How Lefty Driesell started Midnight Madness with a midnight run in 1971

Did you know Midnight Madness started with a midnight run?

It’s true. Happened on Oct. 15, 1971. Byrd Stadium, University of Maryland, College Park. At three minutes after midnight (to make sure they were not starting too early in violation of NCAA rules), the members of the school’s basketball team began a mandatory one-mile run on the track. The stadium lights were off, so the only illumination came from the headlights of a few cars parked at one end of the stadium. The workout was not publicized, but some 800 students had gathered to watch. Word of mouth had spread, apparently.

The run was the brainchild of Maryland’s coach, Charles “Lefty” Driesell. He had been hired two years before from Davidson, an off-the-beaten-path program which Driesell had taken to two regional finals in the NCAA tournament. Driesell was a savvy promoter, but he was not trying to put on a show that night. He was trying to make a point. “It was a motivational thing more than anything else,” he says. “I knew we were gonna have a pretty good team. I told the players, ‘Look, we’re gonna start the first practice this year of anybody in the country, and we’re gonna be playing in the last game for the national championship.”

Best Teams Not To Win A Title: How '74 Maryland started it all

Indeed, the Terrapins' 1971-72 season was beginning amidst unprecedented expectations. To that point, Maryland had played in just one NCAA tournament – and that was in 1958. Yet, the previous season, the Terps’ freshman team had gone undefeated thanks to the arrival of two premier recruits: Tom McMillen, a 6-foot-11 center from Pennsylvania who once graced the cover of Sports Illustrated under the billing “THE BEST HIGH SCHOOL PLAYER IN AMERICA,” and Len Elmore, a 6-9 forward who had starred for New York City’s Power Memorial High School, where Lew Alcindor, later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, played. Freshmen were ineligible to suit up for the varsity in those days, so McMillen and Elmore’s fellow students were eager to see them as sophomores in action, even if that action was running in the dark.

Driesell stood next to his assistants at the finish line, holding a stopwatch. If the players did not finish their mile within six minutes, they would have to run it again at a later date. As they rounded the turn opposite the headlights, a few upperclassmen cut across the grass. “The older guys were a little more devious, a little braver than I was,” Elmore says. “We didn’t snitch back in those days.”

When the run ended, everyone left. That was it. The only media coverage came in the form a brief item the Associated Press sent out on its wire the following morning. It read: “Under big college basketball rules, practice for the coming season’s games became legal as of yesterday. So at three minutes past 12 in the morning, Maryland coach Charles Driesell put 21 players through a preliminary workout: a one-and-a-half mile run.” (The AP had gotten the distance incorrect.)

So that’s how it all began. There was no madness that first time out. There was only midnight. “I’ve done a lot of crazy things to get attention, but that wasn’t one of them,” Driesell says. “I was just trying to get an early jump on practice. I had no idea what it was going to lead to.”

*****

Driesell is 82 now, retired and living in Virginia Beach, Va. Midnight Madness has traveled many miles since that first outing, but its humble origins have been long forgotten. Former Georgia Tech coach Bobby Cremins competed for five years against Driesell in the ACC in the 1980s, but when I asked him recently if he knew that Driesell was the father of Midnight Madness, he replied that he had no idea. “But it doesn’t surprise me,” Cremins added. “The first time I got to know him, I said, ‘Boy, I could see that guy being a heck of a Bible salesman.’ Then someone told me that’s what he used to do in the summertime, sell Bibles door to door. Lefty was just was relentless. He was always looking for an edge.”

He also knew a good thing when he saw it. The next year, Maryland’s mile run drew an even bigger crowd. Then, in the fall of 1973, a hotshot freshman from Philadelphia named Mo Howard suggested that, instead of staging a mile run, the Terps should hold an open scrimmage inside Cole Field House. By that time, Driesell had also added John Lucas, a 6-3 guard from Durham, N.C., who would go on to earn All-America honors in both basketball and tennis. After warning Howard that the players would still have to make their mile time at some point, Driesell agreed. “I was just a rowdy, precocious freshman,” Howard says. “I was pretty jacked up about our team, and I wanted to let everybody see how good we could be.”

When the team took the floor in Cole Field House for an intrasquad scrimmage at midnight on Oct. 15, 1973, more than 8,000 fans were in the seats. “I was highly impressed by that,” Elmore says. “There was a certain sense of pride that our folks recognized us in that manner. It was a strong motivation to try to be good that year.”

