A Lost Art: Cursive Writing and Athlete Signatures Could Be Making a Comeback

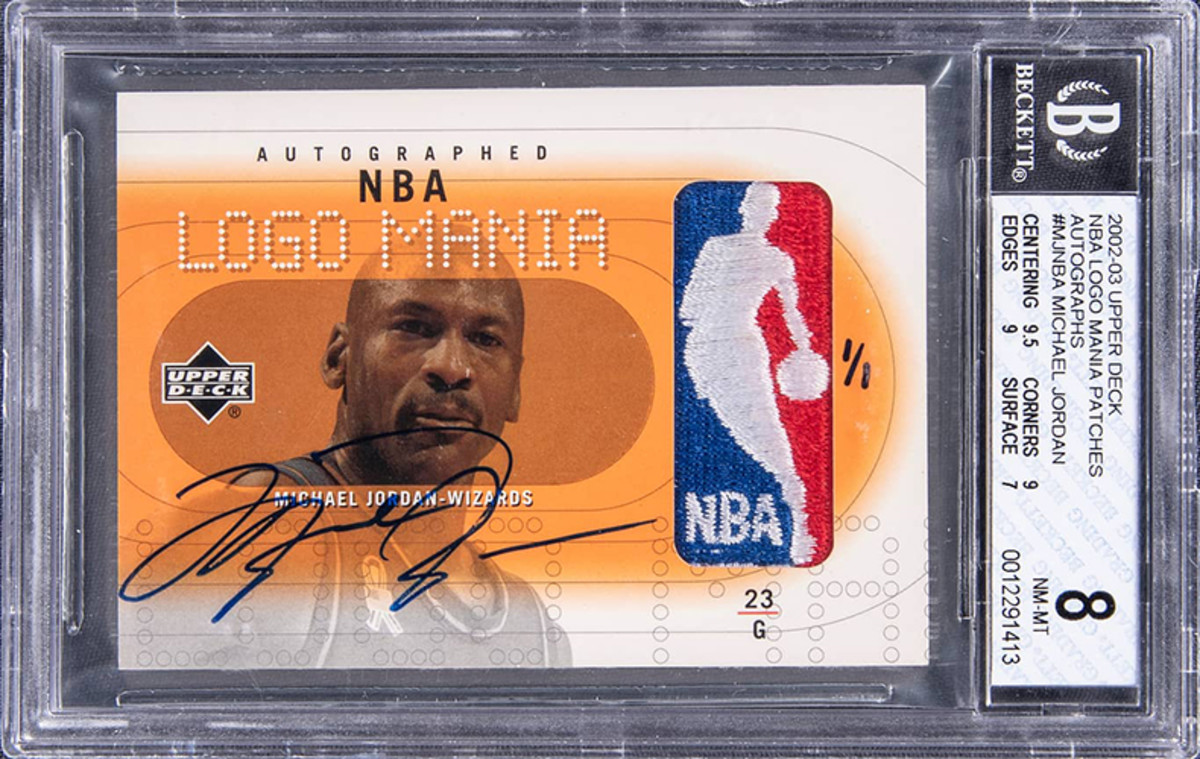

As an autograph collector, I’ve always found it fascinating to compare athlete signatures. The “half moons” that Mickey Mantle incorporated into his moniker later in life are legendary. The sweeping elegance behind the Splendid Splinter’s (Ted Williams) signature is another marvel to study. The “M” that Michael Jordan morphed into a “23” at the start of his autograph is another great conversation piece for anyone studying Air Jordan's signature.

As a collectibles writer, I’ve penned articles showcasing the beauty, elegance and readability behind the signatures of yesteryear’s superstars. But I find it difficult to compare them to the less-than-legible scrawls of many of their present-day counterparts.

Think Sandy Koufax to Clayton Kershaw. Bart Starr to Patrick Mahomes. Larry Bird to Luka Doncic. I would stare at the current athletes’ scribble and ask myself: “Why don’t they care about their signatures? Is it just outright laziness? And when exactly did initials and a jersey number suffice for an autograph?”

I interviewed several hobby dealers and auction house representatives about this blatant deterioration of signature writing affecting many of today’s stars. I wondered if the overwhelming number of requests they get, and appearances they make, simply force them to find an easier way to complete the assignment.

An athlete is sometimes asked to sign as many as 1,000 labels for a trading card manufacturer in one sitting. That could be a daunting task for anyone.

One of the most intriguing responses I got came from Brian Drent, the president and CEO of Mile High Card Company in Denver, whose company sells thousands of signed items every year. “My best guess is that penmanship is really not taught at the same level [nowadays] and currently no one takes pride in their penmanship like they used to,” he said.

