SI Remembers: Writers and editors share their memories of Dean Smith

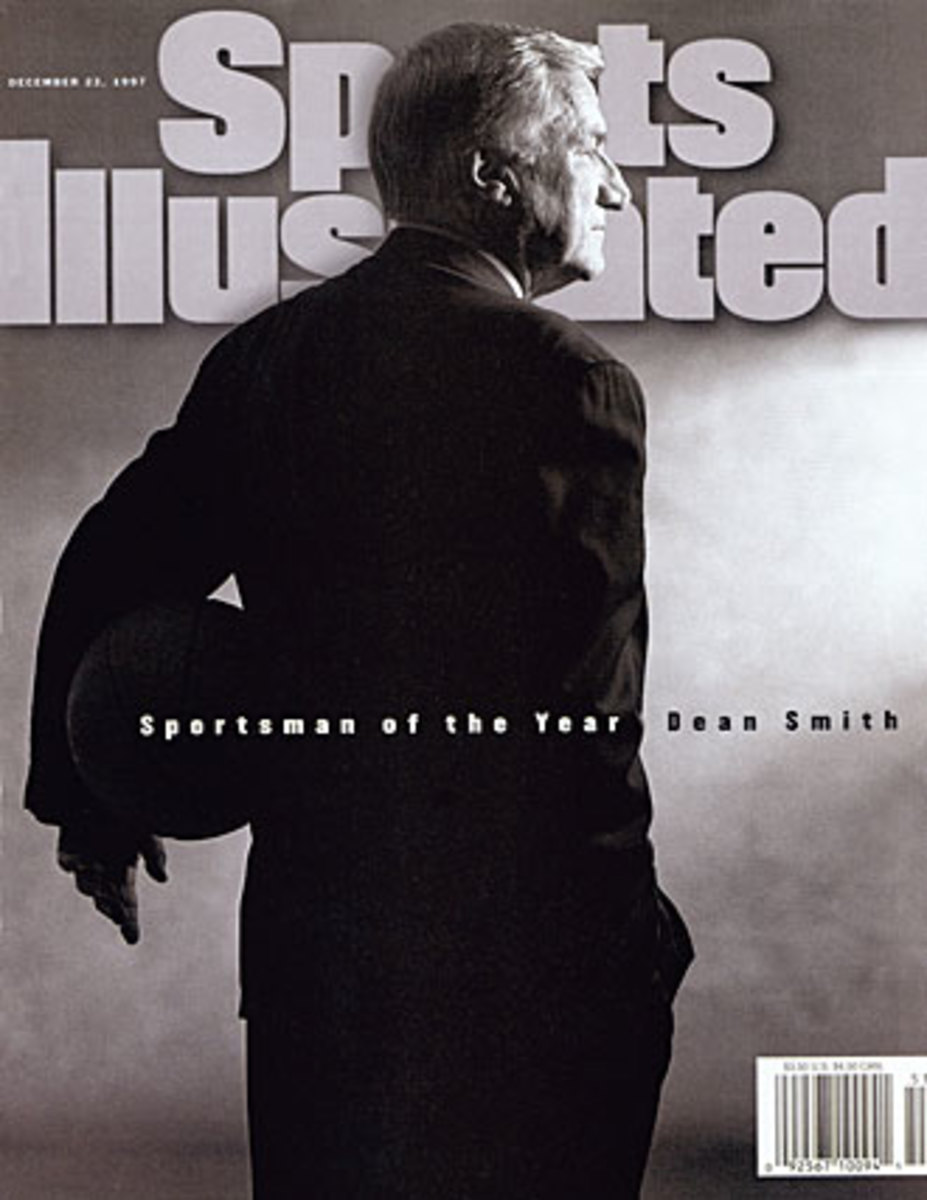

Legendary North Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith died on Saturday night at 83 after a long battle with dementia. Smith's outstanding record over his 36 seasons in Chapel Hill included 879 wins -- the Division I men's record when he retired in 1997 -- as well as two national championships, 11 Final Fours, 13 ACC tournament titles and the 1976 Olympic gold medal. Among the future NBA stars who played for Smith were Billy Cunningham, Walter Davis, Phil Ford, James Worthy, Sam Perkins, Brad Daugherty, Jerry Stackhouse, Rasheed Wallace, Antawn Jamison, Vince Carter and, of course, Michael Jordan, who did in fact average 20 points per game under Smith as a sophomore. Smith was an innovator who changed the game: thanking the passer, huddling at the foul line to set defenses, the run-and-jump defense, the 1-3-1 zone and, most notably, the Four Corners offense, which helped hasten the addition of the shot clock to college basketball.

