How did Carolina lose its way? A UNC grad returns to campus to find out

This story originally appeared in the March 16 issue of Sports Illustrated. You can subscribe to the magazine here.

And hey, babe, the sky’s on fire,

I’m dying, ain’t I?

— James Taylor, “Carolina in My Mind”

My way back? It began with laughter. My oldest child was a high school senior in April 2014, at the point in college admissions season when everyone’s bruised and judgments drop hard and final. He was staring at his phone one night. He and his best friend had already gotten into North Carolina. Now they were texting each other, and my son kept giggling. “Great school,” he said. Then he turned the screen so I could see.

It was the Rosa Parks essay. If you’re one of the partisans—defensive or gleeful—who consumed every bit of spew from the scandal concerning sham classes at Chapel Hill over the last five years, no explanation is needed. The 146-word “Final Paper” written by a UNC athlete for a class in the since-discredited Department of African and Afro-American Studies (AFAM) was described by whistle-blower Mary Willingham in an ESPN report as “not even close to college work.” A sample: Her and the bus driver began to talk and the conversation went like this. “Let me have those front seats,” said the driver.

The athlete, Willingham said, received an A minus. Screen grabs rocketed around the Internet. Like the 2012 news that a Tar Heels wide receiver had plagiarized from website material written by 11-year-olds, the Rosa Parks essay caricatured a truth and reinforced a notion: Once superior North Carolina had lost its way.

Still, my son was hardly bothered. He and his friend liked the triumph of getting into one of the nation’s most selective public universities. I was the problem. I, who wept upon leaving Chapel Hill in 1983, who tried each year to donate some cash to the school, had nudged him forever to apply. But now something, gut level, had turned.

When my son chose to go to UCLA, I muttered, “Good.” Sending one more dollar to UNC felt too much like endorsing an academic crime spree—as well as the UNC administration’s inadequate response. Years of stonewalling, spin, reports and “retirements” had left an impression less of true reform than of erosion, a reputation in retreat, and graduates young and old had been called to account. “Did you take those classes when you were there?” Russ Rose, the Penn State women’s volleyball coach, needled me in 2012. “The ones that didn’t exist?”

[daily_cut.college basketball]And that was before Rashad McCants, the second-leading scorer on the 2005 national championship basketball team, told ESPN last June that, during his three years in Chapel Hill, he and other players slid by with the illegal benefit of no-show courses, a complicit academic support staff and athletic department—and the “100%” knowledge of coach Roy Williams.

On June 30 the NCAA announced that it was reopening an inquiry that had already produced the first major sanctions against UNC in half a century. On Oct. 22 it became clear why. The university-commissioned, independent report released by former federal prosecutor Kenneth Wainstein confirmed that what had long been painted as a rogue academic operation was in truth a wide-ranging “scheme” started in large part to keep at-risk athletes eligible. Worse, the scandal went well beyond NCAA purview. At least 3,100 North Carolina students took advantage of the so-called AFAM paper classes from 1993 to 2011, and more than half were nonathletes.

The impact of all this on Tar Heels morale was seismic. No other flagship university had possessed a more pronounced sense of its own virtue; balancing big-time sports and fine academics, doing it the “right way,” had become so vital to UNC’s identity that the school claimed ownership of it. And why not? While “public Ivies” such as Michigan and UCLA spent the last 20 years struggling to reclaim athletic greatness, the so-called Carolina Way kept producing.

Now? Graduation rates, diplomas—the very value of a UNC degree—are all in question. “Once [the fraud] affected the core student body, it became a knife in the back: How could our university do that to us?” said former Tar Heels fencer Bob Largman, the U.S. fencing team leader at the last four Olympics. “It’s disheartening. That sure foundation that I had with the university is crumbling. And I don’t know what it will take to rebuild it.”

For Largman to feel this made sense: He exemplified the Carolina Way better than anyone else I knew. But I was a puzzle. Because in our time on campus, no one else had fancied himself more the cool skeptic about UNC sports. Yet here I was, 32 years later, feeling the same disillusion and loss.

How had I come to be such a believer? What had I missed?

