Whatever happened to ‘The Worst Boxer in the History of the World’?

The midday sun shines hard on Kings Mountain, a pickup truck town between the highways that cut through North Carolina’s southwestern hills. I ring the front doorbell twice, then the one on the side door under the overhang garage. There is no response but a small dog’s yapping on the inside. Minutes pass slowly outside the brick-and-vinyl split-level. I sweat a bit. I wonder if I’m in the right place.

I came here because of a YouTube video. When anyone asked why I was heading to Kings Mountain, I would show them the clip. Soon they understood.

That video, entitled The Man From Shelby and posted in 2008, has more than 90,000 views. There’s another version called THE WORST DEBUT IN BOXING HISTORY that has more than 330,000. Worst Boxer ever. Tidy Mullet has more than 60,000. The most popular version is called Worst Boxer in the History of the World ...epic mullet!!! and features Quebecois announcers, jump-cuts to a shocked Beyonce and to a cat fighting a chicken, as well as “Eye of the Tiger” playing in the background. In nearly six years online it has been viewed more than three million times.

It was The Man From Shelby that I came across one idle afternoon, while stumbling down an Internet rabbit hole of listicles about the worst boxers of all time. Even within that genre, so much of the video struck me: The man from Shelby’s mustache and, yes, his tidy and epic mullet above an everyman build and a patch of chest hair. The claim that he was making his professional debut. His flailing kangaroo punches. The open derision from the television commentators. The inevitable conclusion after 56 seconds, when he got tagged with a left hook and then nailed by an overhand right that spun him straight up like a Looney Tunes character. The way his assailant shrugged as he collapsed to the mat. The slight smile after he climbed back to his feet. That all of this was broadcast on national TV as part of the USA Network’s Tuesday Night Fights.

How could this have happened? What sort of process could produce such a mismatch on such a stage? And whatever became of “the world’s worst boxer,” whose real name was Brian Sutherland? I took to Google. I found blog posts from a few years ago yukking it up over the video, an ironic following on boxing message boards, comparisons to another mulleted Shelby native, the fictional Kenny Powers of HBO’s Eastbound & Down. I pulled up the entry for Sutherland on BoxRec, the sport’s online encyclopedia. He had no fights after this knockout in 1993, but there had been one 10 days before, another first-round KO loss, this one to a heavyweight with a career record of 17–102–2. There were no local newspaper stories on either fight from then or now. The only social media accounts I found belonged to other Brian Sutherlands or were obvious fakes made by jokesters taken with the YouTube clips. I couldn’t find a real trace of the man himself.

Over the next few weeks, my curiosity stayed piqued. Here was a man whose life briefly and bizarrely caught the light, who got knocked out, receded into anonymity, and was unwittingly thrust back into the public eye to be laughed at two decades on. The more I watched the clip, the more I wanted to find out: What was the story of the man from Shelby?

*****

When Kenny Rainford peered toward his opponent’s corner that night in Bay St. Louis, Miss., the man he saw didn’t add up to the myth he’d heard. His only scouting report for Brian Sutherland had been derived from hearsay: that Sutherland had once gone the distance with a heavyweight; that some guy had been yapping in the hotel lobby about how he couldn’t wait to whup that Englishman; that Sutherland’s street-fighting credentials included killing a man.

The 26-year-old Rainford himself had been recognized as a contender early on. He grew up poor in a seaside town outside Liverpool, where he worked part-time as a farmhand from the age of 11 and fell in love with boxing on TV. As his frame filled out in his teens, he began hanging around Liverpool boxing gyms, absorbing the culture and technique. After leaving school at 16, he worked as a plasterer and then a nightclub bouncer before beginning to box in earnest, piling up amateur wins and a handful of one-punch knockouts. He befriended a British cruiserweight and tagged along to his training camps, where he would occasionally step into the ring to spar. One such session caught the eye of an American trainer named Beau Williford. At 25, Rainford moved to Lafayette, La., to live in Williford’s house and train full-time to become a pro.

