Muhammad Ali's legacy carries on one year after his death

The following is excerpted from STING LIKE A BEE by Leigh Montville. Copyright © 2017 by Leigh Montville. Published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

The hearse was a Cadillac, black and long and shiny, which figured because Muhammad Ali always was a Cadillac man. The first money he ever spent as a professional boxer went to West Broadway Motors in downtown Louisville to buy his mother a pink Eldorado. The second money went to buy an Eldorado for himself.

He roared through a string of Cadillacs in his early life, one replacing the other. He liked them flashy, too. He had one Cadillac that contained two phones so he could call two people at once if he wanted. A Cadillac was a sign of success. Wasn’t it? He showed up one day in Chicago with a new Cadillac low rider that was so flashy a friend told him it was embarrassing just to travel with him.

“You should be in a classier ride,” the friend suggested. “A Rolls or a Bentley.”

“What’s a Bentley?” the heavyweight champion of the world asked.

This final Cadillac was a 2016 XTS, which had been modified into a hearse somewhere in Ohio. The driver was thirty-three-year-old Chase Porter, whose family owns A. D. Porter & Sons, the funeral home that also buried Ali’s mother and father. Ron Price, another funeral home employee, rode shotgun. Muhammad rode in the back in a $25,000 mahogany box.

The day—June 10, 2016—was filled with schedules and grand moments and famous people. The hearse would take a trip of slightly over twenty-three miles to cover a ceremonial route that would include a couple of highways and then travel down Muhammad Ali Boulevard, which once was Walnut Street. It would go past the Andrew Young Center, which is very close to the Muhammad Ali Center, past the Beecher Terrace housing complex and past Central High School and past the Kentucky Center for African American Heritage and past 3302 Grand Avenue, Muhammad Ali’s boyhood home, which has been restored as a museum. The procession would continue past all kinds of memories, big and small, would accompany the famous man straight down Broadway past various public buildings that were important in his life. The finish would be Cave Hill Cemetery.

Former heavyweight champions Mike Tyson and Lennox Lewis and actor Will Smith, who played Ali in a movie, would be among the pallbearers at the private graveside service. A public memorial then would be held at a fifteen-thousand-seat arena named after a string of fried chicken restaurants, the KFC Yum! Center, maybe the first memorial service ever held in a building with an exclamation point in the middle of its name. Tickets for this event had disappeared in the blink of a civic eye, every seat filled. Former president Bill Clinton, comedian Billy Crystal, and news host Bryant Gumbel would be among the speakers. Senior advisor Valerie Jarrett would read a statement from President Barack Obama, who had to attend his daughter’s high school graduation in Washington, D.C.

ESPN and TV One and Bounce TV all would carry the proceedings live. Millions would watch. Millions more, maybe billions around the world, would see at least a part of what took place on news reports. People in Louisville would stand and stare, laugh and cheer, maybe cry a little bit as the procession passed. Flowers would be thrown. Affection would be public and unforced.

Buy Now

Sting Like A Bee

by Leigh Montville

An insightful portrait of Muhammad Ali, centered on the cultural and political moments in a life that was as high profile and transformative as any.

This was the send-off from this mortal coil that a head of state would receive. The funeral of a top-level movie star, a pop singer, might contain some of the same elements. Michael Jackson came to mind. A boxer had it here. A boxer. There hadn’t been a funeral for an athlete in America this big probably since the one for Babe Ruth, who lay in state for two days and nights at Yankee Stadium in 1948. This was special. This was different. This was Muhammad Ali.

The first rose landed on the windshield of the 2016 Cadillac XTS almost as soon as the procession began. Chase Porter tried to sweep it off with his windshield wipers. A streak was spread across the glass. Roses would be a problem for the entire trip.

“Windshield wipers aren’t to remove flowers,” Porter said later to the writer from the New York Times.

The New York Times. This was not about a boxer at all. This was much bigger than that.

He was not an extremely old man when he died, seventy-four, same age as Bernie Sanders, who still was running for president, but it seemed as if Muhammad Ali had been old for a long, long time. Disease does that. He had begun to be compromised in the last two fights of his career. He was thirty-nine when he retired. That meant he had been sick, getting sicker, for more than thirty-five years.

The Parkinson’s disease gave him a tremor, a shake, that only grew worse with time. His movements became more and more restricted until the last few years when he hardly could move at all. The slur in his voice became worse and worse until he could not talk.

The only part that grew larger, better, was his aura. There was no stopping his aura.

Sweet Jesus, there wasn’t.

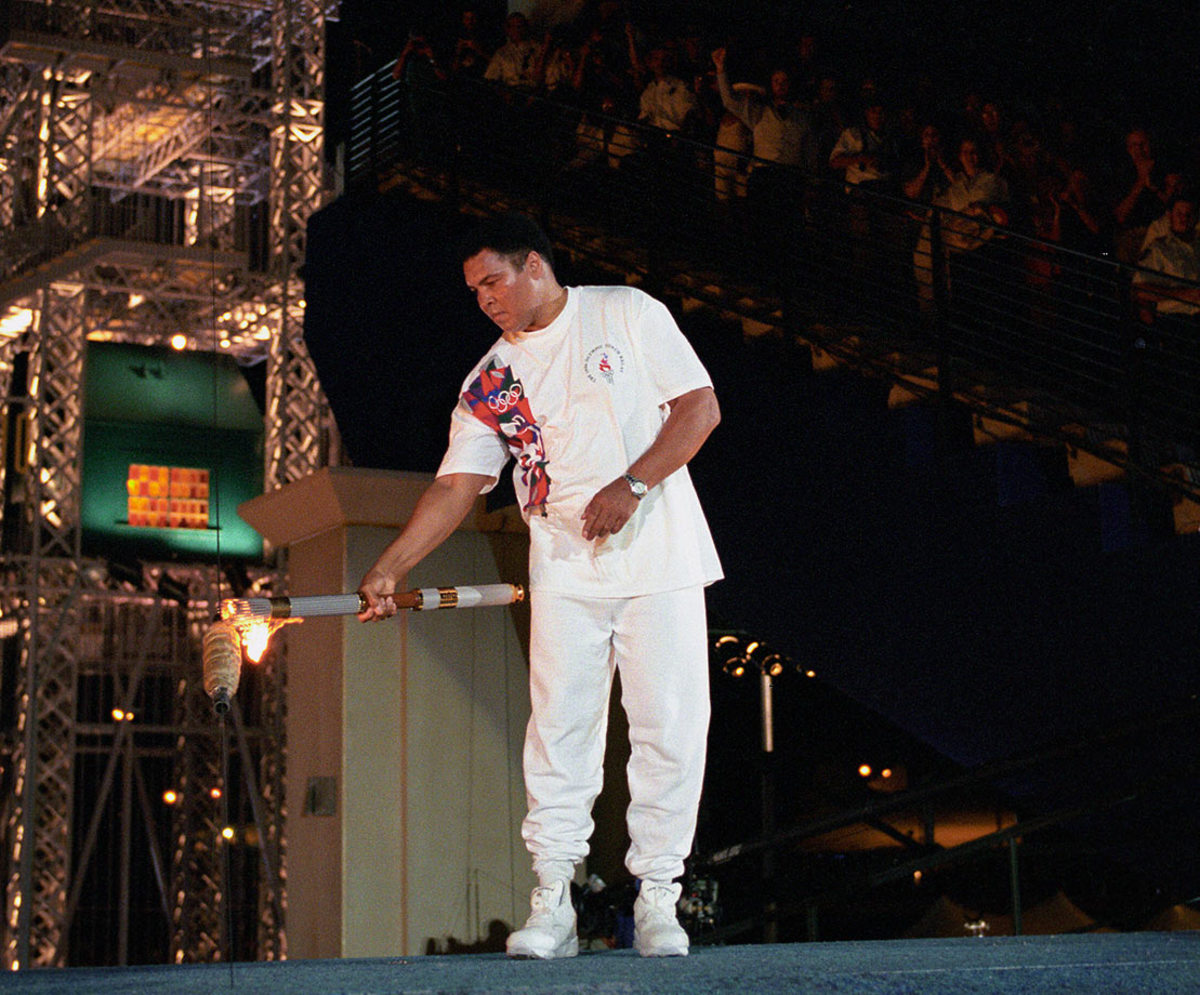

The years passed and he became a secular saint. He was a postmodern Mother Teresa, shuttled around the world to minister to the masses. He lit the torch at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, and there were quiet sighs mixed with cheers in every time zone on earth. He negotiated with despots to free hostages, didn’t even have to say a word; just his presence was a convincing argument. He was a symbol of unity and possibility.

Everyone can get along. That was the unspoken message assigned to him in his later years. He was the black man who didn’t disrupt the most segregated neighborhood. He was the Muslim who didn’t want to blow up anything except injustice. There was a universal acceptability to him. Is that the word? Acceptability? He was a night light in what often seemed to be a very dark room.

“Ali did more to normalize Islam in this country than perhaps any other Muslim in the history of the United States,” Sherman Jackson, a Muslim scholar, said when he spoke at the Jenazah, the Muslim funeral service held a day before the large service. “Ali made being a Muslim cool. Ali made being a Muslim dignified. Ali made being a Muslim relevant. Ali put the question of whether a person can be a Muslim and an American to rest.”

“He dared to love black people at a time when black people had a problem loving themselves,” Reverend Kevin Cosby, a Louisville pastor, said at the big service. “He dared to affirm the beauty of blackness.”

His silence in his later years allowed him to say more than he ever said in those rapid-fire pronouncements of his youth. He could be anything and everything people wanted him to be. His inactivity kept him out of trouble. There were no more divorces, no more controversial headlines. He couldn’t be found in Las Vegas in his declining years with young women and champagne and strange chemicals in the glove compartment of a rental car. He was on an island of purity, clean as everyone hoped an idol and role model would be. His most noted indulgence for the longest time was performing amateur magic tricks, pulling a coin from some adoring kid’s ear.

The $80 million Muhammad Ali Center, opened eleven years earlier, was a monument to this perfect life. It resembled a presidential library, a patriotic or religious shrine. Boy Scouts and 4-H club members and busloads of inner-city kids could be shuffled through exhibits that preach the power of positive thinking. He did it! You can, too! Get working! The motto for the center was “Be great. Do great things.” Mentioned often were “The Six Core Principles”:

Confidence—Belief in oneself, one’s abilities, and one’s future.

Conviction—A firm belief that gives one the courage to stand behind that belief, despite pressure to do otherwise.

Dedication—The act of devoting all of one’s energy, effort, and abilities to a certain task.

Giving—To present voluntarily without expecting something in return.

Respect—Esteem for, or a sense of the worth or excellence of, oneself and others.

Spirituality—A sense of awe, reverence, and inner peace inspired by a connection to all of creation and/or that which is greater than oneself.

Who could argue with any of that? Who?

“This bolt of lightning, this combination of power and beauty . . . ,” the comedian Billy Crystal said in a well-received eulogy. “We’ve seen still photographs of lightning at the moment of impact. Ferocious in its strength. Magnificent in its elegance. And at the moment of impact, it lights up everything around it so you can see everything clearly. Muhammad Ali struck us in the middle of America’s darkest night, in the heart of its most threatening gathering storm. His power toppled the mightiest of foes and his intense light shined on America and we were able to see clearly injustice, inequality, poverty, pride, selfrealization, courage, laughter, love, joy, and religious freedom for all. Ali forced us to take a look at ourselves, this brash young man who thrilled us, angered us, confused and challenged us ultimately became a silent messenger of peace who told us life is best when you build bridges between people not walls.”

Wow.

He had been on Facebook pretty much until the day he died. Well, someone had been on Facebook for him. Every third or fourth day, a message would be sent through the electronic air. Sometimes it would be the commemoration of an event—fifty years, say, since he starched Henry Cooper for the second time—but usually it would be a piece of advice for modern living.

“In the ring I can stay until I’m old and gray because I know how to hit and dance away.”

“Eyes on the prize.” “The fight never stops.”

“Outrun the people who stop because of despair.”

“If my mind can conceive it, and my heart can believe it—then I can achieve it.”

“Give everything your best shot.” “Team work makes the dream work.”

“It’s hard to be humble when you’re as great as I am.” “Love is the net where hearts are caught like fish.” Wow.

The rough-edged, controversial character at the core of all this devotion was hard to glimpse through the haze of adoration in the days after his death. Flaws are not usually chiseled in marble. The time when he was loud and confident and half crazy with energy, when he startled and threatened his country, when he became known around the world, seemed like it happened long, long ago. There were constant mentions of it, for sure, stories that were told, black-and-white video clips that were shown, but when the clips were finished after a fuzzy minute or ninety seconds, the cameras returned to the pixilated present, sharp and clear on the screen.

The past could not compete. Jim Brown, the football great, or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the basketball great, would tell a story, make an observation. Pictures of the Thrilla in Manila or the Rumble in the Jungle or some other moment—there he is with the Beatles—would be shown. Ali himself would shout outrageous stuff, funny stuff, straight into the camera. It was all interesting, great, but black-and-white and dated. He could have been Winston Churchill talking about D-Day, Jimmy Stewart talking about the banking business in Bedford Falls, New York. The news or SportsCenter or whatever was the program of the moment would return sharp and crisp, digital, perfect color, today.

There was no context. There was no urgency.

There was no frame of reference.

The fighters from his time pretty much were gone. Joe Frazier was gone. Sonny Liston was gone. Ken Norton. Floyd Patterson. Henry Cooper was gone. Ernie Terrell. Cleveland (Big Cat) Williams. Archie Moore. Jerry Quarry. Oscar Bonavena was long gone. Ron Lyle. Jimmy Young. A bunch of fighters were gone. A bunch of sparring partners. Big Mel Turnbow. Jimmy Ellis. Eddie (Bossman) Jones. Gone.

The people who had been around him were gone. The cook, Lana Shabazz. The little guy, Sarria, who gave him rubdowns. The guy who guarded his body, the guy who found him entertainment in the night, the guy who carried the water bucket. Gone. Bundini Brown, noisy and unforgettable, gone for a while. Trainer Angelo Dundee, the voice of reason, was gone. The eleven white businessmen from Louisville who backed an eighteen-year-old Cassius Clay at the start of his career, who negotiated his course to the title, were gone. All eleven of them.

Malcolm X, of course, had been gone for a long time. The Honorable Elijah Muhammad was gone. Herbert Muhammad, Elijah’s son, who became Ali’s manager and confidant, was gone. Howard Cosell was gone. People today didn’t even know who Howard Cosell was. Don Dunphy was gone. The entire layer of famous sportswriters who criticized Ali mightily—Red Smith and Jimmy Cannon and Jim Murray and Dick Young and the rest—was gone. The talk show titans who loved him, easy money, easy conversation, Johnny Carson and Merv Griffin and Mike Douglas, the guy from Philadelphia, had been gone for a while. Norman Mailer, who was fascinated by him, was gone. Budd Schulberg was gone. Alex Haley was gone. Sinatra! Sinatra loved him. Sinatra was gone. Elvis was gone. James Brown and Sam Cooke.

Stokely Carmichael and Martin Luther King and H. Rap Brown and Lester Maddox and J. Edgar Hoover and Richard Nixon and Lewis

B. Hershey, head of the Selective Service. Gone. The judges from all his cases were gone. All nine of the judges from the Supreme Court who decided on his case were gone. The members of all those important boxing commissions who made all those important decisions were gone.

A bunch of the places from his time were gone. The 5th Street Gym in Miami was gone. The old Madison Square Garden was gone. The old Yankee Stadium was gone. The Houston Astrodome, the Eighth Wonder of the World, was vacant and falling down. A case could be made that boxing was gone, probably an overstatement because boxing always will survive in some elemental fashion, the cockroach of organized sport, but the heavyweight division certainly had been gone for a long while in the United States.

The Vietnam War was gone. Dusty history. President Obama had walked down the streets of Hanoi less than three weeks earlier, walked with some of those remaining Viet Cong, who were pretty old now. The civil rights problems were gone, replaced with other civil rights problems, no doubt about that, but water fountains and restrooms and restaurants and hotels and schools and public transportation and voting booths and a whole bunch of other stuff now were protected by law from discrimination. The talking points were gone, the talking points from Ali’s time.

A whole lot was gone.

SI's 100 Greatest Photos of Muhammad Ali

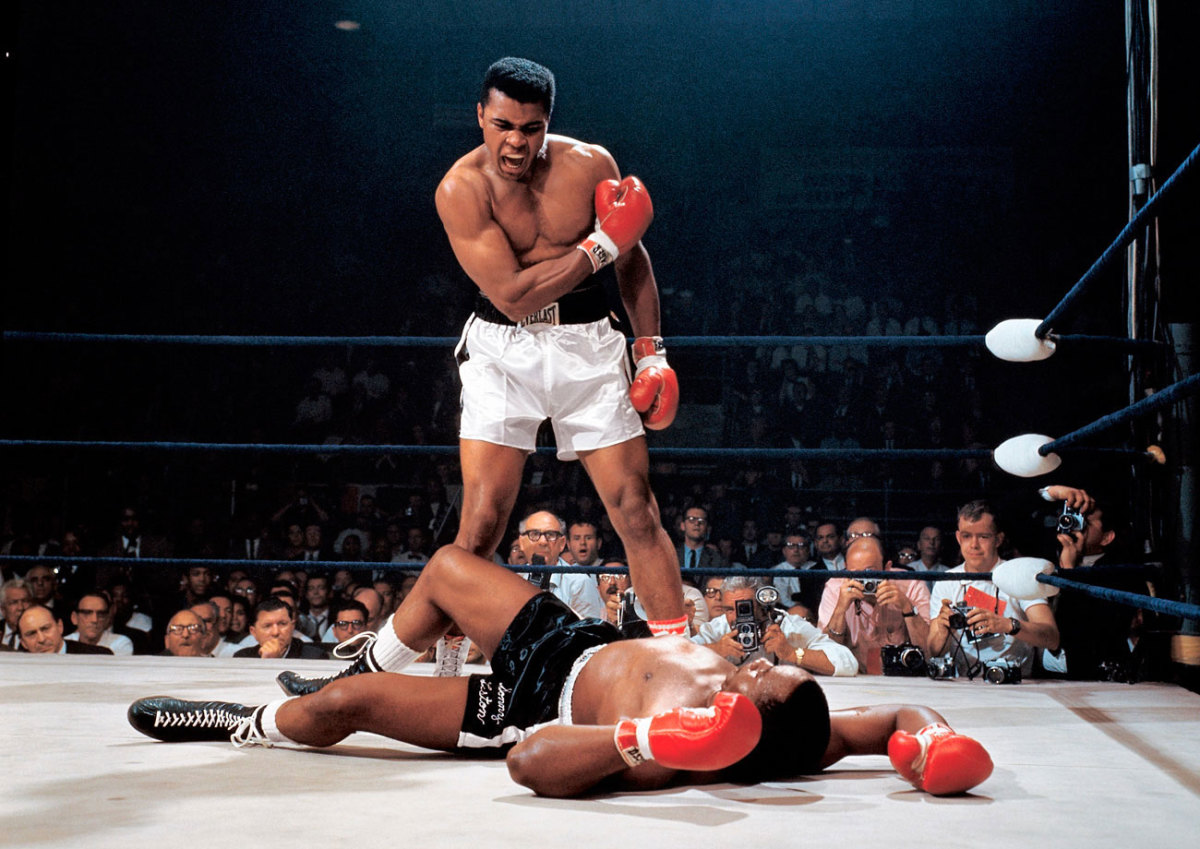

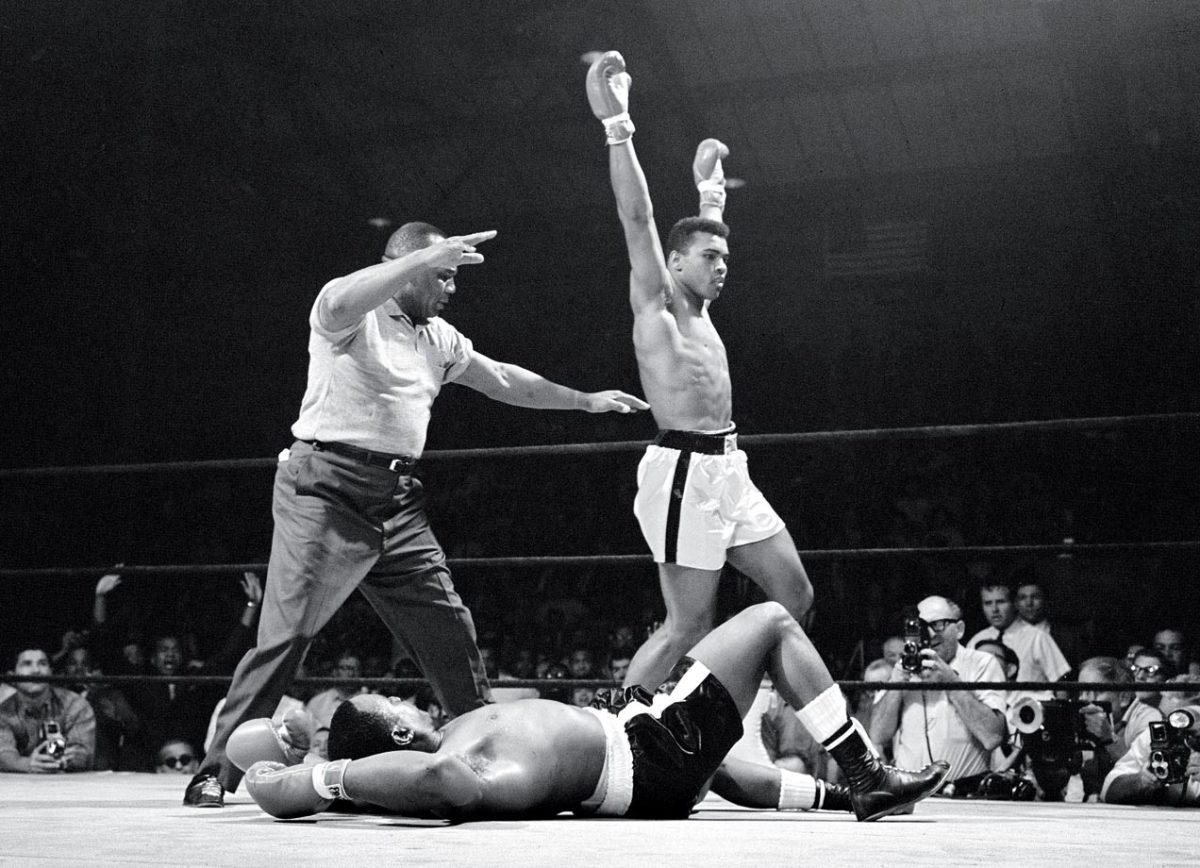

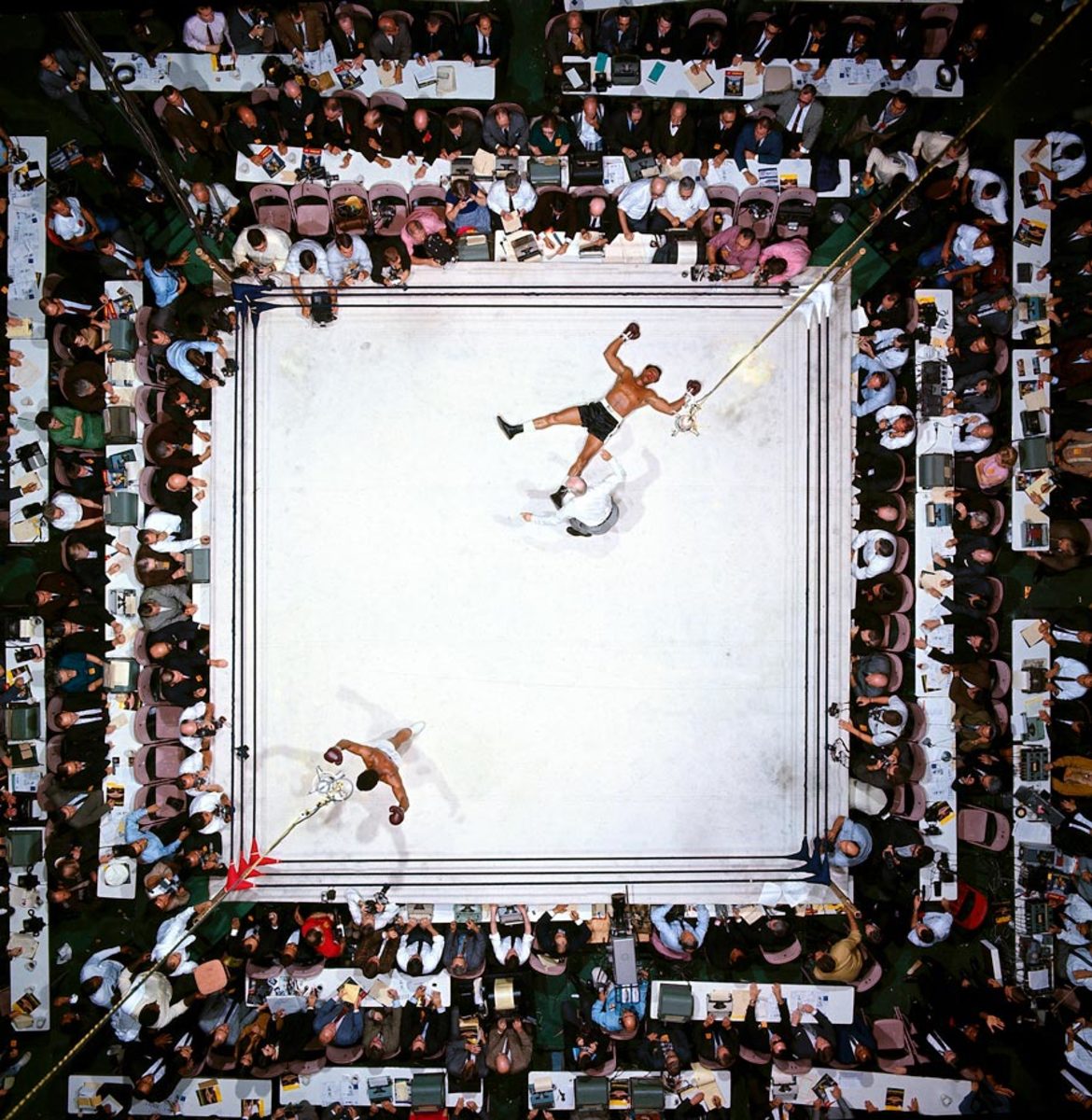

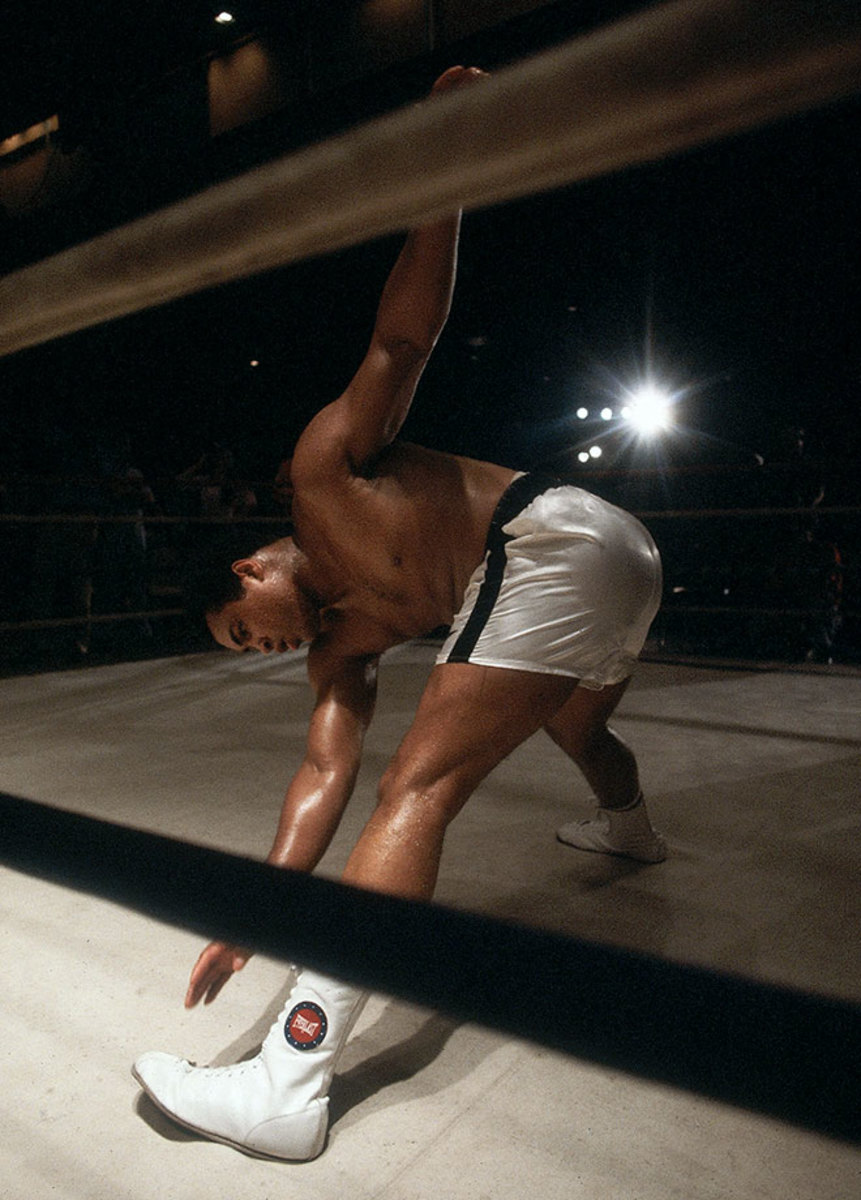

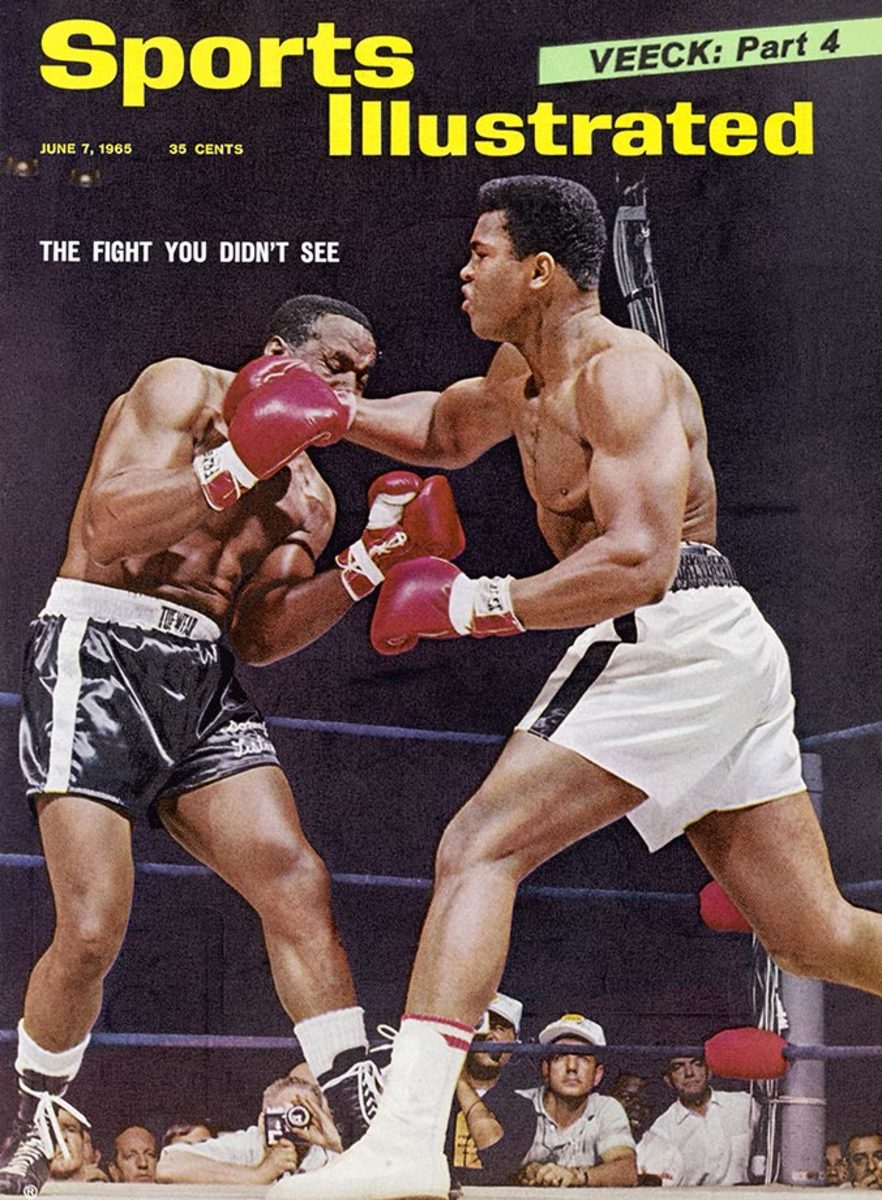

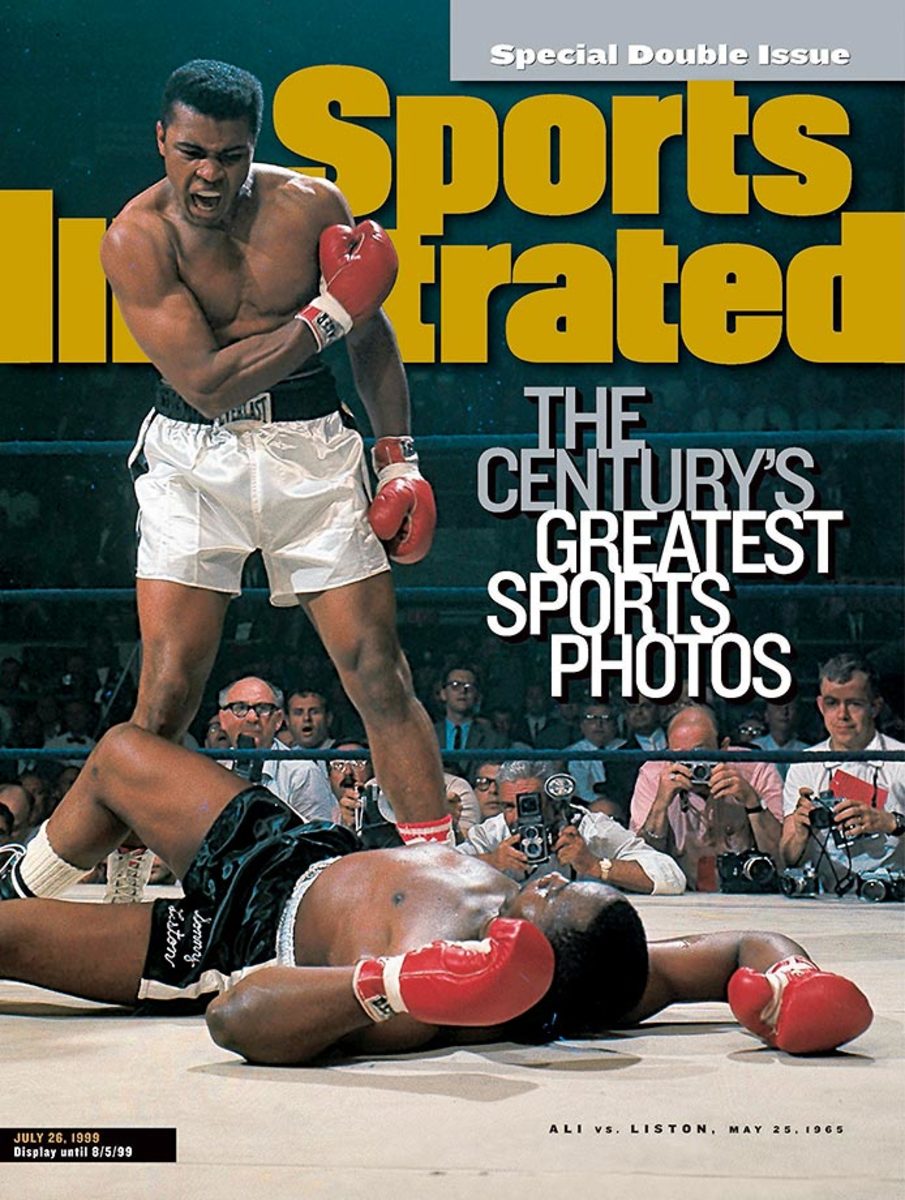

In one of the most iconic and controversial moments of his career, Ali stands over Sonny Liston and yells at him after knocking the former champ down in the first round of their 1965 rematch. Skeptics dubbed it "the Phantom Punch," but films show Ali's flashing right caught Liston flush, knocking him to the canvas. Refusing to go to a neutral corner, Ali stood over Liston and told him to "get up and fight, sucker."

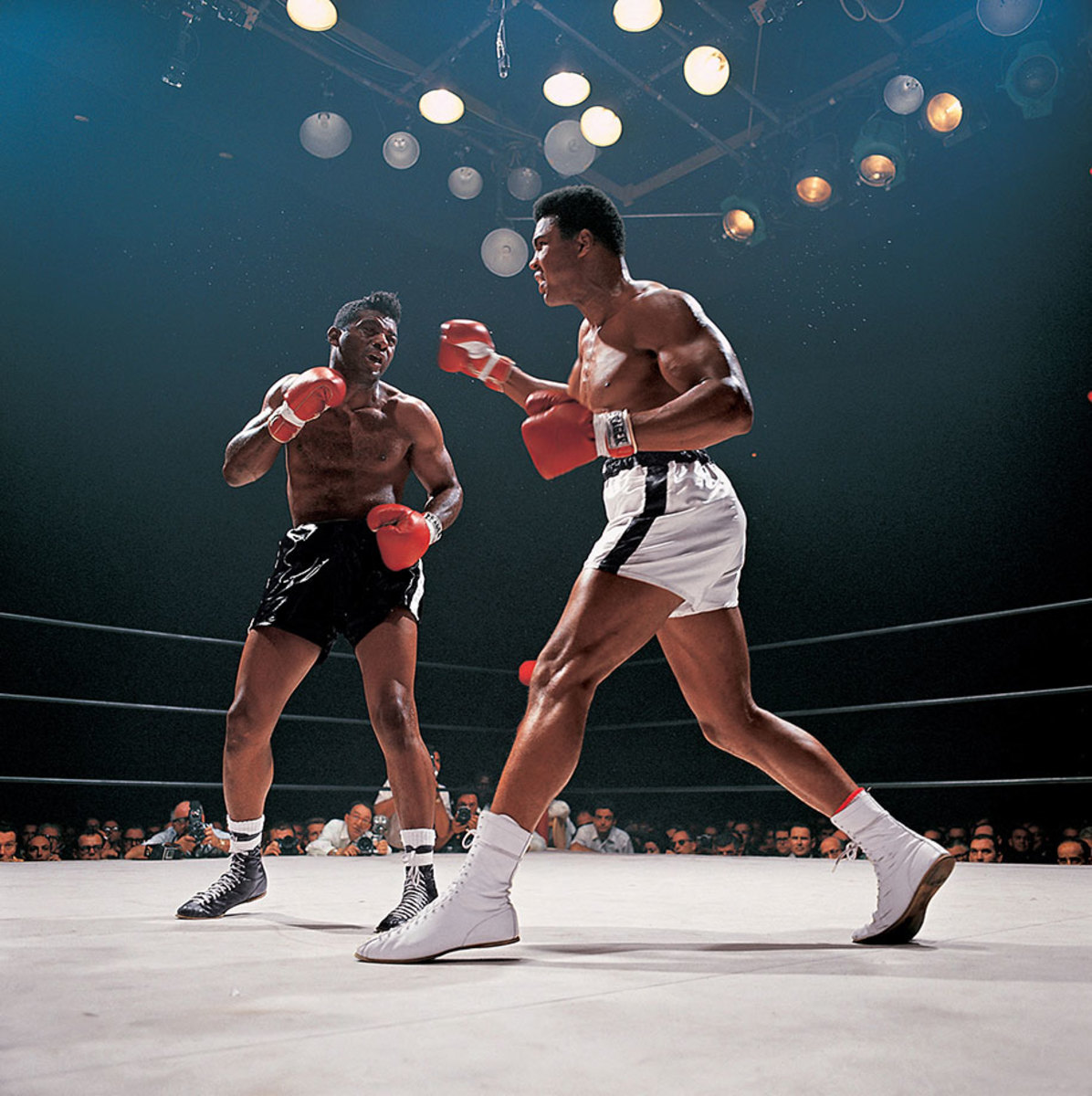

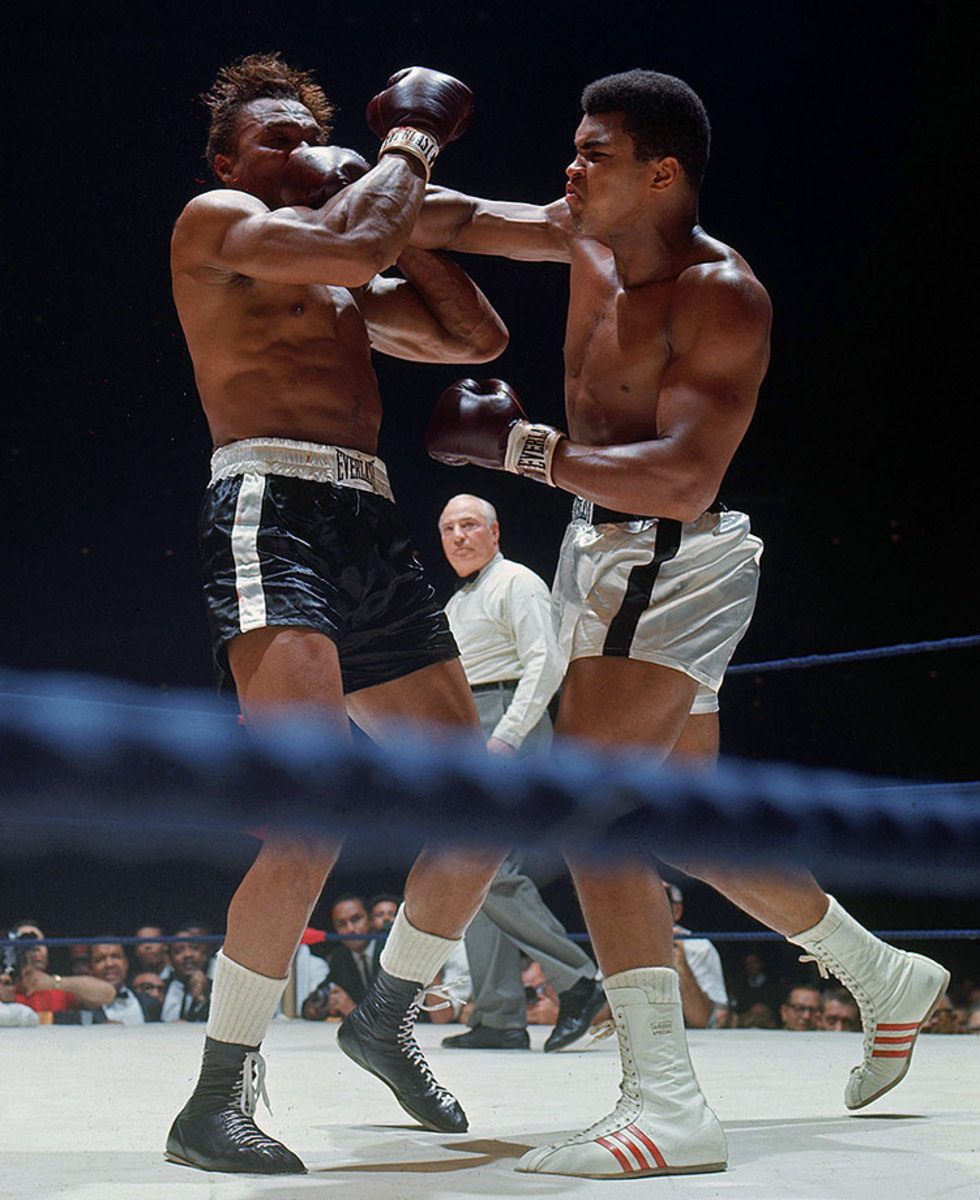

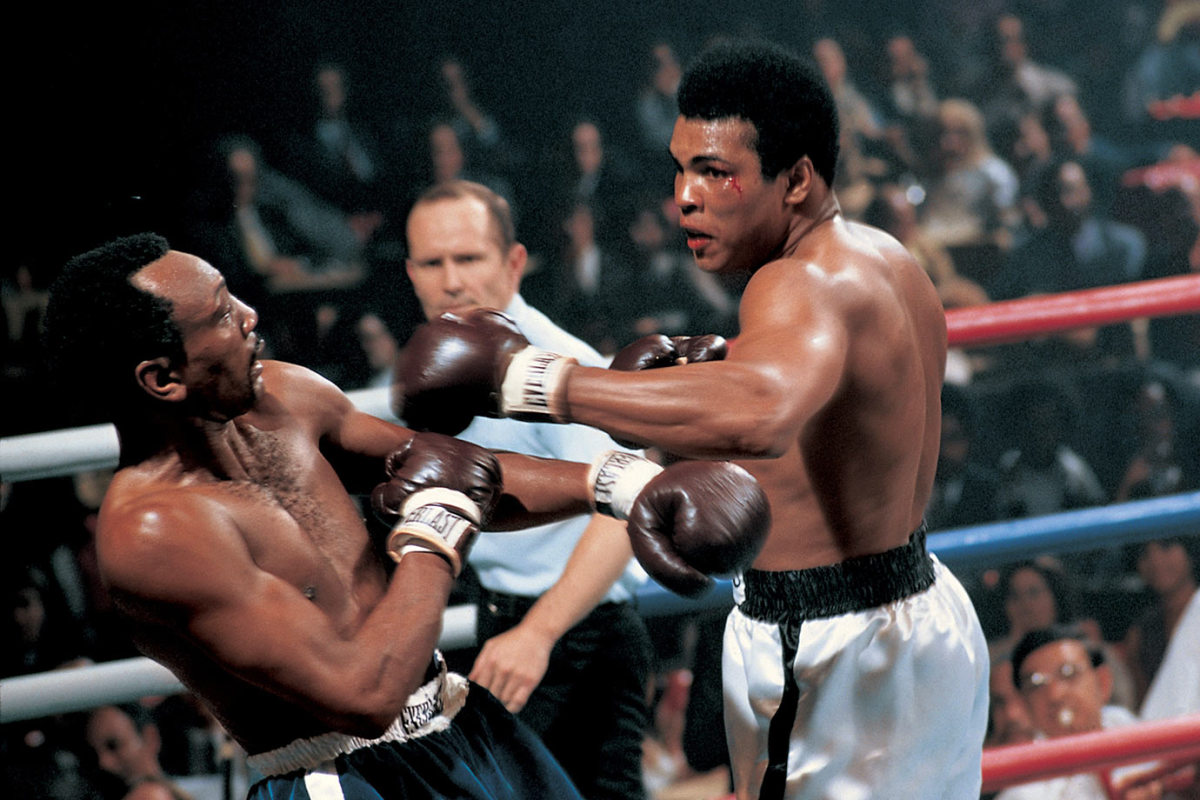

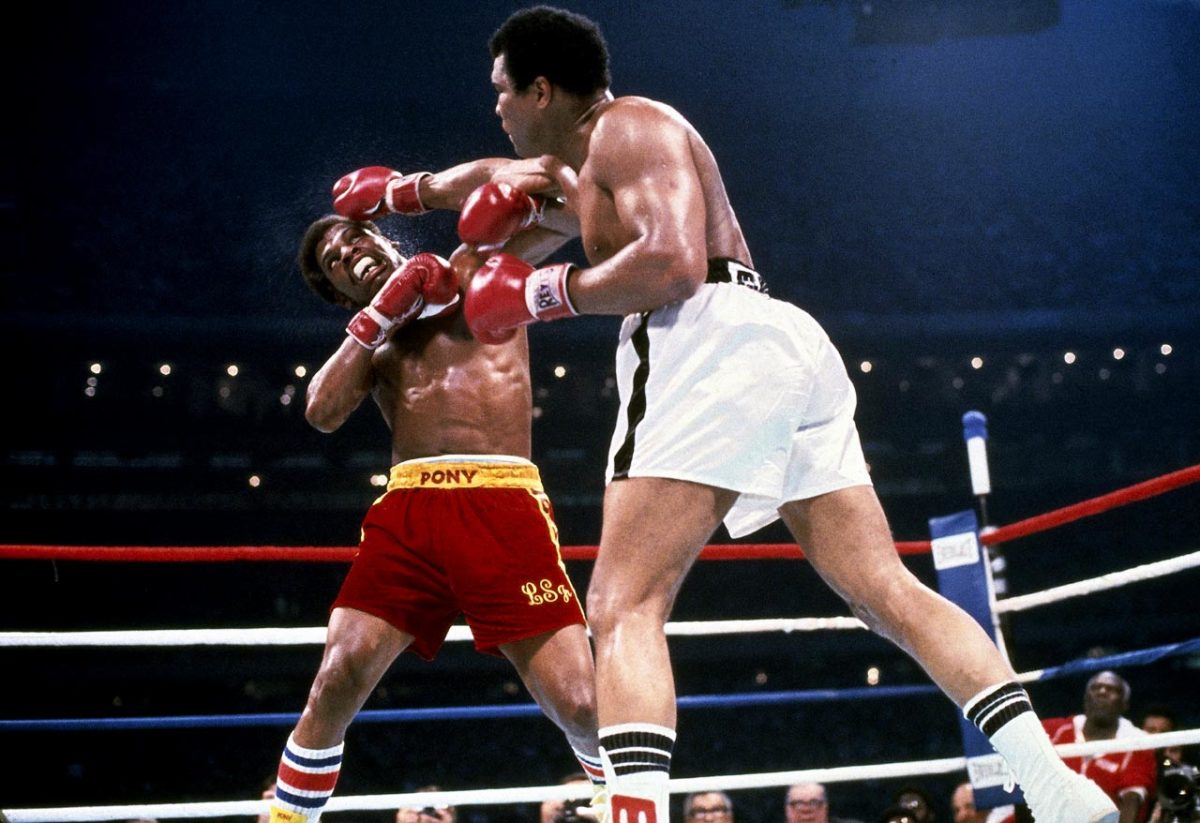

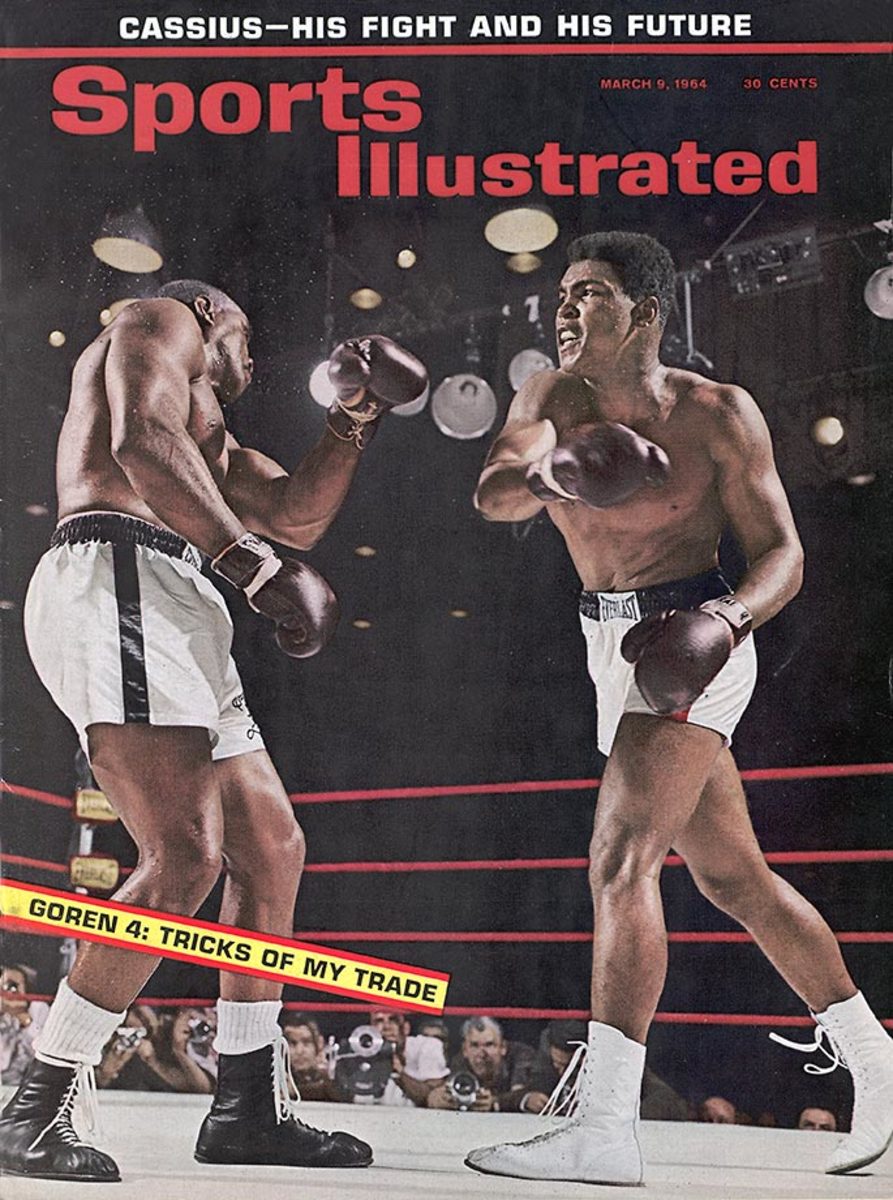

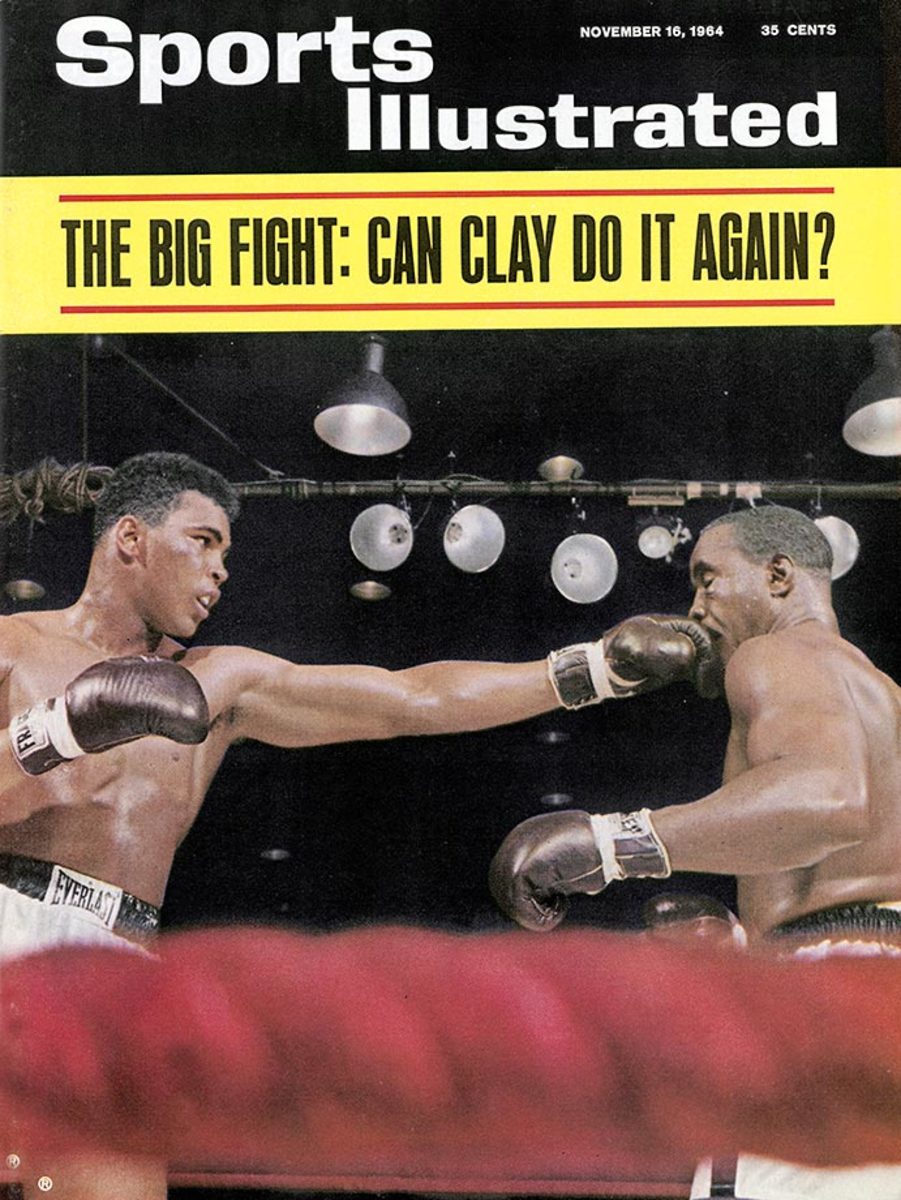

At 22-years-old, Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) battered the heavily favored Sonny Liston in a bout that shook the boxing world. The fight ignited the career of one of sports' most charismatic and controversial figures, whose bouts often became social and political events rather than simply sports contests. At the peak of his fame, Muhammad Ali was the best known athlete in the world. Liston, one of the most feared heavyweight champions in history, was a 1-8 favorite over the young challenger known as the Louisville Lip. But Clay, here stinging the champ with a right, used his dazzling speed and constant movement to dominate the action and pile up points.

