A case of conscience

This story originally appeared in the April 11, 1966 issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

It is one of those houses that always seem stuffy, where the warm smell of dinner hangs around till the next morning, and you can reconstruct the previous night's menu by spilling in corners. In this house there is the constant presence of Negroes, of too many humans for the size of the place, whatever their color. They drift in and out: celebrity Negroes, little pickaninny Negroes, big sparring-partner Negroes, door-to-door salesman Negroes, neatly dressed Muslim Negroes, old Negroes in skinny yellow shoes, young Negroes in porkpie hats, affluent Negroes driving black Cadillacs. In this house, kept neat and tidy by three uniformed Muslim "sisters," there remains something of the atmosphere of a "colored only" waiting room on the main line of the Florida East Coast Railway.

In a tiny front bedroom of the small bungalow in a shabby section of northwest Miami, the world's heavyweight champion lay half awake, undergoing an interview about his early life, trying not to tell too much, partially because there are portions that are painful to him and partially because he is under the impression that his "whole life story, as told by me myself," is a precious commodity worth a minimum of $50,000. The telephone rang on the cluttered dresser next to the bed, and Cassius Clay, in his role as Muhammad Ali, picked it up and said a dignified "hello." The caller was a local television personality, a man who could generate publicity; so the champ loosened up.

"Hello, Mis-ter Ed Lane," he said cheerfully. This is one of Clay's trademarks: calling white men by both their names. He likes to spot you approaching, and when you come into range he beams and throws out with mock pomposity and careful syllabilization: "Ange-lo Dun-dee!" "Gor-don Da-vid-son!" "Gil-bert Ro-gin!" That is, if he remembers your name. It takes many exposures to a white man before his name sinks into the consciousness of Cassius Clay. This is because he has erected a sort of racial curtain that screens whites out of his emotional life. A white man's name is of no importance to him, nor are "whiteys" themselves, except insofar as they can further his career.

Mr. Ed ("Mark 'Em Down") Lane, who until his recent death conducted conversational television interviews on a Miami station, fell in this latter category. "How you feeling?" Cassius asked. Lane remarked that the champion's name was all over the newspapers again that morning, whereupon Cassius began one of his Greek-chorus speeches, a mock lament that sounded as though it had been written the night before, rehearsed for several hours and saved for just such an auspicious occasion as a telephone call from Lane.

"I stay in the paper, don't I?" Cassius said softly into the phone. "Poor old me. Always in the press. Man, man! What do people think about me? A young 24-year-old boy, just a athlete, in the headlines eight times out of 10 for something other than boxing and always something controversial, exciting and drama. Year in, year out. Month after month, never dies, and I manage to come through it strong, and trained, too. What do people think about me?"

Seldom in the long history of rhetorical questions has one been answered so quickly and thoroughly. Within a few days Cassius had popped off about the draft, and newspaper editorial writers and columnists and statesmen and Bowery bums were telling the world heavyweight champion what they thought about him in some of the strongest language ever used to describe a sports figure. He was "a self-centered spoiled brat of a child," "a sad apology for a man," "the all-time jerk of the boxing world," "the most disgusting character in memory to appear on the sports scene." "Bum of the month. Bum of the year. Bum of all time."

The governor of Illinois found Clay "disgusting." and the governor of Maine said Clay "should be held in utter contempt by every patriotic American." An American Legion post in Miami asked people to "join in condemnation of this unpatriotic, loudmouthed, bombastic individual," and dirty mail began to arrive at Clay's Miami address. ("You're nothing but a yellow nigger." said a typical correspondent, one of many who forgot to sign their names.) The Chicago Tribune waged a choleric campaign against holding the next Clay tight in Chicago; the newspaper's attitude seemed to be that thousands of impressionable young Chicagoans would go over to the Viet Cong if Cassius were allowed to engage in fisticuffs in that sensitive city.

Amplified by the newspaper (on one day it ran 11 items about Clay), the noise became a din, the drumbeats of a holy war. TV and radio commentators, little old ladies from Champaign-Urbana, bookmakers and parish priests, armchair strategists at the Pentagon and politicians all over the place joined in a crescendo of get-Cassius clamor.

There were a few amateur psychologists who wondered if there might have been more to the public uproar than simple patriotism. "Doesn't it seem that people got madder than they should have?" an observer asked. "The thing is, Americans have become so guilty about Negroes that they bend over further than they want to in their attitude toward them. Then along comes somebody like Cassius, and they feel free to unload their resentment and pour it on."

Did he mean that some of the complainants might have been motivated by some factor as evil as race prejudice?

"Well, the people who made the biggest fuss about him arc the same ones who blew their tops when he became a Muslim. This made him antiwhite, and it inflamed their own prejudices. So they could scream about him, and what makes it nice is it's socially acceptable."

Whatever the underlying reasons, the bombilating Kentucky Negro had managed to rub the whole country the wrong way, and it had become necessary for the whole country to rise up in anger. As Clay's personal physician, the astute Ferdie Pacheco of Miami, explained: "Were getting back to the Korean war status, where the guy who goes into the Army is no longer a jerk but a man who's doing his duty and is to be applauded. Now comes Cassius saying he ain't got nothing against no Viet Congs. Had become out a year ago with that, many people might have said, 'Well, another Clay witticism.' Now he says it and he sounds like a traitor. And then he compounds the problem by saying it's a white man's war when there's a lot of colored people over there dying."

Said a Miami newspaperman who had studied and enjoyed Clay for six years: "Every time I begin to think that he really has the makings of a sweet person he does something like this, something so outrageous. Some of that stuff he's spouting is almost treason. Can you imagine what's gonna happen when he goes in the Army with some sergeant from south Georgia who's had about eight buddies killed in Vietnam?"

Even one of Clay's favorite people, his aunt, Mary Turner, a mathematics teacher in Louisville, spoke out. "He's gonna mess himself up so won't nobody go see him," Mrs. Turner said, with typical Clay-family bluntness. "Most folks feel like I do: when their sons get ready to go to the Army, they'll just pack the suitcases and go."

No one who was around Clay during those days when the draft board was getting ready to reclassify him believed that Cassius would "just pack the suitcases and go." Clay himself was the most surprised person in Miami when the draft board moved him into 1-A; right up to the moment of the announcement he had steadfastly believed that he and the Black Muslims and Leader Elijah Muhammad held some sort of power over the government. As Clay confided to a friend one morning, "They're trying to call me to the Army. Man, they know I ain't going in no Army! They ain't gonna bother me! There's too many people in the world watching me, see, and all of those black people overseas, they're Muslims, they're not Christians. And America's trying to make peace with 'em, and if they give me...."

His voice trailed off, and then he resumed his soliloquy in mocking, strident tones: "But Uncle Sam is a powerful man, and when Uncle Sam say 'Greeeeeeeeetings,' you go! Yeh, man!" His voice turned serious again. "Yeh, Elijah Muhammad's a powerful man. Whatever he say goes. Uncle Sam is in wars, wars everywhere, wars all over the country, everybody's at war today...."

Now he began an explanation of how he was sacrificing millions of dollars by being a Muslim, but how in the long run he could do more for the cause of the Negro by sticking to his adopted religion and letting the cash go. "All this stuff I turned down," he said, "and I'll show you where it make me bigger. Look how big I am. I got a call from Washington, the Pentagon called me. They said, 'We won't draft you. We've got to fake it because of the public. This has never happened before. We've never had to cope with no one like this before. This is a high office calling!" That's power. They know I'm not going."

He took a short telephone call, then went on: "I got invitations now. Haile Selassie want to see me in Ethiopia. That's a Moslem country. Ben Bella want to see me in Algeria. King Saud want to see me in Saudi Arabia. King Feisal want to sec me in Sudan. President Nasser of Egypt want to see me. These are men own their own countries. Powerful men, man! They own the land, they own millions of acres and control millions of people....

"The white want me hugging on a white woman, or endorsing some whiskey, or some skin bleach, lightening the skin when I'm promoting black as the best.... They want me advertising all this stuff that'd make me rich but hurt so many others. But by me sacrificing a little wealth I'm helping so many others. Little children can come by and meet the champ. Little kids in the alleys and slums of Florida and New York, they can come and see me where they never could walk up on Patterson and Liston. Can't see them niggers when they come to town! So the white man see the power in this. He see that I'm getting away with the Army backing offa me.... They see who's not flying the flag, not going in the Army; we get more respect...."

Clay picked up a few back issues of Muhammad Speaks, the house organ of the Black Muslim movement, and pointed out several vicious cartoons. One of them showed Uncle Sam whispering to the President: "Hurry! Sign all those niggers into war so they won't be left behind us!... Let our own sons stay behind in colleges and universities!... No, we know we can't win!" In his hand Uncle Sam holds a paper titled: BILLS TO GIVE NEGROES DEATH IN THIS WAR. A young Negro man stands to one side, thinking, "What shall I do or say?" and a tough-looking white man stands behind him saying, "G'wan, nigger, don't ask no questions!"

Another cartoon showed a Ku Klux Klansman starting to hang a Negro. Uncle Sam is grabbing the Klansman and saying, "Hold it, stupid! We don't lynch niggers like that nowadays—we can draft them and get the same results."

"Look at those cartoons," Clay instructed. "Look how bold our leader is. You know I gotta respect and obey a man as bold as that. If the government don't do nothing about it, then I gotta respect him."

A few nights later, after Cassius had been firmly entrenched in 1-A, a group of young men assembled in the living room of Clay's small house in Miami. "We're here to sec something big!" Clay advised me as I entered.

"Have a seat!" said Sam Saxon, one of the most enigmatic figures about Clay. "Cap'n Sam" functions as a sergeant at arms in a Miami mosque of the Muslims, and Cassius himself has referred to Saxon as "my bodyguard" (and at other times complained about newspapermen who used the same word to describe Saxon). Sam was one of Clay's earliest mentors in Black Muslimism and now has been promoted to the post of aide-de-training-camp at a salary of $150 a week, more than he makes on his regular job as a shoeshiner at racetracks around Miami. Saxon is a powerful Negro with blacksmith's arms, light reddish-brown skin and brownish-amber eyes, a graceful man with an easy step and a shy smile that shows thin gold linings on his teeth. When he gets excited, his voice rises an octave and his words double in tempo, like a caricature Negro in an early film. But most of the time he is quiet and steady, a rock for Cassius to lean on, and although many oldtimers claim that Saxon is one of the foremost white-haters in the Muslim movement, he is capable of an occasional act of fellowship, such as borrowing your car or shaking your hand. "Sometimes I get the feeling that Sam is putting me on, or putting the Muslims on, Or putting somebody on," says a friend. Perhaps this is because Saxon has at least a slight sense of humor, the rarest personality trait in the confraternity of the Black Muslims.

Sitting at the dining room table that night was Rudolph Arnett Clay, whose father belatedly rechristened him Rudolph Valentino Clay and who has re-rechristened himself Rahman Ali. The younger brother of Cassius Clay, Rahman (pronounced Rockmon) was writing a letter home to his young wife in Chicago. He was giving the task intense concentration except for occasional glances toward the television set that had been rolled into the stuffy living-dining area for the occasion. Rudolph is a very black, mustached man of 22 years and striking appearance. Another of Elijah Muhammad's true believers, he is also said to be an extreme hater of whites, although he is civil to white devils. It is only after several talks with him that you begin to realize he is giving you the bare minimum of shrift with a friendly smile on his face.

Reggie, a taciturn driver and general helper, was also in the assemblage that warm evening in Miami, as were a few anonymous Negroes, the kind who wander off the street and are invited inside by Cassius because he admires their pigmentation. In the kitchen three Muslim "sisters" puttered about in their severe white dresses, disassembling the evening meal. Back in a corner of the living room, out of the way of the men in the true Muslim tradition, sat an attractive Negro girl who conspicuously was not introduced to me. She remained silent throughout the evening. The entertainment before the house was the CBS news, and Senator Wayne Morse was denouncing the U.S. role in Vietnam.

"See that?" said Cassius. "All of them big men, they're saying we shouldn't go."

The group watched silently as Senator Russell Long asked General Maxwell Taylor if the United States was the international good guy or the international bad guy. Then the camera zoomed in on a newsman interviewing a GI at the front while shells exploded in the background. Cassius craned forward and said, "Is that real shooting going on?" He was assured it was. The GI told his interviewer that "if I had anything to say about it, I'd go home and spend a little time and come back again." This brought a titter to the room.

Inmates of the Indiana Girls' School rioted on the TV screen, moving Clay to shout, "It's the end of time," a favorite theme of his that he shares with his real father, Cassius Clay Sr., and his spiritual father, Elijah Muhammad. "We're in the last days! The last days!"

And suddenly a hush came over the room. Cassius Clay, the one and only Muhammad Ali, was on TV spitting out his antidraft speech to Interviewer Bob Halloran. "Yes, sir, that was a great surprise to me. It was not me who said that I was classified 1-Y the last time.... It was the government who said that I'm not able.... Now in order to be 1-A I do not remember being called nowhere to be reclassified as 1-A. These fellows got together and made the statement that I'm 1-A without knowing if I'm as good as I was the last time or better. Now they had 30 men to pick from in Louisville, and I'm also sure that there are at least 30 young men that they could have picked from. Instead they picked out the heavyweight champion of the whole world. There's just one in my class. You have a lot of men in baseball they could have called. You have a lot of men in football they coulda called. You have a lotta men that they coulda called that are of school age and have taken the test that are 1-A. Now, I was not 1-A the last time I was tested. All of a sudden they seem to be anxious to push me in the Army.... And another thing I don't understand: Why me? A man who pays the salary of at least 50,000 men in Vietnam, a man who the government gets $6 million from a year from two fights, a man who can pay in two fights for three bumma planes—"

The undignified interview came to an undignified end in mid-sentence, and Cassius was on his feet in the room.

"That was a good one, wasn't it?" he asked nobody and everybody. "Did Lyndon Johnson watch that? Is he watching this news or the other one?"

Saxon said, "He's got 'em both on: one set on one and one on the other. Even if he missed it, he'll get the tape of it."

Cassius let that sink in, found it reasonable and began to muse. "Yes, sir, three bumma planes.... That told 'em.... That make it clear...."

Billy Graham came on the screen, and a dialogue began between the North Carolina evangelist, inside the tube, and Sam Saxon, sitting on the sofa.

Graham: We know that things cannot go on as they are. History is about to reach an impasse.

Saxon: You tell 'em.

Graham: We are now on a collision course. Something is about to give!

Saxon: That's right!

Graham: Hard major decisions have to be made!

Saxon: Yeh!

Graham: Crisis presses in around us!

Saxon: Teach!

Graham faded and President Johnson came on, telling about a letter he had received from a woman whose son had died in Vietnam. From his first words—"In these troubled times"—the group found the President vastly amusing.

"Listen to Johnson," Saxon said with a wide grin.

"...I am sustained by much more than my own prayer," the President said.

"Talk to "em!" Saxon said as someone giggled.

President Johnson read the letter that ended "So we asked God to bless you and your little family."

"Sing it, President!" Saxon said.

When the newscast ended, Clay announced: "Elijah Muhammad been saying 1966 will be the end," as though the program Newsnight had confirmed that the final year was at hand. "Years ago he was saying the same thing. Thirty years ago." Clay mumbled aloud about the President for a few seconds, but all I could make out clearly was, "I wonder if he had me on." Stars in My Crown, a homey movie about a southern preacher, came to the screen, but it did not suit the champion's taste. "C'mon," he said brusquely to the mystery girl in the corner, "we goin' fo' a walk."

The next morning the champion had an early telephone call from Chicago. He was told that Chicago newspapers were on the street with stories that he would have to go in the Army, and the fight would be canceled. The stories would kill the gate, Cassius was told, and he'd better correct them if he wanted to make any money out of the fight.

Clay sat in his underwear next to the living room phone and began burning up the long-distance wires. "Hello, may I speak to Leo Fischer? Hello, Mr. Fischer? This is Muhammad Ali, the world heavyweight champion. Ben Bentley was talking to my lawyers about the fight. Something was out up there about the fight was off.... Well, it's not. We're gonna appeal.... Well, it's in the Islamic belief. We don't bear weapons. We don't fight in wars unless it's a war declared by Allah...Allah...Allah...AlLAH! That right. Anyone who understands the Holy Qur-an or the Islamic religion, this is nothin' new or nothing...I see where the whites themselves are arguing, even in the White House they're on TV arguing every day. They're saying they're gonna get out, and they don't like it. I see whites burning up their draft cards, and they say it's a nasty war and we shouldn't be in it. That's what the senators and officials of the government themselves are saying. So our religion teaches me we don't participate in wars to take the lives of other humans.... Well, I don't think they could be mad at me about my religion.... Yeh, well, if their religion don't teach it, I guess they go...."

After a few such calls he dialed a reporter (perhaps from the Tribune) who wanted to debate the subject, and Cassius went to the bedroom phone, shut the-door and accepted the challenge. An occasional phrase was audible: "Well, we'll make the appeal, and the fight'll go on.... We don't take up no weapons in no war unless it's a war declared In Allah himself. We arc taught to defend ourselves if attacked.... No, I don't know nothing about no Viet Congs.... Well, the whites themselves have been demonstrating against the war. They're mad at the war...."

When the argument finally ended and Cassius stomped back through the living room in his battle raiment of undershirt, undershorts and socks, I said, "Haven't you got enough to do?"

"Don't they keep me going?" he said, and laughed, pleased with his busy morning's work. Later, when his words on the draft were thrown back at him by editorial writers and columnists, he claimed that they had "taken my words as though I'm a politician." and he issued broad hints to the effect that he was just a poor little ignorant tighter and he had been tricked and it was unfair to quote him on Vietnam and the draft and such weight) matters.

"As usual, you know me and my big mouth." he said. "It didn't get me in trouble in the past, but I spoke out on a few things that could be considered politics and I had no business doing it.... I feel a lot better after calling, apologizing to the commission and the boxing authorities who I put on a limb and caused 'em national embarrassment.... I'm known for talking a lot."

These weaselly alibis were not the real Cassius. They were dreamed up by people close to the money end of the fight, and he was mouthing the words as a personal favor to them. But his explosive remarks to the press on the phone that morning had represented the most serious side of Cassius Clay, a fanatically religious side that only his closest friends understand. They were not surprised when Clay journeyed to the Illinois Athletic Commission and refused to recant. After all, Clay is a Black Muslim; his god is Allah; his hero is Elijah Poole, now known as Elijah Muhammad. Muhammad, the "Messenger of Allah," served three years in prison during World War II for urging his flock not to go to war, and by his own reckoning, nearly a hundred Black Muslims went to jail for taking his advice. Clay identifies closely with Elijah Muhammad and takes orders from no one else.

"Cassius was searching for a father,"' said a close relative, "and Elijah Muhammad is it. If Elijah tell him don't go to war, go to jail, he'll go to jail. That man have Cassius by the nose."

Muhammad's book Message to the Blackman, is studied by Cassius like a Bible. (Since his reading speed is below average, Clay often has passages read to him. He even enlisted me for the task once.) The dominant theme of Muhammad's book is hatred of the whiles. Beneath the fanciful tales about half-mile "wheels" in the sky, "1,500 bombing planes" preparing to wing down to earth and drop steel bombs into the earth on behalf of Allah, hidden in all the wild-eyed prognostication is a simple genocidal declaration of war: "The only way to end war between man and man is to destroy the warmaker.... According to the history of the white race (devils), they are guilty of making trouble, causing war among the people and themselves ever since they have been on our planet, Earth. So God...has decided to remove them from the face of the Earth.... Allah will fight this war for the sake of His people (the black people), and especially, for the American so-called Negroes.... We are Allah's choice to give life, and we will be put on top of civilization." America will fall, Elijah predicts, "in 1965 and 1966."

Cassius Clay has a blind and total belief in every word of Message to the Blackman, and thus he becomes a rare individual: a genuine, if misguided, conscientious objector. As a professional observer and friend of Clay's pointed out: "The government may say his religion is nutty as a fruitcake, but the government can't say it's not his religion. Now how the hell are you gonna send a kid like that to tight against people of color, his people? How the hell are you gonna send him into battle alongside white Americans that he regards as the real enemy? That kid has a sincere, true, deep hatred of whites that goes all the way back to his childhood and the way his father brought him up. You meet the-old man, and you'll know exactly what I'm talking about. He set up an environment that made the Black Muslims or some other hate-white movement perfect for the kid. Some of these Black Muslims arc just tough while-haters who find it convenient to belong. It keeps 'em out of the hot sun, and a lot of 'em are making a buck off the religion, but Clay's really and truly hooked. The William Morris Agency told him he'd make a quarter of a million dollars a year in endorsements and advertising. About a week later he announced he was a Black Muslim and the William Morris deal was as dead as a duck. He hasn't made a nickel off it since. Does that sound like somebody who's faking his religion."

The idea of Cassius Clay's going to jail for draft-dodging would have brought a loud horselaugh not many years ago. "I am going to be a clean and sparkling champion." the young man from Louisville had said, and he was. No smoking. No drinking. No messing around (well, not much messing around). He was hailed as "the new while hope," of boxing by at least one enthusiastic writer. His cheerful pronouncements ('if Cassius say a mosquito can pull a plow, don't argue. Hitch him up!") brought laughs from people who had had no previous interest in boxing, and attendance climbed. Boxing had hit bottom in 1950, with total receipts down to less than $4 million. With Cassius carrying on, the sport took in $7.8 million in 1963, $18.1 million in 1964, another $8.9 million in 1965.

His antics benefited every division, and if he was a little wide in the mouth, who cared? It was all in a spirit of good humor; the public knew the kid was just building gates, and wasn't he good to his mother and father? His Buddha-shaped nun her, Odessa Grady Clay, the very prototype of the sweet, kindly southern Negro mammy, raved about him to the press: "He used to say, 'When I become champ I'm gonna buy you this and buy you that.' And he'd sit and talk for hours at a time when he was 12 years old. He was gonna get me a house and furniture and a car and travel. And he have done all those things."

Even allowing for the ex post facto mythmaking that grows up around champions, Clay seems to have called the shot on an impressive number of achievements, including his Golden Gloves championship, his Olympic gold medal and his heavyweight championship of the world. His knockout predictions ("Powell must fall in three" were usually about stiffs, but it is not easy to flatten even a stiff in an appointed round, and the forecasts added zest to his appearances.

But as he got bigger and bigger, Clay began losing his sense of proportion. He seemed to skate right to the edge of mama in his prefight scenes. He lost track of the difference between buffoonery and nastiness, and the public began to sour on him. People close to him tried to make explanations and apologies. "I'll never understand the resentment of his popping off." said Angelo Dundee, the best trainer in the fight business. "I remember when I was younger, hearing the people talk about, 'Gee, Joe Louis is a great fighter, but he can't talk,' and today, you have a fellow who talks and fights, and there's resentment. There's no figuring the public. The public is a tough customer to be satisfied."

So were the writers, especially after Clay began openly espousing the principles of Elijah Muhammad. "Clay is likely to hurt the sport badly by his ideologization of it." William F. Buckley wrote. "One can only hope that, to put it ineptly, someone will succeed in knocking some sense into Clay's head before he is done damaging the sport and the country, which, however much he now disdains it. gave him the opportunity to hate it from a throne." George Sullivan wrote: "There was fun and amiability in Cassius Clay when he began his rise to national prominence. He was a popular good-looking youngster—precisely what the stricken fight industry needed. Clay was regarded as the potential savior of the sport, but some people feel he has been more of a hangman."

When Sonny Liston remained affixed to his stool at the beginning of the seventh round in Miami Beach two years ago, Cassius Clay automatically became the best-known sports figure in the world. Europeans may never have heard of America's Koufax, and North Americans may know little about Brazil's Pelè, and neither Americans nor Europeans know about Red China's Chuang Tse-lung, but who doesn't know who the heavyweight champion is?

Clay mounted his pedestal and used all his power and glamour to become the most hated figure in sport. Long before his unfortunate remarks about "them Viet Congs," domestic and foreign reporters alike (whose accuracy and sophistication were erratic) were lambasting him—for his lack of sportsmanship, for his tasteless braggadocio, for his cruelty and his contempt of others. The "clean and sparkling champion" was now being portrayed as a clean and sparkling bum, and more than a few people were taking nervous second glances at a remark made by Clay to Louisville Sportswriter Dean Eagle. Full of himself and his glory, Cassius had said, "I am the champion who will end all boxing."

Like most matters concerning Clay, the quote was paradoxical. His life is a symphony of paradoxes, and the biggest of all is that hundreds of thousands of words have been written about him, and yet his essential character, his attitudes, the fears and forces that drive him, remain unknown. The major public relations victory of Cassius Clay's career may lie in what he has kept hidden.

SI's 100 Greatest Photos of Muhammad Ali

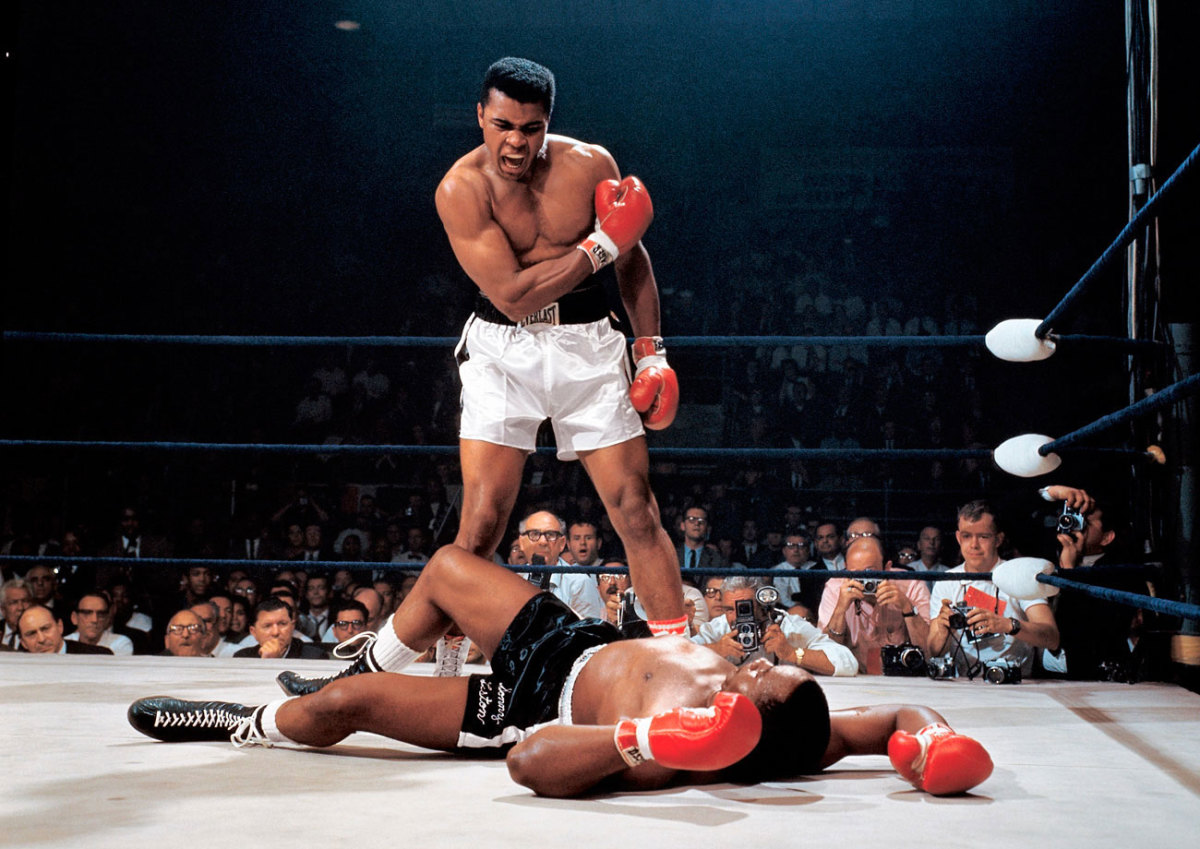

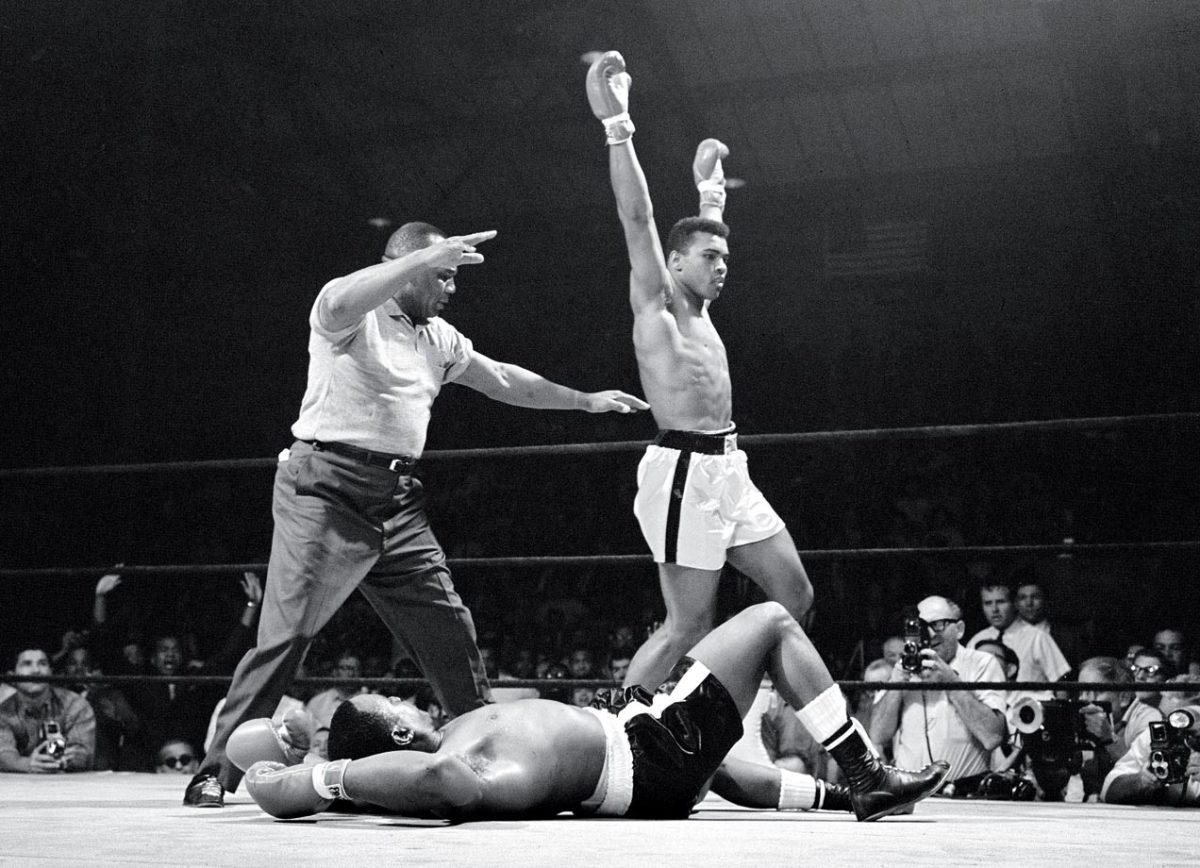

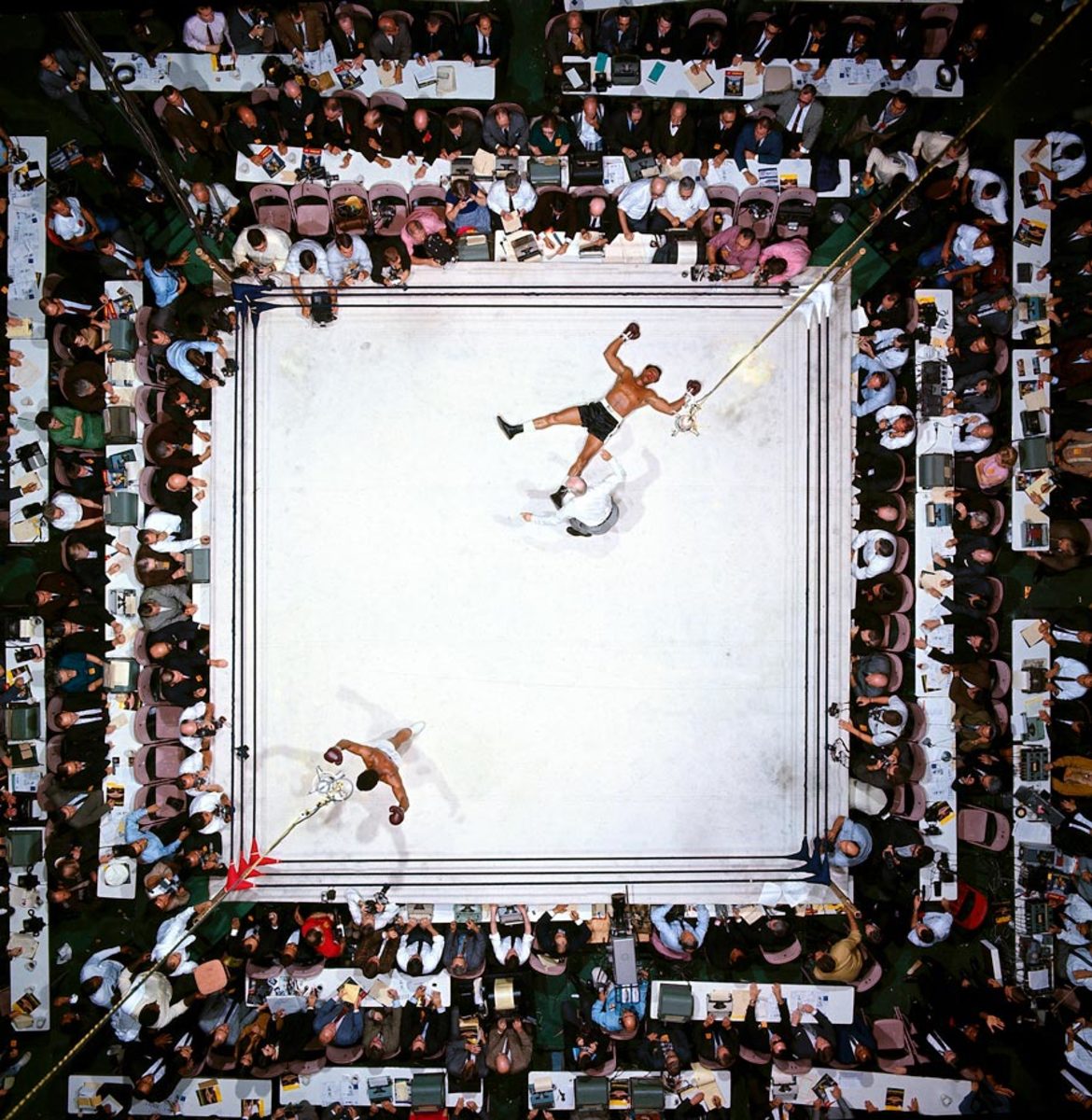

In one of the most iconic and controversial moments of his career, Ali stands over Sonny Liston and yells at him after knocking the former champ down in the first round of their 1965 rematch. Skeptics dubbed it "the Phantom Punch," but films show Ali's flashing right caught Liston flush, knocking him to the canvas. Refusing to go to a neutral corner, Ali stood over Liston and told him to "get up and fight, sucker."

