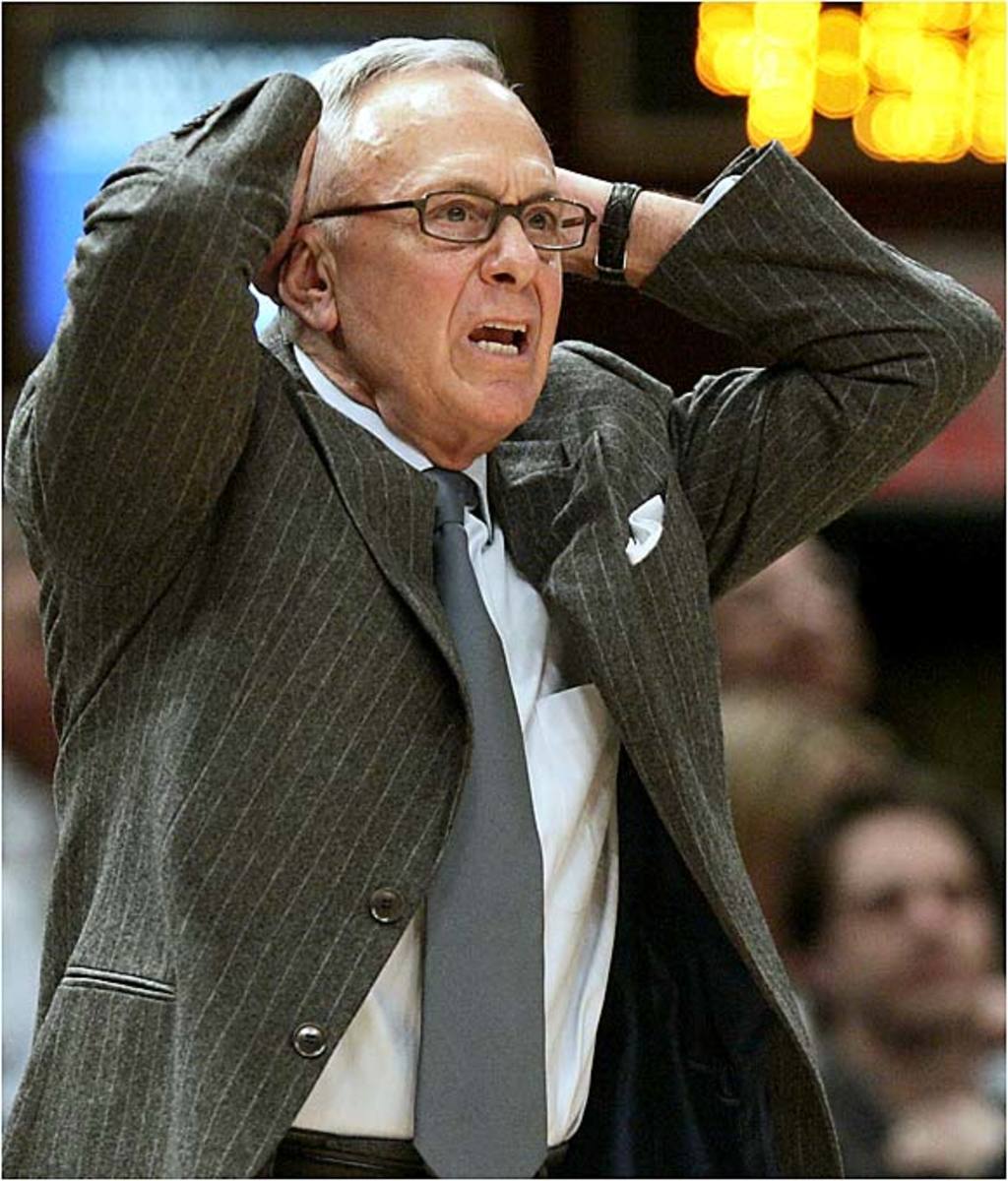

Q&A: SMU coach Larry Brown discusses his storied career

One day last summer, SMU assistant coach Jerry Hobbie looked over the roster that his boss, Larry Brown, had been holding while attending a recruiting camp. The sheet had scrawls all over, but they weren’t Brown’s thoughts on the players he was supposed to be evaluating. Rather, they were diagrams he had made while talking shop with other coaches. “When I sit with these guys, I drive ’em crazy because I like to pick their brains,” Brown says. “Their assistants get mad because [the head coaches] don’t watch anything.”

At an age when most people just want to play golf and watch sunsets, Larry Brown, 74, is in his third season at SMU, a school that has played in just one NCAA tournament in the last 26 years. It’s an unlikely gig for a Hall of Famer who is the only coach to have won both an NCAA title (Kansas in 1988) and an NBA championship (Detroit in 2004). He doesn’t need to work -- in ’06 the Knicks paid him an $18.5 million settlement -- but he still pines to be in a gym where he can watch ball and pick the brains of his colleagues. Larry Brown is still trying to get better, one scrawl at a time.

SD: The Bobcats fired you in December 2010 and SMU hired you in April ’12. Did you have any concerns that someone your age would have a hard time connecting with today’s players?

Larry Brown: No, I never thought about that. I’m embarrassed to say this, but I really think I’m the best teacher going. I just feel that. You ask all my guys in the pros -- I ran it like a college practice. They might not have liked it, but the ones who didn’t play [college ball] loved it because they got better. College kids want to be coached. They want to be taught. They might resist it a little bit early on, but the more you give, the more you get back.

