Better Than Zeus: Driven By His Dad's Success and Failure, Life and Death, Orlando Brown Jr. Aims To Be His Own Legend

NORMAN, Okla. — In mid-August, during a break between toilsome two-a-day practices, Oklahoma players gathered in the team room for a speech on schoolwork. There are more exciting topics to command the interest of weary athletes. But Jaye Rideaux, one of Oklahoma's assistant directors of academic advising, had decided to go big with the presentation: A few days earlier, she approached Orlando Brown Jr., the team's 6' 8", 340-pound lodestar left tackle, and encouraged him to speak.

The Are you sure you have the right guy? look Brown shot her belied how astute a choice it was. He barely qualified academically for college and nevertheless would begin the fall as a power-conference starter with a GPA around 3.0. He had a story worth telling. It just wasn't only his story he told.

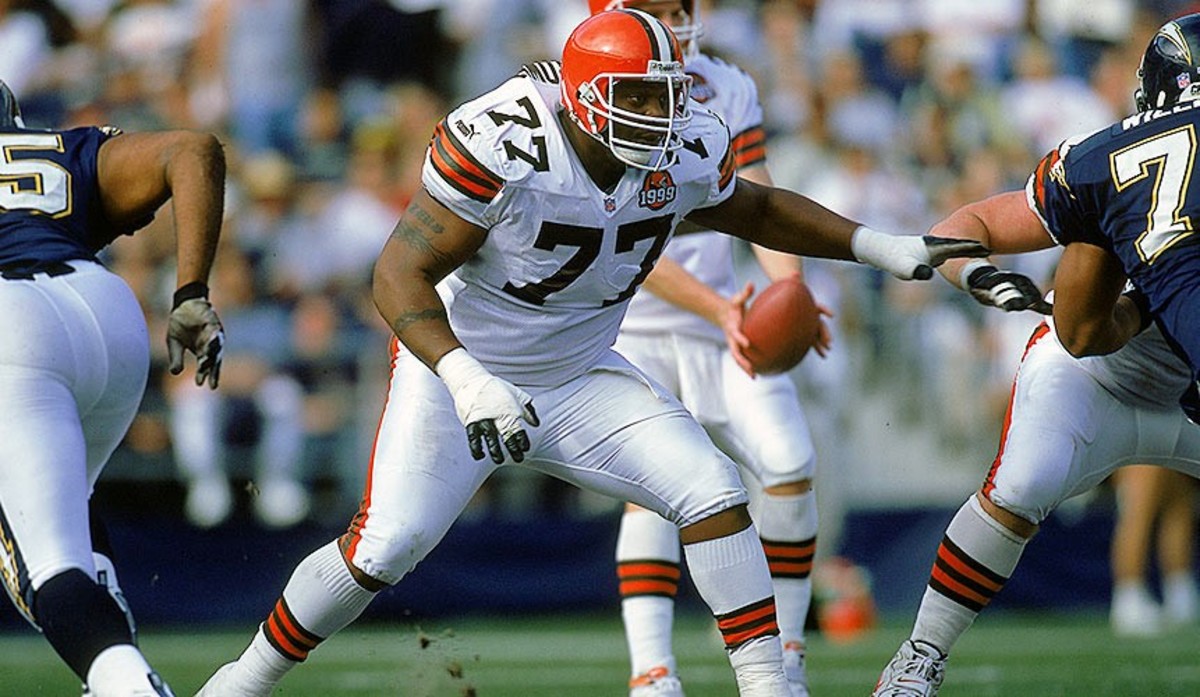

He spoke about his father, Orlando Brown Sr., who played at South Carolina State from 1988 to '93. It was a time, Orlando Jr. noted, that some people went to school for one thing, and that thing wasn't school. Orlando Sr. went on to an NFL career that spanned 12 years, and at one point the 6' 7", 360-pound behemoth nicknamed "Zeus" was among the league's highest-paid linemen. But he also left college without a degree. Football was life. And when football ended, when there were no more games or meetings or workouts, he struggled to find a job without that diploma.

