Beyond the image: Kliff Kingsbury's path to Texas Tech and back again

LUBBOCK, Texas -- Kliff Kingsbury, he of the V-neck shirts and Oakley sunglasses, the hottest bachelor and coolest personality in college football, can’t sleep.

The Texas Tech coach tosses and turns until 5 a.m. -- a late morning, if you know him -- before giving up and going into the office. He doesn’t believe in regrets, but spends most of Sept. 14 studying a sheet of plays he didn’t call, nagged by the feeling that Arkansas, which hung 438 rushing yards on Texas Tech in a 49-28 rout the day before, was not 21 points better than his Red Raiders.

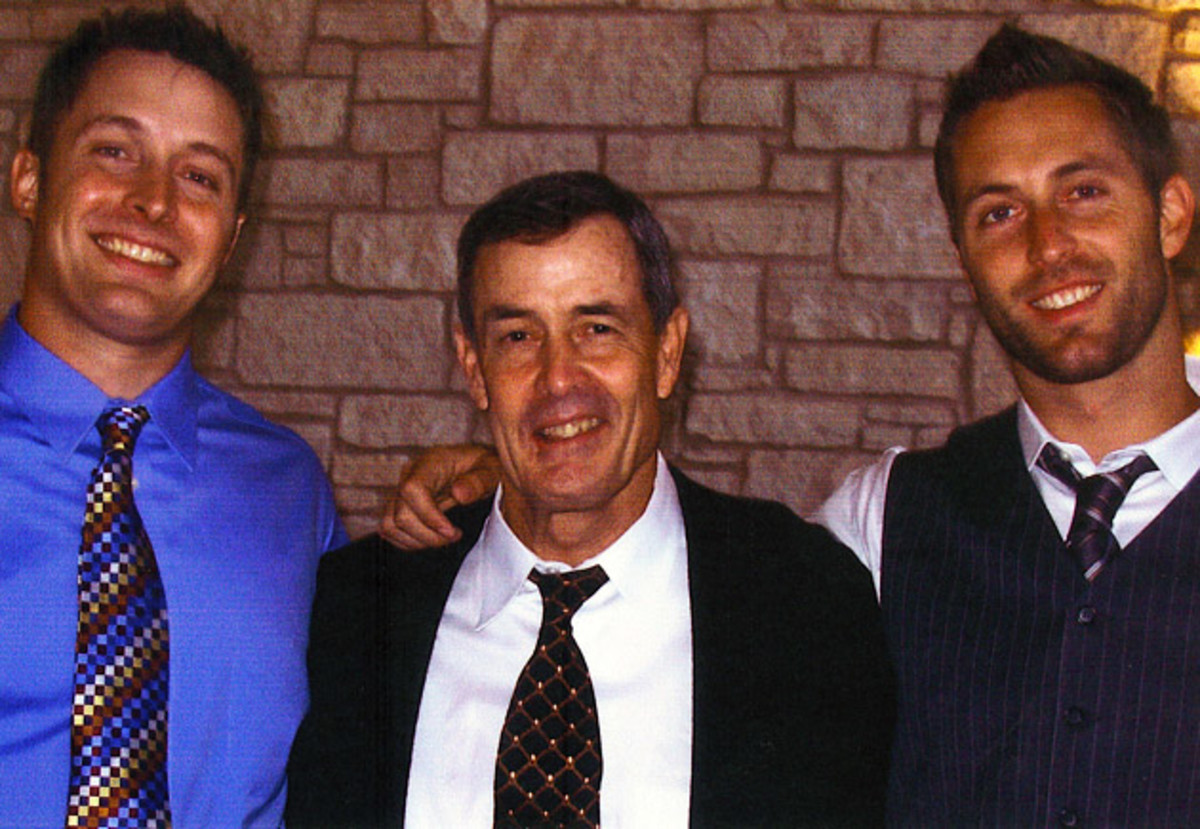

Kingsbury struggles to let go of anything: losses, perceived slights, his failure as an NFL quarterback, the death of his mother, Sally, in 2005. Nineteen years after his father and high school coach, Tim, stuck him on the jayvee squad as sophomore at New Braunfels High, Kliff is still ticked. He admits his tendency to hold on to things can be problematic. It also fuels him.

