The islands' next great QB: Tua Tagovailoa, and the story of the man who inspired him to soar

This is the third part in a three-part series about football in the state of Hawai'i. Click the following links for Part I and Part II.

HONOLULU—He showed up for the first time at 8, uninvited, dressed in football pads, pants and a loose-fitting T-shirt, throwing bombs to receivers streaking downfield, ignoring the taunts of older quarterbacks around him.

"Dude, why does an 8-year-old throw better than you?" high school quarterbacks chided one another. Then they'd turn their attention to the skinny kid, trying to chase him off. "Go throw with the young guys!"

Tua Tagovailoa didn't listen. He had to warm up, he explained later, and a Sunday passing camp at Saint Louis School in Honolulu was the best place to do it. He had to be ready for his Pop Warner games.

There, against his peers, Tagovailoa took snaps and defensive backs dropped back 10 yards—about the distance most third-graders can throw the ball—before stopping. Tagovailoa zipped 30-yard passes over their heads and into the end zone, while befuddled opposing coaches stared on in disbelief. In Hawai'i, where the islands churn out dominant, imposing linemen who liken themselves to warriors in the trenches, most teams rely on stout rushing attacks. Now they had to deal with this?

Nine years later Tagovailoa, a dual-threat junior quarterback who has accounted for 3,507 passing yards, 725 rushing yards and 52 total touchdowns during his career at Saint Louis, is already being hailed as the next Marcus Mariota. A Saint Louis alum and the 2015 Heisman Trophy winner, Mariota rose from virtual anonymity to become college football's best player, lifting Polynesian culture into the spotlight. Tagovailoa watched Mariota's moving Heisman speech from back in Honolulu, aware that it would serve as a gateway, a movement. Now young Polynesians everywhere believe they can reach for more. Tagovailoa considers Mariota a mentor. "He set the foundation," Tagovailoa says, "for me and everyone else on the islands."

Like Mariota, he is driven to succeed, and win, for his culture and his people. But for Tagovailoa, it starts with one person: his grandfather.

