He Can Knock Out a World Champion From the Comfort of Your Local Library

He arrives in Mexico City on business and settles down in Zona Rosa, a trendy neighborhood of shopping and nightlife—but that’s not how he plans to spend his free time. His destination is the Hemeroteca Nacional Digital de México. The national library. On his day off. To work for nothing, yet with immeasurable reward.

Inside, he heads to the most boring part of the most boring kind of place: a vast warehouse of microfilm and yellowed newspapers and decaying magazines. He woke at 6 a.m. so he could be here when the doors opened, at 9. He dressed comfortably, jeans and a T-shirt, knowing that he’ll go home later covered in sweat and newsprint. He brought water and snacks for lunch, packed by his wife, who kissed him goodbye before he hopped a subway, then another, then a cab. Eventually he strides into the library and nods to the employees, who recognize him after so many visits.

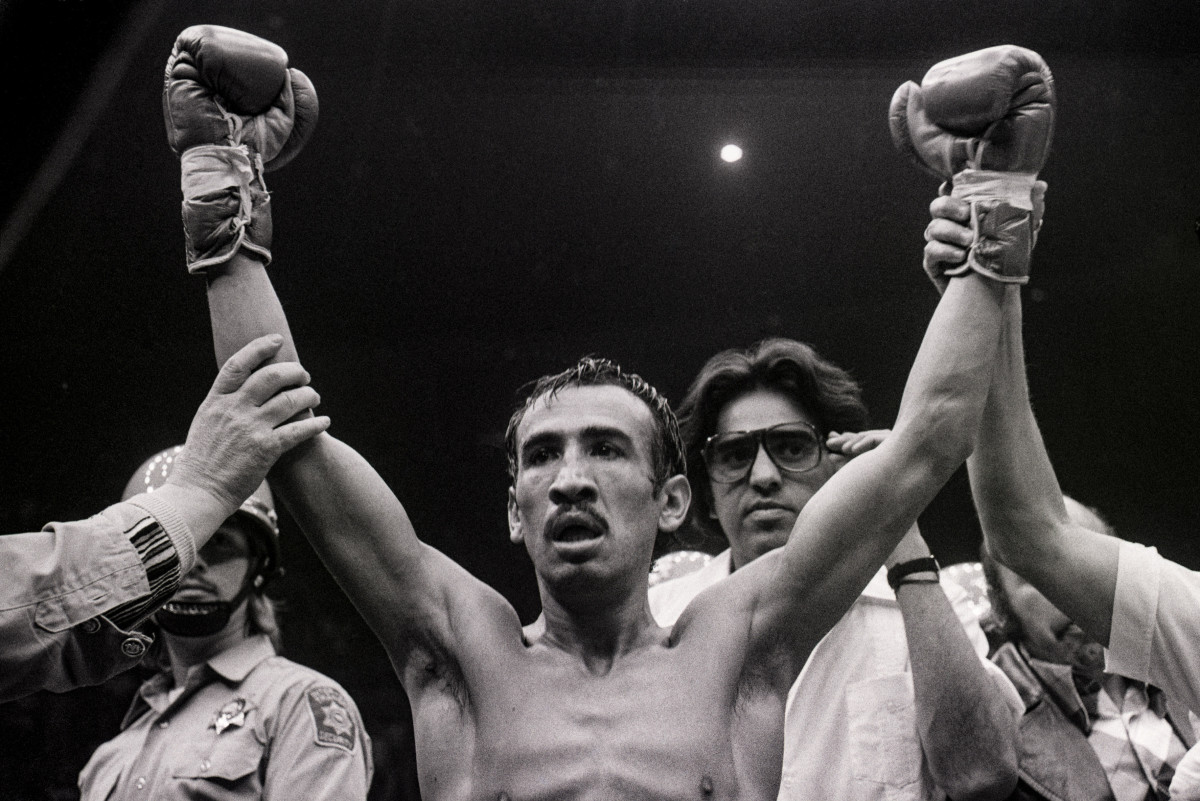

Today he has planned a microfilm hunt. He knows he’ll use the machines on the second, third and fourth floors; he wore sneakers for all those steps. His objective is to mine the early boxing records of Mexico's champions of the past. Men like Jose Becerra and Efren Torres and Raul Macias and Lauro Salas and Baby Arizmendi. They hailed from all over the country, which makes this library, immense and thorough, the perfect place for the tireless Fight Hunter to begin another expedition.

Bob Yalen called his boxing newsletter This Month at Ringside. He tapped out some of the stories on a borrowed typewriter and commissioned other pieces to a teenage freelancer. His dad made copies at work and Bob borrowed money to cover the postage, mailing issues all over the country. Never mind that this was 1975, or that young Yalen, in suburban Connecticut, had not yet completed high school.

