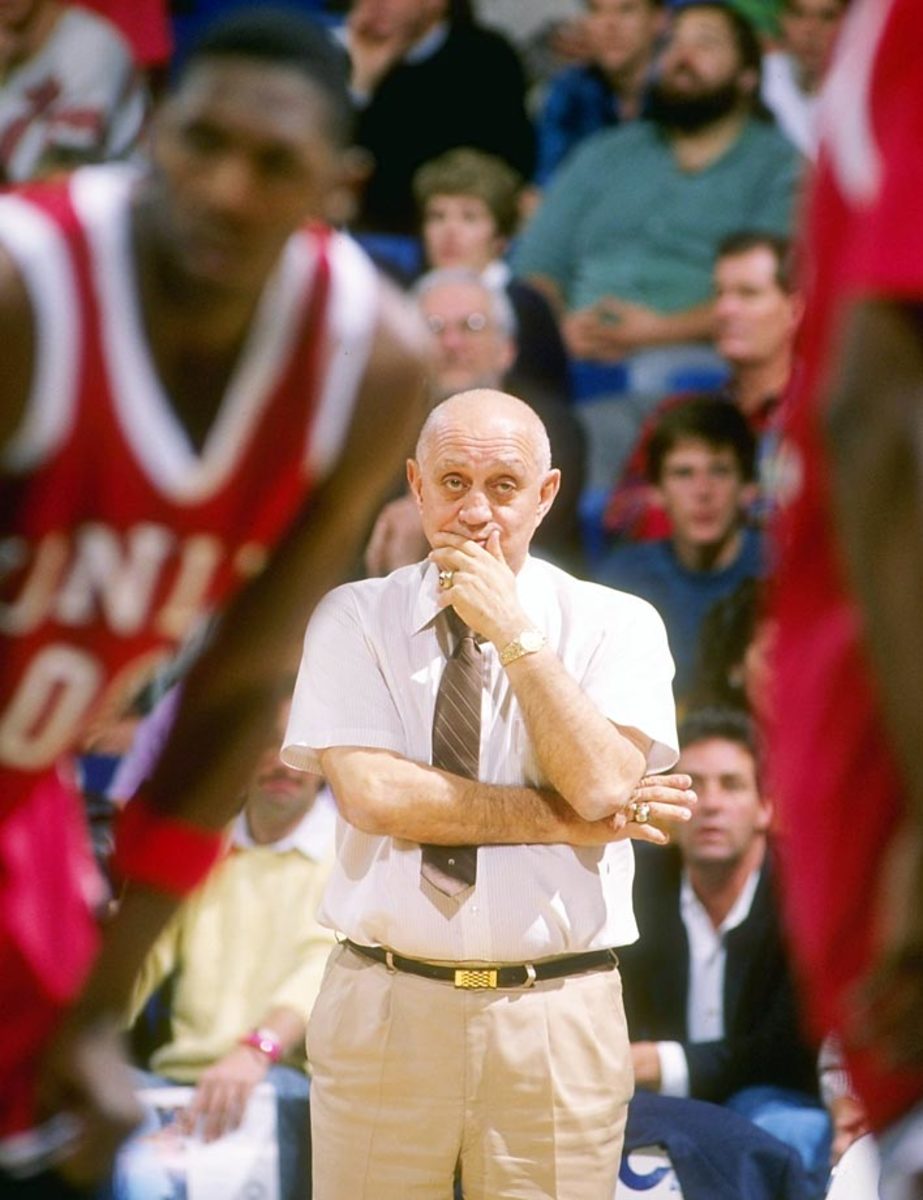

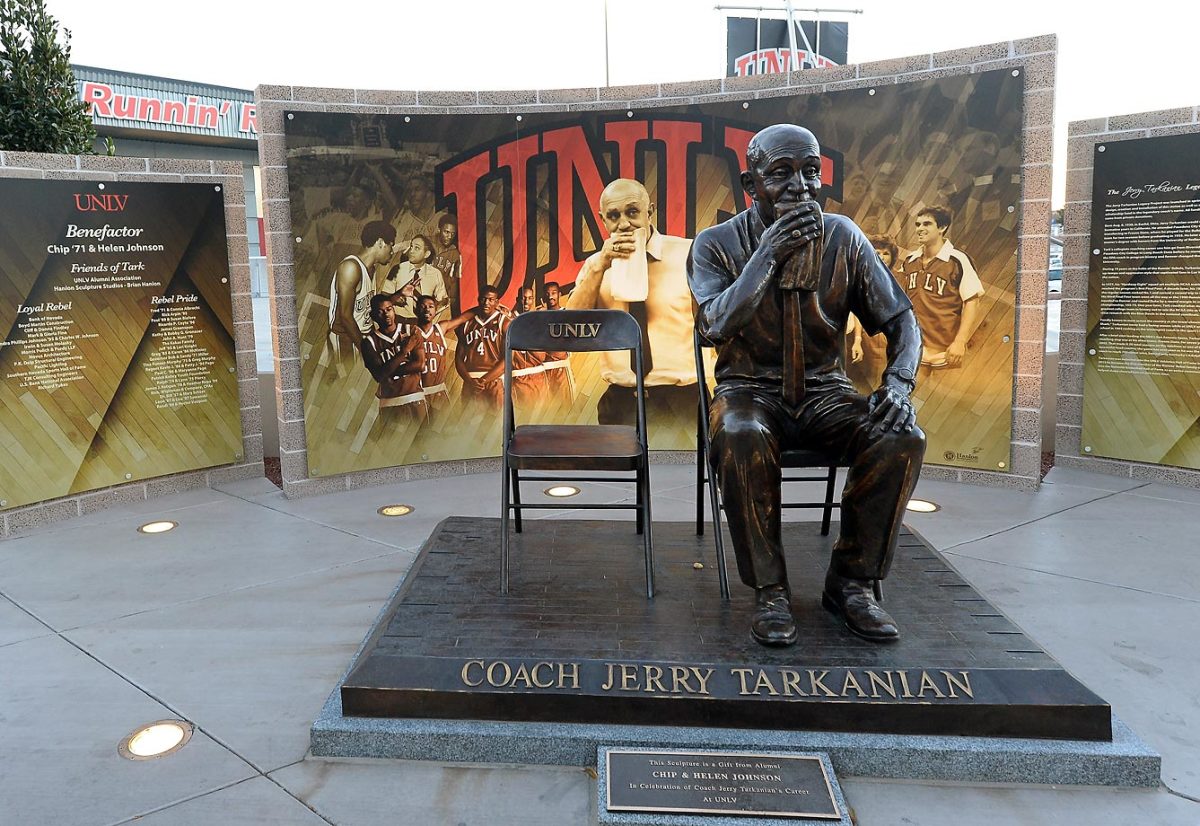

Encounters with Tark the Shark: Jerry Tarkanian in UNLV's glory days

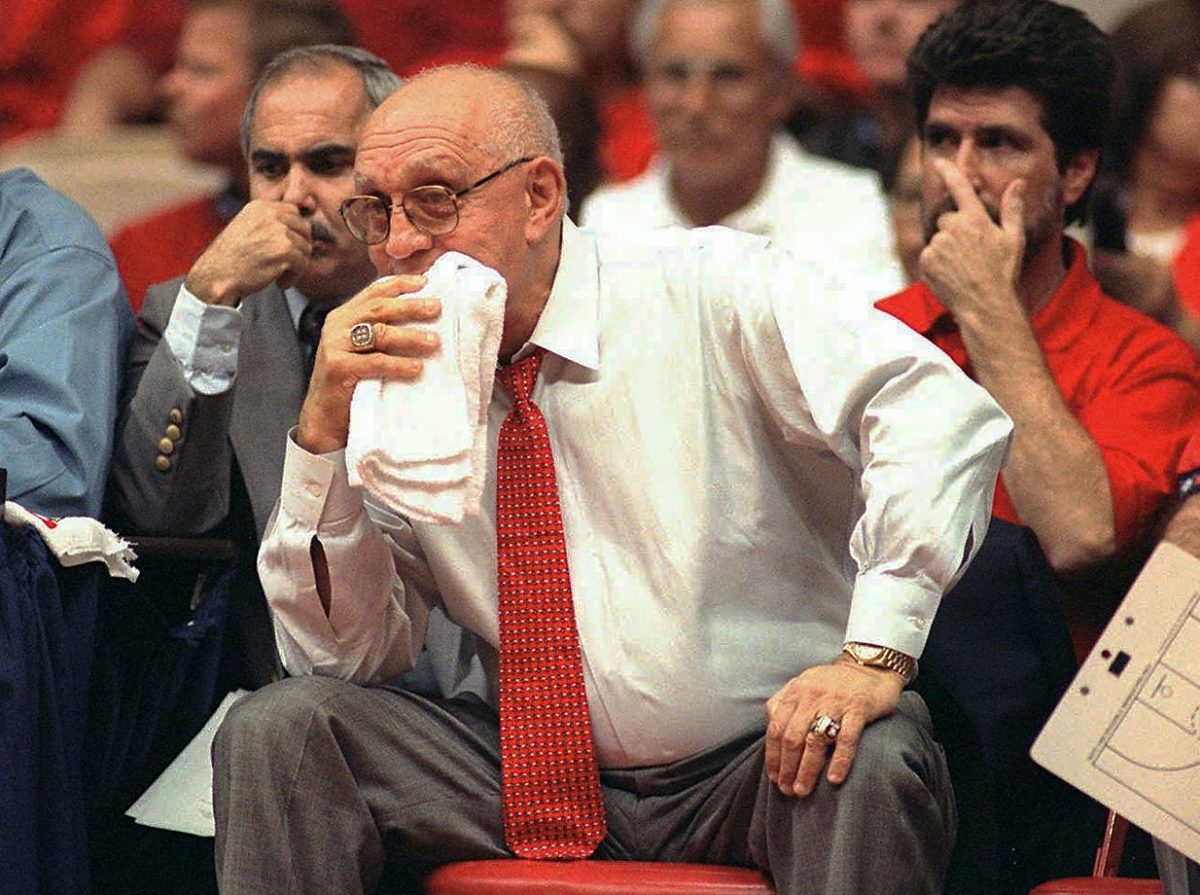

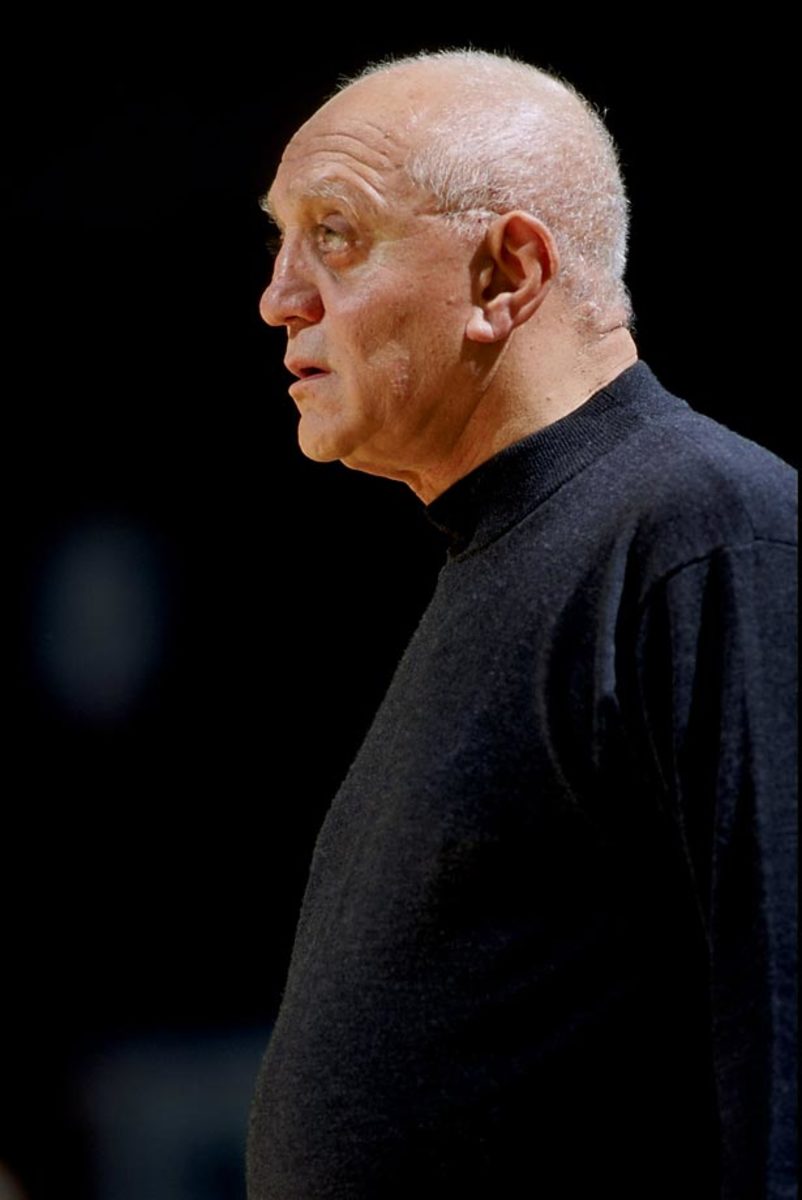

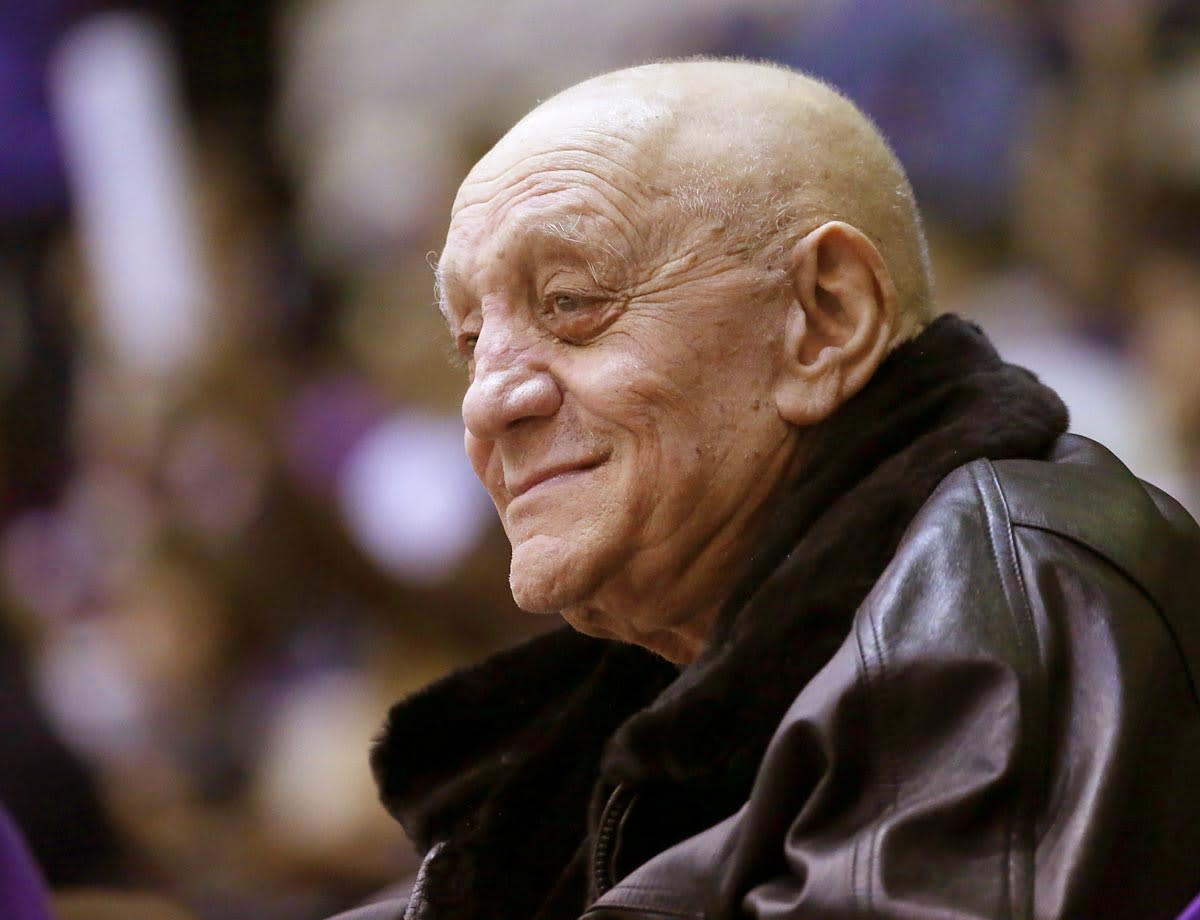

The news came Wednesday that Tark was gone, a basketball Rebel dead at 84. An image came to mind: A parking lot outside a practice gymnasium, faintly lit by tall streetlights rising from asphalt laid where once there had surely been sand and snakes and cactus. A 61-year-old man with a bald head, reaching the end of something. Or the beginning. With Jerry Tarkanian, it was always difficult to know for sure. This was the second-to-last of my many trips to Las Vegas for basketball purposes; the last would come a year later when former Villanova coach Rollie Massimino sat where Tarkanian had long ruled, a disconnect that was much less profound than one might have expected.

