Recruiting’s Biggest Bait-and-Switch: The Uncommittable Scholarship Offer

Foster Moreau considered it “tacky” to commit immediately despite the circumstances: His dream college in his home state had just offered him a scholarship to play football. So he waited a week, then called LSU offensive coordinator Cam Cameron to accept the offer and announced it publicly, taking to Twitter with as much excitement as ever.

This was the only major college offer that had been extended to Moreau, a three-star tight end out of a New Orleans private school, and the fact that his commitment came on Christmas Eve was part of the celebration. “It was awesome,” Moreau recalls. “I was like, ‘Let’s tweet this! It’s going to be a great tweet!’”

While Moreau’s family celebrated his all-expenses-paid future in purple-and-gold, back in Baton Rouge his name was absent from the list of 2015 commitments scribbled on a whiteboard in LSU’s recruiting war room. Only weeks later did Moreau’s high school coach relay a message from the LSU staff: He was not guaranteed a spot after all. His heart sank. He deleted the tweet, and he planned to attend Tulane.

On the morning of National Signing Day, Tricia Moreau allowed her son to sleep in, finally shaking him awake at 10 a.m. He got into the shower like normal and then his phone rang. Suds still in his hair and water trickling off his body, he answered a call that turned his uncommittable offer into a committable one. “I pick up and Les Miles is on the line,” Moreau remembers. “He says, ‘Hey, Foster, how you doing?’”

On Wednesday, hundreds of high school prospects will be left holding dozens of meaningless scholarship offers, signing with a school only after other programs, despite offering them a scholarship, never accepted their commitment. Maybe those schools found a better player at that position, or maybe the spots in the class filled up. Some scholarship offers aren’t ever committable, just fancy invitations to a school’s summer camp, while others are only committable for a certain amount of time. In the most egregious cases, coaches rescind offers out to committed prospects, and in other instances, schools strongly suggest that certain commits seek other options. “The coaches mother---- the kids,” says one major college assistant coach who wished to remain anonymous. “It’s the biggest problem in our game right now. It’s bull----.”

