Fred VanVleet is driven (and haunted) by his hometown’s history

This article originally appeared in the the Nov. 9, 2015, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

The Rockford, Ill., AAU team Fred VanVleet starred on during high school was called PrymeTyme—a defiant name, given that the city’s prime was so long past that none of the team’s players nor most of their parents had been alive to see it. Rockford is one of the Rust Belt’s worst casualties, a former manufacturing power 85 miles northwest of Chicago with a population of 150,000 and shrinking. In 1993 its school district was found guilty, in federal court, of decades of what a judge called “cruel” discrimination against minority students, ranging from inferior facilities to substandard curricula. The city was ordered to make $252 million in changes, but the current struggles of Rockford’s African-Americans are part of that ugly educational legacy: According to U.S. Census Bureau data from 2014, Rockford had the highest unemployment rate for black adults of any city in the nation, a staggering 28.9%.

Shoe companies have had no interest in sponsoring AAU teams from markets like Rockford, so for PrymeTyme to compete against the elite Nike and Adidas programs it had to fund-raise, collect dues and spend long hours driving (rather than flying) to tournaments. During those car rides coach Anthony (Doc) Cornell told stories about the closest Rockford had come to basketball greatness. And the one that VanVleet heard most—to him, the most Rockford story of them all—was about Lee Lampley.

“You shoulda seen this guy,” Cornell would say, conjuring images of gyms that drew fire-code-violation crowds to see the 6-foot Lampley ”shoot the leather off the ball.” There was the time in 1992 when Lampley had 32 points for Boylan Catholic in an upset of the No. 1-ranked Chicago King team that had a cameo in Hoop Dreams. Or the games during the 1993–94 season, when he averaged 29.9 points—more than a Mount Carmel phenom named Antoine Walker—and Lampley was named all-state, the last first-team selection from Rockford. Doc claimed that if Lampley hadn’t lacked the grades to accept a scholarship to Illinois, hadn’t been kicked off of two junior college teams, hadn’t been convicted of trying to sell 23 bags of crack in a Rockford housing project in ‘97 and enough other felonies to spend long stints behind bars—”People would be saying that Steph Curry is the best shooter not since Ray Allen, but since Lee Lampley.”

• MORE: See all of SI.com's preseason college basketball coverage

Old heads love telling stories about basketball coulda-beens—cautionary tales that veer into mythology. VanVleet, PrymeTyme’s 6-foot point guard who would go on to earn a 3.5 GPA at Auburn High, came to hate the Lampley story and others like it. He’d watch NBA games and see proof of one version of the American dream—black players who’d made it out of some miserable hometown—and it ate at him that none was ever from his hometown, which had gone decades without producing even a high-major, Division I black star. For the men who came before him in the same neighborhoods and the same schools, it seemed that all the dream did was die, again and again.

