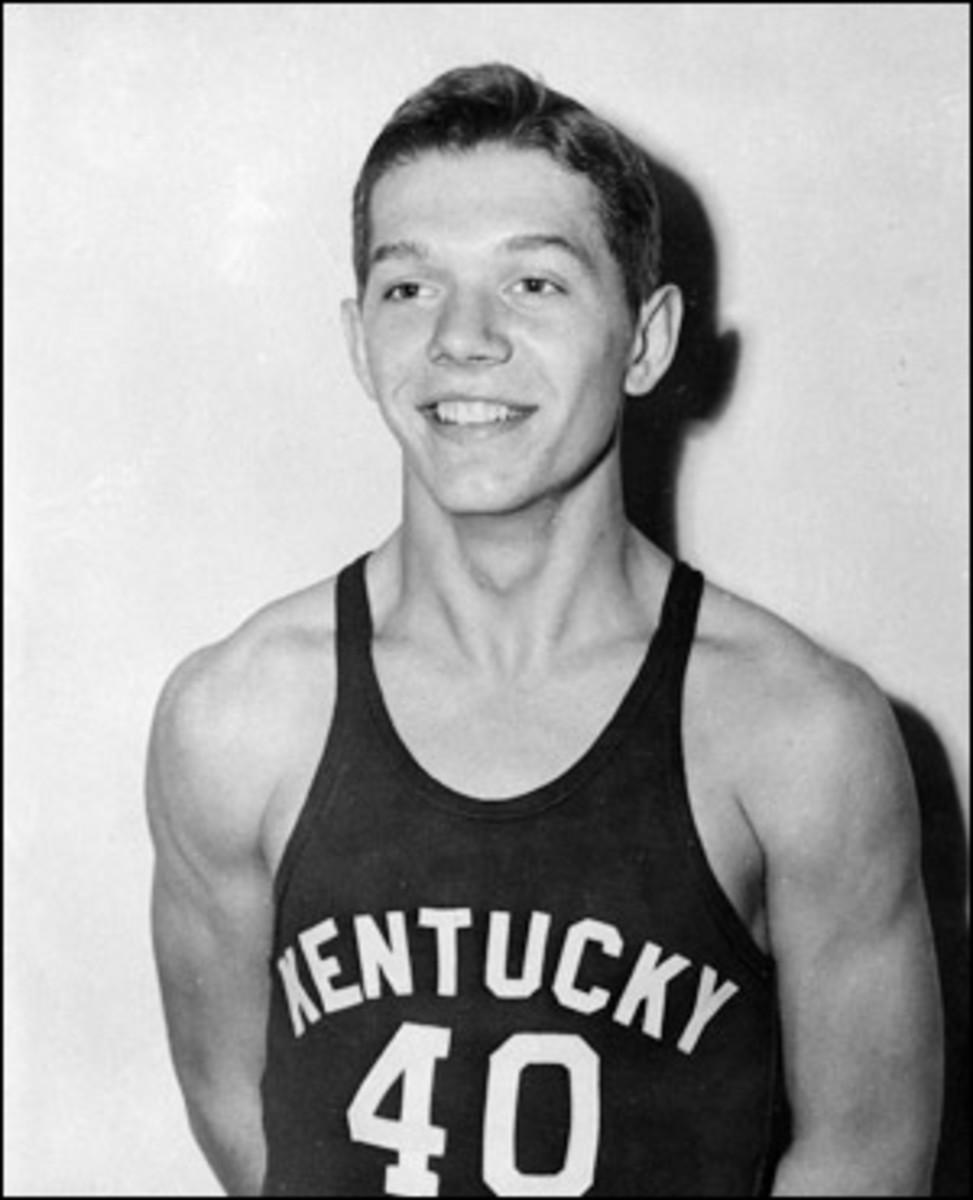

The story of Ralph Beard

One thing you have to know about Ralph Beard is that he was cheap -- and proud of it. He said he never got over what it was like to grow up poor in the Great Depression. "Podnuh," he would say, in his stuttering way, "you just don't know what it's like to be worried about where your next meal is coming from."

His buddies loved to tease Ralph about frugality, and Beard -- who died Wednesday night only days short of his 80th birthday -- laughed as hard as anybody. Everybody has a Ralph story. One of mine is the time I drove him to Bloomington, Ind., to meet Bobby Knight. Ralph brought along a brown paper sack with a couple of homemade sandwiches because he saw no reason to splurge at a pricey joint like McDonald's.

