In Rematch Against Abner Mares, Leo Santa Cruz Finds Motivation in Father's Cancer Fight

Whitter Boulevard in Montebello, Calif., is a wide slab of asphalt bleached gray by the sun and cracked at least partially by a half century of bouncing lowrider cars. Steer into one of the strip malls among the brown palm trees and apartment buildings, and peek your head into what looks like yet another mom-&-pop taqueria and you’ll find the Last Round Boxing Gym. You’d never guess that a world champion trains in this cramped, humid space, and if you didn’t know him beforehand you’d have a hard time picking Leo Santa Cruz as the titleholder among the dozen or so featherweights flitting around.

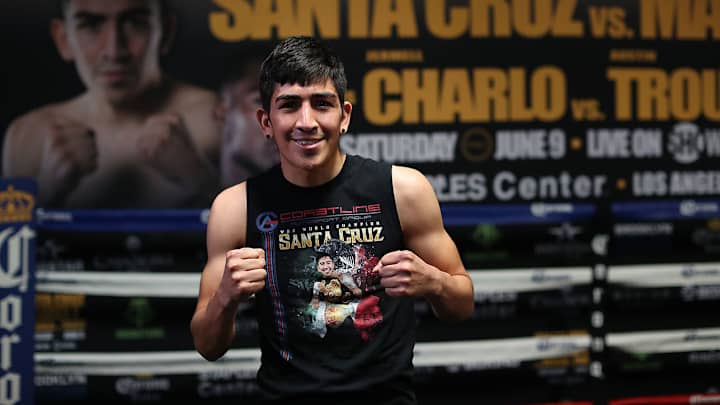

That’s Santa Cruz in the corner, the unassuming, 125-pound wisp who is relentlessly punching the air, his fifth t-shirt of the workout soaked to its last fiber. Nearby sits his father and lifelong trainer, Jose Santa Cruz, his collared shirt wide open at the top, gold chains dangling, wearing a large cowboy hat in the Michoacan style of southern Mexico. Nothing about the elder Santa Cruz reveals his ongoing fight against the cancer in his spine other than the therapist rubbing his upper back as he watches Leo’s spindly legs float him through timed rounds that consist of non-stop feinting and punching. Always punching.

Santa Cruz, 29, is training for his second title fight in the last three years against Abner Mares. Their first bout, in August 2015, was a Fight of the Year candidate that registered more than 2,000 combined punches and ended in a decision for Santa Cruz, who retained his WBA super featherweight belt. The rematch on June 9 at Staples Center figures to be even fiercer. A second victory over the respected Mares (31-2-1) would vault Santa Cruz into a new earning category, which means something different to him than it does to most champions.

His dad’s multiple myeloma is in remission, but it has come back before, so there could be another round of chemotherapy ahead, which, among other impacts, would cut deeply into the $750,000 purse he’ll get for fighting Mares.

“I have to be able to support him,” Santa Cruz says after his workout. “My dad’s insurance doesn’t cover everything. Only the little things.” Jose’s last round of chemo cost more than $200,000 out of pocket. It’s a small price to pay for his dad’s health, and it’s a load he’s happy to bear. It comes naturally for the man known in East L.A. as un verdadero hombre del pueblo—a true man of the people. Such a man, on this day, must also humor the locals who stroll in off the street and interrupt his jumprope session for a selfie, and he must chat up the destitute enchilada salesman who rolls his cart through the door. The smile that’s never too far from Santa Cruz’s expressive brown eyes is for everyone, and if you can stand the humidity in here long enough, you might learn what’s behind it.

“Growing up, my mom and dad taught me to be the same person, that money doesn’t change you,” he says when the two-hour training session is done. “A lot of people, when they make money they spend it on jewelry or going clubbing. Me? These sweatpants cost $10. I don’t care. I wear them. I still go to swap meets. When I see those people, I see me. Because I remember us sacrificing ... As long as you have family, you can be happy even if you don’t have a lot of money.

