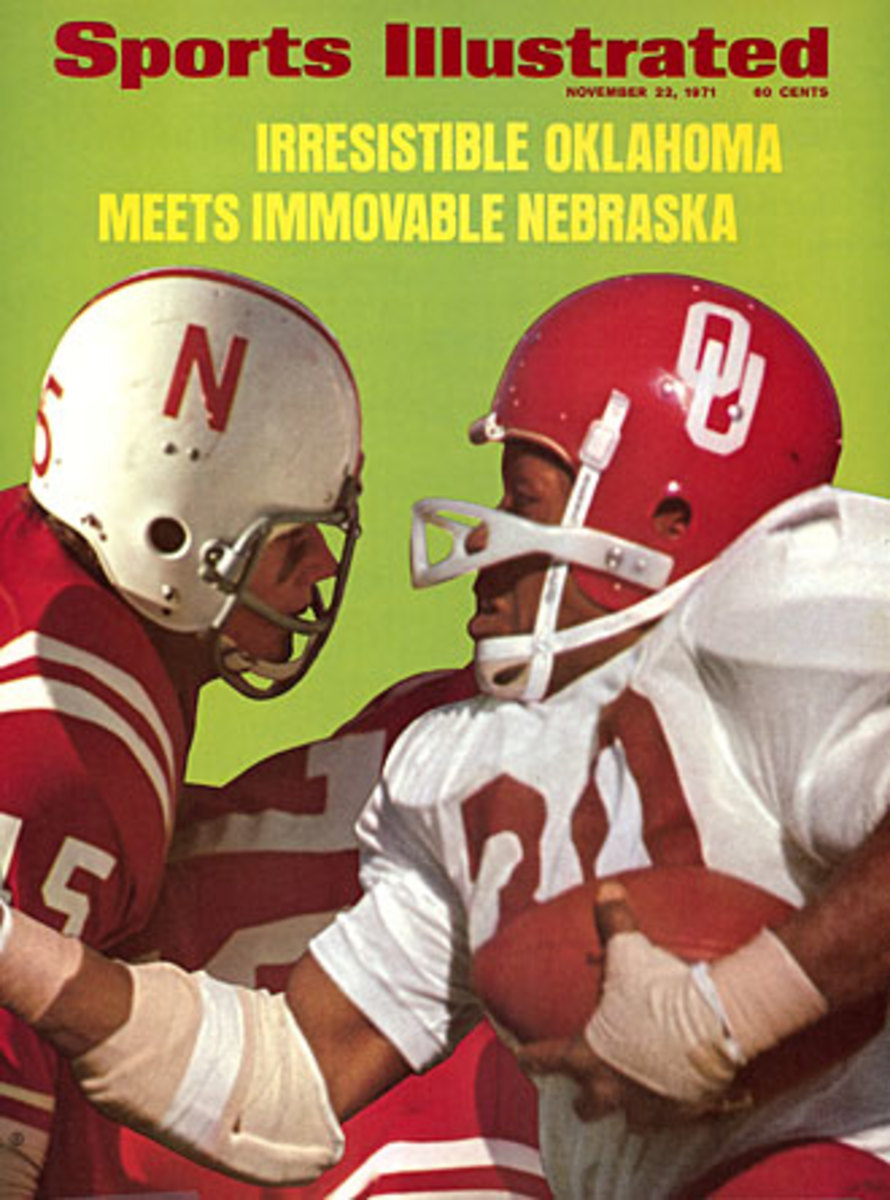

Nebraska Rides High: Cornhuskers win 'Game of the Century'

Unbeaten and No. 1, the Cornhuskers rallied for a dramatic victory over unbeaten and No. 2 Oklahoma in that publicized confrontation. Now they face an Orange Bowl battle with unbeaten Alabama

In honor of Sports Illustrated's 60th anniversary, SI.com is republishing 60 of the best stories ever to run in the magazine. Today's selection is "Nebraska Rides High," which was published in the Dec. 6, 1971 issue. It tells the story of one of college football's most famous games, the "Game of the Century" clash between No. 1 Nebraska and No. 2 Oklahoma that propelled the Cornhuskers to the national championship. It remains one of the best examples of what made writer Dan Jenkins such a legendary figure to the magazine's readers.

