Cassius to win a thriller

This story originally appeared in the May 24, 1965 issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

Some time after the eighth round on the night of May 25, in the small and unlikely town of Lewiston, Me., Cassius Marcellus Clay (who would much rather be called Muhammad Ali) will certify his claim to the heavyweight championship of the world by knocking out challenger Sonny Liston.

This, of course, is an opinion—and there are other opinions which hold that neither man should be in that ring at all, Clay because of his allegiance to the Black Muslim organization and Liston because of his alleged underworld connections. But no amount of opinion can alter the fact that these two men are the best heavyweights in the world. A year ago in Miami Beach they produced a turbulent and exciting fight, and now another one is in prospect.

Although he is likely to end up a battered and well-beaten fighter, Liston will not quit in his corner this time. But, unfortunately for him, the Clay he meets in Lewiston is a surer, more mature and more expert fighter than the Clay who beat him in Miami Beach; Liston himself is a year older, a trifle slower and, although he has whipped himself into exceptional condition, a bit less certain of his abilities.

"I made a mistake in Miami I ain't going to make again," he said the other day in his training camp. "I got new plans for this fight, but I ain't saying what they are. But I ain't making the same mistake."

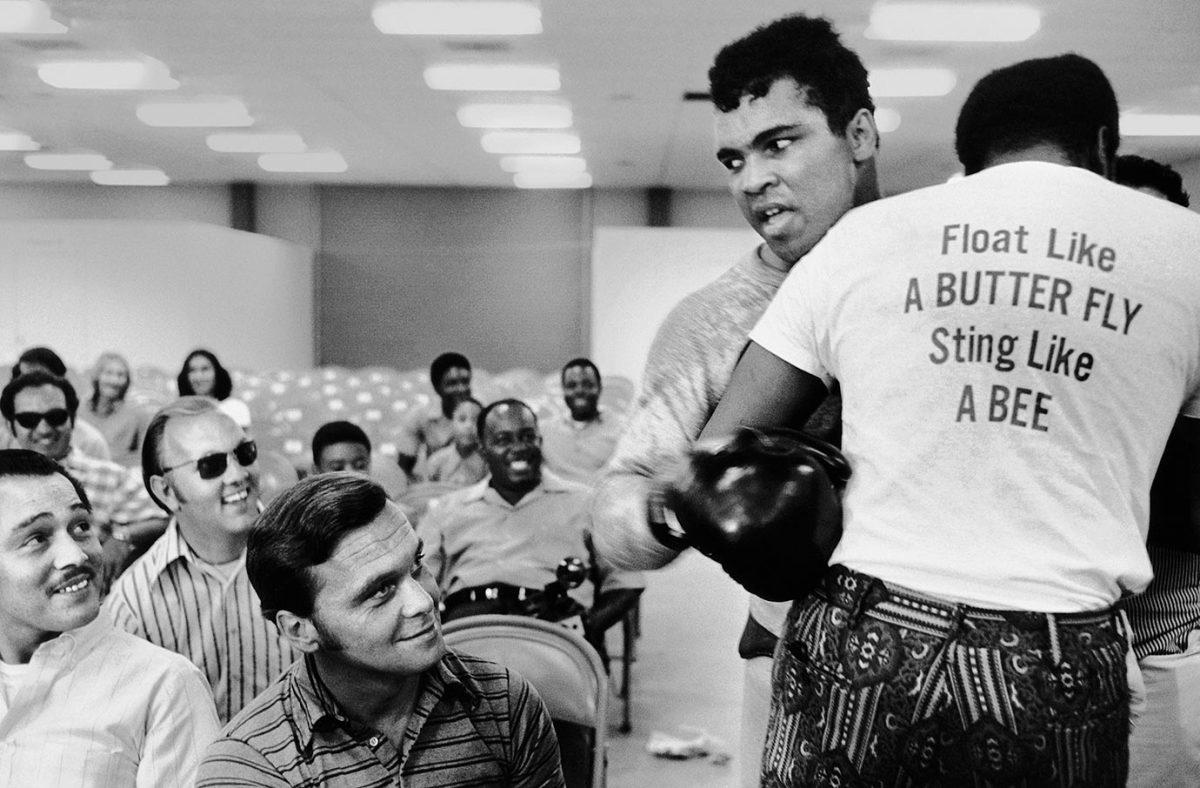

In his workouts for the fight, the new plans seemed obvious. In Miami he came after Clay hell for leather in the first round, a tactic made to order for a man with Clay's speed and ability to float like a butterfly. Against his sparring partners this time Liston has moved deliberately, stalking them and waiting for a chance to deliver his best punch—the left hook with which he twice demolished Floyd Patterson. In Willie Richardson and Amos (Big Train) Lincoln he has sparring partners who are far superior to the nondescript crew he worked against in Miami Beach. Both men are quick, and Lincoln is as tall as Clay; they have forced Liston to work hard and often they have made him look clumsy, but he has caught both of them time and again with that vicious, short-arc left hook.

Once Richardson, in a poor imitation of Clay's hands-down style, bounced off the ropes directly into the left hook and dropped as if shot. Richardson is the only sparring partner in either camp who has sparred with both Clay and Liston. After he had been revived he said, "The man here hurt you whenever he hit. And Clay can be hit. You can't go after him swinging all the time, because that what he like. He move around, dance in, hit you pop, pop, pop, dance out, make you miss, hit you pop, pop, pop again and it begin to hurt bad after a while. But I used to wait and wait and look for my shot, and I hit him pretty good. That was three years ago, and they kept me around only four days because I wasn't doing the way they want me to do."

He felt his face gingerly.

"This man can whip Clay," he said, "if he can hit him."

That, of course, is Liston's problem, and it seems doubtful that he will solve it. He has worked earnestly at developing a right-hand punch to the body, but when he throws it it is ponderous. Liston is left flat-footed and spraddle-legged, and this is one of the things Clay counts on.

The other morning, hacking ineptly at a tree in the woods near his training camp in Chicopee Falls, Mass., Clay expounded his fight philosophy.

"I don't usually tell people this, because they don't understand," he said. "I don't really have no fight plan. Angelo [Dundee], he got a fight plan, and I do it when I can. But it would be the worst thing I could do to go in therewith my mind all made up what to do. I been fighting since I was a child, and I do everything on instinct. Sometimes I wonder at myself when I see a big fist coming at my head, and my head move without me thinking and the big fist go by. I wonder how I did it."

He swung his ax awkwardly at the tree, and did small damage.

"One thing gonna be very different this time," he said. "Now, last time I was ducking just to not get hit. Ducking to get away. This time, every move I make, it gonna be to set him up."

Clay's manager, Angelo Dundee, and his other advisers have studied movies of Liston very carefully and discovered some flaws that they feel may be fatal to him.

For instance, when Liston is hit with a jab, his first reaction is to drop both hands to chest level. Then he feints twice with his left before throwing a punch, a tactic known as the Philadelphia feint because Philadelphia-trained fighters are apt to use it.

Clay's riposte to this is a fairly obvious one. When he hits Liston with a jab—which he did often in the first fight—he will follow immediately with a right, hoping to catch Liston with his hands down.

The swinging right hand to the side of the body, which Liston has worked on so assiduously, is no secret to Clay or Dundee. Working with his sparring partners, Clay has learned to counter this move by stepping back quickly to let the punch go by, then moving in with a short, hard right uppercut, a punch he developed before the first Liston fight and one he has since improved.

Clay's personality has changed in the last year. He seems more sober now and less flamboyant. "The boy is gone," says Drew (Bundini) Brown (SI, May 17). Bundini is probably Clay's best friend. "What you see now is the man. And what I got to worry about now is that the man don't go trying too hard to prove that he is a man. The man apt to take too many chances trying to prove that, and he can't afford no chance-taking."

Aside from taking foolish chances—and Clay certainly did not do that in the first fight and most likely will not in this one—the one thing Clay must avoid at all costs is being trapped in a corner where Liston can maul him. He has the speed afoot to stay away from Liston, circling away from Sonny's left hand, and he has worked steadily on this. In training, he occasionally let himself be crowded into the ropes by a sparring partner, and protected himself by bobbing and weaving; a similar move against Liston could lead to disaster.

Clay will be more aggressive in this fight than he was in the last. In the third round in Miami he hit Liston with a lovely combination of punches, knocking him back into the ropes and cutting his eye. Liston was still dangerous then; Clay, instead of moving in and following up his advantage, stayed away and gave Sonny a chance to recuperate.

"We get the same chance in this fight, we move in," Dundee says, in anticipation. "I think if Clay had moved in then he might have taken Sonny out. He won't make the same mistake this time."

Liston and Willie Reddish, his trainer, have evidently studied movies of the toughest fight of Clay's career, a bout with Billy Daniels in which Clay was tagged several times with a looping right hand over a left lead. Liston worked on this punch, too, with his sparring partners, but without notable success. His right hand is thrown awkwardly and slowly at a distance; it is most effective in close, where he uses a short right uppercut to the belly to bring an opponent's hands down and open him up for the left hook to the head.

In anticipation of the looping right, Clay has sparred a good deal of the time with a light heavy named James Ellis, who throws the punch—and much more quickly than Liston. He caught Clay with it several times but, like Daniels, he is a taller man than Liston, with a longer reach. If Liston persists in using this, for him, clumsy punch, it seems likely that it will only leave him vulnerable to countering rights by Clay. Both Richardson and Lincoln, in sparring sessions, hit Liston with short straight right-hands to the face when he threw the looping right. Neither of them was trying to knock Liston out, but Clay will be, and he has the punching power to succeed.

The early stages of the fight will probably be a contest of left jabs, with Clay's left quicker and longer and Liston's stronger. By the third round Clay should begin to open up, and it would not be surprising if he cut Liston some time between the third and sixth rounds.

Although both men are in superb condition, Clay is 23 years old to Liston's 30-odd. By the second half of the fight the younger Clay should be much fresher and stronger, and Liston will probably take a fearful battering until he is either knocked out or the fight is stopped.

While Liston's tactics in this fight will be to wait for an opening before committing himself, instead of chasing Clay as he did in the first fight, he is still a straight-line fighter, moving directly in on an opponent. He does not move well to either side. In training, while trying to develop more lateral movement—the idea is to cut the ring in half on Clay, thus preventing him from slipping sideways as José Torres did so effectively against Willie Pastrano—Liston looked clumsy and unsure of himself. And, oddly enough, he trained in a 15-foot ring, even though the fight will be held in a 20-foot ring. This was done on the dubious theory that the smaller ring would make him quicker; all it actually did was restrict the mobility of his sparring partners, making them easier for Liston to catch.

Clay, on the other hand, trained in a 20-foot ring—and used all of it. When he first went to his training camp in Chicopee Falls, Dundee discovered that a 12-foot ring had been built.

"We want a 20-foot ring," he said. "We gonna fight in a 20-foot ring, aren't we? I want Clay to be used to the size. I don't want him expecting ropes where there ain't gonna be ropes in the fight."

Liston's principal advantage during the training period was in the quality of his sparring partners. Lincoln and Richardson are main-event fighters, and good ones. The third sparring partner was changed several times, and the fact that he was never as good as Lincoln or Richardson did not really matter. In each case the man functioned more as a punching bag than anything else.

Clay used his brother Rudy, Cody Jones, Dave Bailey, and Ellis, the light heavyweight. He seemed reluctant to hit Bailey or Jones; Bailey had a bad back, and Jones had just come out of a hospital for treatment of his eyes. Clay, strangely, reserved his most damaging attacks for his brother, who apparently irritates him in the ring. Several times he staggered the younger Clay and had him on the verge of a knockout, only to ease off.

Refreshingly, neither Clay nor Liston has boasted much before this fight, although Clay could not forebear from predicting a dire but unspecified end for Liston.

"If I told you what was gonna happen, you wouldn't even bother to show up," he said.

Liston, who growled threats like a sleepy bear before the fight in Miami, has been much more cautious this time.

"I took him too light before," he said. "That was one of my mistakes. This time I'm gonna bring my lunch. We may be there a long time."

Liston was in rare good humor while training for this fight. After his workouts in Dedham, Mass., and before moving north to Maine last weekend, he spent the early evenings in a drugstore, listening to interminable repetitions of a song called My Girl, played for him by the teenagers inhabiting the soda fountain, amiably signing autographs and kidding with the youngsters. On his last night in Dedham his new-found friends presented him with a small gift and a card reading: "Win, lose or draw, you will always be our champ."

Unless the left hook comes through, that will be Liston's happiest souvenir from New England.

SI's 100 Greatest Photos of Muhammad Ali

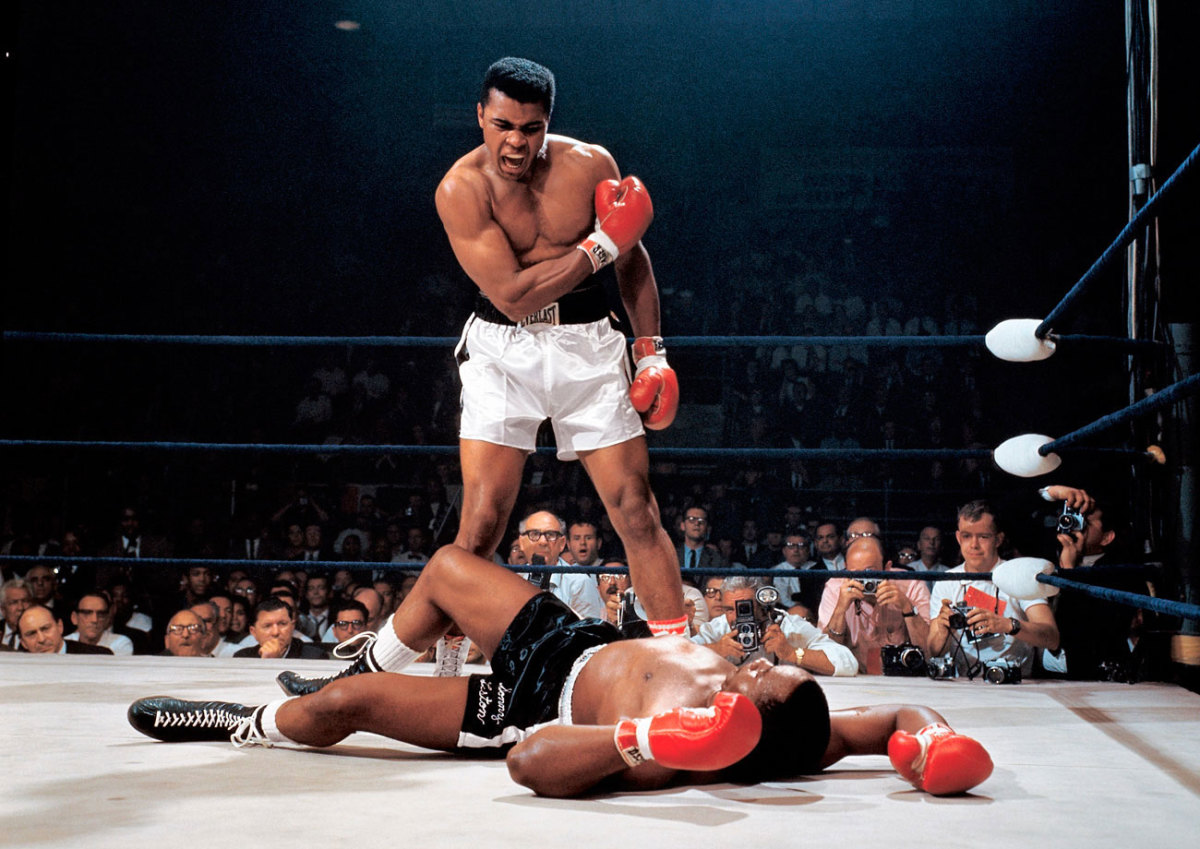

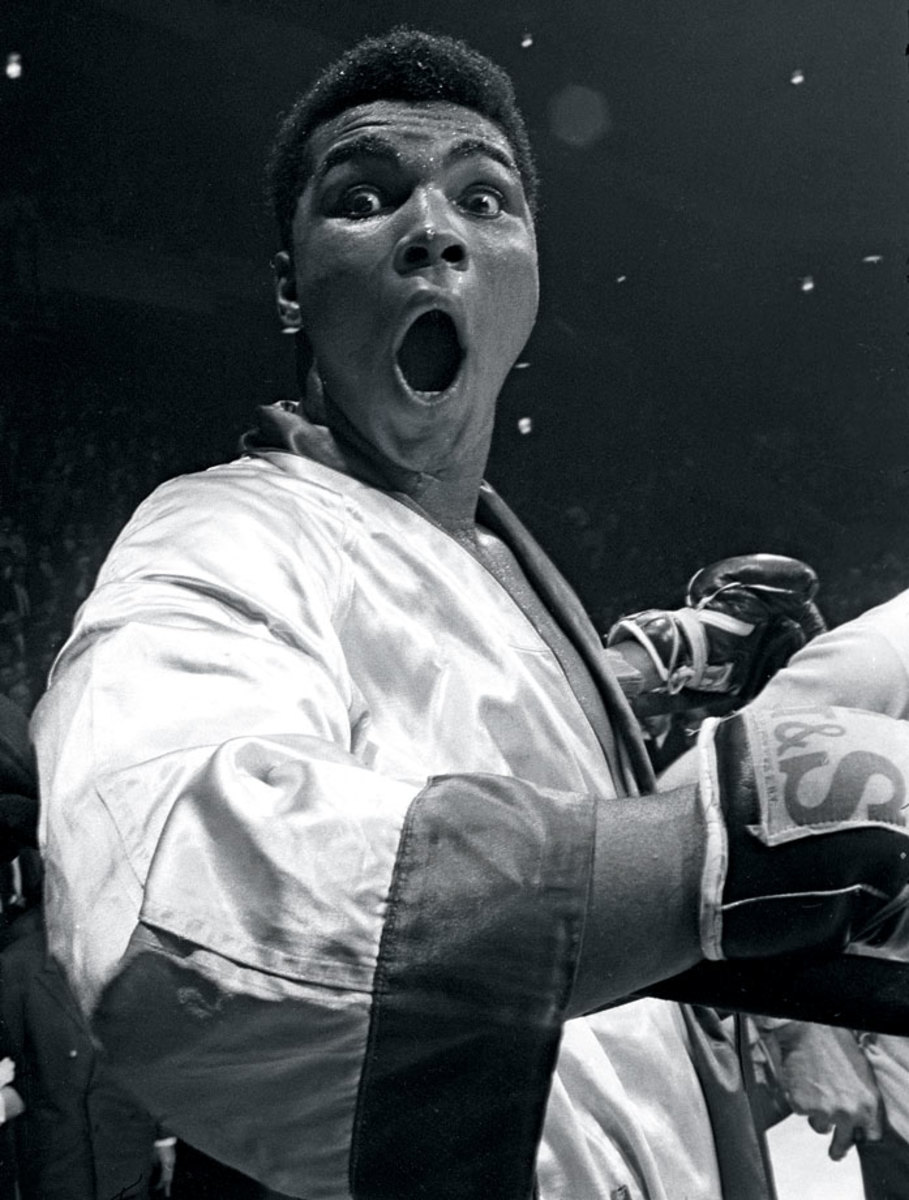

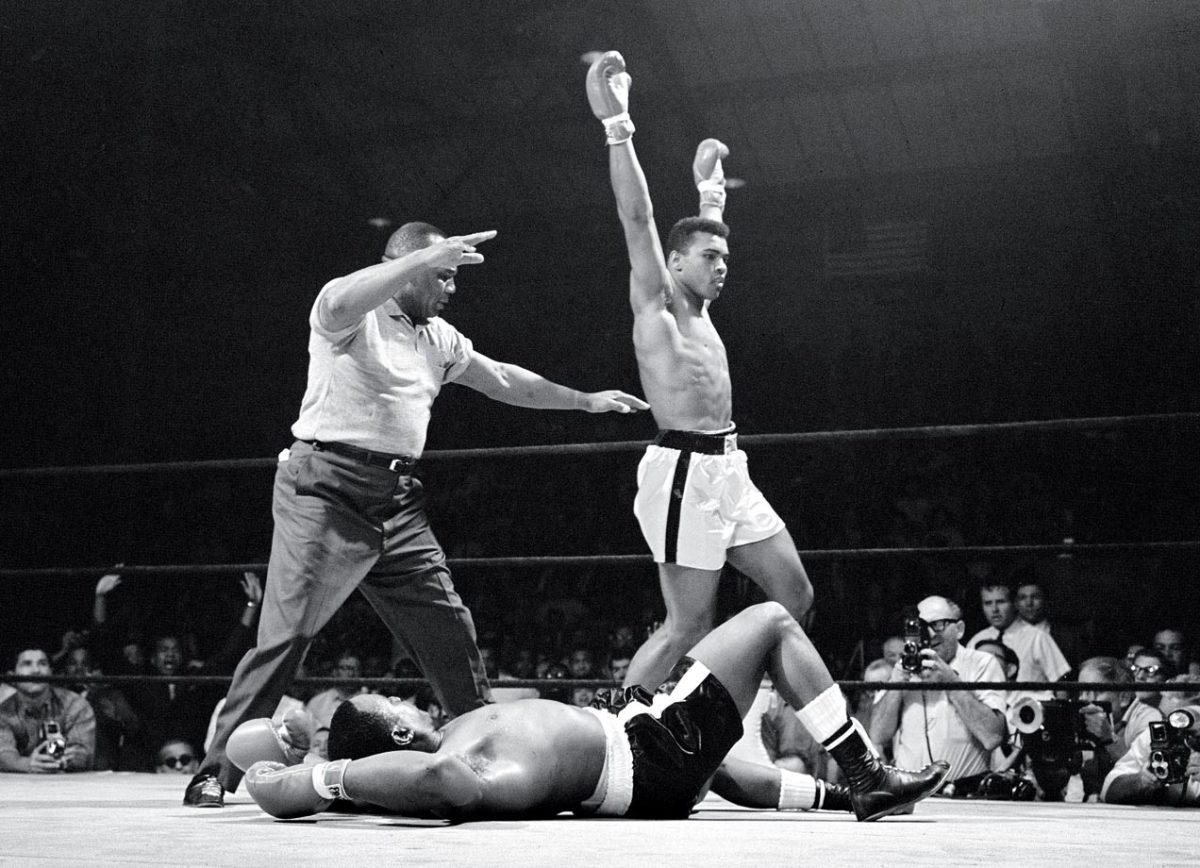

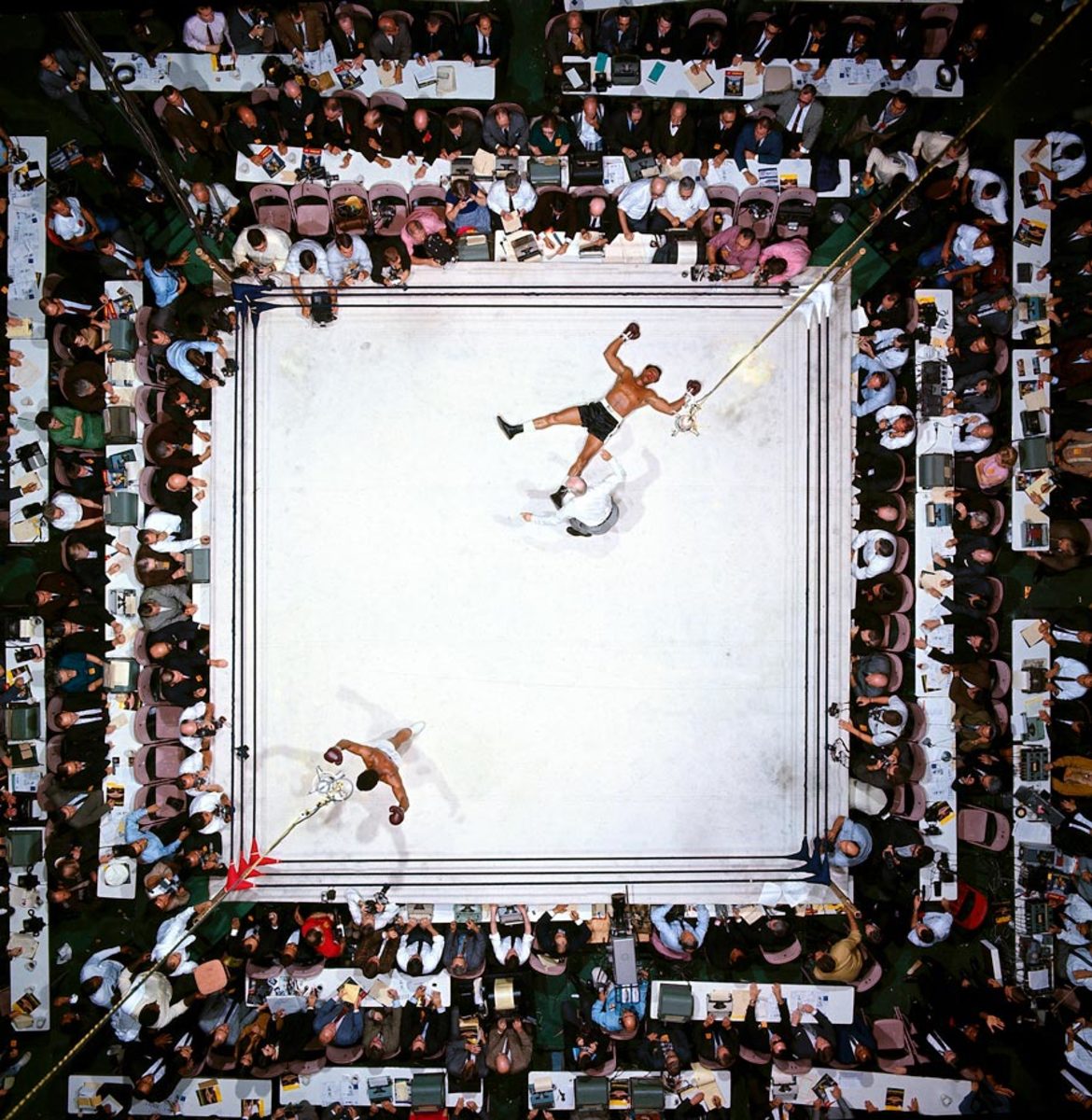

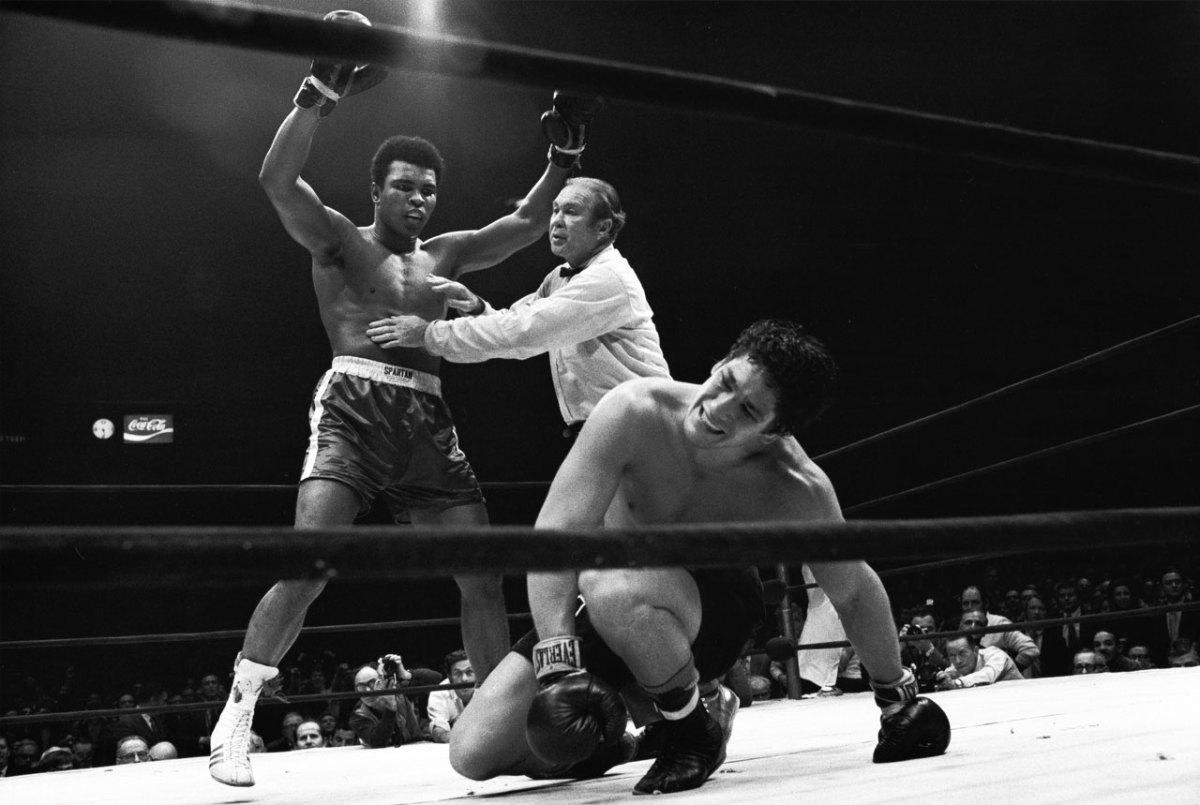

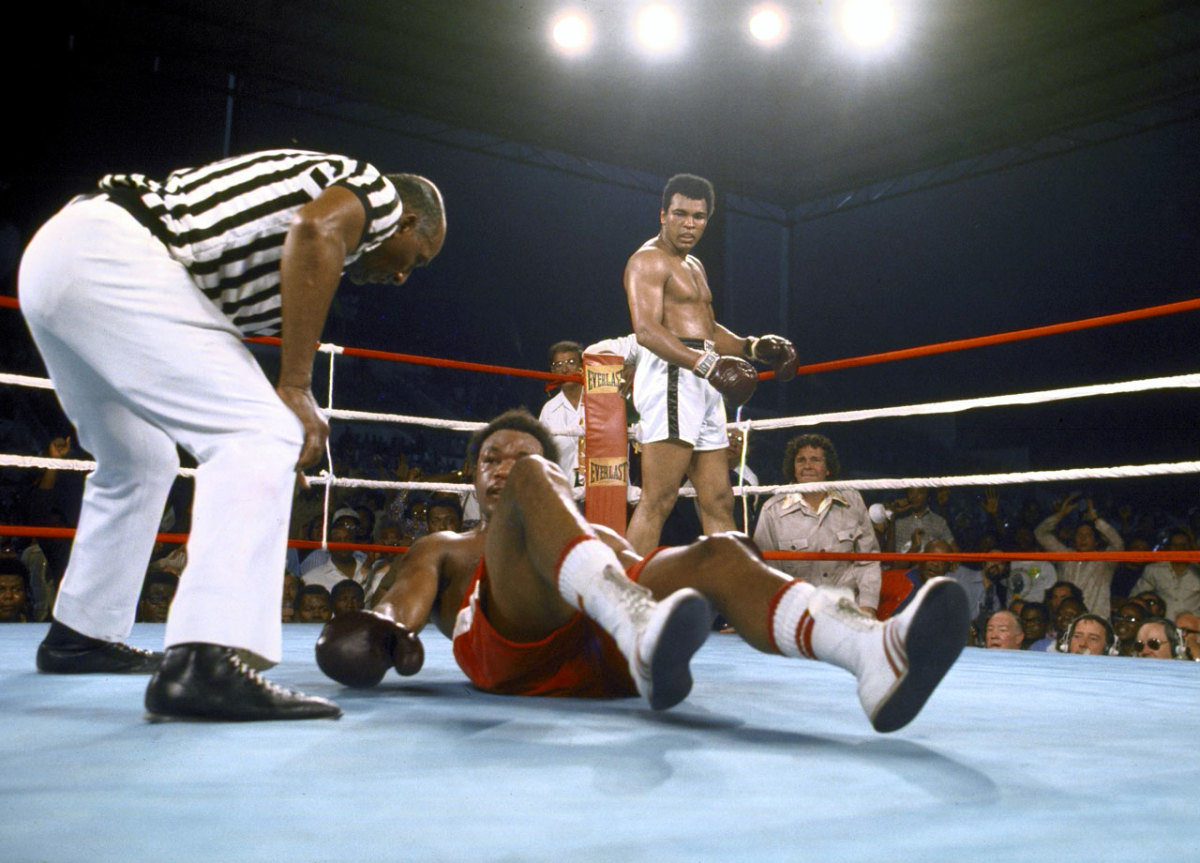

In one of the most iconic and controversial moments of his career, Ali stands over Sonny Liston and yells at him after knocking the former champ down in the first round of their 1965 rematch. Skeptics dubbed it "the Phantom Punch," but films show Ali's flashing right caught Liston flush, knocking him to the canvas. Refusing to go to a neutral corner, Ali stood over Liston and told him to "get up and fight, sucker."