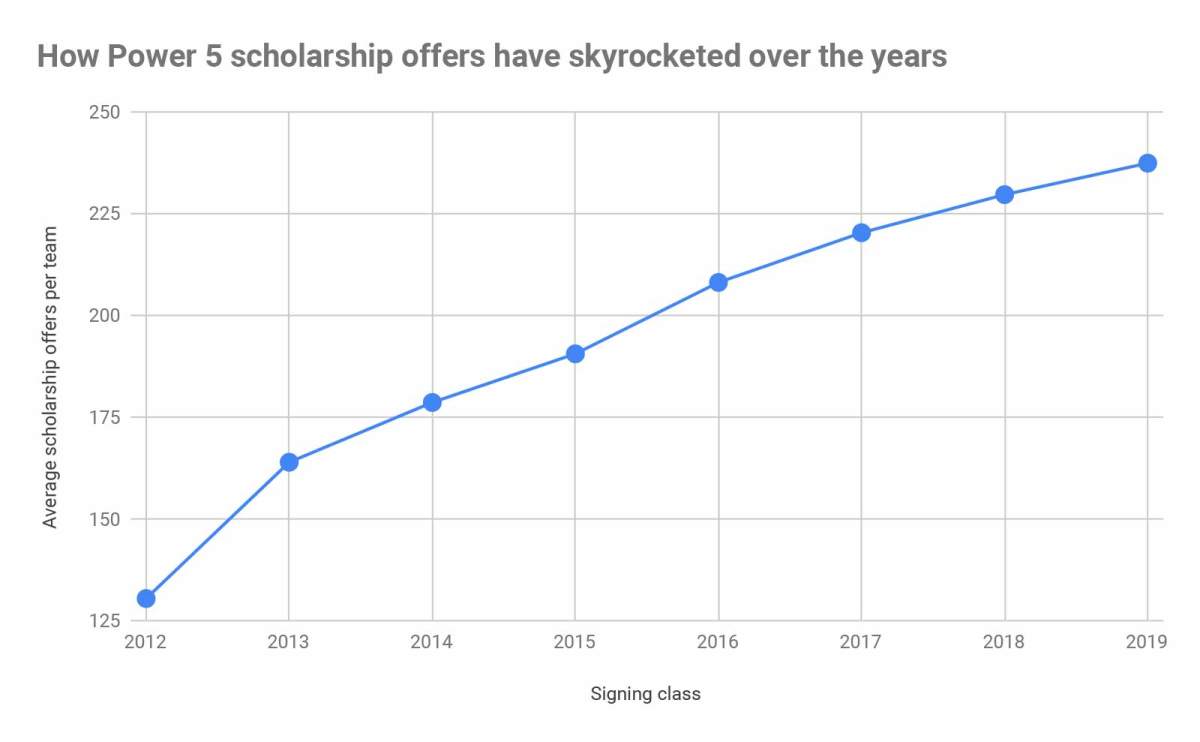

Never in the sport’s history have colleges dispersed so many scholarship offers, frivolously doling out hollow promises with the lure of free tuition. Using the 247Sports recruiting database, Sports Illustrated research shows an accelerating trend at the major college level that hit new, disturbing benchmarks this year. The study, covering the last eight recruiting cycles, produced galling figures within college football’s major conferences: more than 101,000 scholarship offers issued in order to fill about 12,000 available scholarships. For the 2019 cycle alone, the 65 programs in Power 5 conferences made more than 15,000 scholarship offers in order to secure what is expected be about 1,600 signees. That’s an average of about 237 offers per school per year, a 100-offer increase from the average in 2012. In what is believed to be a first for a college program, Louisville hit the 400-offer mark in 2017, and six programs have delivered at least 400 offers this year. One-fifth of Power 5 teams handed out at least 300 offers this cycle, for classes that do not often exceed 25 members. Just seven years ago, no school surpassed the 300-offer mark.

“It’s definitely something that’s gotten worse,” says 247Sports scouting director Barton Simmons. “This devalues the offer. Some programs fight to keep the value of their offer up. Other programs maybe don’t see the point of fighting it, and they play the game.”

Using the 247Sports recruiting database, SI compiled the total scholarship offers distributed by each of the 65 Power 5 programs since the 2012 recruiting cycle. Hover over the bar graph to find where your team sits.

Tennessee and Syracuse each distributed more than 440 offers this cycle, which is believed by industry experts to be a record. The Volunteers lead all major college programs in offers over this eight-year stretch (328 per year), followed by Louisville (323), Kentucky (291), Ole Miss (290) and Illinois (283). Rounding out the top 10 are Mississippi State (278), Nebraska (270), Indiana (268), Syracuse (254) and West Virginia (251).

There’s a reason the sport’s bluebloods are missing from the top 10. The schools passing out the most and earliest offers are typically secondary programs in competitive conferences. “They’ve got to get in early to beat the big dogs,” Simmons says. “Others try to create the narrative, ‘We don’t offer as many kids, so ours mean more!’ But that’s really hard to do.” While powerhouses may get to be more selective, some schools don’t have a choice. The two Power 5 programs with the fewest offers distributed since 2012 are private, academically rigorous institutions: Stanford (76 offers per year) and Northwestern (93). “They can’t just throw offers around like candy,” Simmons says.

The disparity within this spectrum is large. Stanford’s cumulative eight-year offer total of 608 is less than half of those delivered by programs in the middle of the rankings, like Michigan State’s 1,542. The Spartans in turn sit more than 1,000 offers behind Tennessee’s nation-leading total (2,627). Offer distribution is not just linked to a team’s historical place within its conference hierarchy; it is often tied to the coach in charge. Coaching changes often spike or dip offer counts drastically depending on the new coach’s recruiting method. For example, Mississippi State distributed 254 offers this year in its first full cycle under Joe Moorhead. That's 99 fewer offers than were doled out in the 2018 class, which Mullen recruited and then passed on to Moorhead when he left for Florida. Coaching changes often send a school’s offer total skyrocketing as new staffs hurriedly distribute offers upon arrival. Nebraska had one of the largest year-to-year increases in offers, from 2018 recruiting class built over Mike Riley’s final season (277 offers) to Scott Frost’s first full year (422). Iowa State went from 218 offers in 2016 under Paul Rhoads to 355 under Matt Campbell, and Jim Harbaugh distributed 101 more offers in his first year at Michigan than predecessor Brady Hoke had the year before.