In the land of the pickup truck and cream gravy for breakfast, down where the wind can blow through the walls of a diner and into the grieving lyrics of a country song on a jukebox—down there in dirt-kicking Big Eight territory—they played a football game on Thanksgiving Day that was mainly for the quarterbacks on the field and for self-styled gridiron intellectuals everywhere. The spectacle itself was for everybody, of course, for all of those who had been waiting weeks for Nebraska to meet Oklahoma, or for all the guys with their big stomachs and bigger Stetsons, and for all the luscious coeds who danced through the afternoons drinking daiquiris out of paper cups. But the game of chess that was played with bodies, that was strictly for the cerebral types who will keep playing it into the ages and wondering whether it was the greatest collegiate football battle ever. Under the agonizing conditions that existed, it well may have been.

The Disciples Of St. Darrell On A Wild Weekend: A Texas football odyssey

Quality is what the game had more of than anything else. There had been scads of games in the past with equal pressure and buildup. Games of the Decade or Poll Bowls or whatever you want to call them. Something played in a brimming-over stadium for limb, life and a national championship. But it is impossible to stir the pages of history and find one in which both teams performed so reputably for so long throughout the day.

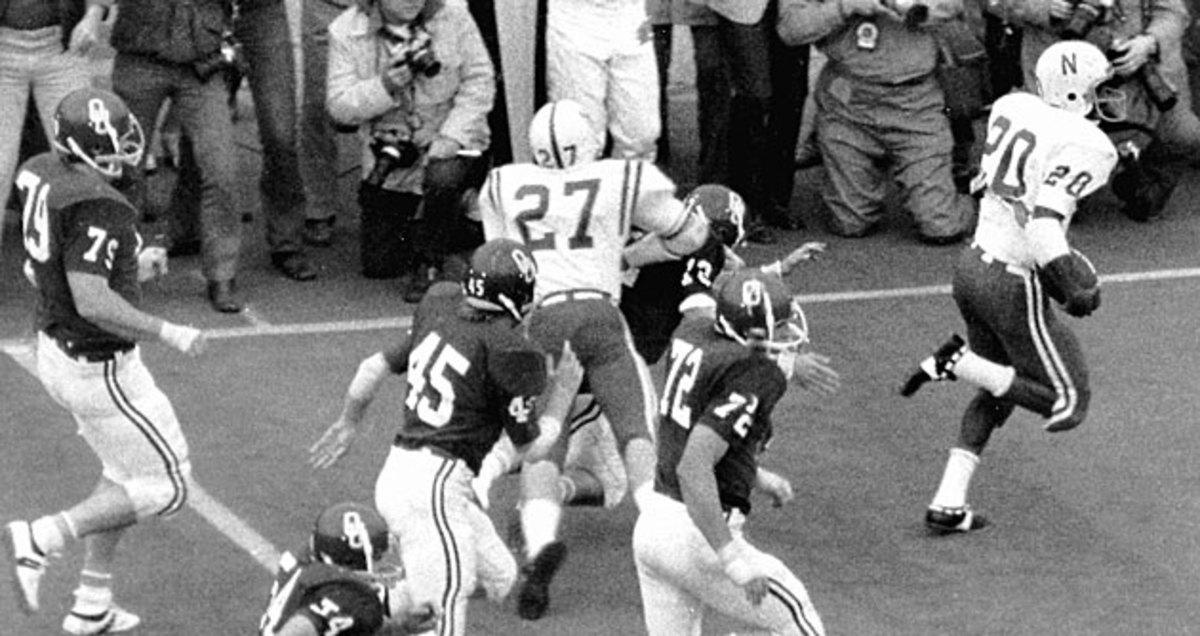

In essence, what won it for Nebraska was a pearl of a punt return in the game's first 3½ minutes. Everything else balances out, more or less, even the precious few mistakes—Oklahoma's three fumbles against Nebraska's one, plus a costly Nebraska offside, the only penalty in the game. There was an unending fury of offense from both teams that simply overwhelmed the defenses, maniacal though they were. But that is the way it is with modern college football. You can't take away every weapon. Both Nebraska and Oklahoma stopped the things they feared most, but in so doing they gave up practically everything else. From Oklahoma's record-cracking Wishbone T the Cornhuskers removed the wide pitch to the halfback, mainly Greg Pruitt, but in doing so they relinquished the keep, the fullback into the middle and most of all the pass. To stop Pruitt, the Cornhuskers were forced to cover Wide Receiver Jon Harrison man for man, which they did ineffectually, thus allowing Harrison to catch four passes in critical situations, two for touchdowns. From Nebraska's imposing I spread and I slot Oklahoma took away the passing game but gave up the power running attack. So the two teams swapped touchdowns evenly from scrimmage, four for four, andOklahoma added a field goal. But always there lingered the one thing they had not traded, that sudden, shocking, punt return by Nebraska's Johnny Rodgers.

