The King Of Philadelphia: How Herb Magee reached 1,000 wins

On Jan. 25, Duke’s Mike Krzyzewski became the first NCAA men’s basketball coach to win 1,000 career games. He did it in “The World’s Most Famous Arena” while millions watched on national television. After the final horn sounded, he was encircled by a swarm of well-wishers and media members so large it could only be fully appreciated from an aerial view. After the game, Duke athletic director Kevin White deemed the accomplishment one of the great moments in the history of sport.

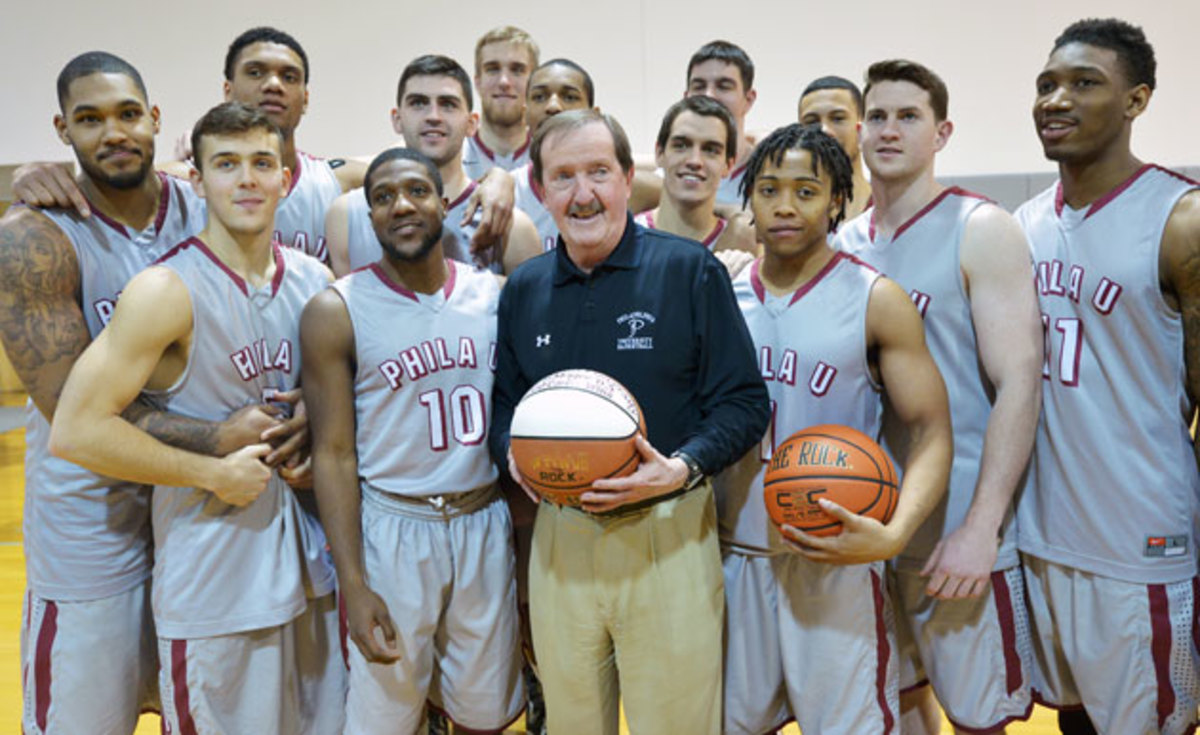

On Feb. 7, Philadelphia University’s Herb Magee became the second NCAA men’s college basketball coach to win 1,000 career games. He did it at a 1,200-seat gym on the campus of the only professional place he’s ever known. The sole televised broadcast was a shaky Internet live stream. After the game, he went to the Great American Pub in Conshohocken, Pa., and had a beer with some friends. He was in bed by 10 p.m.

*****

“D-n-a-s-o-u-h-t, a. Dena-SUE-eht-ah.”

The syllables shoot effortlessly off Magee’s tongue as he spells and pronounces the words ‘a thousand’ backward.

