UNC's Notice of Allegations brings up problematic state of the NCAA model

One phrase stuck out from the Notice of Allegations the NCAA sent to North Carolina regarding the school’s high-profile academic scandal. It appeared twice in the 59-page document the school released Thursday, and it might offer a clue as to how the NCAA’s Committee on Infractions could handle this case. That phrase is “NCAA Collegiate Model,” and the capitalization is the NCAA’s, not mine.

The phrase appears once in the description of the level of allegation No. 1 (that academic counselors employed by the athletic department used relationships with faculty and staff members to secure easy classes for athletes in various sports) and once in the description of the level of allegation No. 5 (the dreaded lack of institutional control). It’s a relatively new phrase in the NCAA lexicon, but it could carry extra weight in this particular case.

Searching for answer to key question in UNC scandal: Why did it start?

But first, a disclaimer. No one knows what will happen to North Carolina’s athletic department. The late Jerry Tarkanian might have suggested that the Committee on Infractions will get so mad at the Tar Heels men’s basketball team that it will decimate the football team. Or the COI could spread the pain evenly across all the affected sports, which also include the excellent women’s basketball and women’s soccer programs. Or it could administer a light wrist slap while using very mean words in its public report. All of this is on the table, and if anyone tells you they know what the COI will do, that person is lying. It’s a safe bet that neither the men’s basketball nor football program will get the death penalty or anything of that ilk, because canceled seasons mean the ACC can’t fulfill the terms of its media rights agreement, which will bring in an average of $260 million a year to the league’s schools through the 2026-27 school year. But just about everything else is in play, as it’s impossible to predict what a group with a constantly evolving membership and seemingly no regard for precedent will do.

None of the information contained within the NOA was revelatory. What Dan Kane of the Raleigh News & Observer didn’t dig up on his own the past few years, the UNC-funded Wainstein report did. The facts have been clear for a while: For 18 years, UNC offered sham classes that were attended by a highly disproportionate number of athletes. Athletic department-funded academic advisors worked with faculty within the Afro-American Studies Department to ensure athletes stayed eligible by steering them to classes that provided little work and easy high grades.

The NOA doesn’t focus on the legitimacy of the classes themselves, and this is consistent with the NCAA’s behavior in past cases. The NCAA, which is run by its member schools, isn’t set to start judging the legitimacy of one class over another. Every college offers classes that nearly every student knows are automatic A’s. The NCAA isn’t about to open that Pandora’s box; it’ll leave that kind of policing to individual accrediting agencies. This, by the way, is the reason the chair-stacking classes at Tennessee in the late 1990s and the “directed reading” classes at Auburn in the early 2000s didn’t result in NCAA sanctions. They were obviously being used to help athletes remain eligible, but the NCAA never had evidence that anyone in the athletic department or at the school helped arrange anything.