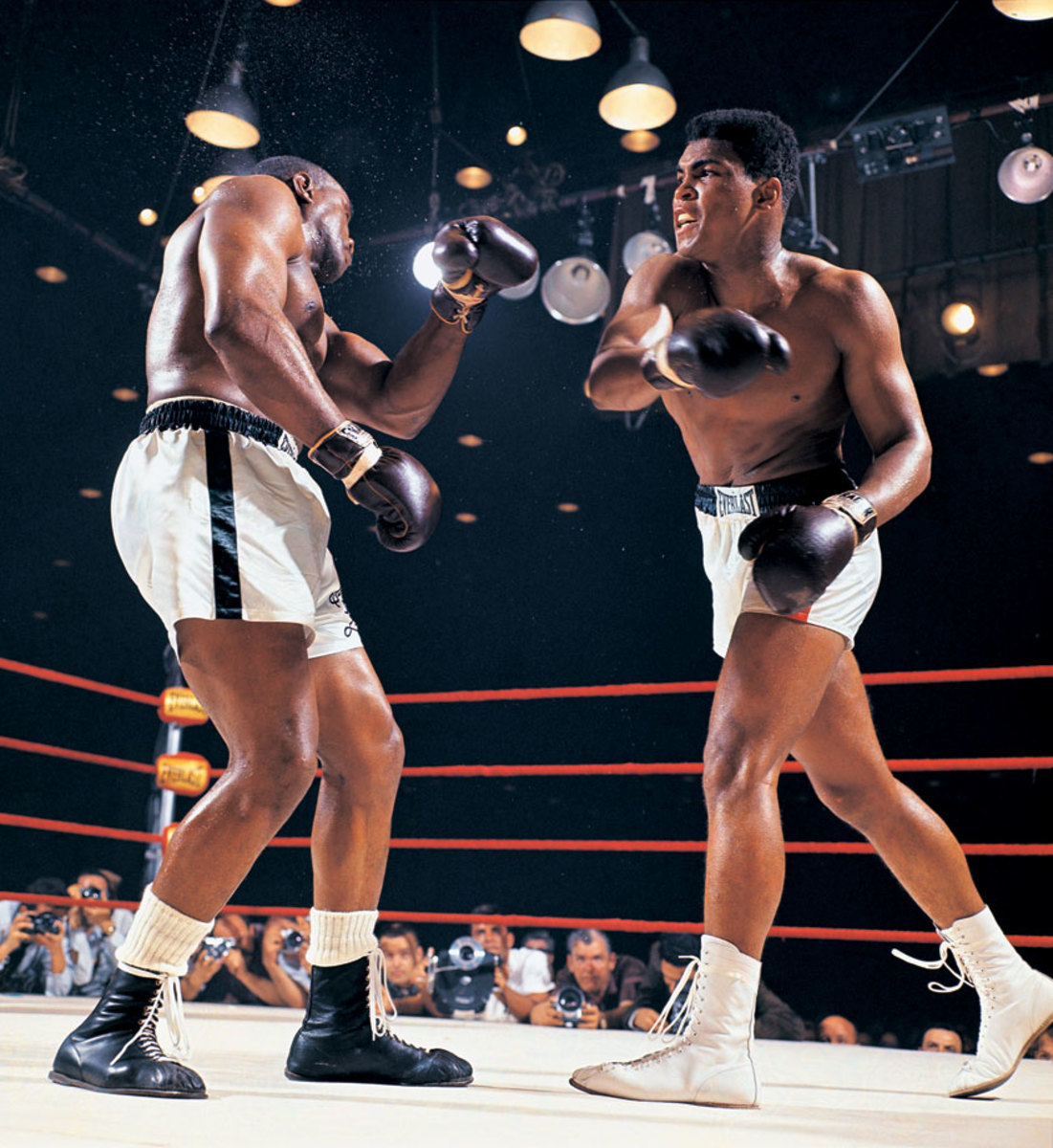

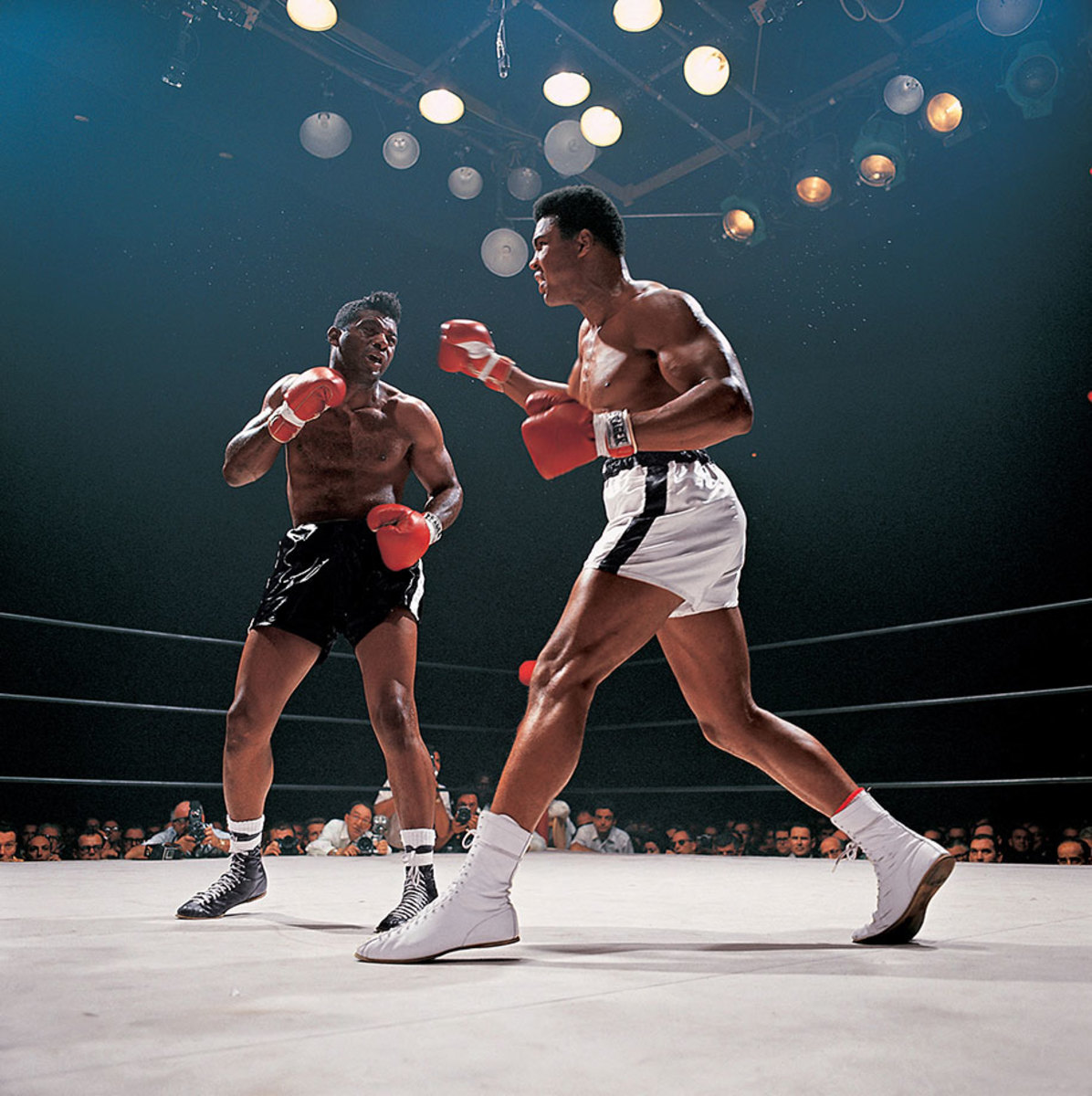

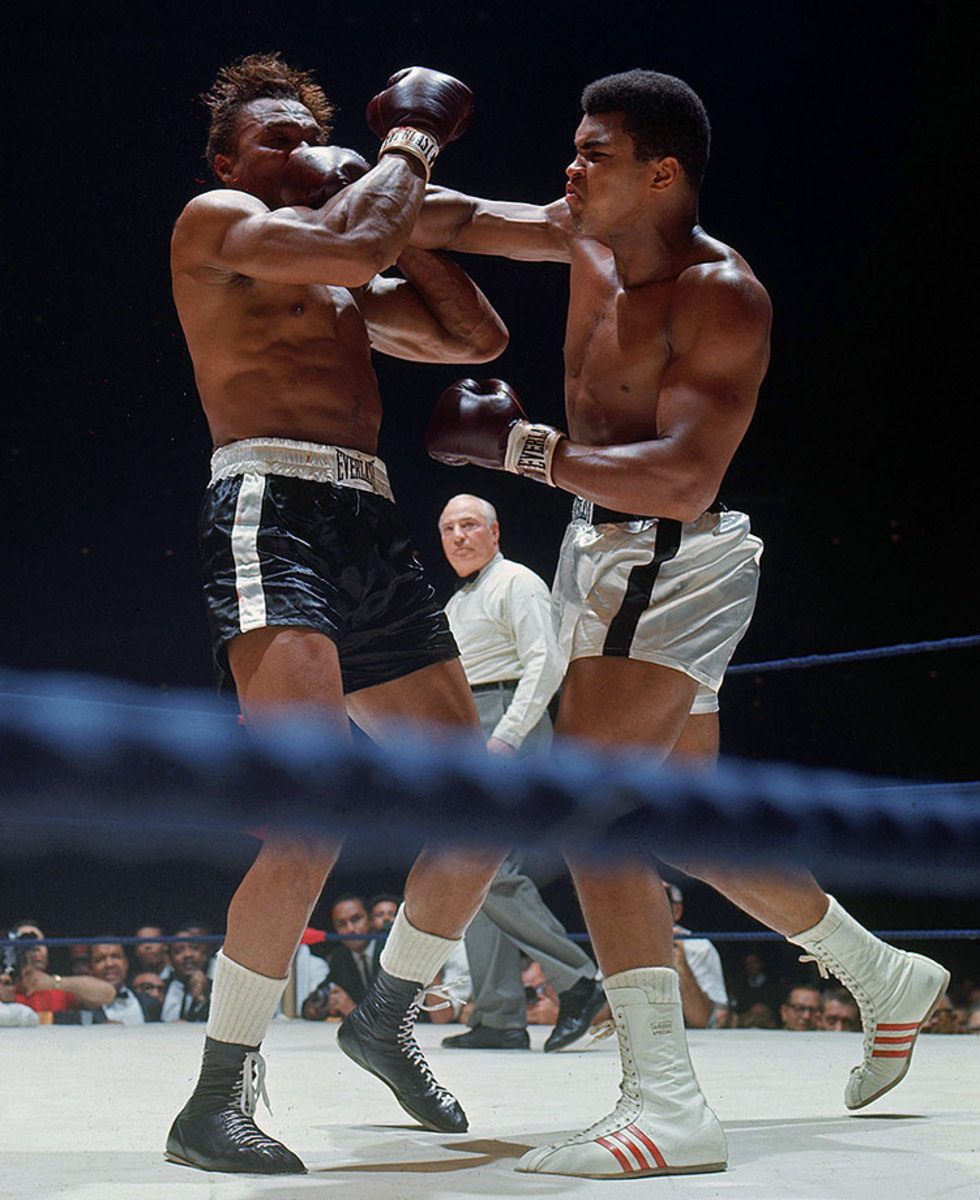

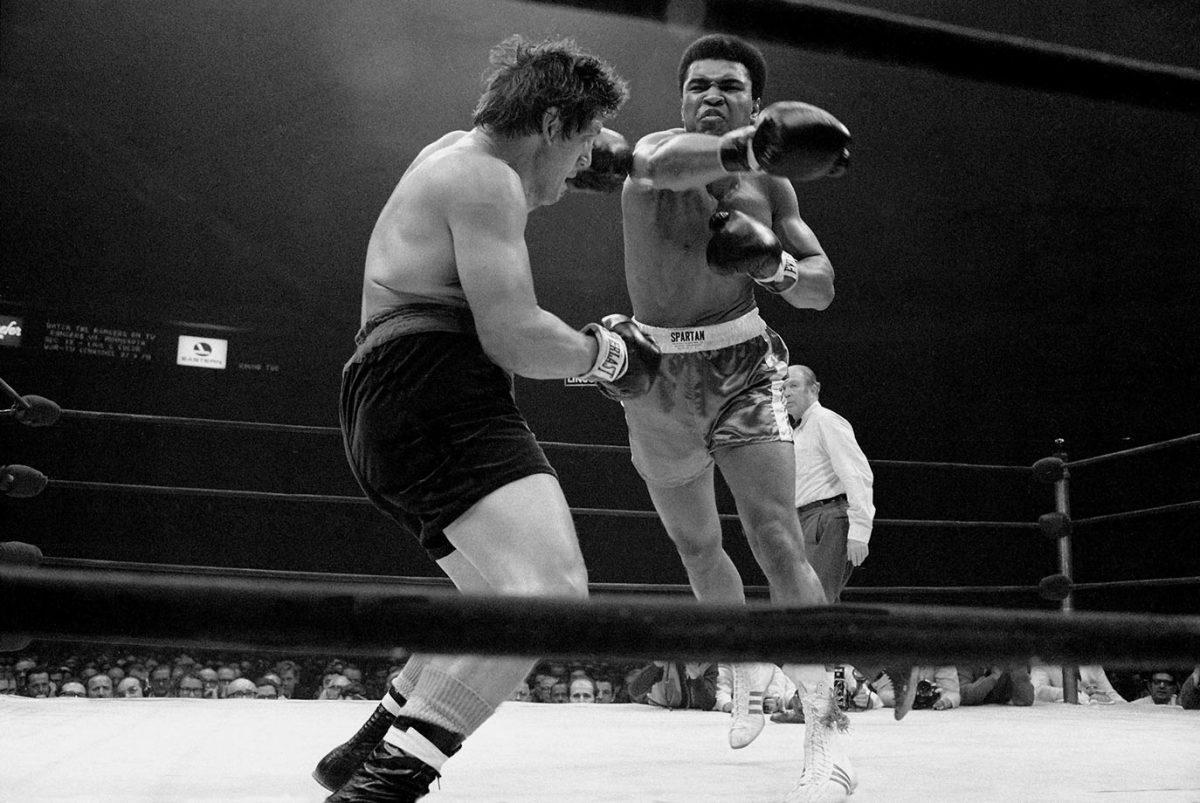

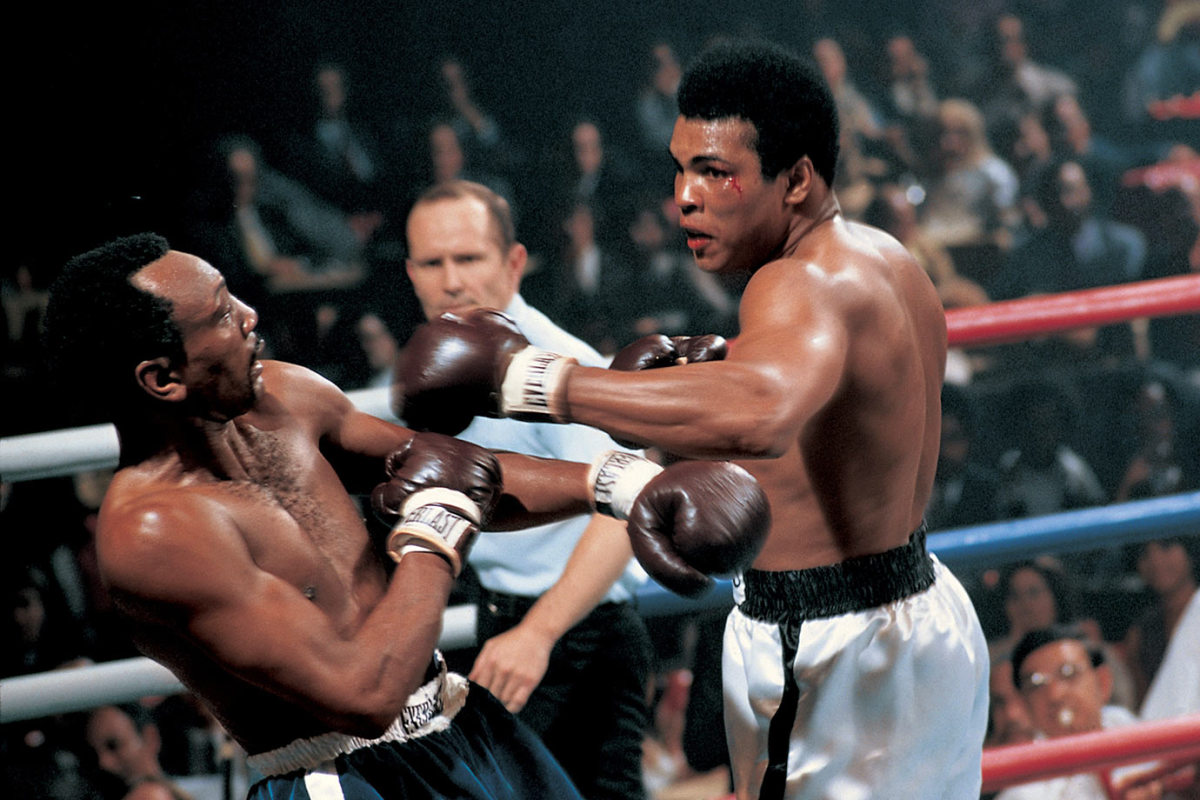

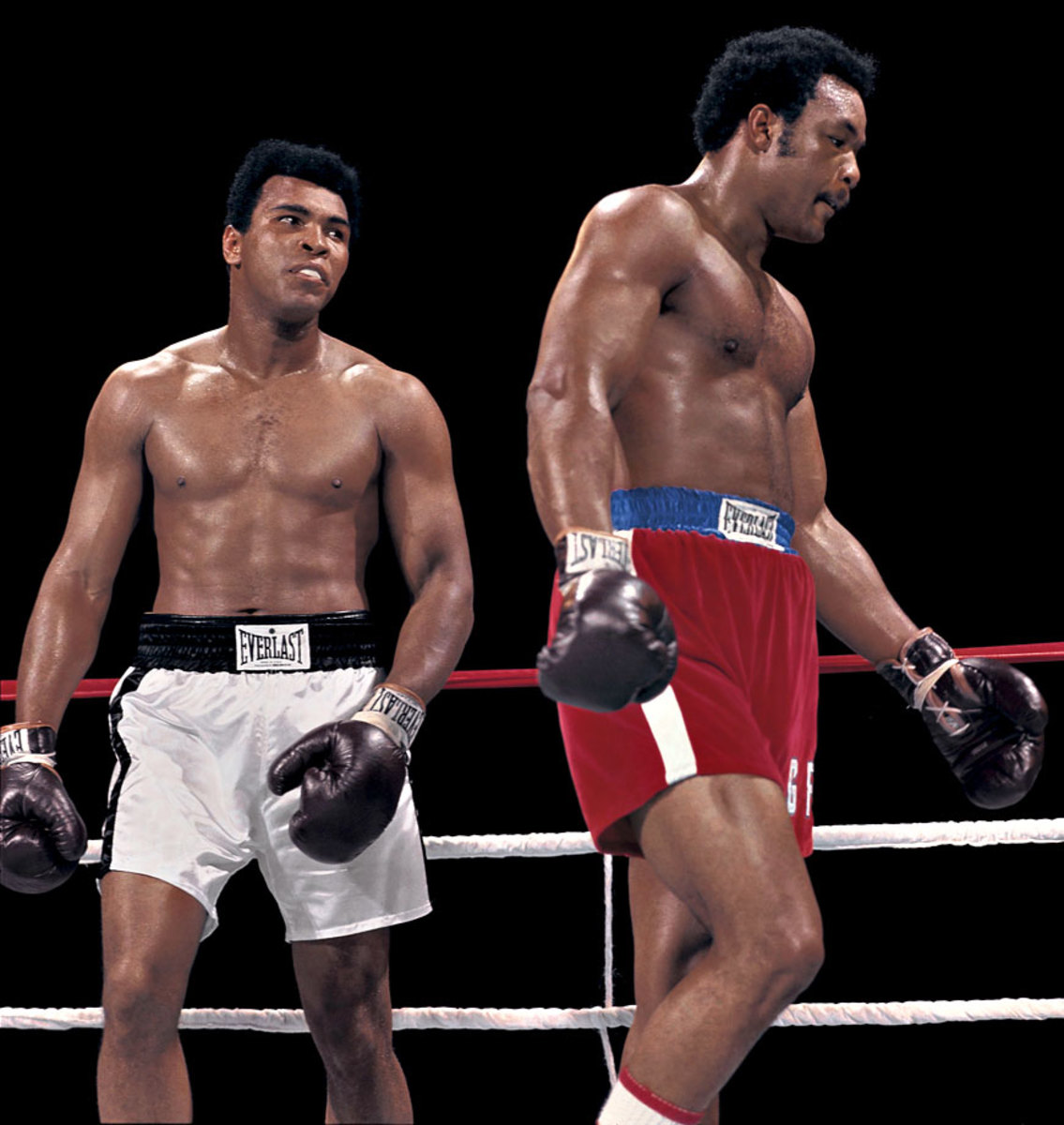

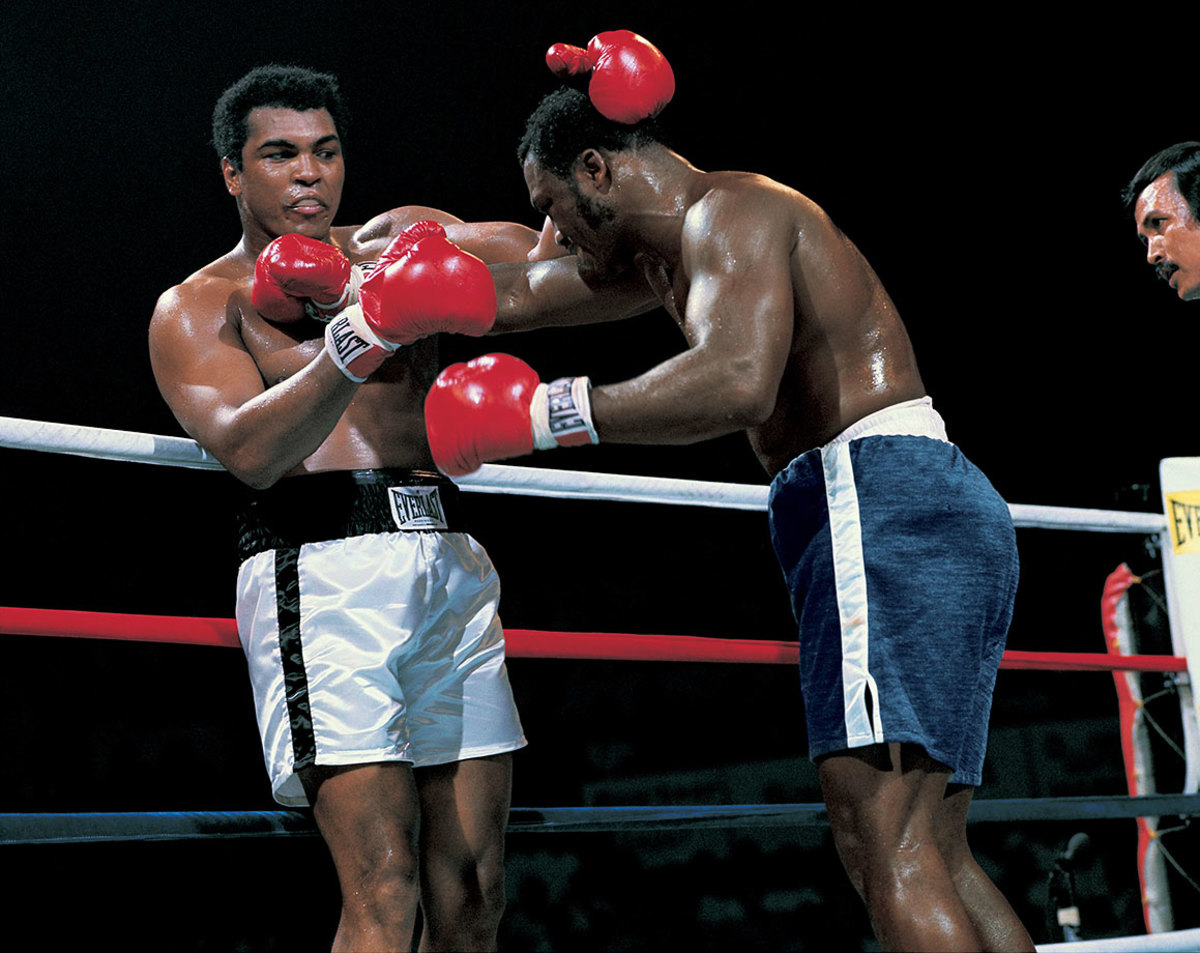

At 22-years-old, Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) battered the heavily favored Sonny Liston in a bout that shook the boxing world. The fight ignited the career of one of sports' most charismatic and controversial figures, whose bouts often became social and political events rather than simply sports contests. At the peak of his fame, Muhammad Ali was the best known athlete in the world. Liston, one of the most feared heavyweight champions in history, was a 1-8 favorite over the young challenger known as the Louisville Lip. But Clay, here stinging the champ with a right, used his dazzling speed and constant movement to dominate the action and pile up points.

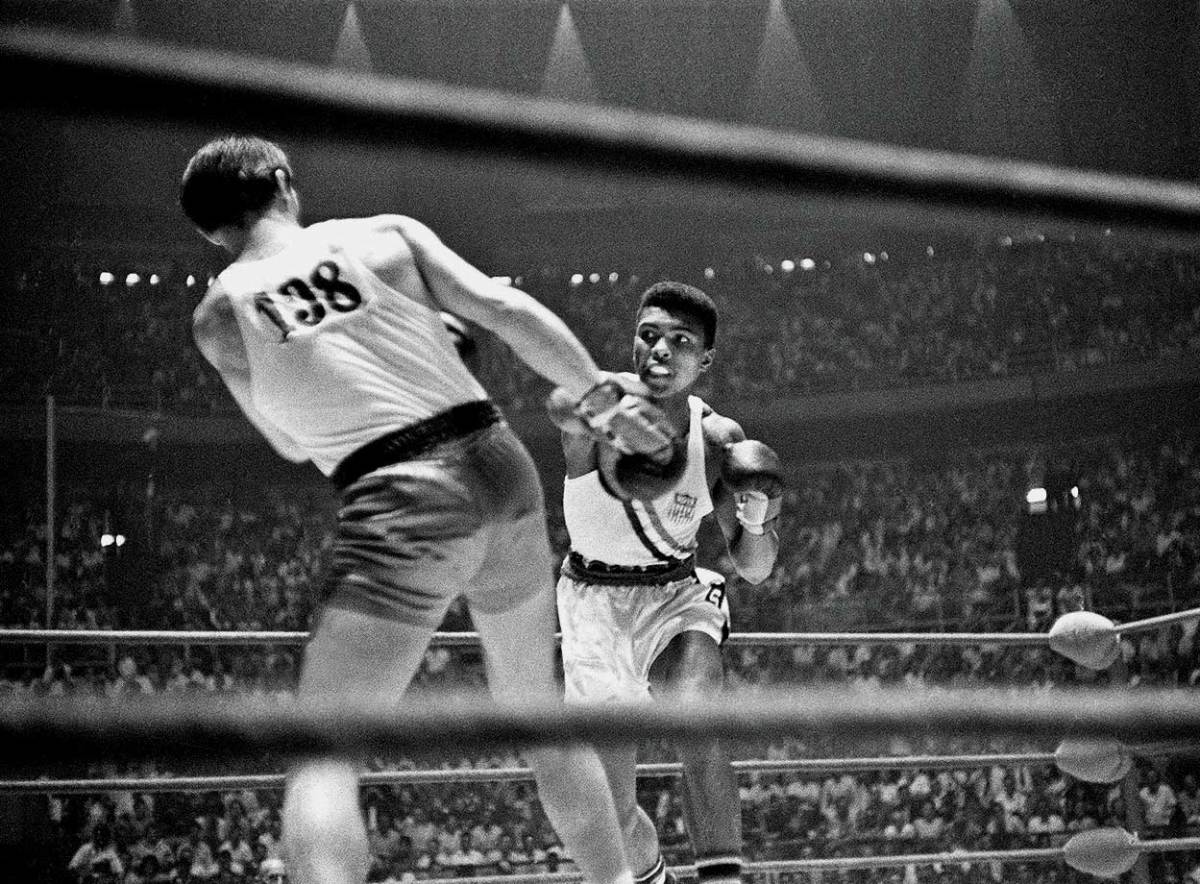

Cassius Clay punches Zbigniew Pietrzykowski of Poland during their gold medal bout at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Clay defeated Pietrzykowski 5-0 for the light heavyweight gold medal.

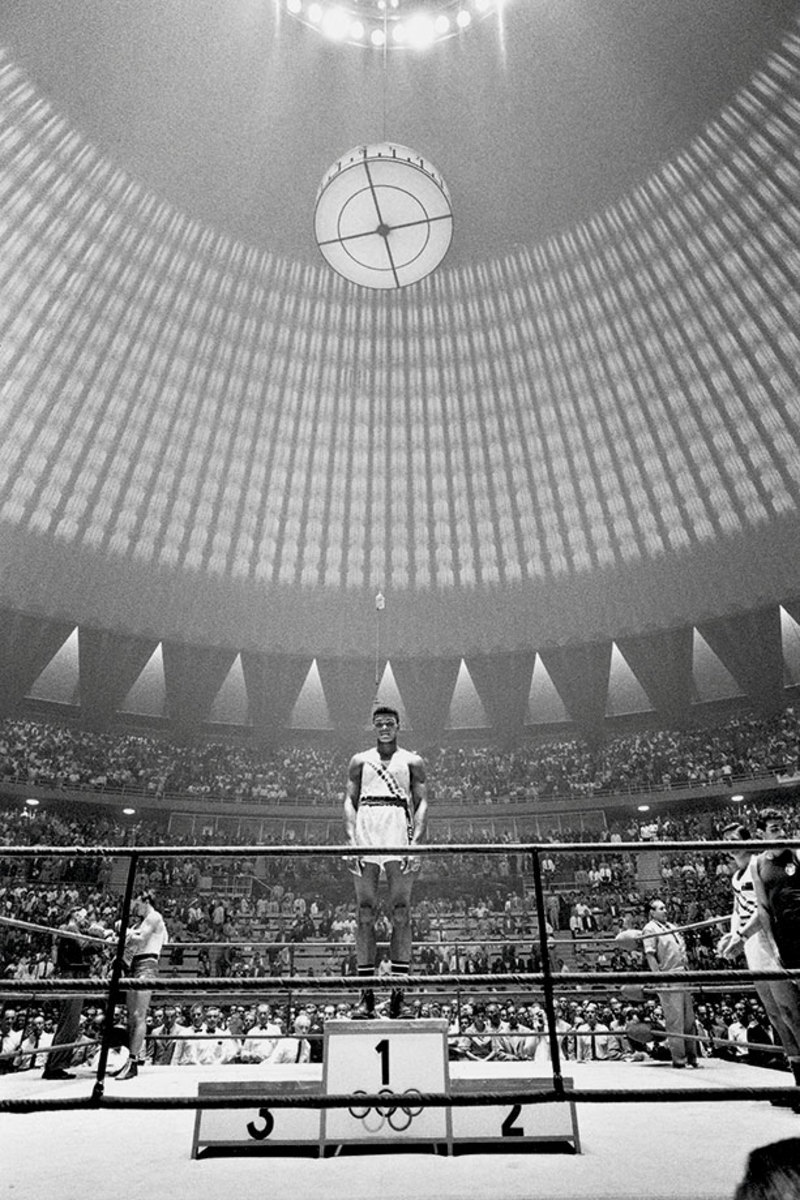

For the 18-year-old from Louisville, here atop the medal stand after his Olympic victory, all roads led from Rome. Clay finished his amateur career with a record of 100-5 and made his professional debut two months after the Games.

