Football and family: How D-III Linfield College became power on verge of history while overcoming tragedy

With additional reporting by Sara Gomez.

On Saturday, if all goes as planned, Linfield College will extend one of the more improbable streaks in sports. For 59 seasons now, the Wildcats have won more games than they've lost, an all-divisions record for college football. Most years, as in last season's 11–2 campaign, the wins are abundant. Other times, it comes down to one game. To coach at Linfield is to wake up every morning shouldering a half-century's worth of expectations.

From the outside, the program makes little sense: A football powerhouse at a liberal arts school in a small Oregon town known for pinot noir. A Division III team that attracts Division I talent, including one current NFL prospect. A star quarterback who turned down a big-school scholarship to be close to his son. A program that owns four national titles, draws 3,000 fans per game, wins by scores of 77–10 (last Saturday's final) and is ranked third in the country yet has one of the lower budgets in the league, offers no athletic scholarships and works out in a subterranean weight room seemingly lifted from the training montage of an '80s movie.

And yet, year after year, Linfield wins. Since Eisenhower was in office. Since the Dodgers were in Brooklyn. An .808 winning percentage. That kind of consistency isn't normal. Surely, there must be some sleight of hand—or magic—at work. How else does a team win eight out of every 10 games for 60 years?

Granted, I have an unusual perspective on the subject. I arrived at Linfield this fall as an outsider, on campus a few days every other week to teach a class on narrative nonfiction. Immediately, I began hearing about the football team: the success, the streak, the culture. I also heard them, literally. The coaches blast music from the scoreboard speakers during Thursday practices, hoping to mimic game noise and goose team energy, and it washes over the campus. Classes are taught to the faint strains of the theme from Rocky, campus strolls accompanied by booming bass.

The college itself isn't easy to find, a bucolic, tree-lined campus nestled in the small town of McMinnville, an hour and change south of Portland. To get there, you detour off I-5 through farmland and strip malls. Depending on which route you take, you might pass McMansions, gastropubs and swanky tasting rooms (the surrounding area is Oregon's wine country). Arrive from a different direction and you're in the land of Dollar Trees, sketchy liquor stores and pawn shops eager to buy your gold and sell you "Used Guns."

Linfield is the town's cultural and intellectual center, a school of 1,680 steeped in the liberal arts tradition: a 13:1 student-to-faculty ratio, a strong arts program, a focus on mentorship. As far as I can tell, everybody says hello to everyone else on campus; as a former New York City resident, it took me a while to adjust to such blatant geniality. Academically, Linfield's peers are schools like Ursinus and Lewis & Clark. Athletically, however, it competes on a different level. The softball team owns two national titles. The baseball team has won three and, up until this year, was coached by alum—and former World Series MVP—Scott Brosius. To walk into the Rutschman Field House is to enter an athletic shrine: gleaming championship trophies, Brosius baseball cards, a plaque commemorating longtime football coach Ad Rutschman's induction into the College Football Hall of Fame. (Rutschman is the only coach to win national titles in both baseball and football.) And, off to one side, a glass case dedicated to quarterback Brett Elliott, who led Linfield to the 2004 championship after transferring from the University of Utah, where he backed up Alex Smith.

One floor up, in an airy meeting room, the football team holds weekly press conferences. When I first heard this, I was skeptical. A press conference? For a D-III team? I played D-III sports, at Pomona College, and never saw a reporter on campus, much less enough for a "press conference."

But there it was, this past Tuesday at noon: a small but legit presser. Video equipment, three radio guys, a beat reporter from the local paper. Before playoff games, I'm told, the crowd grows to 10 or more. At noon sharp, head coach Joseph Smith walked in. A compact man with short blonde hair whose default expression is a steely squint, Smith was an All-America defensive back at Linfield in the early '90s. He's only the fifth head coach during the streak, all of whom were mentored by predecessors, a huge point of pride around campus. When Smith took the job in 2006 he saw himself not as a coach but a "caretaker." The previous coach, Jay Locey, left unexpectedly to take an assistant job at Oregon State. "It couldn't be someone from the outside to come in and run the program," Smith says. "We had to maintain who we are. If we lost that, we're just another school."

Smith's leadership style could be described as one part chain-of-command militarism and one part motivational guru. He nearly attended Virginia Military Institute; his brother was a military pilot and for years he thought he might be one too. Instead, he got hooked on sports psychology, first at Linfield and then at Oregon State, where for his master's thesis he studied team cohesion, choosing as his test case ninth grade girls basketball. (His conclusion? "It's all about buy-in.")