Coaching changes can be tough for those who thought they had committable offers. “It’s been ridiculous at times,” says Kevin Wright, head coach at IMG Academy, an athletics-geared boarding school in Bradenton, Fla., that has churned out more than 25 major college signees since 2014. “I had a coach last year, new head coach at a Power 5, call me and tell me a kid had an offer from the previous staff and asked me if I’d let him know it would be in his best interest not to accept the previous offer, because if he came, he wasn’t going to play there. The timing is so bad. It was after the college season and before the early signing date.”

Fixing this problem is complicated, and the responsibility doesn’t only rest with college coaches, industry insiders say. The uptick in offers coincides with an increase in decommitments by players. Last year, according to data from 247Sports, more than 600 players pulled their verbal pledge to a school, compared to 113 recorded decommitments in 2014. Even more significant than decommitments are those players who string along programs or delay their commitments. One major college staff member described a scholarship offer as a reservation at a restaurant. “The reservation doesn’t mean s--- until you show up at the restaurant,” he says. “Certain restaurants will hold your table. Others, 30 seconds after you’re not there, will give away your seat.”

In some cases, even early commitments are not accepted. In fact, one major college assistant admits that many of his offers through the years are for kids “to come to camp,” he says. “Then, you have to come on campus, work out and then the wording all of a sudden has changed and it’s not an offer anymore.”

Nick Saban’s Alabama program found itself at the center of this controversy in 2014, when a high school coach in Bossier City, La., barred Crimson Tide staff members from recruiting on his campus. David Feaster revealed during a Baton Rouge radio interview that he had banned Alabama coaches after they did not honor an offer to then Parkway High quarterback Brandon Harris, who eventually played at LSU and then North Carolina. The interview went viral, and Parkway High officials fired Feaster weeks later, citing his decision to shut out the Crimson Tide. Feaster, now offensive coordinator at Glenbrook School, has no regrets. “You have to stand up to it—‘Don’t treat my guys like this,’” Feaster says.

Over the last eight years, Alabama is the only perennial national title contender to land in the top 20 of offers, sitting 18th with an average of 220 per year. Saban’s offer strategy has evolved over the years, as the Crimson Tide have gone from extending 203 offers in 2015 to 287 this year. Saban has company. The SEC leads all conferences in offers per cycle (229 per year per team), significantly outpacing the conference whose teams average the fewest offers, the Big 12 (158). In fact, of the bottom eight Power 5 schools in offers, five are from the Big 12: Texas, Oklahoma State, Kansas State, TCU and Baylor.

The prevalence of uncommittable offers is directly linked to the increasing numbers of offers, which in turn is bolstered by the number prospects who are offered early, some before they enter high school. Harbaugh, for instance, made headlines a few weeks ago by offering a scholarship to seventh-grade quarterback Isaiah Marshall. Schools often race to deliver the first offer to a prospect, a defining moment for any teenage football player. “It’s so fast they don’t know the kids at all,” one assistant coach says. “The worst job in America right now would be a high school coach. You’re coaching a 6'6", 350-pound lineman who needs to lose weight, but he has 25 offers as a sophomore and he doesn’t listen to the high school coach. We’ve created something bad.”

AXSON: Five Key National Signing Day Storylines to Follow

Prospects crave offers, treating them as badges of honor and measuring sticks of their athletic success on par with tournament trophies or championship rings. Recruits, their parents or their handlers often pressure staff members into offering. Well, your rival just offered, so why haven’t you? At one point last year, former Georgia Tech head coach Paul Johnson, now retired, found himself in a meeting with his staff discussing 14- and 15-year-old prospects. He shook his head, looked around the room and, knowing he would soon step down, delivered a message: “I told our guys, ‘Hey, you guys offer all the ninth-graders you want. I don’t care. I won’t be here.’”

Some schools use offers as marketing ploys, offering players they have no chance to land or aren’t serious about just so their school is linked to the player on internet searches, recruiting web pages and social media. “It’s a huge issue, and it continues to snowball,” Wright says. “People are throwing out hundreds of offers out there, because why not? You’re getting publicity.” Uncommittable offers don’t only happen at the prep level, says George Rush, who retired in 2015 after 38 years and a record 326 wins on the junior college level at City College of San Francisco. He’s seen coaches offer his players after their first year of JUCO only to pull the offer following the player’s second season. “I had a guy once cancel every visit he had because he wanted to go there and they dropped them like a hot potato,” Rush says. He’s witnessed several prominent college head coaches pull offers from his players, but he declined to identify them. “It’s names you know,” he says. “Big names. One is an NFL coach now.”