Knight had asked me to bring Ralph to an Indiana game. A basketball historian, he had listened to UK's games on 50,000-watt Louisville station WHAS when he was a kid growing up in Orrville, Ohio. He knew all about Beard. He knew that Adolph Rupp had once called Beard "the best player I've ever coached."

Before the game, Knight brought us into the locker room so he could introduce Ralph to his players. "Boys," Knight said, "this is Ralph Beard. He was the Michael Jordan of his time." Ralph ducked his head bashfully and the players looked at him a bit skeptically. Ralph was only 5-foot-10, short by today's standards, and at the time he was well into his senior years.

But Knight got it right. In his time, Ralph was the playmaker and floor leader of the UK teams that won back-to-back NCAA championships in 1948 and '49. Known as the "Fabulous Five," they revolutionized college hoops with their blazing fast-break, a far cry from the ball-control style that had been in vogue.

The team's leading scorer was Alex Groza, short for a center at 6-7 but possessed of a great hook shot and moves to the hoop. The forwards were 6-4 Wallace "Wah Wah" Jones, a fierce rebounder, and 6-3 Cliff Barker, who had learned to do tricks with the ball while being confined in a German POW camp in World War II. The other guard was 6-2 Kenny Rollins, a standout defender and complementary player.

But Beard was the straw that stirred the drink. He was lightning-quick with the ball and tenacious on defense, but his signature quality was his burning desire to win.

Beard liked to tell the story about the time Rupp gave him a defensive assignment for the next night's game and told him he expected Ralph to strangle the guy.

That night, Beard woke up in the middle of the night, clutching his pillow and saying, "Gotcha, Burl, you SOB." That was Ralph. Basketball literally was his life. Which is why everyone was so shocked to learn that he had been involved in the sordid point-shaving scandal that rocked college basketball in 1951.

At the time the scandal broke, Beard was an all-NBA guard for the Indianapolis Olympians, a team built around UK stars from the late 1950s. He and Groza were arrested as they left Chicago Stadium. They were the biggest names in a net that caught more than 30 college players, mostly from the Midwest.

Nobody claimed to be more shocked than Rupp, who had bragged, "They (the fixers) couldn't touch my boys with a 10-foot pole." He was right. They didn't need a long pole because they were right there in the UK locker room, mingling with the players after games.

The middle man between the fixers and the players was Nick "The Greek" Englisis, a New York City guy who had come to UK on a football scholarship. When it turned out he wasn't good enough to play for Bear Bryant, Englisis latched on to the basketball team, serving for a time as manager.

Another fixture around UK basketball was Ed Curd, who ran the biggest bookie joint in Lexington and one of the biggest in the Midwest. In fact, when the Kefauver commission investigating organized crime asked New York mob boss Frankie Costello who booked his basketball bets, Costello said, "My little buddy, Ed Curd, from Lexington, Kentucky."

Beard admitted he took money. But he also insisted that he never did anything to affect the outcome of a basketball game. I believed him then and always will. He was too much of a competitor to cheat. But he also was too poor to turn down a $100 bill when it was stuck in his pocket after a game.

The players' punishment was a lifetime ban from organized sports. To some, it was no big deal. To Beard, however, it was the death penalty. They might as well have put him in front of a firing squad and gotten it over with. He simply couldn't imagine life without basketball.

At times, Beard admitted to me years later, he considered suicide. The humiliation and the ban were too much to bear. He had embarrassed his mother, who had cleaned houses during his youth to support Ralph and his brother. He had let down an entire state that had come to worship him and the rest of the "Fabulous Five."

But then he found a woman who brought him stability and taught him there was life after basketball. He and Betty had two children. She was his biggest booster as Ralph received his college degree and began what was to be a long and successful career in the business world.

Born in Hardinsburg, Ralph moved to Louisville at a young age. He had one full brother and a half-brother, Frank, who had a successful career on the PGA Tour. When Ralph would talk about how hard his mother had to work to feed and cloth him, he never failed to get teary.

Beard had a stuttering problem that would become exaggerated when he got excited. He never quite got over it, but he also never let it stop him from making speeches and giving interviews.