Williford, a former national amateur champ who sparred with Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier before opening the Ragin’ Cajun Boxing Club, was well known in the fight game. Rainford reveled in the work Williford put him through: the six-mile runs in the bayou humidity, afternoons spent chopping wood, relentless sessions in Williford’s bare-bones gym known affectionately as the Torture Chamber. The kid could hit like a mule, thumping the mitts so hard that other gym-goers often stopped to watch him train, but he’d come out gun-shy under the lights. Through his first three professional bouts, he was 2–1, splitting a pair of decisions and winning on a TKO.

The fight against Sutherland in Mississippi would offer his biggest exposure yet—except Sutherland was never supposed to be his opponent.

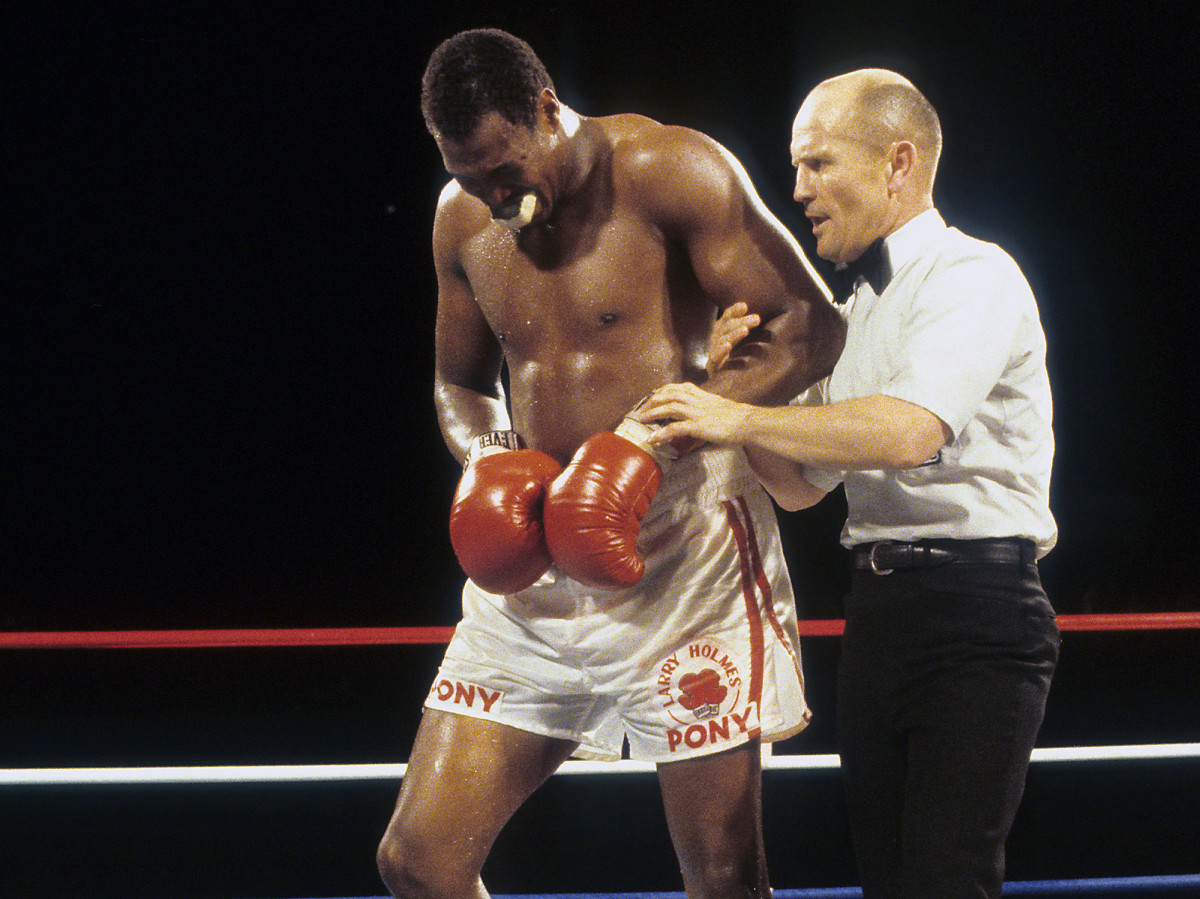

Former heavyweight champ Larry Holmes, recently coaxed out of a second retirement, headlined the card in Bay St. Louis and attracted the USA Network broadcast. Tuesday Night Fights was no slapdash enterprise or content-filler—this was a primetime program on basic cable’s most-watched station. Before the rapid expansion of cable lineups and the proliferation of satellite, such things carried significant weight: Around the time of the Rainford-Sutherland bout, TNF was drawing Nielsen ratings of 2.5, a share equivalent to many primetime network programs today.

LeBron James chases the ghost from Chicago and basketball immortality

The aims of the card’s promoters were dual: to help Holmes earn one more title shot, and to use the TV exposure to promote host site Casino Magic, a barge floating off Mississippi’s Gulf Coast and a key player in the state’s newly legalized gaming industry. To fill the remainder of the card, Williford was hired as matchmaker. Rainford, his star pupil, was given a featured spot.

During the week preceding the fight, Rainford joined Holmes for his daily 6 a.m. runs, mining the former champ’s mind for advice before studying his workouts at the gym. But the day before his match, Rainford’s original opponent was scratched for reasons unknown—an injury, sickness, or some other cause lost to time. A new opponent would be needed. This is a familiar predicament in boxing; every manager or trainer has a story about some schmo being flown across the country in the afternoon to get obliterated in a prelim that night. But the remoteness of Bay St. Louis, reachable to out-of-staters by a flight into New Orleans and then a puddle-jumper to Gulfport, made the prospect of wrangling an outside replacement dim and expensive. Williford grew worried.