Larry Brown's Odyssey

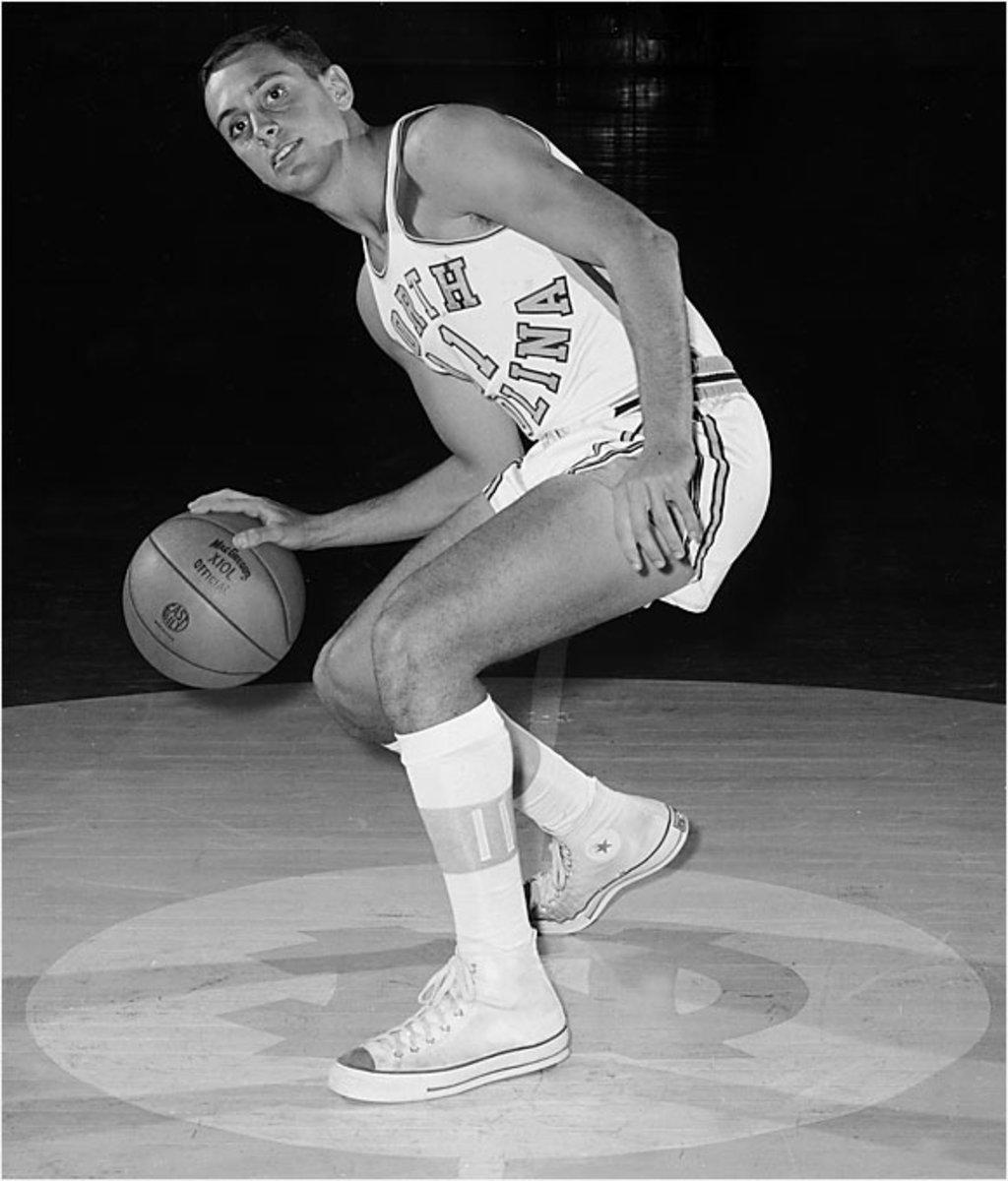

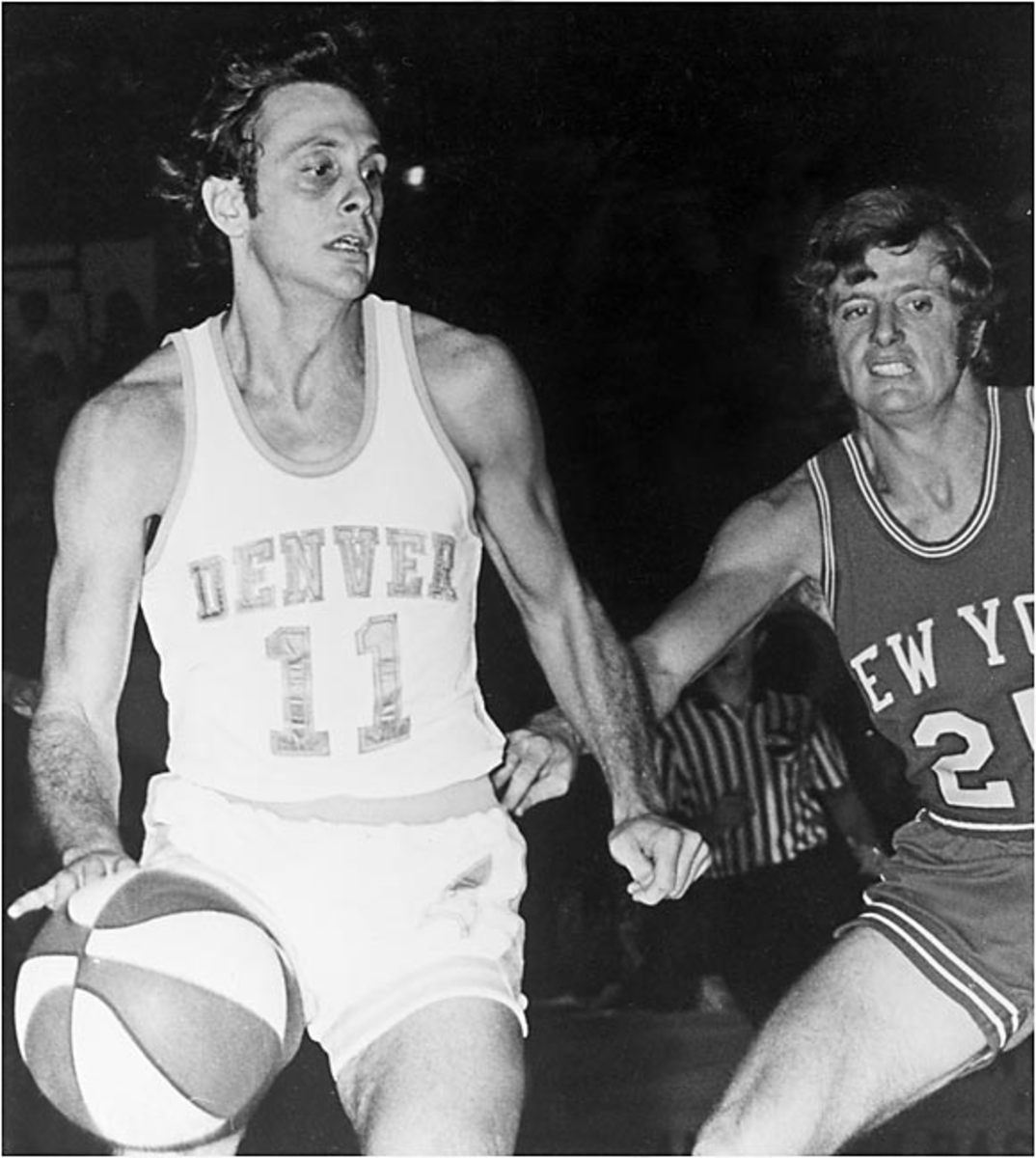

After playing for the 1964 U.S. Olympic team, Brown suited up for five ABA teams in as many seasons, was a three-time All-Star and became the league's all-time assists leader.

"I just want to help players get better. When you do that, good things happen," says Brown, whose first pro coaching job was from 1972 to `74 with the Carolina Cougars of the ABA, with whom he won Coach of the Year honors.

