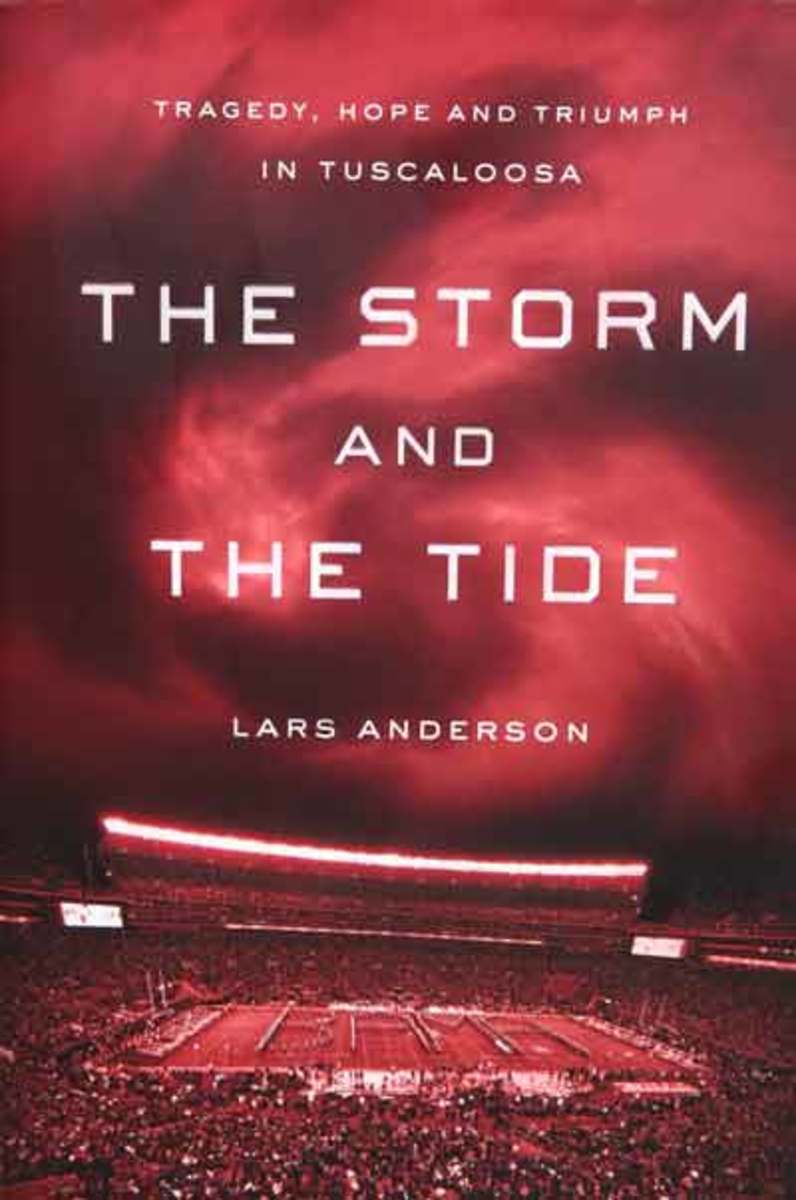

The Storm and the Tide: a look back at tornados that ravaged Tuscaloosa

Excerpted from THE STORM AND THE TIDE by Lars Anderson. Published by SI Books, an imprint of Time Home Entertainment Inc. Copyright © 2014 by Lars Anderson. Available wherever books are sold.

Loryn Brown was about to step into her Crimson-colored dream. Ever since she was three years old and growing up in Tuscaloosa, she had wanted to attend Alabama.

On the morning of April 27, 2011, Loryn was in her rented three-bedroom house at 51 Beverly Heights in Tuscaloosa, a house shaded by oak and pine trees that stretched 80 feet into the sky; Loryn shared the place with two roommates. Her final test of the semester at nearby Shelton State Community College was later that evening. Loryn, 21, wanted to become a sports broadcaster, and she had already been accepted at Alabama, where she intended to enroll the coming fall. Her plan for the day was to study in the house, then drive the two miles to the Shelton State campus for her 6:30 exam.

The crimson ran deep in Loryn’s blood. Her father, Shannon Brown, had been a backup defensive lineman on the Tide’s 1992 national championship squad and a team captain in ’95. Loryn, who’d been born when her father and mother, Ashley, were students at Stanhope Elmore High in Millbrook, Ala., never missed a home game. Wearing her daddy’s jersey, she’d sit on her mother’s lap in Bryant-Denny Stadium and point at her father on the field. After the games she’d wait outside the locker room with her mom and run into her daddy’s arms as soon as she spotted him. He was her hero.