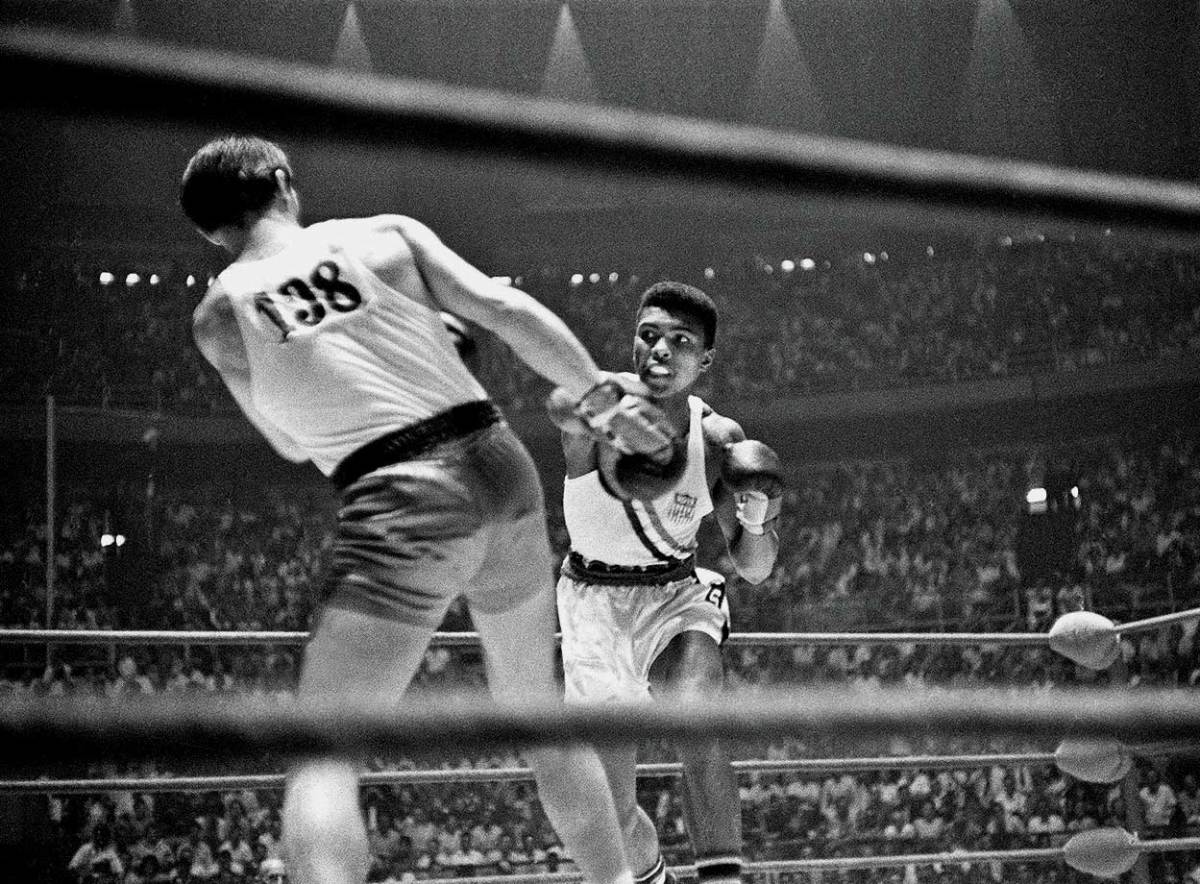

Cassius Clay punches Zbigniew Pietrzykowski of Poland during their gold medal bout at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Clay defeated Pietrzykowski 5-0 for the light heavyweight gold medal.

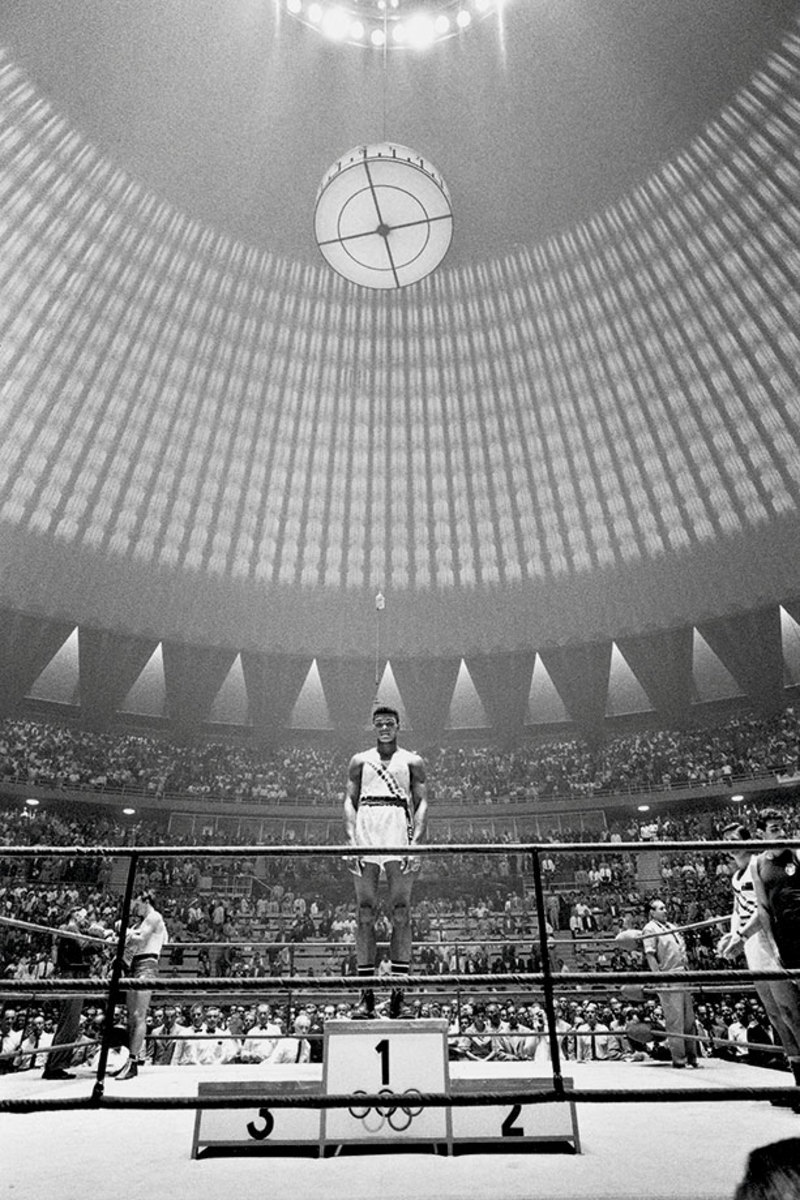

For the 18-year-old from Louisville, here atop the medal stand after his Olympic victory, all roads led from Rome. Clay finished his amateur career with a record of 100-5 and made his professional debut two months after the Games.

Undefeated in his first 17 pro fights, Clay mugged for the camera before the start of his 1963 bout against Doug Jones in Madison Square Garden.

Trainer Angelo Dundee urged his young charge to get serious before the opening bell against Jones. Clay followed instructions and emerged from a tough fight with a unanimous decision victory. Three months later he would stop Henry Cooper and close out 1963 at 19-0.

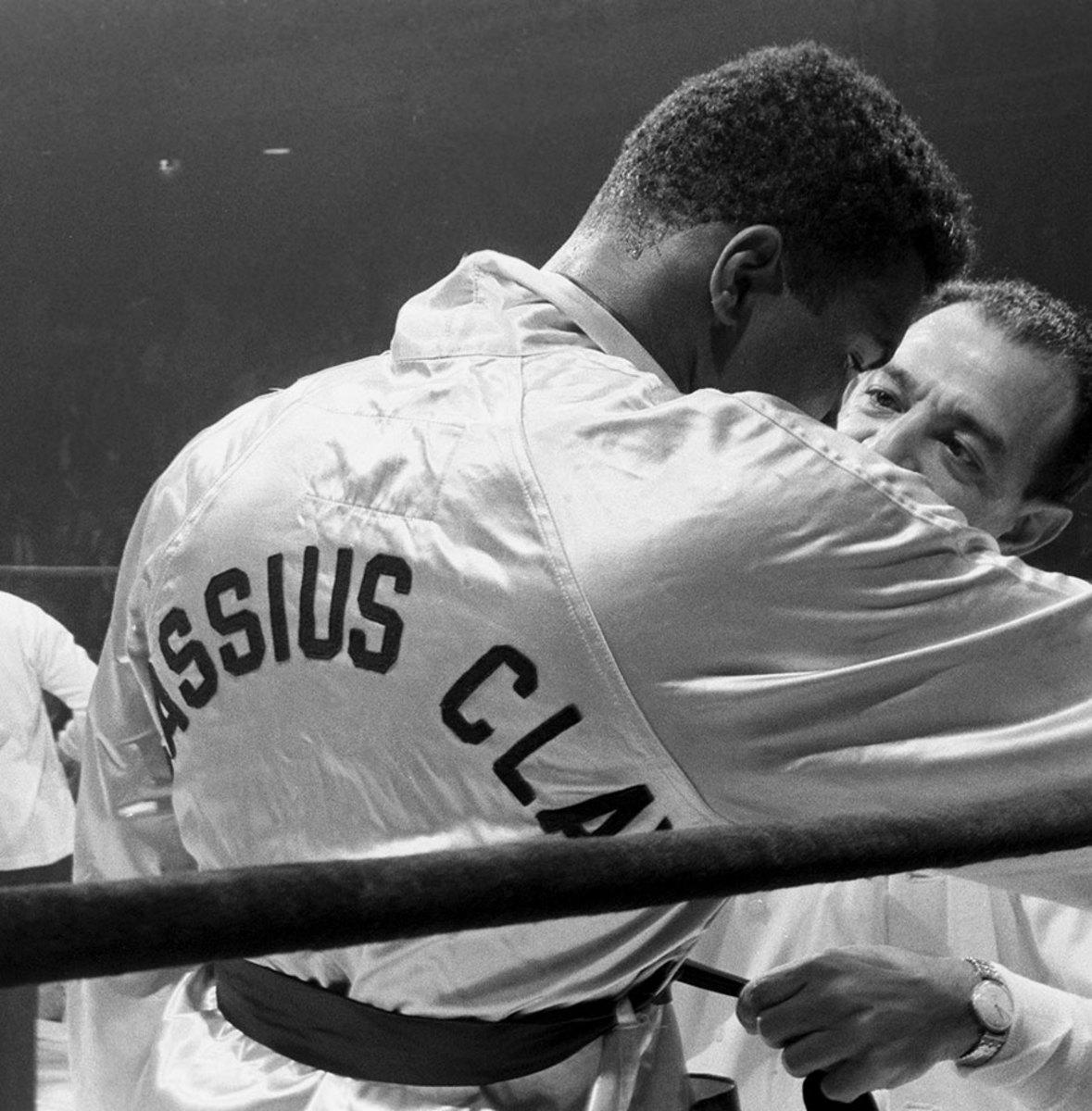

A seemingly hysterical Clay taunted Sonny Liston during the pre-fight physical for their 1964 bout. He had consistently baited the Big Bear during the lead-up to the fight, saying he was going to "use him as a bearskin rug ... after I whup him." The Miami Boxing Commission would fine Clay $2,500 for his outburst at the physical.

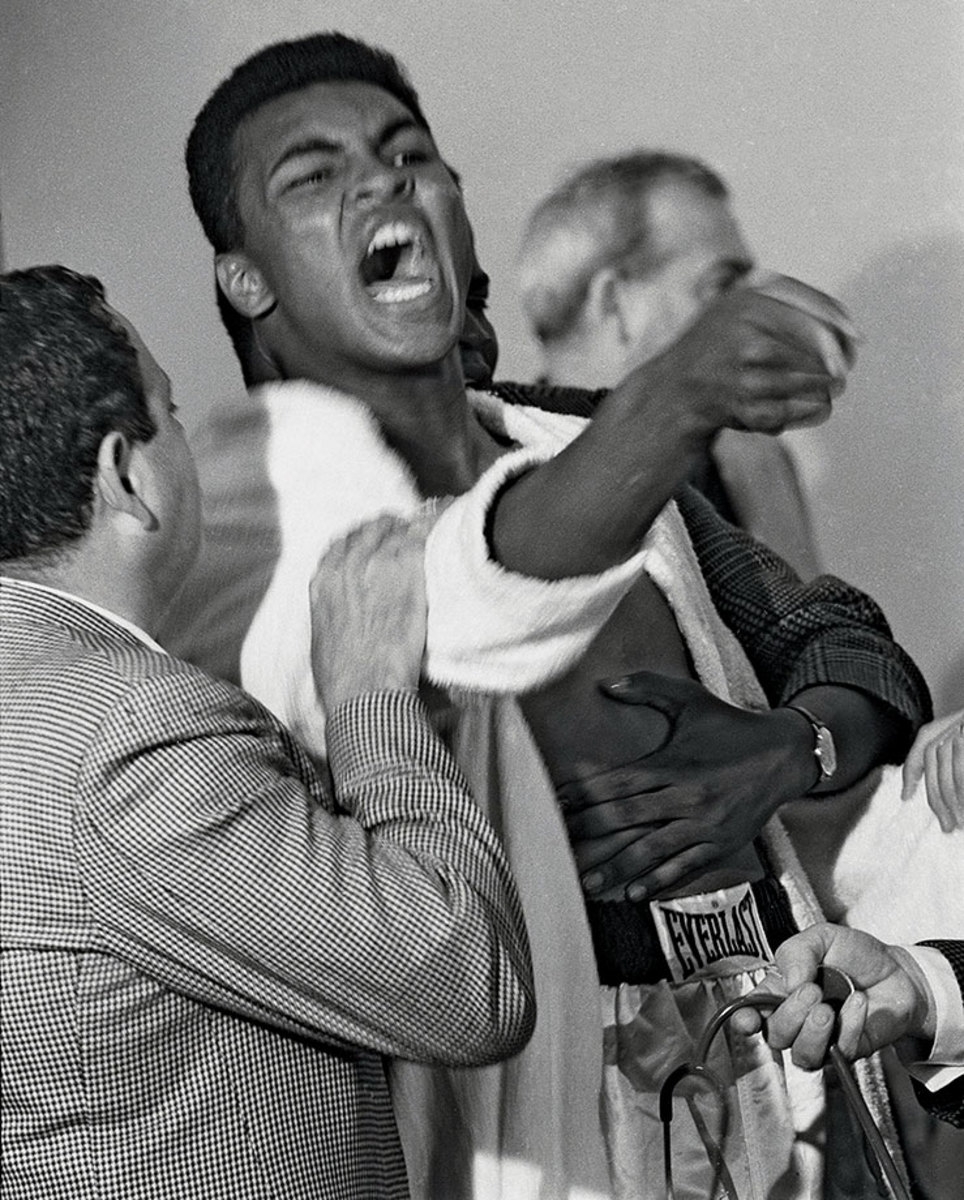

"I shook up the world!" an emotional Clay hollered to ringside reporters after his shocking defeat of Liston. And he did just that, claiming the heavyweight title at age 21 after a clearly beaten Liston, complaining of a shoulder injury, failed to answer the bell for the seventh round.

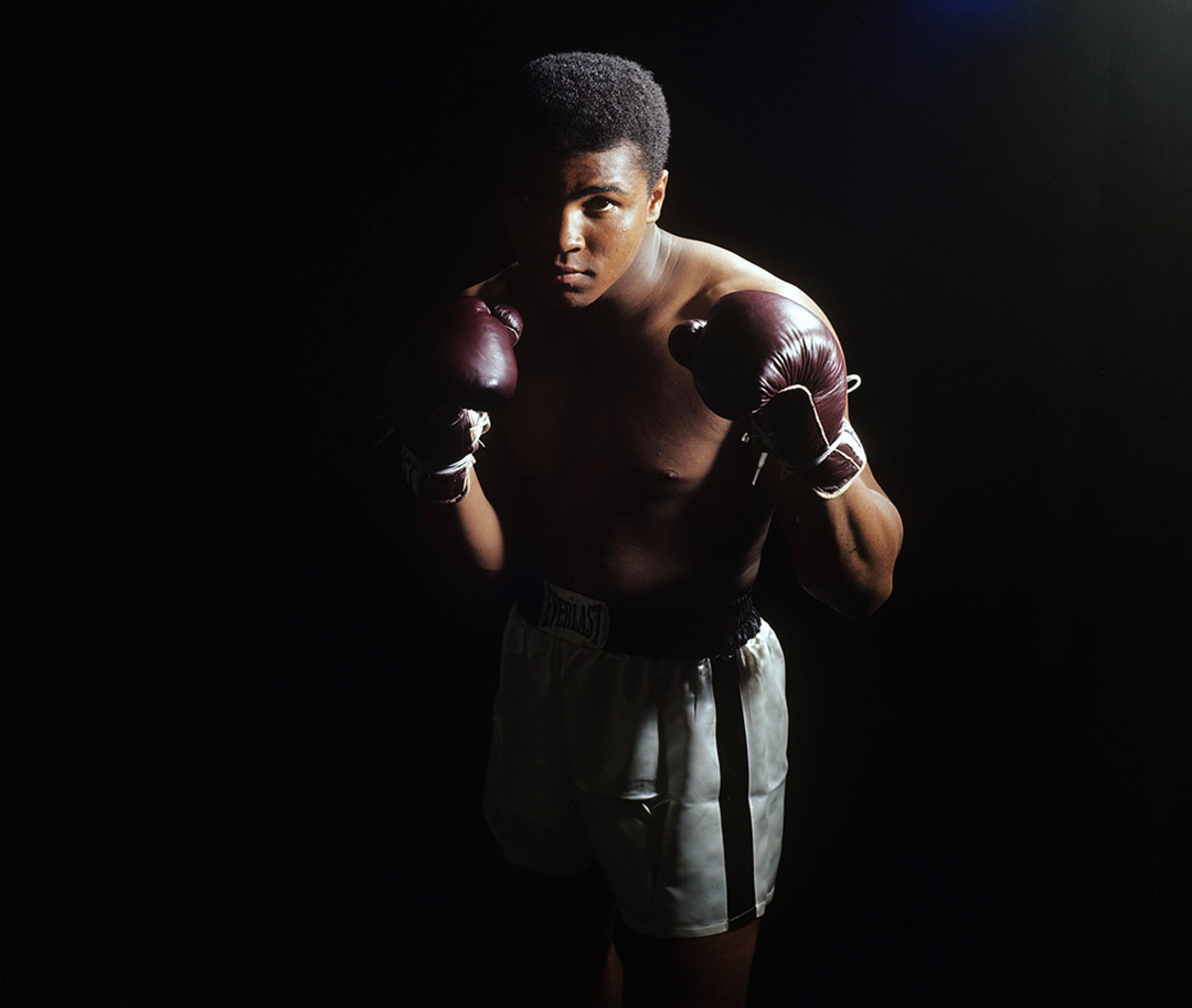

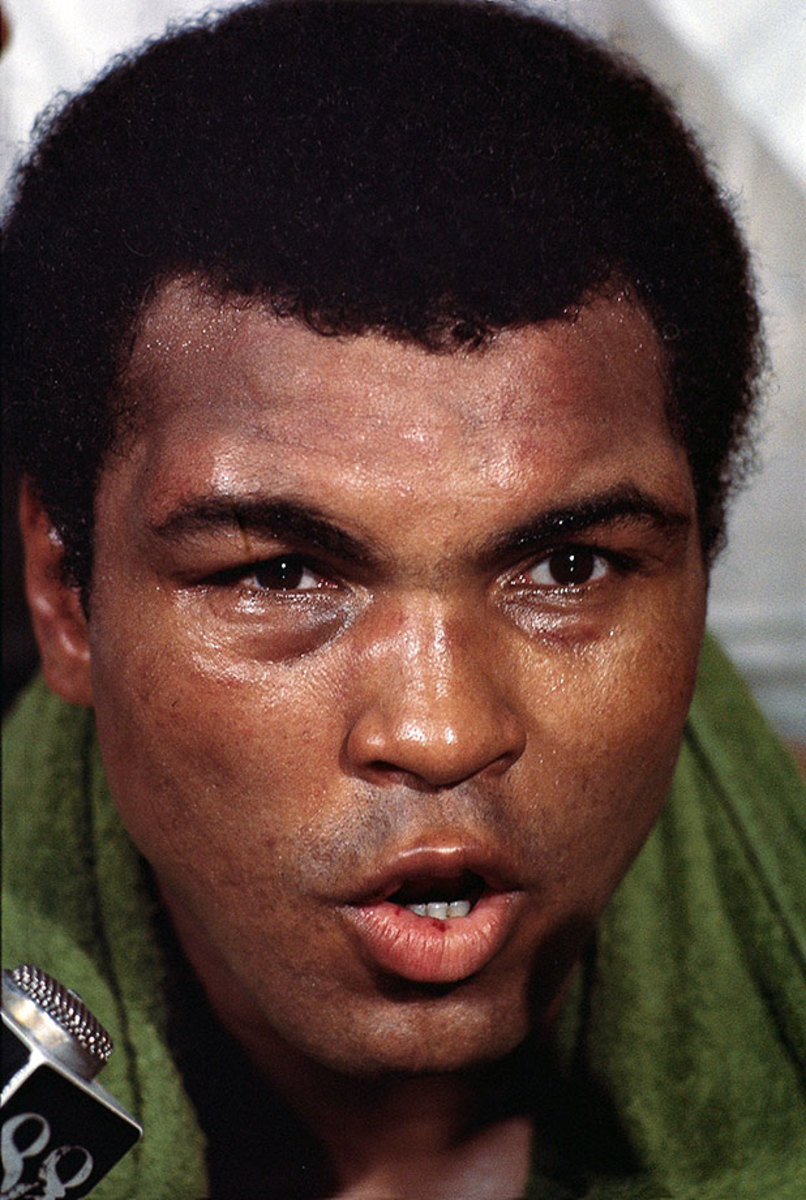

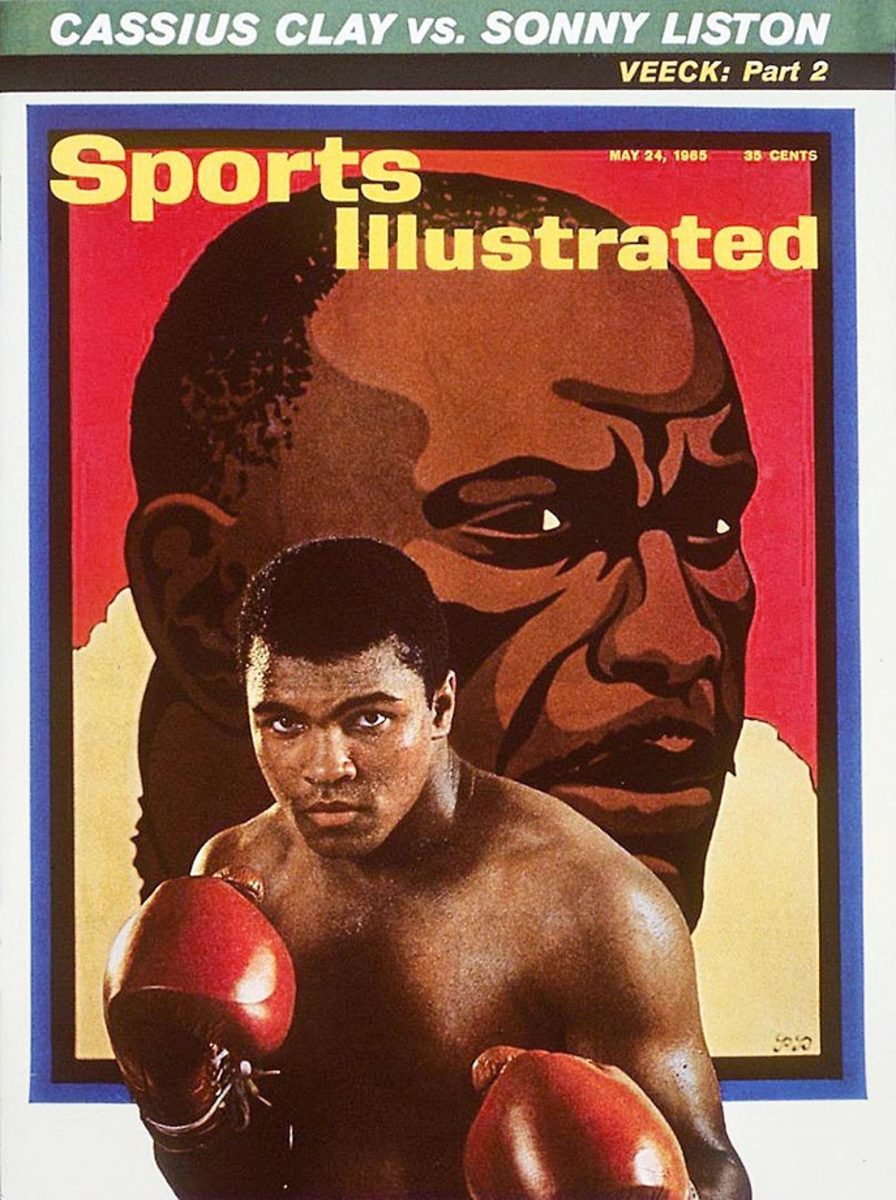

Draped in shadow, the young king — now known as Muhammad Ali — stared down the camera during a photo shoot in April 1965, one month before his rematch against Sonny Liston.

As Liston lingered on the canvas and the referee, former heavyweight champ Jersey Joe Walcott, tried to control Ali, the 2,434 spectators on hand in the Lewiston, Me., hockey arena — a record low for a heavyweight championship fight — tried to make sense of what all that had happened in less than two minutes after the opening bell.

The celebration over Liston continued. In a chaotic ending, Ali was awarded a knockout when Nat Fleischer, publisher of The Ring, informed referee Jersey Joe Walcott from ringside that Liston had been on the canvas for longer than 10 seconds after Ali knocked him down. The bout remains one of the most controversial in boxing history, with many observers insisting that Liston took a dive.

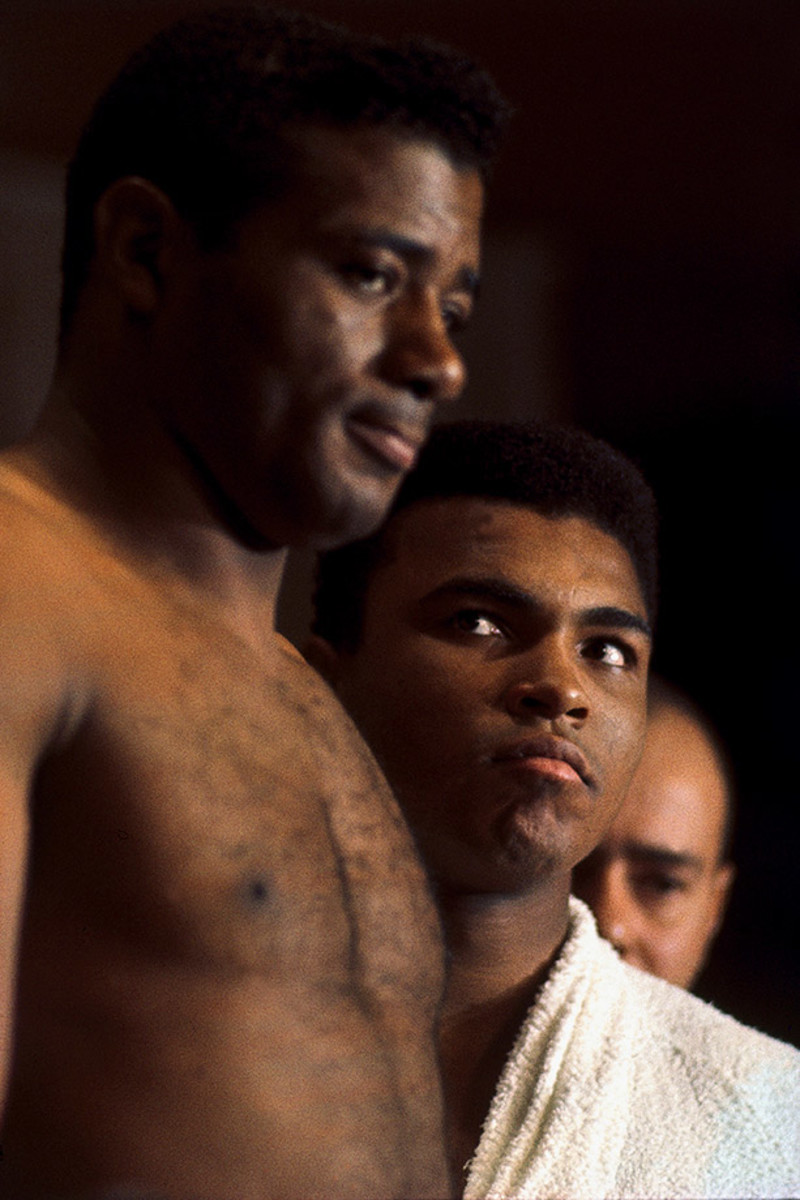

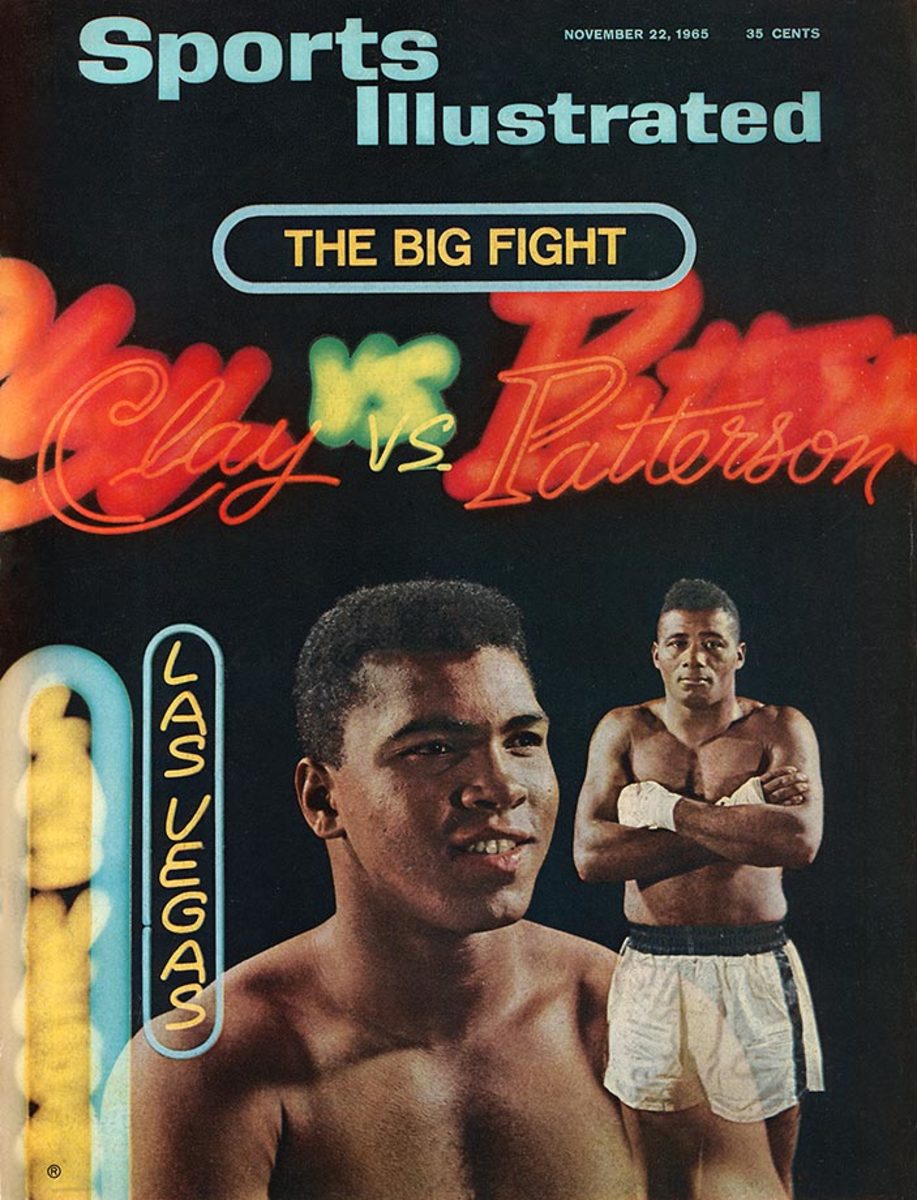

Ali's second title defense came in November 1965, against former two-time heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. During the build-up to the bout, the normally soft-spoken Patterson earned the new champ's wrath by refusing to call Ali by his Muslim name. At the weigh-in, Ali's glare made it clear that he intended Patterson to pay for the disrespect.

In cruelly efficient performance, Ali punished Patterson — who was hobbled by a painful back injury — seemingly toying with the former champ throughout the bout, hitting him at will and calling, "What's my name?" before finally winning on a 12th-round TKO.

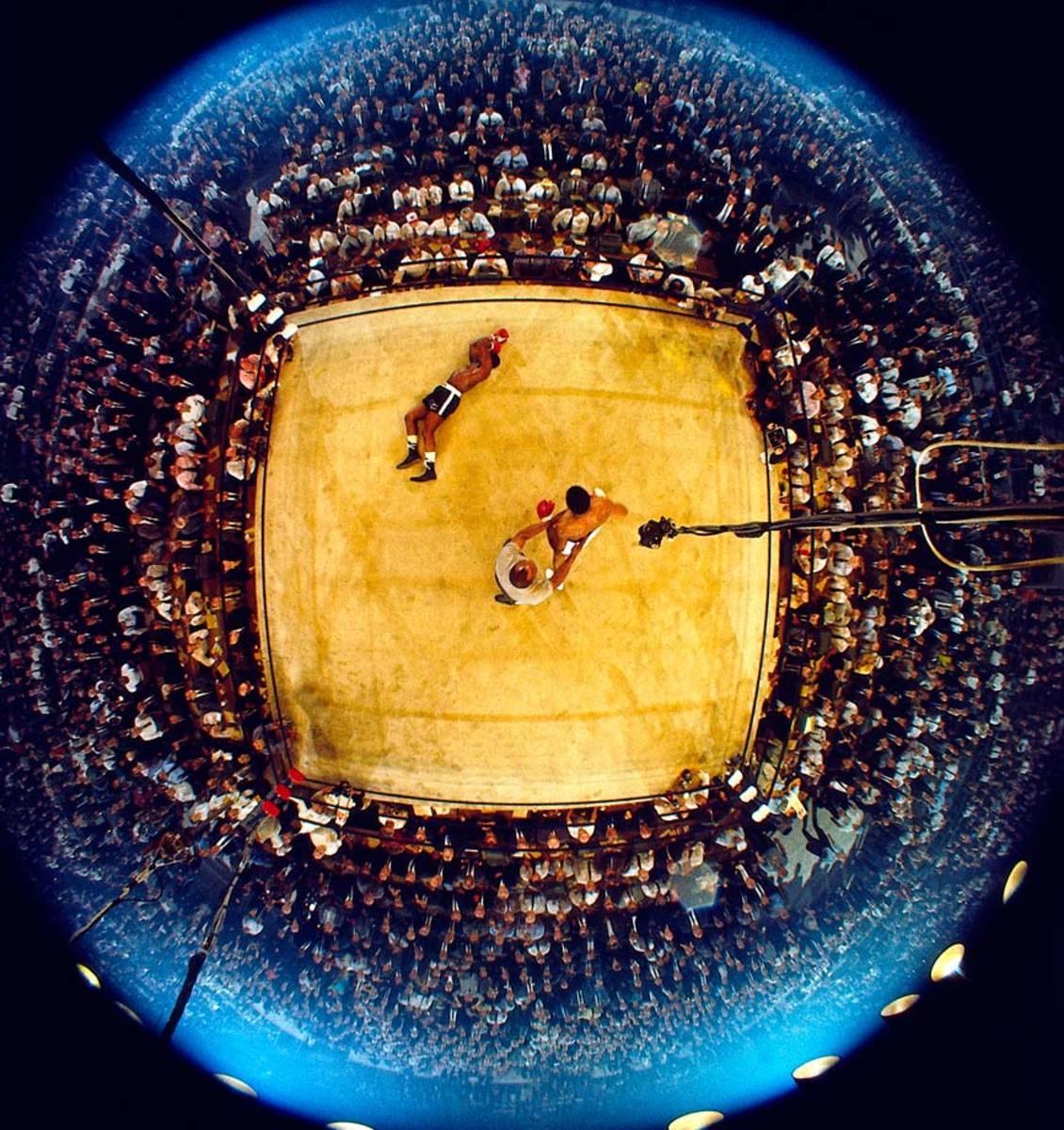

Capping off a five-fight campaign in 1966, Ali faced Cleveland Williams in the Houston Astrodome on Nov. 14. Known as the Big Cat, the heavily-muscled Williams was a power puncher who had racked up 51 knockouts in 71 fights. But he was also 33, barely recovered from a gunshot wound sustained the year before, and up against a young champion very much in his prime. Ali wasted little time in unleashing a withering attack.

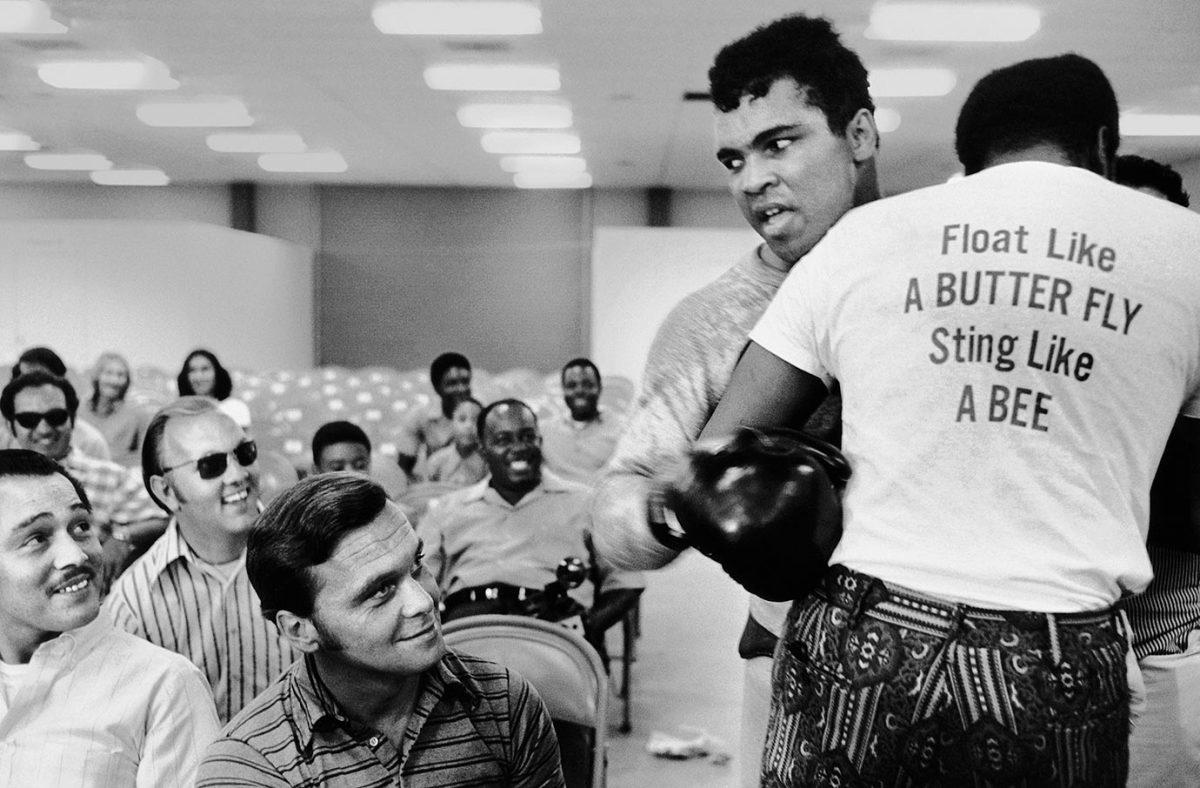

Float and sting: In a display of speed and combination punching unmatched in heavyweight history, Ali overwhelmed Williams from the start. The challenger, here down for the third time in round 2, would be saved by the bell before referee Harry Kessler could count him out, but it would only postpone the inevitable.

Ali dropped Williams again early in the third round, and Kessler waved the mismatch over at 1:08 of the third.