In the years since, having graduated cum laude from UConn with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering, Yalen, now 63, has worked as an engineer at various nuclear power plants, as a TV producer (at NBC, ABC and ESPN), as a director of programming and acquisitions (also at ESPN) and as a casino’s director of sports and entertainment (at Mohegan Sun, in Connecticut). He dabbled in local public television and in boxing chairmanship (at the WBC); then he started working for a management company for fighters, MTK Global, where he’s now the CEO. Throughout all of that, though, the spirit of his old high school newsletter stayed with him. Like on his trip to the library in Mexico City.

“I’ve got one of those organized, mathematical, statistical-type minds,” he says. “When I started really falling in love with boxing, I wanted to know all the ins and outs. So I started looking at records.”

That’s how Yalen became an amateur boxing detective, a member in a loose tribe of ring fanatics—like-minded individuals, not some coordinated group—who spend their spare time locked away in libraries, trying to bring life to the most mundane part of a thrilling sport. He has helped correct or add to the records of boxers ranging from Jack Johnson to Jack Dempsey, from “Jersey” Joe Walcott to Willie Pep, from Slugger White to Kid Norfolk.

For Yalen, the path to such a niche pursuit started with that newsletter. For the sake of a given story or stat, he often found himself writing to boxing officials across the globe, trying to ascertain whether a fighter’s record was totally, unimpeachably, to-the-very-best-of-his-knowledge accurate. As he continued this through high school and college, one such fact-checking query landed in the mailbox of a boxing historian in the Bahamas. Yalen had reached out about an active fighter, Elisha Obed, who was being promoted across the globe as an undefeated world champion. And the historian wrote back with a correction: Obed actually lost one bout, and fought another to a draw, early in his career. His future promotional billing needed to be changed.

Yalen had not exactly planned on writing a story—but he did, after uncovering this new info; a young writer, breaking news.

In the aftermath, Obed’s promoter, Chris Dundee, called Yalen and yelled at him. The story was bad for boxing, he said. But Yalen got encouragement, too. A prominent writer, Malcolm “Flash” Gordon, picked up the story and ran it in his own newsletter, Tonight’s Boxing Program. “The sport needs hounds like you,” Gordon told him.

“It was my little breakthrough that [suggested] maybe records aren’t exactly what they’re portrayed to be,” says Yalen.

Across sports, Yalen’s contemporaries are lionized. Baseball, notably, in recent years has celebrated the armchair historians who unearth crucial statistics by combing through old box scores in decaying newspaper clippings. Boxing, though, has never honored the likes of the Fight Hunter, even though his work is, arguably, more important than its parallel in other sports. As Yalen’s friend and fellow searcher Bruce Trampler points out: “Millions of dead brain cells were left on dirty ring mats long ago, in [fights] that were not known to have taken place, except to the few who happened to attend.”

The way the fight hunters see it, those boxers—those prospects and tomato cans, even the most accomplished champions—risked their lives, and they deserve a full accounting of the perils they faced. Beyond that, these historians believe that, in a sport that does not always traffic in honesty, and that exists without any sort of central governing body, there is a deep need for fully accurate renderings of every fighter’s career. For the sake of safe match-making. For fairly setting the value of merchandise and tickets and betting lines. For fairly comparing legacies across time.

It has always bothered Yalen deeply that a fighter, however long ago, could have trained and fought and put himself out there, risking embarrassment and physical damage, but still have received zero credit. Or, perhaps, too much credit. How could that be?

“Everybody deserves acknowledgement,” he says. “The truth.”

At the library in Mexico the Fight Hunter passes through security, where his bag is checked. He plans to spend the first half of the day immersed in old newspaper clippings, the second half combing through microfilm. He finds himself alone mostly, surrounded by silence. He’s not fluent in Spanish, but he has taught himself what to look for in the foreign texts—words and phrases that might indicate a fight result.

He carefully cracks open one of the large bound volumes of newspapers, sensitive to their fragility, some of them as old as 70 years. Eventually, his hands begin to turn gray from the ink, then darker, until he resembles a coal miner after a long shift.

Suddenly, amid all the scanning, he spots something.

For Yalen, a nomad-like career built an important perspective for his hobby. Through decades of working around baseball and basketball and football, he came to realize just how different those worlds were from prizefighting. The ball sports, he observed, tended, historically, to play only in major cities, with iron-clad season schedules and (eventually) televised highlights packages—verifiable proof, in most instances, that a given event had taken place. But boxing operated differently. Events were in major cities, yes, but in much smaller ones, too, far removed from the sport’s mainstream. When it came to records, boxing was the Wild West of pastimes.

