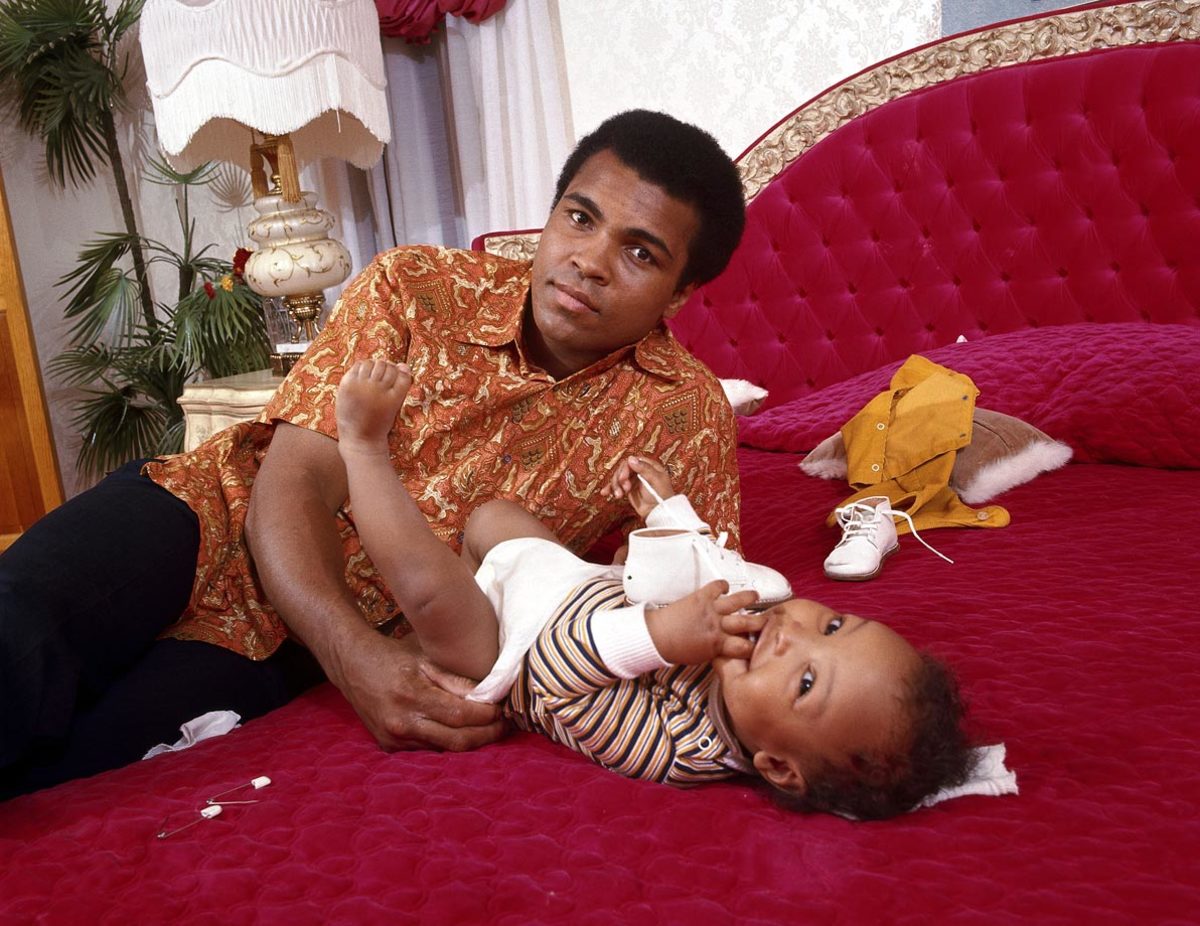

Ali changes the diaper of his son in his bedroom during a photo shoot at the family's home in April 1973. Ali had suffered a broken jaw less than a month earlier in his fight against Ken Norton.

In the wake of his split decision loss to Norton, Ali plays with his son in his bedroom at home in Cherry Hill, N.J.

Ali kisses his daughter Jamillah outside of their home following the loss to Norton, just the second defeat of his career.

The Ali family standing outside their New Jersey home. To the right of Muhammad Ali are his twin daughters, Jamilllah and Rasheda, daughter Maryum and his wife, Khalilah, holding their son Ibn Muhammad Ali Jr.

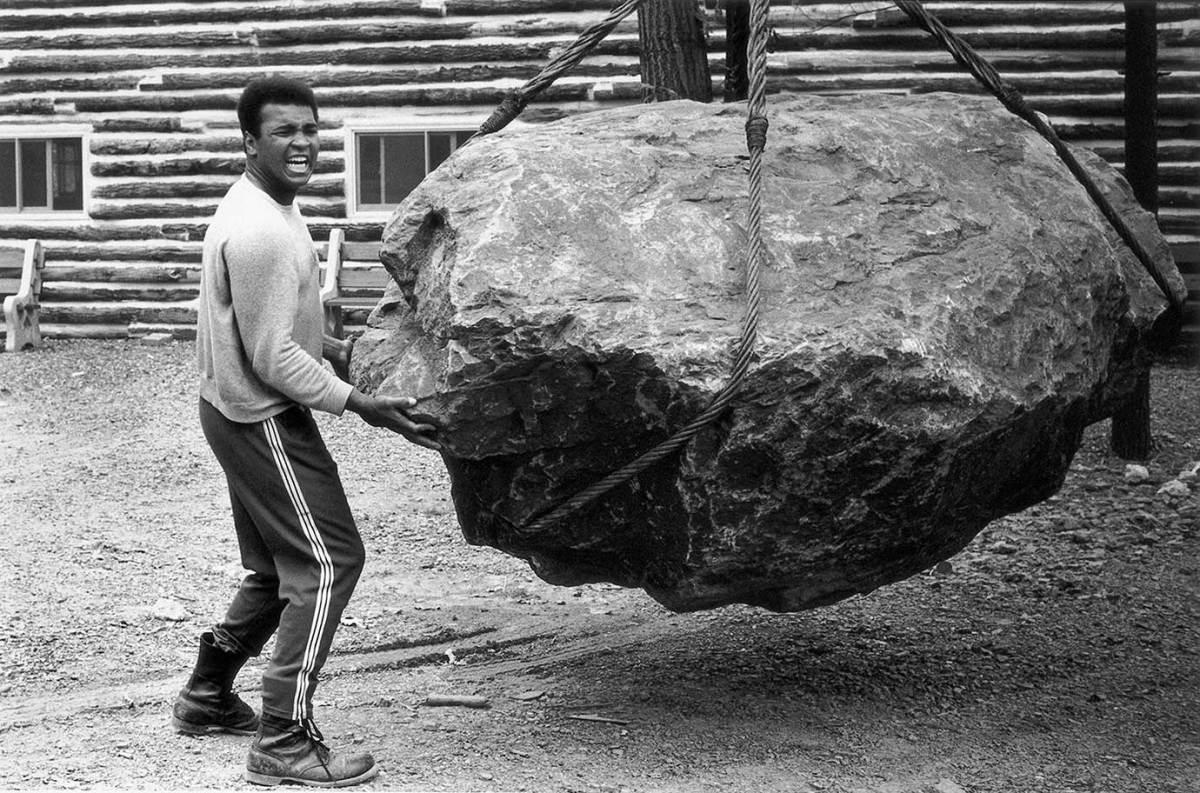

At his training camp cabin, Ali pushes a boulder during a photo shoot in Deer Lake, Penn., in August 1973. Ali was training for his rematch against Ken Norton, who broke his jaw five months earlier.

Ali chops wood at his cabin in Deer Lake. He referred to the training camp as "fighter's heaven" and used it to prepare for fights away from the spotlight.

The fighters weigh in on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson ahead of Ali and Ken Norton's September 1973 fight.

Johnny Carson listens to Ali on the Tonight Show three days before his rematch with Norton. Ali would avenge his earlier loss to Norton, winning a narrow split decision.

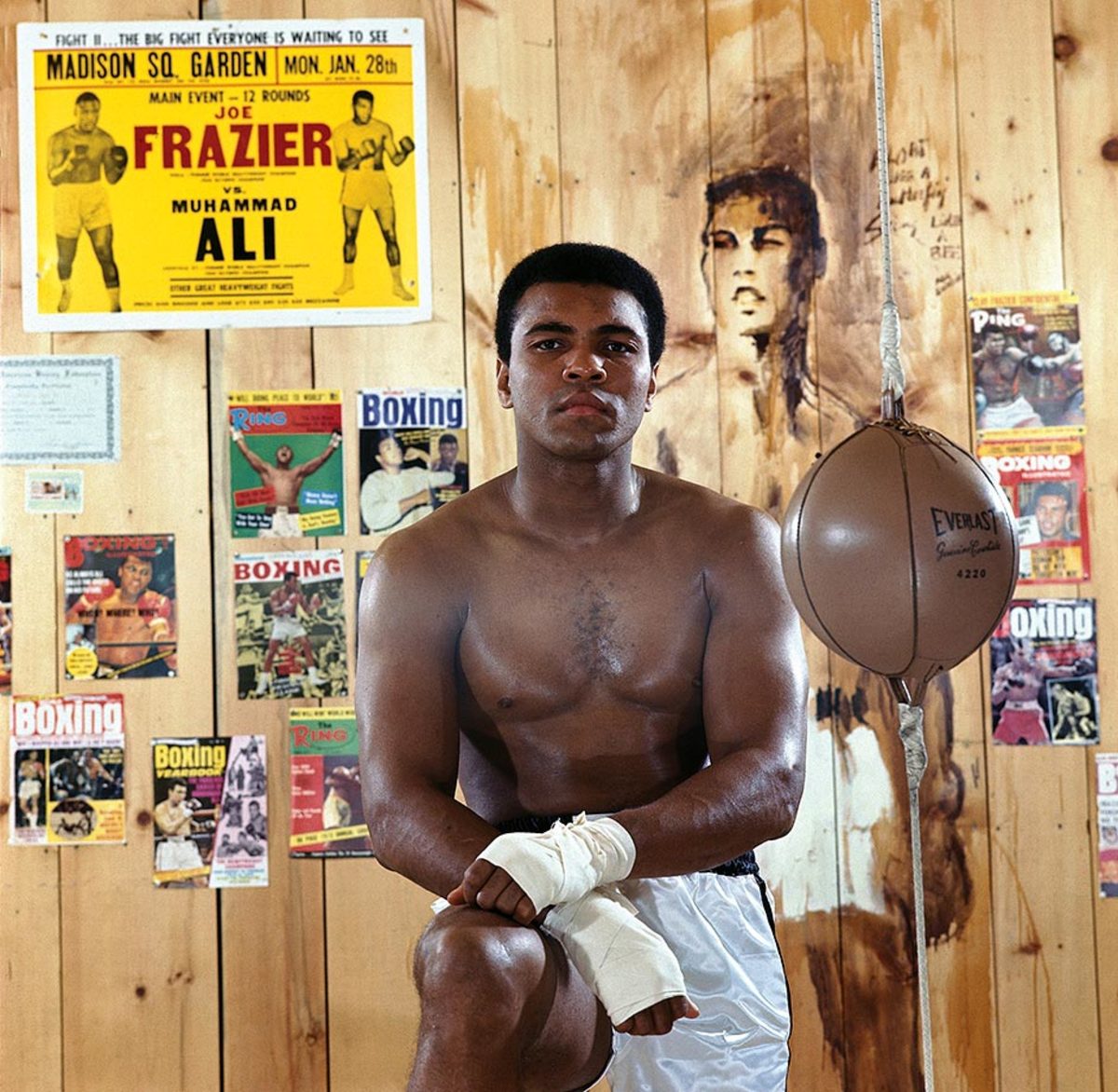

Ali poses in front of posters and magazine covers from throughout his career at his training camp cabin in Deer Lake in 1974.

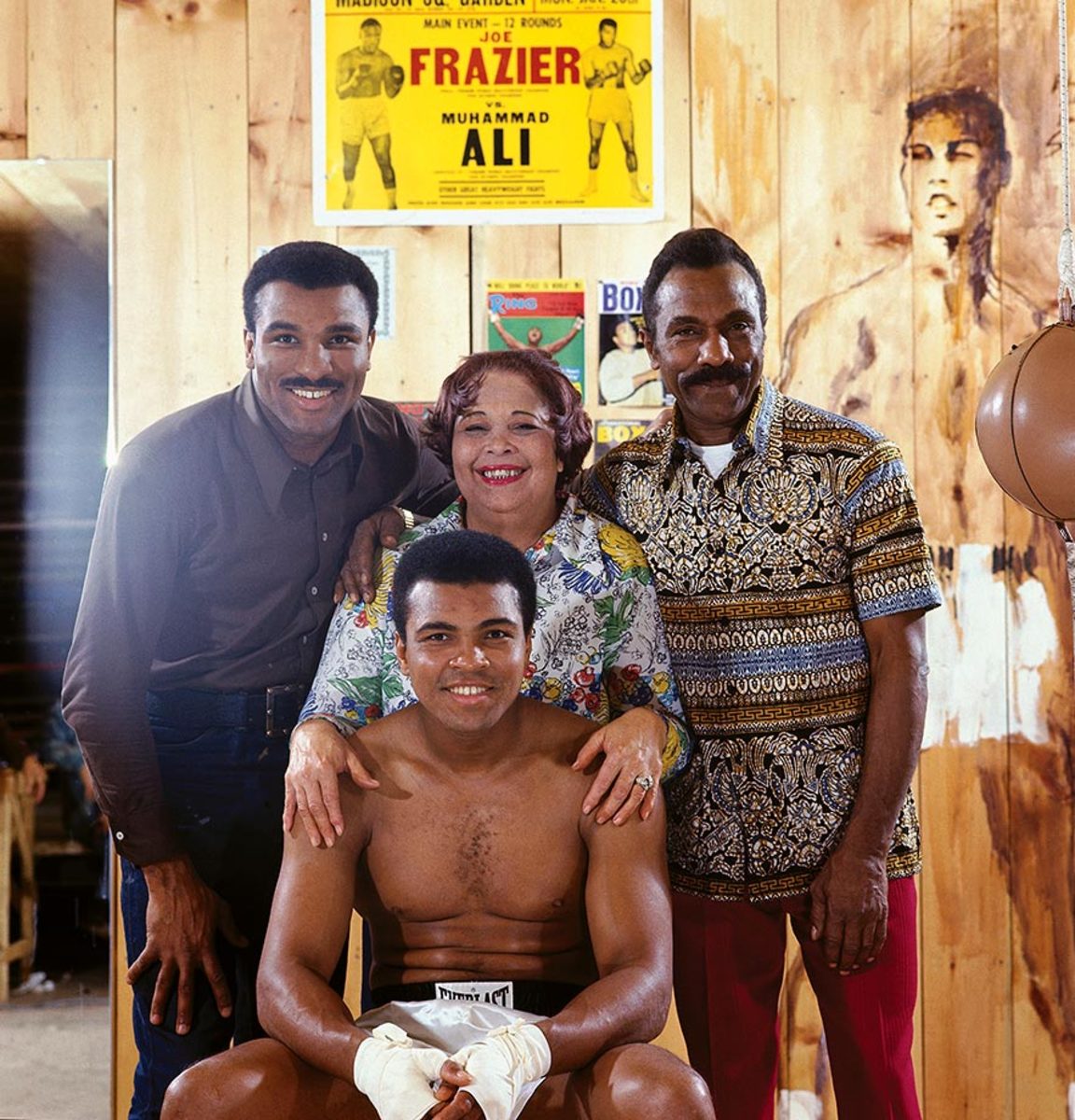

Ali poses with members of his family in front of a poster from his first fight with Joe Frazier. Ali's brother, Rahman Ali; mother, Odessa Clay; and father, Cassius Clay Sr. stand behind the boxer.