Undefeated in his first 17 pro fights, Clay mugged for the camera before the start of his 1963 bout against Doug Jones in Madison Square Garden.

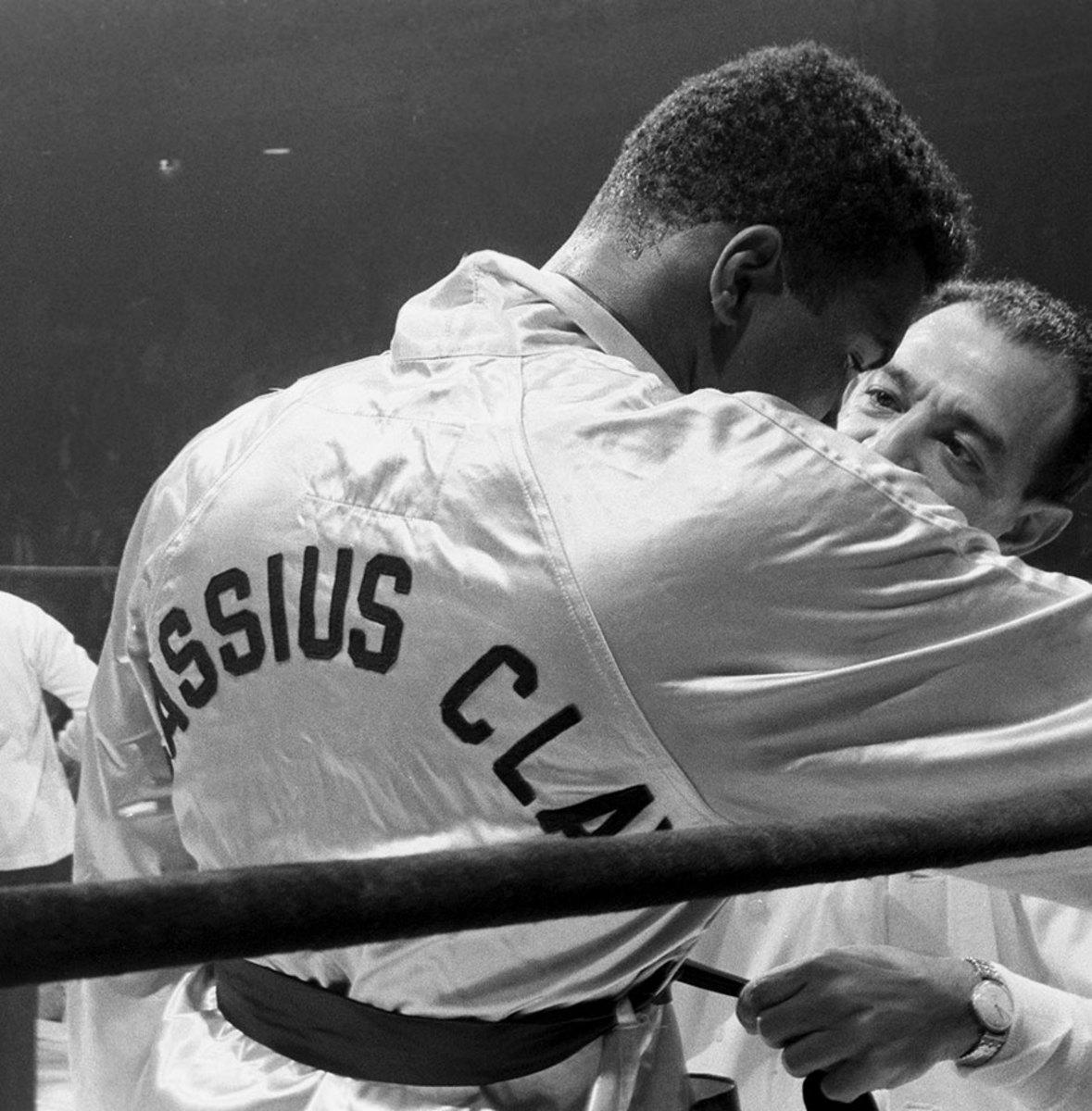

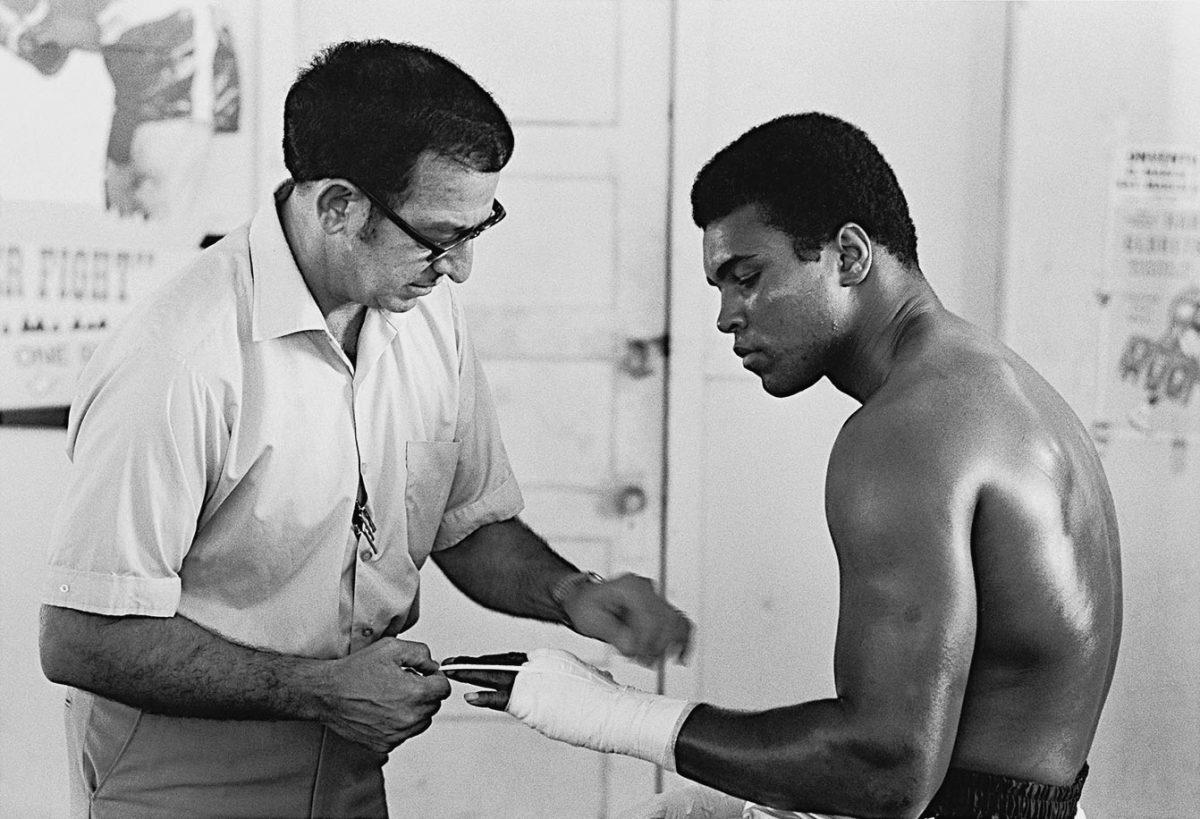

Trainer Angelo Dundee urged his young charge to get serious before the opening bell against Jones. Clay followed instructions and emerged from a tough fight with a unanimous decision victory. Three months later he would stop Henry Cooper and close out 1963 at 19-0.

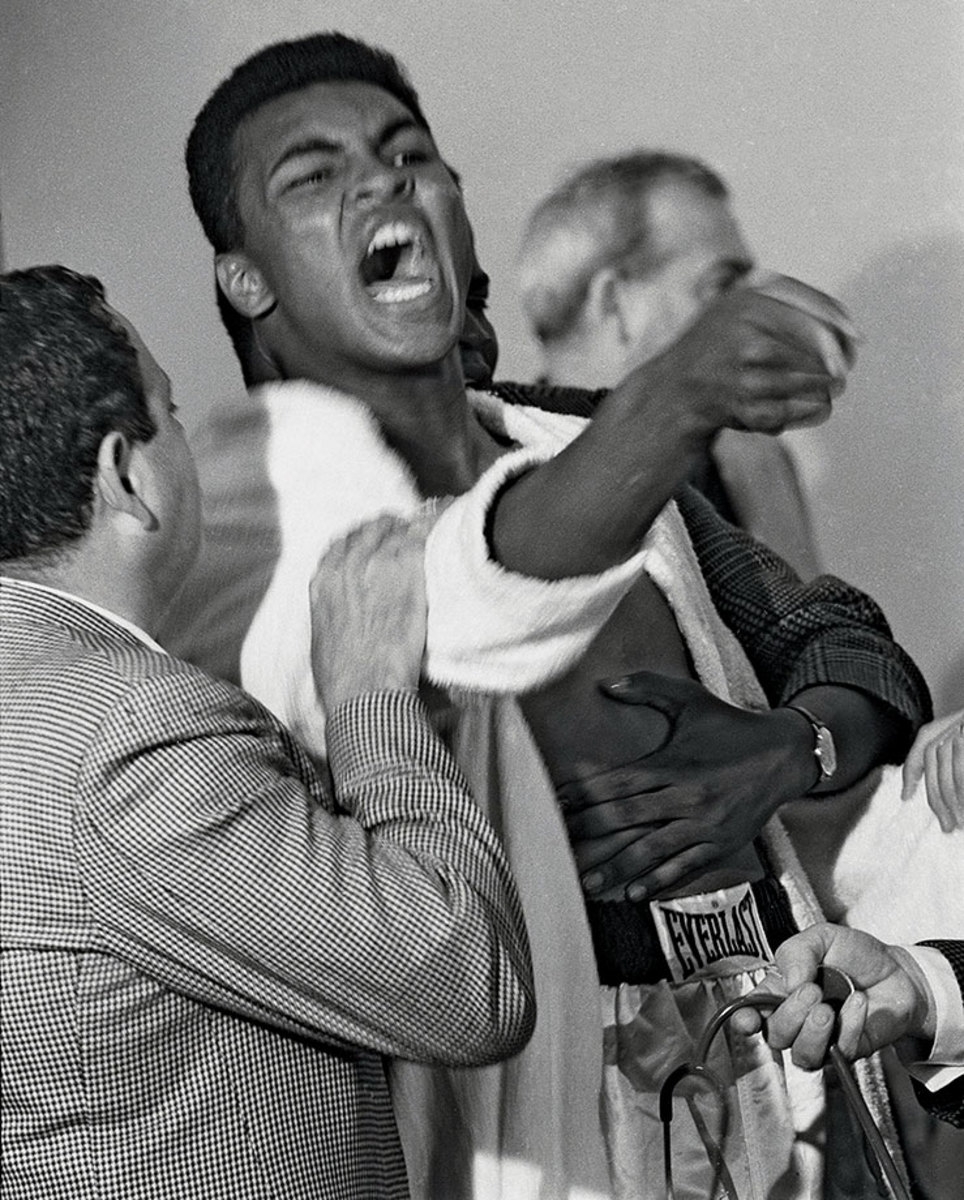

A seemingly hysterical Clay taunted Sonny Liston during the pre-fight physical for their 1964 bout. He had consistently baited the Big Bear during the lead-up to the fight, saying he was going to "use him as a bearskin rug ... after I whup him." The Miami Boxing Commission would fine Clay $2,500 for his outburst at the physical.

"I shook up the world!" an emotional Clay hollered to ringside reporters after his shocking defeat of Liston. And he did just that, claiming the heavyweight title at age 21 after a clearly beaten Liston, complaining of a shoulder injury, failed to answer the bell for the seventh round.