How did Mike Krzyzewski reach 1,000 wins? With a million small steps

“My friends used to tell me I’m dyslexic, but I don’t know what that means,” he says in a way that leaves you wondering whether he’s joking.

The “Mr. Backwards” routine, which Magee taught himself as a high school freshman after seeing it performed on the Ed Sullivan Show, is one of the many things Magee can do that others cannot.

“I’ve known a lot of people over my years, and everybody has a special uniqueness,” says Jim Lynam, one of Magee’s closest friends and a former NBA coach who is now a commentator on 76ers broadcasts. “But I’m telling you this guy is different.”

Indeed, Magee is different. Now 73, he has spent 56 years, 48 of them as head coach, at the same Division II school on a 100-acre campus in Philadelphia’s East Falls neighborhood. He has eschewed multiple opportunities to go elsewhere, instead preferring to remain enshrouded in comforts of his own choosing: the familiarity of the school he once played at, the dearth of invasive media attention and the proximity of family and friends.

If it seems like Magee, an eminently straightforward creature of habit, doesn’t necessarily want you to know about him, it’s because he doesn’t. He’d rather let his 71.8 career win percentage, 27 NCAA Division II tournament appearances and one national championship speak for themselves. “Can’t you just do it?” he’ll half-jokingly ask his daughter, Kay, the director of basketball operations, when pressed to do more interviews on the eve of his impending milestone.

Magee grew up in a brick, porchfront row house at 45th and Baltimore in rough, middle-class, 1950s West Philadelphia. When he was 12 his mother died of kidney disease and his father passed away after having a stroke. He and his three orphaned brothers were then raised by his uncle Edwin Gallagher, the chaplain of the Eastern State Penitentiary.

Magee played basketball at West Catholic High School, where he developed a reputation as a prolific long-range shooter long before the days of the three-point line. He was known on the playgrounds as ‘The Flying Squirrel’ for his 5'10" stature and his running and jumping ability. Magee taught himself how to shoot by watching the mechanics of Hall Of Famers Paul Arizin, Tom Gola and Wilt Chamberlain, whom he saw when he hopped the fence in to Philadelphia Warriors games at Convention Hall with his friends.

“If we didn’t have enough money we’d figure out a way to get one guy into the game and he would go around and open up a side door,” he says.

His study of shooting soon became an obsession. He would take hundreds of jump shots outside of practice and chart which part of the cylinder he missed on.

Former St. Joseph’s head coach Jack Ramsay came to West Catholic games to recruit Lynam, but he noticed Magee too. By then, the Flying Squirrel had become known simply as “The King” to teammate Lynam’s “The Kid.”

Ramsay did not offer Magee a scholarship, a decision he later said he wished he could go back and undo. The two eventually became lifelong friends, although Ramsay, who died in 2014, had to endure the brunt of Magee’s ribbing. “Worst mistake you ever made, Jack, not taking The King,” Magee would tell him.

In 1959, Magee headed 20 minutes north to play at the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Sciences, a school whose legacy in fabric restoration included repairing Betsy Ross’ first American flag. The “Fabric Five” played in a gym that sat 700 people and had a stage under a basket on one end with a drawn curtain.

Magee graduated four years later as a two-time All-America and the Weavers’ (yes, really) all-time leading scorer with 2,235 points, a record since broken with the advent of the three-point line. He averaged 24 points per game and shot 50 percent from the field in his collegiate career.

“He was a really good shooter. And occasionally he would think about playing some defense,” says Temple head coach Fran Dunphy, who played with and against Magee during the summers. “But those were the rarer cases.”

In the summer of 1963 the Boston Celtics, which had won six of the last seven NBA titles and would go on to win five more by the end of the decade, chose Magee with the 62nd pick in the NBA draft.

“I was flabbergasted,” he says. “The number of guys that weren’t picked and I was picked? So I thought, let me take a look. Bob Cousy and Bill Sharman. Sam Jones, K.C. Jones. John Havlicek. Now, I really did think I was a good player. I could shoot. But those five guys are in the Hall of Fame ...”

