All Grown Up: Trevor Lawrence Leads a New Wave of QBs Ready-Made for Prime Time

This story appears in the Aug. 12, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

Julian Lewis is only 11 years old, but Nick Saban knows who he is. As Julian’s dad, T.C., tells it, at Alabama’s youth camp in June, the Crimson Tide coach took in the majestic precision of the boy’s quarterbacking, sidled up beside him and said, “I want you back. Every summer.”

Julian had been training for that moment since he was eight, that tender age when most boys are preoccupied with searching for boogers, not receivers downfield. That’s when he started working with private QB coach Ron Veal in hopes of one day attracting not just compliments, but also scholarship offers. While the notion of elite instructors like Veal molding lab-grown QBs destined for big-time programs is not new, here’s what is: Never before have so many of their pupils been so ready so fast.

Example 1A is another Veal client, one who came under his tutelage when he was 13. That would be Trevor Lawrence, the star Clemson quarterback who last season became the first true freshman since 1986 to lead his team to a national championship.

And so, on a sizzling day in suburban Atlanta, under the watchful eye of Veal, Julian is running a drill in which he backpedals just over five yards and then, off his back foot, slings the football across his body. T.C. calls it “the Trevor,” named after what became the Clemson QB’s signature move during his blazing rookie season.

All of Veal’s students must master the Trevor. It is a football exercise designed to improve a quarterback’s instincts against on-coming pressure. It is also a maneuver that most quarterbacks, especially the 11-year-old kind, avoid: throwing off your back foot and across your body. But Veal, 51, teaches advanced studies, drilling his charges on what to do in highly specific situations—like, for instance, when protection breaks down. The upshot: He and other coaches like him are giving young QBs tools that their predecessors simply did not have.

The impact is being felt at programs across the country. Put simply, the NCAA has never seen so much talent at quarterback all at once. Georgia’s Jake Fromm, Oregon’s Justin Herbert, and Alabama’s Tua Tagovailoa are all possible No. 1 overall draft picks in 2020 and on title contenders. Texas’s Sam Ehlinger, Michigan’s Shea Patterson and Nebraska’s Adrian Martinez are dark horse Heisman candidates, leading tradition-rich programs with playoff aspirations. Two high-profile transfers, Jalen Hurts (from Alabama to Oklahoma) and Kelly Bryant (Clemson to Missouri) are poised for monster seasons.

And then there’s the biggest star: the 19-year-old Lawrence.

To some, his rise was an anomaly, a once-in-a-generation event. But to others, the freshman’s success was a logical conclusion. With his blond hair, sweeping smile and square jaw, Lawrence is not only the face of the game, but also of a youth movement at QB like we’ve never before seen. “The evolution of our game continues to speed up,” says Missouri coach Barry Odom. “The mental approach it takes to play quarterback, they’re learning that earlier and earlier.”

Our lasting image of the 2018–19 season was of that tall, sinewy kid with the marvelous golden locks hoisting the national title trophy under a confetti shower at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara. Lawrence shredded the Crimson Tide defense, throwing for 347 yards and three touchdowns, with no interceptions. His breathtaking performance in Clemson’s 44–16 dismantling of No. 1 Alabama was a crescendo to a years-long evolution.

This youth movement at quarterback didn’t suddenly arrive on the scene with Lawrence. After all, in just the last three seasons, four first-year quarterbacks—all true freshmen like Lawrence—have played meaningful snaps in a national championship game. There was Jalen Hurts in 2016, and after that Fromm and Tagovailoa in ’17.