The first time I met Tarkanian was in 1990. As a reporter for Newsday, I had been assigned to cover the West Regional of the NCAA tournament in Oakland. Tarkanian already seemed larger than life. He had built a competitive program from nothing at Long Beach State, battled the NCAA and twice taken UNLV to the Final Four. But this time he brought a machine to the regional. The storyline was Loyola Marymount, playing in memory of the recently deceased Hank Gathers. Vegas ran them out of the building in the Elite Eight on a Sunday afternoon. My editor told me to go straight to Vegas and then to Denver for the Final Four, back when newspapers did that sort of thing.

Like any reporter, I fretted about access to the mighty Runnin’ Rebels. Silly me. In Vegas, I spent three days watching Tarkanian’s team practice as if meals would be withheld for any lack of effort, and then saw the entire team stay for individual drills that lasted into the evening. I interviewed Tarkanian until the batteries on my cassette tape recorder went dead, because Tarkanian just loved it when people showed up to watch his team practice, and he loved to tell stories about basketball and life in that raspy voice of his. Tarkanian was a full-service subject; he even recommended a hotel near the campus where, I’m convinced, he must have a gotten a cut of the action. I left the desert on a Thursday morning and four days later UNLV crushed Duke 103-73, giving Tarkanian his only national title.

Always A Rebel: Jerry Tarkanian was college sports' original honest man

Variations on this scenario repeated themselves over the next two years. Tarkanian and UNLV entered the 1991 NCAA tournament unbeaten before losing to the Blue Devils in the Final Four in Indianapolis. And all the while he was engaged in public spitting matches with not only the NCAA (he called it the "two-A") but also with UNLV President Robert Maxson, who spoke of elevating the educational profile of the university (and its president) while distancing it from the high-rollers who had turned Tarkanian into a wealthy Strip celebrity and the Thomas and Mack Arena into the hottest venue in the city. Once I came to town and interviewed Maxson for hours and Tarkanian for hours more (as he drove around the city, talking on any one of his half dozen "car phones"), then wrote a long story. On the day it was published I got a call from Tarkanian. "You son of a b----," he said, "You come out here and act like you’re our friend and then you go write this bulls--- from Maxson." I tried teaching a brief journalism lesson about fairness and two sides to any story, but you were either with Tark or against him. Yet, as with so many of his players, there would be second chances to talk, and third and fourth. The man could not stay angry.

