Always A Rebel: Jerry Tarkanian was college sports' original honest man

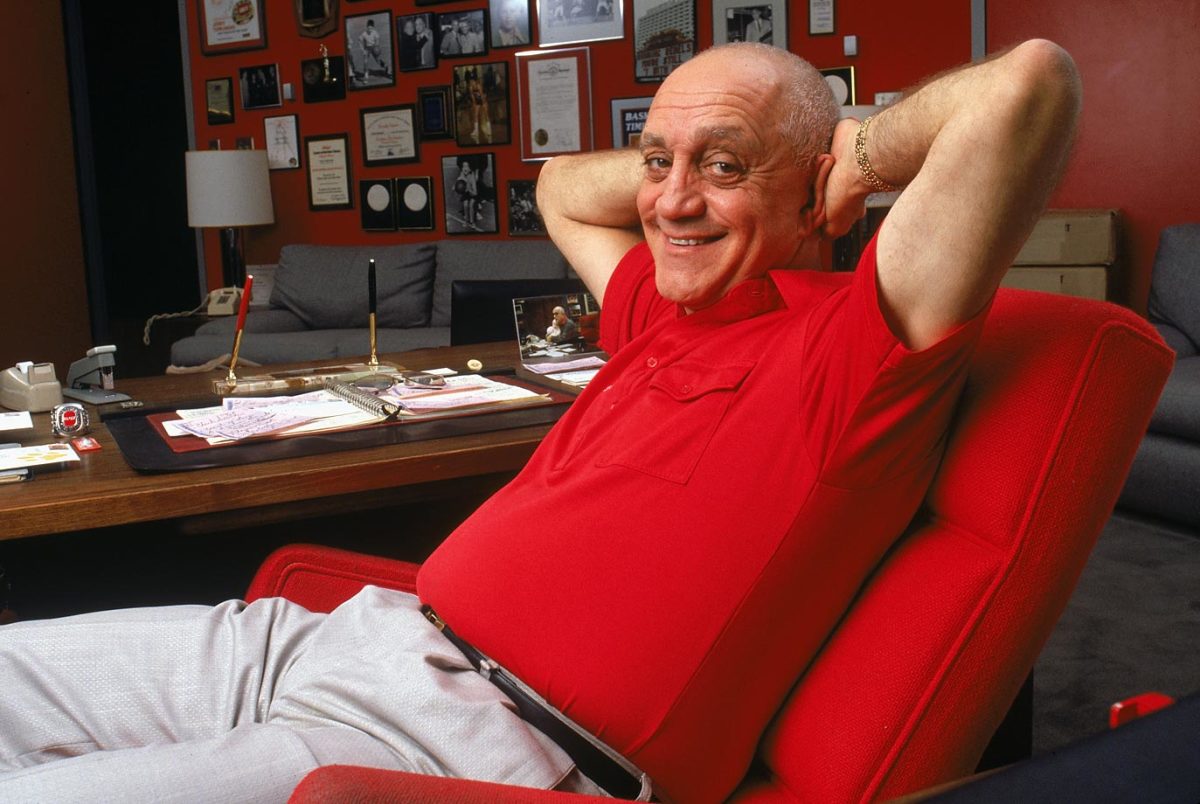

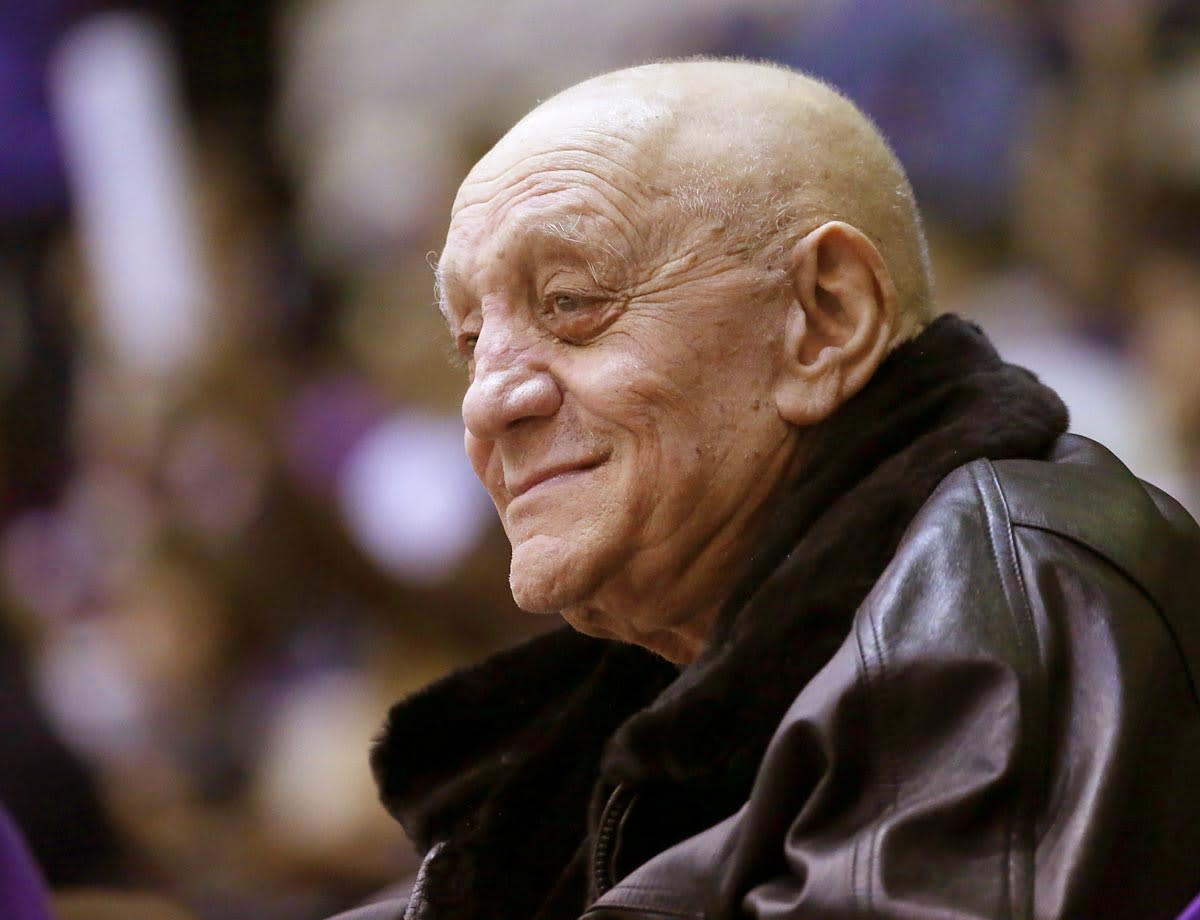

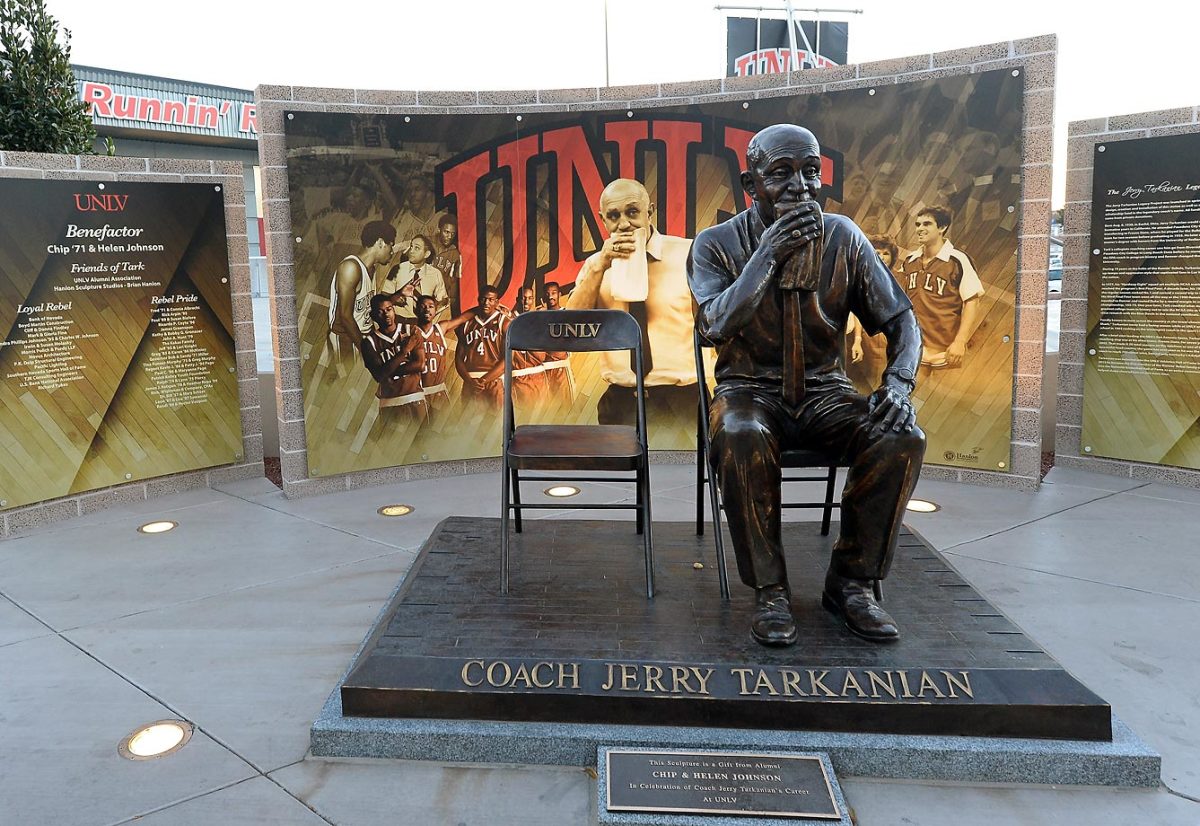

Jerry Tarkanian, who died Wednesday morning at age 84, coached three Division I schools to a total of 784 victories, and each—Long Beach State, UNLV, Fresno State—wound up on NCAA probation for violations committed on his watch. Yet with his death college sports has lost its original honest man.

Of a recruit who signed elsewhere, Tarkanian once said, “We got vanned.” And: “I love transfers because their cars are already paid for.” Watching others—better-connected, better-coiffed—get a pass from the NCAA’s enforcement staff, he refused to take part in the coaches’ mutual-protection racket. He pointed fingers and named names: e.g., Arizona and Lute Olson, or “Midnight Lute,” as he loved to say, cackling. He believed that the NCAA had it in for him because once, in a newspaper column, he suggested that the organization’s enforcement arm applied a double standard. When an overnight envelope from a Kentucky assistant coach to a recruit’s father came open in transit and cash spilled out, you could count on Tark for an epigraph. “The NCAA is so mad at Kentucky,” he said, “they’ll probably slap a few more years’ probation on Cleveland State.”

