Preston Mattingly finds post-baseball sporting life on hardwood

Tic Price, the men’s basketball coach at Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas, likes when his players come by his office to chat. It’s a good way for the 59-year old coach to provide fatherly advice to his team, which includes players from eight states and four countries.

But when sophomore guard Preston Mattingly stops by, it’s more like “a couple of old men talking over coffee,” Price says. Mattingly will tell his coach how some of the players are very immature, aren’t taking the game seriously enough, or maybe aren’t getting enough sleep.

“He’s got a little more wisdom,” Price says with a laugh. “And we all know the reason for that.”

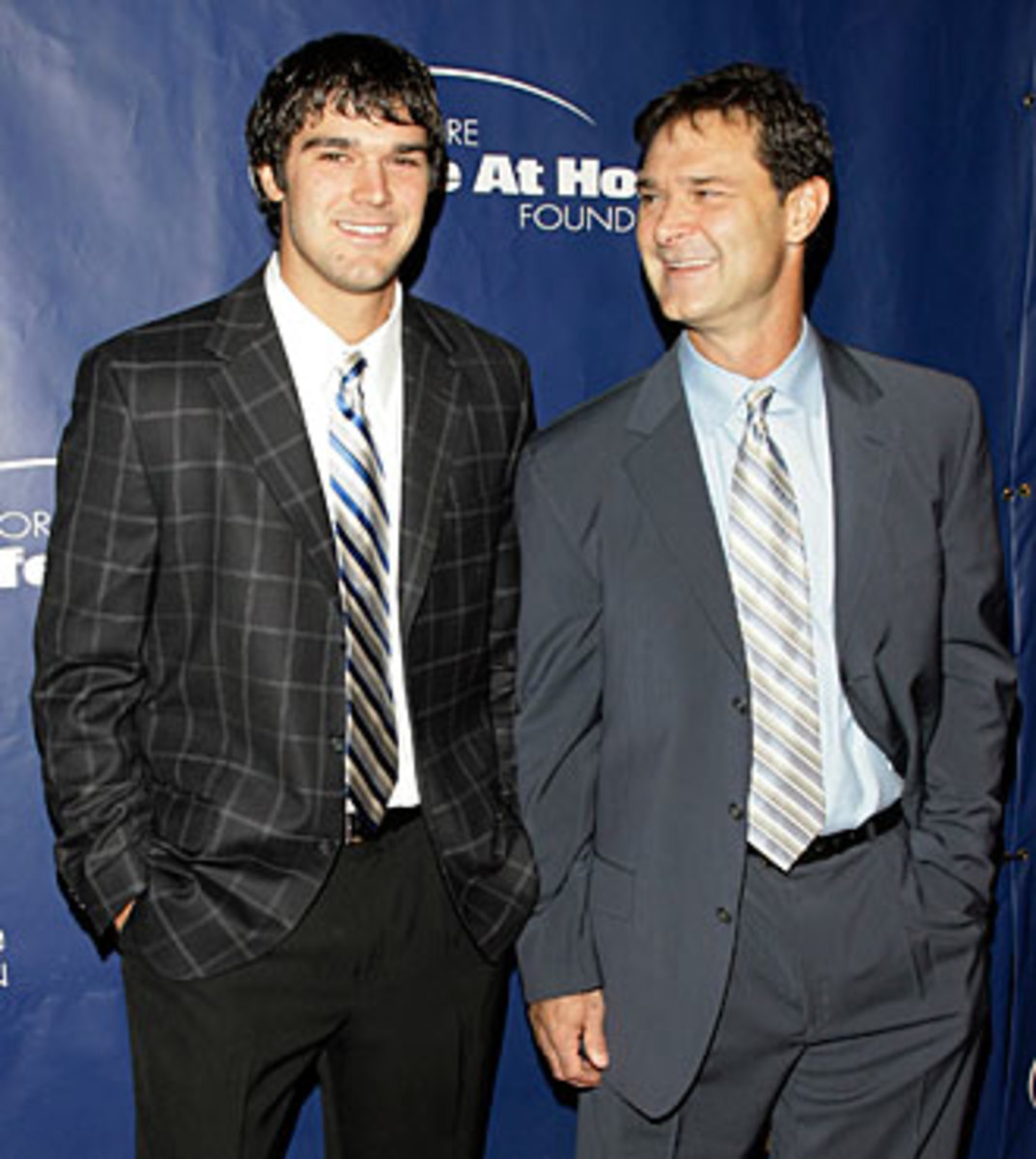

The first one is that Mattingly is 27 years old. He's also the son of New York Yankees legend and current Los Angeles Dodgers manager Don Mattingly. And Preston was once a first-round pick of the Dodgers who toiled six seasons in the minors.

“He’s been around sports his whole life,” says Price. “So I like to hear what he has to say.”

Unbroken: Kevin Ware rebuilding his hoops career away from the spotlight

How Mattingly arrived at Lamar a year ago is a story in itself. A shortstop drafted out of Evansville (Ind.) Central High School by the Dodgers with the 31st pick in 2006, Mattingly signed for $1 million but never got out of A ball. His baseball career ended in 2011 at High A in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif., where he hit .233, which was one point better than his career average.