But he was in luck. Abdullah Muhammad, a trainer from Atlanta with two fighters on the card, said a young boxer had ridden to town with his crew, hoping to soak up the experience. Williford trusted Muhammad, whom he knew from their time together long before at Gleason’s Gym in New York. Still, Muhammad couldn’t vouch for this new guy’s abilities—he’d never seen him so much as throw a punch. But he was already there, and the opening bell was growing closer, and Brian Sutherland would have to do.

Rainford, eyeing Sutherland from across the ring, was careful to not write off a boxer based on his looks. His trainer felt no such qualms. Watching Sutherland shadowbox in his corner before the opening bell, Williford flashed to the sitcom Sanford and Son and an elderly Redd Foxx putting up his dukes in jest. A glance at Sutherland’s slipshod footwork confirmed his suspicions. Williford leaned in and whispered into Rainford’s ear. “The faster you can get out of there,” he told his protégé, “the better it’ll be for everybody.”

*****

A maroon minivan rolls into the driveway in Kings Mountain, then veers onto the front lawn to park. On the trailer in tow is an upturned black leather couch strapped over a washer/dryer. Out from the van’s passenger side lumbers the man from Shelby. There is no mullet—his hair is closely shorn, his face clean-shaven, his body stout. He wears a red T-shirt, dark jean shorts, and black high-tops with white socks bunched at the ankles. He extends his hand. “Brian,” he offers as an introduction. He apologizes for his slight tardiness; he was helping his brother Steven, whose house this is, pick up some furniture in Charlotte. An accident clogged I-85. “That place was a mess goin’ down there,” he says. “Come on in.”

An excitable Yorkie greets us at the door. We sit at a small kitchen table under a whirring ceiling fan while two orange tabbies wander around our feet. Finding Brian was hard, then easy. None of the other players from that night in Mississippi knew what had happened to him, or even who would. Public records turned up a slew of addresses, but no one at any of the listed phone numbers recognized the name. Local newspaper editors had never heard of him. Finally I came across an old birth announcement in a newspaper archive naming him as the father. I searched the son’s name on Facebook and found a profile; the son had a recent post tagging his father, whose own profile hadn’t turned up in my searches. Brian’s page listed his employer as Pep Boys. I called the store closest to Shelby, his billed hometown as a boxer, and there he was. I asked if he would want to talk to me about his story. He said he’d love to.