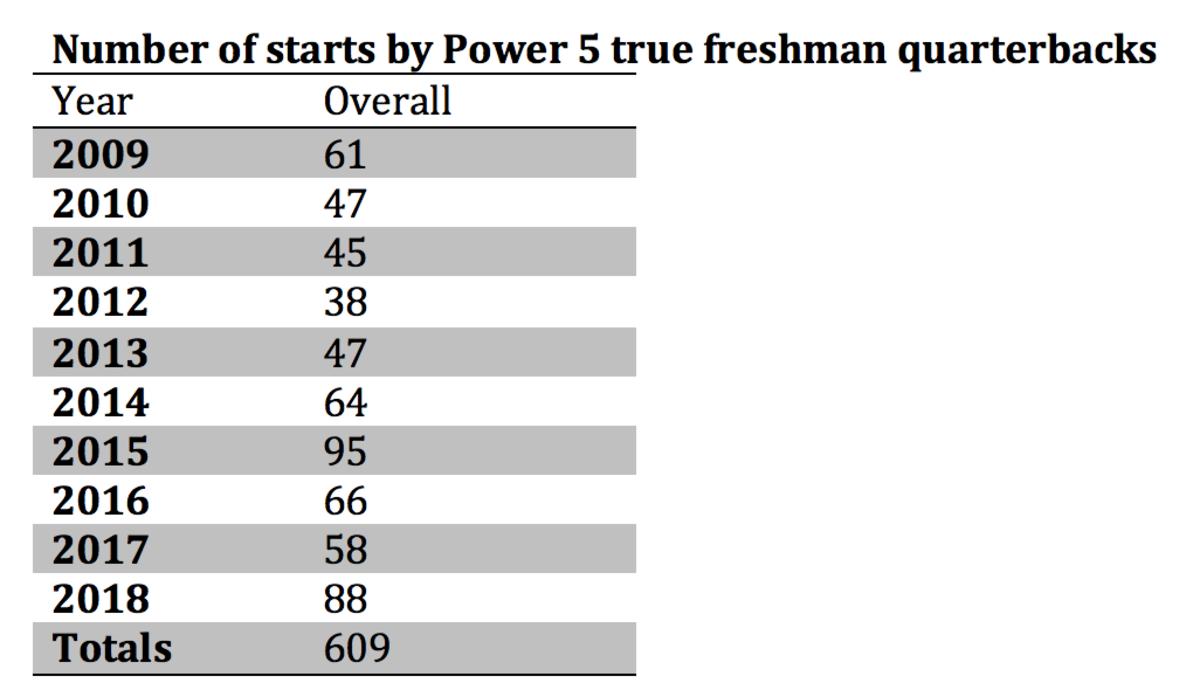

And last year, five rookie quarterbacks started a season opener at the Power 5 level—more than in any season in the previous decade. Overall, 12 true-freshman QBs started at least one game among the 65 major college programs, a fifth straight season in which that number hit double digits. Those quarterbacks combined to start 88 games, which is nearly twice the average of freshman starts from 2009 to ’13 (47.6).

College programs are setting records for their youth on the field. At Alabama in 2016, Hurts was the first true freshman quarterback to start a game in three decades. At Maryland, two true freshmen had started at QB in the previous 120 years; then five rookies started at least one game between 2012 and ’17. At Oregon, a true freshman hadn’t started at quarterback in 33 years before Justin Herbert did it in 2016, and the next year, Braxton Burmeister became the second in two years. In five instances at four Power 5 schools, a true-freshman-QB starter replaced another in the same season.

There’s another new batch of high-profile freshmen this season: Graham Mertz, out of Kansas, will challenge for the Wisconsin job, and Sam Howell is expected to contend at his home-state school, North Carolina. Arizona State’s quarterback competition features not one, not two, but three true-freshman QBs. And at TCU, highly touted rookie Max Duggan is positioned to be the first true freshman to start the opener at quarterback under coach Gary Patterson.

“Guys like Jake Fromm, Tua Tagovailoa and Trevor, this is going to be a trend you’re going to continue seeing,” says Danny Hernandez, an independent quarterback coach based in Los Angeles who counts among his clients the top-ranked dual-threat QB in the 2020 class, Bryce Young, and the No. 1–ranked pro-style ’20 QB, DJ Uiagalelei. “I work with kids 10- or 11-years-old, and they get it. These are going to be the faces of college football in a few years.”

Experts in college football attribute the youth movement to a wide variety of factors, none greater than the early specialization of young athletes—especially quarterbacks. Football parents are pumping money into developing their QB kids the way golf and tennis parents have for years, creating a year-round endeavor highlighted by the seven on-seven circuit and one-on-one training.

T.C. Lewis, the father of Julian, says he identified his son’s talents early and is following a script. “I don’t want to give away secrets,” he says, “but there is a blueprint. If a kid shows a certain skill set, there are steps parents can take.”

Here’s one of his secrets: Hire a personal coach. Trevor Lawrence’s father, Jeremy, began taking his son to college camps around age eight and sent him to Veal about five years later. “He was always really good from the waist up,” Jeremy says, “and Ron worked with him on using his legs and footwork.”