Money was there—from his pro contracts, from a multimillion-dollar settlement with the NFL after a penalty flag hit Orlando Sr. in the eye in 1999 and cost him the next four seasons, from the Fatburger franchise he bought—but a degree would have made things easier. At this, the younger Brown pivoted to himself. His father died, at 40, on Sept. 23, 2011. Orlando Jr. stopped going to class. He stopped caring. He was a teenager putting his anger and pain into a game. Football was life, and his academic cliff-dive nearly cost him that, too.

Orlando Jr. implored his teammates: Don't fall behind. Don't allow what happens in life to threaten everything you worked for.

As the son of Zeus sits in a soft chair inside Memorial Stadium a couple weeks later, he explains why he said what he said. His father did great things, and his father made mistakes. So Orlando Jr. promised himself he wouldn't repeat the failures. Despite the body and bloodline presaging a long NFL life, he prioritized his degree. He sees it as the best way forward: He is his father's son. He can be something else entirely, too.

"The thing he always preached was, 'Be better than me,'" Orlando Brown Jr. says. "Be better than I was. In all aspects of life."

STAPLES: The Tess Effect: Looking at the numbers behind college football's magic man

*****

A season-opening flop against Houston realistically leaves Oklahoma with no room to lose when Ohio State visits Norman on Saturday, nor anytime after. That will require resolve and orneriness from all of the Sooners, not just their gargantuan left tackle. It is nevertheless a plus that Orlando Brown Jr. has a long history with both qualities. He lost his father, his direction and, ultimately, a scholarship to Tennessee before he scraped back and made it to Norman just before preseason camp in 2014. Since, he has ascended from out-of-shape, unbridled novice to adroit 15-game starter and burgeoning star.

"He had [two ways] to go," Oklahoma offensive line coach Bill Bedenbaugh says. "Either flame out and bust or become a really good player."

Brown's size and equally considerable mean streak augured well, though this nastiness did not come naturally. He didn't play football until the sixth grade, and only then because, in tears, he begged his father to play. He was huge (300 pounds already) but soft; the younger Brown remembers catching his first cramp and wondering, What is this?

Still, he grew to love the one-on-one battles, and a threat from his father finally hardened him in eighth grade. Brown was a well-off suburbanite on a grassroots All-Star football team with hard-bitten city kids from Baltimore when Orlando Sr. issued an ultimatum before a game against a team from south Maryland: If you don't play physical today, I'm leaving.

On the first snap, a 400-pound Orlando Brown Jr. lined up across from a kid he guesses weighed about 370 pounds. "And man, I drove him about 30 yards and just dumped him," Brown says. "I remember after I dumped him, getting back up and jumping back on top of him. And they threw a penalty flag."

Orlando Sr., meanwhile, threw a party.

He jumped up and down on the sideline, waving a towel and screaming, Yeah, 'Lando! I see you! "If you've got that dog, people play you differently," Orlando Jr. says. "People don't want to run down the middle of me. People know, hey man, if this dude gets his hands on you, he's going to finish you, and you don't want to be in that position. That moment right there, I learned."

By his sophomore year at DeMatha Catholic High in nearby Hyattsville, Md., college programs began to show interest. Orlando Jr. was no longer the unconcerned tyke who played red light/green light in stadium suites while his dad toiled away on the field. He had size and attitude like big Zeus. He looked like a nascent force all his own.

And then came the six days that left him without a father, ending on a cold and rainy Friday.

"I can tell you the story if you want me to," Orlando Jr. says, leaning over the armrest.

*****

Tom Hauck/Getty Images

It begins with Orlando Brown Jr.'s first unofficial recruiting visit to a college campus, featuring Maryland's Sept. 17, 2011, home game against West Virginia. His father intended to join but declared himself too ill to make the trip. Just call me when you're done, Orlando Sr. said.