As the media portrays Kingsbury as a carefree playboy, the handsome 35-year-old -- one of the youngest head coaches in the business -- navigates the environment of big-time collegiate athletics with little experience. He has other problems, too. As Texas Tech (2-1) prepared for Thursday’s trip to No. 24 Oklahoma State (2-1), where the Red Raiders haven’t won since 2001, defensive coordinator Matt Wallerstedt stepped down last week amid a hail of rumors. Kingsbury did not publicly discuss details of Wallerstedt’s resignation, but stressed it was not due to on-field performance. This debacle came months after a quarterback transfer epidemic, in which two players (Baker Mayfield and Michael Brewer) left the program claiming they were misled about playing time. Mayfield is engaged in a public battle with the NCAA to get Texas Tech to grant him a release to play immediately at Oklahoma.

Friends and family say Kingsbury’s public image doesn’t come close to reflecting the person he really is. At his core, he’s one of the toughest, kindest, biggest-hearted sons of Texas, a guy whose competitive drive occasionally gets out of hand. After just five years of coaching -- a profession he never imagined he’d get into -- his alma mater scooped him up and anointed him king of Lubbock. Now he is coming of age while thousands of fans impatiently wait for greatness to take root in west Texas. Though he was a record-setting quarterback under former coach Mike Leach from 1999-2002, Kingsbury is more popular now than he was in his playing days. Everyone wants a piece of him, figuratively and literally: Rabid fans have even gone to the local salon to request his hair clippings.

“This pretty boy stuff, it’s just comical,” says one of his best friends, Thomas Wheat, who has known Kingsbury since 1998. “He’s so much more than that.”

*****

Tim Kingsbury stomps his foot, smacks his hand over his eyes and shakes his head. Relegated to the corner of the Texas Tech family suite, where he has a tendency to get fiery on game days, the elder coach Kingsbury can’t handle this type of defense.

“It’s totally my fault that he’s this way,” Tim says sheepishly days before the Red Raiders fall apart against the Razorbacks in Jones AT&T Stadium. “I used to get so mad if I lost a game I might not even leave the locker room to talk to my wife. Kliff must have been paying attention.”

A Vietnam War veteran and 26-year high school coach, Tim was the worst loser in the family until Kliff came along. When Kliff was a boy, “every loss would absolutely crush him,” Tim says. “I worried about him, a lot.”

As Kliff grew into a Division I quarterback prospect, Tim held him and his older brother, Klint, to a higher standard. Toughness took its footing as rule No. 1: You might be hurt, but if a bone wasn’t broken, you were getting up and walking off the field. “It’s hard to argue with a man who got his jaw shot out, waited a few hours and then walked back to camp,” says Kliff of Tim, who was awarded a Purple Heart. “How do you complain about something hurting?”

Kliff’s earliest memories involve tagging along with Tim to practice, toting a football and running barefoot after the quarterbacks, whom he idolized. “All I wanted to do,” Kliff says, “is be a quarterback forever.” (His hero, fittingly, was Joe Montana.) Tim, whose roots lie in defense, sighs, “He would have been a great free safety.”

• RICKMAN: Where do top teams land in this week's Power Rankings?

Kliff parked himself in front of the TV to watch games, scribbling plays and handing them to his dad. "In hindsight, maybe I should have listened to him," Tim says. Still an information junkie, Kliff studies football at every level: On his weekly radio show earlier this month, he raved about a gutsy two-point conversion call by Southlake Carroll, a Dallas-area high school power. After a few years of coaching, Kliff's appreciation for the game has evolved -- maybe now he sees the logic in Tim's decision to keep him on the New Braunfels jayvee as a sophomore?

“We went 10-0!” Kliff cries. “I should have been the varsity quarterback!”

