Schembechler's the name. Football's his game. They love him at Michigan

Editor's Note: Wednesday would have marked legendary Michigan coach Bo Schembechler's 86th birthday. To celebrate the occasion, SI.com is re-publishing Douglas S. Looney's feature on Schembechler that originally ran in the September 14, 1981, issue of SI.

On a recent soft, warm evening at Glenn (Bo) Schembechler's home in Ann Arbor, dinner is being prepared. Bo is cooking chicken on the charcoal grill out back, alternating his attention between his task and hollering at his wife, Millie, who's fixing the rest of the meal in the kitchen. "The chicken is done, goddam it," Bo bellows. "Hurry up. I'll be bitterly disappointed if I overcook this chicken just because you can't get organized in there. Damn, the chicken is just right now, Mil, hurry up."

Breaking down the 10 most important position battles of spring football

Millie, to her enormous credit, ignores the wordstorm blowing through the screen door. She is one of the few people in the U.S. who would dare. "I'm not afraid of him," she says, against a high-decibel backdrop of continuing advice and abuse from Bo, chicken cooker and card-carrying expert on all matters. "Well, I'm not afraid of him anymore." In truth, most everyone else isn't afraid of him any less. Coming upon Bo at his worst equates with meeting a hurricane in full force—at his best he's about like a tornado just getting organized. You don't explain Bo; you take shelter. However, there is much speculation that the 52-year-old University of Michigan football coach, who has put together a team poised to make a serious run at the national championship—if it can get past powerful Notre Dame on Sept. 19—has mellowed. "I have not mellowed, goddam it," he says.

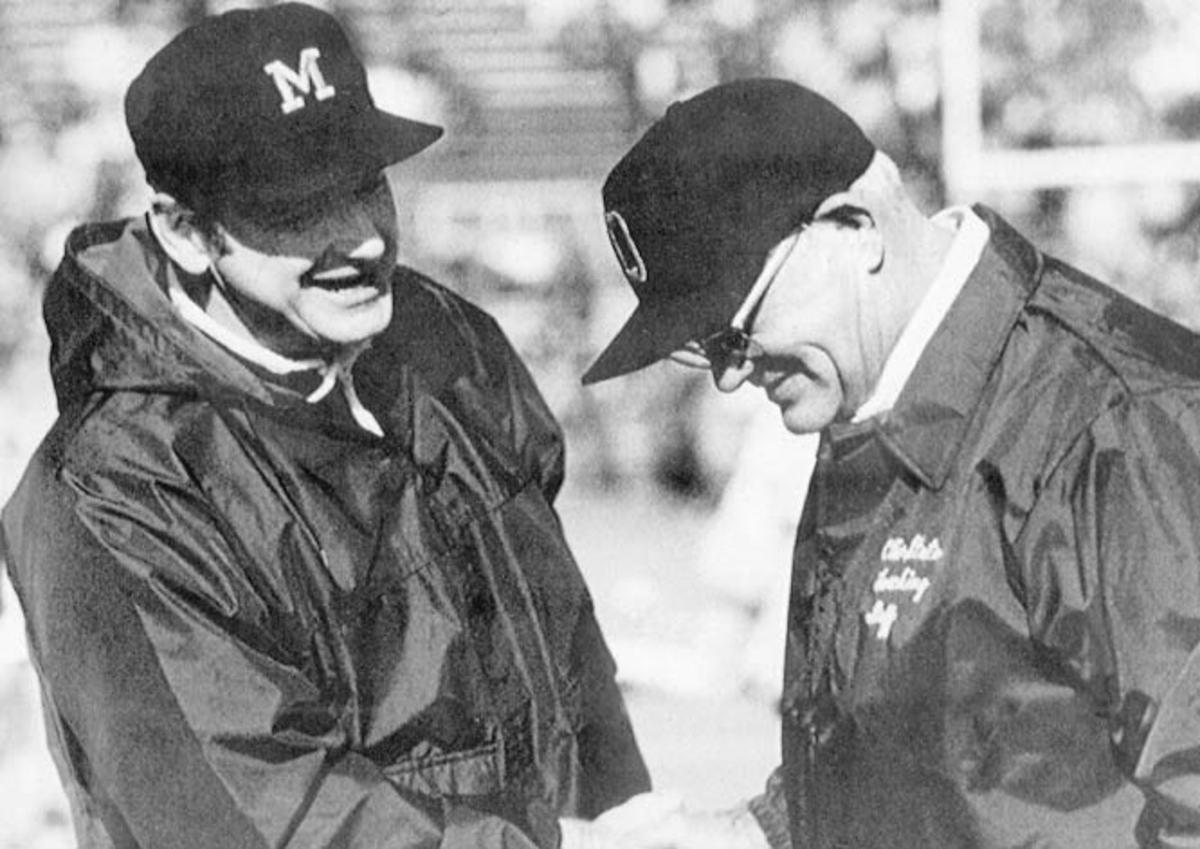

But he has, in subtle ways. One old buddy, Gerald R. Ford, center on Michigan's 1932 and ‘33 national championship teams, who lived for a spell in downtown Washington, says, "Bo has relaxed a little. Frankly, I think he's a more effective coach when he's less tense." But the mere mention of his mellowing sets Schembechler off, and he goes out of his way to prove it isn't so.

For example, when linebacker Mike Boren walked into Bo's office recently, Mike opened his mouth but Bo spoke first, of course.

"Look at your hair."

"I was born with it like this."

"Naw, you got it all pushed up. You weren't born with it like that. It wasn't even like that when I met you. Get a haircut."

"Bo, it's only a half-inch long."

"Get a haircut. How much do you weigh?"

"Oh, 218, but I've been sick."

"You were 218 and sick last time you were in here."

"I'm a sick person."

"Get unsick."

Nothing is moderate about Bo. He has a firm view on everything. "If I make a mistake," he says, "I'm going to make it aggressively. I don't believe in sleeping on a decision." It is as impossible for Schembechler to hold his tongue as it is for the ocean to skip just one high tide.

He has two favorite expressions. The first is, "That would have killed an ordinary man." He uses that to refer to almost every bad thing that happens to him. Not long ago he was knocked down on the football field. Everyone held his breath until Bo hopped up and said, "That would have killed an ordinary man." The other is, "Got it?" Every time Bo talks to you, you have to acknowledge you got it, got it?

"I'm gonna tell you something, got it?" asks Bo.

Yup.

"Pay attention, got it?"

Yup. Got it, got it, got it, got it, got it.

As the evening turns dark and even more gorgeous and serene around the Colonial-style house, its master only gets more rambunctious. Millie serves dessert, and after one bite, Bo says, "I've had pecan pie all over the world, and I want to tell you, Mil, this doesn't measure up." Millie immediately rises to her own defense, citing the balky oven with the erratic temperature control, distractions....

"It's terrible," interrupts Bo. "That's all. Look, nobody can eat it."

"But, Bo," says Millie, "I got the recipe from the cookbook Barbara Dooley [wife of Georgia football coach Vince] sent me. It's Extra Rich Georgia Pecan Pie with molasses. I did...."

Bo interrupts, of course. "See, the problem is the ingredients aren't any good. Then you messed up cooking it. That's that. Got it?"

The subject is closed. And Bo is right, it did happen to be less than great pecan pie. But heck, it was Barbara Dooley's fault, and she was 600 miles away. The point is, this is classic Bo Schembechler. He talks straight ahead; no matter what the circumstances, he says exactly what's on his mind; he makes judgments on everything; he is secure in every way; he dominates everywhere and everybody. All of which makes him, remarkable as it sounds, a good guy up close. A really good guy.

"It must be great to feel as confident as he does," says Millie, "but he truly is a good person. All I have to do is what Bo's mother told me. She said, 'Handling him is easy. Just remember that when he loses a game, don't talk to him.' And he does hurt so bad when he loses one of those dumb football games."

O.K., from a distance, Bo comes on like a yahoo. And that's Bo's public image. He has had horrible problems with the press, which has this nasty habit of wanting to talk to him when he loses, his mother's advice notwithstanding. But even if the media's timing were better, it probably wouldn't make much difference, because Bo hates the press. Not just a little. A lot. The Voice of Michigan Football, Bob Ufer, says he has tried to get Schembechler to be nicer to the media. "But he told me," says Ufer, "'Bob, if I win I don't need the press, and if I lose they can't help me.'" Ufer defends Schembechler, whose record at Michigan over 12 years is 114-21-3; Bo's teams have won the Big Ten championship twice and tied for it seven times. Says Ufer, "Bo has two categories of things in his life: what matters and what doesn't matter. What matters is football. What doesn't matter is everything else. Bo is the kind of guy who is so dedicated that he doesn't realize how he's coming off."

Woody Hayes, former Ohio State coach and noted expert on press relations, says of Bo, "He's a hothead, like me. If you get along with most of the press, I think you have to be a little bit crooked." Bobby Knight, coach of the NCAA-champion Indiana basketball team, who has had some problems with the press himself, snorts, "Bad press relations aren't always the coach's fault, you know. You've heard those dumb questions at press conferences. Hell, you've asked some of them." Not surprisingly, these three supercoaches—Woody, Bo and Bobby—account for 84.5% of all problems members of their profession have had with the press.

The whys and wherefores are difficult and always different. "It's because most writers aren't worth a damn," says Bo helpfully. So while some coaches like to go out and drink with sportswriters, Bo would prefer to break out in warts.

Like in 1973, when Ohio State and Michigan both finished the regular season 10-0-1. Even though the Buckeyes had gone to the Rose Bowl the previous year, the Big Ten athletic directors voted to send them again. Bo was more than a little sore. So sore, and so outspoken, in fact, that the conference adopted a coaches' code of conduct and put Bo—actually, put Bo's mouth—on probation for two years. It meant nothing, of course, because the conference would never have disciplined either Hayes or Schembechler, only the other, non-imperial, coaches. Bo never did say he was sorry for his outbursts. "Sorry for what?" he said years later. "Telling the truth?"

Bo Schembechler

After earning his diploma from Miami (Ohio) University, Bo Schembechler earned his master's degree from Ohio State in 1952 while working as a graduate assistant under Woody Hayes.

Schembechler had brief coaching stints as an assistant at Presbyterian College, Bowling Green and Northwestern, but then he returned to Ohio State to work as one of Hayes' most trusted assistants for five seasons.

In 1963, Schembechler received his first head coaching job with Miami (Ohio) University. Over the next six seasons, Schembechler compiled a 40-17-3 record and led the Redskins (now RedHawks) to a pair of MAC titles.

Schembechler became Michigan's 13th head coach -- succeeding Bump Elliot -- following the 1968 season.

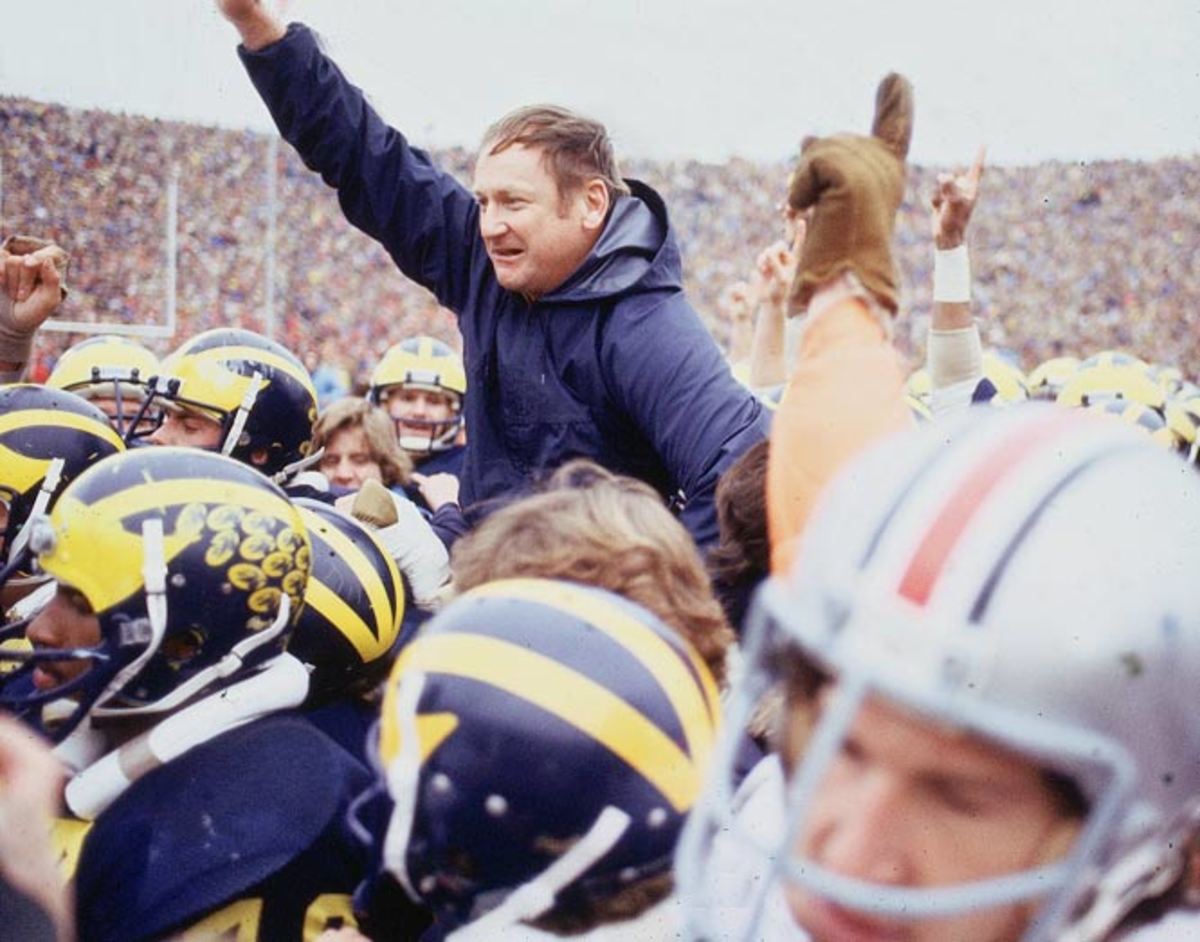

Schembechler may have achieved the biggest win of his career in his first season at the helm of the Wolverines, playing against his former boss Woody Hayes for the first time. Ohio State entered the game as the defending national champs, 17-point favorites and with a No. 1 ranking. At the time, many observers considered the 1969 Ohio State team one of the greatest ever. But Schembechler's 7-2 Wolverines upset Ohio State 24-12.

After Michigan's shocking 1969 win, Schembechler engaged in a "Ten Year War" that took the Michigan-Ohio State game to a new level (many consider it the greatest rivalry in sports). Schembechler held a 5-4-1 edge in the legendary series.

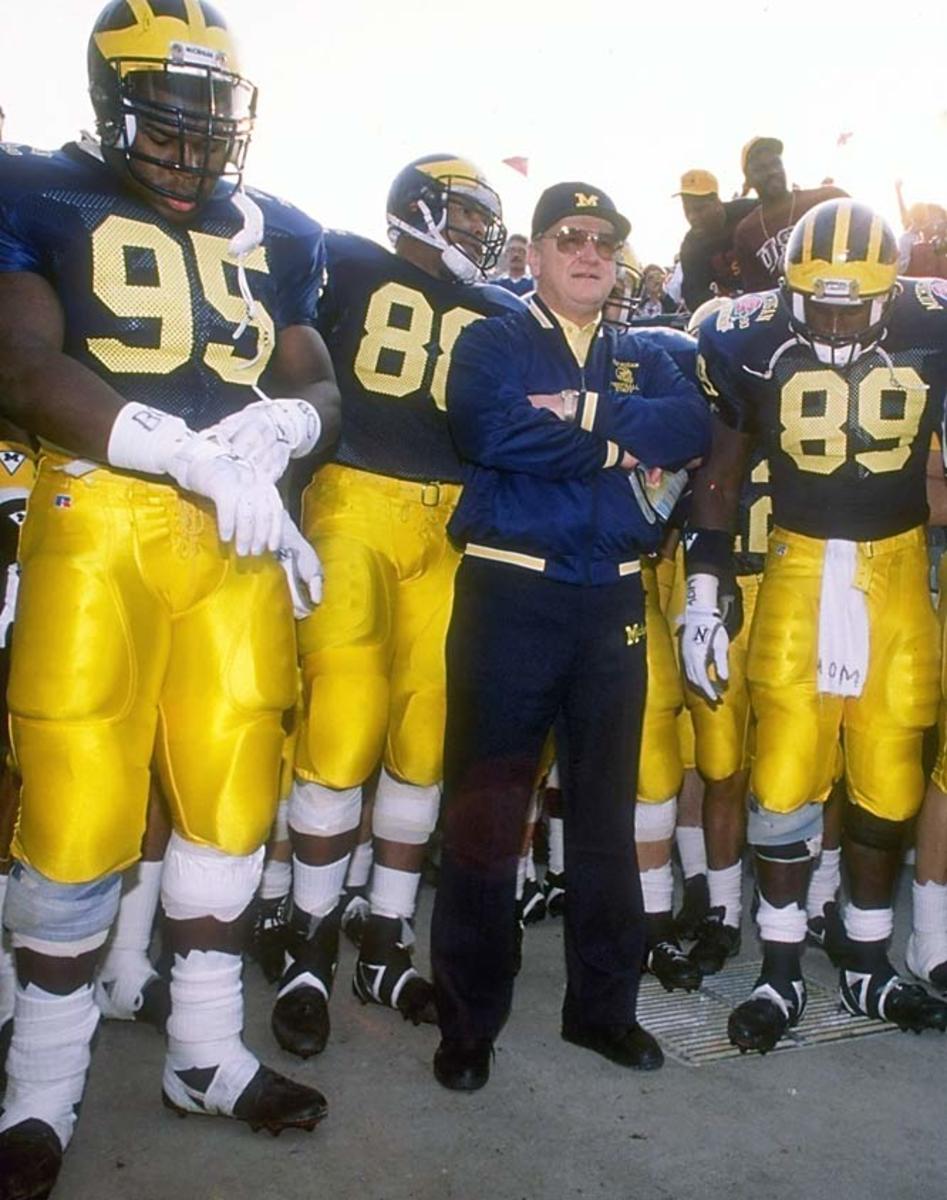

At Michigan, Schembechler recorded a 194-48-5 mark (the school record for wins). His teams won or shared 13 Big Ten titles and made 10 appearances in the Rose Bowl (winning just two). He was named national Coach of the Year in 1969.

