Is the era of abusive college coaches finally coming to an end?

This article originally appeared in the Sept. 28, 2015, issue of Sports Illustrated. Lauren Shute contributed reporting. You can subscribe to the magazine here.

Just how thoroughly Simon Cvijanovic once identified as an Illinois football player sits right there in his Twitter handle. And it was on that social media platform, in a series of tweets in May, that the former offensive tackle known as @IlliniSi documented how he had allegedly been abused, and thereby emphatically put on notice a college sports establishment where power has long tilted toward coaches at players’ expense.

Cvijanovic, a senior starter from Cleveland, charged that third-year coach Tim Beckman pressured him to play with knee and shoulder injuries. Cvijanovic resisted, which he says prompted Beckman to ridicule him by forcing him to watch practice while dressed in an opposing team’s uniform. Further, he claimed that Beckman concealed from him the extent of his injuries. “If I’m hurt, I’m hurt,” he tweeted. “I don’t need to be called a pussy to make me make bad decisions for my body.”

Was this a cri de coeur or sour grapes from someone who had quit the team late in the 2014 season? Athletic director Mike Thomas first called Cvijanovic’s outburst a “personal attack” on Beckman, and a core of Illini players sided publicly with their coach. But then the script flipped. Andrew Weber, a former kicker at Toledo, where Beckman coached before coming to Champaign, weighed in with a tweet of his own: “We had the exact same issues. Thanks for standing up!” The Daily Illini and the Chicago Tribune found more players who told stories similar to Cvijanovic’s, with the Tribune reporting that six other Illini alleged Beckman would threaten to take scholarships away from injured players. Chancellor Phyllis Wise retained an outside law firm to investigate, and in late August, a week before the team’s opener, Thomas cited preliminary findings that broadly supported Cvijanovic’s claims in announcing Beckman’s dismissal. “The university decided to follow the adage ‘ready, shoot, aim’ in terminating coach Beckman before its own investigation was close to complete,” Bruce Braun, a Chicago litigator retained by the former Illinois coach, told SI. “Its alleged preliminary findings are entirely baseless and devoid of merit.”

• MORE: Will P.J. Flick usher in a new era of coaches?

