SI 60 Q&A: Curry Kirkpatrick on the artistry of Pete Maravich

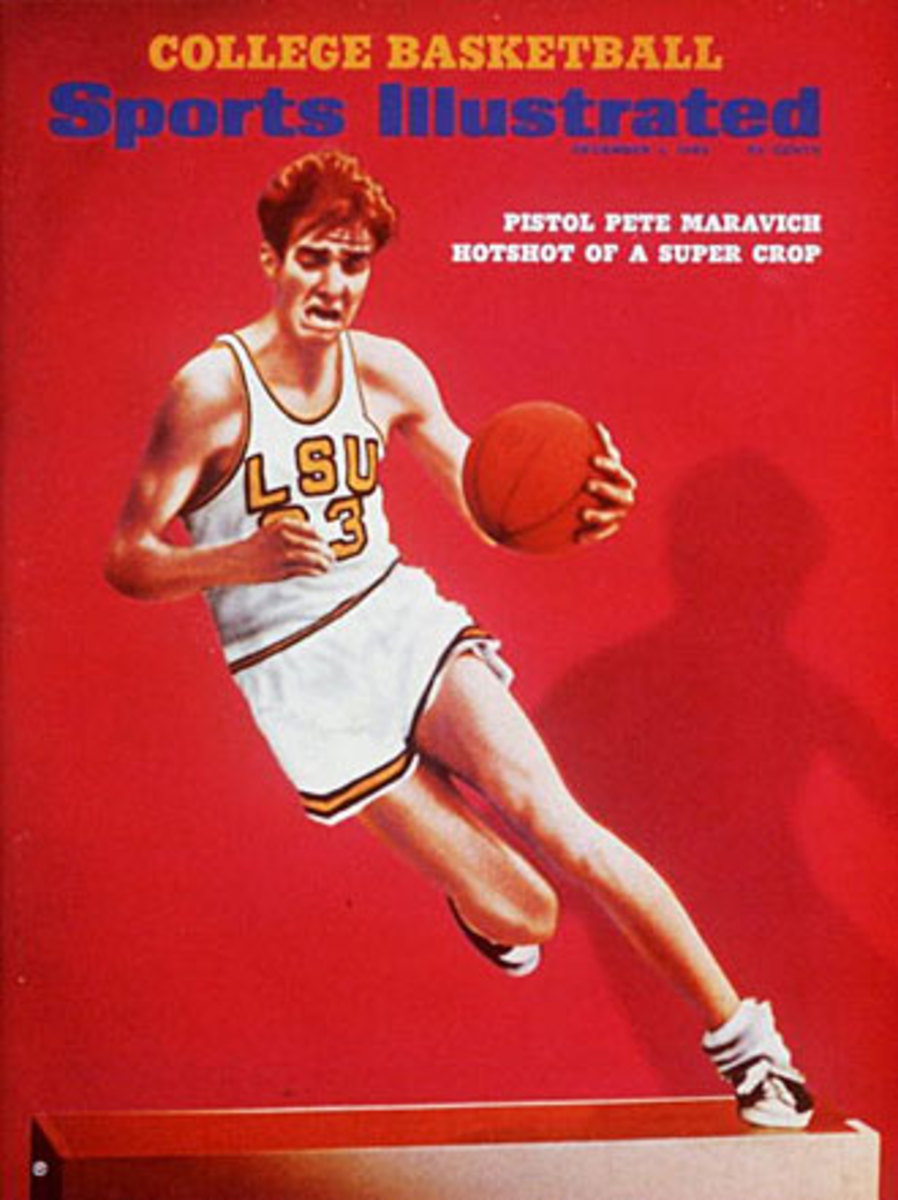

For the 1969-70 college basketball preview issue, Sports Illustrated commissioned artist Howard Kanovitz to create sculptures of some of the nation’s best players. Kanovitz started by photographing seven of them, then laminated canvas images of those photos onto wood, cut them out and painted them in acrylic. The results were works of art that Kanovitz hoped were “so real they transcend reality.”

The same could often be said of the young man whose sculpture wound up on the cover of that issue, Pete Maravich. The soon-to-be LSU senior was already a scoring phenomenon and he had already been on the cover of SI as a sophomore, when a writer barely older than he was came to Baton Rouge, La., to write about his geaux-geaux life as the leader of the Tigers and son of the LSU coach. Curry Kirkpatrick’s resulting story, “The Co-Ed Boppers’ Top Cat,” has since been anthologized many times by SI, including being reprinted in full during the magazine’s 40th anniversary celebration in 1994. There might be only one person who doesn’t like it: the author himself.

Kirkpatrick, though, still has a warm place for the story’s subject. In almost three decades at the magazine, he wrote about nearly every college basketball star in America, from Lew Alcindor and Bill Walton to Michael Jordan and Patrick Ewing to Christian Laettner and Chris Webber. Yet it is Maravich who is immortalized at his home in Hilton Head, S.C., with the large black-and-white canvas photo from Kanovitz’s long ago project.