His greatest legacy, though, came off the court. As a Tar Heels assistant he helped integrate the town of Chapel Hill, and as head coach he recruited the first African-American athlete in UNC history, Charlie Scott. Smith later campaigned against the death penalty and spoke out in favor of a nuclear freeze. He also graduated over 95 percent of his lettermen and never had any NCAA violations.

All of that has been well documented, however, so SI.com asked a variety of past and present Sports Illustrated staffers, many of whom are UNC alums, to share their private memories of Smith.

S.L. Price

SI senior writer, UNC Class of 1983

I try not to be a fool. So I’ll begin this by saying that I don’t presume to have known Dean Smith, because in general reporters can rarely “know” their subjects well, and student reporters, if swept by chance and timing into the orbit of greatness, are about as clueless as they come. At least, this one was.

I covered North Carolina basketball for The Daily Tar Heel during the 1982-83 season, the first after Smith won his first national title. Sam Perkins at his peak, Michael Jordan ascending, freshman Brad Daugherty coming into his own: The team won plenty. Smith’s graduation rate was 95 percent. The tone of coverage was, to say the least, complimentary.

Afterward, a scrum of writers would meet with Smith outside the locker room and he’d stand in the bowels of Carmichael Auditorium, cigarette cupped in one palm, the other sometimes holding a glass of something. Scotch was supposedly his drink, but no one ever asked. “We’d like to congratulate Whoever State,” he would invariably begin, no matter if UNC had won by four or 40, and then Smith would go on about how tough the opponent was and said nothing quotable, and after a few minutes he left and everyone hurried off imitating that famously nasal squawk. It sounded like penguins in retreat.

Dean Smith, legendary North Carolina basketball coach, dies at 83

By then, Smith had a reputation that became entwined with the university’s, and so he worked vigilantly to keep both unsullied. If there’s a photograph of him with cigarette or drink in hand I’ve never seen it. “We don’t do that here,” he’d say to abusive fans, or students trying to distract a free throw shooter. Opponents found that maddening. At the time Virginia was UNC’s biggest rival, and then-Cavaliers coach Terry Holland was infamous in Chapel Hill both for having said – after Smith allegedly shoved Virginia center Marc Iavaroni during a halftime set-to in a tunnel in 1977 – that there was a gap between Smith and “the image he tries to project”. He also named his dog “Dean", allegedly because of the whining.

What did I know? Nobody’s more alive to the idea of middle-aged hypocrisy than a 20-year old with a notepad, and it was easy then to wonder whether Smith’s morally upright persona jibed with the cutthroat competitor, the man in thrall to minor vices. Sure, he had helped integrate the state, and campaigned against the death penalty. But he had none of the qualities – glibness, bombast, self-promotion – that TV rewards; compared to flamboyants like Maryland’s Lefty Driesell and Jim Valvano of N.C. State, Smith seemed smaller than life. He liked it that way.

My two times alone with him bookended the season. Smith met with me for a pre-season piece at his locker before practice one afternoon, undressed, took questions while standing in his underwear. Surreal, yes, but I liked that a man supposedly so buttoned-up didn’t care that some student saw his knobby knees, his softening gut. The second came after the season ended; I had written a piece questioning the coming of the Dean Dome and the way UNC practiced athletics, and Smith called me in. Of all the school officials who did, he was the only one who didn’t say, ‘How dare you’ and instead asked real questions. He wanted to make sure, I think, that he hadn’t missed something.

Still, those were just glimpses. With time, though, I began to notice something else. With alums of other “legendary” coaches, I’d seen enough cocked eyebrows to understand that opinions often become shaded the farther one gets from the old school. Smith’s players and managers and coaches were different. I’d bump into Larry Brown, George Karl, Doug Moe, Kenny Smith, Matt Doherty five, 10, 20 years later, and their reverence for Smith hadn’t wavered a whit. On the contrary. Grown, rich, maybe legends themselves: They all still called him “Coach Smith” – and meant it.

Not long ago, I caught up with Daugherty, whom I saw regularly in psychology class when we were undergrads, and who left UNC to go onto a superb career with the Cleveland Cavaliers. We talked about Smith’s declining health, and soon Daugherty was speaking of the way Coach tailored his coaching to the player, not vice-versa. Jordan? “He would always challenge a guy like Michael,” said Daugherty, now an ESPN analyst. “We played Maryland one year, and Coach Smith calls timeout and he’s saying he’s going to take Michael off this one player and put him on another because it’d be ‘an easier defensive assignment’. That made Michael really angry, and we go back out and Michael dominates and wins the game.

