Why Nick Saban Turned to Tua Tagovailoa to Write a New Alabama Legend

He held his headset in his hands, and if he hadn’t needed it, he might have thrown it all the way from Atlanta to Tuscaloosa. Alabama coach Nick Saban had put the ball in the hands of a backup true freshman quarterback (by choice). That quarterback was protected by a true freshman left tackle (by necessity). Now, down three in overtime of the national title game, those two had produced a disaster.

Tackle Alex Leatherwood had replaced injured starter Jonah Williams in the third quarter. Leatherwood had played well until Alabama’s first offensive snap of overtime, when he let Georgia linebacker Davin Bellamy slip past. Bellamy chased Crimson Tide quarterback Tua Tagovailoa, who had replaced starter Jalen Hurts to start the second half, backward. Bellamy dove and missed, but teammate Jonathan Ledbetter joined the pursuit. Tagovailoa kept backpedaling. Tagovailoa scrambled the wrong way so long that Bellamy had time to get up, chase again and sack him for a 16-yard loss.

But the great thing about freshmen is they don’t know what they don’t know, and Tagovailoa didn’t seem to grasp that the sack was supposed to doom his team. As Tagovailoa caught the next snap, on second-and-26 from the 41, another Alabama true freshman rocketed off the line of scrimmage down the left sideline. DeVonta Smith had seen the Bulldogs playing Cover 2. He knew he had a chance. Leatherwood blocked Bellamy. This time Tagovailoa stepped up in the pocket and saw Smith spring open. He cocked and threw.

