Houston's Offense Is Running at Hyperspeed and Pacing the Group of Five

Welcome to the Film Room. This is a weekly analysis of one big play, series, scheme or idea from the previous weekend’s action in an attempt to decipher what it means going forward.

One of the nation’s most prolific offenses is run without an actual playbook, relies on only one sideline signaler and operates faster than any other unit in the country. Through eight weeks, Houston is 6–1 and piling up points (48.7 per game, good for second nationally), yards (555.3, third in the country) and first downs (26.1, sixth). The Cougars have scored at least 41 points in each game this season, are winners of four straight and get a shot this weekend to knock off one of the few other teams with a competitive case to be the Group of Five’s gold standard this year.

For so long, the hype around Houston has centered on disruptive defensive tackle Ed Oliver, who was the subject of his own school-sponsored preseason Heisman campaign. Well, move aside, Ed. Quarterback D’Eriq King and Houston’s offense are overshadowing Oliver (who is questionable for this weekend’s game with a right knee bruise), running the scheme that Cougars offensive coordinator Kendal Briles and his father Art used at Baylor to win consecutive Big 12 titles in 2013 and ’14 (the Bears shared the latter with TCU).

This isn’t the first time Art Briles’s scheme has prospered elsewhere. Former Briles assistants Dino Babers and Philip Montgomery brought it to Syracuse and Tulsa after taking the top jobs there, and even Houston’s Week 9 opponent South Florida runs some concepts. USF offensive coordinator Sterlin Gilbert served on staffs with Babers and Montgomery and spent 2005 as a graduate assistant under Briles.

But this version in Houston has attached to it a person named Briles, a blunt reminder of that Baylor staff’s meteoric success and scandal-charged collapse. Surely you know the story by now: In May of 2016, the Bears fired Briles after a university-commissioned investigation found he was slow to act when confronted with accusations that multiple players had sexually assaulted fellow students. Unable to find a spot elsewhere in college coaching, Art Briles was hired this August as head coach of Guelfi Firenze, an Italian professional team in Florence, Italy. While Art and his wife live overseas—they moved there this fall—Kendal runs his father’s scheme 180 miles from Art’s last American coaching stop.

No one’s talking about how a Briles-led offense is again crushing competition in Texas. “They’re kind of getting overlooked,” ESPN analyst Kirk Herbstreit says.

Ahead of a Saturday afternoon visit from an undefeated, 21st-ranked USF team that could swing both halves of the American Athletic Conference, there’s no better time for a closer look.

Rapid Results

Briles joined the Cougars in January after a one-year stint at Florida Atlantic with Lane Kiffin, scrapping an offensive scheme on arrival that Houston had used to win 29 games in three years. That scheme? It’s the one Tom Herman installed before taking the Texas job, the same spread system that Ohio State operates under Urban Meyer. The Cougars had lost their top running back and four of their top five receivers. The leading returning wideout, King, is now the starting quarterback.

Just like any new coordinator, Briles evaluated his personnel in the spring to settle on an offensive attack that matured over the summer and has proven to be a beast in the fall. “We knew we had a decent O-line and a good tight end,” Briles recalls. “Once we figured out who our best people were, we tried to fit our formations to how they can line up quickly and play fast.”

And then he installed his offense—sans playbook. You can’t see it on television, but the primary documentation of Houston’s offensive system rests in Briles’s back pocket during games. A single scrap of paper, wrinkled and buried in his slacks, is only consulted between drives to jog his brain on whatever he hasn’t memorized. “Most of the kids these days we’re working with, they’d rather go home and play Fortnite than they would go to the local library and pick up a book,” Briles says. “If you show them video and they learn visually like most of these kids do—they’re staring at an iPad, staring at a phone, staring at a TV, playing Playstation—they see movements and engagements.”

How Houston Goes Fast

One of the key elements of this offense is speed. Houston’s average time between snaps is just shy of 19 seconds. Briles has set up his entire scheme to operate as quickly as possible. Only he signals in plays (there’s no middle man), and there’s no wristband strapped to players’ arms (because there’s no playbook).

