Frank Beamer says goodbye: Virginia Tech's coach looks back on his legendary career before his final game

BLACKSBURG, Va.—The last two syllables were too much. Frank Beamer couldn't squeeze them out, not that afternoon.

"I think it's time for me to …" the longtime football coach's voice choked. The hallway was empty but for him and his son, Shane. And Shane knew. His father didn't need to say it. Retire. It was there, in his eyes, in the tears he fought back. The end.

On Friday, Oct. 30, Beamer's mind was made up. In his 29th season at Virginia Tech, the 69-year-old coach had pondered stepping away from football since the summer, and Shane was hardly clueless to the fact that this moment loomed. Until then, though, it had been an abstract idea. Dad's tired. Dad doesn't have the energy he used to. But he is still coaching, still doing it like he has for decades. There was a certain perpetuity to it all, because 29 years is a football eternity. And then, in that hallway, in those two unsaid syllables, the end of an era.

As Beamer explained his decision—at that point, only his wife, Cheryl, and longtime confidant John Ballein knew the coach's plan to retire at the end of the season—he told Shane he would tell his players and staff after the team's game at Boston College that weekend. Shane suggested he wait. Frank insisted. He wanted to give the Virginia Tech athletic department plenty of time to search for a successor, so the announcement would come on Sunday. Until then, Shane was instructed to keep quiet. "We fly to Boston, and we beat Boston College, and it's kind of bittersweet," the younger Beamer recalls.

For the team, it was the fourth win of the 2015 season. For the four people who knew what would come next, it was the last day of the world as they knew it.