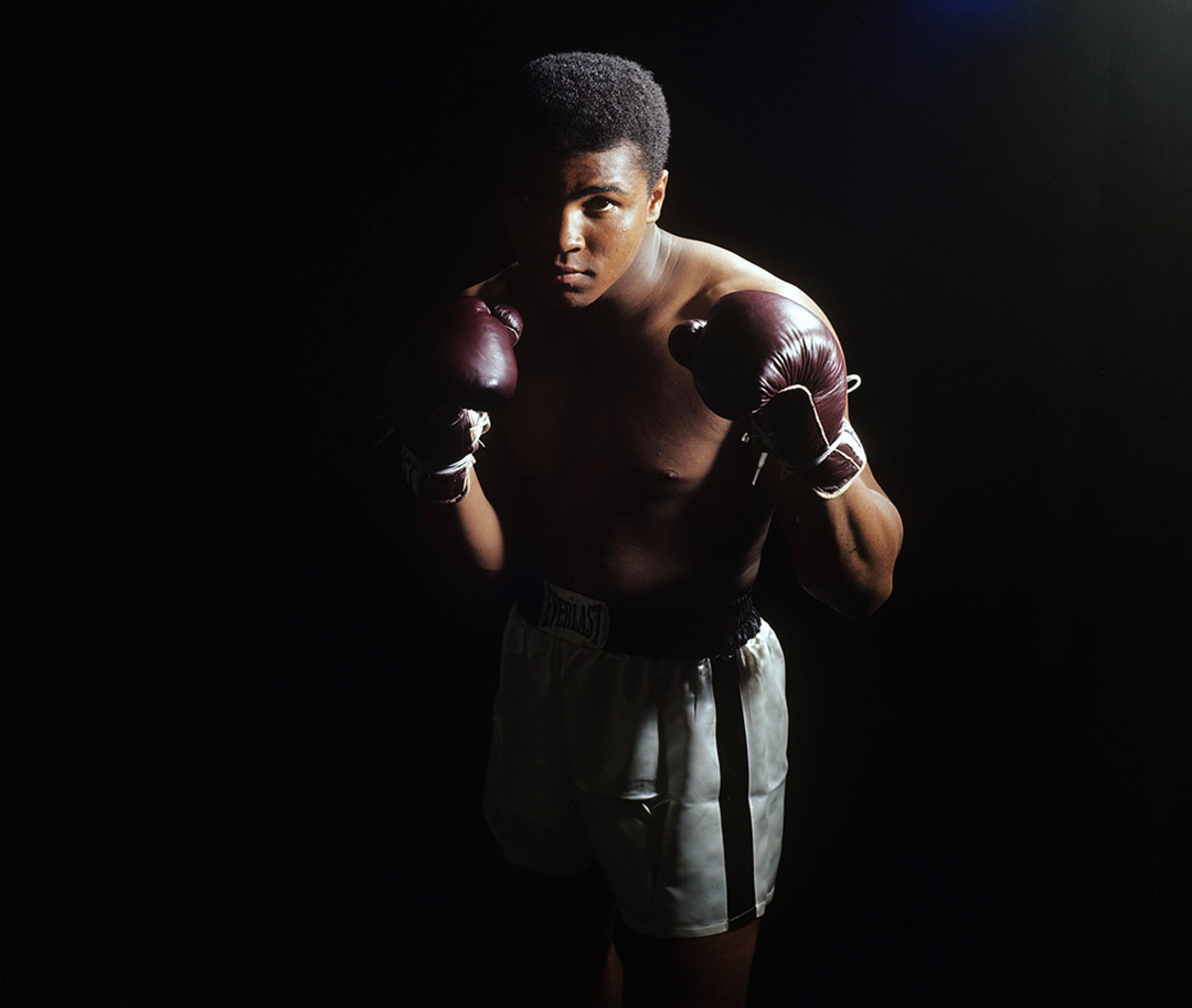

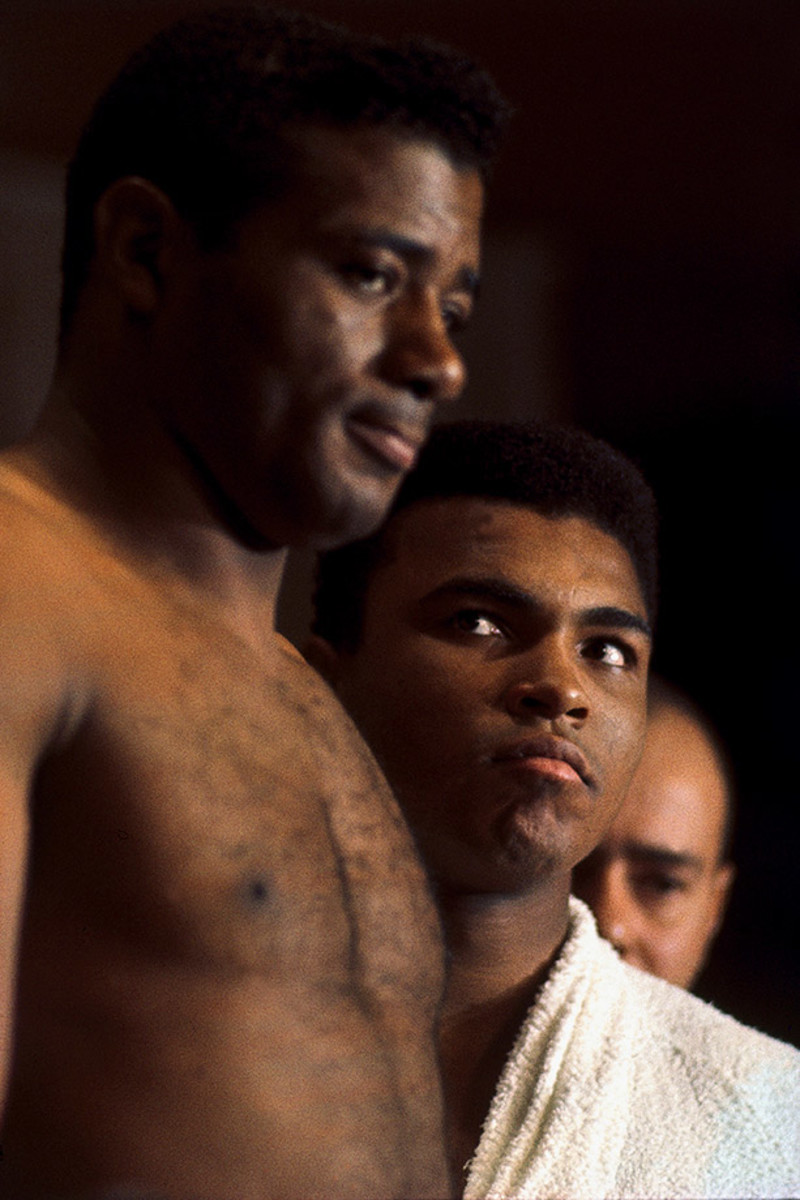

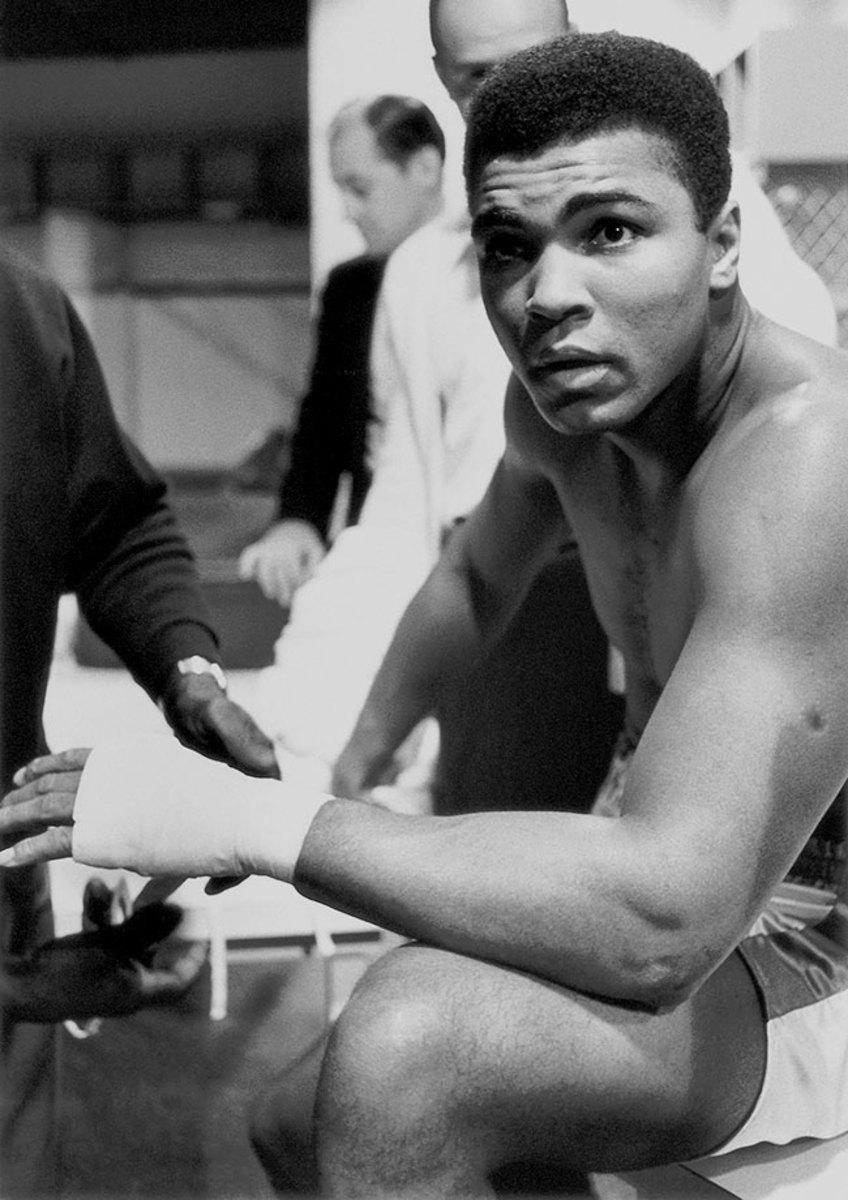

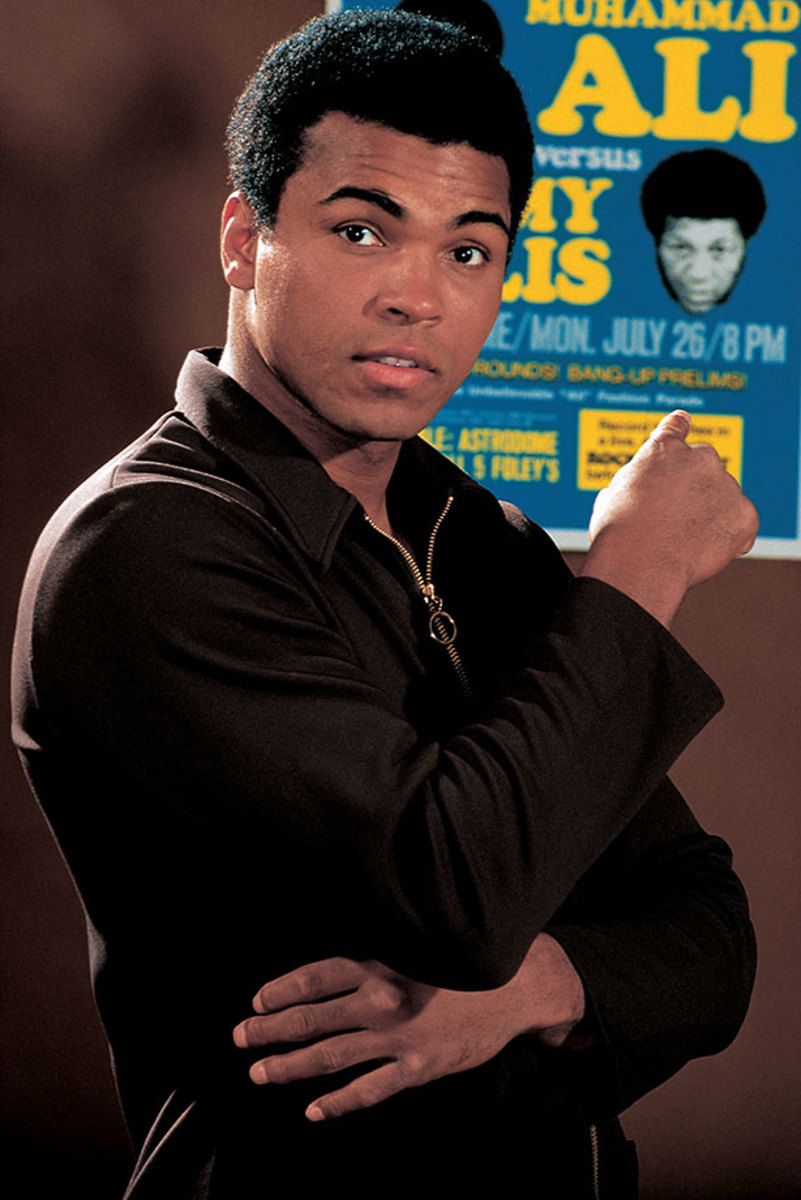

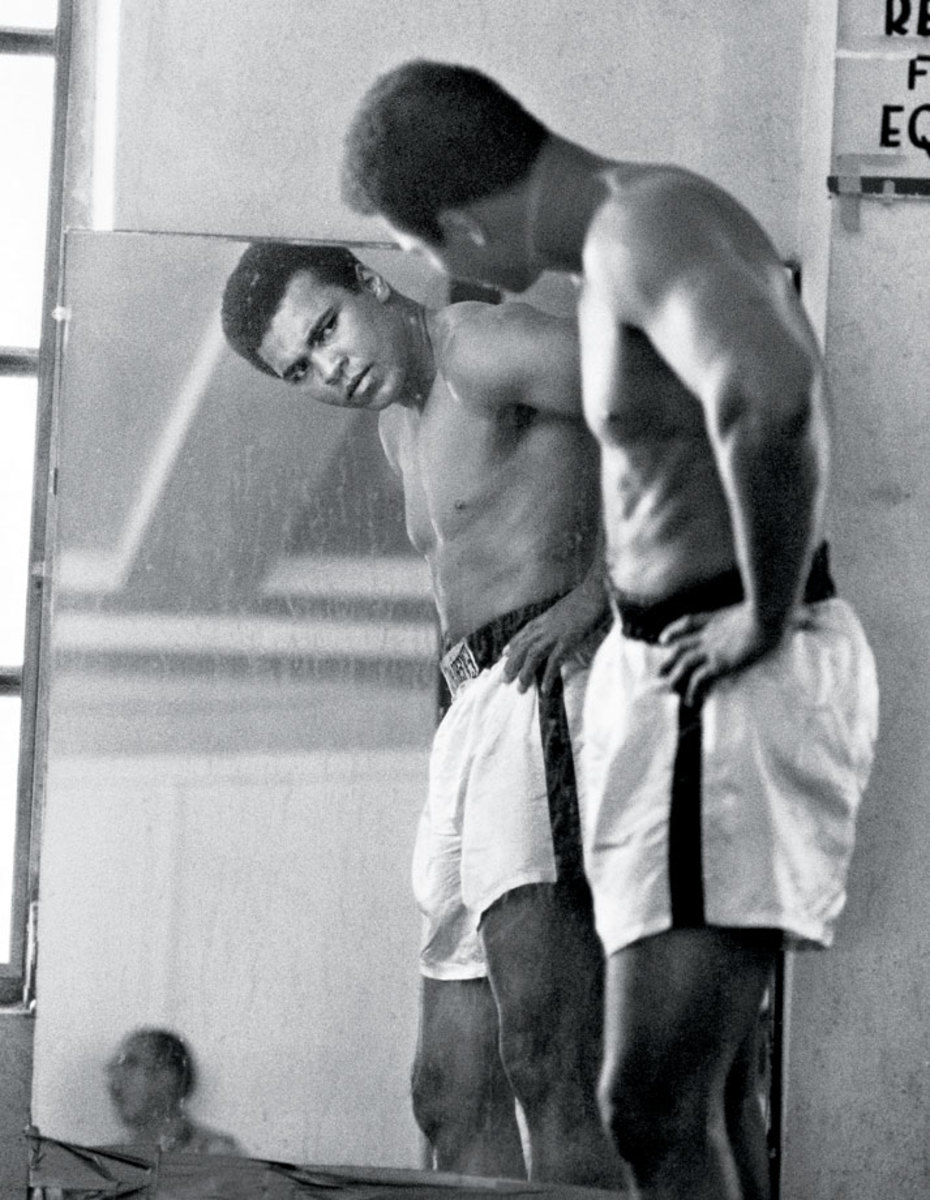

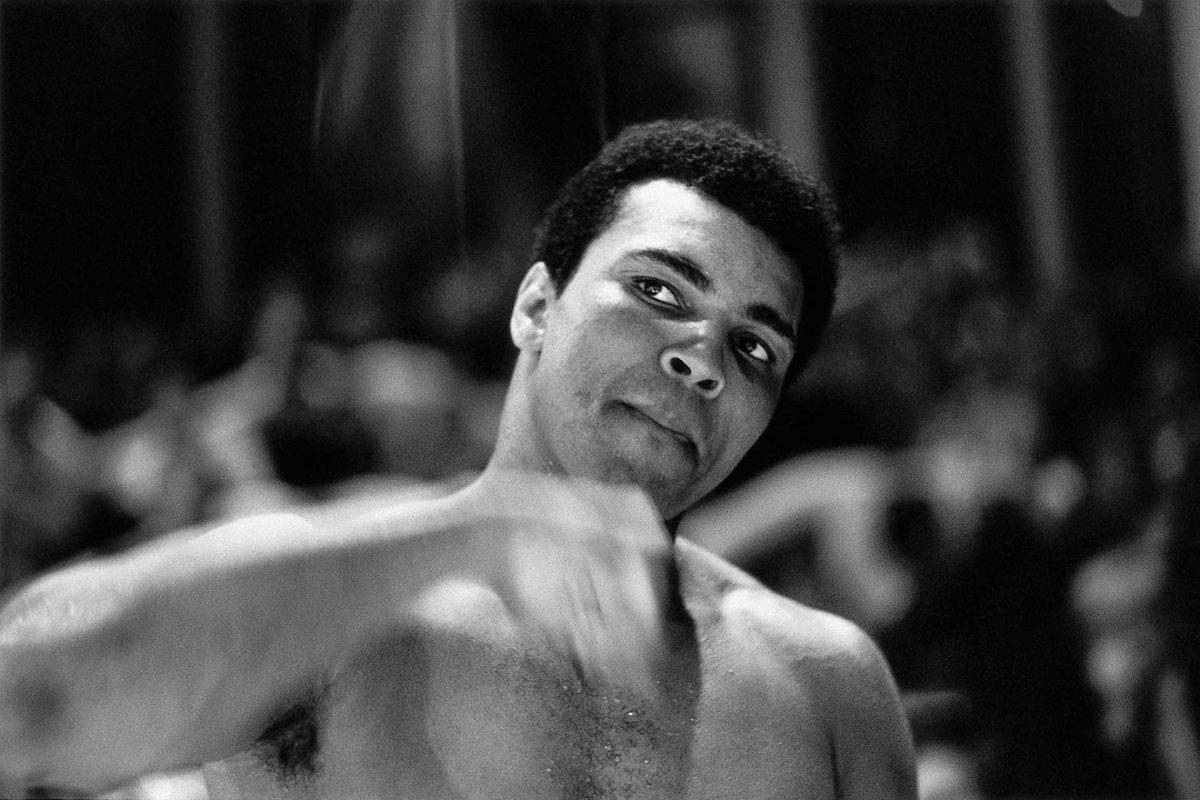

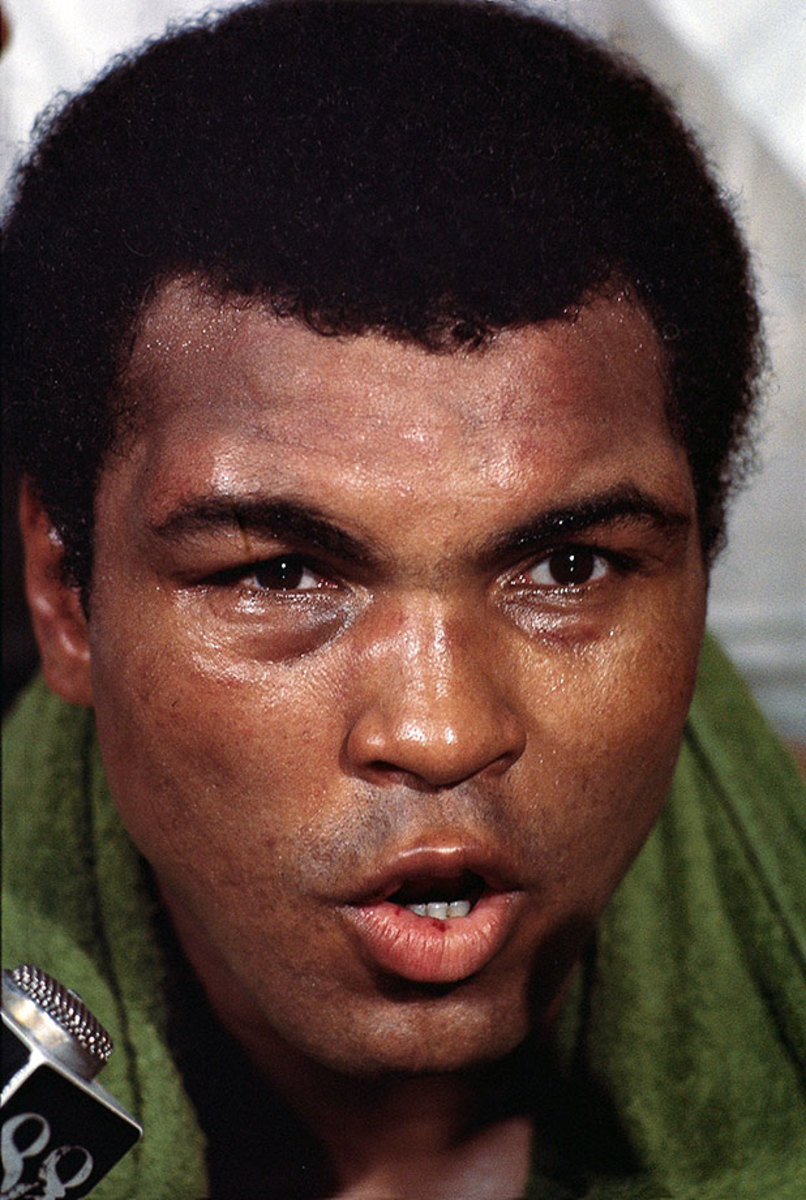

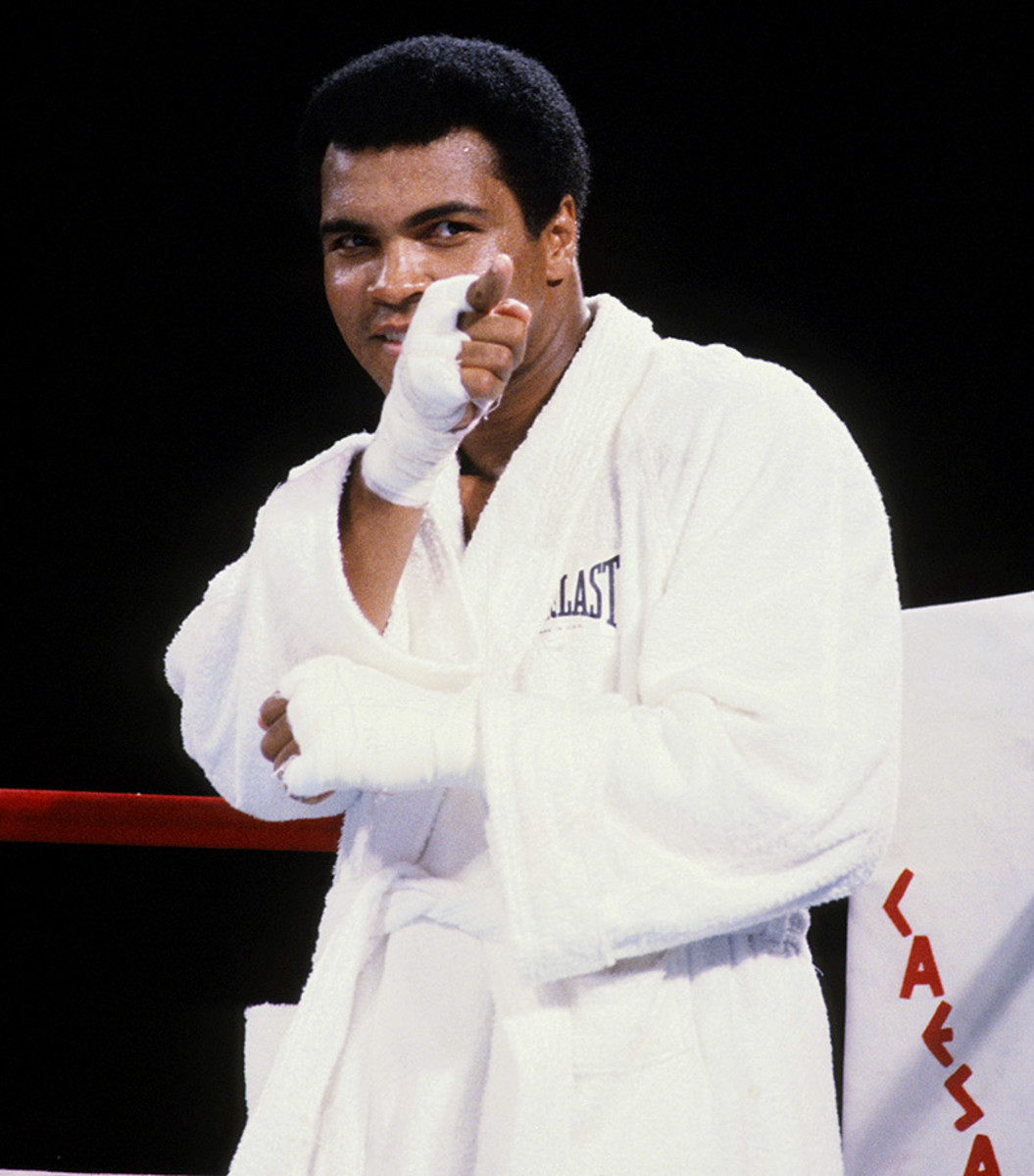

Draped in shadow, the young king — now known as Muhammad Ali — stared down the camera during a photo shoot in April 1965, one month before his rematch against Sonny Liston.

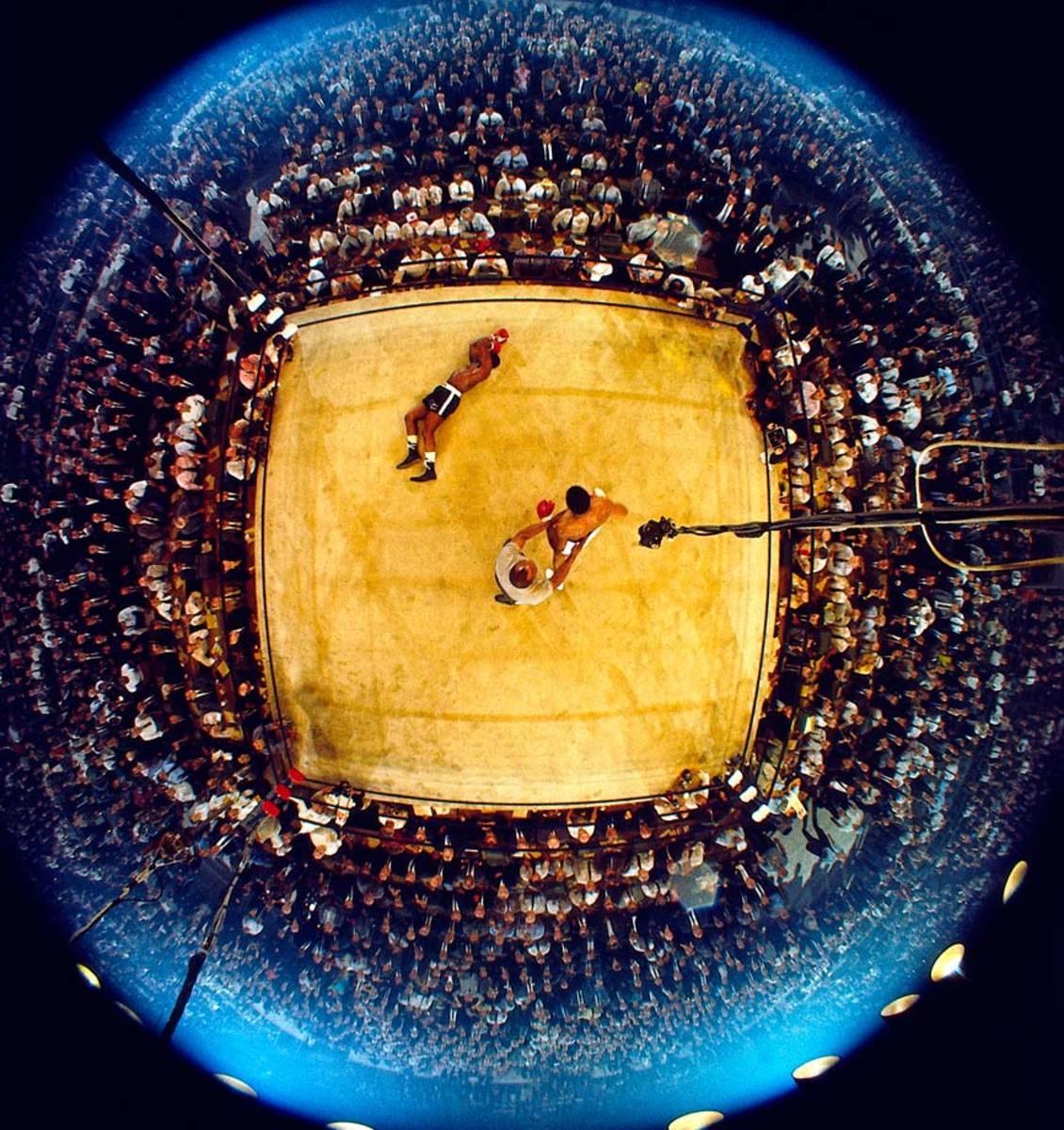

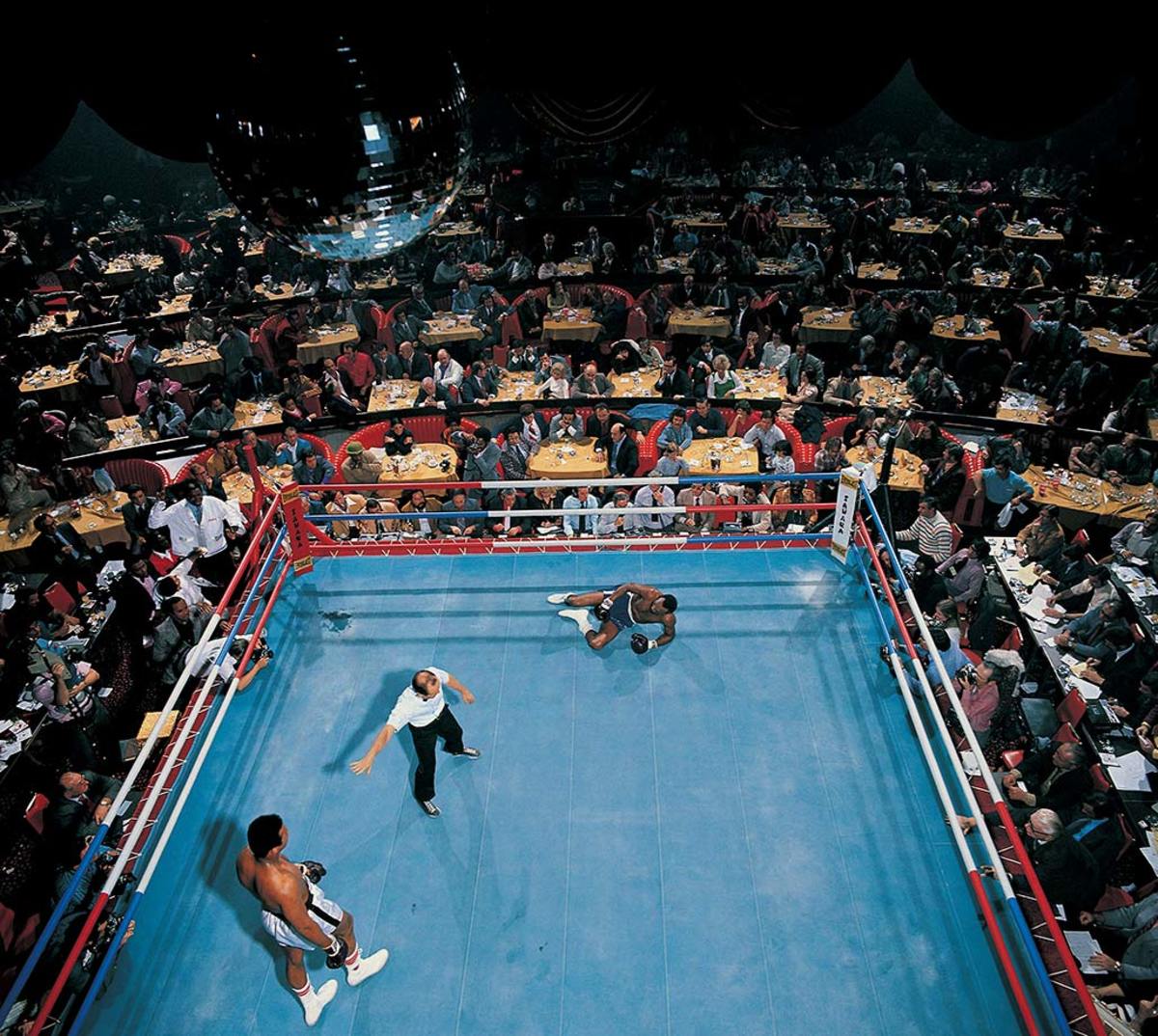

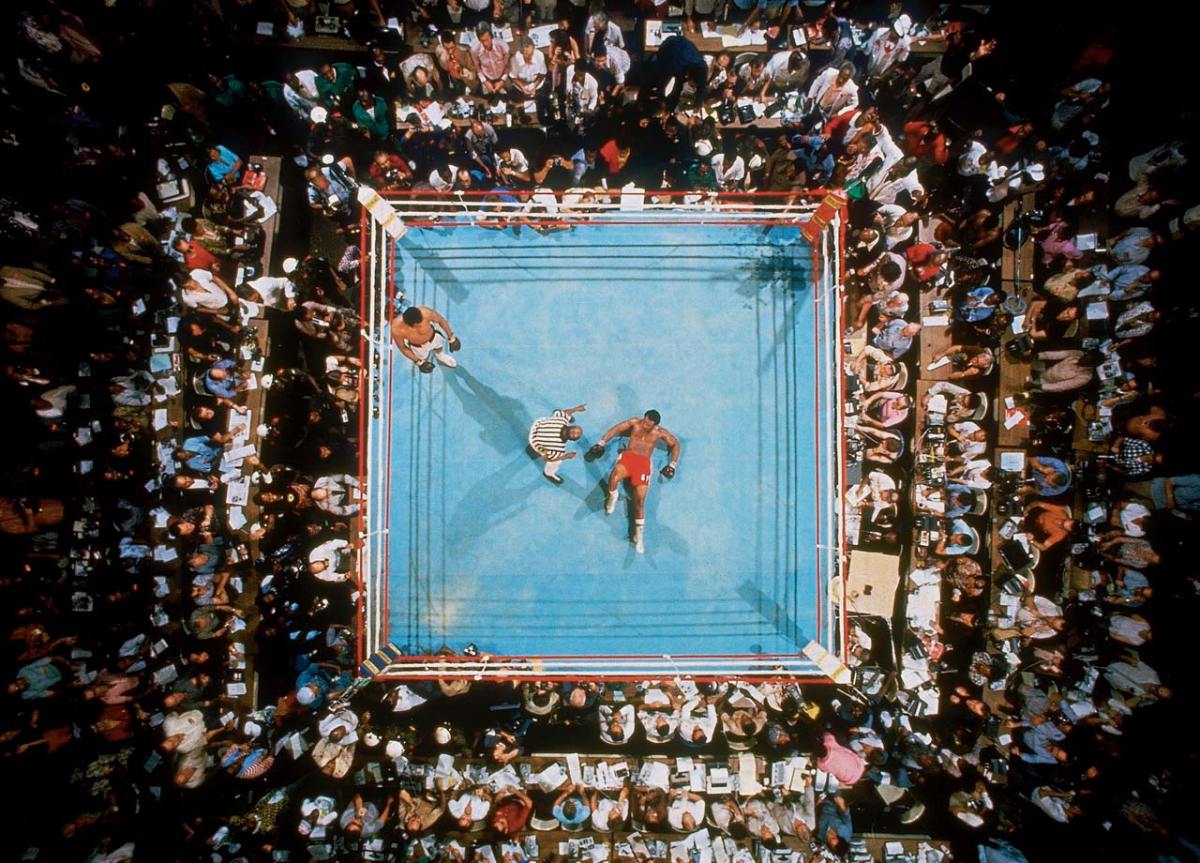

As Liston lingered on the canvas and the referee, former heavyweight champ Jersey Joe Walcott, tried to control Ali, the 2,434 spectators on hand in the Lewiston, Me., hockey arena — a record low for a heavyweight championship fight — tried to make sense of what all that had happened in less than two minutes after the opening bell.

The celebration over Liston continued. In a chaotic ending, Ali was awarded a knockout when Nat Fleischer, publisher of The Ring, informed referee Jersey Joe Walcott from ringside that Liston had been on the canvas for longer than 10 seconds after Ali knocked him down. The bout remains one of the most controversial in boxing history, with many observers insisting that Liston took a dive.

Ali's second title defense came in November 1965, against former two-time heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. During the build-up to the bout, the normally soft-spoken Patterson earned the new champ's wrath by refusing to call Ali by his Muslim name. At the weigh-in, Ali's glare made it clear that he intended Patterson to pay for the disrespect.

In cruelly efficient performance, Ali punished Patterson — who was hobbled by a painful back injury — seemingly toying with the former champ throughout the bout, hitting him at will and calling, "What's my name?" before finally winning on a 12th-round TKO.

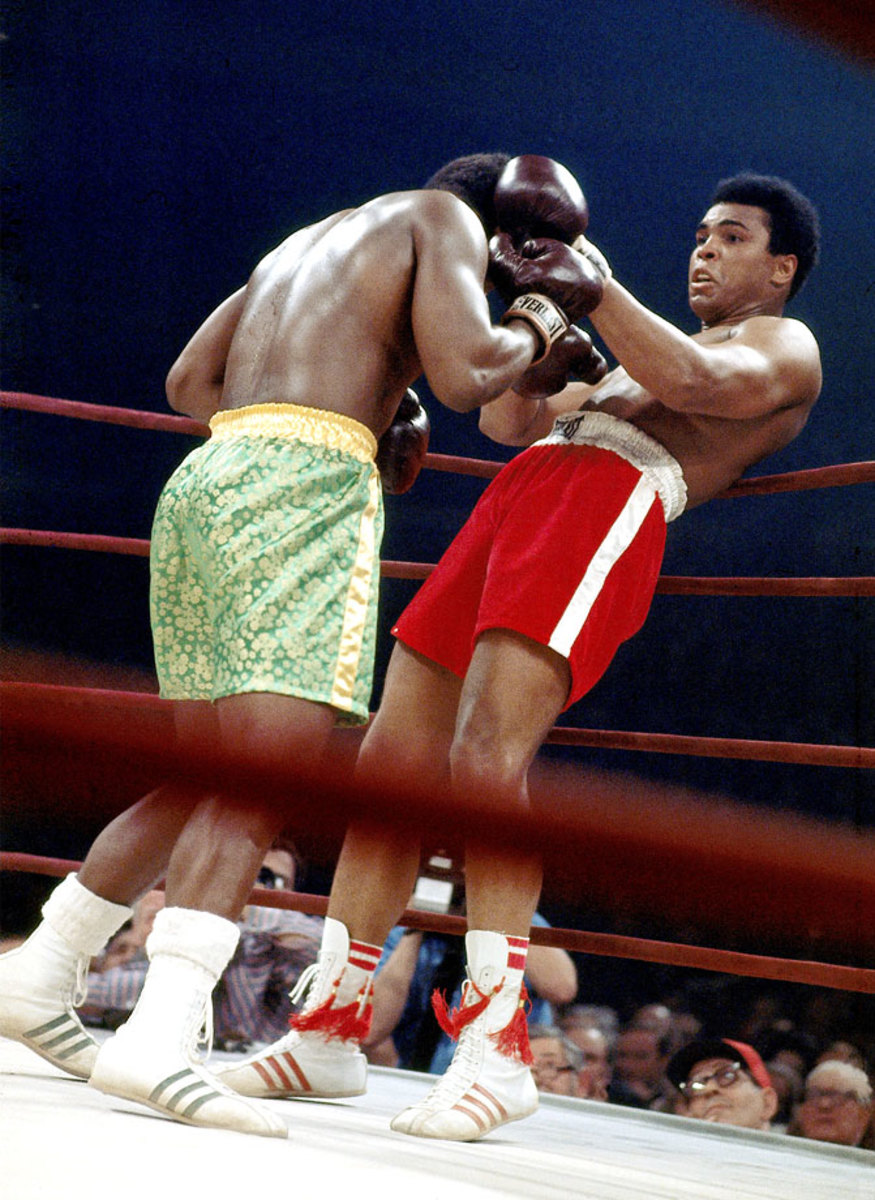

Capping off a five-fight campaign in 1966, Ali faced Cleveland Williams in the Houston Astrodome on Nov. 14. Known as the Big Cat, the heavily-muscled Williams was a power puncher who had racked up 51 knockouts in 71 fights. But he was also 33, barely recovered from a gunshot wound sustained the year before, and up against a young champion very much in his prime. Ali wasted little time in unleashing a withering attack.

Float and sting: In a display of speed and combination punching unmatched in heavyweight history, Ali overwhelmed Williams from the start. The challenger, here down for the third time in round 2, would be saved by the bell before referee Harry Kessler could count him out, but it would only postpone the inevitable.

Ali dropped Williams again early in the third round, and Kessler waved the mismatch over at 1:08 of the third.

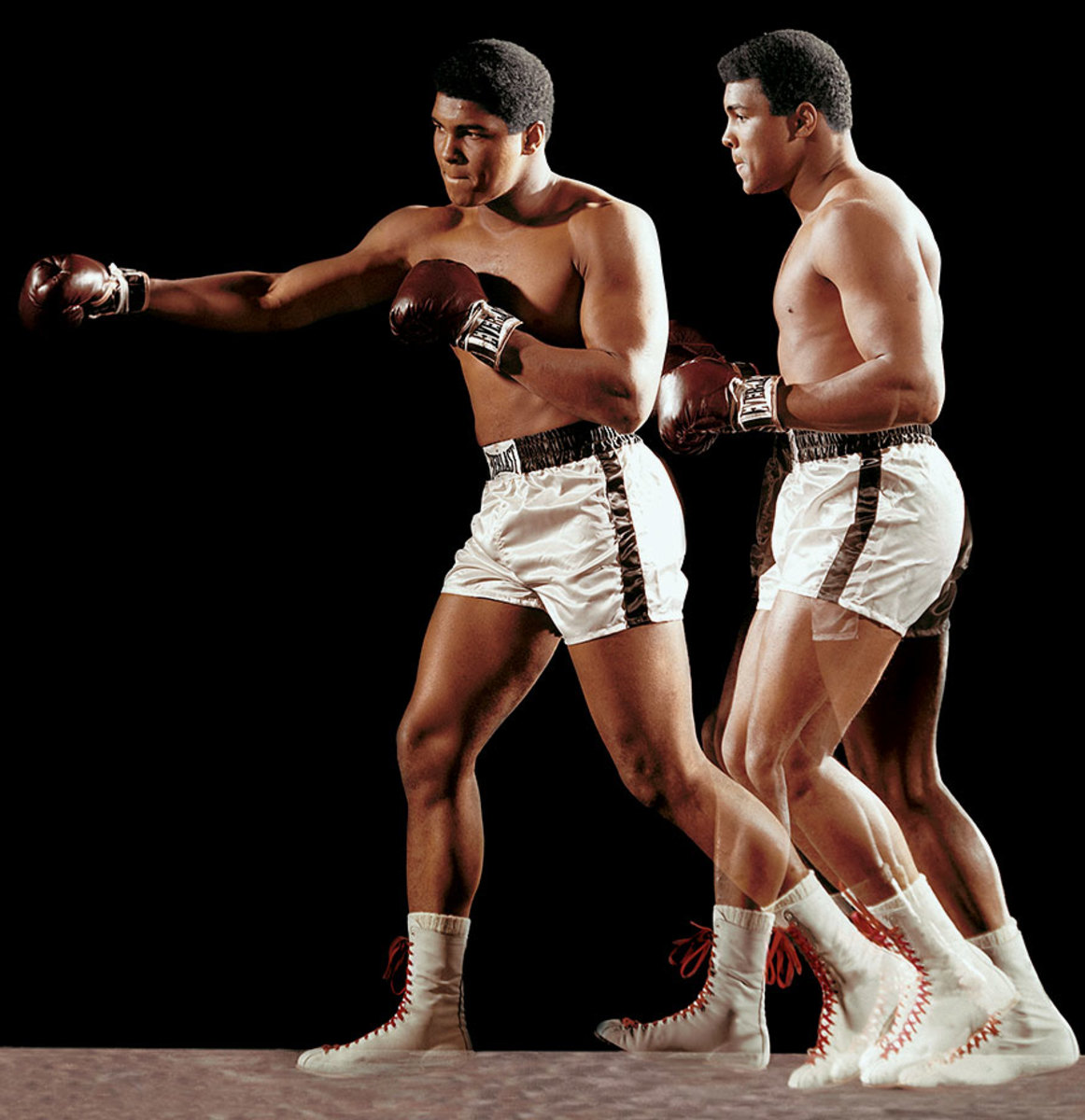

In a multiple-exposure portrait, Ali demonstrates his signature double-clutch shuffle during a photo shoot in December 1966.

Ali sits in the locker room before his February 1967 fight against Ernie Terrell. Like Patterson before him, Terrell refused to call the champion by his Muslim name. Also like Patterson, he paid a stiff price, as Ali punished Terrell for 15 ugly rounds before winning by unanimous decision.

Outside the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in Houston in April 1967, Ali spoke to the press about his refusal to be inducted into military service. Among those on hand was ABC's Howard Cosell, who would be a staunch supporter of the fighter's stance. The decision cost Ali his boxing license and his heavyweight title, and he was sentenced to five years in prison but remained free pending an appeal.

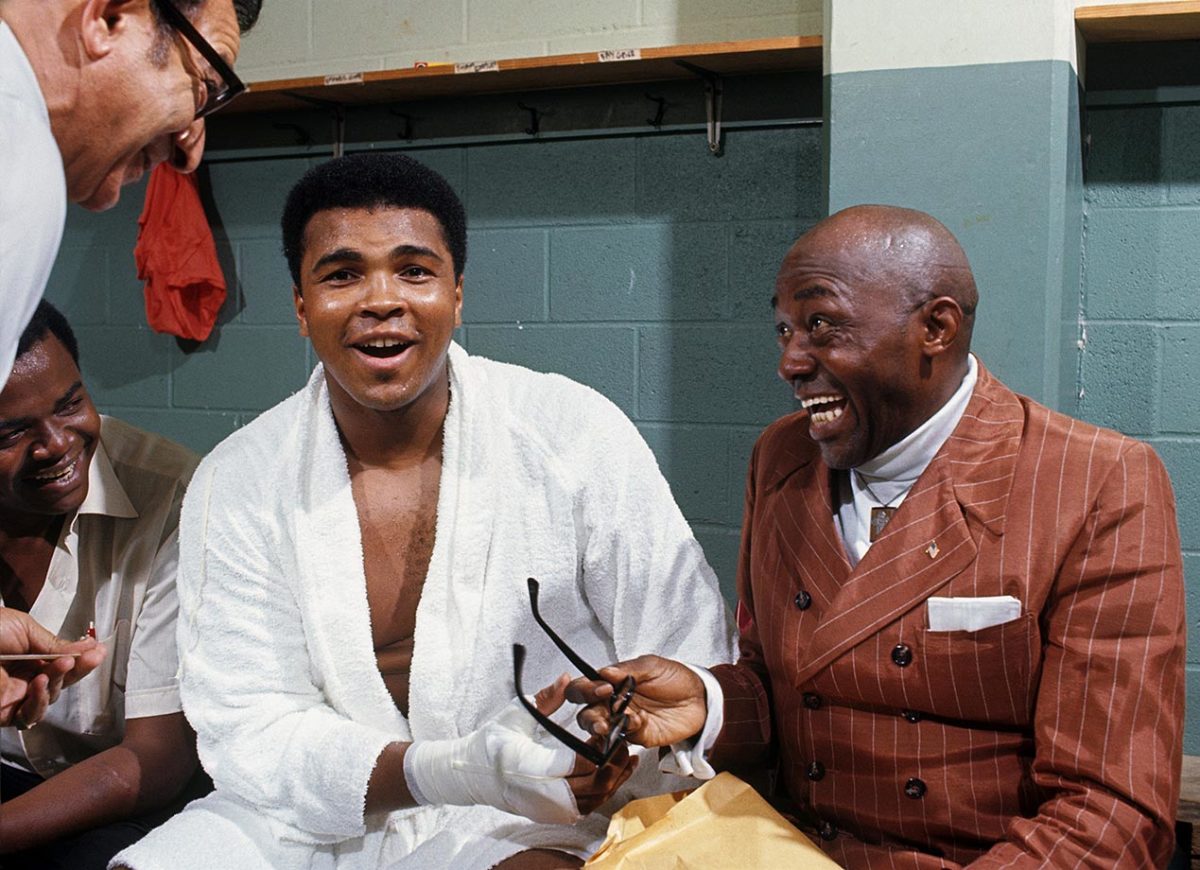

In professional exile for three and a half years because of his draft case, Ali sought to return to boxing in 1970. He began with a night of exhibition bouts at Morehouse College in Atlanta, where before going into the ring, he shared a locker room laugh with actor and comedian Lincoln Perry (right), better known by his stage name of Stepin Fetchit. The friendship between the two black icons would later be examined in an acclaimed play by Will Power, Fetch Clay, Make Man.

After the Atlanta Athletic Commission at last granted Ali a license, the deposed champion went back into serious training. He was, as ever, in the capable hands of trainer Angelo Dundee, here wrapping boxing's most famous fists at the 5th Street Gym in Miami in October 1970.

