Physicality, technological savvy pave Fotu Leiato's path to Oregon

STEILACOOM, Wash.—The problem with Fotu T. Leiato II playing flag football was that, as a 7-year-old, he couldn’t really grasp the concept of not hitting someone.

It’s not that he was violent or ornery or a schoolyard bully. But Leiato, raised by a father who preached physicality, wanted to show off his gifts. Ten years later his highlight reel, one of the most-watched in the history of the popular recruiting video website Hudl.com, proves Leiato has only gotten better at knocking people over.

Three weeks after signing a National Letter of Intent to play football at Oregon, the school Leiato grew up rooting for, he’s still getting used to the fame that goes hand-in-hand with becoming an internet sensation.

“In this day and age, it’s unusual for kids to be under the radar, especially if they live close to a big city. I think it’s hard for that to happen,” says Don Pellum, Oregon’s defensive coordinator, who didn’t learn of Leiato until early December 2014. “Social media is powerful, and his coaches understood that. You put his tape in, and it’s like, ‘Whoa! Who is this kid? What do you mean he only has two offers? Someone get me a phone!’”

Six months ago, Leiato had no offers and thought no one wanted him. Considered physically underwhelming for an inside linebacker—his Rivals.com profile lists him at 6’0” and 195 pounds—and without money to travel to glitzy camps in hopes of catching coaches’ attention, he wondered if he’d get the opportunity play college football.

But William Garrow had a plan.

As one of five coaches aged 30 years or younger at Steilacoom High, a small school located an hour south of Seattle, Garrow understands the value of social media. So he got to work with fellow assistants Kyle Haller and Mike Martin, also under 30. They created a Twitter account and gave lessons in how to conduct one’s self properly and maturely—and in a way college coaches would find appealing—online. They told their players that no one has gotten a scholarship from a tweet, but there have been plenty to lose scholarships because of one. They pieced together video clips and posted them on Hudl.com, a website launched in 2006 that gives high school, college and professional coaches opportunities to cut, edit and share video clips from around the world. Burning DVDs is so 2005.

Garrow believes much of college recruiting is done via “groupthink;” if one Power Five school offers an unknown prospect, more will follow. He figured Leiato needed to be noticed by just one school, and the offers would pour in.

“You look at him, and he’s not physically imposing,” says Garrow, adding that the first time Leiato showed up on campus in the spring of 2012, he checked in at just 5’8” and 160 pounds. “But he hits like a truck.”

Oregon transfer Vernon Adams out to show he's more than FCS sensation

Just ask his teammates. Leiato’s specialty is special teams, where he knocks would-be tacklers silly. He has a tendency to be so instinctually violent that Steilacoom coaches ruled last fall that there would be no more live reps at practice. Too many players were coming down with the “Fotu Flu,” they said. Schematically, the Sentinels’ defensive gameplan was pretty basic: “Mostly, it was ‘Let Fotu run around and cause havoc,’” Haller says.

It worked. In three years as a varsity player Leiato totaled 188 tackles, including 34.5 for loss. But his energy came with negatives. He often got so excited “we’d rack up more yards in penalties than he’d have in tackles for loss because he was overeager to hit people,” Garrow says. “At practice, he doesn’t understand what ‘half speed’ means.

“Sometimes we’d have to say, ‘We’re going to do a drill—Fotu, you go stand over there away from it.’”

In the stands, his mother, Linetta, tensed up every time her son collided with another player, even though he won almost every time. His father, Fotu I, loved it. Both born in American Samoa, where elders swell with pride when children display their physical prowess, his parents appreciated what he brought to the field.

Leiato remembers when he got taken down for the first time in tackle football in the fourth grade. “All the sudden there’s this white helmet, and it disappears into my stomach.” He vowed to be the one delivering hits instead of receiving them after that. He just didn’t know that would lead to Eugene.

In trying to sell Leiato to colleges, Steilacoom coaches had to be picky about the summer circuit. What benefit would Leiato get from showing up at a camp where a helmet and shoulder pads weren't allowed? In their database that tracks every college football camp at a junior college, NAIA, or Division I, II or III school west of the Mississippi, they thought they could find a good landing spot. So Leiato mowed lawns, moved furniture, painted houses and became a general handyman around the Steilacoom community to raise about $1,000 and attend padded camps.

In June, he boarded a Greyhouse bus for a 16-hour trip to Bozeman, Mont., and a camp on the Bobcats’ campus. Leiato arrived at 2 a.m., was up at 8 a.m. for workouts and got back on the Greyhound that afternoon for an eight-hour trip to Spokane and Eastern Washington’s camp.

“Long weekend,” Leiato says. “There was this one crazy guy on the bus just laughing the whole way to Spokane.” To tune him out, he popped in headphones that crooned Whitney Houston hits (the 17-year-old is an avid R&B fan) and imagined that one day, maybe, he’d be good enough to play college football at a small school.

In the fall, as Leiato terrorized opposing teams, Garrow, Haller and Martin spent their lunch hour calling schools trying to reach coaches. “For more than a month, I think we talked to the same receptionist every single day at Oregon State and Washington State,” Garrow says. Finally, on Oct. 7 Wyoming offered.

Seven weeks later, Leiato’s highlight video went viral.

On Dec. 2, the Washington State-centric site CougCenter.com published a post titled, “WSU prospect Fotu Leiato II has an impressively violent highlight video,” after the Cougars offered him. Viewership skyrocketed.

“In the office, we had been passing it around just because those bone crushing hits that were so fun to watch,” says Erik Pulverenti, Hudl’s general manager. “We were really excited to watch (his journey) because one of our missions is to help build tools that athletes can use.”