He chose to meet at his brother’s house because he says it’s more accommodating than his own. Brian spends much of his time here anyway. He’s even got a speed bag out back by the above-ground pool that he used to hit when he needed to let out some anger. He says he doesn’t need that so much now.

For 20 minutes Brian tells me about his origins as a fighter: watching Ali-Spinks with his daddy, scuffles with school-bus toughs, relishing the Rocky movies and dreaming that he might live their fiction. He tells me he was an angry boy, then reveals the source of his anger. “I got abused when I was little, at home,” he says, his voice getting low and serious. He describes the way his mother had pinned him down and slammed his face into the floor, leaving him black and blue. He says she once used the solid wooden door of a closet to do the same job. Another time, he remembers, she grabbed a wooden ax handle and planned to crack it across his skull, except this time his father intervened.

Two of Brian’s siblings confirm the abuse suffered by their brother, independently recalling some of the same anecdotes. While they all got what they call whoopings, they do not have theories as to why Brian, the second of the family’s six children, received their mother’s worst. “She was mad at my dad,” says one sibling. “If my dad would come home later than he should have, or—just anything. She took a lot of anger out on [Brian], which we couldn’t do anything about. We had to sit back and watch.” Reached by phone, Brian’s mother vehemently denies the accusations: “I spanked all my youngins, but I didn’t hit him like he says. He’s lying.” She says that Brian’s story about the door happened when she opened the door to a room he had run into while crying. “I don’t know what kinda lies he’s told you, sir, but I ain’t never went to court for hittin’ no youngin,” she says.

Unable to fight back against his mother in his youth, Brian says he took on just about everyone else. The classmate who impolitely described one of his sisters had his braces introduced to his lips and was left a bloody mess. Hallway wiseasses who cracked jokes about his clothes were liable to catch a haymaker. A bunch of boys on the bus started ragging on his family, so he and Steven went down the aisle and traded blows with every one of them. Six boys at a party pressed Brian against a fence and pummeled him with a 2x4, slicing open the back of his scalp and sending him to the hospital, so over the next few months he hunted them down, one by one, at the Cleveland Mall for payback. During a squabble with his older brother, Tony, Brian walloped him in the head with a telephone.

Olympic medal predictions: Picking gold, silver, bronze in all 306 events

“When I got mad, all that madness went into my fists,” Brian says. He looks down at his balled hands on the table. “When you get filled up with anger, you don’t hurt until it’s over and done.”

“He’s always looked for attention,” Steven tells me later. “He didn’t care what kind of attention it was, as long as it was attention—good, bad or indifferent.” The attention was often bad: detentions and suspensions for fighting, for skipping class, for smoking in the bathroom. At 14, Brian was nabbed rummaging through classmates’ pockets in the boys’ locker room. That infraction would change his life. He stole lunch money, he remembers testifying at the juvenile court, because he had been sent to bed without dinner. (His mother also denies this, and according to the Cleveland County courthouse, Brian’s youth records can’t be unsealed, even by him.) Social services got involved. Soon they took Brian out of his home and put him in a shelter. After that there was a group home in Grover, a Boys Town, and a foster home back in Kings Mountain. He tried to run away. He still fought.

He says a stint at a military school for juvenile delinquents straightened him out: In six months he fought only once. He finished high school there and moved to Shelby. He got a job selling newspapers, moved in with a girlfriend and her parents, and had his first baby girl. There were still plenty of scraps around town. At one point in our conversation I ask, delicately, if it’s true, as Rainford had heard, that he once killed a man in a street fight. He laughs. “That’s a new one on me,” he says. He figures that came from someone blowing smoke to burnish his reputation before his match in Mississippi. “I never heard of that. No, I don’t know nothin’ about that one. . .I ain’t never killed nobody, promise you that.”

On weekend nights he and his friends would head to a pool hall on Washington Street, the kind of smoky haunt where everyone would have a couple of cans and no one thought twice about chasing them with a couple of punches. One night two brothers said something to Brian, and Brian mouthed back. The next thing he knew he was throwing the one with the pool cue on the ground and he had the other one on his back. Soon both were lying there with nothing more to say.