Less than three weeks before his rematch with Joe Frazier on Jan. 28, 1974, Ali wraps his hands while wearing a sauna suit at his training camp cabin.

Ali holds a newspaper at his cabin in January 1974. He is pointing to a headline that reads, "Frazier On Ali, I Think He's Crazy." Ali and Frazier fought for the second time later that month with Ali winning by a unanimous decision.

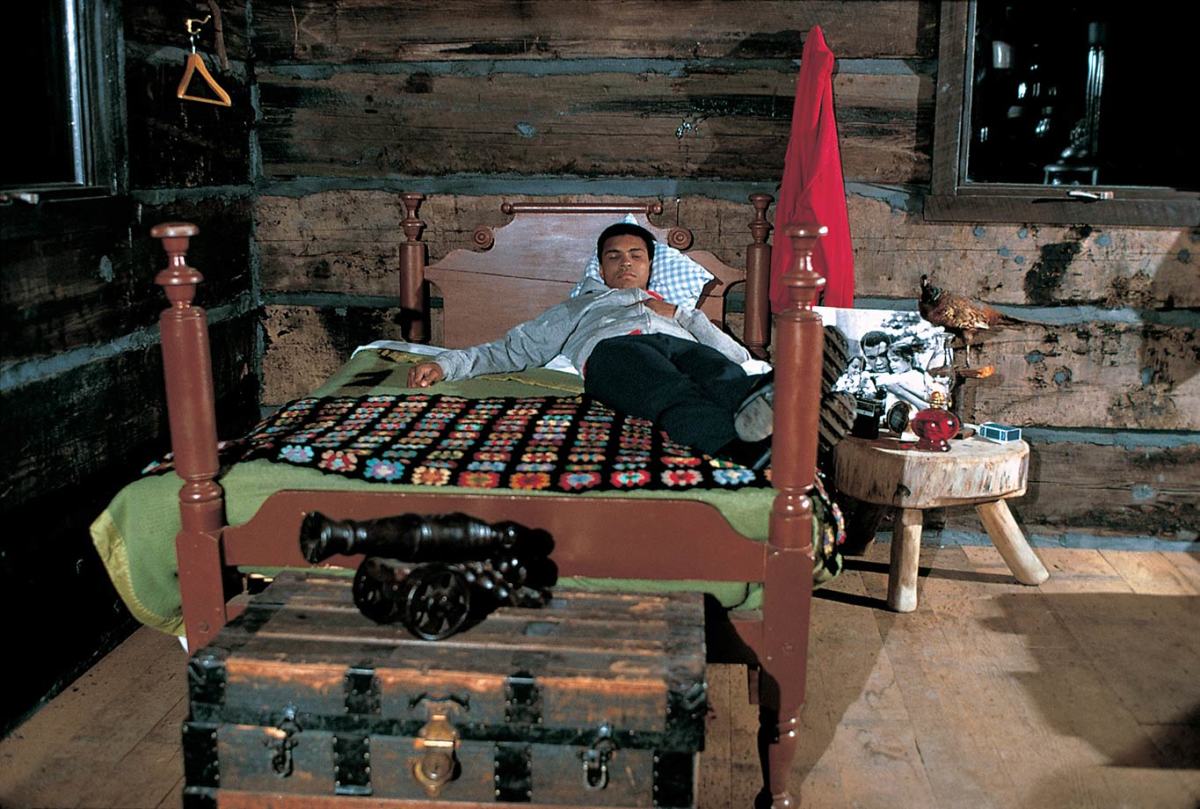

Ali lies on his bed at his cabin during the January 1974 photo shoot.

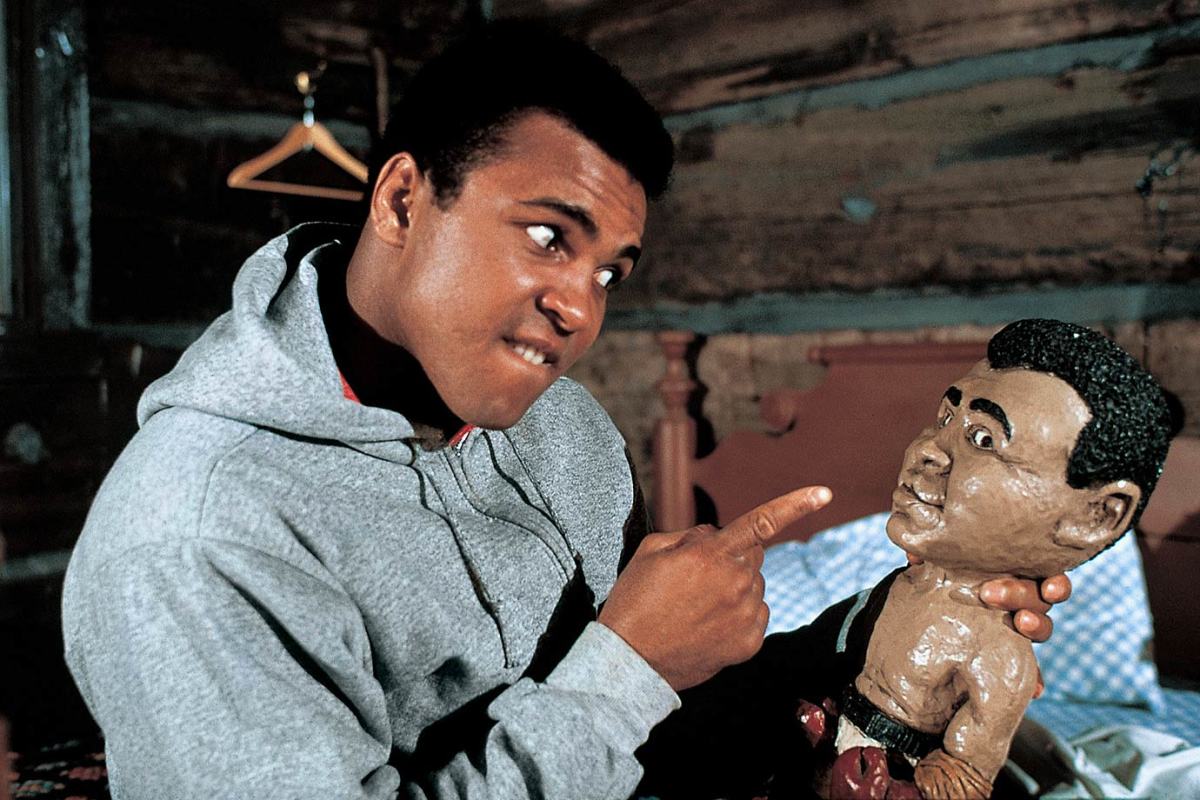

His smaller incarnation stares straight back as Ali plays with a doll of himself during the same 1974 shoot at his training camp cabin.

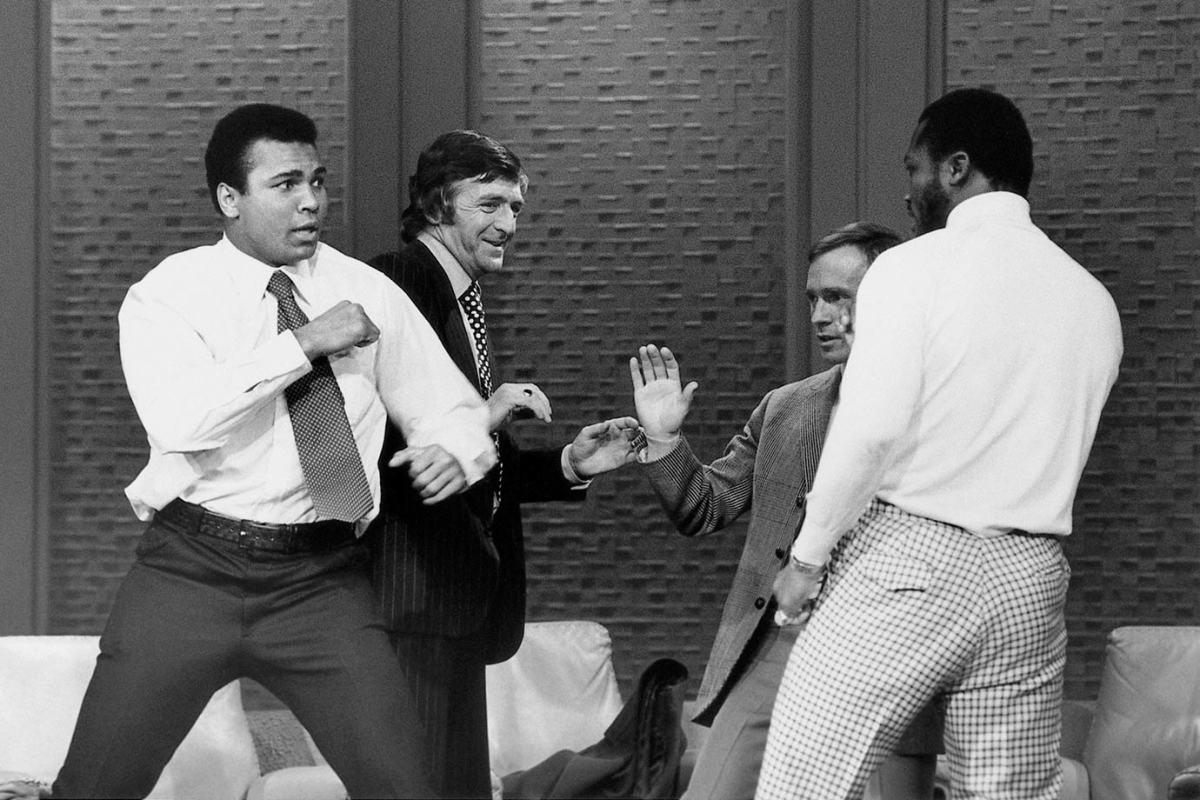

Ali and Joe Frazier fight on the set of The Dick Cavett Show while reviewing their 1971 bout in advance of their 1974 rematch. Ali called Frazier ignorant, to which Frazier took exception. As the studio crew tried to calm Frazier down, Ali held Frazier by the neck, forcing him to sit down and sparking a fight. The television set fight amped up anticipation of their January 1974 bout.

Exploring a different side of the sport, Ali broadcasts the fight between George Foreman and Ken Norton in March 1974. Foreman won the fight by technical knockout in the second round, setting up the showdown with Ali in Zaire.

Ali jumps rope at the Salle de Congres in Kinshasa, Zaire, while training for his heavyweight title fight against George Foreman. Both Ali and Foreman spent most of the summer of 1974 training in Zaire to adjust to the climate.

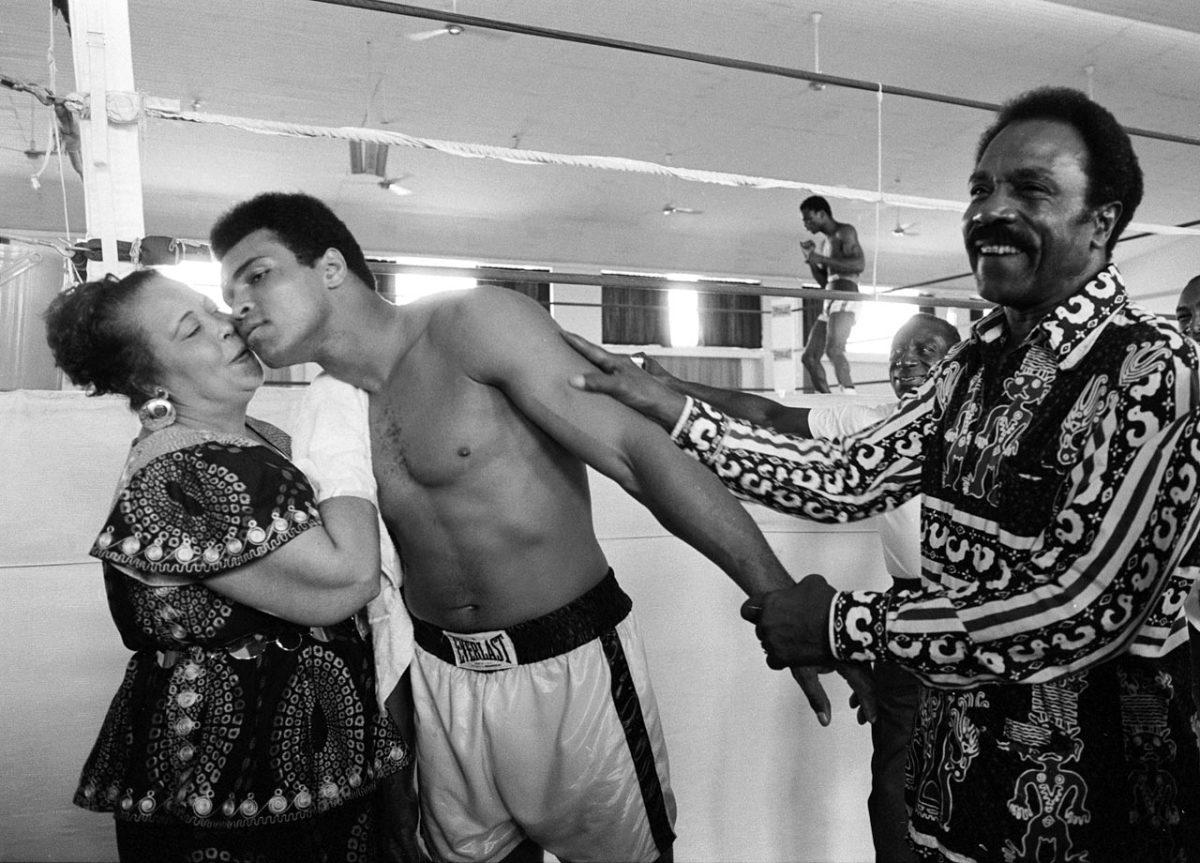

While training before his fight with George Foreman, Ali kisses his mother, Odessa Clay, while his father, Cassius Clay Sr., looks on. Ali's superior strategy and ability to take a punch led him to his upset victory as he absorbed body blows from Foreman before he responded with powerful combinations to Foreman's head.