Ex-UNLV coach Jerry Tarkanian dies at age 84

Loyalists tried to peddle a storyline about the Father Flanagan of the desert, who just “gave kids a chance;” or about a blameless man persecuted by the Javerts of the NCAA, whose enforcement chief had indeed once called him a “rug merchant.” Tarkanian would protest his innocence, but always with such half-heartedness and world-weariness that you knew better. Once, when I was about to leave Las Vegas after reporting an anodyne piece about him and his point-guard son, Danny, Tarkanian promised me a hooker the next time I came through town. That kind of oafishness helps explain why he was forever on the lam. But when the NCAA clogs the airwaves next month with cloying PSAs about “student-athletes,” it will be hard not to miss Tark and his contempt for the veneer.

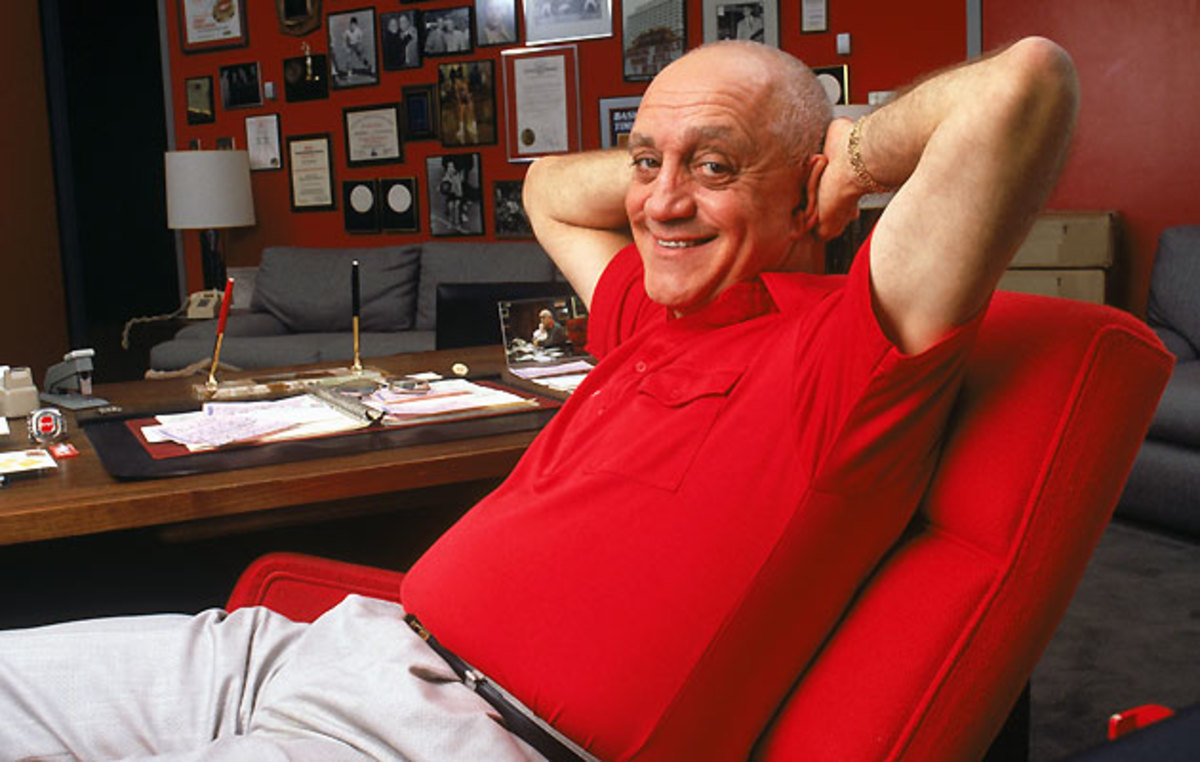