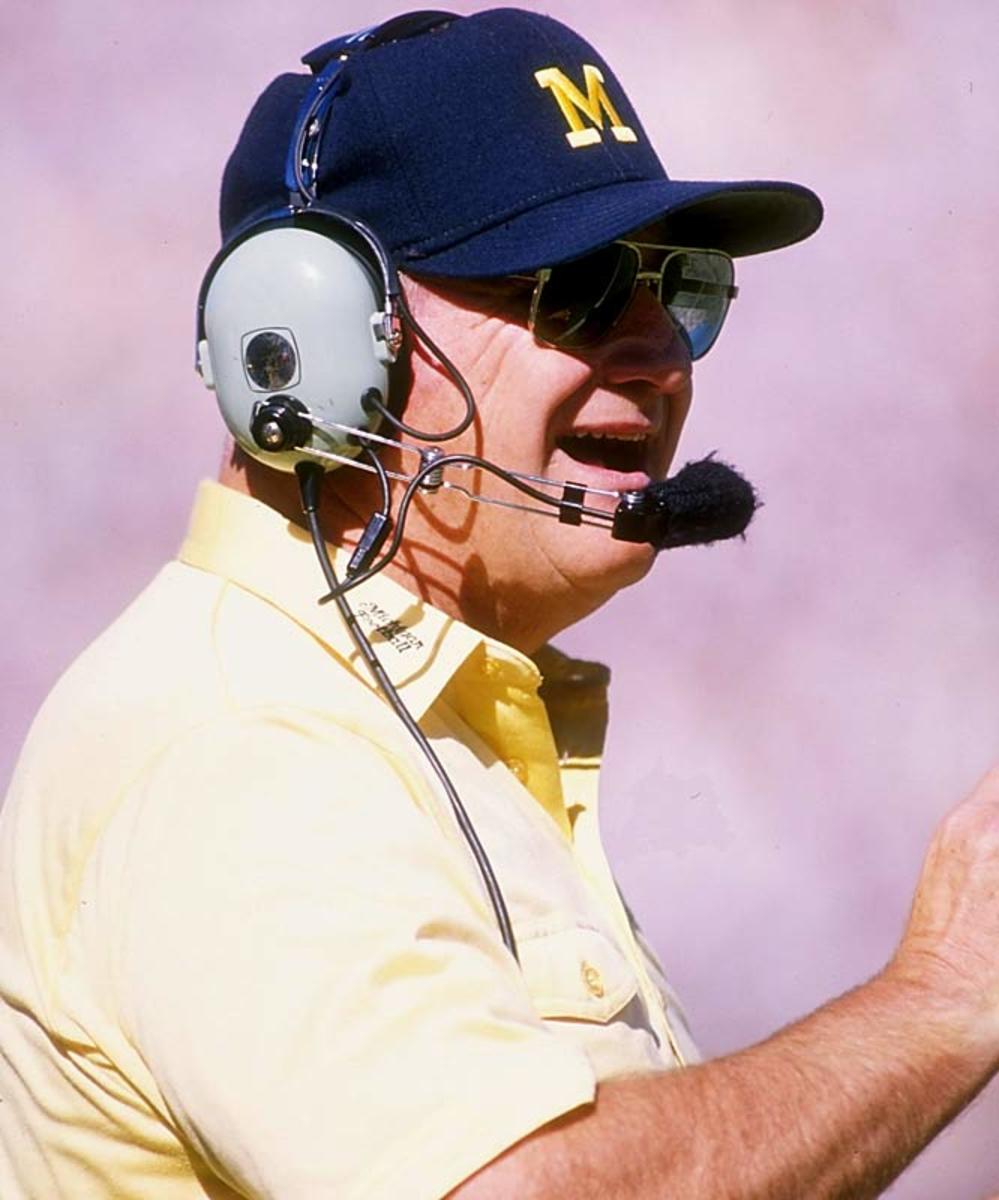

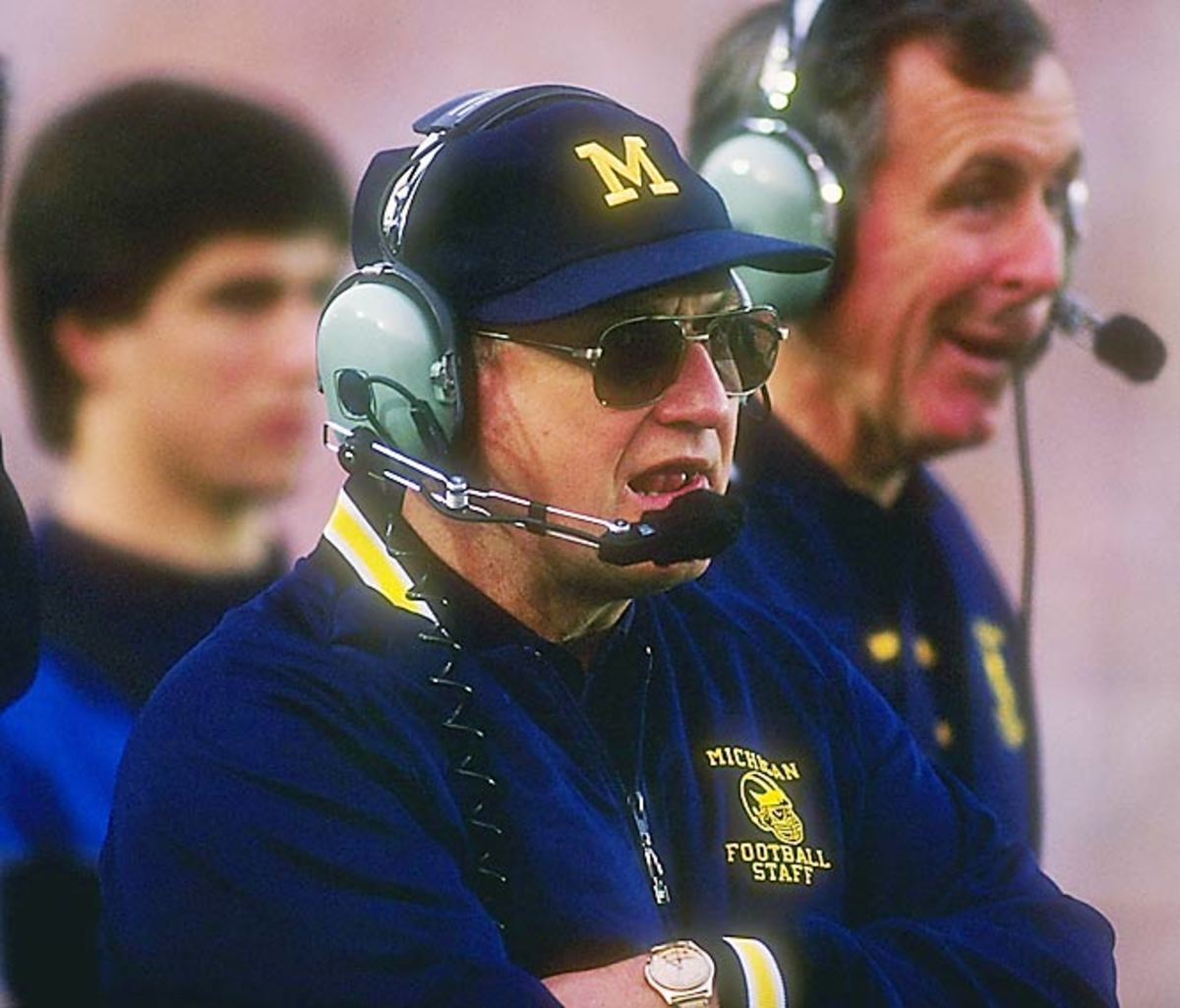

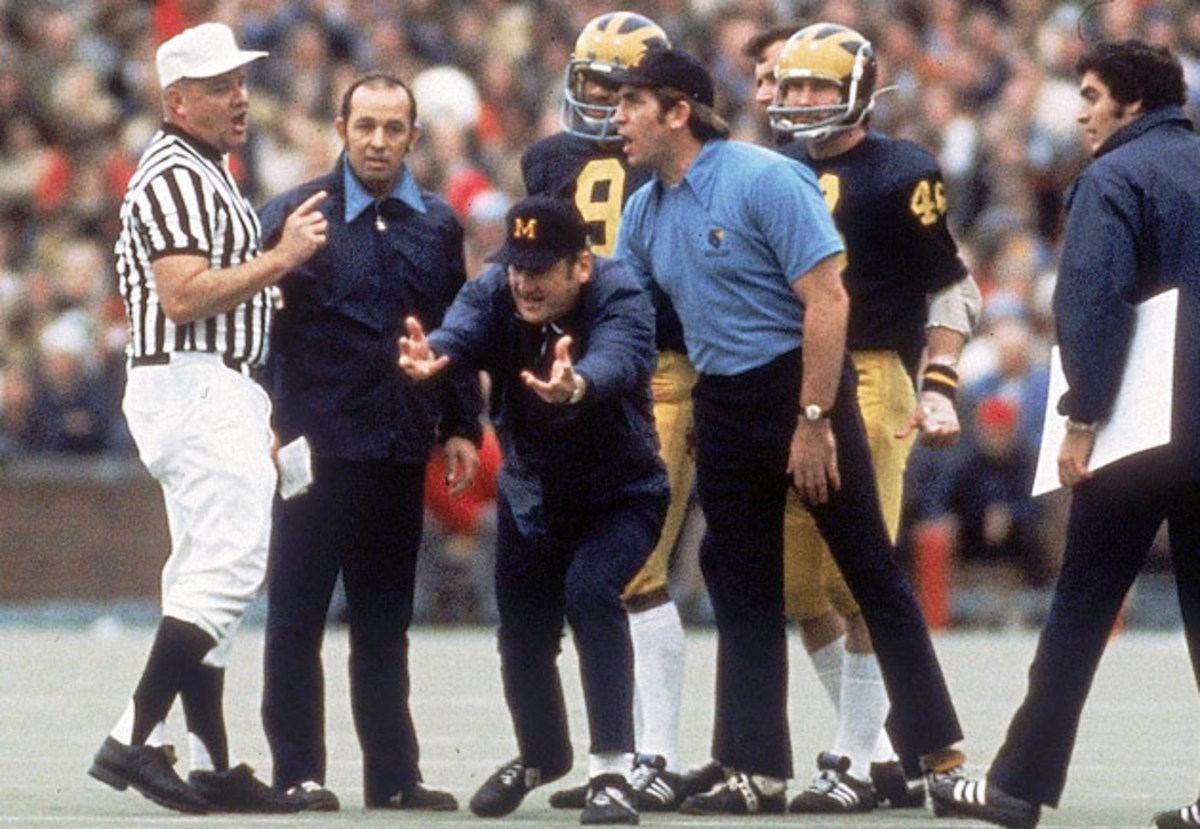

Schembechler was known for his fiery antics on the sidelines. His teams were known for stout defenses and a bruising running game.

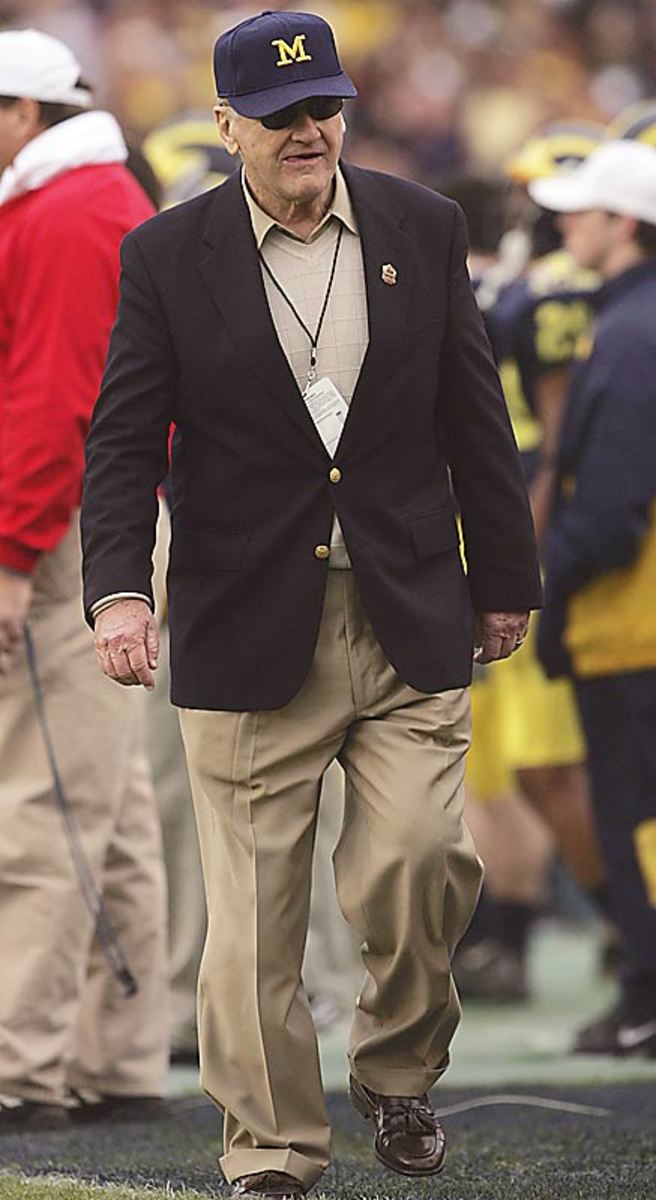

Schembechler served as the Michigan athletic director from 1988 to 1990. From 1990 to 1992 he worked as president of the Detroit Tigers.

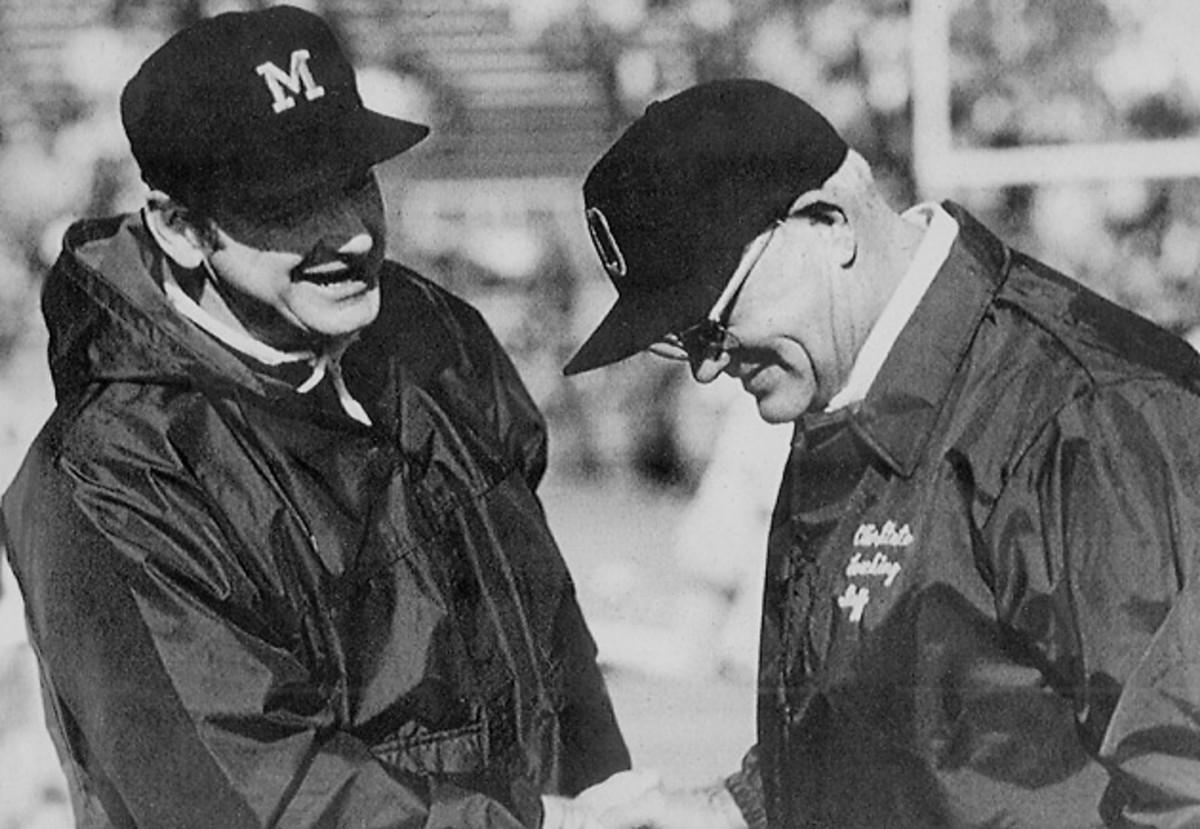

Schembechler, shown here with former Detroit Lions quarterback Joey Harrington, had a well-documented battle with heart disease. He suffered one heart attack on the eve of his first Rose Bowl, in 1970, and another one in 1987. He had two quadruple heart bypass operations. During a hospitalization last month, Schembechler had a device implanted to regulate his heartbeat. He was 77 when he died.

[pagebreak]

Until a couple of years ago, he would routinely storm out of press conferences, kick reporters out of the sessions ("Don't be offended," says one of Bo's friends. "He'd kick Millie out, too"), make himself unavailable and order his players not to talk. Talking very softly once at a press conference, he was asked to speak up. "I'm speaking as loudly as I can," said Bo softly—and arrogantly. And in a memorable set-to on Oct. 1, 1979, Schembechler gave an absolutely unnecessary push to a publicity-seeking college newspaper reporter.

Yet, too much is read into all this. As Don Canham, athletic director at Michigan, says, "Bo is oblivious to life." That, though, is his appeal. The world clearly would be a better place if more people cared as much about their pursuits as Bo does about his. Canham, who had the genius to hire Bo, stretched his feet across the desk the other day and reflected on his coach.

"Bo is a delightful guy with a heck of a sense of humor," said Canham. "He also has a heck of a temper. I guess a lot of people do think of him throwing his hat and kicking dirt and screaming at the officials. But I've found that when he gets mad, it's time to get mad. And while he has a short fuse, he also has a short memory. The only danger with his temper is that he will do something dumb. I don't think he will." Something dumb would be, to give a purely hypothetical illustration, for him to slug an opposing middle guard in the face during a bowl game. But nobody would do that.

Can money, great coach make any team a title contender?; #DearAndy

Former Michigan President Robben Fleming once took Bo out to lunch and asked him, "Do you really have to get on the officials the way you do?" Schembechler had no real response. He says now, "I didn't try to justify it. I think he was right. But the only way I know to get their attention is to yell. How else do you do it? I'm open to ideas."

Canham, a huckster in all the best senses of the word (he has filled Michigan Stadium with an average of 104,186 fans the last 33 games in a row), says his relationship with Bo was established from the start. Just after he had hired Bo, Canham told him, "Schembechler, if we have any trouble, it's going to be your fault—and I'm going to win." Indeed, not long ago Bo appeared in Canham's office, pounding and popping off about some injustice. Canham listened to the ranting and then said, "Schembechler, this is all your fault," and got up and walked out. When Canham returned to his office, Bo was gone and nothing else ever was said about the subject.

But Canham also has one other technique he uses with Bo: "I give him everything he wants." Bo's salary is $60,000, and he earns another $50,000 or so from television and other appearances. But back in 1969 when he started coaching in Ann Arbor, Bo told Millie to buy as fancy a house as she wanted. Heck, go clear on up to $40,000 if need be, he said—a fortune to the Schembechlers then. Millie promptly bought a four-bedroom house for $58,000. Bo groused, "If I don't win, we're in deep and dire trouble." Unlike some coaches who want more than their prowess in the won-lost column warrants, Bo doesn't want much.

Except perfection. Perfection. Put Schembechler in the center of Camelot and he would spot a loose downspout. In 1975, the morning after an unthinkable tie with Baylor, he called in equipment manager Jon Falk. Bo was furious. "Why did Mike Kenn have a jersey with a bad number?" he steamed. A bad number in this case was one that was crinkled instead of smooth.

"I didn't think you would notice," said Falk.

"I notice everything," said Bo. "Now, if you want to manage the goddam equipment, get busy and manage the goddam equipment."

Defensive coordinator Bill McCartney says of Bo, "Nobody calls to excellence more than he does. He forces every guy to measure up every time. He will never turn his head. I've got the feeling he's just reaching his peak." McCartney can even find a Biblical verse in defense of Bo's clamorous tongue. In a well-thumbed Bible, McCartney turns quickly to Proverbs 28:23 and reads, "He who rebukes a man will in the end gain more favor than he who has a flattering tongue."

If that be true, Bo has gained enormous favor. That's because there's no satisfying the man. Walking past the practice field last summer, Schembechler spotted defensive lineman Dave Meredith working out.

"Why don't I ever see you here?" Schembechler asked.

"I'm here four hours a day. What do you want?"

"Oh, six hours, maybe eight."

And Schembechler strolled on. Actually, he would prefer not eight hours, but maybe 10 or 12 or 14. Or, ideally, 24. Just after Schembechler arrived in Ann Arbor, Joe Falls, a Detroit sports columnist, wrote that the coach's idea of a perfect day would be "eight hours of meetings, eight hours of movies and eight hours of practice." Everything Bo does is precise, correct—which is why the prospect of overcooked chicken will worry him so much more than it does the rest of us. These days, for example, when he leaves the office, he goes home; when he leaves home, he goes to the office. At other times of the year, he leaves home, goes recruiting and then comes home. Bo doesn't stop at bars for drinks with the boys.

Obviously, when you're a winner like Bo, there are plenty of people who want to be your friend. But Bo doesn't really want friends. Or, more precisely, a few friends might be O.K., but he doesn't have time for them. Or, more precisely, doesn't want to have time for them. Over the July 4 weekend, he and Millie did get away for a few days to visit some friends on Indiana's Lake Wawasee, but he wasn't all that keen on going. Right before leaving, he went back and picked up something to take with him "just in case." It was the film of last year's Wisconsin-Michigan State game. "You never know," he said. "It might rain." As it turned out, it didn't rain, but he did study the film. Got it?