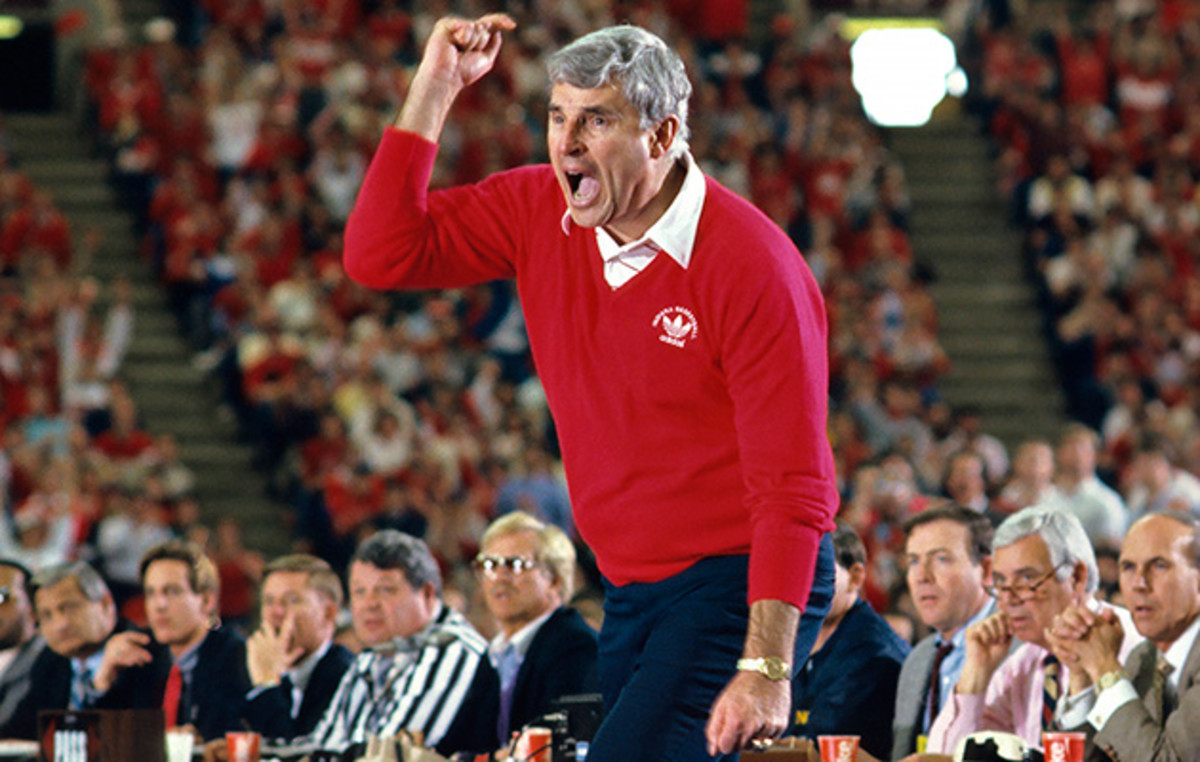

College sports has a long tradition of coaches orchestrating valorous suffering. Football teams such as Bear Bryant’s 1954 Texas A&M Junction Boys and Charlie Bradshaw’s ‘62 Thin Thirty at Kentucky endured methods that would meet most modern tests of torture. But gauzy mythologizing of male bonding under abusive leadership has given way to broad outrage at incriminating video—of Indiana basketball coach Bob Knight going after guard Neil Reed’s jugular in ‘97 and of Mike Rice pushing, throwing balls at and kicking his Rutgers basketball players between profane doses of antigay invective in 2013. Meanwhile, allegations of abusive coaching now surface frequently in nonrevenue sports, particularly those for women. Abuse may be occurring no more often than before, but it’s simply coming to light because more players, empowered by digital tools, are standing up for themselves.

The news bristles with allegations of abuse far from the public glare of Big Ten football. According to a 2013 Yahoo! Sports report, swimmers at Utah said they blacked out, went into convulsions and needed emergency treatment because of the tactics of former coach Greg Winslow, who allegedly ordered one Ute to swim underwater with PVC pipe strapped to his back and another to do so with a mesh bag over her head. (Winslow, who was placed on USA Swimming’s banned for life list last year for having had a sexual relationship with one of his underage club swimmers in 2007, did not respond to multiple requests from SI for comment.)

Yet today most abuse isn’t physical, but psychological or emotional, often directed at injured or sick players. Multiple players and a former assistant coach told Providence’s WJAR-TV in 2014 that, before Rhode Island chose not to renew her contract in May, softball coach Erin Layton often targeted injured or ill players, whom she would threaten with comments like, “Don’t ever get sick again, or I’m going to kill you.” In response, some players say they developed ulcers or eating disorders or committed self-harm. “The school did conduct an investigation and found no basis for the charges,” says Layton, who didn’t want to address specific allegations because of guidelines governing medical confidentiality. “I always followed the instructions of the athletic trainer on staff. I can assure you that I’m not the person that story made me out to be.”

“I believe this is a cultural problem,” says Ramogi Huma, executive director of the National College Players Association, which often hears from abused athletes. “A lot of coaches, they were hollered at and abused when they were players.”

The problem is particularly acute in women’s basketball. Over the past 28 months at least seven Division I schools have investigated, suspended or parted ways with coaches in that sport following player complaints of mistreatment. Illinois bought out associate coach Mike Divilbiss after players and parents complained that Divilbiss and coach Matt Bollant verbally abused the players and fostered racial divisiveness. The school chose to retain Bollant following yet another outside investigation that, while finding no wrongdoing, included the coaches’ acknowledgment that their “coaching at times was too negative.” Seven former players refused to speak to investigators; they have filed a $10 million civil suit that charges the school and coaches with fostering a racially hostile environment.

A tragic fight between college-bound basketball stars changed lives forever

“I’m a really upbeat and energetic guy, and I want the program to be a reflection of me,” says Bollant, who doesn’t dispute the report’s conclusion that he and Divilbiss played the roles of “good cop, bad cop,” respectively, with things sometimes leaning “too far to the bad cop side.” He says he welcomes Thomas’s pledge to enact a formal code of conduct for Illini coaches and a protocol for athletes to lodge complaints. “They went through 18,000 documents and watched film of every practice and game, so it’s pretty telling,” says Divilbiss, who’s pleased with the report’s findings. “You coach for 30 years, there are going to be people you connect with and people you don’t.”