“But then Coach Smith would get to me and break it down and explain. We’re playing Wake Forest, in a timeout, and he’s drawing a play and he wants me to run this play and he’s showing me exactly how he wants to run it -- three, four times in a row, front and back -- and he says, ‘You do this, over and over, we’re going to win this game.’ And we did. I talked to him later and that’s what he said: ‘The real Type-A guys, you could challenge.’ Guys like myself? He said, ‘If I told you to run through a wall, you’d probably laugh at me.’”

But it wasn’t Smith’s coaching during their college days that inspired such player loyalty. It was his own unending loyalty to them – and his coaching forever after. When I asked Daugherty to explain, he spoke for a long time.

“The funny thing is, he would call you,” Daugherty said. “He would call all of us -- me, Michael, if you were a manager on his team. He remembered weird stuff: My grandmother’s birthday, my mom’s, my daughter’s. And he’d write everyone handwritten notes or he’d call and say, ‘How you doing?’ and when I was in the NBA he’d say, ‘How many cars have you bought? What kind of watch are you wearing? Still wearing a Timex? You don’t need a Rolex.’

“He was just always really working hard to make sure you understood the humble side of life, working toward your goals, always being mindful of others, trying to give back to your community. And he’d always say, ‘Your community is where you’re at right now. You don’t always have to give back just to your hometown.’ Just stuff like that, man: Almost too-good-to-be-true type stuff.”

Daugherty knows how this sounds. These are scandal days in Chapel Hill, and skepticism fills the air. But if there was a gap between man and image, he never saw it. His coach was great and good to the end, he’ll tell you, and every fine word was true.

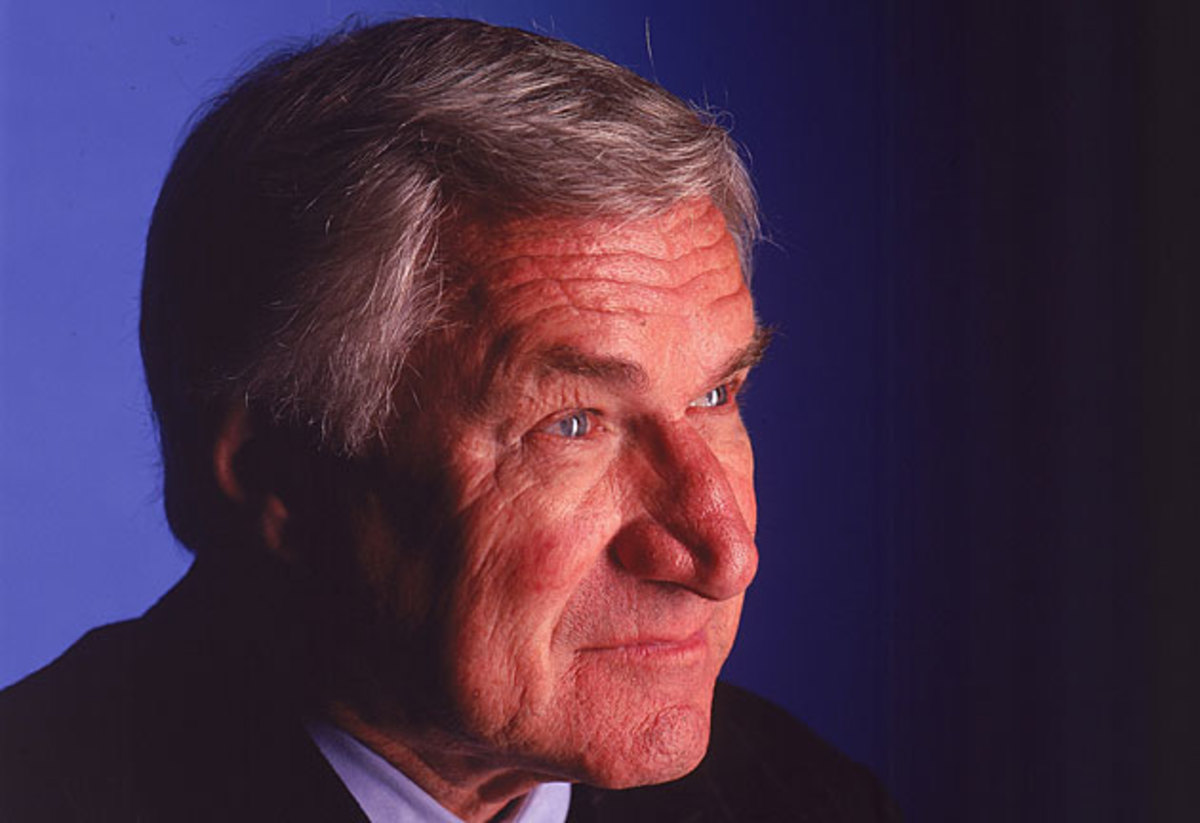

Frank Deford

Former Sports Illustrated senior writer

He was a very, very decent man. That was apparent from the very beginning. The first time I covered him was when he was finally coming into his own in the 1960s with Bobby Lewis and Larry Miller. That was only slightly removed from him being hung in effigy a couple years before.