It was one of those insanely thrilling things in which a single player, seized by the moment, twists, whirls, slips, holds his balance and, sprinting, makes it all the way to the goal line. Rodgers went 72 yards for the touchdown, one which keeps growing larger in the minds of all. And afterward, back on the Nebraska bench, he did what most everybody in Norman, Okla. probably felt like doing: he threw up.

"I don't know what I did or what I was thinking about," Rodgers said later. "The return was set up to the right, but I saw a hole to the left and cut back. I do remember seeing Joe Blahak up ahead and thinking he would get a block for me."

Oklahoma's Joe Wylie had punted the ball high and deep enough with the help of the gushing wind. The Sooner coverage was down fast, so fast that all of the 63,385 in Owen Stadium, not to mention the TV audience, must have felt Rodgers would have been much wiser to consider a fair catch. It never entered his mind.

Heavens to Omaha if Rodgers didn't catch it with Greg Pruitt right on him. He took the blow, spun around on his own 30-yard line and planted his left hand on the Tartan Turf to keep from falling. Strangely, Pruitt's lick only turned Rodgers away from the grasp of another lungingOklahoma tackier, Ken Jones. With that, however, he set sail to the right. But just as quickly he then darted back to the left, through a whole cluster of wine-colored Sooner jerseys. There the minuet ended. Rodgers was open and away from the flow of the coverage that had developed, heading for the left sideline. Ahead, his friend Joe Blahak, a cornerback, inherited the chore of screening off or blocking the last man with a chance to make a tackle, the punter, Joe Wylie.

Wylie never had a good enough angle on Rodgers, although Johnny finally began to tire and Wylie is fast. It was academic; Blahak bumped Wylie, and from there on, Rodgers, who has been doing this sort of thing for two years—scoring on punts and making other big plays—could have crawled retching every inch and still scored.

A Name On The Wall: Football player Bob Kalsu was the only U.S. pro athlete to die in Vietnam

What the punt return accomplished was monumental to the Nebraska cause. It ultimately allowed the Cornhuskers the luxury of an 11-point lead twice during the game, at 14-3 in the second quarter and at 28-17 late in the third quarter. It forced Oklahoma to go uphill all the way. And even when the Sooners' marvelous Jack Mildren overcame it twice, that bit of instinctive genius by Johnny Rodgers always had Nebraska's own brilliant quarterback, Jerry Tagge, in a position to retake the lead (or the game) with a single drive. Which Tagge coolly did when the scoreboard clock dictated that it was time, finally, and again, for the game to be won or lost by the Nebraska offense.