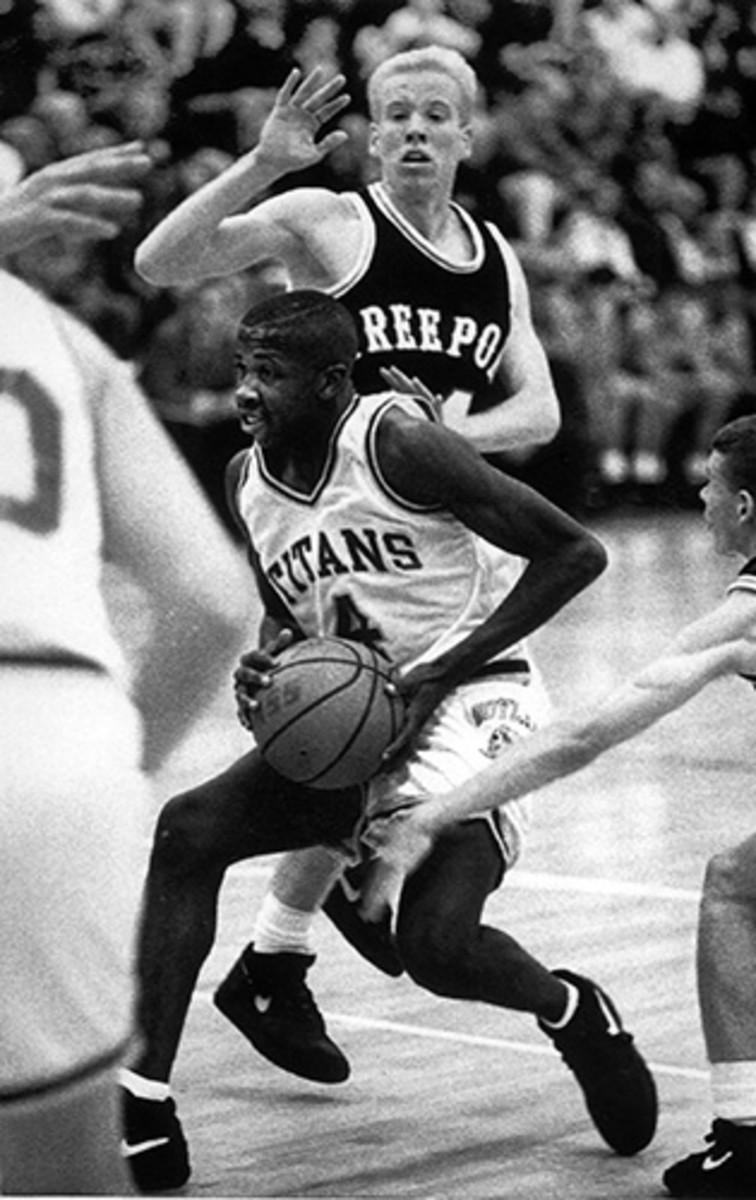

So when people began praising VanVleet’s play, it was as ominous as it was optimistic, so easily would he fit into another coulda-been lament. Illinois recruiting expert Cavan Walsh called VanVleet a magician who saw two steps ahead of everyone else on the floor. VanVleet was just a 15-year-old sophomore when his Auburn High coach, Bryan Ott, told the Rockford Register Star, “It seems like he almost always makes the right decisions at the right times.” Cornell said he felt like Tony Dungy, because he had a young Peyton Manning running his offense. There were also conquests that might, years down the road, seem like myths: How in the spring and summer of 2011, PrymeTyme, with just two D-I prospects (VanVleet and eventual St. Bonaventure star Marcus Posley), took down powerful AAU teams such as Indiana Elite (with IU-bound Yogi Ferrell) and the Houston Defenders (with Kentucky-bound Aaron and Andrew Harrison) and went 32–4. Or how in March 2012, VanVleet’s senior year, he led an Auburn team whose starting lineup topped out at 6 feet to the Illinois semifinals and was named first team all-state—the first Rockford player so honored since Lampley.

But VanVleet has since defied the traditional narrative: He has continued to achieve. When people talk in a decade or two about the greatest four-season run by a mid-major, the debate will likely center around Butler, from 2007–08 through ‘10–11, and Wichita State, from ‘12–13 through ‘15–16, but there will be no argument over who was at the center of the Shockers’ success—a point guard who made it out of Rockford and made everyone around him better.

Wichita State Shockers 2015–16 team preview

After being ignored by Big Ten schools due to his stature (and, he believes, his hometown’s rep), VanVleet committed to Wichita State in July 2011, and as a true freshman was the sixth man during its run to the ‘13 Final Four. As a sophomore starter, VanVleet became one of the best leaders in college basketball, piloting the Shockers to a national record 35–0 start before they fell to Kentucky in their second NCAA tournament game, and was named an honorable mention All-America. Last year he averaged 13.6 points and 5.2 assists while taking the Shockers to the Sweet 16, and this off-season both he and senior shooting guard Ron Baker passed on the NBA draft in order to make a fourth run at a national title.

In Wichita, where the Shockers have gone 95–15 during his career, VanVleet is the face of winning. He is sitting in a back-corner booth of a minimall deli during an October lunch hour, getting deep into a discussion of his Rockford youth, when he is interrupted by a woman, smartphone in hand, teenage members of the girls’ tennis team from nearby Andover High timidly in tow.

“I’m so sorry,” the woman says, “It’s just that tomorrow we have states, and we’ve won back-to-back titles and we’re going for a three-peat. So I thought, Who better to take a picture with than you for inspiration?”

VanVleet is happy to oblige. Everyone smiles.

“Any tips for the girls?” the woman asks. VanVleet pauses, and then sheepishly says, “Just play hard—and have fun.”