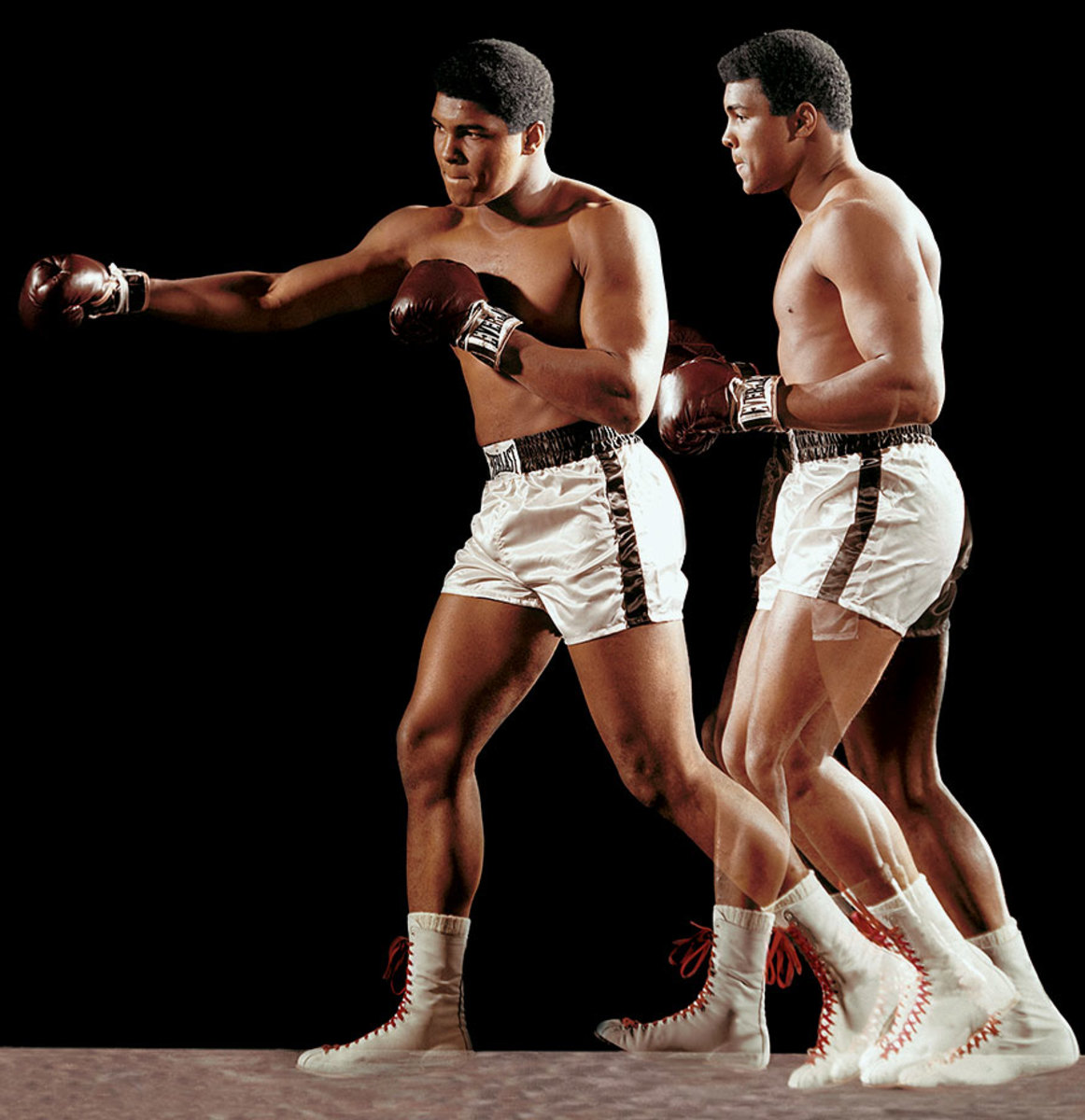

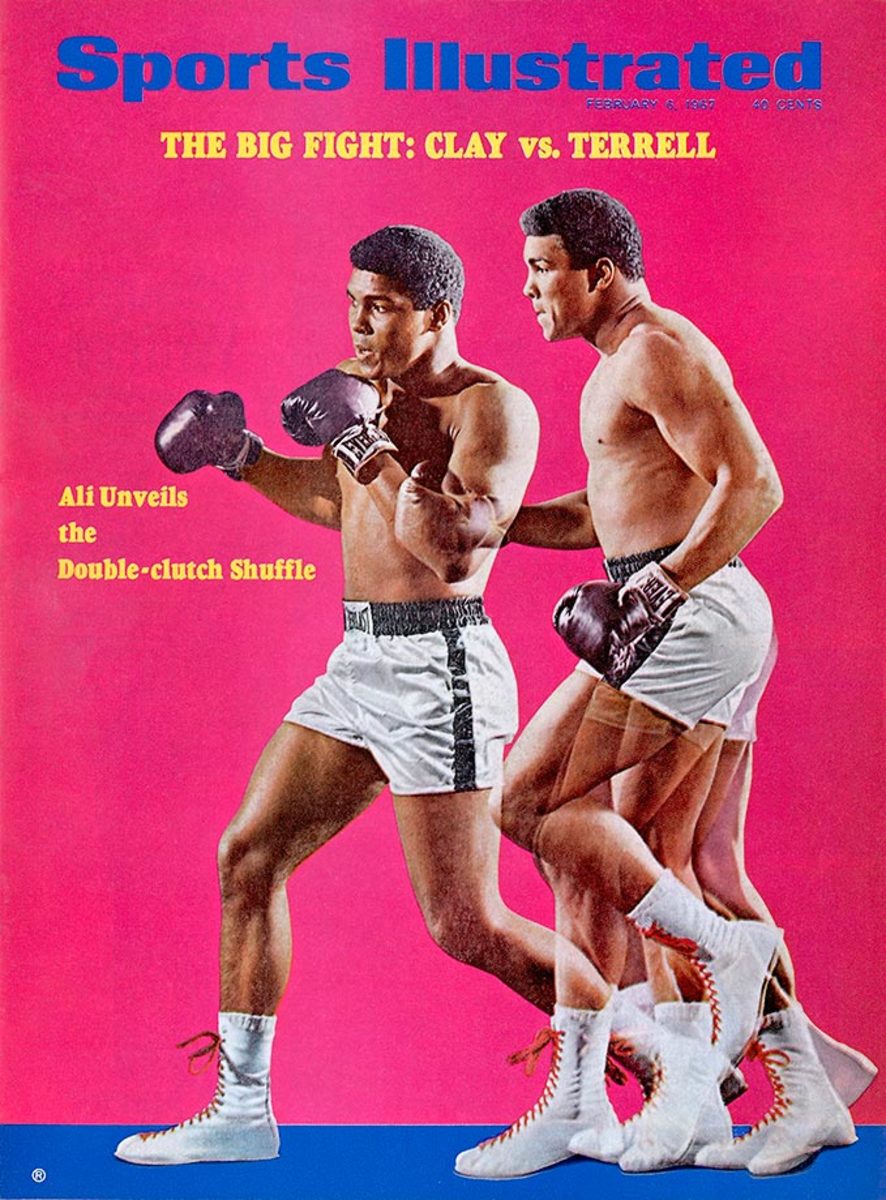

In a multiple-exposure portrait, Ali demonstrates his signature double-clutch shuffle during a photo shoot in December 1966.

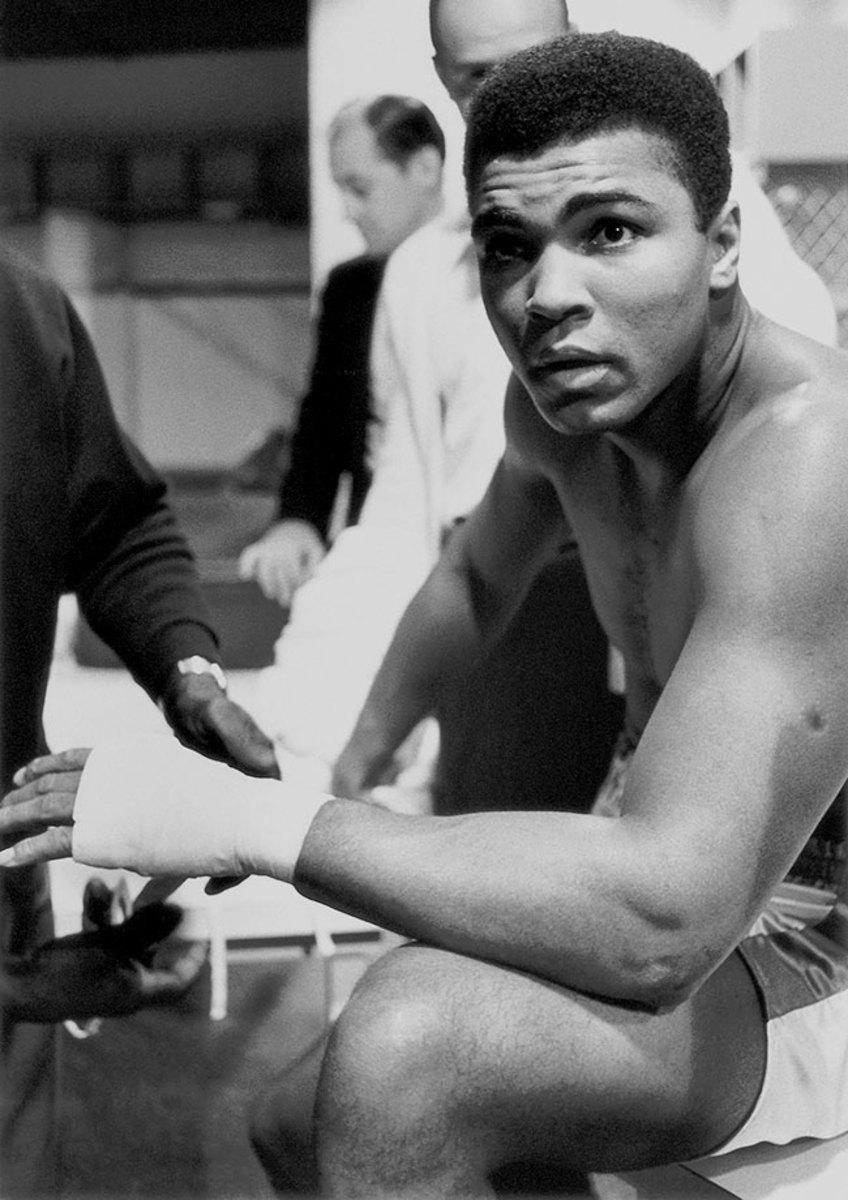

Ali sits in the locker room before his February 1967 fight against Ernie Terrell. Like Patterson before him, Terrell refused to call the champion by his Muslim name. Also like Patterson, he paid a stiff price, as Ali punished Terrell for 15 ugly rounds before winning by unanimous decision.

Outside the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in Houston in April 1967, Ali spoke to the press about his refusal to be inducted into military service. Among those on hand was ABC's Howard Cosell, who would be a staunch supporter of the fighter's stance. The decision cost Ali his boxing license and his heavyweight title, and he was sentenced to five years in prison but remained free pending an appeal.

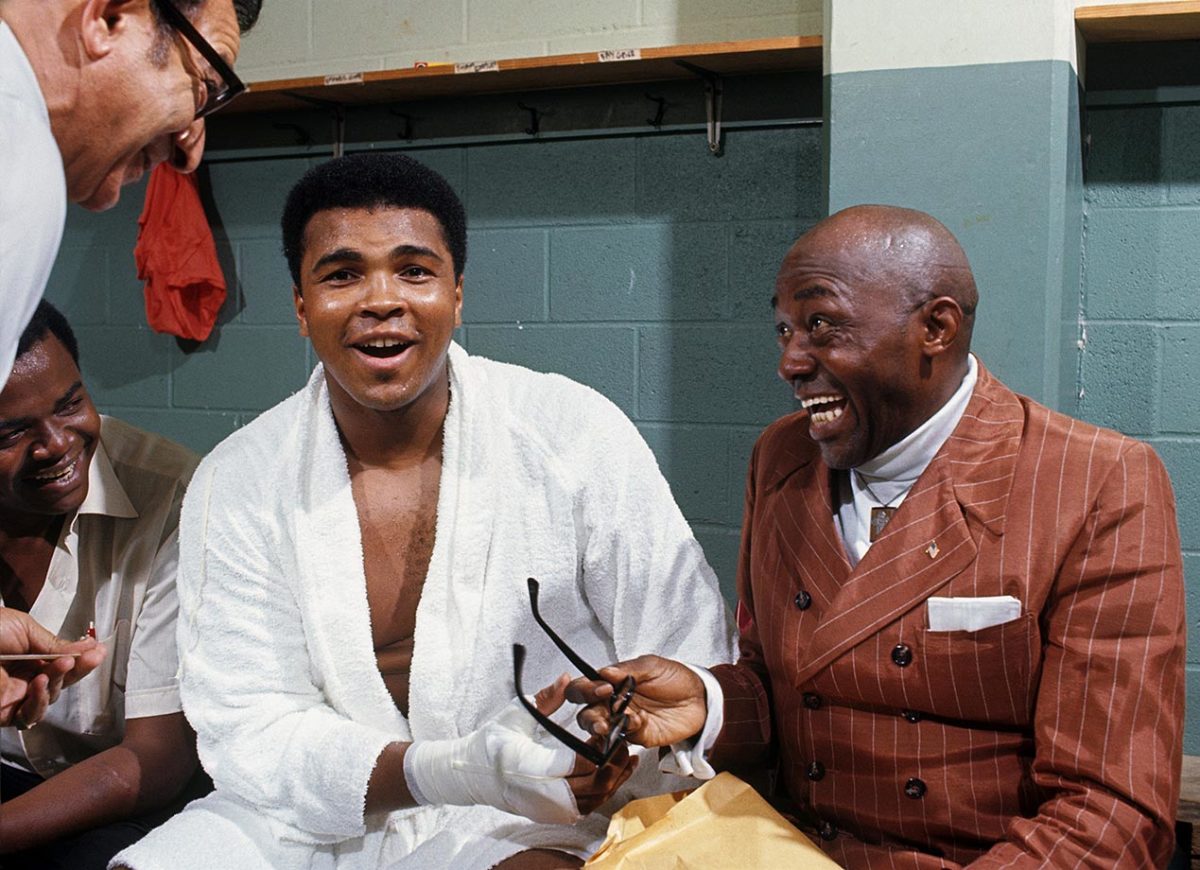

In professional exile for three and a half years because of his draft case, Ali sought to return to boxing in 1970. He began with a night of exhibition bouts at Morehouse College in Atlanta, where before going into the ring, he shared a locker room laugh with actor and comedian Lincoln Perry (right), better known by his stage name of Stepin Fetchit. The friendship between the two black icons would later be examined in an acclaimed play by Will Power, Fetch Clay, Make Man.

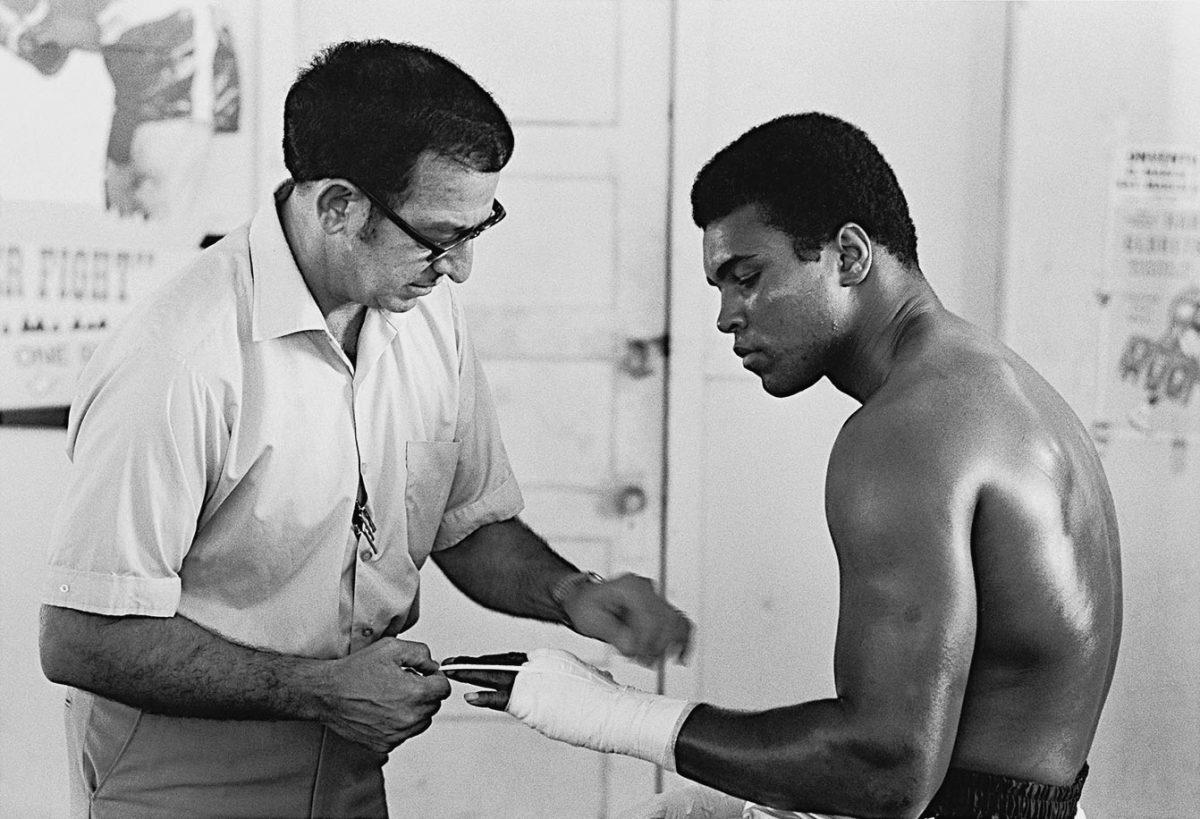

After the Atlanta Athletic Commission at last granted Ali a license, the deposed champion went back into serious training. He was, as ever, in the capable hands of trainer Angelo Dundee, here wrapping boxing's most famous fists at the 5th Street Gym in Miami in October 1970.

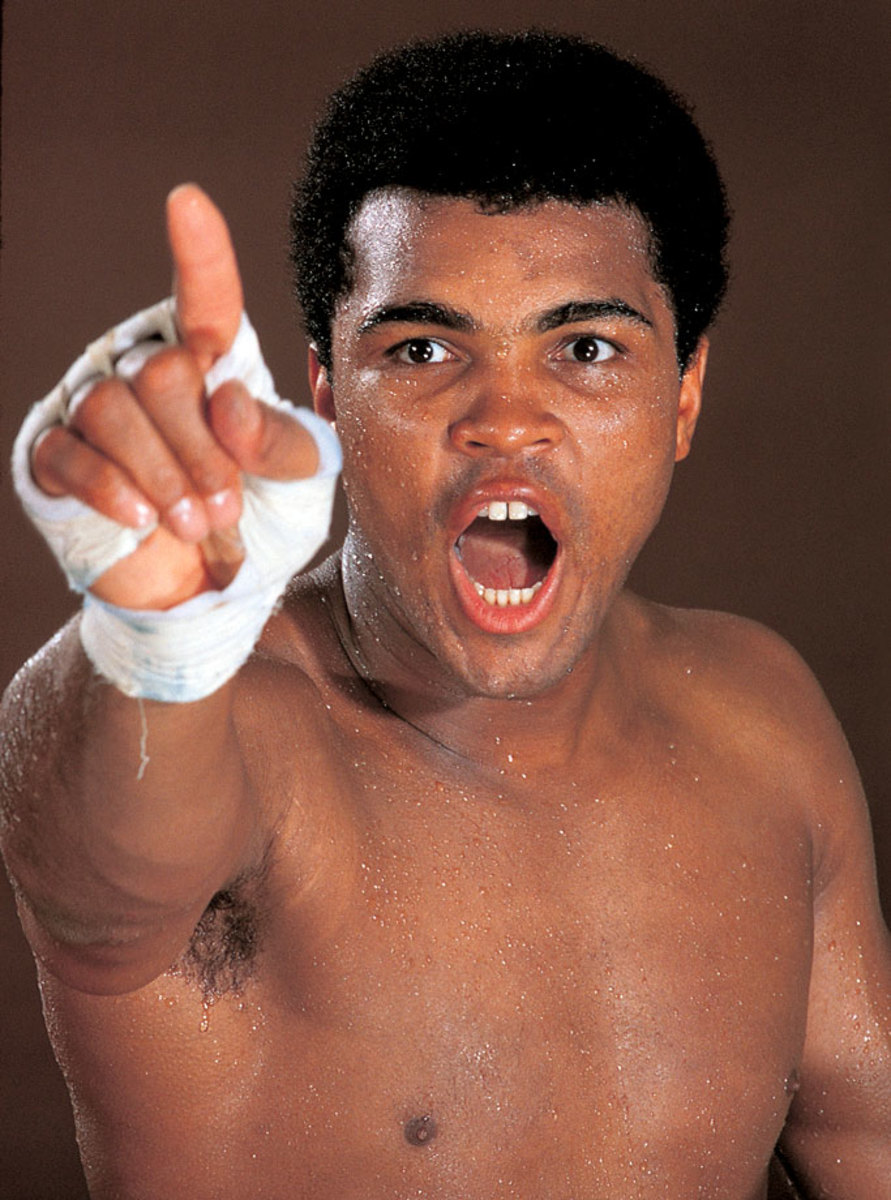

With his return to the ring scheduled for Oct. 26, 1970 in Atlanta, against dangerous contender Jerry Quarry, Ali made it clear to all who would listen that he was on a mission to reclaim the title that had been stripped of him.

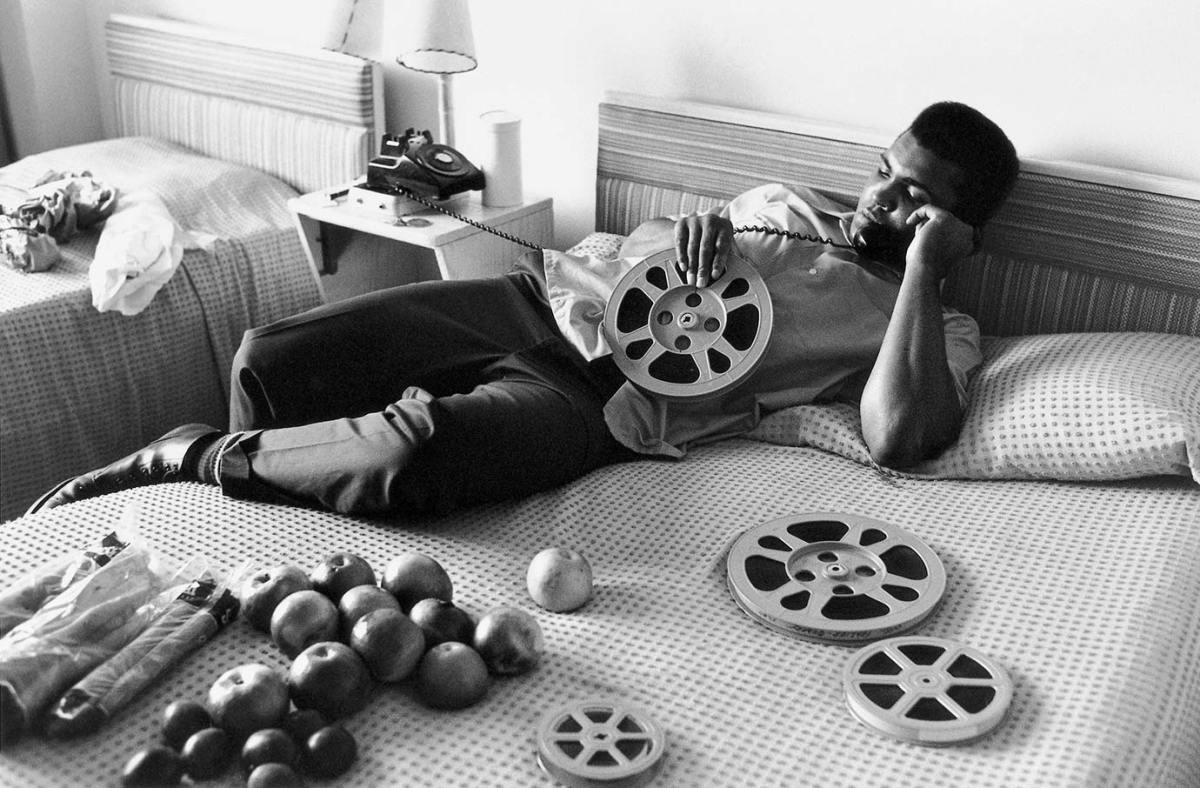

Reel to spiel: For the ever-loquacious Ali, even a rare moment of down time — like this afternoon in 1970 in a Miami hotel room — was a chance to do some talking.

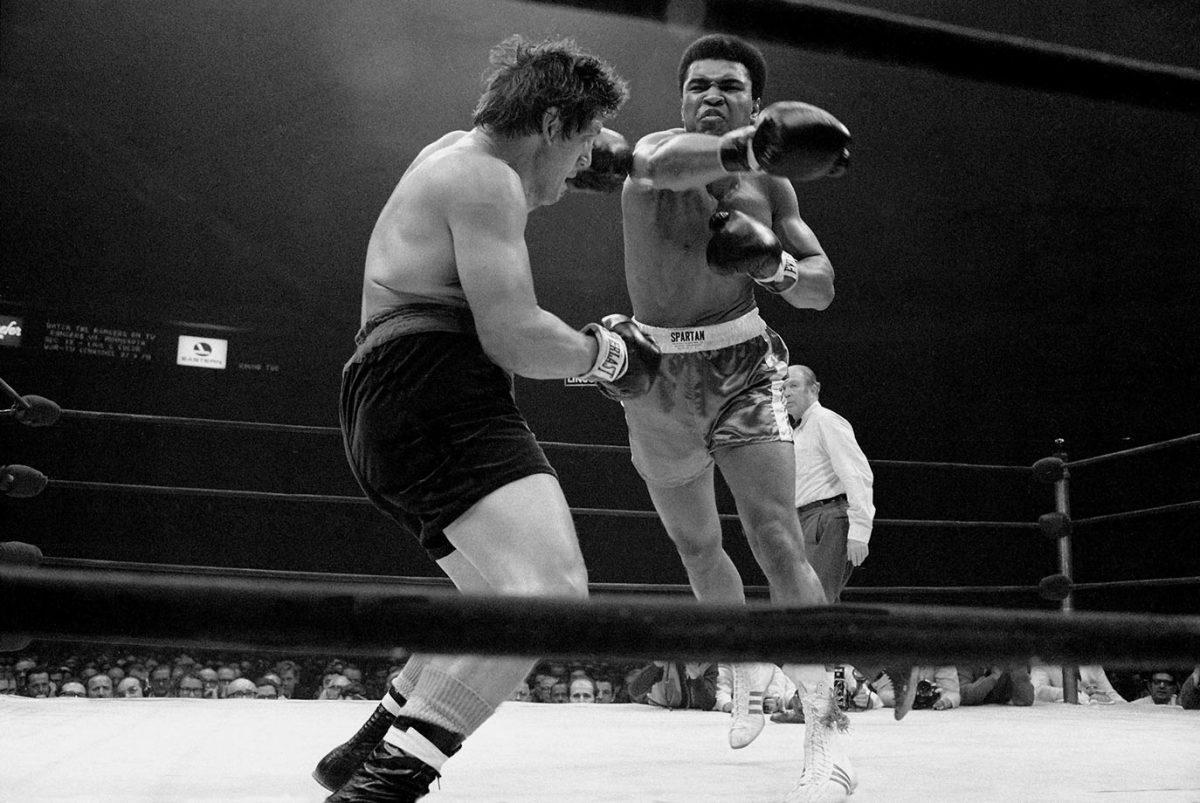

Despite Ali's long layoff, his comeback campaign would include no easy tune-up bouts. He stopped Quarry in three rounds on Oct. 26, 1970, then, just six weeks later — an unthinkably short interlude by today's standards — took on Argentine contender Oscar Bonavena in Madison Square Garden. Here, Ali fires a right at the rugged and awkward Bonavena, who took the fight to the former champion all night.

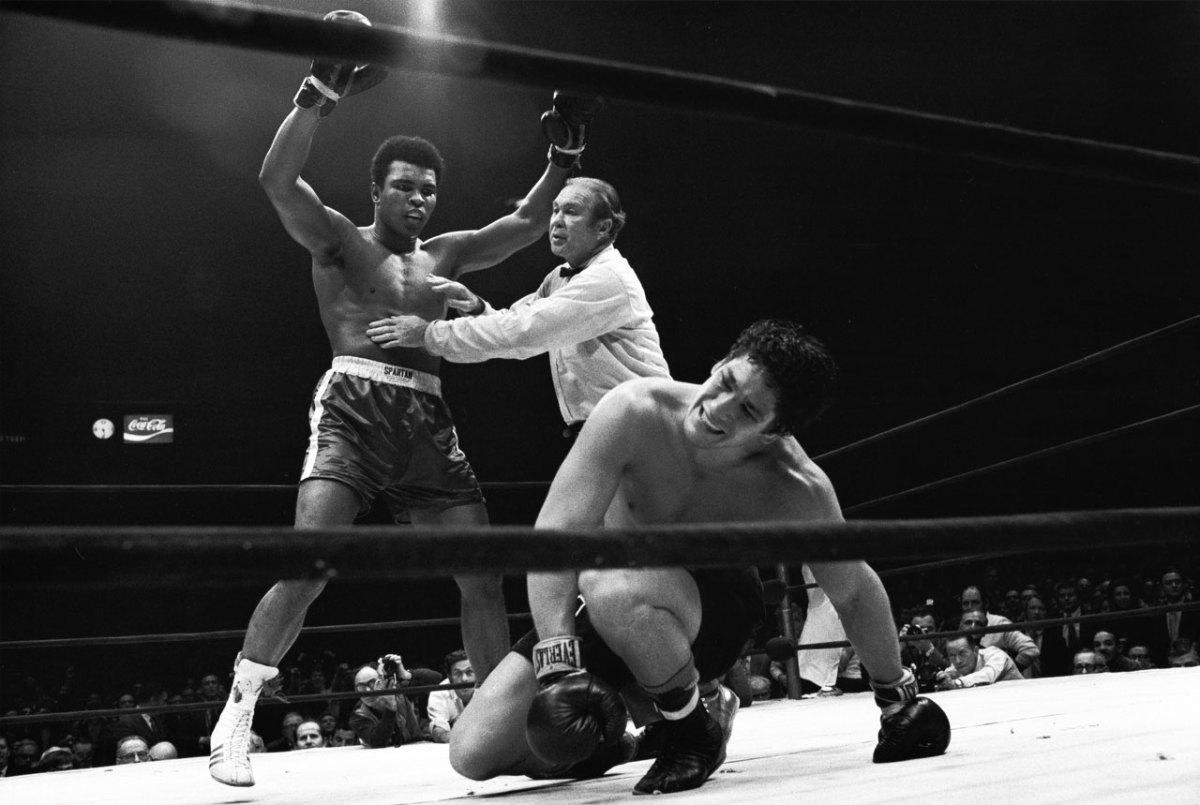

After a long, often sloppy bout, Ali — here being held back by referee Mark Conn — produced one of the most dramatic finishes of his career, dropping Bonavena three times in the 15th and final round to automatically end the fight. The win cleared the way for a showdown with Joe Frazier, the man who had taken the heavyweight title in Ali's absence.

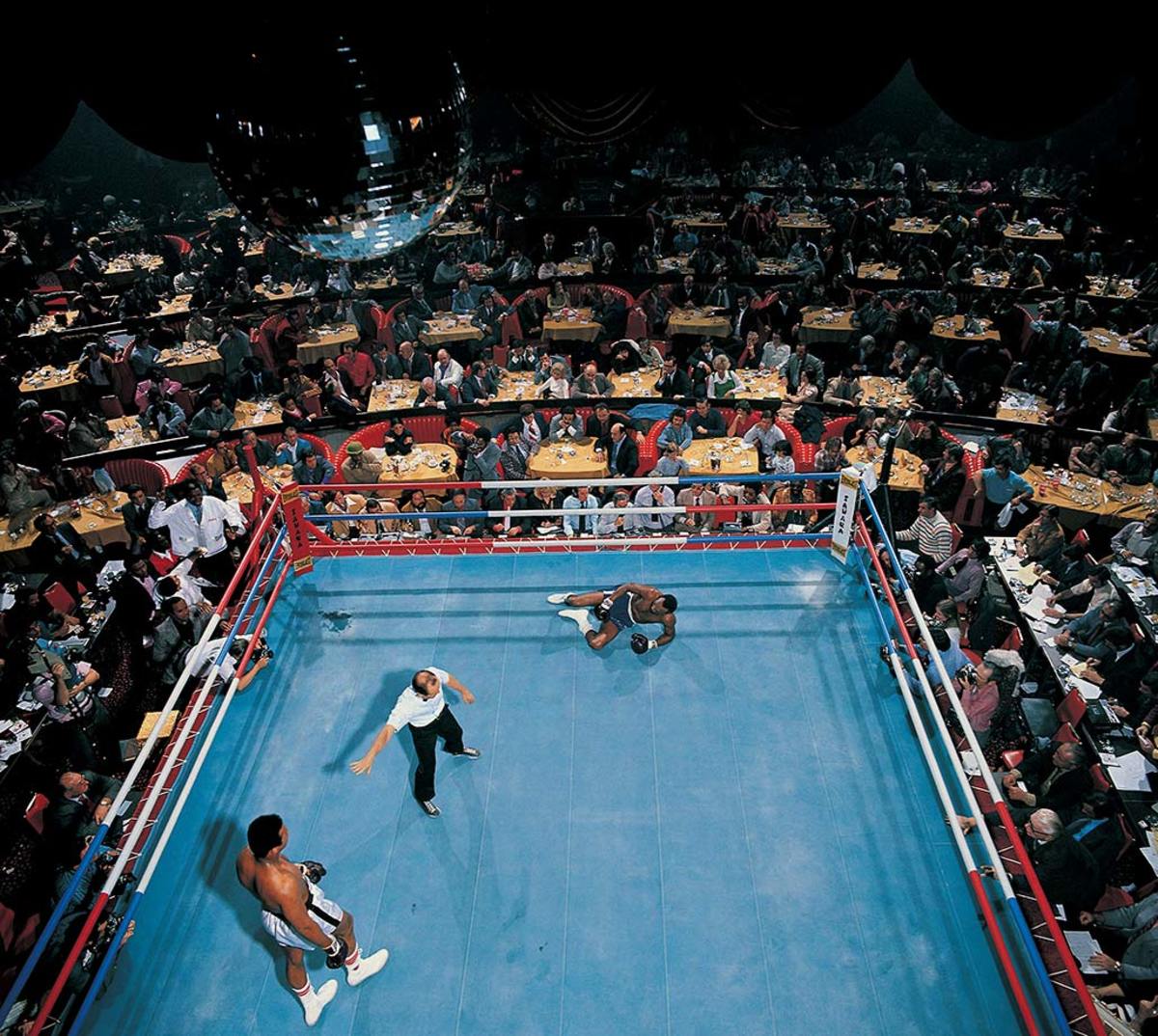

On the night of March 8, 1971, the eyes of the world were on a square patch of white canvas in the center of Madison Square Garden. There, Ali and Joe Frazier met in what was billed at the time simply as The Fight, but has come to be known, justifiably, as the Fight of the Century. For 15 rounds the two undefeated heavyweights battled at a furious pace, with each man sustaining tremendous punishment. In the end Frazier prevailed, dropping Ali in the final round with a tremendous left hook to seal a unanimous decision and hand The Greatest his first loss in 32 professional fights.

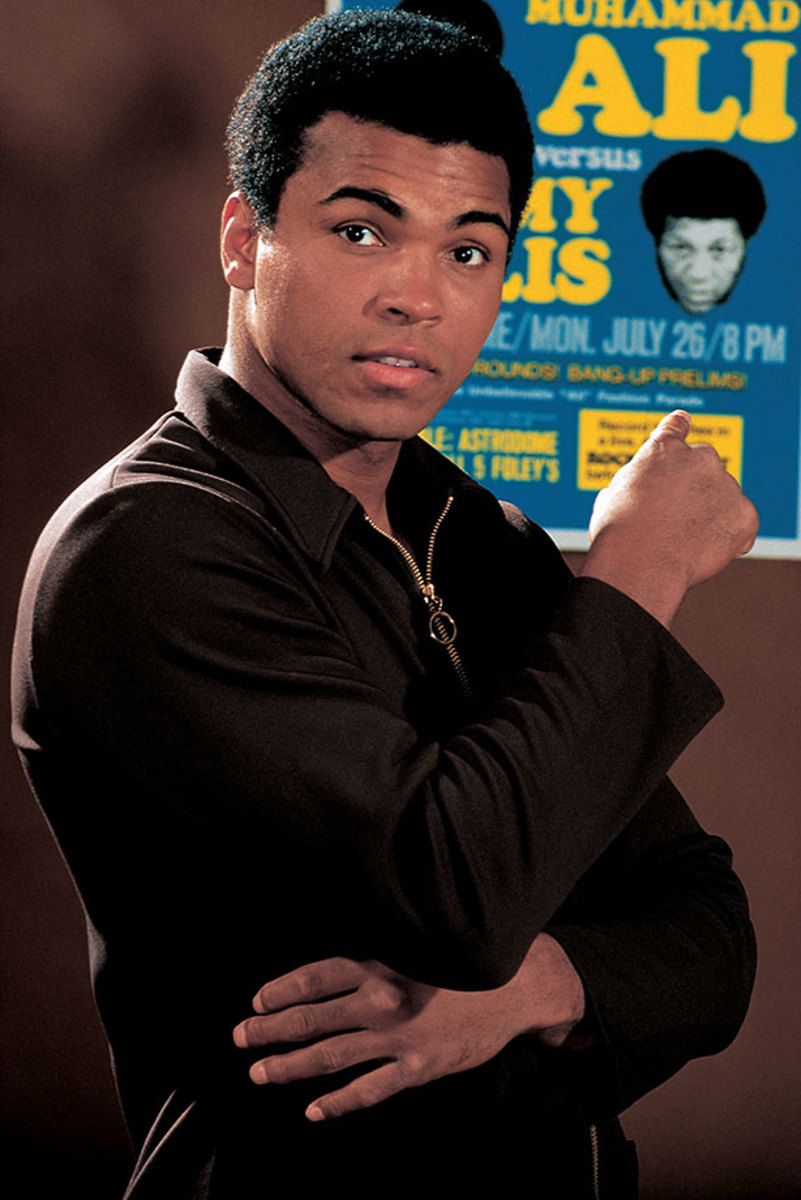

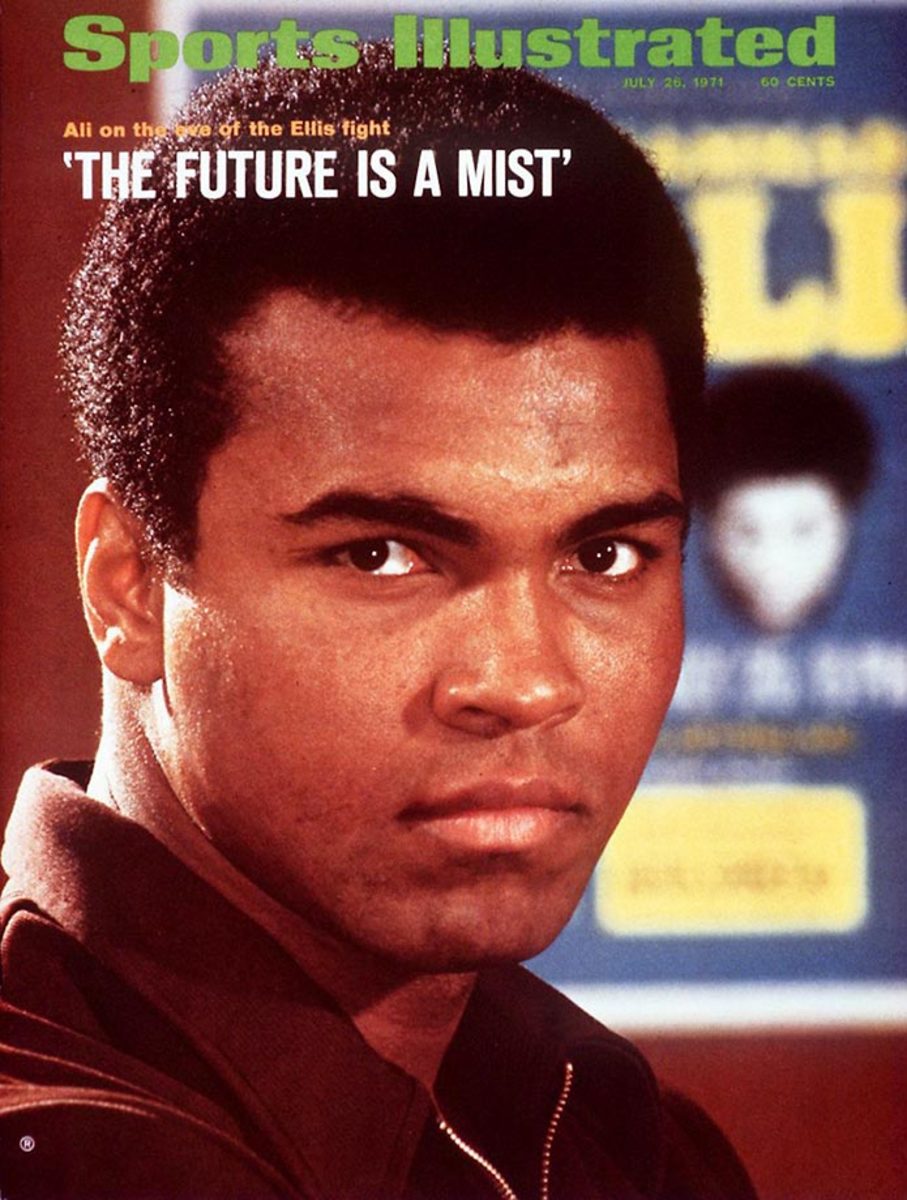

Ali poses with the fight poster for his upcoming fight against Jimmy Ellis during a photo shoot in July 1971. Ellis was an old friend of Ali's — both were trained by Angelo Dundee — and knew his fighting style well from many rounds of sparring.

For those sportswriters lucky enough to cover Ali on a regular basis, each day brought surprises and, more often than not, plenty of laughs. of Trainer Drew Bundini Brown helps Ali train for his fight against Ellis. Ali won the bout by technical knockout in the 12th round to claim the vacant NABF heavyweight title.

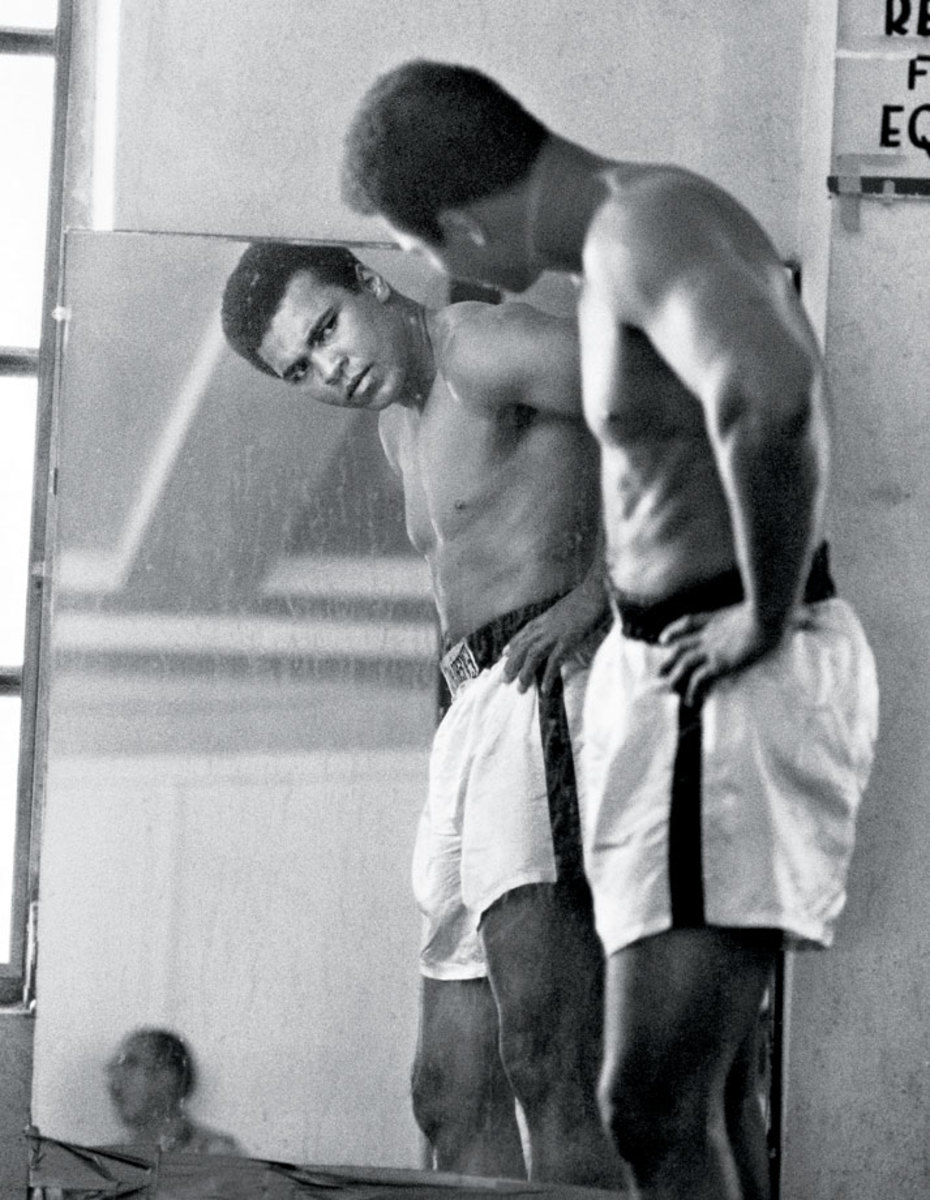

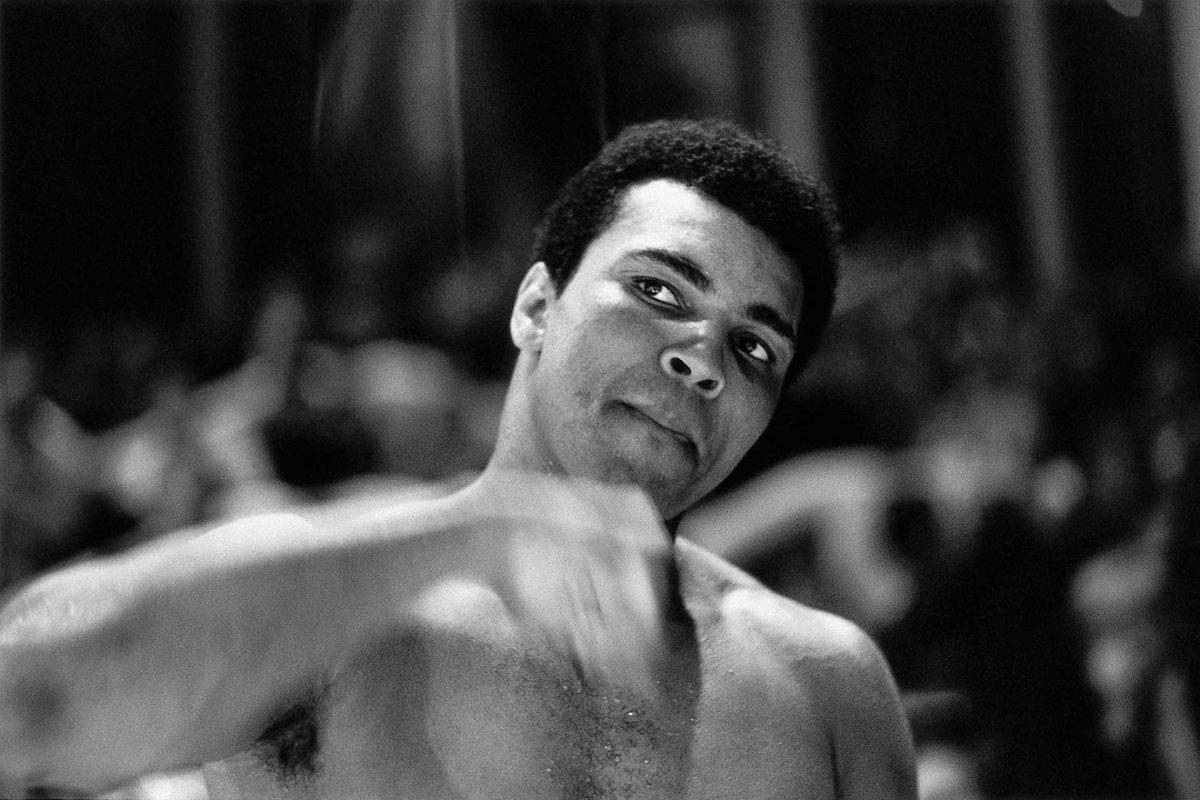

The man in the mirror stares back as Ali examines himself while training for a fight in 1972. He won all six of his fights that year.

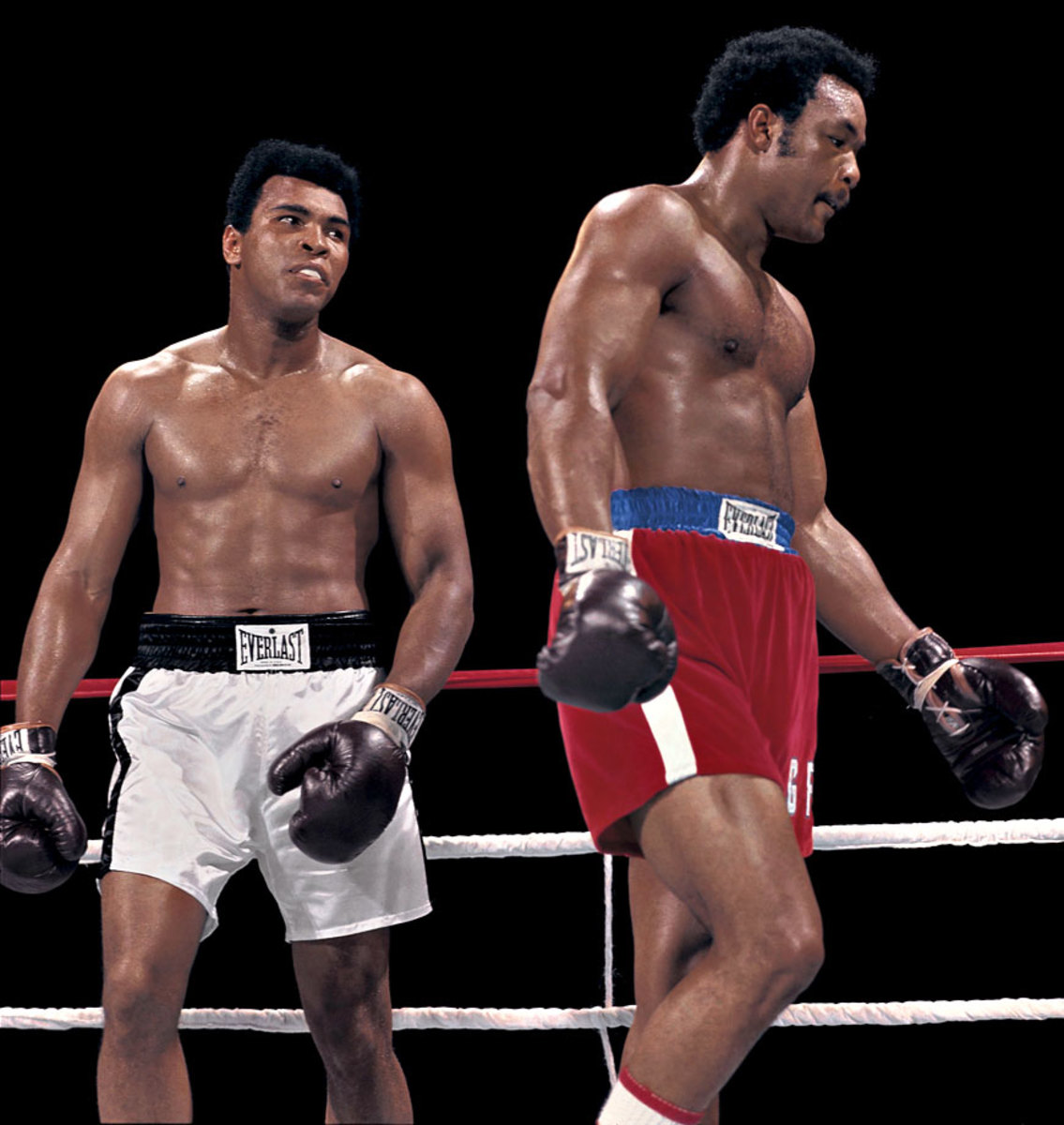

The Louisville Lip stands next to George Foreman before Ali's fight versus Jerry Quarry in June 1972. Ali won by technical knockout in the seventh round. Foreman at the time was 36-0. Ali would not get his shot against Foreman for more than two years.