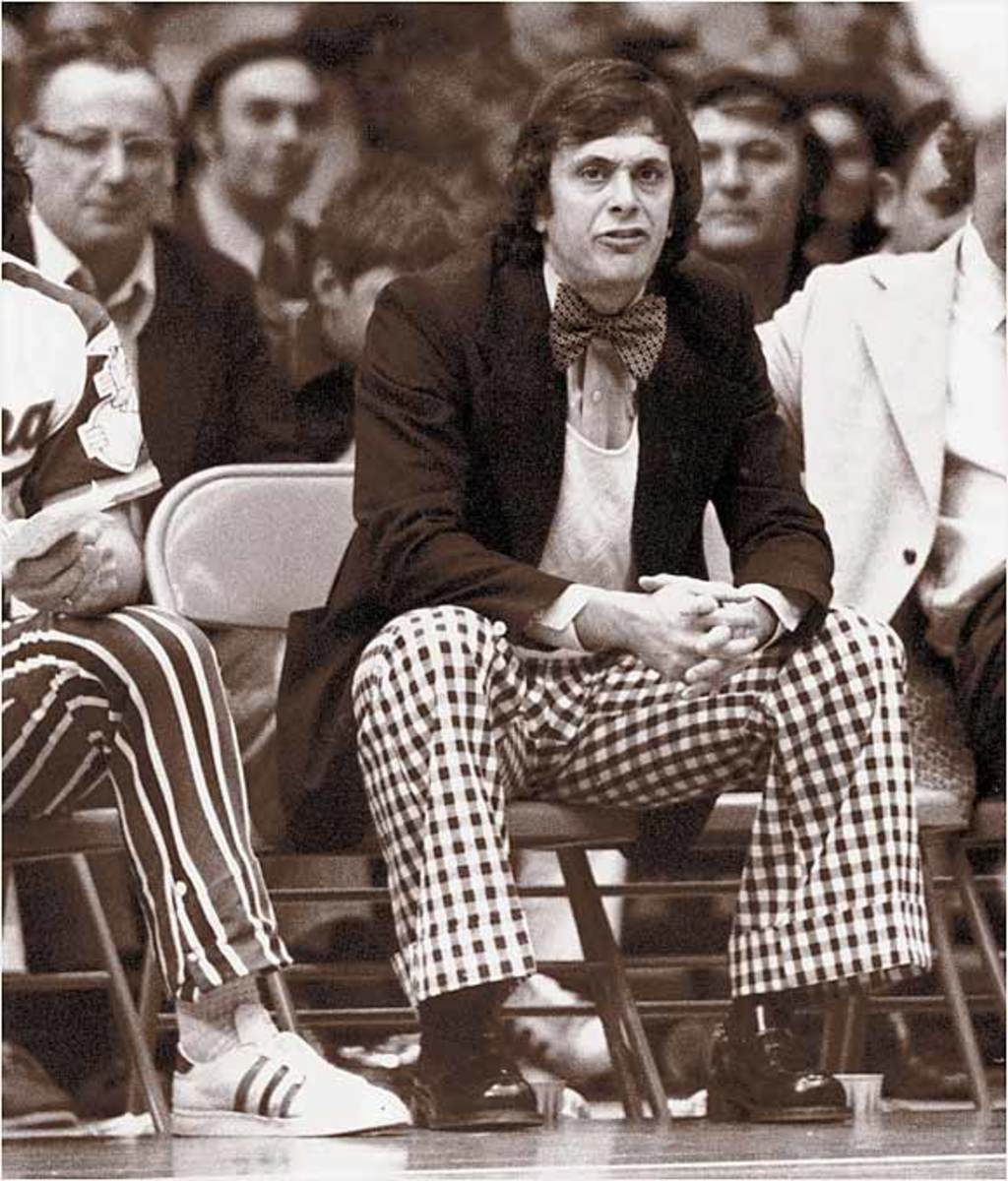

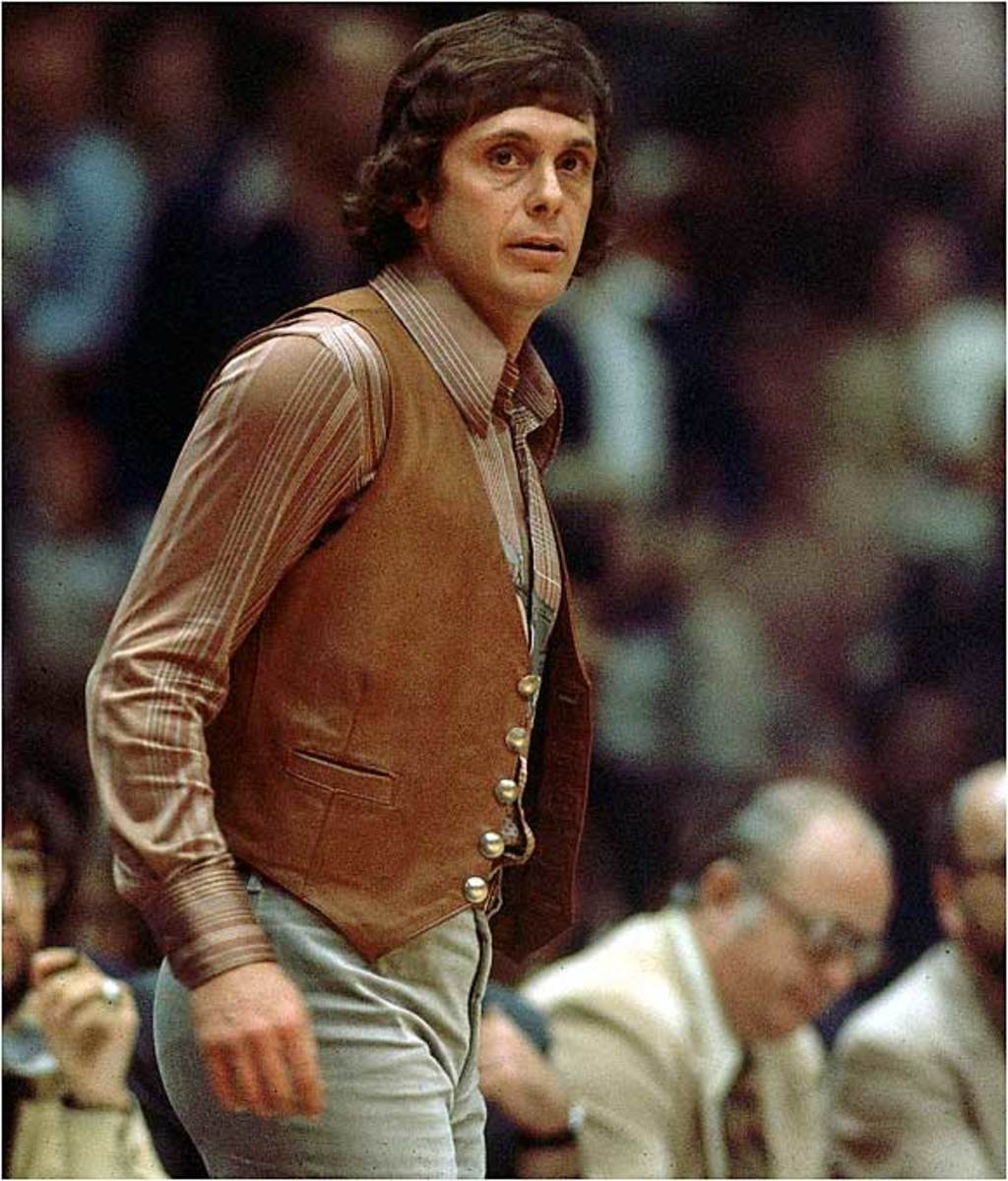

Before he had hip-replacement surgery, Brown was somewhat of a hip dresser in Denver, where he guided the Nuggets from 1974 to `79.