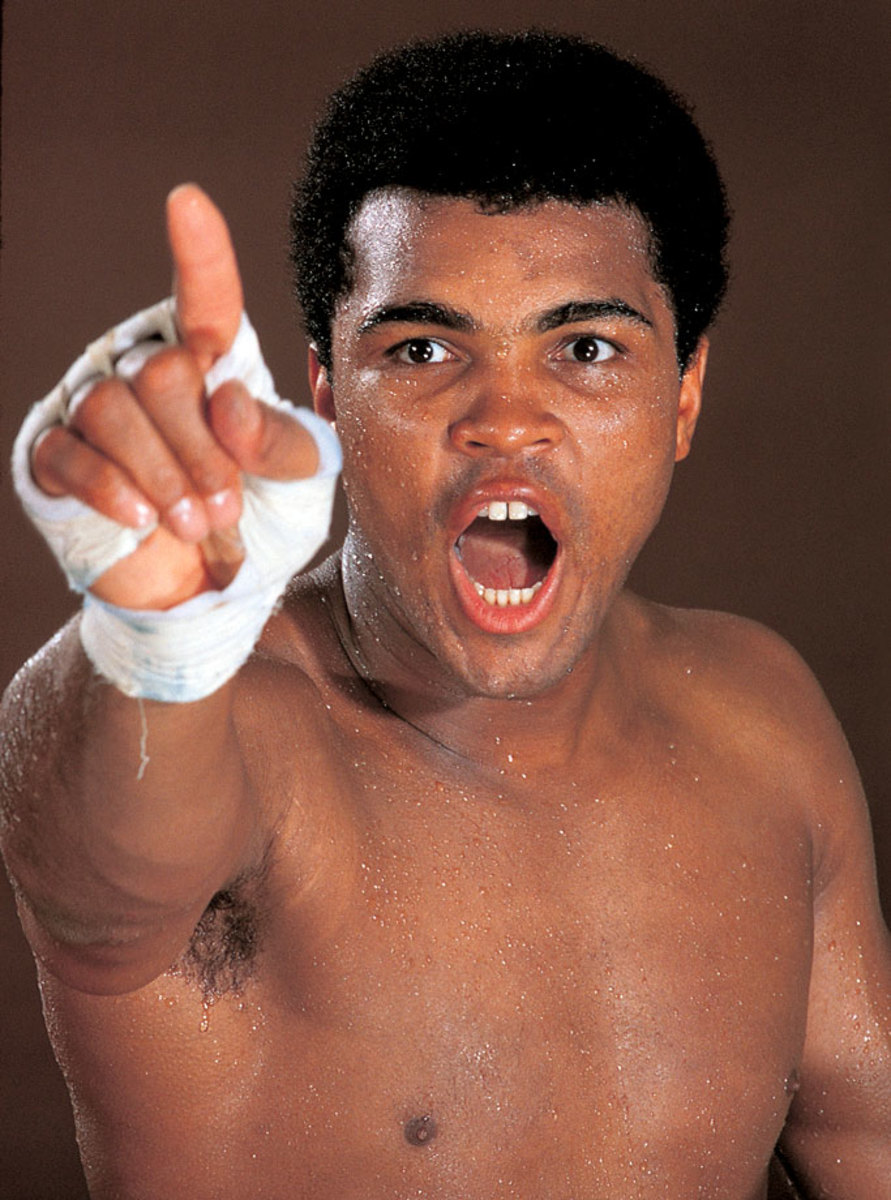

With his return to the ring scheduled for Oct. 26, 1970 in Atlanta, against dangerous contender Jerry Quarry, Ali made it clear to all who would listen that he was on a mission to reclaim the title that had been stripped of him.

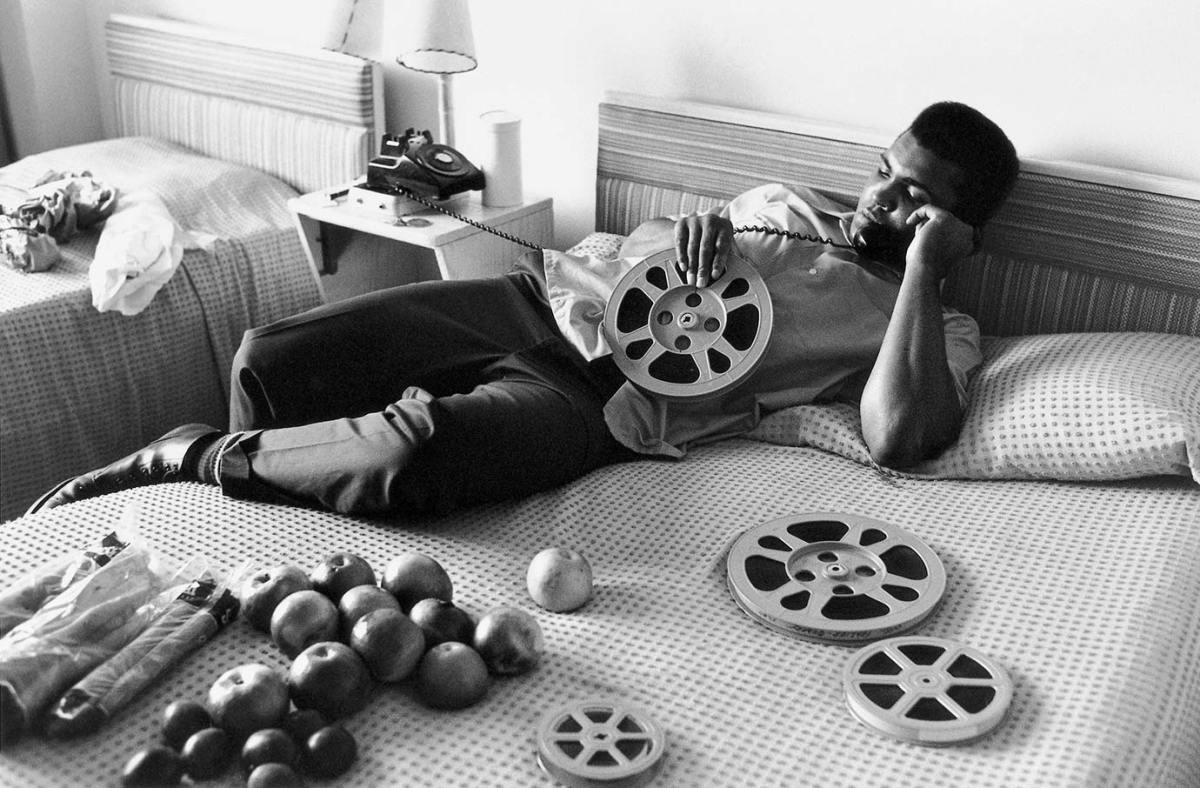

Reel to spiel: For the ever-loquacious Ali, even a rare moment of down time — like this afternoon in 1970 in a Miami hotel room — was a chance to do some talking.

Despite Ali's long layoff, his comeback campaign would include no easy tune-up bouts. He stopped Quarry in three rounds on Oct. 26, 1970, then, just six weeks later — an unthinkably short interlude by today's standards — took on Argentine contender Oscar Bonavena in Madison Square Garden. Here, Ali fires a right at the rugged and awkward Bonavena, who took the fight to the former champion all night.

After a long, often sloppy bout, Ali — here being held back by referee Mark Conn — produced one of the most dramatic finishes of his career, dropping Bonavena three times in the 15th and final round to automatically end the fight. The win cleared the way for a showdown with Joe Frazier, the man who had taken the heavyweight title in Ali's absence.

On the night of March 8, 1971, the eyes of the world were on a square patch of white canvas in the center of Madison Square Garden. There, Ali and Joe Frazier met in what was billed at the time simply as The Fight, but has come to be known, justifiably, as the Fight of the Century. For 15 rounds the two undefeated heavyweights battled at a furious pace, with each man sustaining tremendous punishment. In the end Frazier prevailed, dropping Ali in the final round with a tremendous left hook to seal a unanimous decision and hand The Greatest his first loss in 32 professional fights.

Ali poses with the fight poster for his upcoming fight against Jimmy Ellis during a photo shoot in July 1971. Ellis was an old friend of Ali's — both were trained by Angelo Dundee — and knew his fighting style well from many rounds of sparring.

For those sportswriters lucky enough to cover Ali on a regular basis, each day brought surprises and, more often than not, plenty of laughs. of Trainer Drew Bundini Brown helps Ali train for his fight against Ellis. Ali won the bout by technical knockout in the 12th round to claim the vacant NABF heavyweight title.

The man in the mirror stares back as Ali examines himself while training for a fight in 1972. He won all six of his fights that year.

The Louisville Lip stands next to George Foreman before Ali's fight versus Jerry Quarry in June 1972. Ali won by technical knockout in the seventh round. Foreman at the time was 36-0. Ali would not get his shot against Foreman for more than two years.

Ali throws a left hook at Bob Foster in their 1972 fight at Stateline, Nev. Although Ali knocked Foster out, Foster did leave his mark: a cut above Ali's left eye, his first as a professional.

Foster lies on the canvas after getting knocked down by Ali. Ali knocked Foster down four times in the fifth round and twice more in the seventh round before he was finally counted out after Ali knocked him down again in the eighth round.

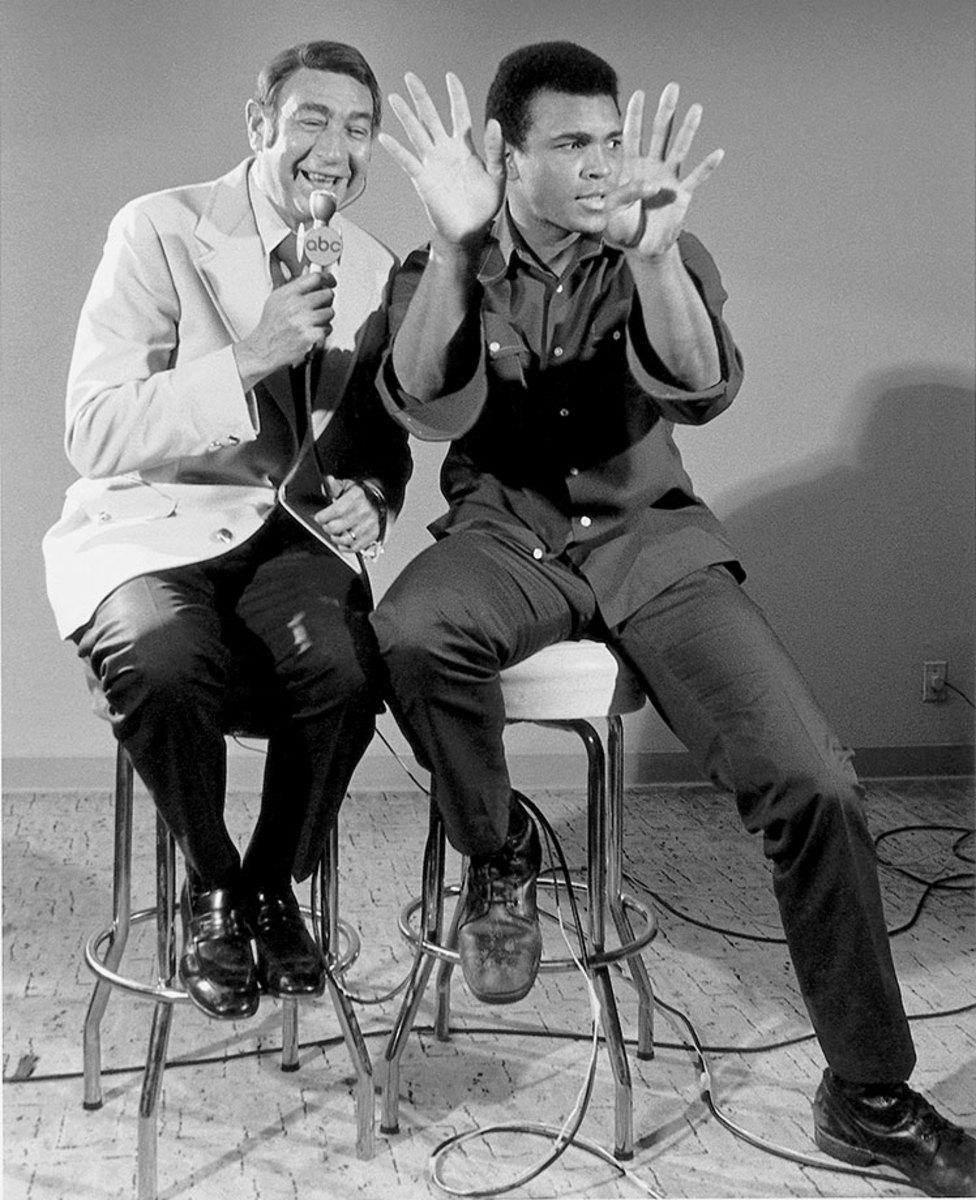

Ali sits with sportscaster Howard Cosell before his fight with Joe Bugner in February 1973. Although unable to knock Bugner out, Ali won comfortably by unanimous decision.

Ali hits a speed bag while warming up for his bout with Bugner in Las Vegas. Ali prepared ferociously for the fight, training 67 rounds the week leading up to the fight, including six rounds the day before the fight.

In a lighter pre-fight moment, Ali poses for a portrait wearing a hat in his dressing room before the match with Bugner.

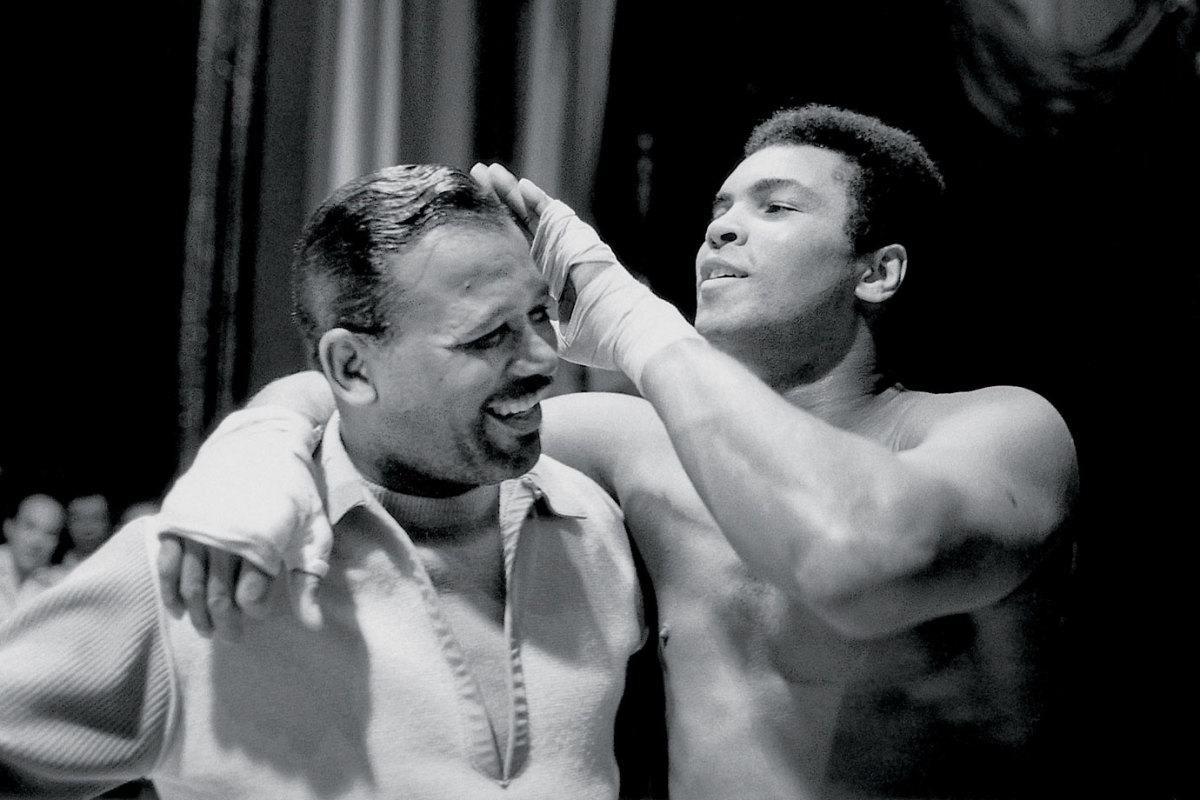

Ali plays with Sugar Ray Robinson's hair in the locker room before his bout with Bugner. The former welterweight and middleweight champion was Ali's childhood idol.

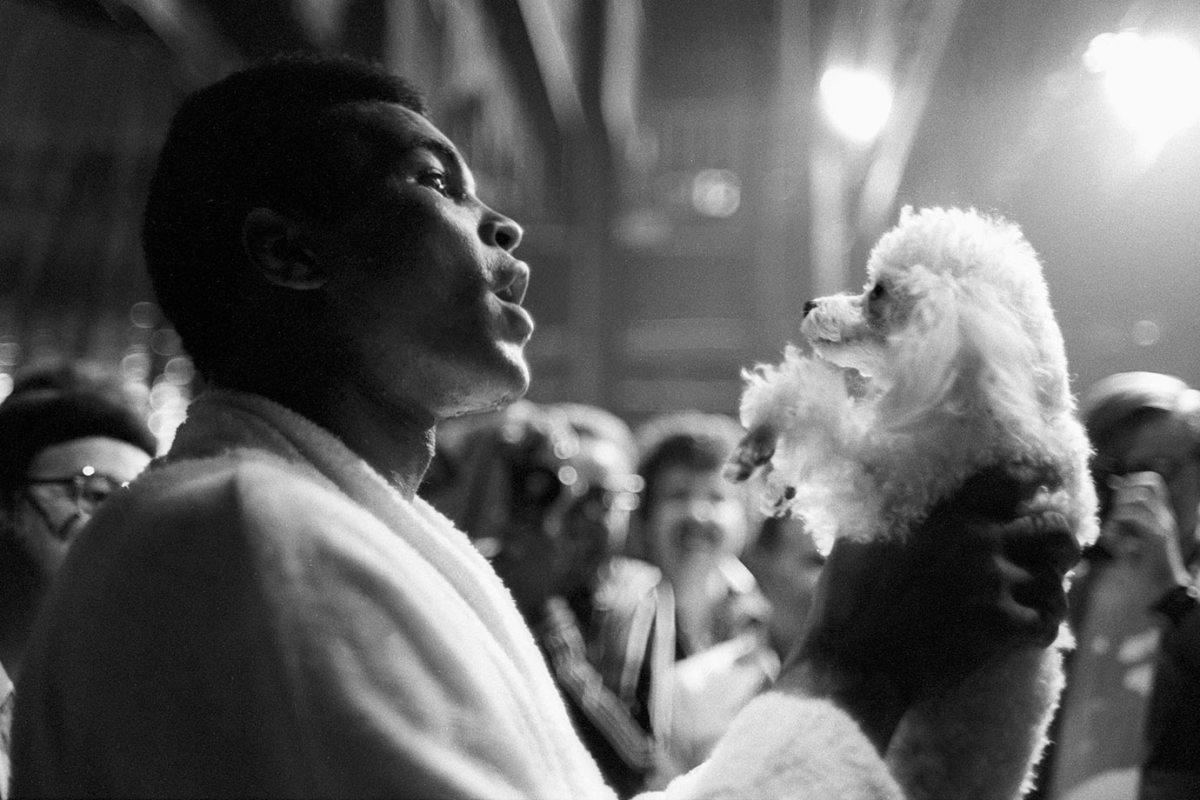

Before the fight with Bugner, Muhammad Ali enjoys a relaxed moment with a poodle at Caesars Palace Hotel. He won the fight with Bugner by unanimous decision.

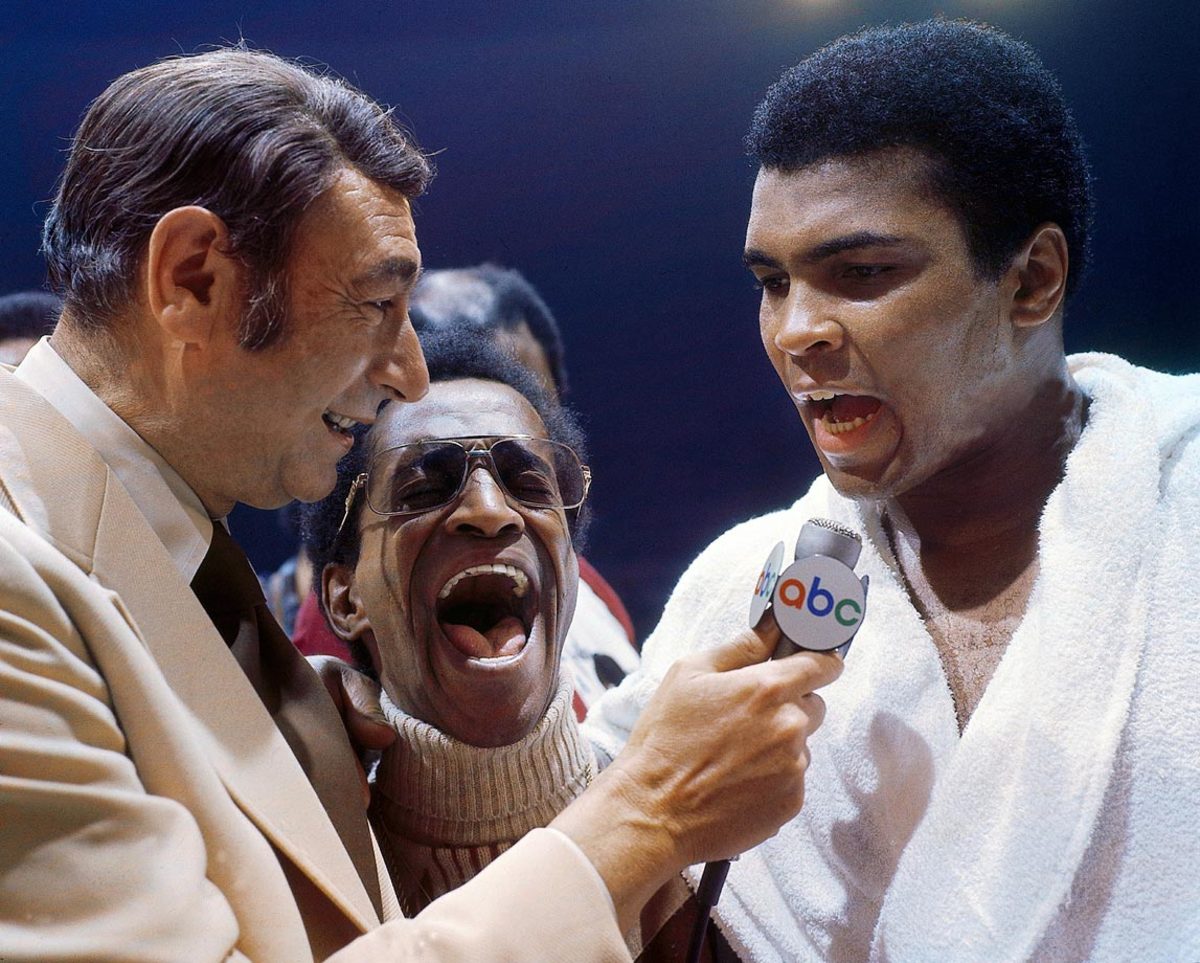

Howard Cosell interviews Ali, with entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. in the middle, after his victory over Joe Bugner by unanimous decision in. Although the fight was never in jeopardy of getting away from him, Ali praised Bugner's legs and said he could be a champion in a few years.

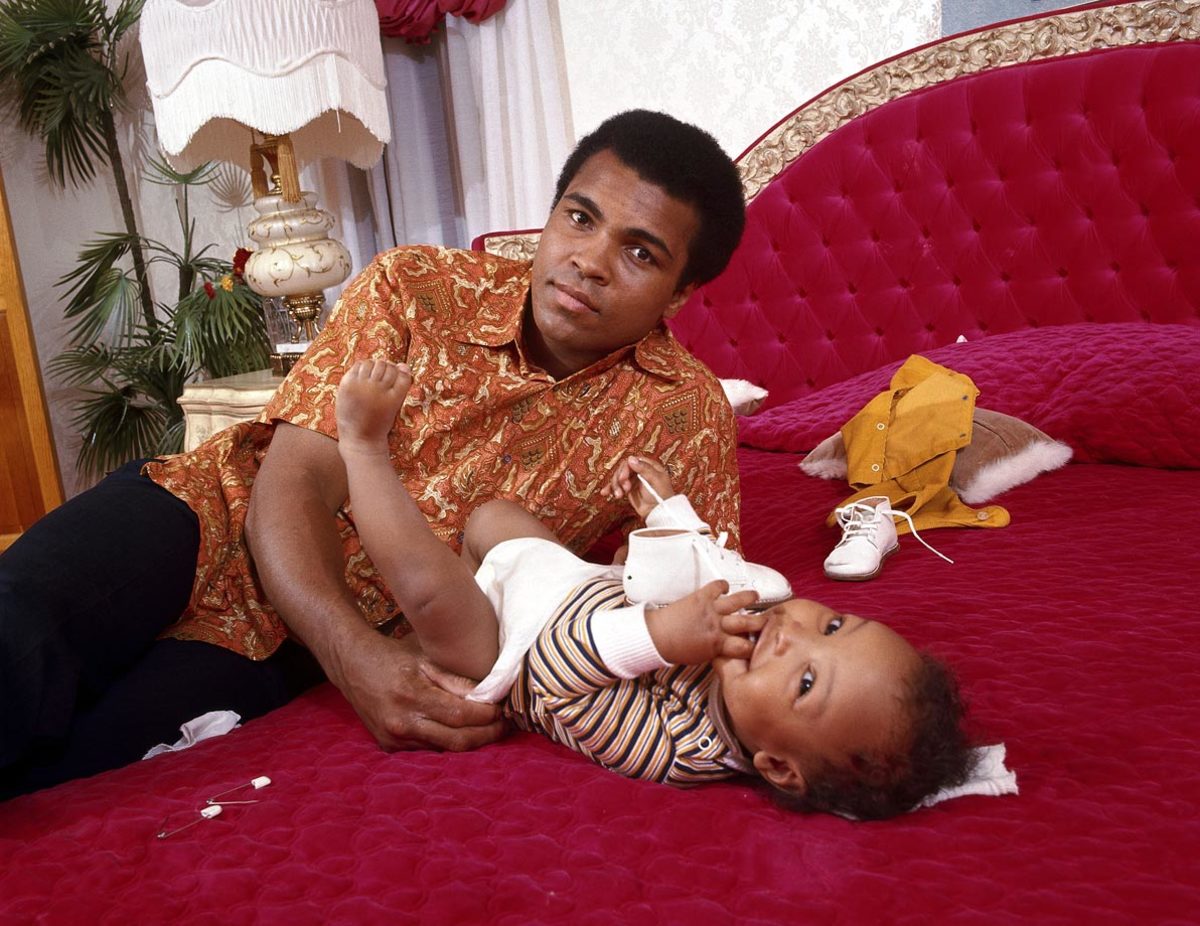

Ali changes the diaper of his son in his bedroom during a photo shoot at the family's home in April 1973. Ali had suffered a broken jaw less than a month earlier in his fight against Ken Norton.

In the wake of his split decision loss to Norton, Ali plays with his son in his bedroom at home in Cherry Hill, N.J.

Ali kisses his daughter Jamillah outside of their home following the loss to Norton, just the second defeat of his career.

The Ali family standing outside their New Jersey home. To the right of Muhammad Ali are his twin daughters, Jamilllah and Rasheda, daughter Maryum and his wife, Khalilah, holding their son Ibn Muhammad Ali Jr.

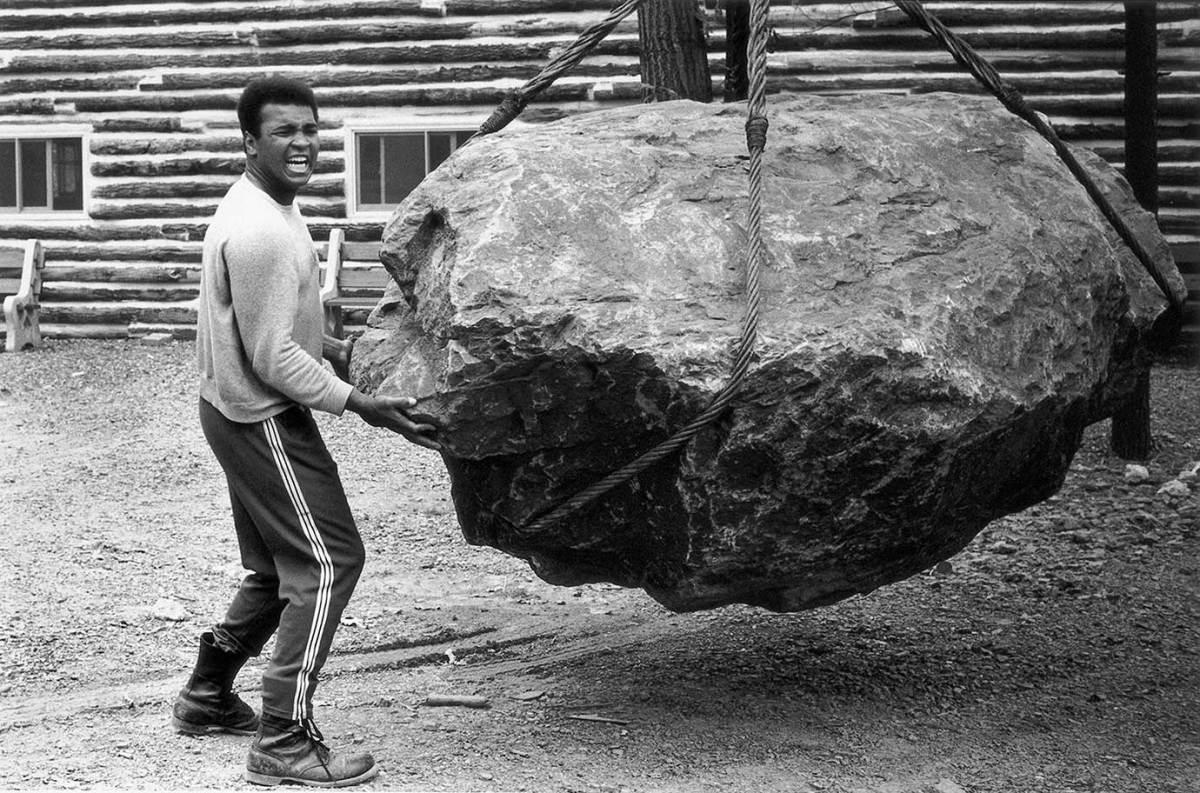

At his training camp cabin, Ali pushes a boulder during a photo shoot in Deer Lake, Penn., in August 1973. Ali was training for his rematch against Ken Norton, who broke his jaw five months earlier.

Ali chops wood at his cabin in Deer Lake. He referred to the training camp as "fighter's heaven" and used it to prepare for fights away from the spotlight.

The fighters weigh in on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson ahead of Ali and Ken Norton's September 1973 fight.

Johnny Carson listens to Ali on the Tonight Show three days before his rematch with Norton. Ali would avenge his earlier loss to Norton, winning a narrow split decision.