Ali throws a left hook at Bob Foster in their 1972 fight at Stateline, Nev. Although Ali knocked Foster out, Foster did leave his mark: a cut above Ali's left eye, his first as a professional.

Foster lies on the canvas after getting knocked down by Ali. Ali knocked Foster down four times in the fifth round and twice more in the seventh round before he was finally counted out after Ali knocked him down again in the eighth round.

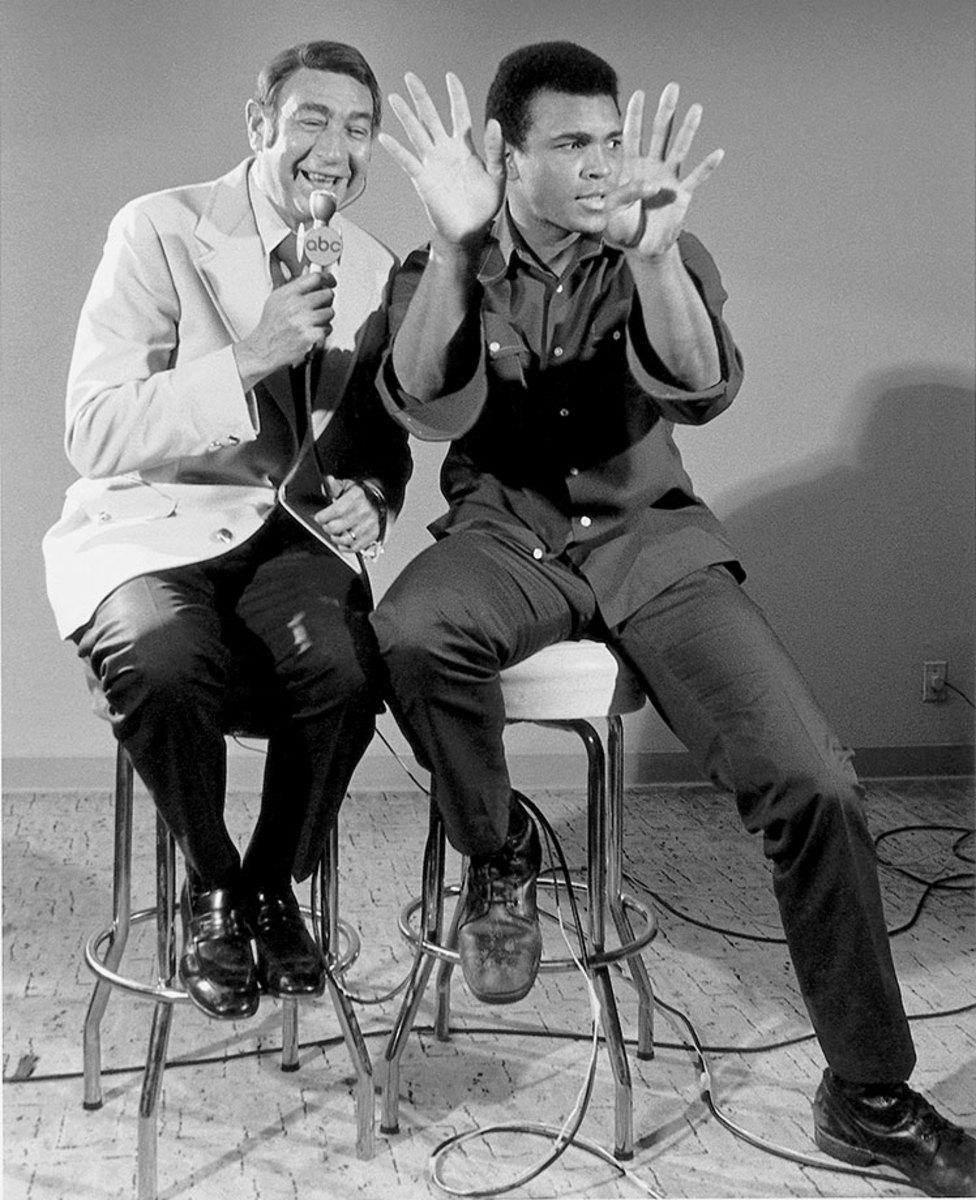

Ali sits with sportscaster Howard Cosell before his fight with Joe Bugner in February 1973. Although unable to knock Bugner out, Ali won comfortably by unanimous decision.

Ali hits a speed bag while warming up for his bout with Bugner in Las Vegas. Ali prepared ferociously for the fight, training 67 rounds the week leading up to the fight, including six rounds the day before the fight.

In a lighter pre-fight moment, Ali poses for a portrait wearing a hat in his dressing room before the match with Bugner.

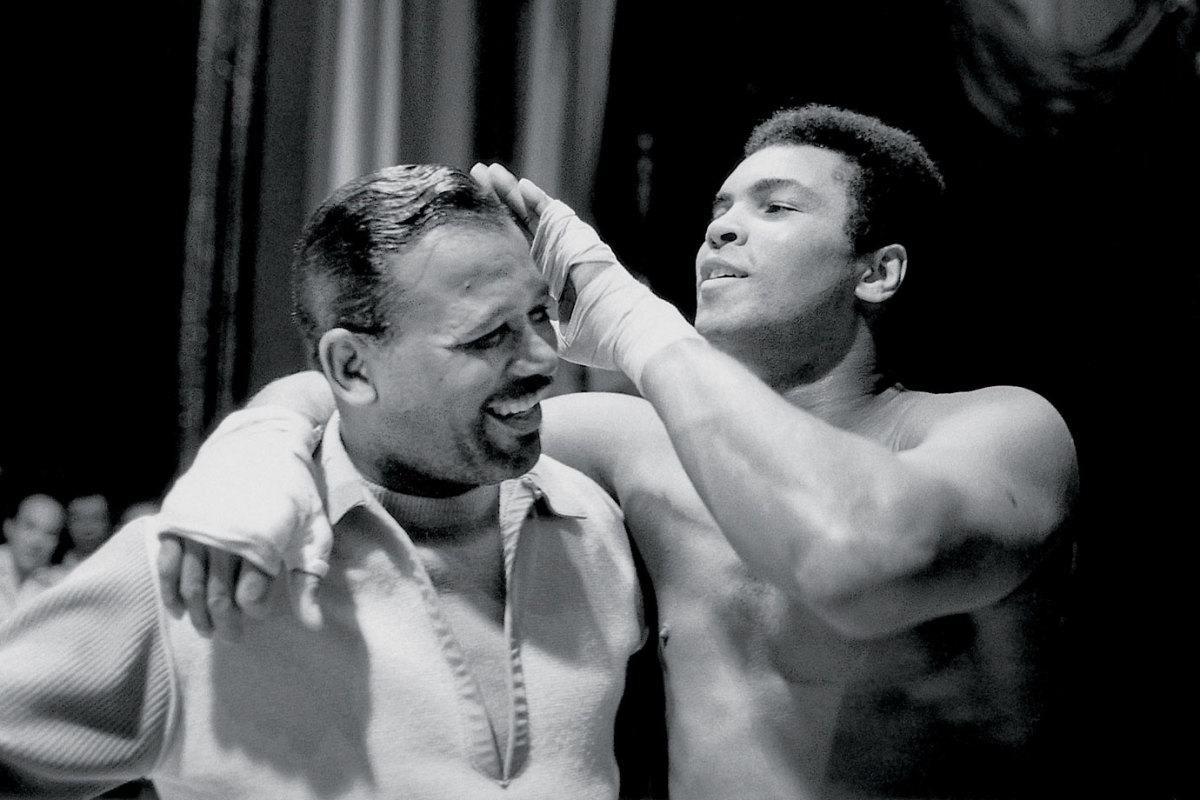

Ali plays with Sugar Ray Robinson's hair in the locker room before his bout with Bugner. The former welterweight and middleweight champion was Ali's childhood idol.

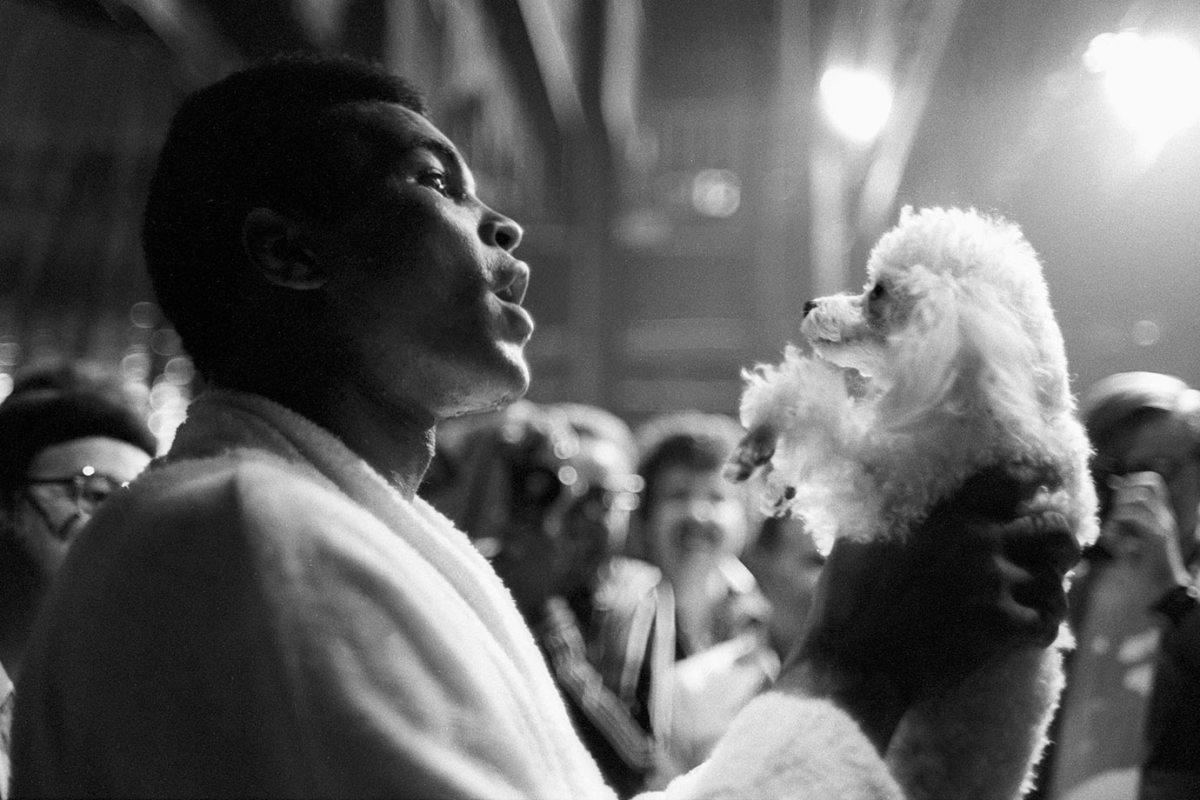

Before the fight with Bugner, Muhammad Ali enjoys a relaxed moment with a poodle at Caesars Palace Hotel. He won the fight with Bugner by unanimous decision.

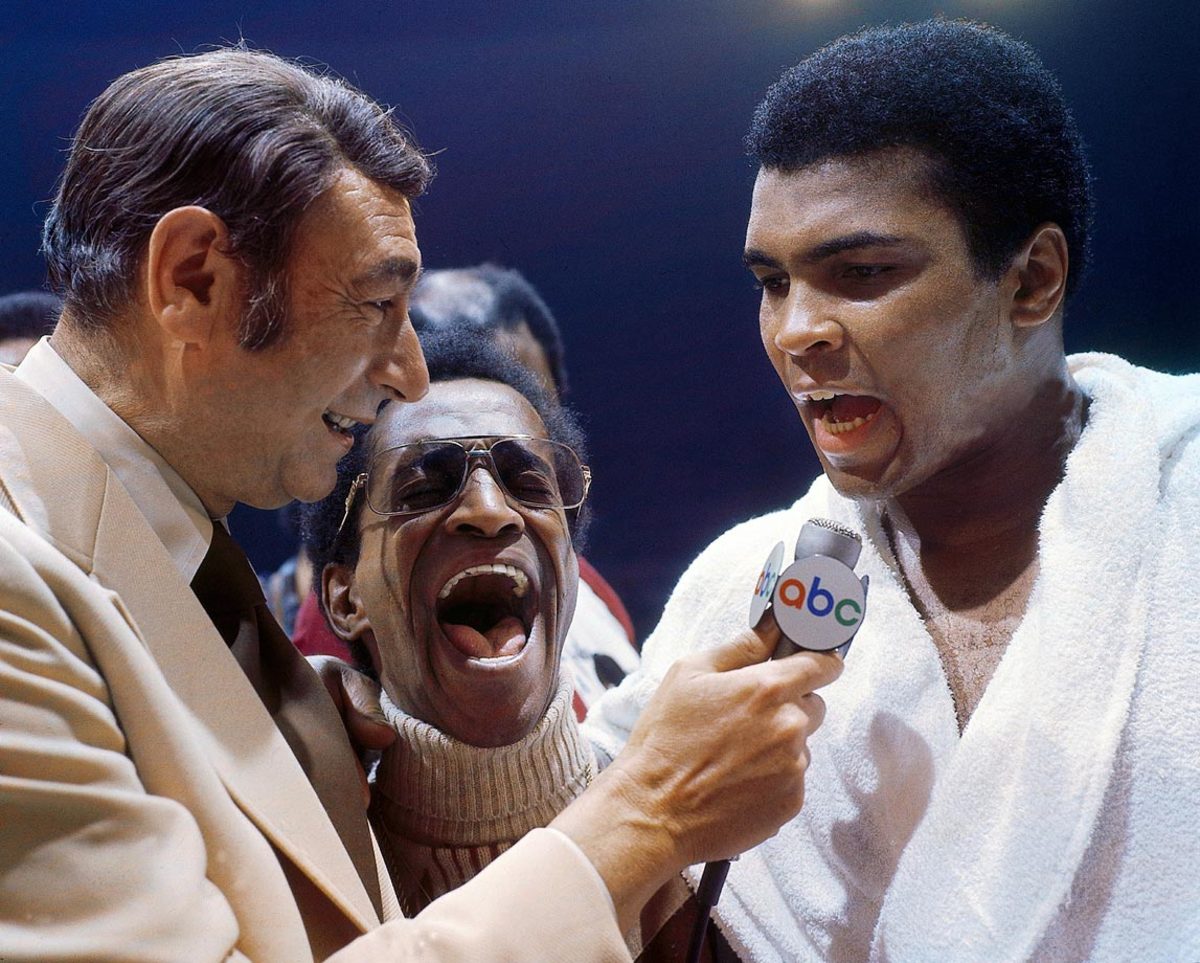

Howard Cosell interviews Ali, with entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. in the middle, after his victory over Joe Bugner by unanimous decision in. Although the fight was never in jeopardy of getting away from him, Ali praised Bugner's legs and said he could be a champion in a few years.

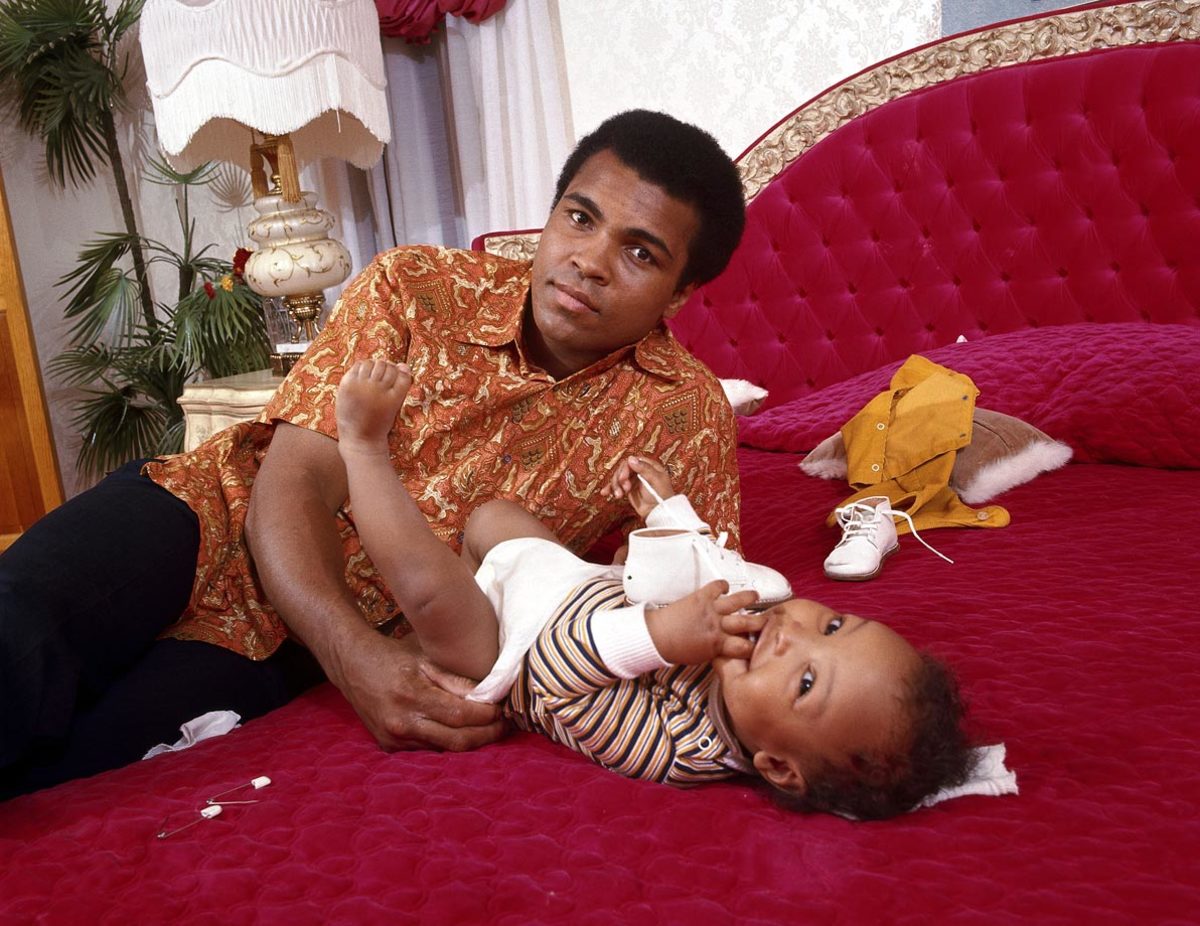

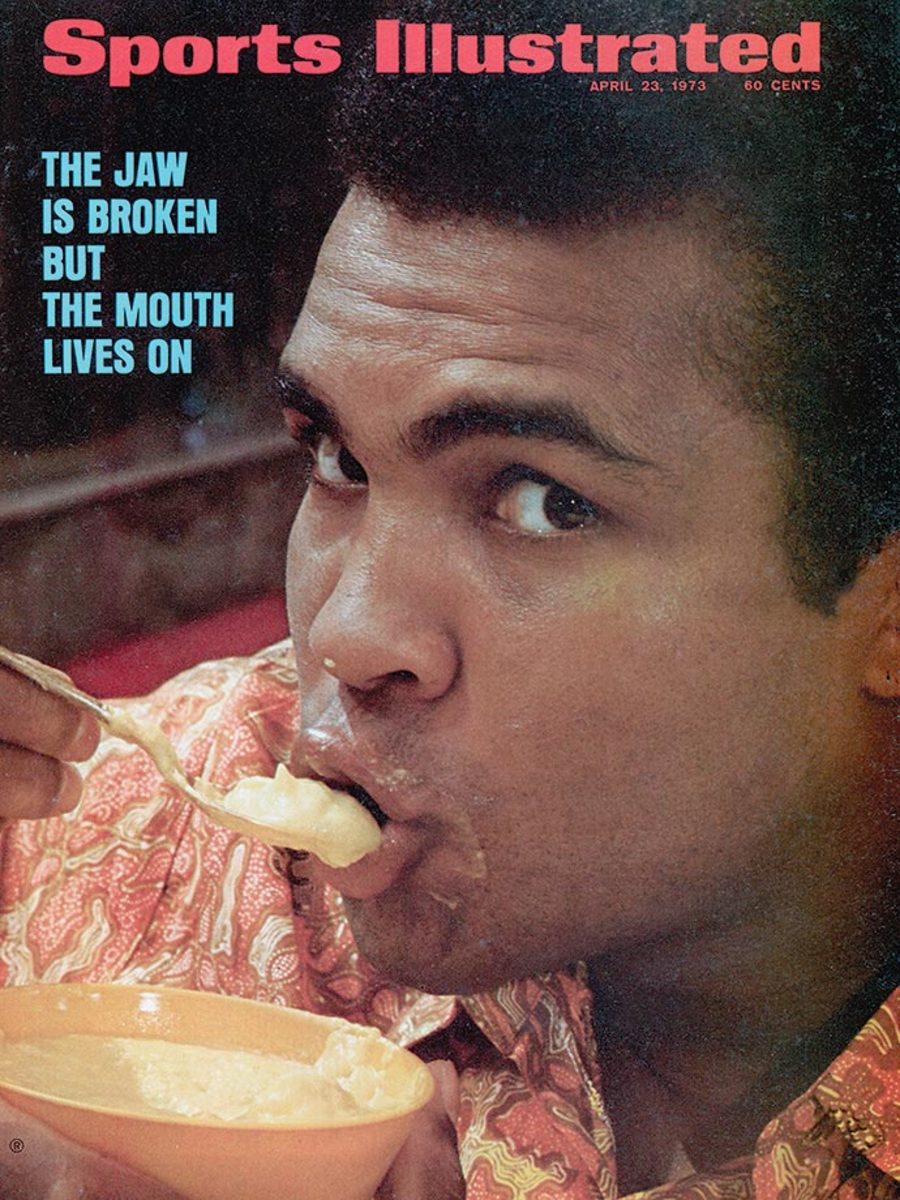

Ali changes the diaper of his son in his bedroom during a photo shoot at the family's home in April 1973. Ali had suffered a broken jaw less than a month earlier in his fight against Ken Norton.

In the wake of his split decision loss to Norton, Ali plays with his son in his bedroom at home in Cherry Hill, N.J.

Ali kisses his daughter Jamillah outside of their home following the loss to Norton, just the second defeat of his career.

The Ali family standing outside their New Jersey home. To the right of Muhammad Ali are his twin daughters, Jamilllah and Rasheda, daughter Maryum and his wife, Khalilah, holding their son Ibn Muhammad Ali Jr.

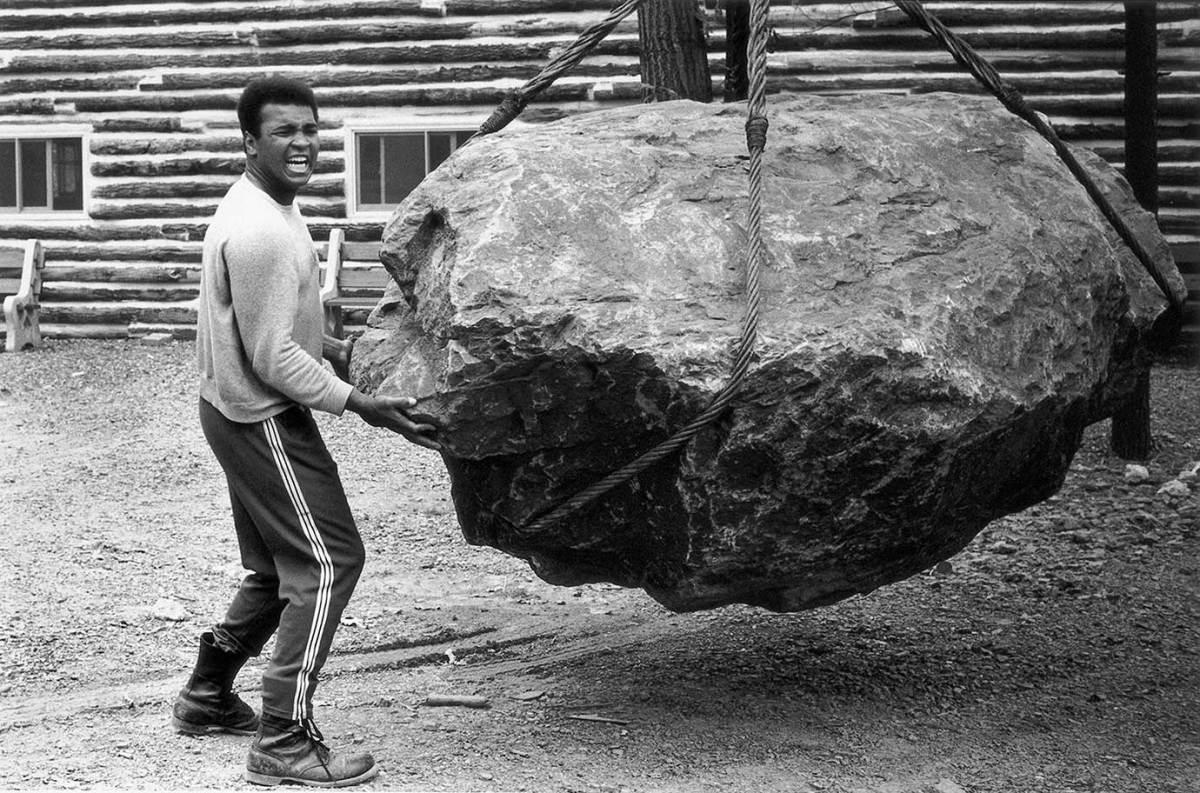

At his training camp cabin, Ali pushes a boulder during a photo shoot in Deer Lake, Penn., in August 1973. Ali was training for his rematch against Ken Norton, who broke his jaw five months earlier.

Ali chops wood at his cabin in Deer Lake. He referred to the training camp as "fighter's heaven" and used it to prepare for fights away from the spotlight.

The fighters weigh in on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson ahead of Ali and Ken Norton's September 1973 fight.

Johnny Carson listens to Ali on the Tonight Show three days before his rematch with Norton. Ali would avenge his earlier loss to Norton, winning a narrow split decision.

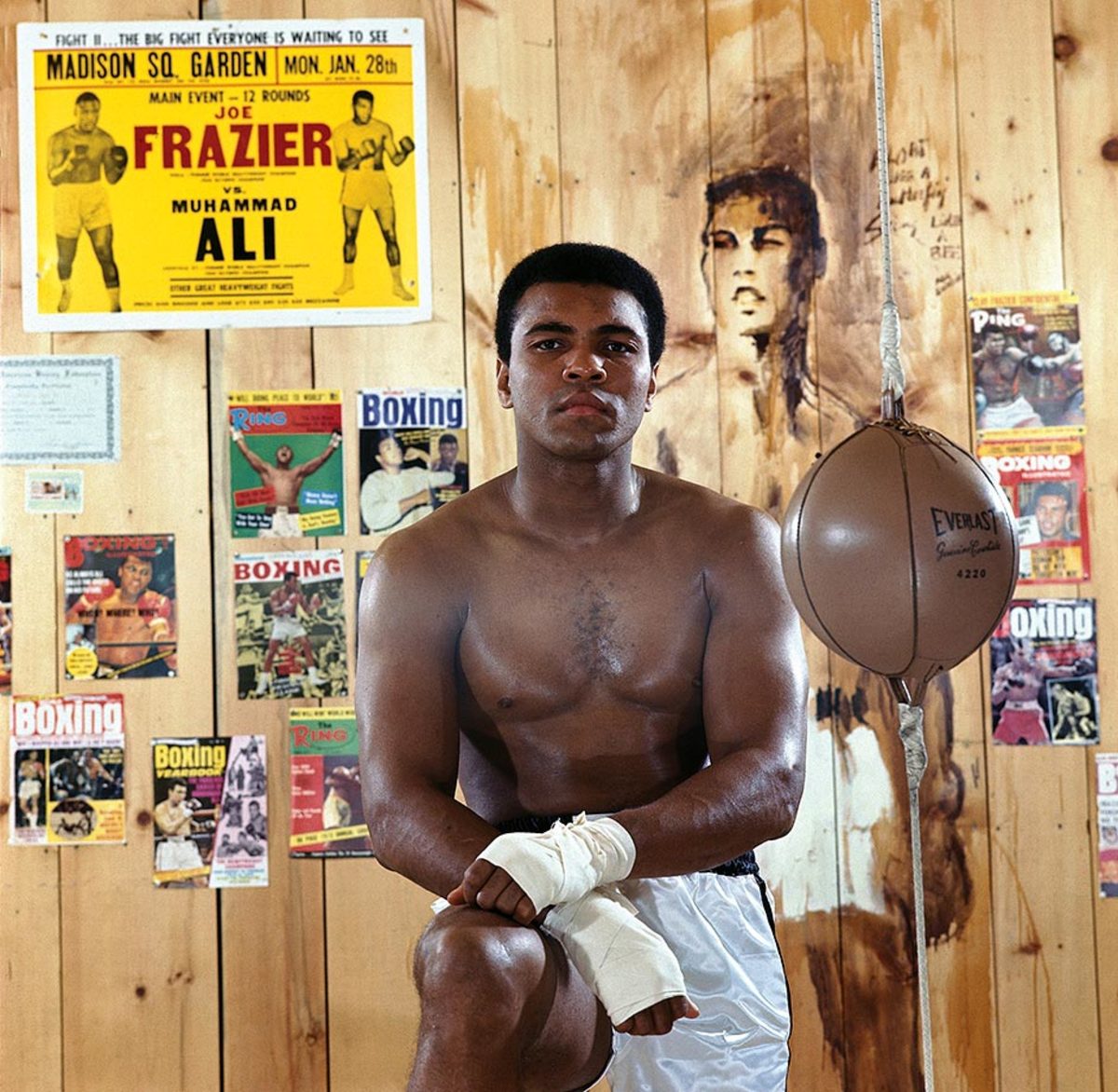

Ali poses in front of posters and magazine covers from throughout his career at his training camp cabin in Deer Lake in 1974.

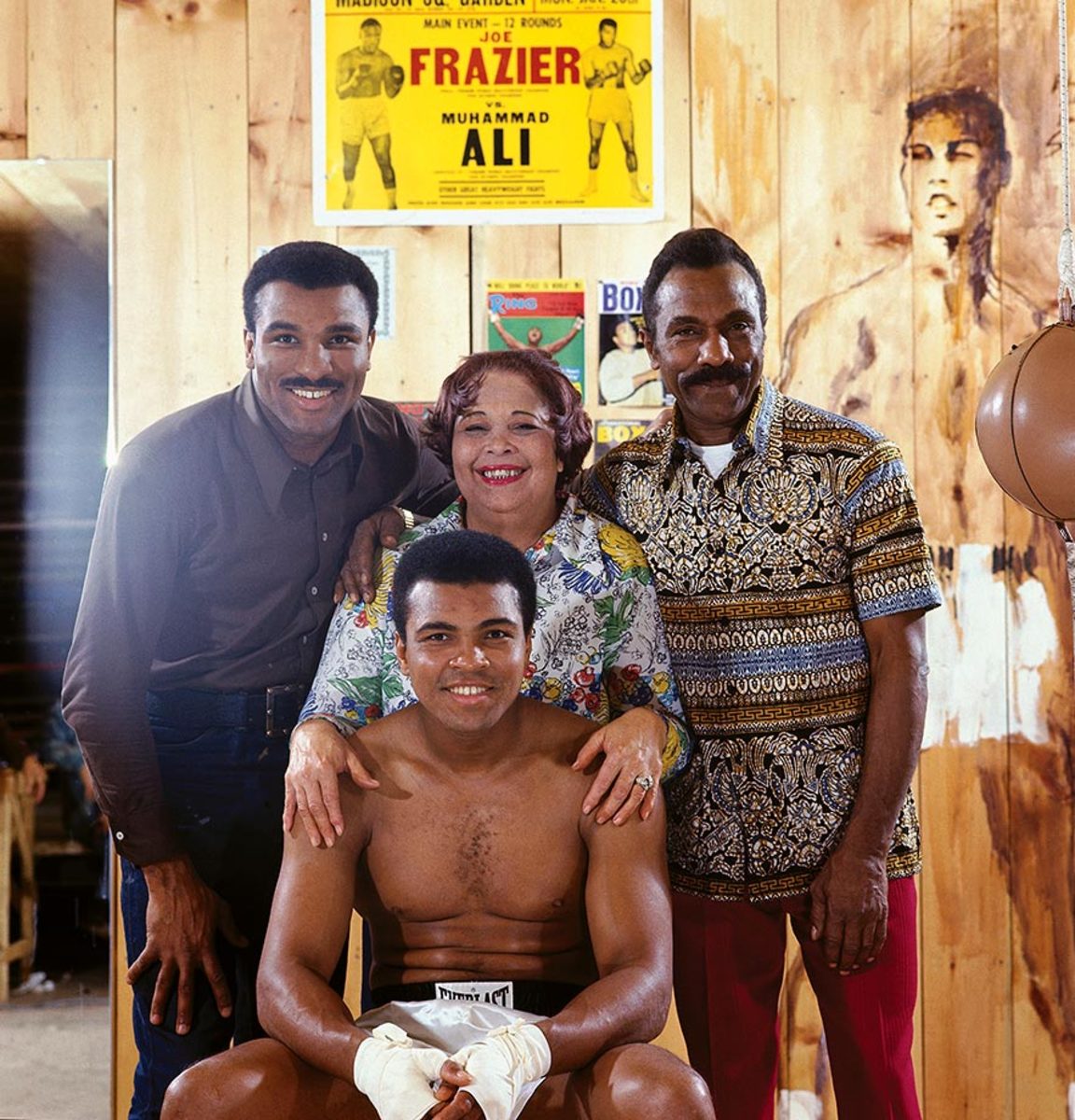

Ali poses with members of his family in front of a poster from his first fight with Joe Frazier. Ali's brother, Rahman Ali; mother, Odessa Clay; and father, Cassius Clay Sr. stand behind the boxer.

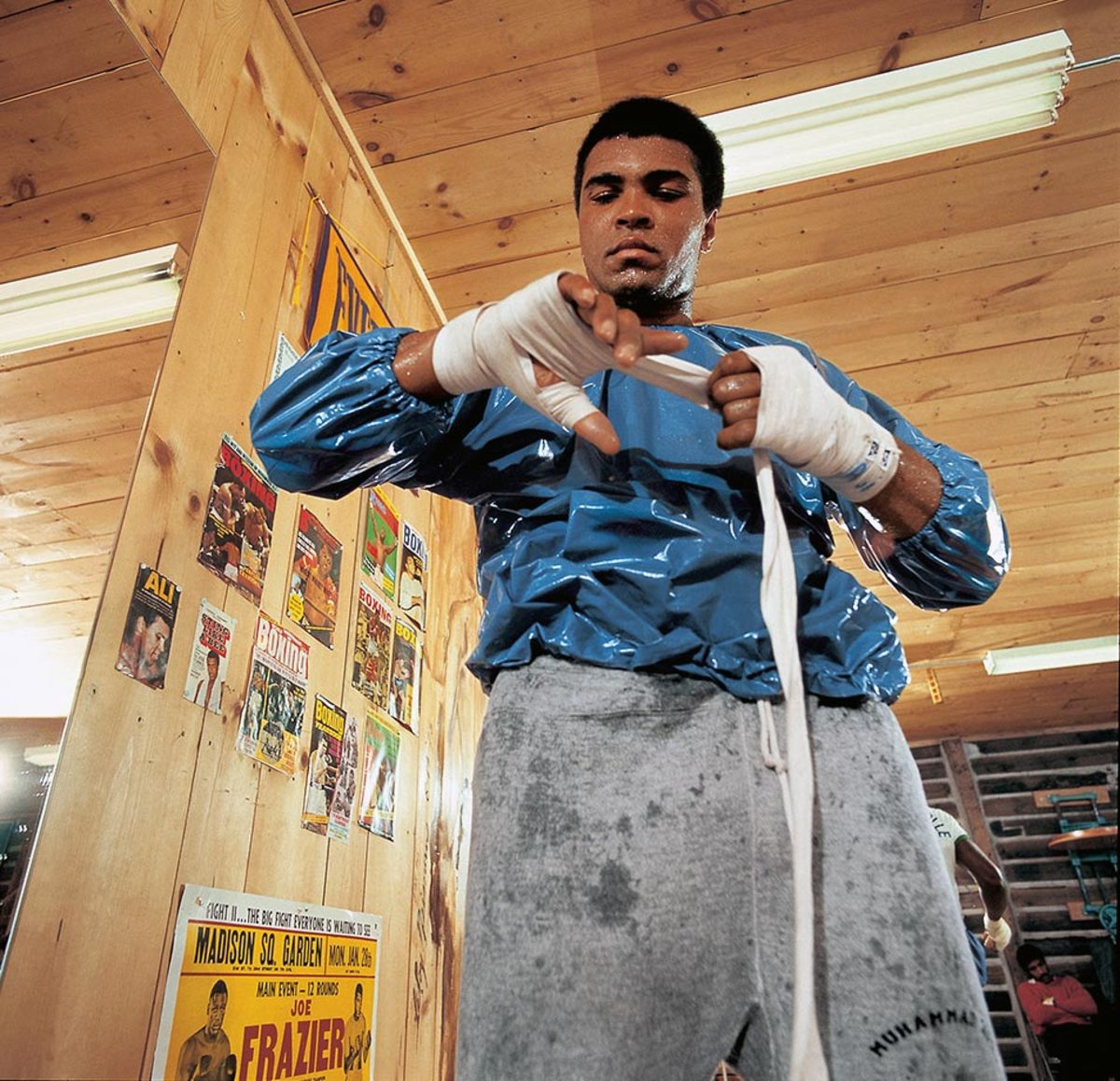

Less than three weeks before his rematch with Joe Frazier on Jan. 28, 1974, Ali wraps his hands while wearing a sauna suit at his training camp cabin.

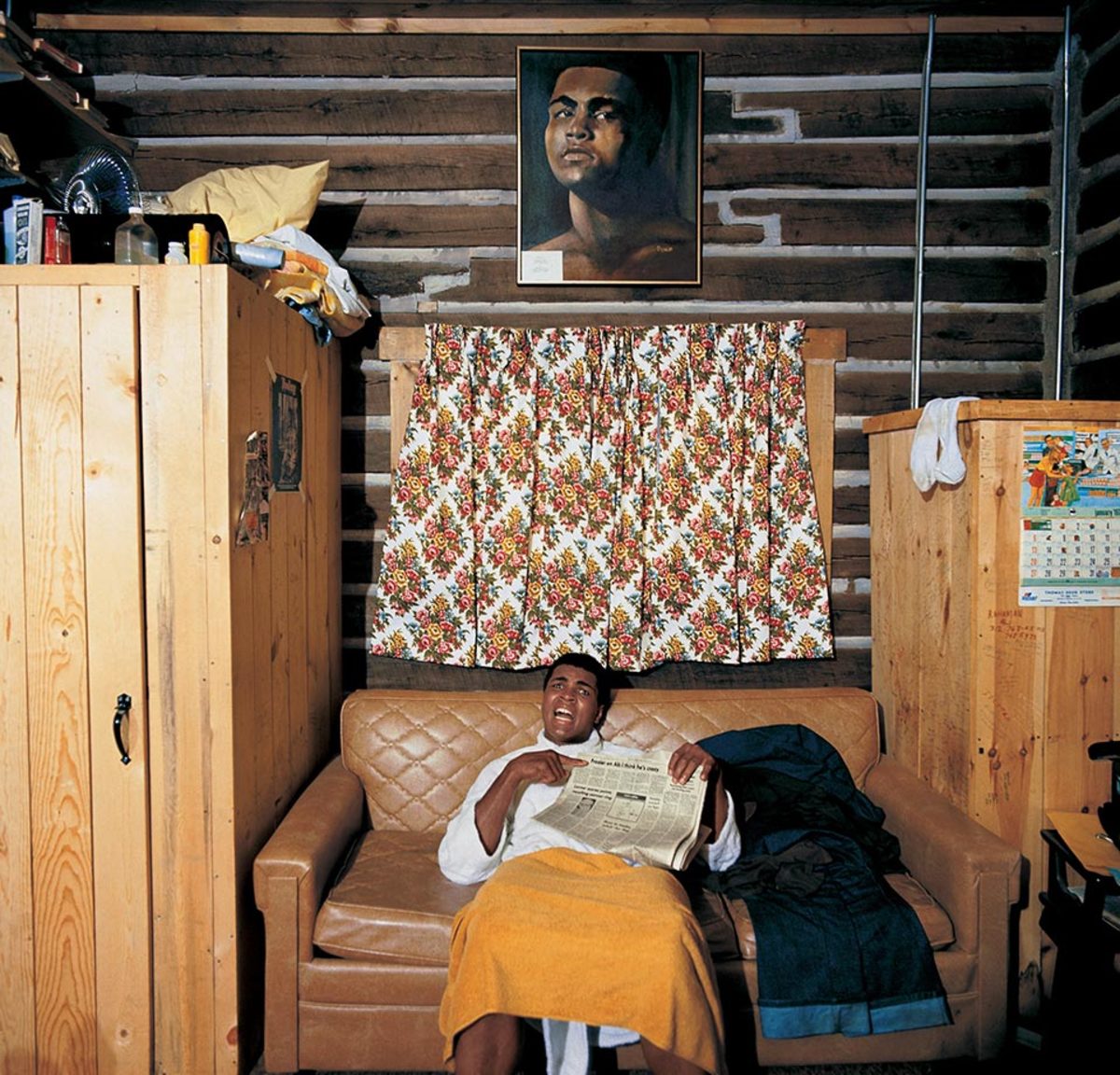

Ali holds a newspaper at his cabin in January 1974. He is pointing to a headline that reads, "Frazier On Ali, I Think He's Crazy." Ali and Frazier fought for the second time later that month with Ali winning by a unanimous decision.

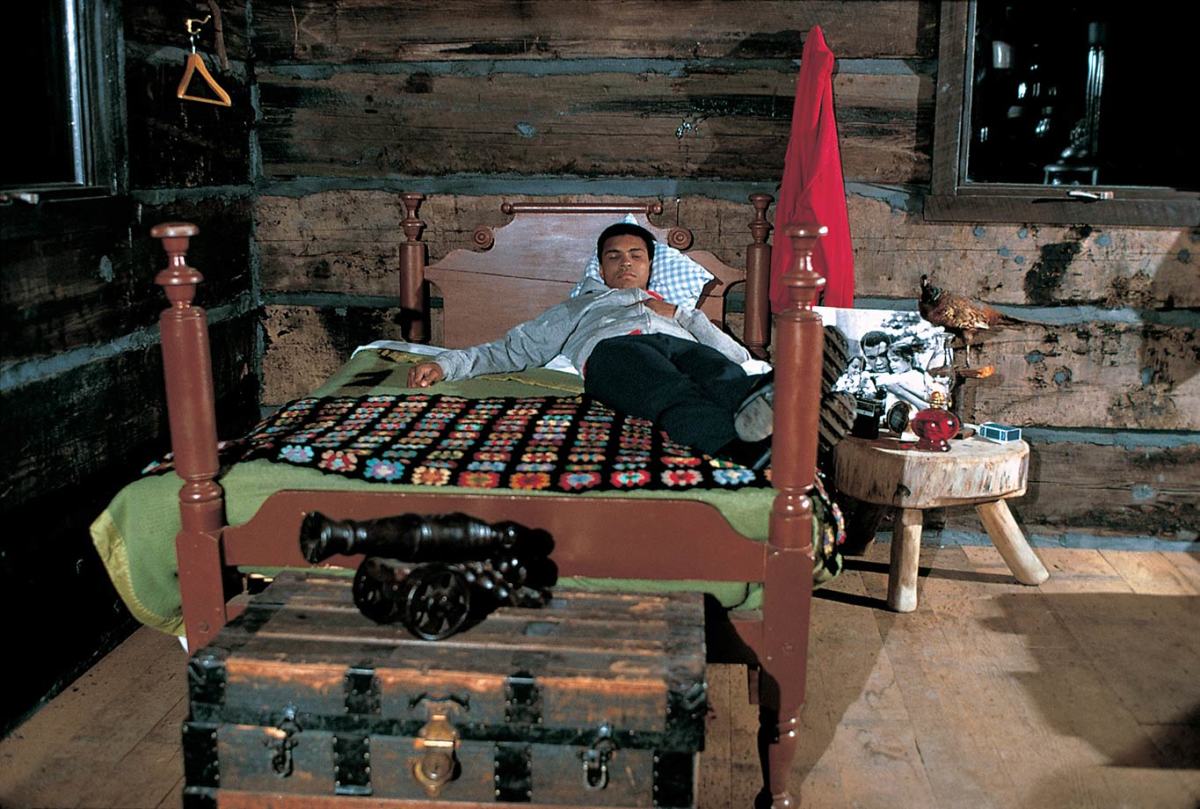

Ali lies on his bed at his cabin during the January 1974 photo shoot.

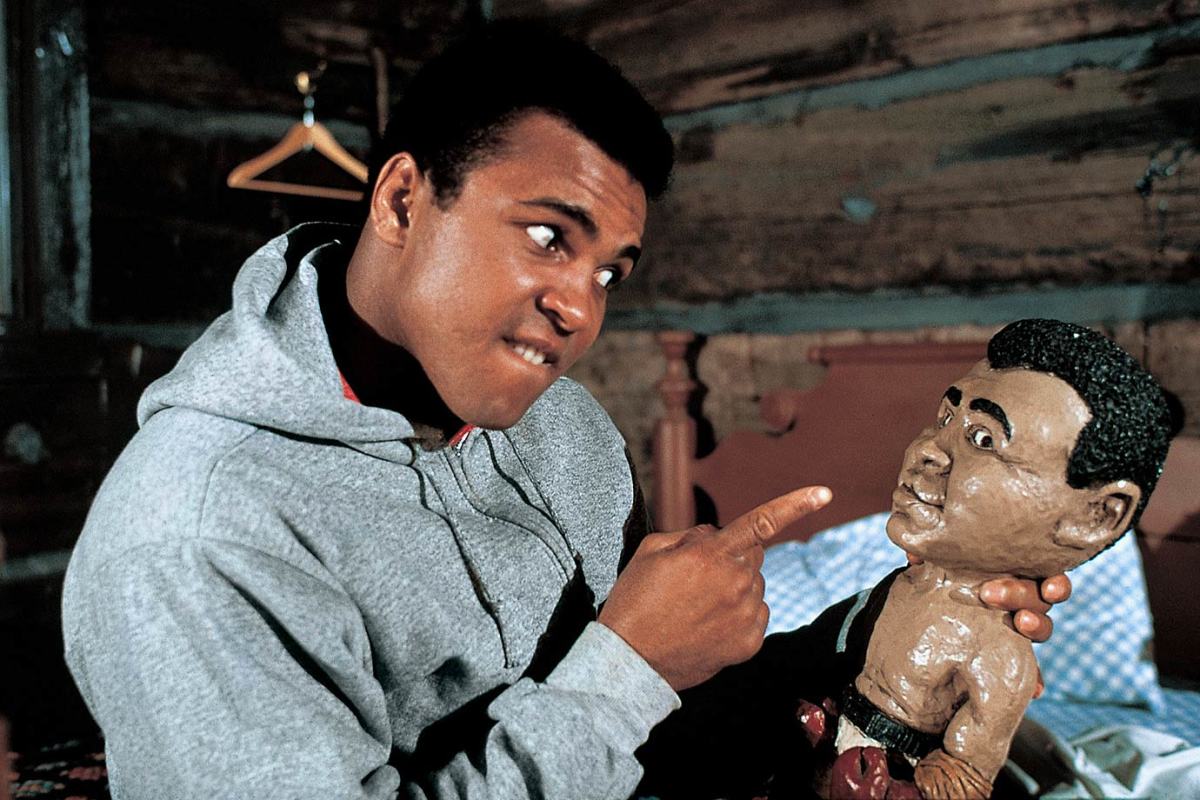

His smaller incarnation stares straight back as Ali plays with a doll of himself during the same 1974 shoot at his training camp cabin.

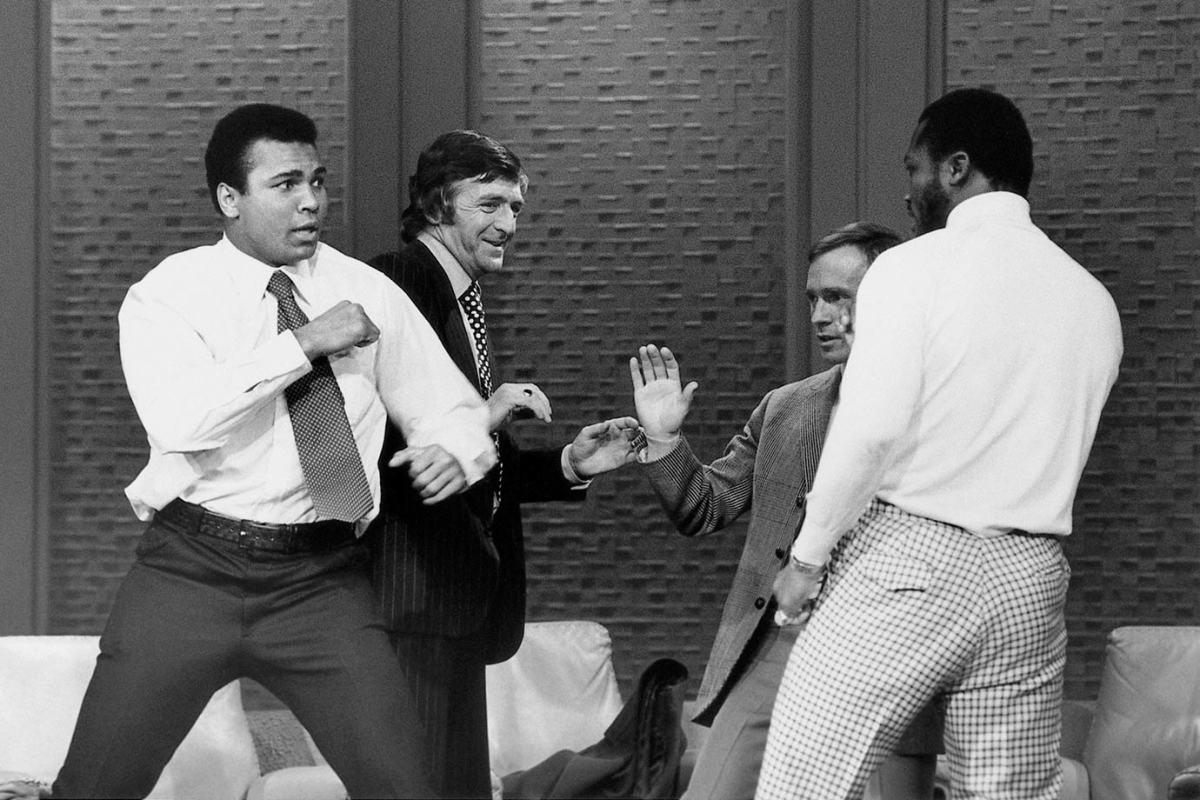

Ali and Joe Frazier fight on the set of The Dick Cavett Show while reviewing their 1971 bout in advance of their 1974 rematch. Ali called Frazier ignorant, to which Frazier took exception. As the studio crew tried to calm Frazier down, Ali held Frazier by the neck, forcing him to sit down and sparking a fight. The television set fight amped up anticipation of their January 1974 bout.