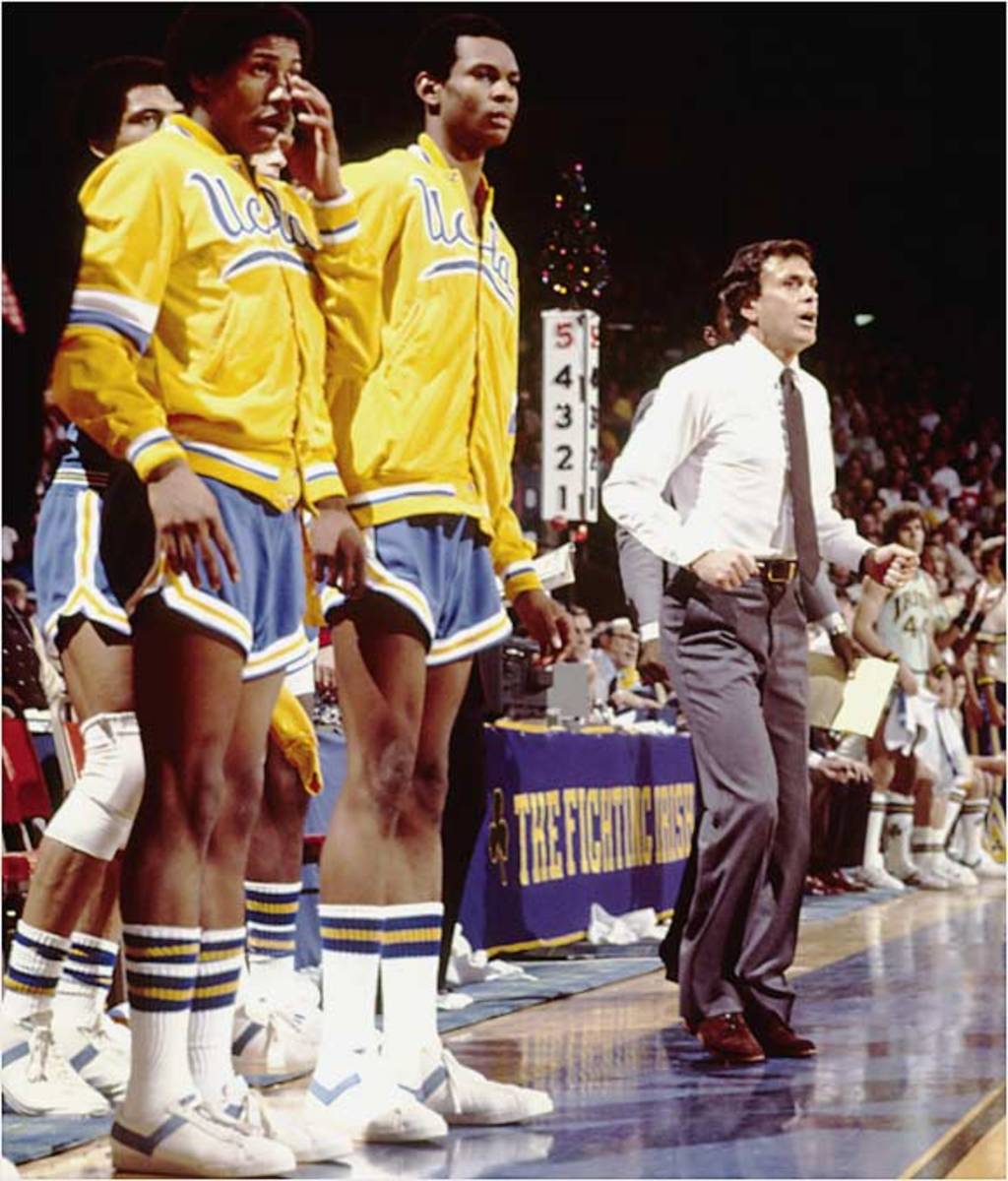

After resigning from the Nuggets in February 1979, citing health problems and fatigue in a tearful goodbye, Brown turned to a less stressful profession: coaching college kids instead of spoiled pros. In the first of his two seasons at UCLA, he relied on four freshmen and a 6-foot-5 center to get the Bruins to the NCAA championship game, where they lost to Louisville.

Brown didn't waste any time joining the New Jersey Nets when they quadrupled his salary with a four-year, $800,000 package in 1981. But the Nets didn't waste any time, either, in dumping him with six games left before the playoffs after learning that he had secretly interviewed for the vacant Kansas job. Team co-owner Joe Taub caught up with Brown just as the Nets were preparing to leave town on a flight out of Newark.

The Jayhawks experienced the best of times and worst of times with Brown. Kansas had five consecutive 22-win seasons under his tutelage and won the 1988 NCAA title but got put on three years' probation for violations under his watch and became the first NCAA champion not allowed to defend its national title.

"[The NCAA] spent 21/2 years investigating us [Kansas], and they came up with Vincent Askew. One kid. My violation was him going home and back to see his ill grandmother. I gave a kid $346 to fly home and back," Brown told the St. Petersburg Times in 1988. "The saddest part about this whole [NCAA] penalty is that kids who had nothing to do with this are being penalized. I've always maintained as a coach that you try to help all kids. But if they affect the other players, it's gotta stop. Obviously, I didn't do that because of what happened. I made a bad mistake in judgment. It was terrible judgment on my part."