For years, this trend has been seriously discussed in college football’s legislative circles, according to Todd Berry, executive director of the American Football Coaches Association. In 2017, the Division I Council tabled a proposal that would prohibit coaches from making verbal offers to prospects before Sept. 1 of their junior year. Berry says one of the goals of the two-year-old early signing period was to curb scholarship offers. “We have been kicking this can down the road for quite some time,” he says.

Officials have considered allowing prospects to immediately sign with a program once an offer is made. Another discussed proposal would insert a month-long window for a prospect to commit to an offer before it expires. Berry says officials have even discussed resurrecting the “conference letter,” something that’s been dead for decades. Conference letters bind a prospect to one school of their choice from each conference. Written offer letters still exist, but they are not binding. Schools can send offer documents to prospects starting Aug. 1 of their senior year of high school. “There’s no more value in a written offer than that of a verbal,” Simmons says.

NIESEN: Five Quarterback Battles to Watch After National Signing Day

For prospects, a written offer is at least a sign of a school’s sincerity. For example, Sheldrick Redwine, a two-year starter for Miami who’s now preparing for the NFL draft, received 33 verbal offers during high school career but got only 10 written offer documents. “Might not mean I have a spot,” he says, “but it feels good to see it in paper.”

Johnson has been outspoken on uncommittable offers. He believes an offer should be made in writing, with attached papers to bind both parties. “That would stop the kids from committing when they weren’t committed, and it would stop the coaches from offering non-committable scholarships,” he says. “That would alleviate all the s---show.”

The media is to blame, too, with its incessant coverage of teenagers’ potential college destinations. “The kids who now get all the attention are the ones who commit and decommit six times,” Johnson says. “The kids who commit and don’t change, they get one minute of fame and that’s it.” Recruiting reporters must wade through this mess, hanging their reputations on the comments of 16- and 17-year-olds while checking facts with college staff members. Prospects sometimes mistake flattery from a coach for an offer in a “miscommunication,” as Simmons says. Other players knowingly lie about an offer. They announce it publicly, often times on social media, only to have a recruiting reporter discover the truth from staff members. “I’ve had young people say that I’d offered them and I’d never had one conversation with them,” says Berry, who coached for 33 years before joining the AFCA in 2016. “Social media has created some challenges.”

In Moreau’s case, most recruiting reporters assigned to LSU did not cover his public commitment. They knew more about the circumstances than the player himself, and so did his mother. Surfing recruiting sites during the process, Moreau’s mom noticed that her son wasn’t included on any commit lists. “She’s like, ‘I’m reading these message boards! They don’t have you on the commit list!’” Moreau says. “I’m like, ‘Mom, I got offered by Cam Cameron. I know what I’m talking about!’” Moreau’s situation ended happily. LSU missed on a handful of highly rated prospects who committed elsewhere on signing day, leaving a single spot in the class for a guy who eventually became a three-year starter and team captain. “It’s weird how it works,” Moreau says. “If I commit before you, I should get the spot before you, no matter if you have five other tight ends offered in that class.”

College coaches normally begin building a signing class with a certain number of needs at each position: two quarterbacks or four receivers, five defensive linemen or one running back. They usually offer more players than they have room for at a position. The problem is that staffs have taken to offering 10 to 20 times their needs at a certain position.