Howard was understandably amped to show the crowd what he could do. This was, after all, his idea. Unlike many coaches, Driesell encouraged his players to dunk during warm-ups, so Howard gave it his acrobatic best. He landed awkwardly and fractured his ankle. Howard sat out the game and spent the next three weeks in a cast.

*****

Driesell was so creative in finding ways to draw attention to his program that Elmore took to calling him “P.T. Barnum.” McMillen, however, saw a competitive value in starting practice at such a late hour. Maryland was scheduled to open its season with a road game at UCLA. McMillen, a future Rhodes Scholar and U.S. Congressman, believed Driesell was trying to get their bodies acclimated to the Pacific time zone. It almost worked, as the Terps took John Wooden’s Bruins to the wire before succumbing, 65-64. “Coach was a master edgeman,” McMillen says. “There was always a method to his madness.”

From then on, Driesell held an open practice every season at midnight on Oct. 15. Several years passed before other schools caught on. Cremins never wanted to hold one at Georgia Tech because he was worried not enough fans would show up. Kentucky held its first Midnight Madness in 1982. Three years later, Kansas coach Larry Brown decided to conduct one as well.

Five non-conference tournaments to watch in college hoops this year

Eventually, enough schools were doing it that ESPN decided to tap into the wellspring. The network aired its first Midnight Madness special on Oct. 15, 1993. The next year, an undergraduate at Cincinnati won full tuition by sinking a halfcourt shot live on national television. When the shot went in, Dick Vitale jumped into his arms. One of the last coaches to acquiesce was Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski, who agreed to let ESPN cover his team’s midnight scrimmage in 1997. Afterward, Krzyzewski swore he would never do it again, but of course he has.

Naturally, it was only a matter of time before the NCAA felt compelled to step in and set some parameters. In 1997, the rules were changed to allow schools to begin practice at midnight on the Saturday closest to Oct. 15th, so all those sleep-deprived students wouldn’t have to stay up late on a school night. Eight years later, the rule was amended to allow teams to practice at 7 p.m., so they wouldn’t have to stay up late at all. Driesell, for one, did not care for those adjustments. “I think these new rules are ridiculous,” he says. “People say, ‘Well, the alumni won’t come at midnight,’ but it’s not for the alumni. It’s for the students. Midnight is when they’re out partying and having a good time.”