*****

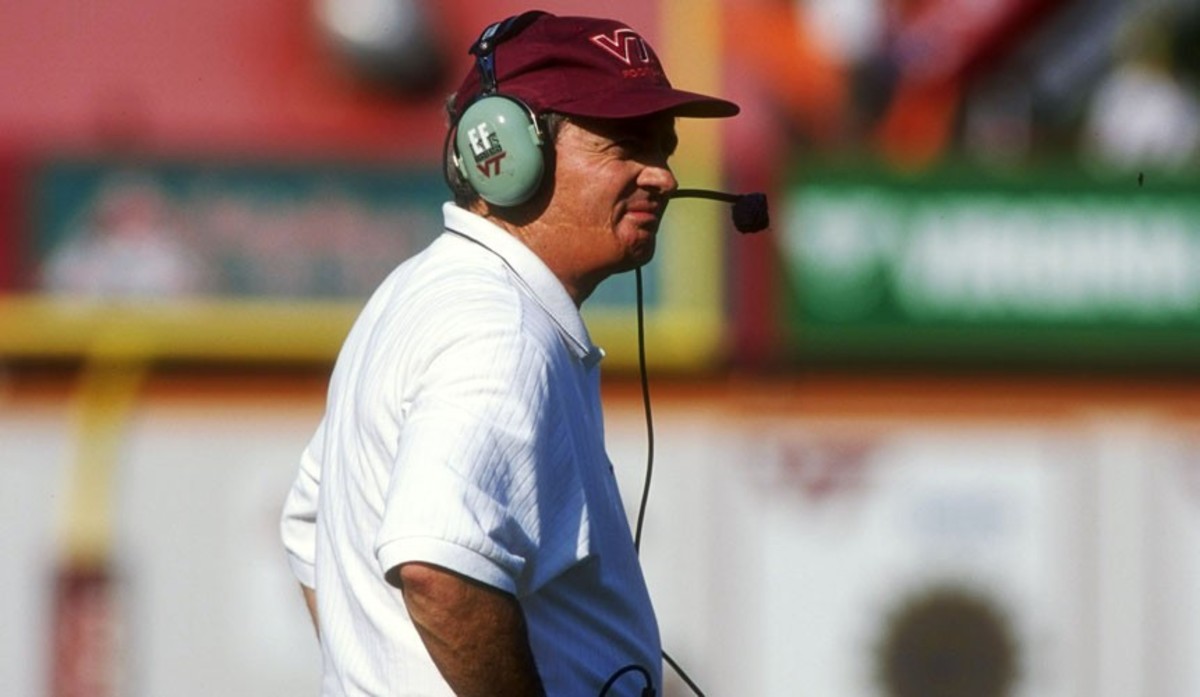

Erik Perel/Getty Images

On Dec. 22, 1986, Virginia Tech announced its new football coach, a 40-year-old who had spent the past eight seasons at Murray State. The program Frank Beamer inherited that day was only regionally relevant, coming off the most successful stretch in school history under former coach Bill Dooley. In 1986 it had gone 10–1–1, but Dooley was forced to resign in the face of numerous NCAA violations. Virginia Tech was in debt, and Beamer, a Hokies cornerback from 1966-68, was at best a bright young hire, at worst a cheap solution. (His first contract paid him $80,000 annually.) Nearly 30 years later, the coach can still recall a column analyzing his hiring in the Roanoke Times. In keeping with the Christmas spirit, it compared him to an underwhelming gift, saying that Virginia Tech had gone to bed expecting a bike and instead been given a sweater. "My response," Beamer says, "was maybe Virginia Tech needed a sweater."

Ballein, who was a Hokies graduate assistant in 1987 and is now a senior associate AD at Virginia Tech, recalls a recruiting breakfast during Beamer's first year in Blacksburg. It was held at a now-defunct hotel, and the young coach's message seemed wildly optimistic. "We're going to build this program, and one day we're going to play in the Orange Bowl, and one day we're going to play in the Sugar Bowl, and one day we're going to play for a national championship," Ballein remembers Beamer telling the assembled group. "I'm sitting there," Ballein says, "just totally new to it, and I'm just not so sure about this."

In the fall of 1987, the NCAA leveled its sanctions on the program. After exceeding its scholarship limit under Dooley, Virginia Tech would lose 20 scholarships over two seasons. For Beamer and his staff, that could have been a crippling blow, and it translated to early struggles. In '87, the Hokies went 2–9. In '88, they went 3–8. They saw their first winning season under Beamer in '89, going 6–4–1, but hovered around .500 until '92, when the team took a 2–8–1 dip. In his first six seasons, Beamer failed to make even one bowl game. In the modern era, he would have been fired, certainly by year six, if not earlier. But Virginia Tech remained committed to its coach, and in '93 the promise Beamer made at that breakfast began to take shape.

The Hokies went 9–3 that season, winning the Independence Bowl. They haven't missed a bowl berth since, and two years later they defeated Texas 28–10 in the Sugar Bowl. That was the Hokies' coming out party, and they remained at the top of the sport for much of the next two decades, playing in the BCS title game in 1999 behind quarterback Michael Vick and making the Sugar or Orange Bowl at least once every five years since that first trip in '95.

From 1993-2011, Virginia Tech boasted a .761 winning percentage, but that's only half of the Frank Beamer story. Over his years in Blacksburg, the coach turned his school into a powerhouse, amassing a 237–121–2 career record while refusing to turn away from his values of hard work, discipline and decency. His devotion to players and staff resulted in a level of consistency almost unheard of at this level—and one of the game's greatest reputations. Over his 29 years, Beamer has seen 25 sets of brothers on his rosters, and his 2015 team boasts five players whose fathers also suited up for him. Tucked away in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Blacksburg became a kind of college football Camelot, the coach a drawling, chuckling King Arthur.

Beamer will man the sidelines for his final game on Saturday, in the Independence Bowl against Tulsa. He is still planning, still coaching his beloved special teams, but those around him have already begun to reflect on his legacy. After hearing of his coach's decision, Hokies redshirt junior defensive end Ken Ekanem recalls thinking, "I can tell my grandchildren about this." Longtime defensive coordinator Bud Foster, who has been with his boss since 1979 and is one of four members of Beamer's staff who have signed on to remain under new coach Justin Fuente, says these last days are bittersweet. They're more of an ending than they should be for a man who is keeping his job.

