The Many Stages of Manny: How Pacquiao Keeps Reinventing Himself

The latest version of Manny Pacquiao plucks a rogue gray hair from near his temple and dutifully spreads a half-dozen vitamins across his placemat. Breakfast has just ended at his mansion in Los Angeles, where members of his entourage dispense gobs of hand sanitizer and clear dried squid from the dining table and a basketball game from the Philippines plays on the nearby flatscreen.

One man lingers near Pacquiao, holding a plate of sliced bananas, potassium on call. Another stands guard out front, clad in a security uniform, gun holstered near his hip. Others fall into debates, make coffee, wear sunglasses indoors, read Bible verses or catch morning naps. Amid all the jockeying, the boxer pays the chaos no attention. His eyes linger on a laptop. His mind drifts back in time.

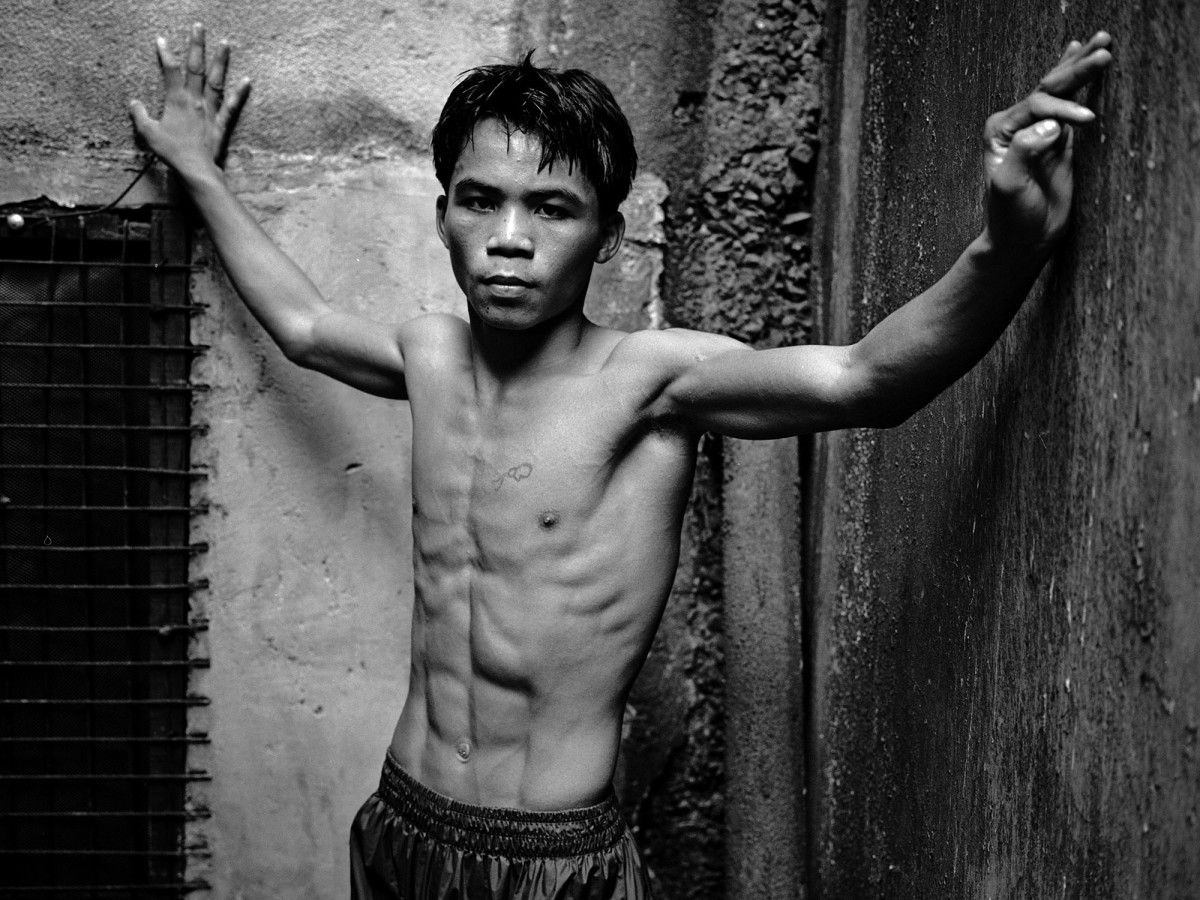

“I was 16,” he says, pointing at the first of two dozen photographs pulled up on the screen. In this shot, he’s still living in the Philippines, so skinny that his ribs jut from his chest. He’s not yet famous, but he’s almost a professional boxer, just before his debut in 1995. “If you look at that boy and you tell him, you will be an eight-division world champion, would he believe it?” Pacquiao asks. He answers his own question. “No,” he says. “He would not.”