Bo's best friend is Joe Hayden, chairman of the board of The Midland Company in Cincinnati. Their friendship also involves business deals. Says Hayden, "Bo doesn't go out of his way to seek close friends. But the image he projects is so different from how he really is. He's well-rounded, and I don't mean his physique. I don't know why he keeps coaching, other than the thrill of the hunt, but I do know that one time I told him, 'As long as you get up in the morning and are in a hurry to get to work, you've got the right job.' Bo smiled and said, 'I've still got the right job.'"

Just before his quadruple bypass surgery in 1976, Bo called Hayden from the hospital. "Joe, is everything O.K. for Millie and the kids [there are four sons, ranging in age from 11 to 26] in case of, uh, stark disaster?"

"What do you mean, stark disaster?"

"You dumb son of a bitch. If something in there stops going ticky tick, it's stark disaster for Glenn Schembechler."

"It's all O.K."

"Good. Goodbye."

[pagebreak]

Schembechler will on rare occasions make an attack on relaxing and watch a video cassette of a movie on his television at home, sometimes with Falk. One night this summer was typical of the way things generally go. Falk picked up a selection of films for Bo's approval. Over dinner at Bimbo's Casa Di Roma—where for a guy who makes important snap decisions on everything, Bo sure had a helluva time trying to decide whether to have meatballs or Italian sausage on his spaghetti—he also was deciding which film they would watch that evening. Caddyshack was a candidate because it lasted less than two hours. Urban Cowboy was out because it had that Travolta character in it. Heaven Can Wait involved football, so that was nixed—this was to be relaxation. Falk lobbied for Being There. The clerk at the tape store had made a sneering reference to Michigan's sometimes less than exciting brand of football when he said of Being There, "It's kind of dull for the first 15 minutes, but Bo ought to be used to that." Being There was selected. Bo promptly went to sleep in his recliner during the first five minutes of the film, awoke at its end, and said "That is the worst movie I've ever seen." Got it?

Yet—in this bit of an example of the new Bo—he felt he should watch the movie, though not so deep down inside that he wouldn't much rather have watched game films. By himself. Still, he wanted to be hospitable, and he knew that's what he should do. But he couldn't resist asking a visitor at one point, "How long are you going to stay around here?" The visitor said, "About three months, and then I'll go home and get clean clothes and be back." Schembechler doubled over in laughter. He's trying to be more human, honest, but damn, it's hard. Millie does give him pretty good marks in this endeavor. She says, "He has had so much success that now he knows what he has to get done and that he can do it by being nice to people."

Way-too-early breakdown of 10 intriguing nonconference matchups

So much success. Ahhhhh, yes. "Schembechler," says Bobby Knight, "is the best coach coaching anything in college sports." Southern California coach John Robinson, a Bo buddy, says, "I'd love to have a son play for him. He'd come out of there a much better person." Jerry Ford says, "He's a helluva man, isn't he? The two things I think of with Bo are strength and success. And then, underneath the surface is a very, very compassionate man." Woody Hayes professes great admiration, although he does add softly, "Bo is the second best in the country. I have to say the first is that old man down at Alabama."

Bo wins, wins, wins, 88.8% of the time in the Big Ten. Eleven of his 12 Michigan teams have ended the season ranked in the nation's top 10. During the 1970s, the Wolverines were 96-10-3 in the regular season, best of any team in the country. For the same decade, the Wolverines were also first in rushing defense, first in total defense, first in scoring defense. Indeed, bringing the story up to date, nobody has scored a touchdown against the Michigan defense in 22 quarters. Schembechler's record of 154-38-6 in 18 years as a head coach, including five at Miami of Ohio, gives him the fourth-best winning percentage among all active coaches, behind Barry Switzer, Robinson and Joe Paterno.

One oft-repeated knock on Bo is that he doesn't pass. In truth, he has, and for sure he will this year with Anthony Carter, a certified game-breaker at wide receiver, on the loose. But quarterback coach Gary Moeller explains the Bo philosophy thusly: "You run the ball first, and if you are successful, you keep running it." Michigan has been successful running, and as Robinson notes, "Passing teams generally don't win." Further, Dan Devine says, accurately, "Every winning coach has been called too conservative."

Probably contributing most to this year's sunny outlook is the fact that Michigan at last won a Rose Bowl, whipping Washington last January, 23–6, after seven straight bowl losses. Former Notre Dame coach Ara Parseghian thinks the notion that Bo couldn't win the big one was a bum rap. "Most guys don't ever get in position to play in the big one," says Parseghian. "Just getting there is a big accomplishment." Still, not winning The Big One cast a pall over Bo—you can ignore the fact he says it didn't, got it?—all these years. Defensive coordinator McCartney says, "Bo's solution to everything is to work harder. We worked harder, but we kept losing the bowl games, and the people of Michigan became so exasperated with us."

There were always reasons and excuses, but Michigan kept getting beat. "How I feel about losing depends on how I lose," says Schembechler. "If we were just not good enough, fine." But Bo can think of only one time his team wasn't good enough—in the 1976 Orange Bowl, when the Wolverines lost to Oklahoma 14–6. And he thinks he should have won that game. "Anytime you get within a touchdown, you're good enough to win," he says. Perhaps the importance of the ‘81 Rose win is best illustrated by the positioning of a team picture celebrating the win. It's right by the door of Bo's office. You can't leave without seeing it, unless you choose to go out the window. And Bo can have that effect on people.

Now Bo has won everything in coaching—conference titles, a bowl game, Coach of the Year (1969)—except a national championship. You can ignore the fact that Bo says it's not important, got it? Parseghian, who goes way back with Bo and had him on his staff at Northwestern, says, "Sure it bothers him, just as it bothers Paterno. They have both been so close, but it has escaped them."

That's why the Sept. 19 game against Notre Dame in Ann Arbor looms so big. "It's the biggest nonconference game on our schedule," says Bo, which, taken at face value, means that later games with Northwestern and Illinois are bigger. And bears don't live in the woods. What the Notre Dame game really is, is the biggest game of Bo's career. Indeed, Schembechler is at the helm of an extremely talented team, and this would seem to be the year. But Notre Dame is a tough nut, with outstanding players recruited by former coach Devine and guided by the new, fiery Gerry Faust. At his ease during the summer, Bo laughed about a conversation he'd had with the irrepressibly religious Faust. "He even God-blessed me," said Bo.

But Bo's jesting was probably a defense mechanism. He is steadfast in his contention that "I don't lust after national championships; I lust after Big Ten championships." And to underscore that point, he insists that ridding himself of the Rose Bowl-loser image last year was a tremendous relief, but after the victory he still felt there "was nothing like beating Ohio State."

Ohio State and Michigan are always linked because for years they've been the only schools in the conference that have played superior football. Further, the Woody-Bo Show made that annual confrontation bigger than life. Perhaps too big, because—as in the Super Bowl and a few other spectacles—the players were so on edge that their performances weren't always splendid. Only now, with Woody three years out of coaching, is Bo emerging as his own man after a near lifetime of being linked with Hayes.

[pagebreak]

It all traces back to Miami of Ohio, where Bo played for Woody. At a reunion of Miami players last summer, Hayes recalled a 28–0 victory he coached over Cincinnati in 1950. "We scored four touchdowns," he said, "and would have had five if a certain overeager tackle hadn't been offsides." That tackle was Schembechler. But once you have played for a coach, he's always the coach and you're always the player. At this same reunion. Hayes was organizing things—surprise—and suddenly looked over at Bo standing across the way. "Bo," he said, "you sit right here." Bo sat. And one suspects that if Woody had said, "Bo, run through that wall," Schembechler would have done that, too, without question.

Bo was an assistant under Hayes at Ohio State in 1951 and then again from ‘58 to ‘62. They were, although both vigorously deny it, two damn peas in a damn pod. In football meeting rooms, they even threw chairs at each other.

"No, no," says Hayes when asked about the flying furniture. "We just argued to beat hell."

But you didn't throw chairs at each other?

"No. no. We just got damn mad."

But you didn't throw chairs at each other?

"Oh, well, sometimes we threw chairs... but not at each other."

Just sort of a case in which the two of you were in the same room when chairs were thrown?

"Yeah, that's right."

So what's the big deal? Of course they threw chairs at each other. Why wouldn't they? Don't bulls lock horns in the field? Since his days as an assistant Bo's been called "Little Woody." And there were distressing signs that the nickname fit. In fact, Dick Larkins, the former Ohio State athletic director, once advised Canham, "Don't hire Schembechler. You'll end up with him just like we have with Woody. You'll never be comfortable with him." But Woody would tear up yard markers; Bo didn't. Woody hit a TV cameraman; Bo didn't. Woody hit an opposing player; Bo didn't. A Bo watcher says, "I think he was learning something all along. He thought, and thinks, that Woody was a great coach, but he was telling himself not to copy some of the old man's mannerisms."

To this day. Schembechler speaks of Hayes with reverence. "I'm a Woody Hayes man," he says. "I believe in him. I respect him, and I always will." Indeed, after Hayes' slugging of the Clemson player in the Gator Bowl, Bo arranged a meeting with his mentor/rival at a midway point between Columbus and Ann Arbor. He hoped to get Hayes to apologize publicly. Sadly, Bo at his most persuasive couldn't get Woody at his most stubborn to say those two little words that would have made all the difference: "I'm sorry." Subsequently, Woody admitted to the conversation, but snorted, "Bo isn't always right."

Hayes and Schembechler were, then, the greatest of friends and the bitterest of rivals. They loved each other and they hated each other. They were a study in contradictions. "We respected one another so damn much," says Hayes. "Now that doesn't mean I didn't get so mad at him that I wanted to kick him in the, uh, groin." And for his part, Schembechler says, "You beat Woody and you beat the best. It's always best to beat the coach you have the most respect for."

The fact is, Schembechler is emerging now as King of the Mountain only because Woody is gone. Never mind that in the 10 games in which the two faced each other. Bo's teams won five, Hayes's four, and they tied once. Bo was Little Woody, got it? But that was yesterday.

Today Bo—he will deny this, too—is enjoying life a little more. He's stopping to smell the roses. His heart attack and the subsequent bypass may have put things in perspective. He yammers incessantly to his players about the value of education, but he has learned to kid them a little.

The phone rings and it's defensive tackle Winfred Carraway. "Wouldn't you like to work around here for $4 an hour?" Bo asks. "Why not? What? Well, until you get a degree, $4 an hour is all you're worth. How are your grades? Come on. if you got all A's and B's, you coach and I'll play defensive tackle."

His other favorite theme is honesty. He talks constantly about his honesty and that of Michigan, especially in regard to recruiting. Indeed, there has never been a hint of scandal or irregularity since Bo came to Michigan. "There won't be, either," he says.

What Bo really likes is to be out on the field with the players and to talk on the phone with other coaches. The nuts and bolts of the profession are his loves. One of his assistant coaches, Jerry Hanlon, says, "Bo is learning to live with imperfections. So he enjoys being around his staff, he really does. A lot of us think he calls meetings just for that purpose, to be with us." Says quarterback coach Moeller. "Bo understands that the bad part about coaching is if you don't win, you won't be coaching." And that would be awful, for Bo simply loves coaching, got it?

Sitting in his family room one evening (on the wall is a cartoon of a wife who has just bashed her husband over the head with a frying pan, and she's telling the police, "When he said he had the whole football season on videotape, something inside me snapped"), Bo was feeling reflective. "I love to win," he said. "Love it. Football is just too hard and too tough if you're not successful. This isn't recreation, and the sport isn't for everybody. Soccer is a great game, too; it's just that by junior high, it's time to play football. Anyway, I just don't want to expend all this time and effort and come up short, got it? I love college because you have to make do with what you've got. I may want a better player, but I can't trade for one or pick up a free agent, so I'll coach the hell out of the guy because he has to play—and because he's mine. Sure, I know I've got a lousy temper, but sometimes it can make you compete better. But I'm smart enough to know you have to learn to control it. It's just when things aren't right, I react aggressively. And I'm a disciplinarian. At meetings, the players sit up straight, have both feet on the floor and don't wear any hats. They get in early at night, too. Why shouldn't they? You tell me—does anything good ever happen after 11 p.m.? I guess my philosophy is I want to do what I'm doing better than anyone else in the country. But the problem is I'm just an average guy, got it? But aren't we all? What I've learned is there are not nearly as many bad guys or super guys out there as you think. Just a bunch of average guys." He falls silent, thinking. A penny for your thoughts, Bo.

Because he loves the boys and the good old boys (former quarterback John Wangler says, "Once you're a part of Michigan football, he makes sure you always are. The older you get, the more you appreciate Bo"), he loves the good old stories. He tells of Carter showing up as a freshman and one of the coaches marveling, "My God, look at him run and catch." Later that same day, Carter ran and caught a plane back home to Riviera Beach, Fla. Bo caught up with him by phone. "I didn't think he was gone for good," Bo says. "He just needed to go home for a little reinforcement from his family and friends. And the reinforcement he got was, 'Get your ass back up there right now.'" Carter did.

From this shaky beginning, Bo and Carter have developed a close relationship. That's mostly because Schembechler is in awe of Carter's talents. "I just don't know what else I can say about him, got it?" says Bo.

That's understandable. Just about one of every three passes Carter catches goes for a touchdown (21 TDs in 68 receptions in only two years). He was the first Michigan sophomore since 1925 to be named an All-America; he's the first Michigan sophomore ever voted MVP by his teammates. Indeed there is increasing speculation that Carter, a junior this season (Bo calls him "the finest receiver in the nation"), may turn out to be the best player Michigan has ever had.

Carter generally escapes Bo's acerbic tongue—and even Millie finds that remarkable. "He gets on me sometimes," says Carter, "but the other players say he gets on them more." That's probably true because when you meet Bo's standard of perfection, you have just exceeded the world standard, and therefore it's time for the screaming to stop. "It has been a great pleasure to play for Bo," says Carter.

Schembechler sees the qualities he admires most surfacing every day in Carter. His attitude is superior, he's single-minded, he's great in practice, he's interested in team rather than personal goals, he's fast, he's tough, his hands are terrific, he keeps his mouth shut and, most of all, he's Bo's. "Nobody can allow Carter to have single coverage," says Schembechler. He smiles when he says that, because teams must sometimes allow Anthony single coverage, or some other Wolverine, left unattended, will do them in.

Thus both coach and player know better than anyone that Carter is the heart and, more important, the soul of this football team. With such responsibility, it's no surprise that Carter chooses his words carefully when asked to evaluate Michigan's chances. "I hope we'll be able to compete," he says.

Former players often drop by to see Bo, and he makes time for each of them. "All the players embellish the hell out of the stories," says Schembechler. "They say I was the toughest, meanest bastard that ever lived. I know that isn't true."

Yet Bo inspires extravagant tales because he can be so outrageous and because he is sooooooo competitive. Former linebacker Mel Owens, No. 1 draft pick last spring of the L.A. Rams, shakes his head and says, "Every day Bo is fired up, every day. He's feisty and he goes after it." Once, on a quiet social outing, Bo and two other guys climbed on bikes for a peaceful ride through the countryside. No sooner was everybody rolling than Bo said, "Let's race." Another time, on Canham's boat for a pleasure cruise on Lake Erie, everybody was relaxed except Bo, who was trying to make sure the boat was exactly on course. Never mind that nobody had a course planned.

And Bo can now laugh at himself, which he does, recalling the night before the 1975 Northwestern game. Northwestern is a college football power on the order of most any high school you'd care to name. Sitting in his hotel room looking at films, Bo suddenly bolted upright. "Goddam, Northwestern is good and we aren't ready," he said. "I am sitting on an upset." Whereupon he raged through the hotel, clicking off TVs, screaming, berating, threatening, kicking ass and taking names. He finally returned to his hotel room, spent. Next day, Michigan won 69–0. Got it?

