A Fighter by His Trade

The boxer rises just before noon, late by traditionally accepted standards, normal for a fighter looking to train his body to peak in the evening hours. He eats a light breakfast—oatmeal, some sliced fruit, washed down with a glass of Himalayan salt water—prepared by a live-in chef who prepares all his meals—before heading to the gym. The gym—his gym—is an abandoned medical supply building he purchased with his brother shortly after both decided to move to Puerto Rico. The floors are covered in ocean-blue turf bearing his nickname (PROBLM CHILD). A pair of standard-size boxing rings take up most of the space with the usual equipment—heavy bags, speed bags, a handful of treadmills—scattered around the rest.

The boxer begins working at 2 p.m.—sharp. It’s 20 minutes on a treadmill to loosen up his legs. Then, in the ring, the boxer straps five-pound weights to his ankles and squeezes three-pound balls in his hands. He begins to move, firing off jabs, swinging looping hooks. Inside the ropes his trainer, a former cruiserweight contender, shouts encouragement. From outside, his trainer, a defensive specialist with names like Fernando Vargas and Diego Corrales on his résumé, observes quietly. After 30 minutes the boxer finishes with hand-eye coordination drills. It’s a light day.

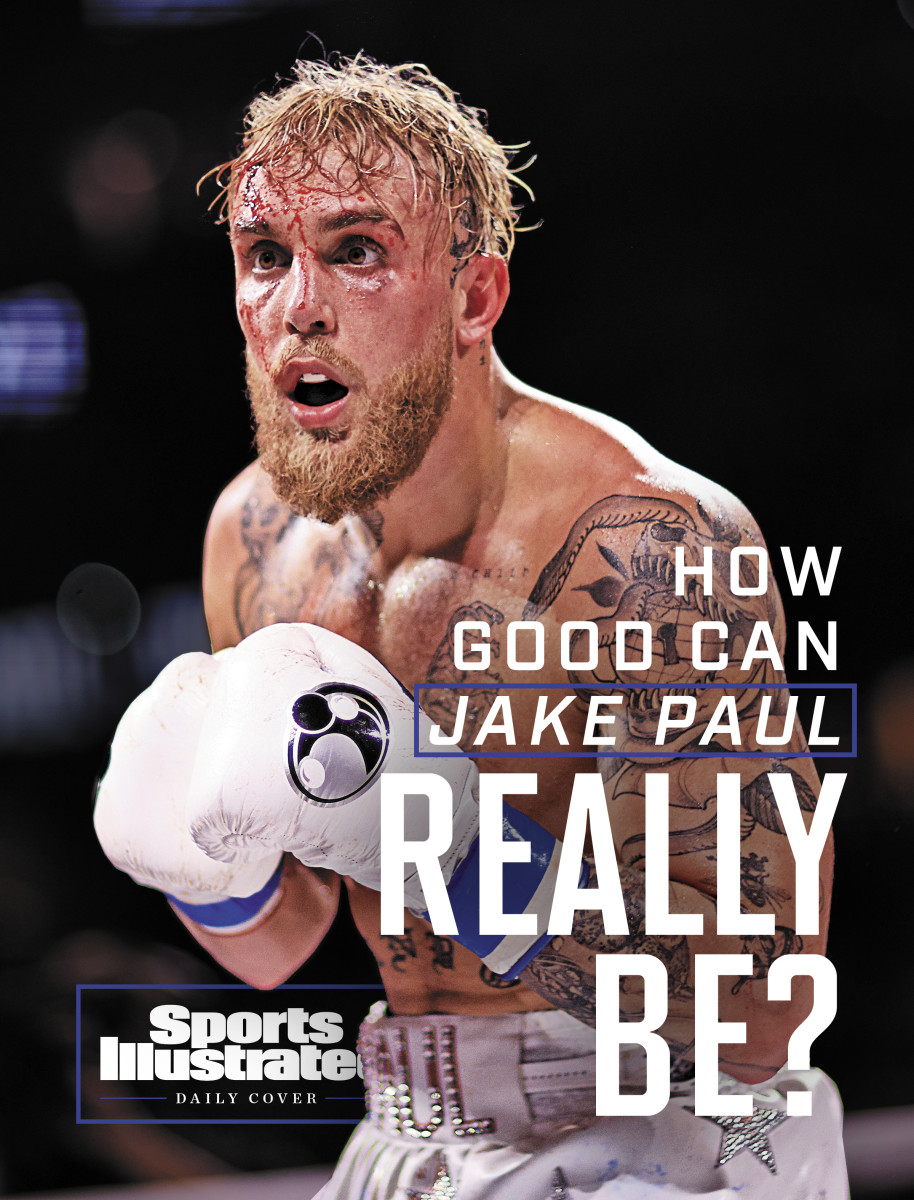

The boxer—Jake Paul—settles into an open space on the ring apron, unfolding his 6'1" frame. He knows the description—boxer—makes some cringe. Paul has been called many things since he made his pro debut nearly three years ago, from “sideshow” (Sergio Mora) to a ”clown” (Gervonta Davis) to “jacka--” (Conor McGregor). He is 5–0 in his brief career, but in the eyes of the boxing lifer none of those wins really count. “He’s not a boxer; he is not a professional fighter,” says Mora. “He stinks.”