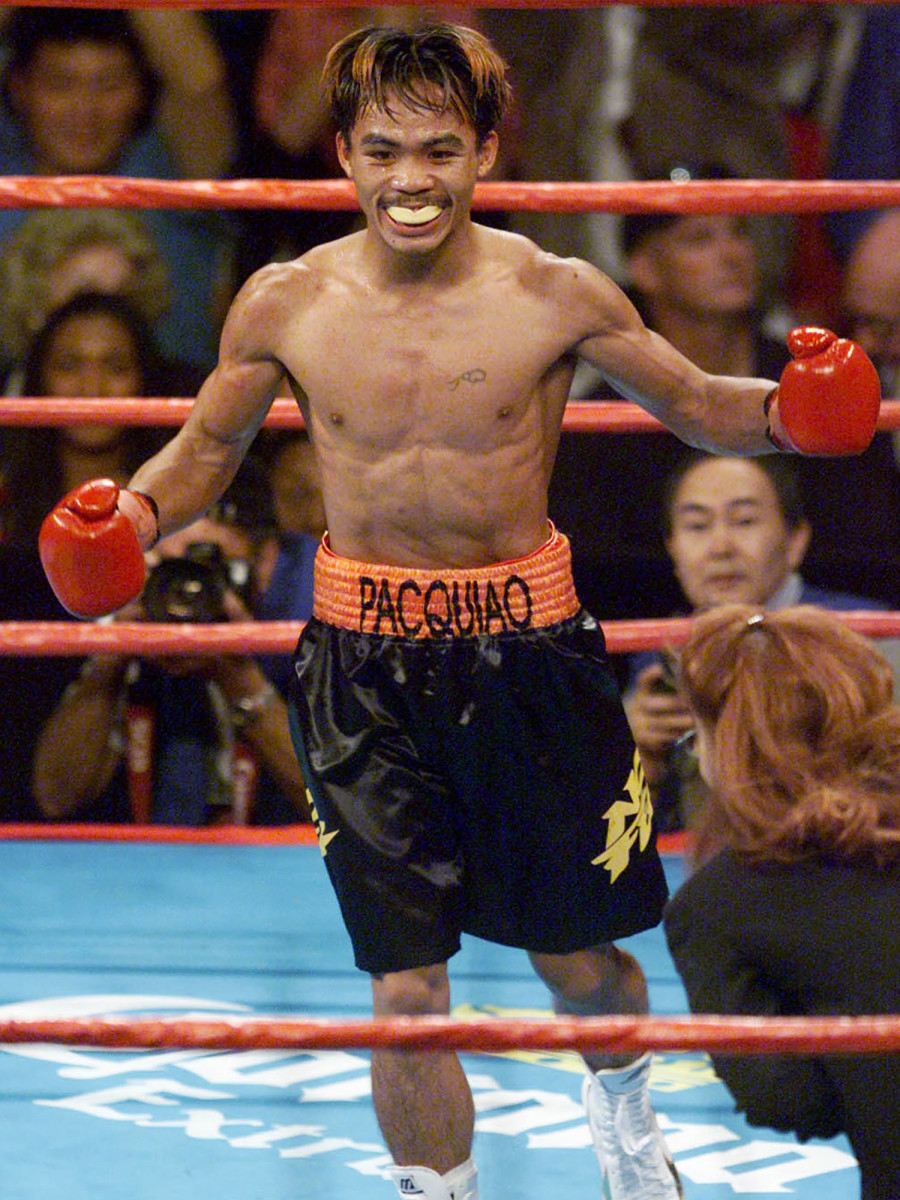

A crowd of 25 or so gathers as Current Pacquiao considers so many earlier versions of himself, from Young Pacquiao to Rising Pacquiao to Verge-of-Stardom Pacquiao. “June 23, 2001,” he says. “Las Vegas.” That night, he fought Lehlo Ledwaba, as a late replacement in a bantamweight title bout who confronted both a respected opponent and something like 60:1 odds. His new trainer, Freddie Roach, went from casino to casino, trying to place a bet; Pacquiao was such an underdog that no book would take one. He won by technical knockout and celebrated with a trip to the local diner for cheap hamburgers. He could count his entourage there on one hand. “Look, my hair,” he says, laughing, pointing at the frosted blond tips.