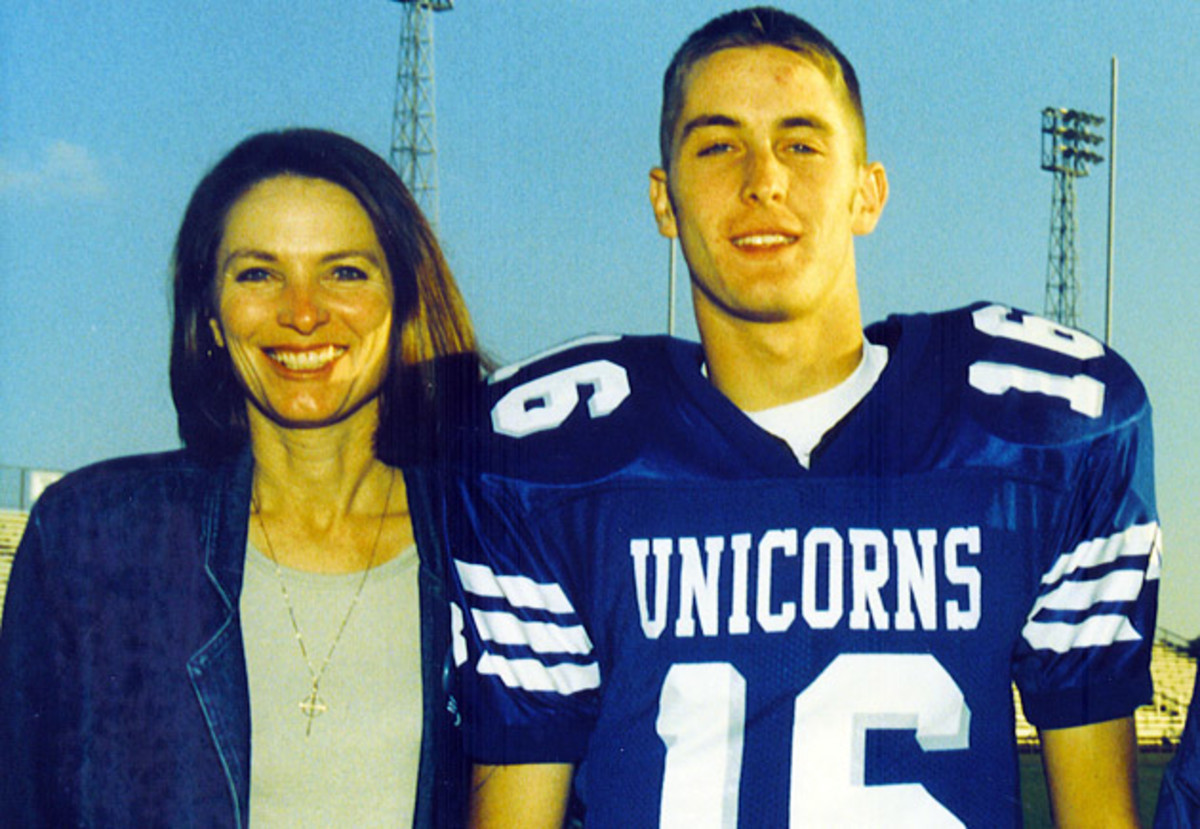

By the time he got the nod to lead the Unicorns (yes, seriously), Kliff played with a swagger that teammates gravitated toward. “He was cocky, and he could talk some smack, but, man, those guys believed in him,” Tim says. Kliff led New Braunfels to six come-from-behind wins as a senior, piling up 3,009 yards with 34 touchdowns as the Unicorns, new to Class 5A, reached the semifinals. The success didn’t temper the feisty dynamic between father and son.

“When Kliff would throw an interception,” Tim says, “I’d get so mad I’d tell our quarterbacks coach to keep him away from me.”

As a head coach, Tim never wanted to falsely tout a player. Kliff even claims that Tim never promoted his son as a prospect to colleges. Tim denies that but admits he preached performance over hype: If Kliff was good enough, Tim said, colleges would find him without the help of a scouting service.

Seventeen years later, Tim isn’t surprised by all Kliff has accomplished.

“He’s old school,” Tim says of his youngest child. “Incredible work ethic. He sacrificed so many Saturday nights in high school. He wasn’t at parties or chasing girls. He was up the field, throwing a ball at the net.”

*****

Klint Kingsbury thinks one thing needs to be cleared up immediately. “Kliff was no ladies’ man,” he says, rolling his eyes. “And he did not know how to dress.”

Still, he says, little brother had plenty going for him.