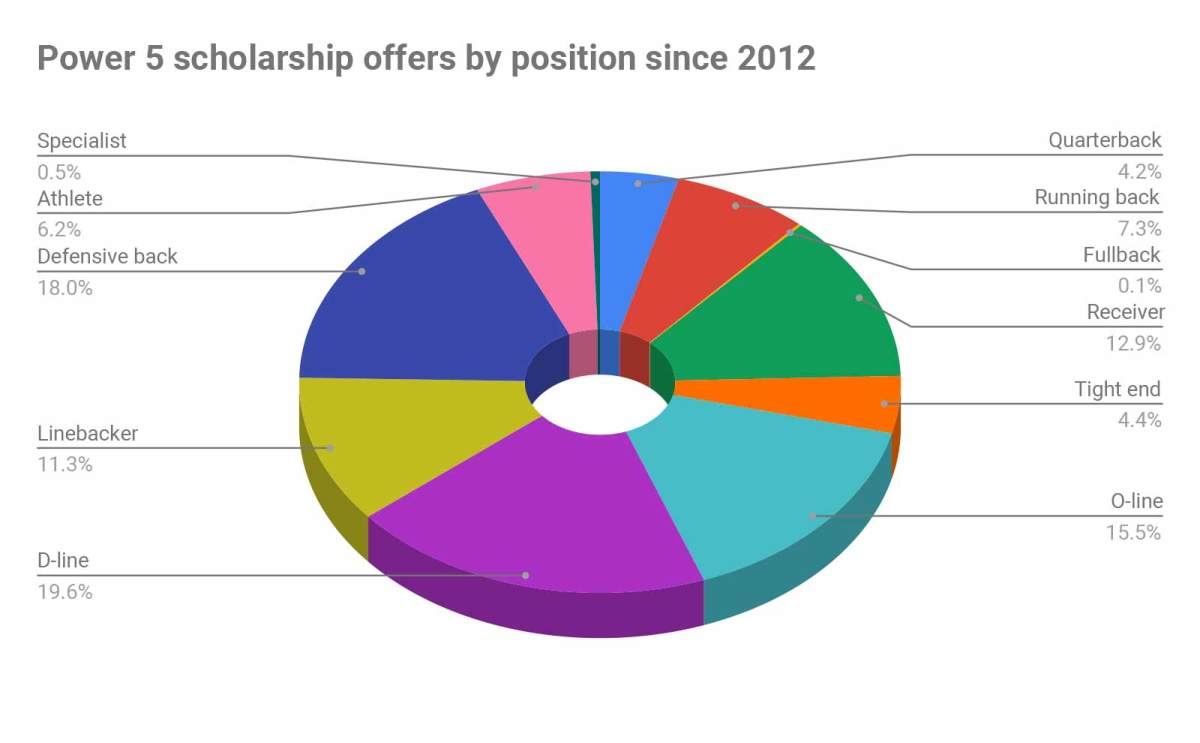

The data is startling. Since 2012, Power 5 teams have doled out about 40 offers each year to defensive linemen, with some schools going well north of that mark. In 2017, Ole Miss offered 91 defensive linemen a scholarship. The Rebels that year signed four players at that position. This cycle, Tennessee has offered scholarships to 112 defensive linemen, and Syracuse has offered 109 defensive backs. Those two positions groups, defensive line and secondary, have garnered nearly 40% of all Power 5 offers from 2012 to ’19, a sign of programs working to combat the evolution of the spread offense. In another sign of the times, just 150 fullbacks received Power 5 offers from ’12 to ’19. That’s roughly one fullback offer per team per four years.

At IMG, Wright educates his players about the scholarship offer process. He tells them to ask the offering coach three questions: 1) Is it committable now? 2) How many guys have you offered at my position? 3) Where am I in the ranking of them? “You always ask, ‘Can I commit right now?’” Wright says. “If the answer is no, it’s like a Like on social media—they just like you.” In one of the worst cases he can remember, an IMG senior started his season with five Power 5 offers, only to be left with one at season’s end. Coaches from that remaining school backed out of their offer just before the player planned to commit, days before the start of the early signing period. Their justification: They found a junior college quarterback at the last minute. “I’ve seen friends whose offer was pulled,” says Lonnie Johnson, a former Kentucky cornerback who’s projected as a high-round draft pick come April. “It devastated them.”

The devastation is expected to continue. As long as programs distribute hundreds of scholarship offers, dozens of them will remain uncommittable. Decommitments won’t slow either, experts say. This trend shows zero signs of changing course, and that means more potential stories like Benny Saia’s. While coach at Dutchtown (La.) High, located between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Saia saw two seniors, both committed to Arkansas, have their offers pulled a week before National Signing Day in 2014 after, he says, then Arkansas coach Bret Bielema found what he thought were better prospects. Cornerback Torrance Mosley and receiver Corey McBride were sent scrambling, eventually signing with TCU. Saia hasn’t received an apologetic call from Bielema.

“It’s a dirty business,” Saia says with a sigh. “That’s why I see these kids switch commitments. I don’t feel bad. It’s a two-way street.”