Now, Smith runs scripted, regimented practices (that are filmed), the scoreboard clock forever ticking down to the next drill. On bus rides, he shows movies such as Braveheart, Gladiator, We Were Soldiers and The Last Samurai. He echoes Army Ranger terminology, telling players the world is made up of sheep, wolves and sheepdogs. "Most people are sheep," Smith tells them. "And then there are the wolves, who are the predators. And then there are the few who are like wolves, strong and with sharp teeth, but their purpose is to protect the sheep from the wolves. We are the sheepdogs."

Smith is also a believer in the input-output theory of cognitive psychology, which he endeavors to translate into 18-year-old-ese. The gist of it: What you allow into your head forms attitudes, your attitudes direct your behavior and your behavior directs your output. It is thus crucial to guard against negative input. For this reason, Smith rarely watches the news or reads the newspaper. "Why would I?" he asks. "Every time I do, it just bums me out."

Now, answering questions from a local radio guy with a velvety voice, Smith does his best to make a 77–10 win sound like a learning experience. Even though we are four days from the potential clinching victory, it is 23 minutes until the beat writer brings up the streak. Apparently, this is normal. "The people from outside Linfield talk about the streak a lot, and it's a big topic during recruiting," says Kevin Nelson, Linfield's student play-by-play man. "But the team rarely if ever talks about it."

I suppose it makes sense. When your goal is the national title, winning more games than you lose isn't exactly a lofty aspiration.

Chris Ballard/SI

*****

It wasn't always this way. Flashback to 1998, when Linfield was good but not this kind of good. Two seasons earlier, the team had finished 5–4, the third time in history the streak came down to one game (most precariously, in 1987, the streak wasn't clinched until 35 seconds remained in the final game, a 17–12 win). At the time, the record for consecutive winning seasons stood at 42, shared by Harvard (1881-1923) and Notre Dame (1889-1932).

So, on October 17, 1998, when Linfield scored a touchdown with less than a minute left against Northwest Conference rival Willamette University, then withstood a furious final rally to win 20–19 and clinch a winning season, the 4,000 fans on hand went crazy, or as crazy as liberal arts kids can go.

In a very un-Division III-like moment, the students not only stormed the field but also started launching themselves at the goalposts. (You can watch the video here.) One hurtled skyward, then another clambered up, helped by a friend. Then more, and more. And soon enough, the posts started sagging. And, then, with a creak, down they came.

National coverage followed. ESPN, the Associated Press, USA Today, Sports Illustrated. Locally, the News-Register put out a special commemorative edition ("Media mongrels soak up streak," read one headline).

A golden era began. The Wildcats won the national title in 2004 and nearly repeated a year later. Three disappointing seasons followed, during which Smith dismissed players and coaches—"weeds grow in the garden, and you have to weed every day," he says. In the six years since, Linfield has won at an unprecedented clip.

It should have been one of the best periods in the program's history. Instead, it became the darkest.

On November 15, 2014, hours after Linfield clinched a conference championship with a 59–0 victory, Parker Moore, a 20-year-old junior linebacker and resident advisor, walked into the 7-Eleven across from campus. Minutes later, according to police accounts, a 33-year-old local man named Joventino Bermudez Arenas approached and stabbed Moore twice. Moore died shortly after. For reasons that are still unclear, Arenas returned to the store and was shot to death by police. Investigators concluded it was a random, senseless killing.

The Linfield community was crushed. Grief counselors arrived. Students held vigils. Nearly 2,000 people attended a memorial. The football team was adrift. This was not a courageous battle against cancer, from which lessons could be mined. It was not just a tragedy, but a theft.

While the school grieved, Smith struggled with what to do next. Finally, he sat down at a laptop in his office, surrounded by pictures of his children and his wife, and wrote a long, moving letter to the community.

Chris Ballard/SI

Eventually, a tribute rose outside the stadium; two benches reading "LINFIELD STRONG" and a plaque on a boulder. Smith began a tradition, choosing an upperclassmen defender who best exemplifies the spirit of Linfield football to wear Moore's number 35 jersey every year. This season it is Kyle Chandler, who was Moore's best friend.

These days, the Wildcats bring Moore's framed jersey everywhere they go. It hangs above the tunnel during practice. It rides on the bus. It's in every picture. When Linfield traveled to Philadelphia for the national quarterfinals last fall, to play Widener, Moore's jersey hung in the Eagles' practice facility, where Philadelphia Eagles coach Chip Kelly—who previously led the University of Oregon to unprecedented success—let the team practice.

Talk to the players and they'll tell you Moore's death brought them closer. Bonded them in ways no practice ever could. They all had to grow up awfully quick. "As close as I was with my teammates, sadly it wouldn't have been like that if Parker wouldn't have passed," says Sam Riddle, the starting quarterback. "The family aspect got even stronger."

