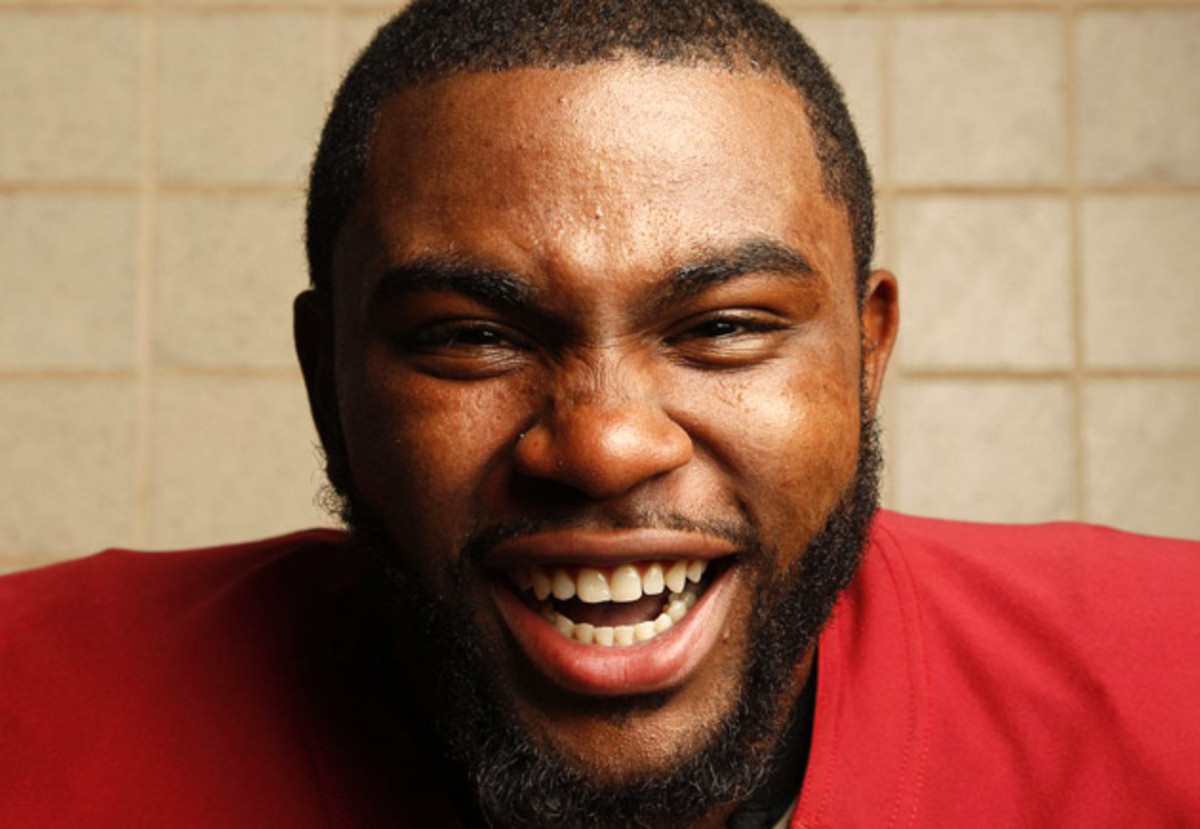

Breaking the mold: How Oklahoma star Eric Striker came into his own

NORMAN, Okla. -- Eric Striker Jr. is at a loss for words. He reclines in his chair with a towel draped around his neck, and, at least for now, he’s silent. For one of college football’s most disruptive defenders, who talks fast and moves faster, moments like this are rare.

It’s a muggy Sunday afternoon, and the 6-foot, 221-pound junior linebacker has just finished reviewing tape of Oklahoma’s 48-16 win over Louisiana Tech. While most other players are resting, Striker is reflecting: on the Sooners’ victory, on expectations for the rest of the season, on his musical tastes, on what helped him become the man he is. He is trying to remember the lyrics to Jay Z’s “Lost One,” and his eyes flit back and forth, willing the words to appear.

Striker exhales. Then it hits him. A smile cracks his face as he recites the desired verse from memory:

Fame is the worst drug known to man

It’s stronger than, heroin

When you could look in the mirror like, There I am

And still not see, what you’ve become

I know I’m guilty of it too, but not like them

“That was beautiful,” Striker says of the lyrics. “You can look in the mirror, and it brings you back to who you are. I’ve done it.”

