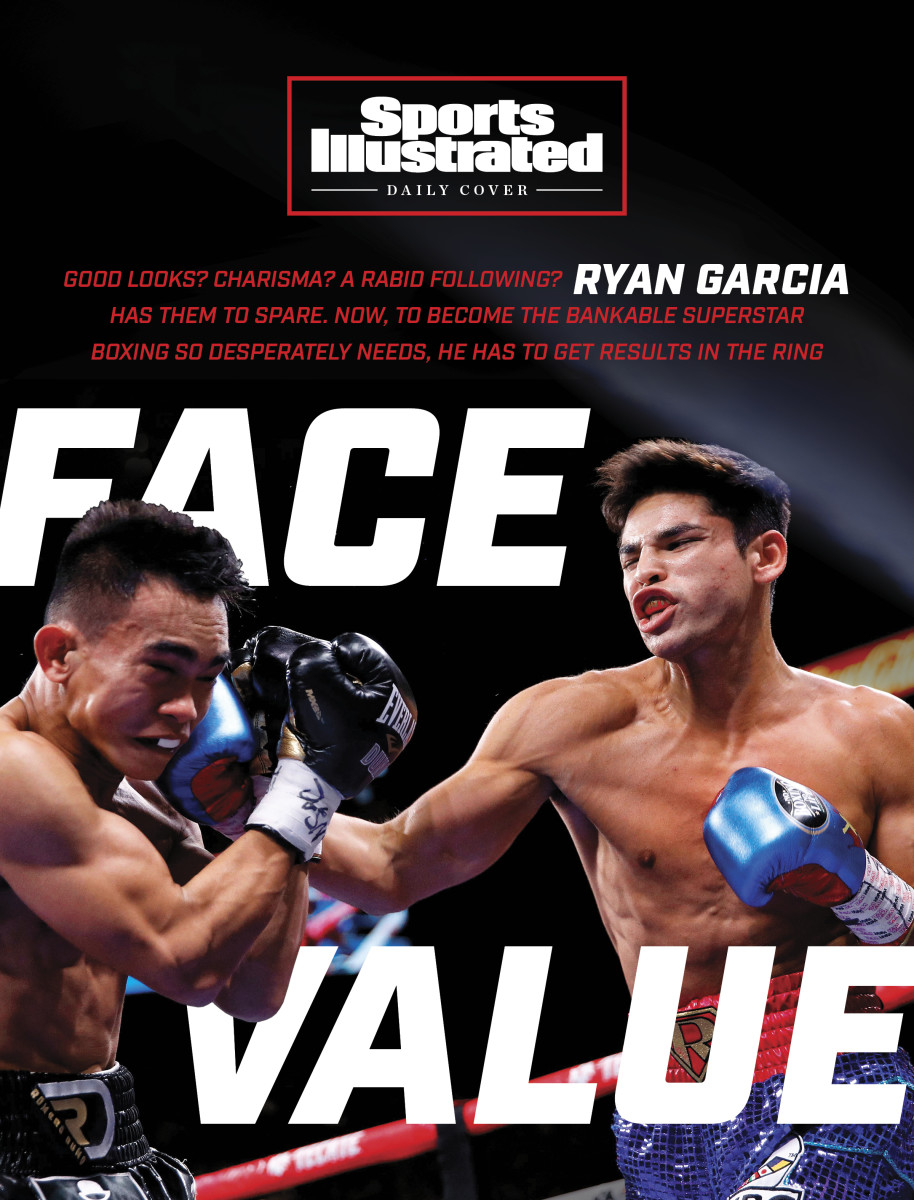

Can Ryan Garcia Become the Face of Boxing?

In his uncle Sergio’s garage in Victorville, Calif., Ryan Garcia sizes up a battered heavy bag. He dips his 5' 10", 135-pound frame toward it and rips a blurring combination into the taped-up leather.

The garage, a sparsely decorated room with cleaning supplies stuffed into a corner and a splash of white paint on the walls, is where Garcia began his journey, in 2005, when as a seven-year-old he was tossed out of the High Desert Boxing Club for lying about his age. “Had to be eight to fight,” says Garcia. “Man, that coach was pissed.”