He was always so forthright from the very beginning. On the one hand he was an extraordinary human being, even fragile to some degree, because he held himself to such a high standard. On the other hand he was extraordinarily confident in what he believed in. For example the Four Corners. A lot of people thought was sitting on a lead was a dumb thing to do, but that strategy changed the sport, even if it did cost him a championship in 1977 against Marquette.

More than any coach I know Smith developed this fellowship whereby his players always remained so very close to him. That’s true with a lot of coaches but in my experience there was never a coach who retained such affection from his players in the years that followed. It was extraordinary. They saw something in him, and yet those of us on the outside looking in couldn’t understand what it was that made all these guys retain this amazing connection with Dean all his life.

In 1982 I called him and said the magazine wanted me to do a profile on him. He said, “Frank, I won’t talk to you.” I was stunned. He said, “I don’t like some of the things you wrote about Coach [Bear] Bryant. So I’m sorry, I won’t talk to you.”

I was speechless. First of all I hadn’t expected it, and second, I thought, what a weird thing. He never told me what set him off, but a lot of people in Alabama didn’t like that story either. But Dean always stood up for coaches.

So I got my back up and I said, “Well, Dean, I’m going to do it anyway.” He said, “That’s fine Frank.”

SI Vault: Long Ago He Won The Big One: Dean Smith's best victory

What was so weird is that I went down to North Carolina and talked to his top assistant, Bill Guthridge, and with his good friend, Chancellor Chris Fordham, and I would see him every day because I would be there at the facility. And we always had the most cordial relationship. He never tried to get anybody else not to talk to me. Normally in those circumstances someone would tell people, “Don’t you dare talk to that guy who is doing a story on me,” There was none of that. He was not going to talk to me but that would not influence the way that he expected anybody else to deal with me. I always found that very, very intriguing and it was certainly the only experience I’ve ever had with anything like that. In the years that I saw him after that we were back to being cordial again as if it never happened. But that’s Dean. He was going to take it out on me professionally but in no other way.

I’ve never heard any other writer tell a comparable story. I’ve heard writers say he wouldn’t talk to them and that’s because they didn’t want to get involved in the story. He wouldn’t get involved because he was mad at me but he wouldn’t let that anger carry over to anyone else.

Sandy Treadwell

Former SI reporter, UNC Class of 1968

One afternoon Jeff MacNelly, who became a Pulitzer Prize winning editorial cartoonist, and I were asked to meet with Coach Smith. He told us that a guy named Charlie Scott was coming to visit UNC that weekend. He asked us if we'd invite Charlie to a party at our fraternity, St. Anthony Hall, on Saturday night. We did and Scott had a nice time and felt welcome and accepted. The next fall, he became a pledge, though he ultimately decided not to join.

Integrating sports and basketball took great courage and was, I believe, Coach Smith's most notable achievement. Jeff and I were always proud that he asked us to help in a very small, but meaningful way.

Larry Keith

Former SI writer and editor, UNC Class of 1969

Ivory Latta’s tweet nailed it. The former Carolina women’s basketball heroine attributed a quote to Dean Smith that summed up his approach to others: “Treat people as if they are special.”

Although we didn’t always agree on editorial matters, he certainly gave me the respect that let me feel that way. It began with our very first meeting in the fall of 1967, when I interviewed him for The Daily Tar Heel, and later that Final Four season when he invited me into his Carmichael Auditorium film room (closet, actually) as he broke down a game tape.

Our relationship matured over the years, first the following season, when I was his pre and post-game host for Chapel Hill’s radio station, WCHL, and, then, as an SI college basketball writer and editor. He sent me a novelty basketball after the birth of my first son. He sent a tin of “Carolina pop corn” when I was laid up with a bad back and for years after always asked about my condition. And after his father, Alfred, died in 1993, he sent me an old DTH Carolina story he had recovered “From my Dad’s collection” and highlighted the picture of the “young guy!!” that accompanied my byline.