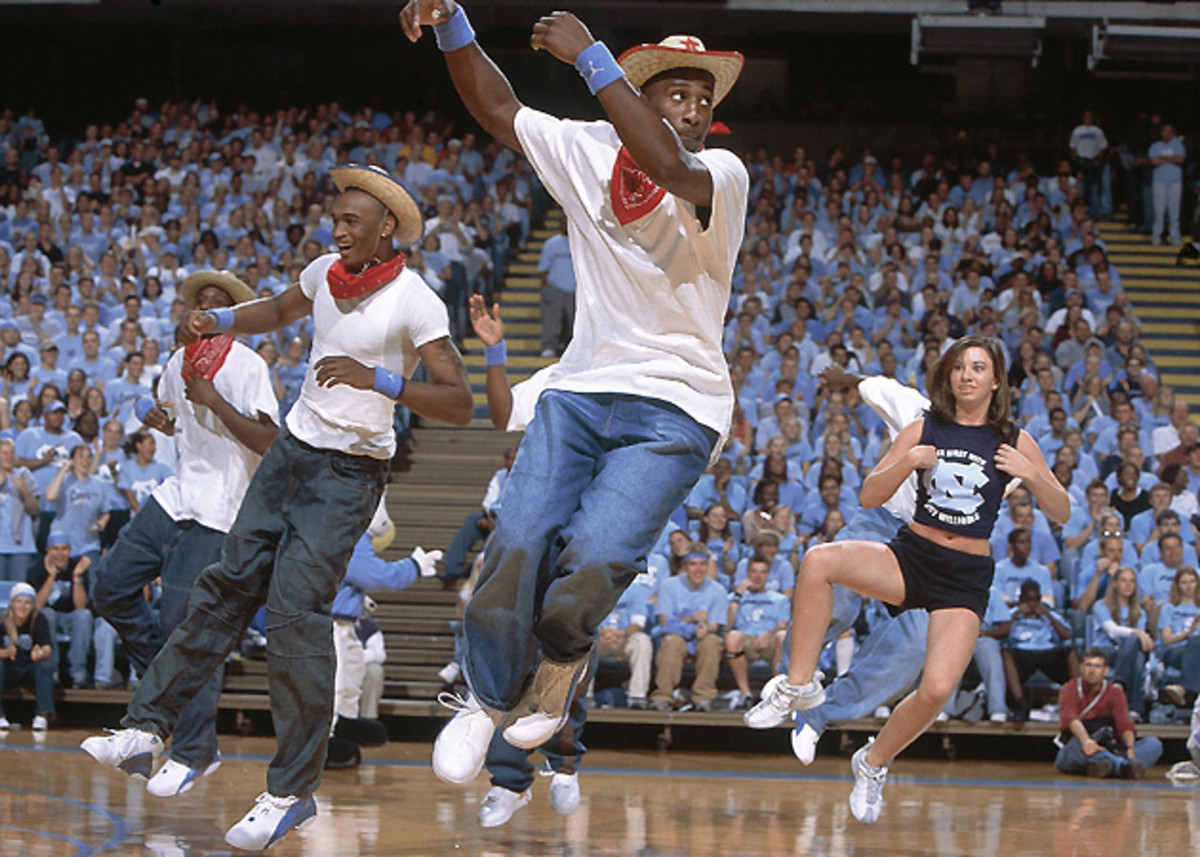

Still, it has been wonderful to watch Driesell’s little stunt take wing. Thanks to him, every coach is P.T. Barnum these days. Tom Izzo has ridden onto Michigan State’s court on a Harley Davidson. Florida’s Billy Donovan climbed out of a coffin. Former Illinois coach Bruce Weber once had a basketball court wheeled into the school’s stadium and staged a scrimmage during halftime of an Illinois-Minnesota football game. North Carolina’s Roy Williams allows his players to perform skits. Kentucky’s John Calipari gave a full-throated presidential address, TelePrompter and all. Last week, Kansas’ Bill Self donned a garish suit and bow tie to copy the outfit former Jayhawk Andrew Wiggins wore at last June’s NBA draft. Besides generating excitement amongst fans, these parties help sell programs to recruits. In 2007, Scout.com counted 160 top high school players who were attending a Midnight Madness somewhere.

Beginning last year, teams were permitted to begin holding full practices six weeks before their first official game. That usually means starting in the first week of October, but most schools are staging their celebrations around the 15th of the month, just like always. On Friday night, ESPNU will air coverage from Kentucky, UConn, Arizona, San Diego State and Gonzaga. Dozens of other schools will also hold Midnight Madness celebrations to herald the start of practice, even though they aren’t taking place at the start of practice. Or at midnight, for that matter.

*****

For all of Driesell’s successes, his career is often remembered for the tantalizing ways in which he fell short. He coached in two more Elite Eight games at Maryland, but he never reached the Final Four. The McMillen-Elmore-Lucas group won its share of games, but it is most remembered for a historic loss in overtime to N.C. State in the 1974 ACC tournament final. That game is widely credited for hastening the tournament’s expansion to include at-large teams, instead of just conference champions, the following year.

And of course, Driesell’s tenure at Maryland ended tragically in the wake of the cocaine-induced death of Len Bias two days after the 1986 NBA draft. It was ludicrous to suggest Driesell was responsible, but the school needed someone to blame, and he was the one who got shoved out. He coached 15 more years at James Madison and Georgia State before retiring in 2003, just 14 wins shy of 800 for his career.

His players remember him fondly. “We were like his children,” Howard says. “At that time, there weren’t too many African-Americans on ACC teams. Coach protected us. You knew he was going to give you the best stuff he could.” That included getting an early jump on the competition. The track inside Byrd Stadium led to a path that no one could foresee, least of all Driesell. “I think it’s good because it gets people thinking about basketball when there’s a lot of football going on,” he says now. “I’m proud of it. I’m glad people are still doing it.”

Not just basketball people, either. Sometimes, when Driesell is riding around in his car through Virginia Beach, he’ll spot a sign at a local business promoting a “Midnight Madness” sale. What does Lefty think when he sees that?

He chuckles and replies, “I should have gotten a patent on it.”

Always looking for an edge.