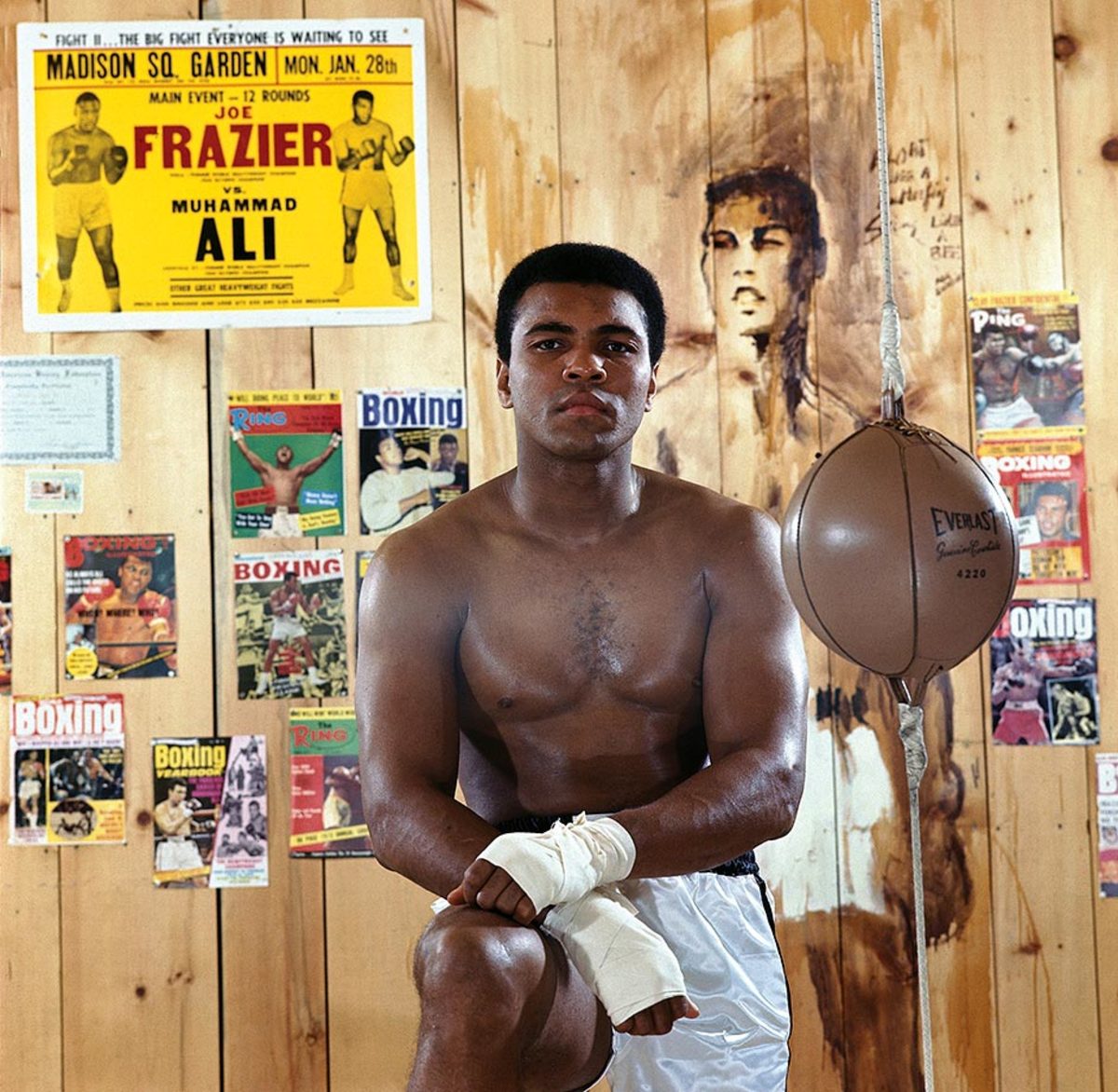

Ali poses in front of posters and magazine covers from throughout his career at his training camp cabin in Deer Lake in 1974.

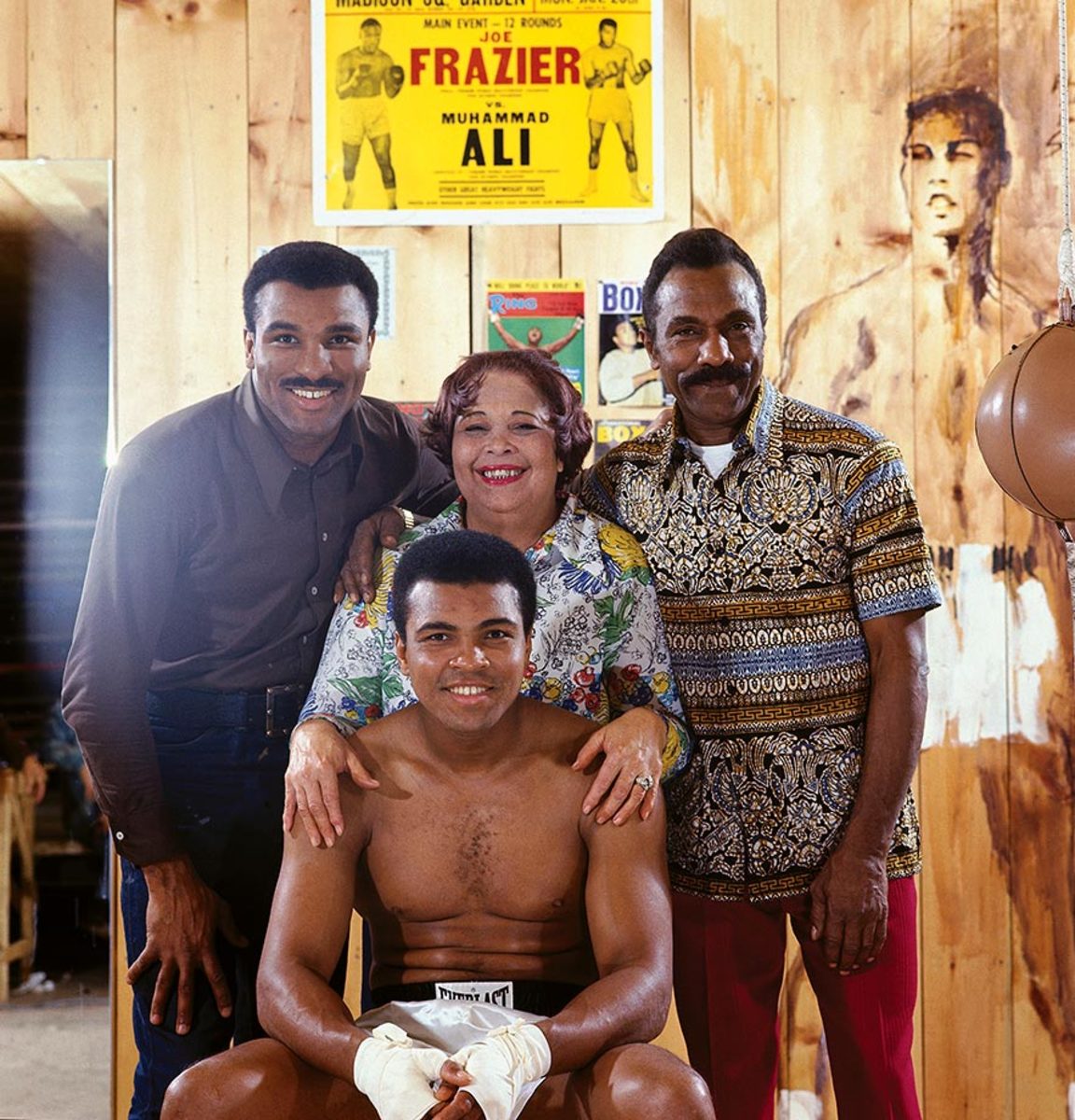

Ali poses with members of his family in front of a poster from his first fight with Joe Frazier. Ali's brother, Rahman Ali; mother, Odessa Clay; and father, Cassius Clay Sr. stand behind the boxer.

Less than three weeks before his rematch with Joe Frazier on Jan. 28, 1974, Ali wraps his hands while wearing a sauna suit at his training camp cabin.

Ali holds a newspaper at his cabin in January 1974. He is pointing to a headline that reads, "Frazier On Ali, I Think He's Crazy." Ali and Frazier fought for the second time later that month with Ali winning by a unanimous decision.

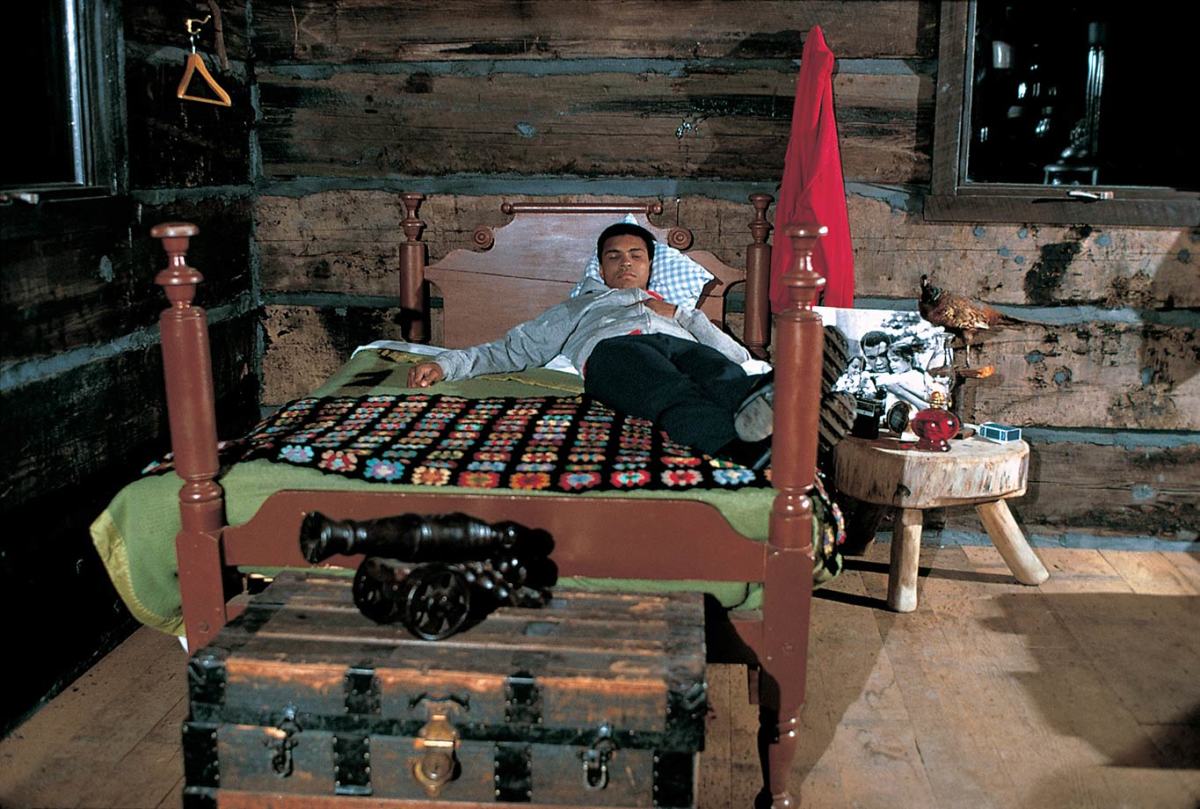

Ali lies on his bed at his cabin during the January 1974 photo shoot.

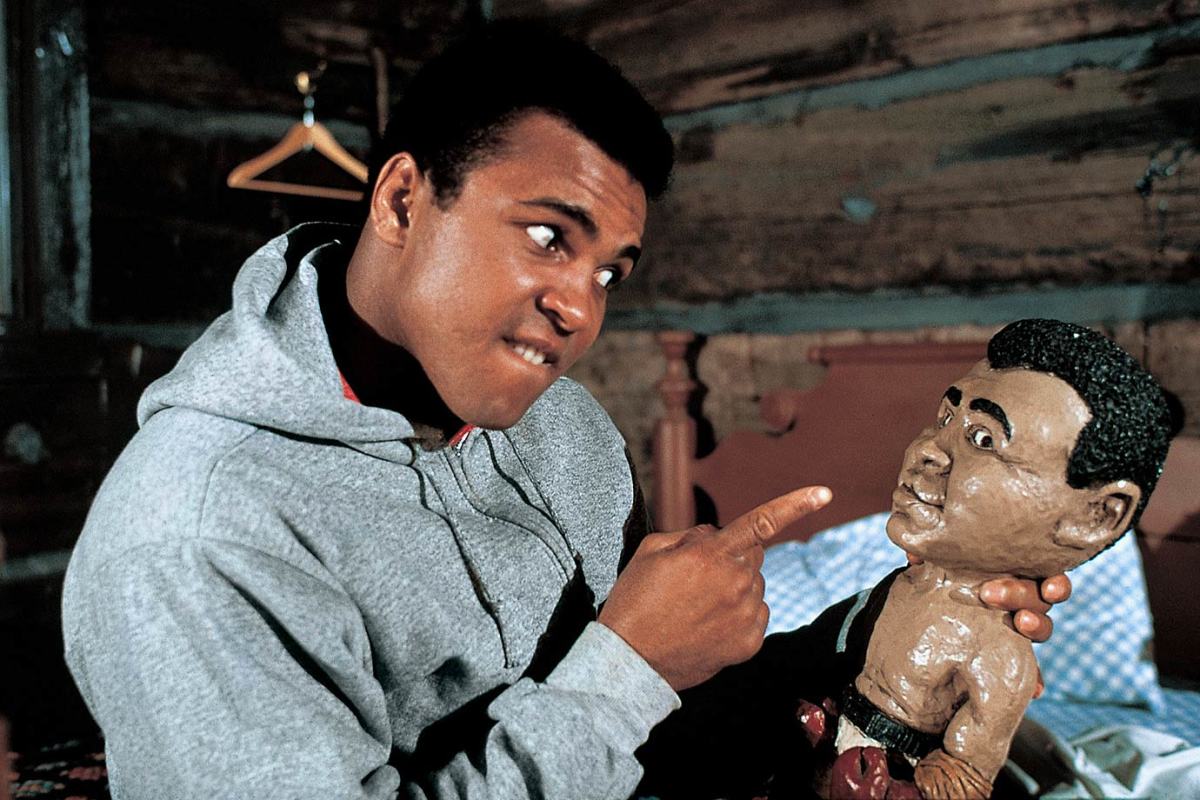

His smaller incarnation stares straight back as Ali plays with a doll of himself during the same 1974 shoot at his training camp cabin.

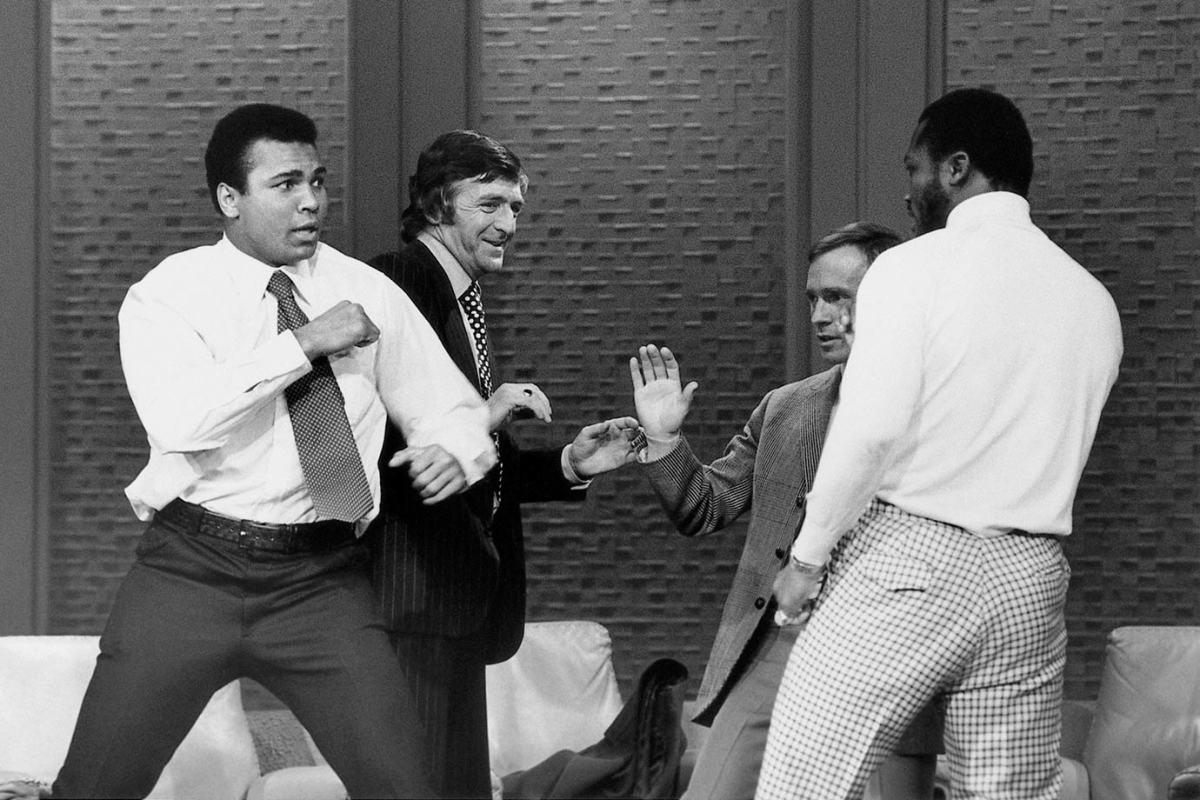

Ali and Joe Frazier fight on the set of The Dick Cavett Show while reviewing their 1971 bout in advance of their 1974 rematch. Ali called Frazier ignorant, to which Frazier took exception. As the studio crew tried to calm Frazier down, Ali held Frazier by the neck, forcing him to sit down and sparking a fight. The television set fight amped up anticipation of their January 1974 bout.

Exploring a different side of the sport, Ali broadcasts the fight between George Foreman and Ken Norton in March 1974. Foreman won the fight by technical knockout in the second round, setting up the showdown with Ali in Zaire.

Ali jumps rope at the Salle de Congres in Kinshasa, Zaire, while training for his heavyweight title fight against George Foreman. Both Ali and Foreman spent most of the summer of 1974 training in Zaire to adjust to the climate.

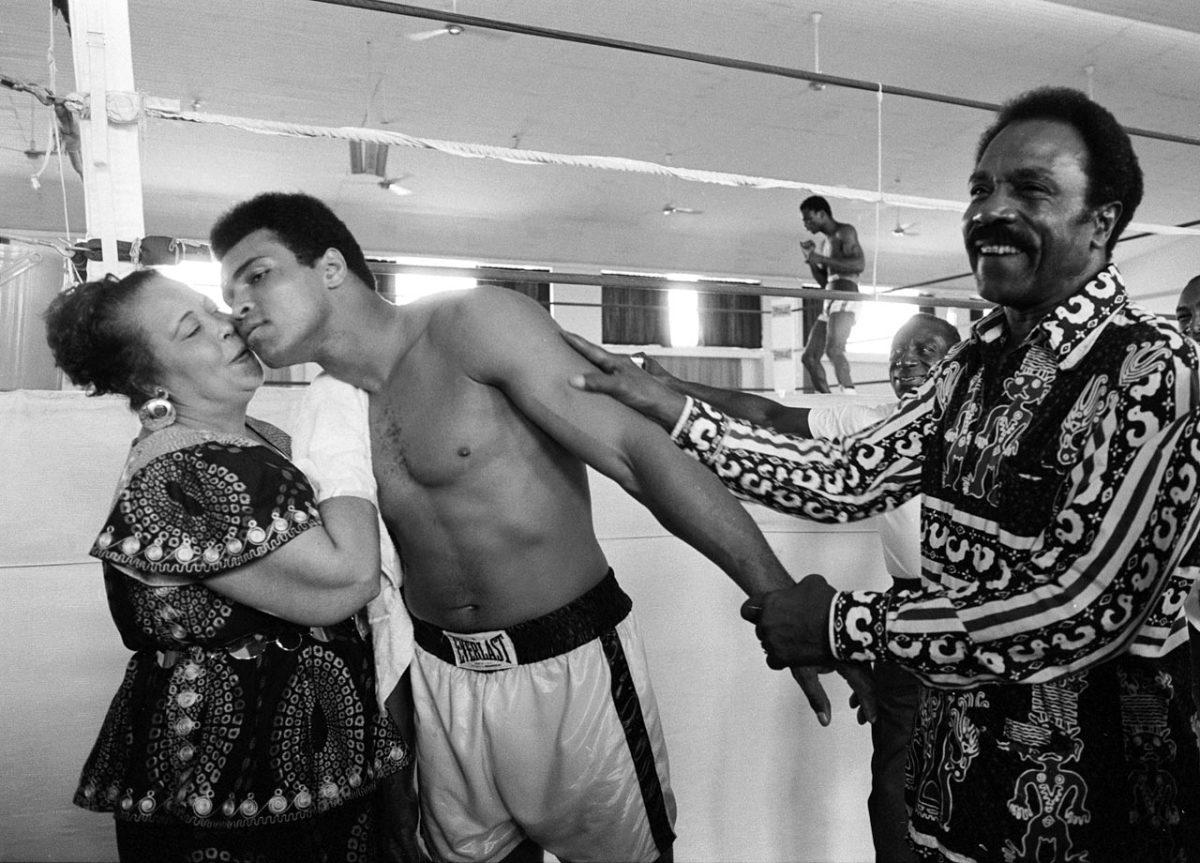

While training before his fight with George Foreman, Ali kisses his mother, Odessa Clay, while his father, Cassius Clay Sr., looks on. Ali's superior strategy and ability to take a punch led him to his upset victory as he absorbed body blows from Foreman before he responded with powerful combinations to Foreman's head.

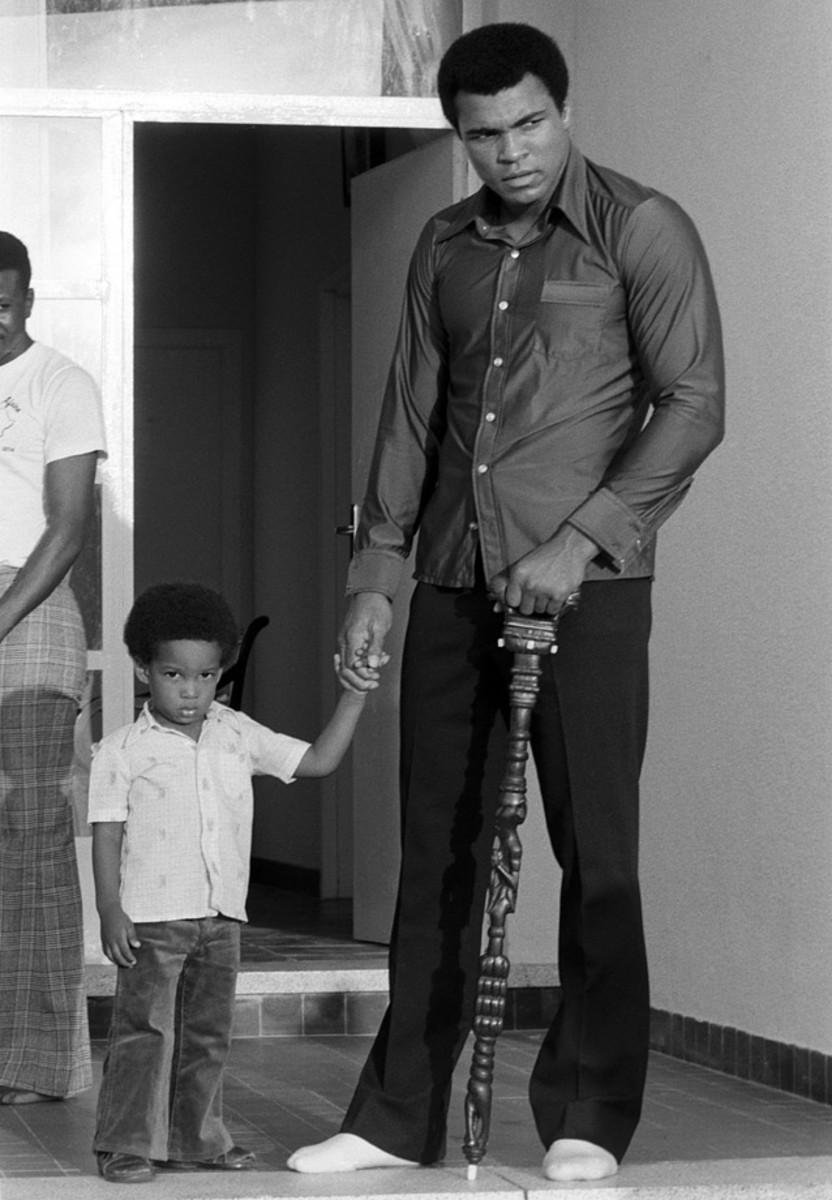

Four days before the fight, Ali holds the hand of his son Ibn in Zaire. Ali successfully courted the favor of the Zaire crowd, prompting chants of "Ali bomaye!" — translated as "Ali, kill him!"

Ali poses in front of the Le Militant statue at the presidential complex that was the site of Ali's January heavyweight title bout with Foreman. The fight was originally set for a month earlier, but Foreman suffered a cut near his eye during training, forcing a delay.

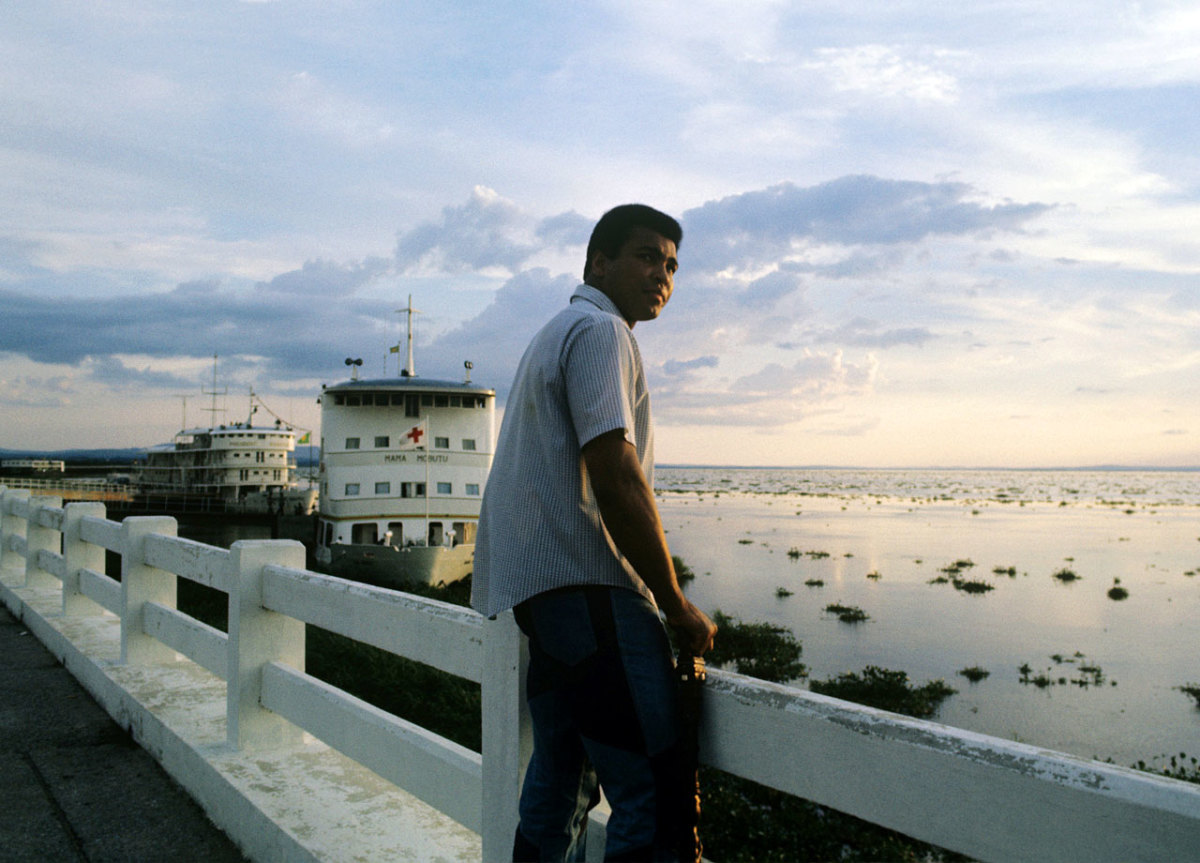

Ali stands against the railing on the River Zaire watching the sunset four days before the Rumble in the Jungle. The fight was sponsored by Zaire to achieve the $5 million purse promoter Don King had promised both Ali and Foreman.

Before employing his famous rope-a-dope strategy against Foreman, Ali makes a face at the camera. Ali allowed Foreman to throw many punches but only into his arms and body, and when Foreman tired himself out from the mostly ineffective punches, Ali took control of the fight.

Ali points before his bout with Foreman. The victory over his favored opponent made him the heavyweight champion of the world for the first time since he was stripped of his titles in 1967.

Ali stares at George Foreman during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali earned his shot at the heavyweight title by defeating Joe Frazier in January 1974, avenging a loss three years earlier.

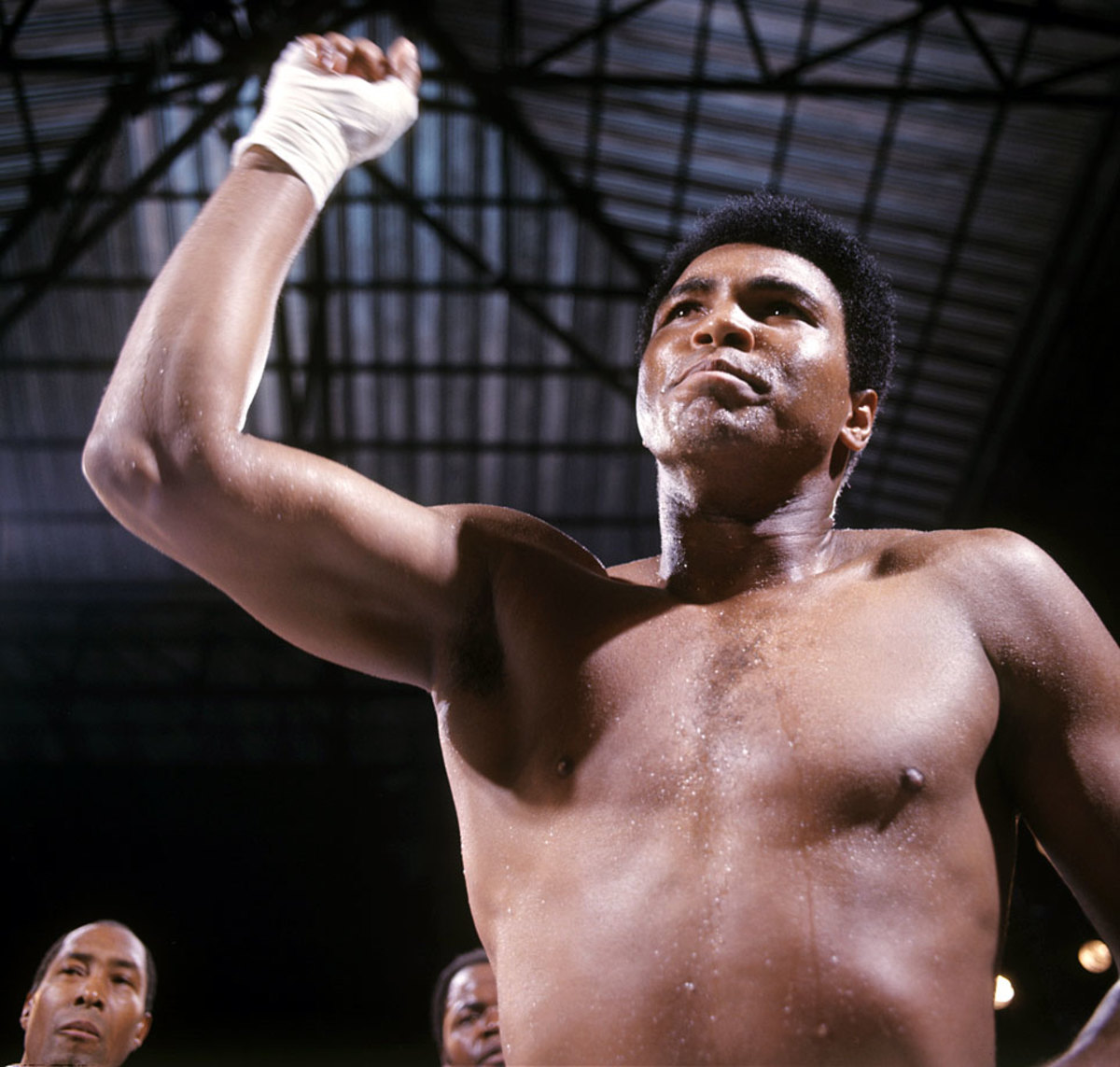

Foreman lies down on the canvas as Ali stands in the background during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali knocked Foreman down with a five-punch combination in the eighth round, and referee Zack Clayton counted him out.