“He could never get a feel for hitting,” says his father. “He had a lot of tools. Good size, good speed, arm and power in batting practice. But he never had any success to build on as a pro."

There’s no anger or frustration in the father’s voice. The elder Mattingly, the 1985 AL MVP who hit .307 in parts of 14 seasons in the Bronx, knows hitting a baseball is difficult -- especially when you start facing guys who throw 90-plus mph with wicked breaking pitches. He also knows some athletes are not wired perfectly for a game that’s full of failure.

“Pres is super competitive,” Don says. “And he was hard on himself.”

When Preston hung up his spikes and told his dad he was going to work for EGraphs, an electronic autograph company started by former big leaguer Gabe Kapler, the man who was known as “Donnie Baseball” during his playing career suddenly became “Joe College.”

“I said to him, ‘You’re finding out that you need to go to school,’ Don recalls. “Pres is a great networker. He’s got a great personality and people really like talking to him. But I told him, 'Without a college degree, someone’s really going out on a limb to hire you.' I felt like it was important for him to go to school. He didn’t want to at first, but I kept trying to change his mind.”

Preston told his father, “I don’t really want to go. But if I do, I’d like to try to play basketball.”

He had been an accomplished player at Evansville Central, averaging 20.9 points per game as a senior. Mattingly was recruited at the time by Pat Knight, who had played for Preston's high school coach, Brent Chitty, and was then an assistant at Texas Tech under his famous father, Bobby. By the time Mattingly was ready to return to the court, the younger Knight had become the head coach at Lamar.

"My high school coach always told me, ‘If you don’t make it in baseball, you’re going back and playing basketball,’" says Mattingly. "So I’d thought about it. And I went to Indianapolis and started working out. I had played some basketball during my years in pro baseball, but nothing at a high level. So I really had to work my butt off to get back in basketball shape. In baseball you want to put on weight. In basketball, you want to be lean, athletic and quick. It wasn’t easy, but little by little I started to get it back.”

As a 26-year old freshman last season, Mattingly appeared in 19 games, averaging 2.2 points and 1.7 rebounds per game for a team that went 4-26, the third-fewest wins of any team in the nation. With five games to go in the season, Knight was fired and replaced by Price. During those final games, Price gave Mattingly his first starts of the season and was impressed.

“He goes after every loose ball, he leads by example. He’s knows what it takes to be successful,” Price says. “I told him, ‘I need you to help me. Be a voice in the locker room. Be a leader.’ He just understands the intangibles, the focus required.’ He gives you the heartbeat, the pulse of the team. He does the dirty work, the blue collar things. He guards people. He’ll stick his nose under the boards for a rebound, take a charge, get a loose ball. He’s strong-willed, he will play in the moment and he will get on his teammates. But he does it in a positive way.”

The Cardinals, who play in the Southland Conference, are one of the nation's biggest surprises, having already more than tripled their win total from last year. They are 10-8 overall and 4-2 in the Southland Conference. Mattingly has missed four games but started eight, and he is averaging 3.0 points, 1.9 rebounds and 1.1 assists and shooting 40 percent from the floor. Those are modest numbers to be sure, but all are improvements from last year.

Lamar opened its season against SMU in Dallas in front of almost 7,000 fans, including a few famous faces. Preston’s dad in attendance, as were Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw, a Dallas native who had taken home the National League Cy Young and MVP awards in the two previous days, and Orioles manager Buck Showalter, who managed Don over his final four seasons in the big leagues.

“It was like celebrity row,” said Price. “We lost, but it was a fun experience for our kids.”

When he can’t make Preston’s games, Don is like pretty much every other father of a college athlete who’s away from home, watching the games on whatever Internet stream he can find.

“My dad loves basketball and he knows the game,” Preston says. “He’ll watch on the computer and we’ll talk after the game. He’s always positive. If you’re playing the game the right way, playing hard, he won’t say a thing. He gets irritated only if he doesn’t think I’m playing hard.”

MLB Winter Report Cards: Grading the offseasons of all 30 teams

Don says it’s a lot easier watching his son play basketball than watching him struggle in the minor leagues. The Dodgers tried to alleviate some of the pressure on Preston, trading him to Cleveland nine days after Don was named manager before the 2011 season. But he was soon released by the Indians and re-signed by the Dodgers, where he finished his final season.

“I was never comfortable watching him play baseball,” Don says. “He was a part of our organization. He had to deal with me. Now I just sit back and enjoy watching him. I know he’s happy and comfortable. And he’s at a point in his life where he knows, ‘I’m not going pro. I’m just going to enjoy this.’ He’s not a scorer. He’s more of a guy who knows how to play. I’d put him up against anybody defensively. He’s physical. He’s a guy who understands the offense and his role in it. He’s unselfish, prefers to drive and kick than score. A nice complementary player.”

Indeed, despite the years he has on his teammates, Preston is like a kid himself. When he’s on the court, anyway.

“It’s the most fun I’ve had playing sports in my entire life,” Preston says. “And when we’re playing, I don’t feel old. Now, when we’re off the court, at a social event, I definitely feel old. I feel like I’m the chaperone, there to make sure guys don’t get in trouble. I know my role there, too.”