*****

I arrived in Chapel Hill on a bus early one August morning in 1981, mouthy and unformed, 19 years old, a Northerner, a transfer, a pain. Full disclosure: I owe the place. My home and family, even the option-packed SUV that I drove to North Carolina last month in an attempt to sort out the scandal, exist in large measure because I graduated from there. Simply, the school bristled with quality, in class and out. Swimmers and wrestlers and lacrosse teams vied for national titles, the football team was ranked in the Top 20, the baseball team had future major leaguers B.J. Surhoff, Walt Weiss and Scott Bankhead. And all of that was just the undercard for the main event.

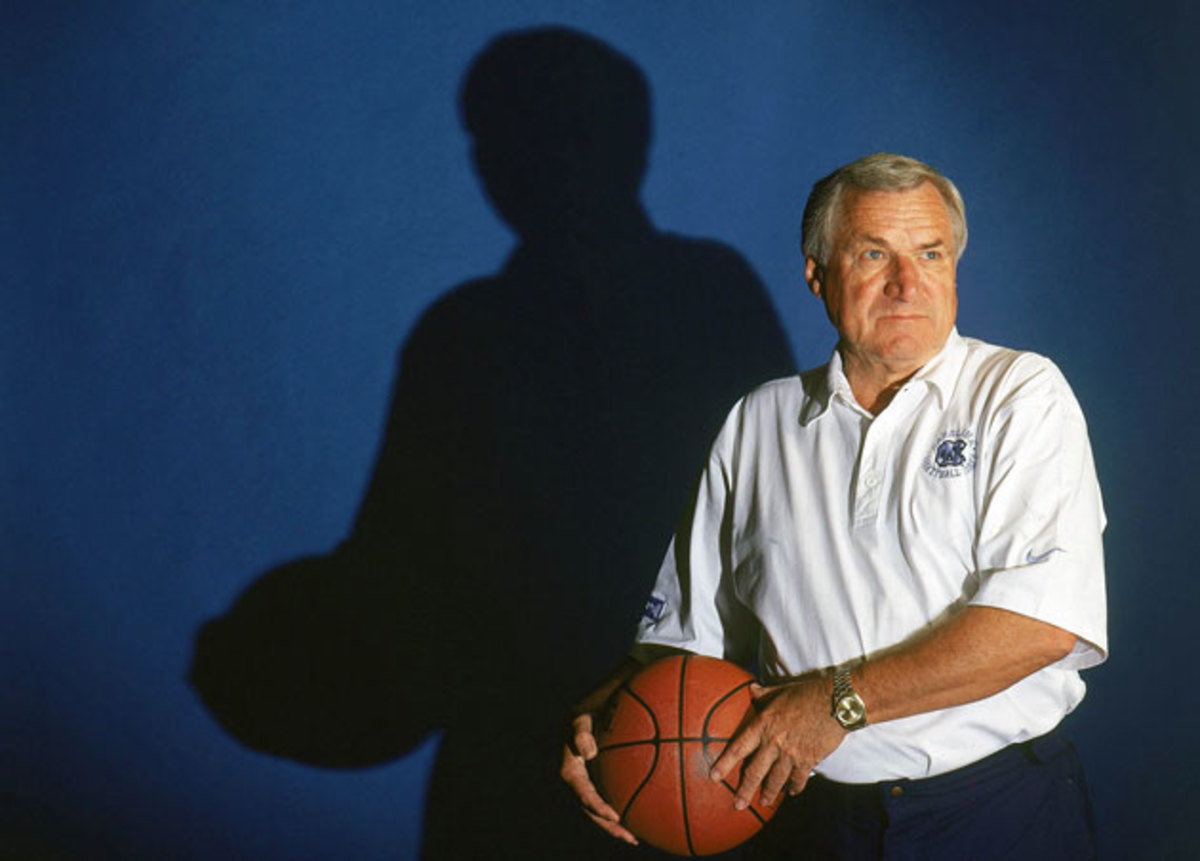

By then Dean Smith, famous for his tactical brilliance, nasal honk and 96% graduation rate, had been to six Final Fours and produced dozens of NBA players. His pivotal role in integrating Chapel Hill restaurants and ACC rosters, and his protest against the Vietnam War, lent him unmatched moral heft. Smith insisted that scorers not chest-pound but point to the passer who made a basket possible, and that became statewide code for unselfishness. “He coached basketball,” Largman said, “but I believed he was my coach.”

