SI Vault Q&A: Alex Wolff on 'Why Miami Should Drop Football'

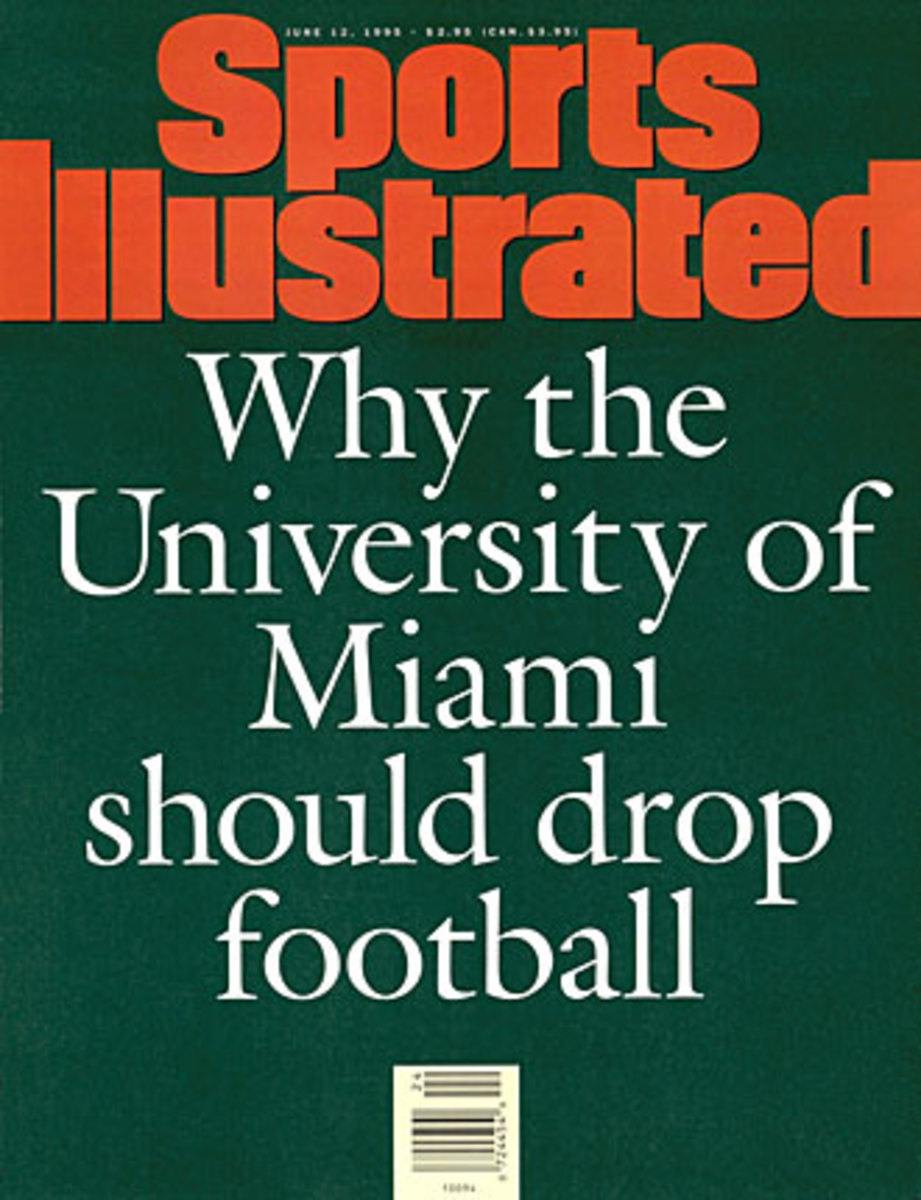

The June 12, 1995 cover of Sports Illustrated is one of the few in the magazine's history to have no artwork: no photograph, no painting, no illustration. Instead, there were eight simple words in white text against a green background and, in orange, the magazine's logo: "Why the University of Miami should drop football."

The stark, text-only cover in the Hurricanes' school colors made almost as much news as the story inside. There, SI senior writer Alexander Wolff penned an open letter to Miami president Tad Foote laying out the numerous, serious transgressions by players, coaches and administrators surrounding the Hurricanes' football team over more than a decade and advocating for a temporary shut-down of the program.