Paul shrugs at the criticism. “Jealousy and resentment,” he says. He’ll admit he’s not a traditional fighter. He didn’t earn a reputation in the amateurs or operate in anonymity in his early years as a pro. A successful YouTuber, Paul rode the influencer boxing wave into the pro ranks in 2020. But that didn’t have anything to do with Paul’s performance in the ring in ’21, when he pancaked Ben Askren, a former MMA star, in the first round. Or when he outboxed Tyron Woodley, a former UFC champion, four months later. Last December, in a hastily arranged rematch with Woodley, Paul ended a slow-paced fight with a crushing right hand that sent Woodley crashing face-first to the canvas. Asked about facing backlash for losing to Paul, Woodley said after the fight, “He would literally f--- a lot of y’all up.”

What Paul recoils at is the suggestion he is not a real fighter. “I don’t like it,” says Paul. “I'm a professional boxer. Just my lifestyle, my mentality, what I do every day, who I surround myself with.” Papered all over his gym are printouts of Eddie Hearn, the veteran promoter, with the caption “Wait till he fights a real boxer.” Paul, as he often does, points out he has booked two fights with Tommy Fury, an unbeaten light heavyweight, only to have Fury pull out both times. Last summer, Paul was scheduled to face Hasim Rahman Jr., a once-beaten heavyweight, only to see the fight scrapped when Rahman couldn’t meet the contracted weight. “I’ve tried multiple times to fight a ‘real boxer,’” says Paul. “And I’m going to keep trying.”

On Saturday, Paul, 25, will face the closest approximation so far when he takes on Anderson Silva in a 187-pound catchweight fight. Silva, 47, is best known for his MMA exploits but is 3–1 as a boxer, which includes a win over former middleweight champion Julio César Chavéz Jr. last year. It will be Paul’s stiffest test, one that may answer some of the questions of just how good Jake Paul can be.

Boxing created Jake Paul. Or, rather, it opened up the lane so Paul could penetrate it. The sport is fractured. Promoters are aligned with competing networks, forming de facto leagues. Marquee matchups, once regularly on the boxing schedule, have become scarce. Fighters battle on social media and YouTube more than they do in the ring. In recent weeks, there have been some glaring examples of the sport’s ineptitude: negotiations between Tyson Fury and Anthony Joshua for a December 2022 bout crumbled. Talks for a Terence Crawford–Errol Spence Jr. showdown fell apart. All this dysfunction in the traditional boxing sphere has created a vacuum for compelling content. Paul, along with other influencers, have filled it.

Boxing was never an ambition for Paul. Growing up in Westlake, Ohio, a toney Cleveland suburb, Paul competed in several sports. He wrestled. He played football through his sophomore year of high school where, by his account, he was the best running back and middle linebacker in the school. Most mornings he would rise at 5 a.m. to run and finish the day in the weight room.

But during his junior year, Paul’s focus shifted. Along with his brother, Logan, he began posting on Vine, a since-shuttered short video app. When Logan dropped out of college to move to Los Angeles, Jake went with him. He moved into an $18,000-per-month mansion with other influencers. He scored a role in Disney Channel’s Bizaardvark, where he played a version of himself. “I started with an iPhone, a VHS camcorder and my brother,” says Jake. “That’s all we had. And literally we had to make everything in front of us. No one gave us video ideas; no one taught us how to go viral. We did that; we learned that. And so these fighters don't realize that I, too, earned this f---ing spot. I just did it in a different way.”

Paul didn’t find boxing. It found him. In 2018, KSI, a popular British influencer, called out Logan. He accepted. Jake signed on to fight on the undercard. He didn’t know anything about boxing. Growing up his father, Greg, had a heavy bag in his basement. Occasionally Paul would slip on MMA gloves and whack away at it. “But only for a minute or two,” says Paul. “I’d get tired.” As a freshman, a frustrated Paul slugged a wrestler during a match. “Got disqualified,” says Paul. “But I remember thinking it was very satisfying punching someone in the face.”