We’ve come a long way from the days when abuse consisted of suicide sprints in 110° heat without water breaks. Boston University women’s basketball players going back nearly a decade told The Boston Globe and espnW.com of alleged psychological beatdowns behind the closed door of coach Kelly Greenberg’s office. There Greenberg would sit a player down, with a box of Kleenex to dry the tears that frequently spilled forth, and deliver her appraisals. Players reported hearing that they were “worthless,” “too shy and backward to get anywhere in life,” and “never should have been born,” with the abuse sometimes veering into personal appearance. “The one-on-ones were never about basketball,” former Terriers guard Katie Poppe told SI. “It was about who I was, my personality, my relationship with my parents. I remember one time she printed out the definition of sheepish. She told me I needed to be sheepish. She said I needed to not speak a single word for the rest of the year in the locker room. That was how the meeting started—I wasn’t allowed to speak.”

As a starter or contributor, she says, “I wasn’t told what a miserable waste of life I was. But as soon as I got hurt, I was called into those meetings every day. As if I wasn’t upset enough about getting hurt.”

Greenberg, who resigned in April 2014, denies making those comments. “I come from parents who were both coaches. My 11 brothers and sisters all played basketball. That’s not how I treat people.” Greenberg told SI, “Unfortunately, I was never addressed with any of these problems. They went directly to the media, so it was out of my hands—out of my university’s hands. Coaching is a challenge these days.”

Huma says that when he gets calls from abused players, he advises them to seek counseling. “About half of them,” he says, “already have.”

*****

It’s not clear exactly when college athletes became less responsive to the bullying coach, though the diminishing NCAA basketball tournament success of Knight’s Indiana teams after 1994 provides a clue. Nor is it clear which factors led to this sea change. Perhaps the travel-team world of youth sports began to produce a young athlete who expects more support; maybe modern helicopter parents and their children are reluctant to loosen their bond so discipline can be subcontracted out to coaches. But the evidence is clear: For its 2010 Growth, Opportunities, Aspirations and Learning of Students in College (GOALS) study, the NCAA gathered data from almost 20,000 college athletes. Paired with a contemporaneous American College Health Association (ACHA) assessment of almost 54,000 undergraduates, 7.5% of them varsity athletes, the results make explicit both the extent of abusive coaching and the fragility of the athletes being abused. In Division I, 31% of men’s basketball players and 22% of football players reported that a coach “puts me down in front of others,” according to the GOALS study, and only 39% of women’s basketball players strongly agreed that “my head coach can be trusted.”

Even more alarming, athletes have never been more psychologically vulnerable, reflecting a trend among all college students. The ACHA assessment found that 41% of athletes had “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function” and 52% had “felt overwhelming anxiety,” with the figures for women jumping to 45% and 59%, respectively. Further, 14% of athletes said they had “seriously considered suicide,” with 6% having attempted it. From Penn runner Madison Holleran and Ohio State defensive lineman Kosta Karageorge, to Missouri swimmer Sasha Menu Courey and North Texas basketball player Eboniey Jeter, recent athlete suicides have included victims of both genders and a broad range of backgrounds, academic settings and sports.

Poor mental health is even more common among college students who don’t play sports. But those ACHA figures are for athletes competing across all NCAA divisions; just as rule-breaking and low graduation rates are most problematic on Division I campuses, there are indications that mental health is worst where the stakes are highest and demands most intense. A 2013 Georgetown University Medical Center study asked 117 current and 163 former D-I athletes if they suffered from depression. Researchers expected the ex-athletes to be most susceptible, as they navigated the transition from the spotlight. Instead the study found depression to be more than twice as common among active athletes than those who had finished their college careers.

64 reasons to be excited for the 2015-16 college basketball season

Since he arrived in January 2013 as the NCAA’s first chief medical officer, Dr. Brian Hainline has met with members of Student Athlete Advisory Committees on dozens of campuses. “Uniformly, they tell me they really hope we’ll address mental health,” he says. Hainline has made sure that the next GOALS survey, the results of which will be released in January, will capture even more data about athletes’ well-being, and by early next year he also expects to distribute a set of mental health best practices to schools in all three NCAA divisions. Most of those recommendations, he says, will be preventative—”how to get things right at the front end.” In November 2013, Hainline convened a three-day task force on mental health that included administrators, medical professionals, coaches, trainers and clinical social workers as well as athletes. “At some point during that task force,” he says, “everyone broke down.”