“Of course I think about the possibilities,” he says of the Mares fight, which will headline Showtime’s prime-time boxing menu this Saturday. “If I win, big doors open for me. Unification. Maybe a move up in weight, look for another title, maybe against [Vasily] Lomachenko or one of the other champions at 130. But if I lose, everything goes down. I don’t want to start from the beginning.”

The beginning was around 1980, when Jose Santa Cruz came north from Michoacán de Ocampo and settled his growing family in a Compton apartment. “We suffered so much growing up,” says Leo, born here in ’88, the youngest of Jose and Elodia’s four children. “We didn’t have nothing. No toys at Christmas. I never got birthday parties or presents. I knew that if I had a family one day I didn’t want my kids to suffer like that. I wanted to give my family a good future. That’s the reason I fight.”

The only loss on Santa Cruz’s 33-1-1 record came in 2016, a few weeks after he learned that his dad—who had lined little Leo up next to his two older brothers when they were kids and told them, “One of you is going to be champion. Whoever it is, the rest of you have to help him”—was diagnosed with cancer.

“I was devastated,” Santa Cruz says. “It was like they threw a building on top of me.” For the first time since he was a teenager, he fought without his dad in his corner, a detail that helped Northern Ireland’s Carl Frampton take Santa Cruz’s title two summers ago with a majority decision at Barclays Center in New York. “I couldn’t concentrate on boxing,” Santa Cruz explains, careful not to make excuses. “I couldn’t focus on training. I was thinking about my dad. What could I do? Why is this happening?”

That summer, Jose underwent surgery to remove the cancer and install a plate in his lower spine. He returned to his son’s corner in time for the Frampton rematch in Las Vegas in 2017. This time the judges’ decision went Leo’s way, and the belt came home with him to East L.A. His older brother Antonio is a capable conditioning coach, “but my dad is the smart one,” Leo explains. “He’s the brain, he’s the one who tells me how to fight in certain situations, how to fight each fighter. And—just his presence. We have been together since I started boxing as a kid.”

What is his dad telling him about Saturday’s opportunity against Mares? “That this is my time,” says Leo, a father of two whose fiancée, Maritza Amador, is expecting a daughter in August. “This is my opportunity to keep climbing. If I win this fight I’ll have the chance to do a few more fights and retire healthy.”

For now, he bears the weight of supporting all of the Santa Cruzes, his parents and siblings included, who live at his modest compound in nearby La Habra Heights. “There are times that my body feels tired, but I know I can’t stop,” Leo says. “My family depends on me. We don’t want to go back to when we had nothing, so I’m going to sacrifice, continue a little bit more.”

He lists a half dozen Latino fighters from this neighborhood who returned to the ring too often in their quests to feed their people, and who paid a dear price for it, some of them with their lives. Santa Cruz isn’t a knockout artist, and his weight class values punching in volume, so each fight can exact a brutal toll. “It’s hard,” Santa Cruz says. “Time is running, you’re getting older. I want to fight as many times as I can, but sometimes my body needs rest. Which prolongs the time [between fights]. If I don’t fight as much, then I’ll have to retire when I’m older … My family and I have talked about it. When my body says, ‘No more,’ or if I get beat up a lot, that’s when I’ll hang ‘em up.”

And if a situation arose after his retirement in which his dad needs an expensive procedure? “Of course I would fight again,” Santa Cruz says. “I would do it for him … I would give my life for my dad, or any of my family.”

In the meantime, one of the last bona fide heroes in American sports keeps punching, keeps lifting up the hungry young fighters who train alongside him, five of whom will fight on the Santa Cruz-Mares undercard at Staples Center. Mares, another L.A. product with Mexican roots, has waited 21 months for this rematch and is working with a new trainer, the highly respected Robert Garcia.

As for the Santa Cruz family’s most dangerous opponent, Jose says that he has “KO’d” his cancer. “Now my only battles are maintaining my medications ... The medicine is really what the biggest struggle is because it makes me feel so sick. But even then, you can’t keep me away from the gym with my son.”