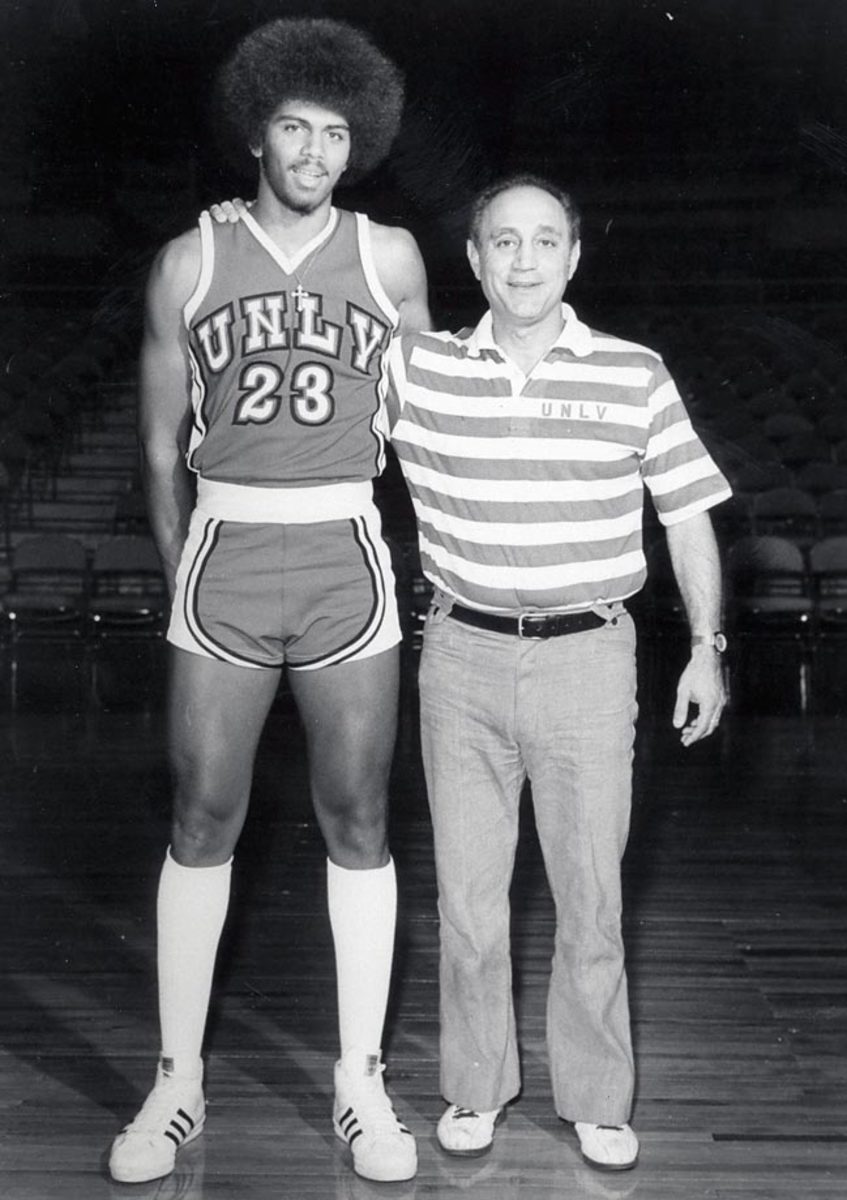

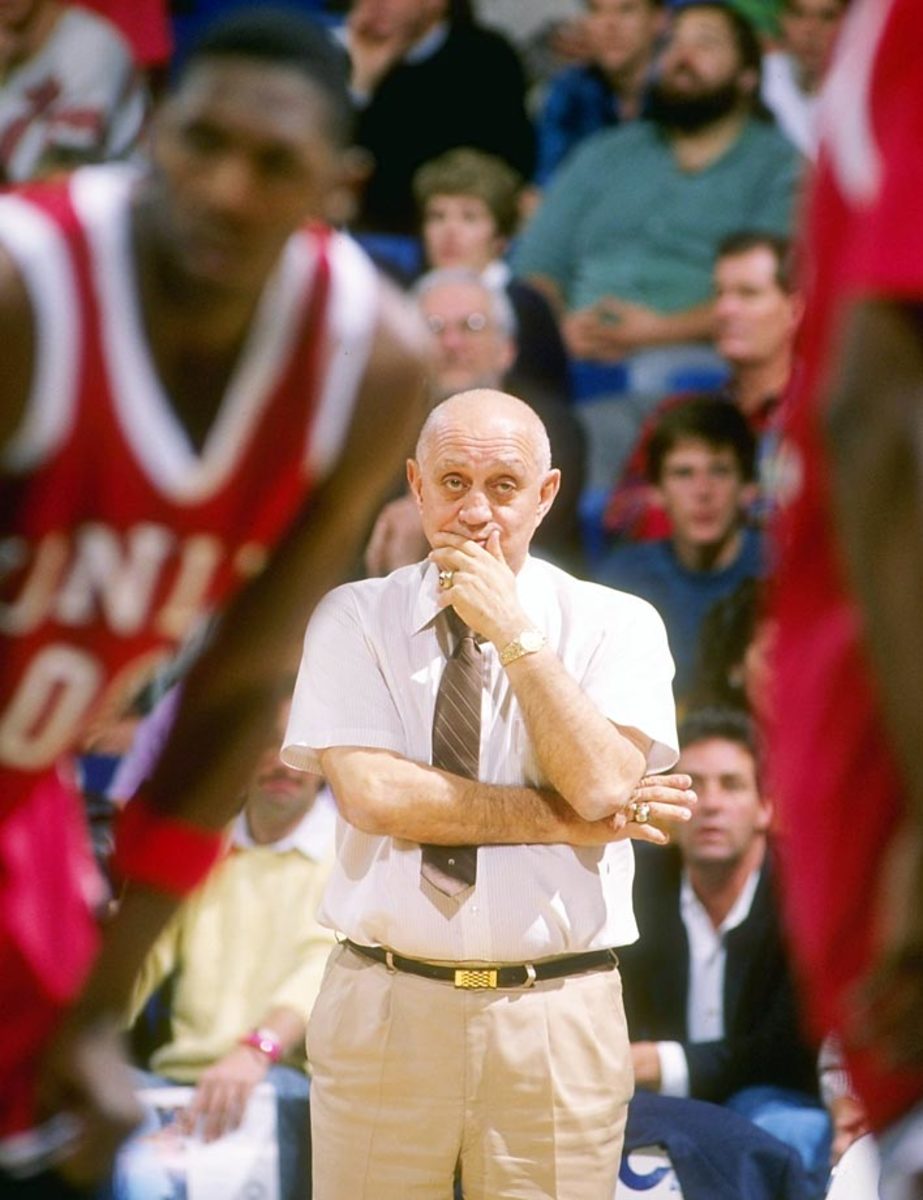

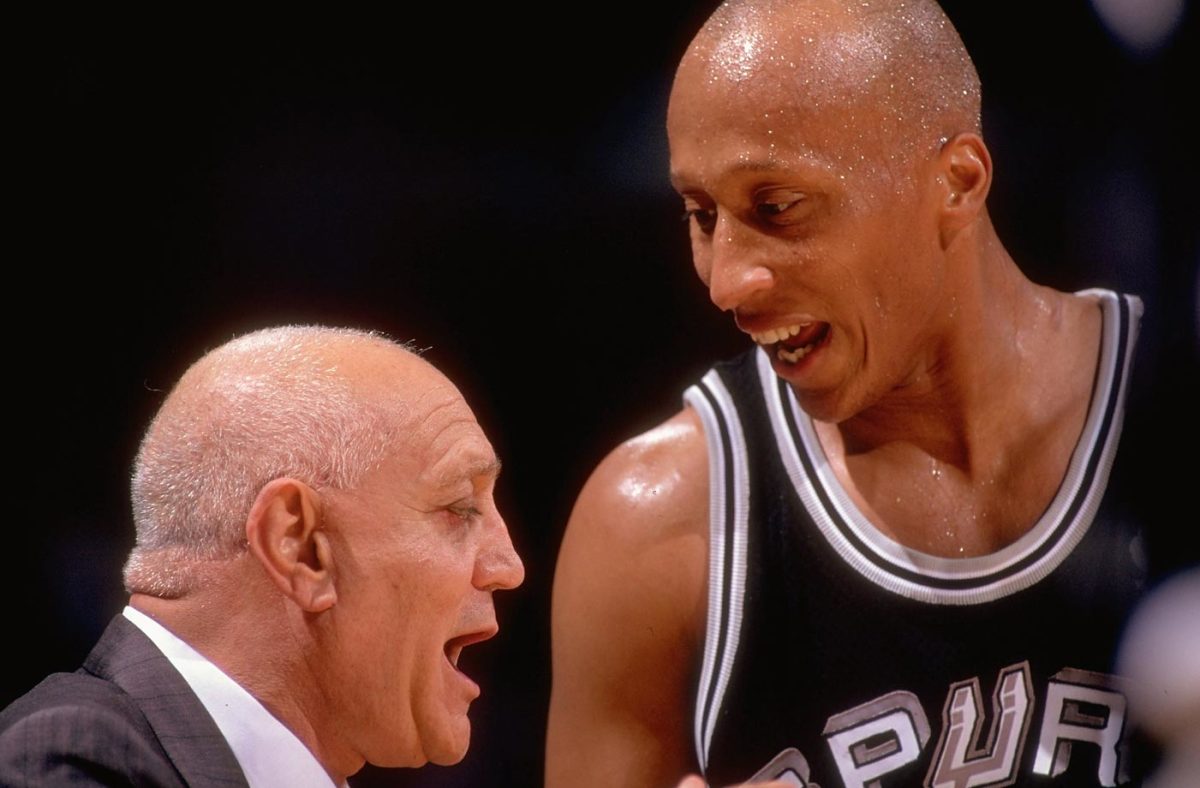

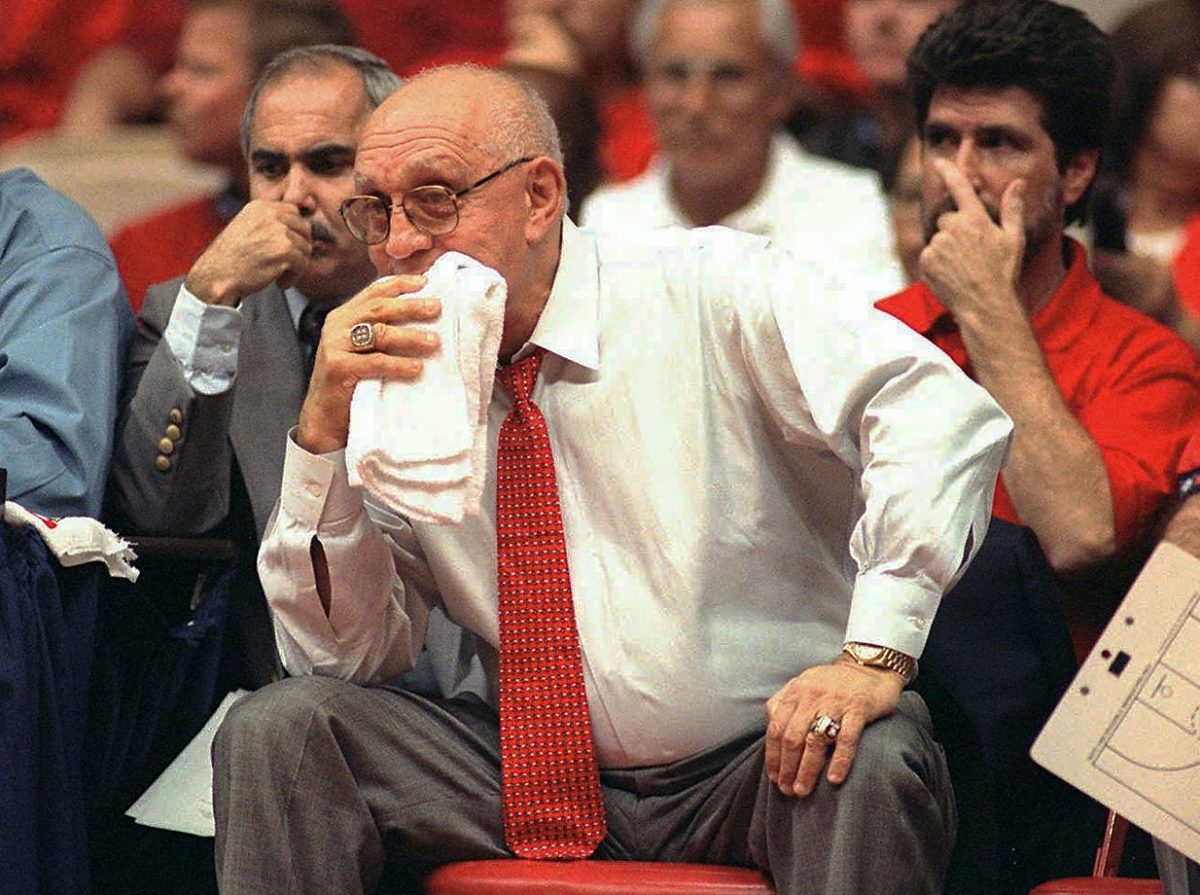

All the smoke from his battles with the NCAA—or “the Two-Ay,” as he and his allies called it—obscured his basketball virtues. He refused to hire assistants who played golf, believing that a coach’s dedication to the game should be year-round and unalloyed. He made a fetish of defense even when fielding his most offensively gifted teams. He met the test that coaches have for one another by winning big with radically different kinds of talent—playing walk-it-up at Long Beach State for five seasons; then up-tempo with the original Runnin’ Rebels of Reggie Theus, Eddie Owens and Glen Gondrezick; then balancing the two with his greatest teams, the Larry Johnson-Stacey Augmon crew of the early Nineties, which thumped Duke by 30 in the 1990 NCAA title game.