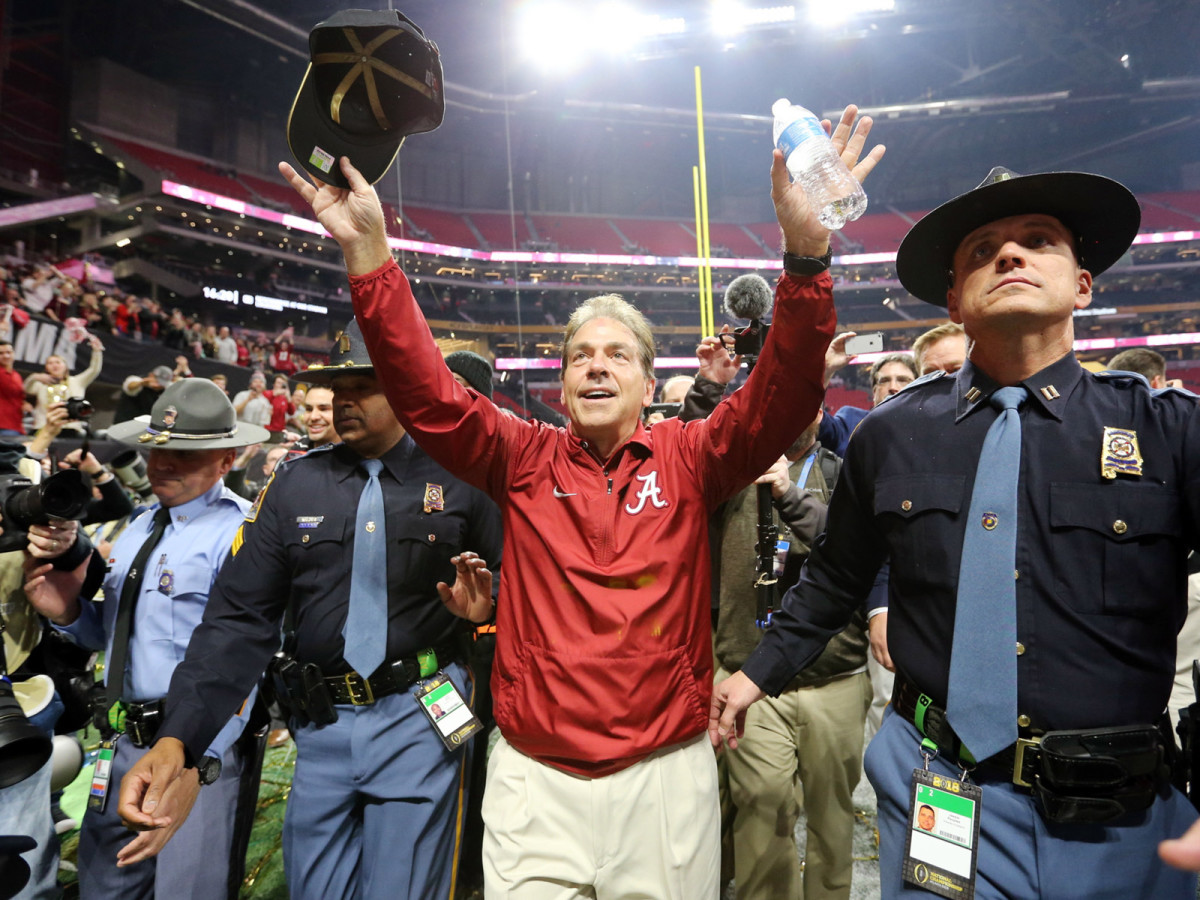

Confetti rained seconds after Smith crossed the goal line with the ball in his hands. “OH MY GOD,” Alabama center Bradley Bozeman screamed as tears streamed down his face. Bozeman then celebrated Alabama’s 26–23 win by proposing to girlfriend Nikki Hegstetter on the field. (She said yes, so both halves of the couple earned rings in Atlanta.) Moments later, Leatherwood sat on a bench and stared at the roof of Mercedes-Benz Stadium. “It feels like a dream,” he said as the first bars of “Sweet Home Alabama” played.

With his sixth national title—five at Alabama and one at LSU—Saban tied Alabama legend Paul “Bear” Bryant for the most ever won by one coach. Saban had to guide the Tide through injuries, through uncertainty created by a regular season-ending loss that almost derailed the Tide’s playoff run before it began, and, finally, out of a 13–0 halftime hole in the championship game that seemed too deep for an offense that gained all of 94 yards in the first half. The moment called for a drastic—or desperate—move, and Saban had one up his sleeve. He pulled Hurts, who had gone 25–2 as a starter, and took a leap of faith on a 18-year-old southpaw who a year ago was a high school senior in Hawaii and who had thrown just 53 passes in his college career, most of them in blowout win mop-up duty. “We needed a spark on offense,” Saban said after the game, which Tagovailoa finished 14–for–24 passing for 166 yards and three touchdowns. “Tua certainly gave us that.”

Bryant’s six titles were spread over 25 seasons at Alabama. After winning his first with LSU in 2003, Saban has won five with the Tide in just 11 seasons in Tuscaloosa. But to win this one and pull even with the ultimate Tide legend, Saban had to give his team his best coaching job.

• Alabama fans: Buy national champs gear here | Order SI's championship package

Bear Bryant watched Alabama’s practices from atop a tower. On the rare occasions he descended during practice, players braced themselves for a tongue-lashing. After Saban dons his straw hat before each practice, he climbs no steps. He participates as actively as his players. In Bryant’s era, players knew a tongue-lashing was coming when they heard the chain that blocked the entrance to the tower clang off the tower’s metal piping. In the Saban era, one of the coach’s famous “a-- chewings” can come at any moment.

Need to locate Saban at the start of an Alabama practice? Find the cornerbacks. Alabama defensive coordinator Jeremy Pruitt, who served as the Tide’s secondary coach from 2010 to ’12 (and will be head coach at Tennessee next season), once joked, “everybody in the country knows who Alabama’s DBs coach is, and that’s Nick Saban.”

The truth is that Saban, who was a defensive back at Kent State, doesn’t always act like the DBs coach during practice. Sometimes he acts like the graduate assistant who works for the DBs coach. Five days before the championship game in Atlanta, Saban ran cornerbacks through agility drills during a practice. Then he grabbed a football and threw passes for those corners to intercept. (At 66, the former high school quarterback can still spin it.) Other coaches have gravitated toward a pure CEO role as they’ve aged. Saban refuses to disappear into football’s version of an ivory tower. “I enjoy the game—the Xs and Os, the technical part, being involved at practice,” he says. “I haven’t separated myself.” Says Pruitt: “If they didn’t let him coach the corners anymore, I think he’d quit. So I think they’ll let him coach the corners as long as he wants.”

This helps on a micro level and on a macro level. With a field-level view Saban can see if a linebacker is struggling to read his keys and correct the problem immediately. Seeing the fine details on a daily basis also helps Saban see the big picture. That’s how he has adapted more quickly than some of his peers who’ve failed to keep up with schematic changes. “You’re there to see the flaws,” he says. “You’re a part of quality control. You’re not depending on somebody else to tell you ‘This isn’t working anymore.’”

In the early 2010s, when Alabama struggled against run-pass option (RPO) plays, which allow the quarterback to decide after the snap whether he’ll throw, hand off or keep the ball and run, Saban could see the problems on the practice field. He anticipated his team would have problems when it faced Johnny Manziel and Texas A&M in 2012 and when it faced the breathless Oklahoma offense in the Sugar Bowl after the 2013 season. They did, as both opposing teams outplayed the Tide defense in a pair of losses for Alabama. But because Saban spotted the problems early, help was on the way. The Tide had begun recruiting lighter defenders to match up with higher tempo offenses. The 2009 national title team started 365-pound Terrence Cody at nose tackle. The 2012 title team started 320-pound Jesse Williams. The 2017 team started 308-pound Da’Ron Payne, who is so nimble that he intercepted a Kelly Bryant pass and caught a touchdown pass as an H-back in the Sugar Bowl against Clemson. The linebackers and the safeties also got smaller. Meanwhile, Saban ordered his assistant coordinators to add RPOs into Alabama’s offense and to recruit a mobile quarterback who could run them effectively. Enter Hurts, a high school powerlifting standout from Texas who in 2016 became the first true freshman to start at quarterback at Alabama in 32 years. “The game is constantly changing,” Saban says. “So you have to change with it.”

