The Uncertain Future of the Juco Football Pipeline

The NCAA’s new transfer portal is the topic of the moment in college football, but to Charles Power, it’s just a variation on the website he has managed with his father for the last five years. You’ve probably never heard of their portal, but like the NCAA’s version, it supplies college football coaches with information on hundreds of available players in a neatly organized database. The difference is that Power’s portal exclusively contains junior college players. “It’s a very niche deal, but there was a big need for it,” says Power, who with his father Chuck has operated the subscription-based scouting database JUCOInsider.com since 2015.

Over a five-year period, the Powers have catalogued more than 5,700 junior college prospects on their site, nearly 700 of which eventually signed with a program from one of college football’s five major conferences. Junior college football (or juco) remains a lifeline for players who are athletically or academically unfit for FBS football out of high school while serving as a veritable farm system for some of Division I’s heavyweights. Oklahoma has signed 18 junior college players over the last five years, for instance, and Georgia added four alone in its 2019 class. Since 2015, several schools have spent almost an entire signing class’s worth of scholarships on junior college prospects. Kansas tops the list with 41, followed by West Virginia (28), Washington State and Colorado (26 each), Utah (23) and Oklahoma State and Iowa State (22 each). In all, about 800 junior college players join FBS programs each year, with roughly 150 of those signing with the 65 Power 5 teams.

As this pipeline continues to supply the top of the college game with talent, the pipeline itself is facing its darkest hour. All seven junior college programs in Arizona were recently shut down in controversial decisions that may eventually culminate in courtroom battles. The mass shutdown serves as a grim reminder of the significant hurdles these programs face to stay afloat and strikes fear in juco leaders who believe this to be a “trend” in one of the more financially stressed times in their history. Dwindling state support and a lack of alumni donations have further restricted already tight budgets and forced school leaders to consider shuttering their most expensive sport. The problems go beyond money: The revamped transfer process, the strict 25-man signing limit at the FBS level and the NCAA’s academic standards for transfers complicate juco football's place in the world of college football. The constant fight to reverse perception of jucos is tougher than ever, leaders say, and it's been made worse by the most significant exposure the sport has received in decades: the critically acclaimed Netflix series Last Chance U, a Hard Knocks–like peek behind the curtain at a juco program.

For all its problems, juco football continues to supply major colleges with immediate roster reinforcements, some of which go on to become NFL draft selections and productive pros. Eight former juco players participated in Super Bowl LIII, and at least four Heisman Trophy winners went to a community college at some point in their career. Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers famously played at Butte College before he starred at Cal. At least 27 former junior college players were picked in the last two drafts.

“Fewer junior colleges means there’s fewer prospects and fewer opportunities,” says Barton Simmons, a national recruiting analyst for 247Sports. “Jucos are the net that catches the rest of the world—the guy who didn’t start playing until his senior year, or the player no one recruited because of his academics or the quarterback who gains 50 pounds and moves to offensive tackle. Those are stories that are given life in the junior college ranks. Every junior college that disappears is losing an opportunity of a kid who could have otherwise played in the NFL.”

