Tripp Gulledge marches on for the Auburn marching band despite a rare eye condition

There are 380 students in the Auburn University Marching Band, and on game day, they all appear identical. They wear the same uniforms. They line up in the same formations and they march in step and with the same posture.

Despite their apparent similarities, however, there is only one member of the band who is completely blind.

In 1996, Tripp Gulledge was born with retinopathy of prematurity, a disease in preemies that causes abnormal blood vessels to grow in the retina—the layer of nerve tissue in the eye that allows us to see. The growth of these vessels causes the retina to detach from the back of the eye, which in turn causes blindness.

Gulledge was only six weeks old when doctors diagnosed him with the disease, which initially seemed correctable.

"They decided to do laser surgery, which works kind of like welding," says Gulledge, now a freshman at Auburn. "The doctor took a laser and burned parts of my retina to the back of my eye so it would stay and be forced to grow back, and that prevented any further vision loss."

But when Gulledge was almost 14, his vision began to deteriorate.

"What I saw at 20 feet away is what you would see at 800 feet away," he says. "At the beginning of eighth grade, I went for one of my regular checkups and [my doctor] told me that my right retina was detaching again."

Gulledge was referred to Dr. Tim Murray, a world-renowned eye specialist in Miami who injected him with a medication designed to reduce the blood vessel growth. After eight months of regular visits, Murray tried a different approach. The procedure Murray used is called a vitrectomy; he placed a bubble of oil inside of Gulledge's eyes to force his retinas to reattach.

"After that surgery I had to lie, stand and sit face down for two weeks solid, which was kind of a low point," says Gulledge.

Although the vitrectomy was a success, the oil used in the procedure still prevents light from reaching the back of Gulledge's eyes. On a good day, he can perceive some light. But for the most part, his world remains dark.

"It sounds like a really big deal, but my vision was always pretty bad," says Gulledge. "I started out in preschool getting low vision services, learning how to read Braille, learning how to use a cane and learning how to do things by feel instead of by sight. So it didn't feel uncommon to me when I lost my sight to be reading with my fingers or tie my shoes because I never really relied on my eyesight."

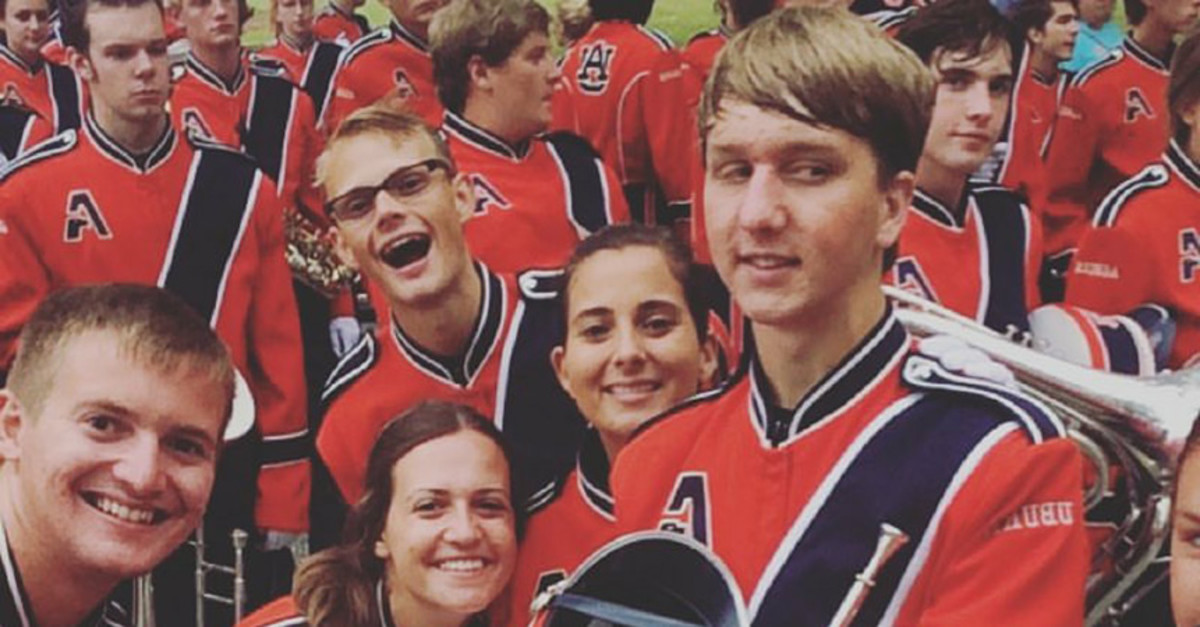

Courtesy of Tripp Gulledge

In the big picture, though, things were very different for Gulledge. But he didn't focus on that—especially around other children.

