After the quake: Skal Labissiere’s incredible journey to Kentucky

It was like a vision, he says, when a wall of his family’s third-floor apartment split wide-open, and before him in the late-afternoon light flashed their Port-au-Prince neighborhood, Canapé Vert. Inside and outside were merging, and then everything was caving in. In the violent rumbling of a 7.0 magnitude earthquake that began at 4:53 p.m. on Jan. 12, 2010, and ravaged the Haitian capital, he was descending. Three stories became one pile of concrete, rebar, walls and possessions. The light disappeared.

At first, Skal Labissiere could only hear, which at least meant he was alive. His nine-year-old brother, Elliott, was crying out, which meant he was alive too. Their mother, Ema, was nearby—the three of them had run into the living room when the tremors started—saying prayers to get right with God, which meant she was alive but maybe not expecting to be for long.

Skal tried to get right with God too but became upset. “I’m 13,” he yelled to his mother. “I’m not old enough to die.”

“We die at any age,” she replied. “This is life.”

Skal didn’t like that answer. He’d been taught that it was O.K. to pray for outcomes, and what he’d prayed for most was to move to the U.S. to play basketball. On clear days from the Labissieres’ apartment, located between the National Palace, downtown, and the wealthier homes of Pétion-ville, he could look a few miles south to the ridge of Boutilier mountain, the green trees interrupted by a cluster of antennas and dishes—the hardware that relayed images of the NBA to Haiti, and to the eyes of a boy in the Western Hemisphere’s poorest nation, home to 10.3 million people and not a single hardwood basketball court.

There was little he could see now. Not the mountain; not the second-floor neighbor boy, dead and buried well below; not his father, Lesly, who had been in the courtyard after returning from work. There was no earthly way Skal could have ever seen that this calamity was his way out of Haiti—that in this life, which guarantees no fairness in its outcomes, an earthquake that killed more than 100,000 would also fast-track him to the U.S., where over the next five years he would develop into the top-ranked recruit in the class of 2015, a 6' 11½" power forward navigating different kinds of chaos on his way to the 2016 NBA draft.

A fallen wall pressed on his back and forced him into a painful crouch, butt over heels, elbows over knees. He could hear people screaming outside. He prayed in a small, slanted space, trying not to choke in the dusty darkness.

*****

Skal Labissiere begins his days in the black predawn. On a Friday in June, outside a YMCA in Olive Branch, Miss., a suburb southeast of Memphis, there is no wind to muffle the wake-up chirping of the birds. Beyond a chain-link fence, the surface of the outdoor pool-slash-waterpark is a mirror, reflecting the Y’s exterior lights. The interior lights flicker to life just before opening time, 5 a.m. At 5:04, a gray Chevy Avalanche pickup truck pulls into the parking lot.

Andreus Shannon, a skills trainer, and his 19-year-old student emerge. The student is long and slender, with the beginnings of an Afro atop a high forehead; he has a gentle smile and skin at least one shade of brown lighter than he had as a young boy, when he played soccer for hours under the Hispaniola sun. On his feet are the red Nike Hyperdunks that he received last April while starring in Portland at the swoosh-sponsored Hoop Summit, as the lone player with Haiti on his jersey. His shoes are already tied tight.

The kid checking him into the gym asks, “When you heading to Kentucky?”

“Less than a week,” Labissiere replies, smiling.

“They say you’re gonna be a starter.”

“I can’t wait.”

“Hey, do me a favor. When you play Carolina, don’t beat ’em.”

• MORE: Predicting the top 20 big men for 2015-16

Labissiere (La-BISS-ee-air) laughs and dribbles down the hallway, declining to promise mercy in a possible NCAA tournament meeting with North Carolina, one of the favorites to win the 2016 national title—along with Kentucky. He is indeed expected to start this season, the next big thing in a frontcourt that has produced 10 first-round picks in the last six NBA drafts, but none with a road to Lexington like Labissiere’s.

He and Shannon have the court all to themselves. The only competing noise is the buzzing of halogen lights. A one-handed shot from the right block goes up at 5:13 a.m., the first in a progression that eventually takes Labissiere beyond the three-point line, with steady commentary. “Bring your arm like this,” Shannon says after a baseline misfire, mimicking a fully extended follow-through. “Remember to lock your elbow.” These corrections are minor; Labissiere is an impressive shooter for his size, with a fluid release and high arc. It’s evident why many pro scouts have him atop their 2016 draft boards: He has a LaMarcus Aldridge–like offensive ceiling—as an athletic stretch-four who can shoot and run the floor—with the rim-protection instincts and agility to make up for a wingspan that’s considered just average . . . at 7'2".