At Male High, Beard was All-State in four sports and led the Bulldogs to the state basketball championship in 1945 . He planned on playing both football and basketball at UK, but gave up football after separating both shoulders as a freshman.

Initially, he didn't know how to handle Rupp's sarcasm. He became so upset, in fact, that at some point in his freshman year, he went to Rupp and told him he was thinking about transferring to Louisville.

"Well, by Gawd, if you want to play at the Normal school, that's fine with me," Rupp said. "But I can tell you this -- the university will not cancel its basketball schedule because you are gone."

Beard never quite got over the stigma of the point-shaving scandal, but he began to receive a measure of forgiveness and redemption when the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame inducted him in 1985. After an emotional acceptance speech, Beard looked to the ceiling and said, "Mom, I finally made it."

After that, more honors came his way. During his time as UK's athletics director in the 1990s, C.M. Newton, who had been a freshman when Beard was a senior, made it a point to honor Ralph and the "Fabulous Five" whenever he had the opportunity. He also asked Ralph to address the UK players about the evils of point-shaving, which Beard did happily and willingly.

In recent years, he attended most University of Louisville games as a regular in athletic director Tom Jurich's suite. Like Knight, Jurich appreciates sports history. Plus, Jurich thought it was important to promote better relations between U of L and UK. For Ralph's part, well, the tickets were free.

After years of feeling ashamed of what he had done, Beard always seemed amazed and grateful to find that he was remembered fondly by fans around the state. He liked to tell about the time that Bill Malone took him to a UK football game. After sitting down, Ralph turned to the man on his right, stuck out his hand and said, "Ralph Beard."

The man looked shocked. Then he grabbed Ralph's hand and said, "Ralph Beard." It turned out that his father was such a huge fan of the "Fabulous Five" that he had named his son after the team's fierce little playmaker.

To his dying day, Ralph had a conspiracy theory about the point-shaving scandal. He was convinced that Frank Hogan, the crusading New York District Attorney, had brokered a deal with Maurice Podoloff, commissioner of the NBA, and Francis Cardinal Spellman to save the stars from the big Catholic universities from being barred from the NBA. The Midwest players, Beard believed, were the scapegoats.

For many years, Beard played golf at Louisville's Hurstbourne Country Club. However, he had to grudgingly give it up in recent years due to a series of serious illnesses. His body had finally betrayed him, and Beard hated it with a passion.

Beard had a lot of scrapbooks bulging with clippings, and he was especially proud of a 1948 copy of Sports Illustrated with his photo on the cover. Fans of the magazine immediately will put up the "Inquiry" sign. The Sports Illustrated that we know and love today wasn't published until 1954. But this was a different magazine, same title, that folded after a few issues.

His most valued trophy? That was easy. "It's the gold medal from the 1948 Olympics," he said. "That was really something, to be on a team recognized as the best in the world."

I last saw him at the UK Sports Hall of Fame induction ceremony the night before the UK-Mississippi State football game. He and Betty got there late, and Ralph was moving slowly, with a bit of a limp. He shook a few hands and stopped for a few photos before heading for his table.

"I'm hurtin', podner," he told me. "I can't do anything any more. The pain is terrible."

For years, I tried to talk Ralph into doing a book with me. He wanted badly to do it, but Betty put her foot down. She saw no reason to "drag all that stuff up again," as she put it. Besides, she said, it was so long along, who cared anymore?

The other regret I have regarding Ralph is that I could never generate enough steam behind a movement to get him into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass. Newton and Knight went to bat for Ralph, as did the great sports columnist Dave Kindred and a couple of others in the media.

But somebody in the selection process always dropped the blackball on Beard. It didn't make any difference that he belonged on his merits as a player, that he had admitted his guilt and accepted his punishment, or that he had led an exemplary life after basketball. The powers-that-be at Springfield could not be swayed from the notion that he had willfully stained the game he loved.

I hope Ralph rests in peace. He deserves it. He went through a sort of living hell on earth, and I'll always believe that his punishment far exceeded his crime. Had Pete Rose been as honest and contrite about his problems as Beard was with his, Rose today would be in baseball's Hall of Fame.

Now the "Michael Jordan of his time" is gone. Heck, nobody ever minded picking up the check when Ralph was around. It was the least we could do for a man whom we loved and admired, whether he ever realized it or not.