Well, sure. But so is Magee.

“As players,” he finishes.

Mt. Rushmore: How does Krzyzewski compare to Knight, Smith, Wooden?

Just being drafted did not ensure a roster spot in those days, however. NBA teams selected between six and 12 players each year, far more than could simultaneously make the roster, and held training camp every fall as a de facto tryout for the new players. None of Boston’s six draftees in 1963 made the team.

Magee didn’t even attend the tryout, though he insists he would have had he not broken the middle and ring fingers on his shooting hand that summer, which hindered his greatest asset: his shooting ability.

Besides, as Lynam notes, “The NBA wasn’t glamorized then the way it is today. He had a comfort zone at Textile.”

Magee returned to that comfort zone, starting in the fall of ‘63 as an assistant under his former coach, Bucky Harris, making the same amount of money ($5,000) he would have made as a rookie with the Celtics. But the gig had a catch: In addition to his basketball duties, he also had to coach cross-country, tennis, intramurals and his other favorite sport, golf.

He took over the head basketball coaching position in 1967. Within three seasons, Magee had led Textile to an NCAA College Division national championship.

In his office, there is a pile of laminated Western Union telegrams sent to him after the national championship. One of them reads, “I share your admiration for [your players’] skill in the game, as well as for the sense of fair play and good sportsmanship which make them particularly deserving of this victory.”

It is signed at the bottom, ‘President Richard Nixon.’

*****

As Magee approached win 1,000 in early February, the only sign on Philadelphia University’s campus of an impending major college athletics milestone was an actual sign, a small white board easel outside the entrance to the Gallagher Athletic Center. The words ‘1 more win to 1000!’ and the Twitter hashtag #Magee1000 written out in purple dry-erase marker have withstood the morning’s wind and rain.

Inside, the gym simultaneously hosted P.E. drills, Rams basketball players shooting jump shots and a pitcher throwing long toss to a catcher in full pads. In an office off to the side of ‘Herb Magee Court,’ Tom Shirley, the school’s athletic director and women’s basketball coach, outlined the plan for when Magee reaches the milestone. The school normally presents him with a commemorative ball at half court after the game, Shirley explains. It’s a professional way of saying Magee has hit so many milestones lately—like win number 829 in 2007 to pass Winston-Salem State’s Clarence Gaines and become the all-time winningest coach in Division II, or win number 903 in 2010 to surpass Bobby Knight and temporarily become the winningest men’s coach across all NCAA levels—that there’s an established in-house protocol for celebrating them.

Most of his milestone wins have passed without much notice, but this time is different. Though Magee is, in the words of former player and Penn State coach Pat Chambers, someone who “has mastered, in a positive way, the word ‘no,’” he has lately found himself saying “yes” a lot. He’s done interviews with CBS Sports, Comcast Sports Net and a horde of local broadcast television affiliates.

He's growing tired of responding to repeated batteries of the same questions: How did you do it, Herb? Why did you never leave Philly U? What does 1,000 wins mean for the program? A few days earlier, doing his best Yogi Berra impersonation to the Philadelphia Daily News, he opined, “You don’t get that many wins if you’re concentrating on how many wins you have.”

Coach K enjoys moment of win No. 1,000 with family, team

Incessant media obligations aren’t just unusual for Magee. They disrupt the simplicity that is so fundamental to his daily routine. He’s often awake well before dawn, and his five-mile run or his weight training—his trainer refers to him as 'Herbatron'—is over by 8 a.m. He eats lunch around 11:30 a.m., usually a small sandwich or a salad. During the afternoons he’ll hold practice, study film, or go over game plans with his assistants. Geri, his second wife, is usually home by 6:30, and the two eat Italian for dinner. He’s in bed by 9 p.m.

Just outside Gallagher’s ‘Herb Magee Court’ is something that speaks louder than any interview sound bite anyway: the Herb Magee trophy case, which holds more than 75 different items dedicated to Magee and his teams. There’s plenty more where that came from.

