Utah basketball team finds a friend and mentor in 8-year-old Mac Brennan

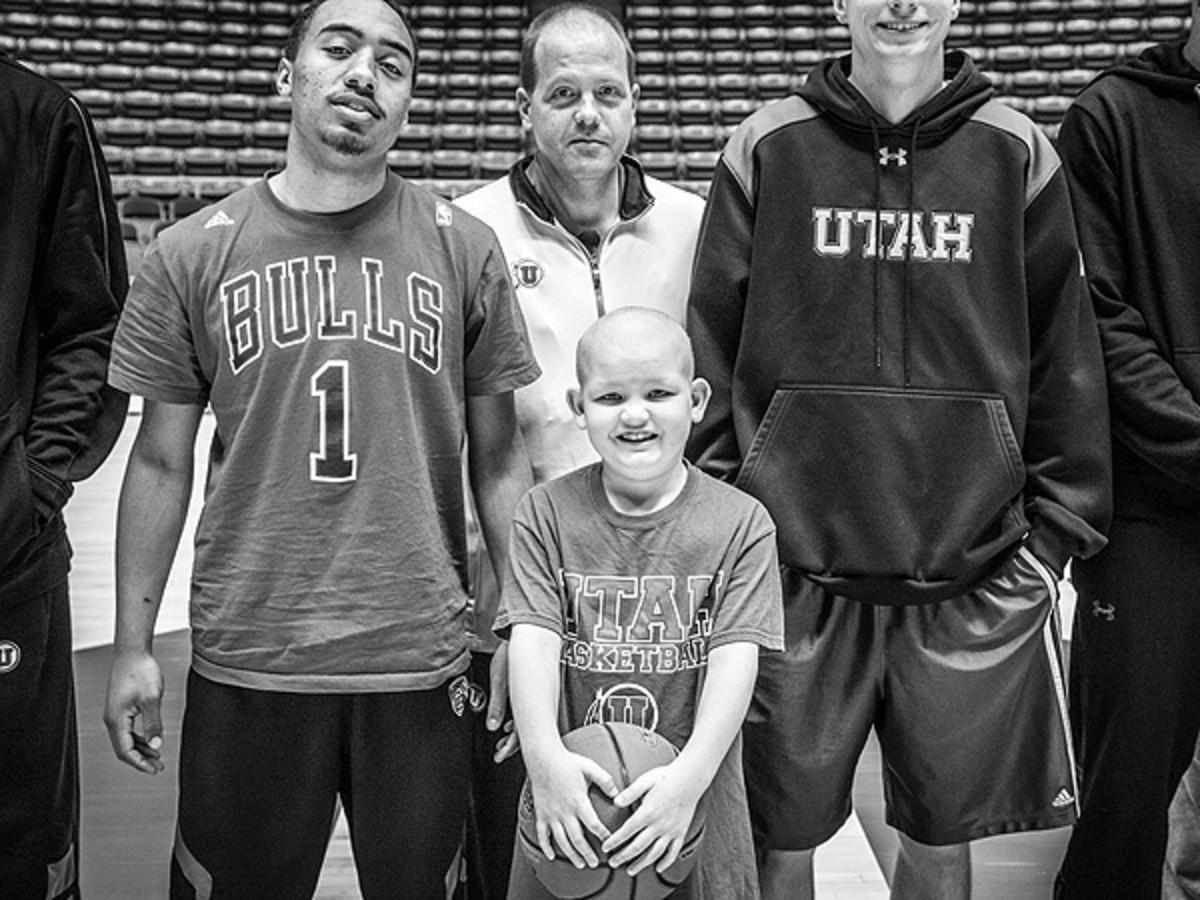

Macguire Brennan (center) has become an inspiration for the Utah basketball team. (Kory Mortensen/Utah Athletics)

Macguire Brennan, known to most as Mac, begins his days in his father’s office at Utah’s Hunstman Center around 8 a.m., doing homework. Sometimes he takes tests he missed at school. Once he finishes his assignments, usually after a couple hours, he walks into the concourse and down the steep stairs to the gym floor. And he starts shooting.