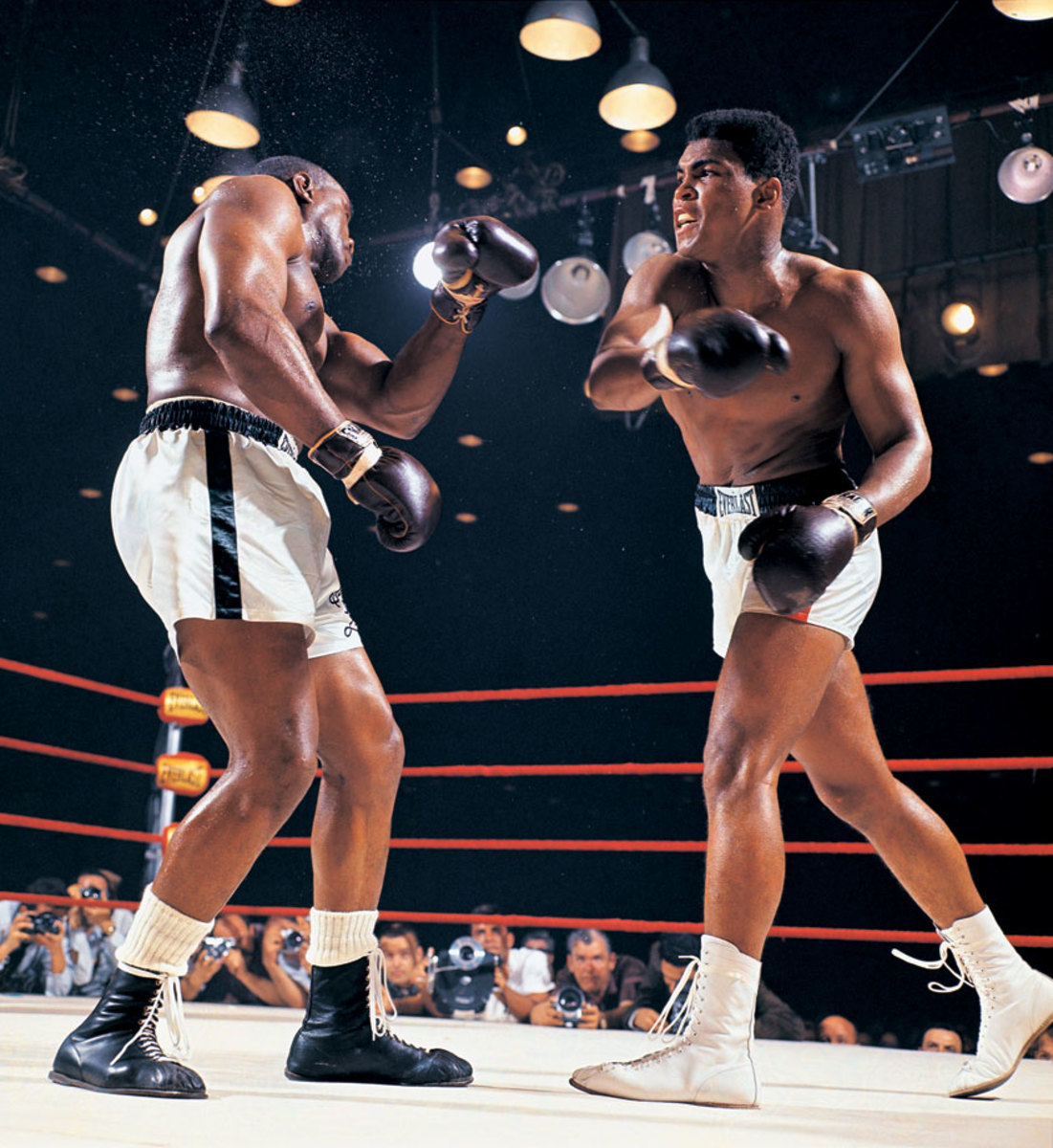

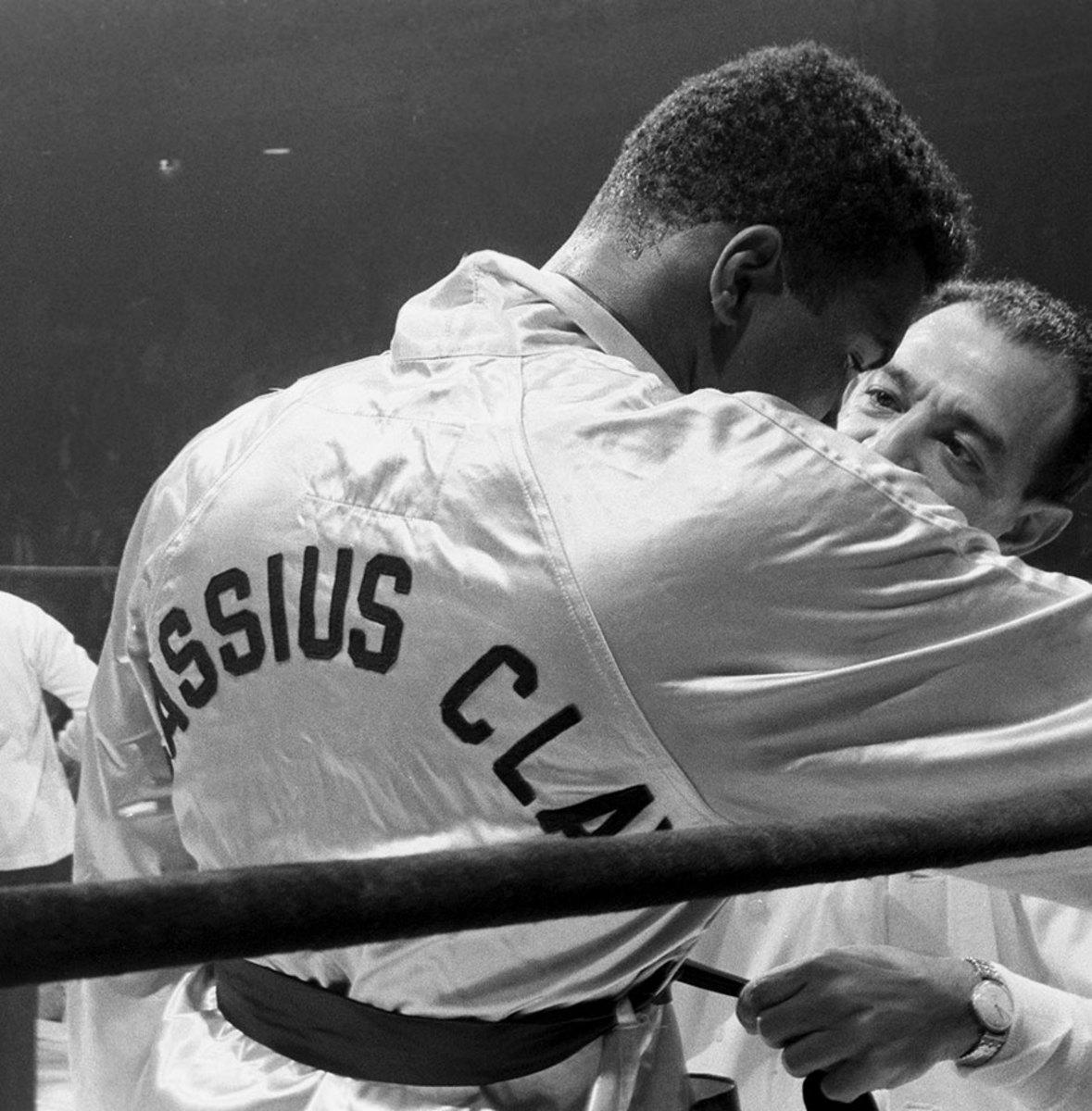

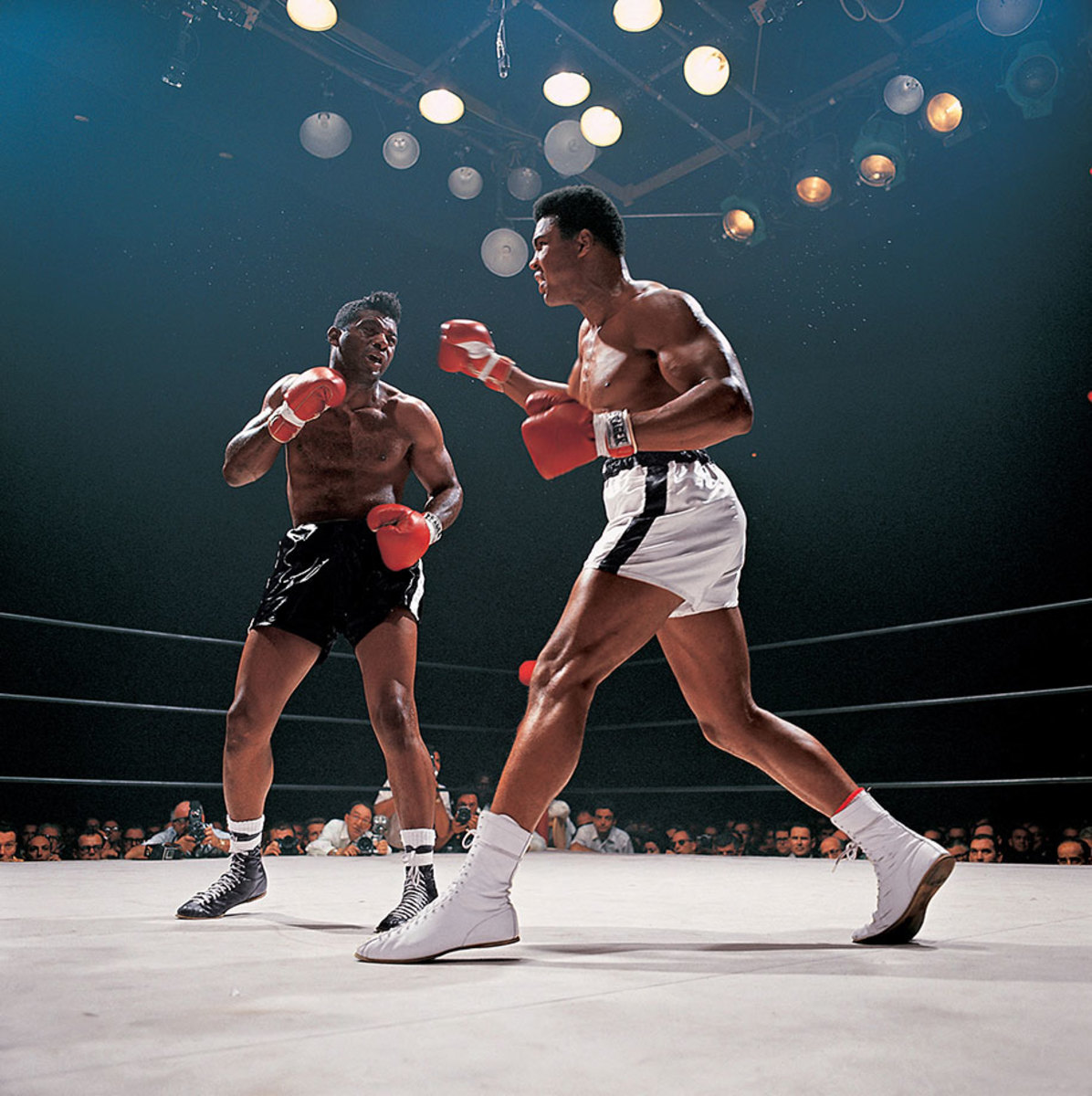

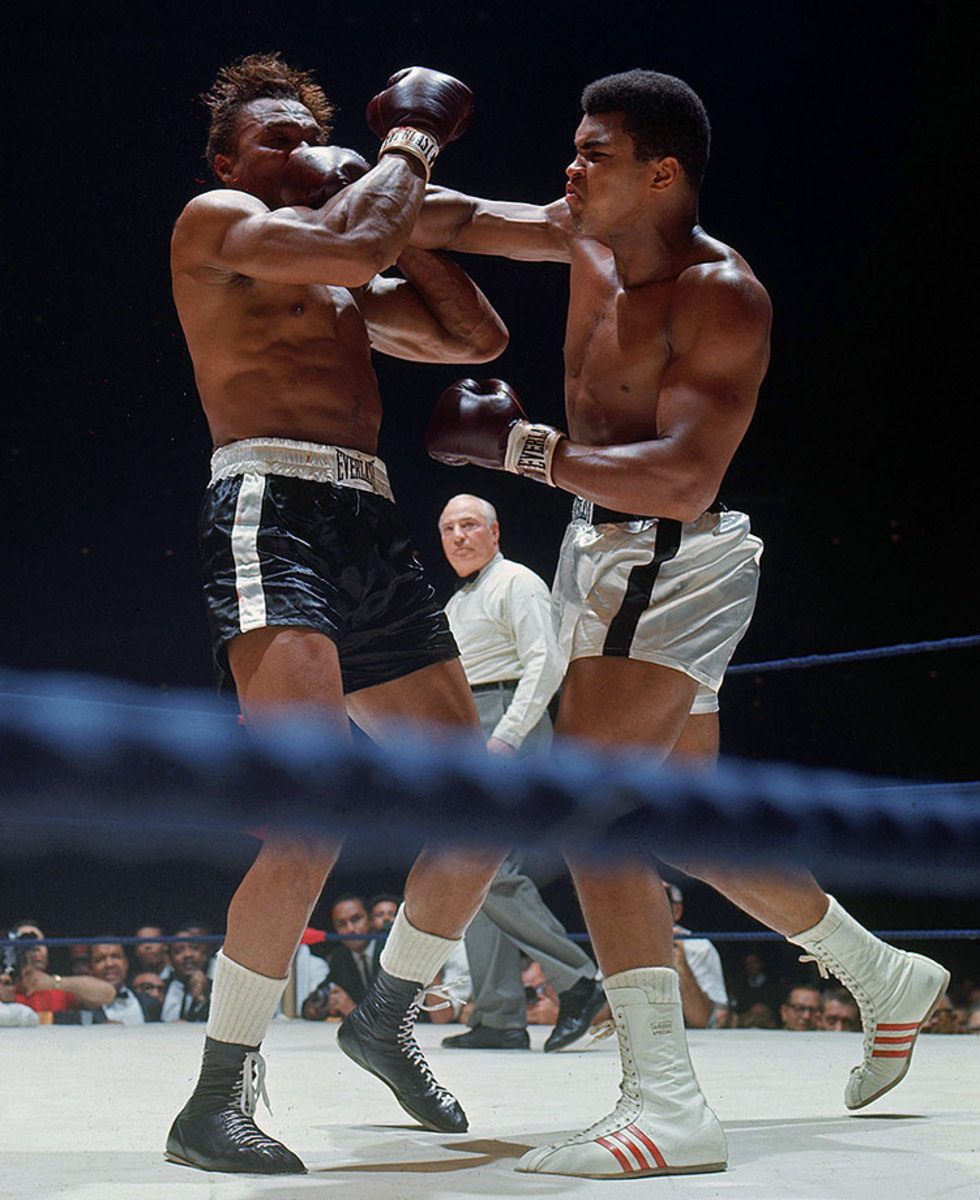

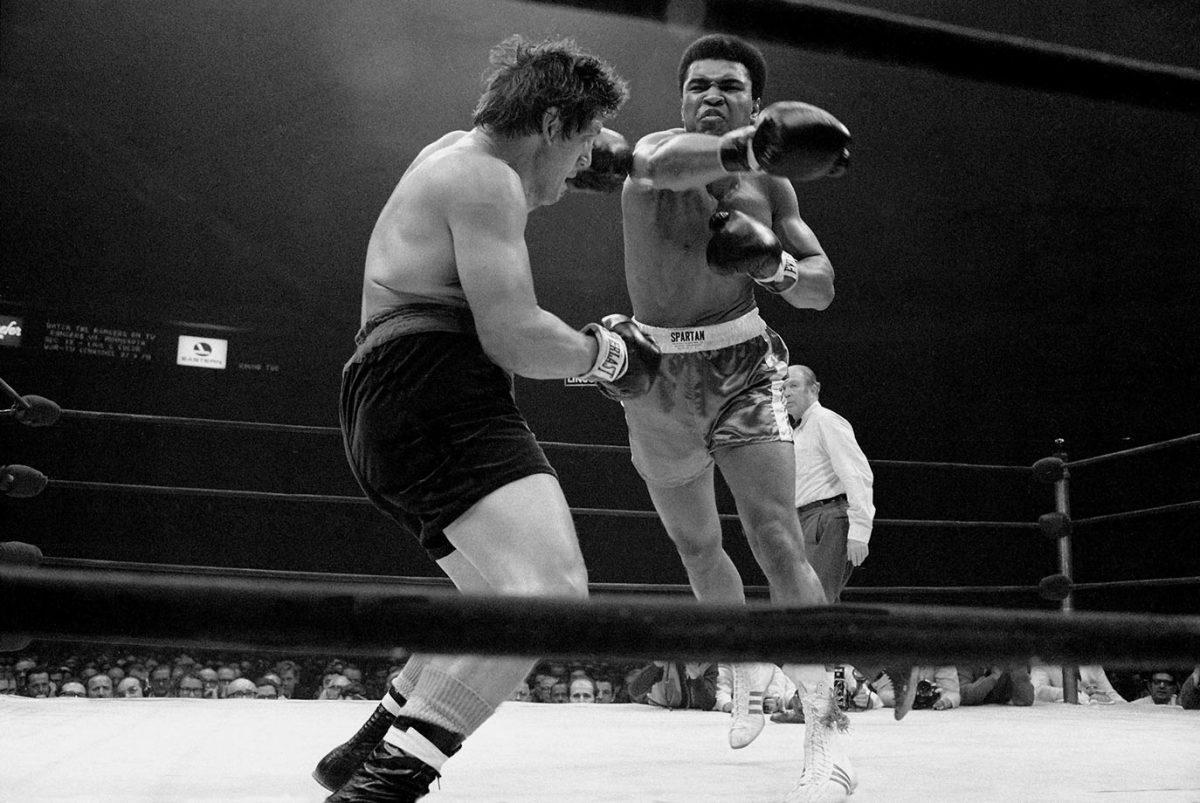

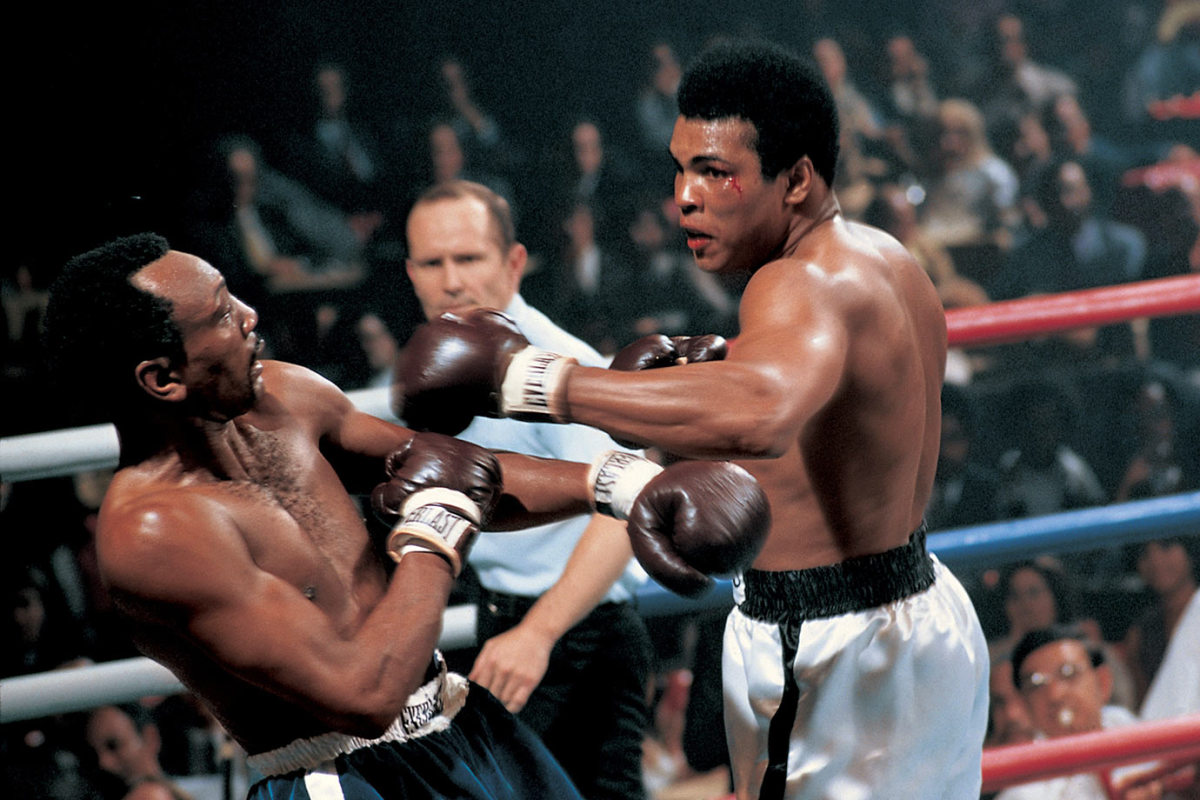

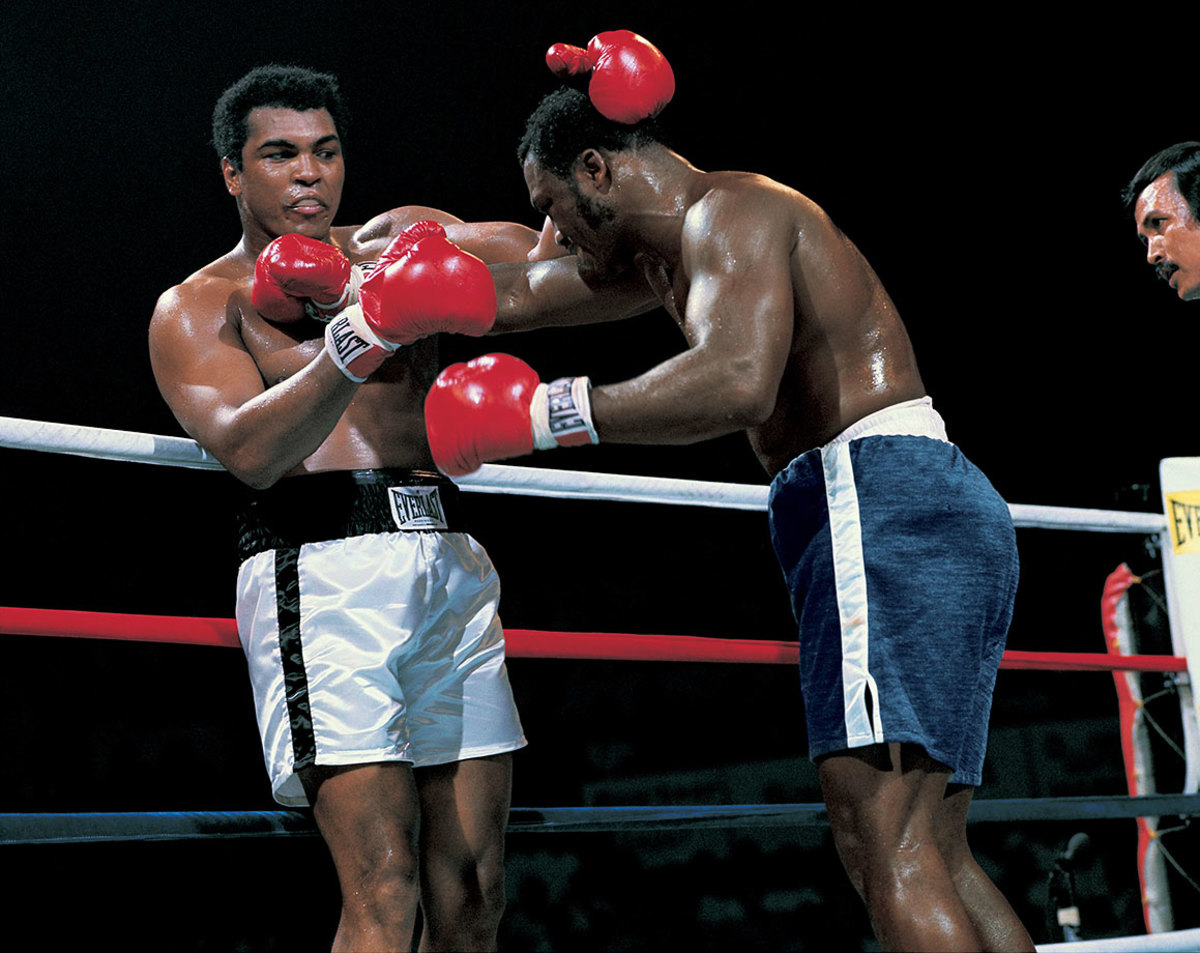

At 22-years-old, Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) battered the heavily favored Sonny Liston in a bout that shook the boxing world. The fight ignited the career of one of sports' most charismatic and controversial figures, whose bouts often became social and political events rather than simply sports contests. At the peak of his fame, Muhammad Ali was the best known athlete in the world. Liston, one of the most feared heavyweight champions in history, was a 1-8 favorite over the young challenger known as the Louisville Lip. But Clay, here stinging the champ with a right, used his dazzling speed and constant movement to dominate the action and pile up points.

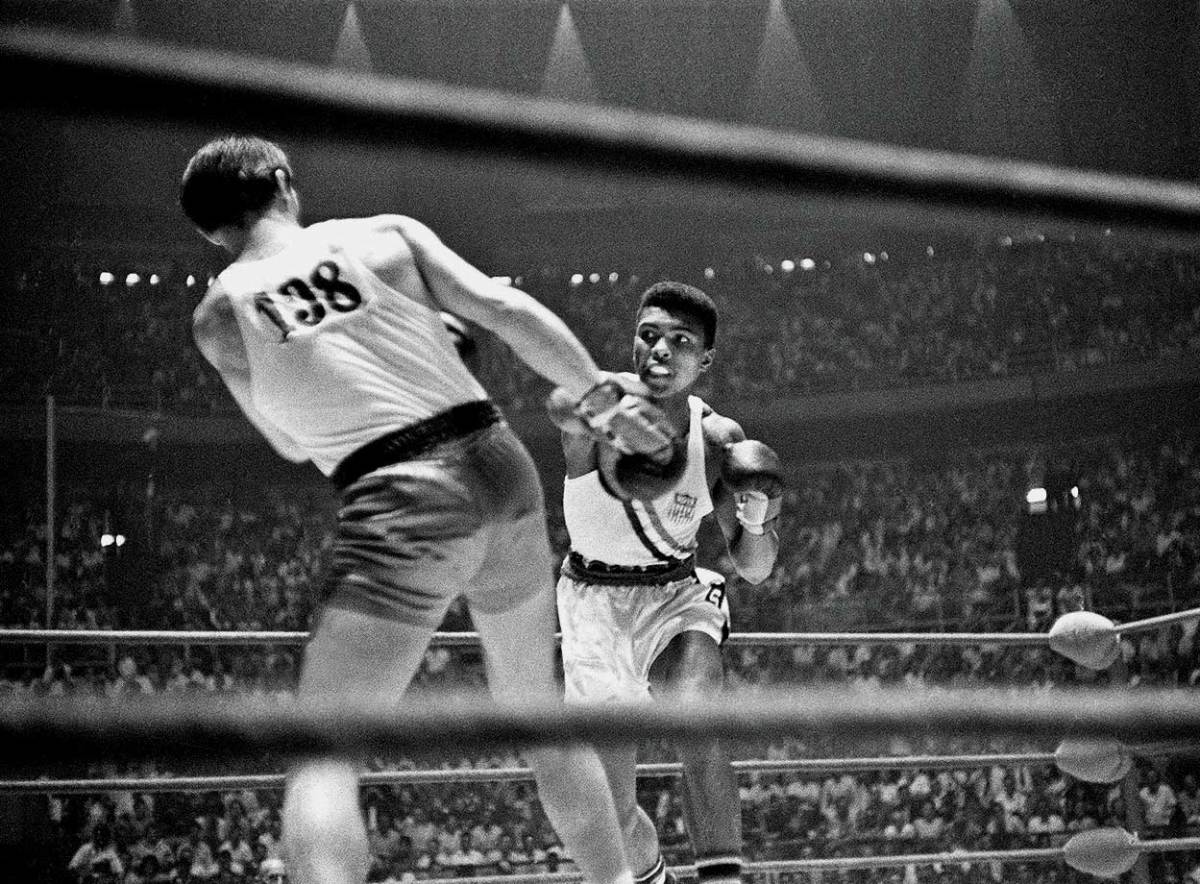

Cassius Clay punches Zbigniew Pietrzykowski of Poland during their gold medal bout at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Clay defeated Pietrzykowski 5-0 for the light heavyweight gold medal.

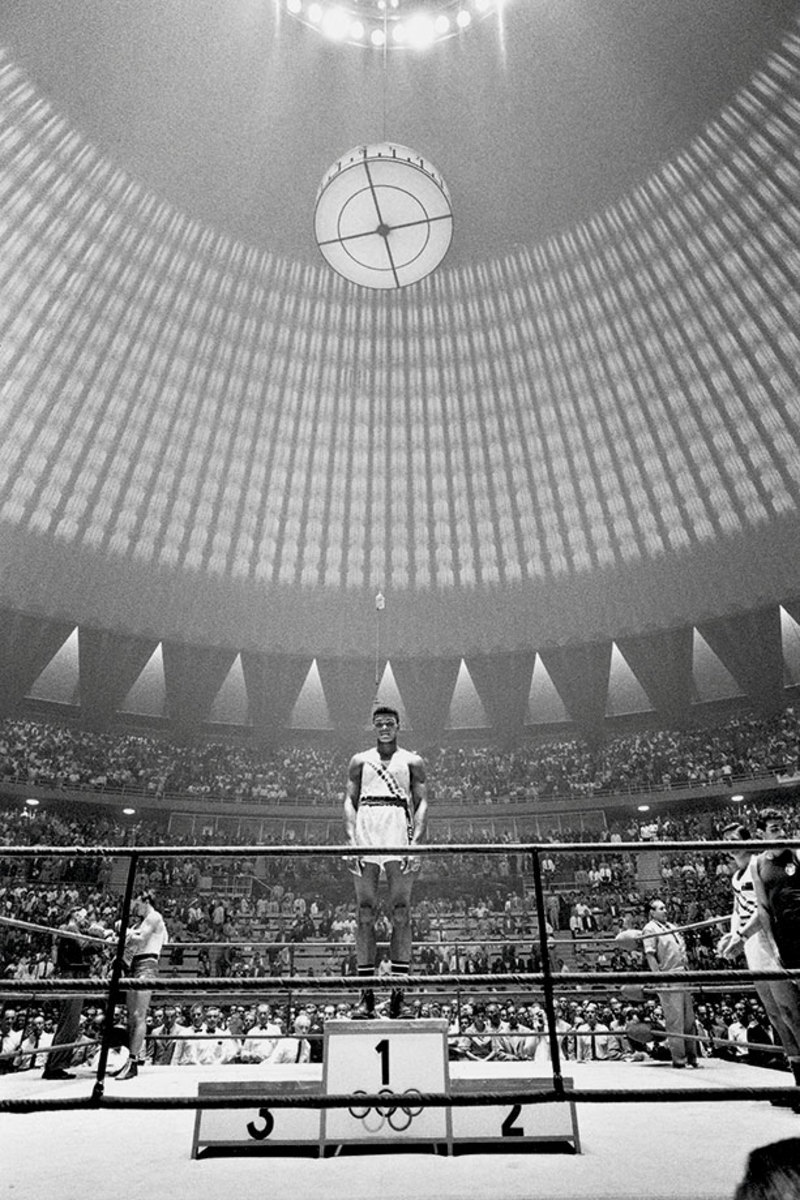

For the 18-year-old from Louisville, here atop the medal stand after his Olympic victory, all roads led from Rome. Clay finished his amateur career with a record of 100-5 and made his professional debut two months after the Games.

Undefeated in his first 17 pro fights, Clay mugged for the camera before the start of his 1963 bout against Doug Jones in Madison Square Garden.