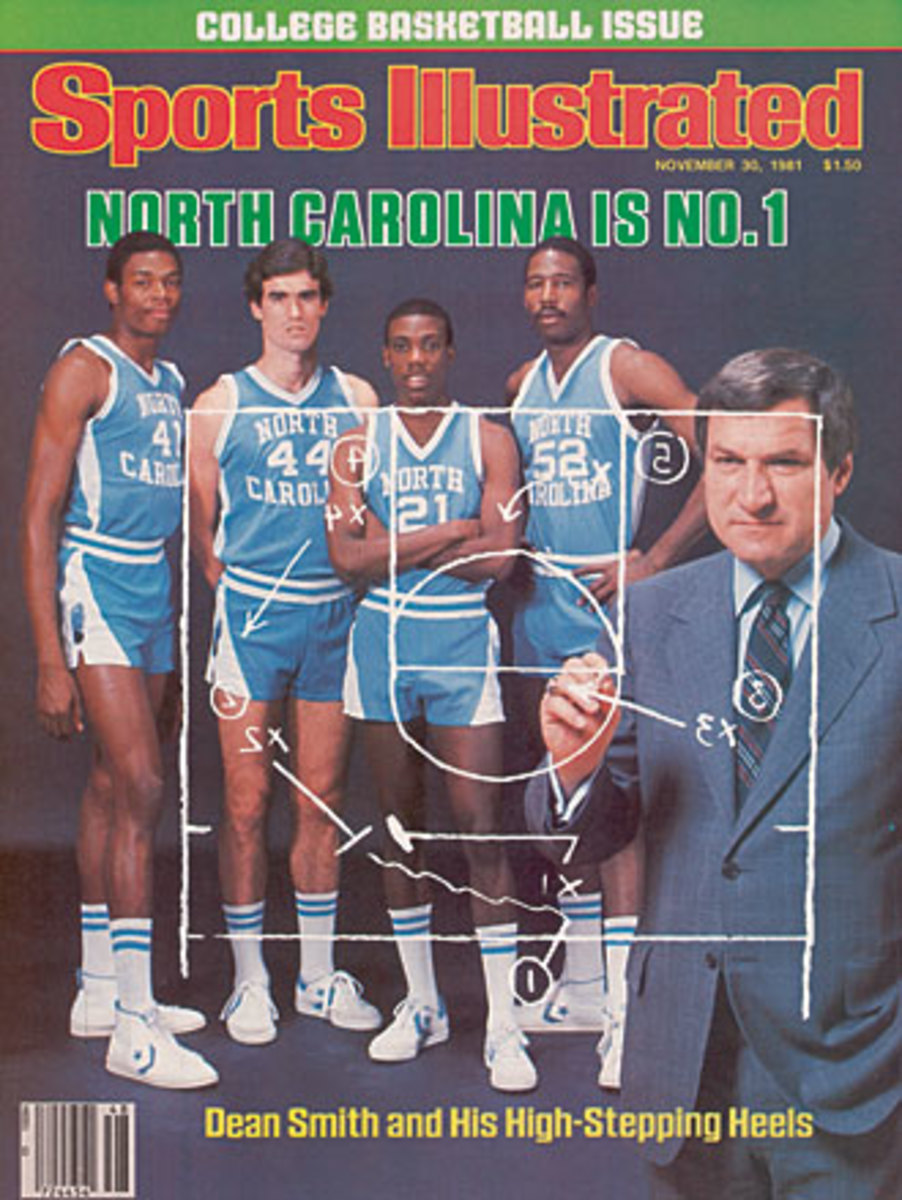

A much later story, a Sports Illustrated cover, in fact, became a one-sided running gag. When, as college basketball editor, I picked Carolina to be the country’s No. 1 team for the 1981-82 season, he refused to let freshman Michael Jordan appear on the cover with the four returning starters. Many years after that same freshman, who did indeed become a starter, had made the basket that won the 1982 national championship, he salted the wound in a letter acknowledging my 30th anniversary at SI: “You now have my permission to place Michael Jordan on the Sports Illustrated cover.” A few years after that, for my retirement, he graciously sought absolution: “Forgive me for not allowing MJ on the S.I. cover in the fall of 1981.” He added, “You have been a great friend for many years.”

Our friendship was renewed twice after he retired, when we had a convivial lunch with mutual friends in Chapel Hill and in a 2009 telephone interview for SI.com immediately after Carolina’s championship victory over Michigan State. By then, the downward spiral of his mental health was painfully underway.

But our most memorable and meaningful encounter may have been this one: Twenty years ago, during a New York City alumni reception, he interrupted his remarks to single me out in the crowd. I don’t think he was trying to treat me special as much as he was seeking to make me look special to the young person standing beside me, my teenage son. Damn, I wish I had gotten around to thanking him for that.