Against Tulsa earlier this season, the Cougars executed five snaps in the first 53 seconds of the game, their offensive coordinator pacing with his unit down the sideline while furiously signaling. In the GIF above, you can see the white tape on his fingers so his players can better identify the signs, similar to the way catchers in baseball often use tape or even fingernail polish to help their pitchers see the signals. Briles began doing this while at Baylor when one of his receivers couldn’t decipher his signs from all the way across the field during a night game.

For a man who’s got an entire playbook stored only in his head, Briles is forgetful. He forgot to tape his fingers in Houston’s game against Arizona earlier this season, signaling the first series without it. A trainer now leaves tape in Briles’s locker ahead of each game as a reminder.

In order to make such quick calls, Briles must anticipate the next play. “You can’t have a crystal ball, but you try to think what is going to happen on that play if this happens,” he says. “I’m always knowing that if the ball is handed [this direction], [the spot is] going to be right hash [for the next snap] and I know where my guys are lined up so I can make another fast call. That’s why you try not to look down at a play sheet and tell someone else to signal. I try to see it and have everything in my head and rip off another play.”

Art Briles incorporated the hurry-up portion of his offense around 2010, his third season at Baylor, to combat a personnel deficiency. Then the receivers coach for the Bears, Kendal specifically remembers the meeting in which his father told the staff, “I want to be the fastest team in the country so y’all figure that crap out.”

“We said, ‘Yessir,’ and started trying to figure out how we could eliminate verbiage and get lined up quickly,” he says. In 2014, Baylor led the nation in snaps at roughly the same time between snaps mark the 2018 Cougars average.

The base: RPO

Things have come full circle in H-Town, as the offense Art Briles used to win four Texas state championships at Stephenville High in the 1990s and ran from 2003 to ’07 as Cougars head coach has made a return with his son at OC and Major Applewhite as head coach. “The meat and potatoes are pretty comparable,” says Houston run game coordinator offensive line coach Randy Clements, “but the throw game has a little more dressing to it.”

The system is all based around the run-pass option. The changes Clements is talking about are to the “tags”, the pass routes attached to runs on RPOs. Defenses continue to find new ways to defend the newest fad in football, so offensive coaches must “evolve with it or you’re going to get left behind,” Clements says.