Tarkanian’s UNLV career ended on the third night in March of 1992. By then, the world—and the NCAA—had seen a photograph of some of his players lounging in a hot tub with a man who had been convicted of point-shaving. There would be no postseason for Tarkanian’s last Rebels team. For that last game, we all came back to Vegas with our notebooks and old school laptops to see Tark cry on the floor of the Thomas and Mack while the crowd roared.

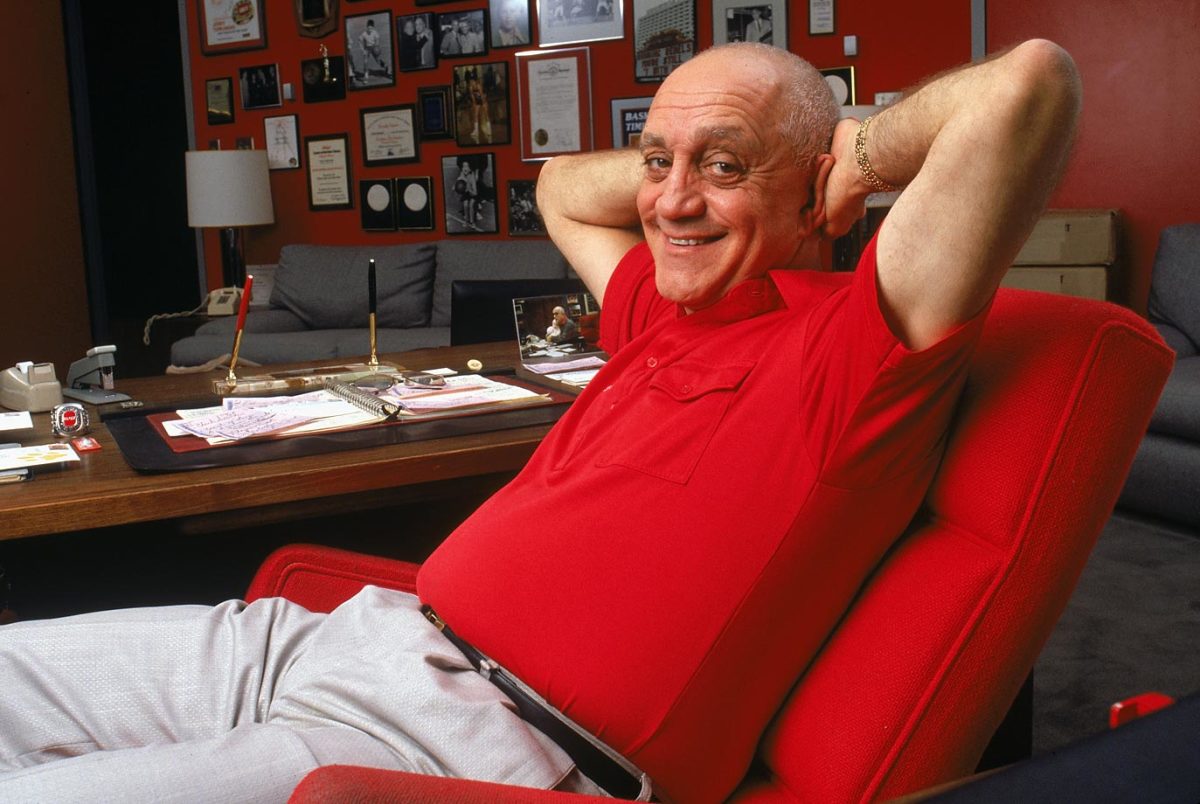

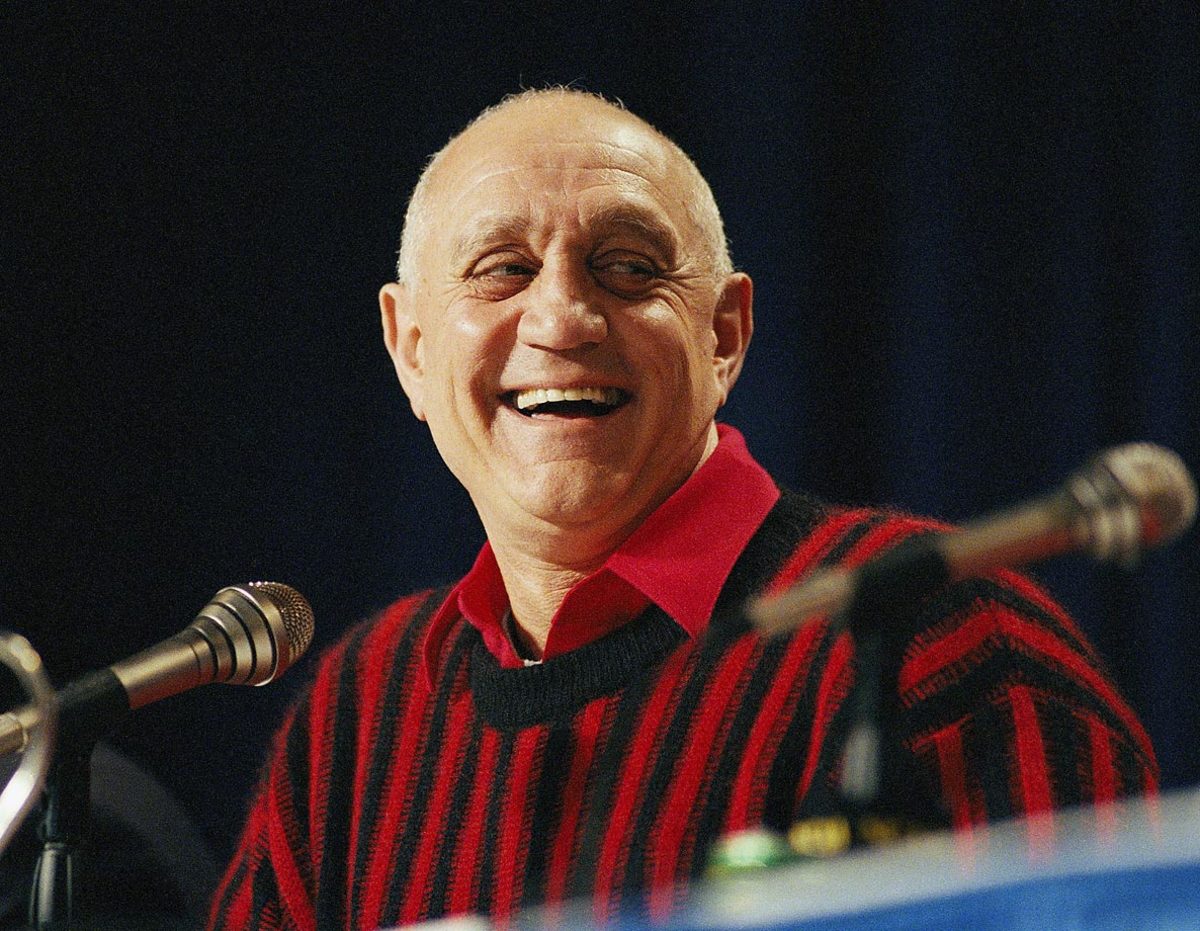

But that is not what I remember most. On the day before his final game as UNLV's coach, Tarkanian finished practice and then talked with the writers. At some point, the only two left were Malcolm Moran of The New York Times and me. The questioning fizzled out, the three of us walked toward the parking lot and then Tarkanian said, "You guys have any plans for dinner?" Here was the king of the Strip, looking to maybe grab a bowl of pasta with a couple of writers from out of town who were preparing to write a large portion of his professional epitaph the next night. But looking back, it makes sense. Tarkanian was a basketball junkie with a disdain for rules that impeded him. He was about the scoreboard, the money, the wins. He wasn’t larger than life at all. He was just life, lived exactly his own way.