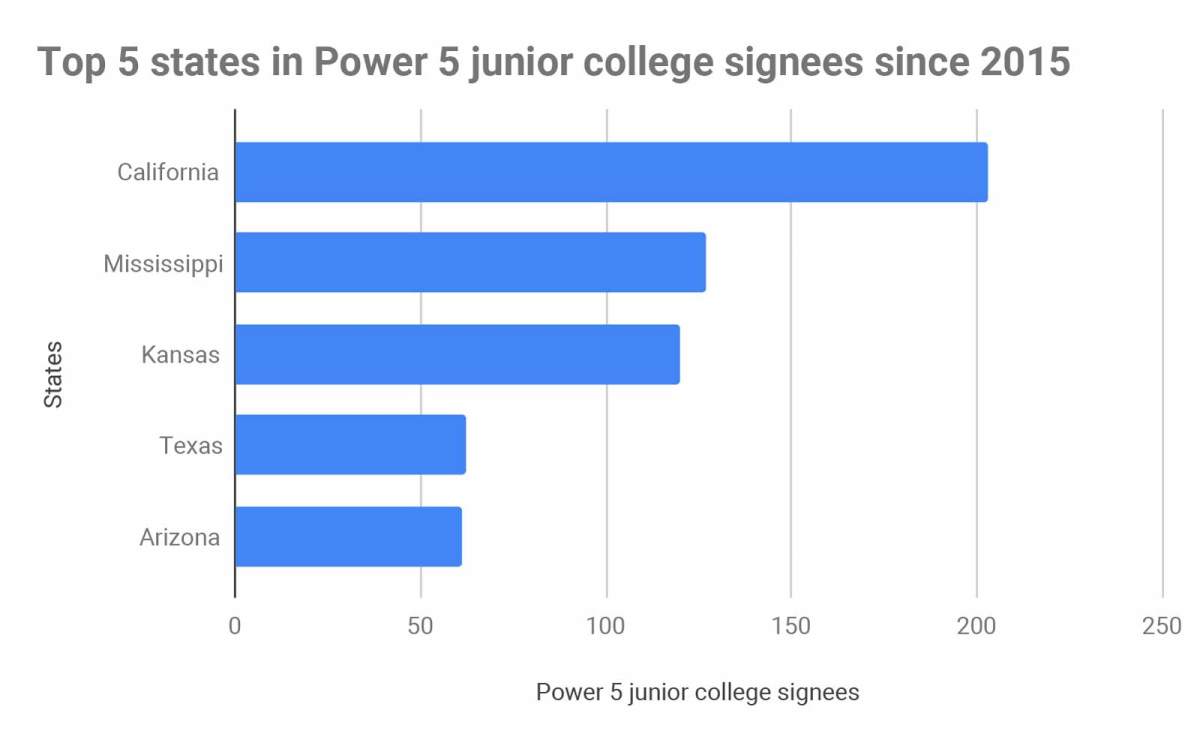

Most of the nation’s 1,462 junior colleges don’t offer football; the sport exists in pockets throughout the country. California leads all states with 68 juco teams, each of them belonging to the California Community College Athletic Association. The sixty-five members of the National Junior College Athletic Association are scattered across a handful of other states. Over the last five years, no state has produced more major college signees than California (203), followed by Mississippi (127) and Kansas (120). On the school level, Butler Community College in El Dorado, Kan., claims a nation-high 27 Power 5 signees, ahead of City College of San Francisco (25), now-defunct Arizona Western (25), Kansas’s Hutchinson Community College (24) and East Mississippi Community College (24).

“Football is not the foundation of your school, it’s simply the front porch, and it can be a good inviting scene to a great academic opportunity,” says Buddy Stephens, head coach at East Mississippi, one of the nation’s elite junior college powerhouses and the site of the first two seasons of Last Chance U.