He fires off another combination, then another—typical stuff. Only these punches are being beamed to Garcia’s 7.5 million followers on Instagram. They have been viewed nearly five million times and collected almost 5,000 comments from fans who range from teenage girls to MMA fighters. “People love what I do,” says Garcia. “They love my talent. They love the speed. So, I mean, if anything, I could just do boxing videos all day and get paid. You know what I mean? But I don’t. Because I love the sport.”

Garcia knows what you see. The wavy hair and the James Dean looks. The social media following—he has 2.9 million followers on TikTok and 450,000 on Twitter—and reality-star lifestyle. You don’t see a fighter, you see a Calvin Klein ad. You see an influencer whose social media feed is filled with videos of the GymShark-sponsored Body Shot Challenge, which features Garcia pummeling the midsections of YouTube stars.

He knows what you don’t see: an upbringing that was, at least by boxing standards, decidedly normal, far from Floyd Mayweather’s being used as a human shield by his father to protect himself from a gunman or Manny Pacquiao’s fighting for change to buy food on the streets of General Santos City in the Philippines. Garcia’s parents were government workers. They met in Los Angeles, at a deli, Lisa, a recent junior college graduate, Henry, a musically inclined Chicago transplant operating his own clothing shop. Garcia’s uncle, Sergio, trained Ryan for two months in that garage before Henry built one of his own, down the street—and eventually took over.

In a battered Chevy van Henry drove Ryan and his younger brother, Sean, to tournaments up and down the coast. Henry encouraged his kids to find friends to crash with; if they couldn’t, he bought pillows and blankets at a Walgreens so everyone could sleep in the van. Come morning, Henry would return them. For trips to Nevada he packed the boys into the family Fiat. “Better gas mileage,” he says. At the end of one trip to Reno, Henry coasted the car on a bone-dry tank into a Chevron station.

Lisa joined many of the bigger trips. For one, to Toledo, Henry bought a car to make the 30-hour drive. It did, both ways—only for the engine to blow out when they got back. “But Ryan and Sean won their tournaments,” Henry says. “So it was worth it.” Eventually, Henry and Lisa became certified referees and judges, enabling them to work the competitions—and save on expenses.

Out of that came Ryan, a 15-time national champion as an amateur, now a 22-year-old pro with a 20–0 record who is the No. 3–ranked lightweight in the world by the WBC. In November 2019, Garcia faced a durable title contender, Romero Duno, and sent him spinning to the canvas with a right hand 90 seconds into the fight. Three months later Garcia needed just 79 seconds to put Francisco Fonseca, a two-time world title challenger, on the mat. It was an impressive win. Even more impressive: the 10,310 fans who packed the Honda Center in Anaheim for Garcia’s first headlining event.

For decades, boxing has seen its standing in the U.S. market diminished. There are myriad reasons. Television fragmentation is one. In the 1990s, HBO was the premier boxing broadcaster. As more outlets entered the picture, promoters aligned with them, siloing their stables, forming de facto leagues that hampered promoters’ ability to arrange high-level fights. A sport with TV ratings that four years ago rivaled, even topped, the NFL and NBA has drifted toward territory occupied by MLS and lacrosse. Pay-per-view, once used exclusively for the most noteworthy of fights, has become commonplace. “Not enough eyeballs are being drawn to our product,” says Lou DiBella, a veteran promoter who spent 11 years as a boxing programmer at HBO. “There’s not a pay-per-view fight this year that would have been one in the mid-1990s.”

Globalization, a boon for other sports, has hurt boxing, with American fans slow to embrace top Eastern European fighters as the U.S. talent pool has dried up. Fighters, inspired by Mayweather and his 50–0 record, began to define greatness by a spotless mark, leading them to avoid tougher fights. UFC, which regularly puts on deeper, more compelling cards, has siphoned off the combat sports fan base. “Boxing is responsible for where boxing is right now,” says DiBella. “No one did this to us. We did this to ourselves.”

For decades fighters ranked among America’s most famous figures—Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, Mike Tyson, Oscar De La Hoya, Mayweather. Athletes with a magnetic pull on casual fans who sold the sport on late-night talk shows and network television. Who thrilled with brilliant in-ring performances that inspired water cooler conversations for days after. “We don’t have a lot of transcendent stars,” says DiBella. “They certainly haven’t been created by what‘s taking place in the ring.”