The plan was for Orlando Jr. to return to his mother's house after the Maryland tour, but he detoured from College Park to his father's place on Baltimore's Inner Harbor instead. On Sunday, the two Browns ate at Ledo's Pizza as the Ravens prepared to host the Titans. Somehow a lamentable yarn about Jevon Kearse beating Orlando Sr. on a long-ago pass rush resurfaced. Orlando Jr. recalls his dad wasn't too happy about that.

On Monday morning, Orlando Sr. dutifully played chauffeur for the 45-minute haul to DeMatha. (During the school year, Orlando Jr. usually bunked at his grandfather's home in Washington, D.C., about 10 minutes from school.) Father and son climbed into a black Rolls-Royce Phantom, a ride tricked out down to the Rs on the wheel rims that didn't move. At the end of the trip, Orlando Brown Sr. gave his son $165 to cover lunch and post-practice spending money for two weeks. Have a good day, he said. Orlando Sr. laughed and drove off.

That was the last time Orlando Brown Jr. saw his father alive.

The following day, Orlando Jr. received an odd text message. Orlando Sr. said he was sick. He said Orlando Jr. needed to see him. He never talked like that. "My dad, he's a tough-ass guy," Orlando Jr. says now. The younger Brown told his uncle Leroy—who essentially took care of Orlando Jr.'s vision-impaired grandfather—that he had to go home. Uncle Leroy said he couldn't drive Orlando Jr. to Baltimore. Your daddy will be O.K., he said.

On Wednesday night, Orlando Jr. called his father. He had been in a fight at practice. He told his dad he choked a guy to the point that his glasses fogged up. While Orlando Sr. sounded bad, he nevertheless told his son to continue to work, to stay on his grind, to never quit. The conversation ended around 8:30 p.m. Orlando Jr. called back only a couple hours later. His father didn't answer. Orlando Jr. made more than a dozen calls the next day, and more than a dozen times, no one picked up. After football practice, uncle Leroy met Orlando Jr. and drove him to his father's house.

It was 9:30 p.m. Thursday when Orlando Jr. knocked on his father's door, because he didn't have a key. No response. He and uncle Leroy walked to the back and saw the glow of the television through a window. He never leaves the television on, Orlando Jr. thought. A DeMatha game jersey and a book Orlando Jr. needed for school were inside. It was clear those items would stay there. Orlando Jr. told uncle Leroy they should just go back to D.C. I don't know what's wrong with him, Orlando Jr. said of his dad.

On Friday, he called again. Orlando Sr.'s friend and lawyer, Harriet Sheridan, picked up. She was crying.

Where's my dad? Orlando Jr. asked.

He's sick, Sheridan told him. Your mom is going to pick you up at school.

"I'm like, what the f---?" Orlando Jr. says now. "What do you mean my dad is sick? When you're 15 years old, you've seen your dad have the flu. What could he have?"

His final class that Friday was history, and DeMatha's principal interrupted the lesson to bring both Orlando Jr. and his younger brother, Justin, to the main office. The hallways had been cleared, except for teachers lining the sides. Orlando Jr. remembers thinking it was like everyone was praying.

In the office, Orlando Jr. pulled out his phone. He checked his Twitter feed and discovered the strangest mention. Something about Rest in Peace, Zeus, you were a great guy. He was confused. Man, I'm still alive, Orlando Jr. responded. Moments later, the sender apologized for breaking the news.

"That's how I found out about my dad's passing," Orlando Brown Jr. says. "Some random-ass guy."

He asked the principal: Did my dad die?

Justin started to cry. Shortly thereafter, Orlando Jr.'s mother arrived with his youngest brother, Braxton; they were crying, too.

No more boat rides on Chesapeake Bay to fish for rockfish or croaker. No more busing tables while his dad flipped burgers at Fatburger. No more Sundays on the couch watching NFL games as his dad dissected the pros' footwork. But of all his thoughts, Orlando Jr. kept coming back to one: That fast?