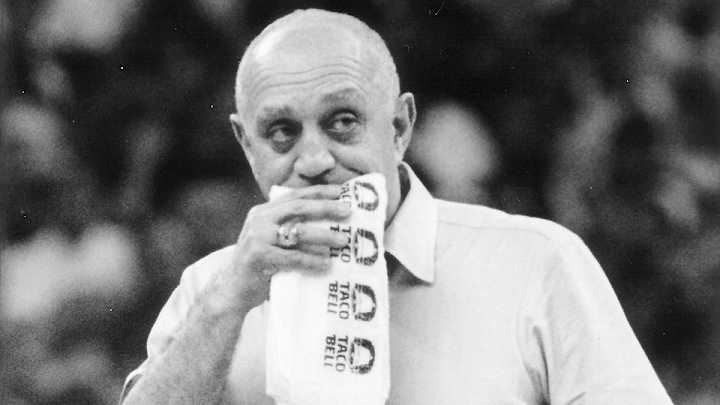

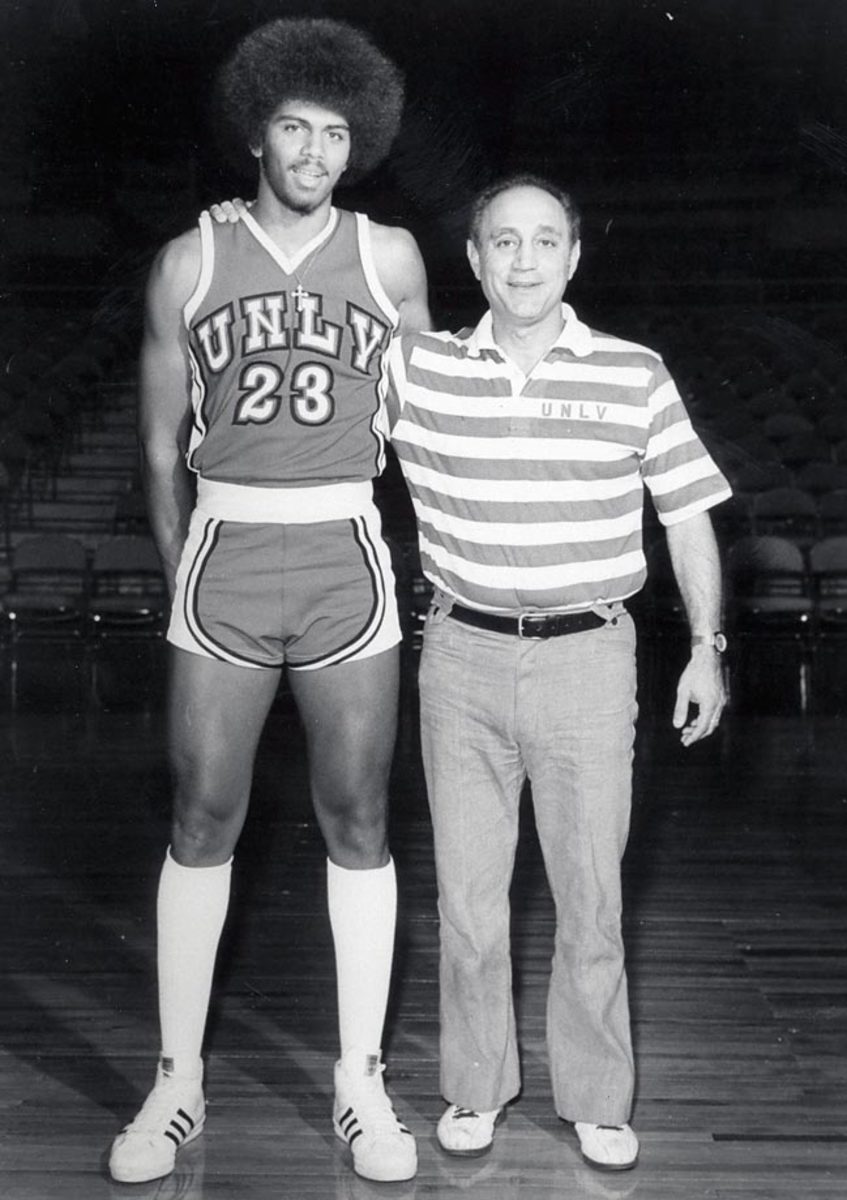

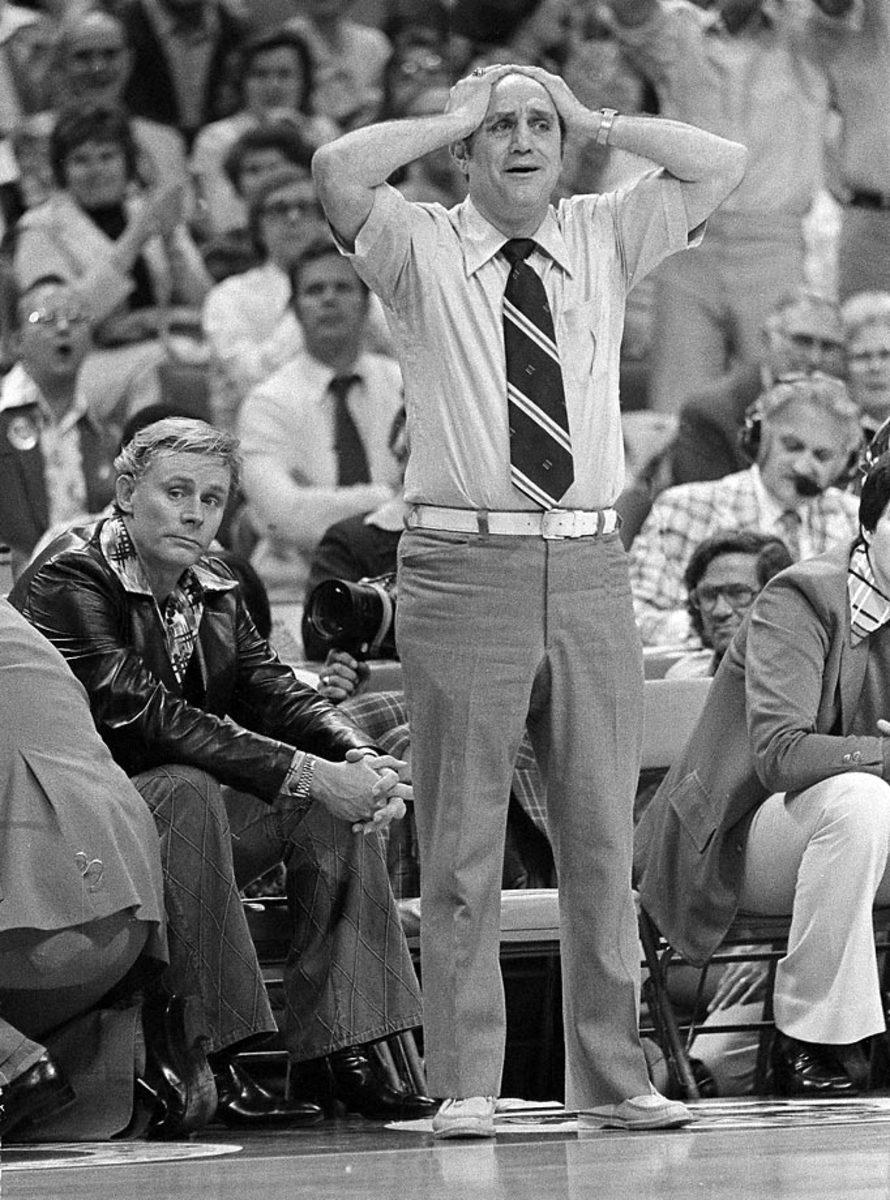

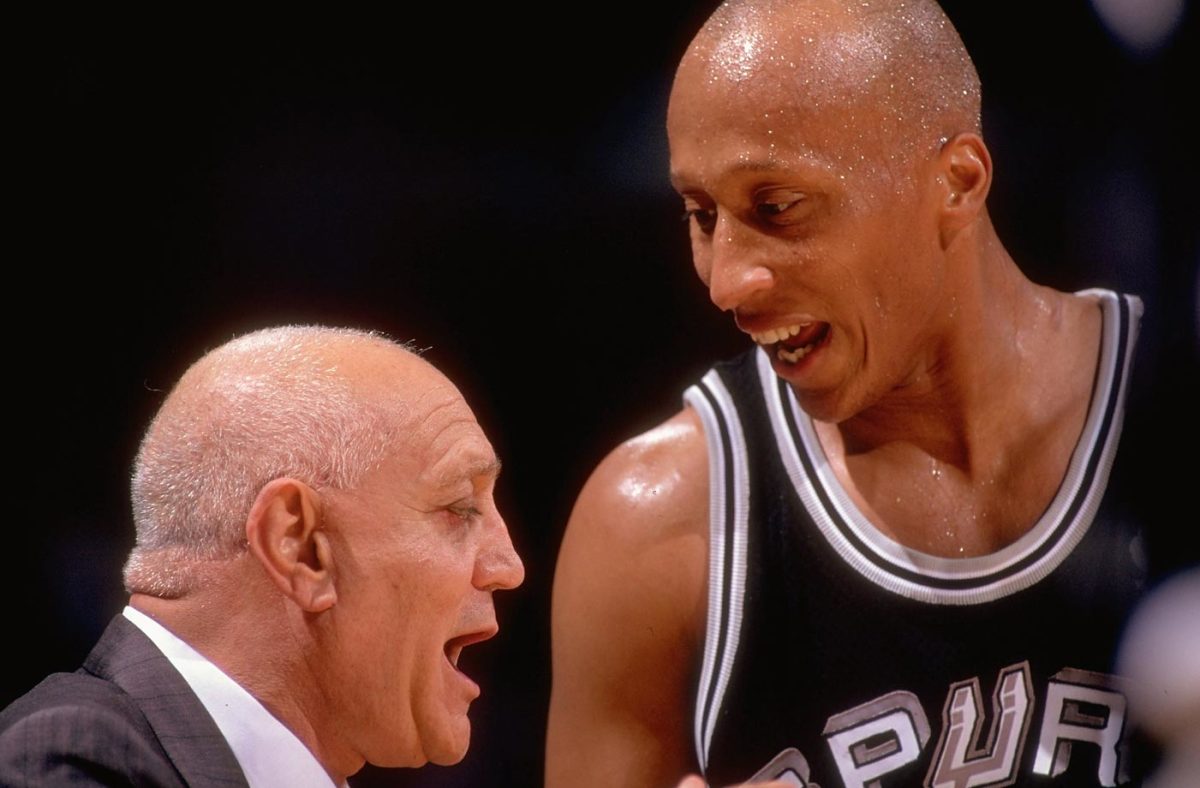

Jerry Tarkanian Tribute

1990

1970

1977

1985

1989

1989

1990

1990

1990

1991

1992

1995

1995

1996

1998

2008

2011

2012

2013

2015