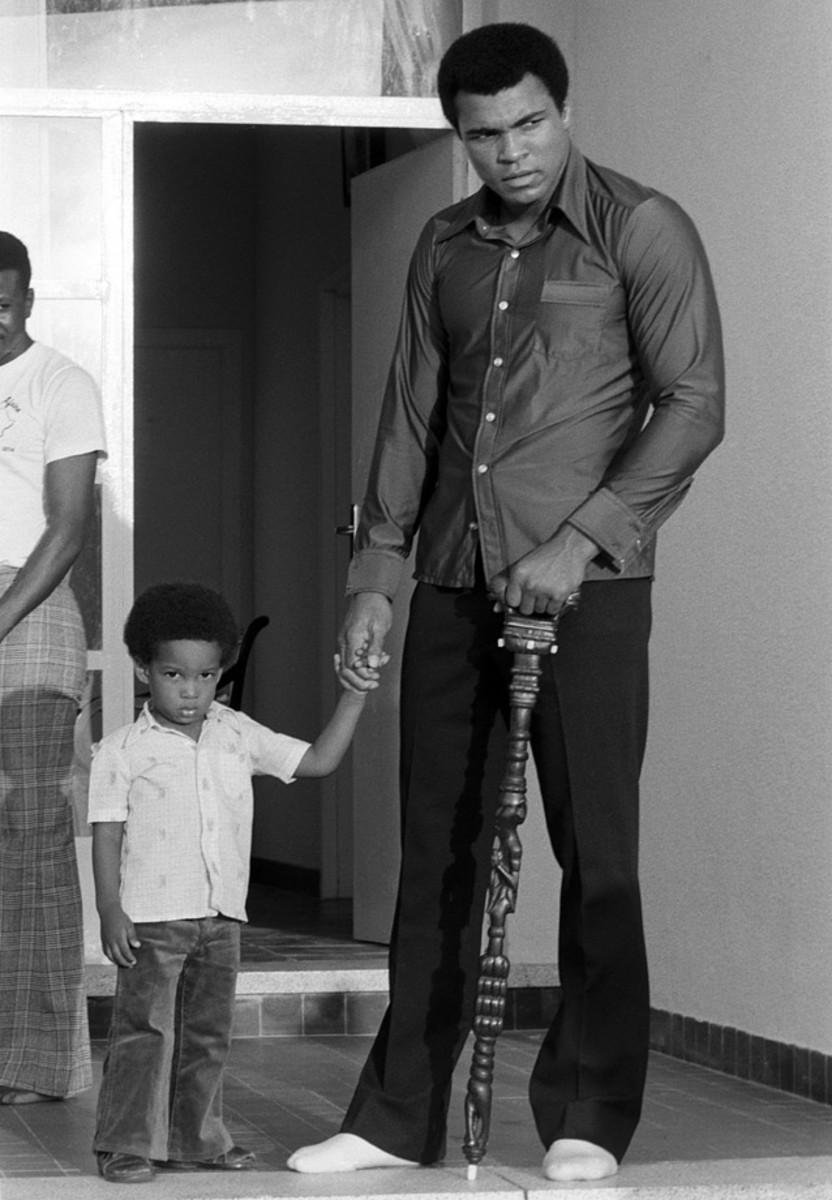

Four days before the fight, Ali holds the hand of his son Ibn in Zaire. Ali successfully courted the favor of the Zaire crowd, prompting chants of "Ali bomaye!" — translated as "Ali, kill him!"

Ali poses in front of the Le Militant statue at the presidential complex that was the site of Ali's January heavyweight title bout with Foreman. The fight was originally set for a month earlier, but Foreman suffered a cut near his eye during training, forcing a delay.

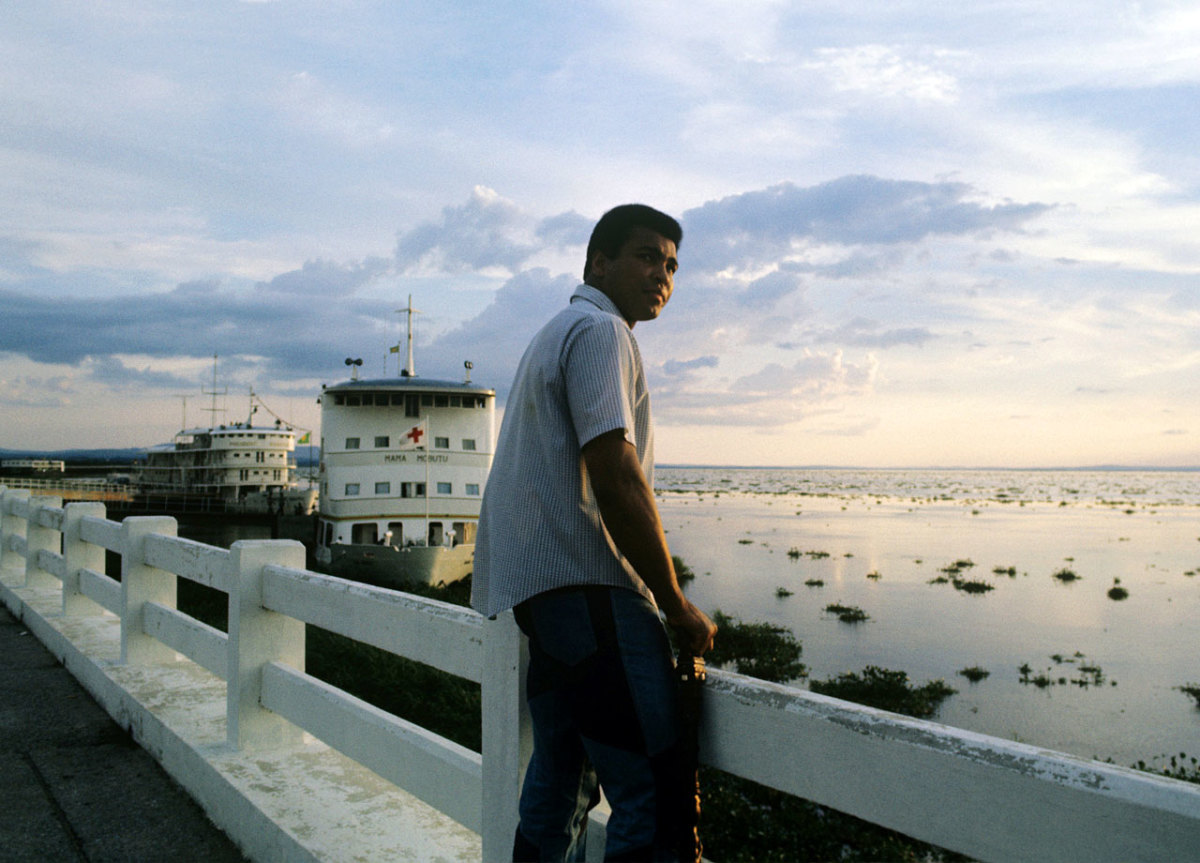

Ali stands against the railing on the River Zaire watching the sunset four days before the Rumble in the Jungle. The fight was sponsored by Zaire to achieve the $5 million purse promoter Don King had promised both Ali and Foreman.

Before employing his famous rope-a-dope strategy against Foreman, Ali makes a face at the camera. Ali allowed Foreman to throw many punches but only into his arms and body, and when Foreman tired himself out from the mostly ineffective punches, Ali took control of the fight.

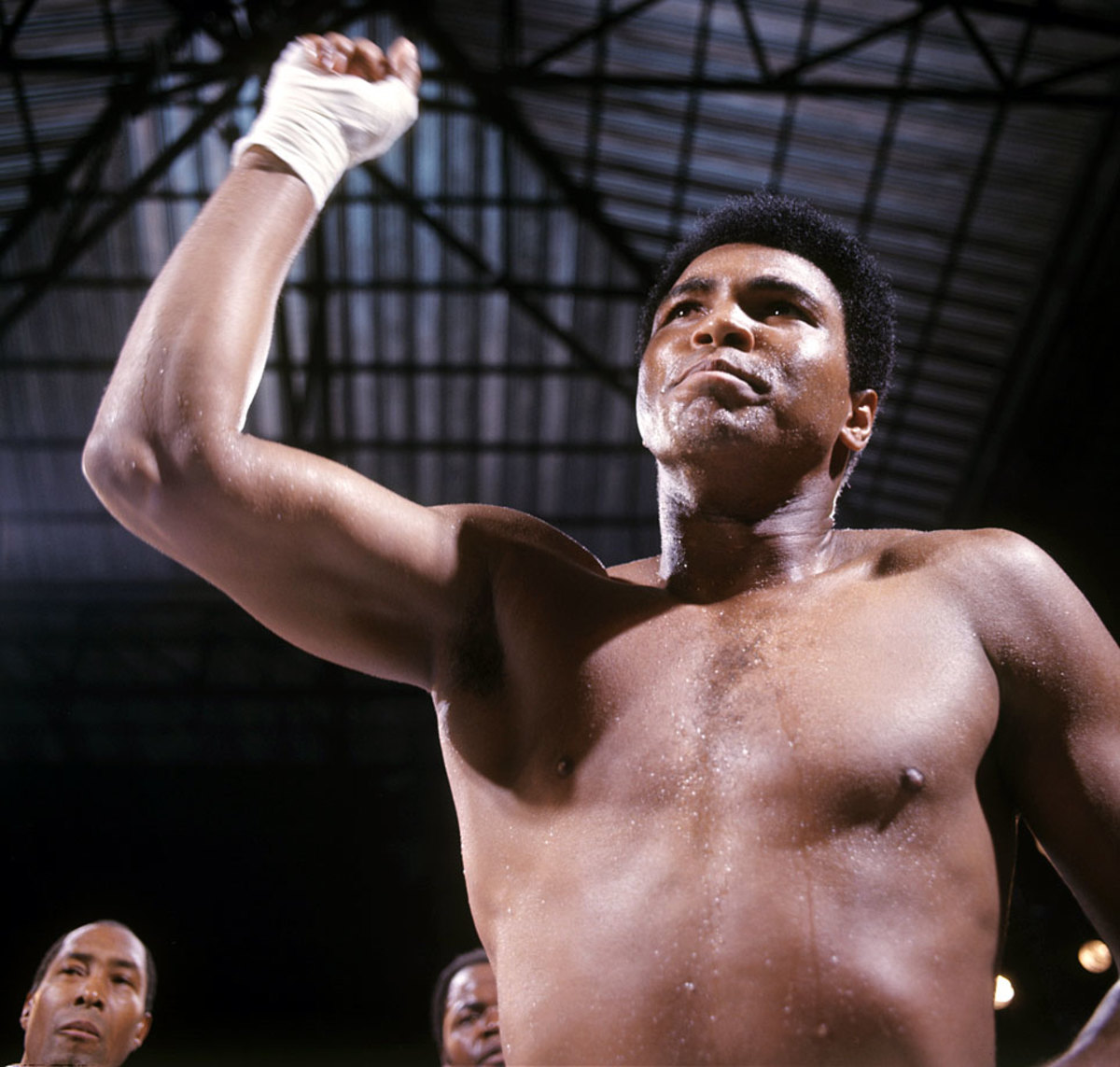

Ali points before his bout with Foreman. The victory over his favored opponent made him the heavyweight champion of the world for the first time since he was stripped of his titles in 1967.

Ali stares at George Foreman during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali earned his shot at the heavyweight title by defeating Joe Frazier in January 1974, avenging a loss three years earlier.