But how much longer will Saban be willing to adapt? It’s human nature to become resistant to change, but this tendency doesn’t seem to apply to Saban. Rules have been passed to thwart advantages Saban creates, and he has adjusted. When the NCAA banned head coaches in 2008 from visiting high schools to watch practice during the spring evaluation period, Saban became one of the first coaches to use video conferencing to talk to recruits. After coaches at other schools complained about Saban’s roster management techniques, the SEC changed the rules that govern how many recruits a school can sign each year. Saban wouldn’t be able to erase his recruiting mistakes so easily by convincing them to transfer and simply signing more players to fill their spots. When the league passed the new rules in 2011, Alabama had just signed the nation’s No. 1 recruiting class according to the 247Sports.com composite rankings. Alabama’s next six recruiting classes also ranked No. 1 in the nation, and the Tide won four SEC titles and three national titles during that span.

How has Saban kept complacency at bay? “I’m never satisfied,” he says. “My greatest fear professionally is that we might lose the next game.” That pressure comes from within. “It’s not because of the fans. It’s not because of the expectations,” he says. “I want to do the best job I can to help our players have the best opportunity to do that. I hate the feeling you have when you lose, but I also hate the feeling that you have when you didn’t do a good job for your players.” That fear strikes every day. Even though no coach in history has won more titles than Saban, even though a contract extension signing bonus pushed his salary to $11.125 million for 2017, he still coaches like a man who thinks he could be fired at any moment. “When I get to where I don’t feel that way anymore,” he says, “I would rather call it quits than to be satisfied watching it go down.”

That would be a dark day in Tuscaloosa, but given Saban’s age and accomplishments, it’s now a legitimate question to ask when that will happen. Will he coach his way past Bryant in the record books? He only needs one more title. But there’s reason to believe that winning championships is only going to get more difficult for a coach who has made winning titles look so easy. If the next one is as difficult to win as this one was, it may take a while. Or it may not come at all.

All those top-ranked recruiting classes should render a team immune to rotten injury luck, but Alabama’s linebacker depth chart following a season-opening 24–7 win against Florida State suggested otherwise. Outside linebackers Christian Miller (biceps) and Terrell Lewis (elbow), injured in the season opener, were lost until late November. Outside linebacker Anfernee Jennings (ankle) and inside linebacker Rashaan Evans (groin) missed games in September. The list only grew longer as the season wore on. Freshman Dylan Moses missed the Colorado State game with a concussion. Outside linebacker Jamey Mosley missed the Ole Miss game because of an illness. Just when it seemed the Tide were starting to get healthy, middle linebacker Shaun Dion Hamilton broke his kneecap against LSU and was lost for the season. In that same game, linebacker Mack Wilson sustained a foot injury that would require surgery. Despite a pessimistic initial prognosis, Wilson didn’t miss the rest of the season and returned an interception for a touchdown in the Sugar Bowl. That was fortunate, because Moses—who excelled while replacing Wilson in November—was lost for the College Football Playoff after suffering a foot injury at practice in December. The pain didn’t end there. Jennings went down with a season-ending knee injury in the fourth quarter of the Sugar Bowl.

“It was kind of like, this is ridiculous, man,” says Evans, who wound up splitting time calling defensive alignments with Wilson. “I’ve never had so many people get hurt in one season.”

Those injuries made Alabama look different than it had looked since the Tide began winning national titles under Saban in the 2009 season. At times down the stretch, the Tide looked downright . . . normal. They squeaked out a 31–24 win at Mississippi State. After a 56–0 win against Mercer, the top-ranked Tide headed to Auburn—where the Tigers had creamed No. 1 Georgia 40–17 two weeks earlier. Auburn manhandled Alabama in a 26–14 Iron Bowl win, and suddenly the Tide’s chances of reaching a fourth consecutive College Football Playoff seemed slim. For the first time, neither Saban nor his team had any control over the Tide’s playoff chances.

The Tide also had a brewing issue at quarterback. Though the Auburn loss was only the second for Hurts as a starter, he averaged only 5.1 yards per pass attempt. Hurts also carried 18 times for 82 yards. Alabama’s deep stable of backs combined for only 19 carries that day even though the group averaged 6.8 yards a carry. After the loss, the drumbeat grew louder for Tagovailoa, who looked like the better passer in limited action. Could the offense run more smoothly with Tagovailoa throwing downfield and the backs handling the bulk of the running?