Kirkpatrick wrote often about Maravich over his first 20 years at SI, including for the story chosen as part of the SI 60 – “No One Can Cap The Pistol” – and to write an item in Scorecard, the magazine's front-of-the-book section, when Maravich died suddenly in 1988. I spoke to Kirkpatrick about that 1978 story and his relationship with one of basketball’s most forgotten stars.

SI: You told me you don’t like that first cover story of Maravich very much. Why not?

KIRKPATRICK: Having re-read it now, as a writer I just cringe. I don’t remember my feeling at the time, but looking back on it I don’t think it was that good, probably because I was only a couple years out of college at the time. I wrote a lot about the way he played in detail, almost boring detail. The story I’m most proud of on him was the one in the twilight of his career. Those stories are so different. That later story is so much better.

SI: Why do you say that?

KIRKPATRICK: You can tell there’s a vast difference in my writing by looking at the two Maravich stories. By 1978 I had created a style. There were words I wouldn’t have used before. I had learned how to report.

In 10 years I had developed a style, I didn’t know what it was but I pretended that I was Frank Deford most of the time and just did what he did. Deford was more than a mentor for me, he was an idol. I remember being at a North Carolina-Duke basketball game when I was in school at UNC – not even covering the game, just in the stands -- and seeing Frank courtside on press row, just walking around talking to people, and thinking, This is the coolest guy I’ve ever seen. I didn’t even know him but I’d admired him for years. I said, “This is what I want to do: I want to be him.” When I got to SI, he befriended me and he’d talk about stories to me and give me advice. I was his reporter so I reported on a bunch of stuff for him.

SI: Why else did you like the 1978 story better?

KIRKPATRICK: It’s really critical. I’m in there killing people. And I killed Pete. I really liked him and his wife and considered him a friend. But he had become a nut job and it was sad to see, but I wrote it. Maravich was one of the most misunderstood and controversial athletes ever. There’s never been a guy like him. There’s a quote in there from Rick Kelly, a teammate who was kind of a hippie. Kelly called him, “An American phenomenon, a step-child of the human imagination.”

I got some conflicting views on him, went into his personal life and talked about how he’d become bizarre on politics and food and alien life. He really believed that aliens were going to come down and grab people. He painted a target on the roof of his house, meaning, “Take me.”

I don't even remember talking at his house for that story. He might have been embarrassed about all the locks he had around the house to protect himself.

He was very naïve as a person and had a very unhappy home life. His mom was very ill and ended up committing suicide. His dad had been his coach at LSU, and after Pete went to the pros I think his dad was very embittered that he didn’t get a job coaching in the NBA. I think he had this dream that he would go to the NBA with Pete and be his coach forever. And that didn’t happen. He got fired at LSU, which created a real conflict with Pete at the school. There was talk of building a statue of him and Pete wouldn’t cooperate.

• SI 60: Read every story and interview in the collection

SI: How did you get the assignment to write about Maravich the first time?

KIRKPATRICK: He was just becoming a huge name. Even after being at the magazine for a couple years I hadn’t written that many stories. I’d been there mostly as a reporter but I had started to be a college basketball guy, although I wasn’t writing the main stories, Joe Jares was doing that. I’d written about Norfolk State, a black school. I’d written about a college tournament in Nova Scotia. The one I did a few weeks before Maravich was St. Bonaventure being the surprise of the season.

It’s tough writing about a teenager, and this was the first cover story I did. Two weeks later I got another cover story, which was kind of amazing, about Bill Bradley coming back to the Knicks from being at Oxford. I was just rolling.

No One Can Cap The Pistol: Twilight for Pete Maravich, hoops' most talented loser

SI: Not bad considering you hadn't been at the magazine long. How did you get to Sports Illustrated?

KIRKPATRICK: When I was in college at North Carolina, SI had a stringer named Bob Quincy, who was also the SID. The magazine used a lot of SIDs as stringers at the time, but figured they wouldn’t get anything that wasn’t pro-that-school, so Quincy asked me if I would do it. In December of my senior year, 1964-65, SI called me up and said, “We’d like to talk to you about a job.” I was thrilled, obviously. At that point the Vietnam War was going on and they had just lost a reporter to the Army, I believe it was Herm Weiskopf. At that point SI was a really small staff and they needed a body in there, somebody to do research and make phone calls; not to write. It was really a fact-checking job, but it was SI, so it’s like the circus, your job at the circus is cleaning out the elephant tent but at least you’re in show business.

I'd been dealing with Honor Fitzpatrick, who was the chief of reporters. She was almost as terrifying as Andre Laguerre, the legendary managing editor. I said, “Yeah I graduate in the spring and I’d love to.” They said, “We don’t need you in the spring we need you now.” “What do you mean now?” They said, “Next week.” I wasn’t even out of college. I said, “I gotta think about it." They said, "Take a week and let us know.”