It’s not that VanVleet lacks an answer on what drives him to win. It’s just that his answer isn’t translatable for a group of suburban high school girls. “My whole mind-set growing up,” VanVleet says later, “was that I was not going to let myself be one of those Rockford people who didn’t pan out. And I carried that chip with me to college—that I need to be that one who actually breaks the stigma. Their failure is in the back of my head. That is what I’m running from.”

*****

The closer a story hits home, the more likely it is to gain unwanted purchase in your brain, to linger there and haunt you. Lampley’s narrative did not begin in a packed gym in the ‘90s. It began on the front page of the Register Star, three days before Valentine’s Day, in 1982. A man was found lying in a snowbank in an employee parking lot of SwedishAmerican Hospital, steps from his ‘76 Cadillac Brougham, dead of multiple shots from a large-caliber handgun. He was a surgical orderly, and in the late ‘60s he had served in the Army. He was 34, and among those he left behind was the six-year-old boy named after him: Lee A. Lampley Jr. When Lee Jr. was arrested for selling crack 15 years later, locals said they’d seen his downfall coming. Despite his prodigious talent, he lacked the family structure to save him from Rockford’s crime-infested streets.

On April 16, 1999, the Register Star carried another story of a black man shot and killed. He’d taken two bullets to the chest, at close range, in another man’s apartment. The shooter claimed it was a break-in, but he was later charged with felony obstruction of justice for attempting to deceive police. The dead man was 28. In his prime, he’d been a hyper-competitive 6'8" forward at Rockford’s Guilford High who drew interest from colleges. He never enrolled anywhere, and found work detailing cars. People called him Boomer or Darnell, his middle name. His real name was Fredderick Manning. Among those he left behind was a fiancée, Susan VanVleet, with whom he’d had two sons, seven-year-old Darnell, and five-year-old Fredderick, his namesake.

Susan summoned her boys to a couch in the basement of her parents’ house just north of Rockford in Machesney Park, where they were all living, and explained that their father was gone. Fred was too young to process what had happened. He has no recollection of seeing his father’s body at the funeral. Susan told him parts of the story as he aged, and eventually he learned that his father had been killed in a drug deal gone wrong. Fred has always been serious; but it was losing his father, Susan says, that turned Fred into “a kid who was angry at the world.”

“I felt like I’d been burned or that everybody owed me something,” VanVleet says. He struggled with whom to blame; sometimes he blamed himself. “You ask yourself a million questions. Why was my dad not home with me that night? What did me or my brother or my mom do wrong? What did my grandparents do wrong, what did my dad do wrong? You’re just trying to find an answer.”

In sixth grade he was the point guard on a Chicagoland club team that went to the AAU nationals in Hampton, Va.—a very big deal. But when he called home to Susan during the tournament, he sounded, as he so often did, unhappy. She had tried many ways to cheer him up. This time she challenged him: “Have you ever stopped and told God thank you for everything that he’s made up for in your life?”

She told Fred to consider that he was athletically gifted, intelligent on the court and in school—and by then he had a new father figure. “Things are coming easy to you,” she said, “and it’s almost like God was trying to give back to you what was taken away. If you acknowledged that sometime, it might get easier.”

College hoops Crystal Ball: Picking Final Four, player of the year, more

Fred said O.K. They did not discuss it further. But when the team returned to Illinois, its coach, Brian Harvey, told Susan, “You’re never gonna believe what happened. We weren’t playing very well, and halfway through the tournament I was really yelling at the kids, and I give them a break and time to just chill out. I wanted them to think about what they were doing. The next thing I know Fred is asking them to all come in and say a prayer. What 12-year-old kid does that?”

Fred says he had a realization on that trip: The answer to all his questions about his dad, the questions that still made him angry, might be that there was no answer. That what you had to do, instead, was try to appreciate the present. Only then would things start to get easier.

*****

Rockford Police detectives on the day shift can get by with two-piece suits, but Joe Danforth insists on always wearing a three-piece. “I just love that whole Untouchables look,” he says, and on this October Tuesday he’s wearing a charcoal ensemble over a cardinal-red dress shirt and a black silk tie, with his badge and a holstered Glock on his right hip. He is a bull of a man, with his head shaved slick, a former Army boxing-team middleweight and light heavyweight who fought for the Fort Hood (Texas) Worldbeaters in the ‘90s. The ringtone on his phone is rapper Bone Crusher’s 2003 hit “Never Scared,” and Danforth carries himself with a jovial swagger suggesting just that—even though Rockford’s violent crime rate is the second-highest in the nation for cities under 200,000.