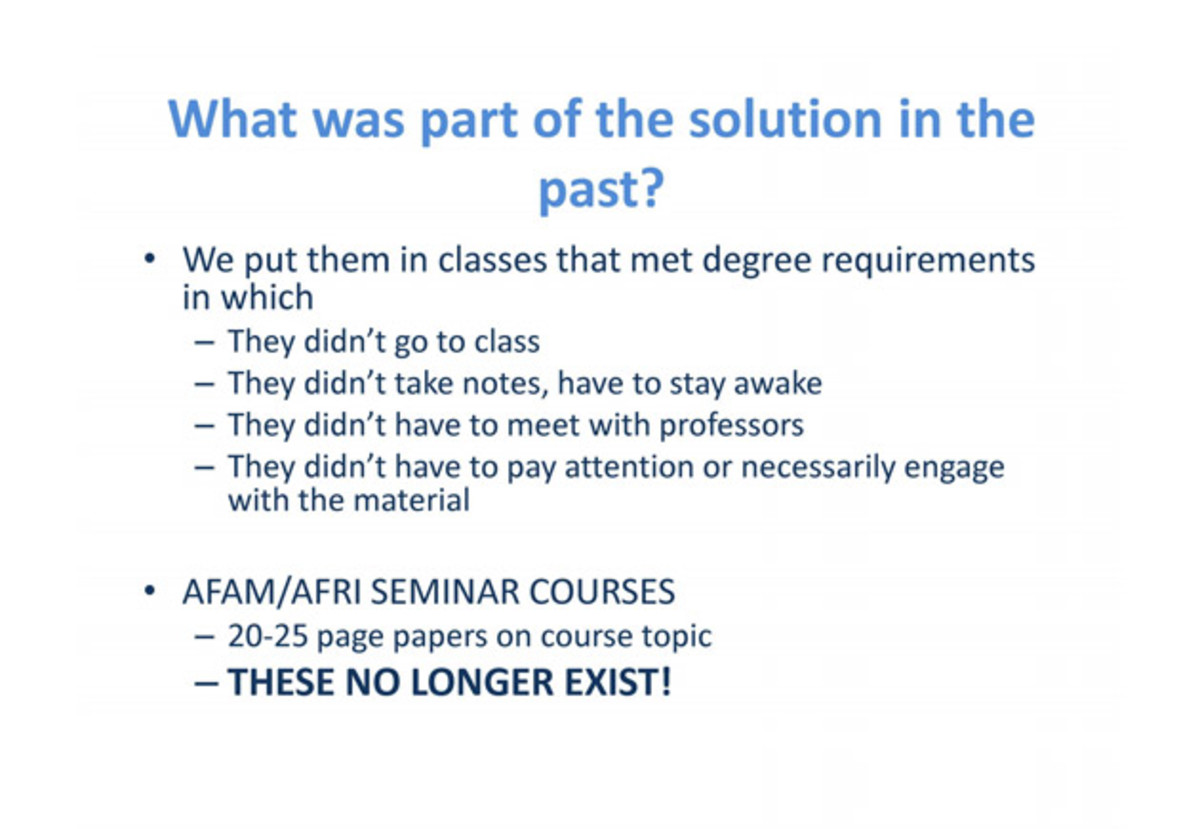

That’s the difference in this case. Thanks to the Wainstein report, the NCAA has evidence in the form of several smoking gun emails and one of the dumbest PowerPoint presentations ever created* that athletic department employees conspired with faculty from 2002-11 to steer athletes into the classes and to ensure they got easy grades. That’s why UNC faces penalties when others that have done virtually the same thing—but in a much more intelligent fashion—did not.

*This was an actual slide in a presentation given to football coaches in 2009. If you’ve watched The Wire, you’ll read this slide and hear a dumbfounded Stringer Bell asking a lackey if he’s taking notes on a criminal conspiracy.

So, why is the phrase “NCAA Collegiate Model” important? Before 2011, it didn’t appear in any of the NCAA’s propaganda materials. It wasn’t until after current and former athletes began filing antitrust lawsuits that the people in charge of college sports got together and decided they needed to actually define the system they were defending. On Oct. 30, 2012, an NCAA working group defined the NCAA Collegiate Model and stressed its protection. This is the model that is held up as sacrosanct by NCAA attorneys in court and by the lobbyists working for the NCAA in Washington. According to them, it must be defended at all costs. According to the NCAA, these are the four “enduring values” of the NCAA Collegiate Model. As a public service, I’ll translate them into English.

• Student-athlete success is vital, both academically and athletically.

Translation: A translation here is unnecessary. This is self-explanatory. It’s also basically meaningless.

• The collegiate model must embed the values of higher education, including shared responsibility and accountability; this model should be protected and sustained.

Translation: The athletes should be students, even though many people have done their best to separate them from the general student body through clustering and the construction of “academic centers” that might more accurately be termed as eligibility mills.

• In the collegiate model of athletics, amateurism is the student-participation model that guides the relationship between students and institutions.

Translation: Don’t allow anyone to pay the athletes one penny more than the courts force us to pay them.

• In the collegiate model of athletics, the guiding principles should be based on fair opportunities to compete among institutions with similar commitments to intercollegiate athletics.

Translation: You’re not supposed to break the rules you made.