"We were at the pinnacle, and we did it for years," Foster says. He pauses, nods, takes a deep breath. "And I did it with the best guy in the business."

*****

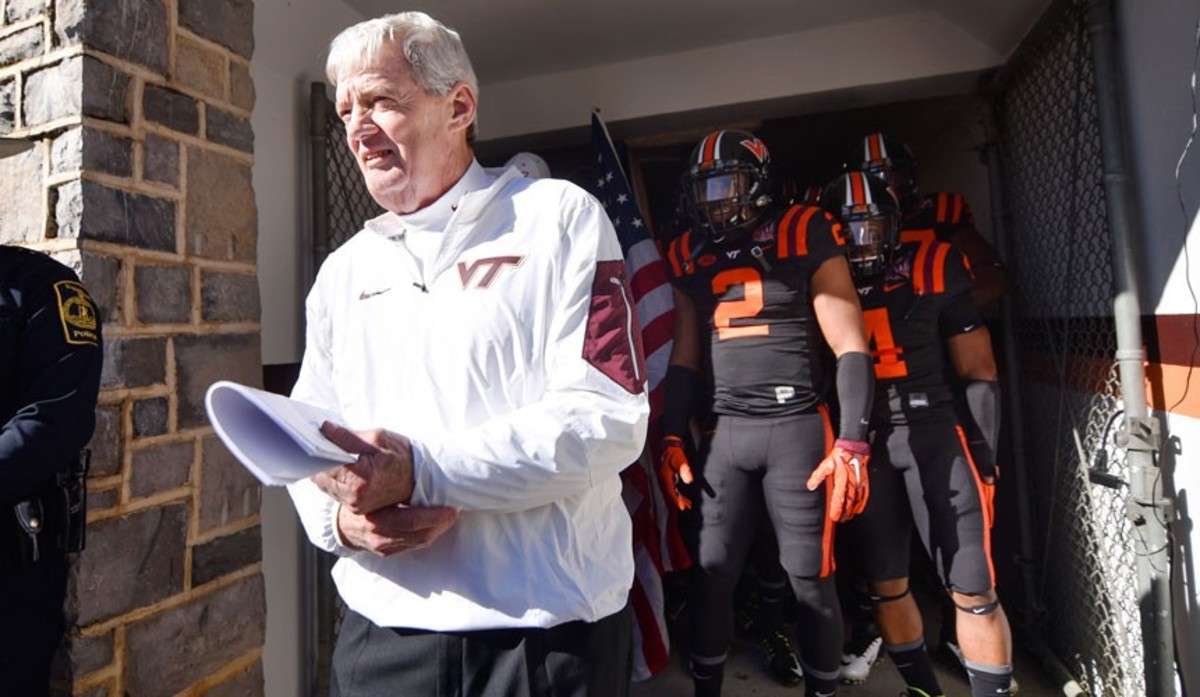

Michael Shroyer/Getty Images

A week before his final coaching job, Beamer sits in his office, his day a marathon of media engagements. The spacious room overlooking Lane Stadium is scattered with memorabilia: signed footballs, banners, posters, jerseys. Beamer has not begun to pack, and the trappings of three decades remain undisturbed. The "IT IS WHAT IT IS" sign still hangs from his bookshelf, the large model ship still sits on display by the window. The coach still boasts about his elementary school band trophy, tarnished silver and shaped like a harp, which rests on a table near the back entrance to the room. But even if the office shows few signs of transition, Beamer has been forced into an almost rote reflectiveness. On radio interview after radio interview, he talks about the pride he feels at what he built. With each conversation, he scribbles the interviewer's name in Sharpie on a legal pad in front of him, because Beamer is a man who will call you by your name. It isn't, "Thanks." It's, "Thanks, Dino."