Trainer Angelo Dundee urged his young charge to get serious before the opening bell against Jones. Clay followed instructions and emerged from a tough fight with a unanimous decision victory. Three months later he would stop Henry Cooper and close out 1963 at 19-0.

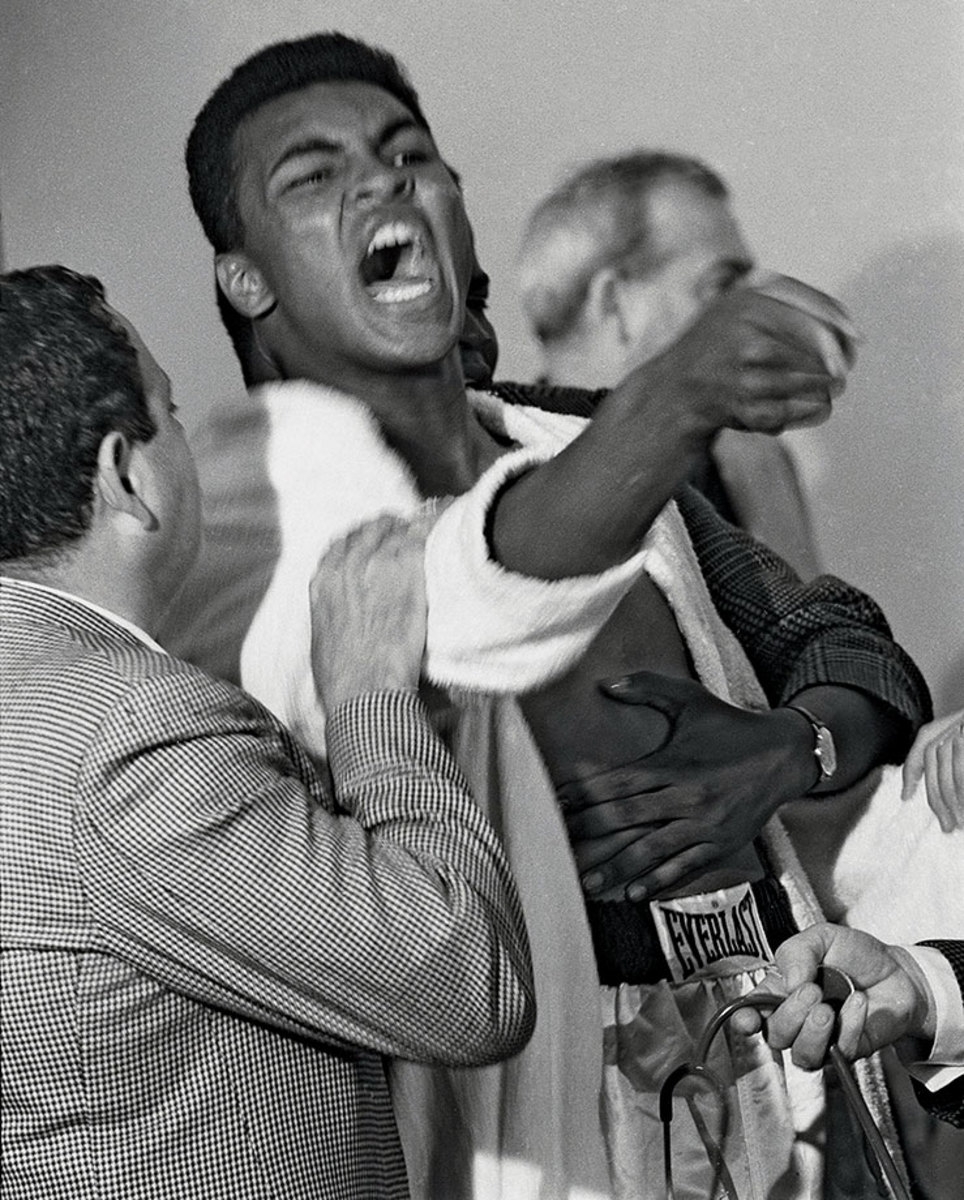

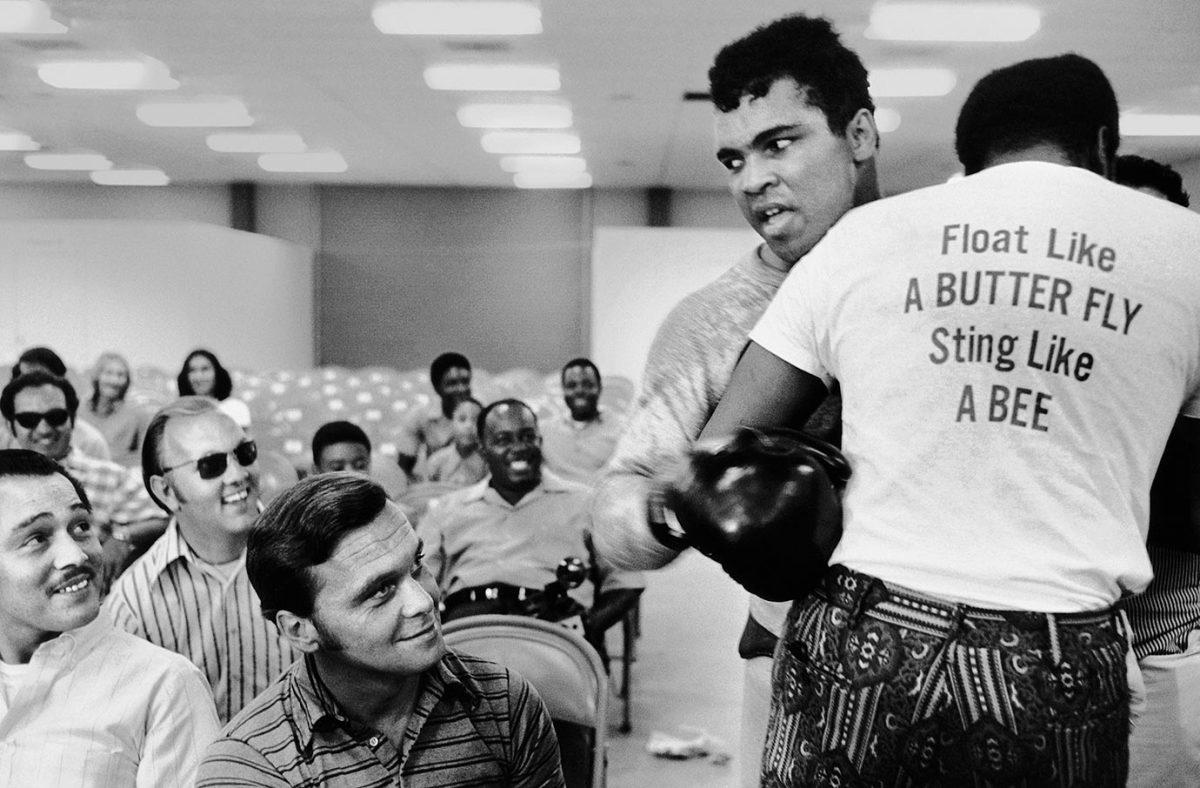

A seemingly hysterical Clay taunted Sonny Liston during the pre-fight physical for their 1964 bout. He had consistently baited the Big Bear during the lead-up to the fight, saying he was going to "use him as a bearskin rug ... after I whup him." The Miami Boxing Commission would fine Clay $2,500 for his outburst at the physical.

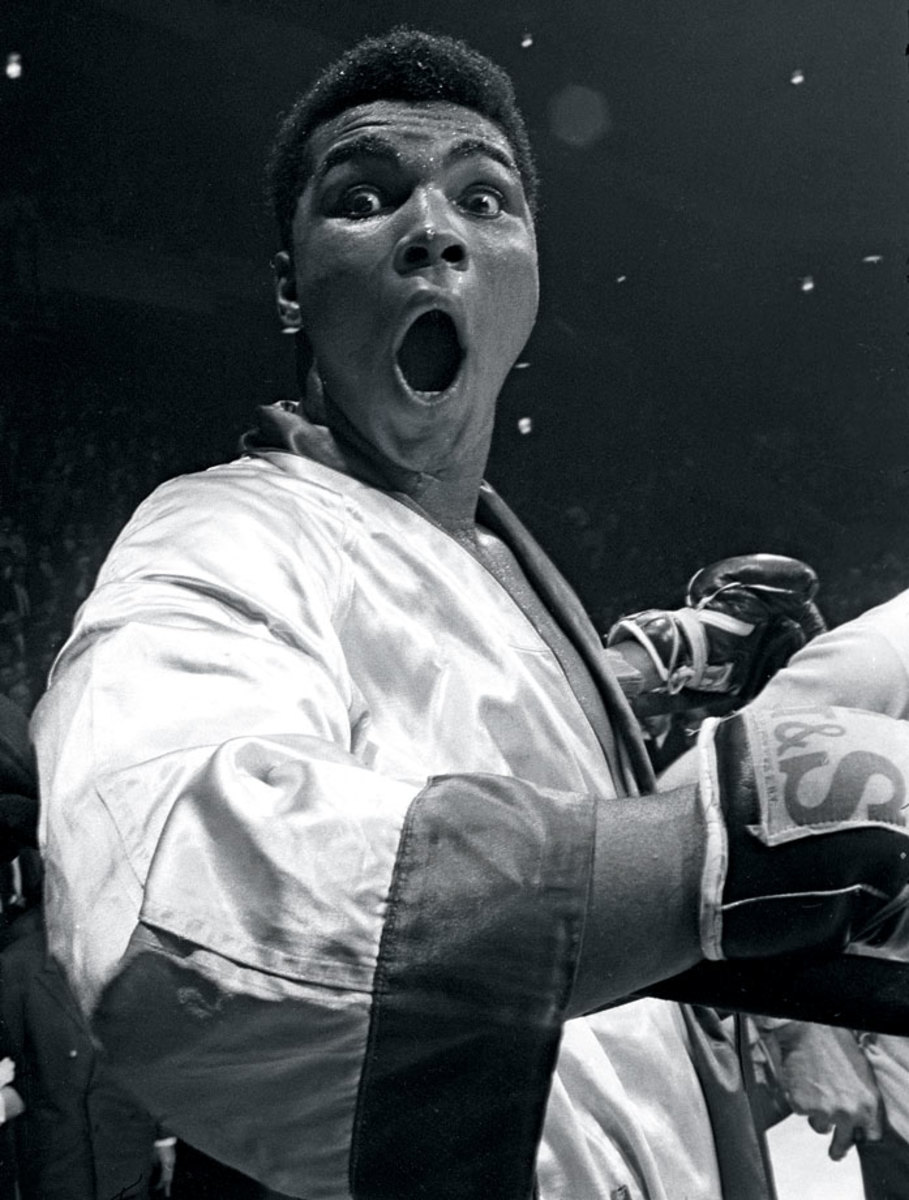

"I shook up the world!" an emotional Clay hollered to ringside reporters after his shocking defeat of Liston. And he did just that, claiming the heavyweight title at age 21 after a clearly beaten Liston, complaining of a shoulder injury, failed to answer the bell for the seventh round.

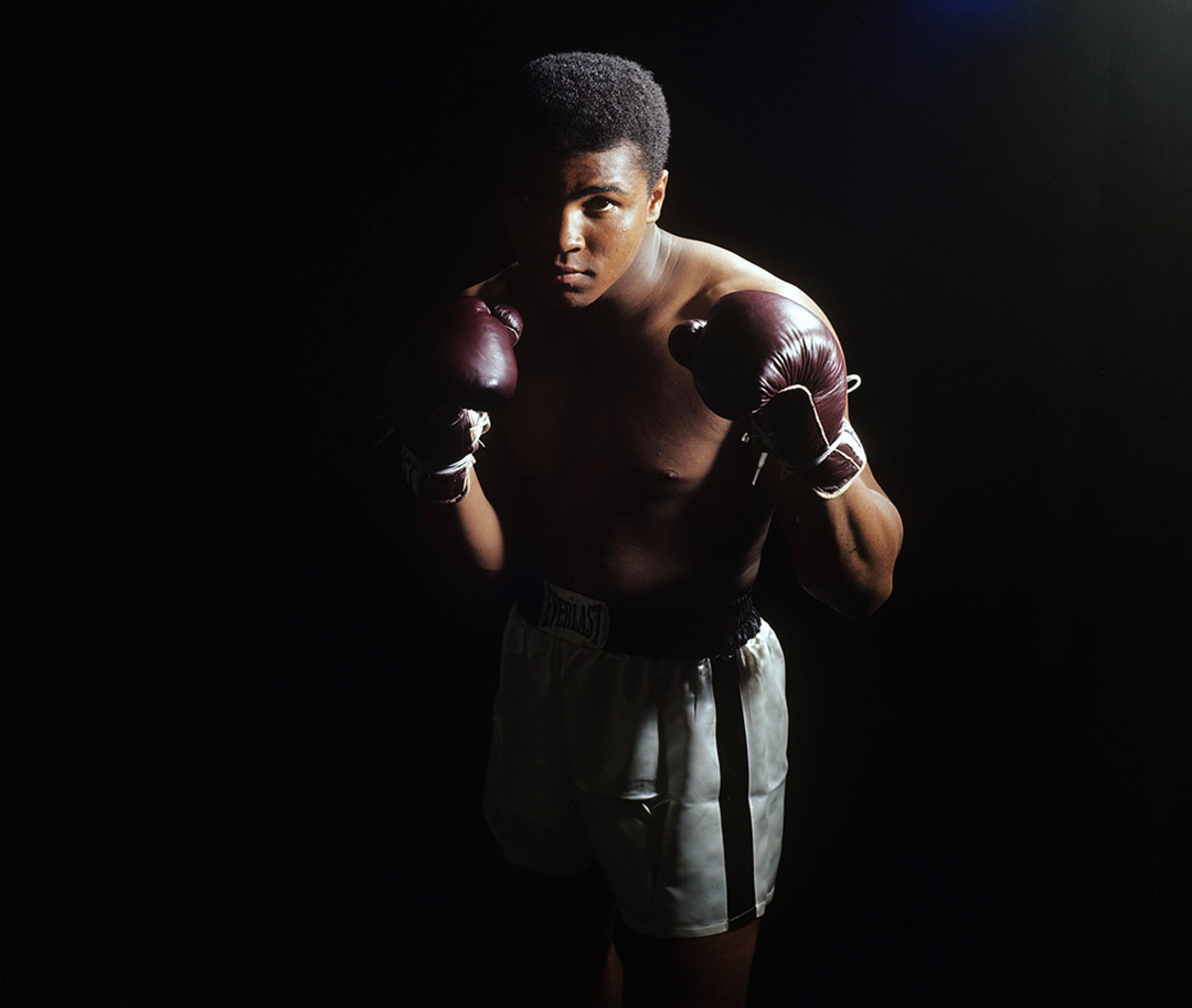

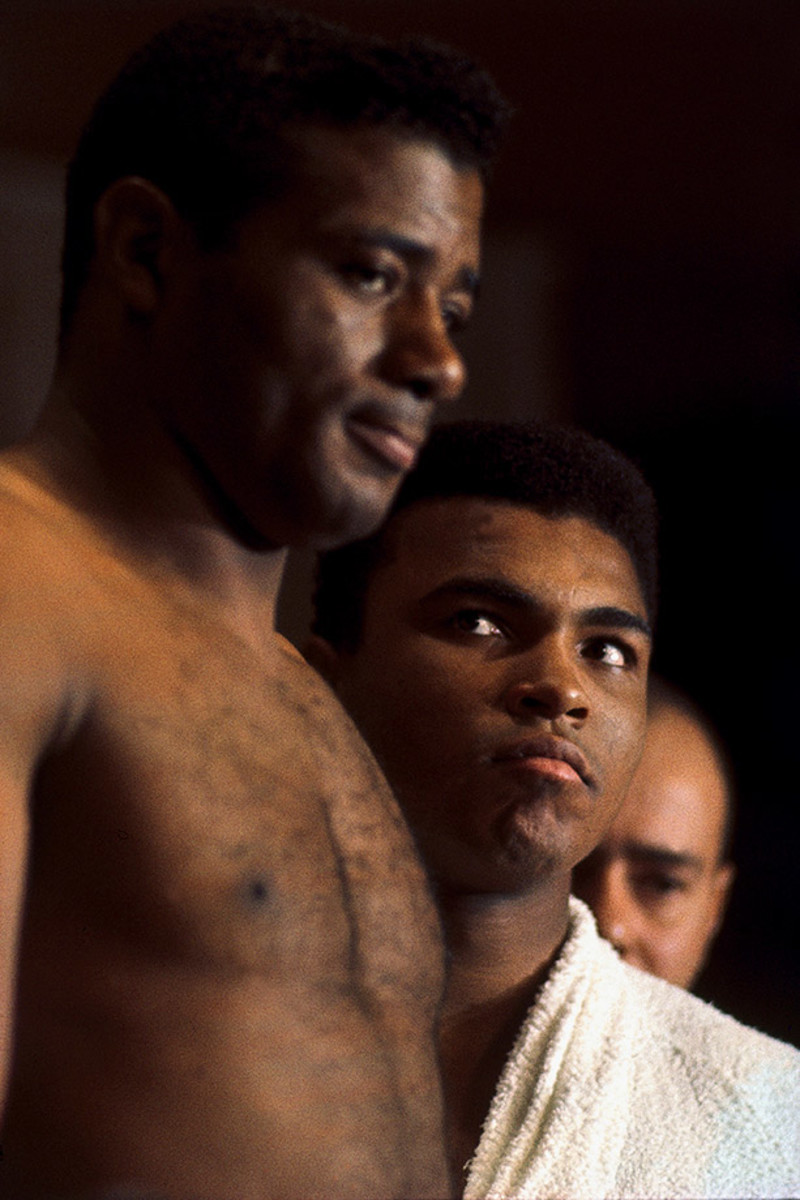

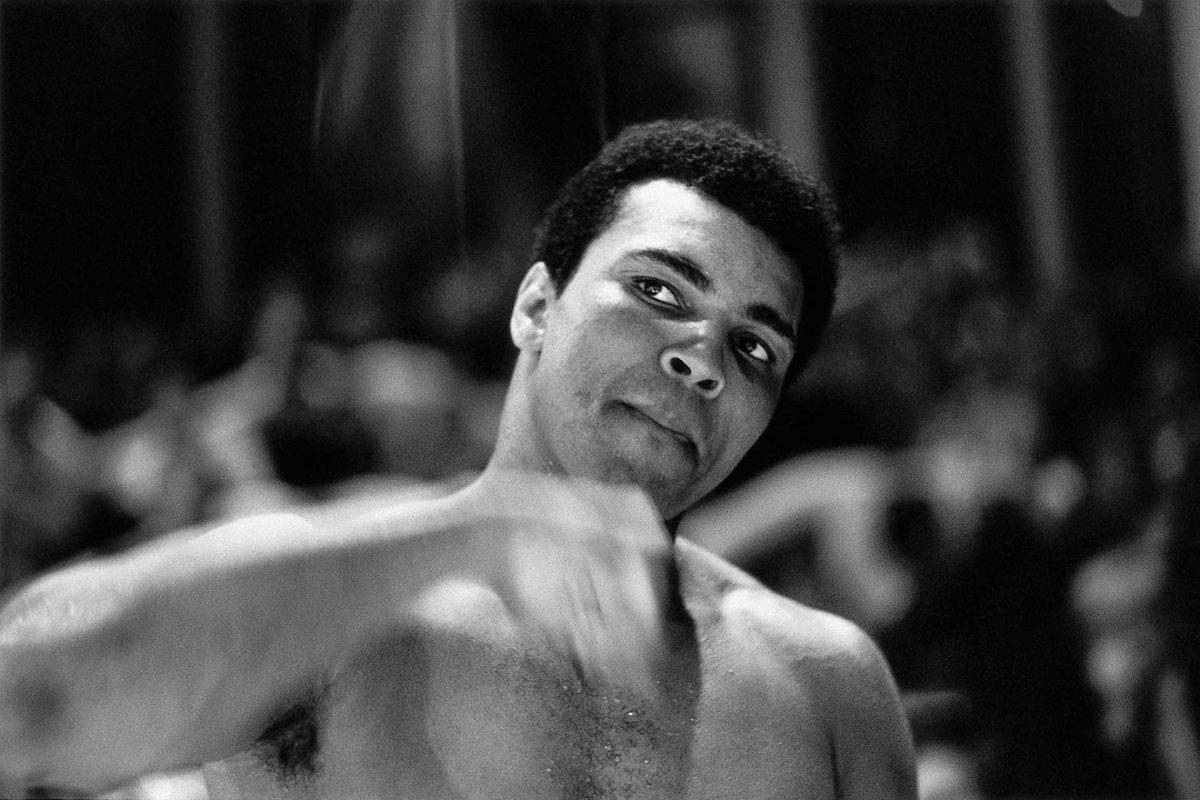

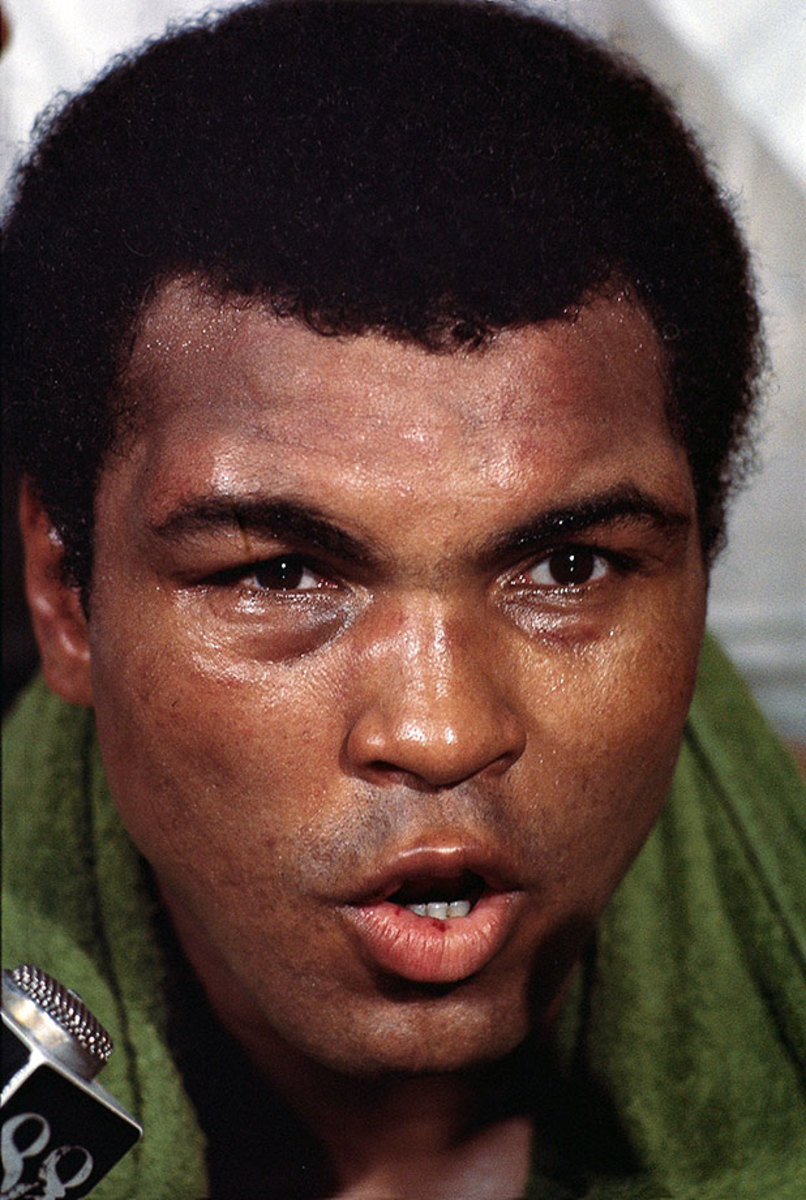

Draped in shadow, the young king — now known as Muhammad Ali — stared down the camera during a photo shoot in April 1965, one month before his rematch against Sonny Liston.

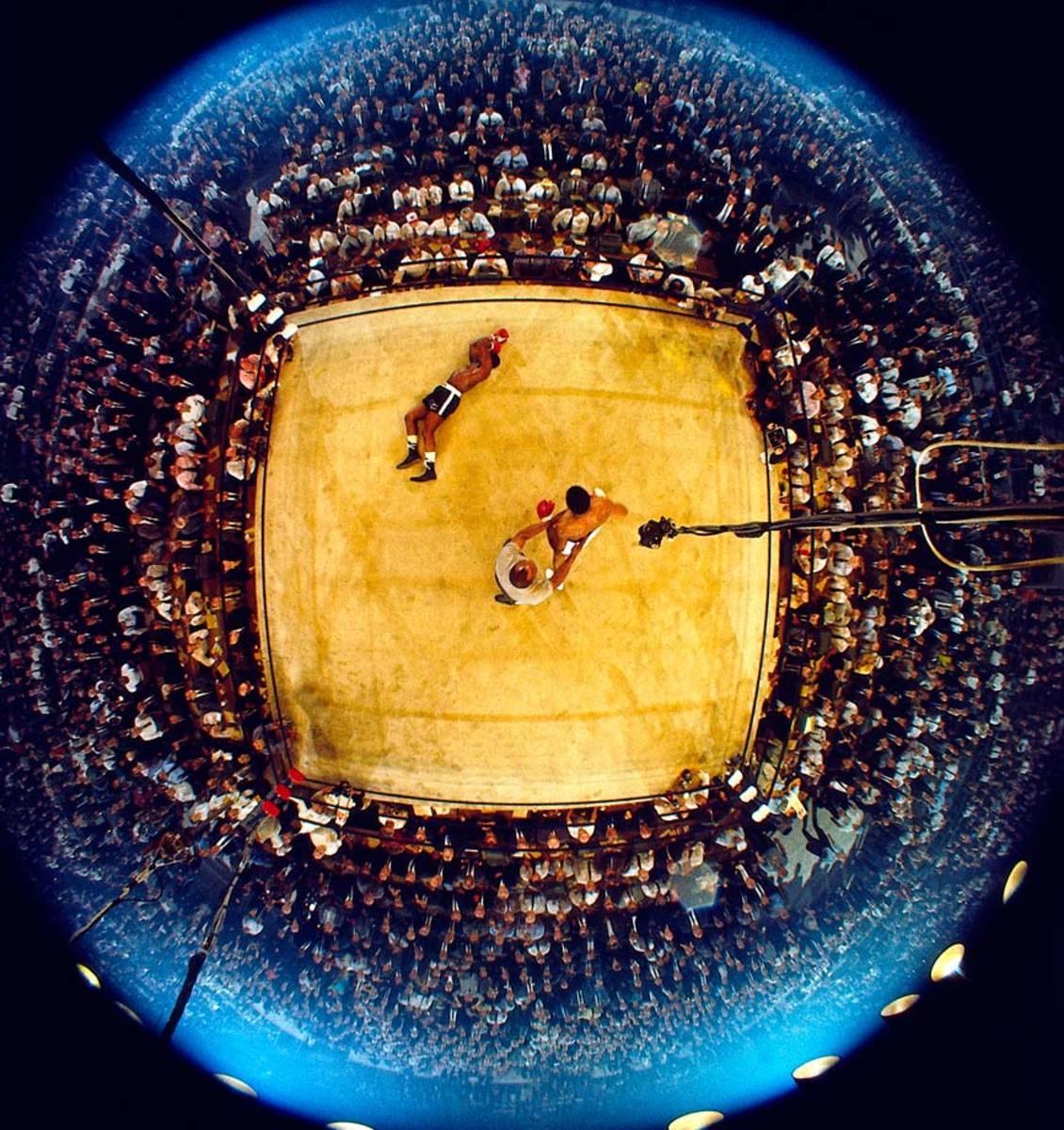

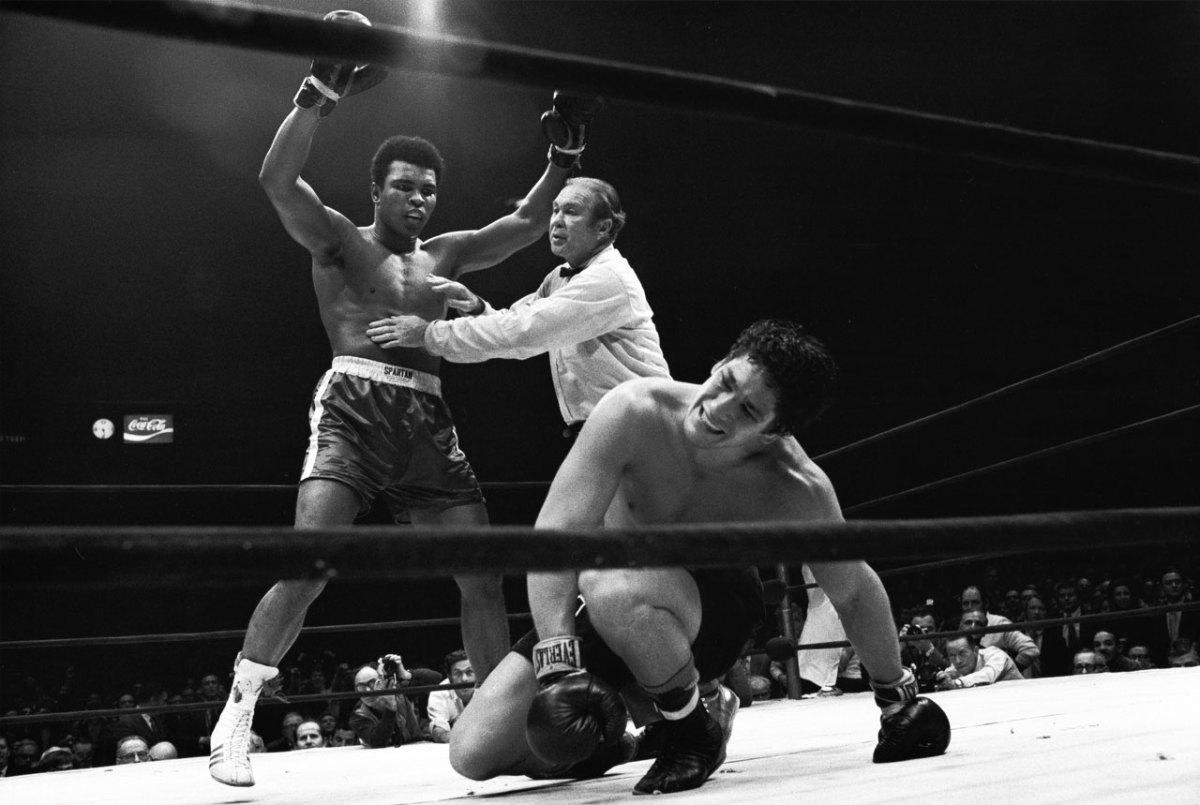

As Liston lingered on the canvas and the referee, former heavyweight champ Jersey Joe Walcott, tried to control Ali, the 2,434 spectators on hand in the Lewiston, Me., hockey arena — a record low for a heavyweight championship fight — tried to make sense of what all that had happened in less than two minutes after the opening bell.

The celebration over Liston continued. In a chaotic ending, Ali was awarded a knockout when Nat Fleischer, publisher of The Ring, informed referee Jersey Joe Walcott from ringside that Liston had been on the canvas for longer than 10 seconds after Ali knocked him down. The bout remains one of the most controversial in boxing history, with many observers insisting that Liston took a dive.

Ali's second title defense came in November 1965, against former two-time heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. During the build-up to the bout, the normally soft-spoken Patterson earned the new champ's wrath by refusing to call Ali by his Muslim name. At the weigh-in, Ali's glare made it clear that he intended Patterson to pay for the disrespect.

In cruelly efficient performance, Ali punished Patterson — who was hobbled by a painful back injury — seemingly toying with the former champ throughout the bout, hitting him at will and calling, "What's my name?" before finally winning on a 12th-round TKO.

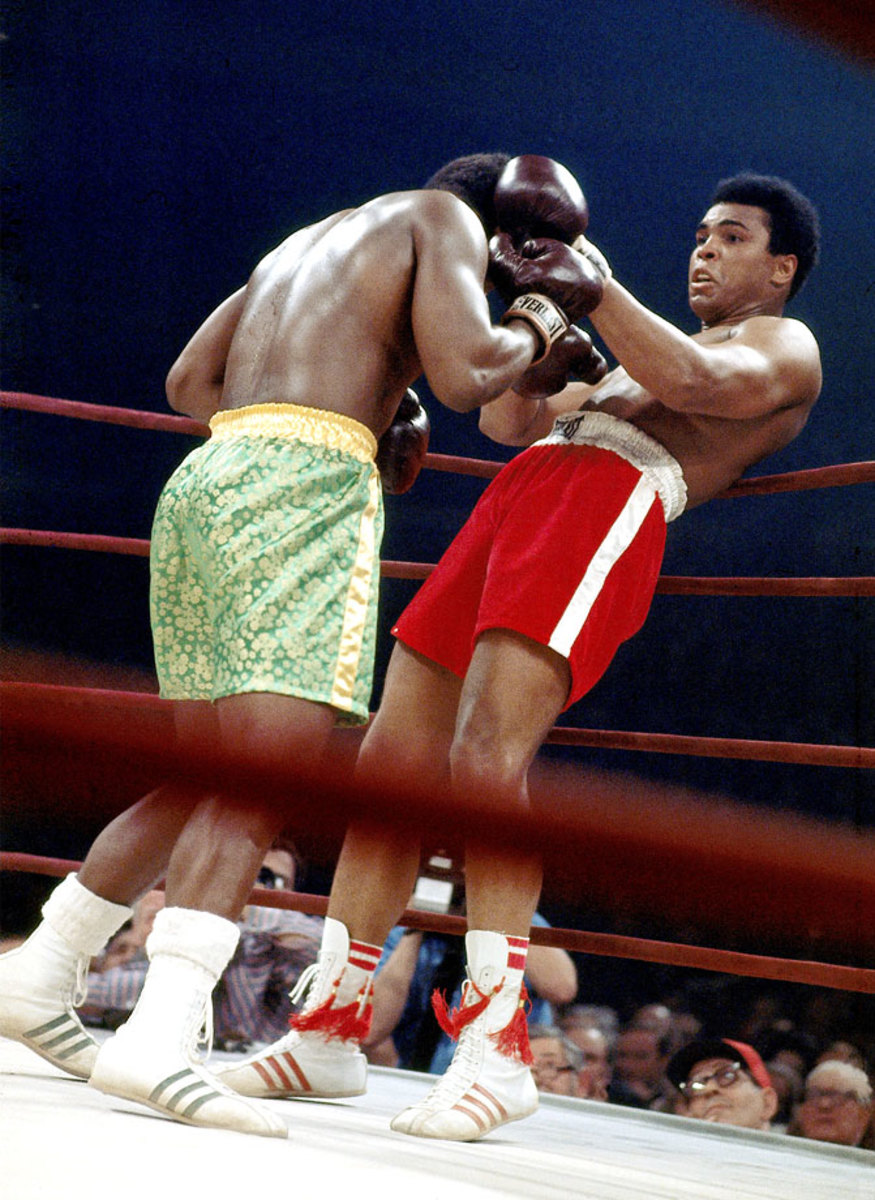

Capping off a five-fight campaign in 1966, Ali faced Cleveland Williams in the Houston Astrodome on Nov. 14. Known as the Big Cat, the heavily-muscled Williams was a power puncher who had racked up 51 knockouts in 71 fights. But he was also 33, barely recovered from a gunshot wound sustained the year before, and up against a young champion very much in his prime. Ali wasted little time in unleashing a withering attack.