Labissiere has been doing these workouts for three years, ever since his American guardian, Gerald Hamilton, watched local star Torri Lewis win a three-point contest and vowed to get whoever was training her to train Labissiere. Lewis is typically at the Y around 5 a.m. too, but she left for Ole Miss on a basketball scholarship a few weeks earlier, and Labissiere, on the verge of departure for Kentucky, feigns concern for Shannon. “What are you going to do now?” Labissiere asks in the lilting English he has worked so hard to master, after arriving in the U.S. speaking only French and Haitian Creole. “Are you going to cry today?”

Shannon holds back his tears, but he will miss a kid he’s never had to motivate. “Two years ago,” Shannon recalls, “Skal told me, ‘People talk like I’ve already made it, like I’m going to go to the league. What people don’t realize is, I haven’t made it, and that’s not what my goal is. I don’t just want to make it to the NBA, I want to be a Hall of Famer, the best of the best.’ ”

That goal has Labissiere doing multiple workouts before 11 a.m. At the second, with his strength-and-conditioning coach, Raheem Shabazz, Labissiere does seated, plyometric box jumps under a scalding sun. According to Shabazz, when Kentucky coach John Calipari made his official recruiting visit in September 2014, he took video of Labissiere leaping from a seated position on an 18-inch box and landing on a 36-inch box, and sent it to the Wildcats’ strength coach, asking, “Can any of our guys, right now, do this?”

The response: “HELL, NO.”

Today, when Labissiere sets a personal best of 46 ⅘ inches, Shabazz exclaims, “F--- you, J.J. Watt! You do yours standing up”—for those unversed in the oeuvre of YouTube box jumpers, the ultimate video depicts the freakish Texans defensive end landing a 61-inch jump—“but Skal does it sitting down!”

As Labissiere stands atop the boxes, a vista of an undeveloped cul-de-sac is there to savor. The box conqueror of mid-South suburbia, via Haiti, declines to take in the view. He descends, carefully, and gets ready to jump again.