With Logan, Jake flew to the U.K. He was matched up with KSI’s brother, Deji Olatunji. The venue, Manchester Arena, was sold out. In his locker room, Jake buzzed as he listened to the roar outside. Officially, the fight was an exhibition. After five rounds, Olatunji’s corner threw in the towel. Jake leaped onto the ring ropes, barking at the pro-Deji crowd which had come to see him lose. “It was incredible,” says Jake. “I’ve never felt anything like it.”

Paul was hooked. His career as an influencer had made him wealthy. He had tens of millions of followers on YouTube, Instagram and Twitter. But it didn’t make him happy. He wasn’t passionate about it. Living in Los Angeles, says Paul, he had become “lost in that lifestyle.” His content was becoming edgier. He got into rap music, releasing personal—and widely panned—diss tracks.

In 2017, Paul parted ways with Disney after he harassed a news crew covering a disturbance at his home. In ’18, a former girlfriend said Paul abused her mentally and emotionally. (Paul said, in a response video, that it was “only fair” that she got to tell her side of the story.) In ’20, Paul was charged with a pair of misdemeanors after he was seen looting an Arizona restaurant during a Black Lives Matter protest. (They were later dropped.) A few months later the FBI raided his home, seizing multiple illegal weapons. (The FBI did not comment on what it found, but the investigation is seemingly over, according to The New York Times.) And in ’21, YouTuber Justine Paradise said that Paul sexually assaulted her. (He called the allegations “100% false.”) His life was spiraling. The more successful Paul was, he says, the more miserable he became. “Boxing changed everything,” says Paul. “Without boxing, my life would be in a different place. And not a good one.”

BJ Flores first met Paul in 2019. A former cruiserweight title challenger, Flores had been recruited to help Paul, then being trained by Shane Mosley, prepare for his pro debut against Ali Eson Gib, a fellow YouTuber that Paul was scheduled to face on the undercard of Logan’s rematch with KSI. Over dozens of rounds of sparring the two forged a connection. “Shane was great,” says Paul. “BJ was just able to explain things to me a little better.” Against Gib, Paul picked up a first-round knockout.

By early 2020, Paul had decided to make boxing his profession. He asked Flores to move in with him. Flores agreed. “But he was like, ‘I’m really going to push you and teach you how to live your life like a professional boxer, to have the schedule of a professional boxer, to be a professional boxer outside of the ring,’” Paul says. That March, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. “We were literally quarantined together,” says Paul, “and all we did was f---ing train for months and months.”

In Paul, Flores found a blank slate. In the gym, they started from scratch. Feints. Upper body movement. A consistent jab. Early on, Flores was careful about who he brought in for Paul to spar with. “Think of it like a toddler,” says Flores. “He had to learn a lot.”

Flores, though, soon discovered he had a lot to work with. Tree trunk legs formed the foundation of a sturdy, 190-pound frame. His 76" wingspan gave him a nice reach. And he could punch. Sparring partners routinely wobbled. Some hit the floor. When Flores started bringing in more established fighters, they left impressed with Paul’s power. “Oh, he has pop,” says Steve Cunningham, a two-time cruiserweight champion who sparred with Paul last year. “He puts the whole house on that right hand. That’s his bread and butter. And it’s legit.”

In November 2020, Paul landed a spot on the undercard of the Mike Tyson–Roy Jones Jr. exhibition. He was matched against Nate Robinson, a former NBA star. He stopped Robinson with a right hand in the second round. Five months later Paul was in Atlanta, facing Askren. Less than two minutes into the first round, Askren was knocked out. Each camp, says Flores, Paul has shown improvement. “He’s like a sponge,” says Flores. “Show him something, and he does it. And if he doesn’t, he wants you to show him over and over until he can.”

Last fall, Flores recruited Danny Smith, his former trainer, to join the team. Smith, a defensive specialist, had been in camp with Corrales and helped reinvent Vargas late in his career. Defense, says Paul, had been “shelling up.” Smith pushed Paul to slip and weave. He taught him to roll with punches and how to counter jabs. He pushed him to become more of a pressure fighter, to take away opponents’ space. “With BJ, I would only shoot three punch combinations,” says Paul. “With Danny, he’s got me shooting eight, nine punch combinations on the mitts, which carries over into sparring. And now I’ll unload six punches on a guy. Just because it’s muscle memory.”

Flores began bringing in better sparring partners. Cunningham arrived last year. He had the usual predispositions. YouTuber. Just trying to get attention. Those vanished quickly. Early on, Cunningham took it easy. Paul wasn’t having it. He told his corner: Tell Steve to turn up. The next round, Cunningham sat down on a body shot. Paul responded with a stinging right hand. “He earned a lot of cool points with me for that,” says Cunningham. “I mean, this kid is freaking rich. He doesn’t need this. But his drive, his work ethic is great. He wants to be pushed. He wants to get better.”