“Thank God we have a large basement,” says Geri, referring to their home, where they also have a piece of West Catholic’s old gym floor.

There are still more mementos in Magee’s office, where a large plastic bin holds thousands of jaundiced newspaper and magazine clippings. There’s a program from the 1969 NCAA College Division Mid-Atlantic Regional tournament in Ashland, Ohio. There’s an Italian sports magazine from 1975 with an article in English headlined, ‘Herb Magee Ranks #1 Among College Division Coaches.’ And there are dozens of local news articles that share the same simple, sustained success story, often accompanied by a familiar picture: a coach standing at mid-court, his arms around his family, a plain-mouthed stare covered by a trademark mustache belying the satisfaction of continued, quiet success.

*****

One day in the summer of 1982, Magee strode wordlessly into the gym at Cardinal O’Hara High School in Springfield, Pa., past an assembled group of elementary school basketball campers seated at mid-court, and started shooting. He was the camp’s featured guest speaker (or rather, guest shooter), and he addressed the campers on the mechanics of shooting without ever making eye contact with them.

“The whole time he spoke he was shooting jump shots right around the free-throw line area back around to maybe the top of the key, and for 45 minutes he didn’t miss one shot,” says Ed Malloy, one of Magee’s former players and now an NBA referee. “I don’t remember what he was saying. I just remember watching [and thinking], Is this guy ever going to miss?”

Magee quickly became a legend on the camp circuit for his shooting ability, routinely making 50, 75 or even 100 shots in a row. Villanova coach Jay Wright, who has since hired two of Magee’s former assistants for his own staff, was a ninth-grader at a camp in the Poconos when he first witnessed Magee’s can’t-miss routine.

“He defined the basic fundamentals and simplified them,” says Wright. “That’s what geniuses do. We work on shooting every day, and everything I learned I learned from him.”

The speaking appearances helped Magee supplement his income and form lifelong relationships. After a day of camp sessions, Magee would sit with other coaches and diagram offensive sets with empty Miller Lite bottles on diner tabletops.

By the late 1980s, Magee was getting asked to coach young NBA players, like Charles Barkley, on their shooting. Lynam, then an assistant with the 76ers, arrived one day at practice to see Magee imploring a young Barkley to follow through with his shooting hand. Afterward, he asked Magee how Barkley was progressing.

Magee liked Barkley, but told Lynam the power forward would never be a great shooter. To be a great shooter, Magee said, you have to try to make every shot. Barkley—who would go on to be one of the top rebounders in NBA history—didn’t try as hard to make shots because he knew he was going get the rebound anyway and dunk it.

Lynam would eventually become Barkley’s head coach in Philadelphia. His old friend The King had opportunities to reach to the sport’s highest level as well, but Magee turned down offers in the 1980s and 90s to be an assistant with the NBA’s San Diego Clippers and Washington Bullets, respectively. Why uproot his family, his lifestyle, his comfort, Magee thought, when he had everything he needed at Textile?

The Deep Blue D: Is Kentucky's defense the best of the modern era?

Still, Magee’s reputation as a coach was becoming widely known. In 1995, four years before Textile changed its name to Philadelphia University, then-UMass coach John Calipari tapped Magee to be an assistant for one of the U.S. teams at the U.S. Olympic Festival, a multi-sport competition put on by the International Olympic Committee. Calipari introduced the young men before him to his assistant. “This is Herb Magee. He coaches in Philadelphia, and some day he’s going to be in the Hall of Fame.”

Calipari’s prognostication came true. Sixteen years later, with 922 wins under his belt, Magee was inducted into the Naismith Hall of Fame. His presenter was that old mentor who never recruited him: Dr. Jack Ramsay.

Magee had come a long way since doing shooting demonstrations for kids like Wright, who is now a friend who vacations near Magee every summer on the Jersey Shore, and Malloy, who still remembers vividly how Magee ended the shooting demonstration that day at Cardinal O’Hara.

“At mid-court, he throws the ball up through the rafters—40 feet, 50 feet in the air—it bounces once in the middle of the lane, and hits nothing but net,” recalls Malloy.