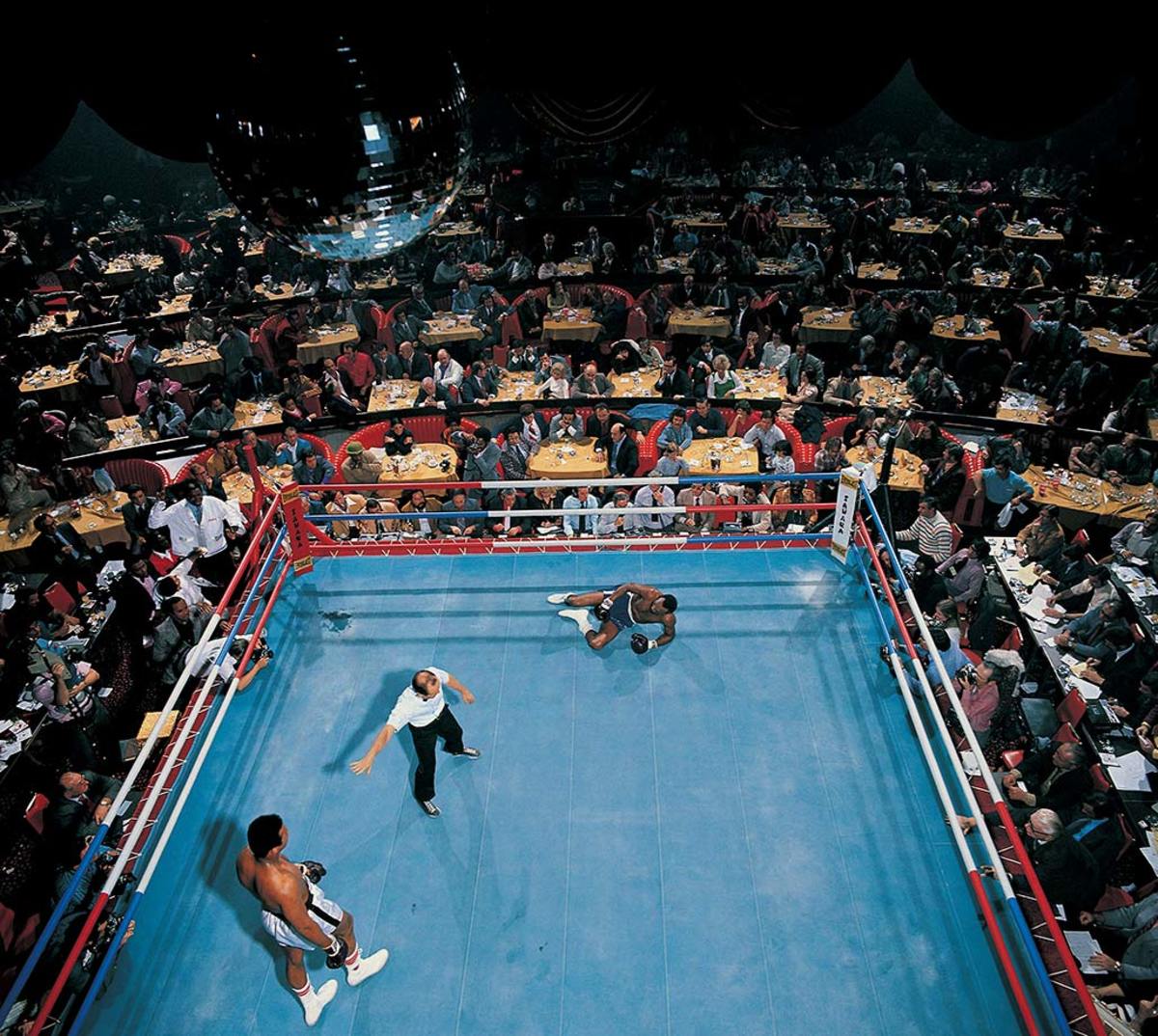

Foreman lies down on the canvas as Ali stands in the background during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali knocked Foreman down with a five-punch combination in the eighth round, and referee Zack Clayton counted him out.

Big George stares at the ceiling as referee Zack Clayton counts him out in the eighth round. The victory made Ali, once again, the heavyweight champion of the world.

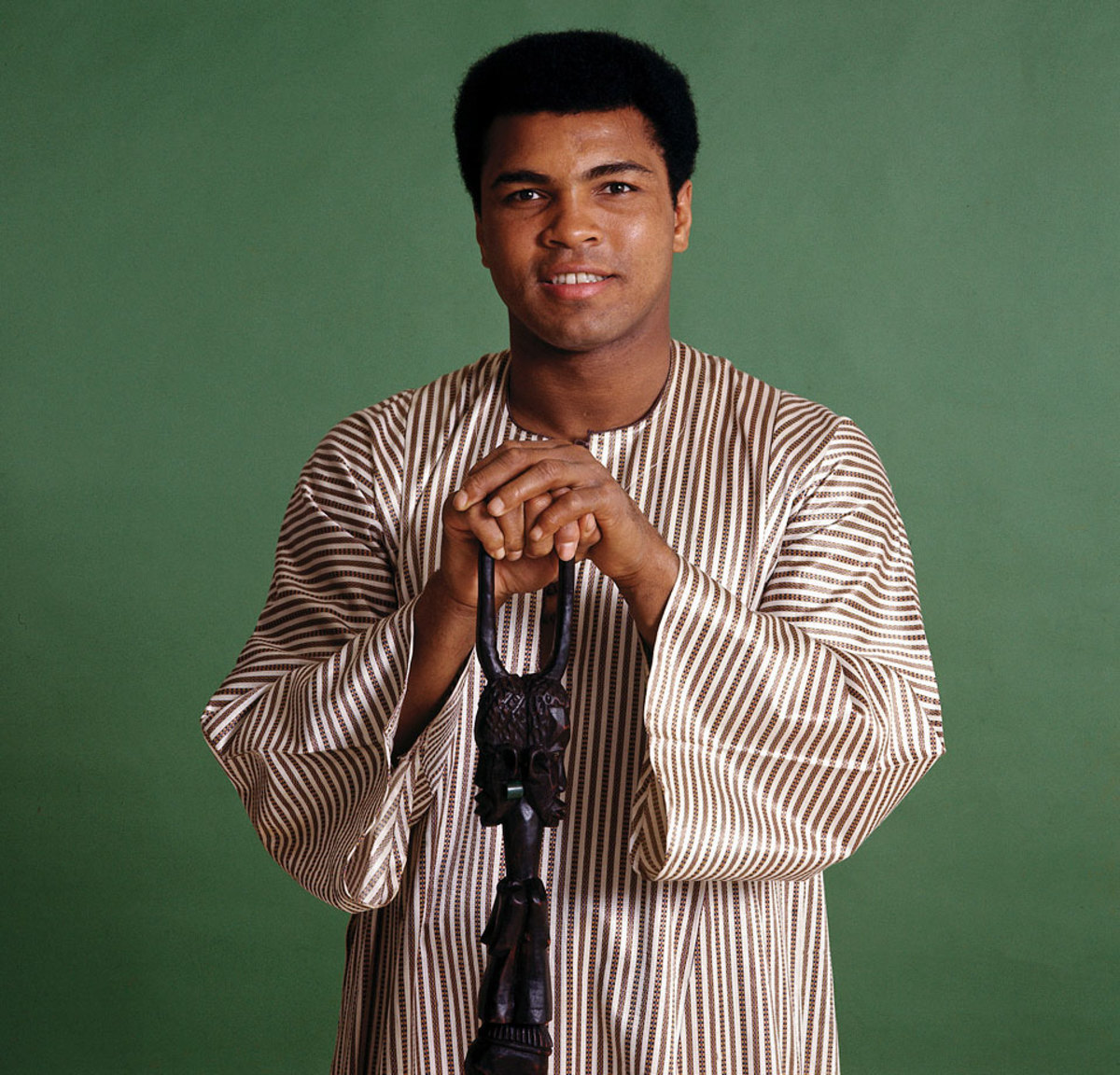

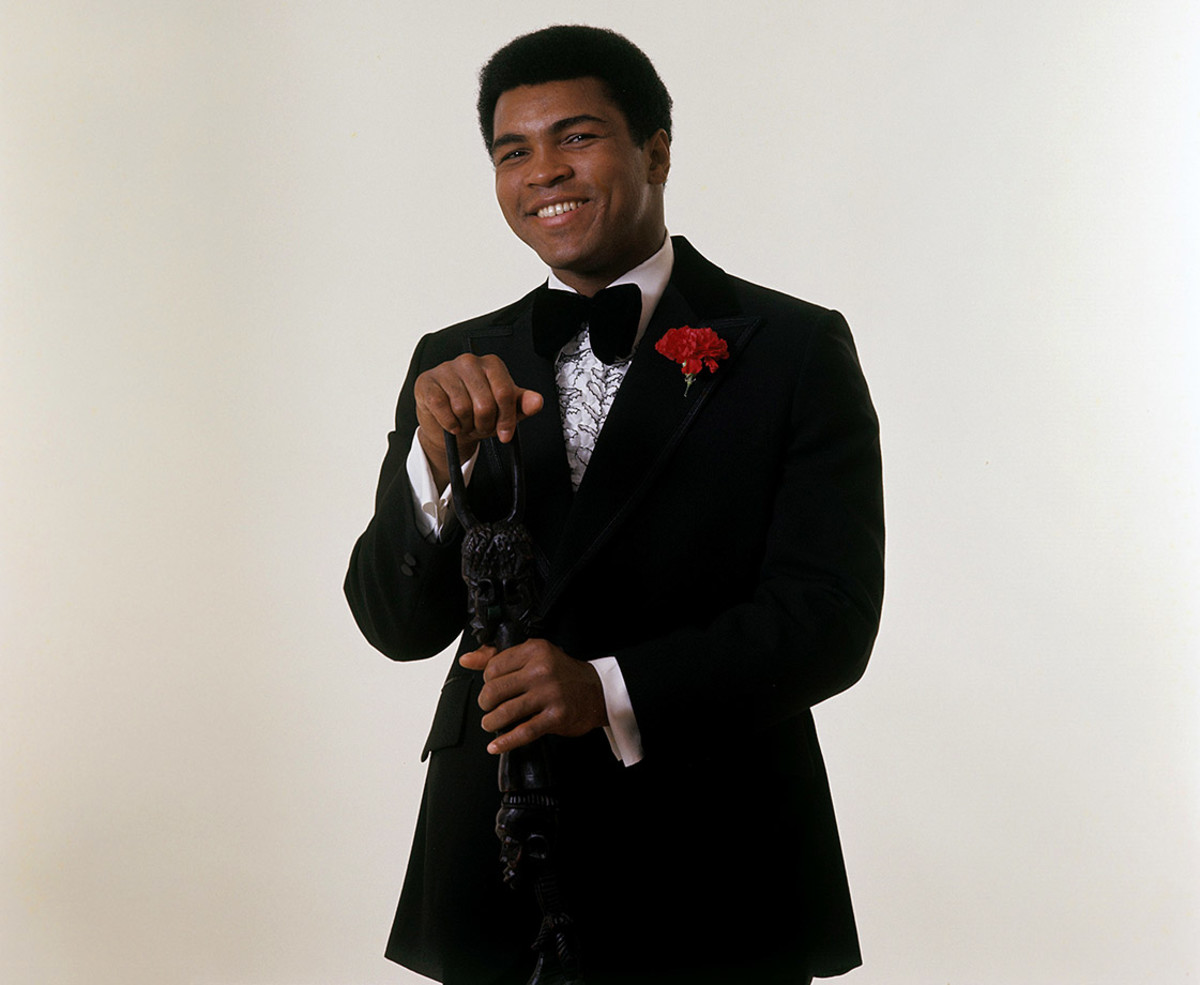

Ali poses for a portrait after being selected as the Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year in 1974. Ali wore a dashiki, a men's garment widely worn in West Africa. He also brought the walking stick given to him by Zaire's president.

This time Ali wears a tuxedo, but keeps the walking stick, during the November photo shoot for Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year.

Ali talks with Howard Cosell outside of the United Nations Headquarters for a segment on the Wide World of Sports. Later that day, Ali held a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

Ali talks with Reverend Jesse Jackson outside of the United Nations Headquarters before a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

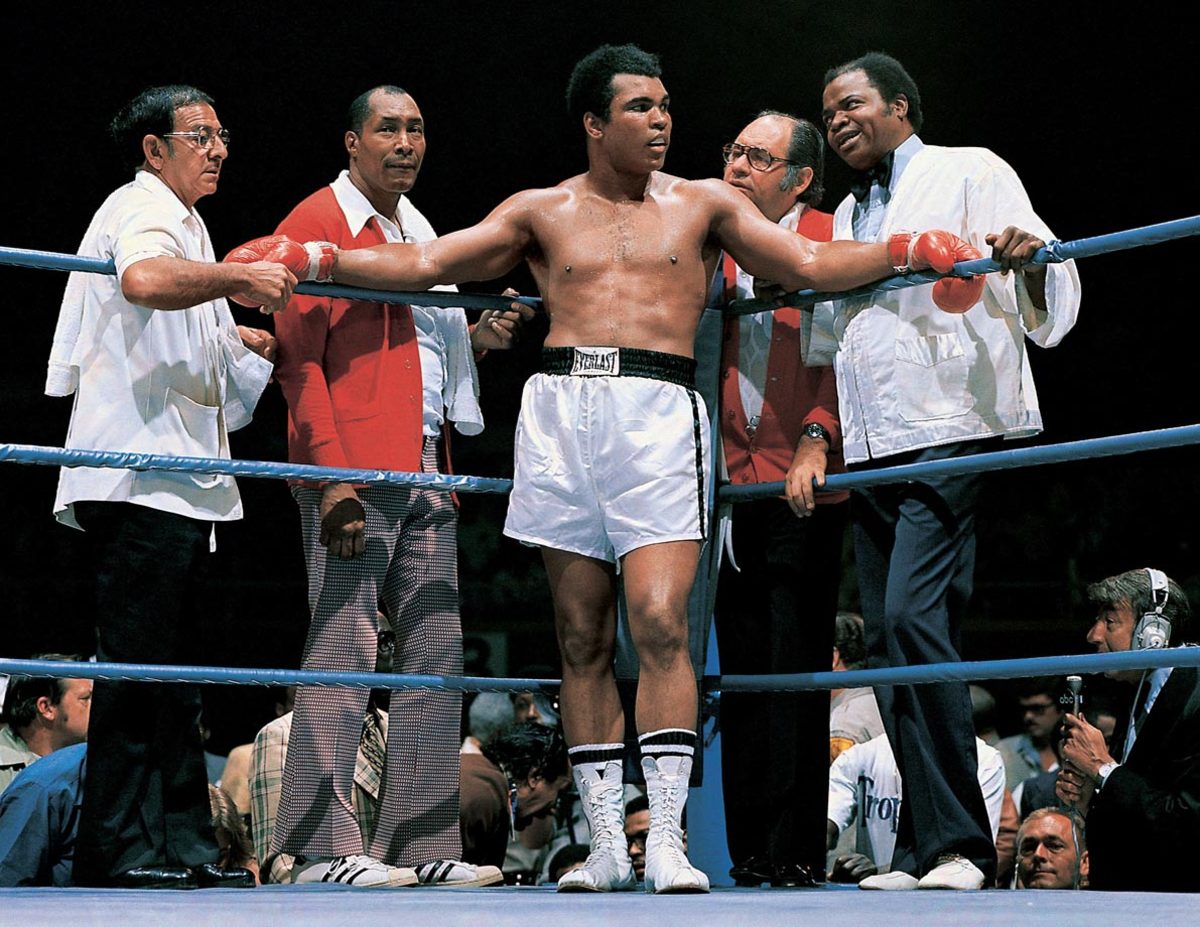

Ali stands with trainer Angelo Dundee, assistant trainer Wali Muhammad, physician Dr. Ferdie Pacheco and assistant trainer Drew Bundini Brown before his bout with Ron Lyle in May 1975. Ali won the fight by technical knockout in the 11th round.