Hainline says his outreach efforts will address abusive coaching—to a point. “The NCAA isn’t in a place to be a coaching certification body,” he says. “But we are in a place to supply education. The reality is that not every coach is sensitive to the mental health issue. We want mental health to be as treatable as an ankle sprain.”

He also knows that drawing up best practices isn’t a solution. “Even if we get the knowledge out to 1,100 schools, as in any aspect of public health the most difficult challenge is getting what we know reliably implemented,” says Hainline, who’s trained as a neurologist. “But culturally, we’re getting to a place of acceptance. I get the sense that talking about mental health is less of a taboo.”

As a tennis player at Notre Dame during the 1970s, Hainline himself went through a bout of depression. He quit the team and lost his scholarship, but returned after a hiatus, winding up as the Irish’s No. 1 singles player his senior year while paying his own way. “I came back to tennis on my own terms, not my coach’s or my father’s,” he says. “There’s a big difference between the athlete who’s positively engaged and takes full ownership of his sport and one who’s really playing for someone else.”

Or as Jim Thompson, the founder of the Positive Coaching Alliance (PCA), a Bay Area--based group pledged to overthrowing the negative coaching paradigm, puts it, “It’s hard to be driven when you’re being driven.”

*****

The inspiration for the PCA struck Thompson at Stanford Business School during a class on organizational behavior. His professor had introduced the concept of “threat rigidity”—the instinctive response of leaders, when in a tight spot, to become defensive, reactive and likely to revert to old, even discredited ways of doing things. Today, with trainers around the country and a trove of online resources, the PCA evangelizes for coaching rules of thumb like “demanding, not demeaning,” and the “5-to-1 ratio”: five instances of encouragement to every one of criticism. “I have sympathy for coaches,” Thompson says. “Especially at the college level, a coach knows that if he doesn’t win he’ll lose his job.

“But the best way to get the best out of athletes is to create a positive culture in which they’re respected and believe in their value, and that the coach believes in them. The idea of the all-knowing coach who has lots of power and uses it in the way we now call bullying—that was kind of the norm. But all the research shows that it’s not the way to get the best out of people.”

Some of the most striking evidence comes from Dr. Barbara Fredrickson, the author of Positivity and a social psychologist who runs the Positive Emotions and Psychophysiology (PEP) Lab at North Carolina. “Negative emotions grab people’s attention more,” says Fredrickson, who attributes this to evolutionary reasons, because survival in the prehistoric environment often depended on sudden alerts. “So there’s a perception that the best way to get what you want out of employees or players is by negativity or threats, or being stressful or intense. But in terms of bonding, loyalty, commitment to a team or a group and personal development over time, negativity doesn’t work as well as positivity.”

Fredrickson’s research shows that positive emotions expand awareness, allowing for reception of a broader array of information. They make people more flexible, resilient and creative. A collegeage athlete can be highly susceptible to the influence of coaches, parents and peers, and may not have fully developed what she calls “resilient emotional regulation,” so abuse may leave a deeper scar on a young adult than an older one.

Two of her findings speak directly to the player-coach relationship. “Positive emotions are especially contagious,” she says, “and a leader’s positive emotions are more contagious than anyone else’s.” Her other insight comes as a result of eye-tracking analysis, brain imaging and behavioral studies, which together show that improved mood actually broadens the perceptual field. “People’s peripheral vision expands,” she says, “when they’re experiencing positive emotions.”

In other words, by yelling at his point guard for missing that wide-open teammate in the corner, a coach has probably ensured that it will happen again.

The brain is a work in progress, constantly shaped by the experiences around us. But the brains of young adults are particularly malleable. If young people tend to make unwise choices, it’s partly because the prefrontal cortex isn’t fully developed until after age 25. Meanwhile adversity and stress can impair neurogenesis, the process by which that ever-evolving brain produces new cells. According to Dr. Richard Davidson, who directs the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds at Wisconsin, “there’s some evidence to suggest that stress can impair the circuitry that regulates negative emotions in particular. So [abuse] can have this very pernicious effect, which can have a spiraling effect and lead to an increase in negative emotions as a consequence.”