This past summer, in Danforth’s 20th year on the force, he was promoted to detective, and the first case he caught was the murder of 15-year-old Martavius Lewers. It was the 15th homicide in Rockford in 2015: a gunshot through a window of a residential music studio on the city’s west side caught Martavius in the head while he was recording with friends. It remains unclear whether he was the target.

Danforth has worked 30-plus cases since—home invasions, armed robberies and more, a leaning tower of manila accordion folders on his desk—but the senselessness of the unsolved Lewers case wears on him. Danforth has coached basketball, running an AAU program called Rockford 5-0 because, he says, “you can’t let this job be your whole life.” The left wall of his cubicle is decorated with three autographed pictures of teenagers playing hoops for the same school that Lewers attended, Auburn High: Danforth’s oldest son, J.D., who’s now 23; and his stepsons, Darnell and Fred VanVleet.

College basketball preview: Best teams outside the big conferences

Danforth was one of the policemen who responded to the scene of Manning’s shooting in 1999. It was not until two years later that he encountered the VanVleets. J.D. and Fred—then a second-grader—were in the Fightin’ Titan Boys Basketball Camp at Boylan High, where Lampley had played. Susan VanVleet and Danforth met in the gym that day; they started dating within a few months. Two years later Susan and her two boys joined Danforth and his two boys in their house on the northwest side.

“We kind of did a Brady Bunch thing,” Danforth says, and it was not the smoothest transition. Says Susan, “Joe was ... very militant with the boys.” What did Fred think? “He was a d---. He had everybody walking on eggshells.” It was the opposite of the warm, lax environment at Susan’s parents’ house. Now there were bed checks, reprimands over a single unwashed dish and wake-up calls at 5:45 a.m. for intense workouts that included full-court one-on-one in weighted vests. The worst thing, VanVleet says, was when he had to get dropped off by Danforth at school: “Kids used to wear shirts with a stop sign that said snitching on it—like, stop snitching—and here I am pulling up to school in a cop car.”

But for all of VanVleet’s resistance—he hated the extreme discipline and early workouts, and resented the fact that Danforth chose to coach J.D. in AAU and left Fred to play with PrymeTyme—a funny thing happened: He started to acquire Danforth’s mannerisms, obsession with detail and military mentality, to the extent that Doc Cornell would say to Danforth, “I swear that’s your damn kid.”

Now, does Danforth deserve credit for VanVleet’s court vision, Floyd Mayweather–quick hands and the unshakable confidence to overrule a final-possession pick-and-roll play that Cornell called in a 2011 AAU game, say, “I got this” and proceed to bury a game-winning three? Not at all. “This ain’t The Wizard of Oz,” Danforth says. “You can’t just give the Cowardly Lion a heart and expect that mother------ to fight, you know? That’s gotta be in you, and that was in Fred.”

But VanVleet did need sharpening. “A lot of things [Danforth] did for me hardened my mind,” VanVleet says. “He gave me a mind-set that was calculated but aggressive, with no fear or regrets, like a war general.”

That would be key to thriving under the Shockers’ intense and exacting coach, Gregg Marshall, whose motto is Play angry. VanVleet began his freshman season buried at the back end of the rotation, gradually earned more minutes during Missouri Valley Conference play and then had his career kick-started in a peculiar way: After a loss to Creighton in the Shockers’ last game before the NCAA tournament, Malcolm Armstead, the team’s senior starting point guard, approached Marshall’s wife, Lynn, son, Kellen, and daughter, Maggie, with a request. “Tell coach that Fred’s gotta play,” Kellen (now a student manager for Wichita State) recalls Armstead saying, while expressing a desire to play alongside VanVleet at the two. “It’s my senior year, and I’m trying to go to the Final Four.”

The message was delivered, and Marshall put VanVleet on the floor for 20 minutes in the ninth-seeded Shockers’ second-round meeting with No. 1 Gonzaga. With 1:28 left and the shot clock running down, VanVleet rewarded his coach by hitting the dagger three that put Wichita up five and out of the Zags’ reach. In 24 minutes against Ohio State in the Elite Eight, VanVleet outplayed the celebrated Aaron Craft, and through all 2013 postseason games, VanVleet dished out 14 assists against just six turnovers.

That year’s Final Four, in Atlanta, was where the Shockers blew a late lead against eventual champion Louisville, but it was also where a protracted standoff between two hardheaded men came to an end.