Float and sting: In a display of speed and combination punching unmatched in heavyweight history, Ali overwhelmed Williams from the start. The challenger, here down for the third time in round 2, would be saved by the bell before referee Harry Kessler could count him out, but it would only postpone the inevitable.

Ali dropped Williams again early in the third round, and Kessler waved the mismatch over at 1:08 of the third.

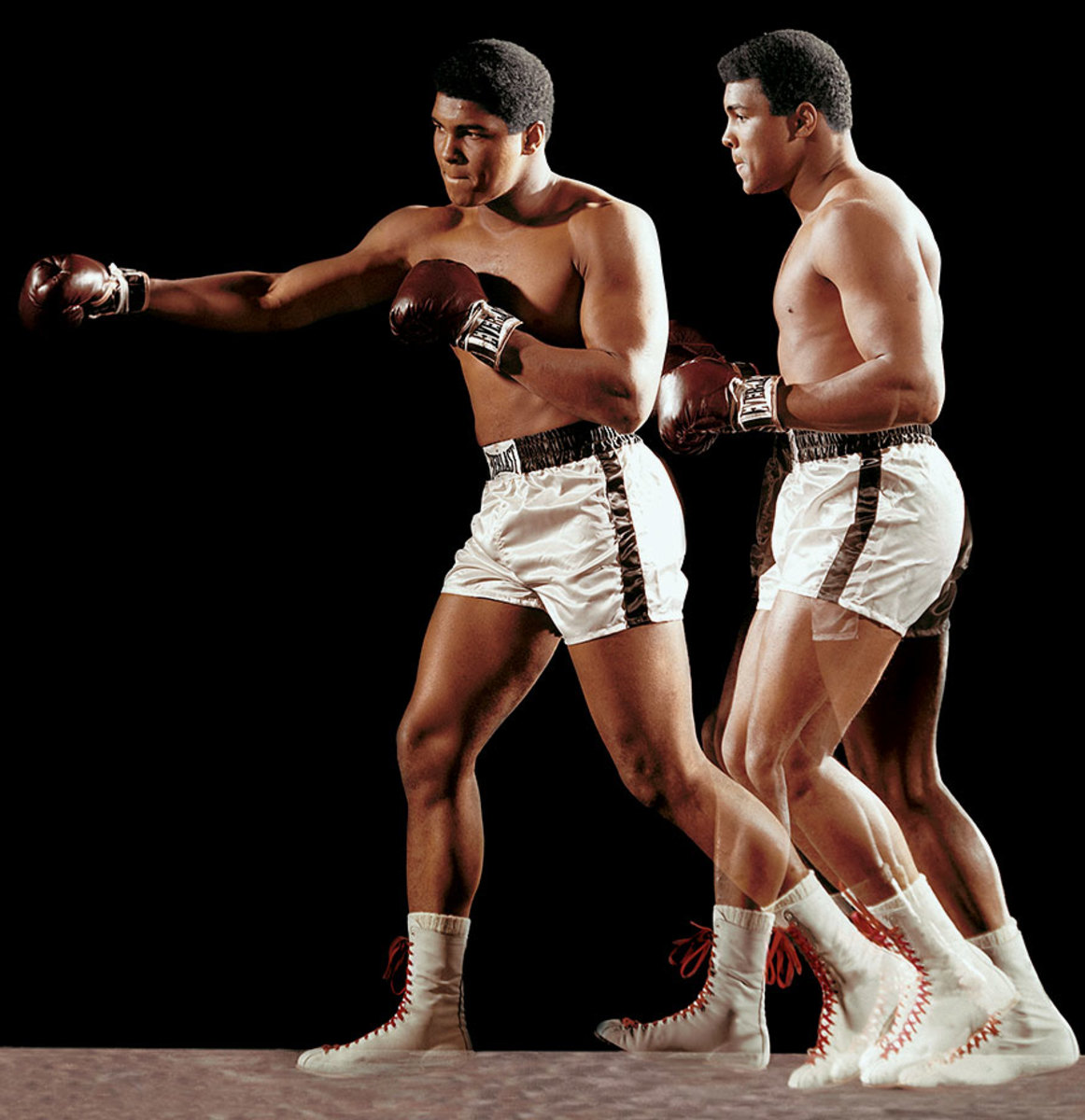

In a multiple-exposure portrait, Ali demonstrates his signature double-clutch shuffle during a photo shoot in December 1966.

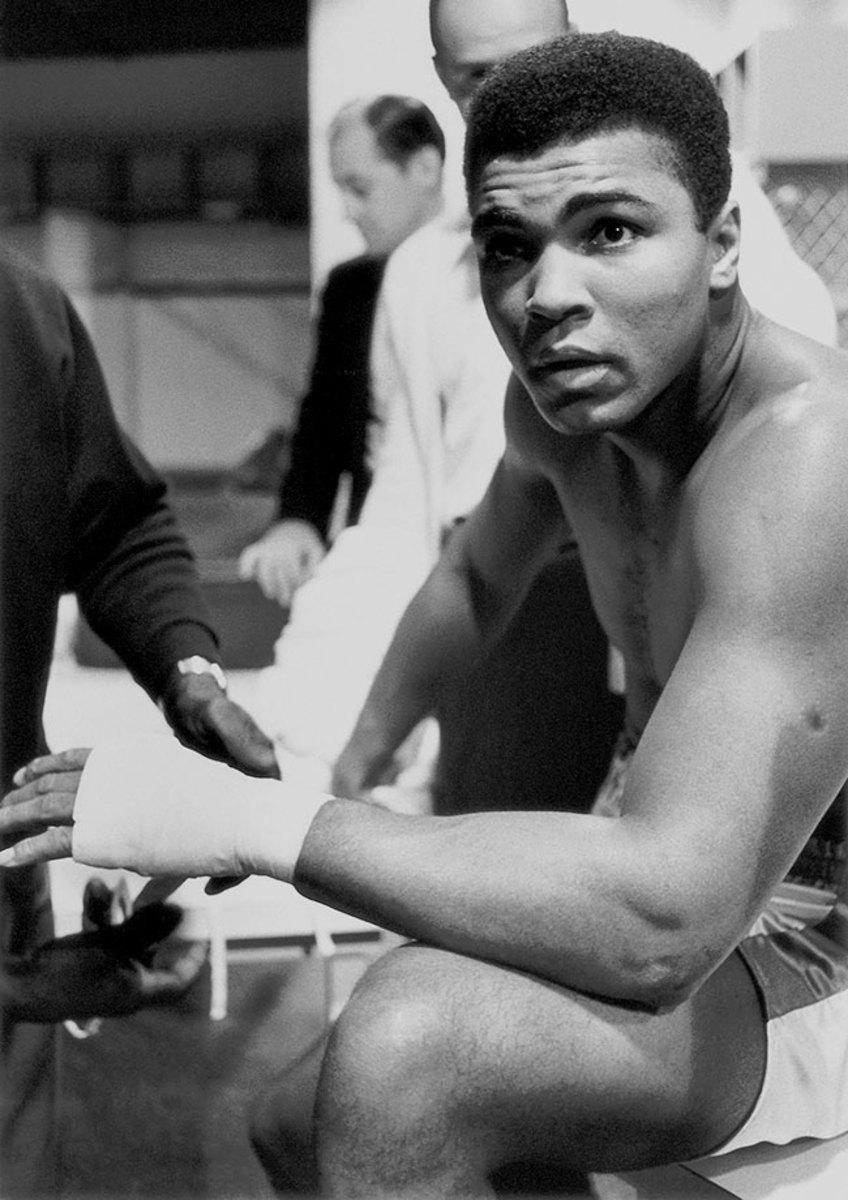

Ali sits in the locker room before his February 1967 fight against Ernie Terrell. Like Patterson before him, Terrell refused to call the champion by his Muslim name. Also like Patterson, he paid a stiff price, as Ali punished Terrell for 15 ugly rounds before winning by unanimous decision.

Outside the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in Houston in April 1967, Ali spoke to the press about his refusal to be inducted into military service. Among those on hand was ABC's Howard Cosell, who would be a staunch supporter of the fighter's stance. The decision cost Ali his boxing license and his heavyweight title, and he was sentenced to five years in prison but remained free pending an appeal.

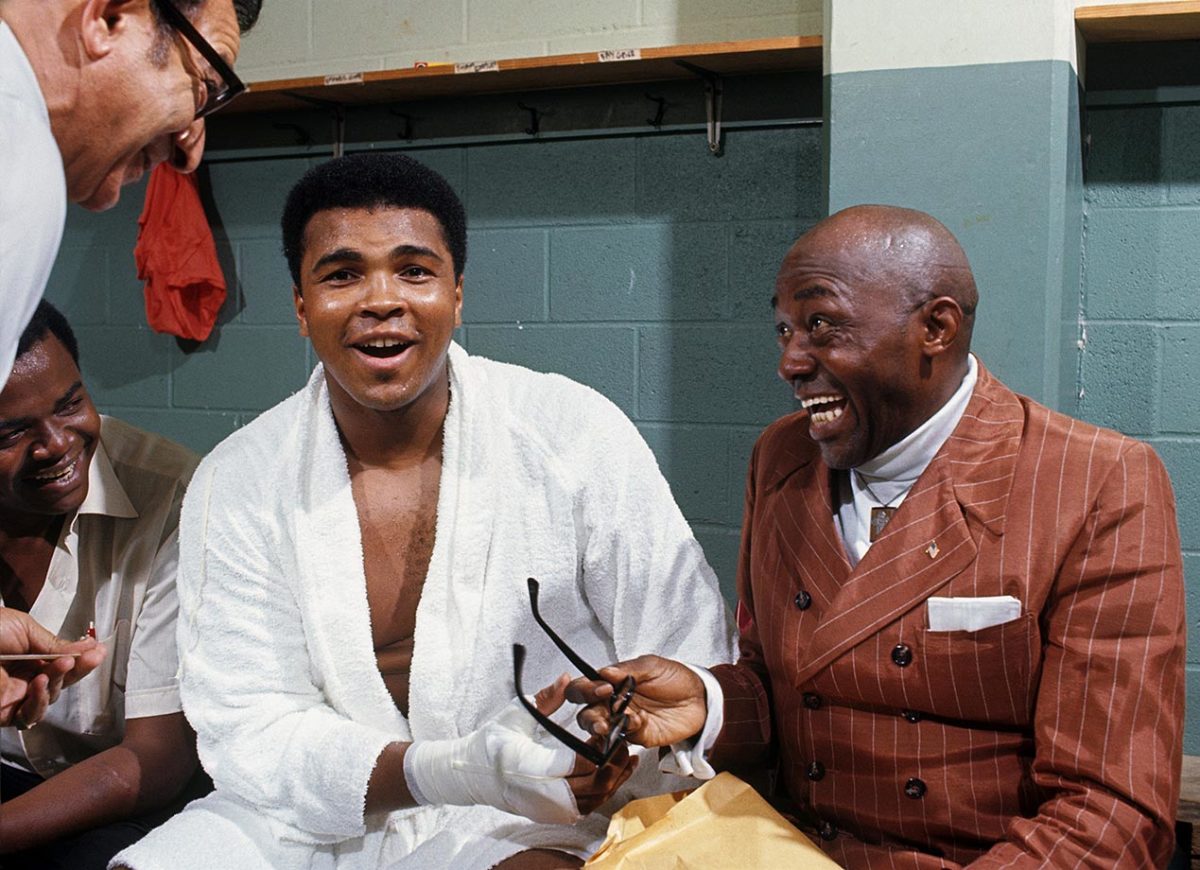

In professional exile for three and a half years because of his draft case, Ali sought to return to boxing in 1970. He began with a night of exhibition bouts at Morehouse College in Atlanta, where before going into the ring, he shared a locker room laugh with actor and comedian Lincoln Perry (right), better known by his stage name of Stepin Fetchit. The friendship between the two black icons would later be examined in an acclaimed play by Will Power, Fetch Clay, Make Man.

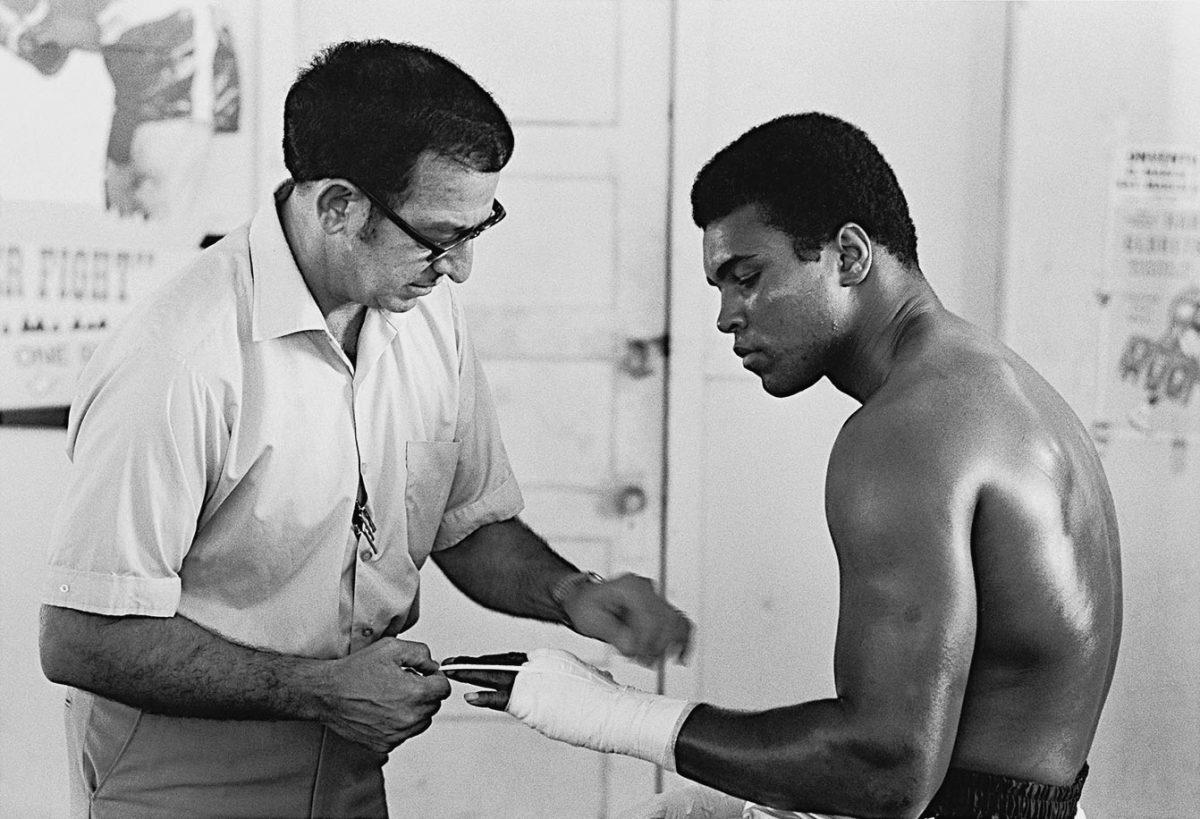

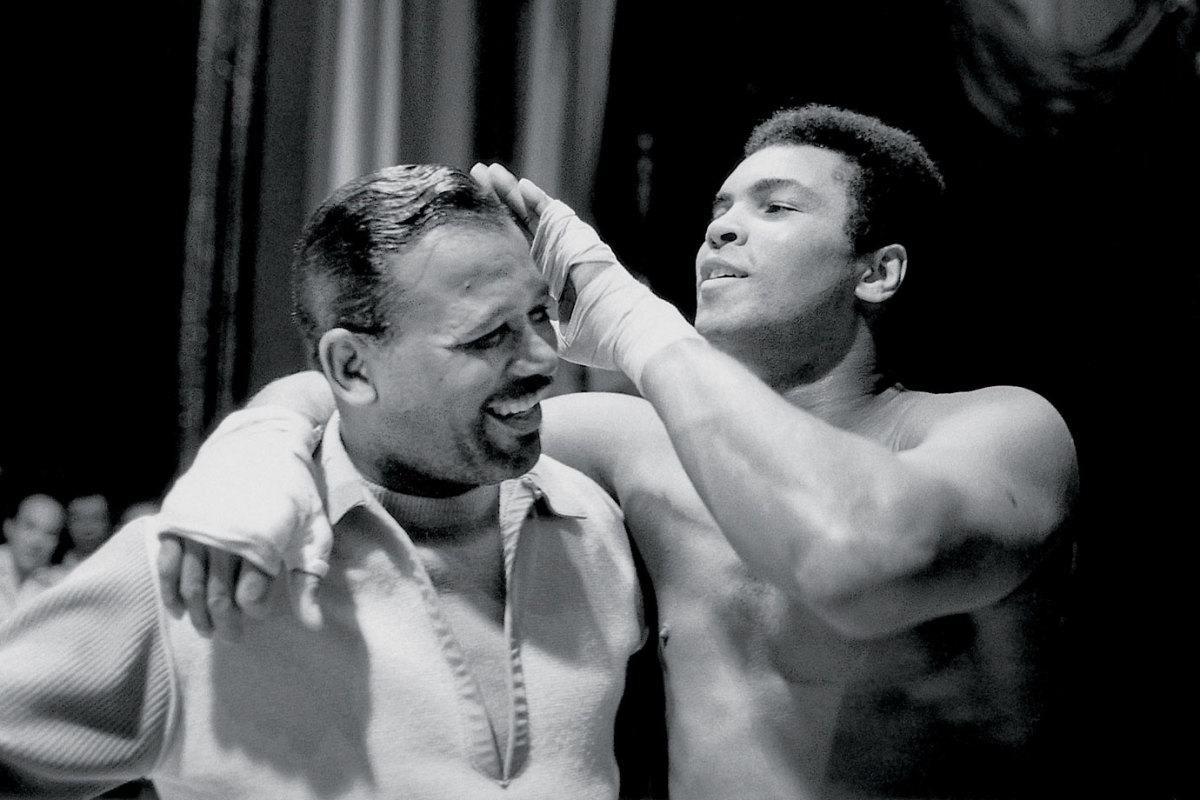

After the Atlanta Athletic Commission at last granted Ali a license, the deposed champion went back into serious training. He was, as ever, in the capable hands of trainer Angelo Dundee, here wrapping boxing's most famous fists at the 5th Street Gym in Miami in October 1970.

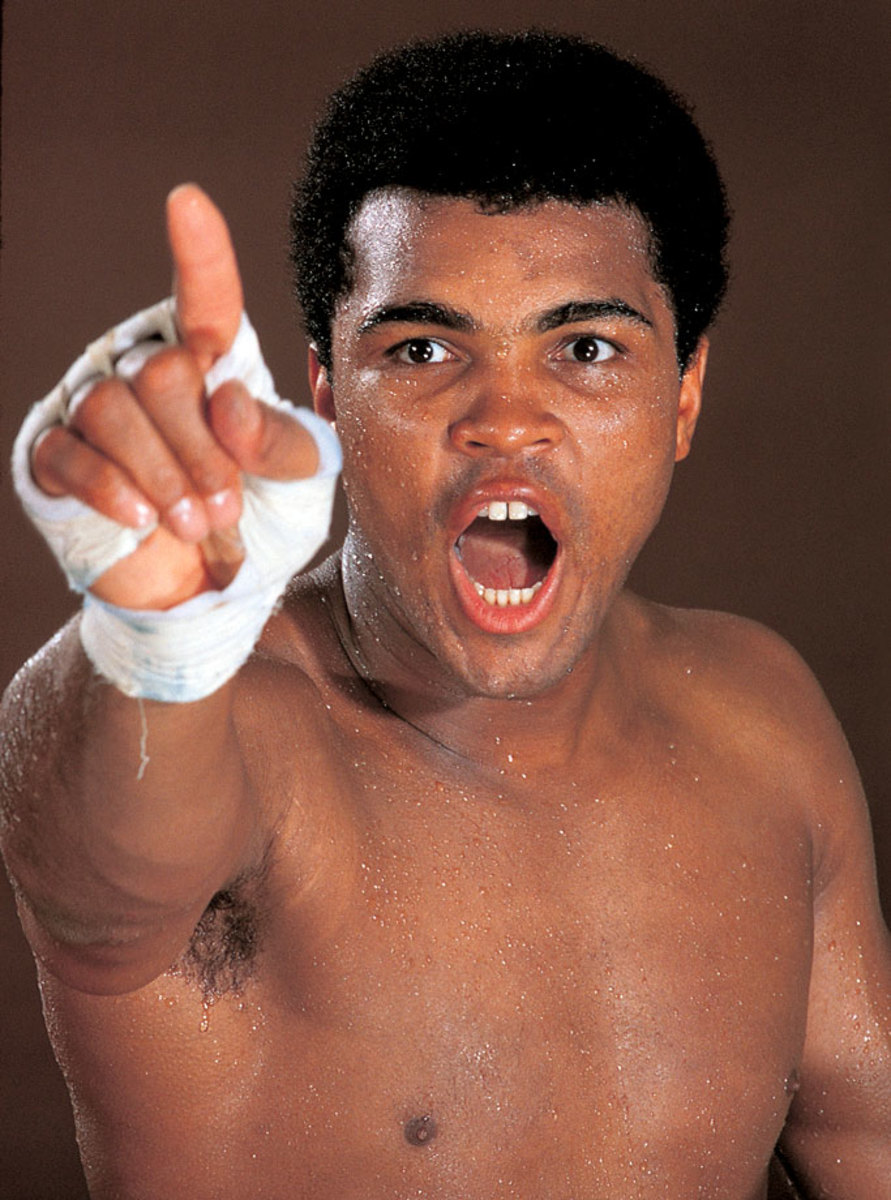

With his return to the ring scheduled for Oct. 26, 1970 in Atlanta, against dangerous contender Jerry Quarry, Ali made it clear to all who would listen that he was on a mission to reclaim the title that had been stripped of him.

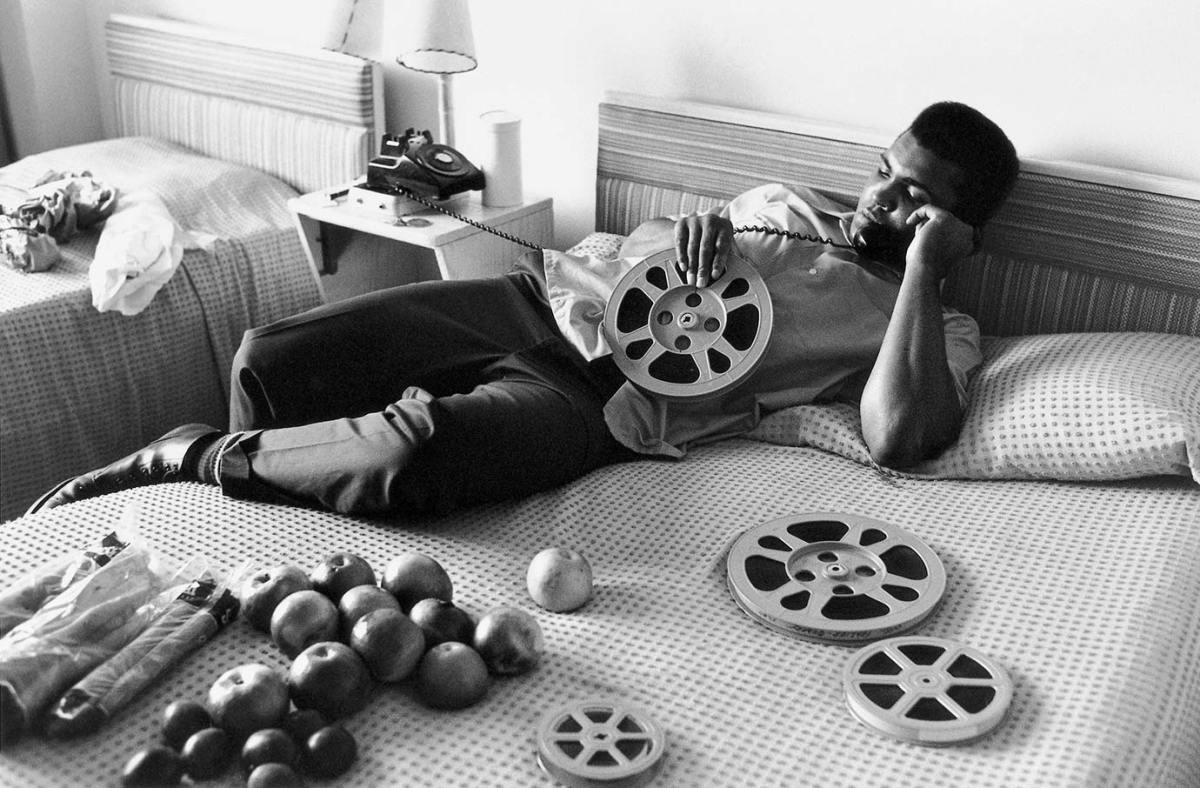

Reel to spiel: For the ever-loquacious Ali, even a rare moment of down time — like this afternoon in 1970 in a Miami hotel room — was a chance to do some talking.

Despite Ali's long layoff, his comeback campaign would include no easy tune-up bouts. He stopped Quarry in three rounds on Oct. 26, 1970, then, just six weeks later — an unthinkably short interlude by today's standards — took on Argentine contender Oscar Bonavena in Madison Square Garden. Here, Ali fires a right at the rugged and awkward Bonavena, who took the fight to the former champion all night.

After a long, often sloppy bout, Ali — here being held back by referee Mark Conn — produced one of the most dramatic finishes of his career, dropping Bonavena three times in the 15th and final round to automatically end the fight. The win cleared the way for a showdown with Joe Frazier, the man who had taken the heavyweight title in Ali's absence.

On the night of March 8, 1971, the eyes of the world were on a square patch of white canvas in the center of Madison Square Garden. There, Ali and Joe Frazier met in what was billed at the time simply as The Fight, but has come to be known, justifiably, as the Fight of the Century. For 15 rounds the two undefeated heavyweights battled at a furious pace, with each man sustaining tremendous punishment. In the end Frazier prevailed, dropping Ali in the final round with a tremendous left hook to seal a unanimous decision and hand The Greatest his first loss in 32 professional fights.

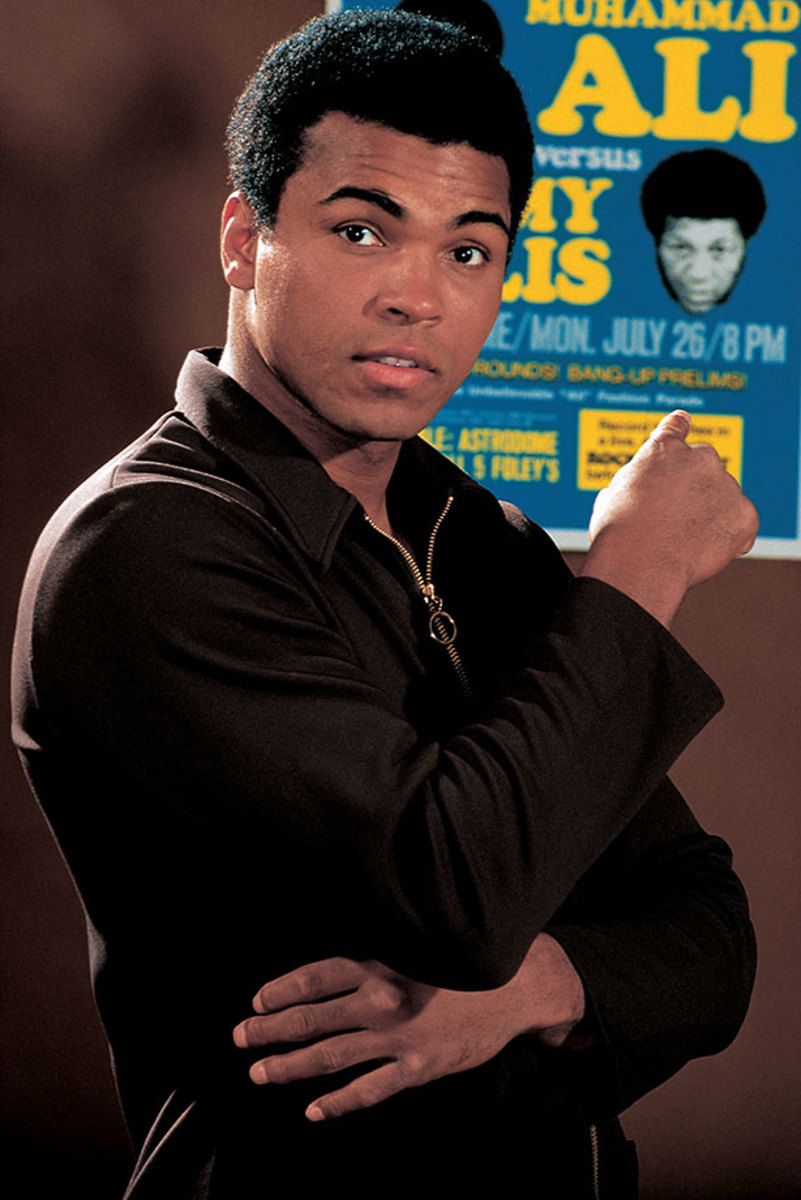

Ali poses with the fight poster for his upcoming fight against Jimmy Ellis during a photo shoot in July 1971. Ellis was an old friend of Ali's — both were trained by Angelo Dundee — and knew his fighting style well from many rounds of sparring.

For those sportswriters lucky enough to cover Ali on a regular basis, each day brought surprises and, more often than not, plenty of laughs. of Trainer Drew Bundini Brown helps Ali train for his fight against Ellis. Ali won the bout by technical knockout in the 12th round to claim the vacant NABF heavyweight title.

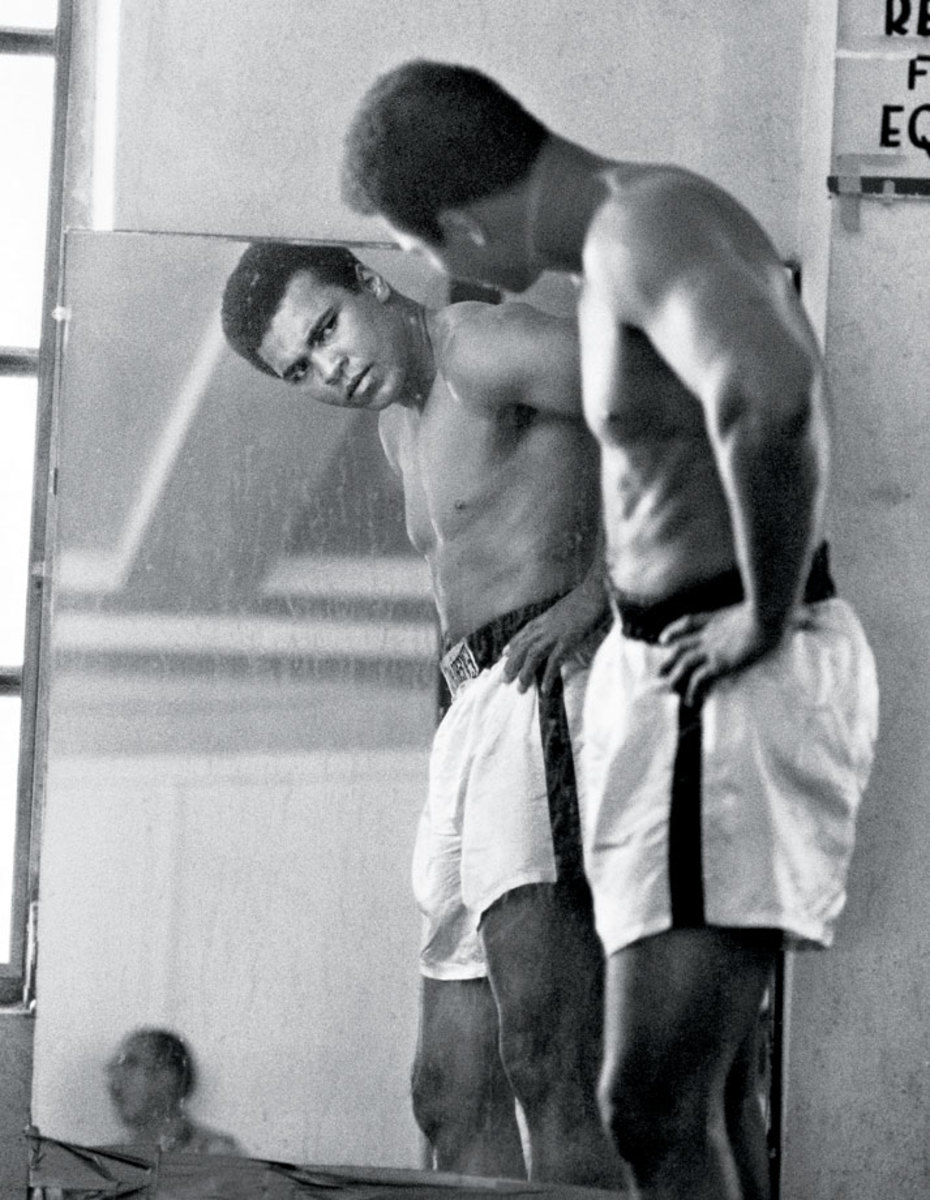

The man in the mirror stares back as Ali examines himself while training for a fight in 1972. He won all six of his fights that year.