Big George stares at the ceiling as referee Zack Clayton counts him out in the eighth round. The victory made Ali, once again, the heavyweight champion of the world.

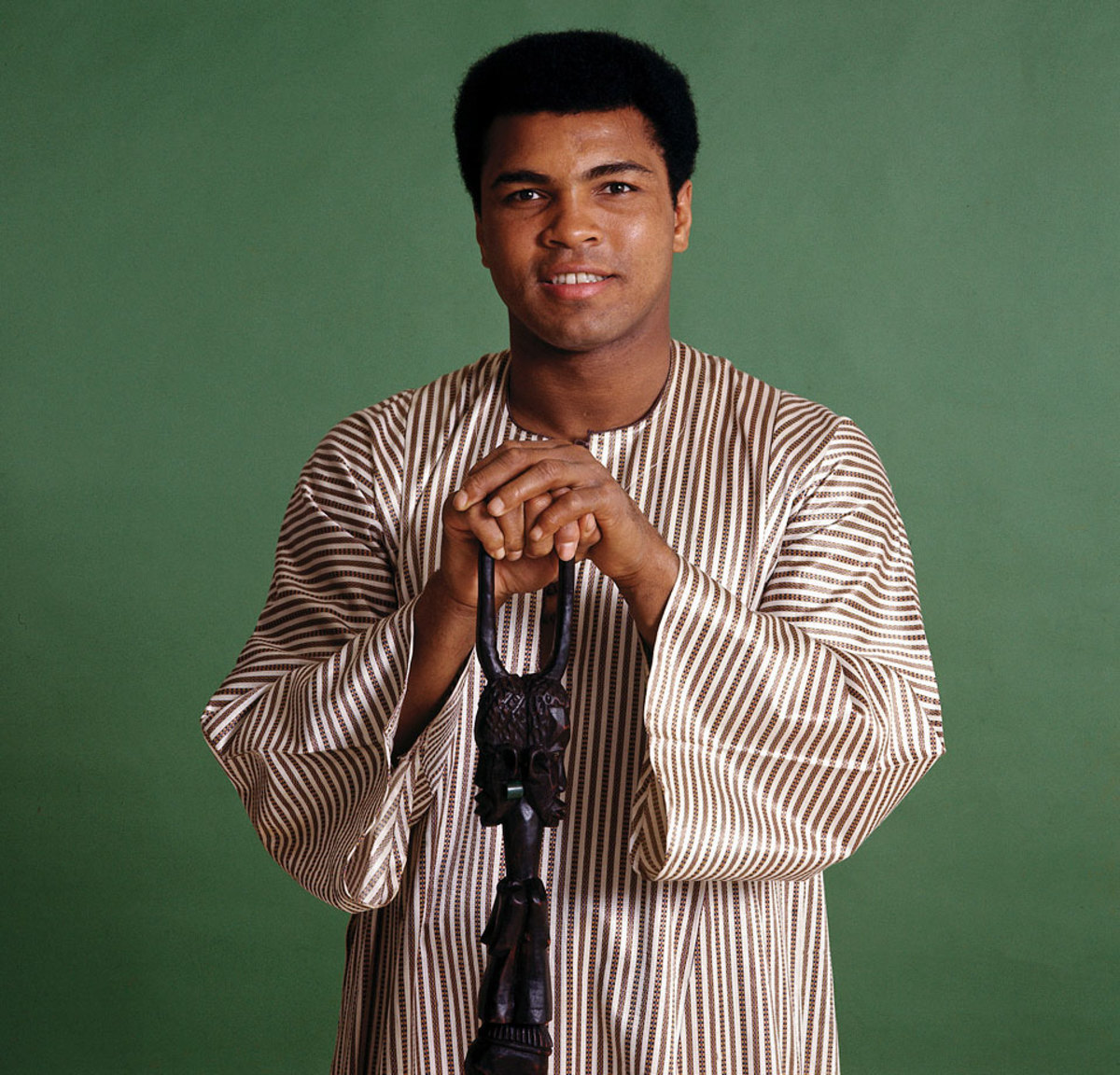

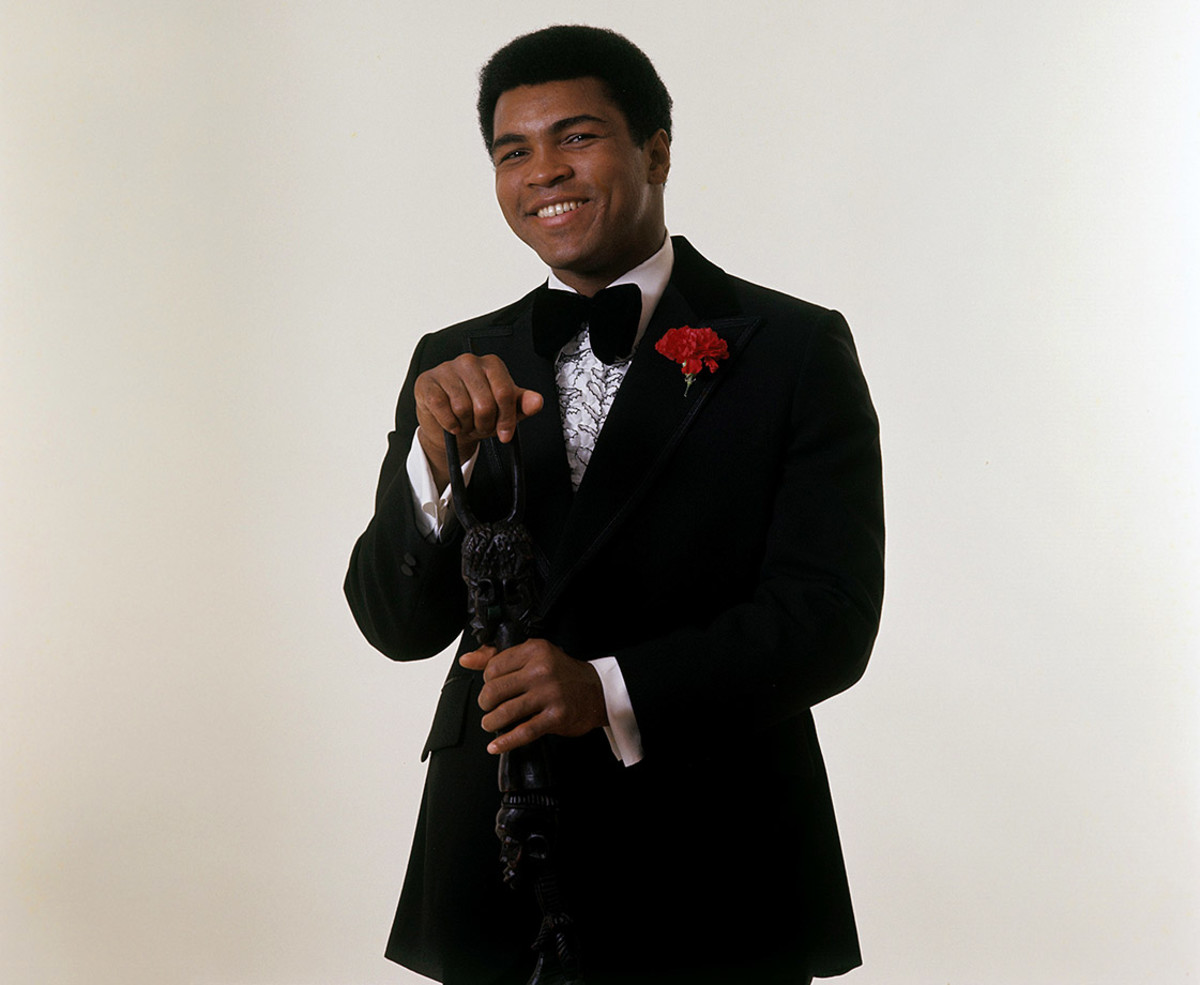

Ali poses for a portrait after being selected as the Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year in 1974. Ali wore a dashiki, a men's garment widely worn in West Africa. He also brought the walking stick given to him by Zaire's president.

This time Ali wears a tuxedo, but keeps the walking stick, during the November photo shoot for Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year.

Ali talks with Howard Cosell outside of the United Nations Headquarters for a segment on the Wide World of Sports. Later that day, Ali held a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

Ali talks with Reverend Jesse Jackson outside of the United Nations Headquarters before a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

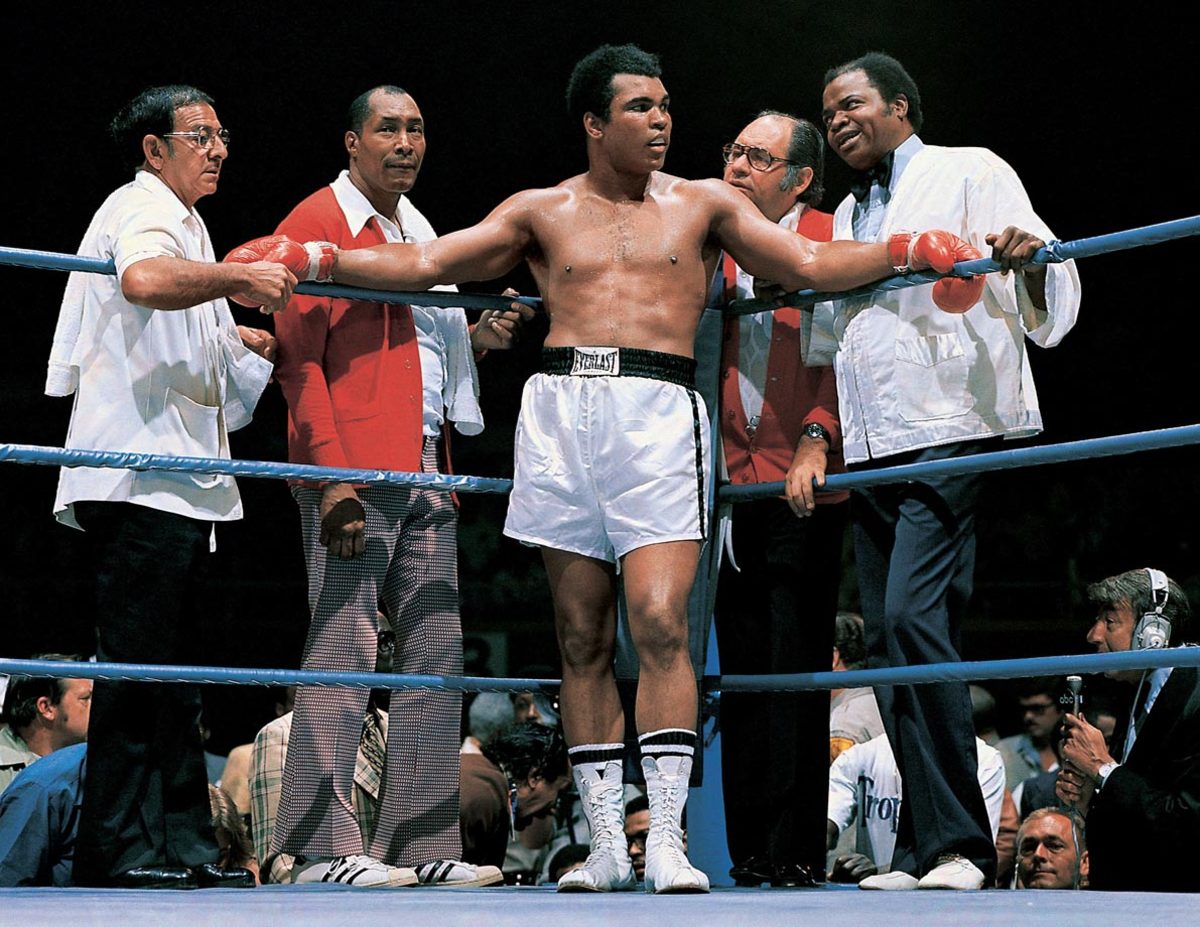

Ali stands with trainer Angelo Dundee, assistant trainer Wali Muhammad, physician Dr. Ferdie Pacheco and assistant trainer Drew Bundini Brown before his bout with Ron Lyle in May 1975. Ali won the fight by technical knockout in the 11th round.

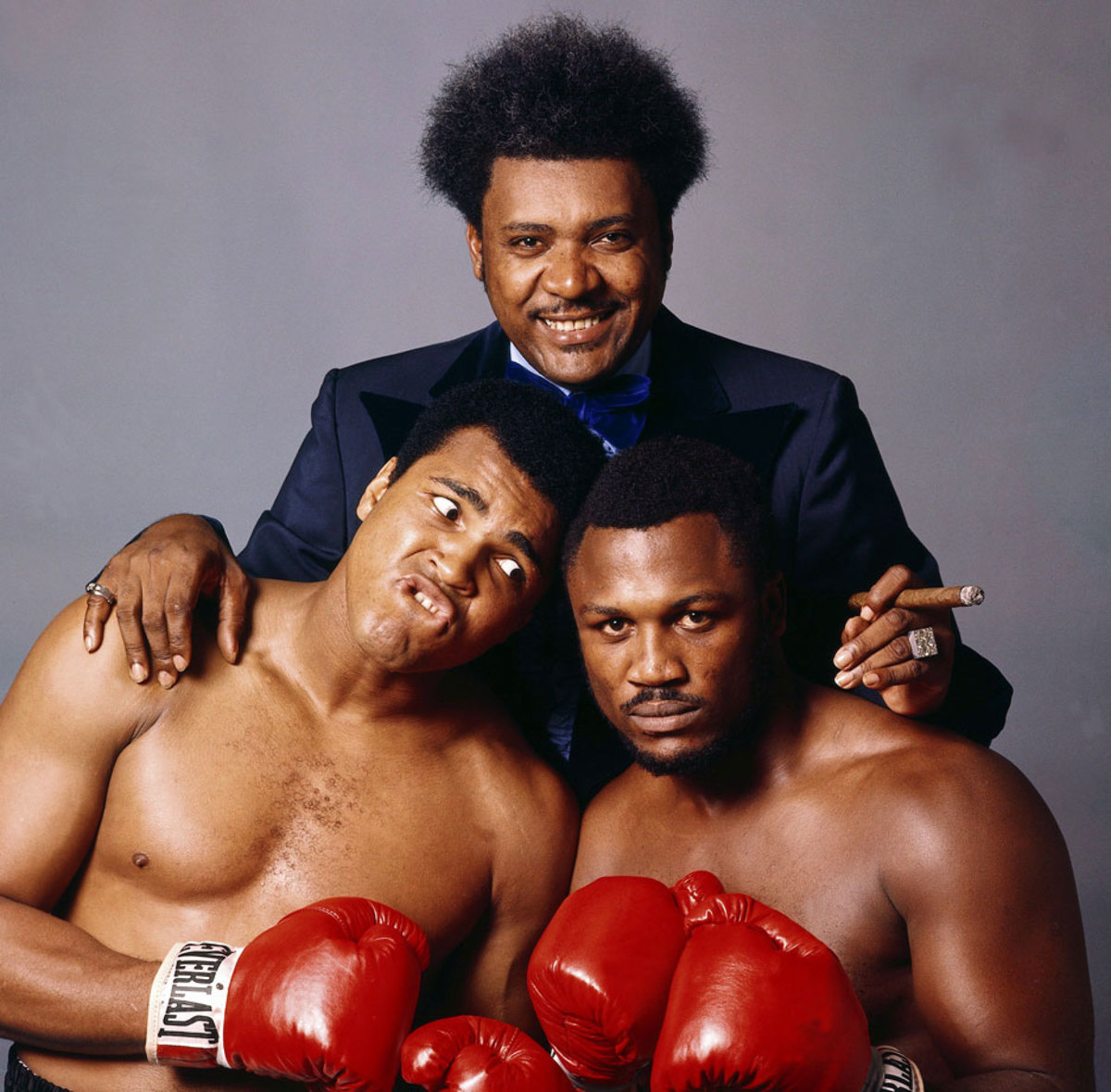

Along with Don King and Joe Frazier, Ali sat for a portrait leading up to the Thrilla in Manila. Ali verbally abused Frazier during the buildup to the fight, telling the media that "it will be a killa and a thrilla and a chilla when I get the gorilla in Manila."

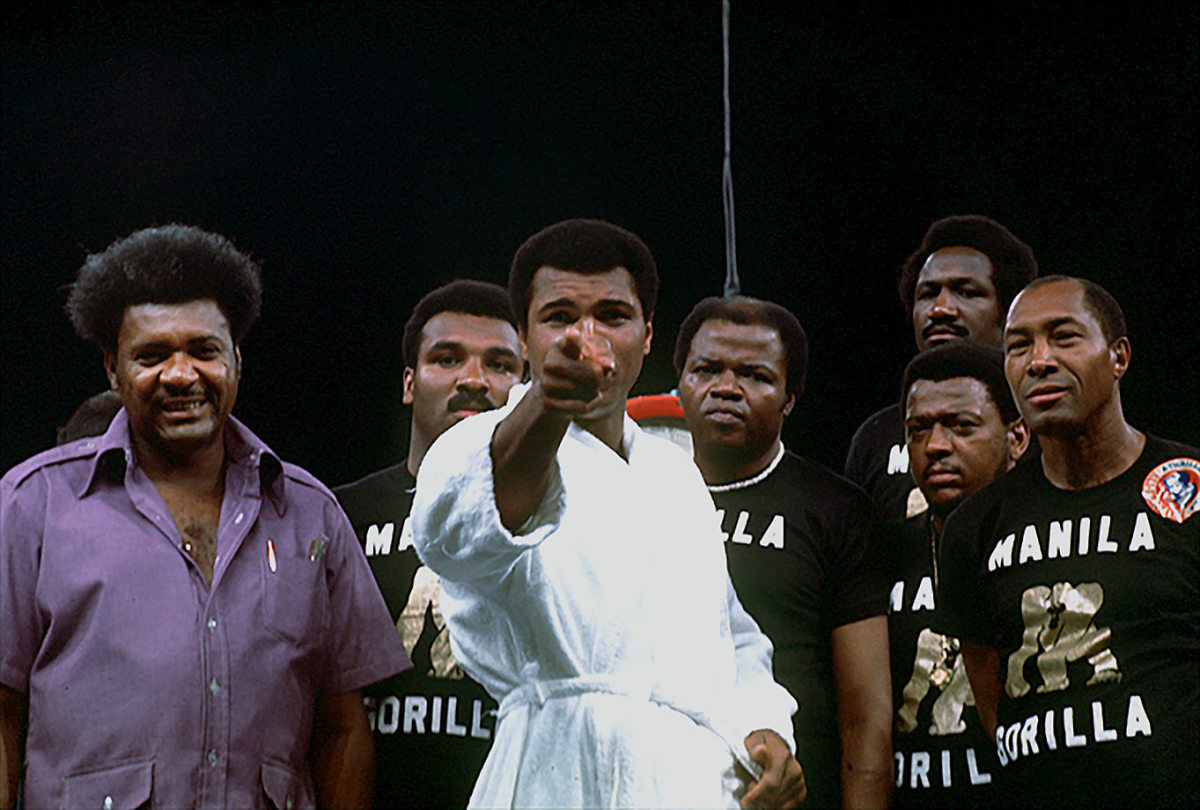

Ali points at the camera with Don King and his training staff behind him before the weigh-in for the Thrilla in Manila in October 1975. Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos offered to sponsor the bout and hold it in Metro Manila to divert attention from the turmoil in the country that had forced the imposition of martial law in 1972.

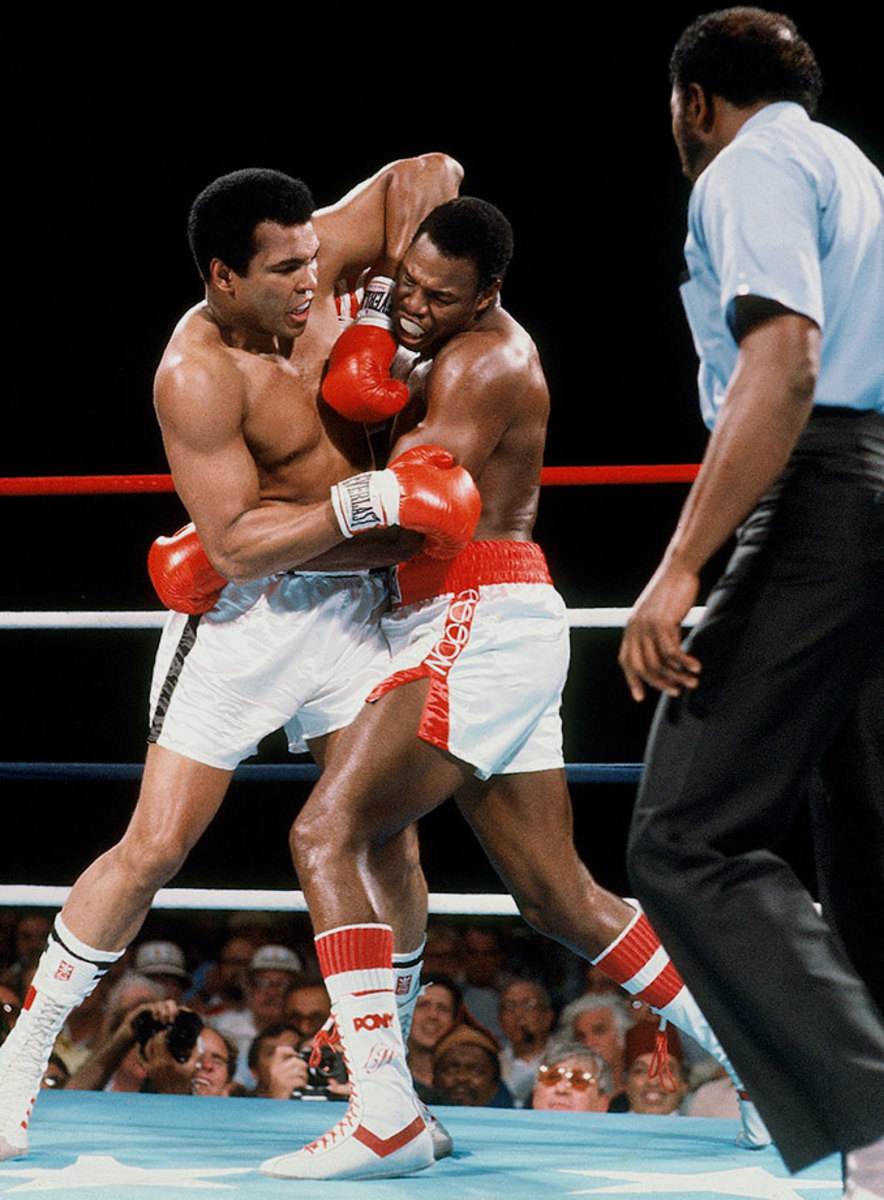

Wrapping up Joe Frazier proved more difficult than Ali expected, having thought Frazier would represent an easy payday and be unable to live up to his billing. The fight turned out to be a brutal affair.

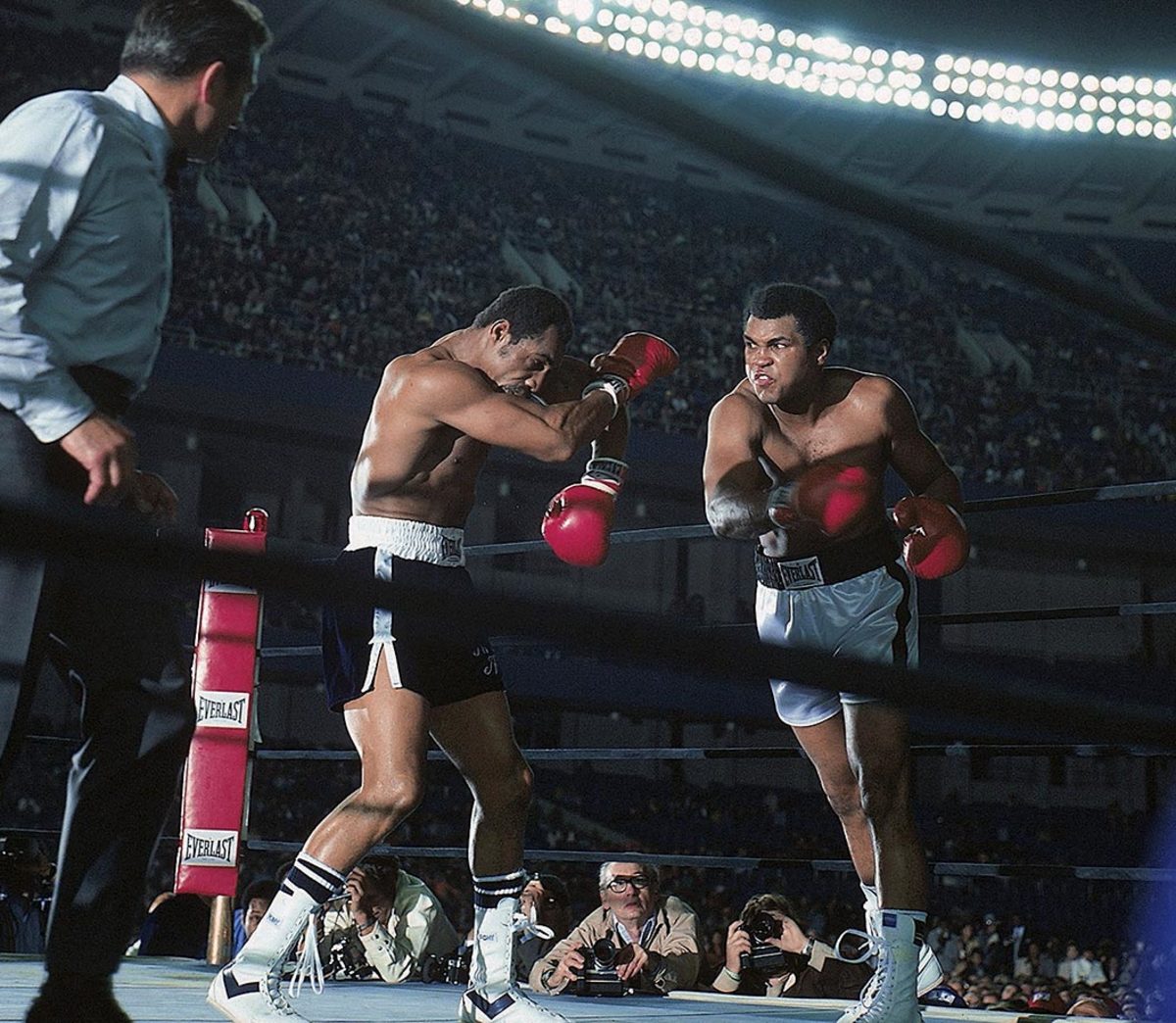

Frazier faces an Ali right hook in their fight in Quezon City, Philippines. The two fighters traded vicious blows during their 14 rounds. "Man, I hit him with punches that'd bring down the walls of a city," Frazier said. Ali withstood the blows to win by TKO in the 15th round.

The third fight between Ali and Frazier, Ali won the bruising battle between the two powerful punching heavyweights when Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, stopped the fight before the 15th round.

A back and forth exchange, Ali controlled the early rounds of the Thrilla in Manila before Frazier fought back with powerful hooks. Ali finished strong, regaining momentum in the later rounds.

Ali speaks to the press after winning the Thrilla in Manila bout with Frazier.

Ali holds a drinking concoction given to him by Dick Gregory, an advocate of a raw fruit and vegetable diet, in 1976.

Before his 1976 fight against Ken Norton at Yankee Stadium, Ali watches a fight on television from his hotel room. A police strike at the time of the fight created a dangerous environment outside the stadium that all but eliminated walk-up sales.

Norton takes a right hook during the heavyweight title fight against Ali. The bout, which Ali won by a unanimous, but controversial, decision, was the last boxing match at Yankee Stadium until 2010.

Ali makes a face during his fight with Earnie Shavers in 1977 at Madison Square Garden. Hurt badly by Shavers in the second round, Ali rebounded and outboxed Shavers throughout to build a lead on points before Shavers came on again in the later rounds. Seemingly exhausted going into the 15th and final round, Ali remained victorious by producing a closing flurry that left Shavers wobbling at the bell and the Garden crowd once again in delirium over his Ali magic.

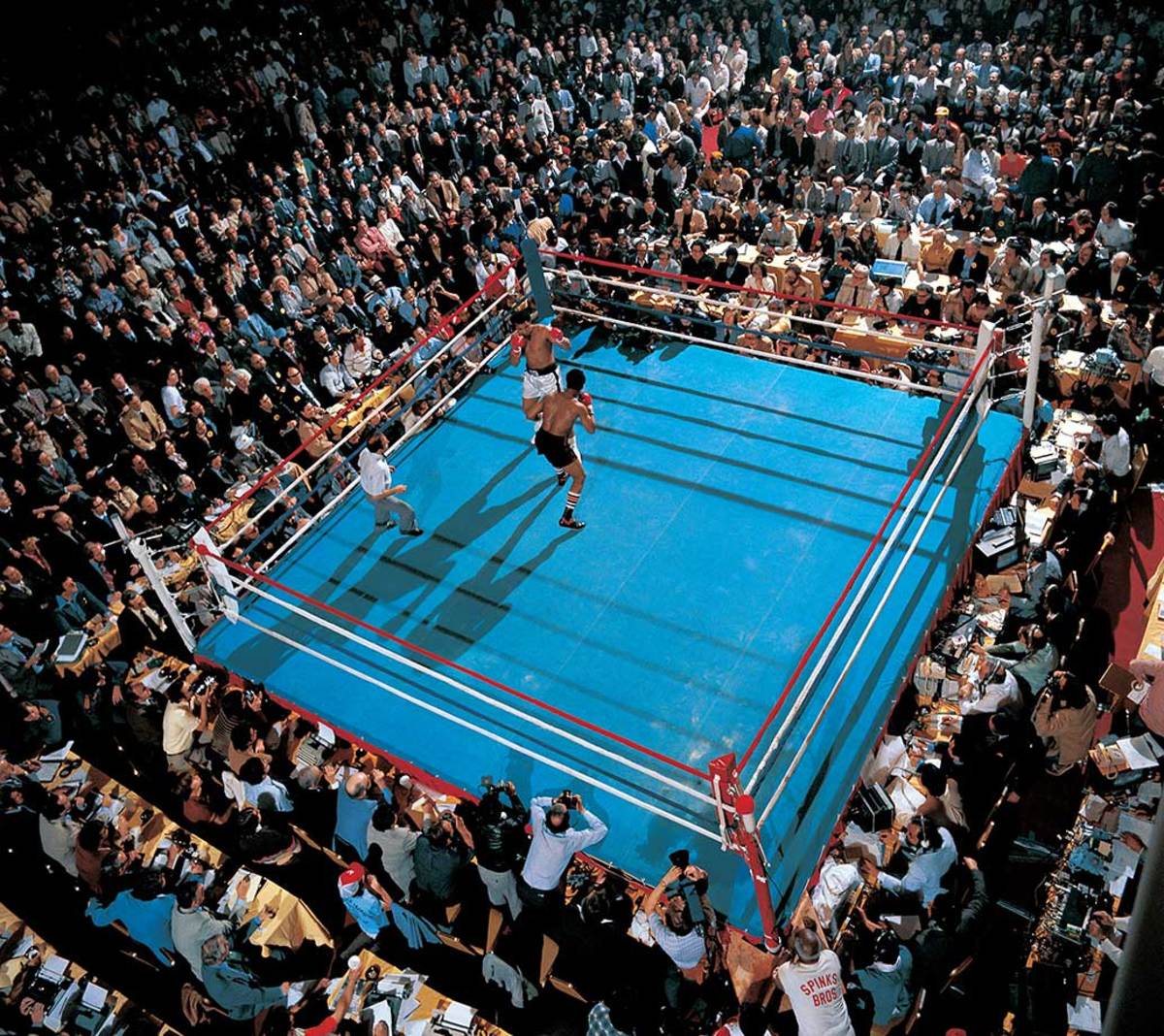

Ali squares off with Leon Spinks at the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel in February 1978. Spinks won the fight in a split decision, ending Ali's 3.5-year reign as the heavyweight champion. It was the only time in Ali's career that he lost his championship title in the ring.

