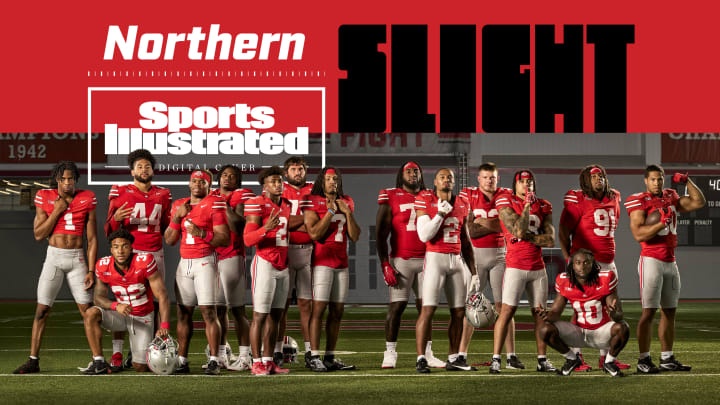

Ohio State’s Northern Slight Turned Into a $20 Million Comeback

Donovan Jackson wants to go into sports marketing when he’s finished playing football, and the star Ohio State offensive lineman has the personality for the job. Possessing wit, charm and an outgoing nature, the 320-pound Jackson is first-team All-Engaging. Until you ask him about Michigan. And the three-game losing streak to the Wolverines. And watching them win the 2023 national title.

Sitting on a bench beside the indoor field at the Woody Hayes Athletic Center on a July morning, Jackson’s voice drops and his tone flattens.

“Didn’t feel good,” Jackson says. “Obviously, the rivalry is the rivalry. I have my own personal opinions on that team. Knowing that we were close and knowing how far they went, it wasn’t a fun thing to watch.

“We’ve just gotta get it this year.”

Nothing motivates a college football program like the intolerable pain of losing control of a heated rivalry—and then watching that rival win it all. For Ohio State, Michigan’s controversy-steeped championship season has spurred a just gotta get it response the likes of which might be unprecedented in the sport. Players, coaches, administrators, fans and (welcome to the modern world) NIL collectives have gone all in to chase a title of their own.

The Wolverines defeated the Buckeyes 30–24 on Nov. 25. Ohio State finished the game with more yards and averaged more yards per play, but two scarlet-and-gray drives ended in interceptions—including one, at the Michigan 22-yard line, that sealed the game in the final minute. After two years of being thoroughly outplayed, the third straight loss to the Wolverines came down to a few crucial plays.

Over the next six weeks, Ohio State watched the loathed Team Up North finish 15–0 and win its first national title since 1997, powering through the Connor Stalions signal-stealing scandal that infuriated the rest of the Big Ten (and could still lead to sanctions against the Michigan program). Instead of wallowing in misery, though, the Buckeyes ambitiously drew up plans for a $20 million comeback for 2024.

Across a nine-day stretch in early January, eight players who would have been NFL draft picks chose to stay in school, most of them likely top-100 selections. Defensive tackle Tyleik Williams led off on Jan. 3; edge rusher Jack Sawyer and safety Lathan Ransom followed on Jan. 5; Jackson and cornerback Denzel Burke announced five days after that, followed by receiver Emeka Egbuka on Jan. 11; and running back TreVeyon Henderson and defensive end JT Tuimoloau finished off the loyalty drive on Jan. 12. When that flurry was over, four of Ohio State’s six 2023 first-team all-Big Ten selections were still in school.

Around the same time, star transfers started migrating to Columbus. Safety Caleb Downs, the No. 1 player in the portal, relocated from Alabama after Nick Saban’s retirement. Another first-team All-SEC selection, Ole Miss running back Quinshon Judkins, traded in the Grove for the Shoe. All-Big 12 second-team quarterback Will Howard from Kansas State joined the party as well.

The roster was suddenly so flush that the school’s last two national championship–winning coaches, Urban Meyer and Jim Tressel, both declared in June that this might be the most talented Buckeyes team in the school’s storied history. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” said Meyer, who is prone to hyperbole. But the understated Tressel backed him up: “I don’t know if I’ve ever seen that many great players in that building all at once.”

The talent stockpiling continued, extending beyond the locker room. Head coach Ryan Day revamped his staff, relinquishing play-calling duties and hiring Bill O’Brien from the Patriots as his offensive coordinator When O’Brien left three weeks later to take over the program at Boston College, Day simply found another savant, Chip Kelly, who stepped down from the top job at UCLA to call plays for the Buckeyes. When you can hire not one, but two former NFL and power-conference head coaches to be assistants, your program has some juice.

And some money. Because none of this would have been possible without a lot of that.

Ultimately, Ohio State and its collectives are attempting—within NCAA rules, such as they are—to buy a title. Day made headlines two years ago by estimating that $13 million was needed to maintain the Buckeyes’ roster, a figure that many deemed exorbitant at the time. Since then, the price has gone up. Sources familiar with the overall player payroll for Ohio State football this season say it’s about $20 million.