Striker, 21, has done more than that. He has made 34 tackles with 5.5 sacks this fall, tying Brian Bosworth for the most career sacks (12) by a Sooners linebacker. No. 15 Oklahoma (6-2) enters Saturday’s game against No. 12 Baylor (7-1) fighting to keep its Big 12 title dreams alive, and Striker has emerged as the centerpiece of the defense. He plays with the controlled chaos of the Tasmanian Devil -- a comparison also used by coaches and teammates -- and has drawn attention from NFL scouts. Though some question his size, he has been projected as a late first- to second-round pick, if he were to declare. “He reminds me a lot of Von Miller at Texas A&M,” ESPN analyst Todd McShay said during Oklahoma’s 31-26 win over Texas on Oct. 11. “Eric Striker is the type of guy that you have to account for in the rush, but also he’s so athletic, he can drop off in coverage.”

For now, though, Striker remains still. He pauses, rolling each of his fingers off his thumbs. During a season in which he is catapulting onto the national radar, he is taking this time to look back. “People let the fame take ’em to another place,” he says. “But you gotta remember who you are and what you came from.”

*****

Striker’s earliest football memories begin, fittingly, with the Oklahoma drill. He was six and a member of the Winston Park Warriors, a Pop Warner team in Tampa. He and a teammate strapped on pads and lined up a few yards apart. When a coach blew the whistle the boys charged, each trying to drive the other into the ground.

The drill, conceived by former Sooners coach Bud Wilkinson, is intended to help players get used to the contact they’ll experience in games. But Eric and his teammate had no idea how to hit. “We were just going helmet to helmet,” Striker says, laughing. “Like straight up. Damn near about to break our necks.”

Mischievous and energetic, Eric was the type of kid who did anything he was told not to, who broke what he wasn’t supposed to touch. After repeatedly being instructed to avoid teasing his grandmother’s pitbull, he provoked the dog into biting him and trying to drag him in a hole in the backyard. But football helped Eric concentrate. He was a diminutive nose tackle and receiver, first for Winston Park and later for the Progress Village Panthers, and he showed flashes of greatness at an early age. “I remember his Pee Wee coach telling me he saw something in EJ and knew he would go all the way,” says Eric’s mother, Lia Skelton. “In my mind it’s youth recreation football, but there was definitely something his coach saw in him.”

• RICKMAN: Where does Oklahoma land in the latest Power Rankings?

In middle school his energy proved unremitting. Before games he would mow his family’s lawn, front and back, as a way to settle his nerves. His motor was always going, which was an asset on the field. “Even though he’s not [very] big, he always got after the quarterback,” says his father, Eric Sr. “He had some kind of swivel back then [and] he always got through the line.”

As a freshman at Armwood (Fla.) High in 2008, Striker attempted to make it as a receiver, but head coach Sean Callahan, defensive coordinator Matt Thompson and linebackers coach Corey Peterson urged him to move to defense. For one thing, he lacked prototypical height. For another, Thompson was planning to switch from a 4-3 to a 3-4 scheme, and Striker’s blend of speed and tenacity was ideal for a blitzing outside linebacker.

Thompson explained how Striker would fit in the new system, and Striker agreed to change positions. The results were astounding: Striker started as a sophomore and went on to amass 350 career tackles, 62 quarterback hurries and 42 sacks, the latter an Armwood record. As a senior in 2011 he was the anchor of a team that went 15-0 and won the Class 6A state championship. (The title was later vacated after it was revealed some players used false documents to transfer to Armwood.)

During the 2011 championship, against Miami Central, Striker’s speed so flustered the opposing quarterback that he threw two first-quarter interceptions that were returned for touchdowns, setting the tone for a 40-31 victory. But Striker’s impact went beyond. “I think in all my years there’s maybe two or three guys I missed,” says Callahan, who has been at Armwood since 1990. “And he’s one of ’em. We miss him. Not as a football player. Just his presence.”

*****

Lia Skelton was born in 1970. The oldest of four children between Mercedes and Ralph Skelton, she spent her early years in Perth Amboy, N.J., before moving with her family to Tampa at age 12. There, after watching neighborhood boys who she thought were good people get sent to jail, she decided to pursue a career in law. “I would see the revolving door,” she says, “and I would think, it’s not fair, it’s not right. People aren’t given a chance.”

That legal career would take longer to realize than she thought. When Lia was a 17-year-old senior she had her first child, Antino Mention. Lia went into labor on a Monday in April 1988, and she returned to Henry B. Plant High a week later. Her parents helped care for Tino as she completed her final semester and graduated.

Lia then had two more children: Christopher Striker, who was born in 1991, and Eric Striker Jr., in ’93. She raised her sons mostly on her own, a challenge for a mother so protective that she wouldn’t let the boys ride the school bus, or go swimming without her supervision. “There were times when I didn’t have a car,” she says. “I was pretty much by myself. You just keep chugging through it, you know? There’s always a way.”