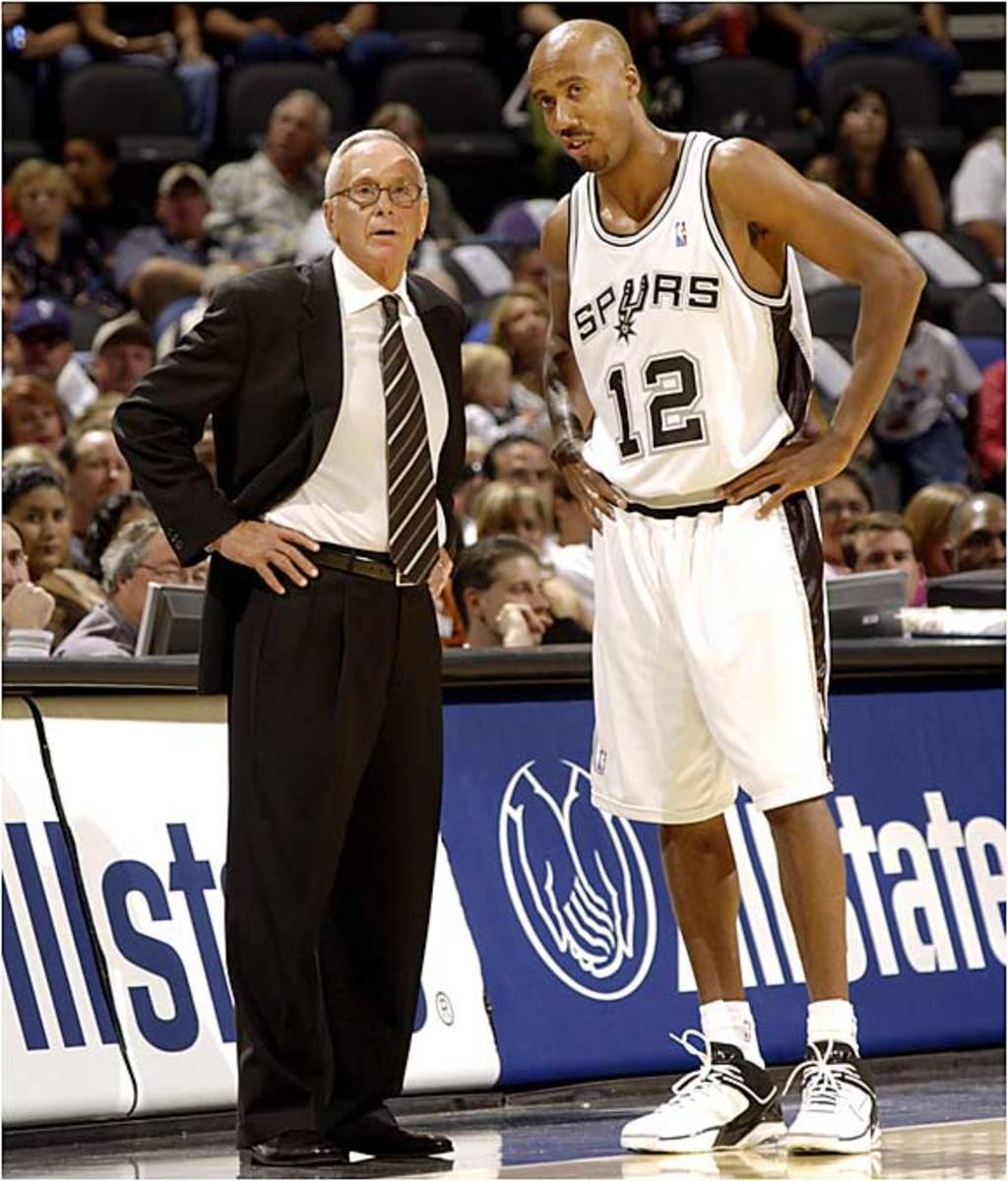

Two months after having led Kansas to the NCAA title, and hours after accepting and then turning down a repeat stint as UCLA's coach, Brown took a five-year, $3.5 million offer from the Spurs that made him the NBA's highest-paid coach. The team fired him toward the end of the 1991 season, prompting Brown to tell USA Today, "Yeah, this has been the first time I've been fired. Of course, that doesn't mean I haven't deserved it before."

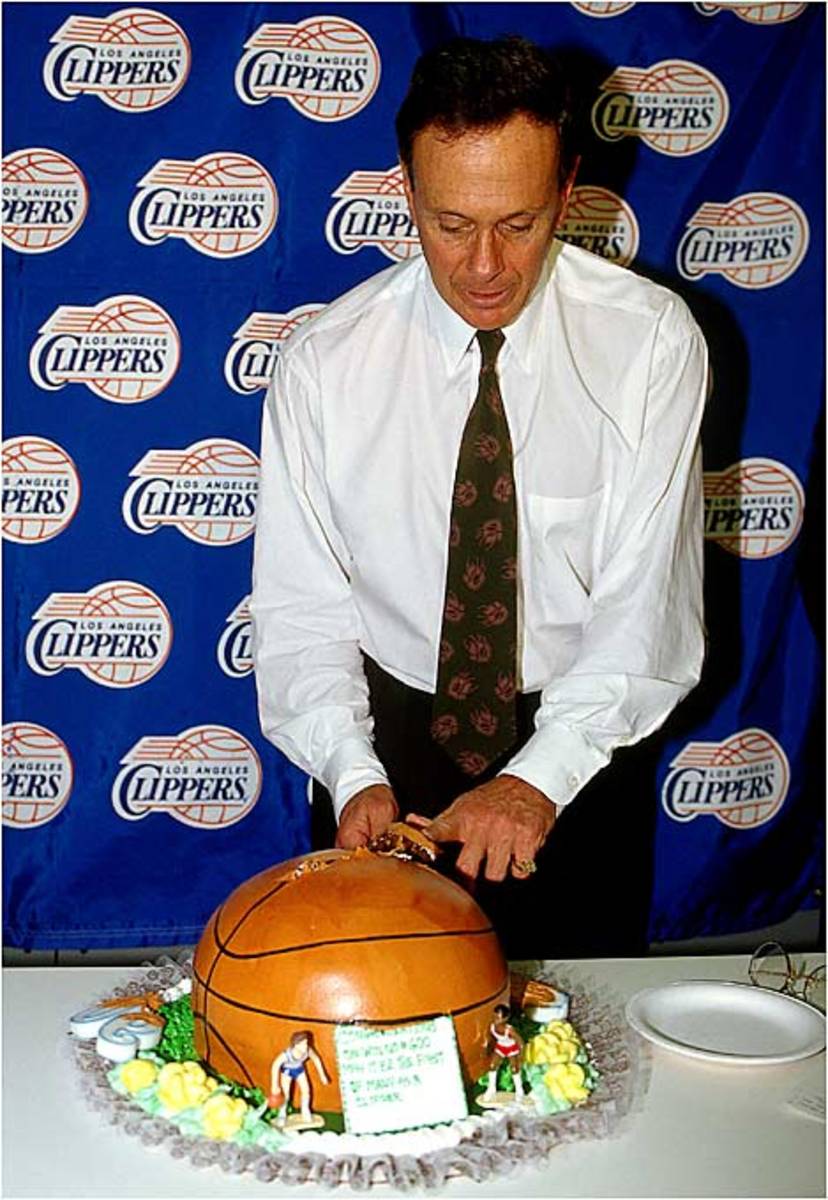

The Clippers found that they couldn't have their cake and eat it, too. Though Brown twice took the team to the playoffs, he infuriated team officials by going public with his unhappiness about personnel moves and left them in a lurch when he bolted with two years left on his contract.