Leon Spinks took center stage over Ali at the press conference after their fight. The victorious Spinks and his gap-toothed grin were featured on the Feb. 19, 1978 cover of Sports Illustrated.

Ali lands a straight right hand to the head of Spinks in the rematch of their title bout in 1978. Ali won on a 15 round decision.

Don King pulled the strings again when Ali faced Larry Holmes before their November 1980 fight. King became a key figure in Ali's career, promoting his biggest fights, the Thrilla in Manila and the Rumble in the Jungle.

Ali points at Larry Holmes before their bout at Caesars Palace in 1980.

Ali grapples with Holmes during their bout in 1980. Trainer Angelo Dundee stopped the fight in the 11th round, marking the fight as Ali's only career loss by knockout.

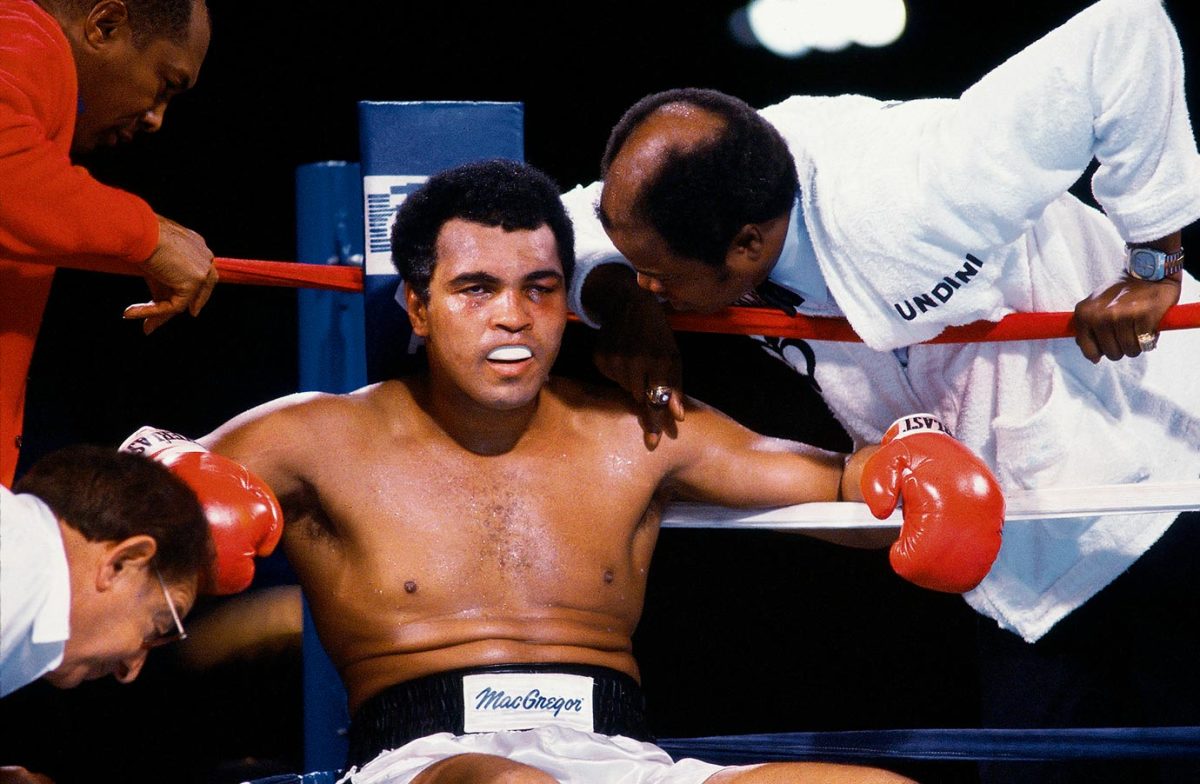

Drew Bundini Brown leans in to speak to Ali, who returned to fight Holmes after a brief retirement. By this time, Ali had already begun developing a vocal stutter and trembling hands and taken thyroid medication to lose weight that left him tired and short of breath.

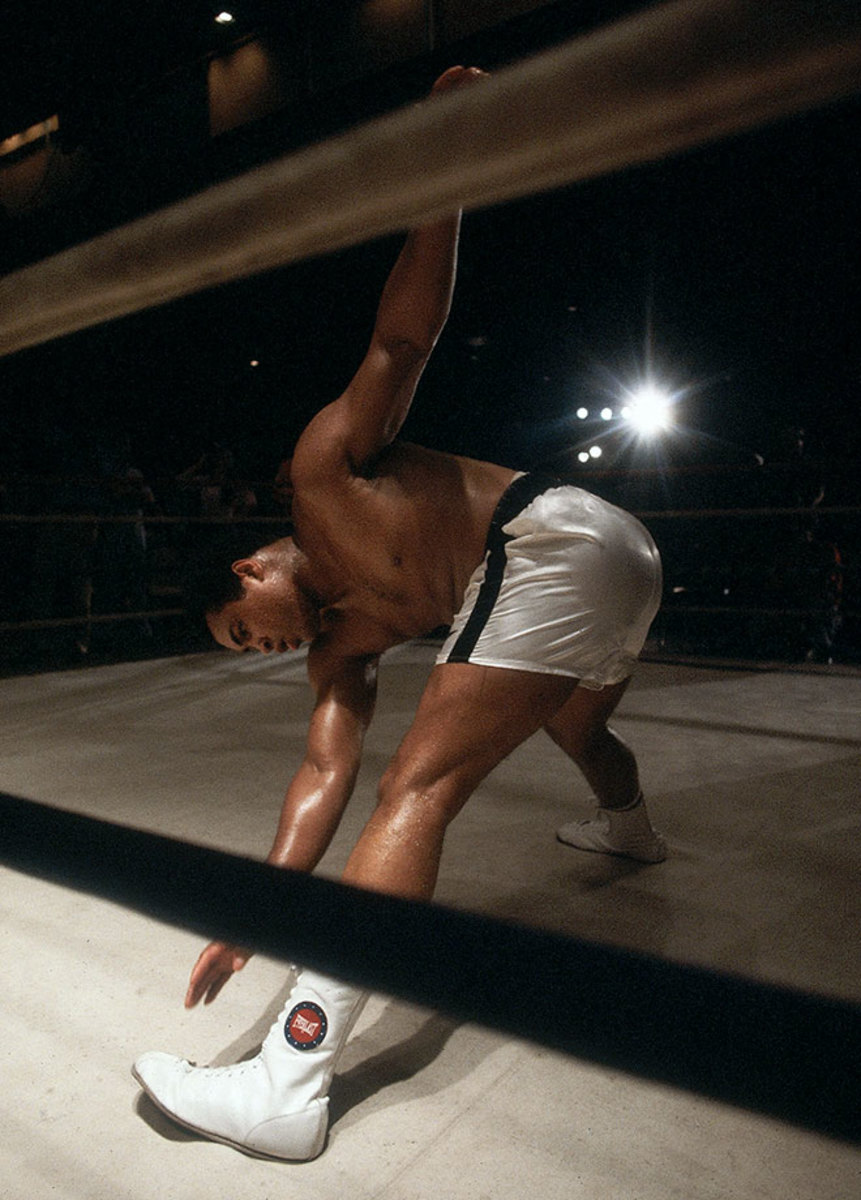

Ignoring pleas for his retirement, Ali stretches before a fight against Trevor Berbick in Nassau, Bahamas. Ali lost to Berbick in a unanimous decision and retired after the bout, the 61st of his career.

Ali pretends to spar with artist LeRoy Neiman at his home in Los Angeles. Neiman met Ali in 1962 and made many paintings and sketches from throughout Ali's life.

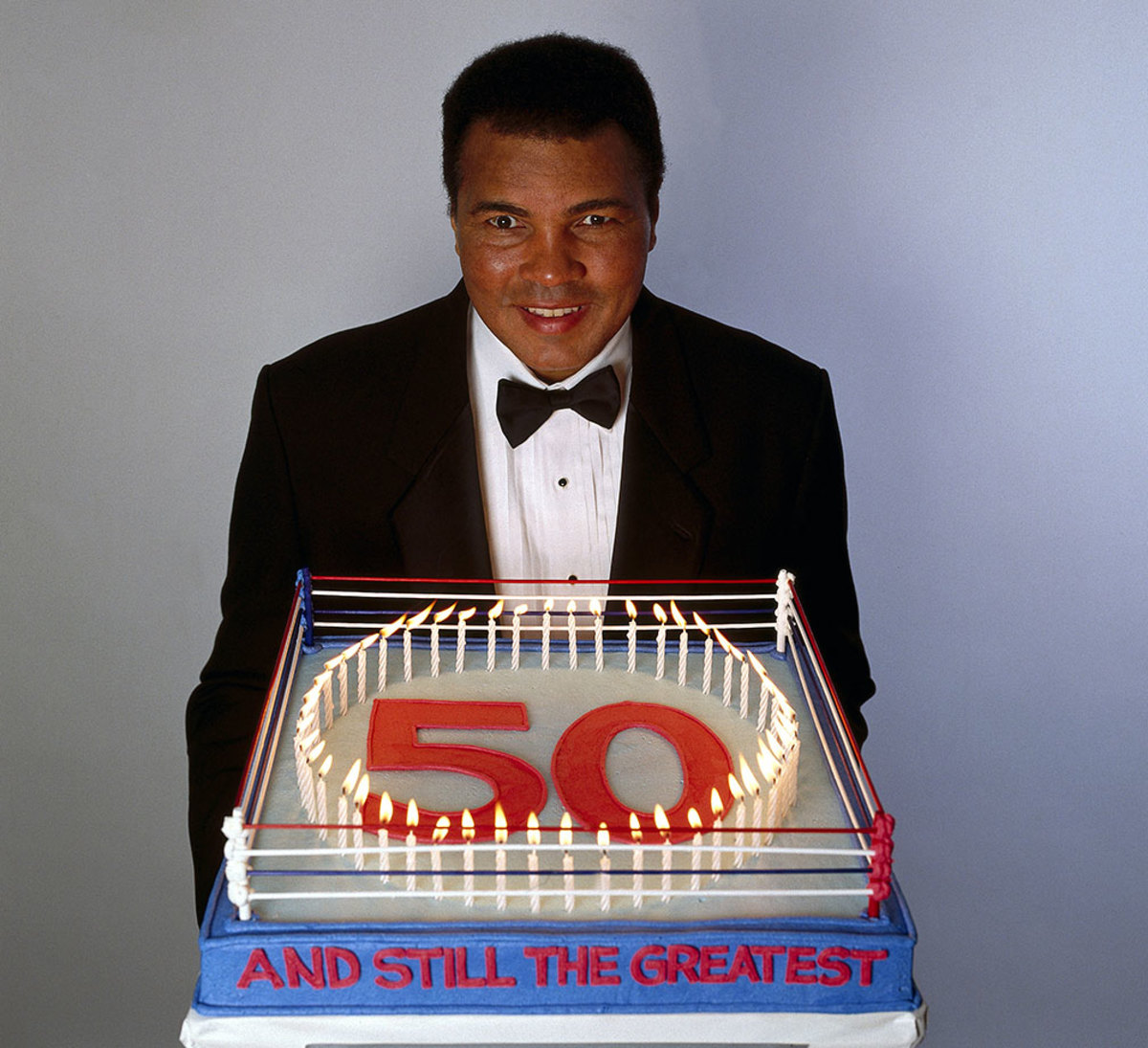

Cake in hand, Ali poses for a 50th birthday portrait in 1991. Although diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome seven years earlier, Ali was still active, traveling to Iraq during the Gulf War to meet with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages.

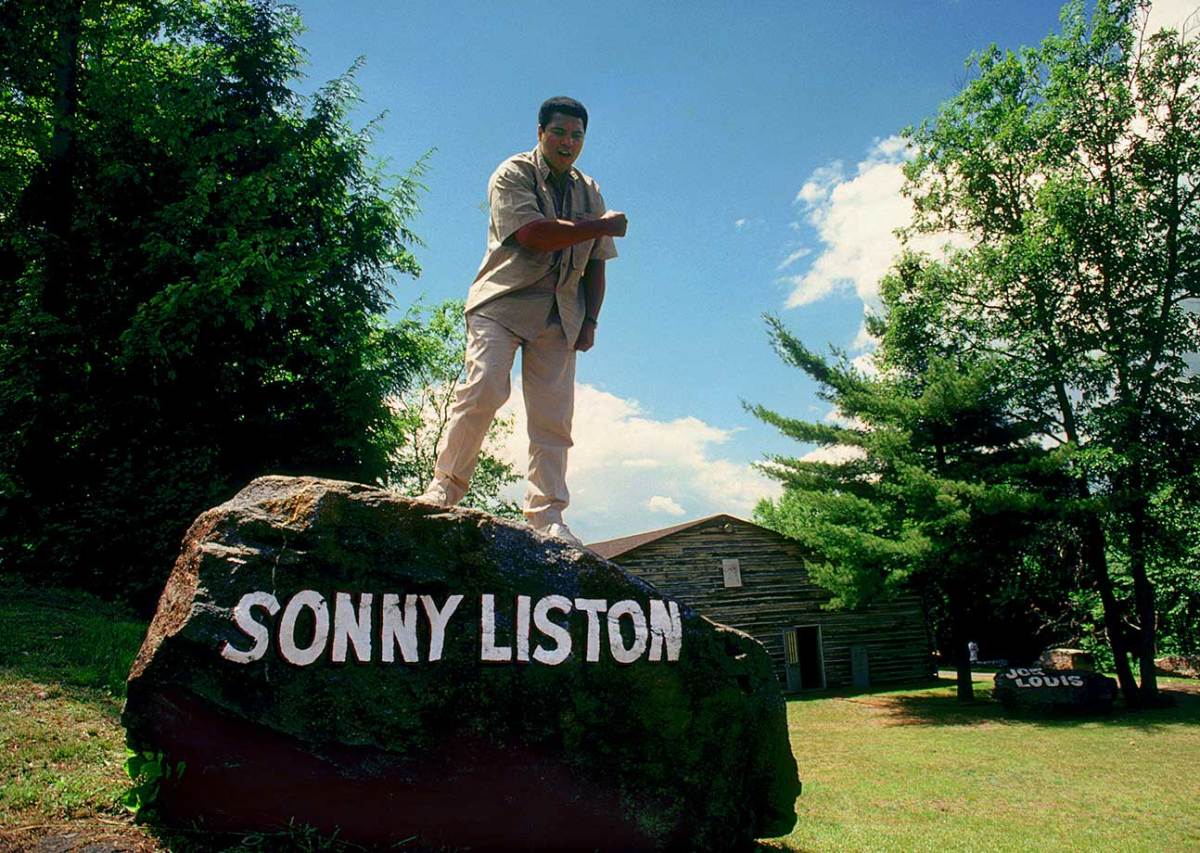

The same year, Ali stands atop of the Sonny Liston rock at his old training camp cabin. Ali and his father painted the names of famous boxers he admired on 18 boulders at the camp.

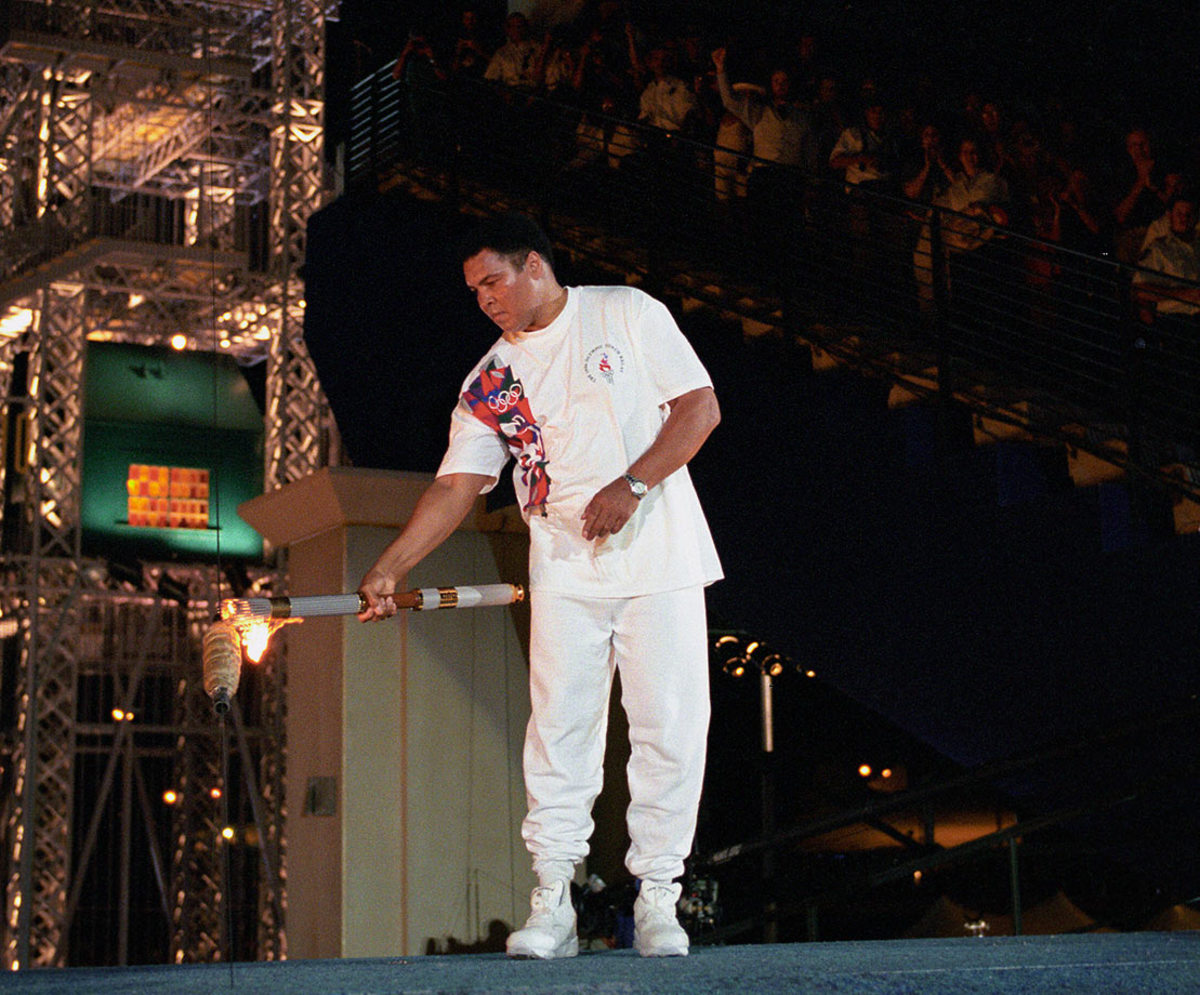

Ali carries the Olympic torch inside Centennial Olympic Stadium at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Despite trembling hands, Ali had the honor to light the Olympic flame in the stadium.

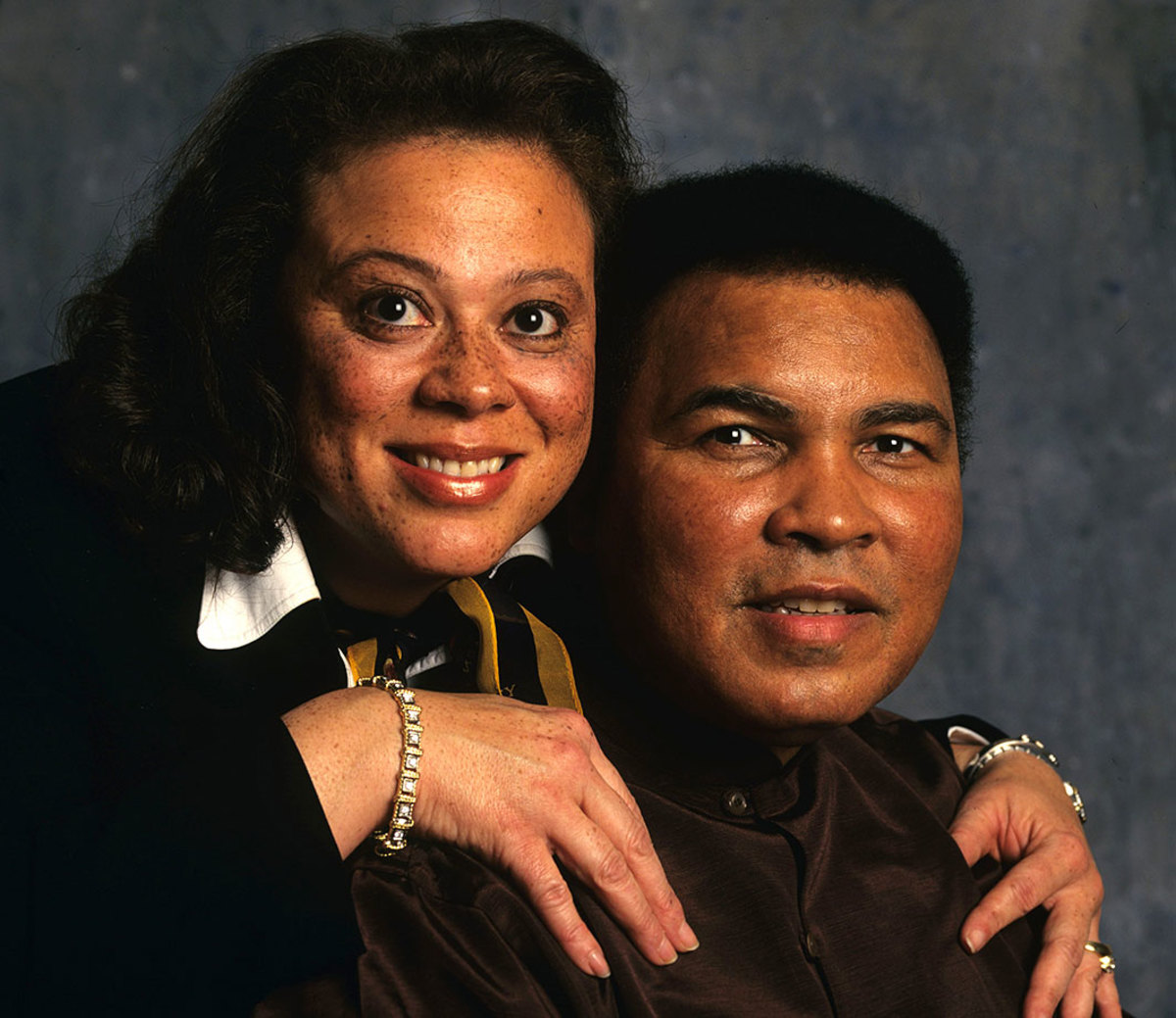

Husband and wife pose for a portrait during a photo shoot in 1997. Muhammad and Lonnie married in 1986 and have an adopted son together, Asaad Amin Ali.

Ali messes around with actor Billy Crystal during a photo shoot in 2000. Crystal's impression of Ali was notorious, and he performed at a tribute to the boxer on his 50th birthday in December 1991.

Ali lies on the canvas as his son, Assad Amin Ali, stands over him invoking memories of Ali's victory over Sonny Liston during a photo shoot in the gym at his farm on Kephart Road near Berrien Springs in 2001.

Fierce rivals in the ring, Ali and Joe Frazier pose for a portrait in the boxing robes they wore the night of their first bout at Frazier's Gym in 2003. Ali said after Frazier's death in 2011 that he was "a great champion."

Ali takes a punch from his daughter Laila Ali while sparring before her fight against Erin Toughill in 2005. Laila retired from her own successful boxing career with a professional record of 24-0.

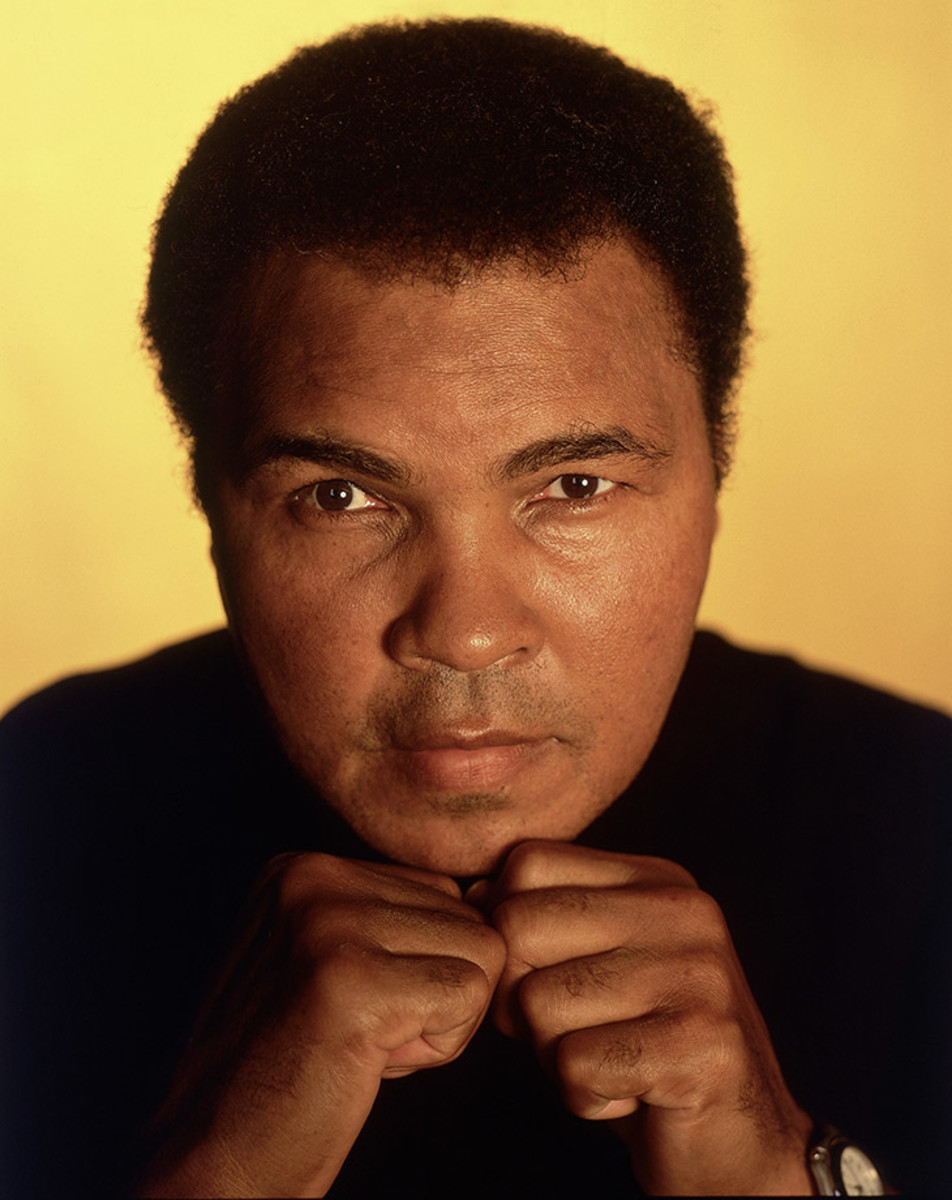

Ali poses with his fists up for a portrait in 2005.

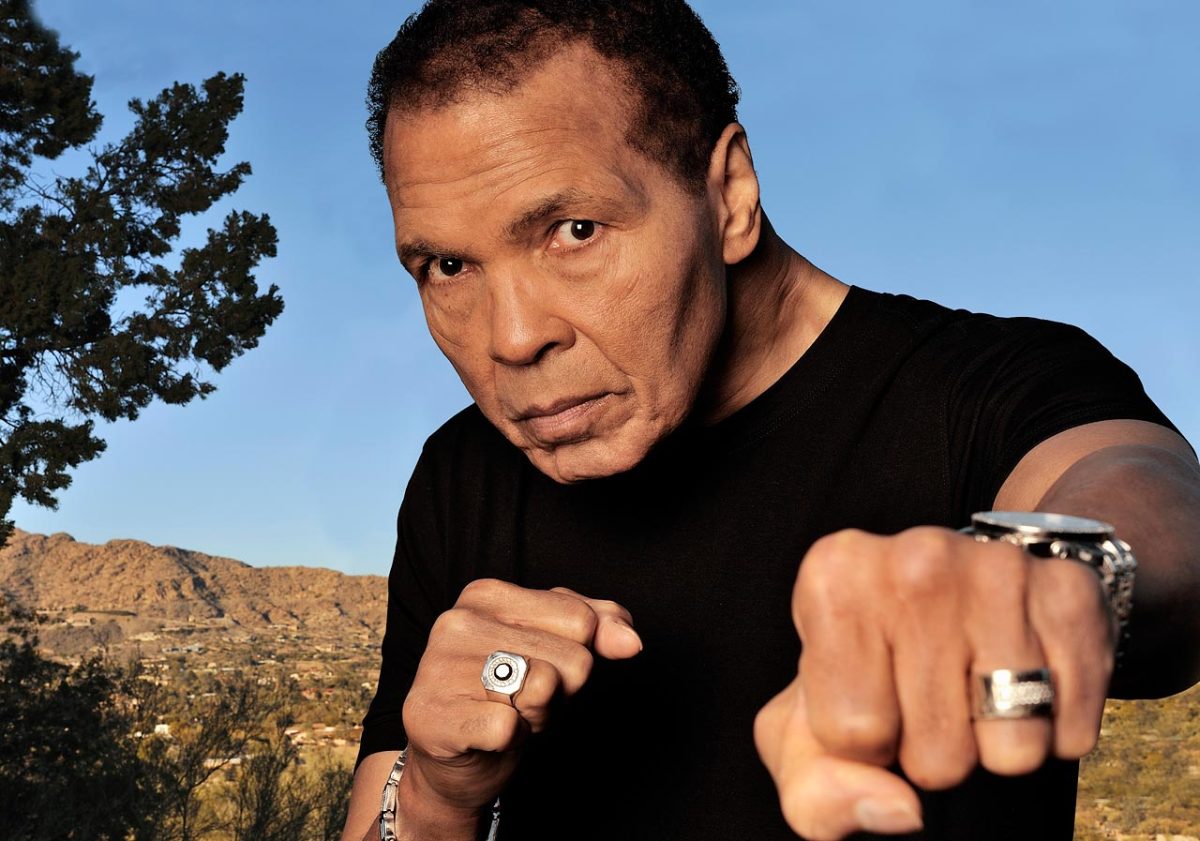

Ali poses with an extended punch in a 2012 photo shoot at his home in Paradise Valley, Ariz., to mark his 70th birthday.

Ali sits in front of a 70th birthday cake in January 2012 at his Arizona home. Later that year he appeared at the opening ceremonies for the 2012 Olympics in London to escort the Olympic flag into the stadium, 52 years after he won gold in Rome.