When the NCAA unveiled its new violation structure in August 2013, the “NCAA Collegiate Model” was front and center.* While lawyers and lobbyists worked to protect it from the outside, the NCAA’s enforcement department would work to protect it from the inside. The hope was that by enforcing these rules in a more organized and uniform fashion, the NCAA and schools wouldn’t look as if they were making up everything as they went along. This is important, because the antitrust attorneys who are suing the NCAA are constantly on the lookout for inconsistencies that they can use against the NCAA in court.

*The violations in the North Carolina case occurred before the new structure was put into place, so while the NCAA is using the new language, it probably is using the old penalty structure. What does that mean? Not much. The Committee on Infractions was wildly inconsistent under the old structure, so it doesn’t really matter which structure is used except to the head coaches who could face suspensions under the new structure for actions taken by subordinates.

In recent enforcement cases involving what the NCAA calls Level I and Level II violations, schools have been accused of threatening the “integrity of the NCAA Collegiate Model.” This phrase popped up in the public report on the Syracuse case that got Orange men’s basketball coach Jim Boeheim suspended and AD Daryl Gross fired. It popped up in the public report on the case involving Georgia swim coach Jack Bauerle, who conspired to help an athlete get a passing grade in a class for which he never completed any work.

The NCAA has to at least attempt to protect this model, because its attorneys have already stated in court papers that the NCAA has no responsibility to ensure that athletes get a quality education. Attorney Michael Hausfeld, the lawyer who got the win last year in O’Bannon v. NCAA, filed a suit against UNC and the NCAA earlier this year on behalf of former North Carolina football player Devon Ramsey and former North Carolina women’s basketball player Rashanda McCants claiming the school did not fulfill its promise of a quality education while hiding behind NCAA rules to keep the athletes from reaping a larger cut of the revenues brought in by their sports. In the NCAA’s response to the suit, its attorneys wrote, “the NCAA did not assume a duty to ensure the quality of the education of student-athletes.”

Breaking down the SEC's new rule for incoming transfers; Punt, Pass & Pork

While that is the proper defense strategy in that case, it won’t help the NCAA’s argument in other cases. During the O’Bannon trial last year, the NCAA’s attorneys tried hard to convince Judge Claudia Wilken that the mix of education and athletics is critical, and giving more money to the athletes would upset that balance. Wilken was unmoved, but the NCAA will keep trying to use this argument because it has no other defense as an organization of member schools that have colluded to create an artificial salary cap for athletes. The NCAA will certainly use an educational hook in trying to rally lawmakers to its side. Education always plays well on Capitol Hill. Of course, the judges and lawmakers the NCAA hopes to convince might not believe education is terribly important to the NCAA or its members if the COI doesn’t take decisive action in the biggest case of academic fraud in the organization’s history.

This is part of the quandary for the members of the COI. They have come along at a delicate time. If they don’t hammer North Carolina, it will look once again like the NCAA doesn’t care about education. But if they do hammer North Carolina, they’ll only deny scholarship offers to athletes who weren’t even born when the pattern of academic fraud began. If the NCAA’s commitment to education (or lack thereof) is Scylla, then the public perception of the COI’s penalty menu is Charybdis. The COI lacks the authority to punish most of the people who were actually guilty of the infractions. The athletic department and faculty members involved in the scheme are already out of their jobs. So are the chancellor and AD who presided at the time. No matter what common sense may say, the NCAA has no evidence linking any current coaches to the scheme. (Pity current AD Bubba Cunningham and football coach Larry Fedora, who came to Chapel Hill after the scheme ended and have spent their entire time there cleaning up messes made by others.)

The most the COI can do now is cut athletic scholarships to cripple the involved programs. Yanking a scholarship that would have gone to someone currently in middle school or high school doesn’t solve anything. If the members of the COI do hammer North Carolina, they’ll look like heartless ghouls punching the stomachs of 18-year-olds because they can’t reach the people at whom they’re really mad. That sort of punishment used to draw cheers. Lately, people have begun thinking about who actually takes the brunt.

So, what do the members of the COI do with North Carolina? Do they protect the NCAA Collegiate Model at the expense of people who had nothing to do with the academic fraud? Or do they show mercy on future Tar Heels while offering yet another example that the NCAA doesn’t care about academics enough to take any meaningful action?

Such is the state of the NCAA Collegiate Model in 2015. No matter what path the COI chooses, the NCAA will lose.