Almost 20 years later it remains one of SI's most pointed editorial takes. The school did not shut down the program and soon regained both its winning ways -- taking home the BCS national championship in 2001 -- and its reputation as a renegade program, amid a scandal brought to light in 2011 in which former booster Nevin Shapiro alleged he had provided impermissible benefits to dozens of former Hurricanes players.

Wolff spoke to SI.com about that 1995 story, from its origin to its impact.

SI: Whose idea was it to do this story?

SI Vault: Broken Beyond Repair: Why Miami should drop football

WOLFF: It totally originated with Bill Colson, who was running the magazine at the time and was part of a bake-off to see who would be the next managing editor. His interest in Miami football came naturally. He grew up in Coral Gables and his brother Dean was, at the time, on the board of trustees at the University of Miami, so Bill had followed Miami football and watched its troubles unspool with a lot of interest. He was the one who felt things had reached a critical mass and that we ought to weigh in.

What he found of particular interest was that they had this president, Tad Foote, who was trying to position this team as Stanford or Harvard with palm trees, and there was a tension that was impossible to resolve with the football team. It was Bill’s idea and I was brought in to make the case.

SI: How much time did you have to research and write it? And was the plan always to do an open letter?

WOLFF: I remember having three days to immerse myself and make the case. I worked with Jerry Kirshenbaum, another editor at the magazine, and we settled very early on on the idea of an open letter to Foote. He handed me a book about the University of Chicago, which had shut down its football program in 1939 because he felt it was being overemphasized. I’m reading through the book and the president of the University of Arkansas at that time, William Fulbright, commended that decision. Fulbright's daughter later married Tad Foote. So there was this moment in the piece where I could actually appeal to the president to heed the advice of his father in law here. If that is indeed what your ambition is, to make it a world class university, the football team is not taking you where you want to go.

• SI 60: Read every article and interview in the collection of the magazine's best stories

SI: Did you agree with the idea initially?

WOLFF: I was on board with the idea certainly to explore it, and I’d done pieces like that for Scorecard and in the magazine's feature well before, pieces with a point of view where you marshal facts and make an argument. But I do remember reading it over before it closed and thinking, Man, I convinced myself. If it didn’t believe myself before I do now. I think we made a really strong case. It was collecting all this evidence in one place. The appeal was to drop football to make the necessary changes and then bring it back. It wasn’t to walk away from football entirely.

SI: What was the impact of the story like for you?

WOLFF: It made a big impact when it hit, partly because of the iconography of the cover, especially with those colors: orange, white and green. I don’t cover college football all that closely -- college basketball has been my beat for most of these years -- but if you look at the work I’ve done I have a lot of sympathy for coaches and administrators who have to make their way through that system.

I’ve been accused over the years of being a bluestocking – being moralistic about college sports -- and as long as players are being exploited and not getting degrees there’s a place for a certain amount of moralism. Having been around college sports did help inform that story. After I wrote it I felt that it stood on its own merits. When I first came to the story I was a gun for hire, but by the time I finished it I thought we made a pretty good case.

It was an argument collecting the various rap sheets, and the thing that struck me is that it checked every box of violations: the academic chicanery, recruiting benefits, legal violations, boorish behavior. It was all there. You couldn’t quarantine it off and make excuses that it was just an isolated incident.

SI: Did you get to talk to Foote at all?

WOLFF: I didn’t have time to parachute into Coral Gables, but we obviously put in a request to talk to administrators. It's really just an argument. That was one of the criticisms of the piece, that there’s nothing new here. Well, no, there wasn’t. It was stuff that had already been collected and documented, and we put a frame around it, which I’m sure you could say was the cover of the magazine. By personalizing it with a letter to the president we could appeal to him on the grounds he had set. If you watch the first 30 for 30 on the U, Tad Foote is kind of this pinata that [former football coach] Jimmy Johnson and his players are whacking away at. He didn’t have any control over that program. They didn’t respect him or his vision. They hadn’t bought in. When I watched the first one I remember thinking there really was a divergence of cultures on that campus.