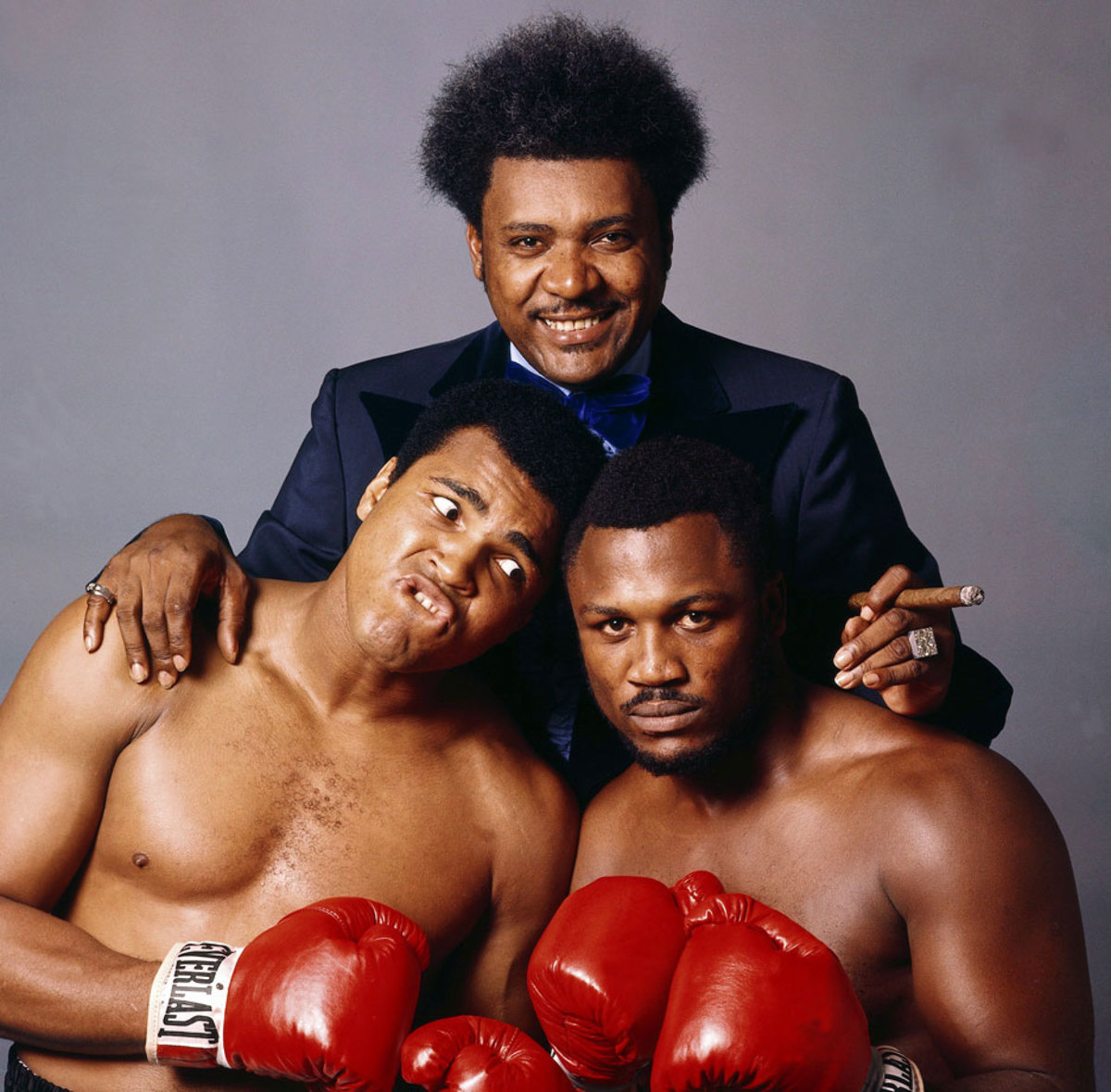

Along with Don King and Joe Frazier, Ali sat for a portrait leading up to the Thrilla in Manila. Ali verbally abused Frazier during the buildup to the fight, telling the media that "it will be a killa and a thrilla and a chilla when I get the gorilla in Manila."

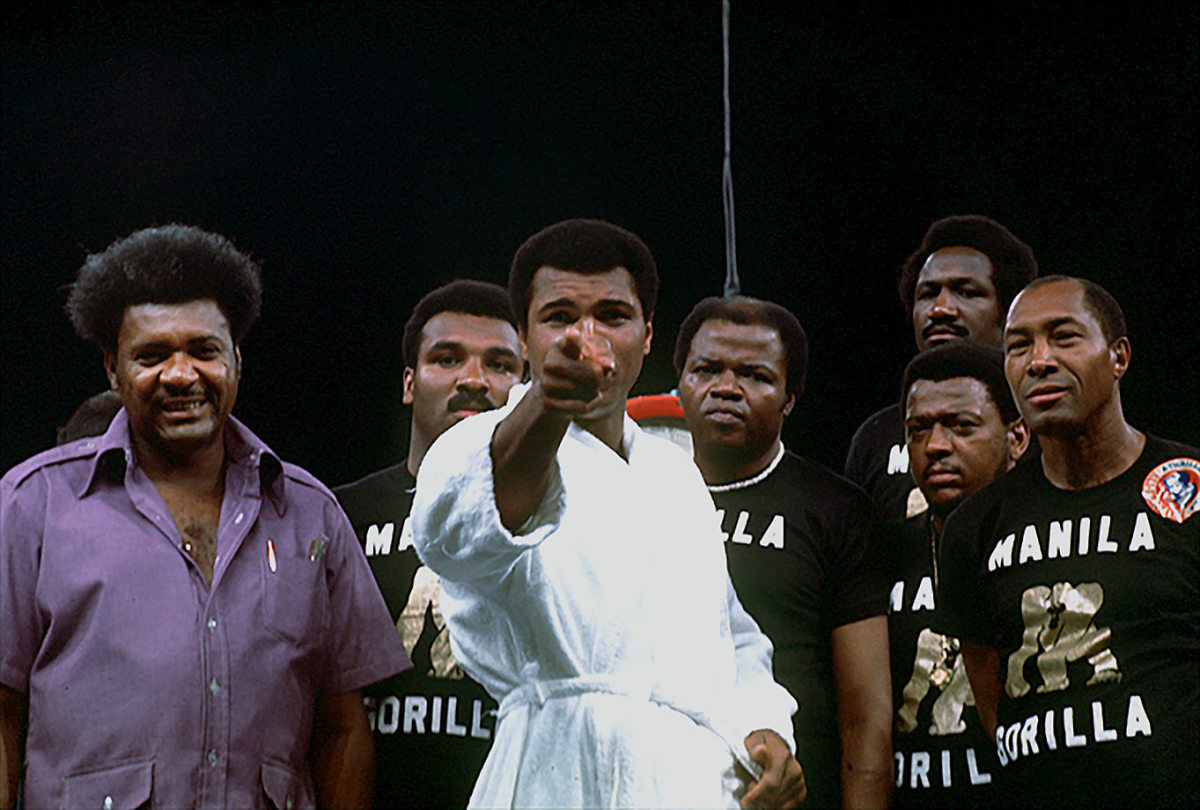

Ali points at the camera with Don King and his training staff behind him before the weigh-in for the Thrilla in Manila in October 1975. Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos offered to sponsor the bout and hold it in Metro Manila to divert attention from the turmoil in the country that had forced the imposition of martial law in 1972.

Wrapping up Joe Frazier proved more difficult than Ali expected, having thought Frazier would represent an easy payday and be unable to live up to his billing. The fight turned out to be a brutal affair.

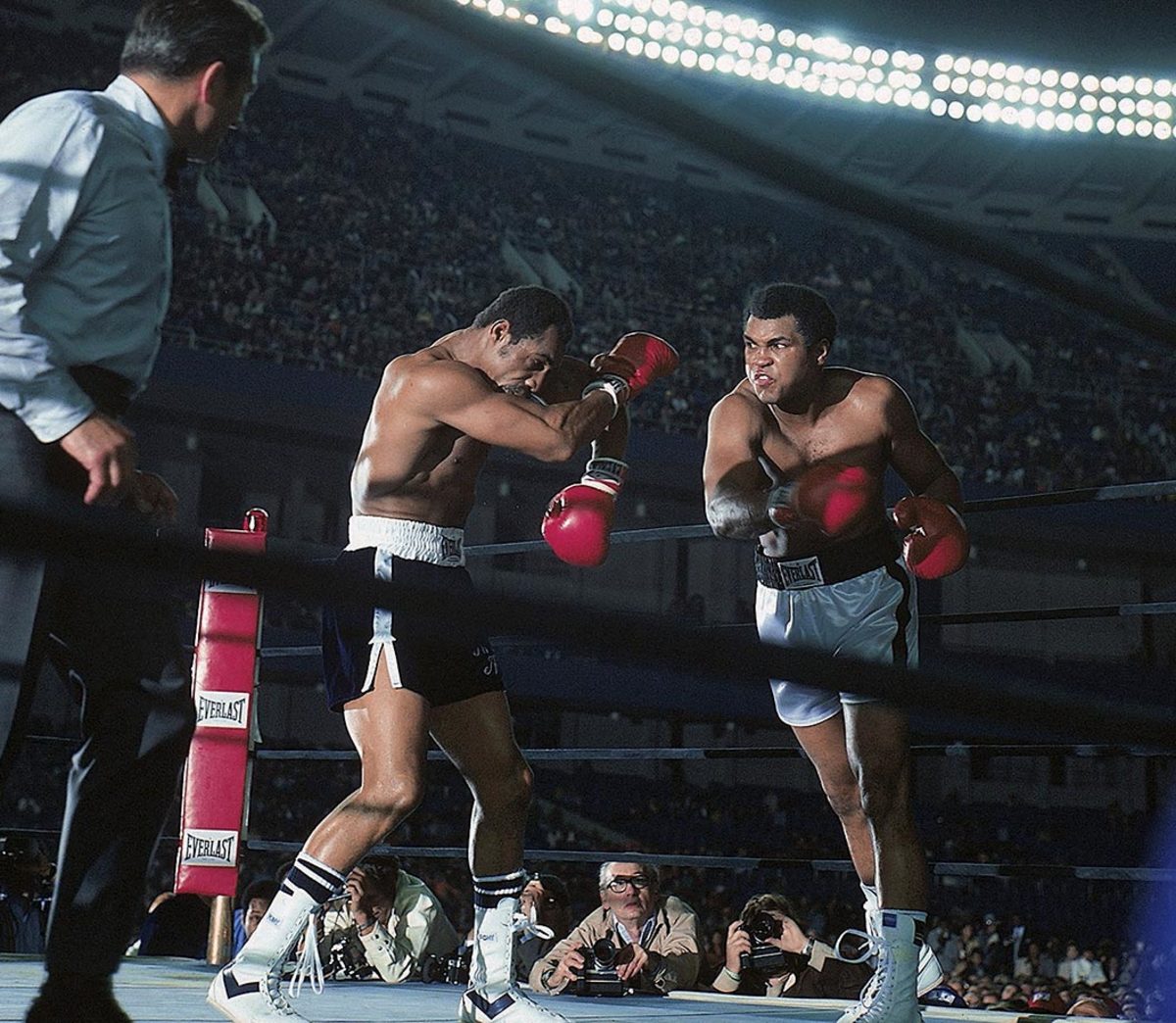

Frazier faces an Ali right hook in their fight in Quezon City, Philippines. The two fighters traded vicious blows during their 14 rounds. "Man, I hit him with punches that'd bring down the walls of a city," Frazier said. Ali withstood the blows to win by TKO in the 15th round.

The third fight between Ali and Frazier, Ali won the bruising battle between the two powerful punching heavyweights when Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, stopped the fight before the 15th round.

A back and forth exchange, Ali controlled the early rounds of the Thrilla in Manila before Frazier fought back with powerful hooks. Ali finished strong, regaining momentum in the later rounds.

Ali speaks to the press after winning the Thrilla in Manila bout with Frazier.

Ali holds a drinking concoction given to him by Dick Gregory, an advocate of a raw fruit and vegetable diet, in 1976.

Before his 1976 fight against Ken Norton at Yankee Stadium, Ali watches a fight on television from his hotel room. A police strike at the time of the fight created a dangerous environment outside the stadium that all but eliminated walk-up sales.

Norton takes a right hook during the heavyweight title fight against Ali. The bout, which Ali won by a unanimous, but controversial, decision, was the last boxing match at Yankee Stadium until 2010.

Ali makes a face during his fight with Earnie Shavers in 1977 at Madison Square Garden. Hurt badly by Shavers in the second round, Ali rebounded and outboxed Shavers throughout to build a lead on points before Shavers came on again in the later rounds. Seemingly exhausted going into the 15th and final round, Ali remained victorious by producing a closing flurry that left Shavers wobbling at the bell and the Garden crowd once again in delirium over his Ali magic.