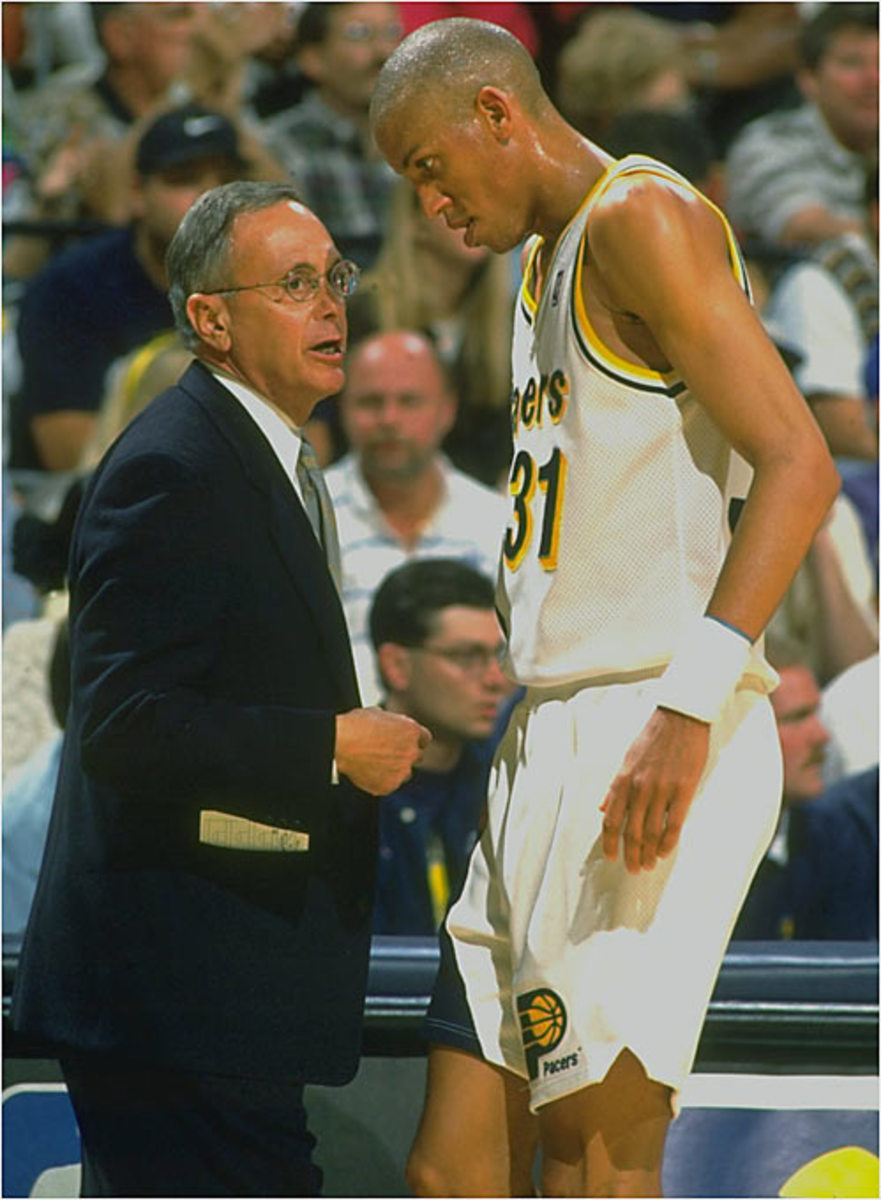

Hired by his old friend Donnie Walsh to coach the Pacers, Brown immediately led the team to 47 wins, the most in franchise history, and followed that with a pair of 52-win seasons. But he suffered his second losing season in 25 years of coaching in 1996-97 and called it quits.

Hours after resigning from Indiana, Brown flew to Philadelphia, where he spent six bittersweet seasons. Though he often battled with star guard Allen Iverson, the two did reach the NBA Finals in 2001, the same year Iverson was named league MVP.

In his first season with the Pistons (2003-04), Brown became the first male coach to have won both an NCAA and an NBA title, but the good times didn't last for long. Late in the next season, the Pistons grew tired of reports that Brown was negotiating for a new job and bought out his contract.

"By adding Olympic gold in Athens, Brown could have separated himself from all peers. That's where the movie was going," Chicago Sun-Times columnist Jay Mariotti once wrote of Brown. "But in Greece, Brown clashed with his unprepared, cruise-ship pampered team, prompting him to rip his players after games. Just when progress was detected, Team USA was blitzed by Manu Ginobili, Andres Nocioni and Argentina in the semifinals. The bronze medal was a severe blow to Brown's reputation."

The Knicks gave Brown a five-year, $50 million contract, but the team stunk in his first season, and he was fired on June 22.

SD: What’s the biggest difference between coaching in college and in the NBA?

LB: When you’re bad in the NBA, you’re in the lottery. When you’re great in college, you get multiple lottery picks. People always talk about this guy being a great coach and that guy being a great coach. Bulls---. They’ve got the best players. There are so many great coaches who are coaching—what do they call them? Mid-majors? Low majors? They’re unbelievable coaches, but no one knows it.

SD: Everybody says you’re this masterly X’s-and‑O’s guy. Were you a math whiz when you were a kid? Were you good at chess?

LB: I struggled in school. Math and science were difficult for me. But I can watch 10 guys play, and I can tell you what everybody did. It might be a curse because when you see everything, sometimes you don’t let your kids play. Coach [Dean] Smith was the same way. He cared so much about his players doing it the right way, he couldn’t let them just make a mistake and not learn from it.

SD: That fits into the accepted narrative about you: You go to a team that has been losing, and because you’re such a good teacher, you turn things around. But you’re also a perfectionist, so you wear people out, and it quickly becomes time to move on. Does that ring true?

LB: No. I always read guys who psychoanalyze me. I am always looking for something that’s perfect, but I’ve always had a great reason for leaving. Most of the time when I’ve left, it has been because of people I worked with, not the people I coached.

SD: Does it suck to get fired?

LB: Yeah. It’s somebody telling you that you failed. What’s worse than that?