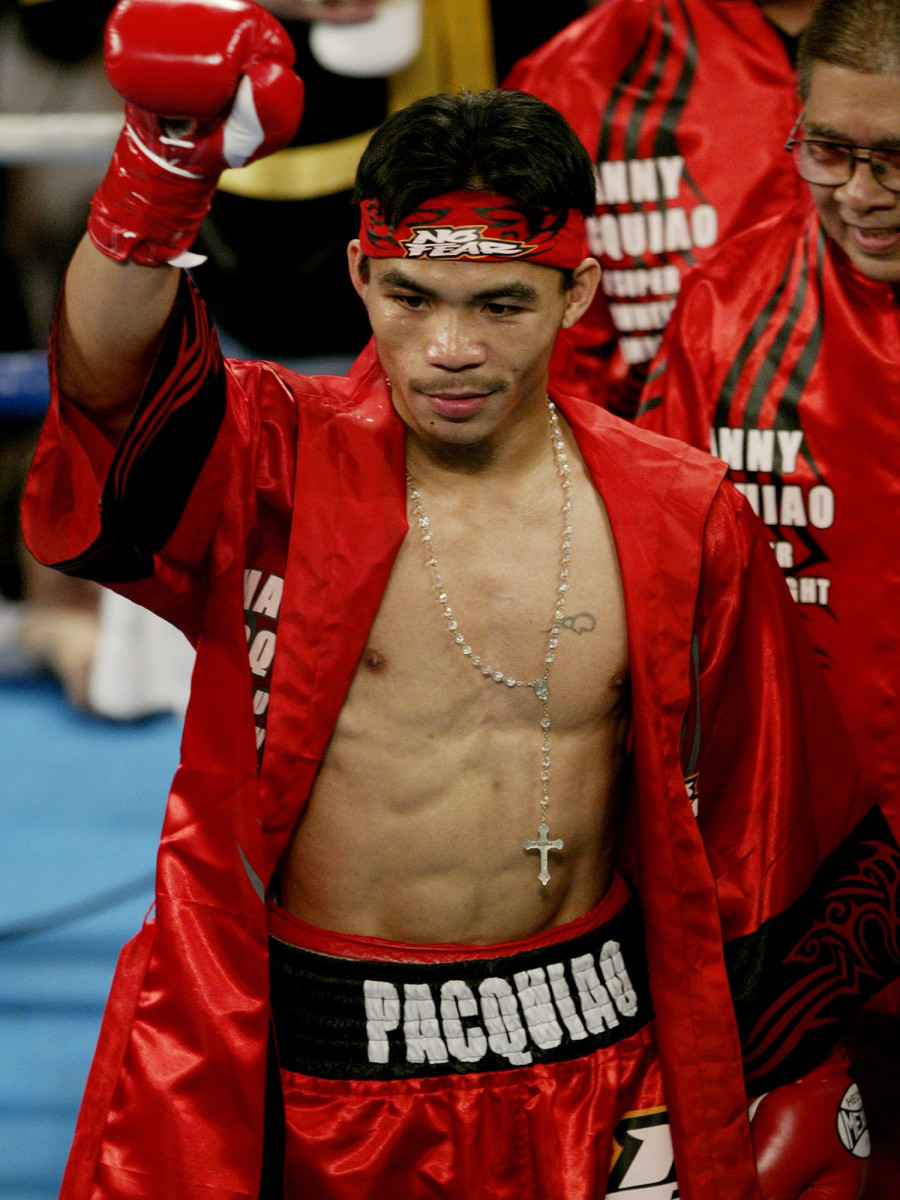

So many Pacquiao iterations, so many career turns, so many revenue streams created. As his fame grew and his reach expanded, Pacquiao morphed and transformed and changed and changed some more. He became a national champion, then world champion, then fighter of the decade (2000s), then one of the best ever. Along the way, he was knocked down and knocked out and knocked unconscious. He crooned ballads and played pro basketball and started a cockfighting farm and starred in a superhero movie—about himself. He became a Congressman in 2010 and a Senator in ‘16. He started, grew and nearly lost his family. He found both God and controversy over the religious views that he espoused.

He stops at a picture of his daughter, now 13 years old, then 4. He points at her long gone chubby cheeks. He laughs at a snapshot from his movie premier, when he’s clad in bright red superhero tights. He grimaces at a series of knockout shots that earned him an old nickname, the Mexecutioner. So many pictures. So many Manny Pacquiaos.

The boxer ruminates on all this in late June, the various turns his life has taken since he climbed the stairs to Roach’s gym 18 years ago that week, so many stages in one messy and transcendent life. He’s 40 now, and set to face undefeated welterweight champ Keith Thurman on July 20 in Vegas, almost four years since many first suggested he retire, before his worst loss and another career resurgence. At this point, most wonder why Manny Pacquiao is still fighting. But look closer at that screen. It’s the pictures that provide the answer. It’s his ability to rise and fall and rise again, to stumble in private and fall dramatically in public and return, both to the ring and the form that marked his improbable rise.