"I refused to just be like, I can't play because I can't see", he says.

As the oldest of three children, Gulledge aspired to be a symbol of strength for his younger siblings, Charlie and Lilly. And his parents—Rob and Angie—held him to that standard.

"[My parents] said, 'We're going to give this kid every opportunity that he has, as long as he's safe.' " Tripp says. "They completely ignore the fact that I can't see. They expect nothing but the best from me at all times."

Gulledge may have been limited by his vision, but a good musical ear helped him to level the playing field. He started playing piano when he was five. At first he preferred the violin, but he had a piano in his home.

And the instrument, with which he could make use of his sense of touch, turned out to be a good fit.

"I had already been reading Braille for about a year or two, so I had already developed a refined sense of touch," Gulledge says. "I applied it to playing the piano and I loved it."

The piano isn't considered a band instrument, so when Gulledge got to sixth grade, his band director tried him out for the French horn.

"There was usually a big grey spot on my nose from pencil ink because I had to hold the music so close to my face," he says.

Once Gulledge got to high school, his band director—Stan Chapman—started to unlock his potential. Chapman believed in the boy's ability as a musician. And because of that, Gulledge started to believe in himself.

In 2015, he participated in his first band camp as a college student.

"I met [Tripp] on one of the first days of camp," says Emily Ruggles, Gulledge's band section leader. "His personality is hysterical and I admire how he takes his disability and turns it into something light—he doesn't let it weigh him down.

"During band camp, we had to teach him how to march and teach him the essentials so he would be ready for Saturdays."

Armed with his mellophone, Gulledge performed in his first halftime show during the Tigers' home opener against Jacksonville State. That day, he marched with the Auburn University Marching Honor Band—a group that performs annually and is comprised of both high school and college students.

When Gulledge marches, he can see a little bit of light out of his right eye. This sets him off balance because he is naturally drawn toward the light. Because of this, it's important for him to remain focused while he's on the field.

"Once I got moving, I really spent most of my concentration on staying in step and keeping my orientation in line," says Gulledge. "There are 380 [band] members. Me losing my sound for a minute isn't going to cripple the band, but if one guy is a step off it sticks out like a sore thumb."

Gulledge's performance with the Honor Band went off without any disasters. After his first triumph, he was cleared to perform during halftime of Auburn's homecoming game against San Jose State.

That's when things got a little more complicated—Gulledge was guided through his movements by a fellow band member.

"The Honor Band show only required [Tripp] to march on the field and march off," Ruggles says. "During that performance, he would just stay in one place. But for the [San Jose State] show, we had to incorporate homecoming and the alumni band. We had to move around more on the field.

"It's not yet to the level of what we do on our regular Saturdays in terms of making shapes on the field, but he's still moving up in difficulty."

In his second performance, Gulledge had taken some of the biggest steps of his life. And 87,451 fans in Jordan-Hare Stadium were witness to it.

"It was really cool to see Tripp out there with the rest of us," Ruggles said. "It was cool to see him out there marching just like anyone else in the marching band. He doesn't have to just sit on the sidelines anymore."

Courtesy of Tripp Gulledge

Gulledge's performance was displayed on the largest scoreboard in college football. However, he wasn't looking for attention. He was looking to inspire.

"A man and his two children came to our rehearsal the Saturday before the [San Jose State] game," says Gulledge. "The gentleman's name was Brent, and his son was also totally blind. He came up to me and asked me to introduce myself to his son, Mason. Brent told me that he read my story to his son, and because of that, Mason now wants to do marching band when he gets older."

Gulledge's advice to kids around the country with disabilities: Stay strong, move forward and march on.

"Use encouragement from others as motivation to prove those who believe in you right," says Gulledge. "And for those who don't believe in you, use it as fuel to do what they say you can't so you can send messages like I have.

"Any time that I've ever been told that I can't do something, I've let that encourage me to do that thing. It's not about being the first person to do something, it's about making sure you're not the last. Now I know that Mason is going to grow up and make sure that I wasn't the only blind student ever to be in the marching band."

Whether or not Gulledge will ever perform in a full halftime show remains to be seen. But at this rate, it wouldn't be wise to bet against him.

"I can see Tripp marching in a real show sometime in the future," says Ruggles. "It's incredible to see how he's progressing."

Gulledge may not have his sight, but he has a vision—and its impact is being felt by all those around him.

C.J. Holmes is SI's campus correspondent for Auburn University. Follow him on Twitter.