SD: The last guy to fire you was Michael Jordan, your fellow North Carolina alum and owner of the Bobcats. Are you cool with Michael now?

LB:No, I don’t think so.

SD: That was a tough one, huh?

LB: He did it [just before] Christmas. It killed me. To have Michael Jordan tell you this? He said publicly that it was a mutual thing, but it was no mutual thing. He fired me. He was sitting on the bench during games. The players come off [the court], who are they gonna listen to? So I had to tell all my assistants, Phil Ford, my brother [Herb], Jeff Capel, LaSalle Thompson, I gotta tell all those guys at Christmas, We’re fired.

SD: You played for five seasons in the ABA. Your first three years you led the league in assists. Were you a better pro than you thought you’d be?

LB: No, I thought I was great all the time. [Laughs.] When I was 26, I got offered the Connecticut job, but the ABA started and I thought I could still play. This is a true story. I was, I think, the 54th pick [actually, 55th] in the draft, by the Baltimore Bullets. The GM came to Chapel Hill to see me, and he said, “Larry, you’re smaller than we thought you were. We’ve got Jerry West, Oscar Robertson, John Havlicek, all these big guards in our league. How are you gonna guard them?” I was a little wiseass. I said, “Last time I looked in the paper they were all averaging 30 a game. I don’t think anybody’s guarding them.”

SD: Did you ever talk to North Carolina about becoming the coach there after Dean Smith retired?

LB: Oh, yeah. After Bill Guthridge left [in 2000], Coach [Smith] called me and said, “Larry, I’m recommending Roy [Williams] because he’s in college and you’re in the pros. But if he doesn’t take the job, you’ve got it.” When Roy turned it down, Coach called me and said, “I want you to take the job.” I said I’d love it, that’s the greatest thing ever. Then he said they wanted to interview me. I said, “Why do I have to have an interview if you want me to have the job?” I would assume if Coach Smith, who’d been there for 39 years, wants someone to have the job, that will happen. So [then athletic director Dick] Baddour came to Bel Air and spent two hours telling me why I shouldn’t get the job. Like I was chopped liver. I called Coach Smith and said, “Coach, I don’t think they want me.” He said, “Oh, no. You’re going to get the job.” I don’t know what the reason was, but they didn’t want me to have the job. So they gave it to Matt [Doherty].

SD: We all know that Coach Smith has been suffering from dementia. When is the last time you saw him? How is he doing?

LB: Not too long ago I went with Phil Ford and Scott May. We went to a little sandwich shop. For the first hour, I don’t even know if he knew us. We started telling stories, and he started loosening up a little bit and smiling. He can talk, but he can’t watch TV or film. He can’t read. He can’t focus. He has 24-hour care.

SD: Herb coached the Pistons for parts of three seasons in the mid 70s and worked for you as an NBA assistant with three teams. You guys have had a rocky relationship over the years. How are things right now?

LB: Oh, you know, if I don’t hire him, he’s pissed at me. But at the end of the day, we’re all right. He wanted me to hire him at SMU. I said, “Herb, you’ll be 77, 78. You gonna be on the road recruiting all the time?” I recommended him to a lot of people in the NBA. These guys don’t realize how knowledgeable he is. I feel bad, but there’s no way he could come here. I know how hard it is for me.

• Seth's Davis's Hoop Thoughts: The upset of the season

SD: It has been 31 years since you hired Ed Manning, who at the time was working as a truck driver, to be your assistant at Kansas. His son, Danny, came the next year and eventually led your team to an NCAA championship. All these years later, every time a college coach hires an assistant who is connected to a player, that gets brought up. How do you feel about that?

LB:It pisses me off, because it’s been done a hundred times. People don’t know that I coached Ed Manning [in the NBA] for two years. We became real close. He had triple-bypass surgery and was driving a truck. A mutual friend said, “If you get the Kansas job, you should hire Ed.” So this was not me hiring a truck driver. This was me hiring a guy that I coached. I was close to him. When people asked me about Danny, I said, “If Ed can’t recruit his son, that’s a real problem, ’cause he’ll know whether I’m good or bad, right?” But if we don’t get Danny, we’d still have a hell of a guy on our staff.

SD: But let’s be honest. If there were no Danny, you wouldn’t have hired Ed, right?

LB:Obviously, when you consider the kind of player that Danny was, that has to come into it, but I really don’t know. I hope I would have, because my whole life I’ve hired guys I coached, but that’s a hard one to answer.

SD: When is the last time you spoke to Allen Iverson? Are you guys friends?

LB:We’ve kept in touch. When [SMU] didn’t get into the NCAA tournament [last season after going 23–9], he called me. He came here last year before the season, and he talked to our kids. It was spellbinding. I am more connected with him than anybody, and other than Coach Smith, he has affected my basketball life maybe more than anybody. I’ve said that God put me here to coach him. I know that for a fact. I can go anywhere and people might not know my name, but they know I coached Allen.

SD: Your son L.J. is a sophomore at SMU, and he lives with you. That sounds like a sitcom.

LB:It’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me. When he first told me he wanted to do it, I said, “I’m thrilled, but we got rules when I’m here. When I’m home, I want you to act like you would if your mom was here. When I’m gone, we got no rules.” He shares things with me. We never had any of this kind of quiet time together. Funny thing is, he didn’t like going to the pro games. He thought they were too predictable. But he loves the college games. I’m just shocked that he wants to be with me. It’s like hitting a home run.

SD: So what’s the over/under on how many years you’re going to keep doing this?

LB:You know, years ago people retired at 65. I don’t think that’s the case now. I’ve never worked. I’ve loved every minute. I’ve had my feelings hurt, I’ve felt like I let people down, but what motivates me the next day is that I love what I do. My body’s kind of changing. I’m losing my hair, I’m getting whiter, but I don’t feel any difference. I just don’t look in the mirror anymore.