Against Thurman, he will climb inside the ropes for the 71st time, having both registered 39 knockouts and suffered seven losses and never failed to return. “I’ve never had a fighter with so many swings,” Roach says. “Not that pronounced. Not like Manny.”

That is Manny Pacquiao’s greatest gift. Not the nimble footwork, or the powerful left hand. But rather his flair for perpetual reinvention.

There’s another picture, in the downstairs wing at Wild Card Boxing, where Roach trains elite fighters in a former laundromat. The snapshot features four champions—Ruslan Provodnikov, Zou Shiming, Miguel Cotto and Pacquiao—and the trainer they once shared. Pacquiao is both the oldest boxer in the photo and the only one currently fighting. “Unbelievable,” Roach says.

The gym walls tell the story of the boxer’s and trainer’s collective rise. The battering of Marco Antonio Barrera (2003) that fully announced Pacquiao to the boxing world. The TKO of David Diaz (’08) that showed Pacquiao had added a monstrous right hand. The knockout of Oscar De La Hoya (also ’08) that pushed him deeper into the sports mainstream. The savaging of Ricky Hatton (’09), the bludgeoning of Cotto (also ’09), the breaking of Antonio Margarito’s face. (Seriously, Pacquiao shattered his orbital bone.) That night, in Nov. 2010 at Cowboys Stadium in Texas, marked Peak Pacquiao, when he battered a much larger champion who outweighed him by 20 pounds at super welterweight. Asked if he planned to defend the 154-pound belt afterward, he motioned at the bruises on his face and told reporters he would happily give it back to never fight a man that large again. “The good old days,” Roach says, wistfully. “I loved that. He was flat knocking people out.”

Fame changed that Pacquiao, as he started collecting vices along with knockouts, started drinking and gambling and cheating on his wife. His nights sometimes started at 11 p.m., leading to canceled training sessions the next morning. He became reckless, inside the ring and out.