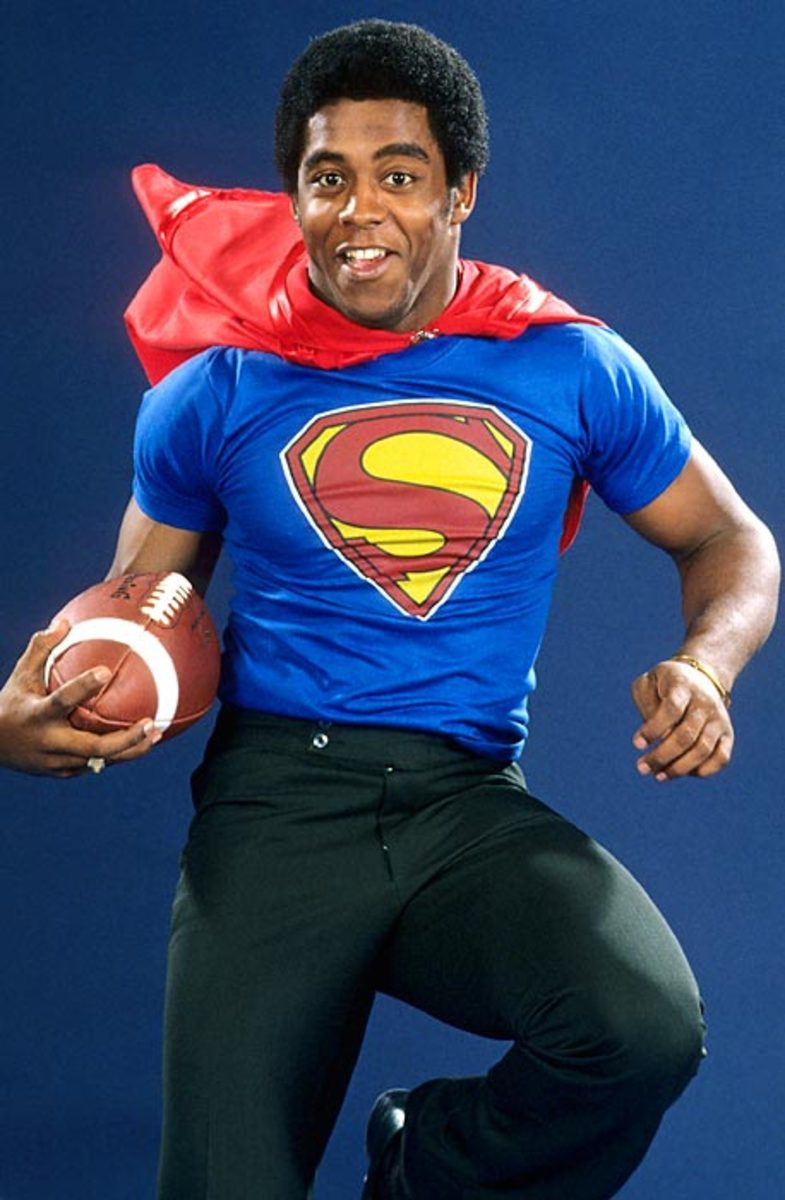

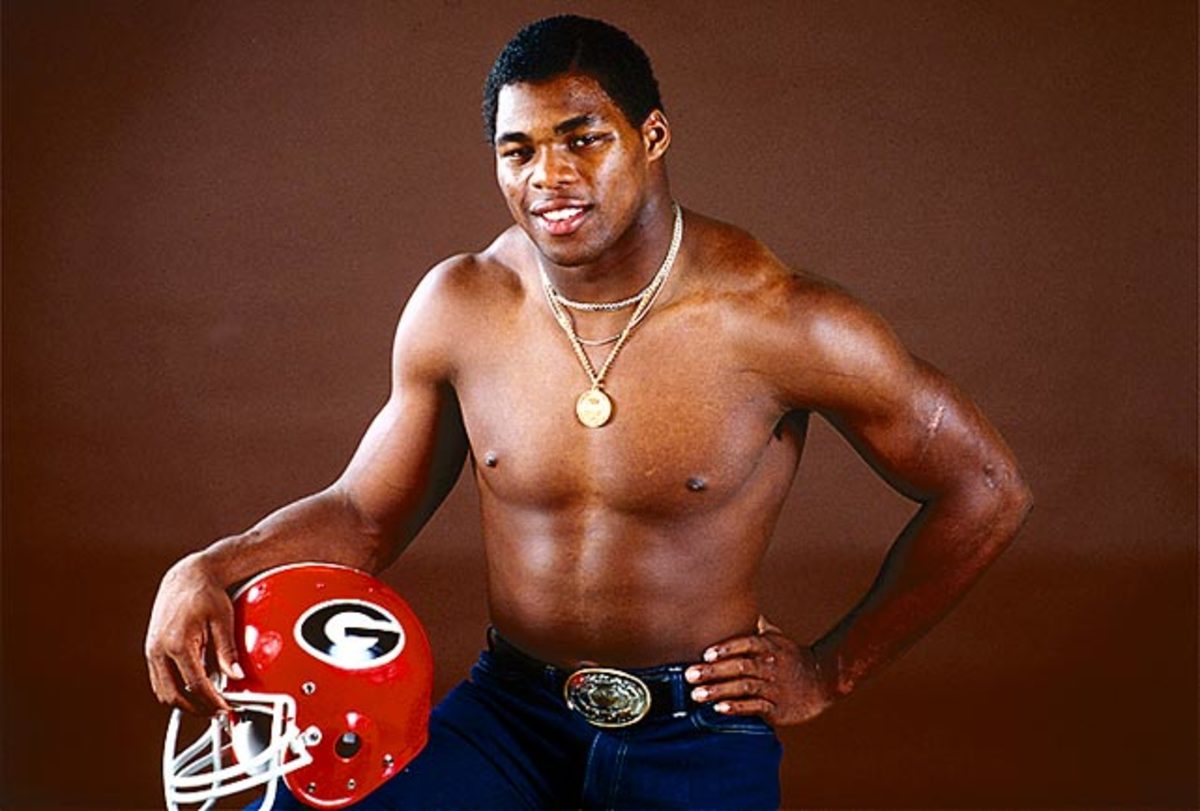

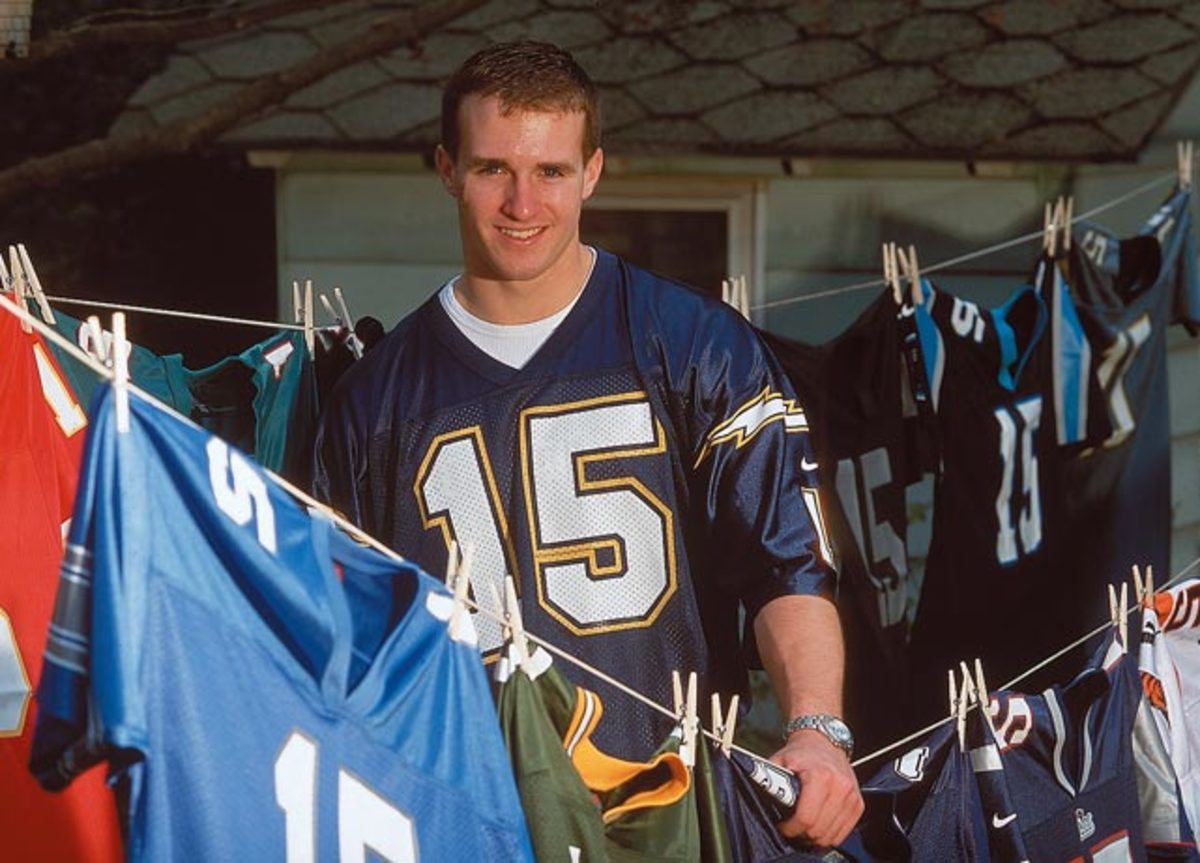

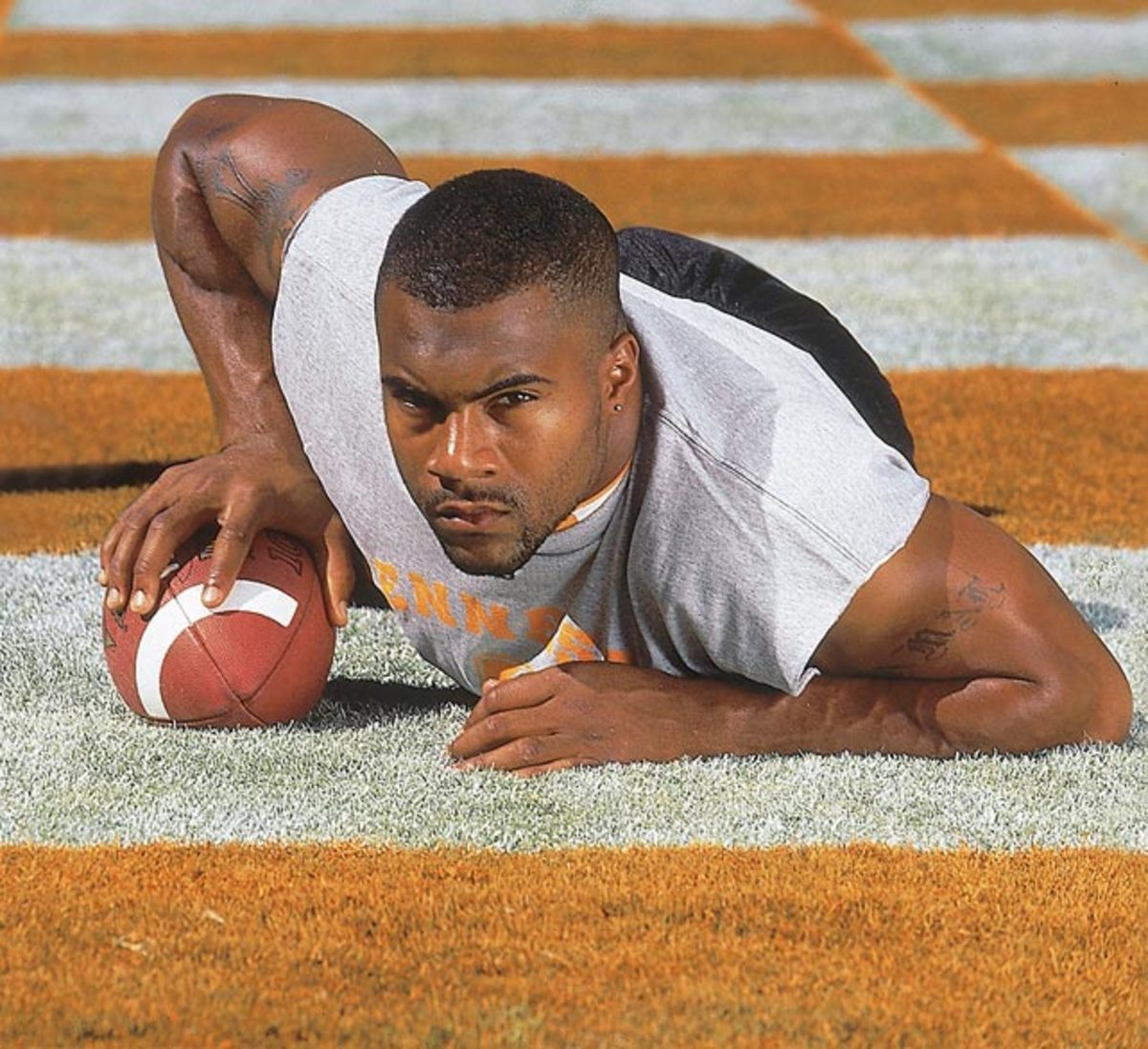

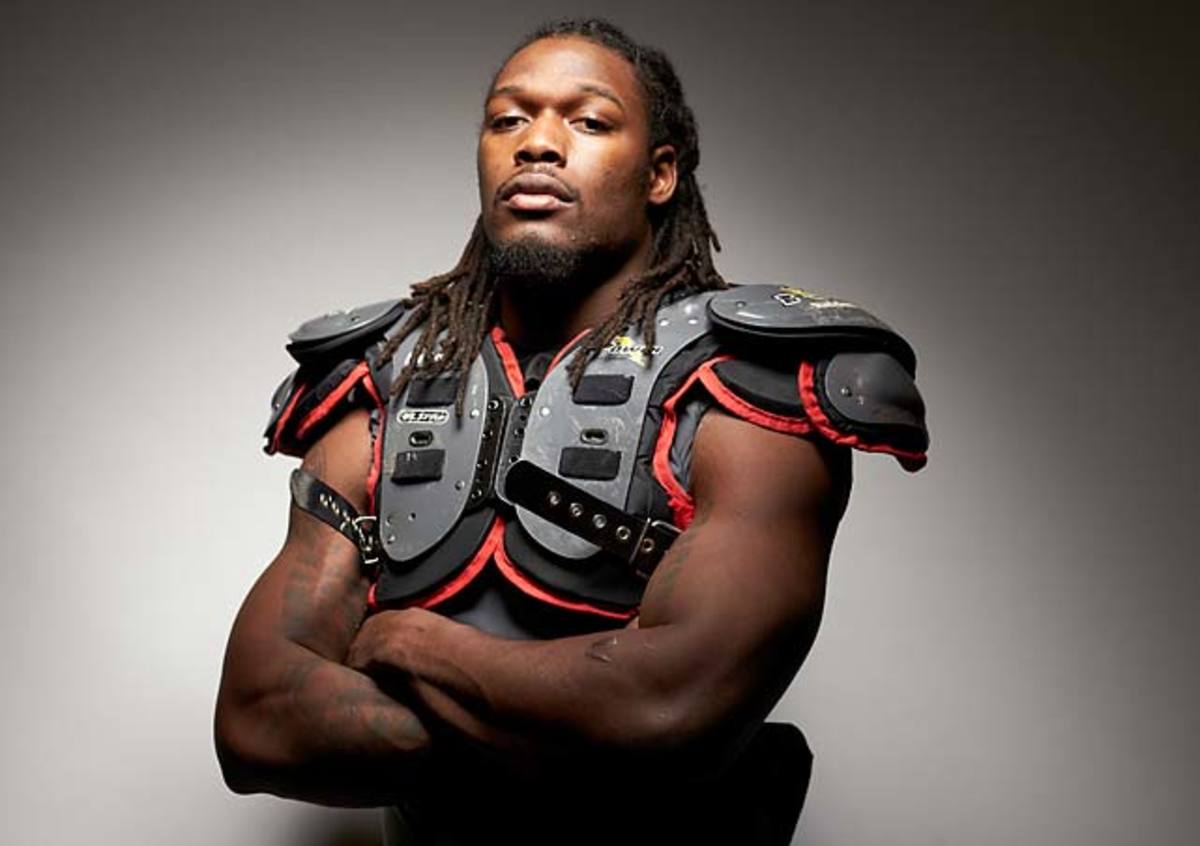

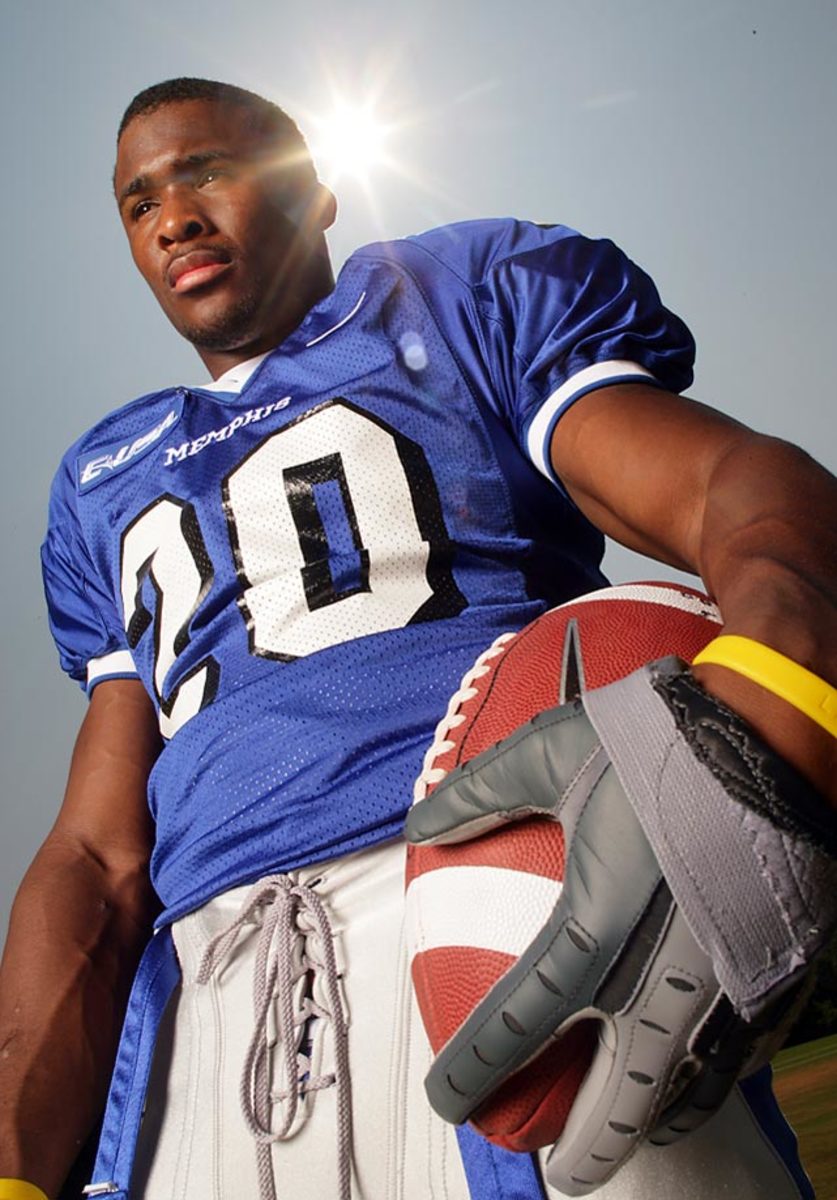

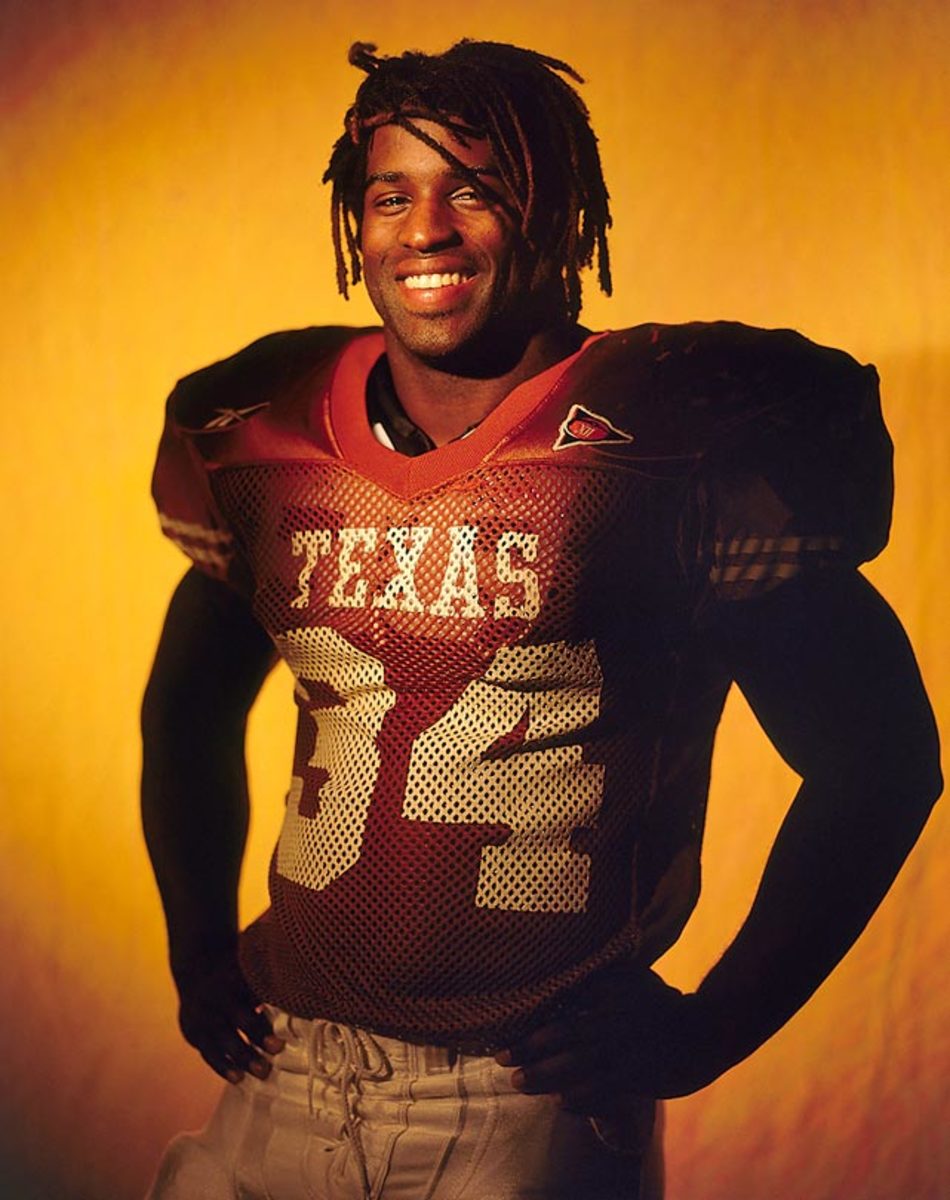

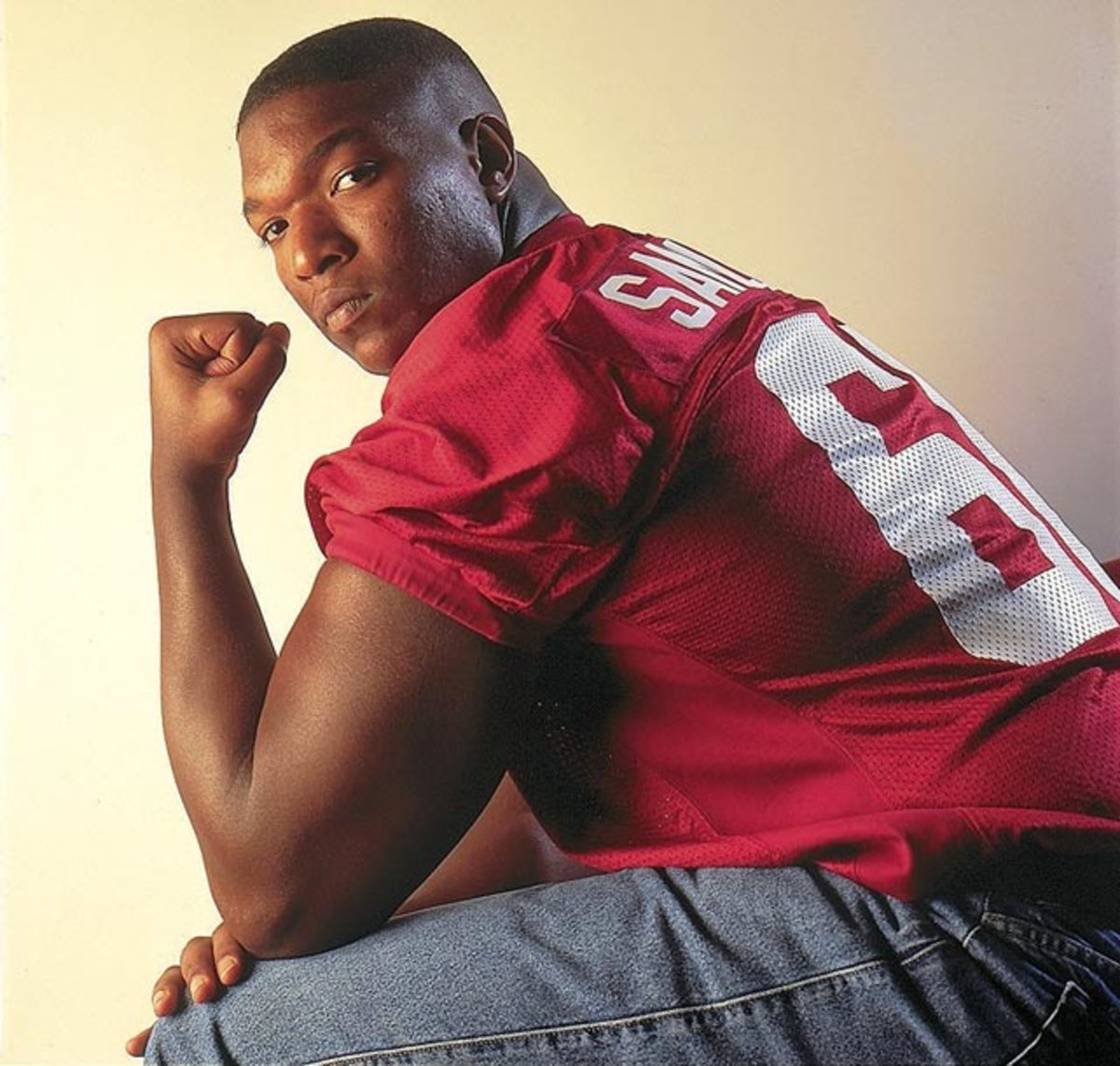

SI's College Football Portraits

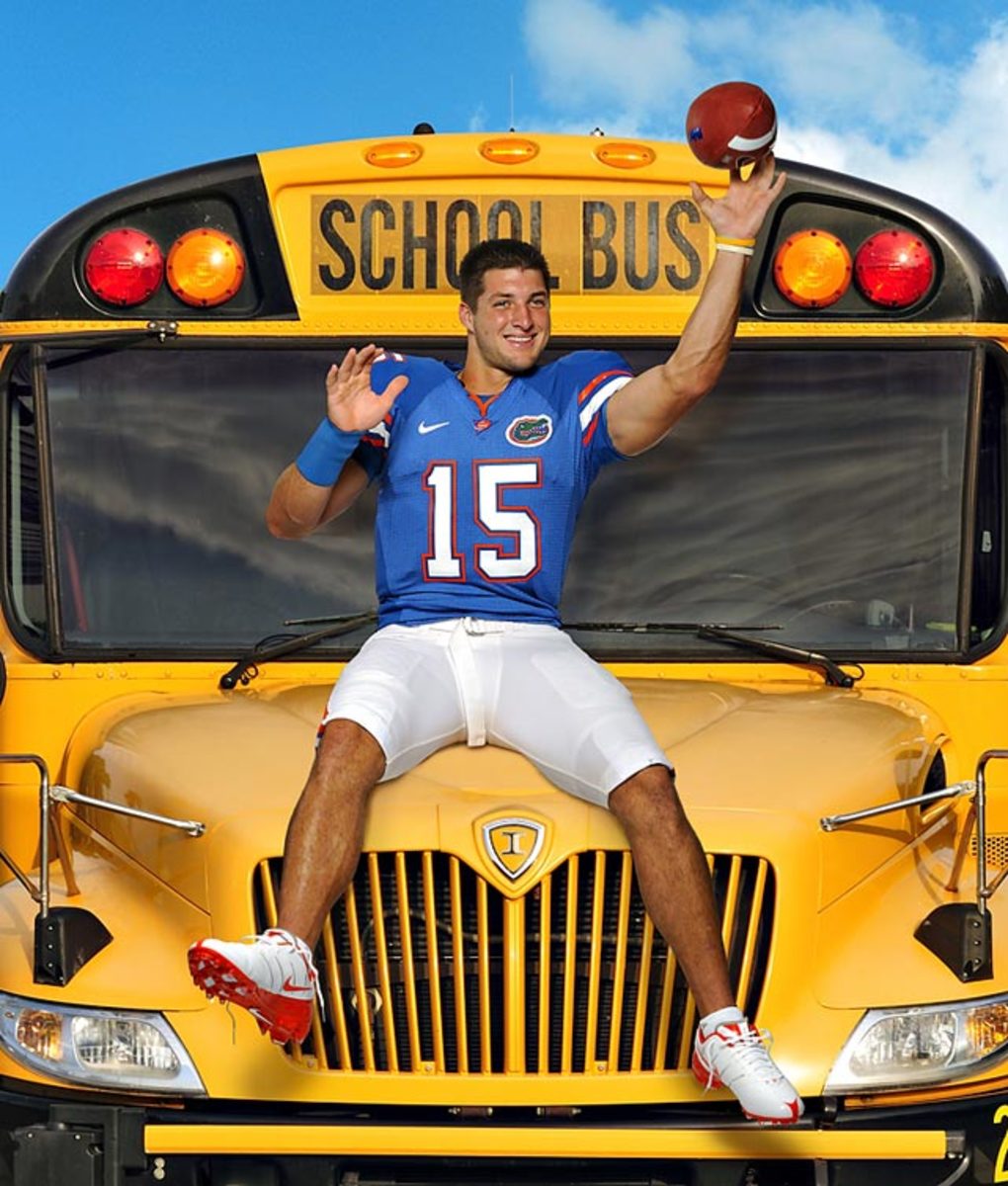

Tim Tebow

USC offensive players in 1972