Reliving all these memories, Beamer begins to synthesize. Going over his life so frequently and repetitively has helped him cull themes. Well, one theme, really: luck. It's not an awe, shucks, I don't deserve this brand, though. Beamer's luck is appreciative, a quiet awe of life's twists and turns that landed him here. "I can't tell you the number of times ... that [something] didn't work out, and all the sudden, I did something else that turned out better," he says. "And you go back and say, well, if that had worked out, you wouldn't be here."

Case in point: His first post-college job. Once his playing career at Virginia Tech wrapped up, the Hillsville, Va., (a town of 2,700 about 45 minutes south of Blacksburg) native took a position as an assistant coach at Radford High, 25 minutes southwest of his alma mater. It was a good job, and after his first year on staff the school's head coach moved into an administrative role. Beamer wanted the job. He didn't get it. Instead, Radford went with Norm Lineburg, who is now a Hall of Fame high school coach in the state. "If I'd have gotten that job, I don't think I'd have ever left high school coaching," Beamer muses. "Instead of being the head coach at Virginia Tech for 29 years, I'd have been doing that." He pauses, laughs. "Which is fine."

"Things happen for a reason, and sometimes when you think they're not right, keep plugging, keep working, and they'll turn out right," he adds. "Sometimes we don't know. What you think is best is not what's best."

The coach's philosophizing comes to an abrupt end. He has lost track of the time, and he told a friend he would pick him up so they could carpool to Charlotte for another friend's retirement party. He is running late but remains unfazed. He's excited for the party, thrilled to reminisce a career other than his own for a few hours. After all, his life has become a weeks-long celebration, with more photos, autographs and speeches than he could have ever imagined. It sounds exhausting, being Frank Beamer these days, but still, he signs and he smiles. It seems like yesterday to him that no one wanted a picture, and at 69, this game, this life, still holds a glimmer of novelty.

*****

Michael Shroyer/Getty Images

The display window at High Peak Sportswear in Blacksburg advertises the store's bestselling T-shirt, a maroon design with orange lettering. Its text is simple: "Thank you Frank." In the three weeks between Beamer's announcement and his final home game on Nov. 21, the tiny store sold upwards of 1,000.

High Peak was the fastest store in town to mobilize after word leaked of Beamer's impending retirement. Upon hearing the news, one of the store's employees, Travis Bishop, ran the idea for a shirt past High Peak's owners, and once they agreed, he called the store's production department in Lynchburg, Va., and told them to "find every maroon T-shirt you can and start printing." The printers only tracked down 80 in the right color that first day, but they got to work, and by Tuesday, less than 48 hours after the announcement, the first batch had sold out. Once High Peak restocked, fans were buying a dozen shirts at a time, calling in from as far away as Atlanta to place mail orders. It was hardly surprising, this clamor for a souvenir, and it helped that the message was so perfect. "Congratulations, Frank" would have worked. "Great job, Frank," or "We'll miss you, Frank." Any would have sold. But if there's one sentiment Virginia Tech owes Beamer, above all else, it is thanks.

"Everywhere you look, there's something he [built]," Ballein says. The stadium, the athletics buildings—all were constructed or renovated as a result of Beamer's success. Even the Highway 460 bypass, the best route to Lane Stadium, is a product of the coach's work. Built in 2002, the road eased game-day traffic, which has surged with the school's success, as has the area's tourism industry. A study commissioned by Virginia Tech before this season estimated that the football program pumps $69 million into the region's annual economy, in addition to 300 full-time jobs. For a man who has lived within an hour of Blacksburg for all but 15 of his 69 years—he was born in Mount Airy, N.C., and grew up in Fancy Gap, Va., before later moving to Hillsville—that means even more. The geography adds to the fairy tale, to the sense that nothing in the world makes more sense than the marriage of Beamer and Virginia Tech.