In Nov. 2011, he showed up late to his third fight against Juan Manuel Marquez, having pleaded with his spouse, Jinkee, to attend and convincing her to go only at the last second. He walked into the ring cold, without warming up, and eked out an unsatisfying majority decision. Then he retreated to the locker room, where it took 28 stitches to close the gash that ran diagonally through his right eyebrow. Jinkee lectured as her husband grimaced. She called him “Bad Manny,” while both recited The 10 Commandments.

Pacquiao found God again soon after, marking another reinvention. Around that same time, though, he lost what Roach calls his champion’s “killer instinct.” He stopped knocking out his sparring partners. He told his trainer he could “beat my opponents without hurting them” and Roach considered hunting for scripture that sanctioned violence so that he could share those verses with his fighter, who now hosted Bible studies before training sessions. Worse yet, at least in a boxing sense, his power vanished as he let the vices go. Pacquiao soon dropped a controversial decision against Tim Bradley, then fought Marquez for the fourth time, meeting with Mitt Romney in the dressing room before his chief rival floored Pacquiao with a sixth-round knockout that left him lying facedown on the canvas. (Bonus Romney dialogue: Hi, Manny. I’m Mitt Romney. I ran for president. I lost.)

Many fighters would have quit then. Or soon after. Pacquiao was entering his mid-30s. He had lost his swagger, his knockout might and almost lost his family. He fought only once in 2013, winning a snoozer over Brandon Rios. He finally met Floyd Mayweather Jr., in the most hyped fight in boxing history in ‘15, after six years of obnoxious and stalled negotiations. But he suffered a torn right rotator cuff in training and never threatened Mayweather in defeat. The he-should-retire chorus gained momentum. And two years after that, he traveled to Australia, caught a cold and appeared disinterested in another controversial loss, this time to Jeff Horn, a schoolteacher turned world champion. Most thought that Pacquiao won that fight, but what mattered more was how he looked: old, done, not like himself. “He didn’t want to be there,” says Sean Gibbons, one of his chief advisors. “Training was terrible. He had no fire, no spark.” The chorus grew toward a clamor.

That night, when Roach told Pacquiao in the dressing room that he might want to focus on boxing or politics but would struggle if he wanted to continue to do both, well, it looked like The End. Pacquiao fired Roach after that conversation, a split that lasted for just one bout. Looking back, though, it marked another pivot point, the beginning of his latest transformation.

How? How did Pacquiao ascend in the first place, become an international star, transcend a niche sport like boxing, sign endorsements with the likes of Nike and become the most famous person in the Philippines and one of the most recognizable people in the world? How did he come back from the losses, the knockout, the brink of divorce? How did he repair the damage done by the inexcusable comments he made on same-sex marriage that drew the ire of gay rights groups and cost him sponsors, including Nike? He kept fighting. For the money, of course, but also for his family, his career and his damaged reputation.

How? “Boxing is the common denominator,” says Justin Fortune, his workout czar, gesturing at the gym as Pacquiao pummels a speed bag. “He f------ loves this. More than anyone I’ve ever known.”

Pacquiao came to realize, Fortune argues, that all the spoils garnered during his ascendance—the movies and albums, the fame and fortune and political appointments, even the vices—were only possible because of boxing. The sponsors that left him, the writers who suggested he retire, they saw what he recognized deep inside. That he was distracted, that he had grown bored, that he needed to find a better balance between the reckless fighter who almost lost everything and the gentler boxer who could no longer fight like he once did. This wasn’t about redemption; Pacquiao knew some would never forgive his worst transgressions. This was about moving forward, in the only way he knew how, with fists raised, forever evolving. Some of that growth was natural, some uneven. But Pacquiao decided he would go down his way: fighting.