The state medical examiner determined Orlando Sr. died of diabetic ketoacidosis, a common but serious diabetic complication that occurs when the body can't produce enough insulin and acids called ketones build up in the bloodstream. The problem was Orlando Sr. didn't know he had diabetes. (Juices and oatmeal cream pies, the sort of stuff a diabetic in crisis shouldn't consume, lay around the house the day he died.) His father should have known better, Orlando Jr. reckons; he says two of his grandparents had it and adds that Justin was diagnosed with diabetes in grade school. Orlando Jr. remembers his dad working out while he was sick and talking about dropping 20 pounds. I'm looking good, his father said, oblivious to whatever condition he was perhaps exacerbating.

Orlando Jr. didn't enter the home that Friday until the authorities tended to it, which was just as well. The shower upstairs had been left running, steam filling the room. His father once said—long before people should think of such things—that if he were ever to leave this earth he'd do so in a praying position. Orlando Jr. says they found his dad on the side of the bed, a pillow under his knees and a hand on his heart, with his other hand open.

When he at last made it upstairs, Orlando Jr. saw a Ravens equipment bag on his father's bed. Inside was a pair of gloves, some cleats and a white bandana. In football, his father always told him, you have to have swagger. Something that differentiates you. Something about your appearance that makes you stand out.

The following January, four months after the funeral at which Orlando Jr. struggled to speak while surrounded by his siblings, he and his brothers moved to the Atlanta area with their mother, to be closer to her family. The ineluctable grief tagged along. It was with him on Aug. 25, 2012, not a year after his father passed away, when Orlando Brown Jr. had a football game to play for Peachtree Ridge.

It was the first start of his junior year. Orlando Jr. decided to wear a white bandana under his helmet. He has worn one every game since.

*****

Scott Winters/Icon Sportswire

Orlando Brown, Jr. has a question.

"Is it…Kwona?" he asks.

Quinoa?

"Quinoa," Orlando Jr. says, smiling big. "That's some good s--t."

His transformation into a viable Big 12 tackle across two-plus years at Oklahoma has been remarkable in many ways, not limited to a newfound enthusiasm for healthy foods he has trouble pronouncing.

Brown arrived with scant technical expertise and what he estimates as ghastly 33% body fat. Physicality led Oklahoma to believe Brown could succeed anyway, just as it led Tennessee to believe the same thing when Brown was a three-star prospect committed to the Volunteers as National Signing Day approached in February 2014.

But worries over Brown's academic slide led Tennessee to back off its scholarship offer just days before the time came to fax over a Letter of Intent. So Brown's coaches at Peachtree Ridge High in Suwanee, Ga., circled back to previously interested programs. Oklahoma took a commitment, and a risk. Brown then raced to boost his grades and test scores in spring and summer, officially qualified on July 24 and arrived at college two days later.

He was a 380-pound project, both physically and academically, which ensured he would sit out his true freshman campaign. This also ensured Brown would participate in Oklahoma's version of Monday Night Football, a weekly 50-play scrimmage for redshirting players. Brown still has the video of his first Monday night snap on his phone: He drives a defender back eight to 10 yards and, at the end, shoves the victim's head to the turf. And this was Brown going easy. "We couldn't get through 10 plays, and he'd be in a fight with somebody, every week," Sooners head coach Bob Stoops says. "And finally I got to where I just would stop the scrimmage because we don't do anything after the fight. He'd just get so competitive and mad."

Daily conditioning and an overhauled diet—salads, fish, chicken, turkey burgers, egg whites and, yes, quinoa—helped Brown reduce tonnage while enhancing his general well-being. "The way I sweat, the way I move, energy, sleep is so much better," he says.

It is not the only reason he is more comfortable. Brown was one of 10 freshmen in Oklahoma history to start at tackle but too often looked his age, failing to sense a blitz or pick up a defensive line twist. "I'd be kind of blind out there," Brown says. He devoted his off-season to craft work, spending "a ton" more time on film, and he now says he can see hand signals from a safety to a cornerback and guess what's coming.