Stemming from Drent’s hypothesis, I did a deeper dive into this alluring topic. What I discovered almost makes you want to give a pass to many of today’s stars when it comes to writing their names.

Schools eliminate cursive

With the emergence of computers, by the turn of the new millennium, the need to learn cursive was falling by the wayside. Sometime over the last 25 years, less and less emphasis was being placed on the physical execution of handwriting while more significance was put on particular types of writing including argumentative, informative, and narrative.

The flowing manner and continuation of cursive letters gave way to keyboards and keystrokes. Font types like Times Roman, Arial and Helvetica slowly became the norm. The departure from teaching cursive was a gradual elimination due to a lack of interest and necessity.

“I think it was largely abandoned due to the lack of time and patience in today’s schools,” said Debi Irish, a longtime grammar/writing tutor and instructional aide who has worked in schools ranging from Scholarship Prep and Oceanside High to MiraCosta College, all in North San Diego County. “Cursive writing takes thought, practice and patience in an otherwise very fast-paced environment. It also requires consistency in order for students to learn it.”

In 2010, as interest declined further, more than 40 states adopted the same standards for English and math: the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). These didn't include cursive writing as part of elementary schools required curriculums.

Kym Tobias, a sixth-grade teacher at Central Elementary School in National City, California, shared this perspective: “Because of the increased use of technology today, typing skills are probably seen as more relevant. Also, the Common Core standards are so rigorous that cursive takes a back seat to instruction in areas like math, science and literature.”

What’s been the result?

“I’ve noticed students having trouble writing their names,” said Irish. “I feel the most important aspect of learning cursive is to allow students to see the connection, continuity and flow of words — something you can't see in word processing. I absolutely consider cursive writing a lost art.”

Something else that occurred was the sizable collapse of legible signatures across the country. From driver’s licenses and passports to autographed trading cards and memorabilia, the ability to deliver an elegant signature was slowly disappearing from the landscape.

For example, do side-by-side autograph comparisons showing Hall of Famers like Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle and Harmon Killebrew to current top ball players like Kyle Schwarber, Mike Trout and Freddie Freeman. They’re as different as night and day when it comes to style and readability. But now we know, if nothing else, it’s not based solely on the players’ indifference.

“I think teaching cursive is important for practical purposes,” said Tobias. “Kids need to be able to sign their names on important documents as well as access [and read] historical materials. This is why I still teach them to write their names in cursive at a minimum.”

Betsy Link served for 20 years as the Communications Officer for the Lumberton Township School District in New Jersey. Four years ago she started teaching fifth grade full time at the Bobby Run’s School, also in Lumberton. She concurs with Tobias.

“Almost all writing we do is now on Google Docs, so kids are typing assignments and turning them in electronically via Google Classroom,” she explained. “When I moved to fifth grade, I started encouraging my students to voluntarily practice their cursive, especially the letters that are in their names. I tell them they are going to need to have a signature when they start signing legal documents.”

All is not lost

Although not a required part of the Common Core State Standards guidance, each state and U.S. territory can choose whether to teach cursive writing. Interestingly, in just the past eight years, more states have started reimplementing some form of cursive writing in their elementary schools.

According to mycursive.com, a website that tracks cursive writing requirements nationwide, 14 states in 2016 required schools to teach cursive writing. During the 2018-19 school year, that number increased to 19.

Just this past October, California Governor Gavin Newsom passed a new law requiring the teaching of cursive writing in grades one through six. It was authored by California Assemblywoman Sharon Quirk-Silva, a former teacher of 30 years.

Now, a total of 23 states require some form of cursive writing instruction while five more (Kentucky, Minnesota, New Jersey, Nevada and Wisconsin) have pending legislation on the topic.

Beyond providing someone with the ability to write their name in flowing script letters, advocates for cursive writing claim there’s a direct correlation of benefits for young students. These include building fine motor skills; assisting with cognitive development; and stimulating and creating synergies between different hemispheres of the brain that involve thinking, language and memory.

“It’s important for students to learn cursive because it can only benefit their ability to comprehend, concentrate and input/output information by using their brains,” added Irish. “When synapses don’t fire, children don’t learn.

“Students react in amazement when they get cursive handwriting down. They are more self-confident knowing that they succeeded. I had a student recently ask me to check his homework for a cursive writing assignment. As his instructional aide, I told him his work was getting much better, and he smiled.”

What does this all mean for collectors? That in approximately 10 years, a new generation of players making their professional league debuts will be able to sign their trading cards with confidence, conviction and — hopefully — a higher degree of readability.