Gary Smith

Former SI senior writer who wrote a longform piece about Smith for Inside Sports magazine before coming to SI

One thing that immediately pops to mind is what a wreck his car was. It was trashed. And having seen how disciplined he was with his team, how meticulously he ran practice and how everything was perfect it was surprising to get in his car and see trash everywhere. It was a total mess.

The other thing that comes back is just what a very fair person he was. You could sense what a good person he was underneath. He really cared about people and had a good sense of right and wrong. Even outside of his circle of Midwestern, Caucasian, religious upbringing he really had a sense of other people’s worlds.

He had no interest in fame. He was kind and cooperative with me to the degree that he could be he just didn’t find importance in all that stuff. And yet the guys he played golf with said he was not above jingling the car keys when they were putting. That’s how competitive he was.

Alexander Wolff

SI senior writer

One day in the early 1990s I walked into Dean Smith’s office for a word with him. It turned out that he wanted a word with me — over a word.

The word was “quaff.” In a biographical sketch of the North Carolina coach, included in a book about basketball’s first 100 years, I’d mentioned how, despite being raised by Baptist schoolteachers and remaining devout through his adult life, he wasn’t above “quaffing” a Scotch. To which he objected. Not primarily because the description didn’t flatter him, but because it wasn’t constructive.

Here he was, trying to rid college sports of alcohol sponsorship and expose the hypocrisy of letting the lubricant of date rape and vandalism underwrite the games colleges played, and he was being described as “Scotch-quaffing.”

I protested that I didn’t mean to imply that he was a lush, or suggest that he was a hypocrite — and didn’t he in fact enjoy the occasional drink? Which were all true as far as they went. But he had already been to the dictionary. “Quaff” has a connotation, and it wasn’t the one I believed it to be. Words were supposed to be my business, and I here I was, called on the carpet of the Dean's office for using the wrong one. After leaving, I looked it up: To quaff is “to drink deeply” or “heartily.”

It was another instance of Dean Smith being right — a moment when, on the subject of words, he would have the last one.

Jack McCallum

SI contributing writer

The coach-takes-the-microphone-to-scold-the-home-crowd routine has been done several times through the years, I suppose, but the first time I saw it was on Jan. 9, 1982 at what was then Carmichael Auditorium. North Carolina was playing Virginia and Ralph Sampson, a player who always drew more than his spare of opprobrium from hostile crowds.

I don’t remember exactly what Dean Smith said that day, but he did admonish the home crowd to stop using obscenities, most of which were being directed at the 7-foot-4 Sampson. By then Smith was big enough that the maneuver — which came during the No. 1-ranked Tar Heels’ 65-60 victory over the No. 2 Cavaliers — was met with some degree of cynicism by those who had been covering him for a while. But it made a positive impression on me.

After the game I went hunting for additional quotes. As I recall, Malcolm Moran, who covered college hoops for the New York Times, was with me. We found our way to Smith’s office, opened the door and caught him catching a secret smoke, which he was known to do. He begged us to keep it out of the story, which, as I recall, we did.

I concentrated mostly on pro hoops for the magazine after that, but I was on the college beat for the 1995-96 season and made a preseason trip to Chapel Hill. Two things stick out from that visit. Unprompted, Smith told me: “No matter what universities tell you, they make significant admission allowances for athletes. No college team that has made the Final Four over the past 20 years has had a starting team made up of players who got 1,000 on their college boards.” I don’t know why he told me that, either to emphasize that his own school shouldn’t have a holier-than-thou attitude … or to make the point that Duke shouldn’t either.

Later, over lunch, we were talking about our families, and I happened to mention that my oldest son was in the process of applying to colleges.

“Well, I assume he’s a pretty good student, so, if you want, I could probably, you know, help him get in down here,” he said.

The offer came out of nowhere. I didn’t ask, I didn’t even hint. He didn’t do it to show off. He didn’t do it to demonstrate his power because Lord knows getting one Pennsylvania kid into Carolina is not exactly a show of power.

He just did it to be nice. I never took him up on it, but I never forgot it.

Tim Crothers

Former SI senior writer, UNC Class of 1986

In October 1985 I was a senior at the University of North Carolina and a jaded, know-it-all sportswriter working for the student newspaper, The Daily Tar Heel. Then I met Dean Smith for the first time. I visited his office one afternoon to interview him for a preseason scouting report on the Tar Heels, a roster that featured Brad Daugherty, Kenny Smith and Steve Hale. I had scribbled a reporter's notebook page full of questions about who Coach Smith believed would lead his team in scoring, lead his team in assists and rebounding. Smith never answered any of them. Instead, Smith asked me, "Tim, how do you define leadership?