Kliff, younger by two years, could do anything, and often better than Klint. “We competed in everything,” Klint says. “One time, I got really into cross country, and I was training really hard, getting good and then I raced Kliff and he was right there with me. It sucked. He was good at everything.”

Outgoing, cheerful and there to have a good time, Klint takes after his mother. While losses ate up his little brother, Klint had moved on by the time he left the locker room, displaying a balance and perspective that Kliff lacked. Still, he wasn’t above sibling rivalry. As a senior defensive end for the Unicorns, Klint used every scrimmage against the jayvee “to just try to absolutely kill [Kliff]. It got to the point where they couldn’t have us on the field at the same time.”

Even after they left New Braunfels, Klint appreciated a good hit.

In 1999, during Kliff’s redshirt freshman season, he came off the bench at Texas to take his first significant snaps for the Red Raiders. It did not go well. “He turned that one defensive end from Texas (Aaron Humphrey) into an All-American that night,” says Tim, who watched Kliff get sacked four times. After one particularly brutal hit -- “a great football play”, Klint says -- Klint stood up cheering, not realizing his switch in alliances until his mother hissed, “That. Is. Your. Brother."

Tech’s defensive coordinator pulled Tim aside after the game and said, “I don’t know if Kliff will ever play quarterback again." Then Tim found Kliff bloodied and bruised. “He looked like he had been in a car accident,” Tim recalls.

Gently but firmly, Tim told Kliff to get back out there. What other way would Kliff respond? At home against Oklahoma the next week, he went 9-of-17 for 259 passing yards with three touchdowns as the Red Raiders beat the heavily favored Sooners 38-28 in coach Bob Stoops’ debut season. Kliff started every game from there on out, throwing for more than 12,000 yards and setting 39 school records.

“I think someone would have had to kill him,” Tim says, “to keep him from playing quarterback.”

As Kliff’s professional playing career wound down in 2008 -- a time that included stints with the Patriots, Saints and Jets, as well as stops in NFL Europe and the CFL -- Klint, a technical salesman in Austin, asked Kliff if he had considered coaching. Kliff’s swift response: “Hell no.” Kliff had watched his dad log a lot of long, lonely days and didn’t get the appeal. But then he stumbled into a job as an offensive quality control assistant for Kevin Sumlin at Houston and fell in love with teaching the game.

Promoted to quarterbacks coach and offensive coordinator after two years in Houston, Kliff became a hot name in 2011 when he tutored Heisman Trophy candidate Case Keenum and the Cougars led the country in total offense, passing offense and scoring offense. In ‘12 he followed Sumlin to Texas A&M, and in one season in College Station -- he lived there just 353 days -- redshirt freshman quarterback Johnny Manziel won the Heisman and Kingsbury was named the national offensive coordinator of the year for the second consecutive time.

“He has a beautiful football mind,” Klint says. “He loves the game in a way I could never really understand. One time, when he was still an assistant, I was complaining to him about my job, whining about working 80 hours a week and then I said, ‘I shouldn’t complain to you, you’re working as much as me.’ Do you know what he said? He looked me right in the eye and goes, ‘Yeah, but I love it.’

“I mean, he’s basically a recluse. All he wants to do is study the game. That’s what people don’t get: He just loves football.”

For as many good moments as there have been during Kliff’s rapid ascension to coach of his alma mater, Klint says there’s a small pang with every new achievement. Their mother is not here to see it.

*****

Sally Kingsbury found the good in everyone and every situation. She sent care packages stocked with peanut butter Rice Krispies Treats to Kliff while at Tech, and she phoned his friends to check in on the whole crew. Warm and loving, she put strangers at ease with her infectious and positive attitude.

“I’d talk to her after a game when I had been terrible, thrown four interceptions or something like that and she’d say something like, ‘But you looked good in your uniform! And that one throw was really good!’” Kliff laughs, shaking his head.

Diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2003 at age 51, Sally initially hid her death sentence from the boys to try to protect them. A soft tissue sarcoma started in her leg then spread to her lungs. She underwent chemotherapy and radiation, but her condition didn’t improve. For all that’s made about Tim’s military grit, he says Sally was the tough one. Weeks after having a tumor scooped out of her leg and her left lung removed, she got up each morning to run.