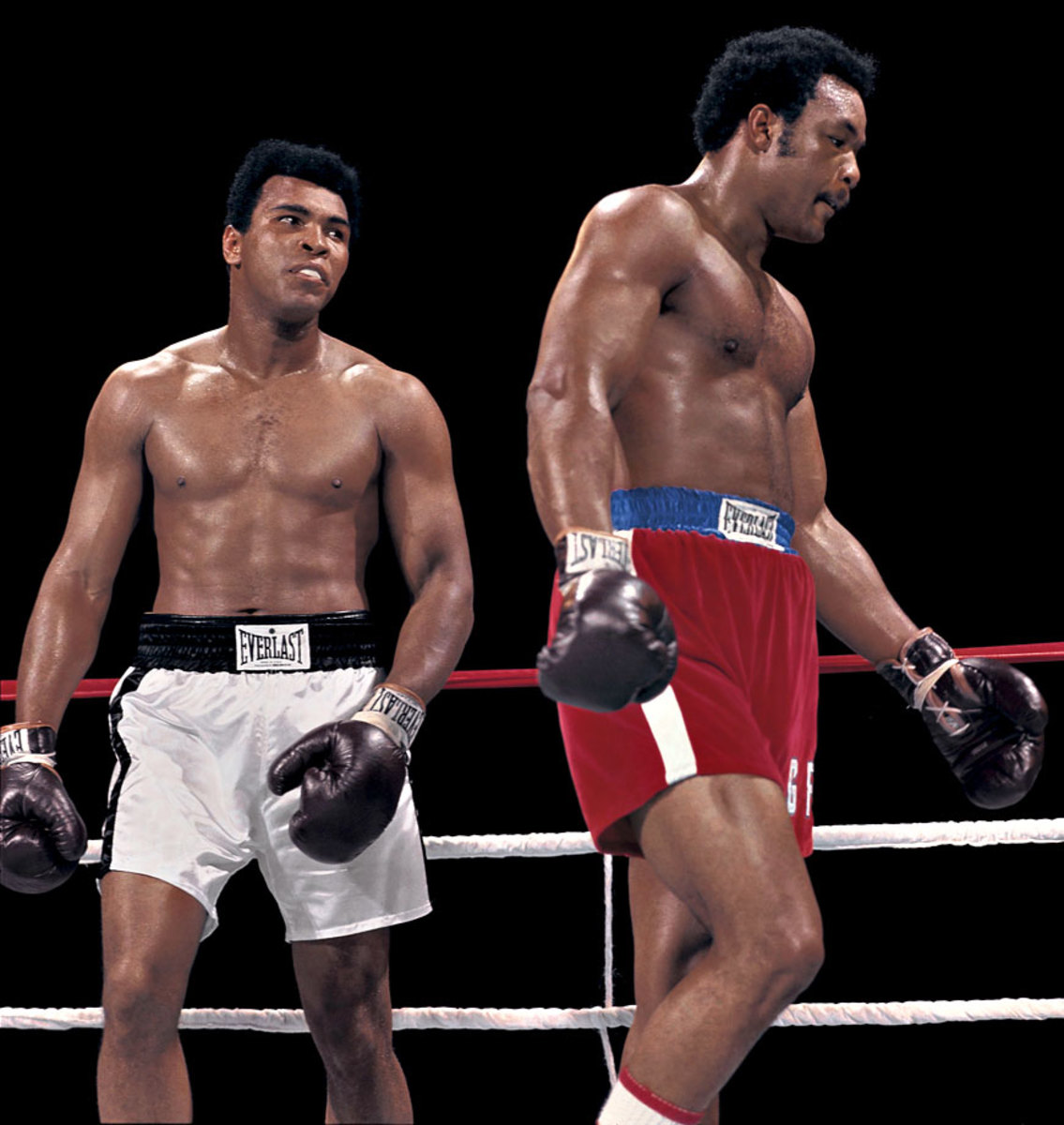

The Louisville Lip stands next to George Foreman before Ali's fight versus Jerry Quarry in June 1972. Ali won by technical knockout in the seventh round. Foreman at the time was 36-0. Ali would not get his shot against Foreman for more than two years.

Ali throws a left hook at Bob Foster in their 1972 fight at Stateline, Nev. Although Ali knocked Foster out, Foster did leave his mark: a cut above Ali's left eye, his first as a professional.

Foster lies on the canvas after getting knocked down by Ali. Ali knocked Foster down four times in the fifth round and twice more in the seventh round before he was finally counted out after Ali knocked him down again in the eighth round.

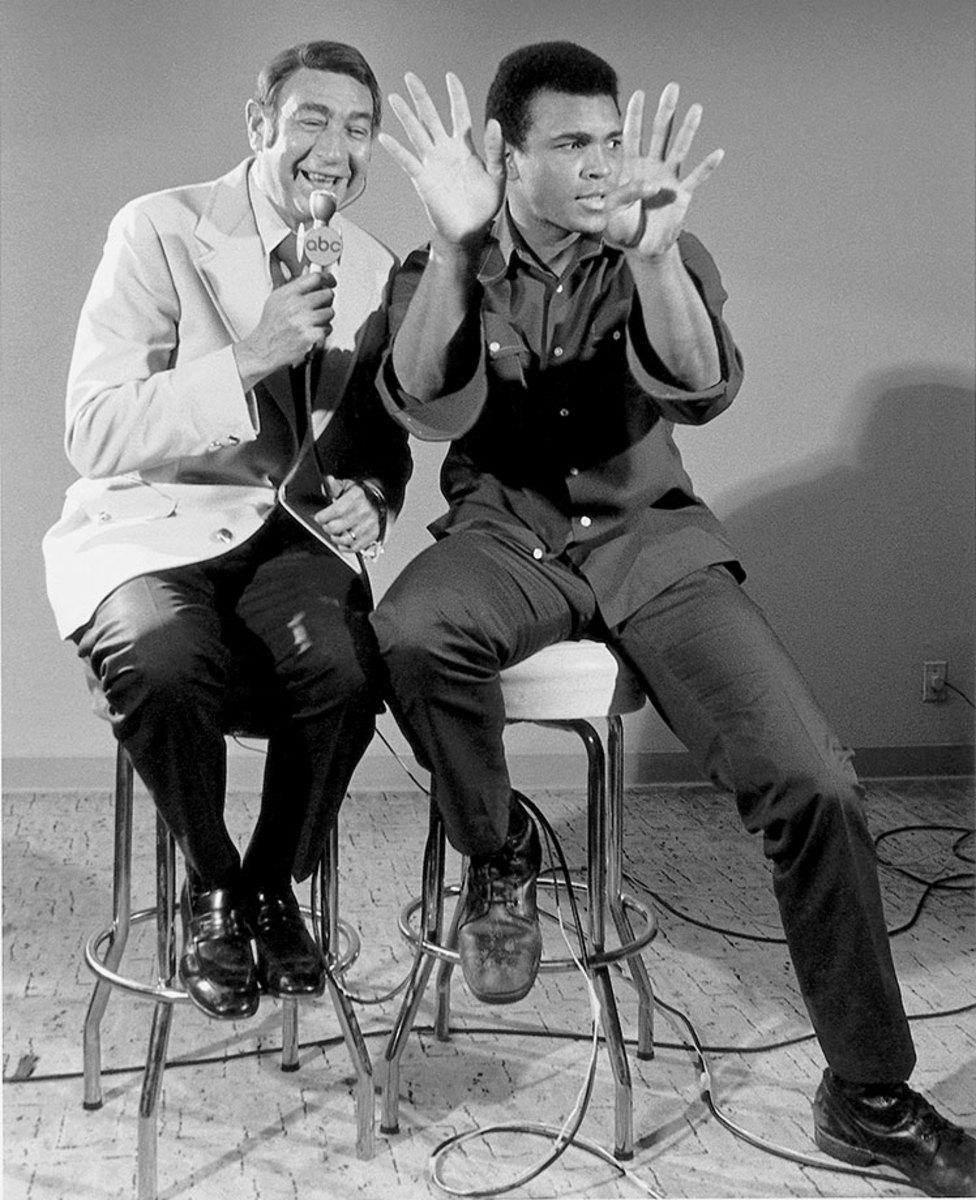

Ali sits with sportscaster Howard Cosell before his fight with Joe Bugner in February 1973. Although unable to knock Bugner out, Ali won comfortably by unanimous decision.

Ali hits a speed bag while warming up for his bout with Bugner in Las Vegas. Ali prepared ferociously for the fight, training 67 rounds the week leading up to the fight, including six rounds the day before the fight.

In a lighter pre-fight moment, Ali poses for a portrait wearing a hat in his dressing room before the match with Bugner.

Ali plays with Sugar Ray Robinson's hair in the locker room before his bout with Bugner. The former welterweight and middleweight champion was Ali's childhood idol.

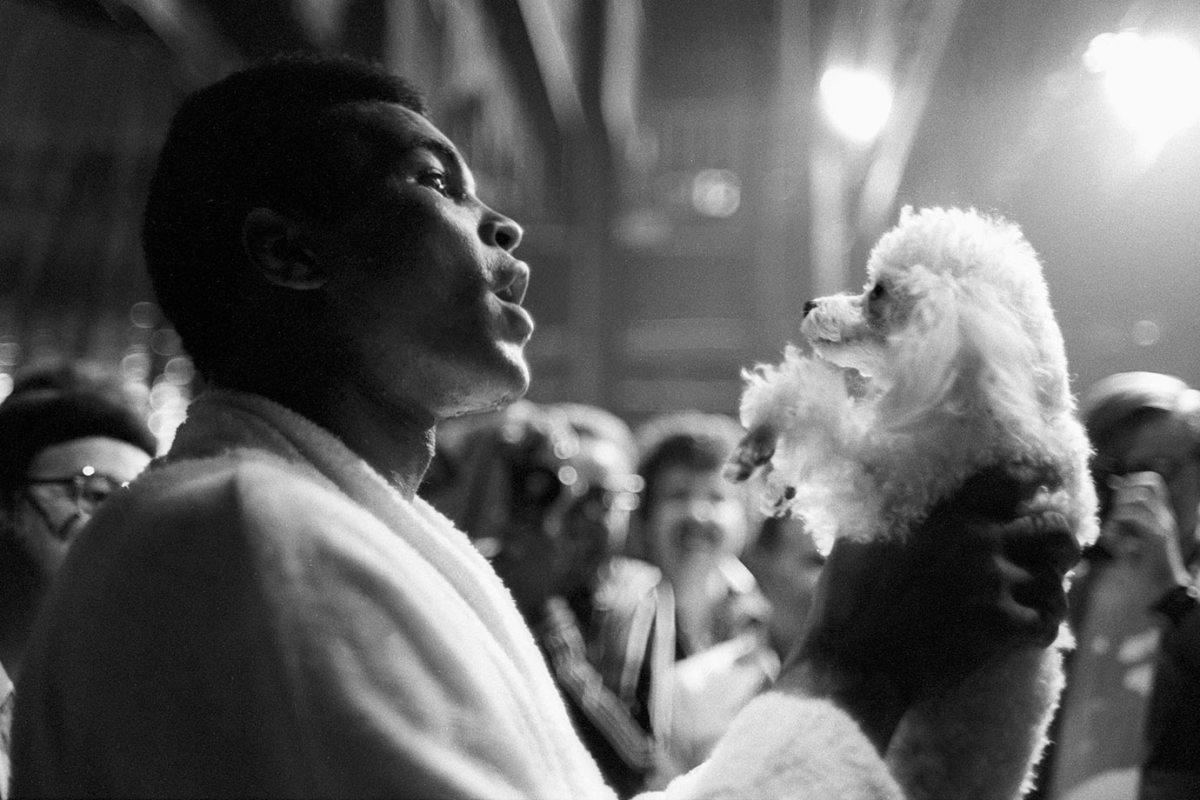

Before the fight with Bugner, Muhammad Ali enjoys a relaxed moment with a poodle at Caesars Palace Hotel. He won the fight with Bugner by unanimous decision.

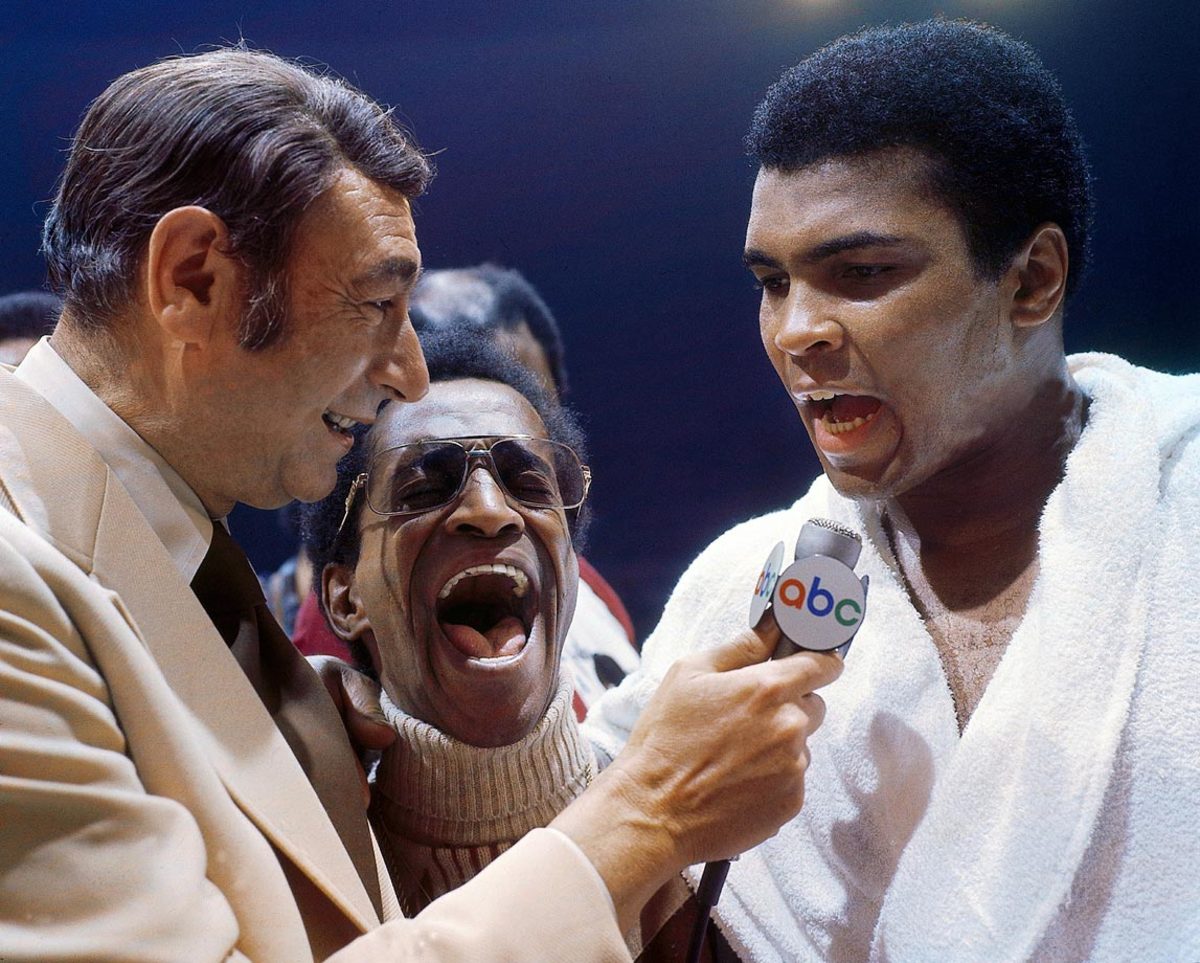

Howard Cosell interviews Ali, with entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. in the middle, after his victory over Joe Bugner by unanimous decision in. Although the fight was never in jeopardy of getting away from him, Ali praised Bugner's legs and said he could be a champion in a few years.

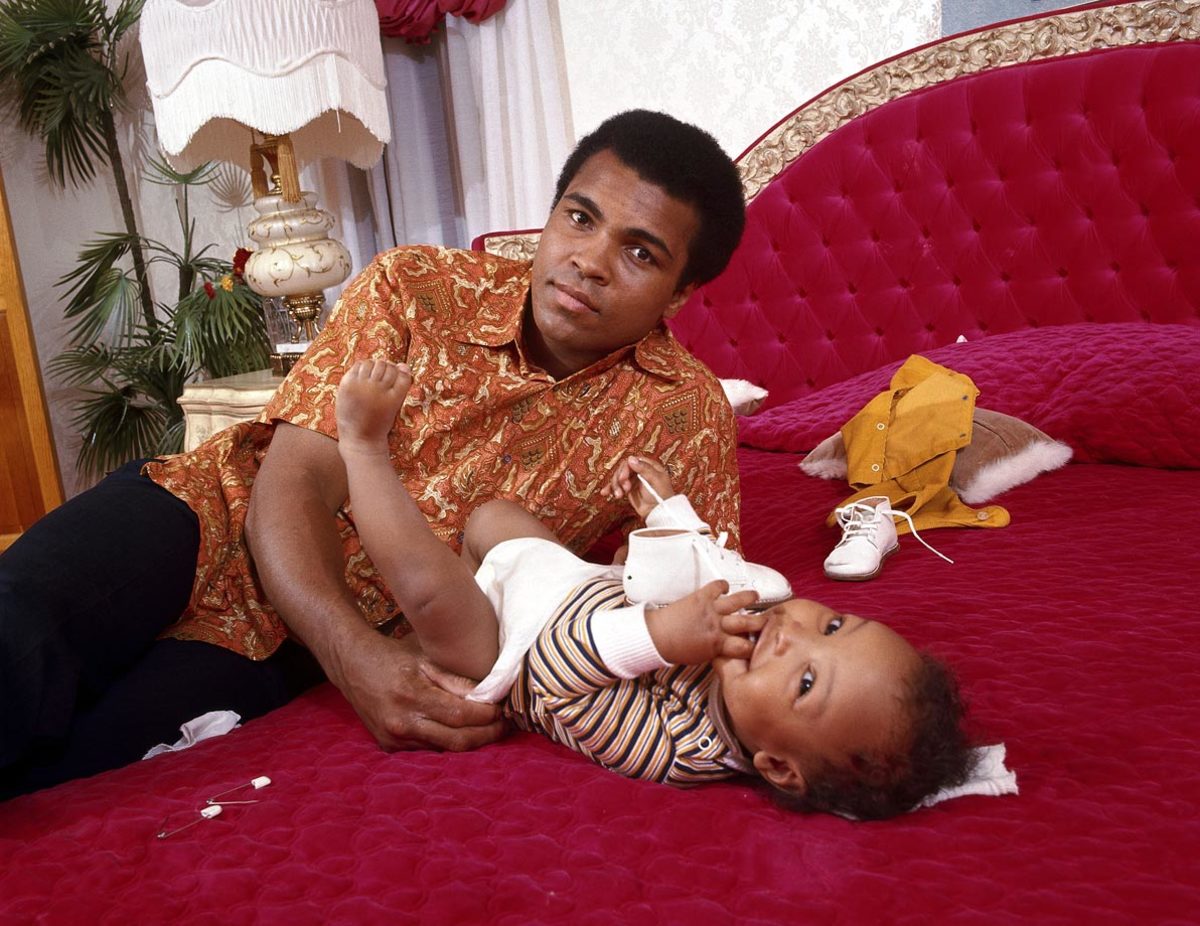

Ali changes the diaper of his son in his bedroom during a photo shoot at the family's home in April 1973. Ali had suffered a broken jaw less than a month earlier in his fight against Ken Norton.

In the wake of his split decision loss to Norton, Ali plays with his son in his bedroom at home in Cherry Hill, N.J.

Ali kisses his daughter Jamillah outside of their home following the loss to Norton, just the second defeat of his career.

The Ali family standing outside their New Jersey home. To the right of Muhammad Ali are his twin daughters, Jamilllah and Rasheda, daughter Maryum and his wife, Khalilah, holding their son Ibn Muhammad Ali Jr.

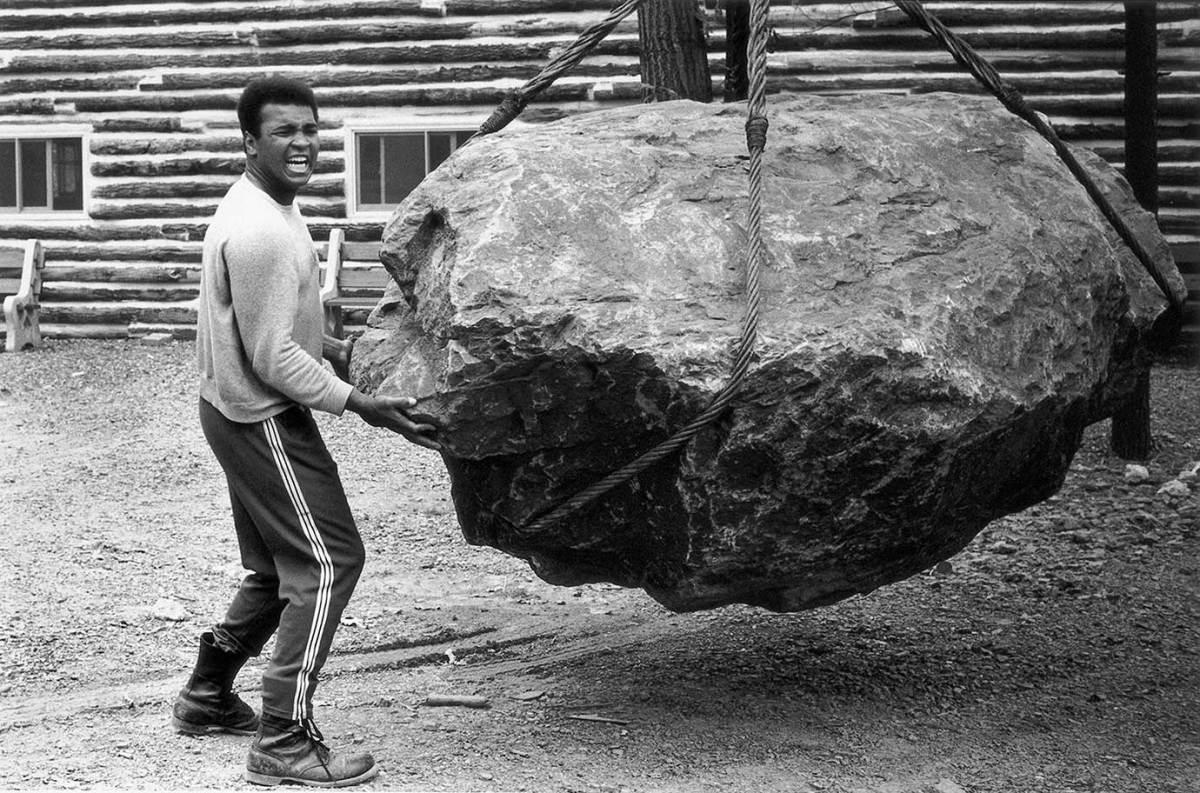

At his training camp cabin, Ali pushes a boulder during a photo shoot in Deer Lake, Penn., in August 1973. Ali was training for his rematch against Ken Norton, who broke his jaw five months earlier.

Ali chops wood at his cabin in Deer Lake. He referred to the training camp as "fighter's heaven" and used it to prepare for fights away from the spotlight.

The fighters weigh in on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson ahead of Ali and Ken Norton's September 1973 fight.

Johnny Carson listens to Ali on the Tonight Show three days before his rematch with Norton. Ali would avenge his earlier loss to Norton, winning a narrow split decision.

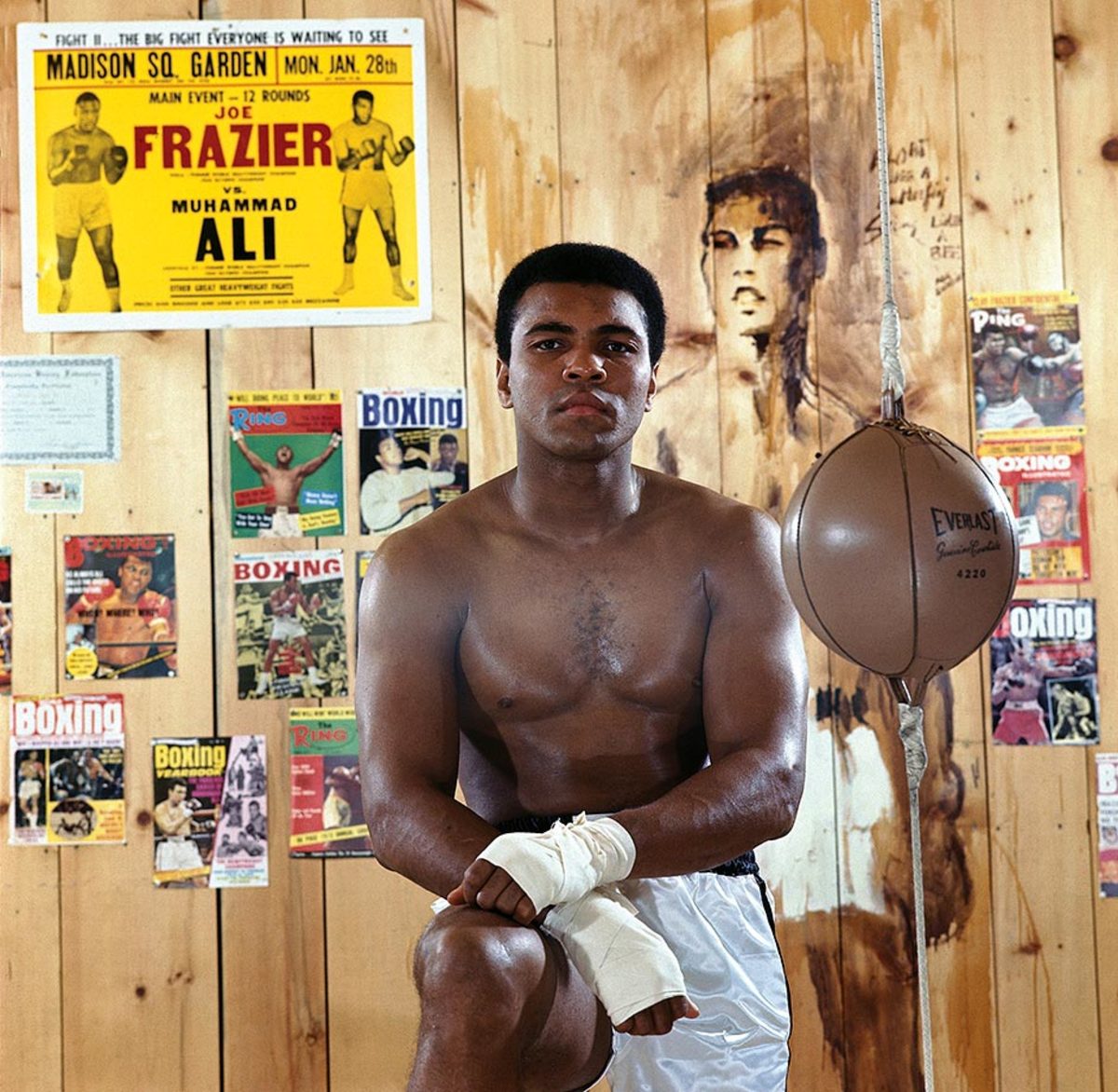

Ali poses in front of posters and magazine covers from throughout his career at his training camp cabin in Deer Lake in 1974.

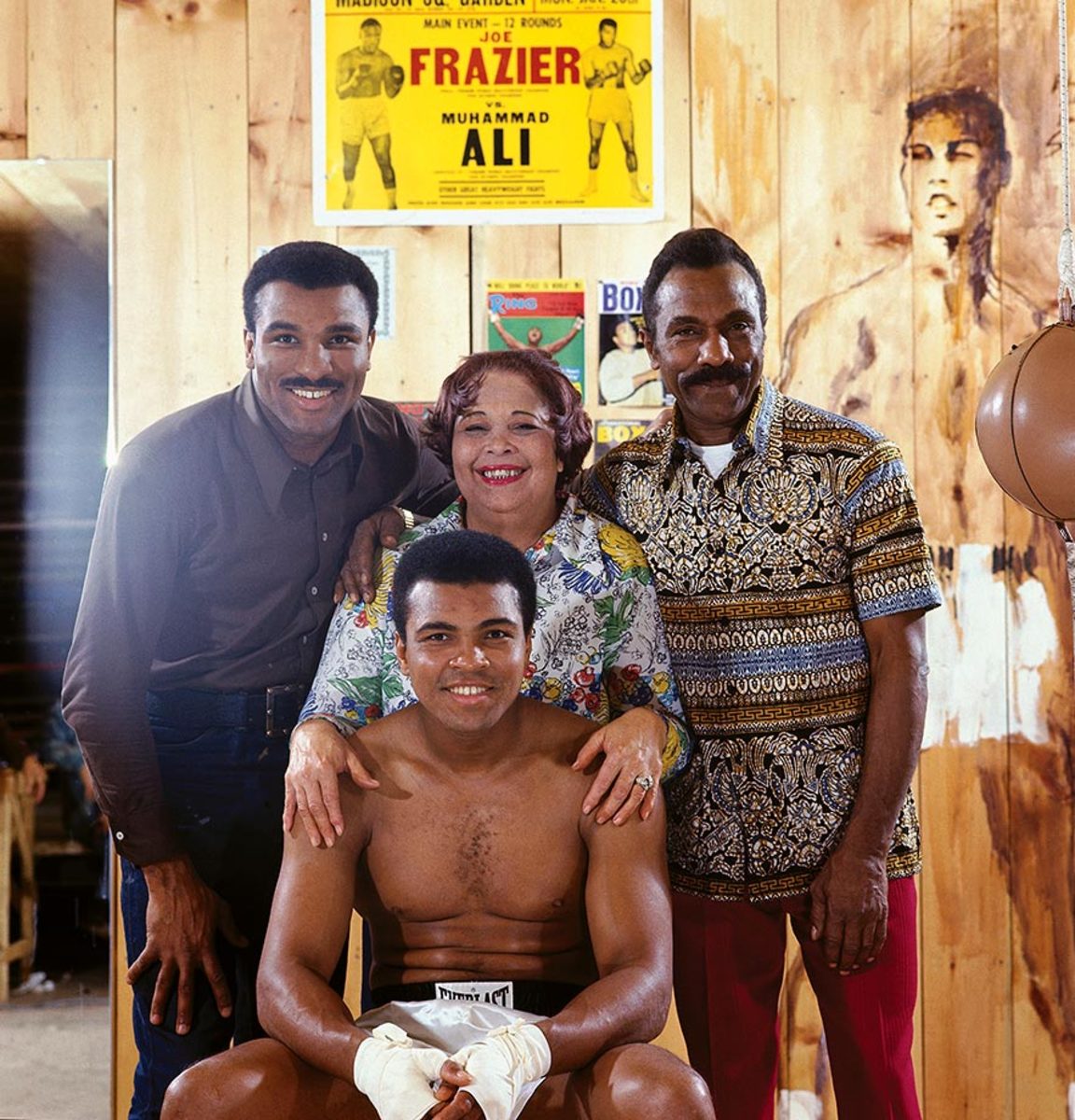

Ali poses with members of his family in front of a poster from his first fight with Joe Frazier. Ali's brother, Rahman Ali; mother, Odessa Clay; and father, Cassius Clay Sr. stand behind the boxer.

Less than three weeks before his rematch with Joe Frazier on Jan. 28, 1974, Ali wraps his hands while wearing a sauna suit at his training camp cabin.

Ali holds a newspaper at his cabin in January 1974. He is pointing to a headline that reads, "Frazier On Ali, I Think He's Crazy." Ali and Frazier fought for the second time later that month with Ali winning by a unanimous decision.

