On Anniversary of Joe Louis-Max Schmeling Bout, a Writer Reflects on the Historic Event

Before he became heavyweight champion of the world, Joe Louis’s mother forced him to play the violin. Or so she thought. She handed over a quarter a week for lessons. But he never showed up, choosing to train at the gym nearby instead.

In 1933, Louis entered his first Golden Gloves tournament. After he notched a couple upsets, his best friend’s mother congratulated his mom on her son’s boxing success. She had no idea. “And that was the first fight Joe ever had with his mother,” says a man with almost three-quarters of a century’s worth of sports history in his head.

This man knew Louis, eventually. He is Jerry Izenberg. He is still writing about sports and lives and how both intersect. This would be less impressive if his career was shorter than the lifetime of most professional sports franchises. But it’s not. He believes the history of the world can be told through competitions. Louis is heavy-hitting proof.

When asked how he’s doing, Izenberg chuckles over the phone. “You don’t ask a 92-year-old that,” he says. “Who can really say?”

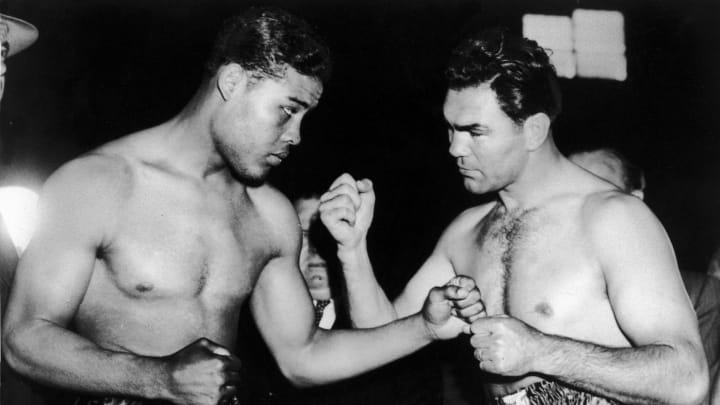

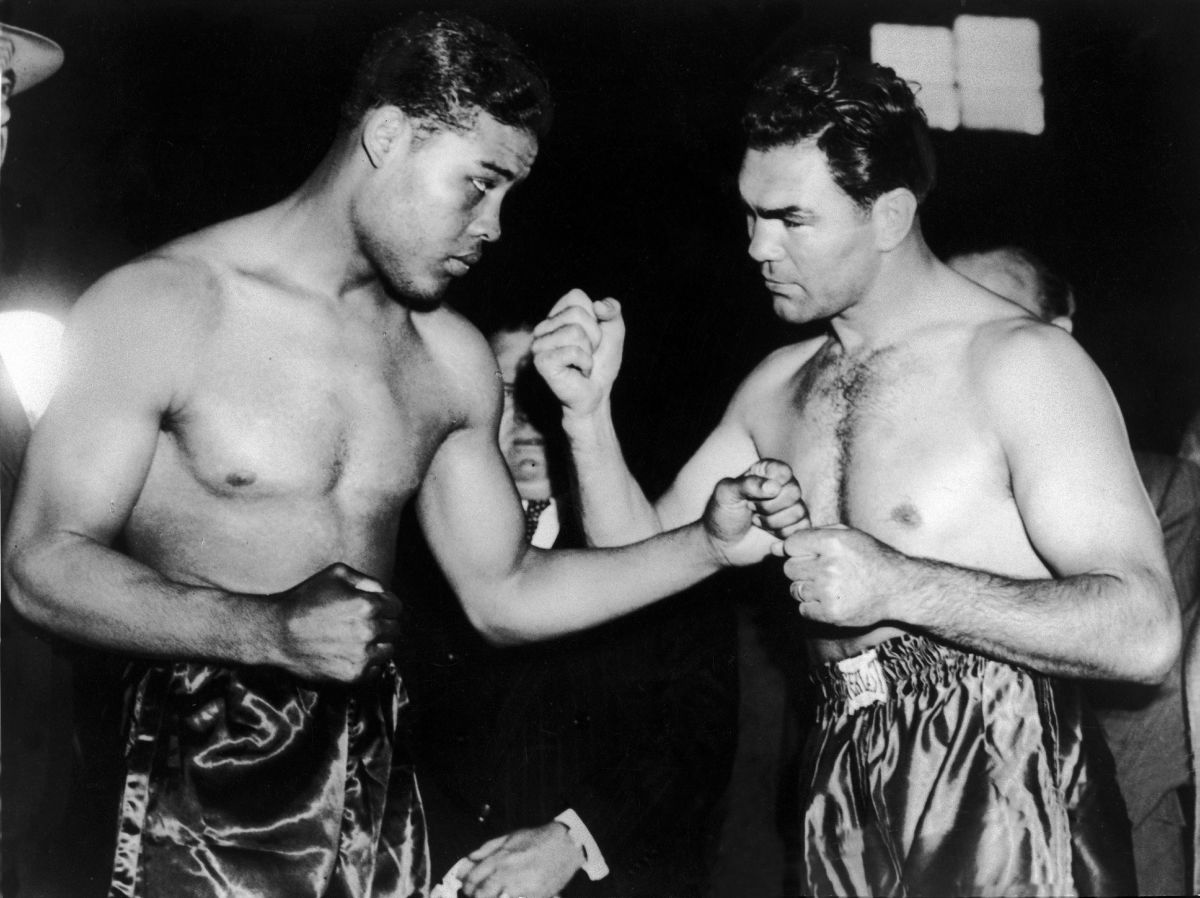

Izenberg might be the only sports writer alive who can speak to the 85th anniversary of a seminal athletic event in sports and American history. He was 7 on June 22, 1938, the night Louis, the boxer who might otherwise have been a violinist, fought a rematch against Max Schmeling for the heavyweight title and much more. Louis fought for revenge, after Schmeling hand-delivered Louis first pro loss, by knockout; he fought to solidify his standing as heavyweight champion once more; and he fought, whether he wanted to or not, for democracy.

Izenberg covers this bout—arguably the most significant sporting event of the 20th Century—in his new memoir, Baseball, Nazis & Nedick's Hot Dogs: Growing Up Jewish in the 1930s in Newark.