Dean Smith, legendary North Carolina basketball coach, dies at 83

Even the donnish ring of that first name, Dean, felt like the finishing touch on some grand design. With his team playing in a rickety jewel box for 10,180 tucked near the cemetery, with the football Heels confined to a 48,000-seat stadium that, legend had it, could never rise above the surrounding pines, there was a tangible sense of sports and academics in near-perfect proportion. Why would that ever change?

I covered UNC basketball for The Daily Tar Heel during the 1982–83 season, just after Smith finally won his first national title. Something shifted in the tone of Tar Heels fans then. Someone scrawled god on Smith’s name on a wall inside the student apartments at Granville Towers. ACC titles were no longer divine; now that UNC had shed its virtuous loser label, winning it all was the expectation.

Smith had seen this before. In 1957 the Tar Heels won their first NCAA title, under coach Frank McGuire, but within four years recruiting violations had landed the school on probation, and players’ involvement in a point-shaving scandal had forced McGuire out. In ’61, UNC president William Friday shuttered the annual Dixie Classic, slashed 11 games off the hoops schedule for five years and demanded that his new coach, Smith, run things clean.

In other words there’s no “Dean Smith” without Bill Friday, himself a staunch proponent of integration, free speech and academic excellence. Yet at least once it was the coach who saw fit to lecture the educator. “I cannot see how this can be an example of what we want in intercollegiate athletics,” Smith wrote in a blistering letter after his boss compared UNC’s 1982 team to North Carolina State’s ethically suspect ’74 champions. “Our basketball program is much more similar to Duke’s.”

Then Michael Jordan took the stage.

*****

No one had seen it coming. Jordan had hit the jumper that gave Smith his NCAA title, of course, but the phenomenon that begat sneaker wars, eight ESPN channels, fashionable baldness and one‑and‑done—the force that made sports culturally central—began during Jordan’s sophomore year. Night after night that season, Carmichael Auditorium’s ear-shattering din met its match: Jordan destroying Duke with 32 points and a triple-pump fadeaway. Jordan gutting archrival Virginia in the final minute by plucking away an inbounds pass and crunching the dunk to win.

I wrote it all down. I fed off the frenzy and filed some of the most awful ledes possible; rereading them now, even I want to punch me in the face. But amid all my floundering, I sensed a further tip in the balance. From my dorm on South Campus, I could see the trees falling to make room for a 21,000-seat, $34 million basketball arena, its construction financed by the boosters’ self-styled Educational Foundation, aka the Rams Club. So I wrote a column, “The Price of Glory,” ripping it.

... Is the construction of a new Student Activities Center justified in the face of a recession, when 10 percent of America is out of work, and financial aid has been cut to the marrow? Why is the Educational Foundation able to tell the administration that come hell or the NCAA they [sic] are going to build a new coliseum? It’s our money, they say, we can do what we want with it.

If the university didn’t want it, why didn’t they [sic] just tell the “Educational” Foundation that UNC teams wouldn’t compete in the new arena? If the university supports this garish display of elitism, then the tail is just wagging the dog and both the students and the athletes are being cheated ...

And so on. The piece is, to say the least, flawed. Straw men, strained logic and snark abound. In passing I mentioned something about “slide courses,” but that was a knife tossed in the dark. No, the biggest concerns in college sports back then were overzealous alumni, free cars and $1,000 handshakes. Academic impropriety at UNC? Unthinkable. I’d taken “rocks for jocks” (introductory geology) and sweated tests. I’d lived with two soccer and two football players who studied plenty. I shared a psych class with Tar Heels center Brad Daugherty, and he showed; Smith’s assistants made sure of it. That’s why so many of Smith’s former players still can’t accept that the no-show classes scandal even occurred.