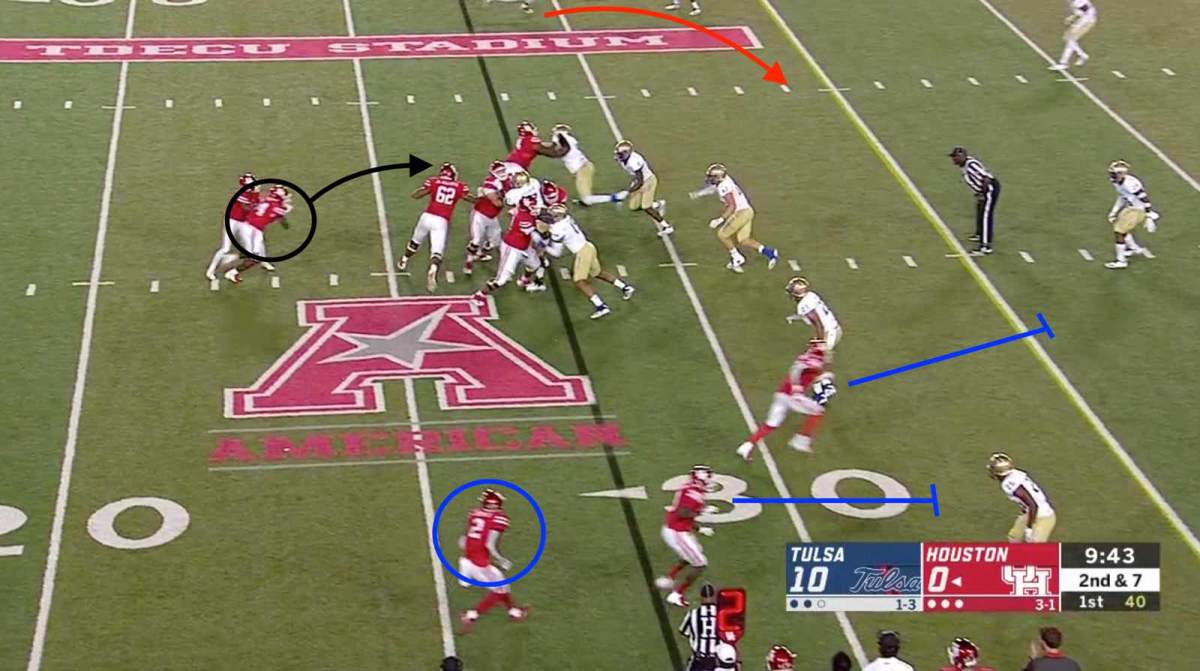

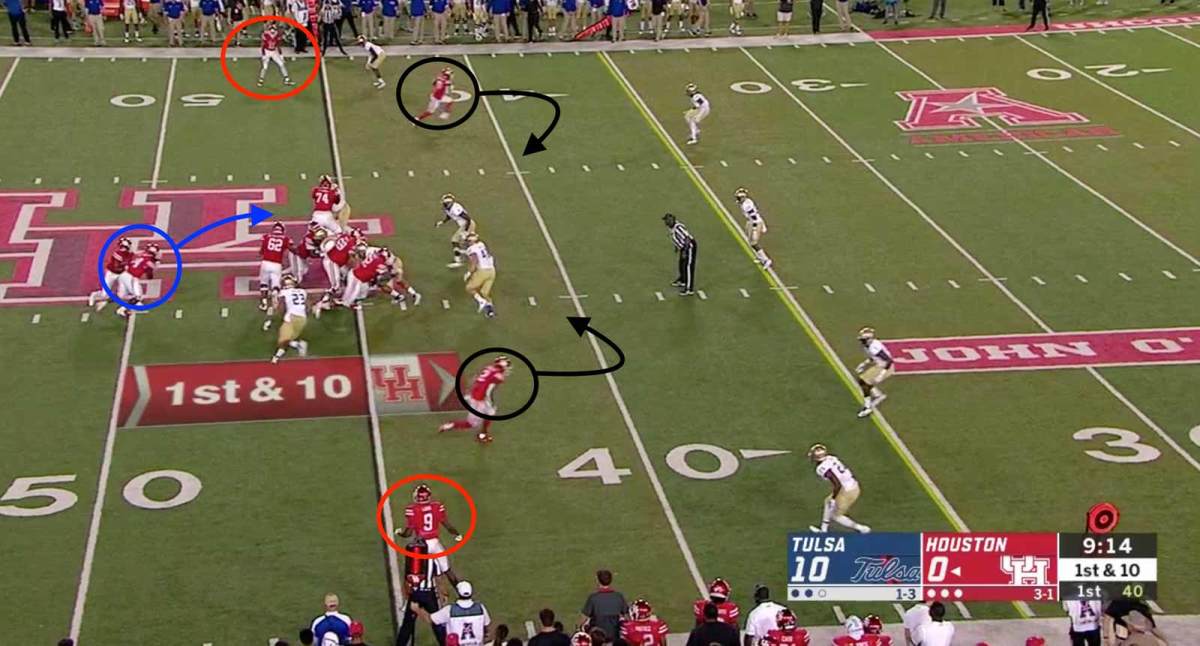

Briles says that many of Houston’s RPOs are decided before the snap, but there are a select few that King decides at the mesh point. You see two RPO plays above, based out of nearly identical formations, both with a pulling tackle as a lead blocker on an off-tackle run. In the first, King hands off to his running back (black circle), ditching his pass options: a bubble screen (blue circle) and a slant (red arrow). In the second frame, King chooses to pass to one of the receivers running a curl (black circles) over a handoff (blue) or two quick-out options (red).