Danforth had never been one to compliment VanVleet, only drive him; VanVleet, in turn, had never been one to acknowledge Danforth’s contributions. The day before the Louisville game Danforth, who’d driven to Atlanta and gotten caught up in the magnitude of the event, allowed himself a moment of vulnerability. He texted VanVleet to say, “I love you. I’m proud of you.”

VanVleet had never called Danforth ”Dad,” but he wrote back, “If you never felt like you were my dad, I want you to know, I do feel like you’re my dad. You raised me, and I appreciate everything you’ve done for me.”

*****

VanVleet returned to Wichita State and became its clear-cut leader. It was not a coincidence that the Shockers broke 1990–91 UNLV’s record for most consecutive wins to start a season, and they entered the NCAA tournament 34–0 and ranked No. 2 in the nation. VanVleet was a 20-year-old sophomore in a rotation that included four seniors, but everyone considered him an old soul. He ran the offense with efficiency—in one four-game stretch in December and January he had 23 assists and no turnovers, and his assist-to-turnover ratio in March was 36-to-8—sat front row center during film sessions and was the team’s most trusted voice in huddles and in the locker room. “Fred always has the right thing to say at the right time,” Baker says. “I don’t know where he gets it from, but it’s like music to your ears. It’s always nice to hear his voice when we win—and when we lose.”

After the most devastating loss of their careers—their epic battle with No. 8–seeded Kentucky in the NCAA tournament’s round of 32, which came down to the final possession and left them five wins short of the first perfect season since Indiana in ‘75–76—heads turned to VanVleet for wisdom. First he helped coax an inconsolable senior, Chadrack Lufile, out of their locker room bathroom at St. Louis’s Scottrade Center, so that they could face the loss as a group (“You win together, you lose together”), and then VanVleet reminded his teammates of their legacy. “This don’t take away from nothing we’ve been doing all year,” VanVleet told the room. “Everybody’s got futures in this.... This is not ending.” When Baker was moping on the bus outside the arena, VanVleet heaped positives on him: Neither of them had arrived at Wichita as NBA prospects, and they had just gone toe-to-toe with a team that had five future draftees. VanVleet knew that he and Baker would be together in more NCAA tournaments, and he wanted to build his teammate back up.

He did all this even though he was the one who missed the potential game-winning three, from the top of the key, as time expired. That goes in, Wichita keeps winning, and who knows? He might have been able to ride that fame to the draft, where he was viewed as a fringe first-round prospect. There was also the strong possibility that VanVleet had played most of the second half in a partial fog. After committing an offensive foul on a drive with 16:32 left in the game, he hit his head on the floor and was nearly knocked out; he remained a bit off following the collision.

Ranking every team in college hoops from Grambling St. (351) to UNC (1)

VanVleet spent the postgame press conference wincing at the lights and feeling his head throb, and for the first time in his life a teammate, Cleanthony Early, asked him about part of a play that he could not clearly remember. After the press conference, when the team’s trainer gave VanVleet a concussion test, he declined to acknowledge any symptoms. He felt there was minimal risk; the season was over. “I didn’t want that to be the story line: He didn’t play as well as he could have, he missed the shot, oh—he had a concussion,” VanVleet says. “I think I had a concussion; I just didn’t want to tell anybody.”

For better or worse VanVleet believes that showing weakness limits his ability to inspire teammates—and that being a leader “means that I could get everybody on my team to come fight with me.” He means this literally: “Some guys would take a lot more work than others, but if I got in a fight, I know that I could convince everyone to have my back. If you can get them to do that, then you can get them to chase a rebound or believe in themselves to make a shot.”

Or persuade them that they can come back in 2014–15, win 30 more games, and beat Kansas to go to the Sweet 16; or that this season they can leverage the advantages of having the most seasoned lineup of any elite team. Wichita State is likely to start four seniors—forwards Anton Grady and Evan Wessel, and guards Baker and VanVleet—and no coach has more trust in his point guard’s grasp of an offense and knowledge of personnel than Marshall. “With Fred, it’s like having a head coach on the floor,” Marshall says. “He’s got the ability and the freedom from me to audible-ize anytime he wants.”