*****

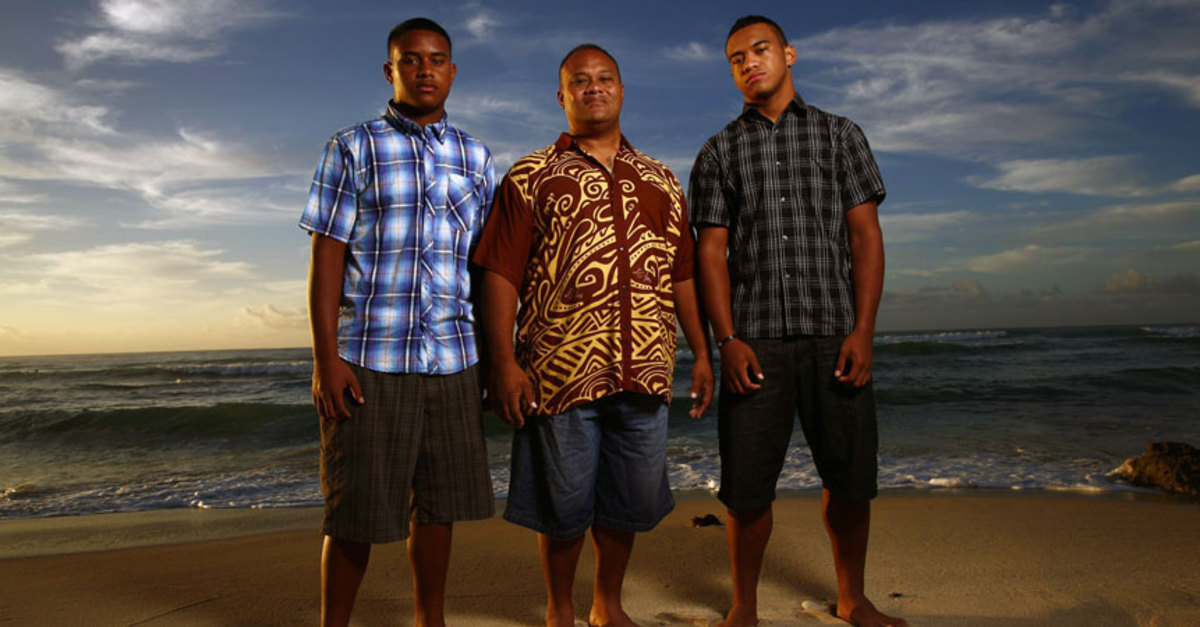

Kent Nishimura/SI

The story goes that Tagovailoa "came out of my mom tossing a football." He jokes, of course, but his parents, Diane and Galu (pronounced Na-loo), say it isn't far from the truth. Most kids get attached to a blanket or a teddy bear. Tua, the oldest of four, slept with a football tucked in the crook of his arm. At his grandparents' home in Ewa Beach, family members scolded Tua for playing catch when he should have been paying attention during prayers. His father recounts warily that Tua broke his share of window and door screens trying to increase his arm strength and perfect his accuracy. There were no broken windows, though; cousins and uncles knew when to dive and snag an errant pass before it shattered glass. This group breeds good receivers, too.

In the Tagovailoa family it was Tua's paternal grandfather, Seu—"Papa" to his grandchildren—who predicted Tua would grow into a football star. At Seu's home, which the family considers "headquarters," he requested Tua come over after every game, no matter how late, and detail how he played. Tua once went at 3 a.m. because he knew he'd get in trouble the next morning if he didn't. Seu shared with Tua his favorite Bible verse—1 Cor. 2:9 "No eyes have seen, no ears have heard, no mind has imagined what God has prepared"—and told Tua that God had destined him to be extraordinary. Seu believed something great awaited each of his 28 grandchildren.

For Tua it would be football. That's why, when outsiders suggest Tua reaches for the NFL solely because of Mariota's inspiration, Tua shakes his head. This has been planned for years.

The Tagovailoas considered Seu "the spark, the head coach of our family," and met daily at headquarters for spiritual lessons and family check-ins. When Tua was a child, Seu told him the story of the lion and the gazelle: One runs to get something, one runs away from something. When we wake up, we all have to run. So you better run toward something.

A deeply respected man in the community—family members say anyone who encountered him called him "Chief Tagovailoa"—Seu approached everything with a gentle but stoic disposition. Everything, that is, except the Big Boys League championship.

In Hawai'i, because so many young players come from big, thick Samoan and Tongan heritage, many hit the weight limit early in their Pop Warner days, rendering them ineligible. To combat this the state has created the "Big Boys League," where weight limits do not exist. Tua played in both. His high school coaches marvel now at how small he used to be, but explain, "his Samoan genes finally kicked in" around 12.

In the seventh grade, Tua's Sabres led the title game by a touchdown on their last drive, but wanted "one more score to seal the deal." Tua tossed a slant to a receiver, who skipped into the end zone for a final touchdown. Tua turned and saw Papa, in his orange shirt and camo shorts, standing and pumping his umbrella with joy, a smile stretched across his face. Tua calls it his favorite memory.

Tua is pushed by a father who dreams big for his son, partially because he once wanted those dreams for himself. Galu, Seu's oldest son, was a defensive lineman at Santa Rosa (Calif.) Junior College from 1989-91, but didn't play football after he finished. Like many oldest boys in Hawai'i, it fell on him to return home and help the family financially.

Galu doesn't regret coming back, but says a part of him always craved more. He told himself if he ever had a son, he'd go further.

Conscious of the immense pressure heaped on Tua's shoulders, Galu says his son does not consider it a burden. Throughout the Tagovailoa family and, really, all of Samoan culture, it is a great honor to be seen as the one who will rise. "This is big for our family," Galu says. "My dad's dream was to see this. He saw Tua's talent and prayed for it."