LARS ANDERSON: Writing The Storm and The Tide was a deeply personal experience

Loryn, with her dark curly hair and dimpled cheeks, even melted the heart of Alabama coach Gene Stallings, a notorious curmudgeon. Before the Sugar Bowl game against Miami that would decide the ’92 national title -- underdog Alabama would defeat the No. 1 Hurricanes 34-13 -- Loryn dined with the Tide at the pregame meal in their New Orleans hotel. Loryn had just learned the “show-your-food trick,” as her mother called it, and midway through the meal she stood on her chair and yelled out, “Hey, Coach Stallings!” Once she had the coach’s attention, Loryn, dressed in an Alabama cheerleader’s outfit, opened her mouth wide to show the piece of steak she was chewing. The coach nearly fell out of his chair in a fit of laughter. The moment lightened the mood, and some players would later swear that it relaxed the team. Nearly two decades later, she was still the consummate fan.

Like so many people throughout Alabama, Loryn had awakened early in the morning of April 27 to crackling thunder. The power in the house had flickered on and off. She called her mother, Ashley Mims, now remarried and living in Wetumpka, Ala., a town about two hours to the southeast. Loryn always phoned her mom when storms threatened. “Mama, can you pull up the weather on your phone?” Loryn asked. “We’re having a bad storm. What’s going on?”

Ashley Mims looked at her phone. There was a triangle-shaped storm over Tuscaloosa, but it appeared small. “Oh, baby, you’ll be fine,” she said. “It will blow over in a minute.” She was right.

But a few hours later she read another weather report. This one suggested that conditions in Tuscaloosa would be favorable for tornadoes later in the afternoon. Ashley asked Loryn if she should come pick her up. “No, Mama,” Loryn said. “I don’t want you to get stuck somewhere. I don’t want you on the road. I’ll be fine.”

For the rest of the afternoon, Loryn stayed in her bedroom, cramming for her exam. From her living room, Loryn’s mother flipped between news stations, which had cameras mounted in downtown Tuscaloosa. At 5:12, her heart jackhammering with fear, Ashley called her daughter. “Baby, it’s coming right at you!” she said in a panicked voice. “Get your head down.”

“Mama, I’m scared,” Loryn said.

Loryn and her friends moved to a center hallway on the first floor of the house, with her mother still on the phone. Ashley could hear Will Stevens, a close friend who had come over, telling Loryn and her roommate Danielle Downs that everything would be fine, that they had to have faith, that they needed to be strong.

“It’s going to be O.K., baby,” Ashley told her daughter over the phone. “It’s going to be O.K.”

“I’m scared, Mama,” Loryn said, clutching a pillow over her head. “It’s just black outside. It’s just black.”

Then the line went dead. It was 5:13 p.m.

*****

Defending champ Florida State leads SI preseason college football Top 25

Just past 6 p.m. on the day of the storm, Shannon Brown called his ex‑wife. Shannon was at his home outside of Huntsville in Madison, Ala., 150 miles to the northeast of Tuscaloosa; he was now the football coach at Ardmore High, and remarried with two other children. “Have you heard from Loryn?” Shannon asked.

“I was on the phone with her, and it cut off,” Ashley replied, shaken.

“Ashley, I’m sure she’s O.K.,” Shannon said.

“Shannon, if she was O.K., she’d crawl out of the rubble to let her mama know that she was fine.”

After hanging up, Shannon phoned Diane Rumanek, the mother of Loryn’s other roommate, Kelli, and the owner of the house they rented. “Can you go to the house and call me back?” Shannon asked.

“We’re getting worried.”

Rumanek phoned later that evening with bad news. “I’m sorry, Shannon,” she said. “I can’t get there. The streets are blocked with trees and power lines. I thought everyone was fine. I had no idea. It looks like a bomb went off.”

Shannon’s father, Jerry Brown, lives 40 miles south of Tuscaloosa in Greensboro and owns a company called Blackbelt Tree Service. Having learned that no one could reach Loryn, Jerry hitched up his tree-cutting equipment; if necessary, he would carve a path to reach his granddaughter’s house. Before long, Jerry and his grandson Chad Richey were driving to Tuscaloosa to find Shannon’s little girl.

Shannon was a mess of jangled nerves. His hands trembled and his legs shook as he prepared to leave home for Tuscaloosa. His thoughts drifted back to the last phone conversation he’d had with Loryn. She had recently informed him that she planned on majoring in journalism at Alabama. Shannon had made a deal with her: If she made good grades, he would take care of her financial needs. “I am so proud of you,” Shannon had told her. “I love you so much.”

“You have no idea how much that means to me,” Loryn had replied. “I love you too, Daddy.”