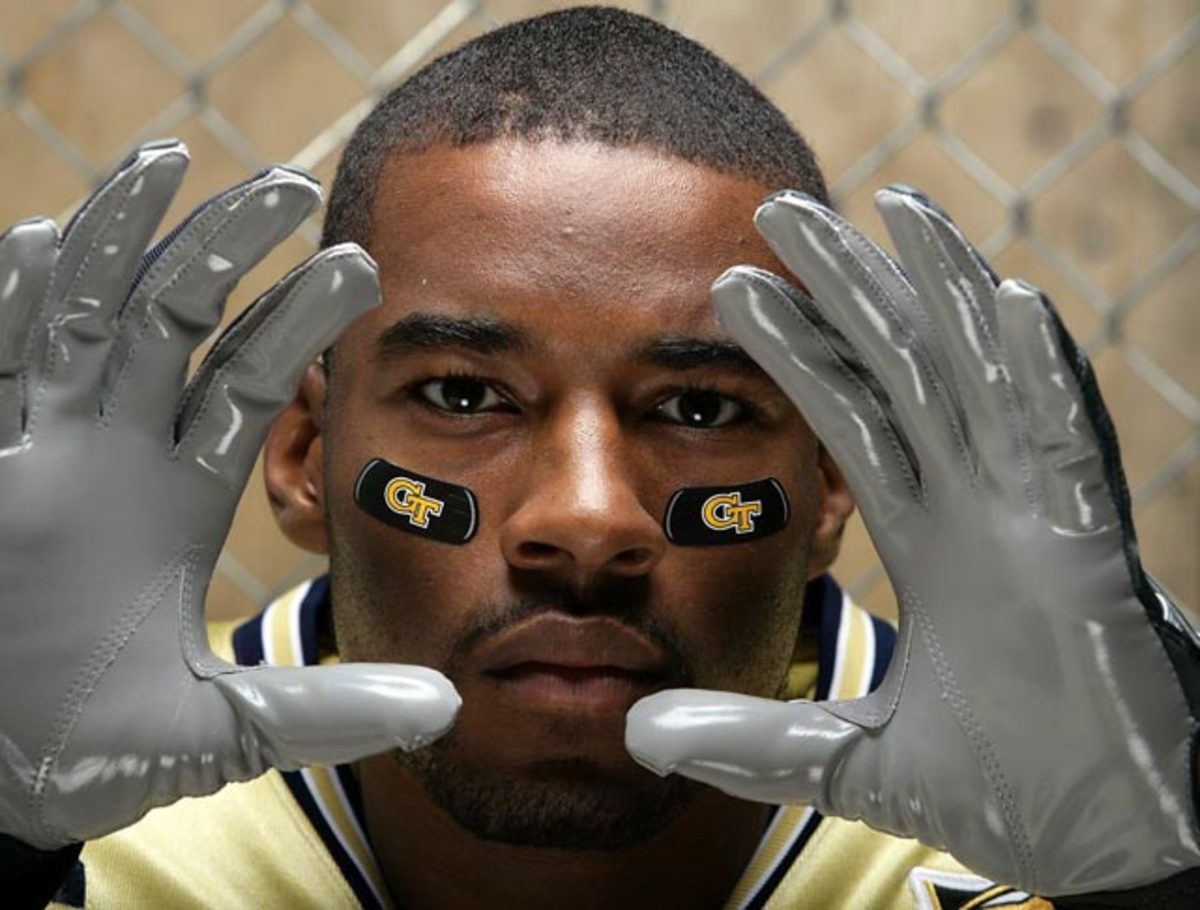

Calvin Johnson

SI's college football portraits over the years.

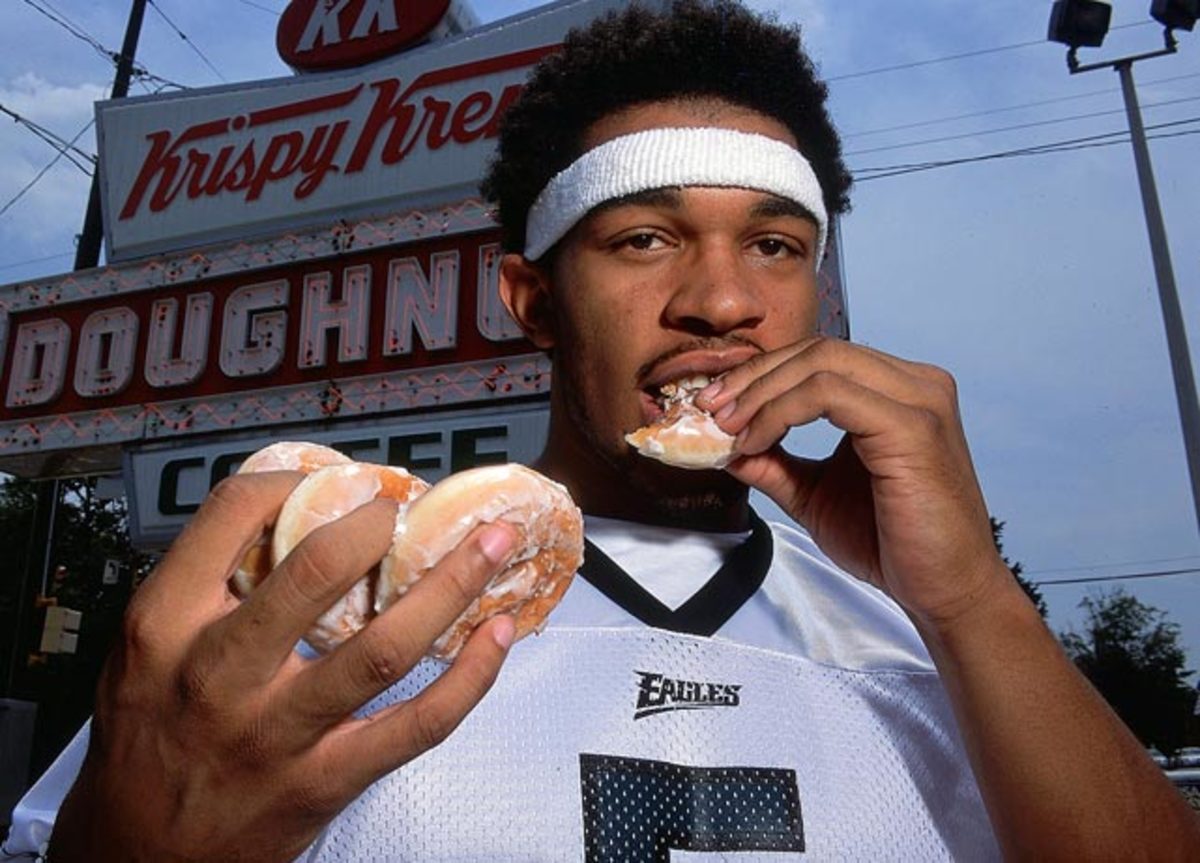

Julius Pepper

Tony Dorsett

Bobby Bowden

Hershel Walker

Drew Brees

Jamal Lewis

Keyshawn Johnson

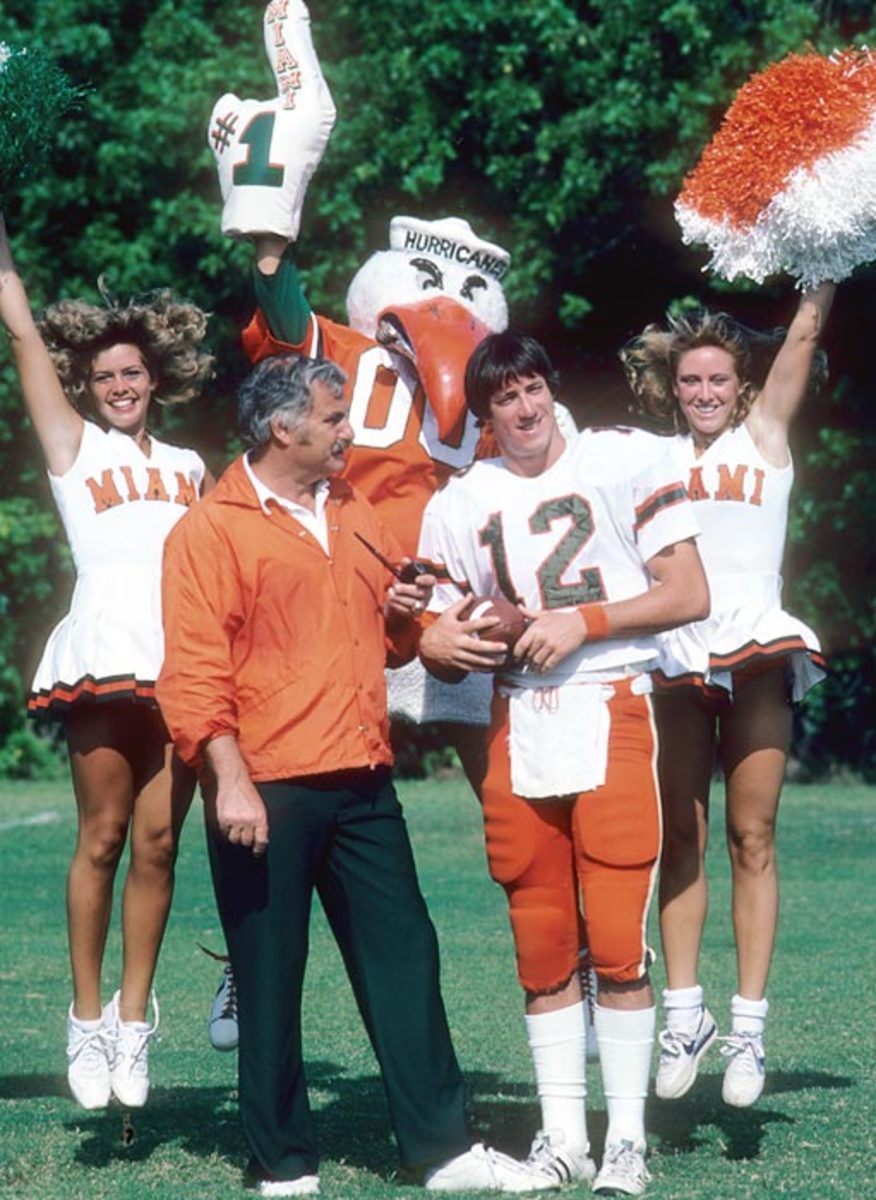

Dan Marino

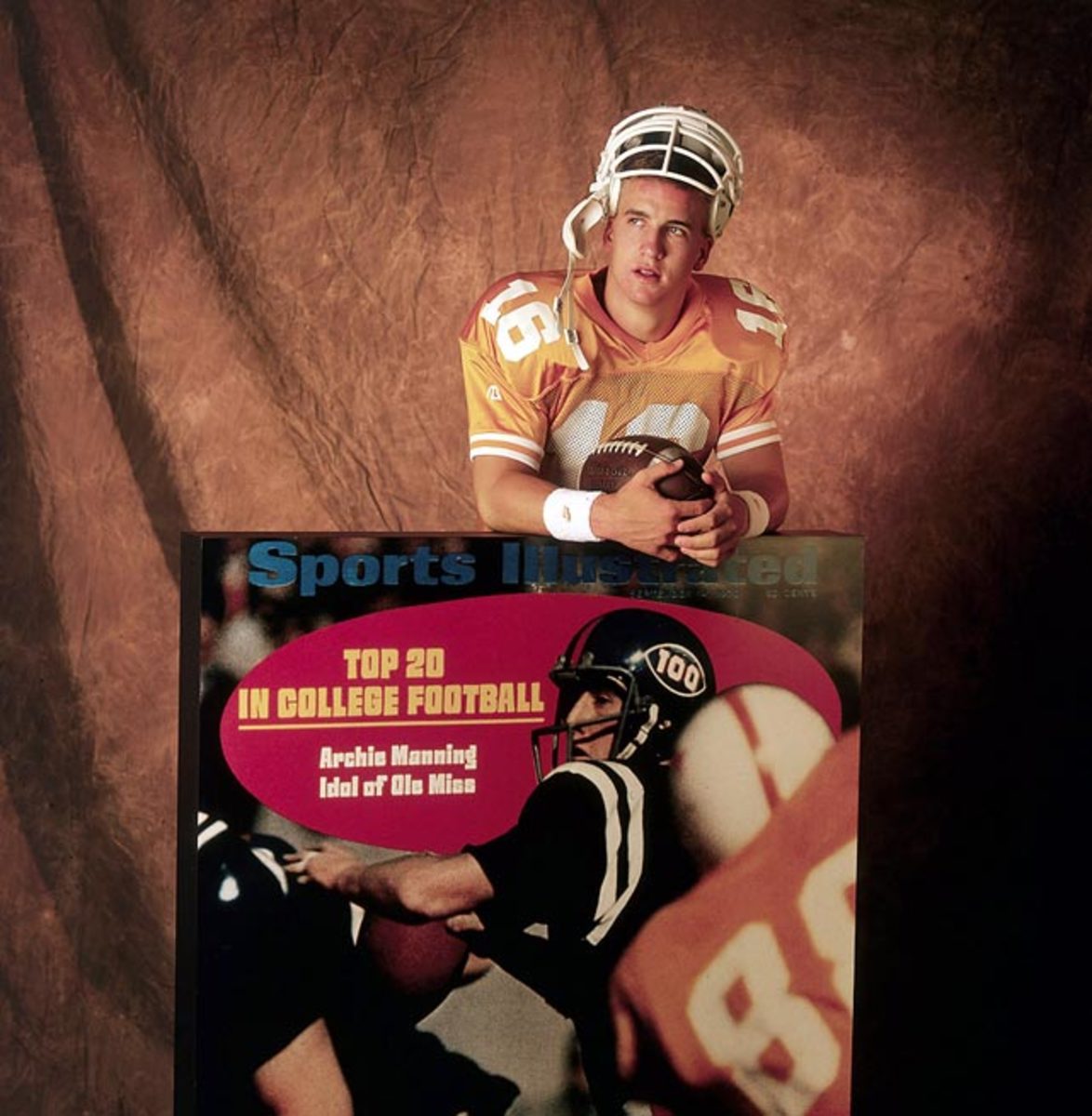

Eli, Cooper and Peyton Manning

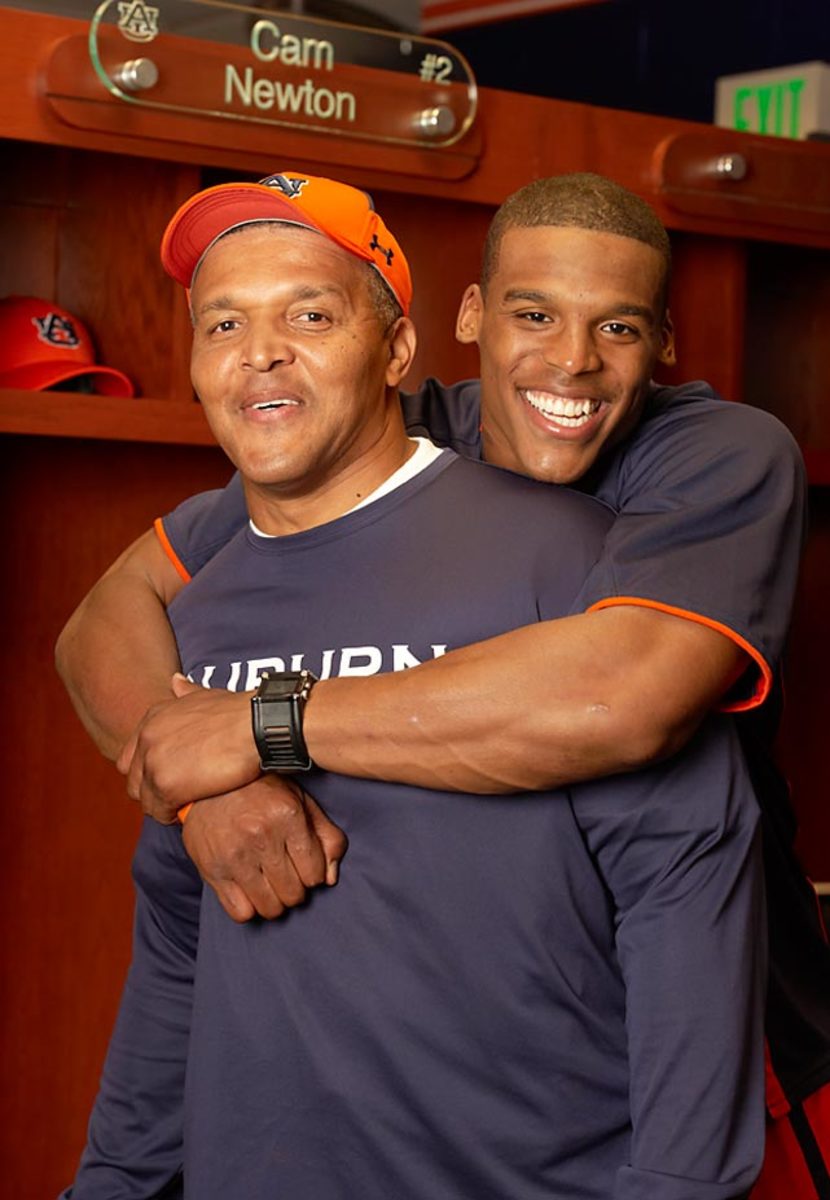

Cam and Cecil Newton Sr.