“It just didn’t happen when we were there,” says Daugherty, now an ESPN basketball analyst. “So we’re trying to figure out who benefited and who was the first—if somebody did this. Because as Sam Perkins said, ‘We went to class.’ We wrote papers, got our papers marked up and took tests. I don’t know how it could’ve happened.”

How? Slowly, by all accounts. The imperatives of sports and academics (What takes priority, the road trip or the test?) have been clashing nationwide for a century, even at Chapel Hill. As Samuel Williamson, vice chancellor for academic affairs from 1984 to ’88, told Wainstein, “Every time we closed the barn door, the athletics department built a new barn.”

When I reached the retired Williamson at his home, he said, “My name is probably on your diploma” (it is) and explained that “new barns” went beyond gut classes. He included the 1980s summer school professor—soon relieved of his duties—who allowed athletes and others to finish a correspondence course in five days. And four flunking football players who tried to retroactively withdraw after a bowl game for “medical reasons.” At least twice, Williamson said, “Honor Court cases in the summer were not pushed because somebody said, ‘It’s going to hurt the guy’s chances for a pro contract.’ ”

But the most consistent battle at UNC centered on “special admits,” those at‑risk high school seniors who required review by the Committee on Special Talent. During his time, Williamson said, the university budgeted 32 special admits for each freshman class. A half dozen were reserved for musicians and artists. Football got 15 or so, men’s basketball a couple, wrestling a few. Coaches would present candidates to the admissions office, which forwarded their dossiers to the committee. “Every time you thought you had seen a too-marginal case,” Williamson said, “they’d give a new excuse: This guy, he can make it.”

Debates among committee members were lengthy, and great weight was given to an inferior candidate’s “character.” John Shelton Reed, a UNC sociology professor for 31 years, sat on the special-admits committee in the mid-’80s and recalls three athletes—one a men’s basketball player—being admitted with rock-bottom SAT verbal scores of 200. That was possible then under NCAA rules but far from the norm for most scholarship UNC athletes. Reed and two colleagues voted no, lost and moved on. “To this day I regret that I didn’t blow the whistle right then and there,” Reed says.

SI Vault: Long Ago He Won The Big One: Dean Smith's best victory

Dean Smith didn’t argue any prospect’s case to admissions; he left that to his assistant Eddie Fogler. But the coach was well aware of the concessions being made. “No matter what universities tell you, they make significant admission allowances for athletes,” he told SI before the ’95–96 season. “No college team that has made the Final Four over the past 20 years has had a starting team made up of players who got 1,000 on their college boards.”

“So,” Reed says, “we were admitting guys who had a lot of trouble reading and writing, and they were taking courses like Arts and Crafts for Elementary School Teachers. They learned how to make turkeys out of pinecones. But the classes met. Some [players] even graduated. What I’m trying to say is, the Carolina Way did everything the rules allowed. You were admitting students with some sort of vote of the faculty committee—stacked, to be sure, but they were approved. It was a charade at times, but it was within the rules.”

I started to react in horror ... then paused. My high school transcript and SAT math score would land me in the admissions office’s reject pile today. I too had been somebody’s judgment call. Then again, even my worst professors were brilliant, demanding; a few pinecones would have been a relief. But I would have felt cheated.

Reaction to my Dean Dome screed varied. A few athletes liked seeing a bomb tossed, and it jibed with faculty concern that the arena signaled trouble. The pressure to win could only rise, if for no other reason than to fill seats. “The Big Rams were beginning to call the shots,” Williamson says.

The university chancellor, Christopher Fordham, asked me why I’d dare write such a thing. Roy Williams, then Smith’s assistant, bawled me out in his office. A rumor went around that football players had been sent out to beat me silly; I slept that night with a desk leg by my side and, awakening untouched, screwed it back in the next morning.

After the season Smith called me into his office at Carmichael. Startlingly, he was the only university official who seemed more curious than mad. So I rattled on a bit, and he asked questions and shook my hand as I left. It all felt academic: The Dean Dome was going to be built. His name would be on it, no matter that he hated the idea. The Big Rams, he was told, would have it no other way.