Among his peers, Veal is unique: He has no Twitter account, no Instagram, not even a website. Two private QB coaches interviewed for this article didn’t even know he trains Lawrence. Another longtime client is Justin Fields, the Georgia signee who transferred to Ohio State this offseason, but that’s not well-known either.

“He’s done a lot of good things for me,” Lawrence confirms, “but the best thing he’s done is he’s never tried to use me for anything and he’s never wanted anything from me.”

Unlike Veal, most private quarterback coaches aggressively market themselves and their clients through social media. George Whitfield, likely the most famous of them, was featured in an ESPN College GameDay segment in 2013 and was later hired by the network as an analyst. His rise has paralleled that of the field.

Some estimate the private QB coaching business has doubled in size in just the last five to eight years, but there is no way of knowing exactly. The industry has become something of a Wild West, says Whitfield, whose highprofile clients have included Cam Newton, Johnny Manziel and Andrew Luck. “You can walk out, make an Instagram account, get yourself a logo and say, ‘I’m coaching quarterbacks! Welcome to Bar-B-Q Academy!’ ” he says.

When Whitfield began training quarterbacks in 2006, the only widely trumpeted QB coach was Steve Clarkson, a Los Angeles–based trainer who began a quarterback academy in 1986. What once was a small, lightly populated “island” of QB trainers, Whitfield says, is now an oversaturated, crowded place where wrong methods are taught, parents are scammed and coaches are out for themselves.

“The island,” Whitfield says, discouragingly, “is going to implode one day.”

Pricing structures can vary, from as low as $50 an hour to more than $250, as can age limitations. Many coaches, like Veal, will not train kids under 10 years old. Some coaches, like Atlanta-based Tony Ballard, are content with taking on only 30 to 40 quarterbacks at one time, while guys like Hernandez, in Los Angeles, have well over 50. David Morris, a former Ole Miss quarterback, is the founder of a business that last year trained nearly 1,000 quarterbacks. QB Country employs 10 full-time instructors at 11 locations in eight states, with a home base in Mobile. In a sign of the youth movement, QB Country’s minimum applicant age recently moved from sixth grade to fourth grade.

Its list of clients range from elementary school kids to those in the NFL, with names that include Georgia’s Fromm and Daniel Jones, the Giants’ first-round pick this spring.

The coaches are aware they have critics. “There are a lot of people down on the independent training world,” acknowledges Morris. “I think it’s silly.”

The likability of those in the industry is “50-50,” Veal says. “Some people like us and some hate our guts.”

Some critics believe the biggest issue with private trainers is their relationship with their pupil’s high school or college coaches. It can get sticky. Broddrick Archie’s 15-year-old son Bryce, a Veal client, was taught by his high school coach the “exact opposite” on a technique, he says. Some trainers communicate regularly with high school or college coaches. Others do not.

Lawrence’s high school coach, Joey King, says the most important thing is to not overwork the player, something he never felt happened with Lawrence.

College coaches have for years pushed back against private trainers, but they’re warming to the industry. Some even send their own children to them. For the last four years, Chandler Morris, the son of Arkansas coach Chad Morris, has trained in Dallas with Kevin Murray, a longtime quarterback guru and the father of the 2018 Heisman Trophy winner. “Being a coach and a dad, what I have seen is, as a coach, when you get a quarterback, you can focus on footwork and fundamentals for only a certain amount of time,” Chad Morris says. “You’ve got to get into schemes and reading coverages. Although they may look at coverages, private coaches are more focused on the technique.”

Private coaches, of course, are not necessary to land big scholarship offers. Florida quarterback Feleipe Franks, at one point the top dual-threat QB in his class, never had one, instead learning through high school coaches and training videos on YouTube. Others swear by the private coaching industry. “I don’t know where Bryce would be,” Broddrick says, “without Ron Veal.”

Of course, Veal isn’t the only individual behind Lawrence’s success. Even he says he doesn’t warrant such distinction. “Whoever takes credit for the arm, it’s a flat out lie,” Veal says. “He’s a natural thrower.” There are other influences in Lawrence’s life, like King, his former high school coach in Cartersville, Ga., or Michael Bail, Cartersville High’s quarterbacks coach. And, of course, the Clemson coaching staff, like co-offensive coordinator Jeff Scott and Tony Elliott, and quarterbacks coach Brandon Streeter. In any case, the end product has been a uniquely advanced QB. “Just from watching him on TV, I thought that guy could have been the No. 1 pick last year,” says one NFL scout. “He’s the most exciting quarterback prospect since Andrew Luck.”