D’Eriq King’s deep shots and the run game

King has so masterfully operated Briles’s offense that Oliver last month said Heisman Trophy voters should place King above him in their pecking order. King is averaging 283.4 yards a game, has a 23-to-3 touchdown-interception ratio and is completing 63.5% of his passes. King’s size—he’s listed at 5'11"—is a benefit in the RPO game, Briles says. His compact frame allows for a quick release. The other part is mental. “First of all, he’s smart,” Briles says. “He knows where his eyes should be in the RPO and makes good decisions with the football.”

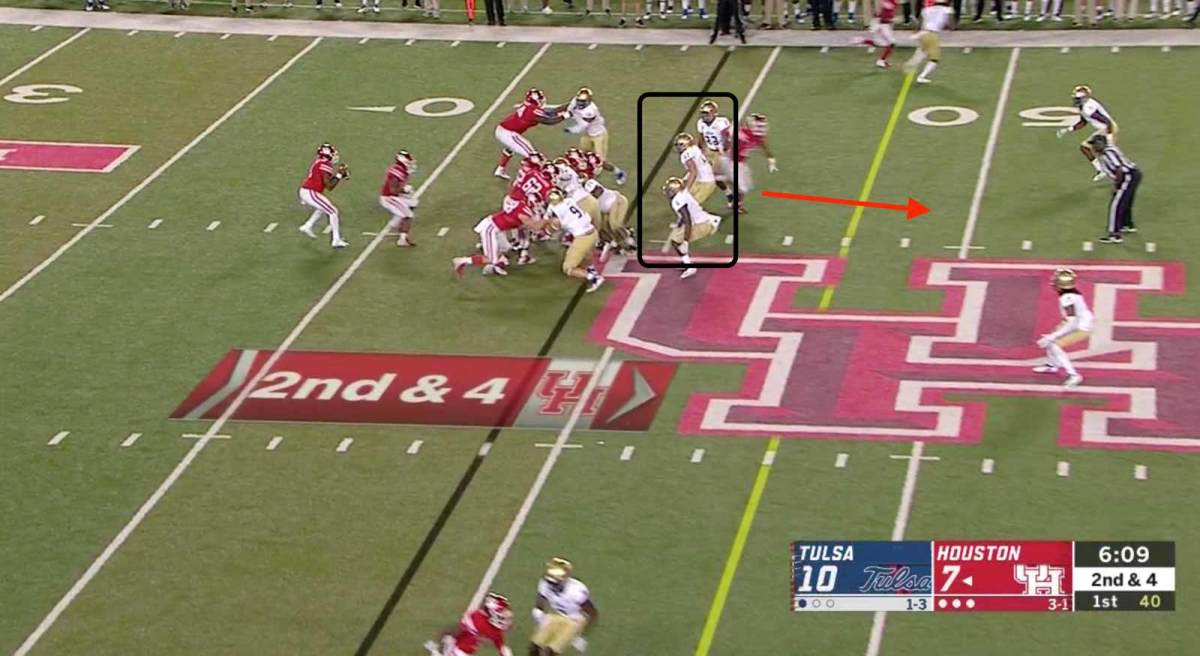

With King at the controls, Houston has completed 11 passes of 40 or more yards, fifth nationally. But it’s the run part of the RPO that makes this offense hum, Clements says. A good example of that is in the shot above. One second into the play, you see that King has fooled Tulsa’s linebackers—every single one of them—and froze the safeties with a play-action on a zone-read mesh. He hits an open H-back for a big gain down the middle of the field. The Cougars are averaging 234 yards rushing. They’ve averaged more than 200 on the ground just once in the previous decade.

All of the aforementioned elements—the speed, the RPOs, the rushing attack and long passes—have helped put the Cougars in position to claim that illustrious Group of Five spot in a New Year’s Six Bowl. But they’re in near must-win mode the rest of the way after a 63–49 shootout loss at Texas Tech earlier this season. Their tallest remaining hurdle outside of the AAC title game could very well be this weekend.