*****

My first day back last month, I felt like a ghost haunting a McMansion. The lovely tree-and-brick core of the campus remains, but there’s been a doubling in size at the edges. Kenan Stadium too has been fattened up, with 15,000 more seats, raising capacity to SEC standards. That would have been seen as an insult in the days when the ACC fancied itself a conference with more on its mind than football now and forever. But no more.

Undeterred by the firing of coach Butch Davis in 2011, as the academic scandal unfolded, North Carolina is determined to be a Top 20 football program again. This was underscored in January when the school hired as its defensive coordinator former Auburn coach Gene Chizik, whose ’10 national title was accompanied by accusations of NCAA violations (investigated and unfounded, says UNC athletic director Bubba Cunningham). As it happened, the day before my arrival former chancellor Holden Thorp, whose promising tenure was a 2013 casualty of the scandal, had been musing in the Raleigh News & Observer about the new Tar Heels reality. “We thought we were different from Auburn,” said Thorp, now the provost at Washington University in St. Louis, “but now we know that we’re not.”

That night I stepped inside the Dean Dome for the first time. Virginia was in town, a rival again, but everything else was different. The distant Carolina band labored heroically, but the crowd mostly murmured, and UNC played miserably. After the crowd filed out, I climbed the long steps to the dimmed concourse. High on the wall hung a massive photo of the 1967–68 team, Charlie Scott the lone black face, Smith’s head tilted with that little grin. Next to it was the next season’s squad, then the next, and soon I was drifting past Bobby Jones and Bob McAdoo, Walter Davis and Mike O’Koren and Dudley Bradley, then the ’82 champions, all smiling except Jordan.

All the while, in the dark, I kept hearing -Daugherty’s voice: Who was the first?

The Wainstein Report pinpoints 1993—four years before Smith’s -retirement—as the year that Debby Crowder, the AFAM office manager who was so devoted to UNC hoops that she was known to call in sick after losses, began devising “paper classes.” The “shadow curriculum” run by Crowder and department head Julius Nyang’oro “required no class attendance or course work other than a single paper, and resulted in consistently high grades that Crowder awarded without reading the papers,” the report said. (Crowder retired in 2009, and Nyang’oro was forced to retire in ’11.) A disproportionate 47.4% of the enrollees in AFAM classes were athletes, most of them football and men’s basketball players.

In all, basketball accounted for 54 enrollments in AFAM independent studies during Smith’s final four seasons. Wainstein found nothing to suggest that Smith had knowledge of Crowder’s scheme; indeed, Wainstein found it impossible to know which of the 54 courses were bogus and which were proper.

But Willingham and UNC history professor Jay Smith, co-authors of the new book Cheated: The UNC Scandal, the Education of Athletes and the Future of Big-Time College Sports, say that, based on documents and transcripts, Smith’s basketball program was the impetus for the fake courses. “We show pretty persuasively that it all started with easy-grade independent studies in the late ’80s for a handful of weak students on the men’s basketball team and mushroomed from there,” says Jay Smith. In the fall of ’88, he and Willingham say, Nyang’oro taught two of his earliest independent-study courses to two men’s basketball players “with marginal academic records.” Neither was an AFAM major; both earned B’s. One player took another AFAM independent study the following summer, and in the summer and fall of ’91, Nyang’oro oversaw independent-study courses for four more players.

The Wainstein Report states that Nyang’oro’s early independent studies called for regular student meetings and progress reports. “You had to do the work,” former UNC forward Kevin Madden told me when I called him. After being ruled academically ineligible his sophomore year, 1986–87, Madden took both regular and independent studies classes in AFAM—and preferred the former. “That was hard,” he said of independent study. “You turned in, I think it was, two papers per week.”

Declaring himself academically motivated for the first time, Madden says that at times he would park himself in a study room in the Dean Dome at 6 a.m. Another player’s wife tutored him endlessly in math. When Madden told assistant coach Bill Guthridge, on the flight home from one game, that he was skipping his 8 a.m. class, Guthridge showed up at his door at 8—and made him run. Indeed, to the outside world life in Smith’s program in the late ’80s looked much like it always had. Rigid. By the book. And, to rivals, annoyingly upright. When star forward J.R. Reid missed a 1 a.m. curfew by a few minutes on the eve of a showdown with UCLA at the ’89 NCAA regional, Smith famously sent him home. “A rule is a rule,” Smith said.