Boxing has had its share of would-be saviors in recent years, like multiple-title winner Adrien Broner and heavyweight champ Deontay Wilder. But they never connected with fans like Garcia has. His marketing potential is limitless. His social media following can fundamentally transform a boxing audience that traditionally skews older. Now all he has to do is prove that he can box. He’ll get his next chance on Jan. 2, against two-time title challenger Luke Campbell, his stiffest test to date. “He’s got everything, says De La Hoya, who is Garcia’s promoter. “He has an opportunity to be the guy who takes over that throne.”

Eddy Reynoso doesn’t have a deep stable. The consensus Trainer of the Year in 2019 has middleweight Saul (Canelo) Álvarez, boxing’s biggest attraction and arguably its top pound-for-pound fighter. There’s Oscar Valdez, the undefeated former featherweight champion. There’s Andy Ruiz, the ex-heavyweight titleholder. “I don’t like to saturate my camp,” says Reynoso. “Fighters who come to me want to train with me—not work with an assistant.”

In 2018, Reynoso took notice of Garcia, then a rising prospect. He saw the height, tall for the 135-pound division. He saw the speed. He saw the aggressiveness. “He had a style that I like to teach,” says Reynoso. He asked Ramiro Gonzalez, an official at De La Hoya’s Golden Boy Promotions, about Garcia. Gonzalez agreed to help connect them.

Garcia had turned pro two years earlier, shortly after an aborted attempt to make the 2016 U.S. Olympic team. “I wanted to start making money,” says Garcia. “We needed it.” He began direct messaging promoters, including De La Hoya. “Oscar was our hero,” says Henry, whose parents are Mexican. De La Hoya watched some footage of Garcia. He liked what he saw. He invited Garcia into the Golden Boy office. He liked him even more. “He just had that ‘it’ factor,” De La Hoya says. “It was what I felt I had when I was fighting.” He signed Garcia, who won his first 10 fights with Golden Boy by knockout. Garcia always knew he had power. In high school bigger kids, hearing that the gangly Garcia was a boxer, would challenge him. Garcia would get hit. He would hit back harder. “Guys would come at me trying to whip my ass,” says Garcia. “But when I started throwing, they backed down.”

Amateur boxing, though, isn’t about punching. It’s about skill, and Garcia had plenty of it, compiling a 215–15 record. But he could feel the power in his punches being sapped—the hooks that were absorbed by headgear, the right hands that were muted by oversize gloves. “I despised the amateurs,” Garcia says. “I’d be thinking, If I caught the guy with the same type of punch in a real life, I knew I was going to drop him.”

Joe Goossen knew it. In 2016, before he turned pro, Garcia popped into the veteran trainer’s Van Nuys, Calif., gym. Goossen had worked with some great fighters, from Diego Corrales to Shane Mosley to Amir Khan. In Garcia, Goossen saw similarities. “He had that perfect everything,” Goossen says. “Perfect delivery. Perfect power. Perfect balance. Perfect speed. Perfect defense. He just had it all.” When he held a cushion, Goossen says, Garcia’s power “just vibrated through my body.” Garcia asked Goossen about turning pro, but Goossen told him he was already beating better fighters in the amateurs.

By 2018, though, Garcia’s pro career had started to stall. He had a falling out with his father. “He basically fired me,” says Henry. Ryan eventually brought Henry back, but only as an assistant. (In keeping with his son’s celebrity reality, Henry credits Scooter Braun, the entertainment executive known for discovering Justin Bieber, for helping them mend fences.) Garcia struggled in his next fight, against journeyman Carlos Morales.

A change was needed. “My dad and me, we’re not naive,” says Garcia. “We don’t have big egos. We knew that we needed somebody.” Garcia knew of Reynoso—who didn’t? The Mexican trainer had earned acclaim for grooming Álvarez from prospect to a superstar. Garcia marveled at how Álvarez, after fighting off the ropes against Gennadiy Golovkin in a controversial draw, took the fight to Golovkin in the rematch to squeeze out a close decision. He respected Reynoso for devising that strategy. “I thought if Canelo could continue to get better, even at that age [28], as many fights as he’s had, I want to be with somebody like that,” says Garcia. A dinner was arranged. Then a workout. They struck a deal to work together—with Henry staying on as his assistant.