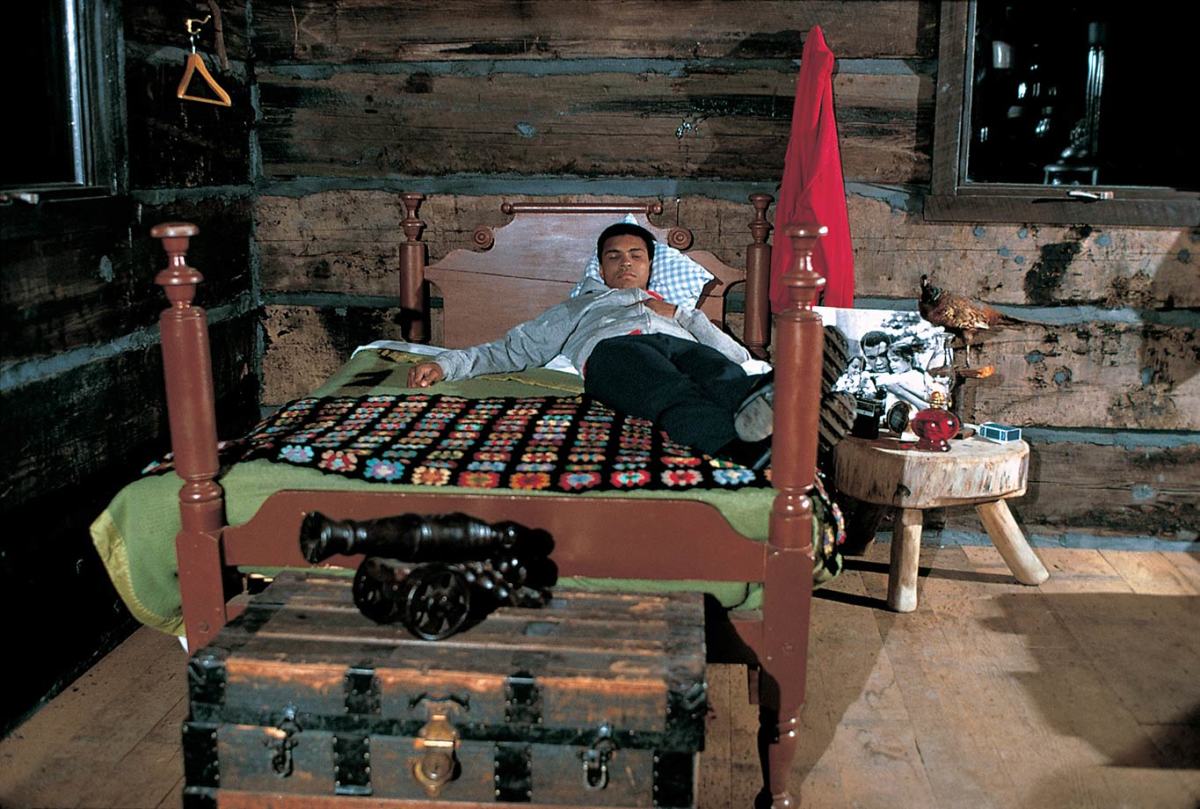

Ali lies on his bed at his cabin during the January 1974 photo shoot.

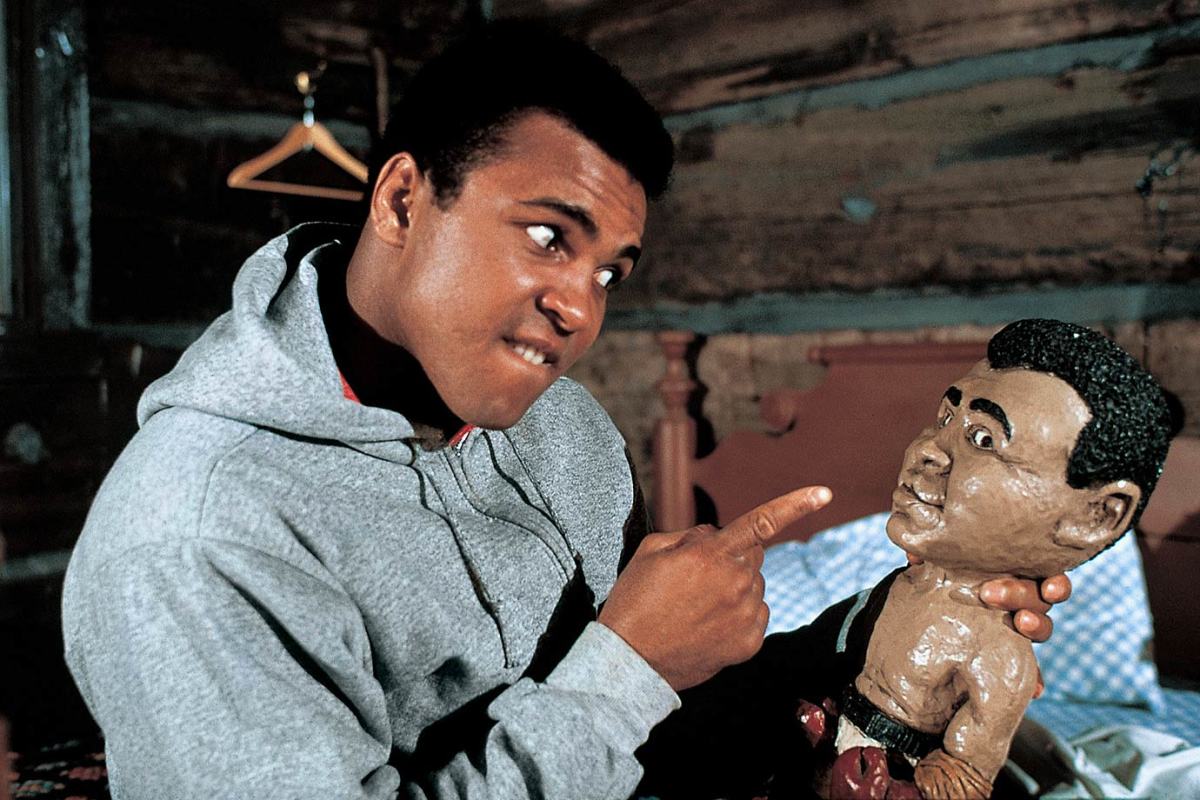

His smaller incarnation stares straight back as Ali plays with a doll of himself during the same 1974 shoot at his training camp cabin.

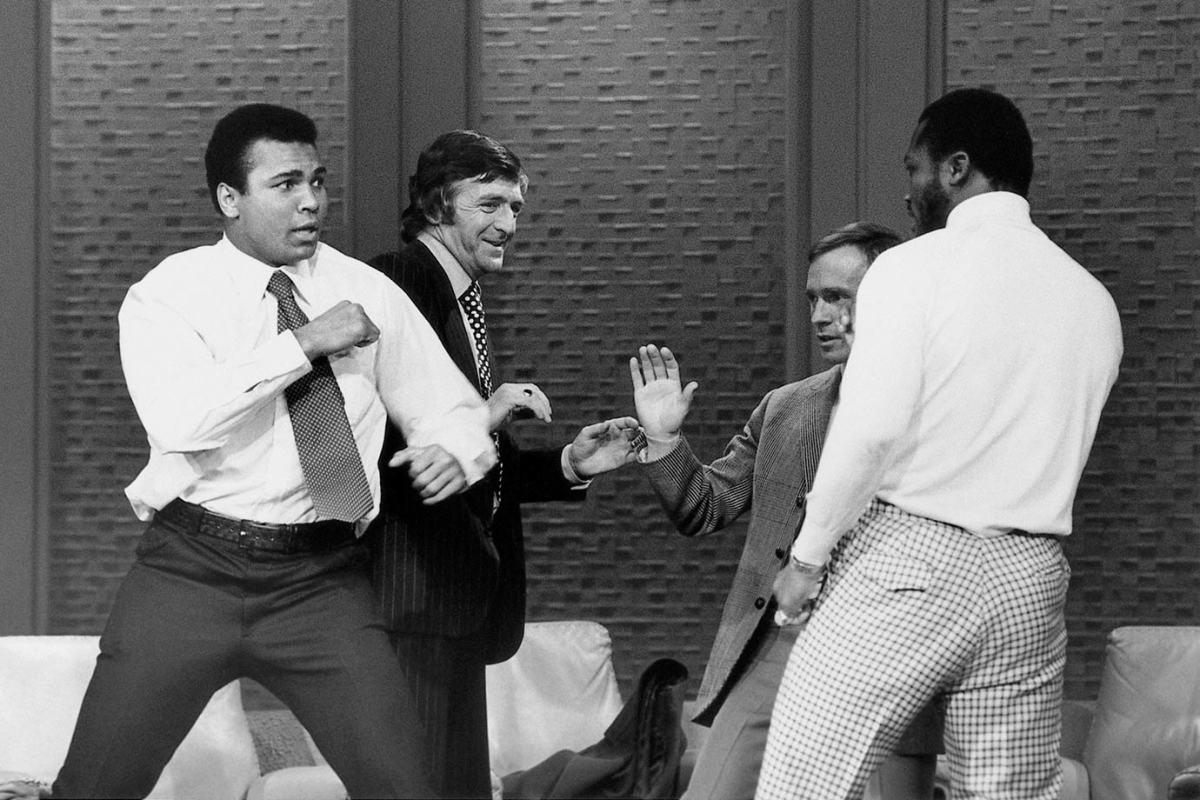

Ali and Joe Frazier fight on the set of The Dick Cavett Show while reviewing their 1971 bout in advance of their 1974 rematch. Ali called Frazier ignorant, to which Frazier took exception. As the studio crew tried to calm Frazier down, Ali held Frazier by the neck, forcing him to sit down and sparking a fight. The television set fight amped up anticipation of their January 1974 bout.

Exploring a different side of the sport, Ali broadcasts the fight between George Foreman and Ken Norton in March 1974. Foreman won the fight by technical knockout in the second round, setting up the showdown with Ali in Zaire.

Ali jumps rope at the Salle de Congres in Kinshasa, Zaire, while training for his heavyweight title fight against George Foreman. Both Ali and Foreman spent most of the summer of 1974 training in Zaire to adjust to the climate.

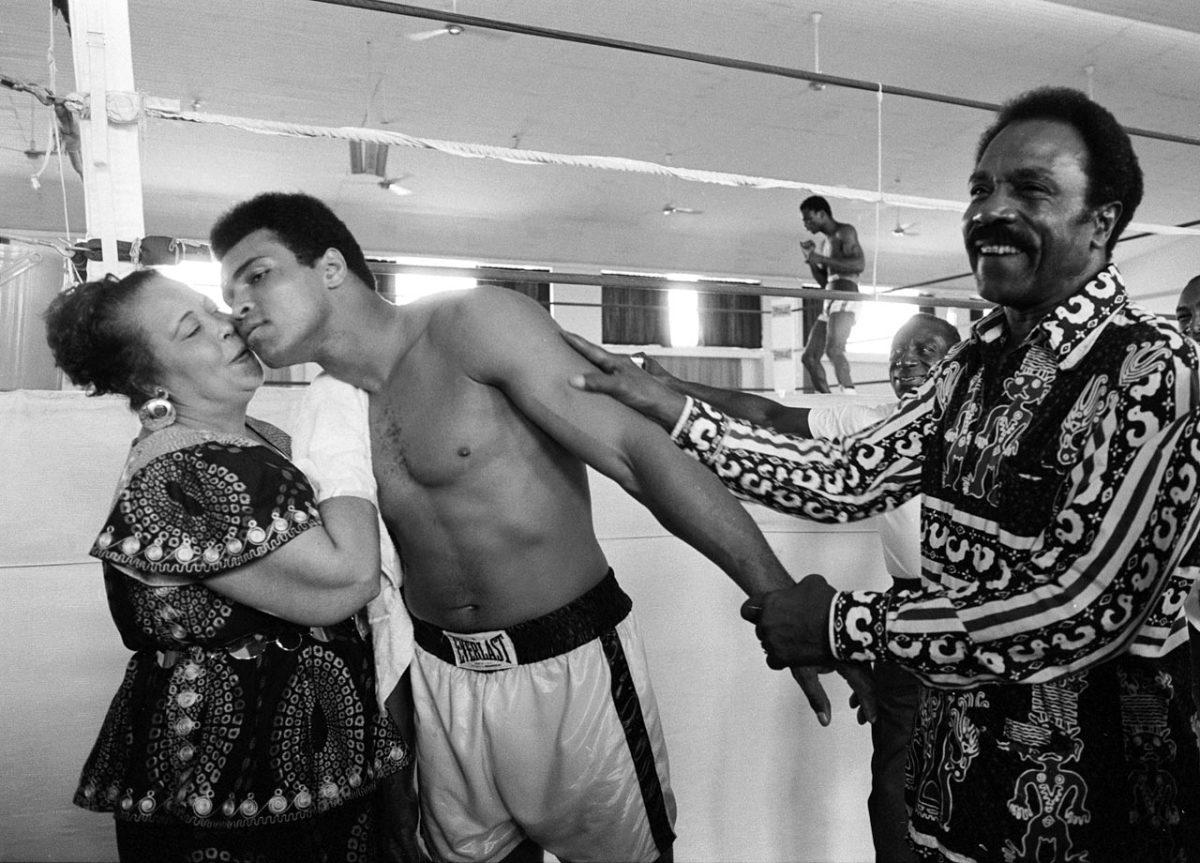

While training before his fight with George Foreman, Ali kisses his mother, Odessa Clay, while his father, Cassius Clay Sr., looks on. Ali's superior strategy and ability to take a punch led him to his upset victory as he absorbed body blows from Foreman before he responded with powerful combinations to Foreman's head.

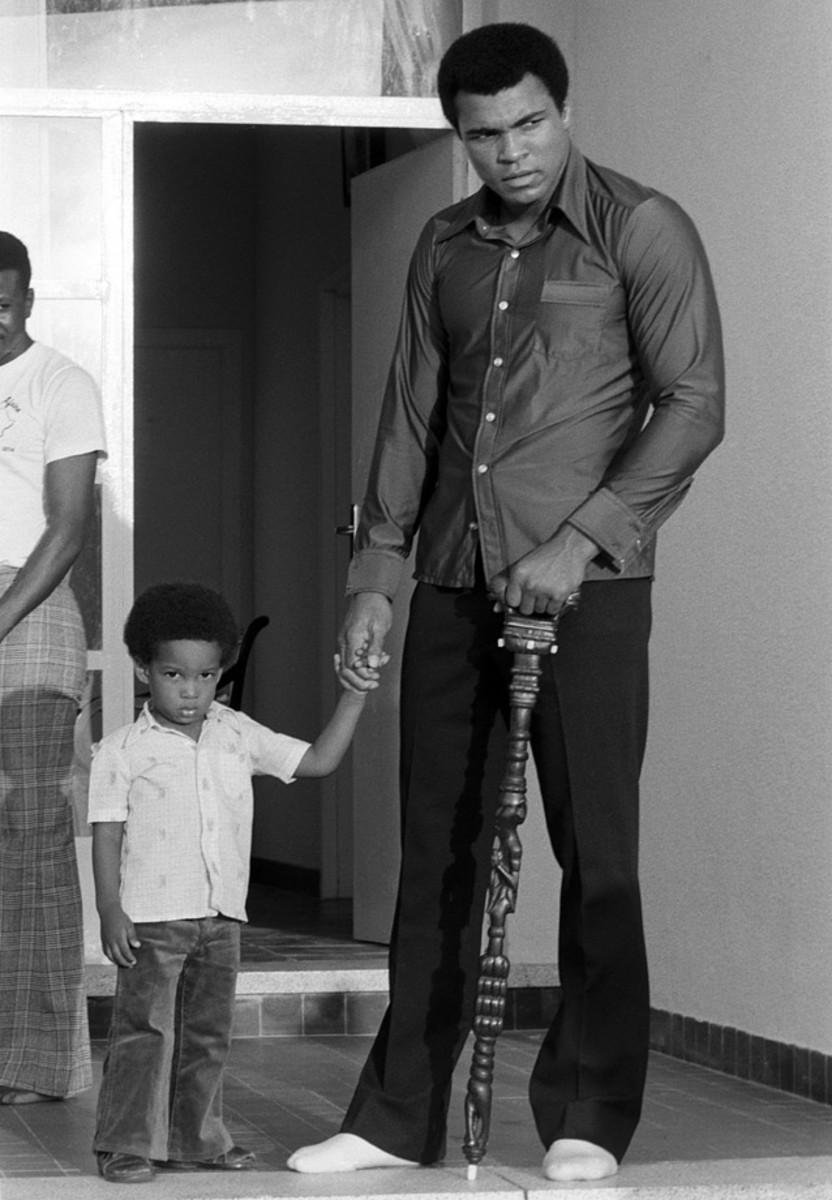

Four days before the fight, Ali holds the hand of his son Ibn in Zaire. Ali successfully courted the favor of the Zaire crowd, prompting chants of "Ali bomaye!" — translated as "Ali, kill him!"

Ali poses in front of the Le Militant statue at the presidential complex that was the site of Ali's January heavyweight title bout with Foreman. The fight was originally set for a month earlier, but Foreman suffered a cut near his eye during training, forcing a delay.

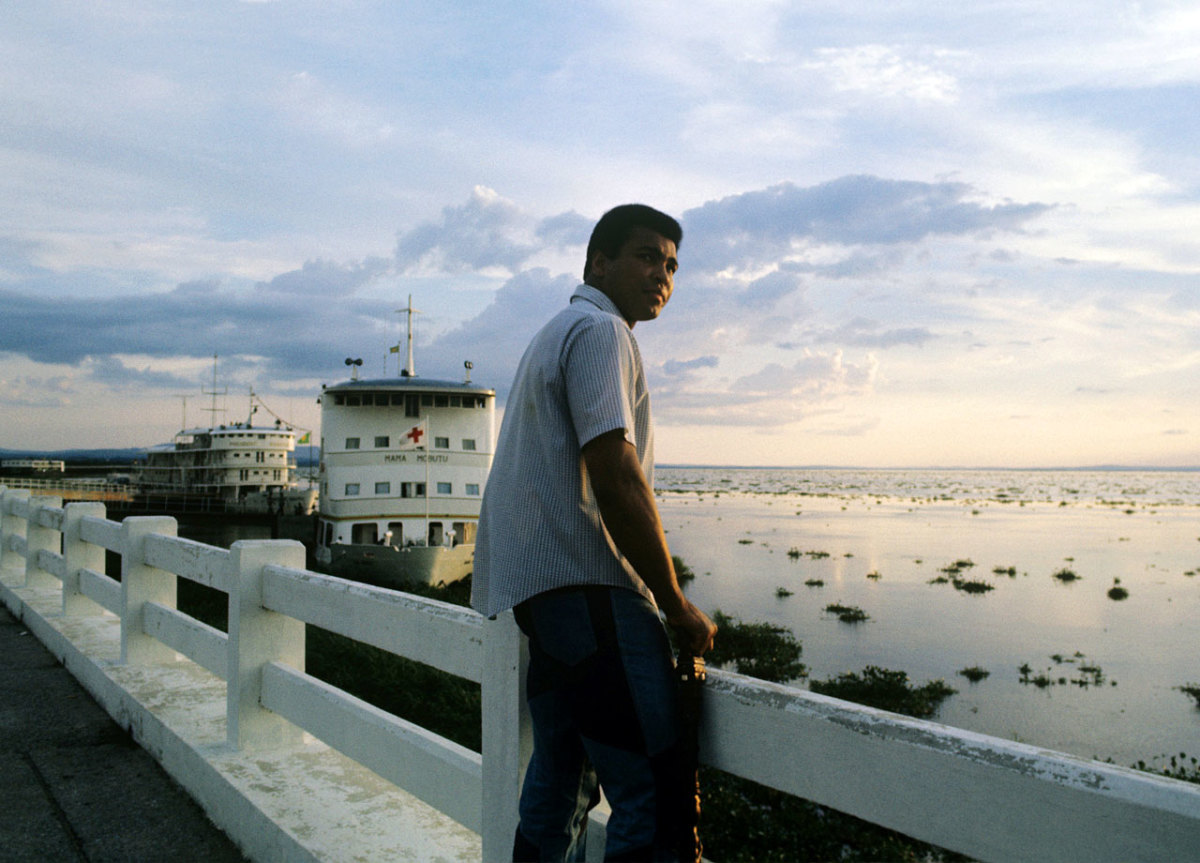

Ali stands against the railing on the River Zaire watching the sunset four days before the Rumble in the Jungle. The fight was sponsored by Zaire to achieve the $5 million purse promoter Don King had promised both Ali and Foreman.

Before employing his famous rope-a-dope strategy against Foreman, Ali makes a face at the camera. Ali allowed Foreman to throw many punches but only into his arms and body, and when Foreman tired himself out from the mostly ineffective punches, Ali took control of the fight.

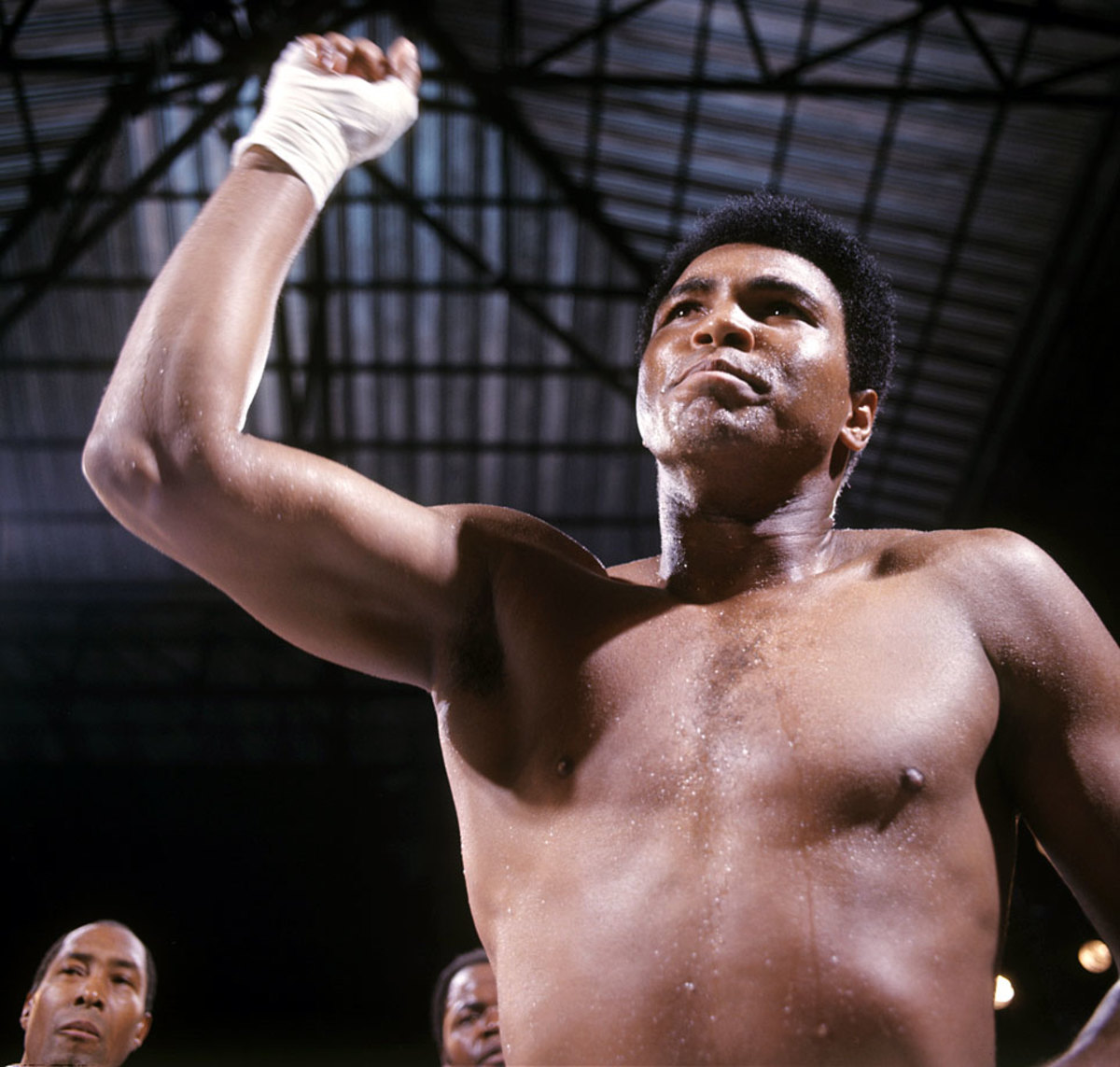

Ali points before his bout with Foreman. The victory over his favored opponent made him the heavyweight champion of the world for the first time since he was stripped of his titles in 1967.

Ali stares at George Foreman during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali earned his shot at the heavyweight title by defeating Joe Frazier in January 1974, avenging a loss three years earlier.

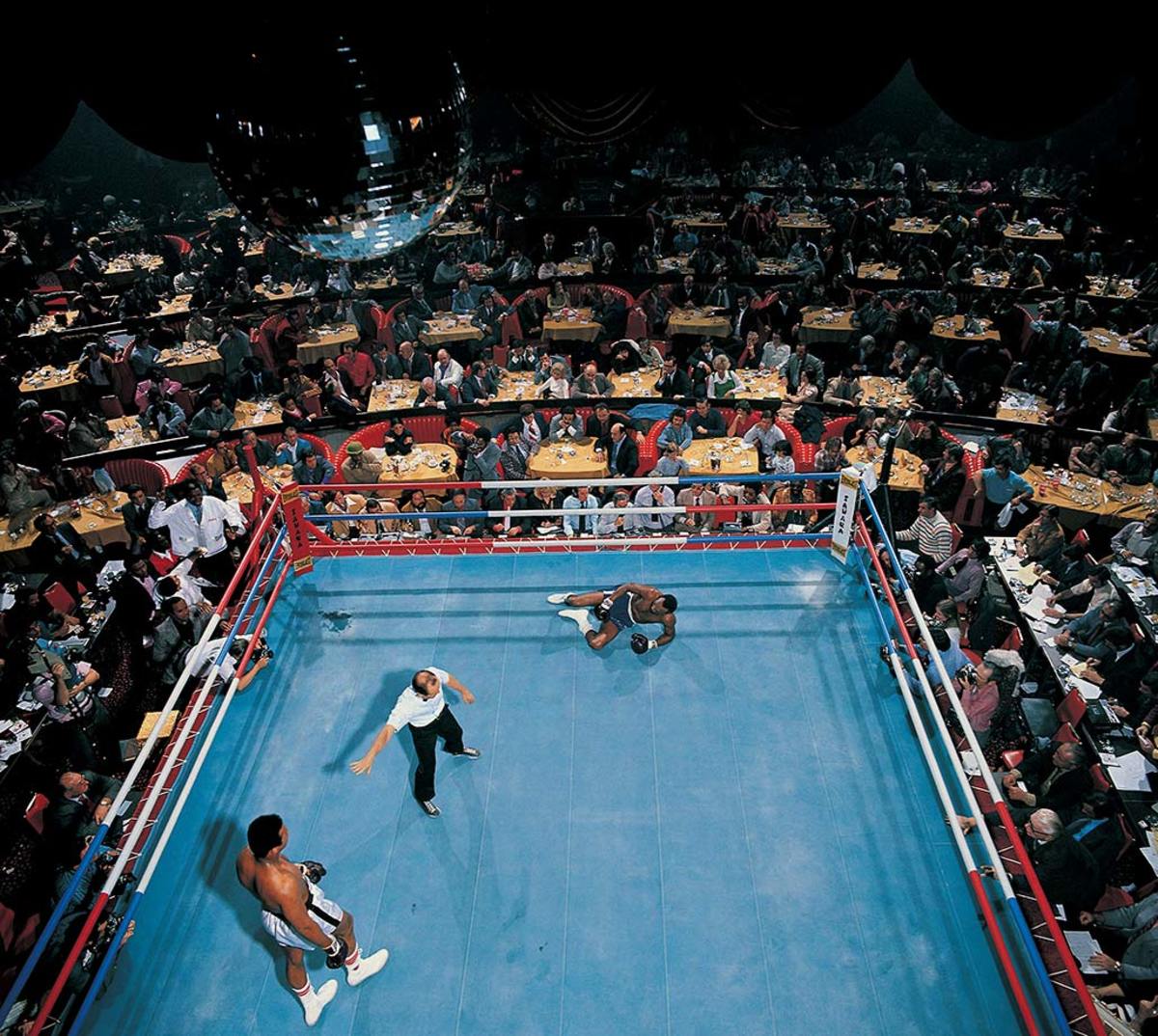

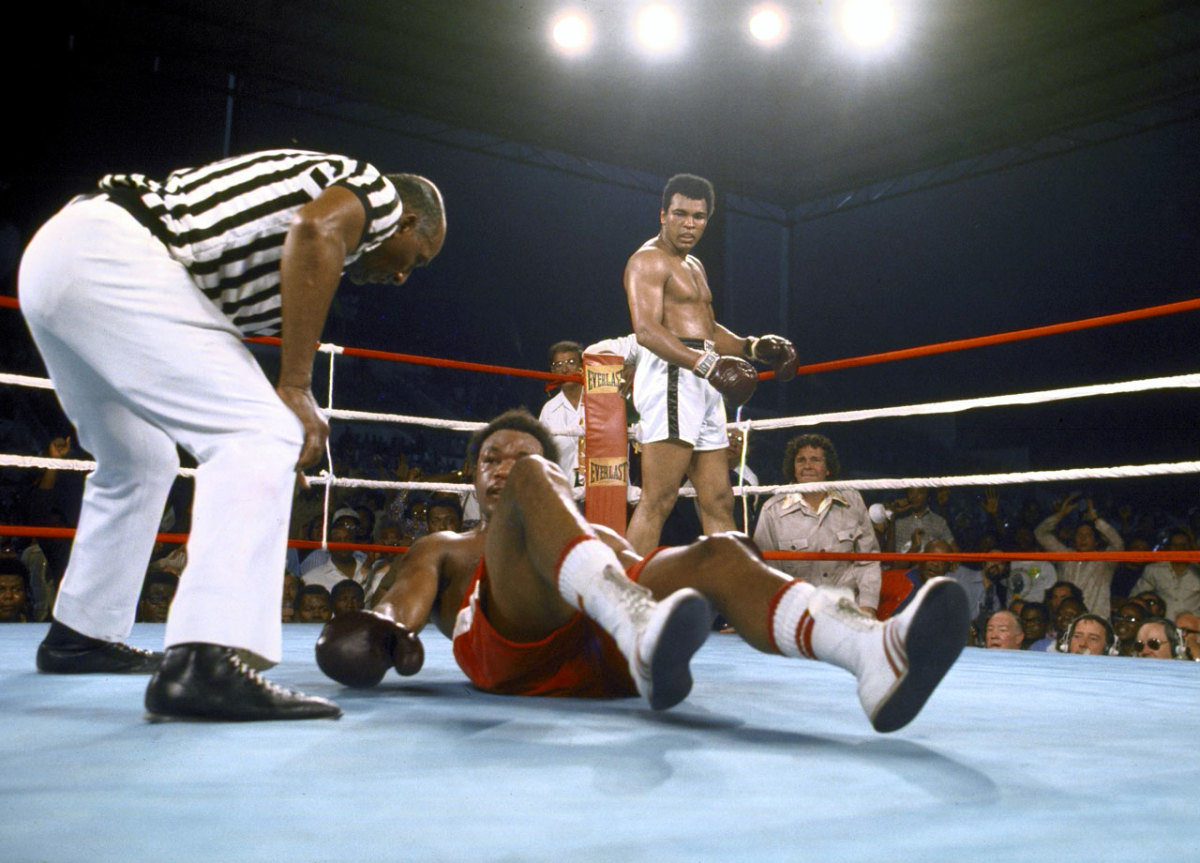

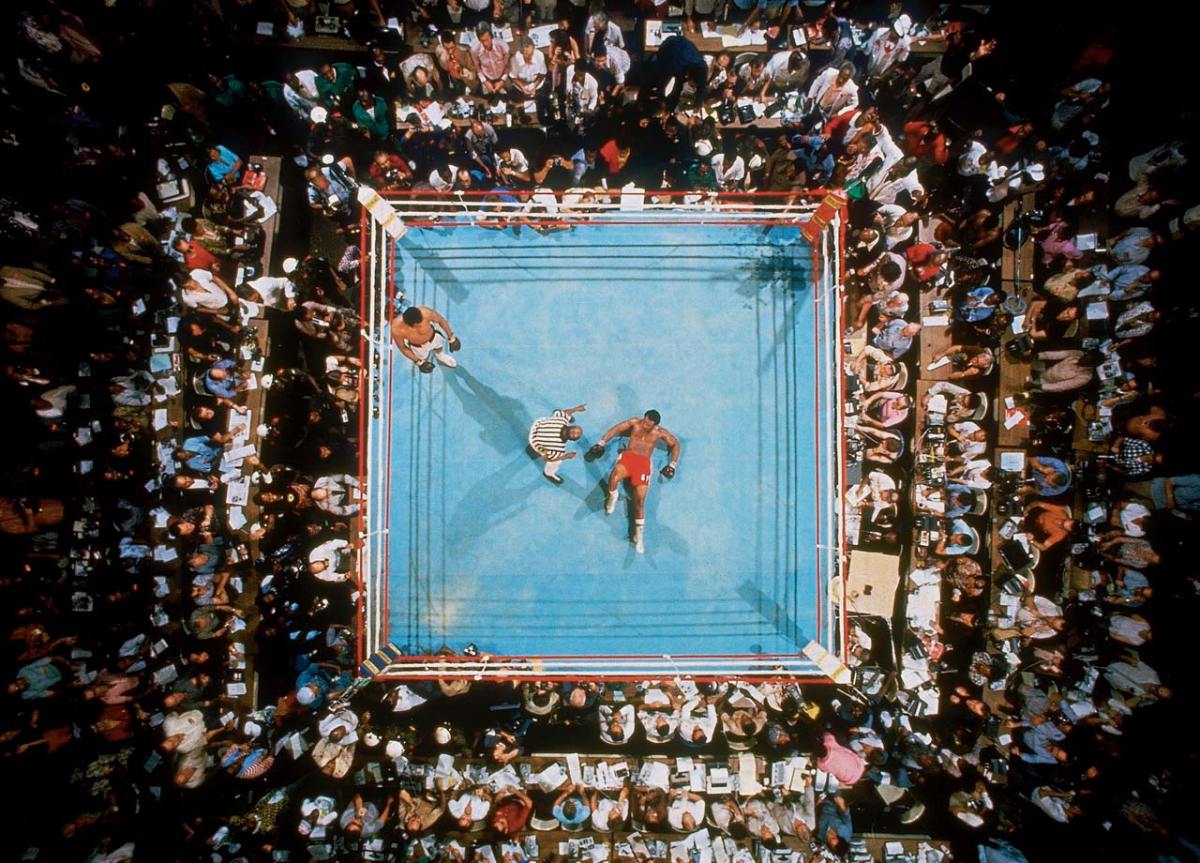

Foreman lies down on the canvas as Ali stands in the background during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali knocked Foreman down with a five-punch combination in the eighth round, and referee Zack Clayton counted him out.