Brian Schottenstein, cofounder and board member of THE Foundation, one of two primary collectives supporting Ohio State athletics, says that donations to his nonprofit collective have tripled in the past year. You’ll never guess when the money started flowing in. “The big rise in donations came after the Team Up North game,” he says. “I think people realized now how important NIL is in the new era of college football.”

Michigan worked the same plan, albeit to a lesser extent last year, enticing several key players to choose another year of school, campus hero status, a nice income and the quest for a title over the uncertainty of NFL mid-round draft status. Unable to beat ’em, Ohio State has joined ’em—and then some.

Without revealing specific numbers, sources familiar with the team salary structure say Tuimoloau is the highest-paid returning Buckeyes player. Downs is the highest-paid newcomer. There is plenty to go around for the other standouts on the roster.

Schottenstein—whose family’s name is on the school’s basketball arena and whose uncle is a former trustee—dates his fandom back to watching Eddie George run all over Notre Dame in 1995. Mark Stetson, who helps run the other major collective, the 1870 Society, cites Tressel’s 2002 title run as his dream season. Both men are fans at heart and businessmen by trade who have somewhat unexpectedly pivoted to become vital fundraisers.

“Holy cow, it’s certainly a whirlwind,” says the 36-year-old Stetson, who is in healthcare tech. “The vast majority of us are volunteers, doing this for one reason only. We want to help Ohio State succeed. I’m rooting like crazy for all the other collectives, too. There is zero pride of ownership on my end.”

Says Schottenstein: “I have no experience being a general manager. But sometimes we joke that we feel like GMs.”

The unofficial GMs of Ohio State football acknowledge that while the players they make deals with are happy to have money, they’re also coming back for nonfinancial reasons. “As much as it feels like things have changed in college sports, and that a lot of the conversation centers around money, I think a lot of these decisions were old-school,” says Stetson. “These guys weren’t ready to leave Ohio State and, in particular, this group of teammates, and felt like the upcoming season could be special.”

At this point, it pretty much has to be special. The buildup has been immense. By mid-July, the school had sold nearly 57,000 nonstudent season tickets. The anticipation is growing. “Ohio State fans are relentless,” Stetson says. “And I mean that in all the positive permutations, and also in the ways that create something of a pressure cooker.”

It’s time for Ohio State to produce a commensurate return on the considerable investment made by everyone. This is a massive, statewide machine that has been engaged. Will it run smoothly? “All the pressure is on to actually perform,” Schottenstein says. “The bar is very high.”

Caleb Downs had already decided he was coming to Ohio State. But he couldn’t resist putting Day through a few seconds of prankish anguish before delivering the good news.

Day had just gotten off of a plane on a recruiting trip to Mobile, Ala., in January when he anxiously returned a request from Downs to FaceTime him. Downs, who grew up in tiny Hoschton, Ga., was coming off a 107-tackle freshman season at Alabama. He was now choosing between Georgia and Ohio State. Day figured this would be the deciding moment.

Day was confident. In high school, Downs had FaceTimed Day in tears to say he was turning down the Buckeyes and going to Alabama. With the help of secondary coach Tim Walton and THE Foundation, Day believed Ohio State had done enough to get Downs the second time around.

But Downs began the conversation with a sorrowful apology to Day—“I put that sad face on,” he says—then hung his head.

“Stop,” Day said. “Don’t do this again.”

“Just kidding, Coach,” Downs responded. “I’m coming.”

Downs has his own painful memories about Michigan: His Crimson Tide team lost to the Wolverines in overtime in the College Football Playoff semifinals in January. Downs came within an inch of making an impact immediately in that game, intercepting J.J. McCarthy on Michigan’s first offensive play, but he landed with his toes just out of bounds. But he’s drinking from a deeper well of maize-and-blue angst now.

“There’s a hunger in the facility,” Downs says. “Not just to win against Michigan but to win every game.” (The only thing Downs needs to work on to fully fit in is eliminating the M-word from his vocabulary.)

Downs joins Ransom, Burke and senior cornerback Jordan Hancock to give Ohio State the best secondary in the land. The Buckeyes should have the top defensive line as well, with Sawyer, Tuimoloau, Williams and defensive tackle Ty Hamilton combining for 31 ½ tackles for loss and 16 ½ sacks last season. And the other instant-impact transfer from the SEC, Judkins, figures to give Ohio State the best 1-2 running back tandem in the land.

Given his starring role at Ole Miss and that program’s momentum heading into this season, Judkins was a surprise portal entry. And Ohio State might have originally seemed an unlikely destination after Henderson announced he was staying in school. But it’s a two-back world now, and the duo meshed on Judkins’s campus visit.

“I kind of put them in a room and said, ‘You guys talk through this thing,’ ” Day recalls. “They came out and they said, ‘Let’s do it.’ That was tremendous.”