UNC teachers, though, were nervous. The balance was shifting fast now: The Dean Dome opened in 1986, and two years later football coach Dick Crum was forced to resign amid pressure to upgrade the team. In December ’89 a faculty committee led by writer Doris Betts capped a 10-month inquiry with a report declaring that “all intercollegiate athletic programs of NCAA Division I‑A, including our own, are in varying degrees in conflict with the purposes and standards of universities.” The so-called Betts Report made 32 recommendations for reform, including reining in the Rams Club and eliminating spring football and freshman eligibility. In the absence of real national reform, the report said, “we regard withdrawal from intercollegiate athletics as a serious alternative to the present state of things, which is intolerable.”

That got a big laugh, not least because committee members in general found the UNC operation “very cleanly run,” as sociology professor Henry Landsberger put it then. “The program is certainly not like an Oklahoma.” Yet in ensuing years, complaints from various counselors in the Academic Support Program for Student Athletes (ASPSA) about Nyang’oro’s demands on athletes enrolled in independent studies began to mount. “Crowder told [Nyang’oro] that the ... counselors believed he was ‘being an ass,’ ” says the Wainstein Report, “and were rethinking whether they should be steering student-athletes to AFAM classes.”

UNC AD Bubba Cunningham discusses fallout from Wainstein Report

Already the counselors saw what every academic watchdog had missed: that the loose construction of independent studies, under a willing professor, could be a tool to air out schedules and keep athletes eligible. Such courses were zealously regarded as redoubts of academic freedom. As department head starting in ’92, Nyang’oro operated with next to no oversight, according to the Wainstein Report; when he buckled to pressure, eliminating regular assignments and meetings and ceding control to his office manager, the administration had every excuse not to notice. Thus was built the biggest and best-insulated- barn yet: Crowder administered and graded independent studies, using them as GPA boosters for the academically impaired.

AFAM wasn’t the only department to swing so freely; philosophy lecturer Jan Boxill, who was chair of the faculty and head of UNC’s Parr Center for Ethics, was discharged last October for steering athletes into sham courses, doctoring students’ papers and sanitizing an official report in an attempt to shield the athletic department from NCAA scrutiny. From 2004 to ’12, The Daily Tar Heel reported, Boxill also taught 160 independent studies—20 in one semester. (The standard runs between one and three per year.) Wainstein’s inquiry also presented counselors’ emails that hinted at friendly paper classes conducted by a professor in the Department of Exercise and Sport Science.

Clearly, a standard had fallen at UNC, and I was taking it personally. My independent study in 1983—with Betts Committee member Townsend Ludington—was a privilege. It required a written proposal, an ambitious syllabus, a lengthy paper and regular meetings. But perhaps as early as ’89, independent studies were being used not only as a reward for academic excellence but also as safe harbors for special admits, whose numbers would grow substantially: UNC now reserves about 160 special-admit slots for athletes.

“There was no other way to keep these guys eligible,” says Willingham, a learning specialist for ASPSA from 2003 to ’10. “I participated in a scam for seven years and rationalized it like everyone else: I was helping these guys. They were learning something. During the time they had these fake independent classes, we got time back to work on real classes and do remedial work.”

Maybe UNC administrators, deans and professors thought they could manage the ever-increasing tension between academics and sports because they had done it for so long. Call it hubris: As the athletic budget was expanding from $9.1 million in 1984 to $83 million last year, no one in power saw that a department with that much weight would seduce, intimidate or alter everything in its orbit. Or maybe call it fear: “Nobody wanted to disturb the notions of what the Carolina Way had meant,” Thorp says. “As we discovered the problems, there was this additional barrier to bringing them into the open because nobody wanted the mystique to go away.”

*****

The team photo from the Dean Dome that lingered with me was from 2004–05, of course. Who knows how long it will stay up there? People kept asking, and I asked back, Do you think UNC will have to vacate those wins, that title? The national championship trophy gleams at the players’ feet. And there on the right, side-by-side, sit Rashad McCants and Roy Williams. Both grinning. Williams, in fact, looks as happy as a man can be.