To Tua, Papa was so strong, respected and dismissive of fear that "I thought this man could never die." Then, on July 23, 2014, a case of pneumonia took his life.

*****

Kent Nishimura/SI

Tua wanted to quit. What joy could he find in football if the first person to believe in him was gone? Heartbroken that Papa would never watch him start a varsity game, Tua wallowed through the summer of 2014. Though Tua contemplated giving up the game, Galu and Tua agreed that the best way to honor Seu was for Tua to continue playing.

Still, he ached for Papa. Seu envisioned Tua becoming a varsity quarterback but did not live to see it; when Tua talks about this, his voice trails off. Galu steps in, explaining that in Samoan culture, it is a great honor to have your name known. Not because it brings attention to the individual, but because a village, and a people, are glorified as one. Mariota is hailed as a hero both for his achievement and because he understands he is only one piece of an intricately woven Polynesian fabric. His name being known honors him, but it honors the elders in his family more.

"Hearing his name called over the loudspeaker, our name, that would have brought him, the head of our family, so much pride," Galu says of Seu. In an ancient Samoan tradition, the paternal grandfather names the firstborn child. So "Tua" comes from Seu.

Tua and Galu tell this story one September night at Papa's home, which still serves as headquarters. The family gathers every evening for prayer and teaching, opening with a Samoan hymn.

Faafetai i le Atua

Thank you God, our Creator

Le na tatou tupu ai

For his everlasting love

Ina ua na alofa fua

Upon all of us

Ia te'i tatou uma nei

(freely available)

Ia pepese, Ia pepese

Sing sing

Aleluia Faafetai

Hallelujah, Thank you

Faafetai i lona Alo

Thank you to your son Jesus

Le na afio mai luga

Who came down from above

Le ua fai ma faapaolo

The one who is our refuge

Ai le puapuaga

From our hardship

Their voices swell at the final verse, asking God to be present in everything they do.

Faafetai i le Agaga

Thank you Holy Spirit, My Helper

Le fesoasoani mai

I am blessed with my prayer

E manuia ai talosaga

I pray always with the Holy Spirit

Atoa uma mea e fai

In everything I do

This was the way of life in ancient Samoa, and that they have brought to America: Around the same time every evening in the village, people understand they are to congregate and look heavenward. In Ewa Beach this night, Uncle Tuli Amosa—his wife, Sai, is Galu's sister and she and Tuli form Tua's "spiritual parents"—reads from Romans 8:35-37, which assures followers that no trial can separate them from God's destiny. God has a game plan for our lives, Tuli says. Will you trust it?

Tua understands that if he goes to the mainland to play college football, he would temporarily walk away from an unrivaled support system. But he can look around the table on this night—14 adults and most of the family's 28 grandchildren are present—and describe how each person has taught him to how to be independent and trust in his dreams. His grandfather would want him to run toward something.

*****

Kent Nishimura/SI

As a sophomore at Saint Louis, Tua blossomed. Standing at 6' 1" and 210 pounds with a powerful arm, an ability to escape would-be tacklers and terrific accuracy, he caught the attention of multiple Power Five programs. His quarterback coach, Vinny Passas, says Tua is so accurate that "when a ball hits the turf at practice it's like, 'Whoa, what happened there?'" Saint Louis coach Cal Lee, who has won 15 state championships, says Tua's natural ability is some of the best he has seen in more than 40 years of coaching. He admires Tua's hunger, too: In a 28–17 win over 'Iolani School on Sept. 18, Tua did not play because of a bruised right calf. But he shadowed Lee all game, innocently toting a football and occasionally drifting into Lee's view as if to say, If you need a first down, I'm right here.