Garcia knocked out his next opponent. Then the next. Then two more. Reynoso has emphasized using distance, which Garcia did expertly in flooring Duno. He has drilled counterpunching. Before Fonseca could connect with a lunging right, Garcia flattened him with a left hook. “He’s showing more patience,” says De La Hoya. “His punches are not as wide. He’s setting up his combinations and, most importantly, keeping that chin down.”

Reynoso has helped. So, too, has Garcia’s new stablemate. On the surface, Canelo and Garcia are unlikely allies. Canelo is serious, introverted even. Garcia can babble on, like a teenager on a sugar rush. “He probably thought I was annoying at first,” says Garcia. In the first camp together, Garcia told Álvarez he would whip his ass. Álvarez eventually warmed to Garcia—“It took a couple of camps,” says Garcia—bonding over skills and a shared work ethic. In the gym the two routinely discuss tactics. “His left hook to the body is some s--- out of a comic book,” says Garcia. Álvarez has become a mentor. When Garcia started a YouTube channel, Álvarez cautioned Garcia not to spend too much time on it. “He told me, ‘Lay off that. We don’t need that,’ ” Garcia recalls. “He told me he thought I was the best lightweight in the world.”

Boxing’s best night of 2020 came on Oct. 17, when inside a COVID-19 sealed bubble in Las Vegas Teofimo Lopez knocked off Vasiliy Lomachenko to unify the 135-pound division. It was a big night for Lopez, who left money on the table to face Lomachenko in a crowdless environment. It was a bigger night for boxing, which has reeled from the pandemic: Nearly three million viewers watched the fight on ESPN, the highest-rated U.S. broadcast in three years. Asked days later about Lopez’s future, Bob Arum, the Hall of Fame promoter, suggested a few opponents: Gervonta Davis, a two-division titleholder; Jose Ramirez or Josh Taylor, who will fight for the undisputed 140-pound championship next year; and Garcia, who hasn’t fought for a major title, let alone won one.

Then again, what is a belt worth? Everybody has one these days. If they don’t, a sanctioning body can create one. Titles don’t convey power, popularity does. DAZN, the subscription-based streaming service that airs Garcia’s fights, doesn’t release numbers but says Garcia leads the way in viewership after established stars like Canelo, Anthony Joshua and Golovkin. “The champions need Ryan Garcia,” says De La Hoya. “Not the other way around.”

That’s why fighters want a piece of him. “There’s so much strength that comes from your following,” says Garcia. “Titles don’t mean nothing. There is no real world champion, in my eyes. Who is a world champion? Anybody can be a world champion. I’m going to beat the fighters that I know are good.”

That begins with Campbell, a slick southpaw who has never been knocked out. Eddie Hearn, Campbell’s promoter, didn’t believe Garcia would accept a fight with a fighter of Campbell’s caliber in exchange for a pandemic payday. “High-risk, low-reward,” says Hearn. Garcia did. “I’ll say this for him,” says Hearn. “He believes in himself.”

If there’s one thing that worries Reynoso, it’s Garcia’s growing profile. “His talent is not the question,” says Reynoso. “But there can be a lack of order in his life. Having order is the key.”

Late last year, Garcia’s tangled love life—he has a daughter, Rylie, with one woman and is expecting a second child with another—was splashed across gossip sites after Garcia was caught kissing a third woman, Malú Trevejo, an 18-year-old TikTok star. “There’s going to be a lot of distractions out there,” says De La Hoya, no stranger to them during his fighting days. “It’s the discipline he shows in boxing that will make the difference.”

But boxing needs Garcia. Skeptics will continue to question his skill set, or dismiss him as more style than substance. Garcia hears it, all of it. De La Hoya admits he doesn’t want to rush Garcia into big fights, but Garcia’s competitiveness has made that difficult.

In February, Devin Haney, a lightweight titleholder, climbed into the ring after Garcia’s win over Fonseca to challenge him. The two had a fierce rivalry as amateurs, splitting six fights. Haney wanted to bring it to the pros. “We’re good fighters,” Garcia responded. “Let’s f------ fight.”

Haney, the champion, is hoping they do fight next year. Garcia says he will let him know for sure. What the new face of boxing wants, he gets.