Just then a man named Frankie Hines walked in. He heard the commotion and saw the aftermath and introduced himself to Brian. Frankie told him that it looked like he could fight. He offered a proposition: How would Brian like to use those fists to make some money? How would he like to become a boxer?

*****

Not all of those losses were really his. Hines swears it. North Carolina’s boxing oversight was lax in those days, which made it easy for tomato cans to show up in some backwoods armory, pass themselves off as another fighter, and score a payday to lie down and boost up their opponent’s record. So that 17–120–5 mark in the books under his name, piled up between 1980 and 2002, skews the truth. “I didn’t fight that many,” he tells me over lunch at a Golden Corral in Shelby, his twangy voice as soft as his squinting smile is easy. “I think I fought around 70, 75 fights.”

He was still fighting when he took Brian under his wing. But he’d also spent the last four or five years training fighters and promoting cards, quitting his job as a material handler at a yarn mill to do so. Trade lots and Toughman Contests were fertile grounds for prospects, to whom he promised free training; when they fought professionally, Hines would get his pay by taking a cut off the top. He developed a reputation as something of a gift-giver. When promoters came out of town looking to score a win for one of their fighters, Hines tells me, “they’ll come around and ask me.”

Few of his pupils ever won or had careers that lasted beyond a few fights. Hines acknowledges that most of them were unprepared. Why then, I ask, would he let them in the ring? “If I hold ‘em back,” he explains, “they’ll go somewhere else and get somebody else to put ‘em in the ring and fight. I didn’t have none of them under contract.”

But Brian wasn’t going anywhere. He loved the routine of training, the promise of channeling his rage into a ticket toward something bigger. By then he was 24 and a delivery driver for the Pizza Hut next to Hines’s house. Two or three days a week, he would finish his midday shift at 3 o’clock and hop over to Hines’s to join six or seven trainees on runs around Shelby or rounds against the heavy bag in Hines’s basement. Other times they’d head to a repurposed grocery store behind a pharmacy to spar in a makeshift ring. Among his typical flock of half-committed students, Hines was impressed by Brian’s consistent attendance. He was less enthused with Brian’s smoke breaks and tendency to drop his left hand. One afternoon he even tied Brian’s right hand behind his back while sparring to drive home the point. “It still didn’t work,” says Hines.

Within a few months, Brian says, he was having amateur fights in the grocery-store-turned-gym. He estimates he went 20–5. “I hurt ‘em, knocked ‘em out,” he says. (Hines says he never saw these matches.) After a few months of training, in February 1993, Brian made his actual pro debut when Hines’s business partner, Billy Mitchem, brought him to a gym in tiny Forest City, N.C. His opponent was Danny Wofford, a heavyweight trainee of Mitchem’s whose career record was then 12–24–2. There are no recorded weights for the fight, but Wofford’s typical fighting weight in that period was 214 pounds. Ten days later, at the casino in Bay St. Louis, Brian would weigh in at 177.

At the first fight, in Forest City, Brian got a thrill out of the night’s every turn: taping his hands, standing in the ring under the lights, the sight of 200 strangers in the seats hollering, all those eyes trained on him. So what if Wofford caught him with a right in the first round and knocked him down? What did it matter if Brian couldn’t understand why the ref waved it off even though he was back on his feet by the count of 10? The next time he saw Hines, he badgered him with a single question: When can I do it again?

A few days after the match, Abdullah Muhammad called Hines and asked if he had any fighters who wanted to accompany him to an upcoming card in Mississippi. Soon Brian joined Muhammad in Atlanta and rode with him in the van to Bay St. Louis, arriving there on Monday morning, roughly 36 hours before the fights. The plan was for Brian to serve in Muhammad’s boxers’ corner, providing water between rounds. He spent the first day touring the Casino Magic, getting in a couple of turns at the slots. He couldn’t believe the size of the place.