“And then he just walked right off the court.”

*****

Eight hours before tip off against Wilmington on Feb. 3, Magee arrives at Gallagher with Jimmy Reilly, the only paid assistant coach on his staff, at his side. The two men break down film in a room off the main entrance marked “Classroom 102” that also doubles as a post-game team meeting area and press conference center.

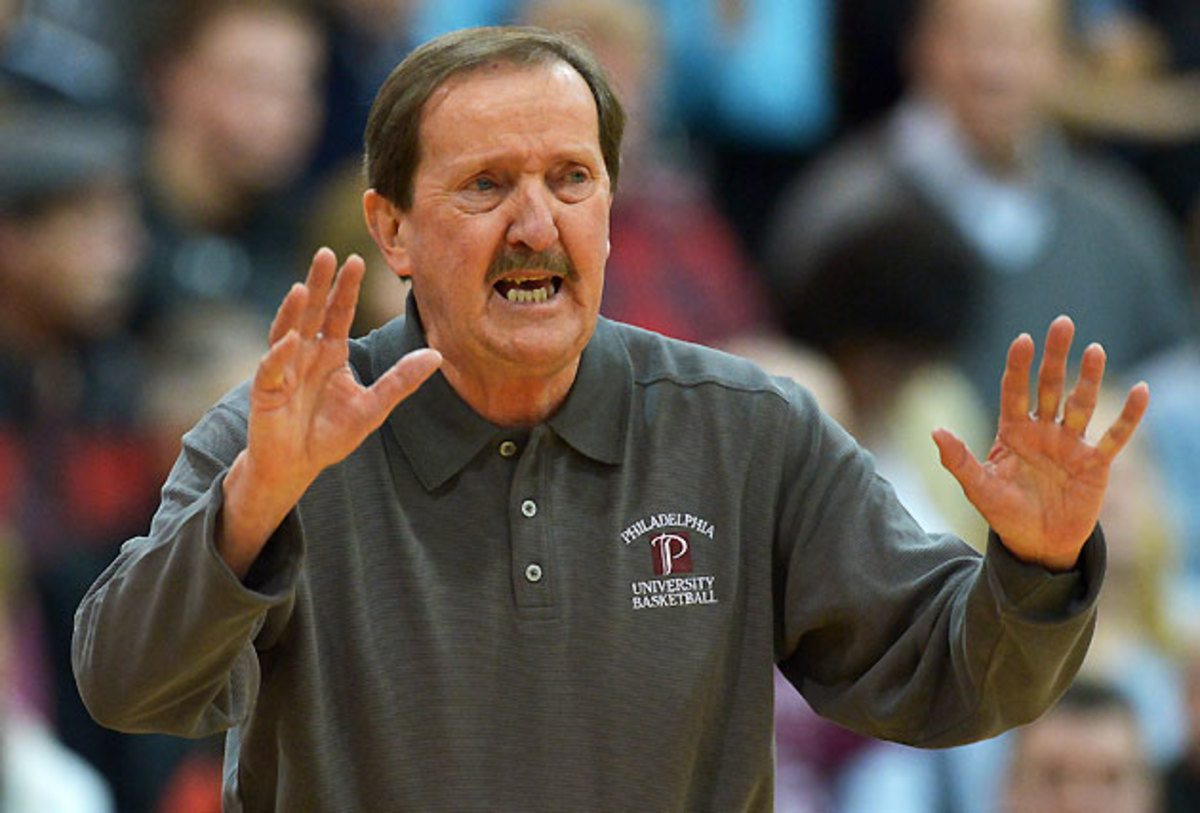

During the pre-game walkthrough, a maroon folder with game notes never leaves the crook of Magee’s left arm unless he’s consulting his play sheet, which lists 33 offensive sets alone. Not all the plays are unique. Magee sometimes gives the same play multiple names in an effort to confuse the opponent. One out-of-bounds play, called ‘Bulls,’ is circled.