How social media is shaking up recruiting; Punt, Pass & Pork

As of Wednesday afternoon, Pulverenti said Leiato’s video had been viewed more than 545,000 times, second most in Hudl history (he held the record briefly in January but was recently bypassed).

Not everyone liked the violence. Some viewers questioned if Leiato’s play was safe and legal and berated Steilacoom coaches for allowing it. Leiato’s teammates posted in comments sections trying to defend him until Garrow told them to stop wasting their time. This is part of an athlete’s life, Garrow explained, and Leiato would have to learn to ignore his critics.

Just as Garrow predicted, college coaches swarmed Steilacoom after they saw Leiato’s video. Garrow entertained calls and texts from Michigan State, Oklahoma (which prompted a text to his fellow coaches that read, “holy crap Mike Stoops!!!”), UCLA and more. But since Leiato’s sophomore year, when he received an Oregon sweatshirt as a gift, he dreamed of playing for the Ducks. Then Pellum showed up at his house.

“I watched his film for the first time before the Rose Bowl, (outside linebackers coach) Erik Chinander watched it, and it’s like, ‘This kid is dynamite,’” Pellum says. “We watched it as a staff right before or after the national championship. Usually, highlights are every three of four plays, and it’s like ‘Hmm, OK, we could use this kid.’ On his tape, it was every play. We’re sitting there talking about how it’s just not fair. He’s laying guys out, vicious hits.

“The loudest guy in the room was (special teams coach) Tom Osborne. He was going crazy, all over the place.”

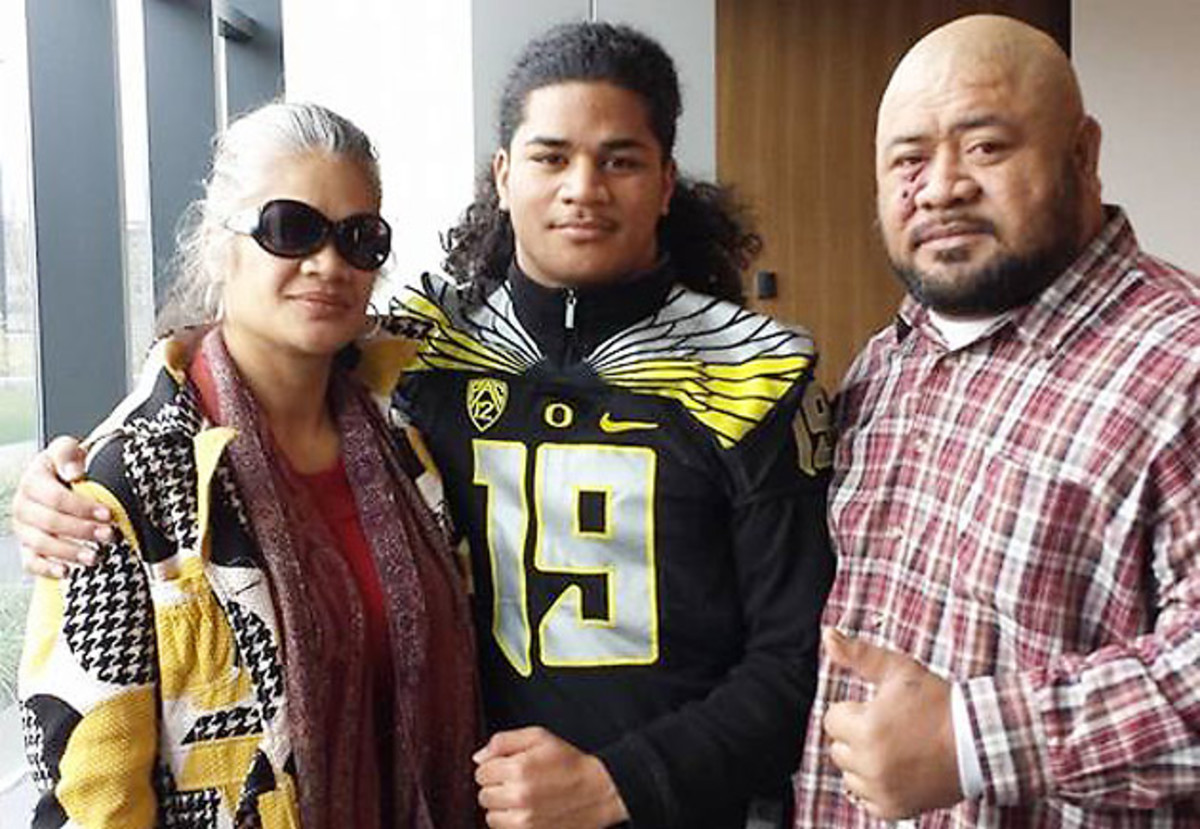

Impressed by Pellum’s sharp dressing—“DP, he’s on point with those suits!”—and sold when Pellum talked about the “brotherhood” in Eugene, Leiato committed to Oregon on Jan. 30. He shared the news with 30-plus family members at a backyard barbeque celebration, where they cheered and cried and promptly lined up to take pictures with Pellum. (They bypassed head coach Mark Helfrich, who was also in attendance and dressed in a polo shirt).

Oregon coaches aren’t quite sure what position Leiato will play, which was part of the appeal. He hopes to find an early home on special teams Leiato is confident he’ll fit in.

His father is just happy he won’t have to watch soccer. When Linetta was pregnant with her first child, she learned she was carrying a girl, Fotu II’s older sister, Whitney. Fotu I sighed when the doctor shared the news. Of course he was happy to have a healthy baby on the way, but he couldn’t shake the thought of, “Dang, now I have to go watch soccer.”

As it turns out, he doesn’t. In Autzen Stadium, it’s football only. Big hits welcome.