I mumbled some reply that hardly left Smith dumbfounded by my insight. Coach Smith told me that he believed leadership isn't about statistics, but about caring, about developing committed followers and about humility, and then Smith shared one of his favorite phrases: A lion never roars after a kill.

It wasn't an interview so much as a lecture. Smith, ever the teacher, probably asked me more questions than I asked him. That was the day I became fascinated by coaching.

During my time writing for Sports Illustrated, most of my favorite stories featured coaches; Pete Carroll, Skip Bertman, Larry Eustachy and Red Klotz come to mind. I have also authored two biographies on icons; Roy Williams, who now sits in Smith's chair as the Tar Heels head coach, and Anson Dorrance, the longtime UNC women's soccer coach (both of whom credited Dean Smith with their success). All of that is inspired by meeting Coach Smith. I also coach my kids in rec basketball, where none of my lions roar after a kill.

Grant Wahl

SI senior writer

In the spring of 2007, a decade after his retirement, Dean Smith sat down across from me with a dry-erase board in a quiet corner of the arena bearing his name. I was in Chapel Hill to write a story on the secondary break, the attacking scheme devised by Smith and refined by his protege Roy Williams, and receiving a private tutorial from the master was like getting a painting lesson from Picasso at his easel. “It’s funny,” explained Smith, one of the game’s greatest innovators, pulling out a magic marker. “In the summers I’d go to the beach with my family, but I’d always be doing diagrams and looking at tapes.”

Putting marker to clipboard, Smith proceeded to show how the secondary break had evolved over the years from the time his then-assistant Larry Brown brought the idea of “flattening the defense” in transition back from his experience playing for Henry Iba at the 1964 Olympics. He went on to show me wrinkles that were added, like a screen for a big man who’d just screened for the point guard (“Rasheed [Wallace] in ’94 had so many dunks off that play”) and a lateral big-man screen that was first set *accidentally* by former Tar Heel Dave Popson in the mid-1980s (“[Eric] Montross used that one against [Chris] Webber in ’93.”)

There were so many reasons to admire Smith for what he did off the basketball court, including his stands for civil rights and against the death penalty. But in pure basketball terms he was *sui generis*, a master of invention and reinvention. Years after Smith retired, it was remarkable how much of his stuff was still regarded as cutting-edge. Even the tempo-free statistics that Ken Pomeroy took to a new level in the last decade originated in the fertile mind of Smith, a math major, who started measuring points-per-possession (i.e., efficiency) as an assistant at Air Force back in the mid-1950s.

A coach like Smith could see instantly through the clutter of bodies when an innovation had taken place. In the late-1990s Smith was watching Williams’s Kansas team when he noticed a sweet new wrinkle in the secondary break involving Paul Pierce. “We tried it and Coach Smith saw it and called me that night,” Williams recalled. “He said, ‘When did you start doing that?’ I said, ‘Today. Yesterday I started thinking about it and we put it in and it worked for two lay-ups.’”

As you get older, you realize how much there is that you don’t know, how much there is that you can still learn. If Dean Smith could do that with basketball into his 70s and 80s, then I figure that’s a lesson for all of us.

Alec Morrison

SI Custom Content Director, UNC Class of 1998

As the sports editor for The Daily Tar Heel during my junior and senior years at UNC, I covered Dean Smith’s final season and his retirement from coaching. I’d always rooted for Smith’s teams growing up, an inheritance passed down from my father, who’d gone to graduate school in Chapel Hill in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. And in the course of reporting on Smith’s career and retirement in 1997, I was enthralled by the stories of his compassion for his players and his liberal conscience on social issues. As journalists, we were supposed to be objective, of course. But it was hard not to lionize the guy.

As a DTH reporter, I rarely found the nerve to ask Smith a question during press conferences. I lacked the confidence, there among the throng of beat writers. But when I went to work on the publishing side of Sports Illustrated, writing sponsored features and profiles in the magazine, I finally got the chance to speak with him one-on-one. First, not long after I graduated, I wrote a piece about the 1976 Olympic team that he coached. Then in 2006, I was working on a series about classic sports experiences and wanted to interview him about the Duke-North Carolina rivalry. He called me to agree to the interview, and we set a date to meet in Chapel Hill.