I thought about it and I said, I can’t do this, I gotta graduate. I’m not gonna just leave. So I told them that and I said, “I get out in May, will the job be there then?” They said, “No, we can’t guarantee there will be an opening.” I thought, well there goes my life.

So I finished up school went back home to Niagara Falls, N.Y., and I had a job that summer working at the Buffalo News, this would have been 1965. That September, SI called again and said, "We'd like you to come work for us if you can," and of course I jumped at the chance. That fall I started at the magazine. After six months I had to go in the Army myself as a reserve, but I hadn't told them that.

SI: Maravich debuted on LSU’s varsity in 1967, two years after you started at SI. He played almost his entire career before the invention of ESPN and so most of his greatness went unseen. How much of him had you seen when you wrote that first story?

KIRKPATRICK: That’s a really good point. Nobody had really seen this guy much on TV. The SEC was a minor basketball league. It was Kentucky and that was it. Florida hadn’t risen, LSU hadn’t risen. America kind of zoned in on his floppy socks. They were these old gray team socks that were actually from N.C. State, where his dad had coached, while the rest of the team wore these bright team socks. He would wash and dry them himself in his dorm room.

I had seen him in person here or there, but the great tragedy of this is that there’s hardly any video of him in college. There’s really no footage of him hanging 69 on Alabama and throwing halfcourt passes.

One year, in a game in Hawaii in the semifinals of this tournament, LSU played St. John’s, which had practically an all-black team. And they’d never seen him either, even though he’d been playing in college for two years. St. John’s was a really good team and LSU was a bad team. In the second half he scored 41 points -- in a half! They win going away and as the clock’s running out he’s about at midcourt and just for the heck of it – today he’d get punched out for this – but he threw in a hook shot. The St. John’s team just comes rushing off the bench and goes up and embraces him like, Dude you’re unbelievable! To give you an idea of how up and down that LSU team was, the next night in the final they played Yale and they get beat -- by Yale! -- in the final of the Rainbow Classic.

SI: Why did you want to write about him again 10 years later?

KIRKPATRICK: The magazine took me off colleges and put me on the NBA for about three years, starting the year of the merger, 1976-77. I didn’t like covering it as much as colleges so they eventually let me go back to colleges.

Anyway, I thought he really was an iconic figure not just in basketball but in all of sport. He was a one-man band. He was the star. To me he was the most captivating athlete of all because he was so different. People say, “Who would you pay to watch?” This was the guy.

There’s a great story I used in that 1978 bonus piece, and it's one of my favorite anecdotes about any athlete I ever got. A guy named Marv Roberts was an ABA veteran and in his later years came to the Lakers. He was on the bench and he’s watching this guy for the first time, and Pistol is rocking the place. At this point Roberts can’t contain himself and he leaps off the bench and says, “I sees you Pete, I sees you now!”

He was the all-time gunner who ever lived. Pat Riley said he was overrated and Bill Fitch said his team would win the whole thing if they had him. Those were the degrees of difference people felt about him.

55: Remembering the night Michael Jordan announced his return to dominance

That was the end for him. After the story ran in December he got hurt again and that season was gone and then he retired one year later. If he’d had a veteran team he would have been a great player early in his career. He needed someone to say, “Look you’re not going to get away with the things you did in college, your dad’s not your coach anymore, you’re going to be a team player.” I think he’d have gone along with that. Because he really did want to win.

SI: You wrote about him one more time, after he died in 1988. What was your reaction when you heard the news?

KIRKPATRICK: I was at home at my daughter's sixth birthday party and I had to sit down. I cried. It was such a shock. He wasn’t in the public eye anymore. At that point he was just an older athlete. He wasn’t doing commercials, he wasn’t an executive, he wasn’t a scout, he wasn’t a coach. He kind of had taken over his private life. He had become very religious and had thrown away all those weird opinions about food and politics and Martians. He was at peace. When he had his heart seizure on the court he was shooting around with some friends. He was there to appear on a Christian radio show. It was a real shock that Pete Maravich had died of heart seizure at 40.

I was 45. It was probably the first athlete that I knew really well who died. I sat down and had a cry and just had all these memories. Then the magazine called and said, Could you write a little thing on him? I got a note from George Will saying, “Mr. Kirkpatrick, fabulous piece on Pete Maravich,” which was amazing coming from George Will.

After he died I stayed really good friends with his wife, Jackie, and we talk on the phone a couple times a year. The last time was when some TV person called and wanted to know if I could get video of him. She had some and said, “People are trying to get it and I’m not going to give it away, and I’m not going to sell it.” She finally donated it to the school archives. When his two sons were playing basketball in college, I did a story on them for ESPN. So I kept up with the family for quite awhile.

SI: Why do you think he continues to be so overlooked?

KIRKPATRICK: It’s a shame. If we had video of him playing then he would be remembered more. He was the most entertaining player, and it’s hard to hear that after these days of LeBron and Jordan, especially. He was Cousy after Cousy and Magic before Magic. He was above all of them as far as entertainment goes. If we had video of him as a college player he’d have a secure rank in the top five, top 10 players of all time.