*****

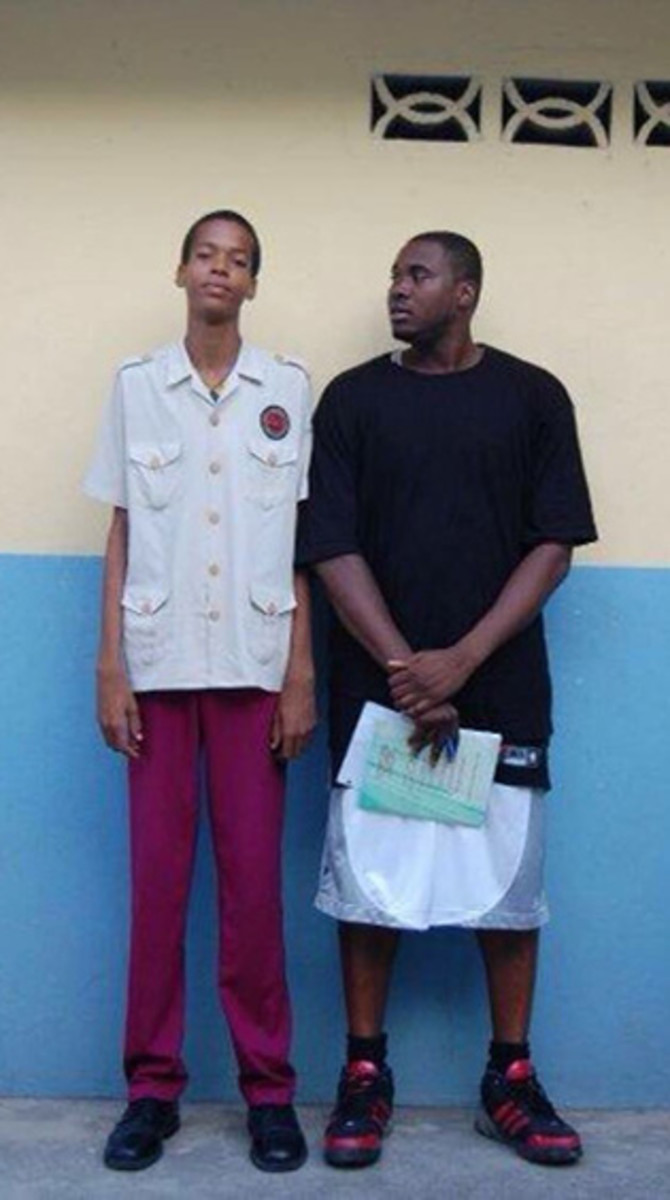

Lightning slashes the early-evening August sky, off in the lowland closer to the ocean. Traffic sputters along Avenue Delmas—Chinese motorbikes, tropically painted pickup trucks called tap-taps (that function as buses, with bench seating in their cabs), white trucks with un painted on their hoods, all dodging human overflow from the sidewalks. Smoke from a street vendor’s cooking fire creeps over the eight-foot concrete walls of Quisqueya Christian, a prep school whose grounds hide one of Port-au-Prince’s best basketball courts, a grid of blue plastic tiles atop asphalt. A game of two on two is in progress under the lights. Past the baseline there are empty bleachers and a beige wall—significant because it’s the backdrop of an artifact. “That,” says Jasson Valbrun, a former point guard at Labissiere’s old school (College Canado-Haitien) who is now the commissioner of Port-au-Prince’s interscholastic league, “is where the picture was taken. Skal and Titanic.”

The last known photo of Labissiere before the earthquake dates from Dec. 9, 2009. His Canado-Haitien academic uniform, a white, short-sleeve button-down with epaulets, hangs loose from his bony shoulders. He is a wisp. Next to him is Pierre Valmera, whose boat-sized feet inspired his nickname. He grew to a wide-bodied 6'8" and, from ’03–04 through ’06–07, was part of a succession of Haitians who played for Union University, an NAIA school in Jackson, Tenn. While on a break from a pro season in Switzerland, Valmera was laying groundwork for a foundation he’d eventually call POWERForward International, collecting contact info for Haitians worthy of invites to local camps—Labissiere had been nominated by his coach at Canado—and maybe recommendations to U.S. colleges.

Labissiere, deducing that Valmera was his best shot at playing in the U.S., followed up with a Facebook message on Dec. 26, 2009. Valmera phoned Labissiere’s father during the second week of January, just days before the earthquake, but Valmera had never helped anyone younger than 18 get to the States, and Labissiere felt there was little chance his parents would allow him to be the first. They were protective, and had carved out a disciplined, stable existence for their kids amid Port-au-Prince’s third-world poverty: Ema was a kindergarten principal and radio journalist, Lesly a carpenter who doled out whoopings if his boys stepped out of line, telling them they weren’t allowed to cry. “My father would not have sent me off to live with some strangers,” Skal says. “It’s not like I was living in a bad situation.”

Until the earthquake, that is—which Skal survived due to a streak of fortunate events, a streak that continued even after he was pulled out of the rubble. When the apartment building fell, a computer desk bore much of the weight of the wall that was pressing against Skal’s back. Lesly had built furniture for the apartment, sturdy wooden pieces, including the boys’ bunk bed—and that desk. It is possible that his craftsmanship kept his son from being flattened.

At the time of the quake, Lesly was lingering in the courtyard, trying to straighten the Fisher-Price hoop that his boys had dunked out of whack. After the building collapsed, and with the help of neighbors, he began excavating, carefully, with the one tool he could find: a weightlifting bar. It took three hours to dig his family out, and although Skal’s painful crouch left him unable to walk at first, he was back on his feet in two weeks, thanks to his mother’s consistent massaging of his leg muscles.

By then the Labissieres, like many survivors, were living in a tent. It was pitched just outside Ema’s kindergarten, where some facilities still functioned. But Skal’s school, Canado-Haitien—four stories of brutalist concrete in Canapé Vert—had been destroyed. With his life and education in disarray, his parents were receptive to alternative living arrangements.