To prepare for Silva, Flores brought in Chad Dawson, a former light heavyweight champion. “I was curious to see what he was about,” says Dawson. After a few weeks of work, Dawson was impressed. The skills were respectable. “He knows exactly what he is doing,” says Dawson. So, too, was Paul’s work ethic. “Not only was he doing the right things in the ring, he was doing what he needed to take care of his body outside,” says Dawson. In between sessions, Paul would pick Dawson’s brain. “He was always asking questions,” says Dawson. “About positioning, certain movements. He’s always looking to set up shots.”

Against Woodley, he did. On the surface, the right hand that put Woodley down last December looked like a lucky—albeit clean—punch. But Paul’s team pointed to the previous minute, where Paul jabbed and feinted at Woodley’s body, drawing him into dropping his left hand. “Lucky? Bulls---,” says Flores. “Jake set him up. He worked hard on that shot. There’s no luck in any of this.”

What’s ironic about the criticism of Paul is that his early career path is a familiar one. For decades boxing matchmakers have built young prospects early against overmatched opponents. Mora’s fifth pro fight was against George Moreno, who had exactly as many wins (zero) as Woodley did. James Franks, whom Davis faced in his sixth pro fight, entered the ring with a record of 2-8-1. It wasn’t until Canelo Álvarez’s 13th pro fight that he fought an opponent with a winning record. The difference: Those fighters gained experience in empty buildings on untelevised undercards. Paul is doing it in packed arenas headlining pay-per-views.

But he is doing it. Paul doesn’t need boxing. Yes, it has allowed him to make a lucrative pivot—he earned $40 million in boxing last year, per Forbes, and tells Sports Illustrated that boxing represents his most significant income—but he is rich in a way that no 5–0 boxer has ever been. Last year, he earned $5 million from YouTube alone. His promotional company, Most Valuable Promotions, co-promoted Katie Taylor’s fight against Amanda Serrano, arguably the biggest fight in women’s boxing history. He recently launched Betr, a sports gambling app, and, in August, debuted a weekly sports talk show. That feed alone has 2.4 million YouTube subscribers.

He doesn’t need to fight real boxers, either. Typically in boxing the tougher the fight, the bigger the payday. Paul’s financial model is inverted. His biggest checks won’t come against Artur Beterbiev, the unified light heavyweight champion, or Lawrence Okolie, a titleholder at cruiserweight. It will come from fighting Nate Diaz, the brash ex-UFC star. Or matching up with KSI, who after knocking off Logan could go after Jake next year. He could rake in more revenue in boxing next year without ever facing a traditional boxer than he ever could by fighting the champions or top contenders in his weight class.

But he wants to. “I do want to get at least one belt,” says Paul. “A legitimate world championship belt, which I know is very tough, and a lot of people will never be able to achieve that. But I know I can.” If he beats Silva, Paul says he will look to reschedule a fight with Fury. He won’t fight Rahman again (“f--- that guy,” says Flores), but he’s willing to face someone on that level—even if it means taking less money to do it. He says he wants five or six more fights before he chases a 175-pound belt. “Making money is not what I intended to do in this sport,” says Paul. “It’s been a byproduct of what I’ve accomplished. But it’d just be funny to me. Yeah, I was a YouTuber and Disney kid and all of you said I wasn’t a real boxer and I became the world champion.”

How Paul handles adversity is an open question. The tougher the fights he takes, the more risk there is of losing. Undefeated fighters are motivated. Inspired. But losses can be draining. Will Paul be willing to put in the work to rebuild? Or will he slip back into the world of promoting, YouTube and sports gambling?

“Let’s say if I ever lose...,” says Paul. “I think people would like me more if I lost, because they would get to see a different side of me that I haven’t had to show because I’ve just been winning. So I’m not going to be humble; I’m not going to go back and into hiding and work on myself and emerge a new person or whatever. But a loss I think would push me in that direction. And it makes the story a whole lot [more] interesting.”

It could come Saturday. A win over Silva won’t impress everybody. “He’s fighting a 47-year-old man,” says Mora. “47! Jake Paul needs to be fighting a boxer. I don’t care if it’s an 0–5 boxer. But a boxer. Then we can talk.” There has been a noticeable lack of animosity between Paul and Silva during the buildup. Paul calls Silva “a f---ing legend.” At a press conference last month, Paul flashed a picture of a 30-something-year-old Silva posing for a picture with Jake and Logan (the three would recreate the photo onstage later). Paul’s team has warned not to take the affable Silva lightly. “Don’t worry,” Paul says. “I’m going to do what I do best. Which is fight.”

• He Survived a Shooting at His High School. Returning Has Been, at Times, Unimaginable

• James Wiseman Is in a Golden State of Mind

• All Eyes on Zion Williamson