Mauro Ranallo Aims to Reach an Important Audience With Documentary on His Bipolar Disorder

Mauro Ranallo is shirtless and angst-ridden and rubbing his temples with both hands, while sitting inside his Las Vegas hotel room in May of 2015. He’s talking to himself. He wants to rule, he says, wants to be the best ever.

It’s the greatest night of his professional broadcasting career. He has just finished calling the Mayweather-Pacquiao fight for Showtime, giving voice to the most watched pay-per-view in boxing history. There’s a camera in the room, and it’s rolling, capturing Ranallo as he shifts from elated to apoplectic. He’s doubting his performance and hating himself for doubting it, for not valuing this moment, which was three decades of hard work and hospitalizations in the making. He’s saying to himself, “Wow, dude, I’m really a prisoner of my own f------ mind and if I can’t appreciate tonight I’m going to kill myself.” There’s a long pause. And, scene.

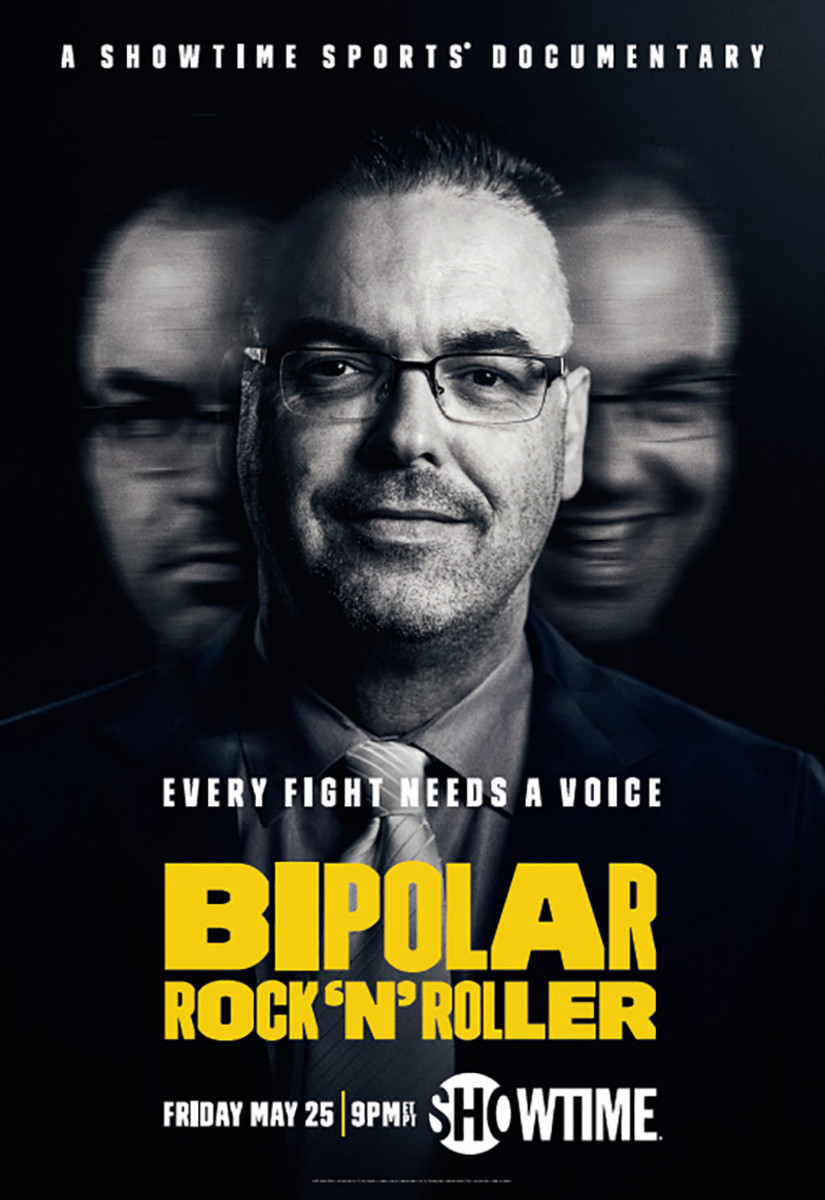

Moments like that can make for uncomfortable viewing in the Ranallo-focused documentary Showtime will air Friday. And that’s exactly the point, Ranallo says. The film is called Bipolar Rock ‘N Roller, and it chronicles both his career as the “Forrest Gump of Combat Sports”—the first broadcaster to call boxing, MMA, kickboxing and professional wrestling—and his life with bipolar disorder.

