New film 'My All-American' beautifully captures legacy of former Texas Longhorns star Freddie Steinmark

Incoming football players at the University of Texas quickly learn two things: the school's fight song and the story of Freddie Steinmark. Steinmark was a standout safety on the 1969 national title team, but he entered Longhorn lore days after his final game, when doctors discovered he had played the whole year with a large tumor in his left leg. He died of bone cancer 18 months later, and the Steinmark Legend was born.

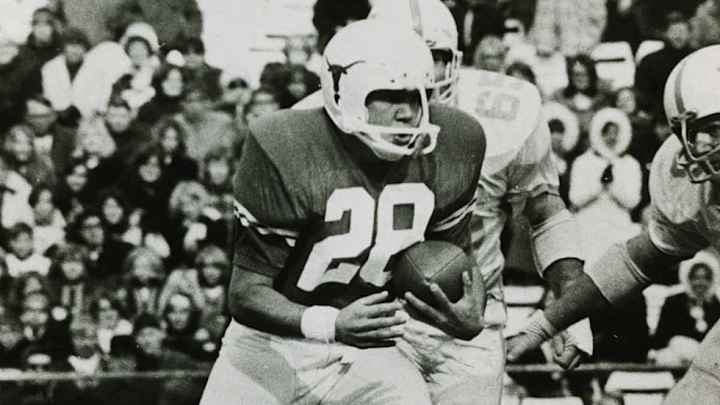

More than four decades have passed, but players still touch a photo of Steinmark on their way out of the tunnel before every home game, and this season the Longhorns have worn "FS" decals on their helmets. Before last Saturday's 59—20 win over Kansas, the team donned throwback jerseys in honor of Steinmark, and the scoreboard was rededicated in his name. Senior corner Duke Thomas, who wore Steinmark's No. 28, said players try to honor Freddie every time they step on the field.

Yet, if you don't bleed burnt orange and yell "Hook 'em" as a salutation, the name Freddie Steinmark likely means nothing to you. Filmmaker Angelo Pizzo is trying to change that. The writer of Hoosiers and Rudy wrote and directed My All American, a film which tells Steinmark's story and opens in theaters across the nation on Friday.

That story did not end with Steinmark's football career. After cancer cut his playing days short, Steinmark became an early face of cancer's indiscriminate devastation. President Richard Nixon invited Steinmark to the White House to applaud him "for providing inspiration and hope to thousands of Americans whose lives have been touched by cancer." Countless branches of the American Cancer Society held fundraisers in Steinmark's honor and his autobiography, I Play to Win, became required reading among activists.

After Steinmark died, sportscaster Howard Cosell proclaimed: "There's got to be sadness in this country today over the loss of such a great young man." In the Capitol, Texas senator Lloyd Bentsen said, "Let us make the passing of this fine young man a signal for action in this body, to move as expeditiously as possible to achieve a cure."

Freddie's mother, Gloria, joined that campaign, telling the President he should "fight cancer like he would fight any other war" when an aide asked her if there was anything the White House could do to honor her son. Six months later, the aide called Gloria to tell her that Nixon was signing the National Cancer Act of 1971 into law. She was going to get her war.

Since then, the Steinmark family has gone quiet, as Pizzo realized while researching his script. That's why you have not heard Freddie's name. Protective of his legacy, the Steinmark family had refused to cooperate with eight previous attempts to tell Freddie's story. Pizzo and Texas alum Bud Brigham, an oil entrepreneur and My All American's executive producer, were able to convince Gloria that it was time to share the tale. They contended that Freddie's struggle could provide a needed role model and reinvigorate interest in finding a cure for cancer. They also promised to stick to the facts of his life, though Pizzo knew that would make his job tougher, because Steinmark had been near perfect, and the writer was still searching for conflict for his script.

Gloria agreed to cooperate, but she opted not to attend any of the filming and likely will not see the movie. The pain of losing a son is still too much for her. In her place, Freddie's brother, Sammy, acted as a liaison for the family, and one of his first tasks was speaking with Finn Wittrock, the actor tabbed to portray Freddie. The two talked for hours, Wittrock studying Sammy's accent and tone, Sammy scrutinizing the man chosen to reanimate his brother. He ended up having no reason to worry.

Wittrock bulked up for the part in Los Angeles before attending a two-week, football-intensive boot camp in Texas. "That was the sorest I'd ever been in my life," Wittrock said. "I was barely able to walk after the first practice."

Later, Sammy would tell Wittrock that he felt the two had been brought together in life for a reason. "I'm so proud you played my brother," he said. Wittrock responded with a hug. The other big hit on set was Justin Street, who played his dad, James, the quarterback of the 1969 team. Justin's ability to mimic his dad's mannerisms and tone stunned the members of the '69 team there as consultants, and Justin thanked God each day for the chance to get to know his father in a new way months after James died of a heart attack.

With movie about to be released, the Steinmark family is hoping to share Freddie's story with as many people as possible. "If somebody could have a piece of Freddie in their life, it would be better," Sammy said. "There's no doubt in my mind."

Texas coach Charlie Strong, who called Steinmark's life "an unbelievable story of pride and courage," has already pledged to show the film to every incoming recruiting class, and as the nationwide search for a cancer cure nears 50 years old, Steinmark's name will be a topic of discussion in D.C. once again when congressmen attend a special screening of the movie next week.

"Obviously it brings things full circle; Freddie went to the White House and helped start the War on Cancer and now he's back," said Bower Yousse, who wrote a biography of Steinmark's life, Freddie Steinmark: Faith, Family, Football. "It's amazing, when you think about it, that Freddie has been gone for 44 years and still has this kind of impact."