“He’s a one-time deal,” Fortune says. “You’ll never see another Pacquiao. Never see a career like this.” Look at Mayweather, he continues, in way of a comparison, noting all the Instagram posts: the world travels, the private jets, the stacks of cash laid out on so many tables in so many mansions. It’s like Mayweather is still searching for something, while Pacquiao found something invaluable—a better version of himself.

“After the Horn fight, everyone thinks he’s done; it’s over,” Gibbons says. “And here he is reinventing himself again.” Pacquiao met with his longtime promoter, Bob Arum of Top Rank Boxing, but didn’t like the offers on the table, including a rematch against Horn. At one point, he excused himself to use the restroom and never returned. Instead, he found a man that Gibbons calls “Black Jesus”—or Al Haymon, the reclusive promoter who runs Premier Boxing Champions and can boast of the deepest welterweight stable in boxing.

Pacquiao signed with Haymon after knocking out Lucas Matthysse in 2018, before easily defeating Adrien Broner back in January. Those victories—and, more important, how he looked in them: sharp, precise, reinvigorated—set Pacquiao back on the path to the top of the division, where Thurman and others lurked. He hashed out his differences with Roach at luxury hotel in Beverly Hills. He made things right with Jinkee. He apologized for his comments on same-sex marriage. And he found the balance that had alluded him for almost two decades, finally becoming, at 40, something closer to the combination of fighter and man he wanted all along. “He seems,” Roach says, pausing, choosing his words carefully, “at peace.”

“Oh, he’s a much better person now,” Roach continues. “He had to lose the vices and lose the killer instinct. But he’s a better man, so I can’t really say that it was bad.”

In Thurman, Pacquiao will face an opponent not unlike himself before he thumped Oscar De La Hoya way back when: a hungry, young champion on the cusp of everything he thinks he wants. It’s fair to wonder if Pacquiao’s career will end like his opponent’s did, which is to say sadly, with younger contenders trading on the De La Hoya name, using the diminished Golden Boy for a career boost. It also seems, after Pacquiao’s latest reinvention, fair to consider an alternate scenario. That perhaps he rediscovered himself and in doing so found again his love for boxing, marking a third, fifth or seventh stage, after rising and falling and rising and falling. Maybe this is the final act of a great champion. Maybe it’s his best one.

Roach laughs. “Most fighters would have quit if they lived through what Manny lived through,” he says. He laughs again. “Manny just keeps going.”

As Pacquiao sits down for breakfast that June morning, photos cover every inch of the walls nearby. Snapshots of his various knockouts line the stairway up to his bedroom. Portraits of his wife and kids hang from the living room walls. Pacquiao drops his head and clasps his hands to pray, underneath a picture of him bowed in the ring before a fight. His acolytes join in as not one but two photographers snap away, growing the collection of memories that add up to a career unlike any other.

Pacquiao pays the cameras no attention. The man to his left cuts his beef and chicken into slices. The man to his right ladles beef soup broth on his rice. Pacquiao begins a history lesson on Jerusalem and the origination of the Muslim religion. He says he learned English by reading the Bible cover-to-cover eight times, the first in roughly 2010.

“We should never forget the past,” he tells his breakfast guests. “If we do that, we will never move forward. We will never heal.”

The acolytes nod. One refills his water glass. Another clears his plates. Try the chicken kabob, he says. Read the New Testament, he says. Learn from the past, he says.

He’s asked if he might fight until age 50, like Bernard Hopkins did. He’s not sure, he says. But he can see his future, his next reinvention. He wants to become the first person to be president of his country and world champion at the same time. And, yes, that sounds both crazy and not implausible, given everything else that happened to Manny Pacquiao, in large part because of Manny Pacquiao. The best and the bad.

It’s strange, in that moment, to think back to Frosted Tips Pacquiao and Up All Night Pacquiao. Crazy to imagine how high he rose and how far he fell and square all that with the man hosting this breakfast, who seems both wiser and content and like he knows he’s near The End and wants to stay in the moment, to remember what he went through and why it matters and how it led to right here. The pictures tell that story, tell why he is still fighting, better than the boxer can.