Or as Gerald Hamilton puts it, “That’s when the Lord sent the little chubby guy—that’s me—to come get [Skal].” Shortly after the earthquake, Valmera was contacted by Hamilton, an information technology specialist from Olive Branch who had learned about Union’s connections to Haiti. A basketball junkie and church youth-group leader, Hamilton says he became fascinated, a decade ago, by a story he read about a Sudanese refugee who was playing basketball, and tried, unsuccessfully, to offer guardianship. “He never got that idea out of his system,” says Hamilton’s wife, Sheneka, and in 2009 they received 501(c)(3) status for a charity, Reach Your Dream, which aims to help disadvantaged international athletes. By February 2010, with Valmera’s help, Hamilton was working on a plan to bring two Haitian prospects—Labissiere and Samuel Jean-Gilles, a 6'2", 17-year-old guard—to live with his family and attend Evangelical Christian School in nearby Cordova, Tenn.

In July 2010, on their second trip to the U.S. embassy in Haiti—after Hamilton flew to Port-au-Prince to meet the boys’ families and provide documentation about ECS—the two teens were approved for visas. In August they flew from Port-au-Prince to Miami, then Dallas, then Memphis, where they were picked up by the Hamiltons. Labissiere was the less-advanced player of the two, but it soon became clear he was the bigger prospect: At his first national showcase, the Fab Frosh Camp in Atlanta in July 2011, he was named MVP. Recruiting letters followed, first from Detroit, then Tennessee, Arkansas and North Carolina. Labissiere was unbothered that most of them misspelled his first name “Skai.”

Labissiere became fluent in English and fell in love with college hoops while following Kentucky’s 2012 national title team on TV. As he watched ESPNU’s late-2012 Kentucky All-Access show, which included Nerlens Noel, a center with Haitian parents, Labissiere began praying for the Wildcats to offer him a scholarship. “I have faith, and there’s nothing wrong with asking,” Labissiere says. “And literally three or four weeks later, [Calipari] comes to my first game as a sophomore and then calls and offers me.”

Appreciating all that John Calipari has achieved en route to the Hall of Fame

Calipari told Labissiere that he could be the next in the coach’s line of athletic, rangy big men he’d groomed for the NBA: Marcus Camby at UMass, Anthony Davis and Noel at Kentucky. Labissiere was proud to hear that, but he did not commit right away. He subsequently became one of the hottest attractions on the recruiting trail and the most sought-after Haitian-born prospect of all time.

The competition for that title is . . . limited. The first Haitian to receive a Division I scholarship was 6'11" Yvon Joseph, who was spotted by a Miami juco coach while playing on Haiti’s national volleyball team—at 22. Joseph went on to Georgia Tech and played one game in the NBA, in October 1985, for the New Jersey Nets. The first truly hyped Haitian prospect was 6'11" Olden Polynice, who was drafted No. 8 by the Bulls in 1987. It took 14 years for another Haitian to be drafted, when the 76ers took 6'11" Samuel Dalembert at No. 26. The Seton Hall product, who went to high school in Elizabeth, N.J., is the nation’s only active player in the NBA.

None of the Haitians who played at Union over the past decade were NBA (or even D-I) prospects, but they still relished the opportunity. “What Pierre told me before I went,” says Antoine Joseph, 25, who followed Valmera at Union, “was ‘Don’t break the chain.’ ”

In the summer of 2014, Joseph got an indication that Labissiere would be more than another link in the chain. Joseph and Valmera were visiting Las Vegas to check on POWERForward camp alums playing in AAU tournaments. “All these big-time college coaches, guys I’d only seen on TV before, were looking for Skal, saying, ‘What court is he on?’ ” says Joseph. “As a Haitian, I was proud. Skal had been this tall kid with a little talent, and he transferred all his energy and talents into a bomb. He just blew up.”

*****

Blow up like Labissiere has, in the high-stakes market of American youth basketball, and sometimes you become a controversial prospect even without being a controversial person. It is hard to square the Labissiere one meets—he says “Yes, sir” and “No, sir” to elders; does chores in the Hamiltons’ two-story, brick home in a quiet subdivision; works as a janitor at their church; has no driver’s license; and says, without any hint of lament, “Even though I’ve been [in Olive Branch] for five years, I don’t get out of the house that much, unless it’s to go to school, the gym, church, or hang out with family”—with the tone of a recruiting narrative that has spun out of his control and has him still waiting on NCAA clearance to play at Kentucky.

“Skal is a very good kid,” says Valmera. “He’s just around a funny situation.”