Big George stares at the ceiling as referee Zack Clayton counts him out in the eighth round. The victory made Ali, once again, the heavyweight champion of the world.

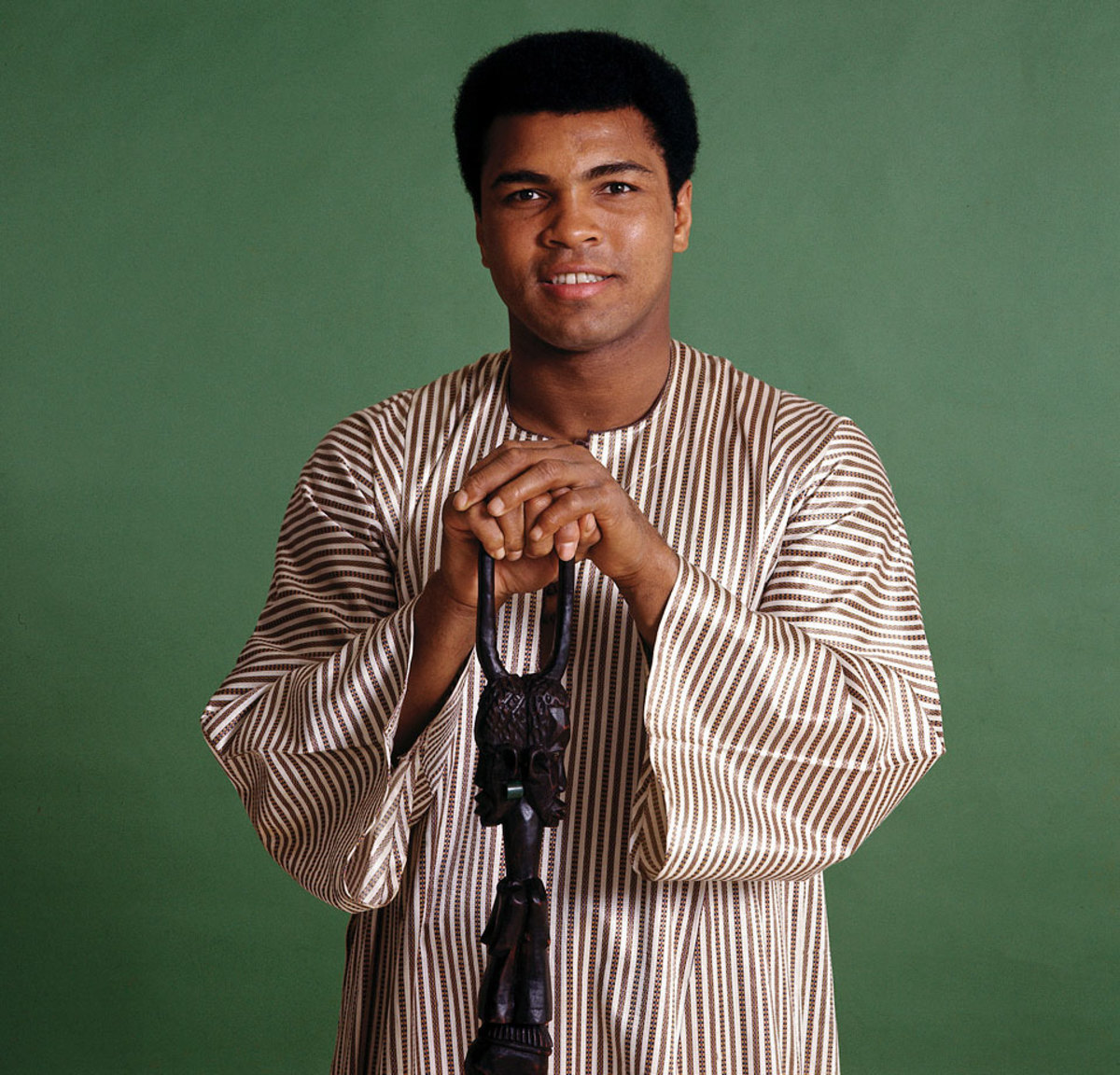

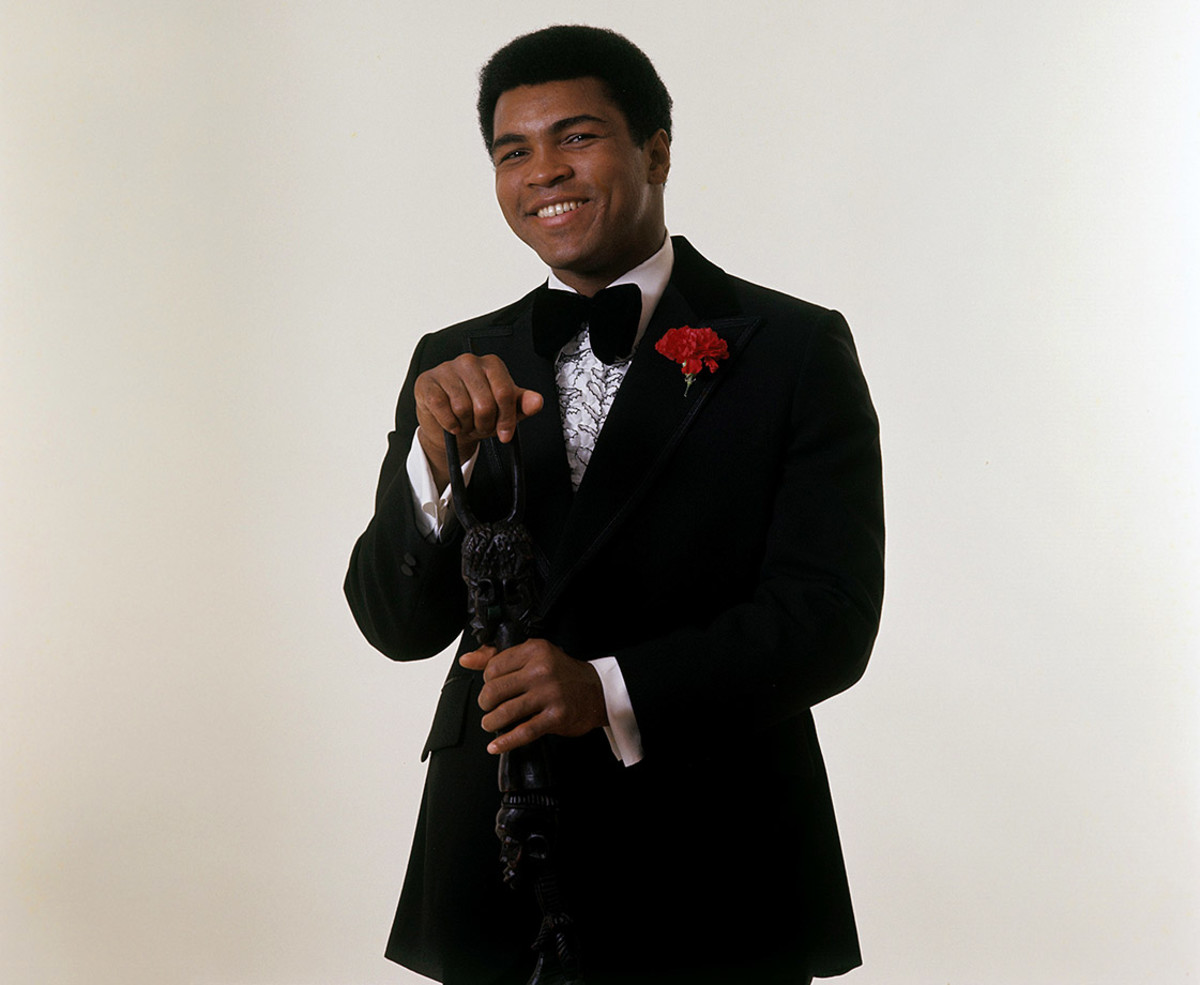

Ali poses for a portrait after being selected as the Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year in 1974. Ali wore a dashiki, a men's garment widely worn in West Africa. He also brought the walking stick given to him by Zaire's president.

This time Ali wears a tuxedo, but keeps the walking stick, during the November photo shoot for Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year.

Ali talks with Howard Cosell outside of the United Nations Headquarters for a segment on the Wide World of Sports. Later that day, Ali held a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

Ali talks with Reverend Jesse Jackson outside of the United Nations Headquarters before a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

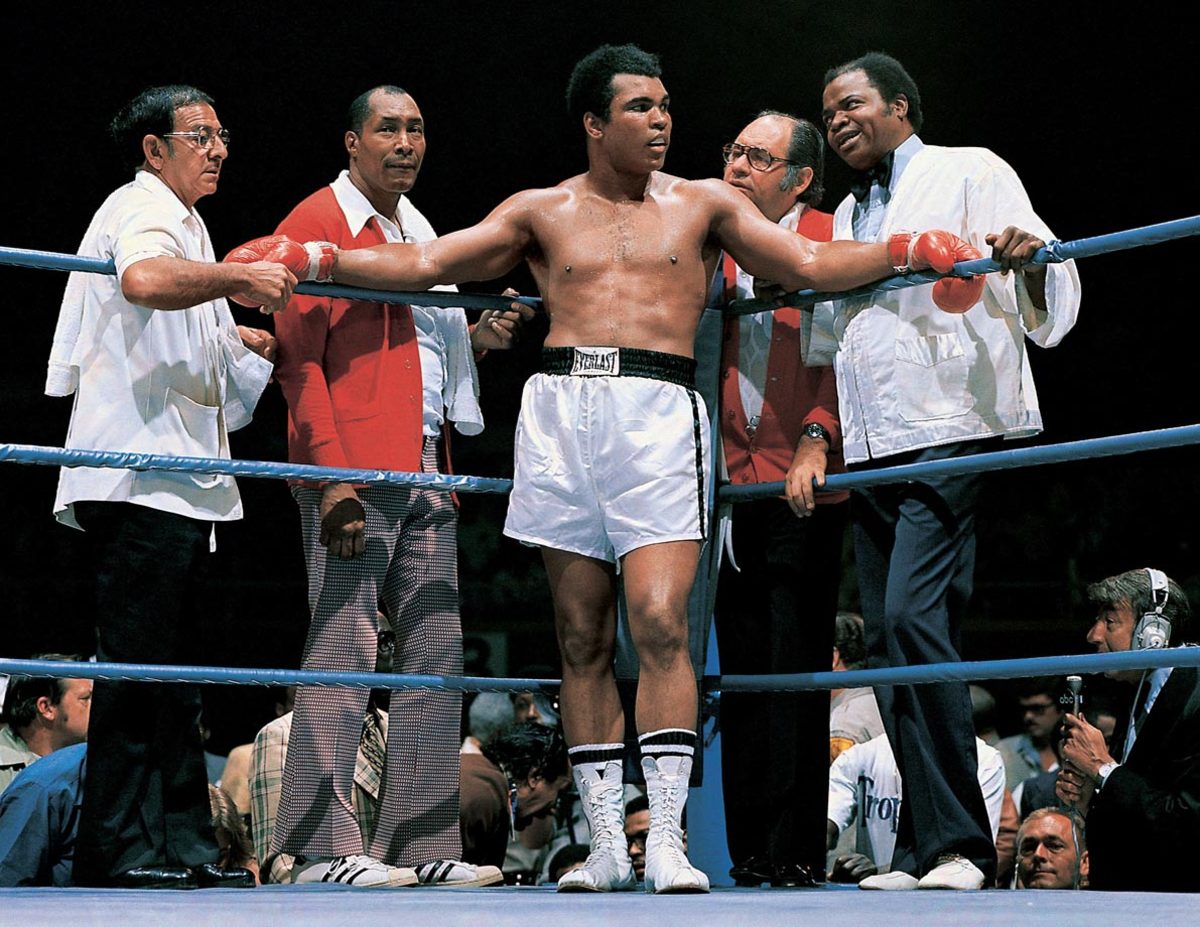

Ali stands with trainer Angelo Dundee, assistant trainer Wali Muhammad, physician Dr. Ferdie Pacheco and assistant trainer Drew Bundini Brown before his bout with Ron Lyle in May 1975. Ali won the fight by technical knockout in the 11th round.

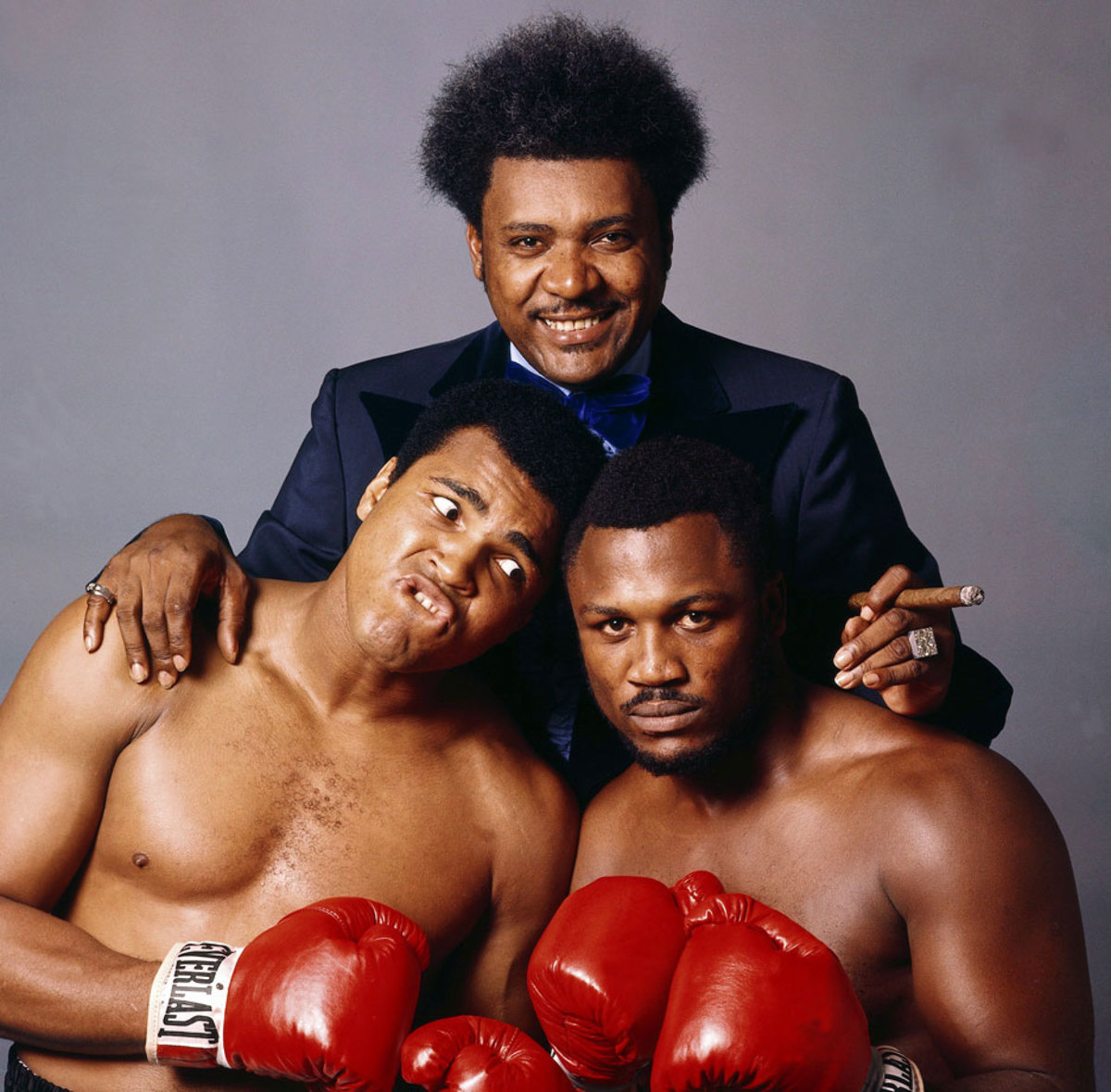

Along with Don King and Joe Frazier, Ali sat for a portrait leading up to the Thrilla in Manila. Ali verbally abused Frazier during the buildup to the fight, telling the media that "it will be a killa and a thrilla and a chilla when I get the gorilla in Manila."

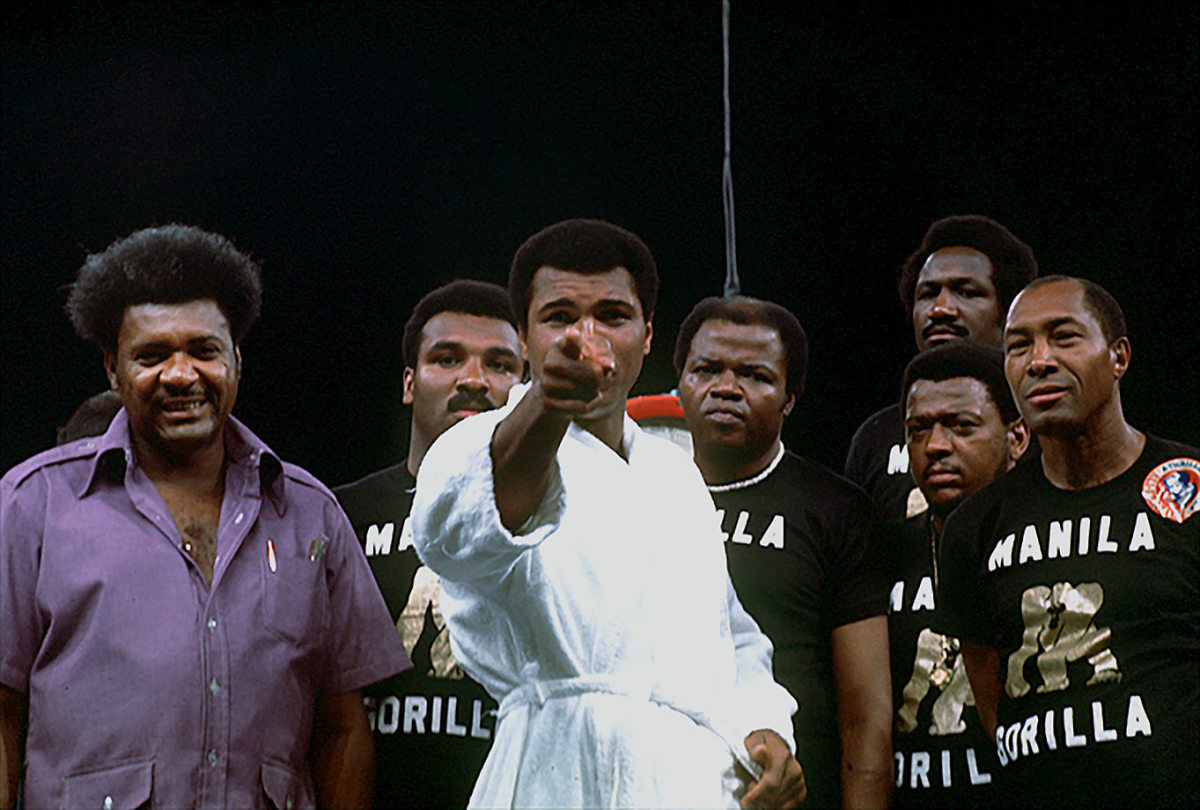

Ali points at the camera with Don King and his training staff behind him before the weigh-in for the Thrilla in Manila in October 1975. Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos offered to sponsor the bout and hold it in Metro Manila to divert attention from the turmoil in the country that had forced the imposition of martial law in 1972.

Wrapping up Joe Frazier proved more difficult than Ali expected, having thought Frazier would represent an easy payday and be unable to live up to his billing. The fight turned out to be a brutal affair.

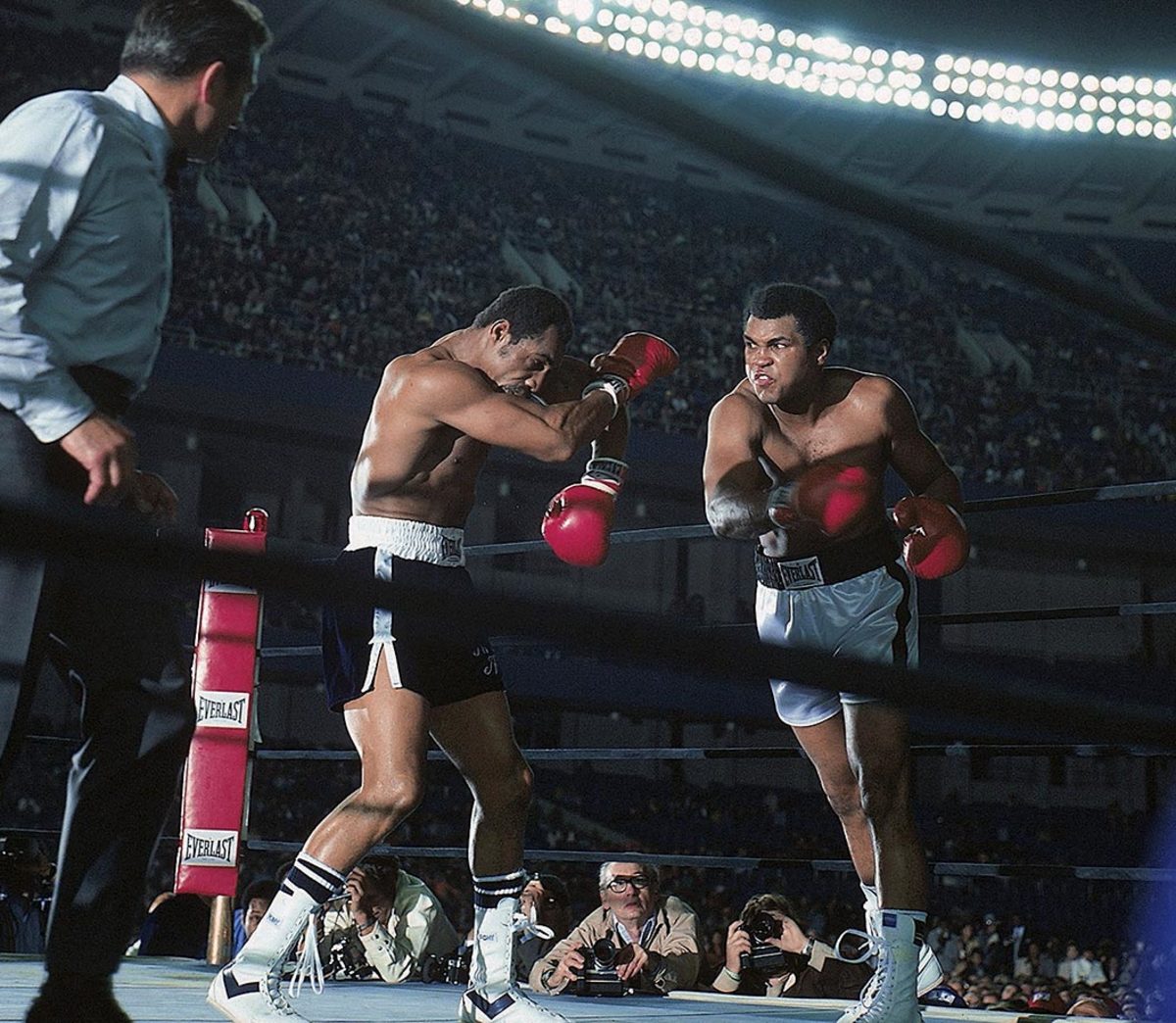

Frazier faces an Ali right hook in their fight in Quezon City, Philippines. The two fighters traded vicious blows during their 14 rounds. "Man, I hit him with punches that'd bring down the walls of a city," Frazier said. Ali withstood the blows to win by TKO in the 15th round.

The third fight between Ali and Frazier, Ali won the bruising battle between the two powerful punching heavyweights when Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, stopped the fight before the 15th round.

A back and forth exchange, Ali controlled the early rounds of the Thrilla in Manila before Frazier fought back with powerful hooks. Ali finished strong, regaining momentum in the later rounds.

Ali speaks to the press after winning the Thrilla in Manila bout with Frazier.

Ali holds a drinking concoction given to him by Dick Gregory, an advocate of a raw fruit and vegetable diet, in 1976.

Before his 1976 fight against Ken Norton at Yankee Stadium, Ali watches a fight on television from his hotel room. A police strike at the time of the fight created a dangerous environment outside the stadium that all but eliminated walk-up sales.

Norton takes a right hook during the heavyweight title fight against Ali. The bout, which Ali won by a unanimous, but controversial, decision, was the last boxing match at Yankee Stadium until 2010.

Ali makes a face during his fight with Earnie Shavers in 1977 at Madison Square Garden. Hurt badly by Shavers in the second round, Ali rebounded and outboxed Shavers throughout to build a lead on points before Shavers came on again in the later rounds. Seemingly exhausted going into the 15th and final round, Ali remained victorious by producing a closing flurry that left Shavers wobbling at the bell and the Garden crowd once again in delirium over his Ali magic.

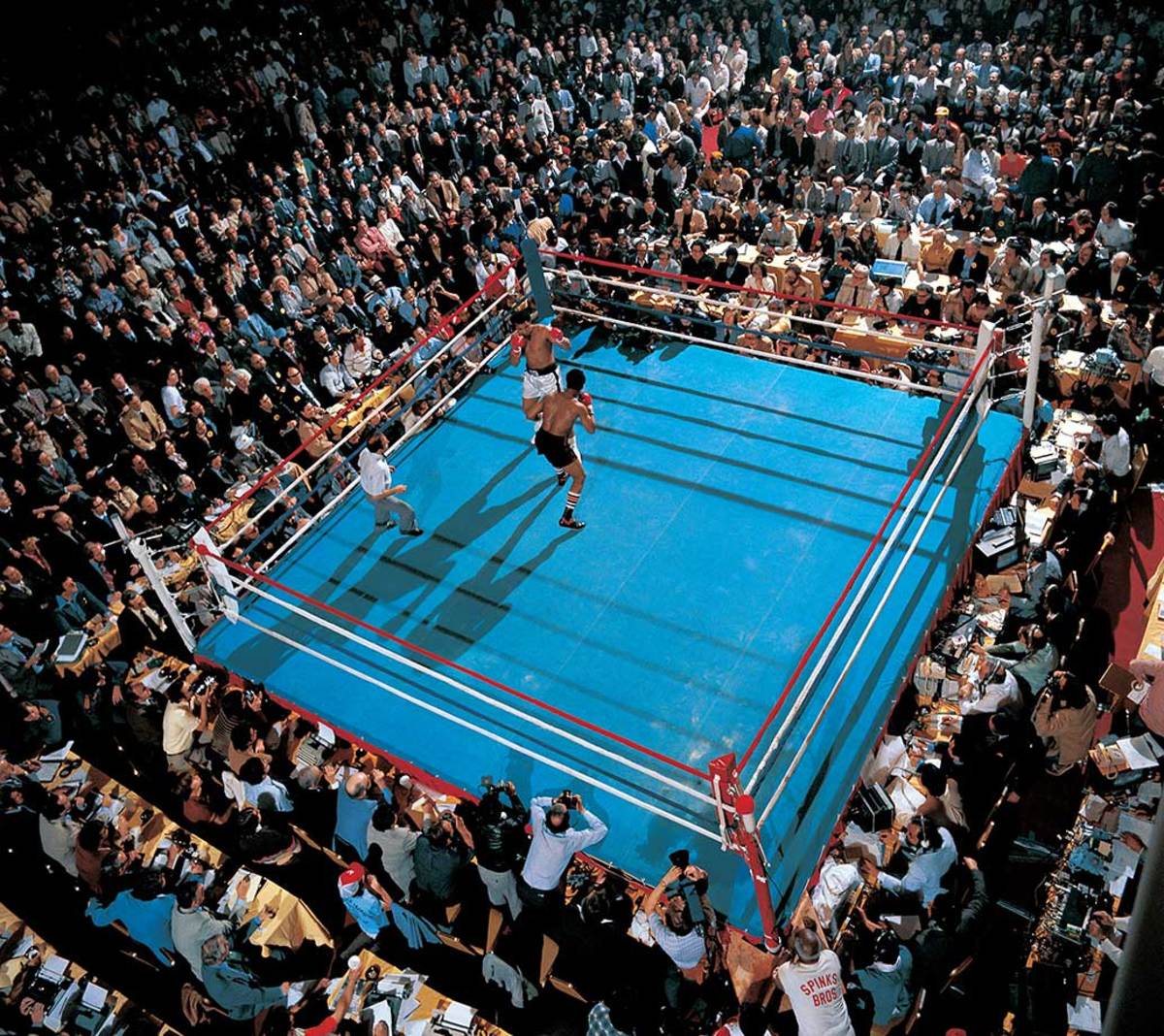

Ali squares off with Leon Spinks at the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel in February 1978. Spinks won the fight in a split decision, ending Ali's 3.5-year reign as the heavyweight champion. It was the only time in Ali's career that he lost his championship title in the ring.

Leon Spinks took center stage over Ali at the press conference after their fight. The victorious Spinks and his gap-toothed grin were featured on the Feb. 19, 1978 cover of Sports Illustrated.

Ali lands a straight right hand to the head of Spinks in the rematch of their title bout in 1978. Ali won on a 15 round decision.

Don King pulled the strings again when Ali faced Larry Holmes before their November 1980 fight. King became a key figure in Ali's career, promoting his biggest fights, the Thrilla in Manila and the Rumble in the Jungle.

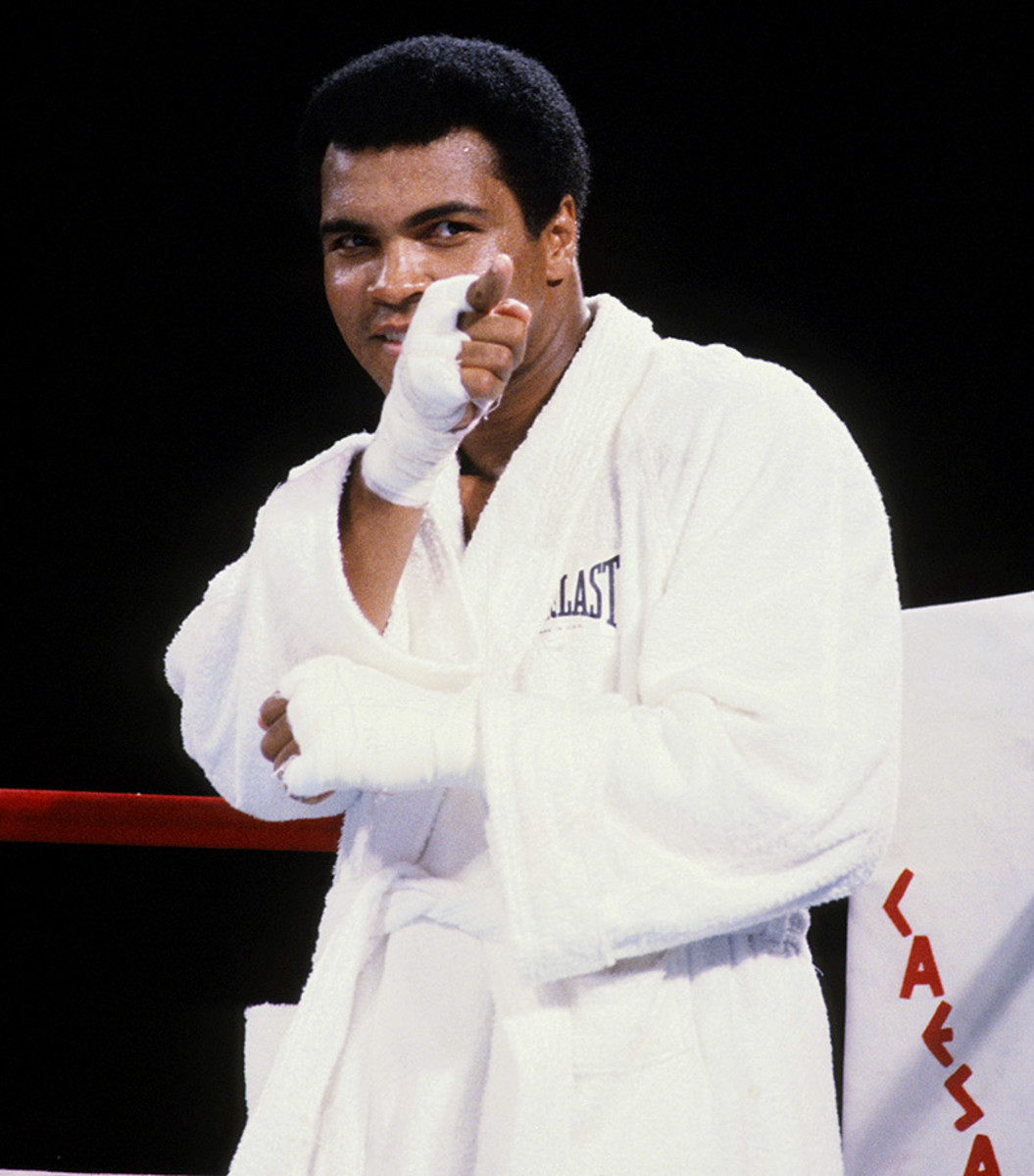

Ali points at Larry Holmes before their bout at Caesars Palace in 1980.

