Analyzing the movement of coaches and assistants across college hoops

This is Part II of Sports Illustrated's study on player and coach movement in college basketball. Part I focused on the transfer and commitment habits of top-100 recruits from the classes of 2007-15. Additional research for this study was contributed by Chris Johnson, Jake Fischer and Harrison Malkin.

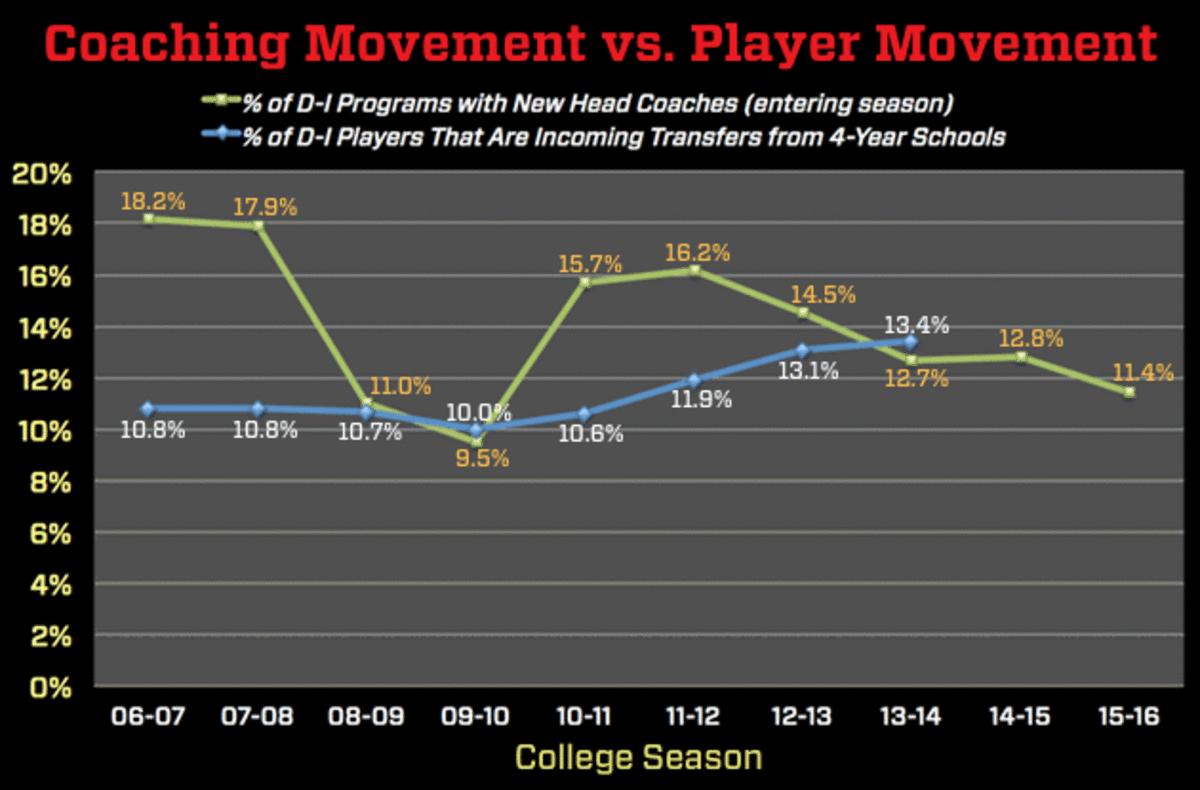

Data from the NCAA indicates that the transfer rate within Division I men's basketball has been rising slightly and steadily since 2010. Incoming four-year transfers accounted for 13.4% of D-I players in the most recent reporting year, 2013-14; although the NCAA bases its rates on incomplete samples, this suggests there were approximately 600 new D-I transfers on rosters in '13-14. That is a large number, but it's up to you whether to view it as a problem or merely part of the game.

It does not seem appropriate, however, to view D-I roster instability as a player issue alone. Consider the following chart, which, over a time span of the most recent 10 seasons, plots the NCAA's incoming, four-year transfer rates alongside SI's data on yearly turnover rates for head-coaching jobs:

The average annual percentage of D-I teams with new head coaches (14.5) was higher than the average incoming transfer rate for four-year players (11.4). And in six of the eight seasons for which corresponding data was available, head coaches had a higher turnover rate than the player-transfer rate.

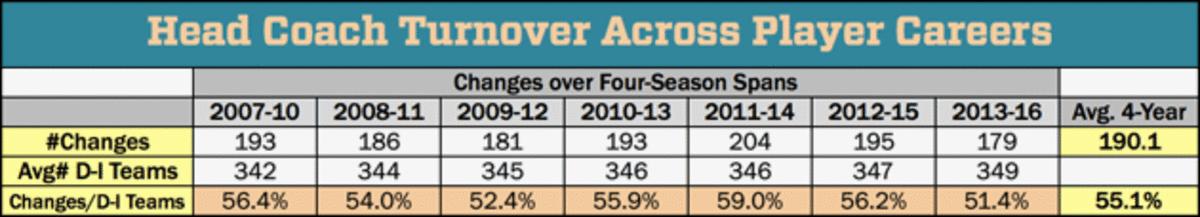

When we put head-coaching turnover in context with the standard length of a player's college career—a career that goes smoothly, with no redshirt or medical redshirt seasons—the result was eye-opening.

Over any four-season span from 2006-07 to the present, the volume of head coaching changes was always more than half the volume of teams in D-I.