He returns for lunch with his father, Kyle, the school’s senior associate athletics director for administration. But when Utah’s basketball team begins afternoon practice, Mac walks back down and starts shooting again. He chats with the Utes about the teams they played and video games and Batman. Sometimes he plays two-on-two or one-on-one, either against players or coach Larry Krystkowiak's sons.

Sometimes they talk about the leukemia, too, about how Mac is feeling and what treatment he’s had lately and what he does at the hospital. It’s been more than two months now since unfaltering, eight-year-old Mac was too tired to finish a youth league basketball game. His suspicious father felt lumps on his neck and under his arms the next day. After that, a doctor diagnosed Mac within an hour and booked him into a hospital within two.

On average, Mac has chemotherapy five days a week. To make delivery of the drugs easier, many children and families opt for “access.” There’s a port inserted usually up by the collarbone, and a tube inserted into that. It stays that way, to avoid the discomfort of putting a line in every day.

Mac first demanded that the port be inserted lower, by his rib cage, because otherwise it would rub against his football pads this fall. And then he refused “access.” If he had it, he wouldn’t be as able to shoot with his two brothers or the Utes. The doctors and nurses advised it would be much easier to keep the tube in, much less uncomfortable. Mac said it was OK. He didn’t mind.

“He asked for it to be taken out every single day,” Kyle Brennan said, “so he can play.”

*****

Utah has had an up-and-down third season as a Pac-12 member, winning all but one non-conference game before amassing a 7-8 league record heading into a visit from Colorado on Saturday. The Utes have posted both a three-game losing streak and a three-game winning streak in Pac-12 play. They have lost to moribund Washington State, they have beaten UCLA and Arizona State and they have taken then-No. 4 Arizona to overtime.

There is a constant, though: Mac Brennan walking into the gym every day, hoisting shots and providing a lift.

“He shows up relentlessly, man,” Utah sophomore guard Brandon Taylor said. “He has one of the greatest spirits I’ve come across in my life.”

The season has been instructive in many ways about the energy and conviction required to carry on. There are the 18 wins and the nine losses. There is longtime trainer Trevor Jameson, waging his own battle with cancer and now frequently unable to travel with a team that named one pressure defense “T.J.” in his honor. And there is little Mac, hanging with the Utes, and both sides feeling better for it.

Kyle Brennan sent Krystkowiak a text message during the early stages of Mac’s hospital treatments, indicating that Mac had lost his appetite and a fraction of his spirit. Soon after, the Utes players trekked to his hospital room as a group, bringing beanies and posters and basketball cards and listening to Mac recount the various medications he received during the day. It was the first time most of the players had met Mac.

During that hospital visit, Mac told the players about his medication and school and assured them not to worry, that he’d attending games in a hurry. “He acted like we knew him forever, really,” sophomore forward Jordan Loveridge said. When his mother, Beth, suggested it might be unwise for a leukemia patient to immerse himself in a crowd of thousands and expose himself to all those germs, Mac told the Utes his mom wouldn’t let him go to games. But maybe he’d come to a practice instead, he said, where the risk was mitigated.

When Krystkowiak learned Mac’s appetite and energy returned after that visit, he decided: The Utes could help.

"It just kind of hit us right in the stomach," said Krystowiak, the father of three sons and twin daughters. "I can’t imagine having any of my kids undergo something like this. Mac’s a little athletic-minded kid. We just wanted to make sure he had an outlet with missing some school. That he knew he was part of a team. Nobody’s looking at Mac as sick little kid that needs sympathy. He’s one of the guys."

When Mac began his daily visits, a rapport grew quickly. It should be no surprise; size differences aside, it is just a little kid talking to the big kids.

"At first it was difficult to talk to him, because all these emotions are involved," Taylor said. "In the back of your mind, you do have this sense of he’s going through a tough time right now. But he doesn’t make you feel that way at all. He makes you feel like he’s a regular little kid. Which he is."

For example: Mac Brennan loves Batman.

So does 7-foot, 258-pound junior center Dallin Bachynski.

So when Mac and Dallin talk, they talk about basketball, and then they talk about "Batman stuff."

"Batman stuff is kind of how cool he is, how he’s the best superhero, how he would totally beat Superman or any other superhero," Bachynski said. "Stuff like that."