Family. It's a constant refrain. The Wildcats shout the word upon breaking huddles. Coaches occasionally bring their own kids to practice. Senior defensive end Alex Hoff, a unanimous first-team All-America last year, chose Linfield over Division I Portland State in part to play with his half-brother, Tyler Steele. Last season, Hoff—relentless, quick—attracted Chargers and Steelers scouts to campus. He ran the 40 and took the Wonderlic. If he doesn't get drafted as a defender, he's got a shot as a long snapper.

Then there's Riddle, who grew up quick a long time ago. Come to a game, like last Saturday's at home against Pacific University, and you'll see two Riddles wearing number 10: Sam and his 2-year-old son, Mason.

Two years ago, Riddle was at the University of North Dakota on an athletic scholarship. He also had a pregnant fiancée back in Oregon. He lasted less than a month before taking a 31-hour bus ride home, unwilling to watch Mason grow up via FaceTime. His father was pissed. You're throwing away a full ride to pay to play at D-III. (Linfield's annual tuition is $38,000.)

But Riddle made it work. He became the starter two games into his sophomore season and put up gaudy numbers. His fiancée (now his wife), Briahnna, got a job at Wells Fargo. He received financial grants and got a job in maintenance on campus. They found a place nearby, where she hosts teammates for taco salad dinners. While his peers play video games or sleep late, Sam's days begin at 7 a.m., when he wakes with Mason, At 8, Briahnna goes to work; Sam takes Mason to day care. Class is followed by homework, meetings, practice, and more meetings. He tries his best to make dinner, then puts Mason to bed and does homework for as long as he can stay awake. At first, his teammates ribbed him. Didn't you get the talk from your parents? How can you be 18 and have a kid? Two years later, the freshmen are in awe. "They come up and say, 'Like dude, you have a kid, you're married, what the!??' says Riddle. "They can't even think about what they'll be wearing the next day."

These days, Mason is the team's unofficial mascot, toted around on game days by "his 130 uncles," as Sam puts it. Some are alumni. Ryan Carlson, a defensive star who graduated in 1998, runs a fan site, operating a drone— "The Catdrone" as it's known—to film practice and games. Streaming radio broadcasts draw a thousand listeners, according to Nelson. And dozens of former players and alumni move back to town, to raise their kids the Linfield way. So strong is the alumni support that students rarely make up more than a quarter of the fan base. "Little old ladies come up to me after games with their husbands," says Hoff. "So do dads and their kids and I think, wow, all these people are watching and counting on me."

Chris Ballard/SI

*****

Now it's Tuesday afternoon. On the shiny artificial turf of Maxwell Field, on the east side of campus, the Wildcats—all 135 of them—practice on a warm fall afternoon. Some are star high school players who will never see a meaningful down in their careers. Two weeks ago, the second-string quarterback finally got to play, threw a long touchdown pass and was promptly criticized by opposing fans for running up the score.

Here at practice, Riddle drops back and throws a beautiful spiral into the waning sun—50 yards in the air—to Johnny Carroll, who hauls it in. Tall and fast, Carroll transferred from Oregon State. Which means the leader of the defense (Hoff), the offense (Riddle) and the two top wide receivers are all Division I-level players. (Wide receiver Brian Balsiger played two seasons at Portland State.) Those 77–10 margins start to make sense.

Next year, more talent will arrive. Beyond the northern goalposts rises a large white tent labeled "Recruits," full of up to 50 hopefuls during home games. Some, such as Hoff, also receive video pitches in the school's state-of-the-art library. They hear about the streak, and the program, and, of course, family.