Veal, originally from near Jacksonville, and a University of Arizona quarterback from 1987 to ’90, only began training quarterbacks by happenstance in 2001, after spotting an unschooled father attempting to train his son at a local park. “I found a lot of kids needed help,” says Veal, a firefighter on the side. “It spread through word of mouth.” Nearly 20 years later, his spring and summer days are full. On a recent Thursday in July, he ended an early-morning shift at the firehouse, drove to north Atlanta for a one-on-one session, traveled west to the Mud Creek soccer complex for group work with Julian Lewis and 15-year-old Bryce Archie and then had two more afternoon trainings. Four sessions in a day is about average for this time of year. On Sundays, it can climb to six. Lawrence still trains with Veal, and so does Fields, but their college schedules limit sessions to May, the one month of the year that they’re home.

On a July afternoon, two hours northeast of Atlanta, Lawrence slides into a chair, looks across a conference table in the Clemson football facility and smiles. “Boy,” he says, “lots has changed in a year.”

Not even Veal expected Lawrence to overtake a veteran starting quarterback midseason, throw for 3,280 yards and 30 touchdowns and lead his team to a championship. “Not in my wildest dreams,” Veal says.

Lawrence is a celebrity now, not only in the tiny north Georgia country town in which he was raised, but also nationally. There are pros and cons: After leading Clemson to the title, someone posted Lawrence’s cell phone number online. For a week, he received about one call every five to 10 minutes. “Oh, gosh, it was bad,” he says. “I had to change my number. I was just hitting decline over and over again.”

But he also met his childhood hero—the reason he wears number 16—Peyton Manning, and while attending church services with his girlfriend in Atlanta, he felt a tap on his shoulder, and turned around to see Atlanta Hawks point guard Trae Young in the pew. “I’m a big fan,” he told Lawrence. Mouth agape in awe, Lawrence finally responded, “I’m a big fan of you!” Lawrence is hard to miss at 6' 6", so trips anywhere in Clemson come with their own autograph lines.

Such is life as a football prodigy. Scouts describe Lawrence as a prototypical NFL quarterback, with a passing touch to go along with a rocket arm.

Lawrence’s size is a bonus and it’s something his Alabama counterpart, Tagovailoa, does not have. The Clemson QB’s instincts are well beyond his years. All of this said, he must remain in college for two more seasons before becoming eligible for the draft. He shrugs.

“Not to say I couldn’t be ready to do something like that, but I think the next two or three years will be really good for me,” he says. “I think I have a lot more growing to do.”

Lawrence returned to the Atlanta area earlier this summer for a session with Veal. He wants to make his release faster and more efficient. They focused on his following through on the release longer than normal and keeping his back leg planted, something Veal did not teach Lawrence during his younger years. Veal only recently incorporated the technique into his program, acquiring it from Tom House, an NFL instructor known for training Tom Brady and Drew Brees. Those two greats keep their back leg planted the best, Veal says, and while Lawrence’s footwork is good, it could be better. “It’s like hitting a baseball. You don’t lift your back leg off the ground,” he says. “You keep it connected to the ground and drive.”

Lawrence entered camp with the second-best odds to win the Heisman Trophy, behind only Tagovailoa. But the competition will be stiff—both from the QBs that fans already know and maybe even from the new ones arriving for the first time on campus. Three of the top five ranked quarterbacks who signed as part of the 2019 class have private instructors. Arizona-based coach Mike Giovando, who has tutored the likes of Colin Kaepernick and Tyrod Taylor, trains Spencer Rattler, an Oklahoma signee who will back up Hurts. Wisconsin signee Graham Mertz has trained in Kansas City with Justin Hoover since sixth grade, and Ryan Hilinski, who inked with South Carolina, is with Hernandez’s Team Dime in L.A., where one of their mottos is, “Never too young to start.”

Sitting in the conference room at Clemson, Lawrence is eager to talk about all the ways he can improve. As he discusses everything that came together his freshman season, which included 15 victories, no losses and a 28-point title-game win over a team many thought was unbeatable, he says that it was a special year. “You might never see anything like that again,” he says.

There are a whole lot of young quarterbacks, parents and private coaches, though, who think you just might.