I went back to Carmichael, domain now of the women’s basketball team, and it was empty, gauzed by memory. Smith’s old office was long gone. Women’s basketball coach Sylvia Hatchell knew Bill -Friday—who in 2012 called the scandal his university’s worst “humiliation” ever and then died a week later—from back home in tiny Dallas, N.C. She spoke of how much she had trusted Boxill, who served as the team’s academic adviser and, according to the Wainstein Report, in 10 years steered players into 114 enrollments in paper classes. Eighty-one percent of Hatchell’s players have graduated. The roof of her house is painted Carolina blue.

“When you look at the whole big picture, this was a small, small, small fraction,” Hatchell said of the number involved in the scandal. “And I’m not making light of it. But when you compare that with everything else? Carolina still has the It factor. We are elite. We are the school. It’s still the Carolina Way. It’s still extremely prestigious to go to school here, to play here.”

Everyone, officially, wore the same brave face. I went to South Building for the first time since the old chancellor chided me. The new one, Carol Folt, spoke of the 70-plus reforms put in place since 2011 and said that holes in advising and independent studies had been filled. The school’s accreditation is under review; UNC is going to be stronger, she said. When I asked if the money in college sports—at least $16 billion in TV contracts alone—made the “right way” impossible now, Folt led me like a child back to the rogue nature of Crowder’s operation. Given this level of denial, the hiring of Gene Chizik made a lot more sense.

Down on South Campus, Bubba Cunningham, Notre Dame–trained, was sure the balance could be restored. The caliber of UNC -student-athletes, he said, has markedly improved: Five years ago there were 40 extreme academic risks in the -special-admit pool; last fall there were nine. Meanwhile the aging Dean Dome needs improving or replacing, and you can bet Rams Club cash that it’s not going to get smaller. That things went so horribly sideways at UNC, of all places, doesn’t seem to give Cunningham pause. “You can build great academic and athletic traditions together,” he said. “Carolina’s one of the schools that can. But when you make mistakes, it’s really painful. So we have to regain our confidence and build back trust. It has just taken longer than I thought.”

*****

Roy Williams, who returned to steady the program in 2003, is one of the few people left at UNC from my time. When we met in his office, he said he remembered me, if not my screed or the way he’d dressed me down. So we talked instead about his definition of the Carolina Way and about how Smith had told him to be his own man when Williams left for Kansas, so he let the fans there wave during opponents’ free throws, and—this saddens him—his players at Carolina don’t point to the passer much anymore.

Then we talked about the Wainstein Report, which stated that Williams’s longtime academic adviser Wayne Walden had knowledge of the bogus nature of the AFAM courses. Williams said that it was his own unease over players’ “clustering” in one major—not any desire to insulate the program from future -trouble—that impelled him to pull aside his longtime assistant coach Joe Holladay in 2005. “I said, ‘Joe, I don’t feel comfortable. Why would all these guys be doing this? It must be the easiest thing. Let’s let them major in what they want to major in,’ ” Williams told me. “Now, I just said, ‘Let’s let them major . . .’ [which] sort of indicates that maybe I thought they’d been pushed. But I didn’t feel any improprieties.”

That Williams—or the detail-demon Dean Smith, for that matter—didn’t suspect something awry in the AFAM classes seems impossible. After all, a coach’s career, program and reputation depend on constant scrutiny of each player’s actions throughout a day. “I can’t believe Roy Williams doesn’t know what the hell’s going on,” said Williamson, the former UNC provost and dean. “If I believe that, I believe donkeys fly.”

Williams knows what people say. His calm response goes back 27 years, to when he was hired at Kansas. He says he was told then that professors didn’t want him or his assistants patrolling classrooms or even striding the quad. His job was only to swing the hammer—extra running, decreased playing time—when class attendance or unfulfilled course assignments became an issue. “You don’t know the push to keep coaches out of the academic side because people are worried about ‘undue influence,’ ” Williams said. “The faculty doesn’t want to be in the position where somebody says, ‘He’s friends with the coach.’ ”

Williams reacted more emotionally to McCants’s charge that the coach knew about the academic fraud. McCants said last June that during the basketball team’s 2005 title run he never attended or produced work for four AFAM classes, for which he got straight A’s and a spot on the dean’s list. (McCants’s teammates denied his account wholesale, but the News & Observer soon reported that five members of the ’05 squad, including four key players, took a combined 39 classes “identified as confirmed or suspected lecture classes that never met.”) Williams’s eyes went red; he started stammering and came very close to calling McCants a liar. Then something stopped him.