Vaunted as those UNLV teams were, insiders knew the truth: High-school All-Americas chose to go elsewhere. Instead, the cosmic croupiers pushed his way juco transfers and reclamation projects—guys whose fortunes as a team depended largely on Tark’s feel for the table and the roll of the dice. (Yes, the 1991 team that lost to Duke at the Final Four had been unbeaten, but the narrative that Blue Devils Christian Laettner, Bobby Hurley and Grant Hill played for anything remotely close to an underdog remains absurd.) The city, the program’s last-chance-saloon reputation, even the towel Tark teethed on, all contributed to a mystique that made the Rebels seem more imposing, more inevitable, than they ever were.

If some playground prodigy were to be delivered from the snares of the ghetto, Las Vegas would be his refuge. The Shark raved to anyone who would listen about the gifts of a New York street player named Lloyd Daniels. A high-school dropout, Daniels had no business going to college, of course. Tarkanian brought him to Vegas anyway, of course. The man who pursued him was—of course—ultimately as star-crossed as Daniels, who had to be sent back East after getting caught trying to buy crack cocaine.

Daniels’ patron was a gambler, with two convictions for sports bribery, known as Richie (The Fixer) Perry. He would show up in a photo, with three of Tark’s players in a hot tub, that hastened the decision of UNLV president Robert Maxson to chase Tarkanian from the Runnin’ Rebels’ sideline. The two were made for each other, Lloyd Daniels and Jerry Tarkanian, a tragic-hero player for a tragic-hero coach.