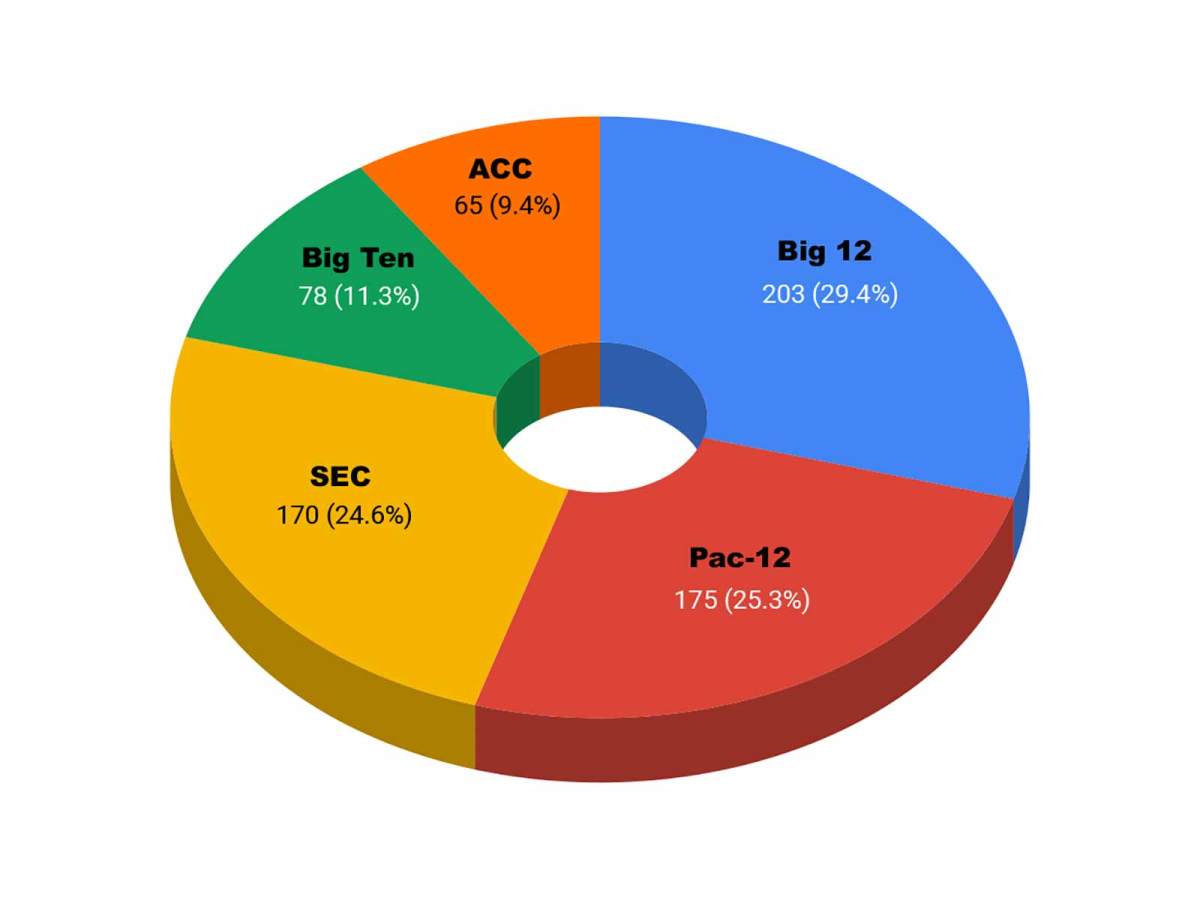

The geographic location of these programs determine the conferences they most often feed into. The Big 12, Pac-12 and SEC combine to sign nearly 80% of junior college players who join Power 5 teams. No conference is as reliant on jucos as the Big 12, whose 10 teams signed 203 juco players in the last five years compared to the 65 signed by the 14 teams in the ACC.

George Rush, who retired in 2015 after 38 years and 326 wins as head coach at City College of San Francisco, remembers when the CCCAA’s football-playing members reached triple digits, while states like Idaho, Washington and Oregon also offered junior college football. He sees a domino effect in Arizona’s shutdown: “This is the tip of the iceberg. It makes it easier for the next school to do it. ‘Oh, Arizona is doing it! We’ll do it!’”

Chris Parker, president and CEO of the NJCAA, admits that football is “a very expensive sport at our level.” The costs of equipment, travel, staff salaries and scholarships dwarf the teams’ only real source of revenue: ticket sales. Here, there are no multi-million rights deals, bowl payouts or consistent streams of booster donations. “We see at the Power 5 level, things continue to expand,” says Carlyle Carter, the CEO and president of the CCCAA. “Upgrades and there’s so much money involved, but at our level, that’s not the case.”

Figures range widely from state to state and school to school, but most within the junior college ranks believe every football program at this level loses money—some significantly. Take, for example, Itawamba Community College in Mississippi. The school spent $666,806 in 2016–17 on football, including more than $400,000 in salaries and scholarships. It made $17,436 in football ticket sales.

Scott Cathcart, the ranking junior college athletic director in the CCCAA, oversees athletics at Palomar College just north of San Diego. His annual athletics operations budget of $310,000 is so low that his 22 sports teams must fundraise about $200,000 each year. “We know we’re going to run out of money March 1, the fiscal year,” says Cathcart, who previously worked as an administrator at Temple. “It’s nothing like Division I. We’re not intended to make money. We’re intended to be educators.”

Juco football programs’ supporters would counter that even four-year college programs lose money—according to NCAA data, 46% of FBS teams finished in the red in 2016. There are other points to be made in their favor. Many states fund junior colleges based on their enrollment numbers, and football teams normally bring in north of 100 students, many of whom aren’t on any athletic aid. California’s football programs do not offer athletic scholarships, while about 60% of NJCAA football programs offer at least partial athletic scholarships, Parker says.

Without athletic scholarships, plenty of players are forced to obtain loans. At times, scholarship-equipped NJCAA schools lure away players from the CCCAA. That’s what happened with former Kentucky cornerback Lonnie Johnson, a projected second-round selection in this year’s draft who committed to Ohio State out of high school but didn’t qualify academically. He transferred to Kansas-based Garden City from California’s San Bernardino Valley College, where he had to walk an hour each day to campus and owned a single pair of cleats. “At Garden City, we had dorms on campus and scholarships,” he says. “It was way better than California.”

The CCCAA and NJCAA aren’t known historically for getting along. In 1951, the California State Federation of Junior Colleges approved a measure that barred all of its colleges from participating in NJCAA-sponsored events. To this day, schools from the two associations do not play. They hold separate playoffs and crown individual champions. But their current leaders realize that, in this struggling time, they are stronger together. Carter and Parker both confirmed to Sports Illustrated that they’ve discussed resurrecting the Junior Rose Bowl, an annual season-ending game pitting the association’s champions against one another in Pasadena. The last one was played in 1967. “We’re looking at the Army-Navy weekend,” Carter says. “When people say ‘juco’ it’s not meant to be flattering in a lot of peoples’ minds. I think there’s a misconception in what juco provides. The Junior Rose Bowl was an amazing event. We’ve been interested in having some type of a game.”