Judkins has rushed for 2,725 yards and 31 touchdowns in two seasons; Henderson has 2,745 yards and 32 touchdowns in three years. Combine that pair with the usual embarrassment of receiving riches in Columbus, and whoever plays QB won’t have to do anything heroic for Ohio State to win. Howard is the presumed starter, but Day is willing to let that play out in camp. The Buckeyes’ coach also has the luxury of leaning on Kelly’s fertile mind to build an offense around whatever best suits the team’s personnel.

As startling as the Buckeyes’ player retention and acquisition moves were, poaching Kelly from UCLA might be an even bigger sign of the times in college football. Kelly is a pure football guy who rediscovered the fun of hands-on coaching when he filled in as the Bruins’ QB coach for the L.A. Bowl. In an era when being a head coach is less about ball and more about roster management, this job is a return to Kelly’s comfort zone.

“We’re sitting in a meeting room and Ryan gets pulled out to take a call about somebody in the portal,” Kelly says. “The fact that I don’t have to answer that call, that I’m still in the room working on the game plan, is what I like.”

He’s also leaving the headaches of a cross-country realignment job at a financially strapped, upper-middle-class program to be a well-paid strategist at a school with all the advantages.

“There are 130 teams that start the season saying they want to win a national championship,” Kelly says. “It’s real here. That’s one of the reasons players and coaches go to Ohio State. The unique thing about being here, there aren’t any holes.”

Still, it took a deep personal connection between Kelly and Day to make this happen. Day, 45, played quarterback at New Hampshire when Kelly was the offensive coordinator there, and Day became a fixture in the coaches’ offices as he sought to soak up knowledge from one of the pioneers of no-huddle, up-tempo football.

“He was in the facility 24/7,” Kelly says. “Every time you turned around you were like, ‘He’s here again?’ ”

This will be an interesting melding of strong-willed coaches, two guys who have had immense success drawing up plays and lighting up scoreboards. Jackson describes Kelly as an “evil scientist” concocting schemes, but the scientist himself says he’s not in Columbus to implement his own offense. He’s there to work with Day on maximizing the available personnel.

If Kelly were a Bobby Petrino–type hired gun brought onboard to save a floundering offense, it might be a tough marriage. The long-standing relationship between the two should make it easier.

“You could be in a room and argue with each other and then walk out the door with your arms around each other because there’s just trust there,” Day says. “And I learned so much from him growing up, not only as a player, but then as a coach. He’s forgotten more football than almost any coach in the game. I think he missed the coaching part of football.”

Ryan Day knows the question is coming before it’s fully articulated, and he says as much as he’s being asked it. The inquiry is about losing agonizingly close elimination games to teams that went on to win the last two national championships—Georgia in the 2022 CFP, Michigan in Ann Arbor in ’23—and finding the inches that turn those defeats into wins.

“I know what the question is,” Day says crisply in his office in July. “And I’ve thought about it long and hard. We have to leave no doubt. It can’t come down to a photo finish. It can’t come down to one field goal. If you’re a heavyweight boxer and you leave it to the judges at the end, anything can happen. We have to leave no doubt this season because we’ve been there before.”

The answer, then, is to knock out everyone. Or to at least beat enough teams to make the first 12-team playoff field—then knock out all comers. Don’t let it come down to a play-here, play-there outcome.

That’s a lot to ask, especially in an expanded and deeper Big Ten. But there are no excuses for these Buckeyes. Only expectations that must be met to rinse out the taste of rare, bitter defeats of recent years.

“Every year we’re so close to achieving our goal and still not achieving it,” Ransom says. “No one here has gold pants. Who here can say what it’s like to beat the Team Up North? No one. So instead of talking about it, let’s just work.”

Says Jackson: “Even now, I still think about the Team Up North game. I’ve probably just now gotten over the Georgia game. It certainly weighs heavy on you knowing you were right there, and the team that beat you went on to win it all. But the game of football don’t care. That’s the message of this offseason, man—the game doesn’t care, you’ve just got to win.”

Day knows as well as anyone that the game of football doesn’t care. His record is a ridiculous 56–8 overall and 39–3 in Big Ten play—legend material at most schools. Yet there is pressure heaped upon his solid shoulders. He’s 1–3 against Michigan, he hasn’t won a conference title since 2020, and he’s never won a national championship.

That needs to change. Jim Harbaugh has departed Ann Arbor for the NFL, along with most of the star players from last year’s championship team. The time is now to win the game, which will be played in Columbus.

Day doesn’t want to talk about the Stalions scandal, because talking about it is futile. With Harbaugh suspended and whatever advantage the Wolverines had gained from Stalions’s brazen spying scheme dissipated, the Buckeyes still couldn’t get it done last season in the Big House.

“At this point,” Day says, sighing, “it’s water under the bridge and there’s nothing I can do about the past. That’s probably one of the things that I’ve really tried to focus on. You learn from the past. You plan for the future.”

Michigan sent Ohio State packing last year. And planning. And paying. With a spectacular roster and coaching staff assembled, it’s time to put the plan into action. The $20 million comeback is at hand.