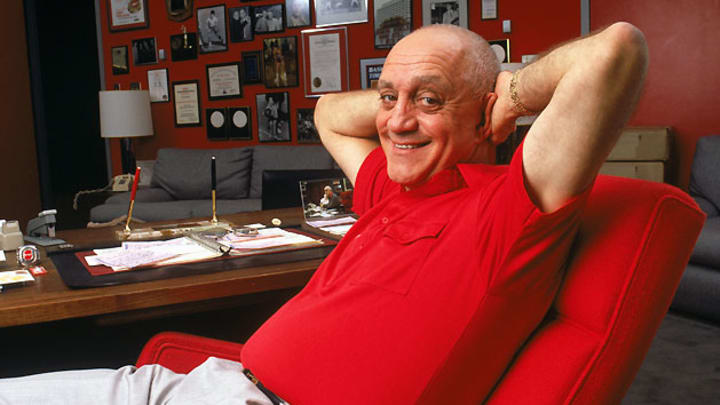

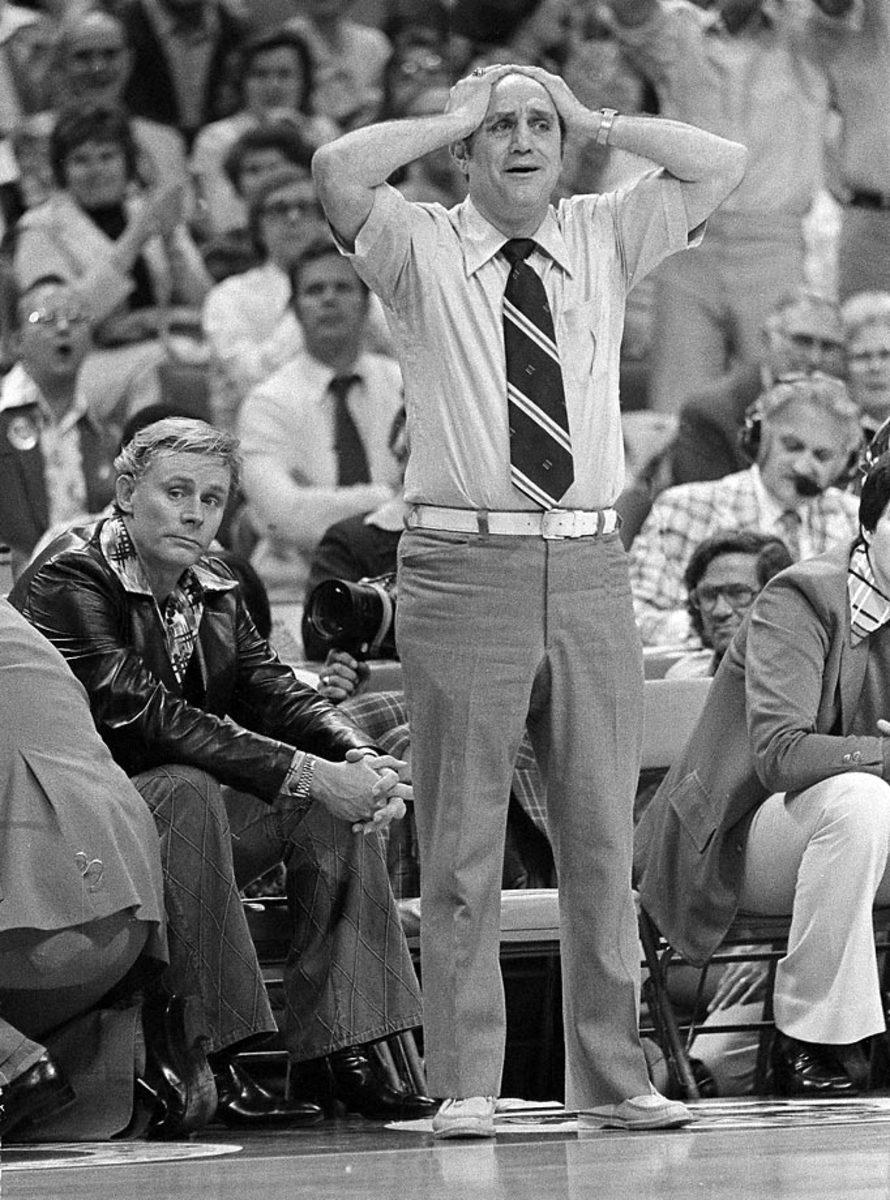

SI Vault: After retiring from coaching, Jerry Tarkanian never left Las Vegas

Hang around college basketball long enough and it’s impossible not to develop a bicameral mind, where you can sort the virtues of the game from the vices of those who make a business of it. The suits and hustlers who pillage the sport for personal gain get compartmentalized into one chamber. The game itself, by contrast, sits in the other, and gets the run of the cranium come tournament time. That’s when passion, devotion, and those concepts appropriated by shoe companies for their advertising, “respect” and “love,” can win even a cynic over.