If a player's career spanned from the 2009-10 season to 2013-14, for example, 204 D-I head coaches—a number equal to 59.0% of the D-I membership—would have debuted during that time. The average four-year career in our study sample coincided with 190.1 head-coaching debuts, a number equal to 55.1% of the D-I membership. The full data is in the chart below:

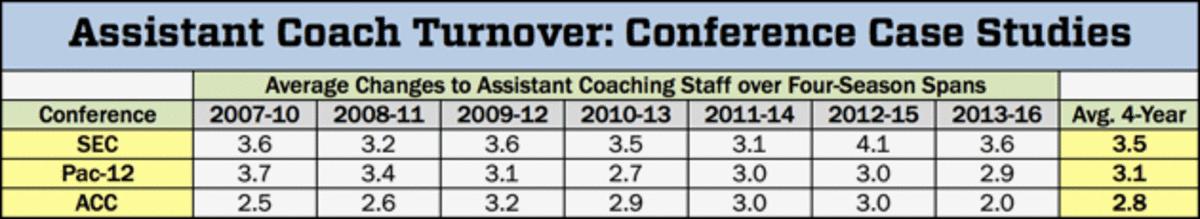

Instability in the coaching ranks goes beyond the high-profile jobs. High-school prospects' relationships with college coaching staffs typically begin with assistants. Each program has three assistant coaches, and an essential part of their job is identifying players on the recruiting trail, and building early bonds with them, their family and other members of their decision-making circle. While reporting stories for SI, we've heard many players, anecdotally, say they're closer with a certain assistant—often the one who recruited them, or the one who spent the most time on their individual development±than they are with their head coach. Thus it was important to assess turnover rates in the assistant ranks as well.

SI conducted case studies of assistant-coach turnover on every team's staff in three major conferences—the ACC, Pac-12 and SEC—from the lead-in to the 2006-07 season up to the present. During any four-season span of the study, the average volume of assistant coaching changes was 3.1. Which means:

Over the course of a player's standard, four-year college career, the likelihood is that there will be as many assistant-coach changes as there are assistant-coach positions in the program.

The full conference-by-conference data is below:

The reasons for assistant-coaching changes are varied. Staffs tend to get complete overhauls following head-coaching changes, when the new guy wants to bring in his own personnel; assistants often make lateral moves to other staffs, or less frequently, get hired as head coaches elsewhere; or they get forced out, serving as the fall guys for team struggles or NCAA violations.

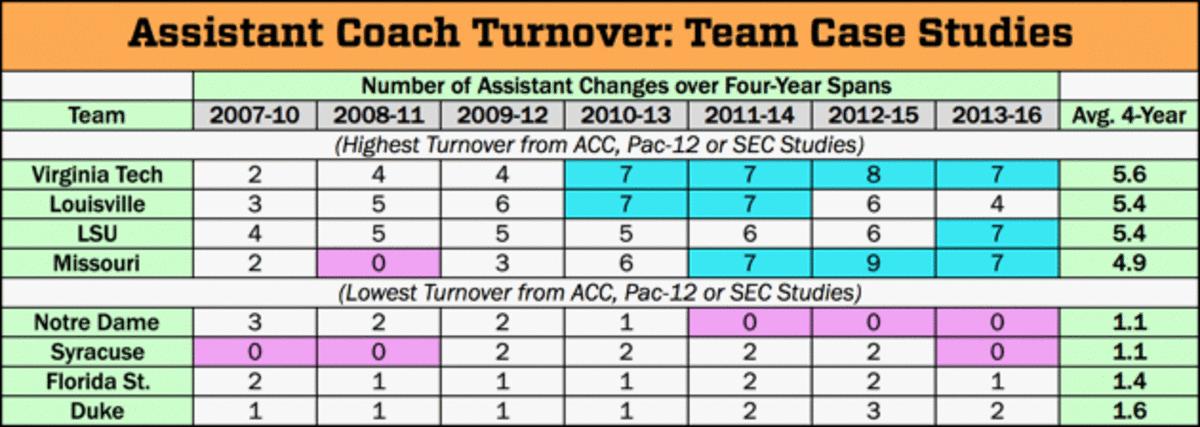

The contrast in stability between some programs in SI's study striking. On the stable front we present Notre Dame, which has kept the same head coach, Mike Brey, since 2000, and hasn't made an assistant-coaching change since 2009-10. The average volume of assistant-coach turnover for a four-year Fighting Irish player was just 1.1.

On the unstable front we present Virginia Tech, which has employed three head coaches and 15 different assistants since 2006-07. Any Hokie player who entered the program in 2009-10 or later and stayed a minimum of four seasons has endured at least seven assistant-coaching changes. Virginia Tech's average rate of assistant turnover in any four-year span was the highest in the study, at 5.6.

Louisville, despite having the same head coach (Rick Pitino) for the duration of the survey, had the second-highest assistant turnover rate (5.4 over any four-year span). Missouri, meanwhile, is the school with the most volatile four-year span: a Tigers player who stayed from 2011-12 to 2014-15 would have endured nine assistant-coaching changes.

The full data on outliers is below:

The study data offers proof of benches in flux: of college basketball in an era with a growing transfer rate among players, which has been outpaced, in most seasons, by the turnover rate of head coaches, which has been outpaced, significantly, by the turnover rate of assistant coaches—the people who develop the deepest recruiting relationships with the players while they're in high school. In school-hopping, just as it is with program-building, instruction and game-planning, coaches are the leaders.