We spent an hour together for that conversation, and looking back now, it feels like an extraordinary gift. At that point, he’d been retired for nearly a decade, so his presence seemed less imposing than I remembered. (For starters, he teased me about wearing a suit to the interview.) Of course, he still carried the perspective of a coach, often using “we” and the present tense when talking about the Tar Heels. And he was still Dean Smith, capable of soliloquies that took you on sidewinding tours of his years in the game while avoiding the answer you were seeking directly. But in a sense, we talked as fans, too — agreeing on how absurd it is to find yourself alone in front of a TV, shouting at events in a game you can’t control; acknowledging how much more fun it is to see a team exceed expectations than to saddle them with the hype of starting a season ranked No. 1.

In that conversation, Smith found a way to cover nearly four decades of ACC basketball, telling me about getting an orange thrown at him at Maryland in the 1970s, ruminating on the vitriol between UNC and N.C. State in the days of David Thompson, marveling at the intimidating atmosphere that Wolfpack fans could create in the old Reynolds Coliseum. I asked him about a classic Carolina-Duke finish from 1974 and he quickly segued into discussing a foul call against a Tar Heels walk-on named Pearce Landry in a 1995 double-OT heartstopper won by the Tar Heels in Cameron Indoor Stadium. (For the record, Smith thought the call was bogus.)

I found myself thinking about that conversation Sunday and the way so many precise details from games over the years were woven like strands in this dense web of all the games Smith coached. As fans, we remember moments, we remember seasons. Those of us in the tribe of Tar Heels all share this history, collectively, and the games are markers in the rest of our lives as well. Smith’s career gave us this remarkable connective tissue. I met some of my best friends while writing about sports at The Daily Tar Heel. My father died when I was seven years old, but I feel some part of him within me every time I sit down to watch a Carolina game.

As we were finishing our conversation back in 2006, Smith said, “It’s remarkable the way we get involved with sports. You chose the right field.” But it’s hard to imagine caring so much, without having his teams and his example to follow all these years.

Ted Keith

SI associate editor, UNC Class of 2002

Of my small handful of personal interactions with Smith, one stands out: I came to Chapel Hill, N.C., in the fall of 1998 as part of the first freshman class to arrive at UNC since 1960 that knew Dean Smith would not be the head coach of the Tar Heels. He had retired the previous October, several weeks into the first semester and just days before the start of practice. But those ’97-98 Heels had shaken off the shock of Smith’s abdication and managed just fine without him – going 34-4, winning the ACC tournament and reaching the Final Four under Bill Guthridge – so the first true test of what would become of Carolina lay ahead in Year 2 AD. I was as curious – and concerned – as any of my fellow frosh about whether Vince Carter, Antawn Jamison, Shammond Williams and, yes, Smith himself, could be adequately replaced.

As the sports editor of a brand new campus magazine called the Blue & White, one of my first story ideas was to do a piece on Smith and what he had been up to in his first year of retirement. Some of it we knew: he had appeared on TV as part of CBS’ NCAA tournament coverage the previous spring, and he still kept a basement office in the arena that bears his name, where he could assist the coaches, visit with the players and respond to annoying requests like the one I was about to make of him: Would he agree to sit for an interview and talk about himself? Smith, famously reticent in the public eye, perhaps sensed that our fledgling publication hardly qualified as a significant turn in the spotlight. Twenty minutes, tops, I said when pitching the school’s SID. To my surprise and delight, the word came back: Coach Smith was in.

A day or so before we were to meet, however, he called to tell me he wouldn’t be able to do it after all. He wanted to avoid publicity of any kind, and it wouldn't be fair to say no to other people's requests but say yes to me. He also said he would be happy to explain his rationale in person if I still wanted to meet.

I was not around to receive this message from a local deity, but its presence on my voicemail briefly made me a celebrity around Hinton James dorm. One stranger, upon overhearing the news, even gave me a “Get out!” shove that would have made Elaine Benes proud, before he joined the group of kids who had to hear it to believe it.

On the day of the interview I arrived at what had been, for the first 11 years of the building’s existence, Smith’s office, but by then belonged to his successor. He quickly reiterated his reasons behind his reluctance to do the story and apologized. That part took two or three minutes. He then spent more than an hour interviewing me. What did I think of Carolina so far? (Loved it.) What classes was I taking? (Introductory courses in Econ, Poli Sci, Anthropology, American History and Psychology.) What did I want to major in? (Journalism.) Was there anything he could do to help me? (Other than do the interview.) Did I know that he had a daughter who was an undergrad at the time (I did), and did I know her (I did not)? What was meant to be a discussion of him and about basketball instead steered almost entirely clear of both those subjects.

In the end, my visit lasted almost five times as long as the interview itself would have. The memory of it, however, will last the rest of my life.