Smith’s devotion to his players, managers and staff created a far-flung, multigenerational basketball family with one unspoken law: Always help—and never speak ill of—someone from the program. (Once, when Williams told Smith that he was “loyal to a fault,” his mentor stared him down and said, “You shouldn’t use those words in the same sentence.”) McCants shattered that rule. Now, talking about him, Williams shook his head once, twice ... but couldn’t cross that line.

Whether Williams will survive the scandal is anybody’s guess. He has won two national titles for North Carolina, matching Smith’s total, but the reservoir of affection for Williams in Tar Heel Nation could simply never be as deep. Many players whom I know speak of his integrity, but it doesn’t rise as obviously off his shoulders; when Williams is seen tearing up or saying dadgum, half the strangers watching wonder if he’s really that sad or rustic—or far smarter and harder than he lets on.

But this moment I took at face value. No one has ever questioned Williams’s love for his mentor, his better angel. “God bless Coach Smith,” he finally said, softly. “What Rashad McCants said was not true. As opposed to saying he lied, I’d like to say that what he said is not right.”

*****

I was back home on a church basketball court, arguing, when I heard the news. Play had stopped because my 12-year-old son had double-dribbled just before hitting a 20-foot -jumper—his best of the game—and I called the violation. He wanted the shot to count. I refused. I can’t say that “a rule is a rule” was going through my head, but I know Dean Smith’s impeccability had informed my attitude around a bouncing ball for decades. “You need to get it right in practice, or you won’t get it right in games,” I kept saying. Then a text arrived saying that Smith, 83, was dead.

I made a few calls. The consensus seemed to be gratitude that dementia had spared the old coach this knowledge: His “right way” was in ruins, and the progressive bastion he’d championed had been targeted for a makeover by North Carolina’s right-wing governor, Pat McCrory, who since 2013 has been pushing to recalibrate UNC’s curriculum away from areas such as philosophy and antipoverty studies and more toward job creation.

“It’s very sad,” said Pulitzer Prize–winning book critic Jonathan Yardley, UNC class of ’61 and father of two Chapel Hill alums. “I have hanging in my home office a framed Distinguished Alumnus award that the university was kind to give me about 25 years ago. It’s always meant a lot to me. But I look at it now and think, Jesus, do I really want that on my wall?”

Two weeks later I made one last trip to Chapel Hill. Thousands lined up, a river of Carolina blue, outside the Dean Dome for the Sunday memorial, and most of the old faces surfaced. Billy Cunningham, Larry Brown. Guthridge in a wheelchair, Kenny Smith, Antawn Jamison. Men cried, video clips were played. The scandal was alluded to only twice. First, former player Mickey Bell stood onstage and said, “All of us should thank Roy Williams for keeping the values that Coach Smith created.” Second, Smith’s lifelong friend and pastor, Rev. Robert Seymour, said during the benediction, “We honor Dean Smith when we support the civil rights for every human being. We honor his memory by never”—and here Seymour’s voice rose to a cry—“allowing- athletics to eclipse academics.”

But the best moment came before that. Williams stood at the podium and gave a gracious speech, full of flint and spark. “Every day our lives will show something that Coach Smith gave us,” he said. “The way we treat people with respect and dignity, and the way we care. Because that’s what Coach Smith did.” Then he asked the crowd to raise their hands, and 10,000 fingers shot up, pointing to the passer, the past, like a sudden bird going.

Mine went up, too, before I could stop it. It was a salute, I guess, beyond disgust and rage, an appreciation for the ideal if not the execution. Williams turned away, but some fingers remained raised 10, even 15 seconds longer before dropping, before the truth of the last years finally took hold. The games would go on. But it was over.