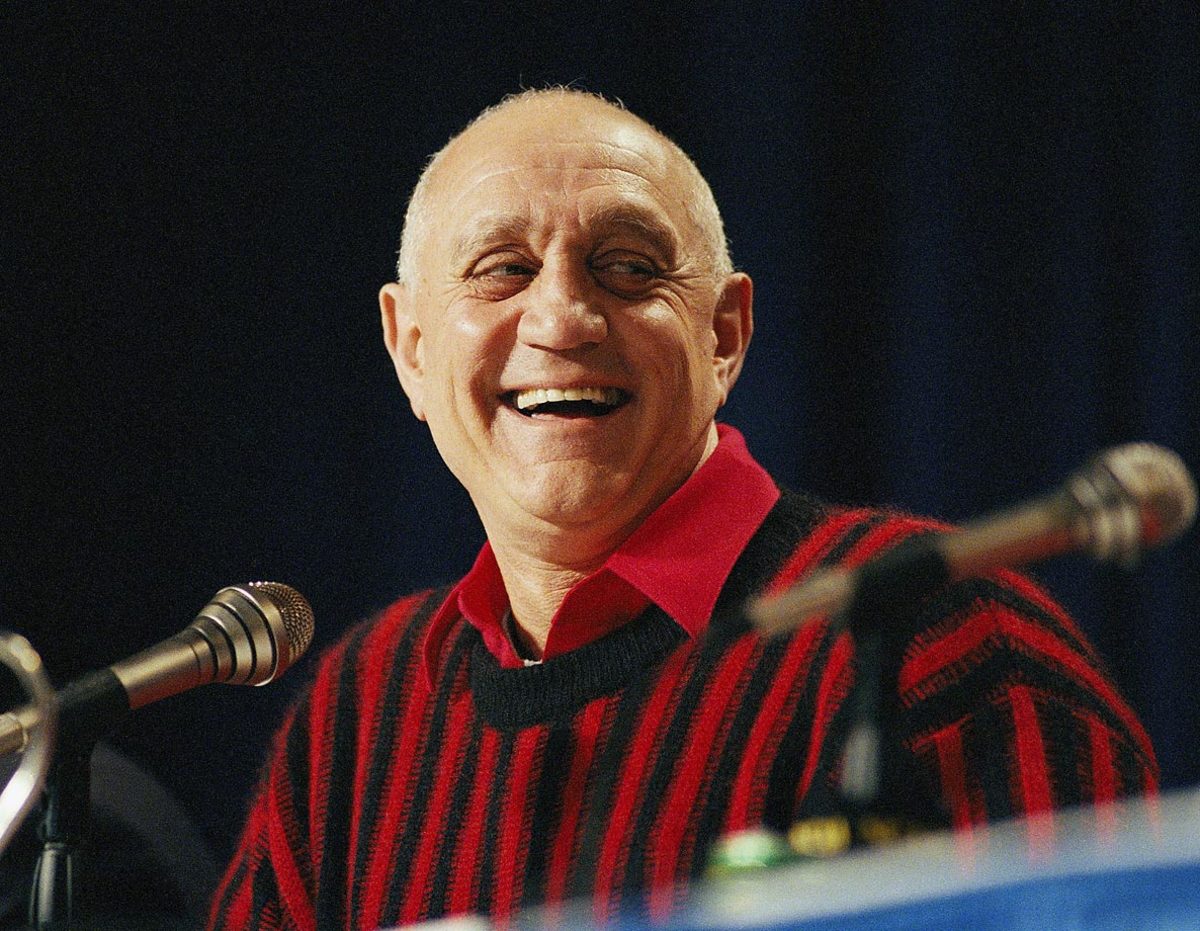

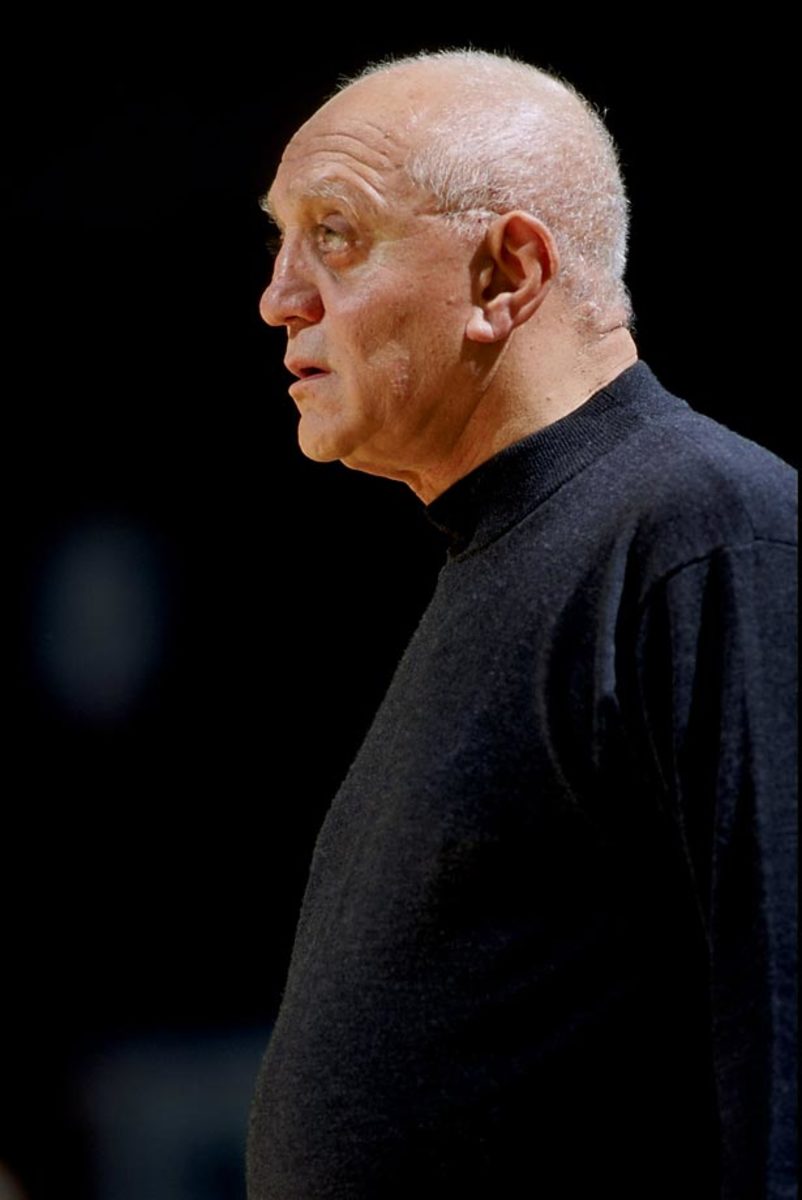

Tark had a place on both sides of the basketball brain. But in the aftermath of his death, I’ll return often to moments I witnessed of a man dedicated to the game in all its purity—the man I once watched fall into a long and detailed discussion with Hall of Famer Pete Newell about a prospect’s footwork in the post; who, eager to supply a corrective to some visiting reporter’s East Coast bias, patiently explained the world of Bud Presley and Snow Valley, West Coast equivalents of Howard Garfinkel and Five-Star; and who once described Daniels to me with the appreciation of the aesthete as he said, almost achingly, “He throws the softest pass ...”

Tarkanian spent most of his professional life as a poster boy for disreputability. Today, with the NCAA itself in broad disrepute, it’s almost as if he lived just long enough for public opinion to catch up to him. There would be much worse things than if, in death, Tarkanian were to earn something like vindication.

It’s easy to believe that the sport was meant to wear Armani. Jerry Tarkanian, armed with little more than terrycloth, served as a reminder that, in fact, the empire has no clothes.

Jerry Tarkanian Tribute

1990

1970

1977

1985

1989

1989

1990

1990

1990

1991

1992

1995

1995

1996

1998

2008

2011

2012

2013

2015