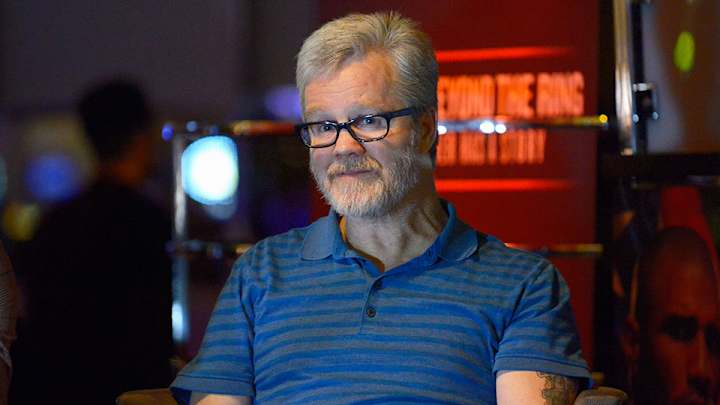

Freddie Roach prepares for the end of Pacquiao’s career—and his own

HOLLYWOOD, Calif. — The boxing lifer Freddie Roach settled into the corner booth at Musso and Frank Grill and ordered a New York strip steak, medium. He was talking about The End and how it seems worse for boxers than for athletes in other sports.

He wasn’t sure exactly why it was that way, just that it was. “In all my years as a trainer, I’ve told seven guys to retire,” he said. “Six of them told me to go f--- myself. One did retire. Gerry Penalosa. Owns like six gyms now. He did all right. All those other guys ... go f--- yourself.”

Roach knew this: The End comes suddenly in boxing. There are no teammates to mask diminished skills, no bench to ride, no complementary role that nets a championship ring. When a boxer’s skills fade—the legs always go first, then everything else—it’s obvious, even if they continue fighting.

Take Wladimir Klitschko. Roach watched him lose to Tyson Fury last November. Roach knew. “When it’s over, it’s over,” he said. “All of a sudden, nothing. You’re a contender one moment and a f------ bum the next.”

Not that Roach was any better in his own boxing career. He fought “maybe two or three” bouts too many. His last, in his hometown of Lowell, Mass., against David Rivello, felt foreign, as if he wasn’t doing what he had done his entire life. Roach said it’s the first time he didn’t try to win a fight. He attempted only to survive. He was going through the motions. Boxing isn’t a going-through-the-motions sport. He lost by majority decision and retired on the air that night.

Nearing the end of his career, Manny Pacquiao reflects on the beginning

The next year was a blur. “I got lucky,” Roach said. “I’m drunk every night. Got arrested seven times. For fighting. And then Virgil Hill asked me, Could you train me? Eddie Futch was busy. Six months later, Hill wins the world title. Right place, right time. I was better at training than I was at fighting.”

Most fighters aren’t so lucky. And that is the concern with Manny Pacquiao, Roach’s protégé, as he prepares to face Tim Bradley (for the third time) on April 9 at the MGM in Las Vegas in what is undoubtedly one of the final bouts of his career. Those close to Pacquiao worry about his finances, his generosity, the way he rarely says no to anyone, or anything. “He doesn’t talk much about The End,” Roach said. “I don’t think it’s going to happen right now.”

Roach and Pacquiao made a pact years ago. When Roach believes Pacquiao needs to retire, Roach promised he would tell him. In return, Pacquiao promised Roach that he would retire when instructed. We’ll see. Roy Jones Jr. is still fighting, Roach noted. Jones is 47. Roach shrugged. “We have an agreement, me and Manny, but I don’t see any signs of being all done yet. I mean, he’s not what he used to be. I know that. He’s still good enough to beat the top guys out there.”

In this camp, before his 66th bout, Pacquiao complained to Roach about how much harder it is to recover now, how he needed the 11-month layoff after losing to Floyd Mayweather Jr. last May. The surgery required on his right rotator cuff didn’t help. It’s harder, Roach said, for Pacquiao to spar now. He doesn’t seem as into it. But then again, he never was that into it.

“The mitts are what I’ve always gauged him on,” Roach said. “On the mitts, he’s as good as I’ve ever seen him. I told him, you can still punch like crazy if you want to. I said, we’re going with the straight left hand. You’ll knock him out just like when you knocked out Ricky Hatton. I tell him to save it some. I don’t want him to re-injure the shoulder. But everything he throws is f------ hard.”

Pacquiao will run for Senate in his home country of the Philippines. As far as The End goes, having a plan helps. Roach said Pacquiao told him that if he were to win a Senate seat he wouldn’t have time to box anymore. But Roach said Pacquiao also told him that he needs to win this fight to obtain the necessary votes.

This may also be The End again for Roach. He’s thinking about retiring from training. His back is killing him, the result of a troublesome sciatic nerve, and he doesn’t want to spend the next 20 years with severe back pain looking for another Pacquiao. Roach knows that won’t happen, that he has a better chance to win the lottery.

As promoters sold this bout as Pacquiao’s last fight, Roach told him, “Maybe I’ll retire when you retire. Maybe I’ll retire with you.” Pacquiao smiled back at him. “O.K.,” he responded.

“Someone comes in the gym every day and says they have the next Manny Pacquiao,” Roach said. “I know for a fact in all of our lifetimes we won’t live long enough to see another Manny Pacquiao. Because nobody’s going to do what he did. Titles in eight weight divisions. It’s not going to happen.”

This is how Roach wants Pacquiao’s career to end: fight Tim Bradley, win resoundingly, position himself for the Senate seat; fight Saul (Canelo) Alvarez, who is bigger than Pacquiao but struggled with Mayweather’s speed in defeat; then fight Mayweather again, with a healthy shoulder, in a rematch of a blockbuster that was the most lucrative bout in boxing history. Roach is asked, do you think Manny really could beat Floyd. He answered, “100%.”

Fittingly, Roach and his favorite boxer will approach the end together, whether their union ends after this fight or after three fights. Roach even has a similar deal with his mother, Barbara Roach. When she tells him to retire as a trainer, he will. “I don’t know,” he said. “My mother gets up at 4 a.m. She walks the dogs. Then she goes to the gym, goes home, watches TV, takes a nap.”

“I wonder if I’ll be like that,” Roach said. “But I don’t like TV that much. I don’t get up at 4 a.m. So, yeah, I wonder what the f--- I’d do if I retire. I do wonder about that.”

That’s the thing about The End, especially in boxing. It always seems like a good idea—until the next fight.

Greg Bishop is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated who has covered every kind of sport and every major event across six continents for more than two decades. He previously worked for The Seattle Times and The New York Times. He is the co-author of two books: Jim Gray's memoir, "Talking to GOATs"; and Laurent Duvernay Tardif's "Red Zone". Bishop has written for Showtime Sports, Prime Video and DAZN, and has been nominated for eight sports Emmys, winning two, both for production. He has completed more than a dozen documentary film projects, with a wide range of duties. Bishop, who graduated from the Newhouse School at Syracuse University, is based in Seattle.

Follow GregBishopSI