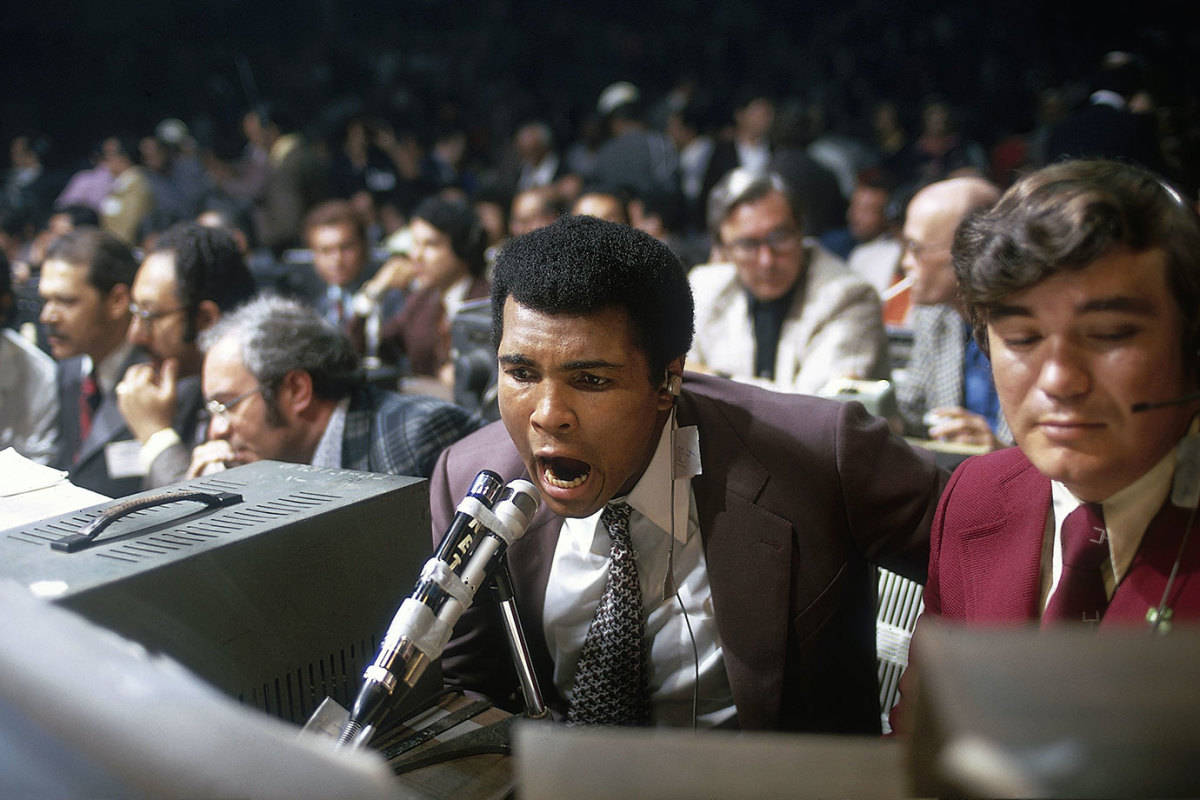

Exploring a different side of the sport, Ali broadcasts the fight between George Foreman and Ken Norton in March 1974. Foreman won the fight by technical knockout in the second round, setting up the showdown with Ali in Zaire.

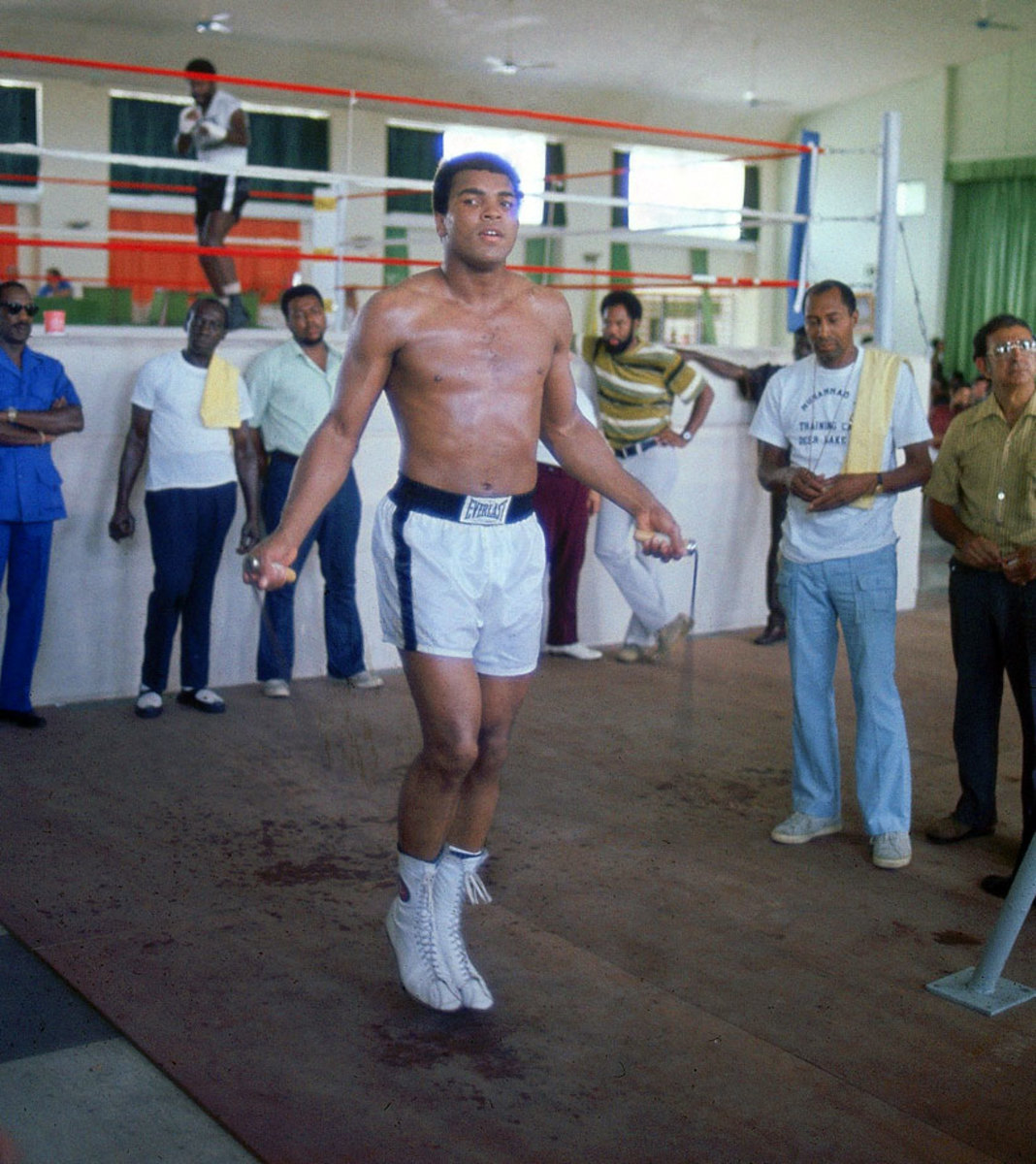

Ali jumps rope at the Salle de Congres in Kinshasa, Zaire, while training for his heavyweight title fight against George Foreman. Both Ali and Foreman spent most of the summer of 1974 training in Zaire to adjust to the climate.

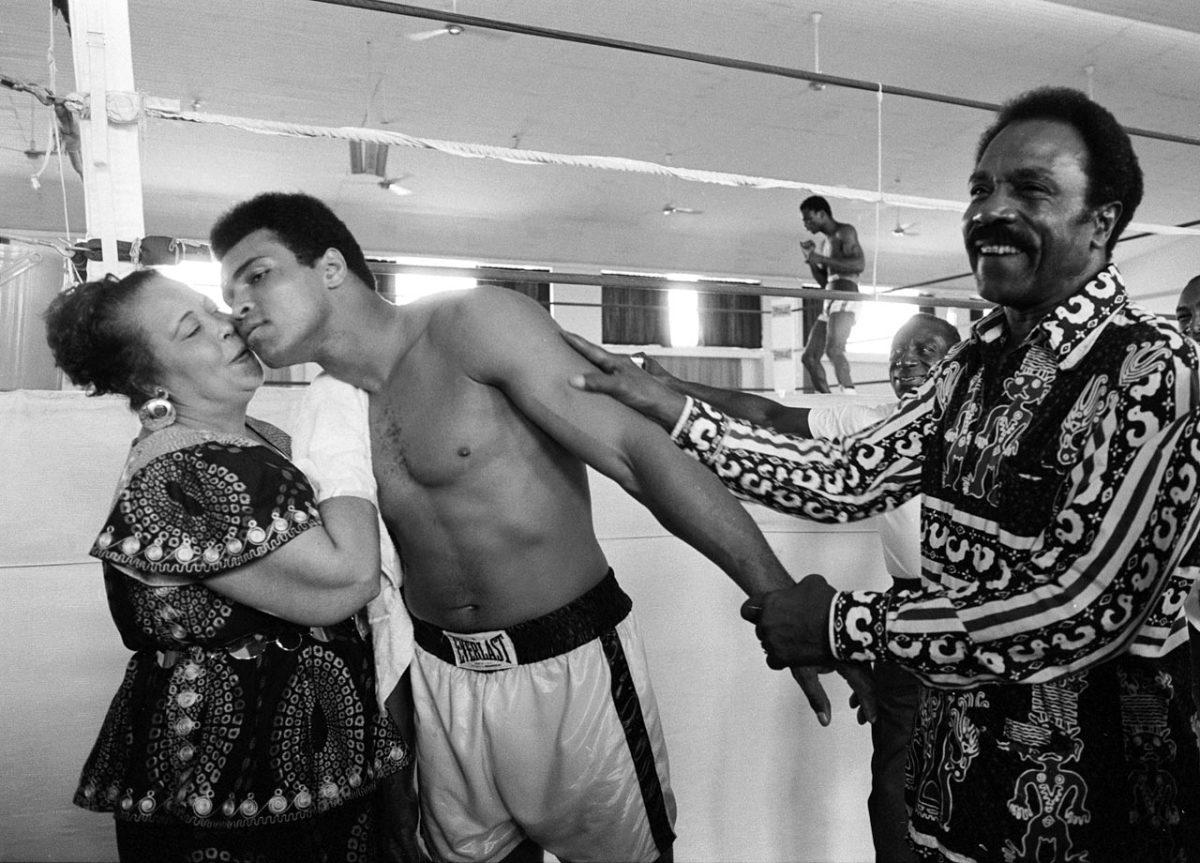

While training before his fight with George Foreman, Ali kisses his mother, Odessa Clay, while his father, Cassius Clay Sr., looks on. Ali's superior strategy and ability to take a punch led him to his upset victory as he absorbed body blows from Foreman before he responded with powerful combinations to Foreman's head.

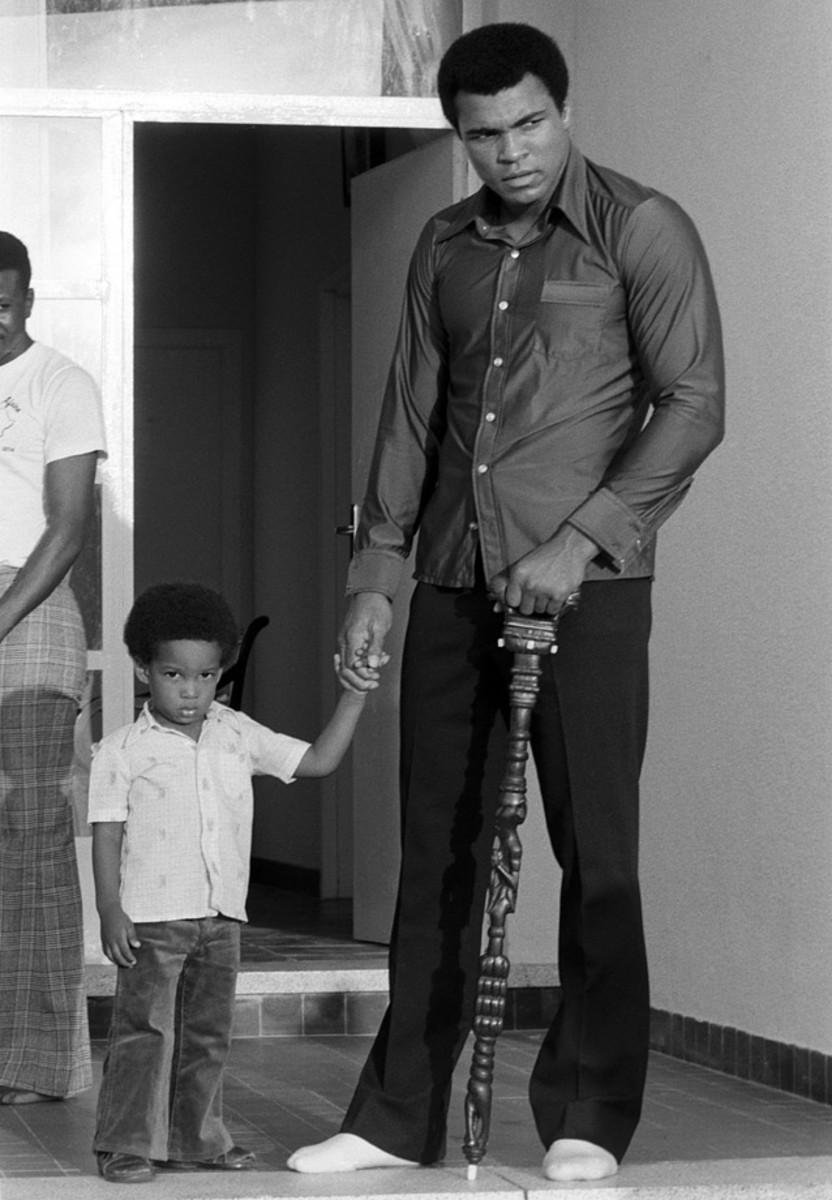

Four days before the fight, Ali holds the hand of his son Ibn in Zaire. Ali successfully courted the favor of the Zaire crowd, prompting chants of "Ali bomaye!" — translated as "Ali, kill him!"

Ali poses in front of the Le Militant statue at the presidential complex that was the site of Ali's January heavyweight title bout with Foreman. The fight was originally set for a month earlier, but Foreman suffered a cut near his eye during training, forcing a delay.

Ali stands against the railing on the River Zaire watching the sunset four days before the Rumble in the Jungle. The fight was sponsored by Zaire to achieve the $5 million purse promoter Don King had promised both Ali and Foreman.

Before employing his famous rope-a-dope strategy against Foreman, Ali makes a face at the camera. Ali allowed Foreman to throw many punches but only into his arms and body, and when Foreman tired himself out from the mostly ineffective punches, Ali took control of the fight.

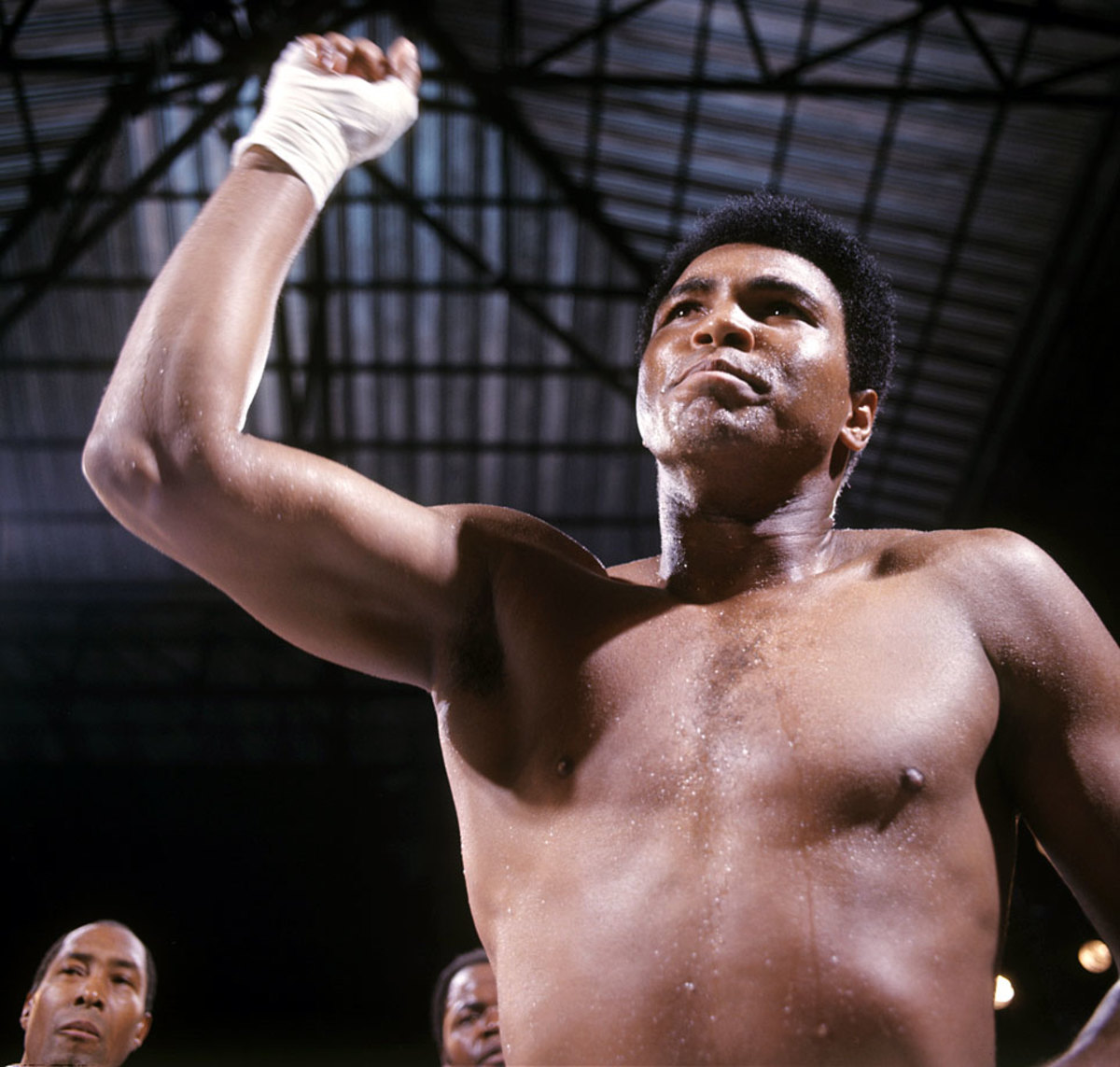

Ali points before his bout with Foreman. The victory over his favored opponent made him the heavyweight champion of the world for the first time since he was stripped of his titles in 1967.

Ali stares at George Foreman during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali earned his shot at the heavyweight title by defeating Joe Frazier in January 1974, avenging a loss three years earlier.

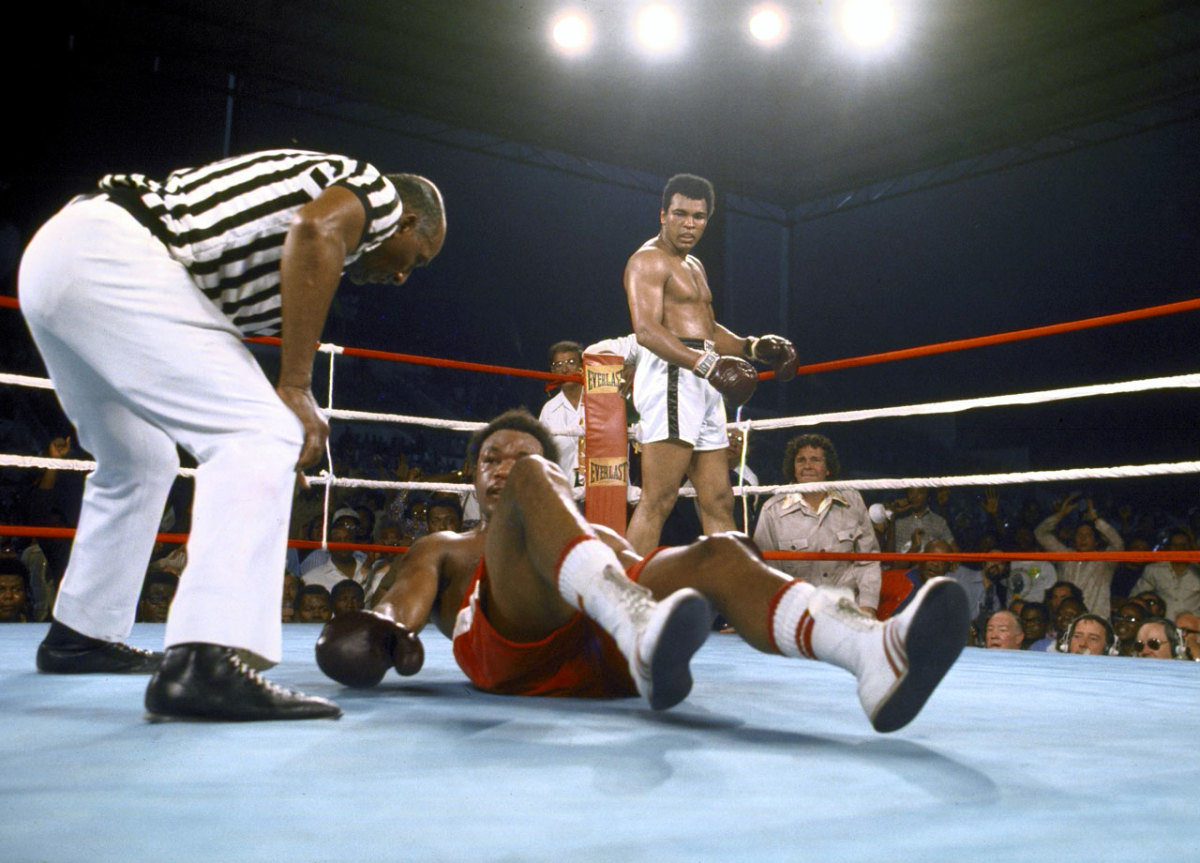

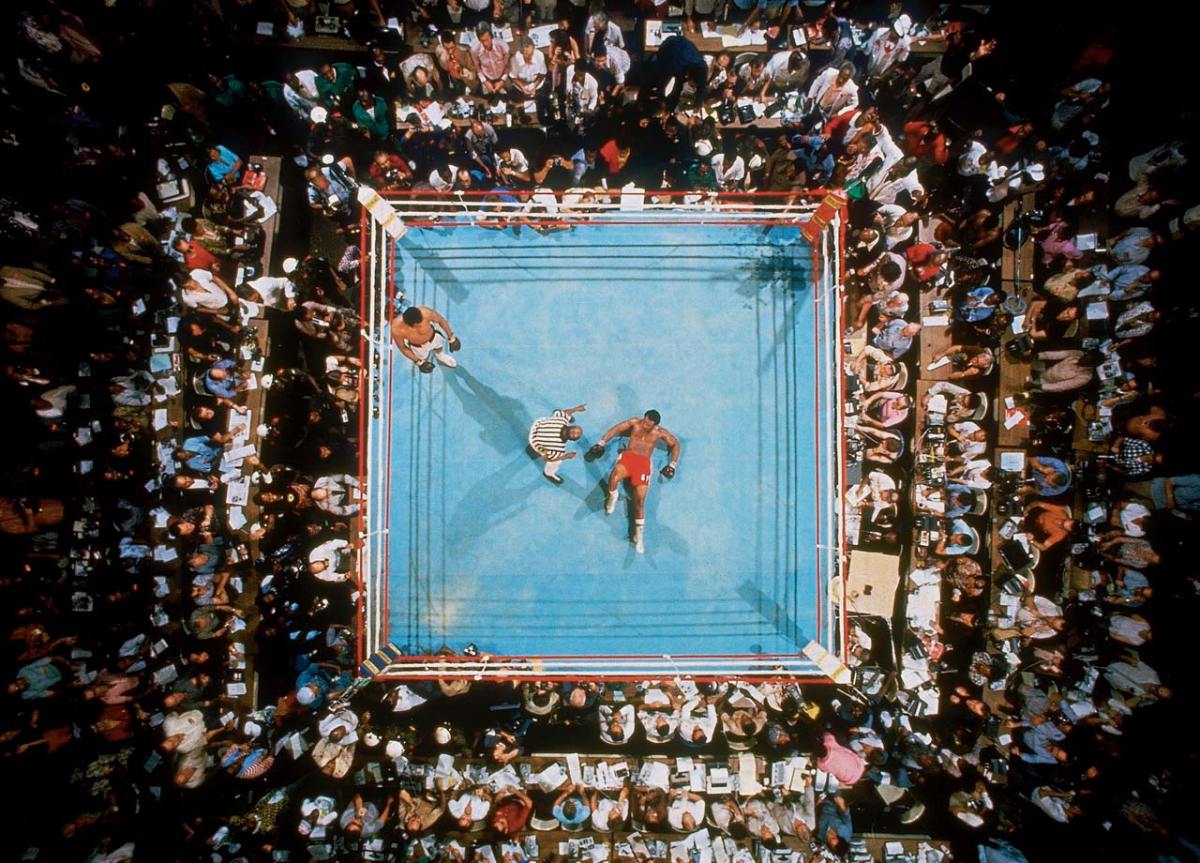

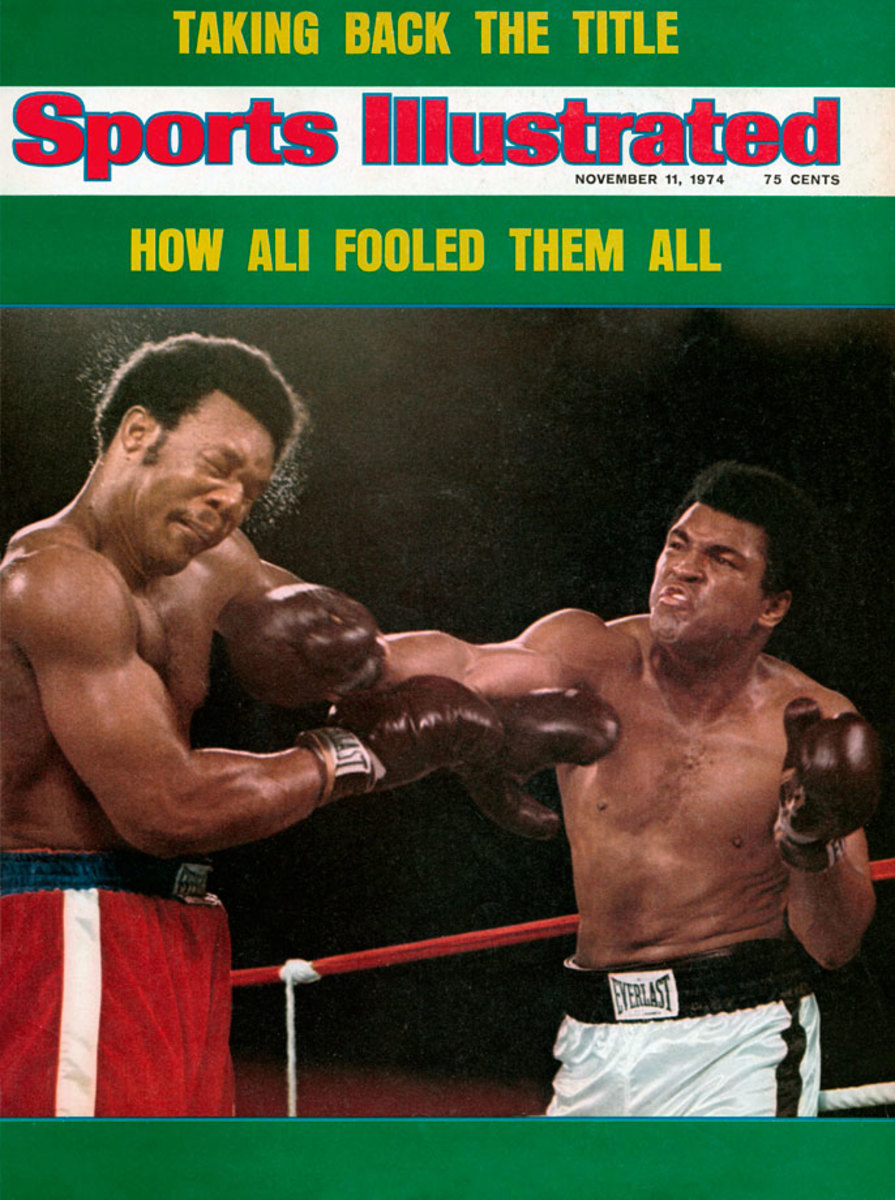

Foreman lies down on the canvas as Ali stands in the background during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali knocked Foreman down with a five-punch combination in the eighth round, and referee Zack Clayton counted him out.

Big George stares at the ceiling as referee Zack Clayton counts him out in the eighth round. The victory made Ali, once again, the heavyweight champion of the world.

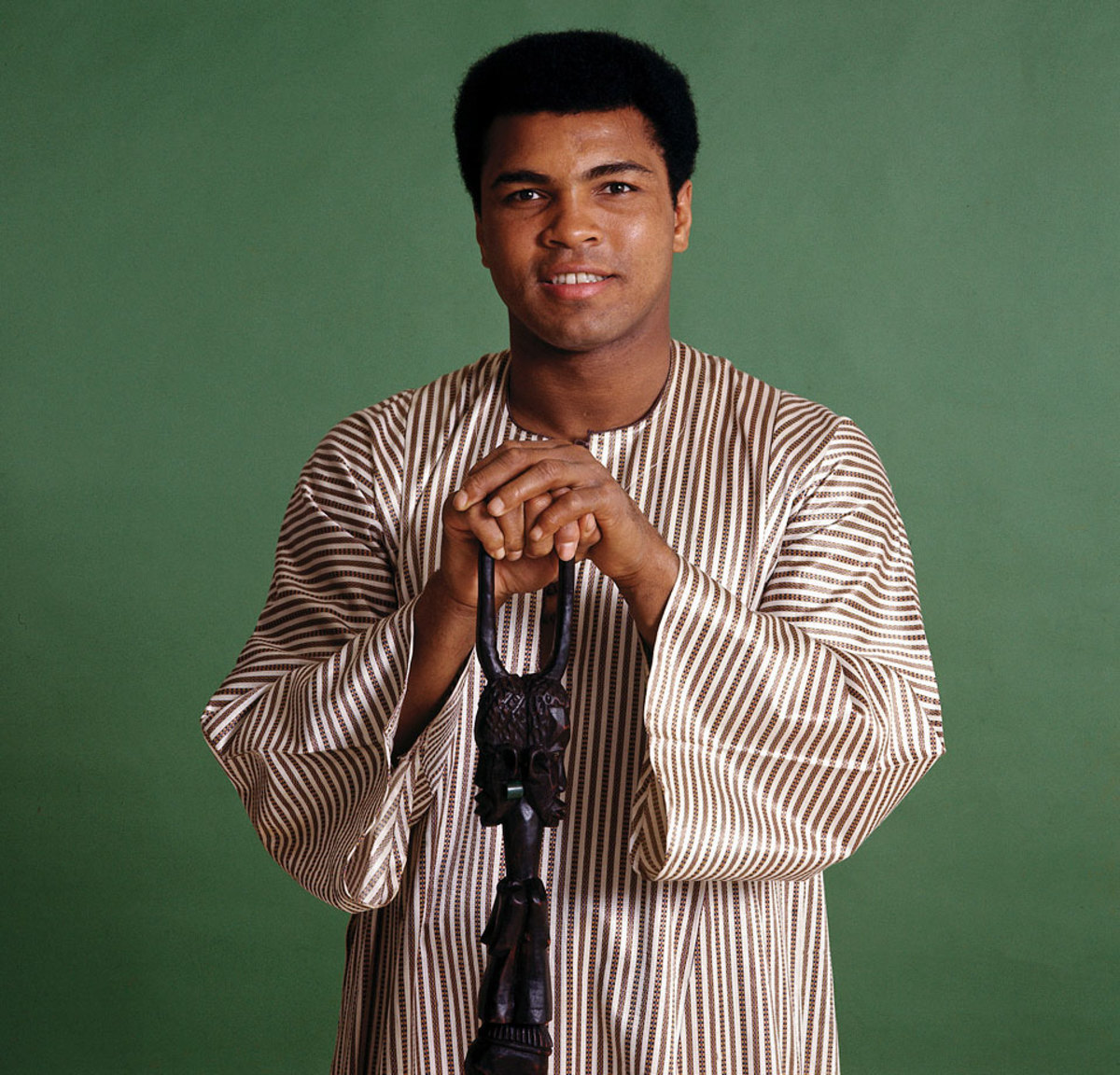

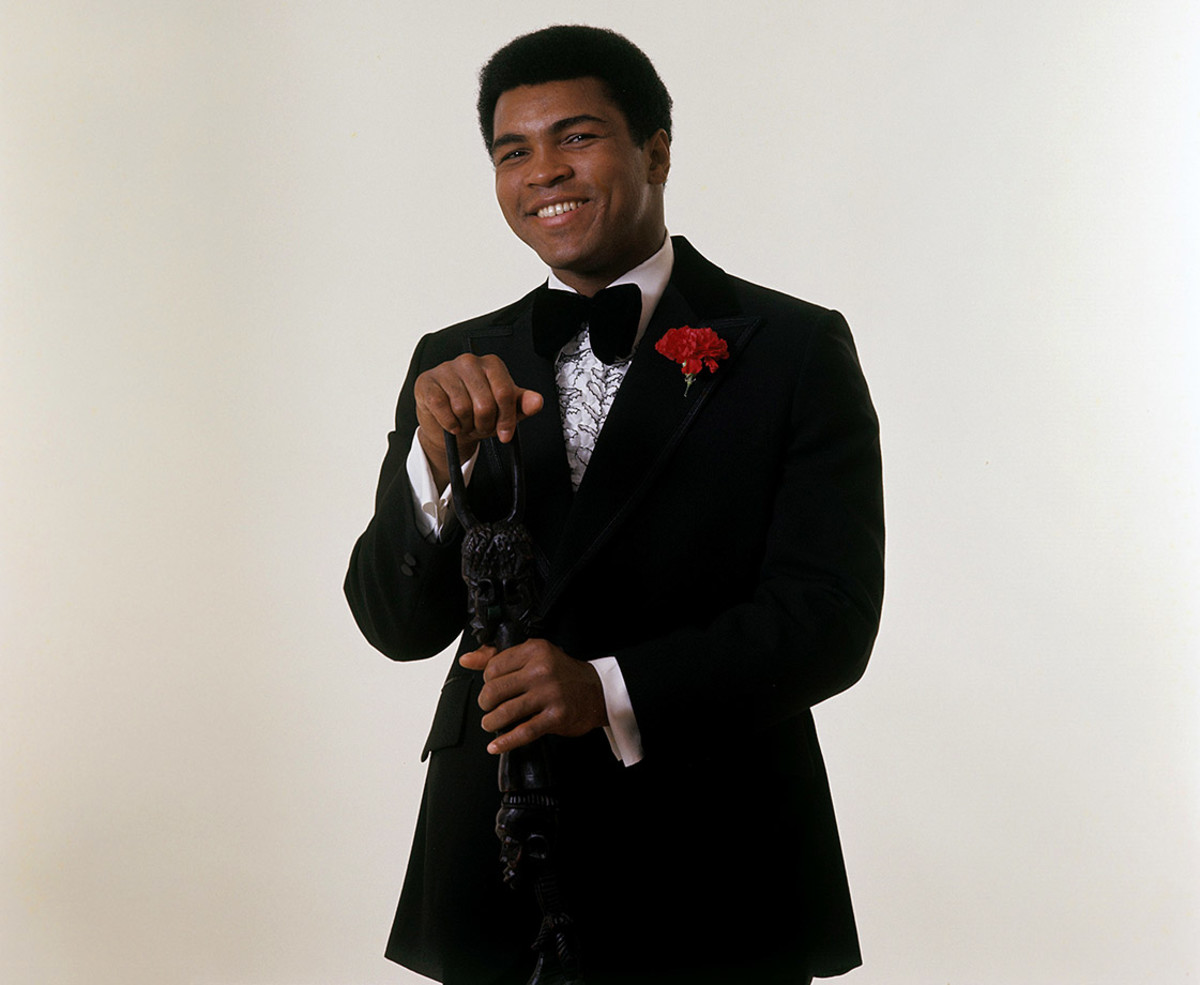

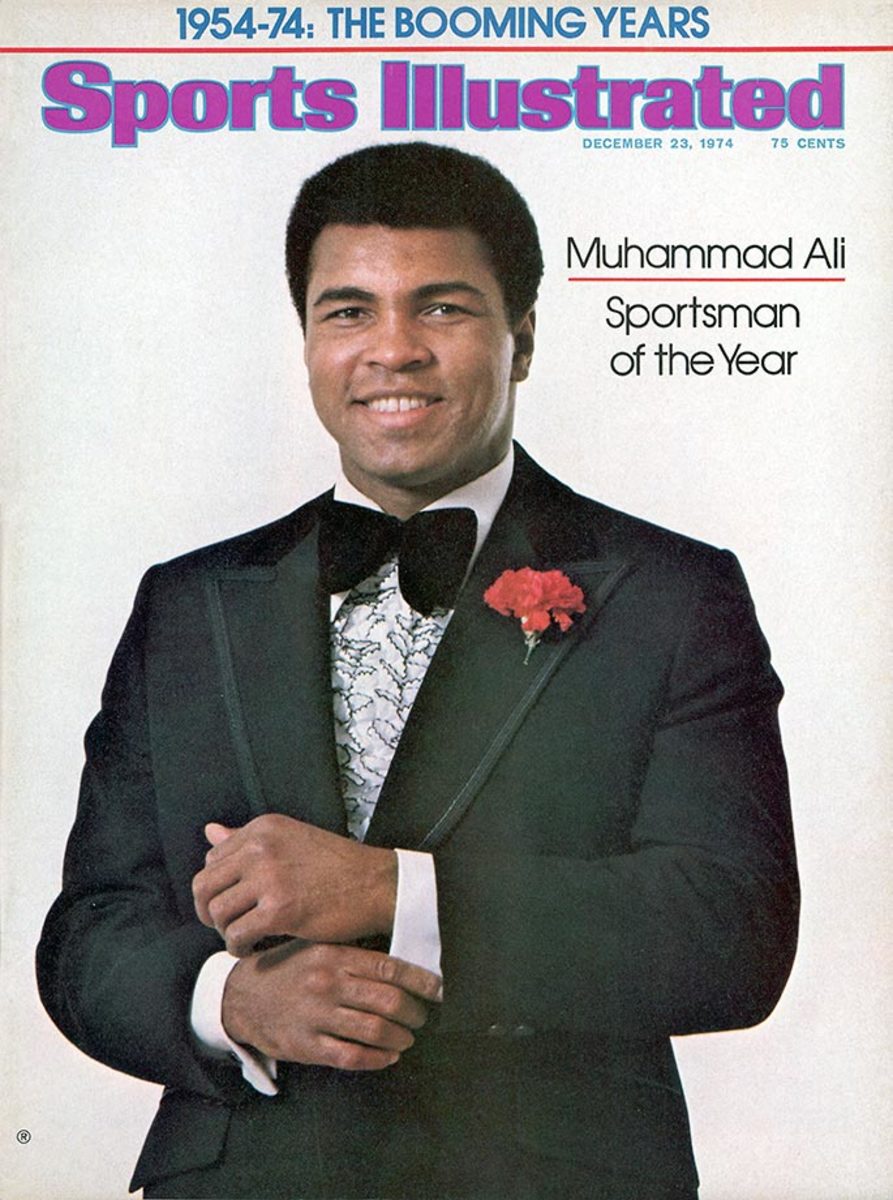

Ali poses for a portrait after being selected as the Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year in 1974. Ali wore a dashiki, a men's garment widely worn in West Africa. He also brought the walking stick given to him by Zaire's president.

This time Ali wears a tuxedo, but keeps the walking stick, during the November photo shoot for Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year.

Ali talks with Howard Cosell outside of the United Nations Headquarters for a segment on the Wide World of Sports. Later that day, Ali held a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

Ali talks with Reverend Jesse Jackson outside of the United Nations Headquarters before a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

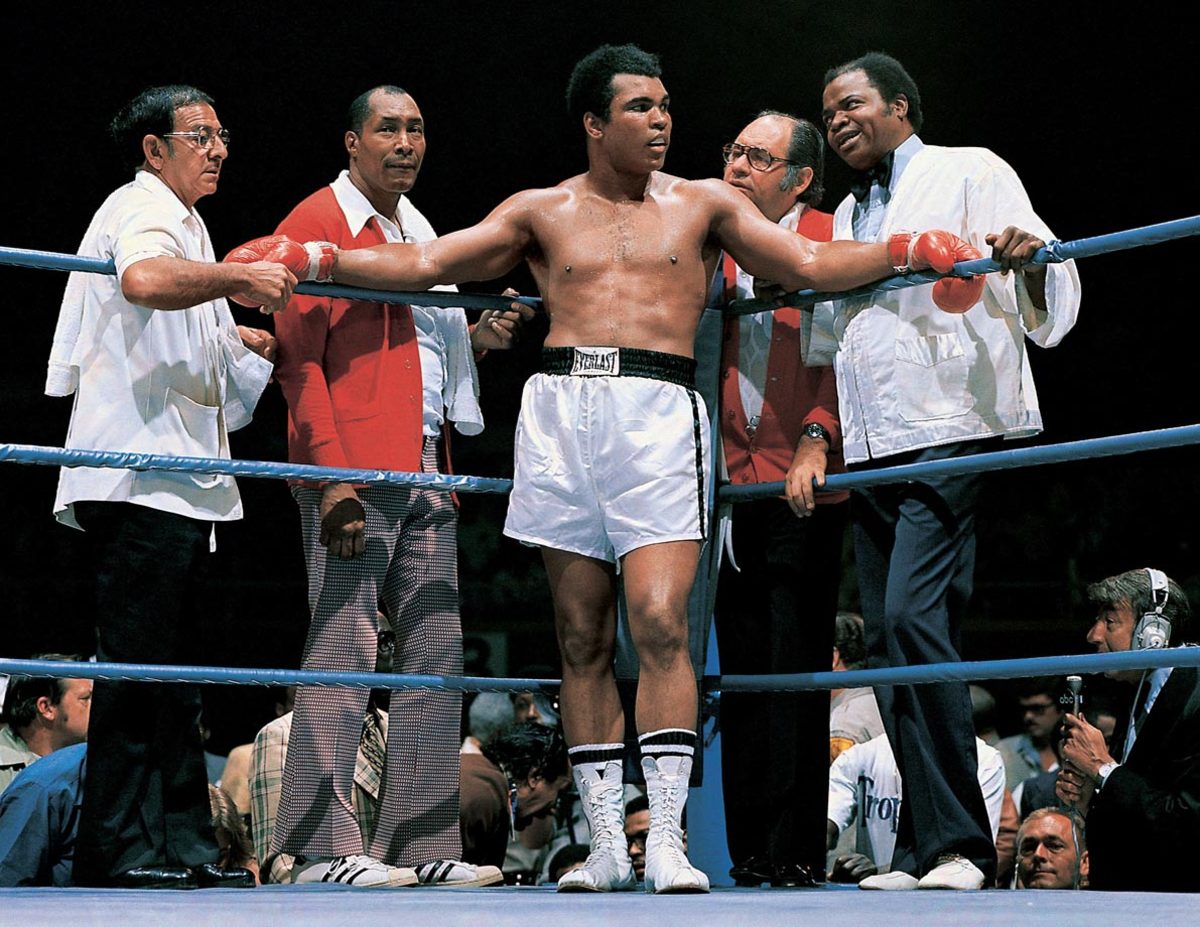

Ali stands with trainer Angelo Dundee, assistant trainer Wali Muhammad, physician Dr. Ferdie Pacheco and assistant trainer Drew Bundini Brown before his bout with Ron Lyle in May 1975. Ali won the fight by technical knockout in the 11th round.

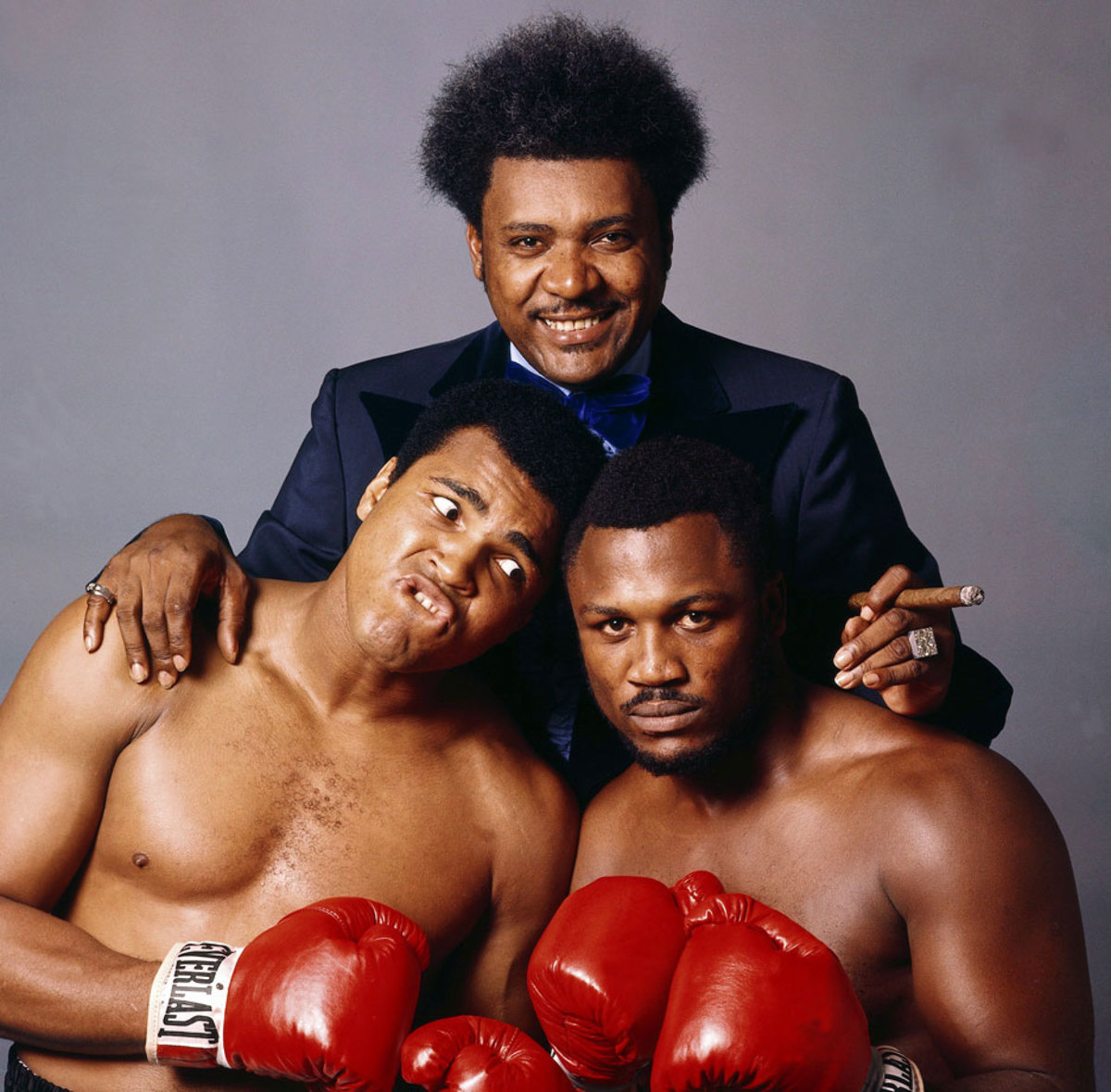

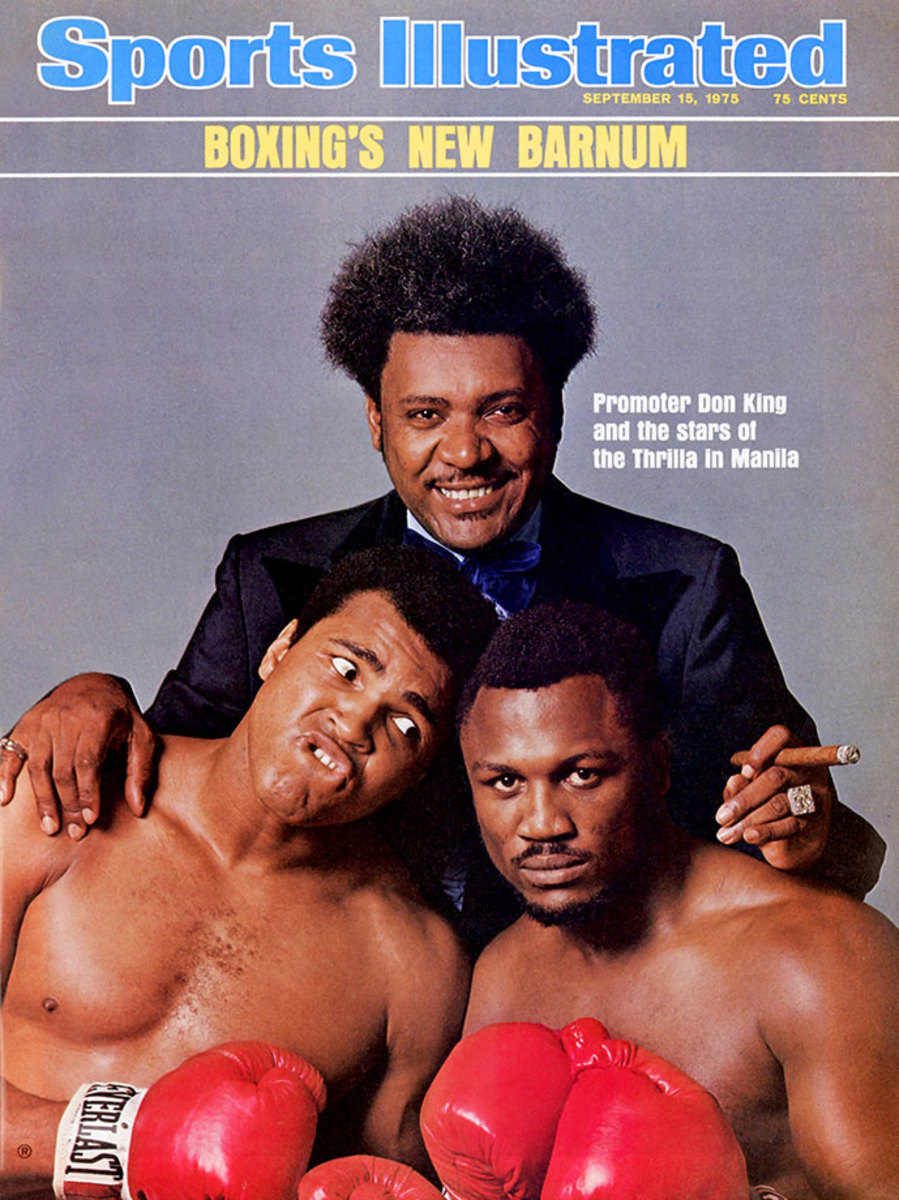

Along with Don King and Joe Frazier, Ali sat for a portrait leading up to the Thrilla in Manila. Ali verbally abused Frazier during the buildup to the fight, telling the media that "it will be a killa and a thrilla and a chilla when I get the gorilla in Manila."