Mac is also a source of advice, solicited or otherwise. He once saw Taylor miss a free throw, determined Taylor was not bending his knees adequately and told him so. Taylor hit the next attempt and Mac smiled.

Likewise, Loveridge, the Utes’ second-leading scorer, occasionally pauses before shots to address a captive audience nearby.

Mac, you think I’ll make this? Loveridge asks.

Yeah, you usually do, so just shoot it like you usually do, Mac says.

These are the light moments. A kid who misses school friends and misses sports finds a version of both every afternoon. The Utes insist what they get in return is not the point. Still, they have come to understand what they have by seeing what Mac has lost. It’s a message Krystkowiak has sent before road games with Jameson unable to travel as he had for years, and with Mac watching from home: play your balls off, he tells his team, but appreciate how lucky you are.

Sometimes, an 8-year-old delivers the message more gently. Before one practice this year, Mac and Loveridge began discussing Mac’s favorite teams. Loveridge then asked Mac who his favorite player was. Mac said it was Ray Allen. Then he paused.

But my favorite college player is you, Mac continued. When I play, I always try to play like you.

"When I see him in the gym, I want to not let him down," Loveridge said. "It just gets you going every day. If you’re having a slow day or a hard time getting started, you just see someone like that, and you just know how fortunate you are and how bad he would want to feel 100 percent all the time."

The Utes enter the gym after miserable road trips or gutting overtime losses, grumbling like any dissatisfied team would. And there is little Mac, always, ready for a game of one-on-one or just to say "What’s up?" Everyone shows up to play, and to take their minds off it all.

"If he was able to play basketball," Bachynski said, "he would be the happiest kid you’ve ever seen."

*****

Mac played basketball aggressively, tracking how many times he dove for loose balls per game. (Kory Mortensen/Utah Athletics)

Mac Brennan is a typical middle child: Steeled enough never to back down from his older brother, Patrick, and compassionate enough to let little brother Murphy win sometimes. But when he played sports – and he played all of them, football, basketball and baseball – he played aggressively, like he was surrounded by rampaging older siblings. Mac once found a YouTube video of Larry Bird chasing a loose ball from half-court to the baseline, diving head first after it with no real chance to retrieve it. Mac loved that play. So, every game, he began keeping track of how many times he dove for loose balls.

Which is why Kyle Brennan began to worry when he saw his son ask out of a game.

For two or three weeks, he had noticed one BB-sized bump behind each of Mac’s ears. Mac complained about them, but his parents figured it was a symptom of a cold or flu and thought little of it. Then Mac began to look more fatigued than usual during youth league basketball. On this particular December night, he led the Salt Lake East Leopards in scoring and hit a halftime buzzer-beating shot, but he wasn’t playing much defense. Kyle scolded him for that at halftime. Mac responded that he didn’t have any energy. He felt tired.

About a minute into the third quarter, Mac asked to come out of the game.

A little later, the coach asked if he wanted to go back in. Mac said no.

The next day, Kyle asked to feel the lumps again. Then he began pressing on Mac’s neck.

More bumps, maybe the size of a quarter, two on each side.

Then Kyle felt under Mac’s arms. More bumps.

The Brennans brought Mac to the pediatrician. Their normal doctor was not in. So it was a younger, unfamiliar physician who examined Mac.

"Within two seconds, she’s like, I think he has leukemia," Kyle Brennan says. "I’m like, hey, hold on! Where’s our regular doctor? What are you talking about? He was at school that morning and the day before, playing ball, and then all of a sudden…"

All of a sudden, on Dec. 13, Mac Brennan checked into a hospital. The Brennans rediscovered clues they didn’t know were clues. The rash on Mac’s torso they attributed to his egg or nut allergies was a result of low platelet counts. The pain in knees and other joints was not typical of a growing or complaining kid but a symptom of the disease in his bones.

Their son had leukemia, he was in a hospital, and he would begin chemotherapy the next day.

"The one blessing of it was, you know you sometimes go in for tests and they say, ‘We’ll get back to you in a week,’ and then they don’t call you," Kyle Brennan said. “There wasn’t a lot of time to worry. It’s just happening. You don’t have that chance to look at the research or anything like that. You just know your kid has leukemia."