"Since spring, he's been making calls about the defense before they even line up," Sooners left guard Cody Ford says. "He knows the defense like he's on the defense."

FIAMMETTA: Where does Oklahoma sit in Power Rankings after Week 2?

One relevant measure of progress: The Sooners' lodestar tackle graded out above 80% during preseason camp, surpassing what Bedenbaugh considers the "winning" threshold for technique and assignments. "I can't make the same mistakes I made last year and be considered great," Brown says.

He's athletic enough that Oklahoma uses him as a pulling blocker or sends him to the edge on screens. It makes for a terrifying package, this nimble man-mountain of rage. "He has that mentality of he's not going to let anyone touch his guys," Sooners quarterback Baker Mayfield says. "He's very protective. You gotta love a lineman having kind of a nasty mindset when they get on the field, where they want to punish the other team. It sounds bad, but that's the ultimate goal—when you're working in the trenches you want to punish the other guys."

While self-control is useful—"Last year his mentality was just like, 'I'm going to break the person in front of me,'" sophomore right tackle Drew Samia says—everyone concedes that Brown's elemental advantage is still aggression. Stoops may have halted those Monday scrimmages when Brown started scrapping, but he wasn't exactly bothered. "Listen, when I saw him fighting about every down as a freshman, I kind of snickered and liked it," Stoops says. "You just have to harness it, and he has. But, yeah, I'll take 10 of him."

Some fury makes Orlando Brown Jr. who he is. It is easy to understand why.

*****

Leslie Plaza Johnson/Icon Sportswire

"For me, that whole week, me losing him, the funeral and all that, that's just more motivation for me come Saturdays when I touch the field," Brown says, when asked how he processes the days that changed his life, five years hence. "It's one of the reasons I play so angry. Just to let that out. It gives me the feeling that me being out here is bigger than me. It's for the number 78. It's for the University of Oklahoma. It's for everyone that's played left tackle here. That's the lesson I learned from that. Man, it's so much bigger than me."

He is a born talker—about the only time it doesn't come easy is when he recites Cherokee from a class he's taking this fall—and his words have slowly but inexorably accumulated weight around Oklahoma. The honest, unflinching monologue Brown delivered during that academic meeting is not downplayed within the program. "That's not an easy thing to admit, the spot he was in," Rideaux says. And in less structured formats, like dorm rooms or off-campus houses, Brown drives the conversation even more. At full speed. "He talks, and he just talks and talks," Ford says.

It is Brown who leaned over to Ford, a first-year starter, and established rules of engagement: Don't let anybody talk to you like they're your daddy, Brown said. If they talk, you talk back. At the end of practices, Oklahoma's offense finishes with a series of hurry-up plays against the defense. Brown usually breaks the huddle before the first snap with a deluge of invective aimed at the other side of the ball. "I can't exactly go into details about it," Mayfield says. "It's not printable. But it just shows he plays with an edge no matter who he's going up against."

BAUMGAERTNER: Oklahoma State should be awarded win due to refs' blunder

In a relatively short time, Orlando Brown Jr. has become a voice apart. "I surprise myself sometimes," he says. "Just from the way I feel like I walk, talk, dress. For a long time I was stuck in this whole bubble—I want to be like my dad, I want to be like my dad. I never really, truly became myself. In the past year or so, I learned to embrace that role of being my dad but becoming my own person, you know what I'm saying? Man, I've grown a lot. I've changed a lot."

On the day his son begged for permission to play football, Orlando Sr. asked for a promise: You can't be done with this game until you're 10 years in the NFL, he said. Orlando Jr. hasn't forgotten that, but first things first. There is the degree. And then there is the long line of tackles who have passed through Oklahoma: Lane Johnson, Phil Loadholt, Trent Williams, Stockard McDougle, to name a few.

Orlando Jr. says being in the conversation with those guys is cool. But it's not enough. What he really wants is for people to visit Norman in 30 years and say Orlando Brown Jr. was the best to play the position. He wants his name distinguished from all others. Says the son of Zeus: "I want to be legendary."