Adrian Peterson

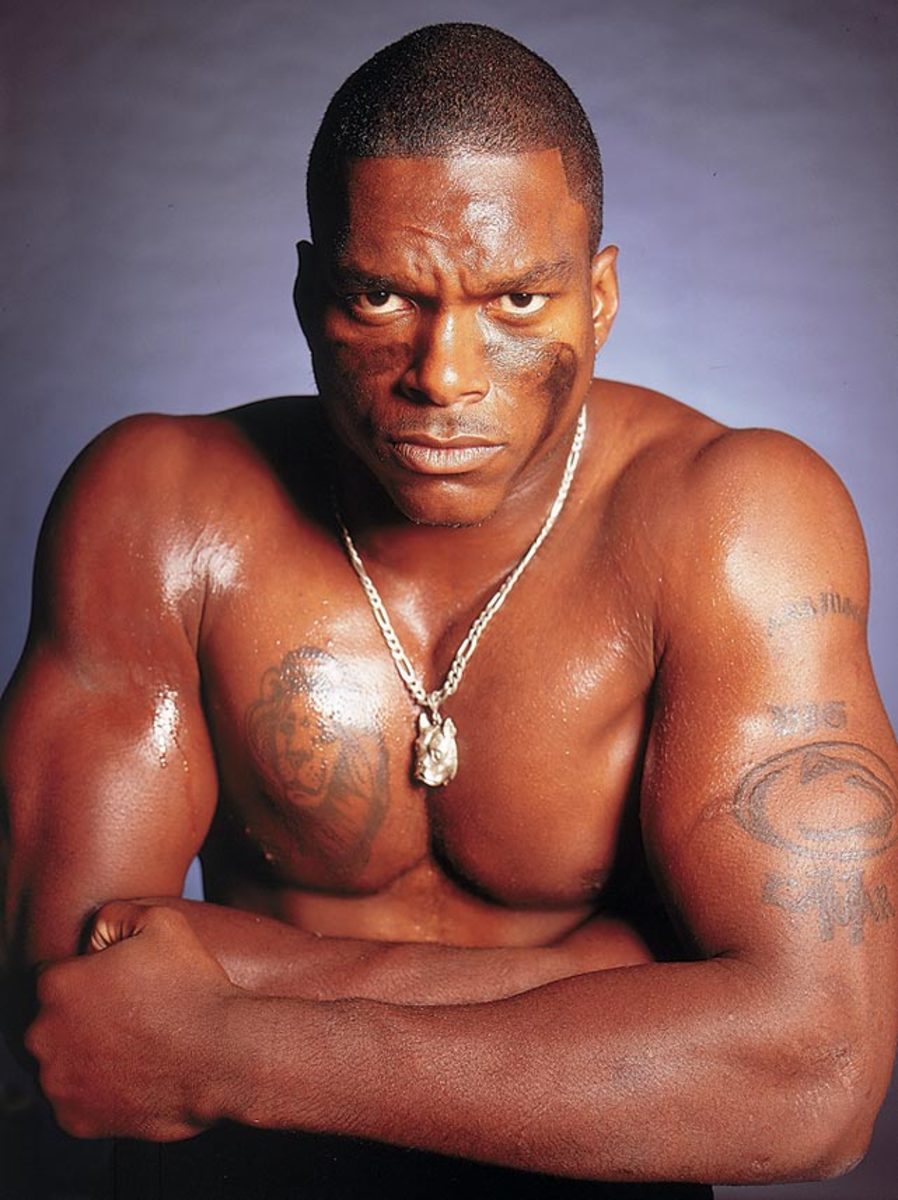

LaVar Arrington

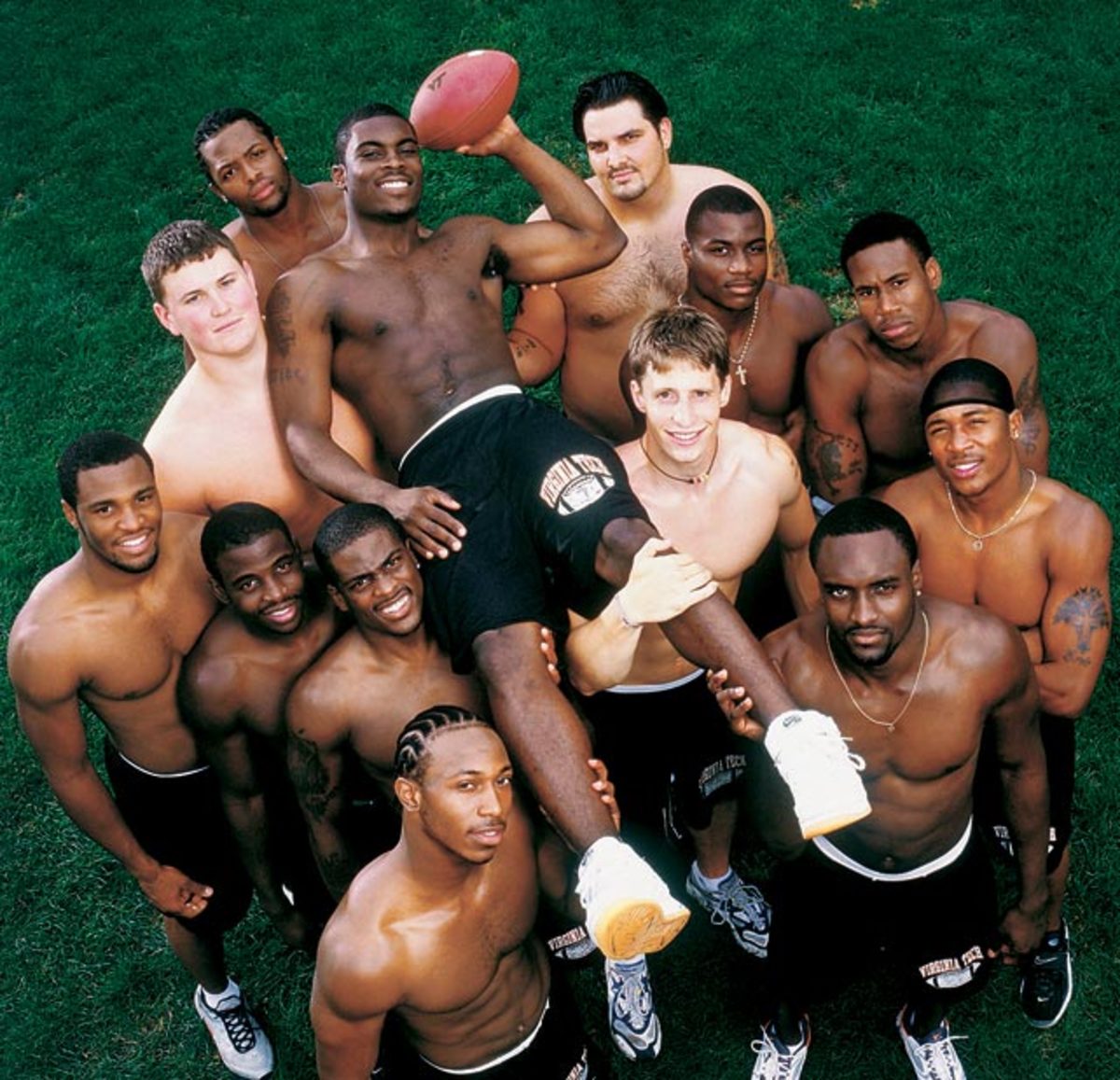

Michael Vick with his teammates

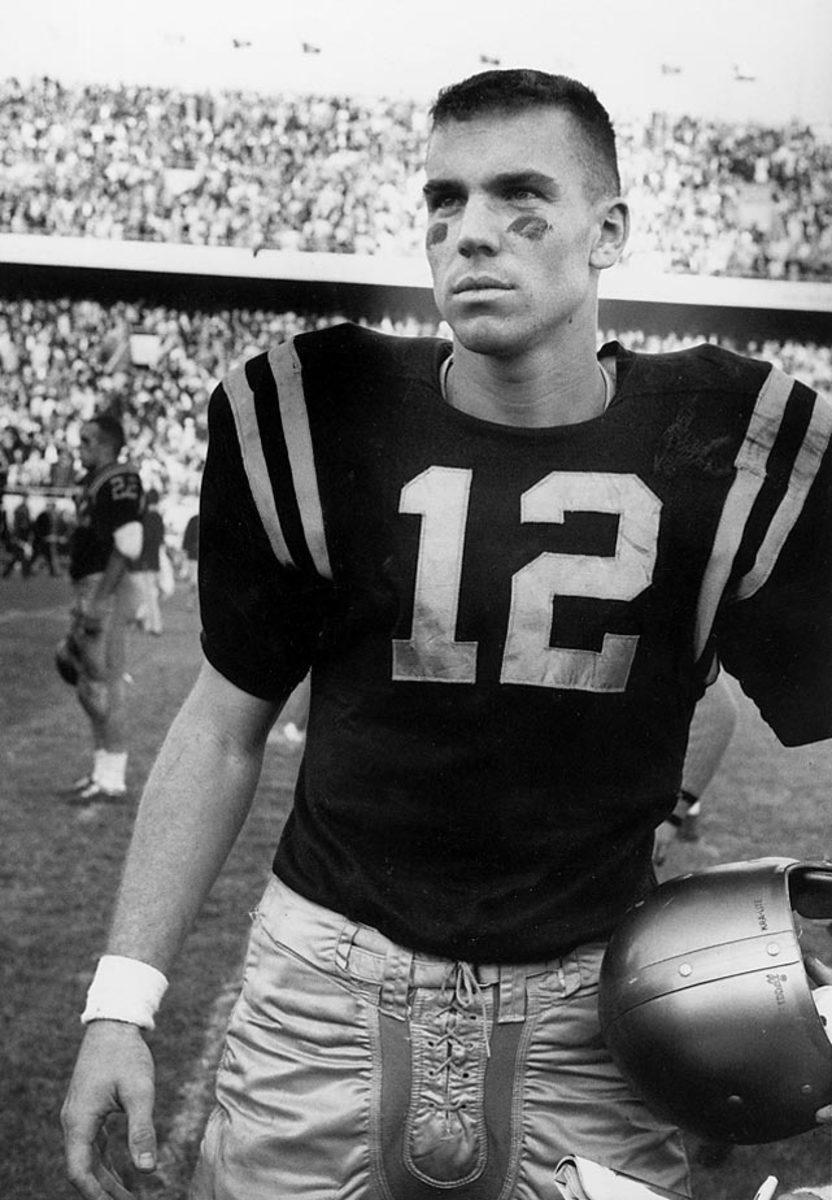

Joe Namath

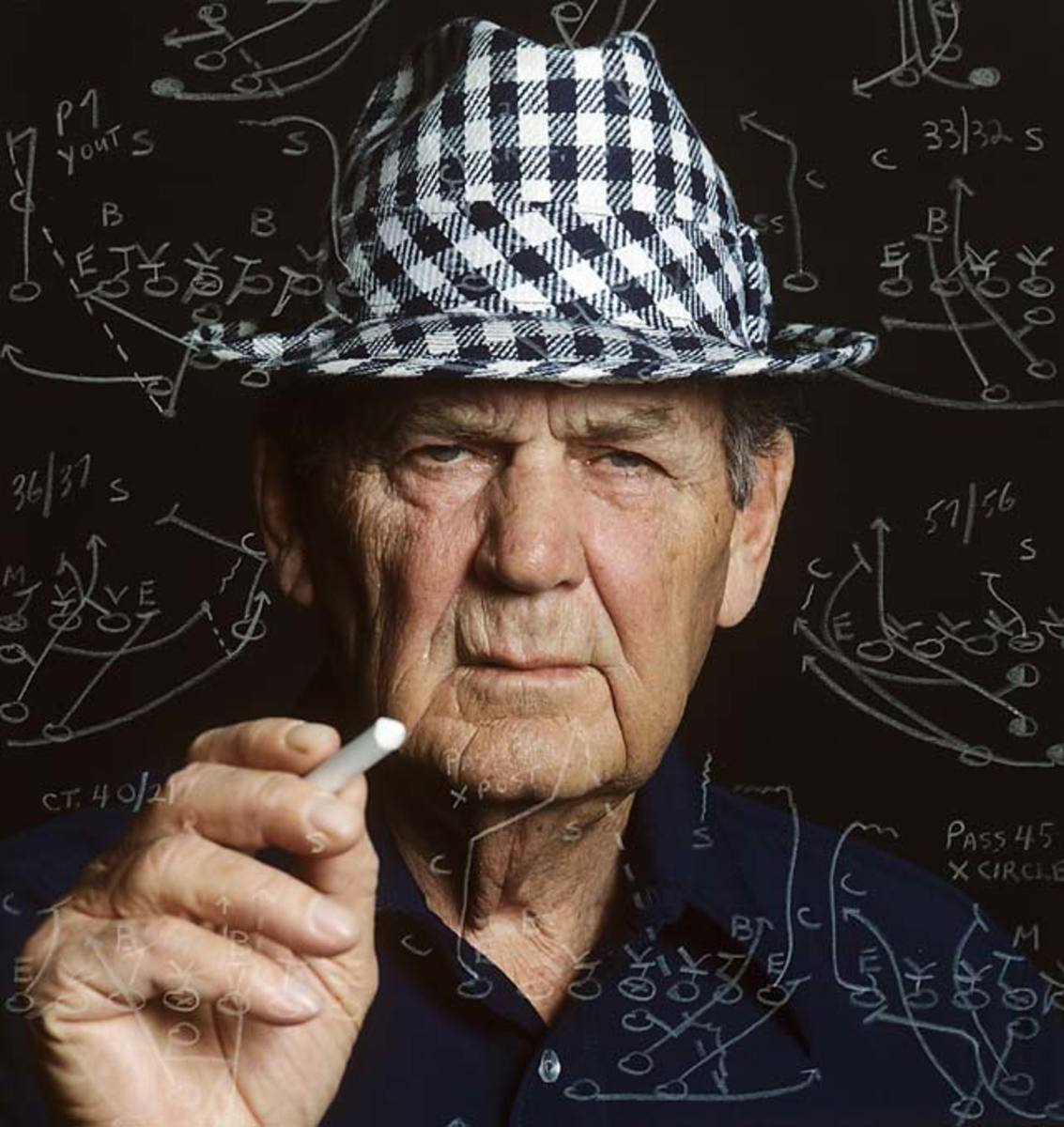

Paul "Bear" Bryant

Roger Staubach

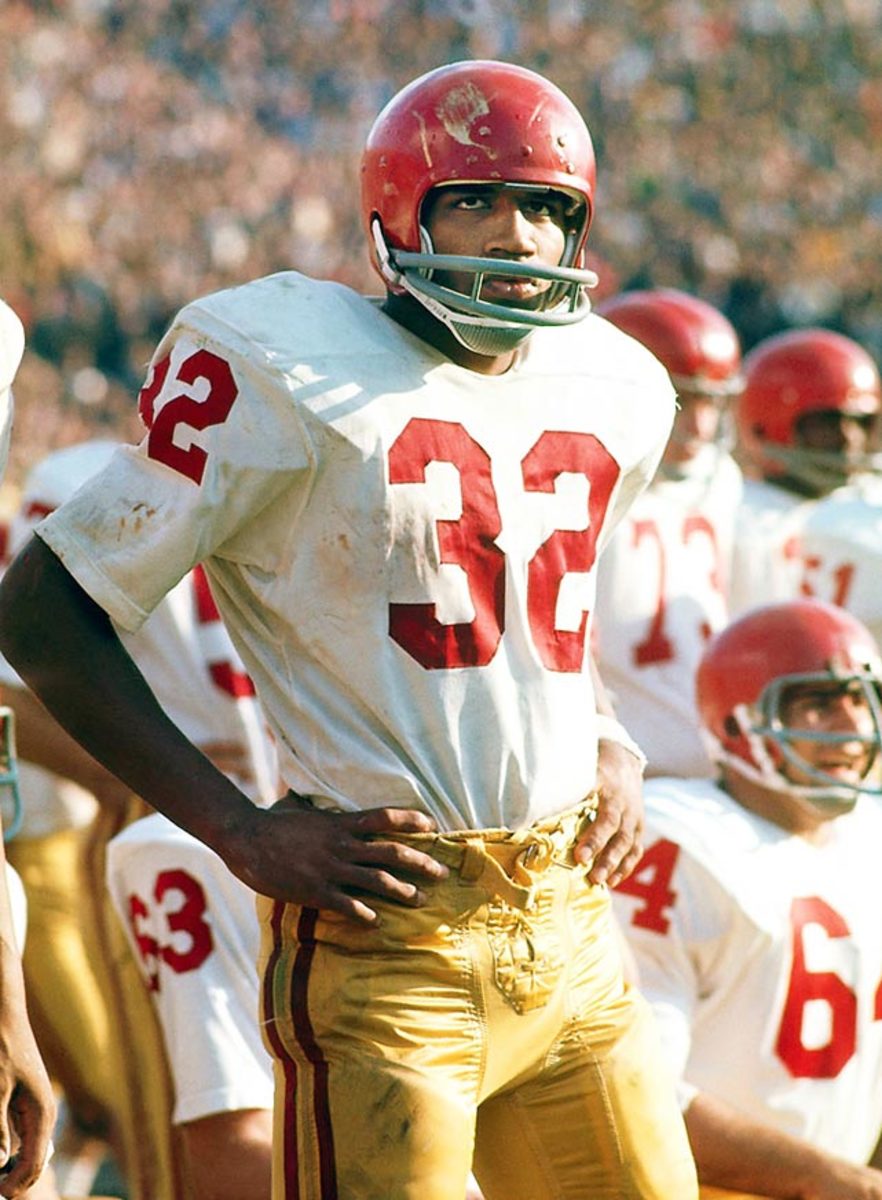

O.J. Simpson

Tom Maentz and Ron Kramer

Jim Kelly

Peyton Manning

Jadeveon Clowney

Vince Young

Matt Leinart

Reggie Bush

Karlos Dansby

DeAngelo Williams

AJ McCarron

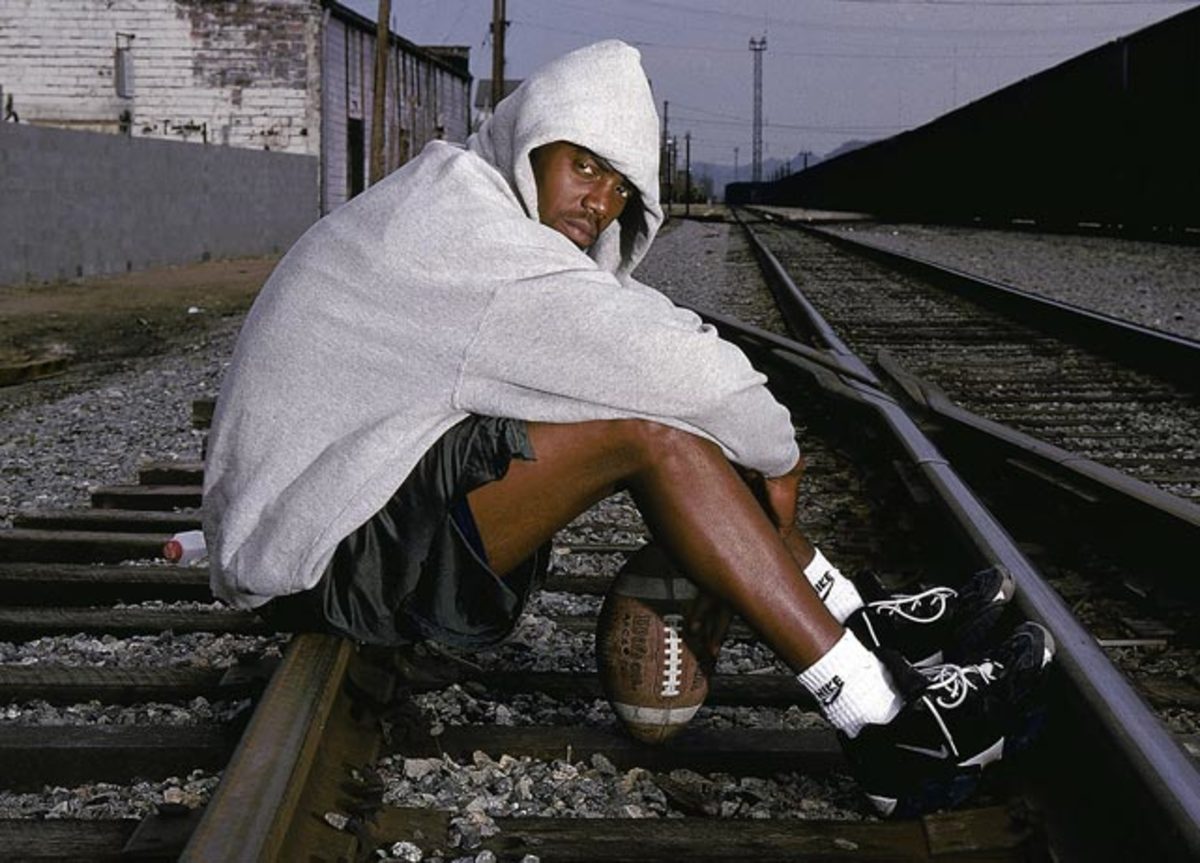