The Shockers’ veterans have the freedom to self-police, running a kangaroo court in their locker room at Charles Koch Arena. If someone is charged with violating the team’s unwritten code—such as in September, when a freshman was alleged to have flirted with a teammate’s female friend, and possibly to have impugned that teammate’s character in the process—he is hauled before the court. The primary judge, from the vantage of his corner locker, is VanVleet. And these are the rarer occasions when VanVleet is not overly serious. “It’s as good as an SNL skit,” says one observer. “Freshmen pleading to Fred, him shaking his head, saying, ‘Oh, no, I can’t allow that.’“

“I give people a chance to present their case,” VanVleet explains, with a smirk. “Then we bring out the evidence and convict them. Because most of the time it’s just a guy who’s wrong, who won’t admit he’s wrong. And we take care of it ourselves.”

*****

For the Danforths and VanVleets, 2015 has been a year of coming together. In May, after 11 years of cohabitation—and having a daughter, Aaliyah—Joe and Susan were married at a Rockford church. In June, Darnell, who had played briefly at Illinois Central College and also coached Auburn High’s freshman team, moved to Wichita to be with Fred for his senior season; J.D., whose playing career ended at NAIA Ashford University in Clinton, Iowa, last year, joined them for three months. Shontai Neal, VanVleet’s girlfriend since high school and a fellow WSU student, lives with VanVleet and Darnell in a split-level duplex four miles east of campus. The living room’s decorations include a Shockers flag, a bench chair from the 2013 Final Four and the ‘14 Larry Bird Trophy, which VanVleet received as the conference player of the year.

Growing up, VanVleet used to help his older brothers with their homework, and at 21 he persuaded them to come to Wichita. “Darnell especially, I wanted him to get out and see other things, like what a millionaire’s house looks like,” says VanVleet, whose coach, Marshall, has a new contract that pays $3 million annually. “There’s no opportunity in Rockford, so if you stay there, you don’t see the world as very big.” (Darnell, when asked if he misses being back home, says, “No, I don’t miss it one bit.”)

VanVleet, a sociology major, recently tweeted a study from 247WallSt.com that called Rockford the second-worst city for black Americans, behind only Milwaukee. It highlighted Rockford’s alarming black unemployment rate and the huge gap between the median household income of whites ($51,264) and blacks ($22,651) in the metro area. The data reinforced what he believed growing up as a black-identifying child of a biracial family—”Everybody knows,” he says, “that Rockford is racist”—and reminded him that his city has a long way to go in addressing inequality. VanVleet’s hope is that when he’s made enough money playing basketball, and has some financial leverage, he can help fix a west side school system whose curriculum, he believes, fails to emphasize practical learning, does not teach enough black history and promotes inept students until they’re old enough to drop out.

• MORE: Wichita State a No. 2 seed in our NCAA first bracket projection

As the graduation speaker for Auburn High’s class of 2014, VanVleet told the crowd at BMO Harris Bank Center, “They’re always telling us, ‘Rockford is a miserable place to live. There’s not a lot of talent coming out of Rockford.’ Blah, blah, blah. You know the rest of the story. I look at it like there’s only two things you can do about it. You can live up to it and make it worse or you can change it and make it better.”

It was during that same off-season that VanVleet went to play pickup in the small gym at Northwest Community Center, where Doc Cornell had invited some of Rockford’s old heads and young prospects. One of them was a 39-year-old who did not, at first glance, look the part of a baller. He wore a do-rag and jean shorts, and his right arm was permanently bent, the result of some childhood injury. But he could get that arm into shooting position just fine, and as VanVleet saw it, “The guy’s jumper was perfect—wet, all the way to half-court.” The guy was Lee Lampley.

Lampley had been released from the Danville (Ill.) Correctional Center in February 2014, after serving four years for possession of between 100 and 400 grams of cocaine. He had heard about VanVleet, seen him on TV since getting out of jail, and wanted to talk to him.

VanVleet ended up giving Lampley a ride home, during which he said a couple of things: I hope you learn from my mistakes. And: I knew your real dad. Lampley had been in the same drug game as Manning and said he could find some answers. VanVleet was returning to Wichita the next day, so they exchanged numbers. “I’m going to call you when you get back to school,” Lampley told him, “and I’m gonna let you know what really happened.”

The call never came. But really, VanVleet had stopped needing answers long ago. He was O.K. with how he and Lampley had parted ways. The last thing VanVleet had said, upon dropping off the greatest player who never made it out of Rockford, a man 19 years his elder, was stay out of trouble.