Mac spent 10 days of the first 28-day chemotherapy regiment in the hospital. He did intravenous chemo every day. Nearly every other day, he also underwent "back pokes," in which he was sedated as doctors inserted chemotherapy drugs into his spinal cord so the medicine would travel to his brain and eradicate the disease there.

As part of the overall treatment, Mac received a regular steroid dosage. Mac was never a big eater but the drugs supercharged his appetite during that first month. The first night the steroids really took effect, the Brennans went to McDonald’s. Mac ordered two double cheeseburgers, two large fries and a 20-piece Chicken McNuggets. He ate it all. An hour or two later, he wanted to eat again.

In the weeks after, Kyle Brennan guessed he spent $50 a day on groceries. He would buy a package of sausage and hash browns and bacon at the grocery store, Mac would clean his plate of that, and two hours later he would crave a slab of red meat. “He ate so much steak it was ridiculous,” Kyle Brennan said. “He didn’t want the cheap stuff, either. So we were getting ribeyes daily.”

Mac became bloated, his face puffy, his heart pounding and his breathing labored. It was a strenuous course but necessary to achieve the goal for a standard-risk patient: remission after 28 days.

After 28 days, the leukemia was not in remission.

So Mac Brennan now has more intensive chemotherapy, which he will continue for the next nine months. After that, it’s once a month for three and a half years. He is currently in a high-risk category for relapse -- meaning the prognosis drops significantly -- but the leukemia has the highest cure rate in childhood cancer. Everyone is hopeful the plan will work. Still, following the initial diagnosis, Kyle Brennan said he and his wife grieved for a month over the grim path their son faced. "You wish you could have it instead," Kyle Brennan said. "You can’t take it away for him. If I could, I’d go in and get treatment and take it for him. But you can’t."

So they surrendered to the idea that all they could do was show Mac how tough and brave they could be.

He just beat them to it.

Mac doesn’t complain. When people mention that he is bald, he reminds them Michael Jordan was, too. When Utah’s football coaches visited his hospital room and asked how everything was, Mac cheerily replied, "I’m OK, I’m just fighting the cancer!"

And once his assignments are done, Mac leaves his father’s office and plays out his new normal.

"I think he gets a sense of belonging,” Kyle Brennan said. “It kind of gives him a purpose to his day, his week. Something that he’s involved in when all that has been stripped away."

*****

Mac Brennan has been waiting anxiously, his father says, to get on the phone.

There is a lively squeak in his voice, and he talks in the hyper-literal way of an 8-year-old, his answers an unredacted transcript of life.

"I’m feeling good," Mac said. "I’m basically just sitting at my Dad’s work, or down at the gym."

It’s fun to be down at the gym, Mac reports. The players usually say "How are you doing?" and ask about his treatment. When they talk about Madden 25 and games like that, it must be because they saw him playing an Xbox when they visited him in the hospital and guessed that he liked to play video games, too.

When Mac watches practice, he picks up on the choreography of each call. He also figured out that when the Utes run plays he doesn’t think he’s ever heard of, those are the plays the other team runs, and the players just want to be ready for them. He also has informed Krystkowiak, after Utah lost a couple late leads, that the coach needed to get his team to learn how to win games at the end. Krystkowiak said he’d be sure to pass that along.

What Mac does, what he says -- it’s considered part of the routine now. It is all welcome, every day, start to finish.

“It’s really surprising, because I’ve never met them,” Mac said. “Once I went to that first practice, I really knew them. I felt like they were all my best friends.”

At the end of each practice, Krystkowiak walks to the 'U' at midcourt and his team runs in at the whistle for a post-practice talk. Mac usually hangs out nearby to listen, along with the rest of the staff and the managers.

When that’s done, the Utes thrust their hands into the middle of the circle for a three-count and a cheer. The cheer is not always the same. And three or four times, Mac Brennan has been asked to choose what everyone says at the end.

The last time Mac did this was about two weeks ago. Krystkowiak finished his speech to the team and sought out the kid on the fringes, looking for the last word.

“Mac,” Utah’s coach said, “what do you got to end practice today?”

Mac Brennan paused for a moment, then gave his answer.

“Brothers.”

Mac with his Utah basketball family. (Kory Mortensen/Utah Athletics)