Appreciating all that John Calipari has achieved en route to the Hall of Fame

Since the late 1990s, Dr. Ben Tepper of Ohio State’s Fisher College of Business has made abusive leadership in the workplace his specialty. He gathers data from such fields as manufacturing, health care, financial services, education and the military, and he is so renowned in his field that the NCAA has used his Abusive Supervision Scale, aka the Tepper Scale, in its GOALS report. Believing that the coach-athlete relationship is essentially a boss-employee arrangement by another name, Tepper overlaid GOALS results on to his own vocation-by-vocation data. What he saw left him slackjawed: Abusive leadership is two to three times as prevalent in college sports as in the orthodox workplace.

When he studies an industry, Tepper identifies what he calls “precursors in the environment” that make abuse more likely. “They’re all in sharp relief in college coaching,” he says. “Bosses under stress combined with targets who are weak and vulnerable and can’t fight back. Talent can give you some power, but it’s not like you can just say, ‘I’m leaving,’ because you have to sit out a year. The only protection an athlete has is to be an amazing performer.”

One other thing left Tepper astonished. “I’m trained as a psychologist, so my interest from the beginning has been in well-being,” he says. “And when I see the depression levels of young athletes—our best young people, physically and mentally, who have taken all the steps to get to a high level—that just throws me for a loop. To see them that vulnerable must mean the environment is overwhelming.”

Our conviction that hostility works is encouraged by a culture that makes legendary figures of Knight and Steve Jobs. Tepper believes that both succeeded in spite of their abusive leadership—that Knight was very tactically smart, and Jobs had a rare combination of design sense and business acumen. “The studies all say there’s no incremental benefit to being hostile,” he says. “Even when you control for a leader’s experience and expertise, hostility always produces diminishing returns.”

The work of Tepper and others subverts more assumptions. Doesn’t a coach who yells convey urgency that helps players muster strength? In fact, he says, abuse is depleting: “We all have a finite amount of energy. You’re concerned with whether your coach will yell at you rather than doing your job, so it impairs your executive function. And bosses who combine hostility with support are more depleting, because you don’t know what’s coming next.”

Doesn’t a hostile coach create team cohesion? In fact, she’s more likely to create fault lines and cliques, which can lead to a downward spiral. “If you’re angered by your environment, it’s harder to come together with others in that environment,” Tepper says. “And it can create these weird rifts. At Illinois, you had a [football] player who felt violated, and other players who felt he needed to ‘man up.’ That can’t be good for team effectiveness.”

Tepper’s office sits steps from Ohio Stadium, where he knows the Buckeyes’ football coaches raise their voices at practice. What little he has heard doesn’t alarm him: “There’s lots of yelling, but it’s more exhortative and attention-getting, not degrading. There’s a fine line, and you can teach it to people.”

*****

Over time, abusive coaching will become discredited as more evidence accumulates that it doesn’t work. But for now the struggle against bullies with clipboards comes down to power and who exercises it. For an athlete to speak up requires someone suddenly living on her own to defy an array of authority figures, perhaps break with teammates and be willing to jeopardize a scholarship that can be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. If not for social media, the world would see Simon Cvijanovic as a has-been bitterly collecting his final credits at Illinois. Instead, Twitter allowed him to make his case and invite others to jump in and build it further. “There’s a little more rebellion against bullying coaches because athletes now feel they have a few more options,” Jim Thompson says. “If you don’t have any options, you don’t have any power.”

Ramogi Huma hopes the Illinois football and women’s basketball cases lead the NCAA to codify a baseline set of unacceptable behaviors. “A player should not be physically abused,” he says. “A coach should not use racially abusive language. If that’s universally defined as a starting point, a player could now say, Yes, something’s wrong with my coach. And that coach would be put on notice.”

Yet the problem may get worse before it gets better. One of the biggest successes in the crusade for athletes’ rights is the recent move by BCS schools to guarantee scholarships. As more colleges adopt that model, the coach who wants to get rid of a player can no longer simply refuse to renew a grant-in-aid at the end of the school year. Paradoxically and perversely, he or she will have only one tool left: Make life so miserable for those unwanted athletes that they leave of their own accord.