Ranallo believes the timing is important here, noting that the sports world has never been more attuned to the need for increased mental health awareness than in recent months. Several prominent athletes have spoken out. That’s NBA players like Kevin Love and DeMar DeRozan openly discussing depression. That’s NFL receiver Brandon Marshall, who has also been diagnosed as bipolar, continuing to attack mental illness stigmas with his Project 375 foundation. That’s players and leagues and fans of both starting to see that athletes, seemingly the most invincible among us, deal with fear and anxiety and mental disorders, same as everybody else.

The broadcaster embodies this movement—and this moment—and his documentary wades deeper into the issue, showing viewers what mental illness looks like. Fans who know Ranallo as the voice of Showtime Championship Boxing, or the host of WWE’s NXT and Bellator MMA, actually see the broadcaster after hospital stays, in the throes of mania and openly wondering if he wants to live. He put all that out there, he says, in hopes of showing others that they’re not alone, that they need help, that they can succeed.

None of that makes his struggle any less real. Take, for example, when Ranallo called Mayweather-McGregor last summer. He finished that event, the second-biggest PPV of all time, returned home and cried and cried. Then he looked at the chandelier in his bedroom and wondered if, he says, “it could handle my weight.”

On a recent weekday inside his apartment in Simi Valley, Calif., Ranallo jokes that he performed his first broadcast on the day he was born, doing play-by-play, he says, “of my entry into the world.” Reality wasn’t far off. By age 4, while growing up in Abbotsford, British Columbia, he was collecting old toilet paper rolls to use as microphones and creating his own TV shows. He watched everything. Read everything. He saw storytelling as a way to create the worlds he immersed in, as no less than “how we exist.”

His family lived on a small farm. His parents had emigrated from Italy, and his father, Elio, raised 10,000 chickens, worked in hatcheries and opened a pizza restaurant. The family lived on a “dead-end road”—which Mauro saw as a metaphor for his life prospects.

Money was always tight and the family television had only three channels. But sometimes those channels showed professional wrestling, and the entire Ranallo clan would watch. The family also attended local wrestling shows.

At night, as a teenager, Ranallo dreamed about the careers he wanted, the worlds his voice would open. Pro wrestling announcer. Deejay. Radio host. Broadcaster. It all seemed so far away, so impossible, and yet when he was 16, Ranallo attended an All-Star Wrestling show at his high school with his best friend, Michael Janzen.

He introduced himself to the show’s promoter and somehow ended up with the live microphone. He called the rest of the show that night. The promoter asked for his number and phoned a week later, and that’s how Ranallo became a professional broadcaster, going to work at BCTV for a wrestling show that aired nationwide for the next three years. He played a manager on screen, a heel, inhabiting different villainous characters, trying on personas. He was 16.

Fear drove him. Fear of being found a fraud. Fear of his father’s disapproval. “That launched my entire career,” he says, “and helped manifest my mental illness.”

He pauses, sitting on a black leather couch in his living room, looking down at his feet. Then says, softly, “I thought I could control it.”

July 7, 1989. Ranallo’s phone rings. It’s Janzen’s sister. She sounds at first like she’s laughing but she’s actually crying hysterically. She breaks the news to Ranallo, in halting sobs that changed his life. His best friend had fallen asleep under a tree and died from a massive heart attack, the result of a pre-existing condition no doctor had ever detected.

Ranallo was 19. Unable to cope with his friend’s death—“I didn’t think I would survive it,” he admits—he was hospitalized for the first time that year. A doctor diagnosed him with “delirium,” and that was the first time that someone told him he might need help.

In hindsight, there had been signs of his internal struggle. Like how hyper he was in class, the manic energy, the way he earned mostly A’s and did the morning announcements and helped after school with special education classes, all while requiring little sleep. All that countered by how he was at home: shy, hypersensitive, angry, prone to vicious mood swings.

He worked as a local TV and radio personality from 1991 to ’97, in addition to the DJ and wrestling gigs. People recognized him on the streets of his hometown. They didn’t see him on commercial radio breaks, weeping and raging inside the booth at the station, then gathering himself seconds before he went back on air. They didn’t see the wrath he spewed at those closest to him, the death threats, the diatribes, the anger so heavy that when it coursed through his body it made him shake like a vibrating cell phone.

His private and public lives started to converge. Another doctor told him he was manic depressive, and he made a joke about how that sounded like a cool Jimi Hendrix song but “has nothing to do with me.” One girlfriend dragged him to the emergency room, begging the doctors to “do something with this guy because there’s something really wrong.” Alone later, Ranallo looked up “manic depressive” online—and the descriptions he found read more like an autobiography. Still, he ignored the doctors who suggested therapy and medication.

Ranallo was hospitalized six times in his early 20s. His longest stay in a psychiatric ward lasted three months. So began his life pattern: reach success, become overwhelmed, slide into a manic episode, then check into a psychiatric ward.