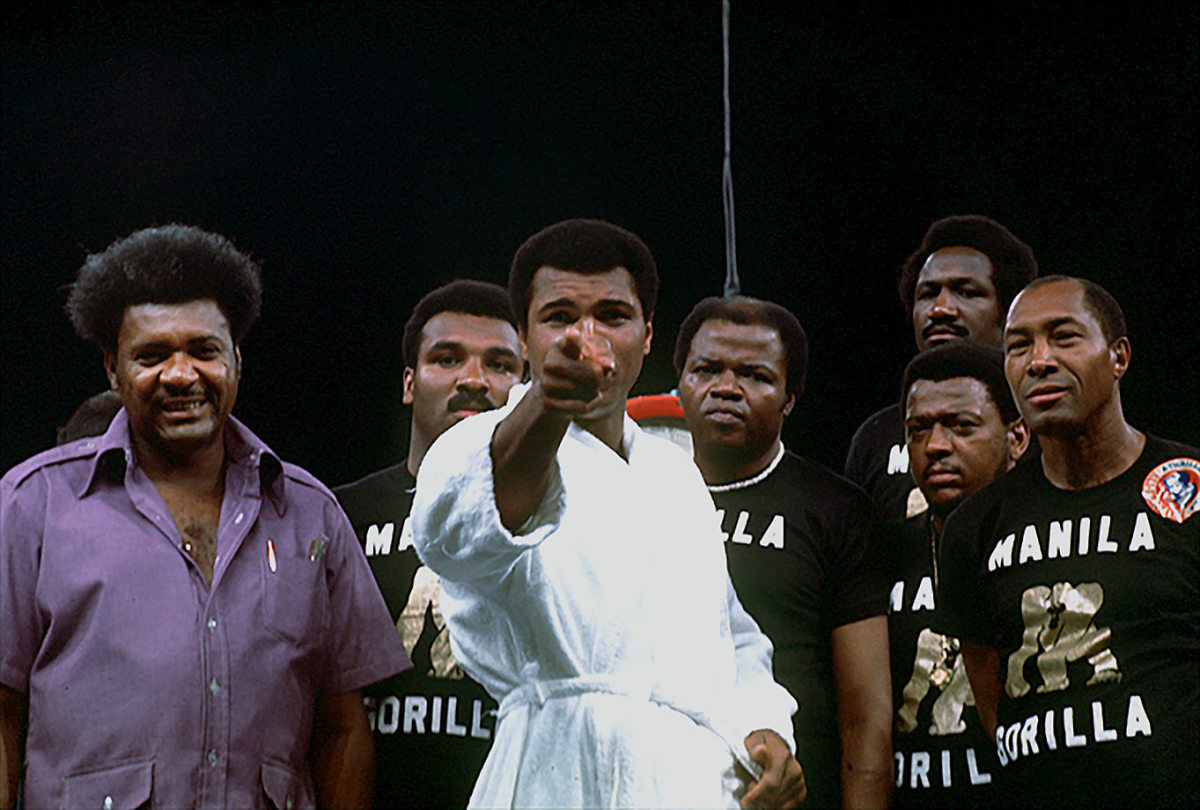

Ali points at the camera with Don King and his training staff behind him before the weigh-in for the Thrilla in Manila in October 1975. Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos offered to sponsor the bout and hold it in Metro Manila to divert attention from the turmoil in the country that had forced the imposition of martial law in 1972.

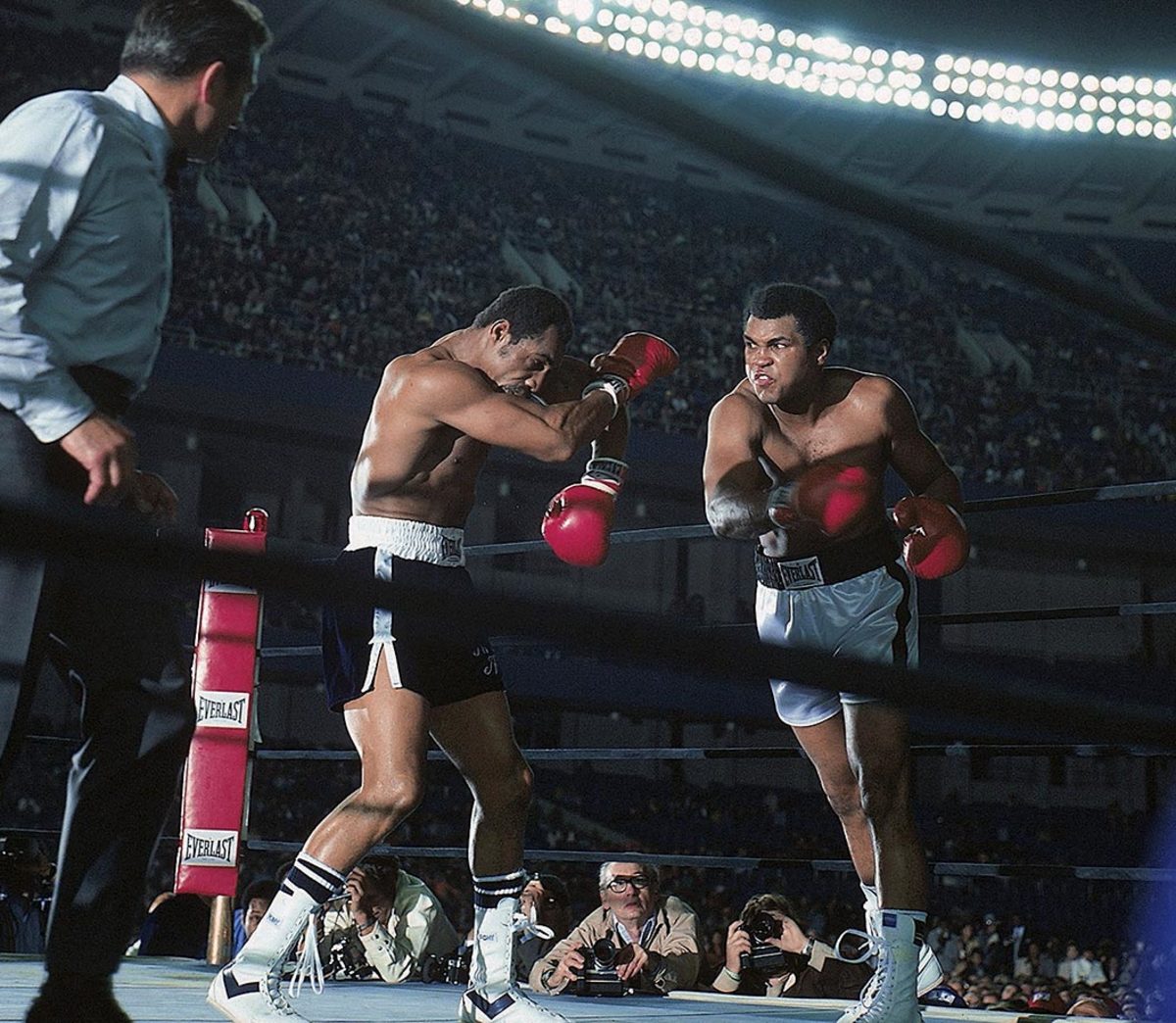

Wrapping up Joe Frazier proved more difficult than Ali expected, having thought Frazier would represent an easy payday and be unable to live up to his billing. The fight turned out to be a brutal affair.

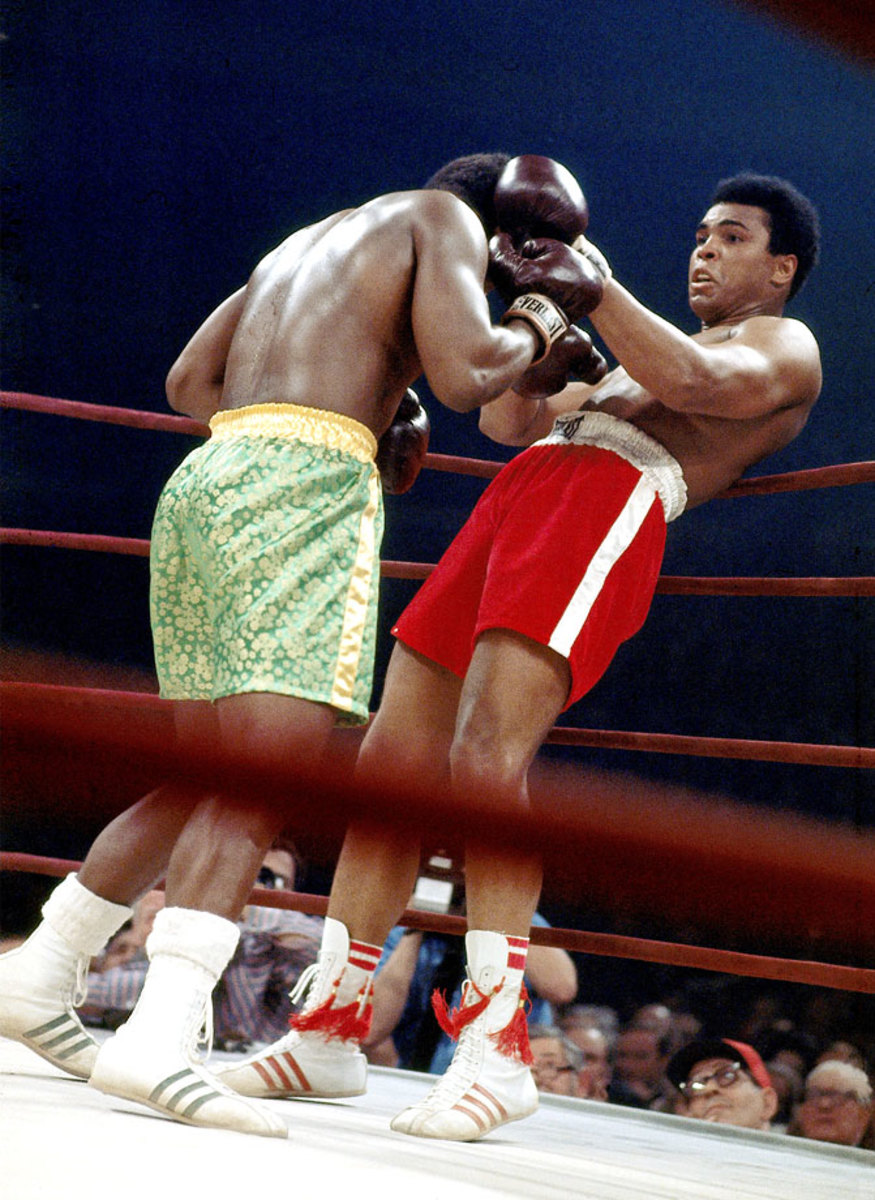

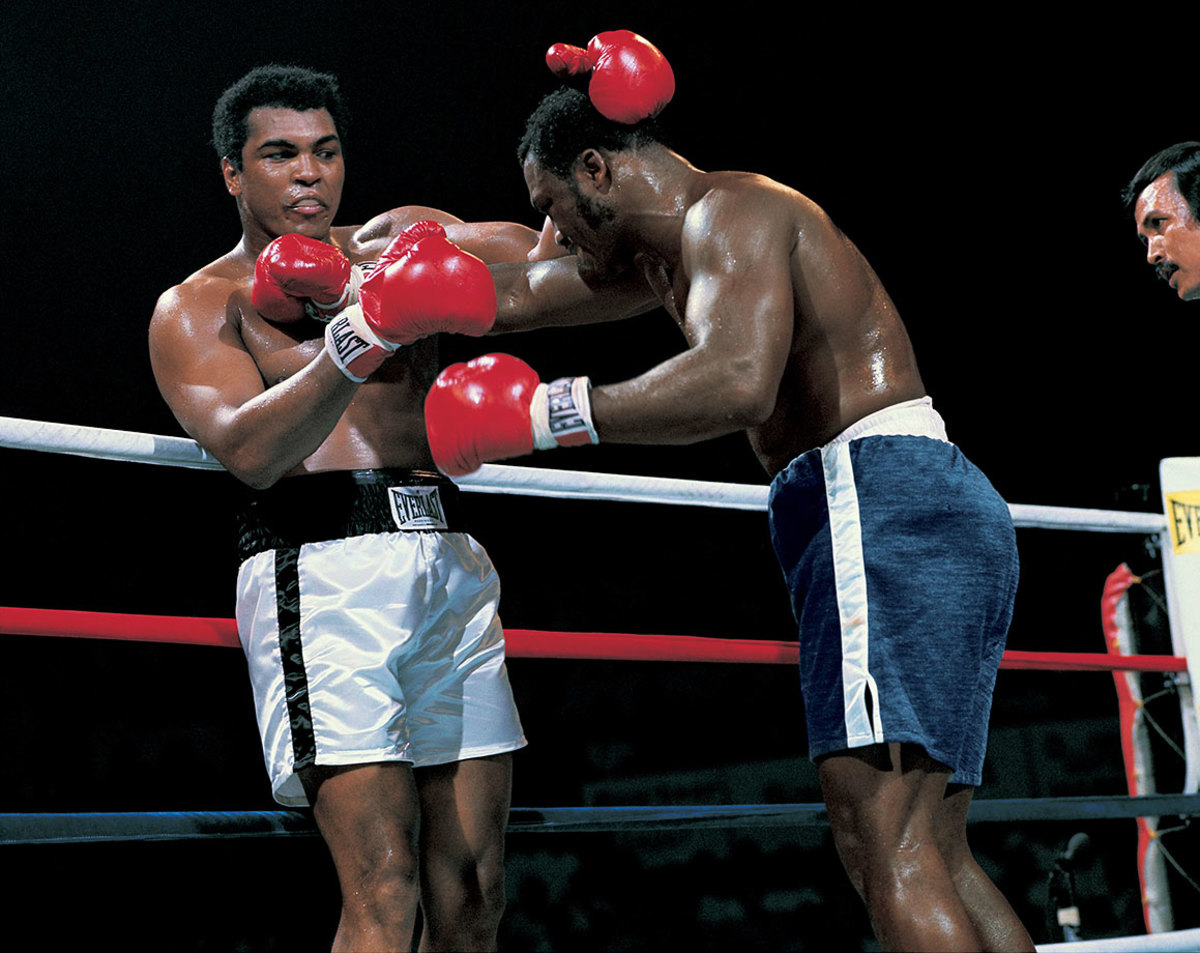

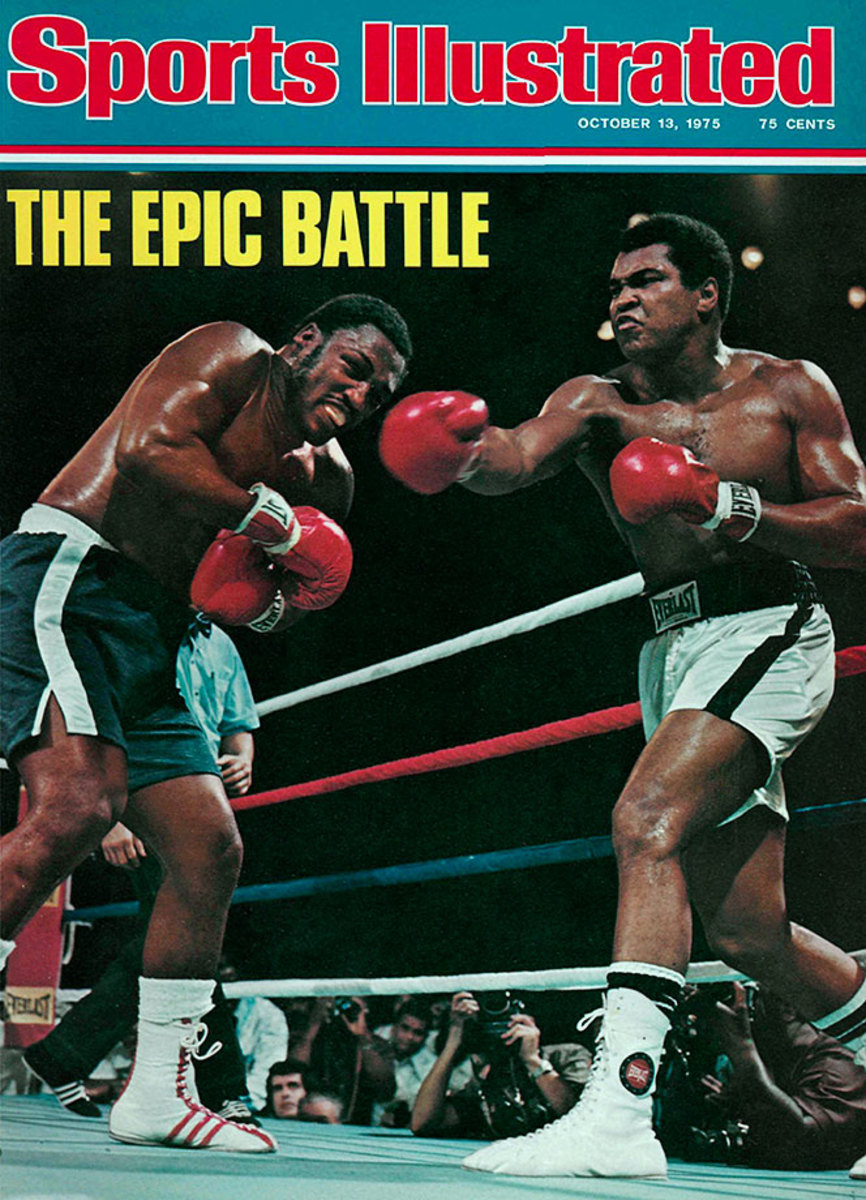

Frazier faces an Ali right hook in their fight in Quezon City, Philippines. The two fighters traded vicious blows during their 14 rounds. "Man, I hit him with punches that'd bring down the walls of a city," Frazier said. Ali withstood the blows to win by TKO in the 15th round.

The third fight between Ali and Frazier, Ali won the bruising battle between the two powerful punching heavyweights when Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, stopped the fight before the 15th round.

A back and forth exchange, Ali controlled the early rounds of the Thrilla in Manila before Frazier fought back with powerful hooks. Ali finished strong, regaining momentum in the later rounds.

Ali speaks to the press after winning the Thrilla in Manila bout with Frazier.

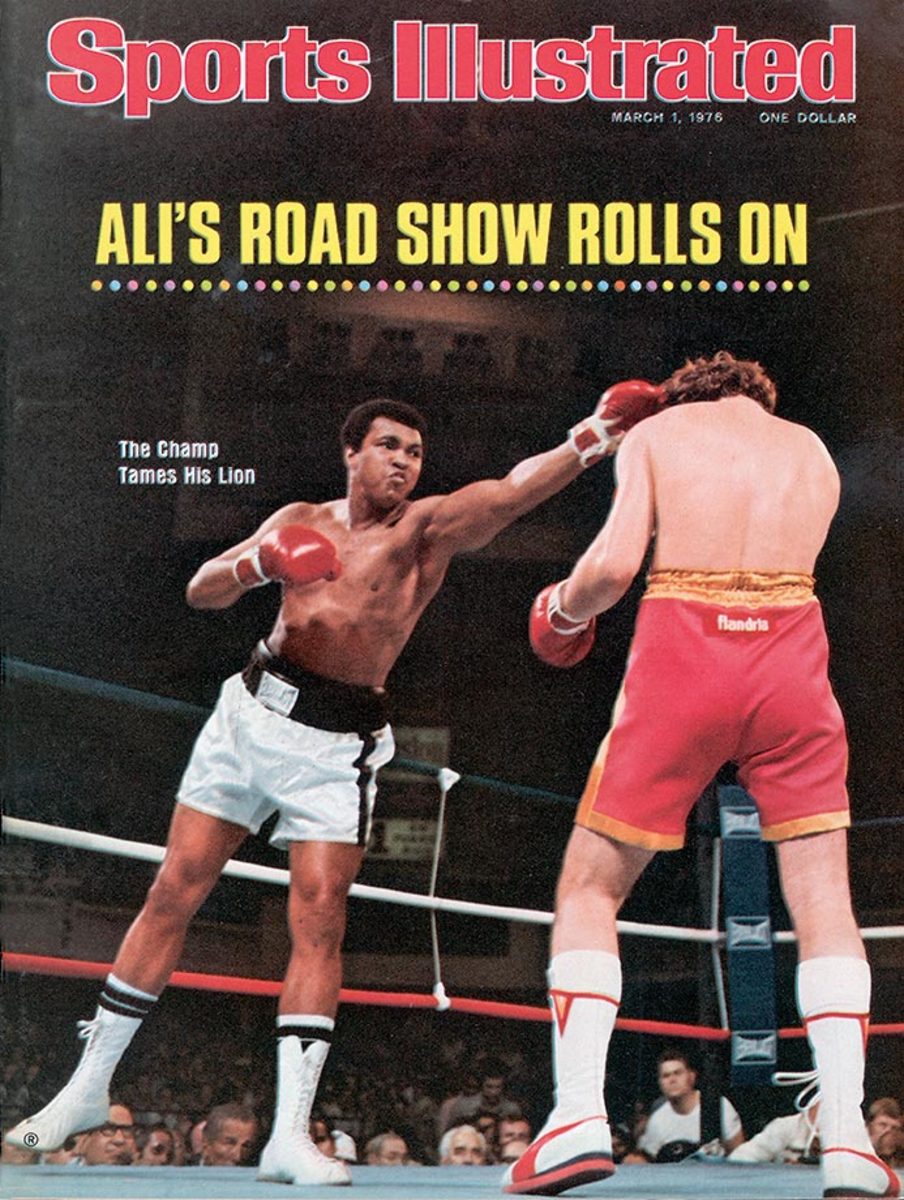

Ali holds a drinking concoction given to him by Dick Gregory, an advocate of a raw fruit and vegetable diet, in 1976.

Before his 1976 fight against Ken Norton at Yankee Stadium, Ali watches a fight on television from his hotel room. A police strike at the time of the fight created a dangerous environment outside the stadium that all but eliminated walk-up sales.

Norton takes a right hook during the heavyweight title fight against Ali. The bout, which Ali won by a unanimous, but controversial, decision, was the last boxing match at Yankee Stadium until 2010.

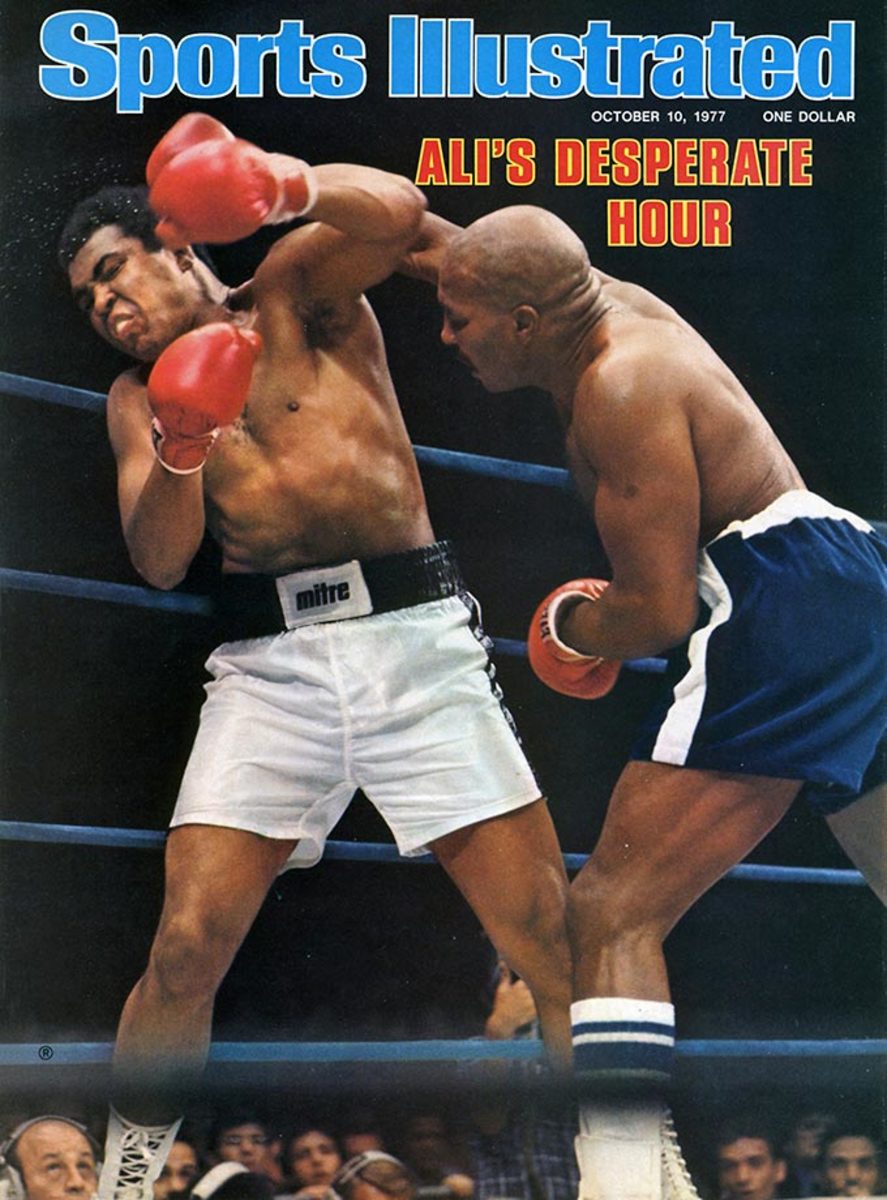

Ali makes a face during his fight with Earnie Shavers in 1977 at Madison Square Garden. Hurt badly by Shavers in the second round, Ali rebounded and outboxed Shavers throughout to build a lead on points before Shavers came on again in the later rounds. Seemingly exhausted going into the 15th and final round, Ali remained victorious by producing a closing flurry that left Shavers wobbling at the bell and the Garden crowd once again in delirium over his Ali magic.

Ali squares off with Leon Spinks at the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel in February 1978. Spinks won the fight in a split decision, ending Ali's 3.5-year reign as the heavyweight champion. It was the only time in Ali's career that he lost his championship title in the ring.

Leon Spinks took center stage over Ali at the press conference after their fight. The victorious Spinks and his gap-toothed grin were featured on the Feb. 19, 1978 cover of Sports Illustrated.

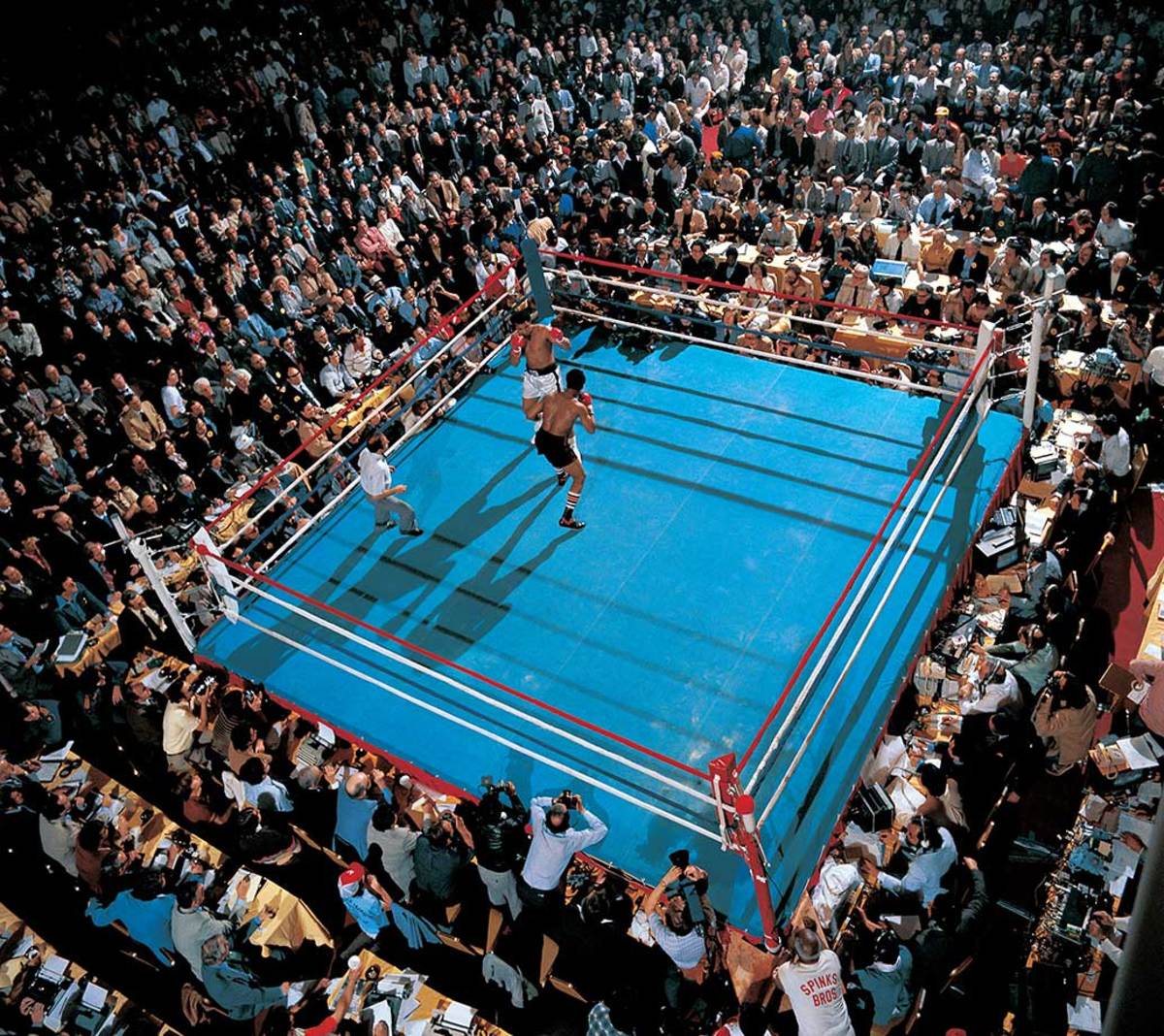

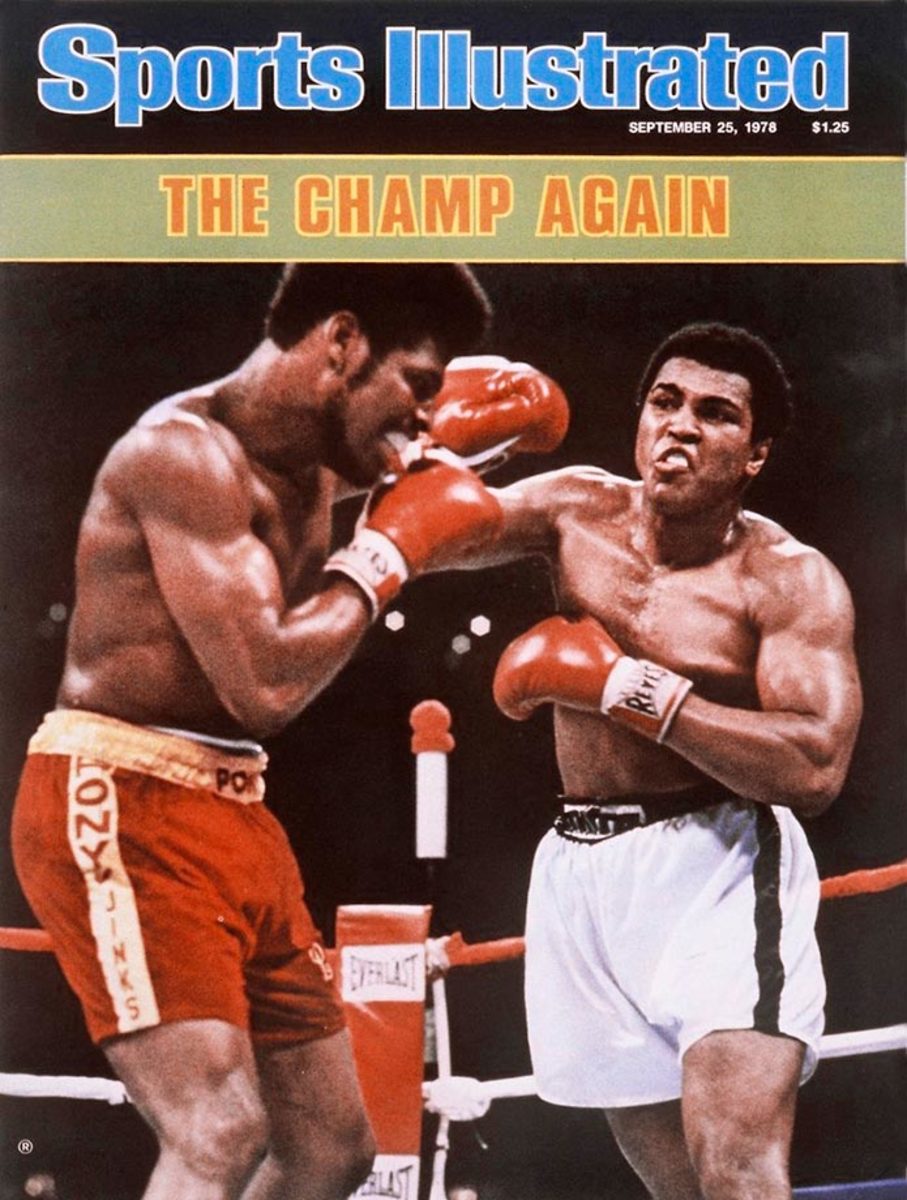

Ali lands a straight right hand to the head of Spinks in the rematch of their title bout in 1978. Ali won on a 15 round decision.

Don King pulled the strings again when Ali faced Larry Holmes before their November 1980 fight. King became a key figure in Ali's career, promoting his biggest fights, the Thrilla in Manila and the Rumble in the Jungle.

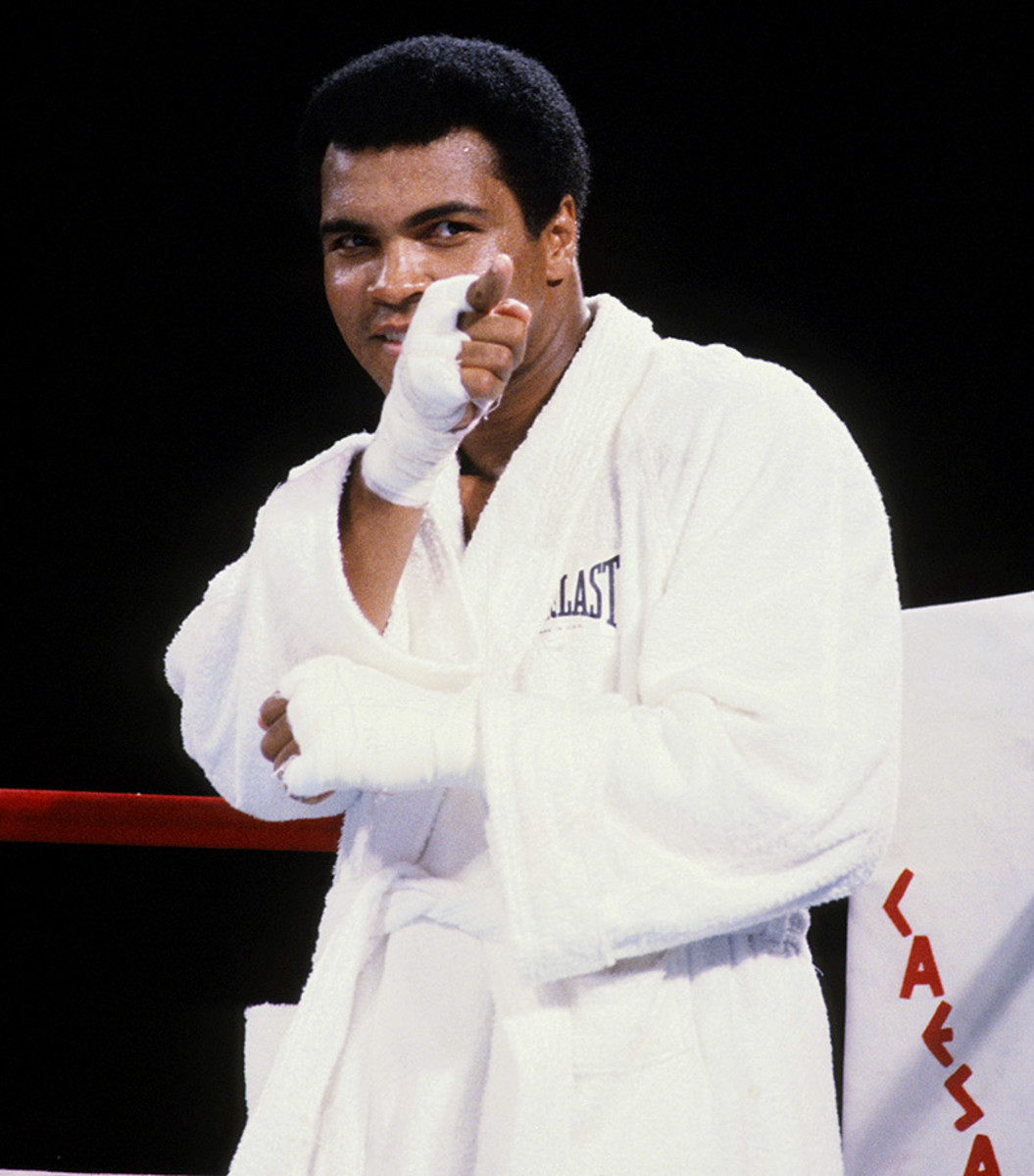

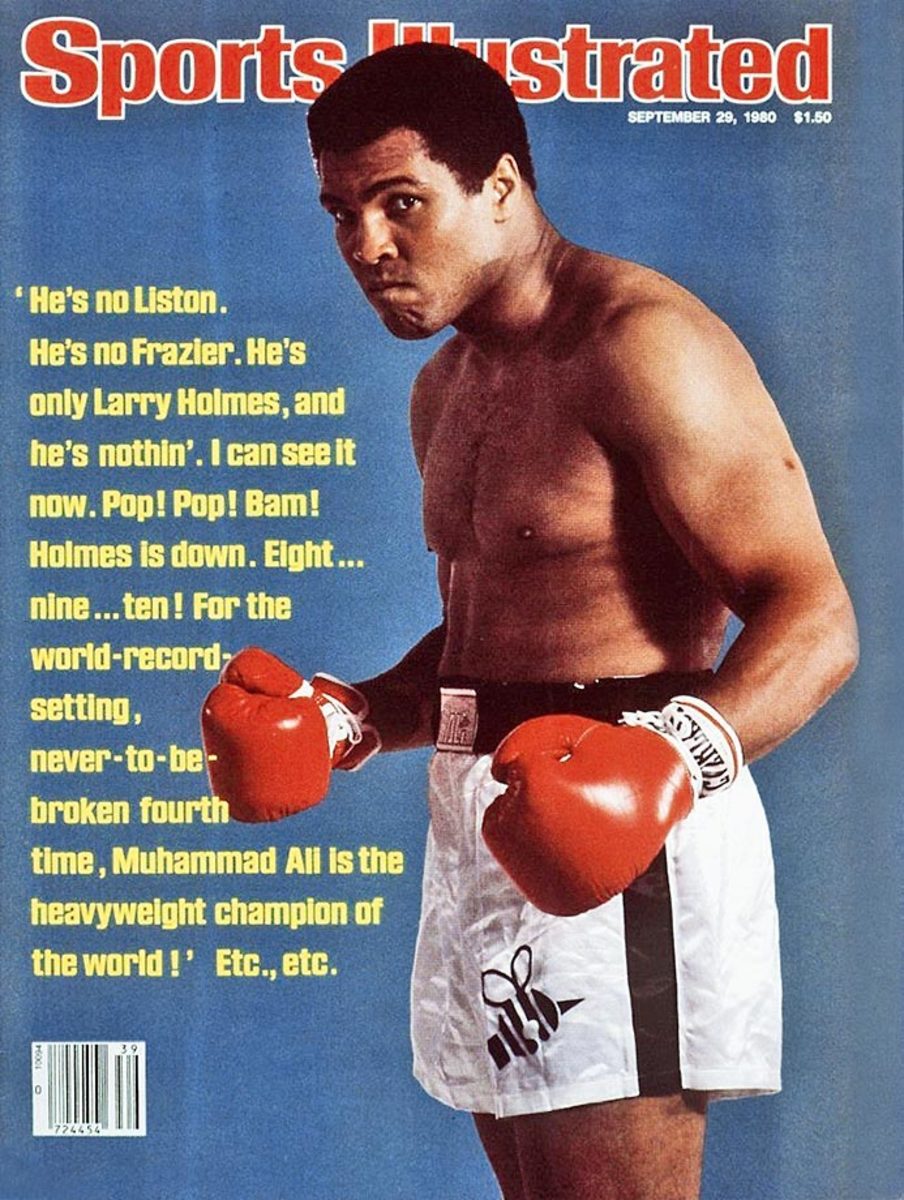

Ali points at Larry Holmes before their bout at Caesars Palace in 1980.

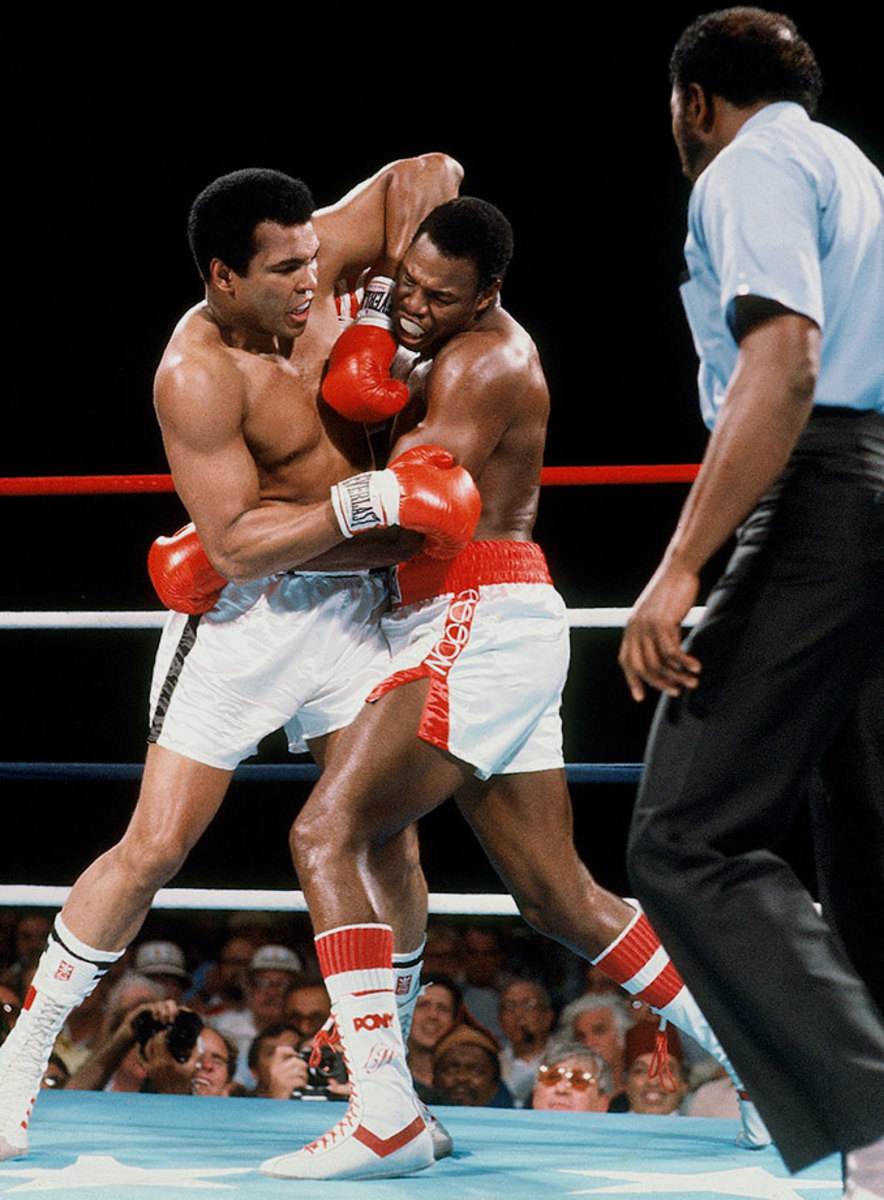

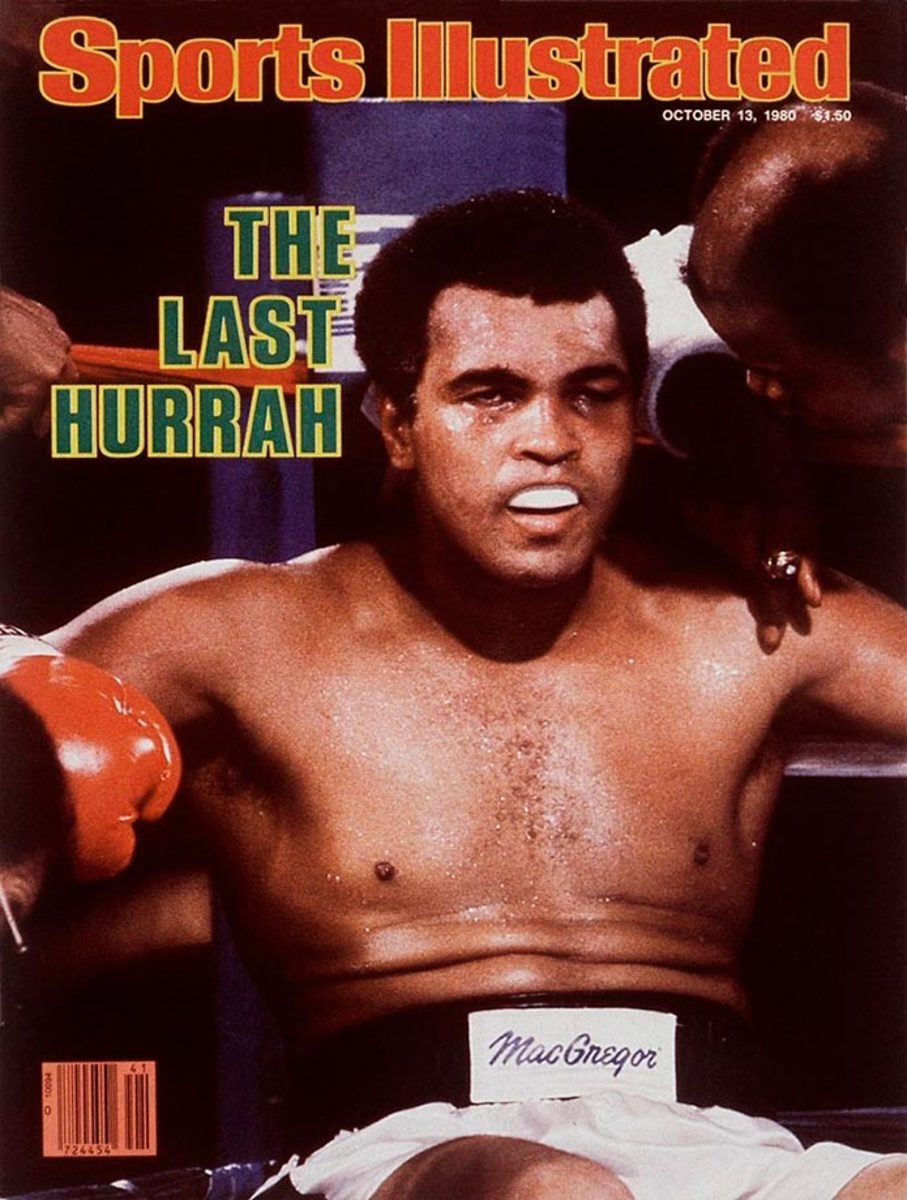

Ali grapples with Holmes during their bout in 1980. Trainer Angelo Dundee stopped the fight in the 11th round, marking the fight as Ali's only career loss by knockout.