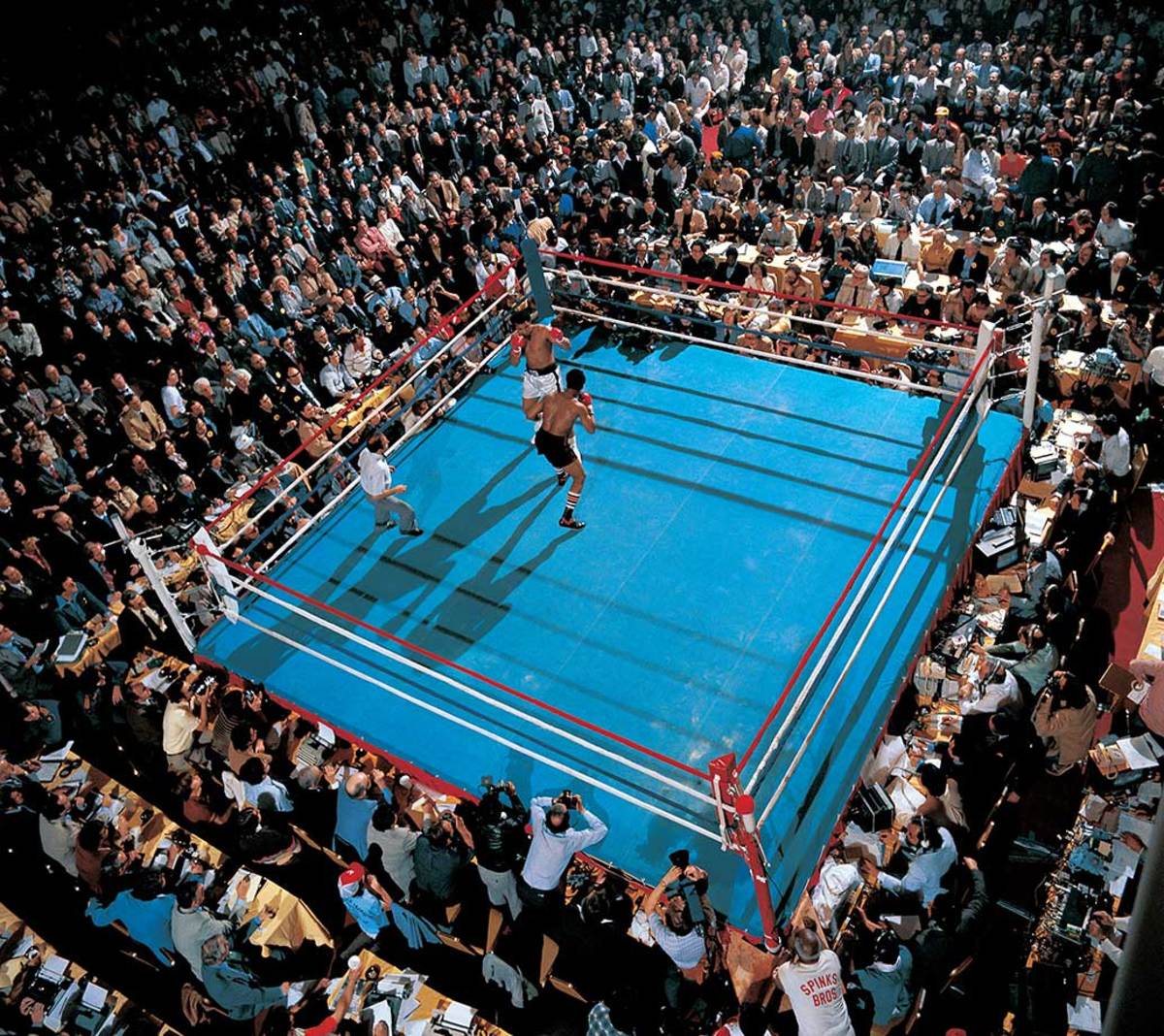

Ali squares off with Leon Spinks at the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel in February 1978. Spinks won the fight in a split decision, ending Ali's 3.5-year reign as the heavyweight champion. It was the only time in Ali's career that he lost his championship title in the ring.

Leon Spinks took center stage over Ali at the press conference after their fight. The victorious Spinks and his gap-toothed grin were featured on the Feb. 19, 1978 cover of Sports Illustrated.

Ali lands a straight right hand to the head of Spinks in the rematch of their title bout in 1978. Ali won on a 15 round decision.

Don King pulled the strings again when Ali faced Larry Holmes before their November 1980 fight. King became a key figure in Ali's career, promoting his biggest fights, the Thrilla in Manila and the Rumble in the Jungle.

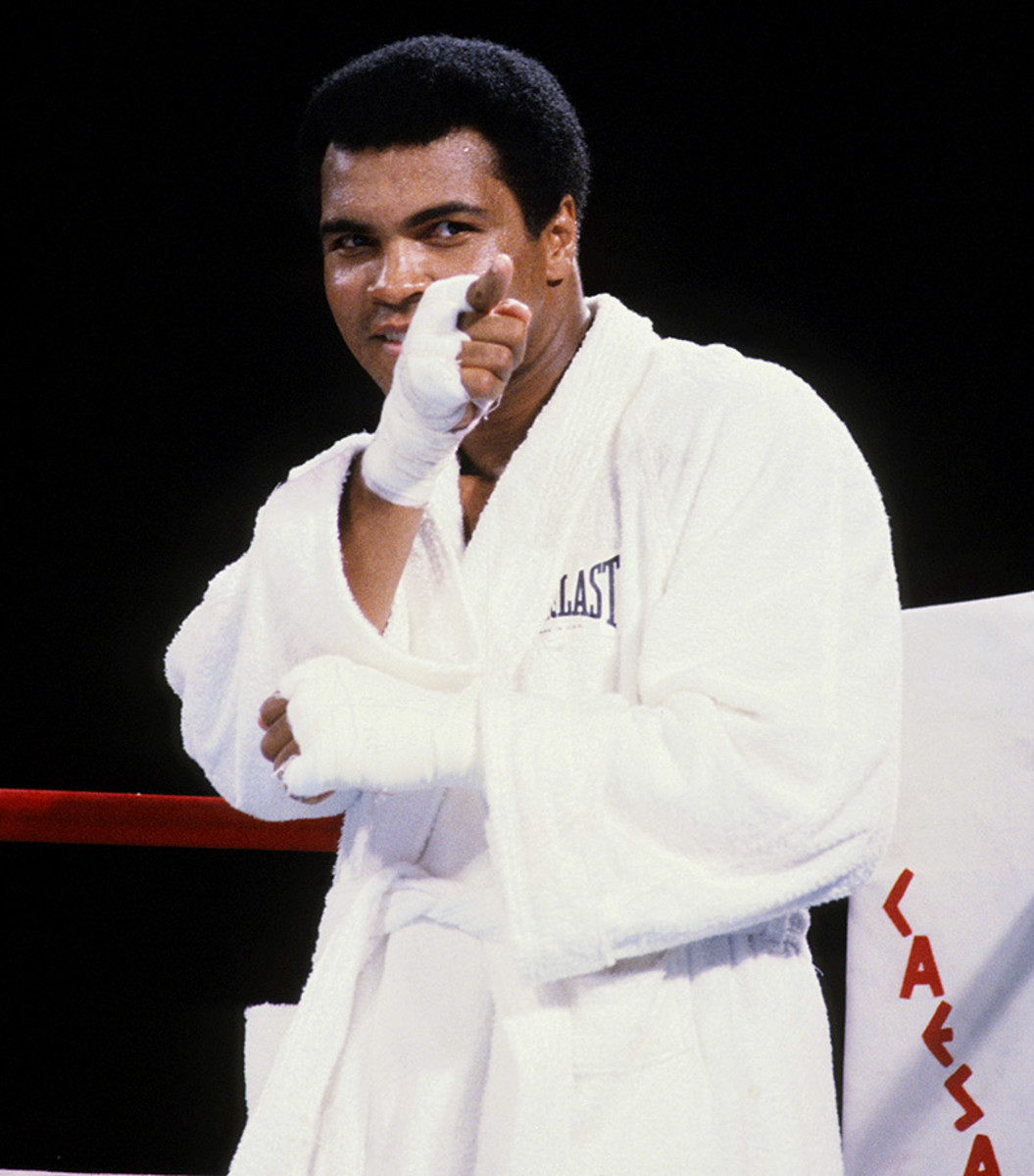

Ali points at Larry Holmes before their bout at Caesars Palace in 1980.

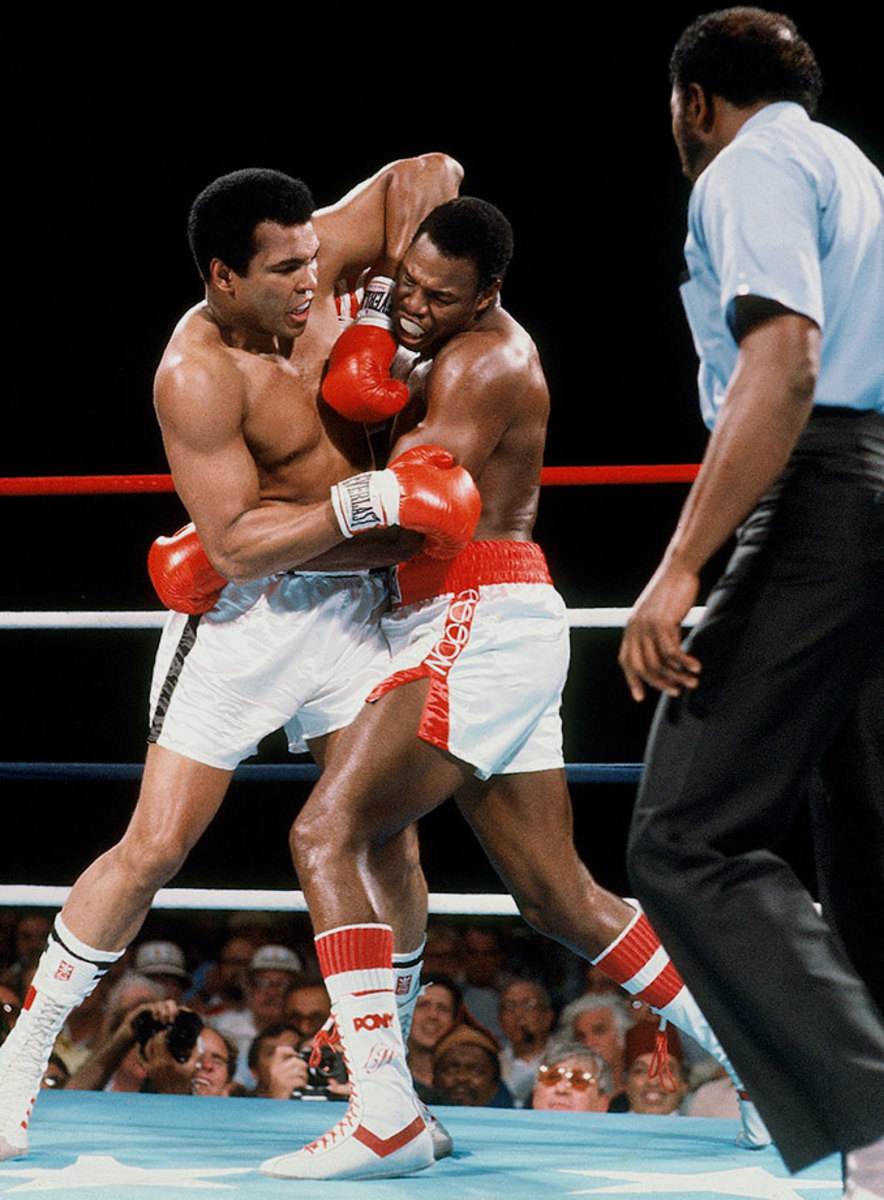

Ali grapples with Holmes during their bout in 1980. Trainer Angelo Dundee stopped the fight in the 11th round, marking the fight as Ali's only career loss by knockout.

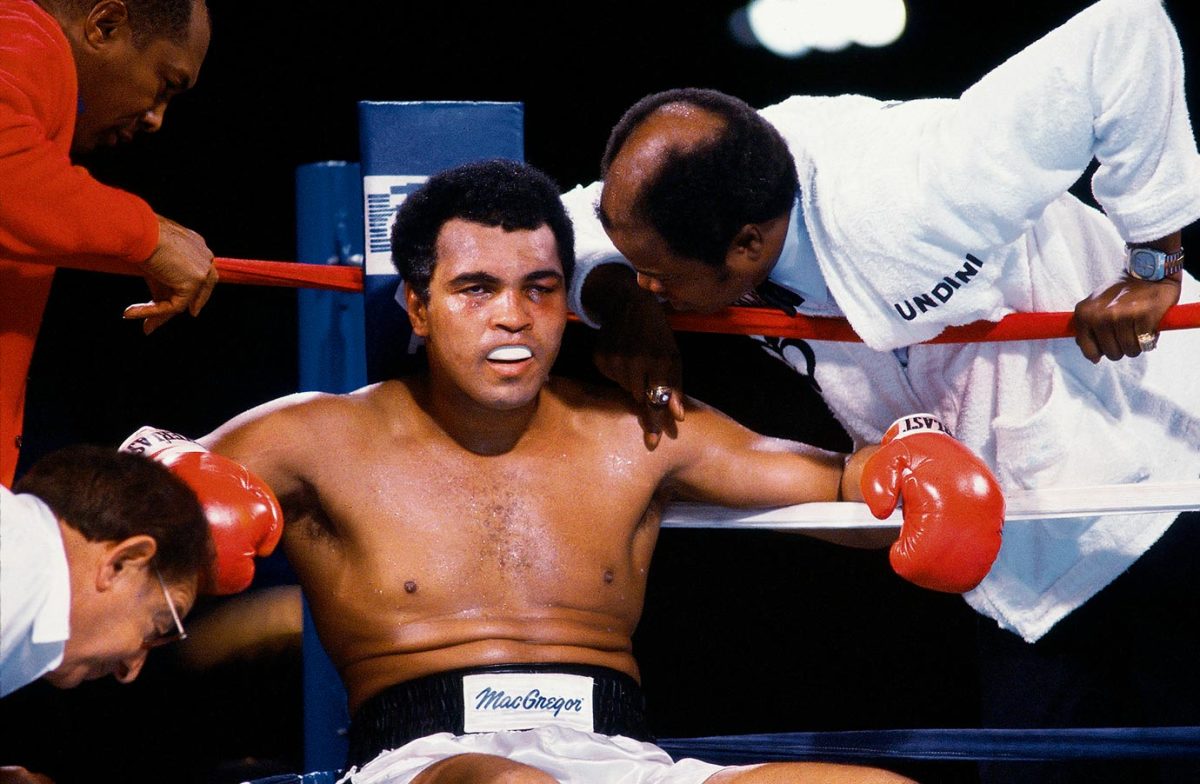

Drew Bundini Brown leans in to speak to Ali, who returned to fight Holmes after a brief retirement. By this time, Ali had already begun developing a vocal stutter and trembling hands and taken thyroid medication to lose weight that left him tired and short of breath.