Ricky Williams

Chris Samuels

Warren Sapp

Randy Moss

Peerless Price

Oregon football players

Johnny Manziel

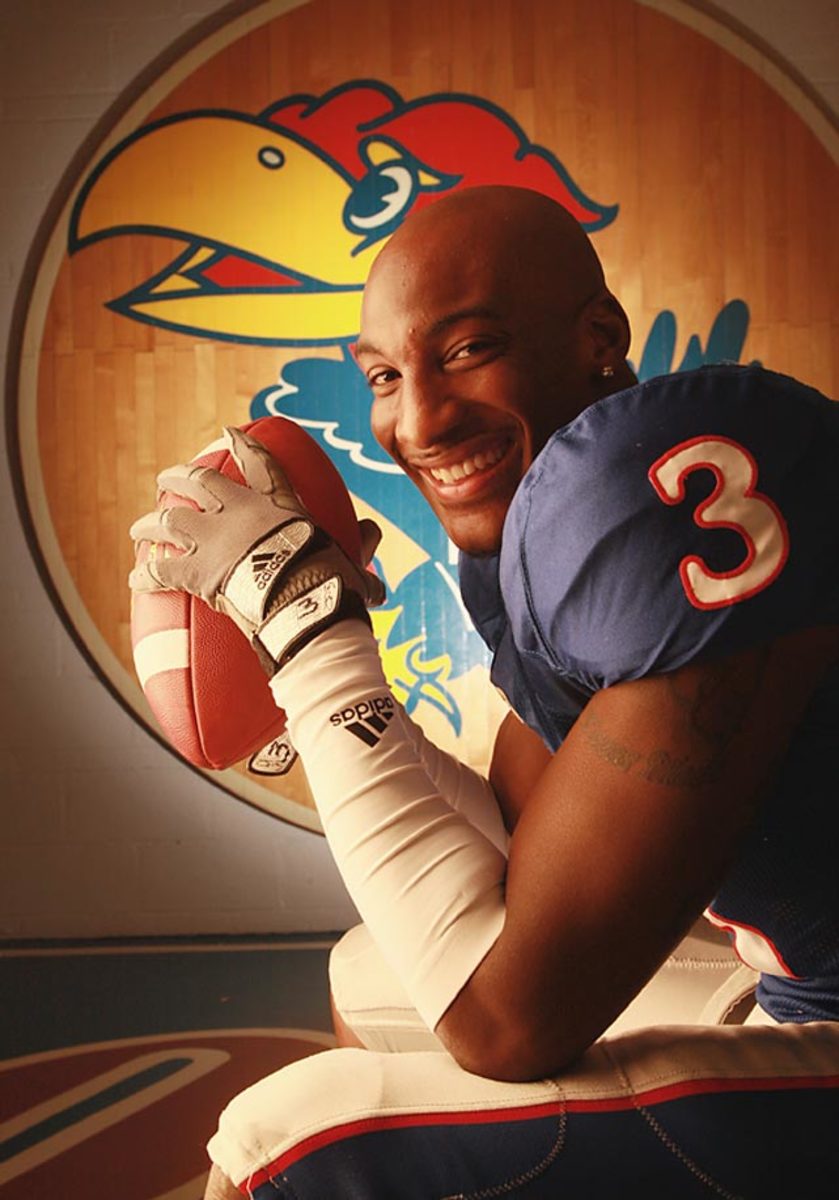

Aqib Talib

Brandon Hancock

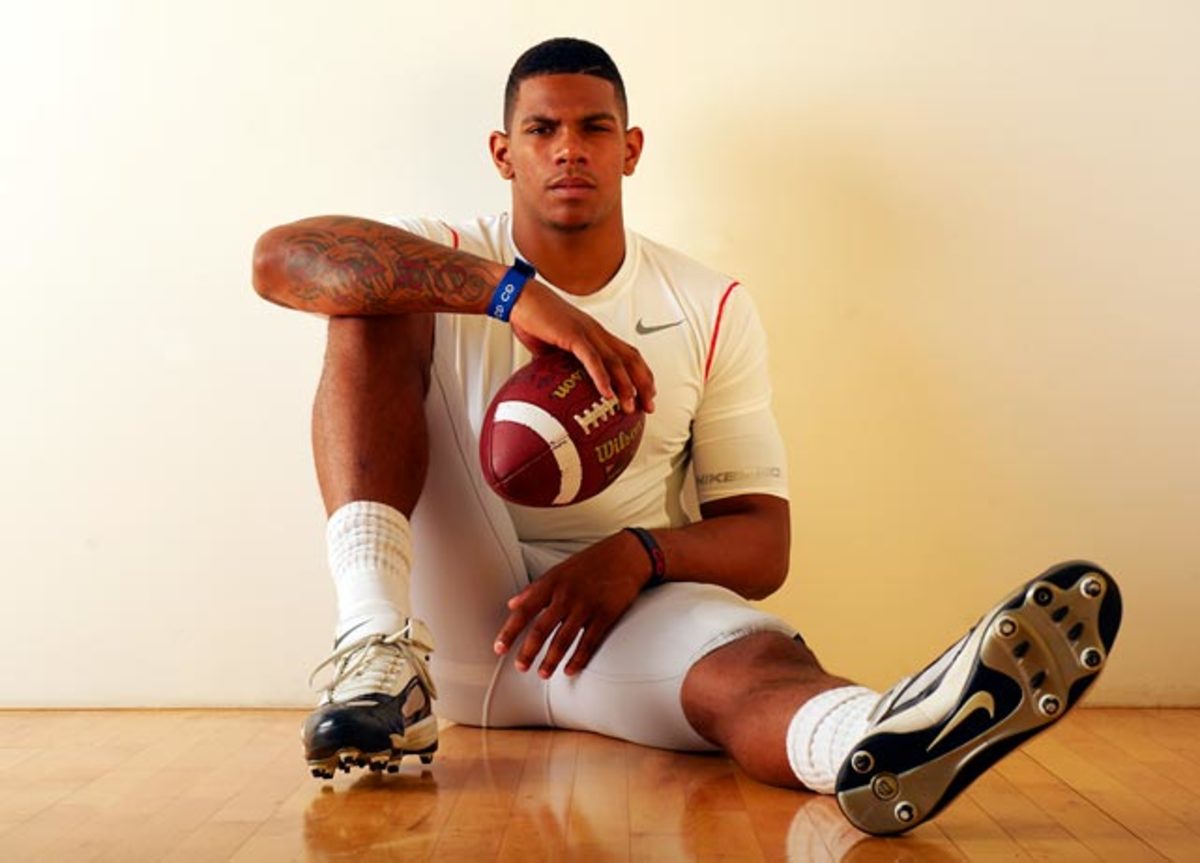

Terrelle Pryor

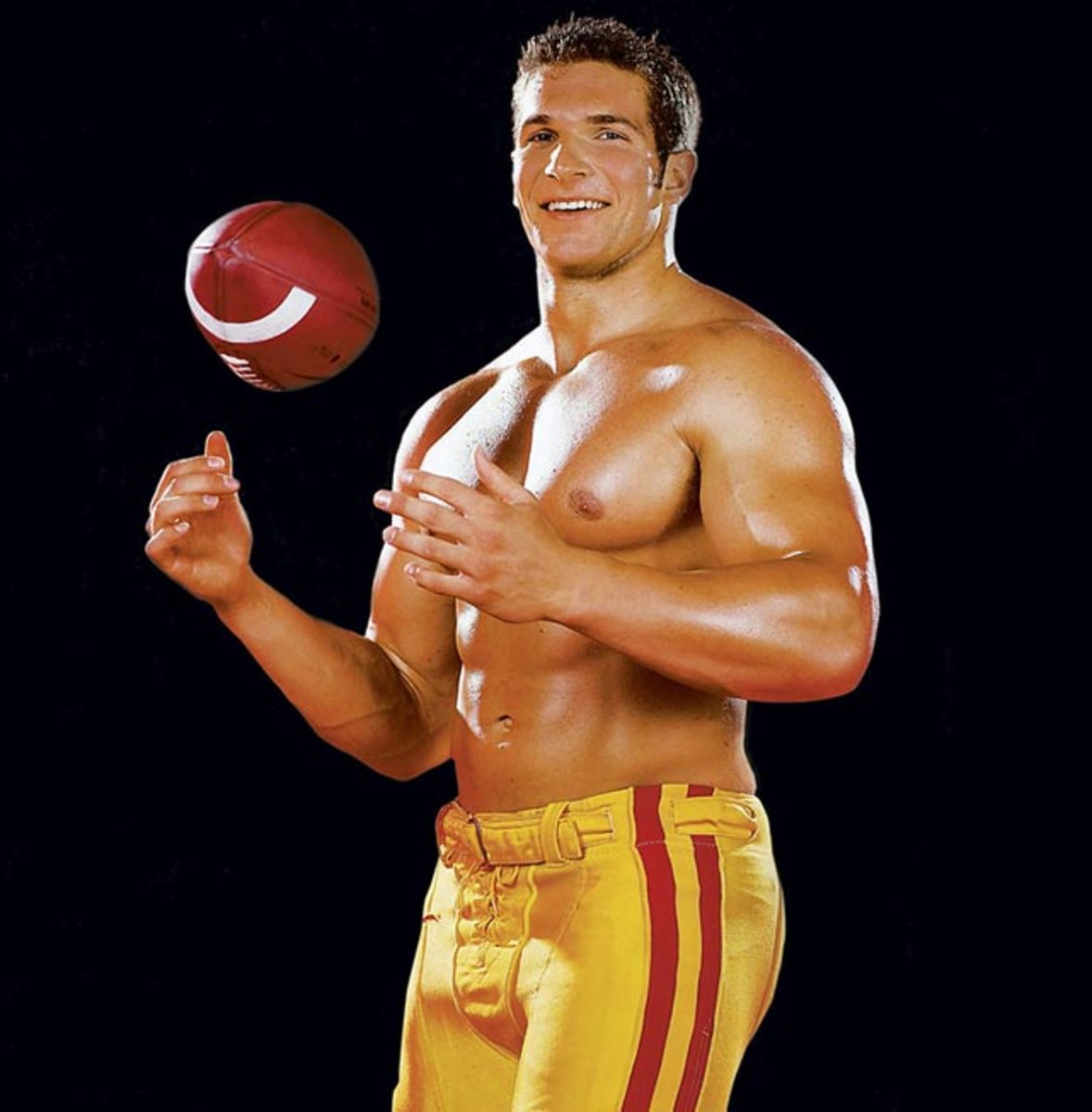

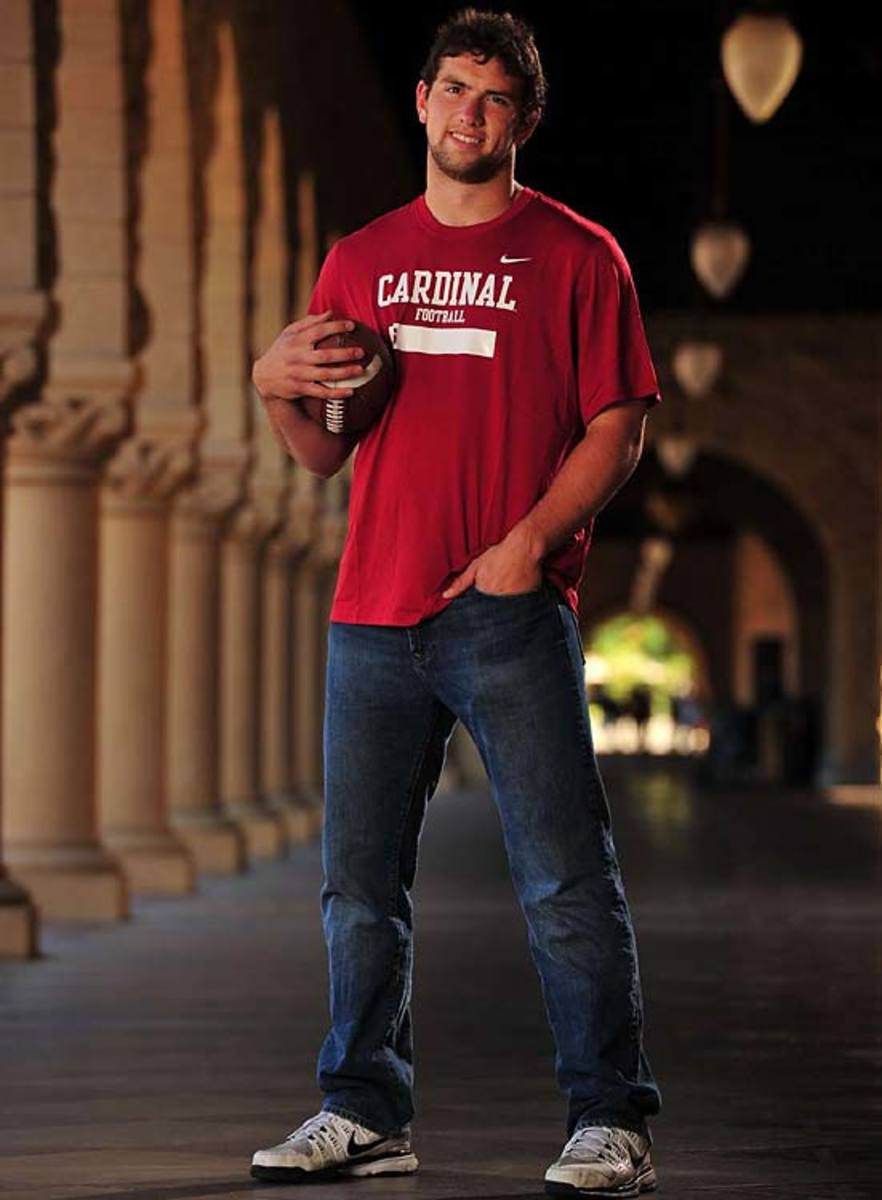

Andrew Luck

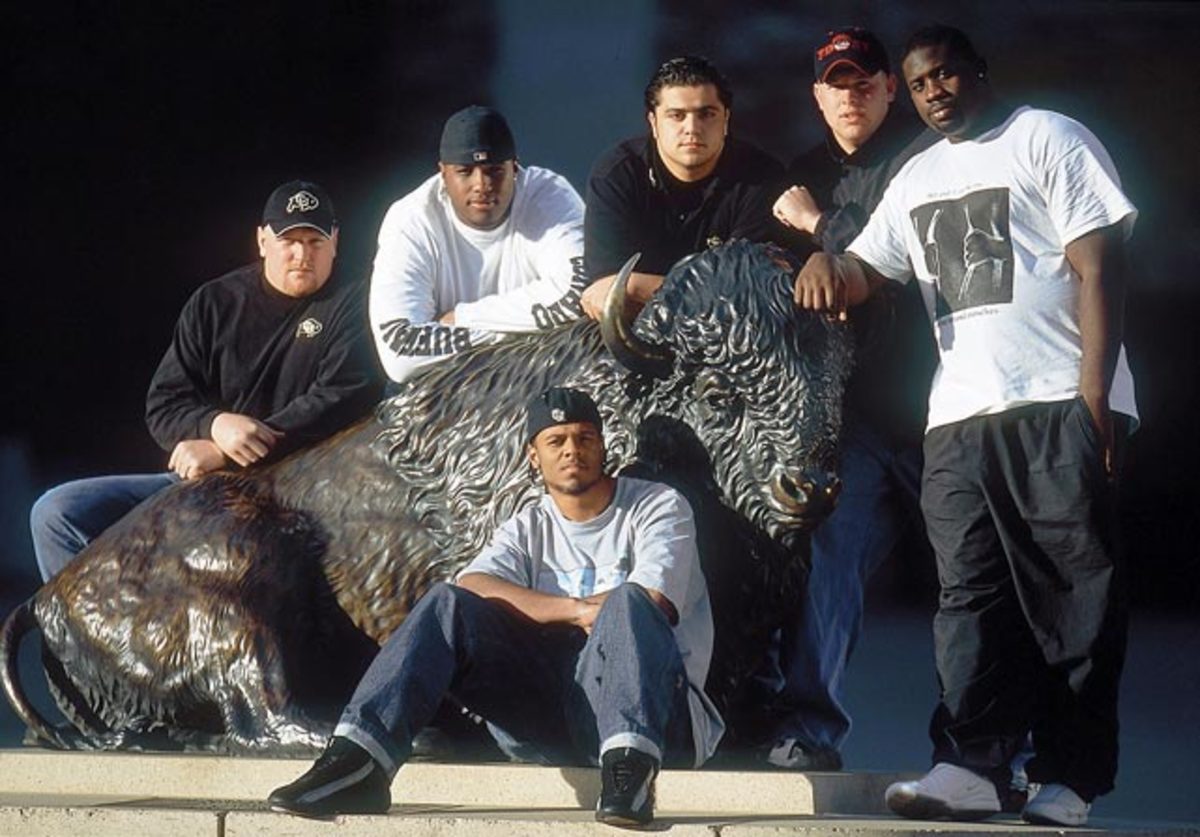

Colorado standouts

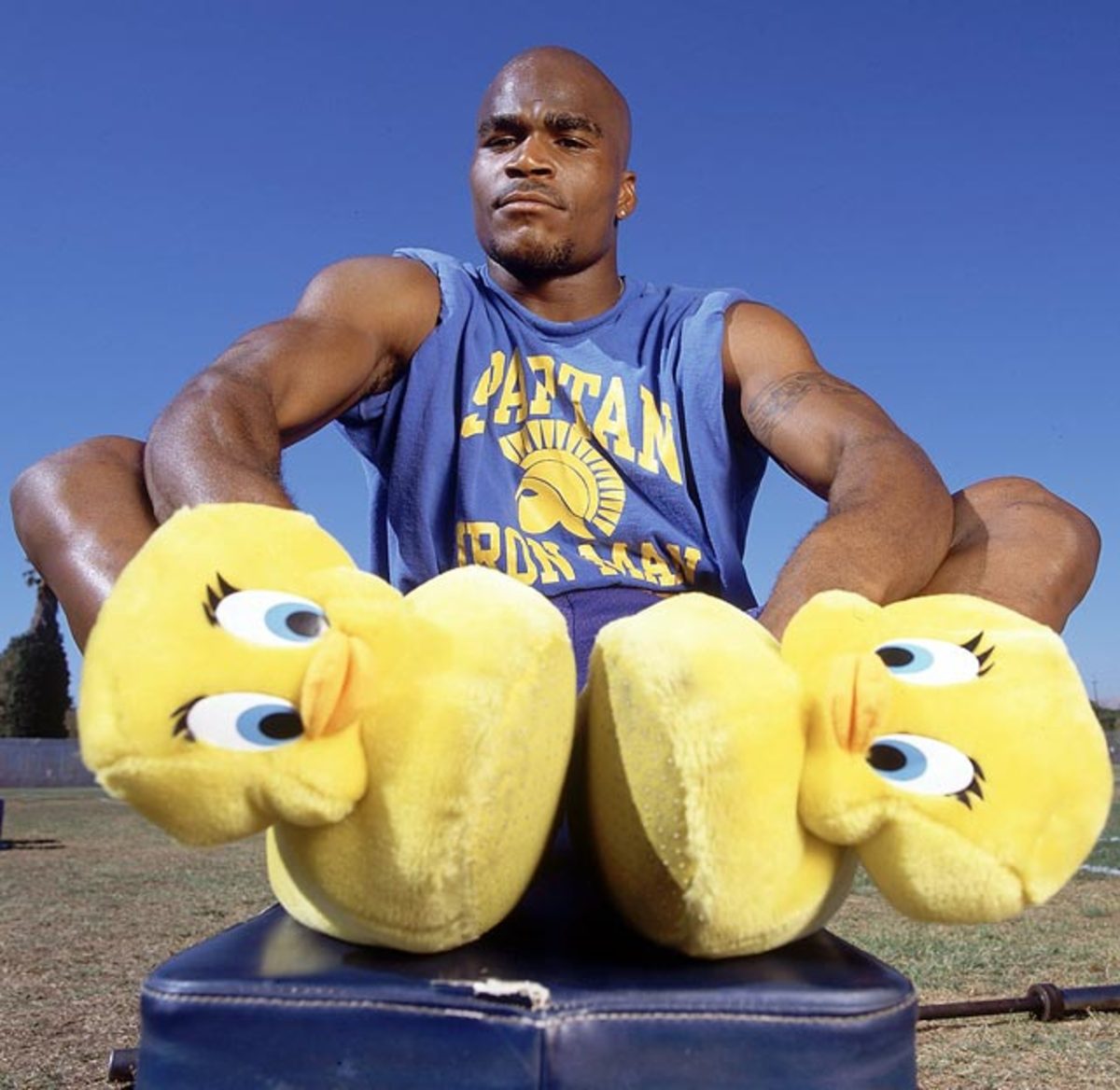

Deonce Whitaker

Lou Holtz

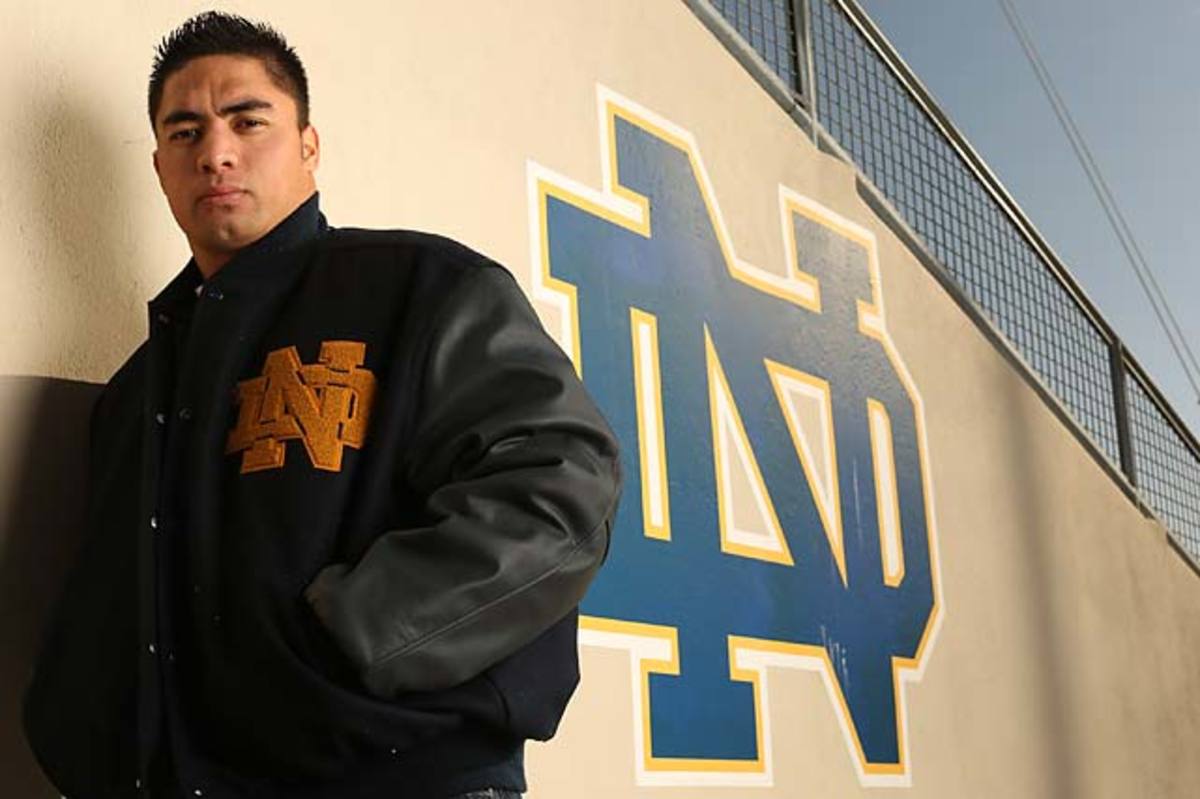