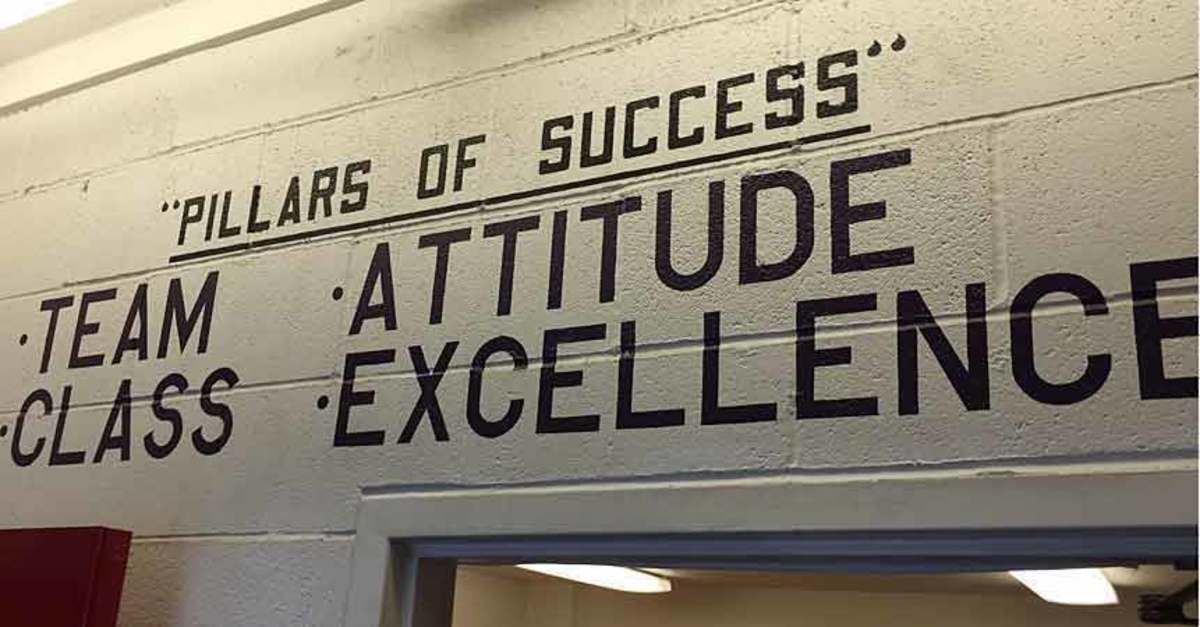

Now, as practice winds down, players jog toward the locker room, where team slogans adorn the walls. Input=Output. Attitude. Class. Some are quotes from the guest speakers Smith invites to address the team: police chiefs, fire chiefs, a military helicopter pilot and, earlier this season, political science professor Pat Cottrell. The theme is often character. For the vast majority of players, football is a hobby, not a career. How can they maximize their collegiate experience? How can they strive for excellence every day? The words of Bretton Brown, an Army Ranger and good friend of Smith's, are prominent. We are Men of Action. We do the heavy lifting. We are the walls, and we are the hammer.

Maybe this is part of Linfield's secret sauce, from Rutschman down to Smith: turning disadvantages into advantages. Focusing on life outside football to reinforce the game's principles. In Smith's case, he harps on players to make their bed every morning, because it's a small act that leads to sustained excellence, just as mundane actions—a proper snap, the right step off the line—lead to success in football. Why take the easy route when you can challenge yourself?

"Coming to Linfield, we don't have the luxury of getting brand-new uniforms every year," says Riddle. "We don't get our clothes washed every game, we don't get nice workout shoes, we don't get scholarships, we don't have a million jersey combinations like the Ducks. We're very blue collar." He pauses. "I think I'd rather be more blue collar, in a program like Linfield. It really builds character."

Courtesy of Brad Thompson

How much does football matter at a school like Linfield? The conventional wisdom is that Division III is about student-athletes, in that order. But this is more like a D-I program grafted onto D-III, at least when it comes to football. The team is a huge draw for alumni. And without those 135 players, the student body would skew even more female. (It's already 62% women on the McMinnville campus.)

Still, to my eye, the sport does not overwhelm the school. The students in my class were all profoundly affected by Moore's death, but they view the football team from an almost anthropological vantage point, holding it up to the light and examining it. Being a liberal arts school, they are given less to crazed fandom and more to educated curiosity. Sara Gomez, a student who helped in reporting this story, never seemed cowed or in awe during the process. After all, since a campus like Linfield's is so small, everybody knows most everyone else. Alex Hoff might be a star to alumni, their version of a Marcus Mariota, but at Linfield he's just another groggy kid waiting for a caffeine fix at the campus Starbucks.

This is not to say some at Linfield don't chafe at the impact of the football program. A women's soccer player tells me her team's field is pockmarked, a sprained ankle waiting to happen. She wishes her program received the same resources. Students who work the school phone-a-thon say older alumni call to donate but specify that the money go to the football team.

Then again, no one on the team is getting paid. There are no scholarships (and, according to Smith, the operating budget is in the bottom quarter of the conference, and both he and two assistants also teach or hold administrative roles). To win at Linfield is to do so fair and square. And to do it for six decades speaks to something much larger. "To think that the streak has been going three times as long as we've been born?" says Riddle. "That's absurd." For Carlson, the '98 alum, it comes down to the idea of family. "Once you're in our Linfield family, you're connected to 60 years of people who have had those core principles help shape their young lives," he writes in an email. "Those life experiences continue to breed an incredible amount of love and loyalty towards the program."

And now, on Saturday against Willamette, the streak comes up for its annual renewal. There's no point spread in D-III but Nelson estimates that if there were it would be "about 45 points."

So, sometime around 4 p.m., it will likely be over. Another win; another streak year in the bank. Afterwards, no doubt Riddle will jog over to pick up Mason. The Parker Moore jersey will be hoisted. And, on the sideline, Joseph Smith will begin searching for a teachable lesson in it all.