That proximity and connection made it all the more difficult this fall for the coach to feel like his continued employment had left a fan base divided. These are his people, and he didn't want them to argue or worry, but he knew they had cause. After eight consecutive double-digit-win seasons, the team slipped to 7–6 in 2012. It followed that with an 8–5 campaign in '13, then another 7–6 finish in '14. It was still winning, but not like it expected to be. Beamer concedes this. "We've been average here a little bit too long, and average when I came was good enough," he says. "But now average is not really good enough. And that's the way it should be. You have a break-even type team … and every loss is devastating, and every win, you don't enjoy. You get ready for the next one. … After a while, it wears on you."

And it did wear on Beamer, slowly at first, and so gently he didn't notice. But then, after a busy off-season, the coach found himself lagging during the team's camp last summer. He woke up one morning and asked himself why he was still coaching. At the time, it was jarring, but the thought persisted. So did fans' chatter, and Beamer wondered if their arguments might not have some merit. "If it was easy to know when to retire, more people would get it right, whether it's Michael Jordan or someone else," Virginia Tech athletic director Whit Babcock says. "Just looking at it, I can't think of any examples that did it better than coach Beamer."

*****

Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images

Throughout his career, Beamer has prided himself on one thing: the fact that he values relationships above football. "This is not just a chess game to him," Virginia Tech junior fullback Sam Rogers says. "These are people. He cares about people. I want to play for a coach that cares about his family more than the game. He makes people want to play for him."

Rogers can pinpoint the moment he knew he would do anything to play for Beamer. It was January 2012, and his brother, Ben, had been caught with a friend in a house fire near Richmond. Ben was fine, out of the hospital in a few days, but his friend was in critical condition for a time. Beamer heard the news, and as a former burn victim himself, it struck him. So he picked up the phone and dialed the hospital, wishing each of the young men well. Rogers, then a high school junior who wasn't even on the Hokies' radar, knew that was what he wanted in a football coach. Not two years later, he walked on at Virginia Tech and was awarded a scholarship within weeks. He has never once discussed that phone call with his coach. "He would never mention it," Rogers says, "because he doesn't think much of it. That's how he is."

Ekanem, who ended up at Virginia Tech because his other top choices yanked their offers after his tore his ACL as a senior at Centreville (Va.) High, can list stories of his coach's good works: paying for strangers' dinners, spending time with the terminally ill. But, he admits, he learned this all from the book, Let Me Be Frank: My Life at Virginia Tech, which came out in September 2013. Beamer himself would never think to bring up such things. He'd be too busy asking about your day, about your parents, about what you had for lunch and if you love this unseasonably warm winter.

Beamer has always been that way, naturally comforting and even-keeled. He is a voice of reason. But when he met with his players on Nov. 2 to announce the news they suspected was coming, the coach was visibly distraught. The team knew Beamer's retirement was the subject of the meeting, thanks to a leaked report, but still it was unprepared. "It was hard to watch," Ekanem says of the announcement. "We were hurt for him. We could hear the pain in his voice."

After the meeting, players began to trickle into Beamer's office. The coach was still upset—but they were even more so. Many were crying. All Beamer could do was welcome them in, hug them, tell them he loved them. On his most trying day, he remained their rock.

*****

Michael Shroyer/Getty Images

Beamer is thinner now than he once was, his hair uniformly white. Wearing a pair of trendy, rectangular black glasses and a half-zip pullover, he appears more kindly grandfather than football coach, which is exactly what he'll become on Sunday. The booming sideline presence seems to have shrunken, not into frailty, but into a man for whom age dictates certain limitations. Beamer, though, will have none of that.

Last December, the coach had throat surgery that caused him to miss Virginia Tech's bowl practices and game. He watched his team defeat Cincinnati 33–17 in the Military Bowl from a box at Navy's stadium, and afterward, he and Ballein made their way to the locker room. Beamer could barely speak, but his close friend asked if he had any words to share. The coach pulled out a sheet of paper and began to write. "From the box, the way you players played and the way you coaches coached made me so proud of this organization," Ballein read to the team once Beamer had finished. "You played with passion. You played with power."