Manti Te'o

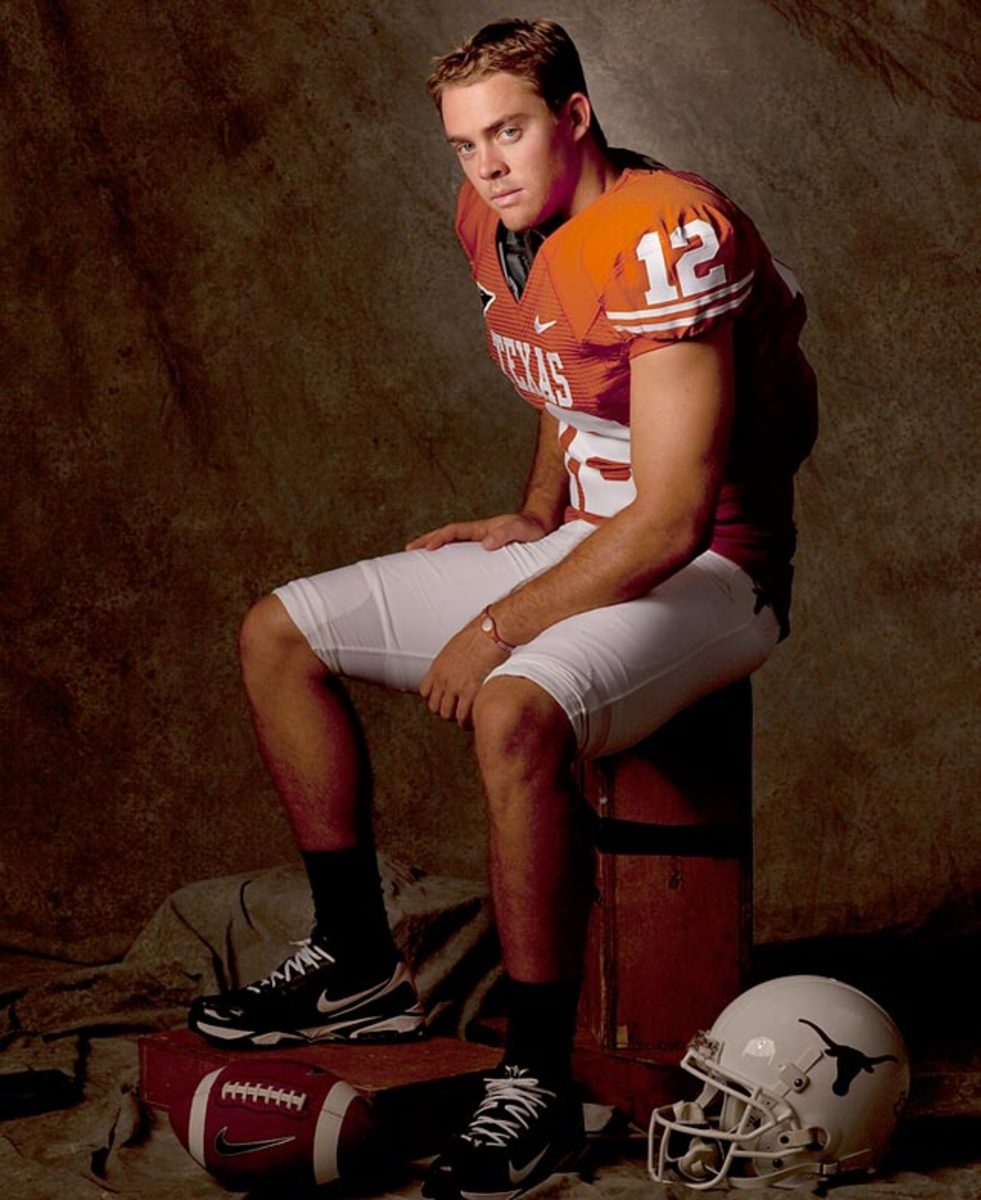

Colt McCoy

Lane Kiffin

Devard Darling

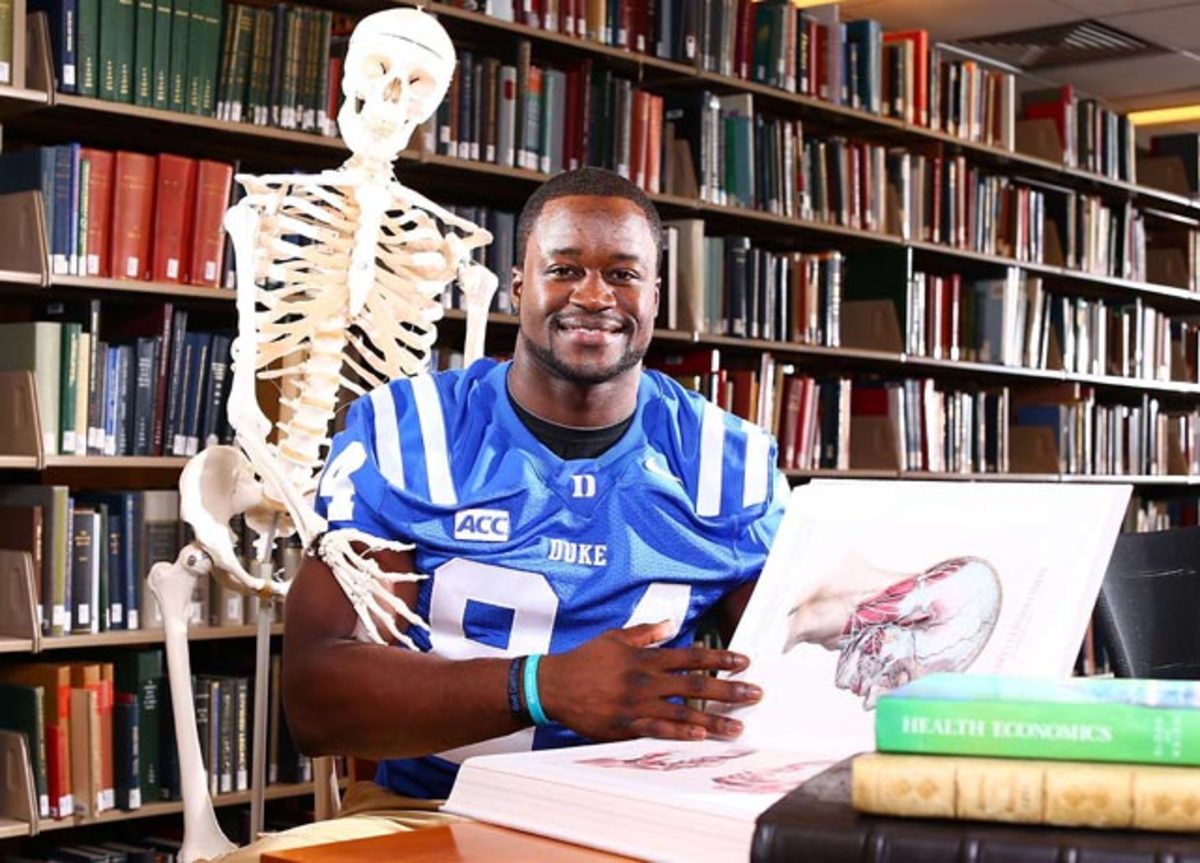

Kenny Anunike

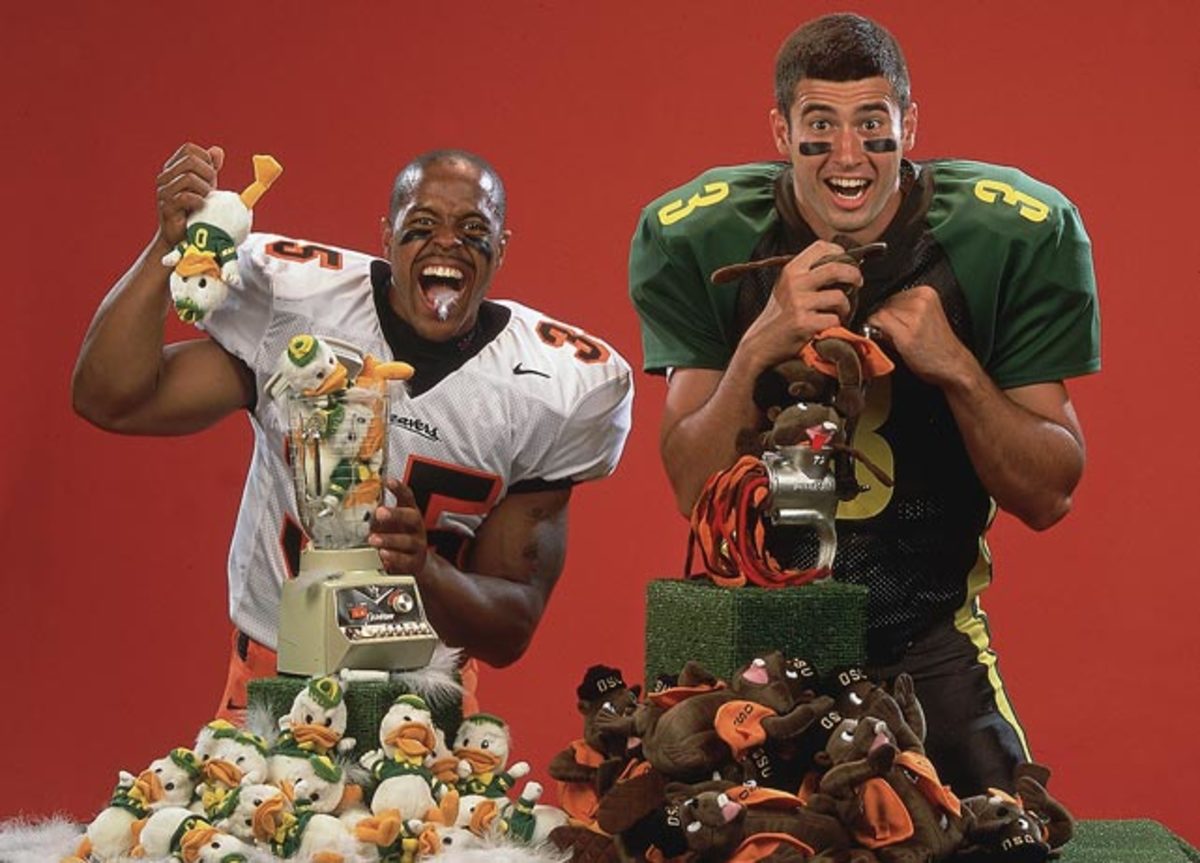

Ken Simonton and Joey Harrington

Chris Simms with his Texas receivers

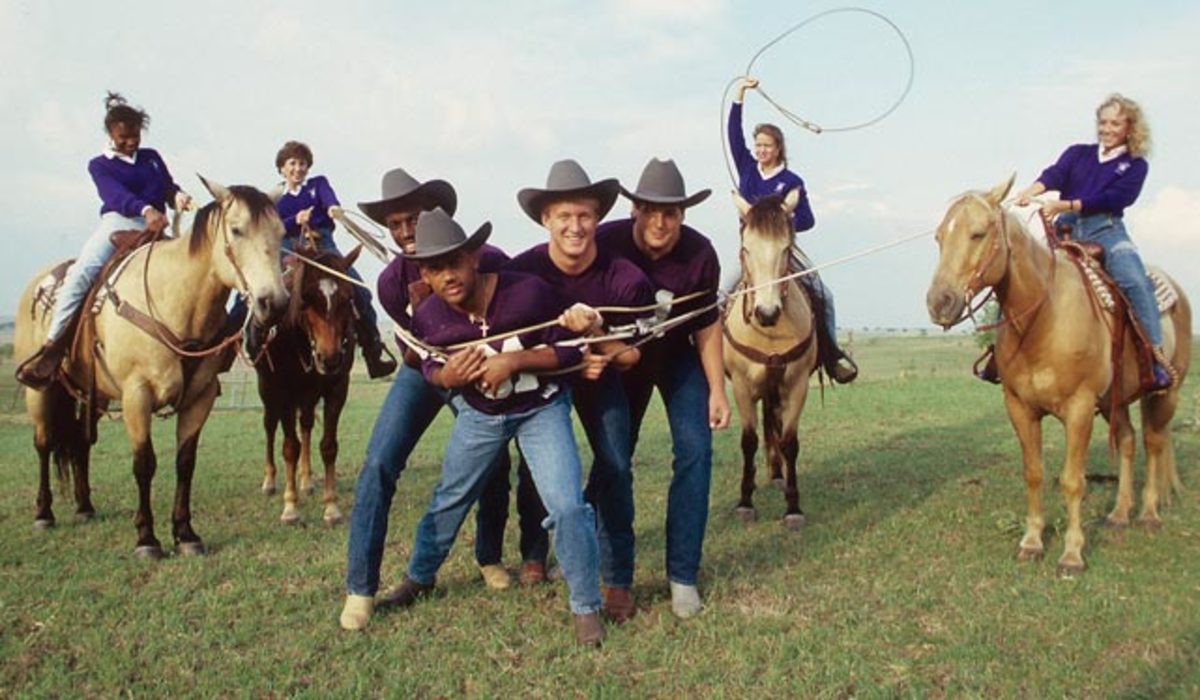

TCU's recruiting hostesses

Will Smith

Miami's offensive linemen

>

SI's NFL portraits over the years

>

SI's NBA portraits over the years

>

SI's MLB portraits over the years

>

Underwater portraits of athletes