With 7:10 remaining in the fourth quarter, after Jack Mildren had run for two touchdowns and passed for two more to Harrison, his high school buddy from Abilene, Texas; after Mildren—always uphill—had Wishboned 467 yards in total offense for Oklahoma against the best defense in the country; indeed, after Jack Mildren had given the Sooners a 31-28 lead in a game that had every right, by now, certainly, to be running out of heroics, there was still Jerry Tagge, Johnny Rodgers, a refrigerator truck named Jeff Kinney and the Nebraska offense, which kept on coming like the disciplined Prussians they have become under Bob Devaney.

Devaney is normally a calm and likable man, resembling in that respect Oklahoma's Chuck Fairbanks. He had lost his cool only once during the game, he later admitted, when he turned to his defense on the sideline and said facetiously, "Why don't you guys give Rich Glover some help once in a while?" This was in reference to the fact that Glover, the nose guard, sometimes seemed to be stopping Oklahoma single-handedly. But when that last offensive drive of 74 yards had to be accomplished, Devaney was back in character. He was willing to let Tagge handle it. Devaney stayed calm. So did Tagge. So did they all.

The steady pounding had begun to wear down the Oklahoma defense, which had proved better than expected, and Tagge knew it. The ground game had worked throughout the second half, with Kinney banging his way to the 174 yards (and four touchdowns) he would eventually wind up with. The frenzied Oklahoma fans could sing Boomer Sooner and scream, "Defense, defense," all they wanted, but Jerry Tagge knew it had come down to his game to win.

"Nobody said a word in the huddle but me," Tagge said. "We all just knew what had to be done."

The drive required 12 plays and more than five minutes. Tagge would break out of the huddle and up to the line and frequently call an audible. He would key on the Oklahoma safety, who had to worry about a pass, and then run to the opposite side. He ran Kinney for a brutal 17 yards in which the big senior plainly broke three tackles. Tagge ran Kinney for 13 more yards on a play which saw the bruising I back cut grindingly outside and hammer down a wall of weary Sooners.

However, in between these two efforts by Kinney, whose white jersey was beginning to look like confetti, Tagge had to improvise a play that probably had more instant horror in it for both coaching staffs than any movie Vincent Price ever made. It was a pure shrieker.

Nebraska had come to third down and eight at the Oklahoma 46, trailing by three, the clock running, 4½ minutes left and the Sooners' Wishbone just waiting to get the ball one more time.

Now then, Jerry Tagge is not a fast man or very much of a scrambler, and while he is a splendid pro prospect because of his size and savvy, he does not have a quick release and he sometimes has trouble seeing any receiver other than the primary one—most often Johnny Rodgers.

Tagge called a pass right there, and the Oklahoma rush got him in quick trouble. He had no alternative but to run for his life, if not the ball game. He went out to the right, looking, looking, with OU's best defensive end, Raymond Hamilton, closing in on him.

At the last second before being trapped for no more than a minimum gain, Tagge saw the squirming Rodgers between two Oklahomalinebackers. He drilled the ball low, but Rodgers sank to his knees and somehow caught it at the Sooner 35, just as he had somehow made that punt return. Enough for the first down. The Prussians were still coming.

Four plays and two minutes later it was second down at the Oklahoma six, and Tagge, who had been constantly glancing at the clock, called time-out. He knew that only a busted play could ruin Nebraska. Tagge wanted to chat with Devaney.

As Tagge remembers it, their conversation went something like this:

Tagge: "I know we can score, coach, but I've been worried about eating up the time."

Devaney: "We're going for the touchdown. There won't be any ties."

Tagge: "We'll get it."

Devaney: "What's your best play?"

Tagge: "I think it's the off-tackle with Jeff."

Devaney: "O.K. Let's run it without any mistakes."

Jerry Tagge and his friends did exactly that. Kinney slammed into the left side behind Tackle Daryl White, knocked down somebody again and made four yards. So Tagge called the same play and Kinney rammed into the end zone. That, plus the extra point, made it 35-31 and sent an estimated 30,000 ecstatic residents of Lincoln, Neb. scurrying out to the airport to greet the football team that would keep all of the town's cocktail waitresses in their red sweatshirts with the white No. 1s on them until New Year's Day at least. And probably longer.