Trampler makes this point by way of a brief history lesson. In the U.S., back in the 1920s and ’30s, he explains, small towns often included boxing matches in various forms of holiday extravaganza. On Memorial Day or Labor Day or the Fourth of July, several bouts might be squeezed in between potato-sack races and pie-eating contests. Oftentimes the record-keeping around these events was limited to print ads and fight posters and whatever might be written up, with new stories relying on past stories for things like wins, losses and belts. All of which added up to something of a boxing-bookkeeping catch-22. Few people cared yet about records or legacies, so there were very few recorded accounts of these fights in smaller towns. And because hardly anyone paid close attention to these fights in smaller towns, few people cared whether records and legacies were entirely accurate.

On top of that, most cities and states lacked governing bodies. Nevada, often considered the capital of boxing, didn’t create a commission to oversee the sport until 1941. New Mexico until ’80. Boxing’s record-keeping did not, in effect, become mandatory until roughly 1996, when Congress passed the Professional Boxing Safety Act, which requires that the results of all professional matches will be reported by the supervising commission.

But in the years before that, Trampler says, thousands of bouts in small towns and hamlets went unrecorded, lost “to the great ring in the sky.” He keeps a list of those off-the-beaten-path fight spots and circles them, in the same way that a deer hunter might plot his next trip out into unexplored woods. “Certain goofballs,” he says, full of self-awareness, “are still trying to complete the ring histories of gladiators past.”

Inside one of his books of old newspapers the Fight Hunter discovers the first three bouts fought by Raul Macias, a Mexico City–based bantamweight known as Mouse. Yalen now has dates for fights that previously did not show any. And now that he’s looking in the right place, he starts to find other errors and incomplete records. Mind spinning, sack lunch untouched, he unearths new, undocumented wins for another fighter. He starts to scribble down notes about any name he recognizes.

At 1:30 p.m. his wife sends a text message: Have you eaten anything? The Fight Hunter takes a quick break and, with only a few hours before the cleaners arrive to close the doors, he heads to the second floor, where another book full of news clipping takes him back to one of his favorite boxers. Ruben Olivares. The Fight Hunter confirms several of Olivares’s recorded victories, and he finds one that previously had been lost to time. On its own, it’s a small discovery, he realizes. But the totality of his finds represent something else, something deeper: a full account of hard work, and risk taken, for the people who deserve it.

The Fight Hunter, in his expeditions, might go out looking to learn about a specific boxer—or he might work in reverse, his search focused on a place. Which requires a degree of forethought. In small towns across Nevada, for instance, many newspapers were published only weekly; thus, they often missed results from the pro fights held over a given weekend. But larger dailies in Reno and Las Vegas proper might have carried stories from those bouts in the likes of Elko or Ely or Battle Mountain or Winnemucca. Which is how, for example, he’ll end up at The Arizona Republic, or The Denver Post, or a nearby library, scanning through archives and sending whatever he finds to BoxRec.com, the Wikipedia of the ring.

These pursuits have taken Yalen to the New York Public Library, to view microfilm on champions from Puerto Rico and from the Dominican Republic. They have led him to the Harvard Library, for info on Ghanaian champions; to the Yale Library, for accounts of Nicaraguan boxers. To the British Library. To collections in France, Ireland, Cuba, Argentina, Japan, Russia, Kazakhstan, China, Australia and Canada. Some places have asked him to leave, or denied him entry; they didn’t want him sleuthing, he says. Or he couldn’t overcome a language barrier. There have been times he left with nothing other than a deepened concern over the direction of his life.

Through a search of old newspaper articles in Reno, Trampler discovered that one all-time-great fighter, Henry Armstrong, had among his 150-plus victories KO’d Alton Black in the eighth round in Reno—but not just once. He did that, exactly, twice. Had Trampler not encountered the accounts of both bouts, no one would have known that Armstrong had stepped two times into the ring with Black, a few months apart and in the same location, with the same result. Or that Max Baer had indeed once scrapped in Silver Peak. But in Silver Peak, Nevada. Not in Silver Peak, Nebraska, as had been the record for decades. The Fight Hunter endures to find the lost, but also to correct free-wheeling managers who fed record keepers with creative license, and to rectify details that may simply have been misread at some point, perhaps on account of poor handwriting.

As Yalen travels the world for whatever his day job is at the moment, he always builds in time to stop by the local library. He finds that no one helps more willingly than the friendly librarian in Nobody Visits Here, USA. Any small city across the world, really. He loves whenever the archives have been digitized, but that is rare. Mostly, he spends hours poring over microfilm, his lunchtime apple sitting untouched by his side.