Ballein can recite this message word for word, not from memory, but from the paper itself, which he saved inside his binder of material from the game. He will keep it forever, he says, along with the sheets upon sheets of Beamerisms he has collected over the years. But that day, it was less the coach's words that mattered than it was his moves. Once Ballein was finished reading, he looked up at the players. "Coach Beamer can't talk. But he can still dance," he told them. "And he broke out into this dance, and it was so incredible. It was so neat. It was so him. He wasn't about to talk, but he still broke into that dance."

Dancing after wins has long been Beamer's signature, a manifestation of his wicked sense of humor and uncanny ability to connect with his players despite the ever-widening age gap between them. This season, though, the dances were infrequent. He shimmied a bit on Sept. 19, when his team beat Purdue 51–24, but as the season wound down and players begged for the moves, he was hesitant. After starting the year 3–5, the Hokies had to win three of their last four games to keep Beamer's storied 22-year bowl streak alive, and with the tumult that accompanied the coach's announcement, it was hard not to wonder how they could. The locker room became serious.

After beating Georgia Tech 23–21 on Nov. 12, players begged for a dance. "I'm saving it," Beamer told them. "I'm saving it for a good one." The next week, the team lost to a surging North Carolina squad, but only by three points, which meant its final game, against rival Virginia—against whom Beamer boasts 12-game winning streak—would be a win-or-go-home affair. The Hokies were victorious, 23–20, and afterward the coach stood on a stool in the locker room. He gave his speech, handed out game balls. And then he gave his players that look, they call it, and he turned his cap sideways on his head, and he began to twist. He had saved it for a good one.

******

Michael Shroyer/Getty Images

Over the weeks since the Hokies learned their bowl destination, Beamer has tried to maintain the status quo in Blacksburg, even as the coaching staff that will succeed him sets up shop in suites in the stadium and almost invisibly begins its tenure. He has proceeded with his routines that have been the same for decades, and when he talks to his players about the game, he tells them to play it for the seniors, not for him. It's laughable, really, but patently Beamer. Sure, coach. We'll play for the seniors. And then his players turn around and laugh. They're playing for one man and one man only, even if he wouldn't hear of it.

Beamer doesn't have any concrete plans for the post-Dec. 26 world. There are no vacations scheduled, though he told his wife he wants to travel. The only thing on his agenda, he says, is to clean out his office. Then there will be golf to play, grandchildren to visit, a career as a speaker to explore, and maybe a foray into television. Beamer has always been a man itching to return to work from summer vacation, but Shane thinks his dad will adapt to retirement if he can stay busy enough. Well, he says, he hopes. We'll see.

A few years ago, the Beamers made renovations to their Blacksburg home, adding a theater room, pool tables, a sauna, an indoor golf simulator and a koi pond. (The koi gave birth last month. It was an event.) These updates were largely for recruiting purposes, so the coach could better host and entertain teenage football prospects when they came to town. Now, though, recruiting responsibilities are over, and the luxury will be all Beamer's. A few weeks ago he told his wife that they might have to make another addition. They would need a new room, he said, to house all of the memorabilia that has come his way since Nov. 2.

It started flooding in that week: a signed football from Clemson coach Dabo Swinney, another from the Washington Redskins, banners signed by thousands of people, each with a personal message. Letters accompanied the gifts, and as Beamer read them, he would often wander down the hall to his son's office. He would wave the note at Shane in astonishment, so amazed was he that another person had thought to write. After 22 bowl games and seven conference titles, the man is still wide-eyed. He is acutely aware of what he built in Blacksburg, but he seems less able to place himself in the pantheon of college football. He is just Frankie Beamer from Fancy Gap, who happened to be good at coaching young men, who got a little lucky and worked his tail off, who ended up here, surrounded by friends, staring down his legacy. One afternoon in December, he turned to Ballein. Gesturing at the wall of gifts, Beamer looked puzzled. What he said next would leave his friend shrieking with laughter.

"I didn't even know this many people knew me."