Before the game, Magee greets friends and fans in Gallagher’s foyer near his own trophy case, like a sort of celebrity usher. The gym is at a fire code capacity of 1,266 people, and an ambulance with its lights on physically barricades the doors to prevent more people from entering.

With a minute to play, two three-pointers from guard Tyaire Ponzo-Meek put Wilmington ahead 72-70. Gallagher sounds like the loudest high school gym you’ve ever been to. Magee’s expression of conscientious observance during moments of heightened tension never changes, though, not even when Rams guard T.J. Huggins dives for the ball and accidentally takes out Magee’s legs with time running out. The coach pops back up, turns to the scorers’ table with a shrug and deadpans: “What was that all about?”

In the ensuing timeout with five seconds remaining, Magee consults his play sheet and calls out ‘Bulls.’

Nick Schlitzer, the Rams’ best scoring guard, catches the ball and gets off a good look at a game-winning three-pointer. He misses. Wilmington wins, 72-70.

The five exhausted Rams starters, who had played the entire game—Magee often refuses to sub in anyone from his bench the entire game—quickly exit the court. In ‘Classroom 102’, a few dozen reporters form a tight semi-circle around Magee. For once, the creature of comfort is out of his element.

“You see all this,” he says, gesturing at those in front of him, “I’m not used to all of this people-asking-me-questions-after-the-game stuff. This is unusual to me. Especially to losing. We don’t lose here.”

*****

Four days later, a recharged Magee appraises the newest challenger, Post University.

“We can't give up 70 points again, this game has to be in the high 50s, low 60s,” he says.

The pre-game ritual in anticipation of the historic win begins again. Pieces of paper are taped to the back of 80 red and black cushioned chairs—the only non-bleachers in the gym—along one sideline of the court, demarcating them for VIP’s like former Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell. A student-made countdown banner—which, given the school’s history, should probably be sewn, not drawn—hangs static with ‘1’ to go.

There are more friendly faces and fewer media along the sideline for this game. There’s even good spiritual energy. Magee’s 91-year-old mother-in-law, Mary Ann, who has long refused to pray for wins, was so affected by Tuesday’s close loss that she said a full rosary that morning for the Rams, which prompted a grunt of approval from Magee:

“O.K., now we’re ready to go.”

Magee’s games, normally devoid of stoppages caused by television broadcasts, timeouts or even substitutions, often last a brisk 90 minutes. But as the Rams fall behind 22-11, he takes two timeouts.

At the 9:53 mark of the first half, Andre Gibbs hits a three-pointer off of a swing pass from Huggins, initializing an 11-0 run that ties the game. The Rams lead by seven at halftime and blow out the Eagles at the start of the second half. Schlitzer and Derek Johnson hit long jumpers that evoke their coach’s shooting form in this same building 52 years earlier, and a Peter Alexis dunk with 11 minutes left makes it 59-34.

At one point the Rams hit five three-pointers in a row, Magee’s torso lilting with the balls’ arc as if to will the shots in. The team shoots 56 percent for the night, and 55 percent from three.

Philadelphia wins 80-60, and a banner reading ‘1000 Wins Men’s Basketball Coach Herb Magee’ unfurls from on high. Fans politely mill around on the court rather than storm it. One enthusiastic student runs around with a sign reading ‘We Got Herb’ with a drawing of a marijuana leaf.

Magee gives a curt 30-second address over the PA system, crediting students’ enthusiasm for the win, then exits the floor.

An hour later he’s successfully absconded to the Great American Pub, on a barstool with a Coors Light. He listens to a congratulatory message on his phone from Calipari. The preferred fortification, a wall of friends and family, surrounds him. Geri, far closer in age to her husband than to his players, is moved to perform cartwheels on the bar floor.

The only noises of non-celebration the entire night are groans from the Rams players. Magee has told them that instead of having the next day off as scheduled, they will instead practice at 10 a.m.

Running drills 15 hours after reaching such rarefied air is a rigorous move. But in Magee’s world it’s necessary.

After all, there’s always another win to prepare for.