His father, Izenberg says, considered the family’s supper table a personal pulpit—and Dad allowed for two conversation subjects: baseball (due to his minor-league career) and “Adolph Hitler or the Nazis” for obvious reasons. Izenberg’s father told his children about the start of Hitler’s isolation, persecution and murder of Jews, with the Nuremberg laws Hilter introduced in 1935. Izenberg and his family lived in New Jersey, about 10 blocks from the border with Irvington, N.Y., where the state headquarters of the Nazi-affiliated German American Bund was located. The sizable Jewish population in Newark had not yet fled. “And the traffic across that border,” Izenberg says, “was often very violent.” He spins into mobsters, riots and the Minutemen, a group of Jewish boxers recruited to work with the FBI to fight Nazis.

“In the morning, in those days, newspapers used to put out extras,” he says. “The feds arrested 15 German-Americans for espionage. That was the morning of. You could imagine what the crowd was like. Looking back, I think it’s a miracle there wasn’t a ‘bigger’ fight that night.”

One other thing. There are always those, for a man with 85 years of stories and seven decades spent writing them. He starts with a favorite ritual. An uncle would pick him up in a Cadillac, take him to the countryside and drive as fast as possible. Izenberg says they referred to the wind the car whipped up as Jewish Air Conditioning. On one of those trips, his father asked the uncle to pull over. He wanted to show young Jerry something. They got out of the car, in front of a large hotel, with a billboard placed on the front lawn. “Read that to me,” his father said.

This is a restricted hotel, the sign announced. No dogs or Jews allowed.

This was the America that Izenberg grew up in—the best possible time, he says, despite everything else. It was also the backdrop for Louis-Schmeling II.

Also, there’s one more thing you have to know. Always. There were two German American Bund camps in North Jersey, Izenberg says. The men trained in storm trooper uniforms. The children wore Hitler youth uniforms. There were rifle rangers. “That sets up the mood.”