At the center of this situation is Gerald Hamilton and the conflicting opinions over whether he and Reach Your Dream are doing the Lord’s work of bettering a student-athlete’s life (as he and Labissiere assert) or using a prospect to leverage donations to a 501(c)(3) charity. According to one college coach who recruited Labissiere, but did not sign him, Hamilton controlled access to the extent that “you were not allowed to talk to Skal, and the only way you could know he liked you was if he liked your Instagrams.” The coach also told SI that he was asked by an NCAA investigator, in 2015, if Hamilton had requested money for Reach Your Dream. (The coach’s answer was no.) This came in the wake of a November 2014 allegation by a former Memphis AAU coach, Keith Easterwood, who told CBSSports.com that Hamilton had called him in 2012 and asked, “How can I make money off of a basketball player?”

Hamilton refused to comment at the time but told SI in June that he has a text message exchange proving Easterwood was the one who’d asked the damning question. Hamilton says that when he showed their text exchange to Kentucky’s compliance staff, “they almost started laughing, and said, ‘This is it? Are you serious?’ They said we were fine.”

Hamilton and his wife declined SI’s requests to see the texts, on the grounds that they don’t want to fuel more controversy. Easterwood says that after he provided information to the NCAA, he was asked not to talk publicly about Hamilton. Calipari said on Aug. 1 that he is confident Labissiere will be cleared to play.

If they were trying to cash in, the Hamiltons say, they would’ve accepted the pitch from Ole Miss. The Rebels’ coach, Andy Kennedy, had offered Hamilton—whose highest coaching experience was as a prep-school assistant—one of the program’s three full-time assistant positions, hoping to net Labissiere in an NCAA-legal package deal. “That was real,” Hamilton says, “but I told them when they offered, I’m going to have to talk to Skal, but if he’s not interested, then we’re just going to keep moving. And that’s what happened.” (Kennedy says he does not recall that conversation with Hamilton.)

There are also conflicting explanations for what happened to Jean-Gilles, the other Haitian who moved in with the Hamiltons in August 2010. In the summer of ’11 they put him on a bus to Boston, where he had relatives, and told him to finish high school there. An ECS coach told The [Memphis] Commercial Appeal that Hamilton had asked him about Jean-Gilles’s potential to receive a D-I scholarship and was told it was unlikely. This allegedly happened in the days before Jean-Gilles’s departure, and he believes that conversation was the catalyst. “They didn’t think I was going to make it as a scholarship player,” he says.

Inside DeAndre Ayton's rise from the Bahamas to 2017's No. 1 prospect

The Hamiltons, who later blocked a Memphis family’s attempt to assume guardianship of Jean-Gilles, told the paper that he was sent away for being a “bad influence.” Labissiere says Jean-Gilles was “sent away for a reason” but will not elaborate. Valmera, who believes Jean-Gilles’s version, has vowed never to allow Hamilton to work with Haitian prospects again.

The most distressing scrutiny of his guardians, Labissiere says, came just before Christmas 2014, when an investigator from the Mississippi Department of Human Services showed up at their house, requesting to interview him and the Hamiltons’ three children. “She came into my room and asked questions like, Was I being mistreated? Did I like it here?” Labissiere says. “I told her I liked it here. We were just like, Is this some kind of joke?” The investigator, Hamilton says, explained that someone—she couldn’t say who—had called and alleged wrongdoing. They say the investigator found no evidence of it, apologized and left. They still do not know the source of the complaint.

On one of Labissiere’s final nights before departing for Kentucky in June, he gathered with the extended Hamilton family in the living room. A large, cardboard cutout of Labissiere’s head—a souvenir from the Jordan Brand Classic—sat atop a ceramic floor vase. They watched the original Jurassic Park on E!, and Labissiere received a pedicure from a family friend who had brought over her footbath and kit.

Earlier, he had been soccer-juggling a basketball in the driveway with his best friend, Aldair Carlos, who came to Memphis from Angola. They met at Lausanne Collegiate, the private school Labissiere attended after transferring from ECS following his junior year. In yet another chapter of this saga, the transfer led to Labissiere’s being ruled ineligible, so he played his senior season for Reach Your Dream Prep, a team affiliated with a fledgling school that Hamilton created—but that Labissiere did not attend.

An international player’s dream has been derailed before by the NCAA—Turkish recruit Enes Kanter never played a game for Kentucky in 2010–11—but Labissiere believes his case is different. “I’m going to be eligible,” he asserts. “We didn’t do anything under the table.”