Four games into the 2014 season, UCLA coach Jim Mora called with Tua's first major scholarship offer. Convinced it had to be a prank, Galu called Lee and asked if he could confirm its authenticity. Now, midway through his junior season, Tua holds offers from UCLA, USC, Ole Miss, Texas Tech, Nebraska and Utah, among others. Oregon has expressed interest, but has yet to extend a scholarship. Almost everyone in Hawai'i is a Ducks fan because Mariota starred there; Tua, who owns an Oregon jersey, falls into that camp, too. He grew up rooting for USC, mostly since the Trojans were the only team consistently on TV. He is both intrigued and uneducated about the SEC, because he is typically snoozing when those games kick off.

The University of Hawai'i is recruiting Tua, but Galu wonders if its attempt is half-hearted. If the Rainbow Warriors really went after him, Galu says, it would be tough for Tua to turn them down. Playing in front his family and representing his culture in his homeland could be incredible. Hawai'i, with its aging facilities and mediocre history, struggles to keep the state's best players at home, particularly in the wake of Mariota's triumphs on the mainland.

Passas, who coached Mariota, says it's unfair to compare the two quarterbacks, although he acknowledges they have similarities. "The biggest difference between [Tua] and Marcus at this age is just that Tua's had more reps," Passas says, referring to Mariota not starting at Saint Louis until his senior season. Passas also believes Tua has only hinted at how good he could be. Tua excels in competitive environments and doesn't get pushed much by backups at Saint Louis.

In truth, the most competition comes at home: Tau, Tua's younger brother, is the next quarterback in the Tagovailoa clan, a 5' 11", 195-pound starter at Kapolei, the public school where Galu is the offensive coordinator. (Tau's full name is Taulia, Samoan for battle strong, a fitting choice for a younger sibling.) The brothers talk trash at the dinner table, but Tua admits that he likes when they study film together. "I never wanted him around when we were younger, except to hike me the ball, because he used to be the center. Now I love playing and talking the game with him."

Galu got hired at Kapolei just before the 2015 season and asked Tua if he wanted to transfer. Tua rolled his eyes. "Nah, dad, we're gonna kill you guys. Why would I want to leave?" Like so many quarterbacks before him, including Mariota, Tua treasures the brotherhood of Saint Louis football. Drawn in by the iconic, tight-knit program, he believes playing for the Crusaders is what Papa would have wanted.

Tua remembers his grandfather in ways big and small. "Papa" is etched faintly on the front of his helmet, a silent reminder who he plays for. Before games, he watches a video from Seu's time in the hospital in which Seu speaks a Samoan blessing praising and thanking God for his grandchildren, lifting them up and asking that their gifts be fully realized. Tua then says his own prayers, asking for guidance and wisdom in his reads, that his linemen have quick feet and his receivers good hands. Though he misses Papa every day, Tua remembers that Seu watches over him.

It's a mistake to label Tua as the next manifestation of Mariota. Yes, Mariota's success made it so everyone knows about football in Hawai'i. But in the islands' golden hour, Tua desires for his name to be known. And not just Tua, but his full name, Tuanigamanuolepola Tagovailoa.

Galu hails from the Samoan villages of Vatia and Aua, which are connected by a mountain ridge. Tua is named for a bird that circled the islands and, when caught and killed, was divided among the Tagoilelagi, paramount family, Ga'ote'ote, his sister, and the village. His name is a record of this tradition, and it is a great honor that his grandfather, tasked with passing on ancestral legends and stories, asked that Tua be called this. It means Tua plays not for himself, but for all who nurtured him.

Vatia, with its lush rainforests and limited development, isn't well known by outsiders. Tua can change that. Many Samoans exhibit tautua, a selfless and fearless service for the good of the 'āiga, family, and the village. But as Tua soars, he transcends this, elevating his family, his people, his community, calling out for others to follow. He brings recognition and honor to a sacred space. Do not celebrate Tua, he says. Celebrate Tuanigamanuolepola Tagovailoa. Celebrate us.