For the first time in years, NJCAA football membership slipped below its counterpart because of the closings in Arizona. Those in the junior college community describe the decisions in Arizona as “sad,” “a bad deal”—or, as former Mesa Community College football coach Ryan Felker puts it, “political and ugly.” The decision by Maricopa County Community College District officials to end football at Mesa, Phoenix, Scottsdale and Glendale triggered closures at Pima, Arizona Western and Eastern Arizona. Mesa has sent more than 80 players to Division I schools on football scholarships over the last six years, according to Felker, and Arizona Western was a juco powerhouse, producing the second-most Power 5 signees since 2015. Fearing the closure, Tom Minnick left his position as coach at Arizona Western after last season for Garden City, and about a dozen of his players followed him to Kansas. “Some of them found places to go. Some of them didn’t,” Minnick says. “Some went back because [Arizona Western] honored their scholarships for a semester.”

There is pushback in Arizona over the district’s decision. A legal fight is unfolding, and the first punch is a class action lawsuit Sports Illustrated obtained that attorneys filed on behalf of 11 Maricopa players. The suit, filed in December in the US District Court of Arizona, alleges that eliminating football violates federal law because it adversely affects black players, who make up more than 60% of the rosters. Attorneys are expected to present the suit to the Maricopa County district board on Friday, and many in the community are optimistic the decision to eliminate football will be overturned. Of the seven board members, three have been recently elected. In explaining the decisions to shutter football, Maricopa officials cited financial stress. The Arizona legislature and governor eliminated all state funding for Pima and Maricopa in 2015, part of a national trend in which junior colleges are caught in a losing battle for resources with secondary education and major colleges. “There’s more pressure on legislatures not to cut the funding for those other two entities,” says Jim Southward, a former juco coach in Mississippi who served as director of athletics for the Mississippi Community College Board for 16 years before retiring last month. “The community and junior colleges are just hanging in the middle. We don’t have the fan base and the support.”

These aren’t the only problems. “The big thing that’s killing us is this dang transfer portal,” Minnick says. Using the NCAA portal, many transferring players who traditionally would have dropped to the junior college level for a year are remaining in Division I now that schools no longer can control or limit their options. Meanwhile, the NCAA’s academic requirements for junior college players transferring to Division I schools (2.5 GPA) are more rigid than for those entering from high school (2.0), a disparity that Parker says needs to be investigated.

Image is another issue. Most of those contacted for this story heavily criticized Last Chance U, describing the series as a misrepresentation of junior college football. Some say they’ve even felt negative recruiting impacts. “You go into schools and they say, ‘Coach, that show…’” Minnick says. “You got to fight that wherever you go. Ninety-nine percent of it is negative.” Stephens, a central figure of the show’s first two seasons, says the exposure the series brought to Scooba, a town of 694 people in rural east Mississippi, is irreplaceable, but there was a negative. “The whole story was not being told,” he said. “There are times in the filming that the story is going to be told by the documentarian. Any time I started hollering or screaming or anything controversial, the cameras were running to film that.”

For Charles Power and his father Chuck, they hope the junior college pipeline continues to supply college football’s top tier with reinforcements. After all, it’s their business. JUCOInsider.com has subscriptions from about half of the 130 FBS schools, Power says. During football season, Charles spends Sunday through Tuesday analyzing every junior college box score from the previous week and then updating their portal with information. In the spring and summer he’ll make three to four road trips to visit multiple schools, speaking with coaching staffs and watching practice, upturning the stones of the junior college world to uncover some of the best tales in all of football. “The stories you get are crazy,” he says. “I made a profile today on a guy who graduated high school in 2012. I’ve heard of players playing a game with their ankle bracelet on. Some years, it’ll be August and we’ll have teams call and ask us, ‘Do y’all have an offensive tackle that can get here now?’”

From perception woes to financial troubles, junior college leaders remain optimistic that the industry will march on, but they are also realists. In Mississippi, Southward predicts significant changes will be made to offset the lack of funding, from reduced rosters and scholarships to limits on travel. Juco is just one level of college football, but it takes a collaborative effort from them all, says Parker. “We’re in the middle of that tier,” he says. “We can continue to open doors and have opportunities. We have to ask ourselves, ‘Without football, would the student go to college?’ In many of the cases, the answer is no.”