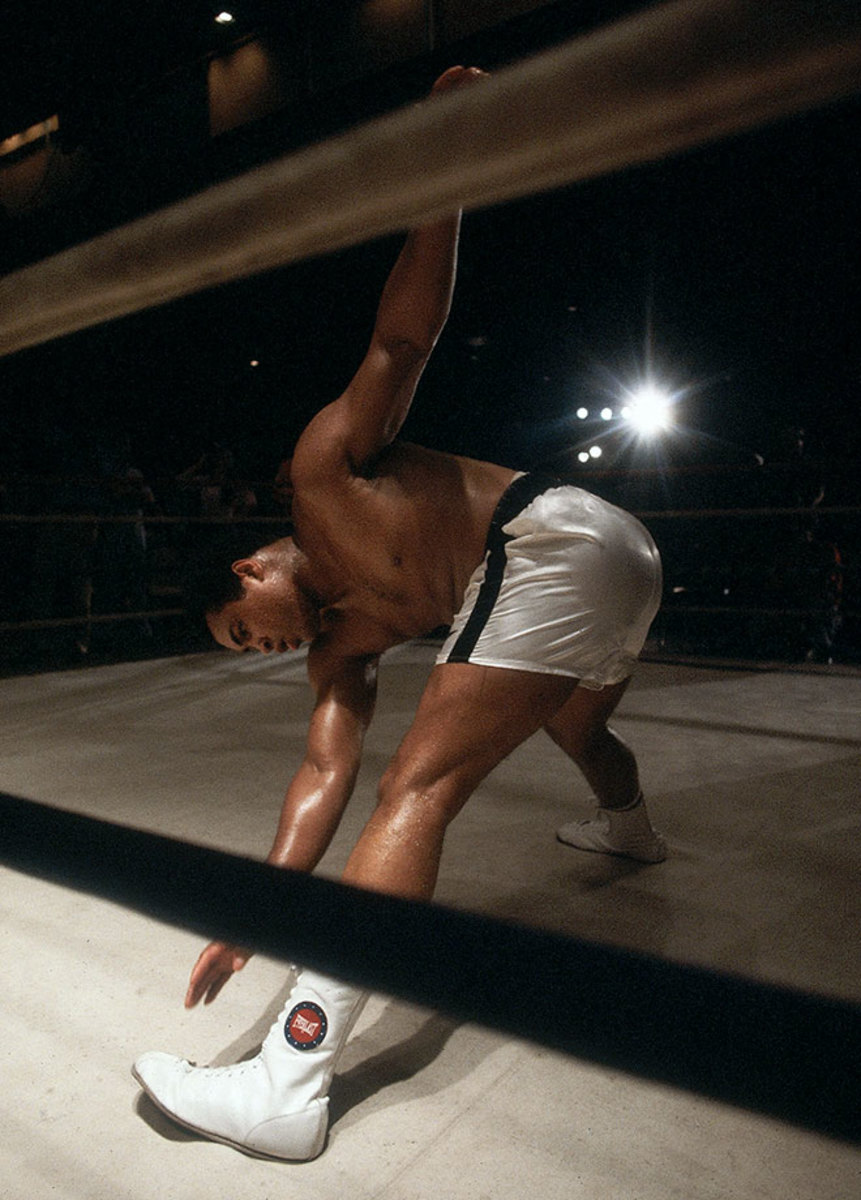

Ignoring pleas for his retirement, Ali stretches before a fight against Trevor Berbick in Nassau, Bahamas. Ali lost to Berbick in a unanimous decision and retired after the bout, the 61st of his career.

Ali pretends to spar with artist LeRoy Neiman at his home in Los Angeles. Neiman met Ali in 1962 and made many paintings and sketches from throughout Ali's life.

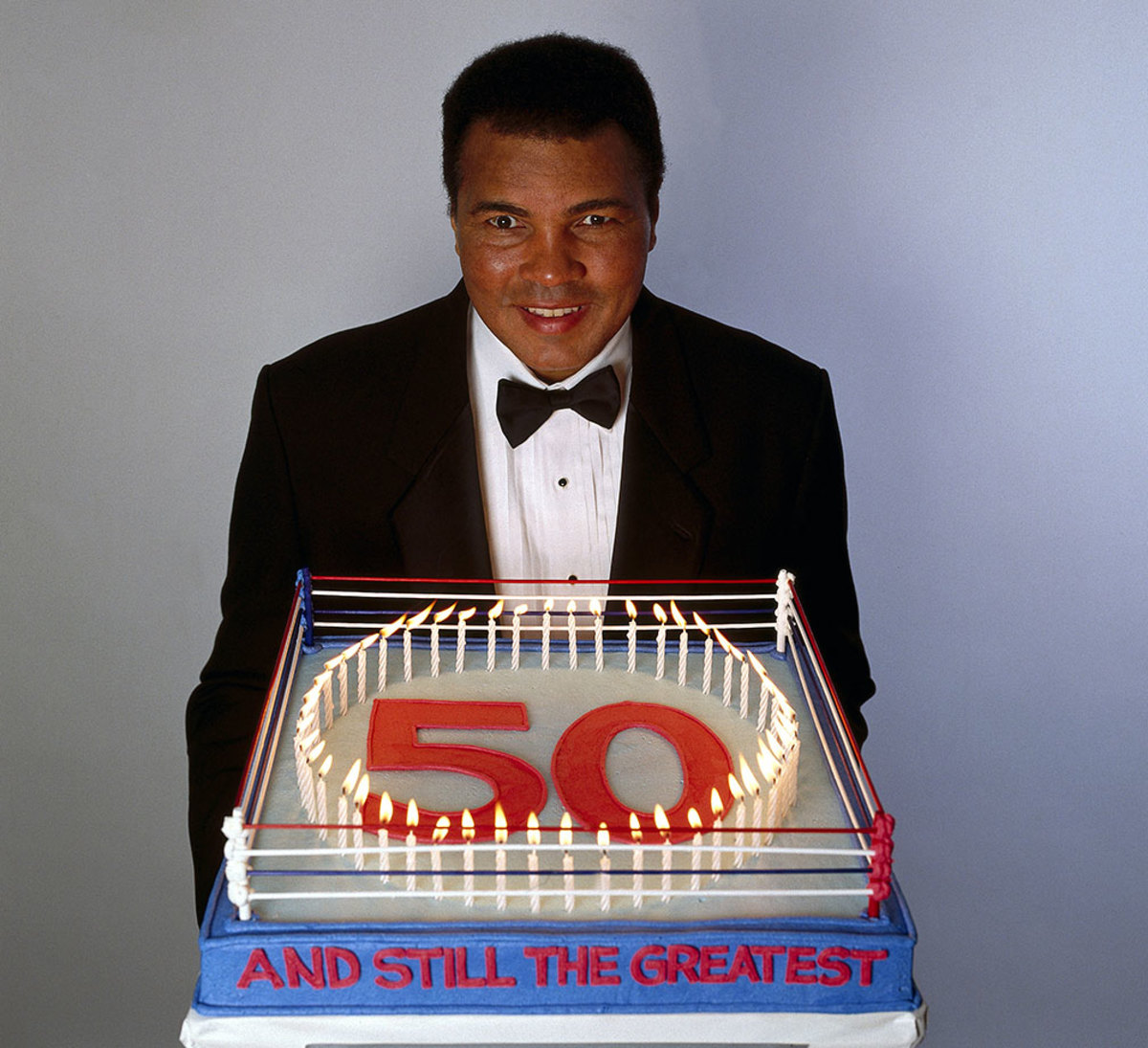

Cake in hand, Ali poses for a 50th birthday portrait in 1991. Although diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome seven years earlier, Ali was still active, traveling to Iraq during the Gulf War to meet with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages.

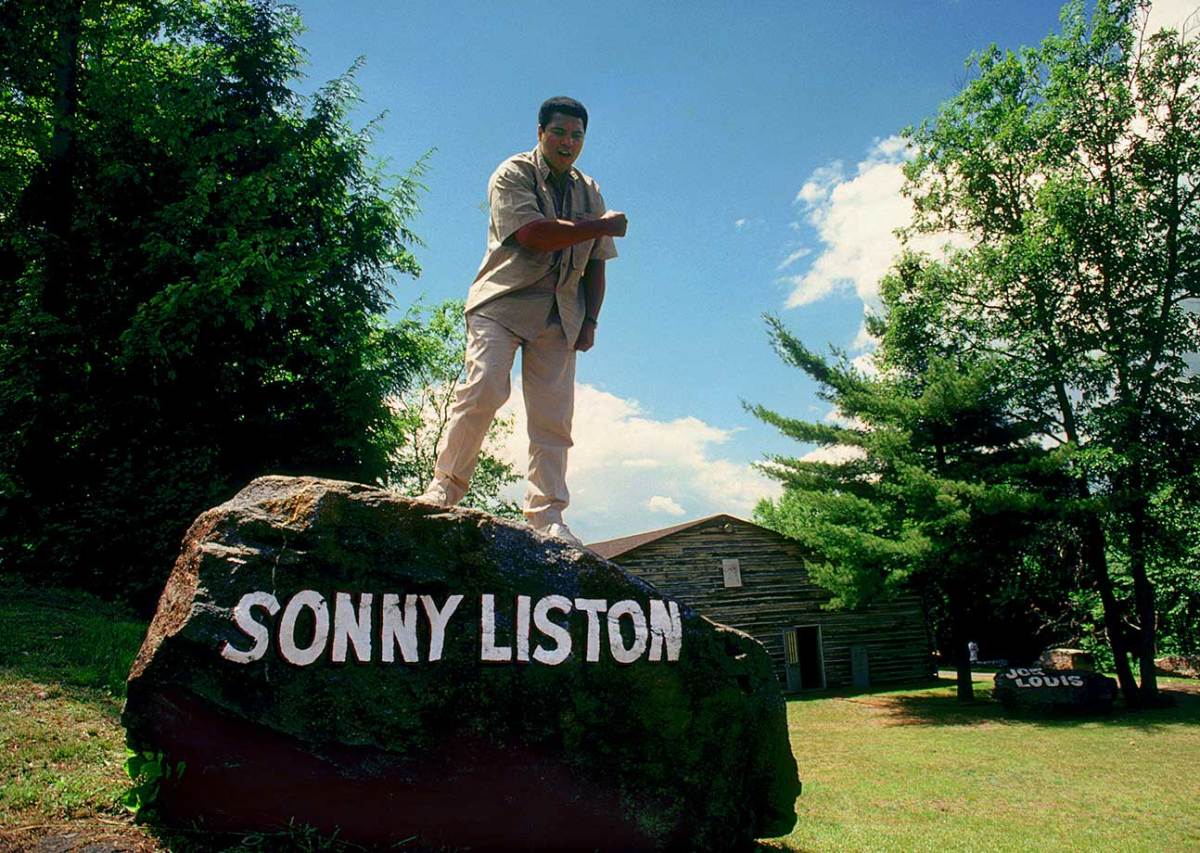

The same year, Ali stands atop of the Sonny Liston rock at his old training camp cabin. Ali and his father painted the names of famous boxers he admired on 18 boulders at the camp.