When Shannon was named a team captain for the 1995 season, it meant he would be able to leave a permanent mark on Tuscaloosa by putting his handprint and footprint in cement at the base of Denny Chimes -- a 118‑foot bell tower built in 1929 on the south side of the Quad, the vast green lawn in the heart of campus. His prints would join those of all the other Crimson Tide team captains. On the day of the ceremony, Shannon carried his daughter, resplendent in a blue dress with yellow sunflowers and her dark curls, to the Chimes. He set her down and placed his left hand in the soft, wet cement. Loryn crawled next to her daddy and helped him press his fingers down. Afterward, holding Loryn, Shannon spoke to a crowd of several thousand. “I just want to thank Coach Stallings for taking a chance on me,” Shannon said. “I was married and I had this little girl, and that didn’t stop Coach from asking me to come here. I’ll forever be grateful.”

Loryn, as she grew older, typically started her personal countdown to Alabama’s opening game of the season in April. From Tuscaloosa she would tell Ashley over the phone, “Mama, it’s only 127 days until game day!” On fall Saturdays, Loryn would always stop by the Chimes to place her hand in her father’s print. Nothing made her happier.

*****

Jerry Brown and Chad Richey arrived in Tuscaloosa at dusk; downed trees and power lines blocked many of the roads into town. The men hacked their way toward Loryn’s house on Beverly Heights. Power in the area was out, leaving the neighborhood dark and unrecognizable. Even the police were barricaded by the debris; seeing Jerry and his equipment, the officers encouraged him to continue his work. Jerry was determined to reach his granddaughter.

By the time Shannon arrived in the area, a police blockade prevented him from getting near Loryn’s house. Shannon demanded that the police let him through. “My daughter is in there,” he pleaded. Eventually one of the officers escorted the distraught father to his daughter’s house.

There, in the back of an ambulance, Shannon saw two bodies carefully wrapped in blankets. (He would soon learn that they were the bodies of Downs and Stevens.) Just then an officer, driving a small utility tractor, pulled up. Another casualty was wrapped in a green comforter in the back of the vehicle. An officer approached Shannon with photos on a digital camera, photos of the three victims from the house, and asked Shannon if he would look at them to see if one was his daughter. He took the camera in his quaking hands, and as soon as he saw the dark curly hair, the devastating reality came crashing down on him.

Shannon stumbled backward. He screamed, producing a wail so loud it may well have carried all the way to Bryant-Denny. He swung his fists, wanting to hit something, anything. His father grabbed him and hugged his son tighter than he ever had before. In that instant something deep inside Shannon Brown left him, escaping into the nighttime air, never to return.

No one could say anything to Shannon now that would really matter. How could they? There was no meaningful relief from the pain he was feeling. He had trouble remembering things he’d done five minutes earlier and felt as if he were merely drifting about in the world, emotionless and empty. So when a private number popped up on his cell a few days later he considered not answering. But for some reason he lifted the phone to his ear and said, “Hello?”

“Shannon, this is Nick Saban,” said the voice on the other end of the line. “I’m so, so sorry for your loss. There’s nothing I can say that will make you feel any better, but just know that the entire Alabama family is here for you. You’re a great ambassador for us. If there is anything that I can ever do for you, please call me. I’m here for you, Shannon. You call me, you hear?”

Brown was moved. Here was Saban, whom he barely knew, reminding him that he wasn’t alone, that the arms of his football family were extended. The call was like a shot of adrenaline -- Saban’s voice did make him feel momentarily better, but the pain quickly returned, still crippling in intensity.

There were others from the Alabama family who reached out to Shannon. The phone calls were heartfelt, and appreciated. Still, Shannon felt a darkness closing in around him. His girl was gone, and no words could change that. He didn’t want to go out. He didn’t want to see people who would try to console him. He just wanted to be alone.

*****

If there were a statute of limitations on grief, Shannon Brown would have welcomed it. Six months after his daughter’s death, he still caught himself searching for her face in a crowd, still turned expectantly when he thought he heard her voice come out of thin air.

The day before Alabama’s Oct. 8 game against Vanderbilt, Shannon packed an overnight bag at his home in Madison and began the 2 1⁄2-hour drive to Tuscaloosa. Traveling this same road had once been charged with anticipation; now it elicited conflicting emotions. He really didn’t like spending time in T‑Town anymore; invariably he would be stricken by the image of himself identifying Loryn’s body. But he also missed seeing his teammates. The five years he’d spent playing football at Alabama were some of the best of his life, and even now there was some comfort in remembering those days with his buddies, recalling the whole-body shiver of excitement that came with running out in front of 80,000 roaring fans. As he neared Tuscaloosa he just felt scared—scared that the bad memories would simply overwhelm the good ones.