That night, Izenberg’s father mentioned the murder mysteries Jerry and his sister typically listened to after dinner. They wouldn’t be able to that night, Dad said. The living room would be packed, the radio tuned to the fight. His mother didn’t like this idea much, citing bedtimes. This is a more important lesson for them. His father placed both arms on Jerry’s shoulders, which always indicated he was serious, and told Jerry that Louis was fighting for “his people” and “fighting for ours.” He described Schmeling as a Nazi, which doesn’t seem to be accurate—Schmeling was German but denied any affiliation, including to Jerry, later, directly; although he seemed to enjoy the perks the party proffered for his triumphs.

The Izenbergs gathered around the radio, same as millions of other Americans. Some estimates placed the audience at between 60 and 70 million in the U.S. alone and over 100 million worldwide. Roughly 80,000 packed into Yankee Stadium, the same venue where, two years earlier, Schmeling had handed Louis that first loss.

In the interim, Louis won the title. He would make $350,000 to defend it and democracy, while Schmeling banked half that total. What most didn’t know, Izenberg says, is that neither champion was truly motivated by what history insists motivated each of them. Both understood the geopolitical backdrop. Only two years earlier, Berlin staged the Summer Olympics, an early foray into sports washing. But what they wanted, the fighters themselves, was simpler. Schmeling wasn’t fighting for Nazi Germany; he was fighting to win the belt back. Louis wasn’t fighting for democracy, not intentionally; he was fighting to retain the crown.

Radio announcer Clem McCarthy painted the ring walks for those millions of listeners. The din at Yankee Stadium nearly drowned his voice out. The streets in major U.S. cities had all but emptied, as families and friends clustered around radios of their own. Jews prayed that Louis would win; violently, if possible.

And he delivered. From Izenberg’s memoir:

Louis ambushed his man. Seconds into the opening round, Schmeling, his right hand cocked, backed off from the stalking champion, and Louis attacked. His punches came in bunches—mainly left hooks. They snapped Schmeling’s head back. Then a right cross landed and Schmeling seemed to fly backward into the ropes. That was just one minute into the fight. Schmeling was down.

The memories of that night, now almost 85 years old, remain vivid, even now. Izenberg recalls his father standing up at different points, throwing air punches and hollering louder with every blow landed by Louis.

Twenty-five years after the rematch, Jerry would meet a man in Grambling, La. The man’s name was Calvin Wilkerson. He was an entrepreneur, one of the city’s first Black residents to serve on the Parish School Board. Izenberg told Wilkerson about his father’s reaction on that long-ago night. Wilkerson told him everyone who listened to fights in Grambling reacted similarly. But three months after Louis-Schmeling II, he added, a young Black man had been castrated and lynched six miles up the road, then left for dead, hanging from a tree. Wilkerson asked Izenberg if his father had been cursing while throwing those air punches in the family living room.

Only every third word.

“Me, too,” Wilkerson responded. “We heard the fight up the street in the back room of Gallo’s Barber Shop, and we stayed there all night. We couldn’t go home. Every time Joe won, the Klan was out there riding in pickup trucks and carrying shotguns.”

Izenberg still thinks about that night, Louis’s triumph and the country he (supposedly) fought for. Izenberg considers heroes and narratives, history and how it’s shaped.

One more thing. Izenberg went to Louis’s 50th birthday, where everyone gathered in a banquet room inside a Las Vegas hotel. Writer and boxer had met years earlier, when Izenberg wrote for the Paterson Evening News. “He was refereeing a wrestling match in the Paterson Armory, which was a dump,” Jerry says. “And we’re sitting in the dressing room. And the shower’s leaking. And I said, Do you think you’ll ever get even on your taxes?”

Louis leaned down and asked Izenberg to look at the top of his head and then asked what he saw. Not much. “It’ll refill with hair when they start to give me a break,” Louis said.

History is complicated; narratives, sanded more and more palatable over time. None of that changes the significance of Louis’s victory, what it meant to others and to him.