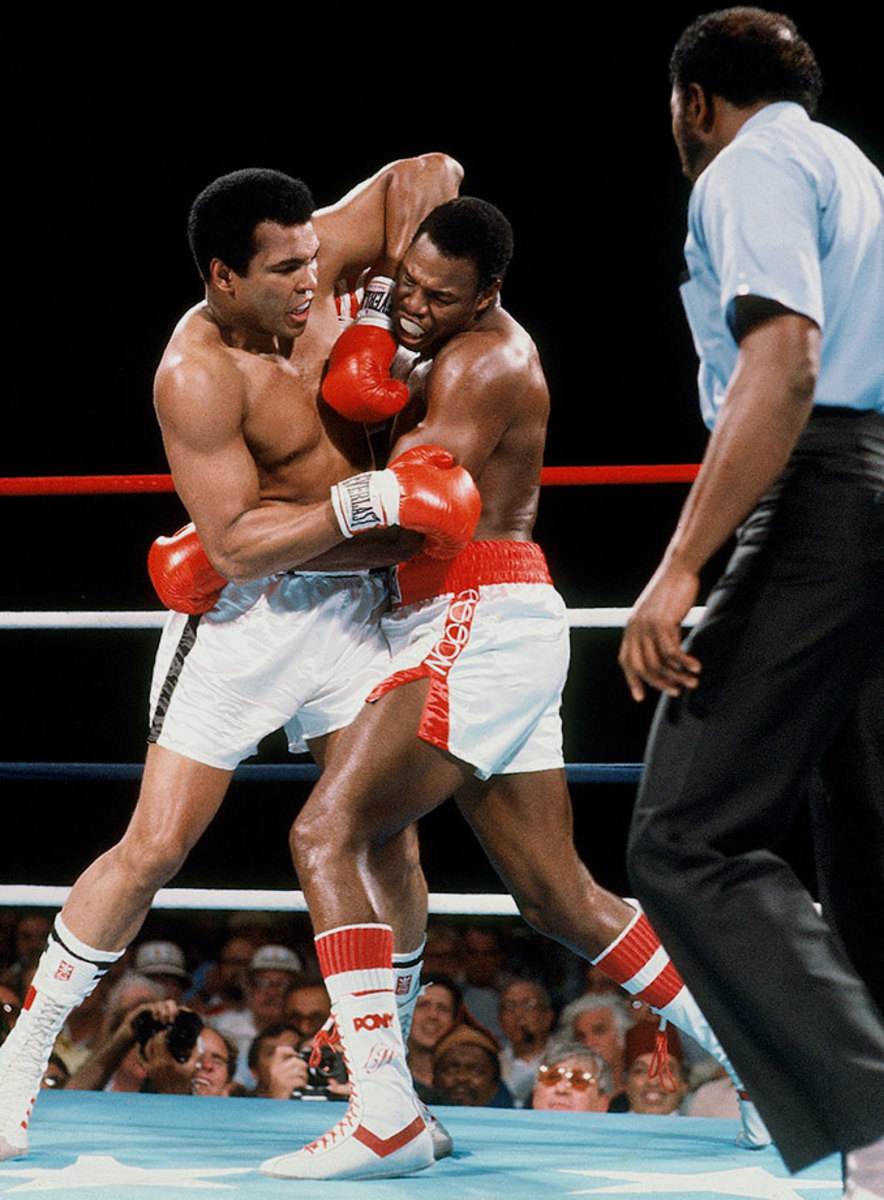

Ali grapples with Holmes during their bout in 1980. Trainer Angelo Dundee stopped the fight in the 11th round, marking the fight as Ali's only career loss by knockout.

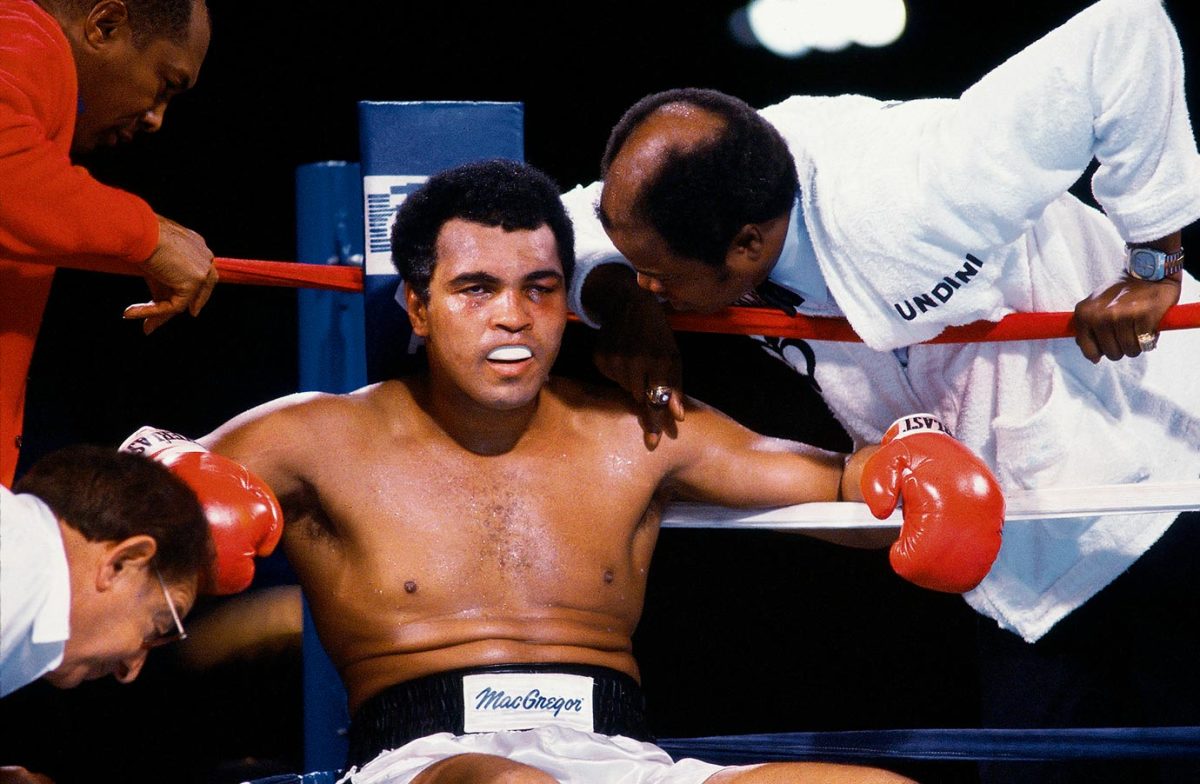

Drew Bundini Brown leans in to speak to Ali, who returned to fight Holmes after a brief retirement. By this time, Ali had already begun developing a vocal stutter and trembling hands and taken thyroid medication to lose weight that left him tired and short of breath.

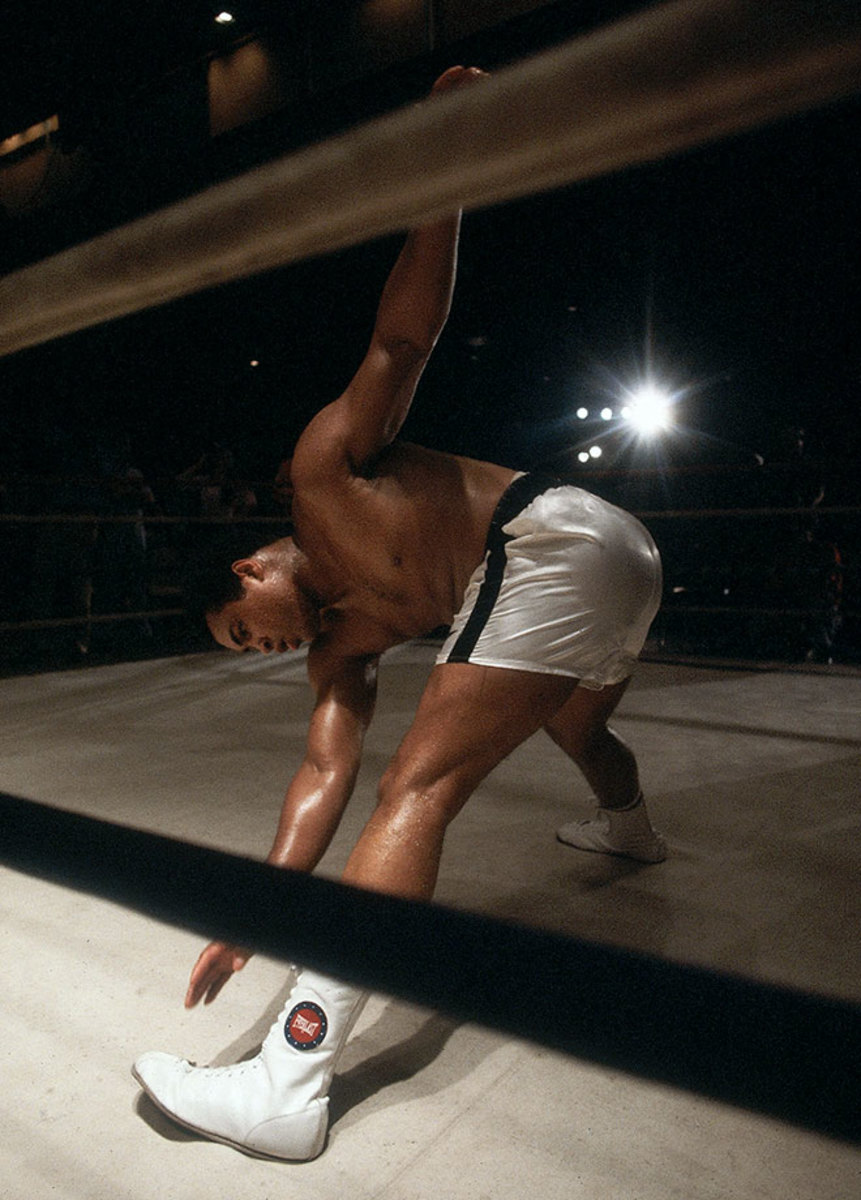

Ignoring pleas for his retirement, Ali stretches before a fight against Trevor Berbick in Nassau, Bahamas. Ali lost to Berbick in a unanimous decision and retired after the bout, the 61st of his career.

Ali pretends to spar with artist LeRoy Neiman at his home in Los Angeles. Neiman met Ali in 1962 and made many paintings and sketches from throughout Ali's life.

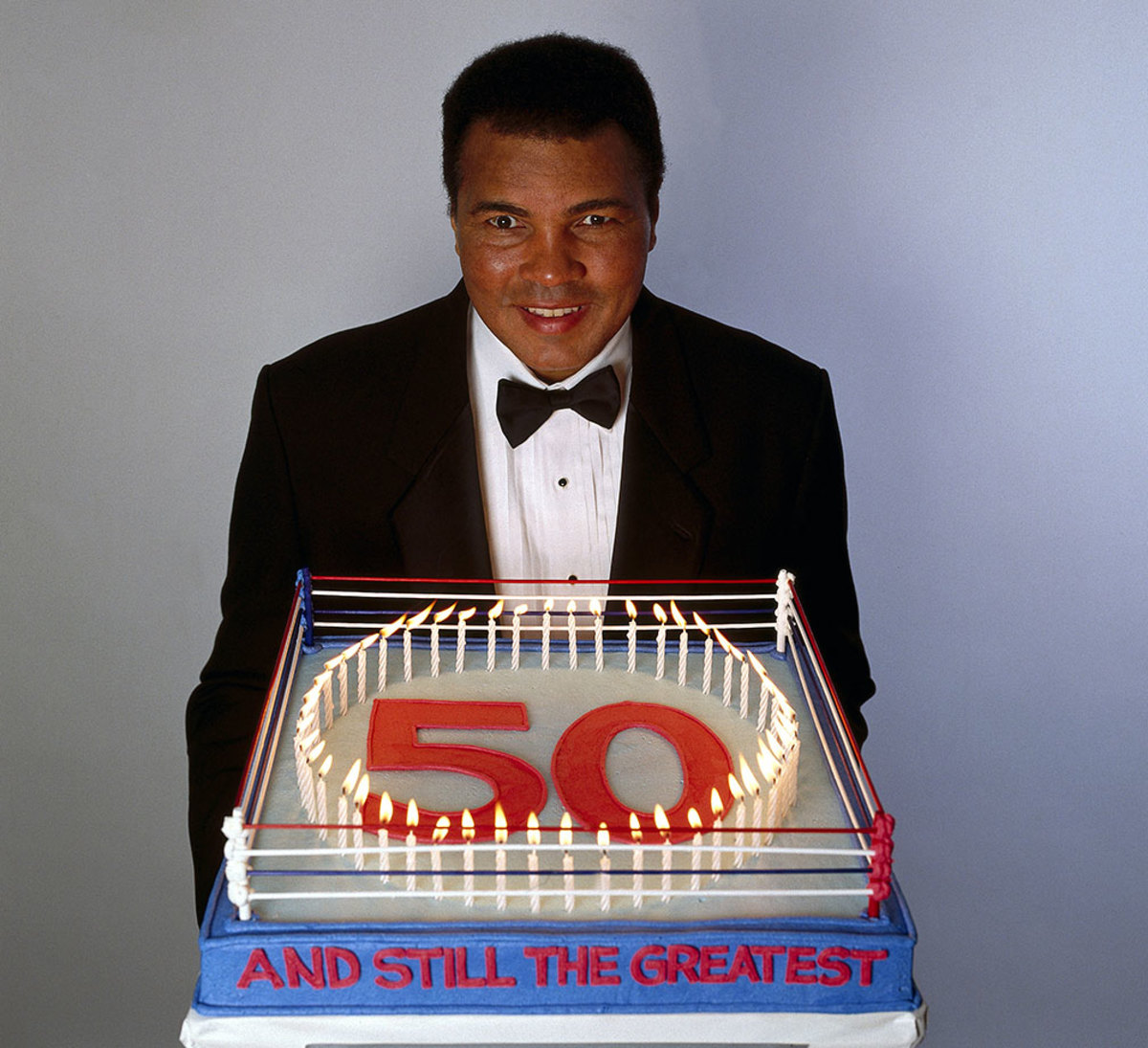

Cake in hand, Ali poses for a 50th birthday portrait in 1991. Although diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome seven years earlier, Ali was still active, traveling to Iraq during the Gulf War to meet with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages.

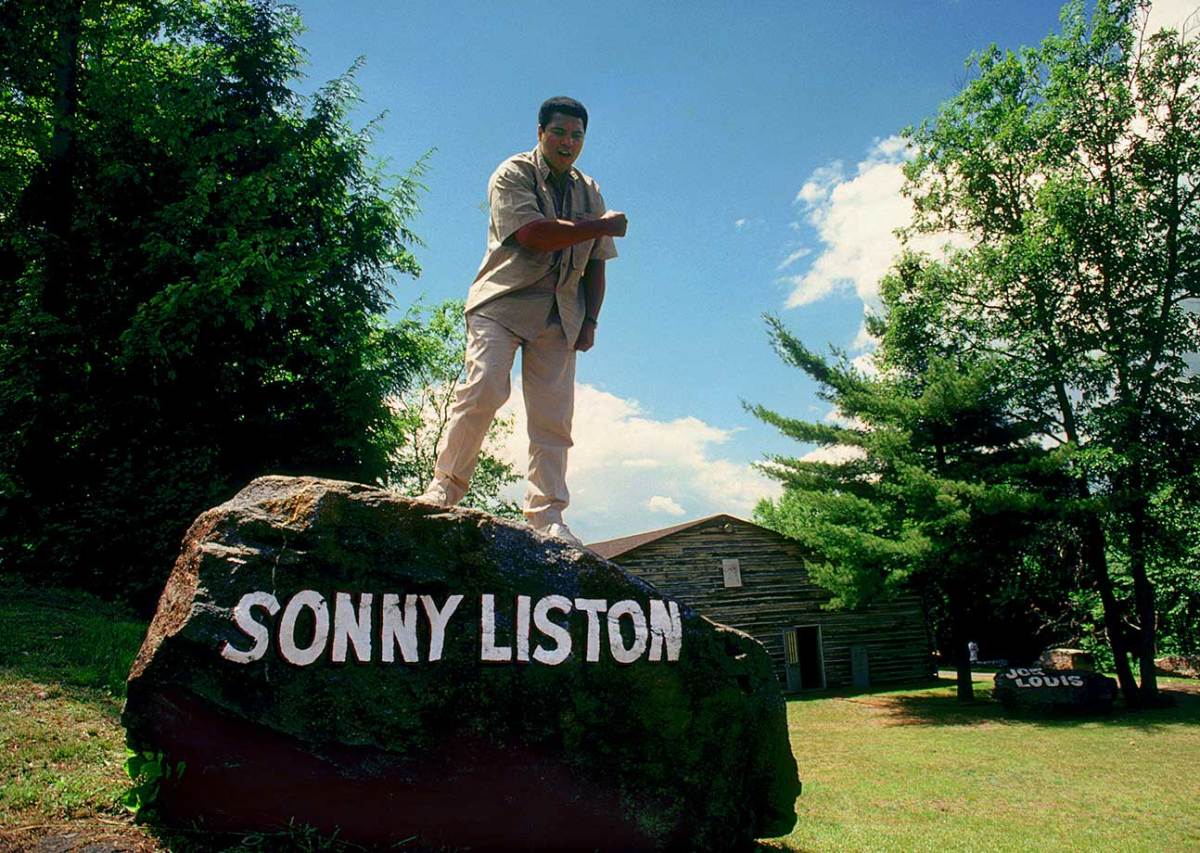

The same year, Ali stands atop of the Sonny Liston rock at his old training camp cabin. Ali and his father painted the names of famous boxers he admired on 18 boulders at the camp.

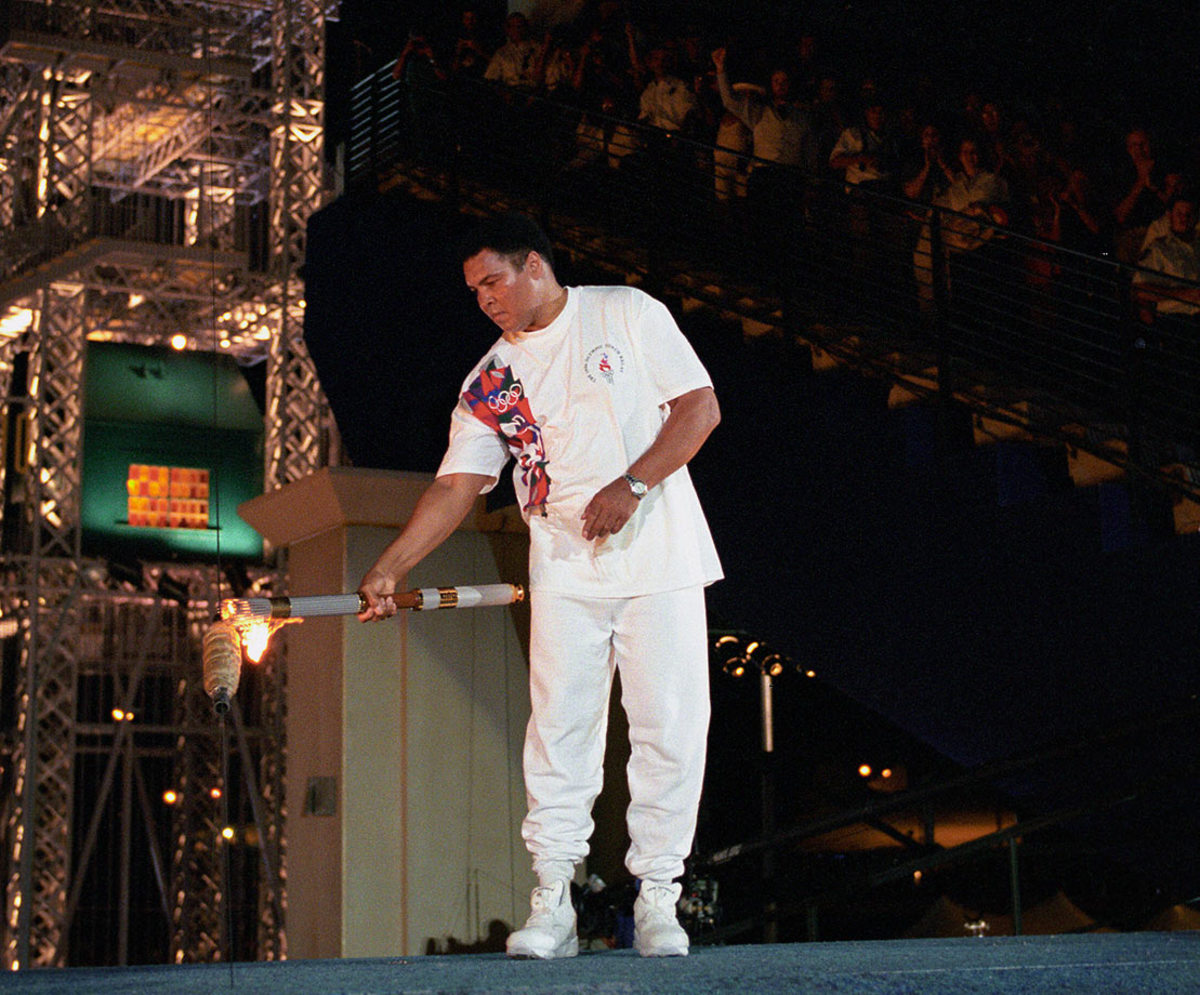

Ali carries the Olympic torch inside Centennial Olympic Stadium at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Despite trembling hands, Ali had the honor to light the Olympic flame in the stadium.

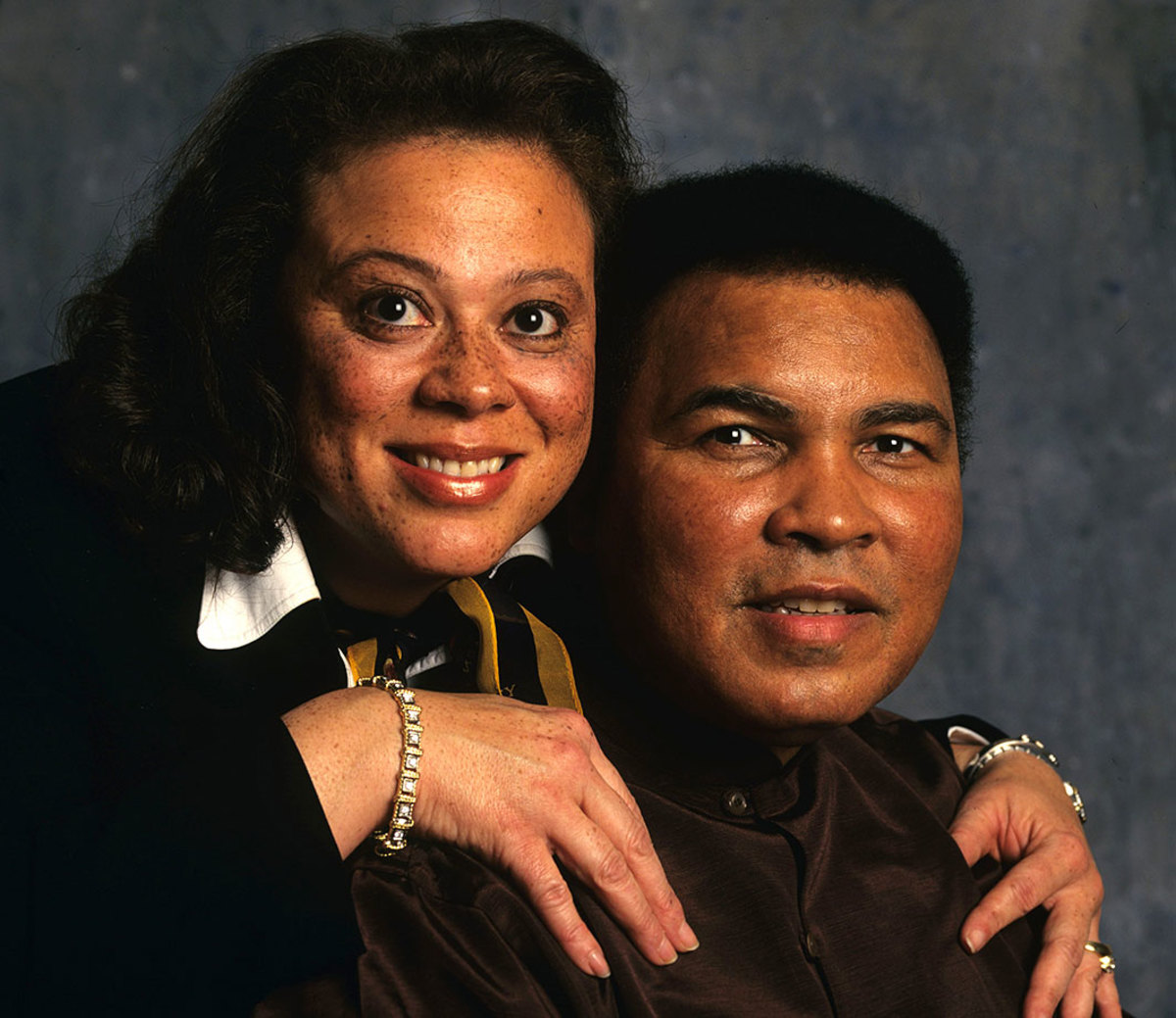

Husband and wife pose for a portrait during a photo shoot in 1997. Muhammad and Lonnie married in 1986 and have an adopted son together, Asaad Amin Ali.

Ali messes around with actor Billy Crystal during a photo shoot in 2000. Crystal's impression of Ali was notorious, and he performed at a tribute to the boxer on his 50th birthday in December 1991.

Ali lies on the canvas as his son, Assad Amin Ali, stands over him invoking memories of Ali's victory over Sonny Liston during a photo shoot in the gym at his farm on Kephart Road near Berrien Springs in 2001.

Fierce rivals in the ring, Ali and Joe Frazier pose for a portrait in the boxing robes they wore the night of their first bout at Frazier's Gym in 2003. Ali said after Frazier's death in 2011 that he was "a great champion."

Ali takes a punch from his daughter Laila Ali while sparring before her fight against Erin Toughill in 2005. Laila retired from her own successful boxing career with a professional record of 24-0.

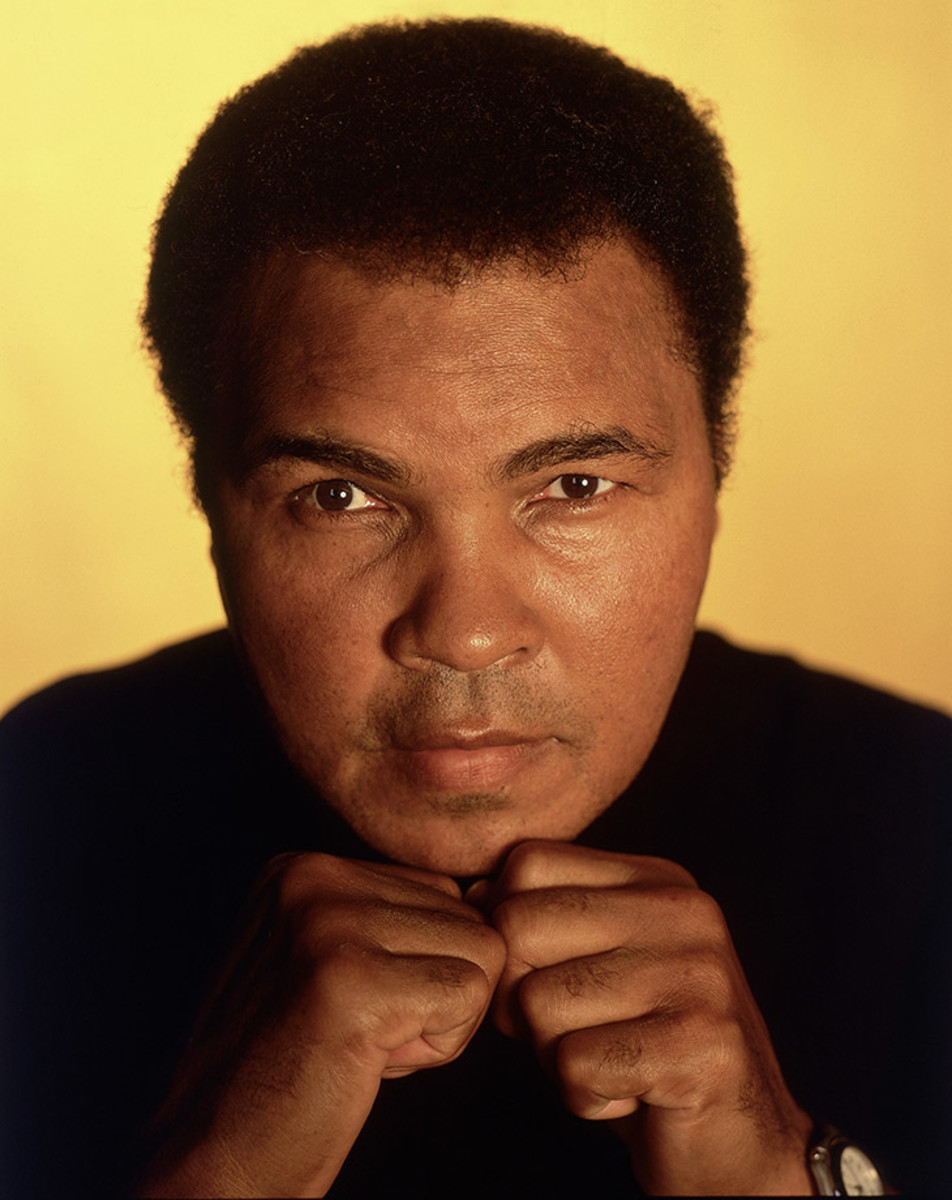

Ali poses with his fists up for a portrait in 2005.

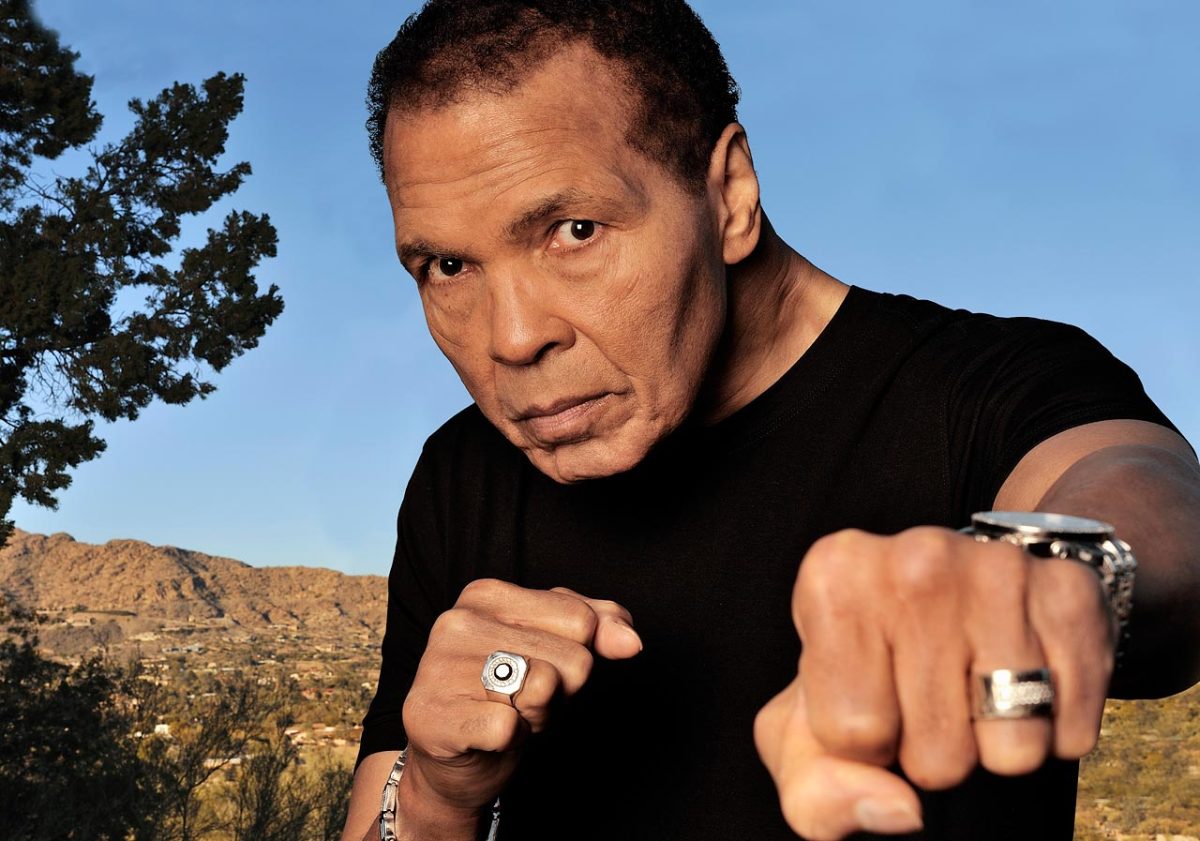

Ali poses with an extended punch in a 2012 photo shoot at his home in Paradise Valley, Ariz., to mark his 70th birthday.

Ali sits in front of a 70th birthday cake in January 2012 at his Arizona home. Later that year he appeared at the opening ceremonies for the 2012 Olympics in London to escort the Olympic flag into the stadium, 52 years after he won gold in Rome.