The details may sound familiar: a single mother fighting to make ends meet until her football-playing son can reach the NFL and provide for her. This is not that kind of story. Eric Jr. visited with his father every other weekend and remains close with that side of the family. And his mother’s dogged pursuit of education set a powerful example. “My dreams aren’t tied in the dreams of my children,” Skelton says.

She earned an undergraduate degree in criminology in 1998 after transferring from Hillsborough Community College to South Florida. She picked up two jobs, as a contact center supervisor for Progressive Insurance and as a makeup artist for MAC cosmetics. After moving a few times, she bought a house in Brandon, Fla., in 2004, and has lived there ever since. All while raising Tino, Christopher and Eric. “We drove her crazy,” Eric says. “To see her go through that stress, I could go through anything.”

Once a troublemaker, Eric began to break the mold in a different way. He spurned any form of social media. He volunteered in Armwood’s administrative office and formed a close bond with assistant principal of curriculum Dr. Nicole Gallucci. He developed a reputation as an old soul, and in high school spent many Friday nights with his mom, watching Real Time with Bill Maher instead of going out with friends. “He never partied,” Skelton says. “He never went out or broke curfew or stayed out late. He just never did the stuff that teenage kids do.”

Even his musical tastes differed from those of his peers. His first love was Motown soul, and he became obsessed with the Temptations starting in third grade. From the time Eric was nine to age 15, Skelton would come home to find him dressed in slacks and shiny black shoes, shimmying across the floor pretending to be David Ruffin. “My mom bought him a DVD of the Temptations’ original performances,” Skelton says. “He would watch that every single day, study every dance move, every song. When I’d get home from work, that’s all you’d hear.”

Playlist from an athlete: Oklahoma linebacker Eric Striker

As Eric prepared to leave for college, Skelton took her next educational step. The January after Eric began classes at Oklahoma, Lia enrolled at Thomas M. Cooley Law School, where she’s now midway through her second year. Though she has yet to declare a concentration, she jokes about becoming Eric’s agent -- and making it big at the same time he does.

“I think there are forces that may be more powerful than us that put things in motion,” Skelton says. “I feel like anything I’ve ever wanted to do, I can do. I think that’s just the way life is. Or it’s been that way for me. And I don’t know why.”

*****

[pagebreak]

Striker recruited Oklahoma, not the other way around. Even though he was a star at a perennial power in the talent hotbed of Tampa, he drew limited interest from top in-state programs such as Florida and Florida State. He visited both, but his potential went unrecognized. That was clear when he accompanied Armwood back Matt Jones and lineman Cody Waldrop to Gainesville for junior day in 2011.

“A lot of players went in [Florida] coach [Will] Muschamp’s office and we talked to him,” Striker says. “Everybody went in there. He gave Matt his offer. He gave Cody his offer. So, I go in there and he’s like, ‘Hey Striker, I like what you do out there. You do a lot of good things and you play well. But I don’t know where you fit.’”

The slights didn’t faze him. He had long planned to leave his home state for college and told Callahan of his interest in Oklahoma when he was in ninth grade. Callahan assumed Striker’s fascination with the Sooners would fade, but Striker persisted. As a junior he pestered his coach to place a call to Norman.

Callahan did, in March 2011. Most of Oklahoma’s staff was out of the office on spring break, and the only person still around was then-defensive coordinator Brent Venables. Callahan informed Venables of Striker’s interest, and Venables agreed to screen a few YouTube clips. “It was not even five minutes later he called me back,” Callahan says. “And he goes, ‘I recruit the state of Texas, I recruit the state of Oklahoma. There is nobody like Eric Striker in either one of these states.'”

In those clips, Striker flashed past offensive linemen before they realized what had happened. Armwood coaches used to warn officials before games about Striker’s explosive first step: Just because he was in the backfield so quickly, they shouldn’t assume he was offside. “I remember watching the tape, and he was just a human missile coming off the edge,” says Venables, who extended a scholarship offer within 36 hours. “He had the innate ability to time up blitzing and just wreck shop.”

In January 2012, seven months after Striker committed to Oklahoma, Venables left the program. A week earlier Mike Stoops had rejoined the team, as co-defensive coordinator, and Venables, a Sooners assistant since 1999, decided it was time to move on. The news left Striker in a quandary. He still wanted Oklahoma, but he no longer knew if the team wanted him.

