The Chalkboard: Canisius scorer Billy Baron breaks down the pick-and-roll

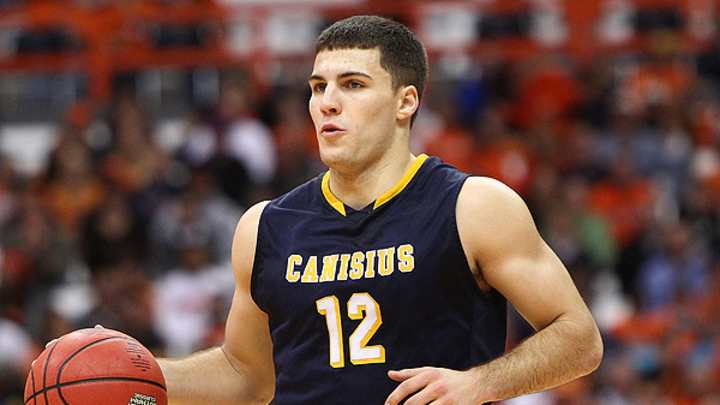

Billy Baron averages 24.9 points per game, third-best in the country. (Nate Shron/Getty)

Before every game, Billy Baron begins a film session by going to YouTube. For the next 30 minutes or so, he digests clips of Golden State Warriors guard Stephen Curry. Baron narrows his focus to a specific choreography on the offensive end: How Curry attacks the screen-and-roll, the most basic of basketball sets, a simple action with multiple nuances that can baffle a defense no matter how many times it is run.

For Baron, these clips are an instruction video. The nation’s third-leading scorer as of Friday morning at 24.9 points per game, Canisius’ senior guard utilizes a high ball screen to fuel most of his team's offense. The Golden Griffins call a few set plays, but largely it is Baron with the ball in his hands, diagnosing how a team will defend that pick-and-roll, and proceeding accordingly.

“That’s big, that’s like the engine right there,” Baron said. “Personally, I feel that’s my biggest strength, is working that pick and roll. Not necessarily because I’m the quickest guy in the world or anything like that. I just know what moves to make, what reads to make. I know what’s going to happen.”

Baron broke down just how he knows what he knows -- the various reads and keys and reactions involved in playing off a simple screen and how he maximizes what he sees.

The setup. First, Baron watches film of the other team to assess its tendencies, particularly against the screen-and-roll. The off-ball defender is likely to hedge the screen to one degree or another, which is the next cue for how Baron will approach a game.

“When I know that, I know the roll man is going to be open, and then you have to look at that (weak-side) man,” Baron said. “But when they do a terrible job of hedging, when they don’t hit me on the high ball screen and they give me a little room, I’m definitely looking to make a play for myself.”

But Baron also has engaged in self-improvement in his approach: He used to back down his defender into the screen but eventually realized that eliminated any momentum he had going towards the rim. Now Baron uses sharper angles to bring his defender into the screen. “Now when I face up my man, it allows me to turn down the ball screen, it also allows me to slip the ball screen, which I’ve been doing a ton of times this year,” Baron said. “It helps me get around that hedge man and shoot a quick three if my guy is late getting under that screen. Then when double-teams come, it's easier for me to see.”

The reads. The defender guarding Baron isn’t the focus as Baron initiates the screen-and-roll action. The player assigned to the guy setting the pick tells all at the start. Baron zeroes in on the big guy, how he’s going to hedge, whether he’s slow-footed or not, and that dictates the next set of decisions. If he gives Baron room, up goes a three-pointer – a shot he's made 42.8 percent of the time this year. If not?

Then it’s a third component that subtly represents the key to finishing the play. If Baron comes around a screen, inevitably a team will have a wing defender slough off his man to limit penetration. “You’re really reading that help defender,” Baron said. “If you get around that hard hedge man to prevent you from letting go a 3, you’re going to have your roll man open, or you’re going to have that weak-side guard in the corner who should be a shooter. In that case, it’s usually Zach Lewis for us. He’s going to be in the corner spotting up. I tell him, every single time I pass him the ball, if he doesn’t shoot it I’m going to yell at him.”

It is that help defender whom Baron must attack and deceive. He recalled a sequence in a tight loss at Notre Dame earlier this year in which he told Lewis to bring his man higher, out of the corner and into a spot on the wing. Baron wanted more room to hit the roll man down the middle. Once he dribbled around the screen, and once Lewis fired up from the corner, he got it – an easy dump-off into the lane.

“It was basically playing mind games with the weak-side defender,” Baron said. “If I’m doing my job, the guy hedging the screen and my man don’t really come into play. It’s all about that weak-side defender. Whatever he’s going to bite on, I hit the other guy.”

The adjustments. There is precious little Baron can do if a team elects to play zone, and little he can do if a team such as Manhattan runs two defenders at him once he passes mid-court in an effort to get the ball out of his hands. But then there was Marist, coached by former NBA coach and general manager Jeff Bower, who defended the screen-and-roll like many professional teams will: The defender assigned to Baron jumped to the high side as the screen came, leaving Baron somewhat boxed in but also face-up against a big man. In that case, he had to put his head down and split the defenders to go to work. He wound up scoring 38 points that night.

“Just because I was able to be very aggressive and split that ball screen very consistently,” Baron said. “You have to take advantage of the big man and how they’re not as quick. And I just have to be confident in myself and be much more aggressive.”

Also, often enough in the second half of games, Baron will detect or assume some weariness is setting in on the big man hedging the screen. If he also knows a team is near the foul limit, instead of working around the defender, he initiates contact. It is an unapologetic attempt to take advantage of the freedom-of-movement emphasis to draw fouls and head to the line. “The simplest thing becomes harder in the second half once fatigue sets in,” Baron said.

The finish. Canisius isn’t the most efficient offense in the country nor even in the MAAC, sitting behind Iona and Quinnipiac in the kenpom.com adjusted efficiency rankings.

But its 110.7 points per 100 possessions nevertheless puts it ahead of the likes of SMU, Providence, Marquette, Ohio State and Cincinnati. What drives that is a simple sequence and an operator studying its nuances on a daily basis.