Twenty-two years later, he still shakes his head thinking about what happened the next day. His memories are no more than snapshots. Lingering in the locker room a few hours before the show, when he got word they needed him to box. Punching the air and ripping off a few sets of pushups to get loose. The shock of being told, just moments before walking down the aisle, that the proceedings would be broadcast on national TV. The greater shocks of the brighter lights and the bigger crowd and the cameraman crowding him as he hopped in place during the introductions. Sizing up Rainford as they touched gloves at center ring, taking stock of the size mismatch. The last-minute instructions from Muhammad, who served as his cornerman: “Keep your hands up, and stay off the mat.”

Bob Arum again shepherding the next generation of boxers

In some states it wouldn’t have gotten that far. It would have been easier to find a local replacement, or to fly one in. The boxing commissioner would have perhaps needed to see Brian box before granting him a license. But this card was too important to the state’s fledgling commission—attempting to revive itself after years of dormancy—and to the state’s nascent gaming industry for anything to get in the way. All it took for Brian’s approval was an application from Williford’s ever-ready stack and the payment of a small fee.

And so Brian made his way to the ring and stood in his corner, absorbing Muhammad’s advice. Roughly a minute after being told to stay off the mat, he was back in that same spot on his hands and knees, minus a tooth. For all the knockout’s theatrics, its aftermath was minimal. Brian chatted with the ringside medic from his knees. He stood and shared words with Rainford, then sat on his stool, head-in-hands. He never went to the hospital. He was not evaluated for a concussion. He simply went back to the locker room and wondered what went wrong.

The match had been taped; Tuesday Night Fights showed the main event live and filled whatever time remained afterward with delayed broadcasts of the undercard. Outcome be damned, Brian wanted somebody back home to catch his 56 seconds of fame. When his head cleared, he found a payphone near the locker room and called Steven collect. His brother was incredulous. You’re where? Doing what? But by the time Steven got his TV tuned to right channel, it was too late. The fight was over. The show had moved on.

*****

Fortunes were mixed coming out of that night in Mississippi. Larry Holmes got his title shots, in 1995 and ‘97, but lost both by decision. Frankie Hines quit training and took a job running dye jets at a clothing mill. Abdullah Muhammad trains out of a gym in Newark, while Beau Williford is still churning out hopefuls in Lafayette. A few years later Kenny Rainford broke his left hand throwing a punch in a fight’s final seconds, against an opponent who was on his way down. He came back and fought again, but retired as a professional in 2000 with a career record of 11–3. These days he works in security while training fighters and boxing semi-pro in Liverpool.

Brian went back to Shelby with a swollen eye and a story to tell his colleagues at the Pizza Hut. He lost interest in boxing. He stopped training. He got a replacement tooth on a retainer. He married his girlfriend, got divorced, did that all over again three more times. He had three more kids. He rose up to manager at the Pizza Hut. He got arrested for a fight at the mall but the charges were dropped; he got nabbed a few other times for bouncing checks and had to pay restitution. He began volunteering as an EMT and was eventually hired full-time, but got burned out on seeing people at their worst. He volunteered as a guardian ad litem in South Carolina, investigating home situations and representing children during divorce and parental rights cases, but the flashbacks the work triggered proved too much. A few years ago he started selling used cars. Last year he started working at the Pep Boys in Gastonia.

For years his fight with Rainford was a memory all his own. No one in his family saw it, nor did any of his friends. Most didn’t even know he had been boxing in the first place. There was no YouTube, no Vine, no Twitter, no social media echo chamber to keep his moment reverberating. It never even made the local papers.

For some 15 years, Brian himself had never seen the fight. Then one afternoon a few years ago Steven was watching TruTV. A clip show came on, touting the world’s worst brawlers. A voiceover introduced Brian “The Mullet Man” Sutherland. Steven couldn’t believe it. There was his brother, in a boxing ring, on TV, getting knocked out, the highlight being played over and over. Soon Steven found one of the uploads on YouTube and sent it to Brian, who was shocked.

“I remembered doing it,” Brian says, “but I didn’t expect the long-haired mullet.”