As her health spiraled in the fall of 2005, Kliff flew home from New York -- where he was on his third NFL stop with the Jets -- to say goodbye. A surprise visitor, Kliff held her hand through the night as Sally asked “my guardian angel” if he would be OK, and to please take care of his brother and father.

“Hardest thing I’ve ever done,” he says softly, staring at the floor. Nine years later, it’s still brutal to discuss.

He cried the entire flight back to New York. “I got there and felt like I hadn’t said enough, so I wrote her a letter just trying to say thank you and that I love her,” he says. It reached Sally in time, and when they spoke on the phone, she assured him nothing brought her more joy or pride than her children. Days later, on Dec. 16, 2005, she died. “She fought it the whole way,” Tim says, wiping away tears.

Almost seven years later to the day, Kliff was hired by Texas Tech as its 15th head coach.

Everyone who knew Sally says her defining quality was selflessness, a trait she displayed to the end. As her health deteriorated, tubes and machines became a part of her body. Though she didn’t want others to see her in that state, she understood how much it meant to different members of the New Braunfels community to check in, and allowed visitors. “Her whole life was about giving and helping people,” Kliff says. “That selflessness, it stayed with me.”

It is a quality he works to replicate every day.

Tammi Boozer worked in the Texas Tech sports information office during Kliff’s playing days and became his de facto handler as media requests flooded in his senior year. They grew close, a bond that has lasted almost 13 years. She lost her father in 2008, which brought them even closer. When she married last July, she asked Kliff to give her away. He did more than that: Arriving early to the west Texas church, Kliff realized Boozer needed an extra usher, and started escorting people to their seats.

“That’s what people don’t know,” Boozer says. “He has a huge heart.”

Kliff brushes aside the idea any of this is about him. Yes, he says, holding his hands out, he wishes Sally could be here to see all this. But what really gnaws at him is she never got to meet her grandchildren, Kliff's nephews. (It should be noted 3-year-old Griffin and 2-year-old Lincoln are the only Texas Tech fans who can get away with calling the coach, "Kliffy.") A self-described introvert, Kliff retreated into himself even more after Sally’s passing.

“Her death, boy, it did a number on him,” Wheat says.

It softened him, too. It also softened his relationship with his father. Kliff admits affection didn’t come easily between father and son. Sally's death bridged that gap.

“He was this hard, militant man, but his whole life became about her,” Kliff says.

When Kliff signed a contract extension in late August that will keep him at Tech through 2020, he sent a text to his father with the news: “Thanks for helping me get here. I was very fortunate to have a man like you to look up to my whole life and show me the value of hard work and to never take the easy way out. Love you.”

His father wrote back: “I can’t tell you how much that means to me. I’m so proud of you & so is your mom.”

Kliff says Sally was the one person he showed weakness to, that her presence was the only place where he could completely lower his guard. He keeps a copy of her eulogy in his locker -- her parting words of advice, for the more than 1,500 who packed into her memorial service, were simply, “Be nice to each other.” She was his first phone call on good and bad days, a role that now goes unfilled.

“I keep everything on myself now,” Kingsbury says the day after Tech’s loss to Arkansas. “I’m not going to burden anyone else with that.”

Then, after a pause: “She’s the one person I wish I could have called last night.”

*****

Kliff Kingsbury is mad. This time Kenny Bell doesn’t know why.

The chief of staff for Texas Tech football, Bell pops his head in Kingsbury’s office one morning around 4:30, after he has beaten his boss to work. Kingsbury is blunt, barely saying hello, before a confused Bell wanders off to the weight room.

That morning Bell woke up just before 4 and opted to head to the office when he couldn’t fall back asleep. Understandably, he was alone; Kingsbury, a notoriously early riser, typically arrives at 4:30.

The next day, when Bell again stirred before his alarm rang, he repeated the process. Only this time he pulled into the lot at 4:15 and saw Kingsbury’s car already parked. Weeks later, Bell recounts the story and rolls his eyes. “All of the sudden it dawns on me: He was mad I beat him to the office! And the next day, he had to beat me.”

Kingsbury nods when asked for confirmation.