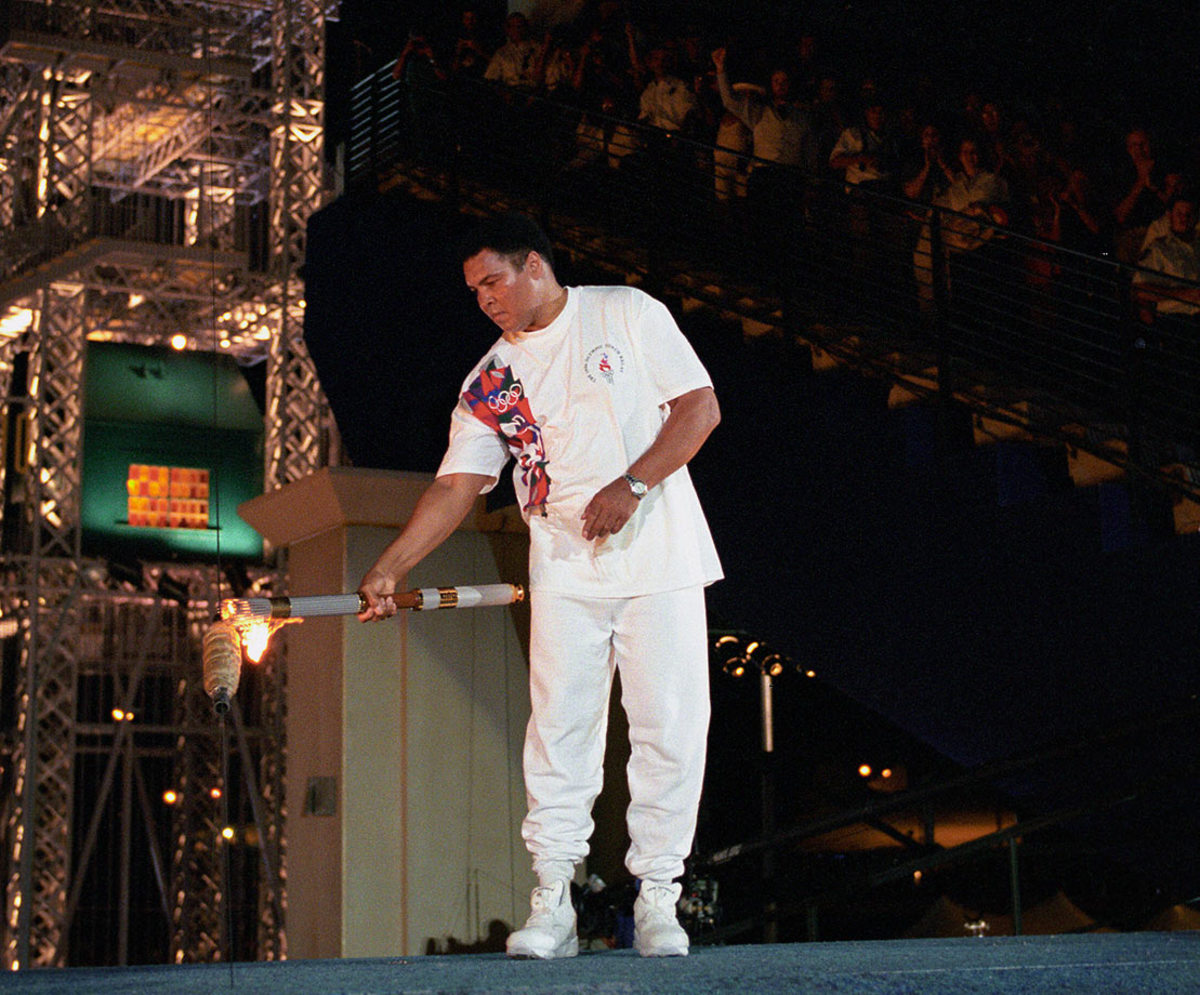

Ali carries the Olympic torch inside Centennial Olympic Stadium at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Despite trembling hands, Ali had the honor to light the Olympic flame in the stadium.

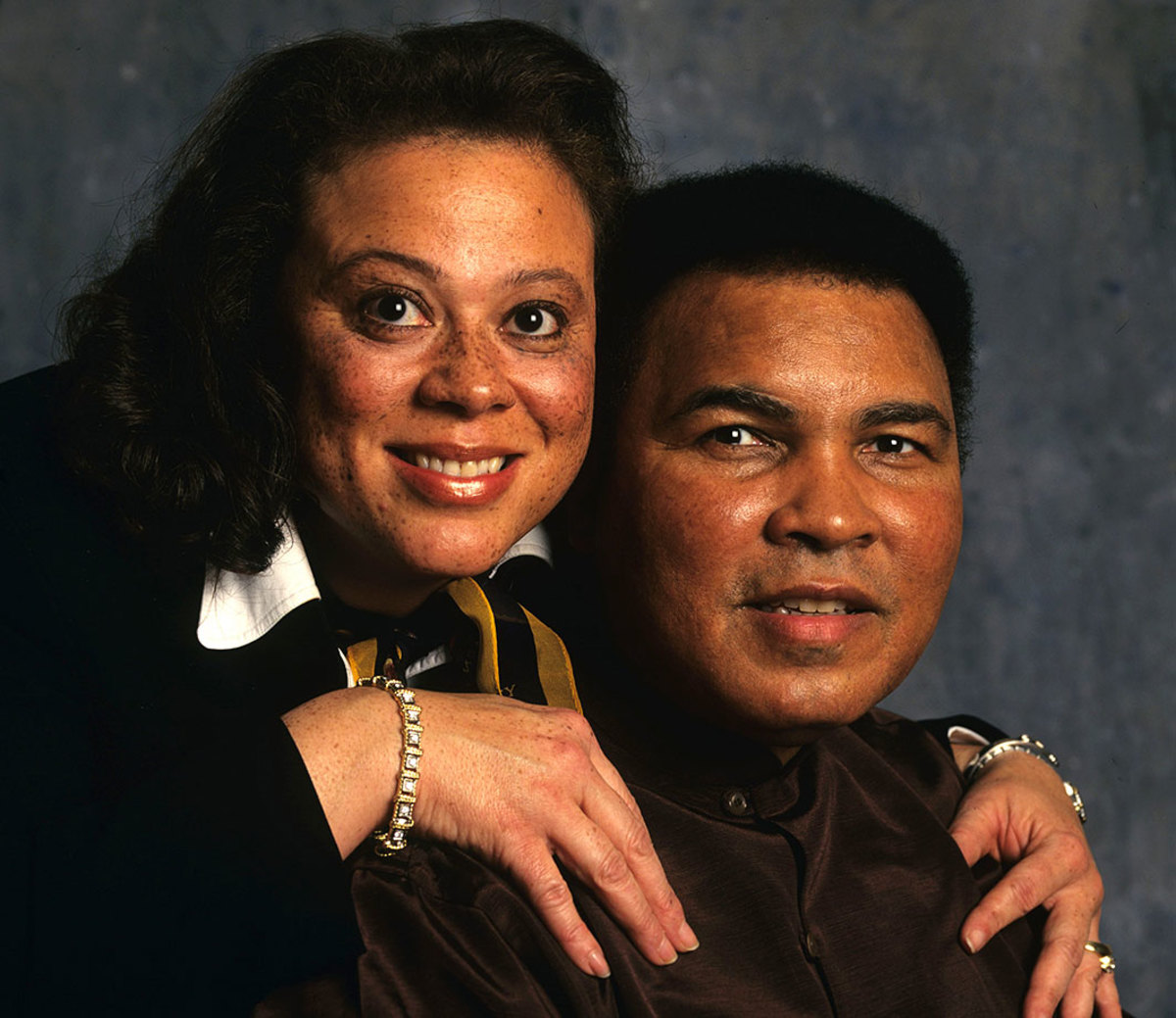

Husband and wife pose for a portrait during a photo shoot in 1997. Muhammad and Lonnie married in 1986 and have an adopted son together, Asaad Amin Ali.

Ali messes around with actor Billy Crystal during a photo shoot in 2000. Crystal's impression of Ali was notorious, and he performed at a tribute to the boxer on his 50th birthday in December 1991.

Ali lies on the canvas as his son, Assad Amin Ali, stands over him invoking memories of Ali's victory over Sonny Liston during a photo shoot in the gym at his farm on Kephart Road near Berrien Springs in 2001.

Fierce rivals in the ring, Ali and Joe Frazier pose for a portrait in the boxing robes they wore the night of their first bout at Frazier's Gym in 2003. Ali said after Frazier's death in 2011 that he was "a great champion."

Ali takes a punch from his daughter Laila Ali while sparring before her fight against Erin Toughill in 2005. Laila retired from her own successful boxing career with a professional record of 24-0.

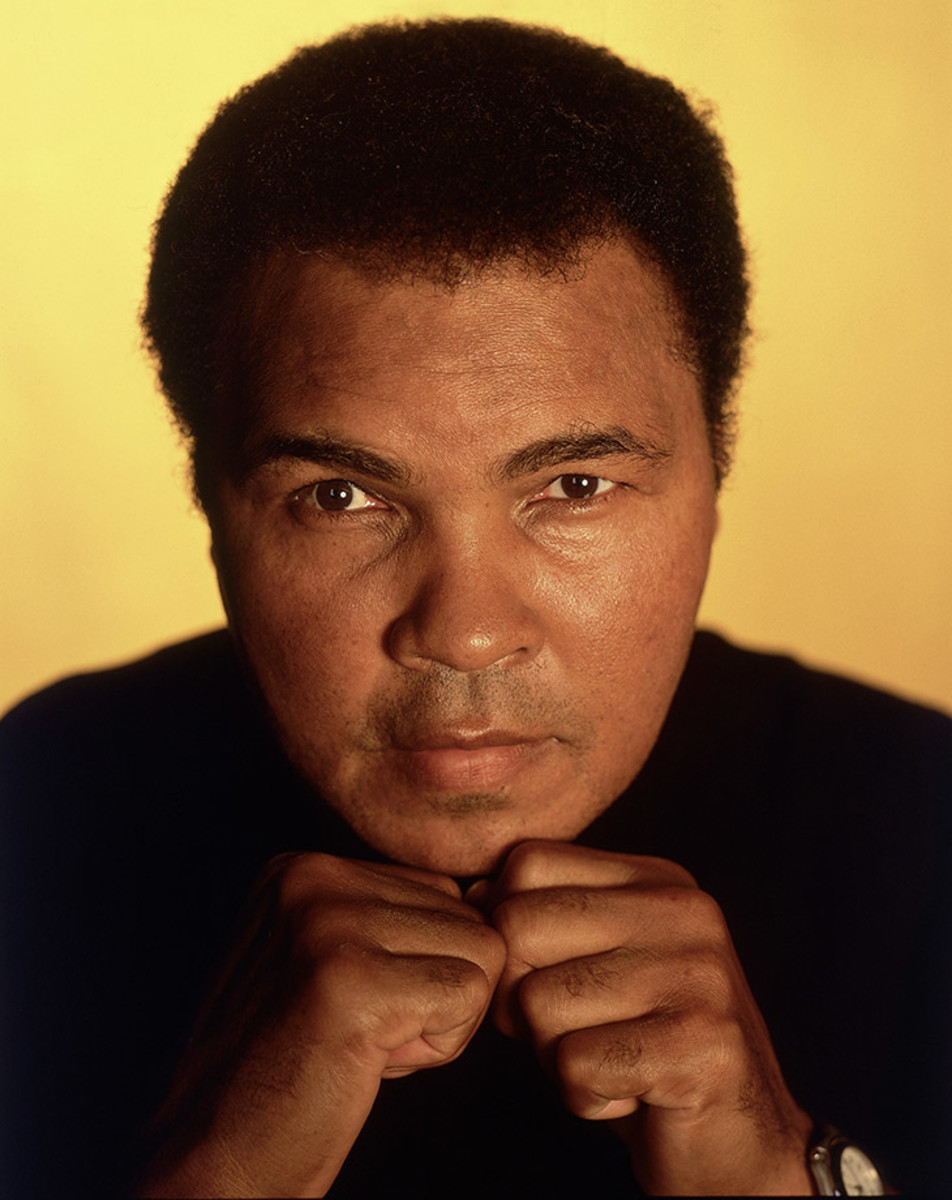

Ali poses with his fists up for a portrait in 2005.

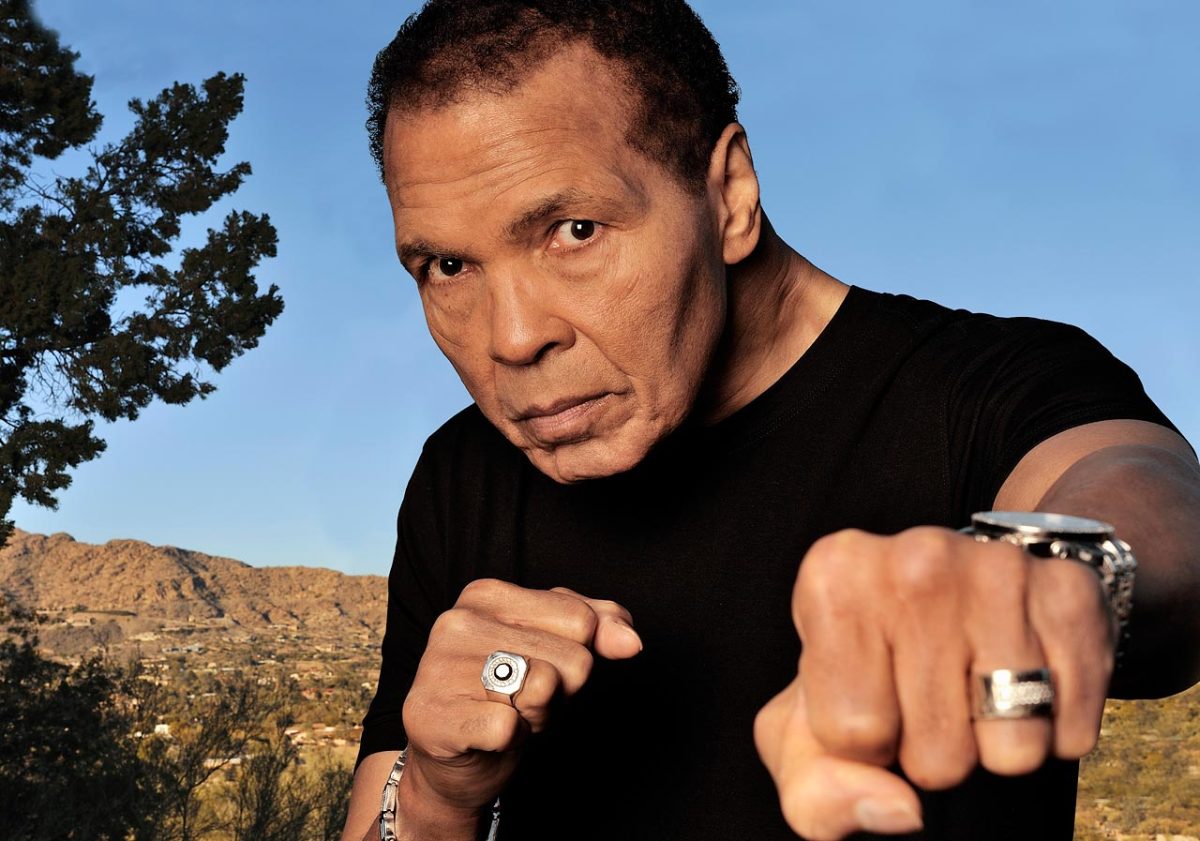

Ali poses with an extended punch in a 2012 photo shoot at his home in Paradise Valley, Ariz., to mark his 70th birthday.

Ali sits in front of a 70th birthday cake in January 2012 at his Arizona home. Later that year he appeared at the opening ceremonies for the 2012 Olympics in London to escort the Olympic flag into the stadium, 52 years after he won gold in Rome.