Other schools came calling, including Miami and USF, but Striker chose to honor his word. Venables kept vouching for the Sooners, and head coach Bob Stoops, Mike Stoops and linebackers coach Tim Kish all visited him in Florida to reassure him of his role. Everything changed, however, once Striker arrived on campus. Mike Stoops changed the defense from a 3-4 to a 4-3. Striker’s football identity -- a fast-twitch blitzing force off the edge -- was gone.

• ELLIS: Bowl Projections: Where will top teams play in the postseason?

Stoops tried to mold Striker into a weakside linebacker, but Striker struggled with his new duties. He initially felt heavy after bulking up, going from 195 pounds to 215, and he was relegated to mop-up duty while the Sooners defense flailed. Oklahoma allowed 778 total yards in a 50-49 win at West Virginia in Nov. 2012 and 663 in a 41-14 loss to Texas A&M in the Cotton Bowl. “They had Eric so heavy that if he blinked his eyes fast he was losing weight,” Callahan says. “He was trying to do the very best he could. It just wasn’t working.”

Striker asked Callahan to reach out to Florida or Central Florida, if only to explore his options to transfer. “I was like, man, [this is] not for me,” Striker says. “I want education, but I want to play football as well.”

Then, before spring practice in 2013, Stoops reinstalled the 3-4. He evaluated his personnel -- linebacker Geneo Grissom, for example, had split time between tight end and defensive end in ’12 -- and decided things needed to change. Striker turned in an impressive fall camp and locked up a starting job, thanks in part to lobbying from Kish. “I kept [telling Stoops], Eric Striker’s our best pass rusher,” Kish says. “I watch him every day. No one can block him.”

Striker had five tackles, including one for loss, in a 16-7 win over West Virginia on Sept. 7, 2013. He drilled Notre Dame quarterback Tommy Rees to force a pick-six on the opening possession of Oklahoma’s 35-21 victory in South Bend on Sept. 28. Then there was the hit on Texas' Case McCoy on Oct. 12: On first-and-10 from the Sooners’ 38-yard line, with just under four minutes remaining in the first quarter, McCoy took the snap in shotgun. He set his shoulders and was preparing to throw when Striker pummeled him, resulting in one of the most replayed hits of the year. McCoy flipped, feet over head, to the turf before officials flagged Striker for roughing the passer. “I think the referee kind of felt sorry for him the way it happened,” Striker says. “How he slipped up like that. He maybe just saw it and was like, ‘Oh, crap. That don’t even look right. Let me throw the flag.’”

Says Oklahoma defensive end Charles Tapper: “He killed him. They called it illegal hands to the face, but we all know it was a clean hit.”

Striker capped his sophomore campaign by terrorizing Alabama in the Sugar Bowl. He had seven tackles with three sacks, including the tomahawking strip-sack of quarterback AJ McCarron that sealed the Sooners’ 45-31 win with 53 seconds left. On that play he rocketed by Bama’s Cyrus Kouandjio before swatting McCarron from the blind side, producing a fumble that Grissom carried into the end zone.

“I was there,” Skelton says. “And before he made that last sack, I remember saying, ‘EJ, do something big.’ And he did.”

*****

Oklahoma’s 2014 season hasn’t gone according to plan. The Sooners were regarded as College Football Playoff frontrunners before falling to TCU, 37-33 on Oct. 4, and Kansas State, 31-30 on Oct. 18. The former was sealed on a failed fourth-and-one conversion in the waning minutes; the latter hinged on two missed field goals and a blocked extra point. Though Striker has delivered his share of standout outings -- he matched a career-high with eight tackles in a 45-33 win at West Virginia on Sept. 20 -- a team with national championship aspirations is now clinging to thin Big 12 title hopes.

As with most things, however, Striker sees it differently. “To me, success is not making the same mistakes that you’ve made before,” he says. “Success is living and learning. It’s making new mistakes.”

The best pass-rushers have a feel for the game that can’t be taught. It’s either there or it isn’t, and that’s obvious right away. Striker notices a quarterback’s tendency to wiggle his hands moments before signaling for the snap. He studies how a center tilts his head just before lifting the ball. He can read people. More important, he can read himself.

On a phone call during Oklahoma’s bye week in late October, Striker envisions his future after college. He alludes to playing in the NFL and “having a relationship with a nice young lady.” Then he shifts his focus inward, toward an outlook unlikely and inexorable, one that begins to explain how the reluctant, overlooked linebacker from Tampa became a can’t-miss prospect in Oklahoma. “Little things become big things,” he says. “If you work on the little things as a person, and try to find out who you are in life and your purpose, all those little things will eventually be big.”

When Striker looks in the mirror, he knows exactly who he is.