“Yes, everything is a competition,” he says. “I’m used to pulling up and being the first one here, turning the lights on. If someone’s going to beat me, OK, then I’ll adjust my schedule and get up earlier. Try to keep yourself uncomfortable. I’m big on that.”

It’s this type of drive, and sheer force of will, that has Tech administrators believing they made the right choice to hire Kingsbury, even though Kingsbury acknowledges there’s some trial and error that comes with being a first-time head coach. A prime example is the quarterback transfer situation: Kingsbury hates that it was portrayed as mistreatment, though he admits he probably could have handled it better.

“He’s going to be a great college football coach,” athletic director Kirby Hocutt says. “I see the way young people react to him, and I believe he has an ability to connect with the millennial student athlete in a way no other college football coach can. There are great times ahead for us. Now, how many wins that translates to this year or next year, I don’t know. But I do know we have championship aspirations, and he will not settle for anything less.”

• ELLIS: Who is the early favorite in the 2014 Heisman Trophy race?

Last season Texas Tech shot out to a 7-0 start before stumbling into a five-game losing streak. The Red Raiders regrouped to earn a berth in the Holiday Bowl, but, before the game, Kingsbury was confronted by his staff, who told him they couldn’t help but think he didn’t want to be there. Even worse, the players could sense it, too.

In the past Kingsbury might have harbored a grudge. Instead, “I told them, ‘You know, there’s probably some truth to that,’” he says. He straightened up and Tech handled Arizona State 37-23 despite being a 22-point underdog. It was a reminder to bring consistency to the office.

“I don’t know if I know myself completely, but I know that I’m always being myself,” Kingsbury said. “Great coaches, they don’t put on any sort of façade. I should probably handle losing better sometimes, but at the same time, that’s what gets me up in the morning. It’s not like I’m excited to wake up at 4 a.m. -- but then I think of something that makes me angry, something I want to fix, and I’m up.”

When Tech went on a coaching search after firing Leach in late 2009, Kingsbury, just two years into the profession, had a hunch he’d return to Lubbock sooner than anyone else could anticipate.

“I’m working in quality control, and we’re standing in the offensive hallway at UH and sort of in passing he says, ‘Don’t worry, in three years it’ll be my job anyway,’ and gives me the little double guns up and smile as he’s walking back into his office,” Bell recalls. “At the time, I thought it was completely ridiculous. I mean, it's not supposed to be that easy to predict!”

It is, Kingsbury says, the perfect anecdote to match one of his favorite lines from his favorite book, The Alchemist: “And, when you want something, all the universeconspires in helping you to achieve it.”

Kingbury has heard all the digs about Lubbock -- too small, too isolated, too many tumbleweeds -- but believes his staff’s passion and work ethic will shine through with recruits. The quarterback transfer fiasco aside, kids do want to play for him: The Red Raiders already have verbal commitments from three four-star prospects for the class of 2015, including Elite 11 quarterback Jarrett Stidham, who spurned offers from Alabama, Auburn and Oregon, among others.

The former quarterback is the most popular person on campus, though, even more in demand than current star Davis Webb. Kingsbury certainly creates more hype: Shortly after his hiring, T-shirts with the hashtag “Our coach is hotter than your coach” popped up in the stadium, a statement both flattering and uncomfortable for Kingsbury. He requested a halt in production, insisting focus be turned to the team.

“He’s way more simple than people realize,” Bell says. “His mind is always racing about this program, but he’s about relationships. He’s not into stuff; he wants to invest in people.”

It’s a lesson he learned from his mother. Kingsbury responds to every piece of mail he receives -- almost 50 letters a week -- with a handwritten note. The day after the Arkansas loss, he opens a pink envelope from a former classmate at New Braunfels. The letter congratulates Kingsbury on his success, and asks him to please stay grounded, as his parents would prefer. Then, a P.S.: “This envelope reminds me of your mom. What an awesome lady she was.”

“She never leaves my mind,” Kingsbury says. “I think a lot about how she loved coming up here, how the people of west Texas were her favorite. She’d be getting a kick out of all this.”

Kliff was always the trash talker in the family but says, if she were still here, Sally would rib him endlessly for all the coverage of his image.

And probably she’d hope everyone could see beyond that.