During Shannon’s junior year at Alabama, when Loryn was four, he and Ashley had divorced; they’d married so young, too young, and it wasn’t working anymore. But they shared their devotion to Loryn, and whenever Alabama had an open date during the season, Shannon would take his daughter to the zoo or jump on a trampoline with her or even join her to play with her Barbie dolls. For the rest of his college career he spent every other weekend with his daughter.

Now he checked into the Hotel Capstone -- the same place he used to stay with his teammates before games -- and after dropping off his bags, he walked to the Quad for a barbecue under a tent on this cool, bright afternoon. The old stories flowed even as dusk settled and the temperature dropped. To Brown, it felt almost like being with the guys back in the locker room again.

Almost. Several of Loryn’s friends stopped by the tent. They hugged Shannon tight, and each time he didn’t want to let go; each time it gave him the sensation that he was embracing his daughter. The girls talked about everything they missed most about Loryn: her great laugh, her sassiness, her kindness.

At 10 a.m. that Saturday, 300 people filled Moody Hall. Shannon and Ashley walked onto the stage and were presented with a certificate from the University of Alabama Alumni Association. It stated that the Loryn Alexandria Brown Memorial Scholarship had achieved endowed status that would carry on in perpetuity. Shannon and Ashley had worked diligently to raise money, getting generous donations from alumni, friends and family, for a scholarship that would cover the cost of a student’s freshman year; it had brought them closer than they’d been in almost two decades.

On the stage Shannon said, “It feels so good to know that Loryn is now forever at Alabama. We had so many wonderful times together here. This would mean so much to her.”

After the ceremony Shannon strolled over to Denny Chimes. A breeze ruffled the orange and yellow leaves on the grand oaks that shaded the Quad. It was difficult being here at the Chimes, but he also felt the presence of Loryn. He stayed until it was time to go to the stadium.

Five minutes before kickoff, the stadium was full, and Shannon walked onto the field. He had been named an honorary team captain for this game, and as he waited on the sideline for the coin toss ceremony to begin, running back Trent Richardson came over and shook his hand. Shannon said, “Hey, buddy, good luck. Don’t ever underestimate this experience.”

“No, sir, I won’t,” Richardson replied. “I thank the good Lord every day.”

Shannon trotted out to midfield, where he joined Alabama game captains Dont’a Hightower, Mark Barron, Marquis Maze and Alex Watkins. Before the referee flipped the coin, the announcer introduced Shannon and told the crowd that his daughter Loryn had died in the tornado. The introduction brought 101,000 fans to their feet, and they clapped and whistled, a resounding salute. Shannon had a familiar sensation, the back-of-the-neck hair-raising rush he’d felt so often on this field as a player. He stepped forward in his houndstooth sport coat and red tie and lifted his right arm to acknowledge the crowd. But there was no smile.

Back on the Alabama sideline, Shannon could feel something different about this team. He had gone through training camp in 1996 with the Falcons before a knee injury ended his career, but he had been around the NFL long enough to know that those players never had the look in their eyes that these Alabama kids did. Everyone on this Tide team exuded a passion and an intensity that Shannon had never before seen, not even on his squad that won the national championship in 1992.

For the first time since the tornado, Ashley Mims was also at Bryant-Denny. Before kickoff, as she watched her ex‑husband being honored below, she thought, of course, of Loryn sitting in her lap in her cheerleading uniform as they rooted for Daddy down on the field.

By halftime she had to leave. “It’s just too hard,” she told a companion. “As exciting as it is being back here, it’s too much. I just can’t stay. I can’t.”

*****

Shannon decided to throw a party, albeit a small one. Even the smallest steps were moving him in the direction of healing. He invited a few of his close friends to come to his house on Jan. 9, 2012, the night of the title game. There was zero doubt in his mind that Alabama would win, and with relative ease, he thought. (He was right: The Tide avenged its only loss of the season, beating LSU 21-0.) The Tide had been given a second chance against LSU, and Brown understood exactly what that would mean to the team. “The tornado made this season personal to the players and to Saban,” Shannon told his friends. “I saw it in their eyes when I was on the field for the homecoming game. They knew they could make a difference and give Tuscaloosa something to be proud of. There is no way they’re going to let Tuscaloosa down.”

His friends, of course, wanted to know how he was holding up. Shannon hadn’t sought professional help, but there were signs of improvement. Best of all was being around his two other children. As for his oldest daughter, he told his friends, “It’s not easy. It will never be easy. I just hope no one has to go through what Loryn’s mother and I have gone through.”

He settled into a living room chair and waited for kickoff. For three hours he could lose himself.

To purchase a copy of The Storm and The Tide, go here.