The clip made the family rounds, circulated among friends. It went viral within Shelby and Kings Mountain circles as it racked up millions of hits elsewhere. A friend of Brian’s, a deejay at the Silver Dollar down in Gaffney, just across the South Carolina border, began projecting the video on the wall during his sets. Curious strangers would approach Brian: Hey, didn’t I see you. . .? One night at a local watering hole he and his sister Sheila were recounting the tale when some folks overheard them and pulled up the video on their phones. Within minutes there were a dozen or so gathered around watching, marveling, laughing. The rest of the night Brian drank for free.

It was odd, being pulled into strangers’ consciousness like this two decades after the fact. A local news channel caught wind and asked him for an interview, but he didn’t want the attention while working as an EMT. Just about all of his coworkers have seen the fight on YouTube. They like to make their cracks: Don’t try me, or I’ll knock you out too. His siblings do the same. Brian laughs them off. “I’m a fun person,” he says. “I joke around about it and everything and they joke with me. It just passes my day on.” But later, when I ask him about the online commenters—the people driving the fight’s surprising renown, the ones posting it under descriptions such as “worst boxer ever”—he is less diplomatic. “I guess their lives are more dull than they think and they go on YouTube and find something funny and watch it,” he says. “I don’t know. I’m surprised it’s even on there now. I don’t know how that stuff works. I’m just a boy from a small town that don’t know nothin’.”

What stings, he tells me, is that he’s never been paid for any of it—not for the TruTV re-airings or YouTube views or even the USA Network broadcast. About a year ago Steven found a “contact us” form on TruTV’s website. He sent a message telling them that if they were going to keep showing his brother’s fight, they had better start sending him checks. He’s yet to hear back.

Brian says he was never paid for the fight in the first place, nor for the Danny Wofford fight before that. When I ask Hines, Brian’s former trainer and manager, about this he seems surprised. “They didn’t tell me nothin’ about that,” Hines says. “I didn’t get anything out of it.” Says Billy Mitchem, Hines’s partner at the time and the organizer of the Wofford fight: “Why would he have fought if he wasn’t getting paid?”

Brian has settled for shared laughs over what was once a dormant and private memory. And when the chuckles stop, there is a common note in his exchanges with strangers: Hey, they tell him, at least you had the balls to do it. If they don’t, he makes the point himself.

Would he have the balls again now, in the age of the viral video? No, Brian says, certainly not. He would have feared this exact fate. He was willing to enter the arena in Bay St. Louis one Tuesday night in 1993, but there was no way of knowing the world would change in such a way that the moment would be preserved in digitized amber. He could not have imagined the clicks, the views, the comments, the enduring memory of search engines.

And yet, Brian insists that he doesn’t regret stepping into the ring. He betrays no bitterness toward those who set him up to be an unwitting punchline. He doesn’t feel like a victim. He is troubled only by his lack of financial gain and thoughts of what his boxing career might have been. . .if only he’d had a better trainer. . .if only he hadn’t been so nervous when he saw the cameras. . .if only he hadn’t dropped his left.

“If I’d have beaten Kenny Rainford, I believe I’d have been another Floyd Mayweather, to be honest with you,” he says. “If I’d have won on TV, then it would’ve been the small hometown boy making it to the top. But. . .”

He shrugs, then smiles.

He is content with the life he has lived. There is no more fighting, he says, and very little anger. He lives near where the train tracks cross Kings Mountain’s center, with his girlfriend, though a few months from now they will be looking for a new place closer to Charlotte, where he is transferred and promoted to run another Pep Boys. His four children either live with their mothers or are grown and on their own. “I’m just a regular ol’ person,” he says, “who got a chance and took it.”

He pulls out his cell phone, a white Samsung, and begins searching YouTube. He calls up The Man From Shelby—not the more popular version that he usually watches, with the cat fighting the chicken and the declaration that he is the worst boxer in the history of the world. He holds the phone horizontally in both hands, then perches it on the table. The introductions begin. He goes quiet. His face is still and blank.

How often, I ask, does he watch the video?

“Every chance I get,” he says.

His eyes stay fixed on the screen.