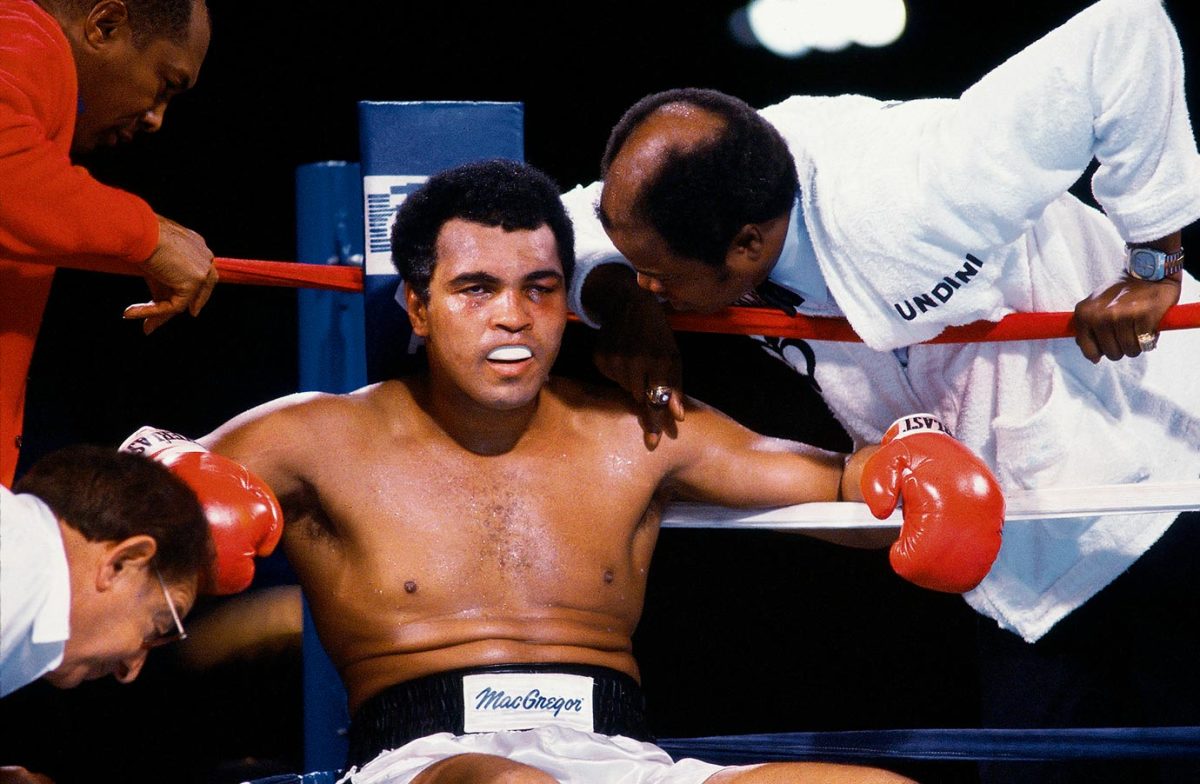

Drew Bundini Brown leans in to speak to Ali, who returned to fight Holmes after a brief retirement. By this time, Ali had already begun developing a vocal stutter and trembling hands and taken thyroid medication to lose weight that left him tired and short of breath.

Ignoring pleas for his retirement, Ali stretches before a fight against Trevor Berbick in Nassau, Bahamas. Ali lost to Berbick in a unanimous decision and retired after the bout, the 61st of his career.

Ali pretends to spar with artist LeRoy Neiman at his home in Los Angeles. Neiman met Ali in 1962 and made many paintings and sketches from throughout Ali's life.

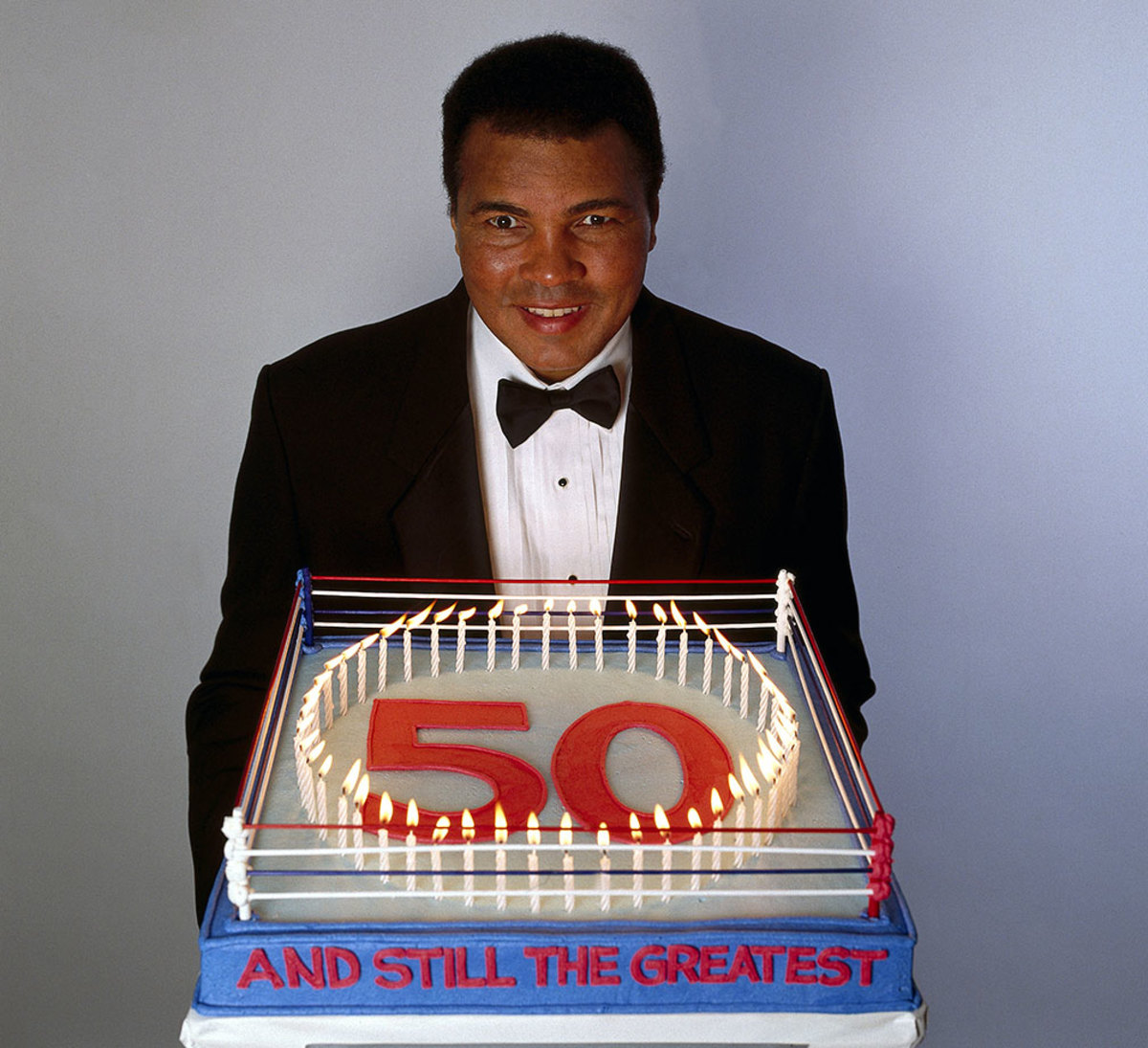

Cake in hand, Ali poses for a 50th birthday portrait in 1991. Although diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome seven years earlier, Ali was still active, traveling to Iraq during the Gulf War to meet with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages.

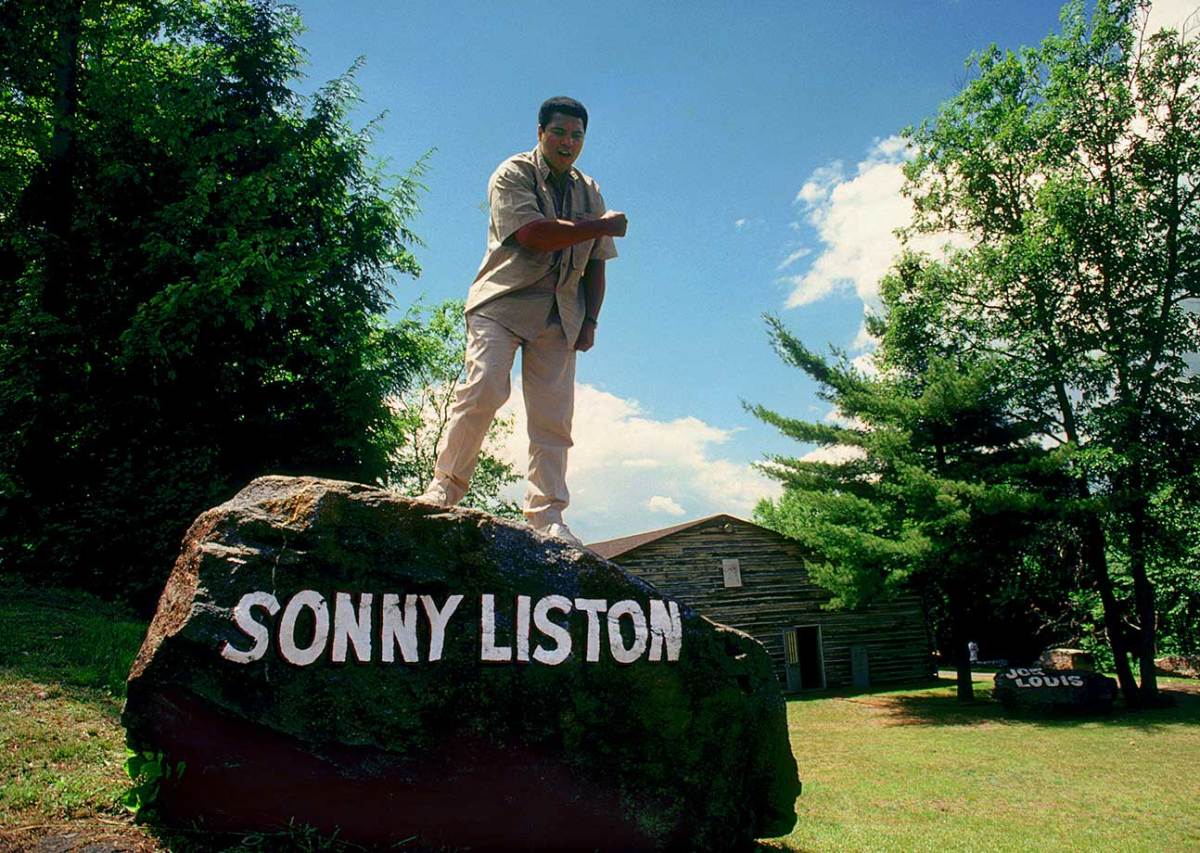

The same year, Ali stands atop of the Sonny Liston rock at his old training camp cabin. Ali and his father painted the names of famous boxers he admired on 18 boulders at the camp.

Ali carries the Olympic torch inside Centennial Olympic Stadium at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Despite trembling hands, Ali had the honor to light the Olympic flame in the stadium.

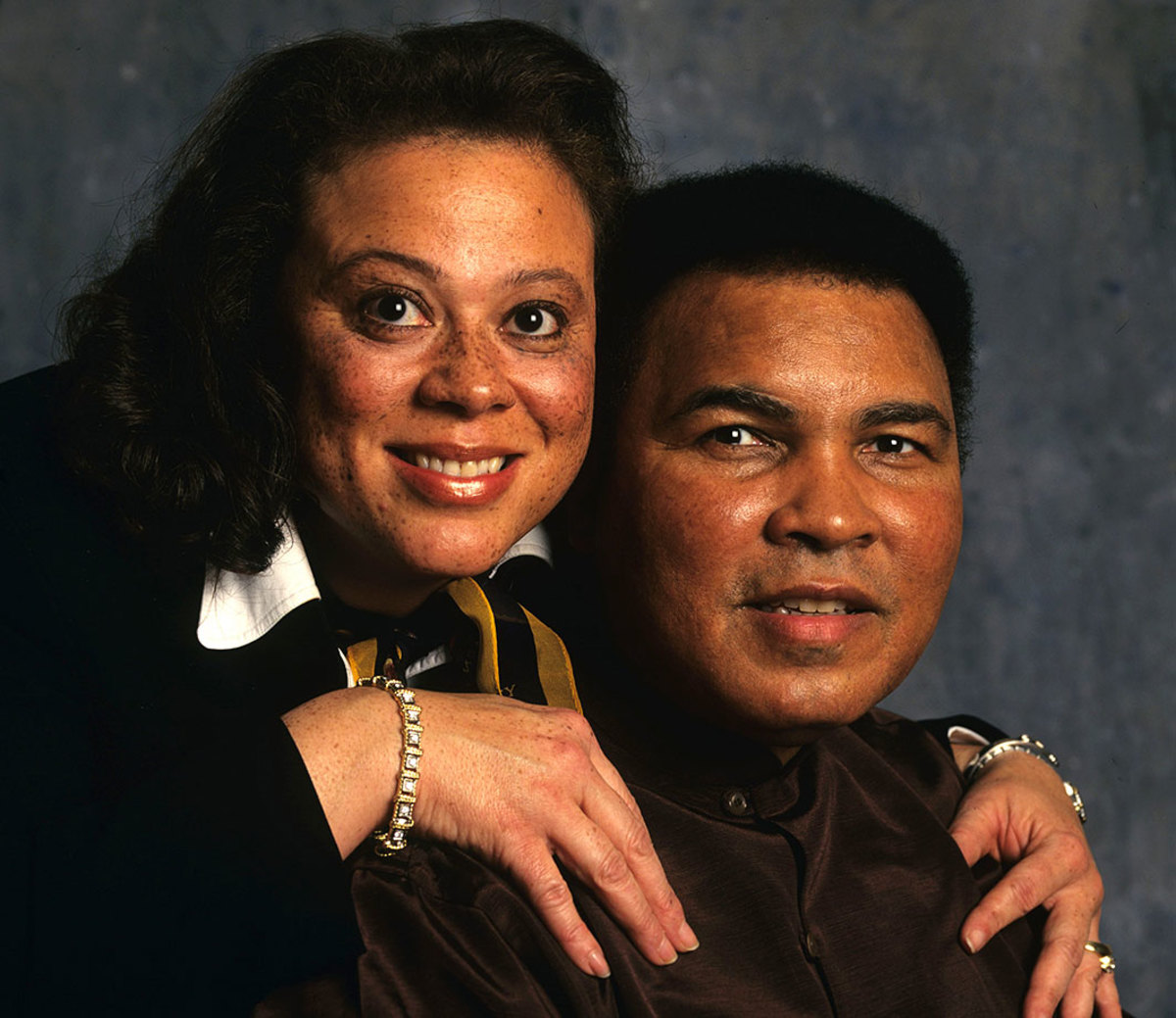

Husband and wife pose for a portrait during a photo shoot in 1997. Muhammad and Lonnie married in 1986 and have an adopted son together, Asaad Amin Ali.

Ali messes around with actor Billy Crystal during a photo shoot in 2000. Crystal's impression of Ali was notorious, and he performed at a tribute to the boxer on his 50th birthday in December 1991.

Ali lies on the canvas as his son, Assad Amin Ali, stands over him invoking memories of Ali's victory over Sonny Liston during a photo shoot in the gym at his farm on Kephart Road near Berrien Springs in 2001.

Fierce rivals in the ring, Ali and Joe Frazier pose for a portrait in the boxing robes they wore the night of their first bout at Frazier's Gym in 2003. Ali said after Frazier's death in 2011 that he was "a great champion."

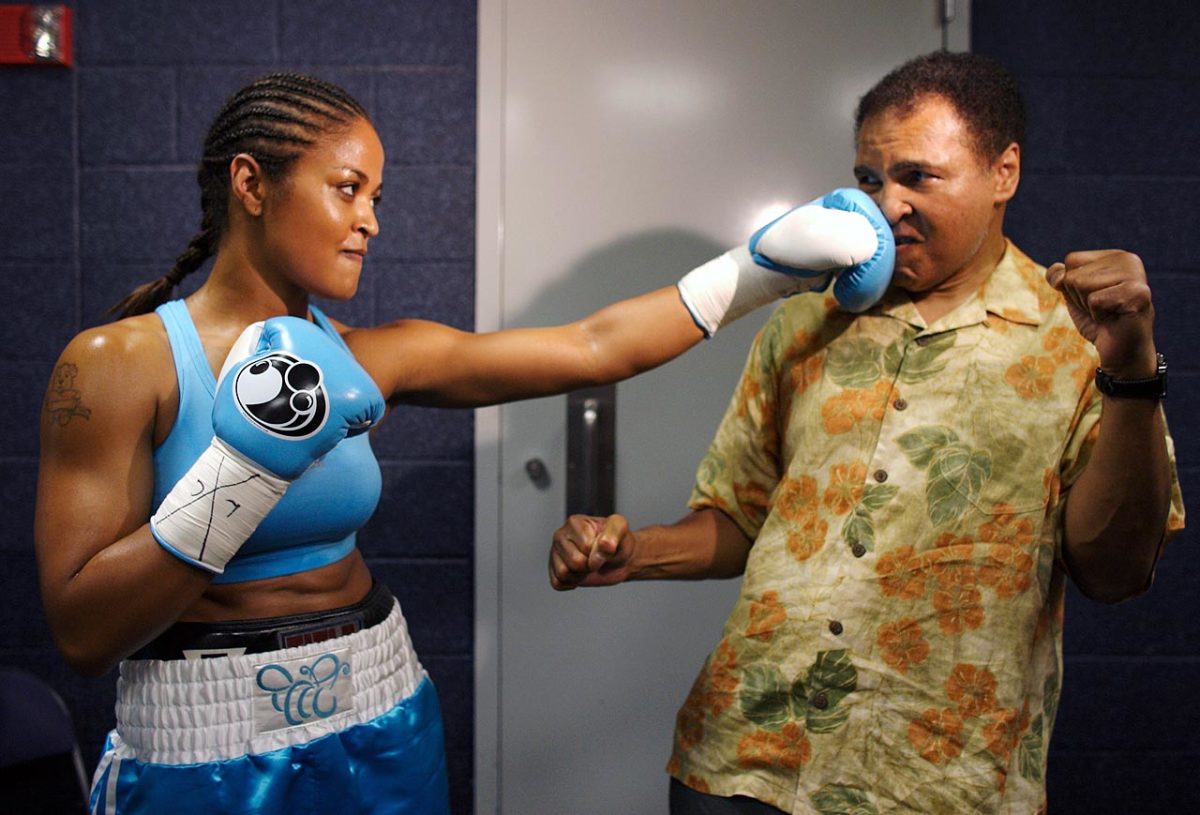

Ali takes a punch from his daughter Laila Ali while sparring before her fight against Erin Toughill in 2005. Laila retired from her own successful boxing career with a professional record of 24-0.

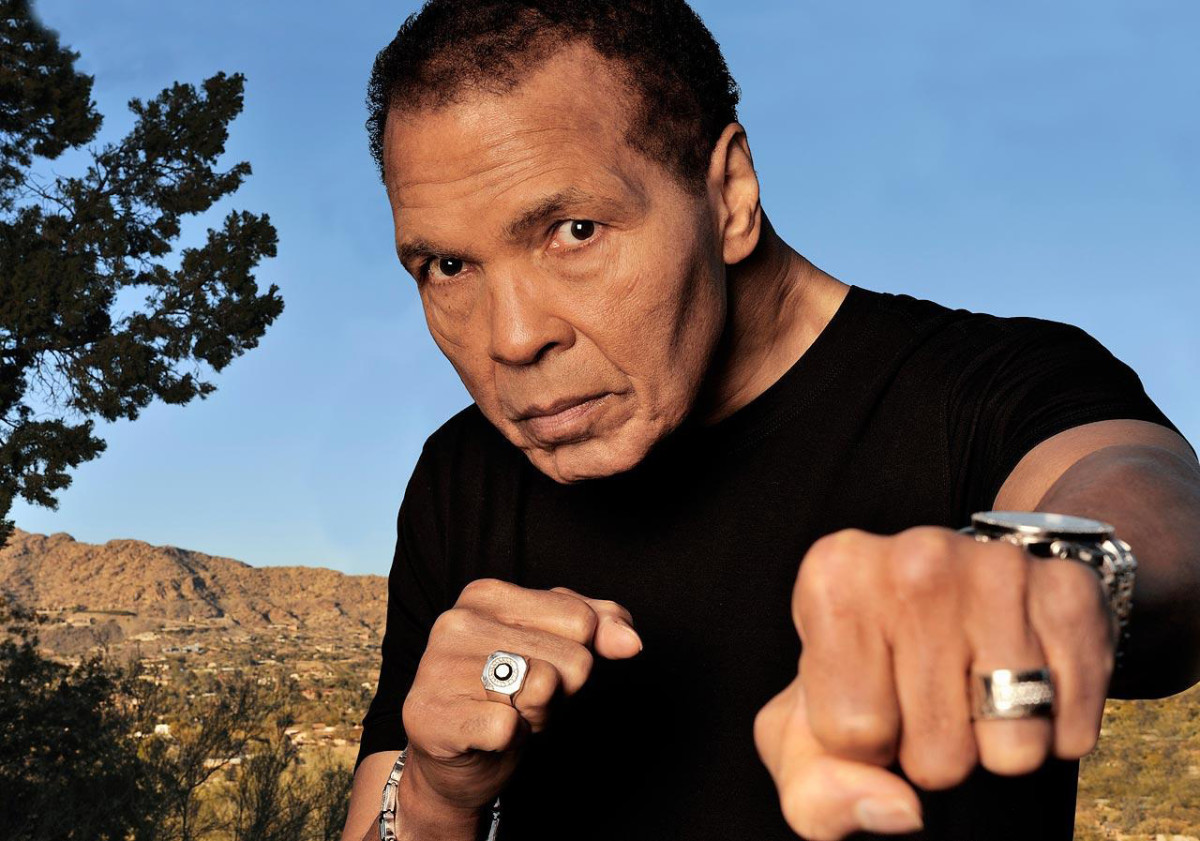

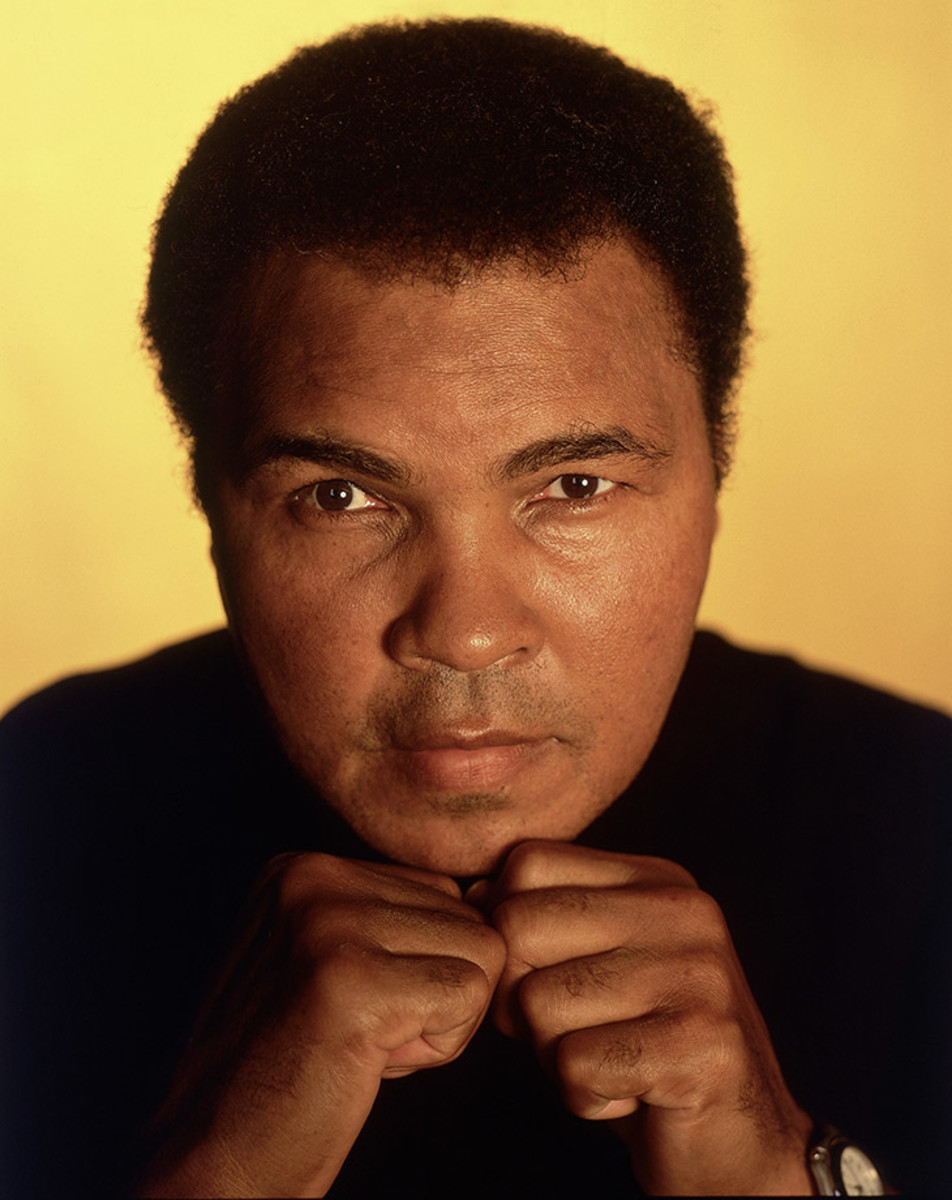

Ali poses with his fists up for a portrait in 2005.

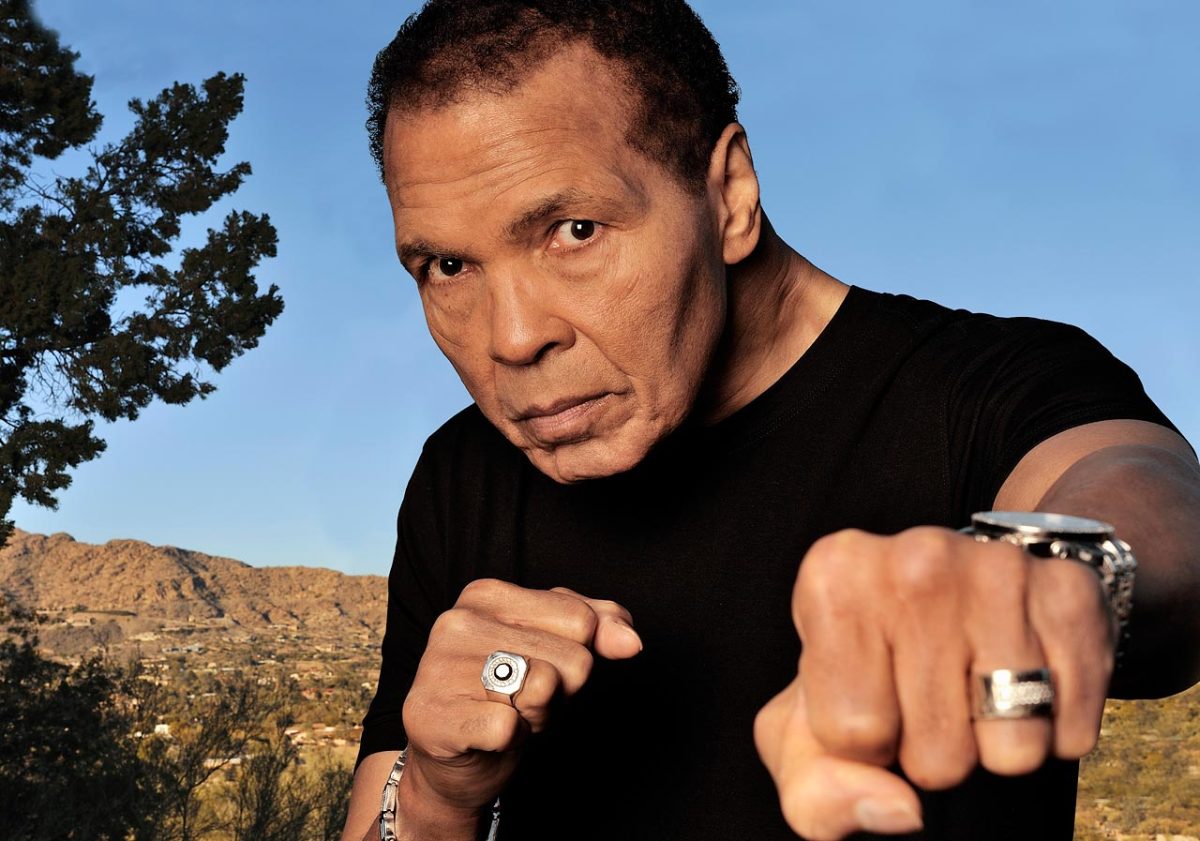

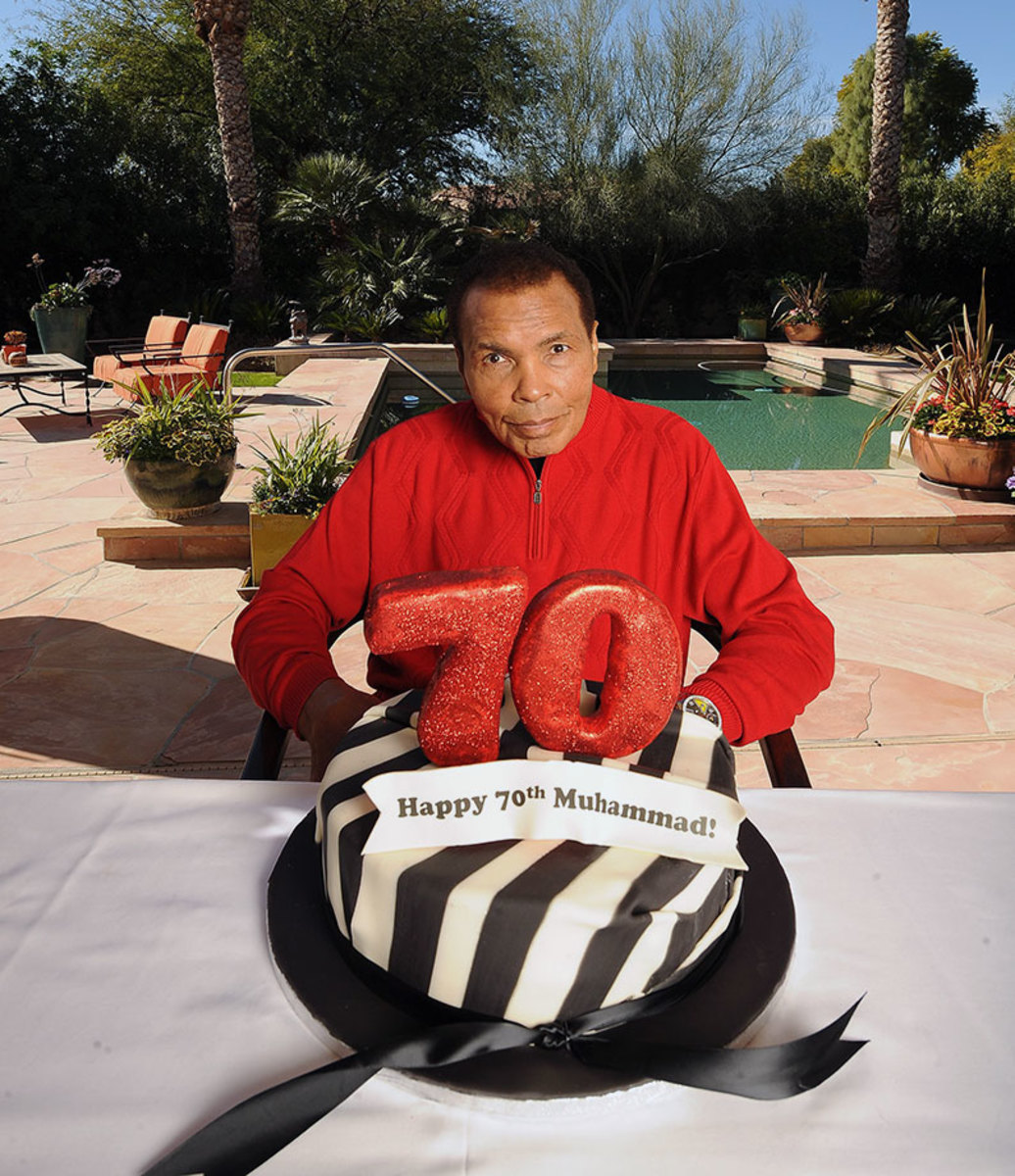

Ali poses with an extended punch in a 2012 photo shoot at his home in Paradise Valley, Ariz., to mark his 70th birthday.

Ali sits in front of a 70th birthday cake in January 2012 at his Arizona home. Later that year he appeared at the opening ceremonies for the 2012 Olympics in London to escort the Olympic flag into the stadium, 52 years after he won gold in Rome.

The trick to seeing him as he really was would be to bring back everyone. Set the people up again in the present tense. Have them return to where everything happened. Let them walk and talk their way through the same troubles. Live everything again.

For a stretch of time, five years, 1966 through 1971, the most turbulent, divided stretch of this nation’s history outside the Civil War, Muhammad Ali was discussed as much as anyone who walked on the planet. He was part of arguments about race, religion, politics, war, and peace. Not to mention boxing. It was an unmatchable story.

Here was this kid, this athletic prodigy, who fell into the thrall of an offbeat religion, the Nation of Islam, not the Islam known around the world, the Nation of Islam, a racially based cult as curious as the Hare Krishnas, as suspicious as the Moonies or the Scientologists or any other group that rings your doorbell, ding-dong, and promises salvation as if it were as easy to purchase as a vacuum cleaner with three monthly payments. He fell for it, foolish and proud, young and impressionable, and he wound up in everyone’s house. Ding-dong. Every house in the world. Pretty much illiterate, he was supremely good-looking and supremely verbal at a time when television invaded everywhere and these qualities became more important. He could fight in a boxing ring in a way no one ever had seen, talk in an excited way no one really had heard.

He was part boob, part rube, part precocious genius, boom, somewhat honorable, and could be really funny.

Five years.

He stumbled into his situation, said he didn’t want to go to war because of his religion, put one foot in front of another, and came out the other end a hero. Controversy found him and surrounded him. He fought the U.S. government, history, a Gallup poll majority of the American public, and Joe Frazier. He somehow survived.

Five years.