Boxing’s early years have consumed him. Through random spot searches of old amateur records he discovered Olympic gold medalists, such as Eddie Eagan and Eddie Flynn, who had, in fact, competed in professional fights before boxing in the Games, which by rule were open only to amateurs. He found blemishes in seemingly unblemished careers, uncovered unknown losses even by great champions, many of whom did not take kindly to his discoveries. Sugar Ray Robinson, for one, had always been promoted to the public as an undefeated amateur—but Yalen, in microfilm rooms in Albany and Hartford, found old stories about Robinson’s amateur losses.

In turn, he heard from old fighters about his work. Hey, good job! I didn’t think anybody would find those. Some, like current pound-for-pound king Canelo Álvarez, declined to comment on fights that Yalen discovered—all wins, in Álvarez’s case. Others wept. Their efforts had finally been accounted for. Or: Their lie had been corrected. The past is the past, they told him.

But not always.

One time, while searching in Mexico City for stories about boxer Carlos Zárate, Yalen came upon a newspaper dispatch from Monterrey. The wild tale described the theft of a Volkswagen, and how it netted Zárate jail time in 1971. As the boxing records had it, though, Zárate had continued quite the career in the years he was incarcerated, compiling a string of knockouts—knockouts that never happened. Zárate would become an iconic bantamweight champion, but rumors always followed him about a manager who’d invented wins to hide legal troubles.

For years, Yalen says, Zárate denied this discovery, even attempting to avoid Yalen at fights and conventions. Eventually, though, Zárate confessed in person. According to Yalen, the old boxer said he was working on an autobiography; he didn’t want anyone to write about the discrepancy before he did.

Eventually, the two became friends. Yalen even presented Zárate with an award a few years back.

The trip to the library in Mexico City does not yield any earthshaking boxing revelations—nothing that would go viral in this world. But anyone expecting a big news break is missing the point. The Fight Hunter knows his work is long and laborious, mostly sitting and staring. His eyes will burn. His back will ache. But, he says, “it is a passion and a dedication that I do not want to waver from. … Every result is like discovering another piece of history that I am able to bring to the world. … Every fighter—especially the champions—deserves to have his exploits in the ring properly recorded. Because every drop of blood and every drop of sweat they lose is the result of the work.”

When he returns to the hotel in Zona Rosa, his wife tells him to wash his hands.

Fortunately for Yalen, his wife, Libby, gets it. She understands his desire for this one, strange, particular thing. About 10 years ago, Yalen chased a rumor—big news, if true, he knew—that two all-time greats, Sugar Ray Robinson and Willie Pep, had fought each other as amateurs. The future Yalens had just started dating when Bob presented Libby with a strange request. He’d heard about this epic fight, lost to time, that had perhaps taken place in Norwich, Conn., where Libby happened to live. Did she want to go with him to the local library and pore over some microfilm?

The two not-yet lovebirds sat side by side for hours, rifling through old copies of the Norwich paper, The Bulletin. Finally, the Fight Hunter’s future wife announced her first kill: “I saw a mention of that Pep guy.” The fight had taken place, on a barnstorming tour with other U.S. amateurs, inside an actual barn. Robinson fought under a pseudonym, Ray Roberts, explaining, perhaps, why it had slipped through the cracks.

“It wasn’t exactly love at first sight,” Yalen says. And, yet, it kind of was.

As he has bounced from job to job over the years, Yalen’s passion for this hobby never subsided. He stopped writing proper stories at one point, but he kept after the records wherever he went, whenever he could. And boxing officials eventually took notice. Mauricio Sulaiman, president of the Mexico City–based WBC, for example, noted the repeated trips to that one local library. Every time Yalen uncovered something new he would report back excitedly, presenting the picture of, Sulaiman says, “a kid who just found out that Disneyland exists.”

Sulaiman understands the nuances of his sport that make Yalen’s record sleuthing necessary—that make one of boxing’s central tenets, to match combatants of similar size and ability, that much more difficult. It’s a “big, big problem,” he says. He hopes that one day record-keeping will be centralized. Perhaps Yalen and his ilk could create some sort of virtual board. He sighs a deep sigh that speaks volumes about the value of the Fight Hunter's work.

Either way, Yalen will remain on the case. He’ll hunt for every record available. All, that is, but one. On the subject of forgotten fighters, he tiptoes around the fact that he, too, once boxed as an amateur, with little to show for it today. “There are no pictures of it,” he says. “I was never about that.”

More SI Daily Covers:

• Guns, Drugs and Football Thugs

• Bowl Season is Coming. And There Are Only 36 Pylons Left.

• He Should be in High School. Instead He's in the G League. And He's the Future.