Even then, in 1999 he became the voice of Stampede Wrestling in Calgary. And even then, Ranallo says, “There was a period of time where I was drunk 42 days in a row. I was self-medicating, doing cocaine, trying to find the pain. It just kept bubbling up and I just kept pushing it down. Finally, it would pop up like a jack-in-the-box, this snakehead that no one could predict.”

When Ranallo was hospitalized for a seventh time, in 2003, he says someone sent an Italian priest to his room. The priest brought holy water and performed a séance. Ranallo says he got out of bed for the first time in two weeks, showered, shaved and donned clean clothes. “Whether I tie it to the priest or not, I needed to do it on my own,” he says. “I had to want to get better.”

Ranallo went home after that visit and had a random voicemail from Bas Rutten, the Dutch actor who also did mixed martial arts, kickboxing and professional wrestling. Rutten wanted Ranallo to be the voice of the Pride Fighting Championships, an MMA promotional company based in Japan. Ranallo accepted.

From 2003 to ’06, Ranallo also truly sought help for the first time. He developed a routine. Daily, round-the-clock cannabis use helped. So did meditation, medication, exercise, therapy and hydration. He ate healthier, drank more water, took deep breaths and pounded out music at the keyboard in his living room.

In 2006, he met Haris Usanovic, an editor/cameraman he worked with. They started hanging out after work, with Ranallo revealing all he’d gone through, until one day Usanovic asked him, “Would you let me tell your story?” Eventually, he agreed.

Ranallo worried that skeptical viewers might see their project as more like performance art than documentary, in the vein of one of his heroes, the comedian Andy Kaufman. He also continued to self-sabotage as they filmed, racking up credit card debt and massive phone bills. Sometimes he’d call one of those 900 numbers and set the phone down, not even listening, while being charged for every minute.

Despite all that, Ranallo became an Internet and fan favorite for his excitable delivery, vivid descriptions and free use of metaphors. He says things like that face looks like it was put together by a ransom note and you’re looking at a guy with educated feet; the left foot from Yale, the right from Harvard. An opponent “smoked Klitschko like a Monte Cristo” and “Wilder’s right hand is like Thor’s hammer and he is Ragnaroking Stiverne.” If his delivery sounded manic, well, it was! Everything that gave him his career—his brain, the manic energy, his hyperkinetic style—was also what would threaten all his progress every time he had an episode.

After 10 years of filming, he had to confront an existential question. Did he really want to show all of himself and his disorder to the world?

As the head of Showtime Sports, Stephen Espinoza says he was aware that Ranallo had been hospitalized while employed by the network. But he did not know the full impact of bipolar disorder on Ranallo’s life—the cannabis use, the despair, the lowest of lows—until he watched the footage. Then he gained an even greater appreciation for Ranallo’s work.

Still, his first instinct was to tell Ranallo to pull back, to ask if he had fully considered exactly what he was projecting to the world. “Then I realized that in itself, that urge, was symptom of the same stigma,” Espinoza says. “No one says, You look really skinny and sick when you were battling cancer. Or, You shouldn’t show that horrible injury that left you immobilized because you don’t look strong in a body cast.”

“I thought I was trying to protect him,” Espinoza says. “And that’s actually the whole point of this. People will continue to make judgments until we get comfortable enough to talk about it openly. Like you’re dealing with a broken leg or diabetes.”

That’s what Ranallo wants: to change minds the way that he enlightened Espinoza. He wants to detail his 2015 visit to a psychiatric ward in the United States and all the neglect he saw there, from rooms with little furniture to no sense of warmth or compassion to the day he says that none of the patients saw a nurse. He wants change, wants to show others what is possible—“that,” he says, “you can have this and do whatever the f--- you want.”

Ranallo welcomes the conversations the film will prompt. As soon as the trailer was posted online, he heard from hundreds of people, many who suffered from depression or had been diagnosed with mental illness, several who had considered suicide or lost friends who took their own lives. “It breaks my heart. It hurts me to my core,” he says. “Talk, talk, talk; don’t suffer in silence, don’t be ashamed—save a life.”

Like his own. He still calls Janzen’s parents every year on July 7, no matter where he wakes up in the world. He paid off his parents’ mortgage recently. He wants to be a male Oprah, interviewing people about their mental health, carrying inspiring stories to the masses. None of that changes who he is. “Hi, I’m Mauro Ranallo and I’m bipolar” is often how he’ll introduce himself. And yet all of that also proves what’s possible, both for Ranallo and the people he is so desperate to reach. There’s so much he wants to tell them. They’re not alone, not crazy, not worthless. They’re just like him, the Bipolar Rock ‘N Roller, a man who spent his life assigning meaning to events only to realize the most meaningful story he ever told was right in front of him.

His own.