I actually interviewed Tad Foote once before that for a different story, I think about football dorms, and he was really thoughtful about the potential of football dorms to isolate athletes from the student body. You could see he was in for a culture clash.

SI: Did you think calling for the program to be shut down was going too far?

The SMU precedent [in which the Mustangs football program was forced by the NCAA to sit out a season and voluntarily sat out another in 1987 and '88] was already on the books, and also from college basketball there was the famous University of San Francisco case, where they had a president who said, Enough, and they dropped the program, although they eventually brought it back.

Bill Colson was very sensitive to all this. He almost knew too much. He was really up on what was going on there, the advantages and disadvantages they had -- they weren’t a big state school, didn’t have that huge alumni base; they got the huge crowds because they were the team of the city – and Bill’s point was, is this economically sustainable?

The three times I’ve written about Miami football have all been in the context of causing Miami football fans’ blood to boil. The cover story in '95, a story after the Nevin Shapiro thing and then Pete Thamel and I did a piece on how the NCAA couldn’t close that deal. I feel as though I’ve been thrown on Miami football at all their low moments.

SI: They didn’t take your advice in '95.

WOLFF: No they didn’t. After they won their next national championship, in 2001, I got this whole round of I told you so. I could see their point more if they said something like, How do you like us now?, but they said, See why this was such a bad idea? as if winning the title had vindicated all the stuff that had gone on, which almost proved our point.

SI: Did you follow the repercussions closely after that, and do you think they improved things there?

WOLFF: I do remember them making some progress on the academic side of things. There was a period, and I can’t remember the statistics, when Butch Davis was the head coach and they’d shown a real improvement in the academic climate around the program. But there's something Nevin Shapiro told me that rang really true: it’s South Florida. His point was very simple: You get these young, strapping guys who have the world at their feet and you plop them down into that particular environment and you’re expecting them to abide by NCAA rules. Was Nevin Shaprio responsible for them breaking those rules? Absolutely, but his point still has validity. It points back to that culture clash, and it’s much more systemic. A private university in that particular environment and these players have this feeling of entitlement that local media or fans or whatever it might be is feeding, and then you have boosters who are willing to feed it.

So they didn’t drop football, they went right back to winning championships and having a date with the committee on infractions.

SI: Did you ever hear from Tad Foote?

WOLFF: No, I never heard from Tad Foote and then I wrote [current president] Donna Shalala an open letter in the magazine in 2011 and never heard from her. I didn’t expect to because those were rhetorical exercises, and in terms of their ability to raise these issues they were worthwhile exercises. There have been cases when SI stories led to real social changes. Rick Telander did as story about steroid use at the University of South Carolina. They went into damage mode initially but then a year or two later a bunch of them visited the office and they said more or less, "Your story was the best thing that could have happened to us." They had a moment of reckoning, and it forced them to set right things that weren’t right. You don’t necessarily write these stories to affect change, but when it causes people to think and be reflective it’s a bonus.

SI: Do you think Colson would have done it he weren't auditioning for the full-time job of managing editor?

WOLFF: I think for a magazine that’s on the top of its game, regardless of the circumstances, a good ME is going to look for a story like that. I would hope so. We’ve tried to set the agenda, and that’s different from having an agenda. The latter is not good, but setting the agenda – to raise issues that people don’t necessarily see coming – no one was saying drop football. But if you can set the agenda that’s what people want to do.

SI: Colson did win the bake-off and was named managing editor a few months later. What did he think of the story?

WOLFF: He loved it, although he said it made for an awkward Thanksgiving that year when he went home to see his brother, who was a regular tennis buddy of Tad Foote’s. But good for Colson.

SI: Do you continue to hear much about that story?

WOLFF: Somebody else on our staff was down there on assignment once and some convenience store was selling T-shirts in the very same colors of our cover that said CANES ILLUSTRATED: Why SI Should Drop Dead. I taught a writing course years later and one of my students was a big Canes fan from South Florida so I gave it to him, but I had it in my wardrobe for a long time and appreciated the value of parody.