*****

Still, reporters asking about Labissiere are regarded with caution. When SI first contacted Hamilton, in December 2014, he said that Kentucky had asked him and Labissiere not to give interviews. (They broke their silence in April.) In Port-au-Prince, the arrival of a reporter is met, by some of those close to -Labissiere, with trepidation, the fear that one wrong word could jeopardize his future. In one case it takes three days to persuade Labissiere’s coach from Canado-Haitien, Jhon Guerrier, to meet near the school—and then have him state that he’ll only consider doing an interview in New York City, where he’ll be traveling on Sept. 1. (He never showed in New York City.)

Meanwhile, Labissiere asks that his parents not be interviewed, and Hamilton says not to write “anything about [Labissiere’s] parents” for fear of drawing unwanted attention to them in Haiti. It’s a peculiar request, but Labissiere could soon become the most valuable human export of a nation that is still plagued by kidnappings for ransom. (After reaching out to Lesly through Valbrun, and confirming the family’s reluctance as well as a few key details, they were left alone.)

64 reasons to be excited for the 2015-16 college basketball season

Haitians outside of Labissiere’s inner circle, though, speak about him with a sense of wonder. A visit to Canado-Haitien, where teenagers play pickup games in the rebuilt school’s asphalt courtyard, turns up a classmate from Labissiere’s final year. Kevin Brillant, now a 19-year-old university student, heard an update about Labissiere on a sports radio show and was amazed that the friendly Skal, who used to talk with him about Kevin Garnett and the Celtics and who almost always wore an extra shirt under his school uniform—rules forbid playing basketball in dress whites—was on the verge of fame. Brillant says he watched a YouTube mixtape of Labissiere and concluded, “He’s not the skinny kid from our school anymore.”

The address Labissiere provides for his old apartment—35 Rue Jean-Baptiste, the building that crumbled and set him free—is near the school. Finding it requires paying a taxi driver and following his maroon Haojin motorbike off Canapé Vert’s main drag, down a dirt road to an unlabeled, three-block stretch of cracked pavement. Many of the street’s gates lack numbers, and many no longer protect dwellings. Behind one is a concrete slab, empty except for a weightlifting apparatus, configured for lat pull-downs, rusting in the sun.

A group of young men sitting on benches under the shade of a tree take interest. One ventures a guess, in Creole, as to the purpose of this unexpected visit. The word that’s clear without the assistance of a translator is Labissiere.

Emmanuel Joseph, 29, points to a newly constructed, two-story yellow house, behind a metal gate with a padlock, and says it’s where the Labis-sieres used to live, in a rented apartment on the top floor. Someone else recently rebuilt on the site. “The construction is so fresh,” he says, “that you can still see their old gate inside, where the kids used to have a little basketball hoop.”

The men remember Labissiere as a frail kid and his family as the kind that never disturbed anyone in the neighborhood. After 35 Rue Jean-Baptiste fell, Joseph says, he was one of those who helped Lesly pull the rest of his family out of the rubble.

It was common for Haitians to lose track of neighbors who survived. People scattered, resettling anywhere they could find safe shelter. It was in the past year that Joseph, a basketball player himself, heard talk of another Haitian possibly joining Dalembert in the NBA. Joseph googled for details and made the wide-eyed discovery that the Haitian was Labissiere. It was neighborhood knowledge that the boy had left for the U.S., but his progress had not been reported.

“Someone coming from Haiti and becoming the first pick in the NBA is like a dream,” Joseph says, pointing heavenward for emphasis. “People here will see this and work hard to become the next Skal.”

Joseph insists that Haiti has plenty of athletes, if only people would come to find them. Just sitting next to him, he says, is a soccer player and two more basketball players. Good players, in their 20s and 30s, who never had opportunities. It is early on a Friday afternoon, and the lone car parked on Rue Jean-Baptiste, down past Labissiere’s childhood courtyard, is a tap-tap with a line of Creole in fading paint on the side of its cab. Plante yon ti pye bwa jodi a l ap bon demen, which means, roughly, Plant a tree today, and it will be good for tomorrow. An old Haitian saying about the future, enduring into a present where planting isn’t always best for the seed. For Skal Labissiere to grow, he had to be carried off on the wind.