Muhammad Ali's SI Covers

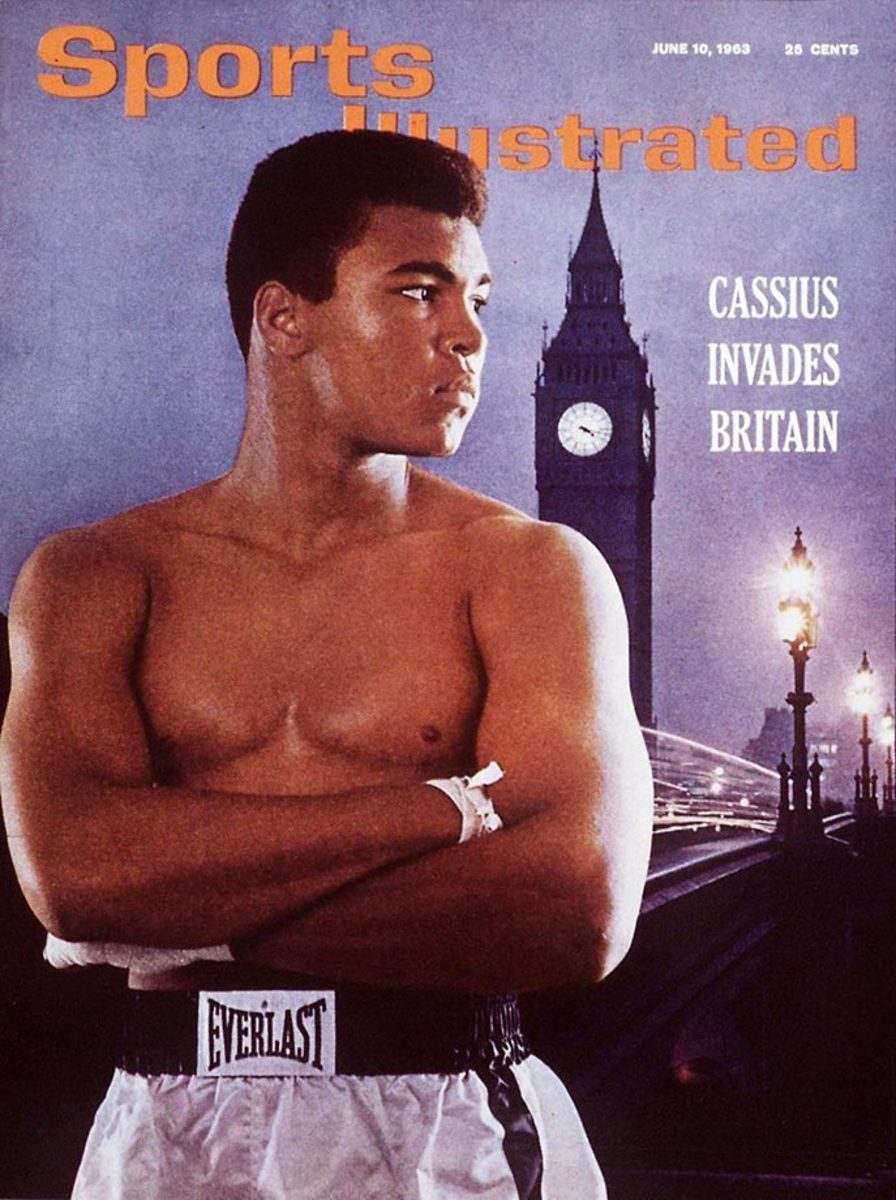

June 10, 1963

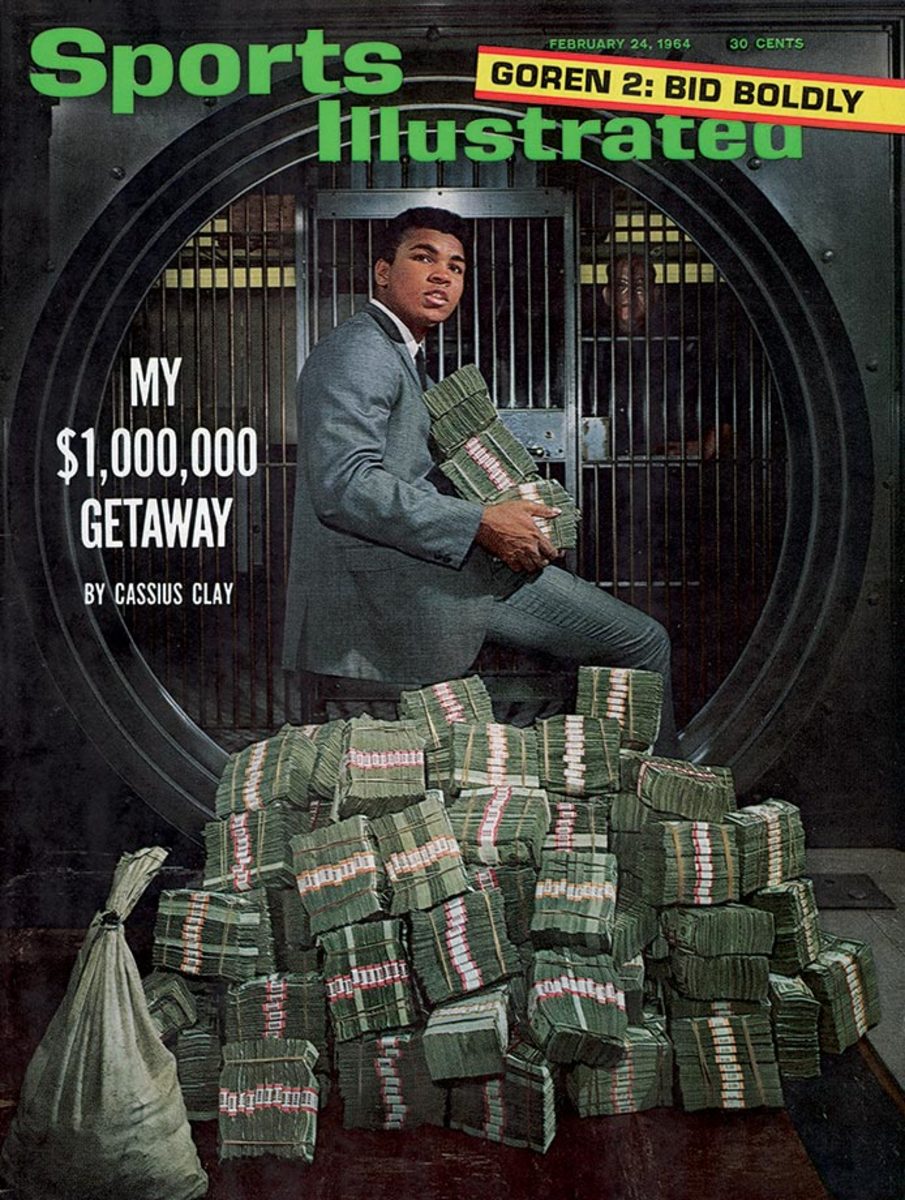

February 24, 1964

March 9, 1964

November 16, 1964

May 24, 1965

June 7, 1965

November 22, 1965

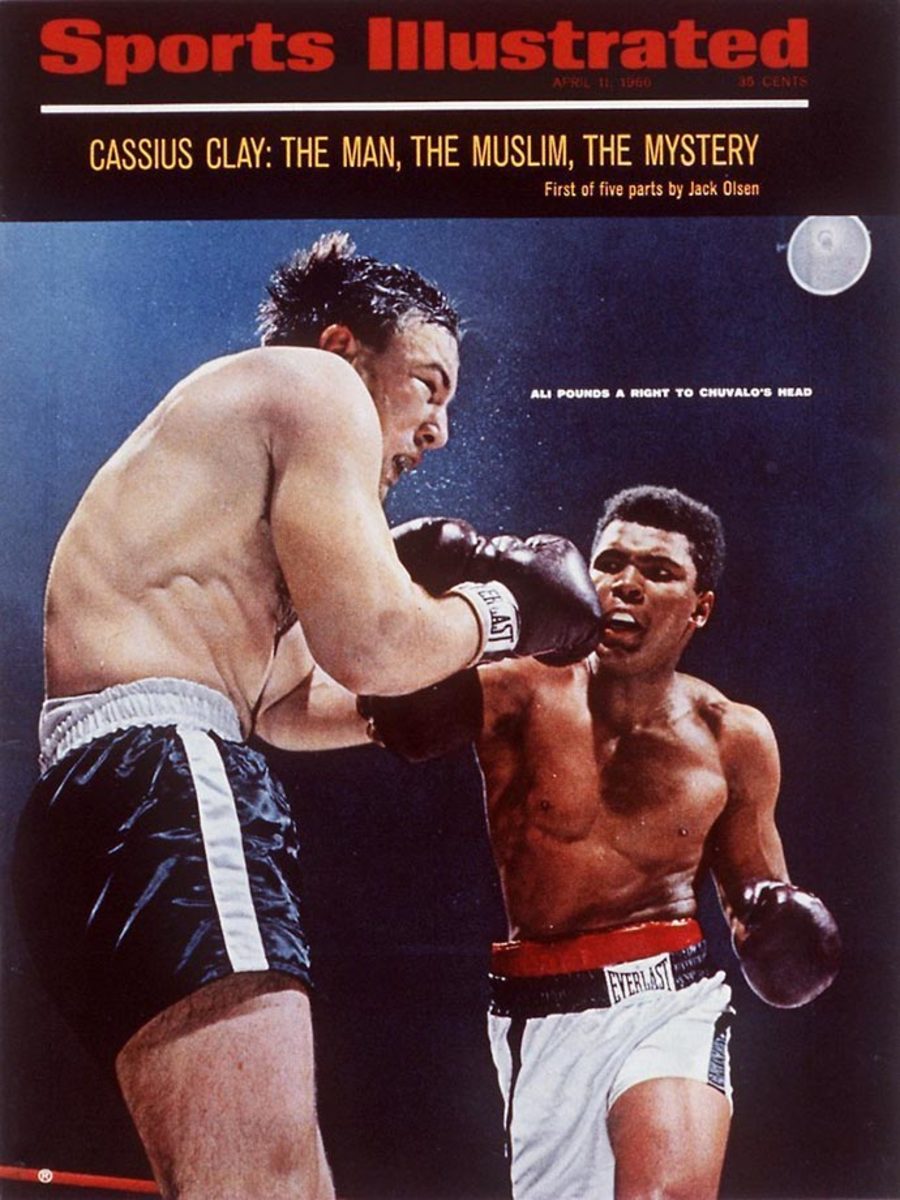

April 11, 1966

February 6, 1967

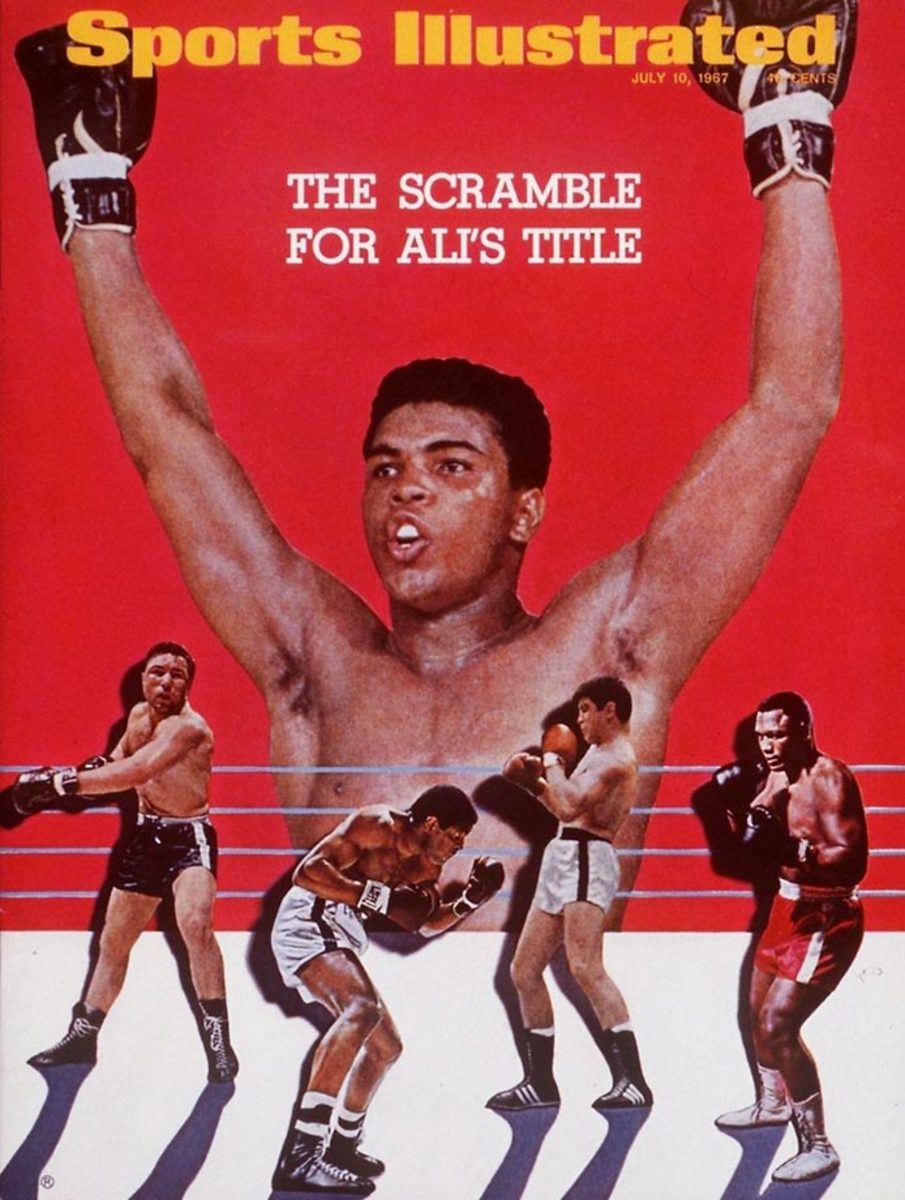

July 10, 1967

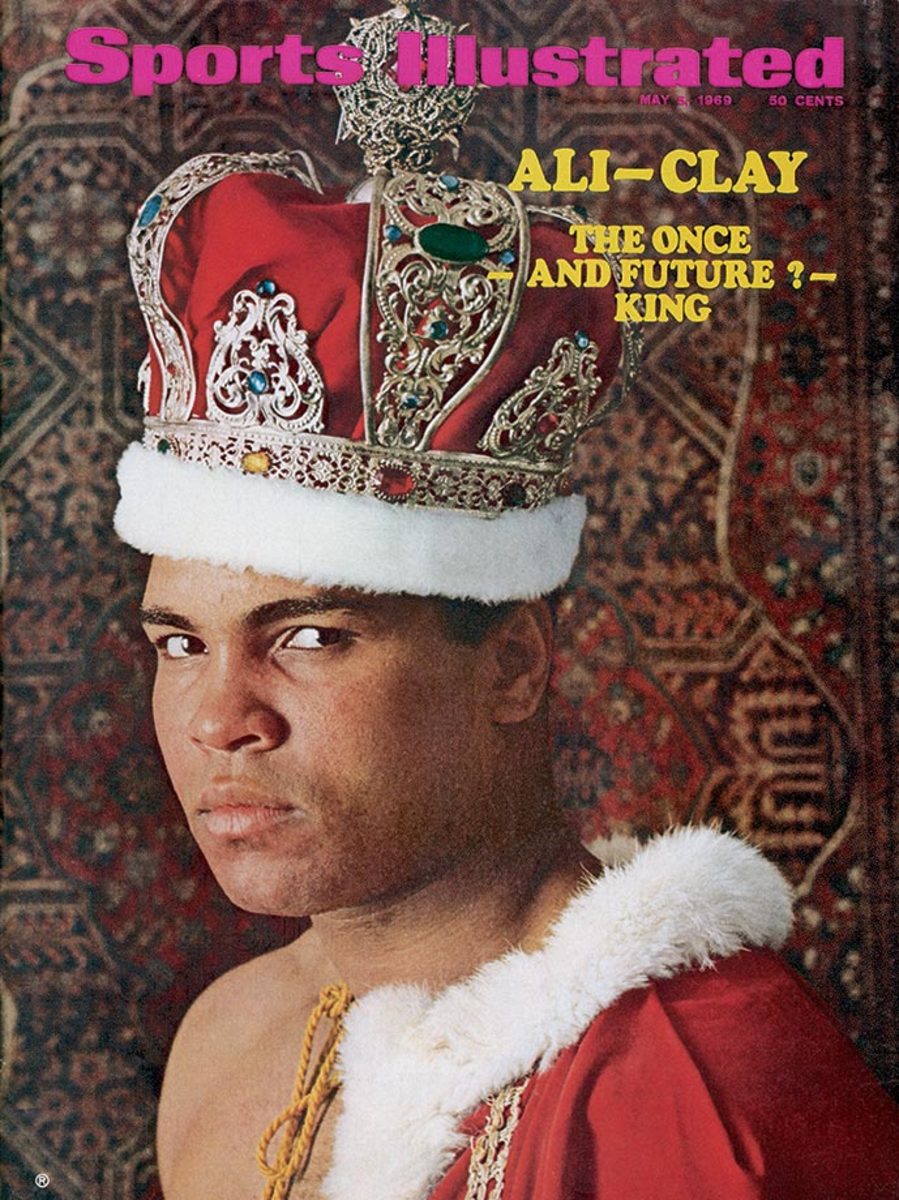

May 5, 1969

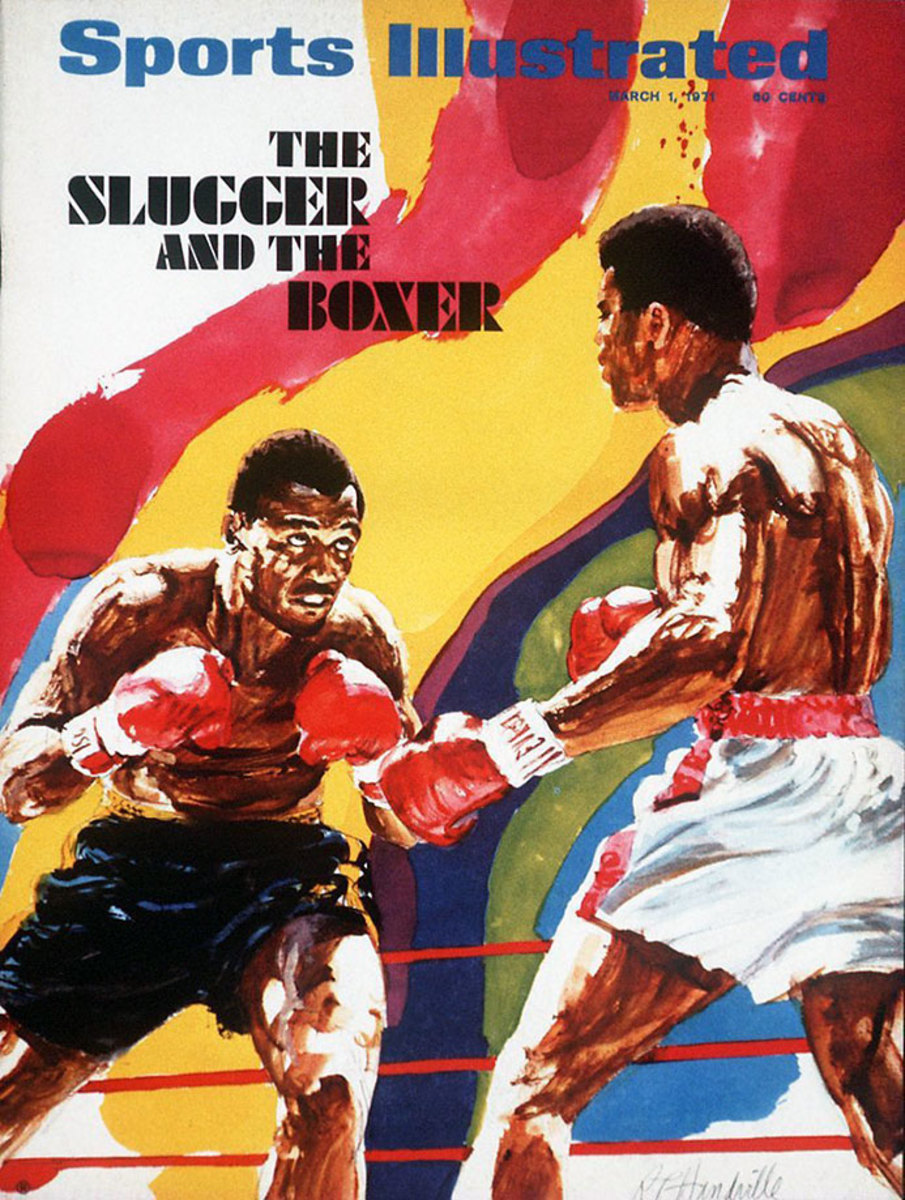

March 1, 1971

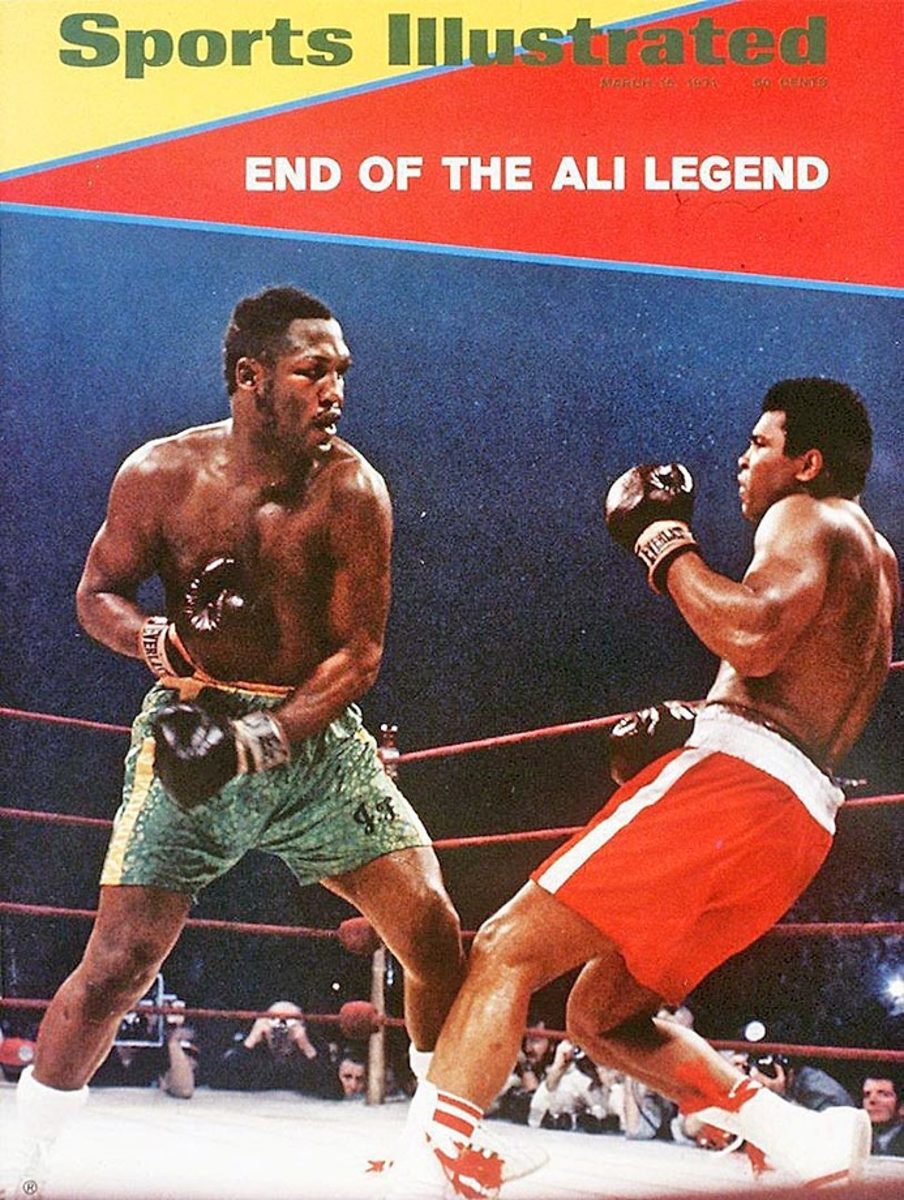

March 15, 1971

July 26, 1971

April 23, 1973

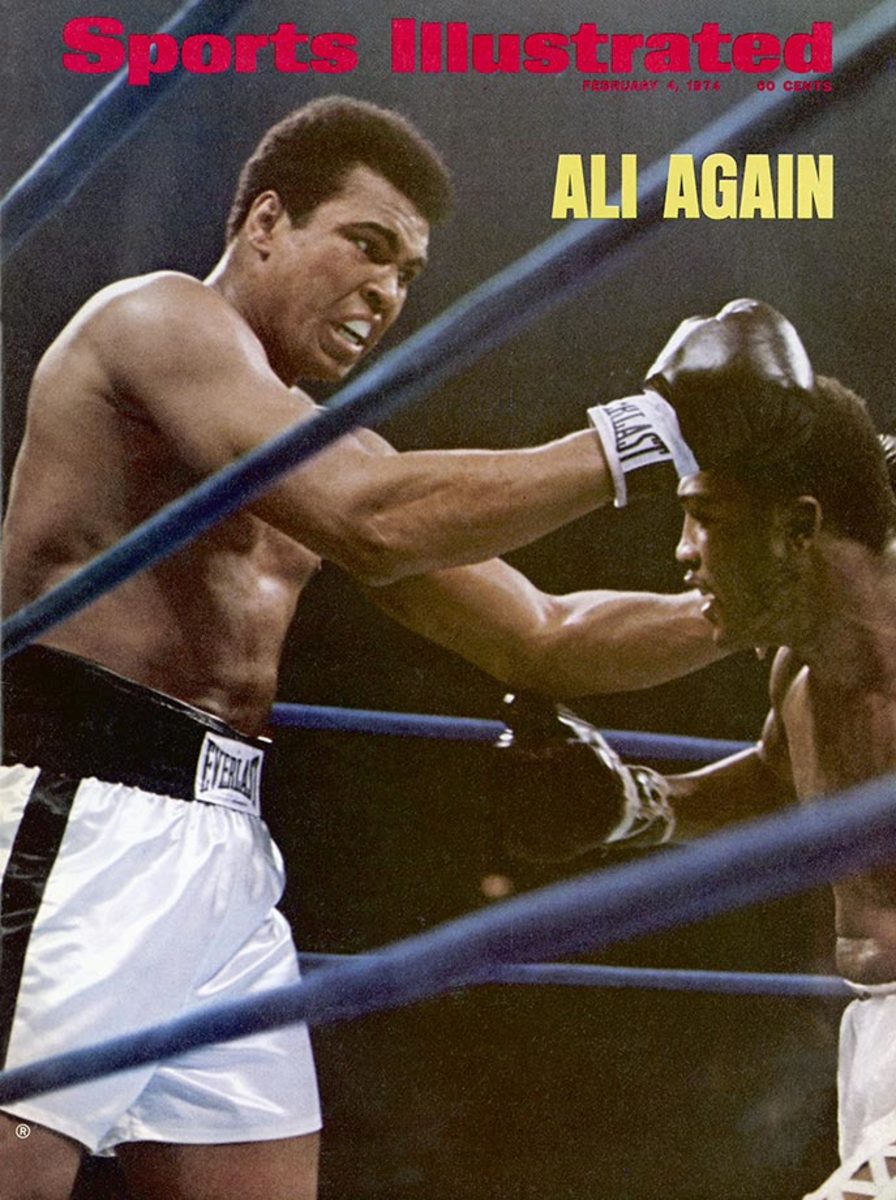

February 4, 1974

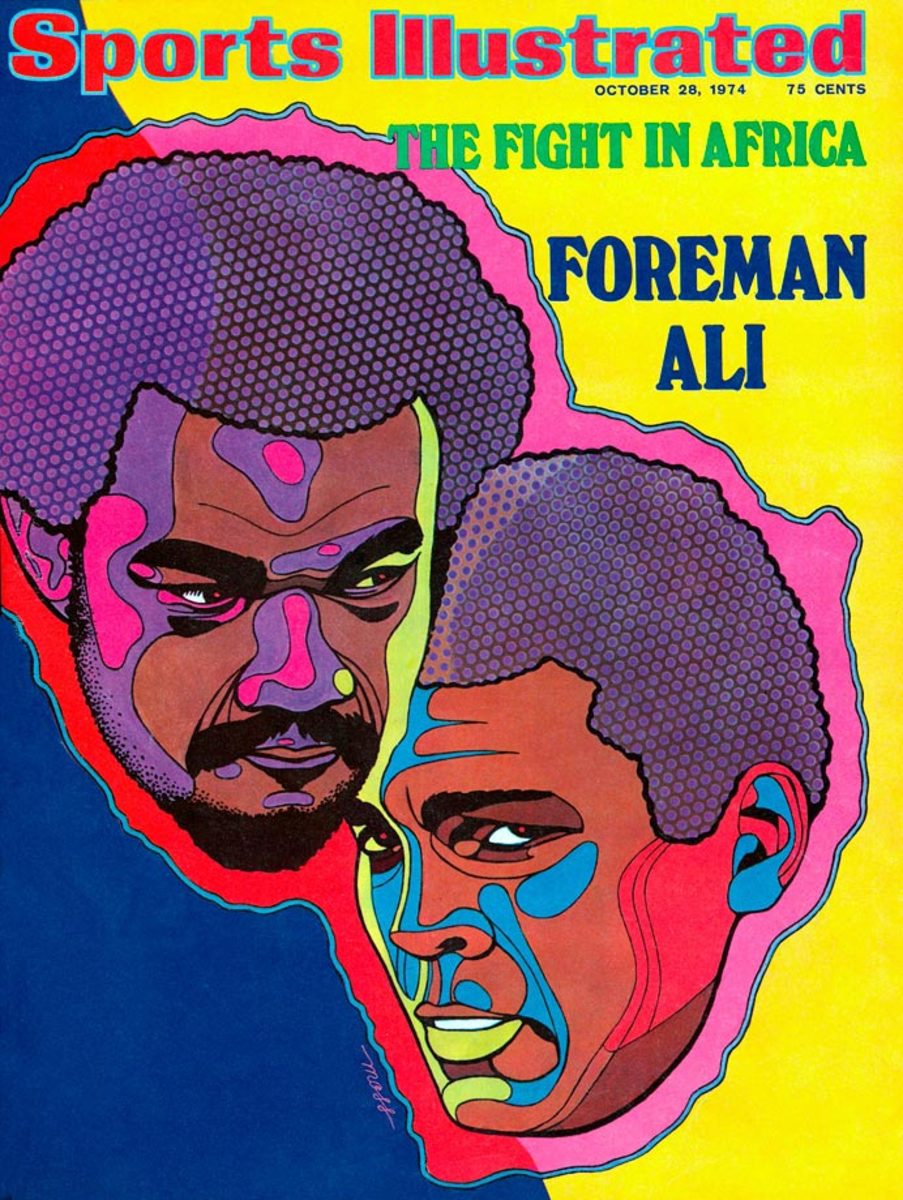

October 28, 1974

November 11, 1974

December 23, 1974

September 15, 1975

October 13, 1975

March 1, 1976

October 10, 1977

September 25, 1978

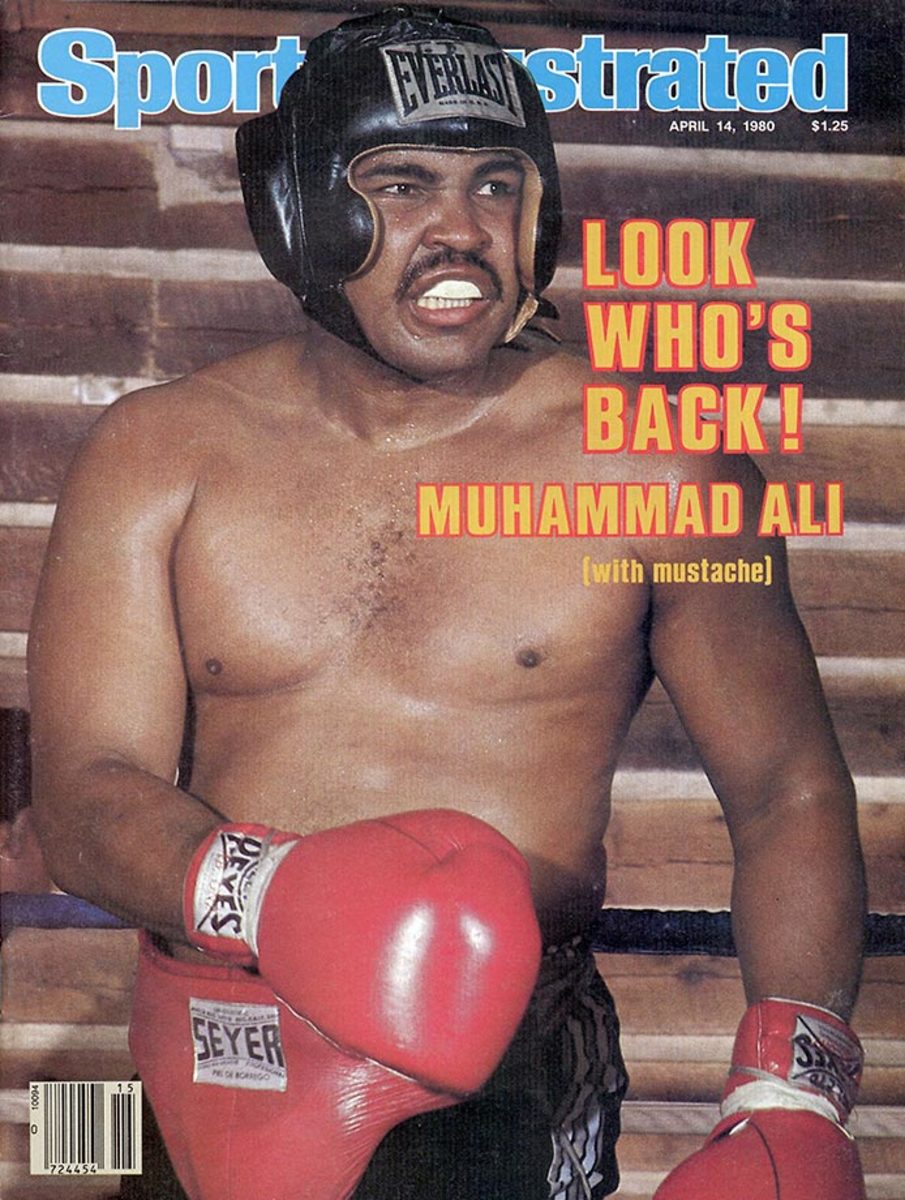

April 14, 1980

September 29, 1980

October 13, 1980

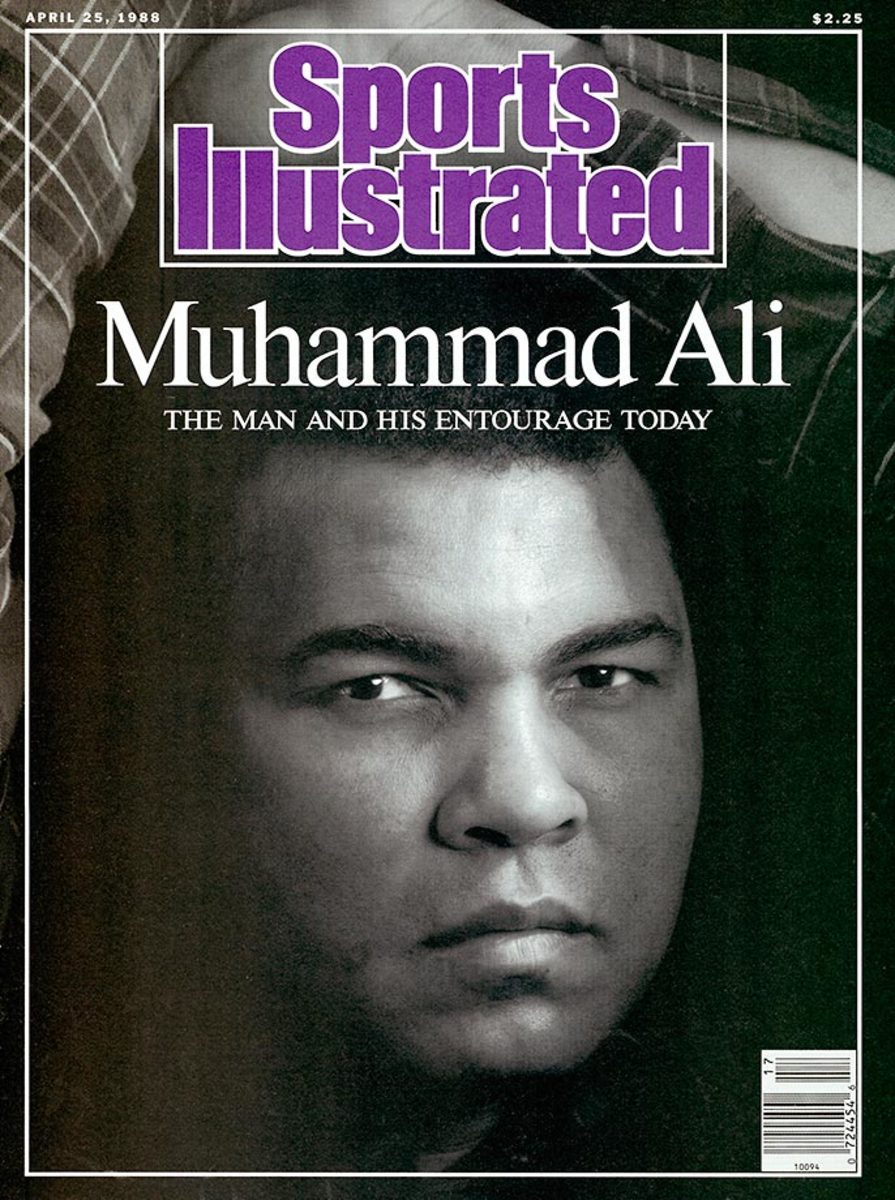

April 25, 1988

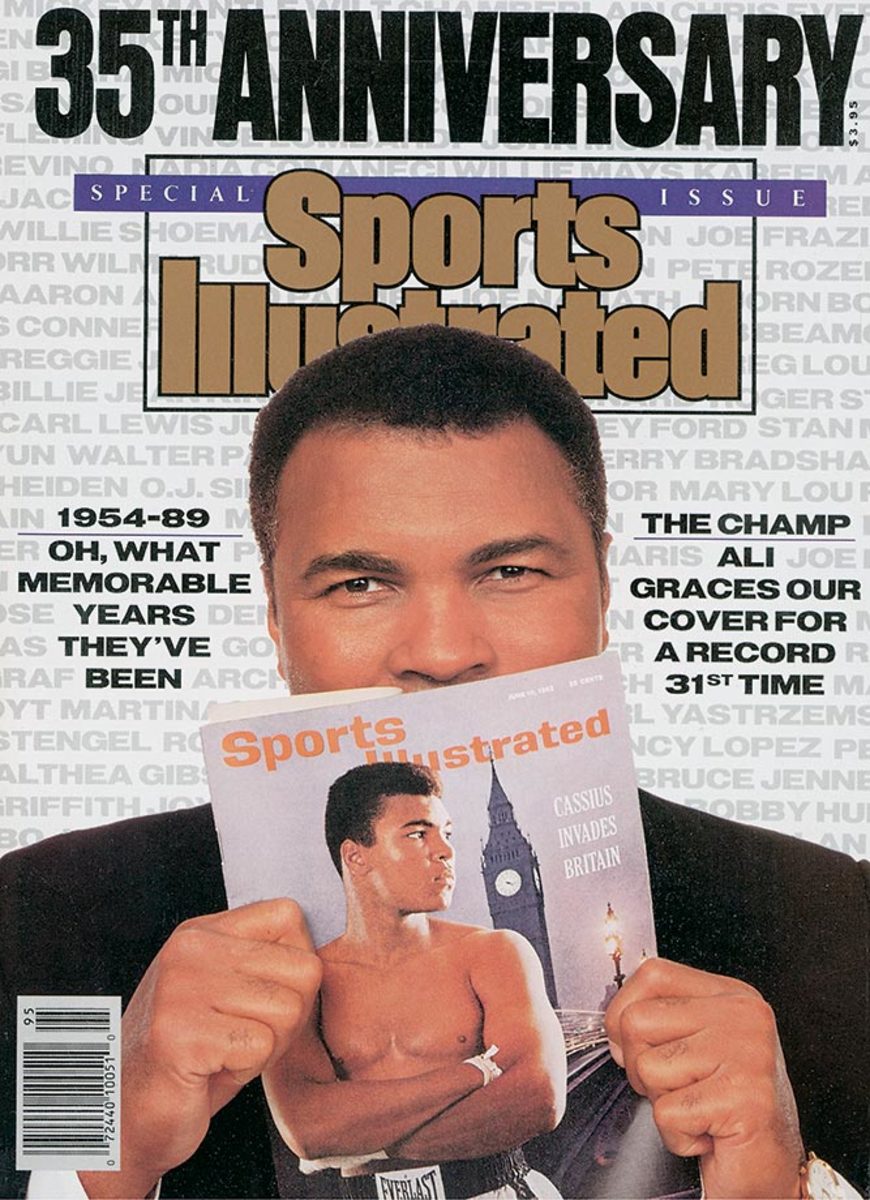

November 15, 1989

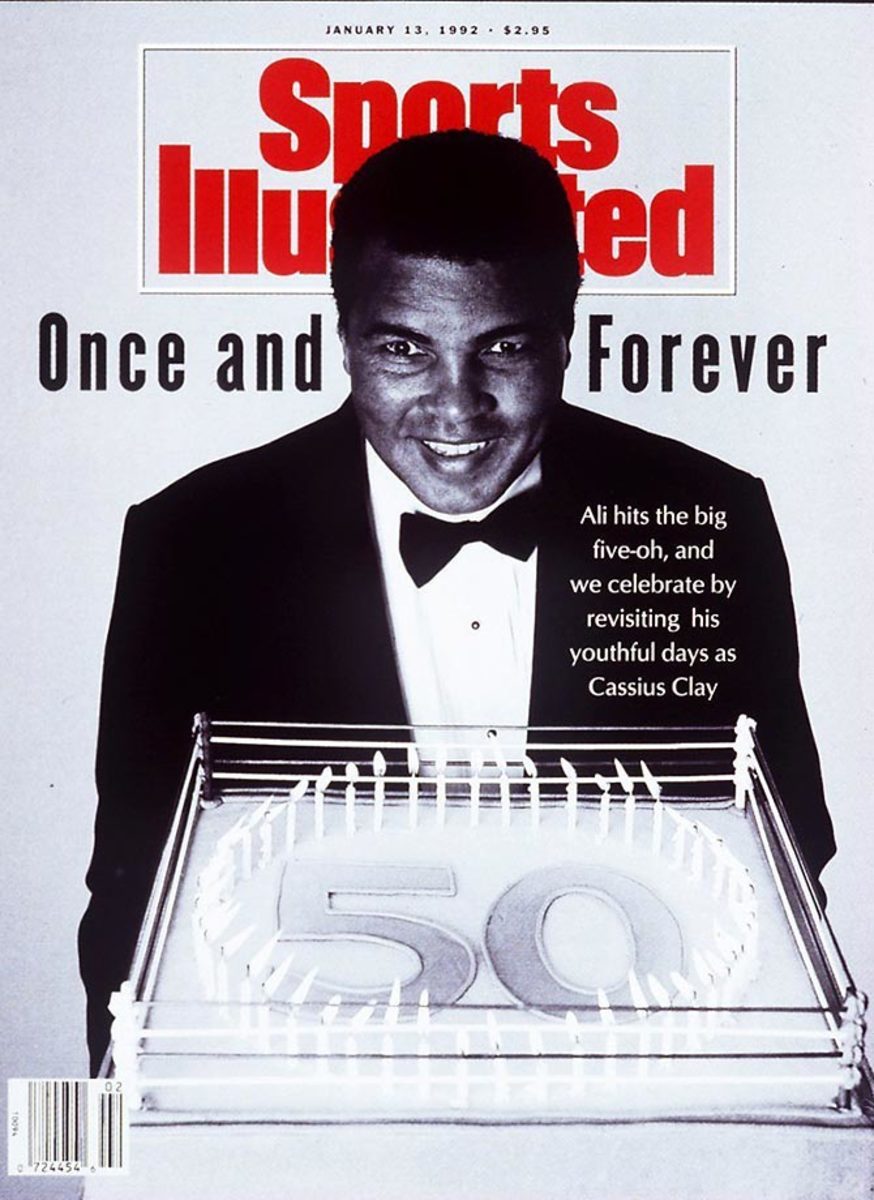

January 13, 1992

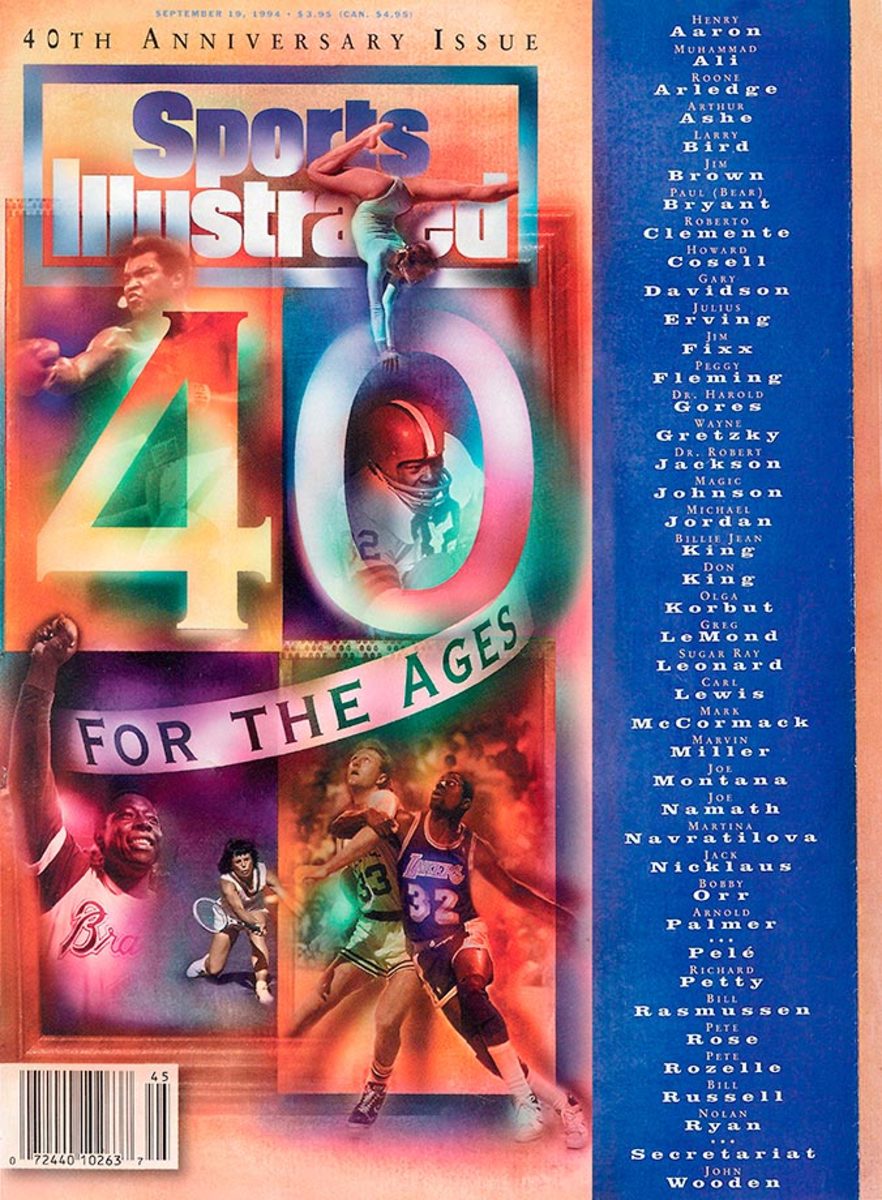

September 19, 1994

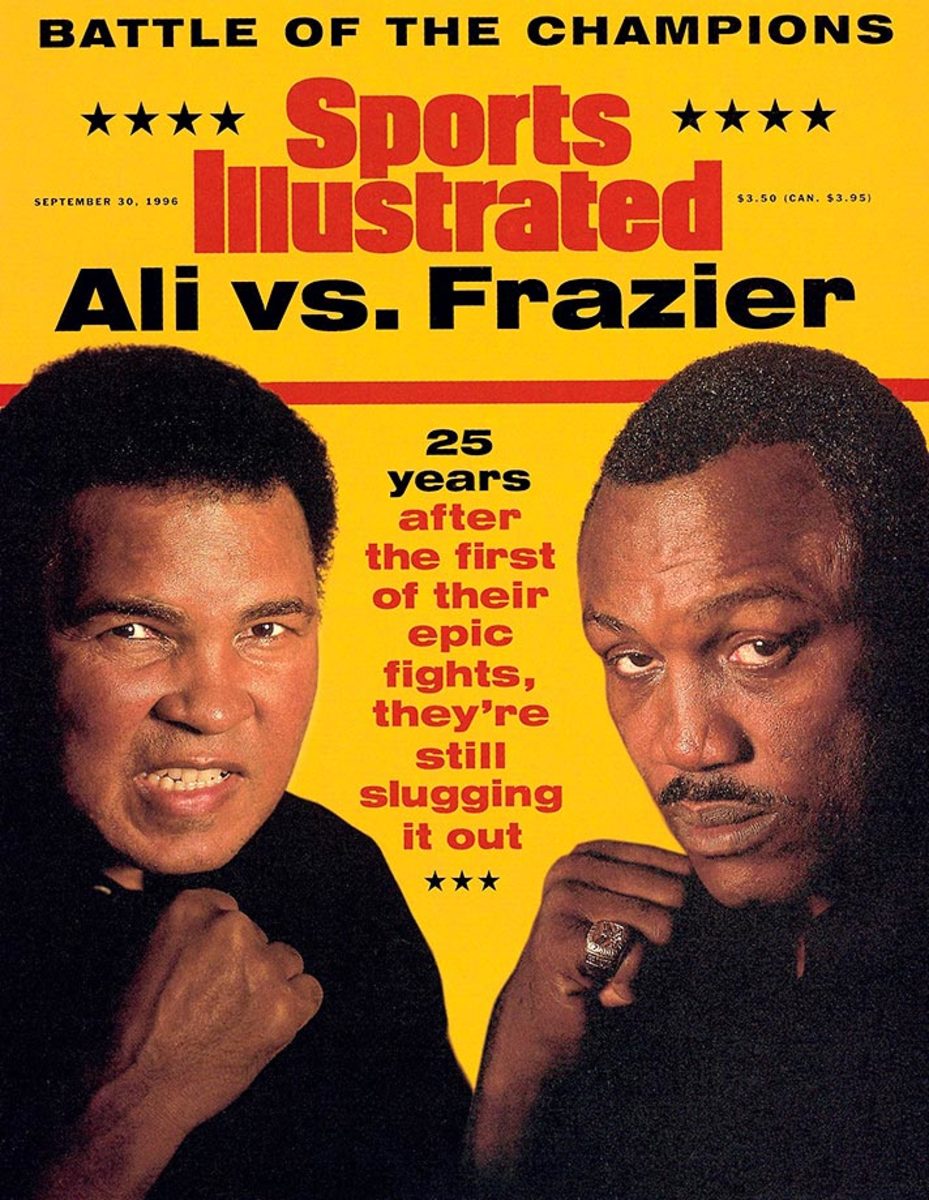

September 30, 1996

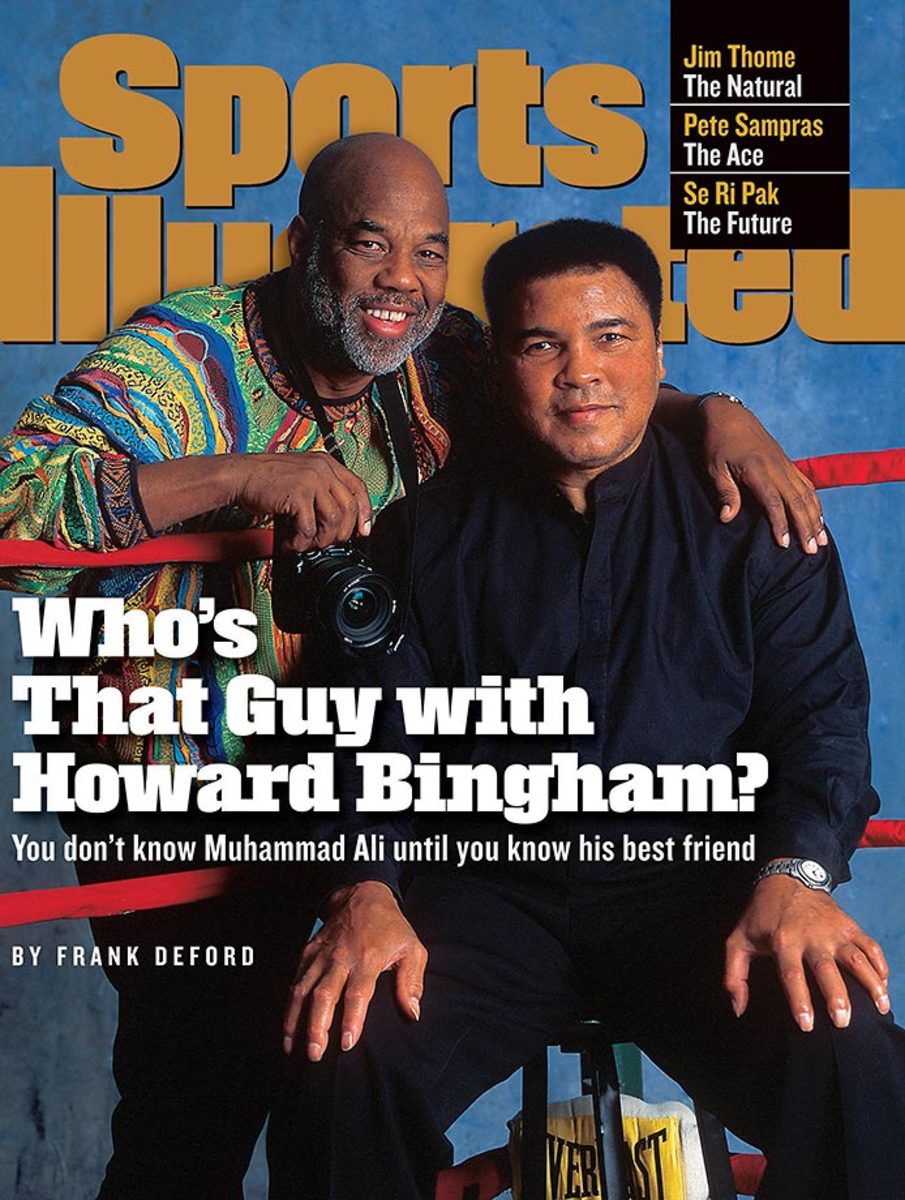

July 13, 1998

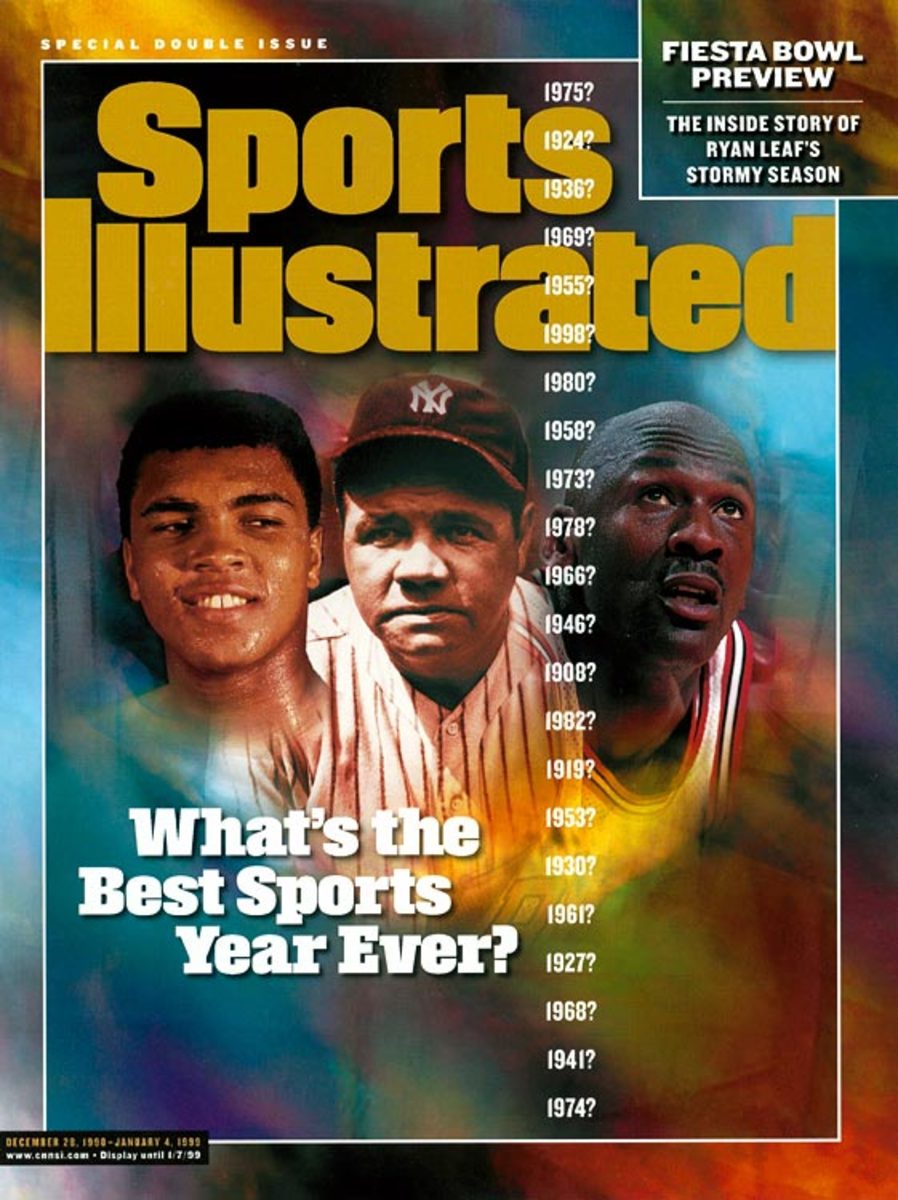

December 28, 1998

July 26, 1999

November 29, 1999

April 26, 2004

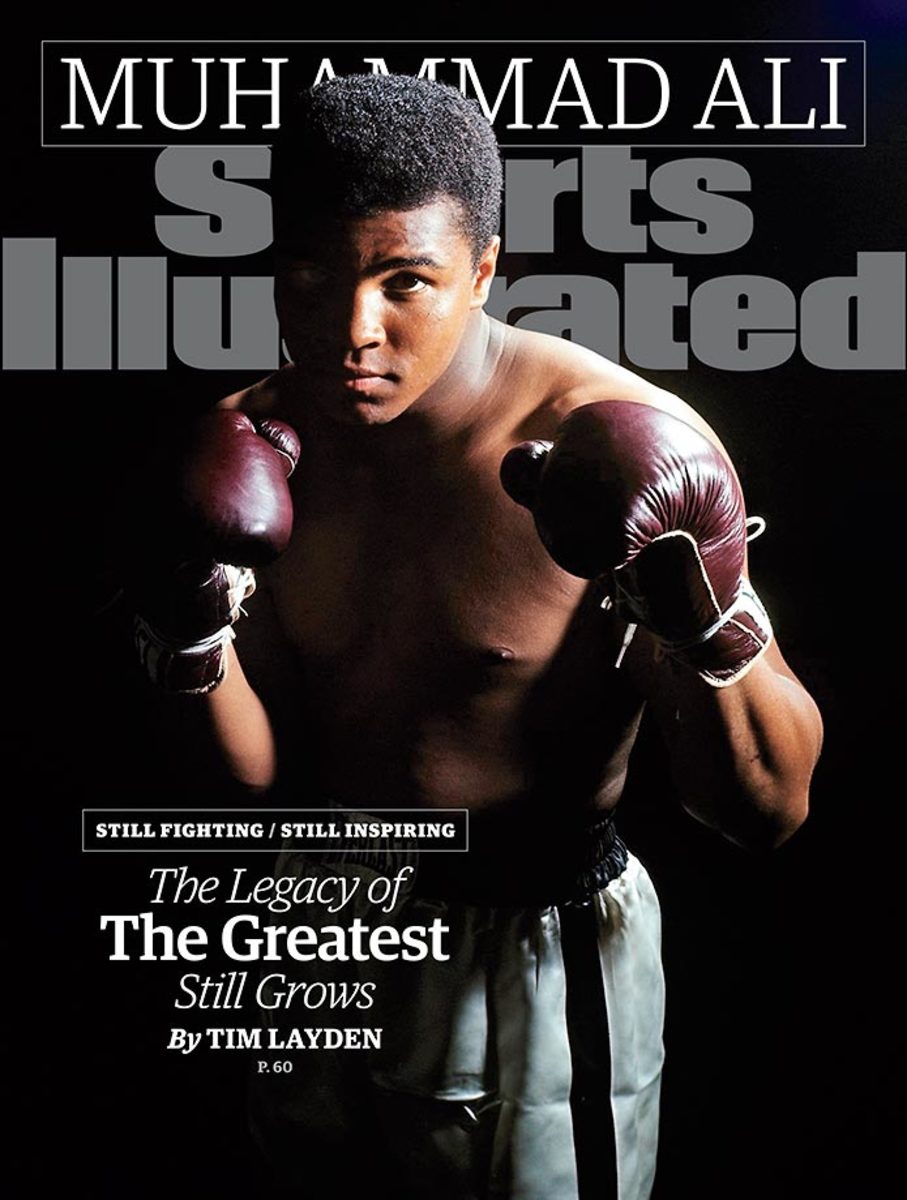

October 5, 2015

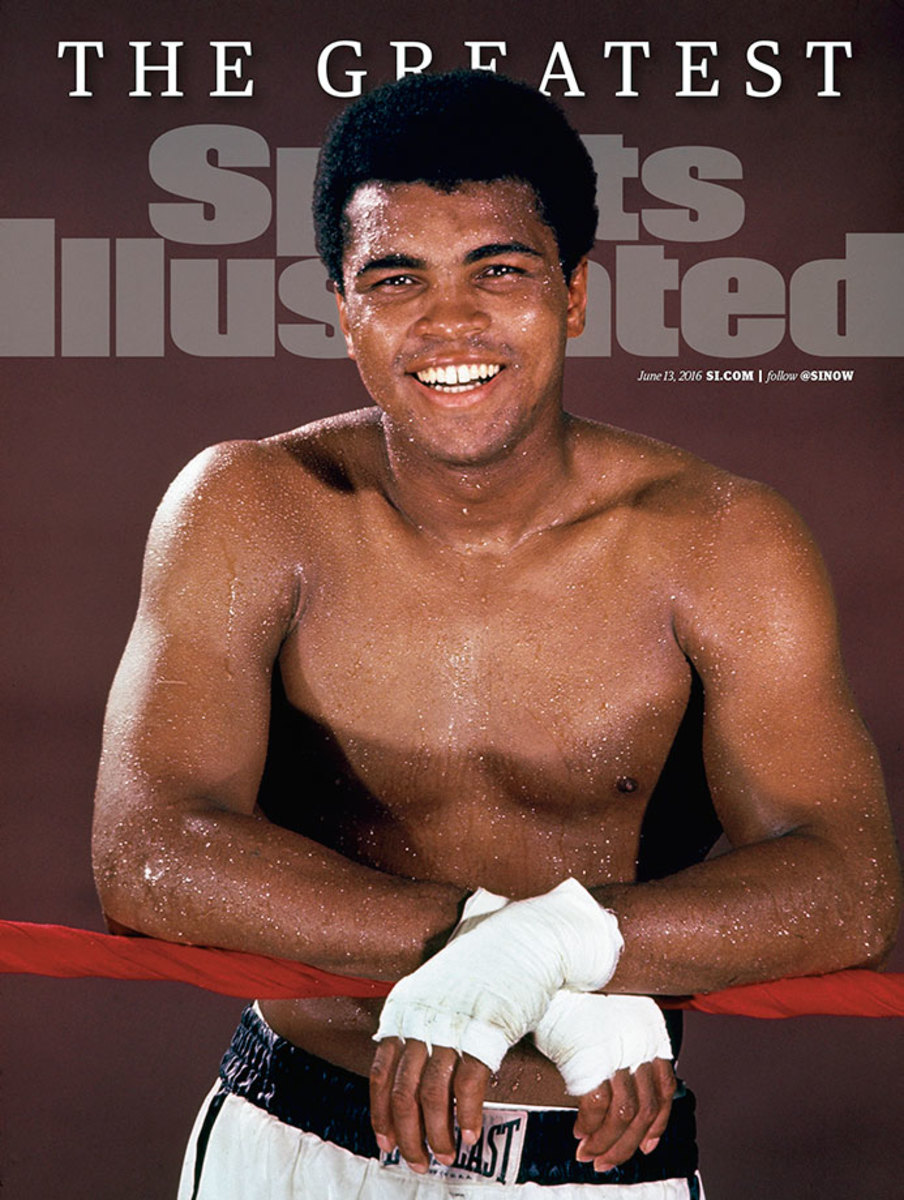

June 13, 2016

Joe Namath was the quarterback of the New York Jets. The Beatles were bigger than Jesus Christ. Lyndon Baines Johnson and Richard Nixon were presidents of the United States. Martin Luther King was vibrant and alive. And then he was not. An unpopular war in a faraway country was a background to everyday life. Demonstrations and riots were commonplace. A powerful noise was everywhere, the sound of frustration and anger and civil discord. A boxer tried to stick and jab, land a haymaker against his own government.

Muhammad Ali, very much a human being, was in the middle of everything.

Right here. Now.

This was the guy who drove the Cadillac. Not the saint who rode in the back.