The day after they returned to Tuscaloosa, Alabama players lifted in the weight room and sprinted on the field. They couldn’t control their fate, but they’d be ready in case the playoff selection committee decided to place them in the bracket. “Whether we made the playoff or not, it didn’t do any harm to be working hard,” left tackle Williams says. “We could have played in the Buttermilk Bowl. It still would have been beneficial.”

Alabama’s actual bowl destination would be much sweeter.

Shortly after Ohio State made its case by beating Wisconsin for the Big Ten title on the night of Dec. 2, Saban, reduced to an unfamiliar role, called in to ESPN. He would rather have coached a football game that day, but the loss to Auburn had reduced him to politicking for a playoff spot. ACC champ Clemson, SEC champ Georgia and Big 12 champ Oklahoma were most likely in the field. The selection committee’s choice at No. 4 came down to Alabama, which was 11–1 and hadn’t even won its own division, and Ohio State, which was 11–2 but had been beaten 31–16 at home by Oklahoma in September and pounded 55–24 at Iowa in November. “If we lost to a team in our conference that was not ranked by 30 points, we wouldn’t be having this conversation,” Saban told SportsCenter host Scott Van Pelt. “You wouldn’t even be talking to me.”

Later that morning, the members of the selection committee agreed with Saban. They chose Alabama as the No. 4 team and sent the Tide to face No. 1 Clemson in the Sugar Bowl in a rematch of the teams that had split the previous two national championship games. The first two meetings were classics. The Alabama defense sucked the life out of the third, with a smothering performance over the Tigers in a 24–6 win. The Tide, who had averaged 2.6 sacks a game, sacked Clemson QB Bryant five times. Alabama limited an offense that had averaged six yards a play during the regular season to a miserable 2.7. Alabama had made the top seed in the playoff look average, and the Tide would get a chance to win a second national title in three seasons and a fifth in nine seasons.

But to do it, Saban would have to beat the man who had been one of his top lieutenants and the program that had emerged as the greatest potential threat to Alabama’s dominance.

Georgia head coach Kirby Smart had helped Saban win four national titles as Alabama’s defensive coordinator. He knew the Tide’s roster intimately, and he knew all of Saban’s tendencies. And Smart put together a brilliant game plan to stop the Alabama offense in first half of the national championship game. With his own true freshman quarterback (Jake Fromm) humming, Smart just needed his Bulldogs to hunker down for another half to collect his first national title. But Tagovailoa’s entrance changed everything.

“When coach Saban sees something...” receiver Calvin Ridley said after the game. Saban sensed that minor halftime adjustments wouldn’t help the Tide offense. Hurts had completed only three of eight passes for 21 yards. Something had to be done. Tagovailoa had expected to play in the Sugar Bowl but didn’t leave the sideline. “We had this in our mind that, if we were struggling offensively, that we would give Tua an opportunity,” Saban said. “Even in the last game.”

Tagovailoa was ready. So was fellow freshman Najee Harris, a jumbo tailback who had carried only 55 times entering the title game but led Alabama in rushing with 64 yards on six carries. On Tagovailoa’s second drive, he completed three consecutive passes to Henry Ruggs III (another freshman), including a six-yard touchdown pass. An 80-yard Fromm-to-Mecole Hardman touchdown pass to make it a 20–7 game didn’t faze Tagovailoa, who led two field goal drives and hit Ridley for a seven-yard score to force a 20–20 tie with 3:49 remaining. Alabama was set to claim the title with a 36-yard field goal as regulation expired, but Andy Pappanastos’s kick sailed wide left.

The Process took over. Play the next play, Tide players told one another. Even after Georgia’s Rodrigo Blankenship booted a 51-yard field goal in OT and Tagovailoa took that sack on the next play, the Tide wouldn’t quit. They had lost a national title to Clemson in the closing seconds last season. Saban told his team this offseason not to “waste a failure.” They would win a title on the final play this season. “I hope you take something from this game,” Saban told his team in the locker room afterward, “and the resiliency that you showed in this game helps you be more successful in life.”

Saban’s success is undeniable. The question now is where this title ranks. The only way to know is to ask those who know him best. “No. 1,” says Terry Saban, who met Nick at science camp as schoolchildren in West Virginia and married him 46 years ago. “Of course.”

Alabama strength coach Scott Cochran, Saban’s consigliere since he arrived in Tuscaloosa, agrees. “No doubt, for him to put 13 [Tagovailoa] and put 22 [Harris] in. Think of all that and all the distractions and all of the injuries, and he’s on that stage holding that trophy.”

Again.